#der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Your argument is invalid

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deutschribing Germany

Literature

Middle Ages (5th-15th centuries)

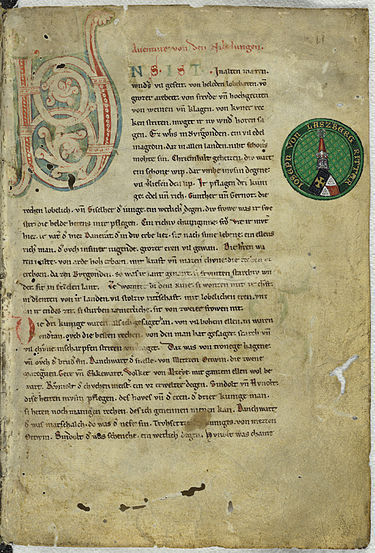

Medieval German literature can be divided into two periods: Old High German literature (8th-11th centuries) and Middle High German literature (12th-14th centuries). The only surviving works from the first period are the Hildebrandslied (Lay of Hildebrand), which is the earliest poetic text in German and tells of the tragic encounter in battle between a father and a son, and Muspilli, which deals with the fate of the soul after death and at the Last Judgment.

Middle High German literature saw a 60-year golden age known as mittelhochdeutsche Blütezeit, in which lyric poetry in the form of Minnesang—the German version of courtly love—blossomed thanks to poets such as Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach. Another important genre during this time was epic poetry, of which the most famous example is the Nibelungenlied (The Song of the Nibelungs), which narrates the story of prince Siegfried and princess Kriemhild, among other characters.

Renaissance (15th-16th centuries)

Early New High German literature includes works such as Der Ring (The Ring) by Heinrich Wittenwiler, a 9,699-line satirical poem where each line is marked with red or green ink depending on the seriousness of the material, and Das Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools) by Sebastian Brant, a satirical allegory that contains the ship of fools trope.

Other important authors are satirist and poet Thomas Murner, humanist Sebastian Franck, and poets Johannes von Tepl and Oswald von Wolkenstein.

Baroque (16th-17th centuries)

The Baroque period is characterized by works that reflected the experiences of the Thirty Years’ War and tragedies (Trauerspiele) on Classical themes, the latter were written by authors such as Andreas Gryphius and Daniel Caspar von Lohenstein. The most famous work is Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus (Simplicius Simplicissimus) by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, a picaresque novel that narrates the adventures of the naïve Simplicissimus.

Enlightenment (17th-18th centuries)

The most important writers of the Enlightenment are Christian Felix Weiße, Christoph Martin Wieland, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and Johann Gottfried Herder.

The Age of Reason saw the emergence of two literary movements: Empfindsamkeit (sentimental style) and Sturm und Drang (storm and stress). The first one intended to express true and natural feelings and featured sudden mood changes. The latter movement was characterized by individual subjectivity and extremes of emotion in response to the rationalism imposed by the Enlightenment.

Weimar Classicism (18th-19th centuries)

The main drivers behind Weimar Classicism, which synthesized ideas from Classicism, the Enlightenment, and Romanticism, were Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

During this period, Schiller published Die Bürgschaft (The Pledge), a ballad based on the legend of Damon and Pythias found in the Latin Fabulae, and Don Karlos (Don Carlos), a historical tragedy about Carlos, Prince of Asturias, while Goethe wrote Egmont, a play heavily influenced by Shakespearean tragedy, and Faust, a tragic play in which the main character sells his soul to the devil that is considered the greatest work of German literature.

Romanticism (18th-19th centuries)

Important Romantic writers include E. T. A. Hoffmann, author of Der Sandmann (The Sandman), a short story based on the mythical character of said name that puts people to sleep by sprinkling sand on their eyes; Heinrich von Kleist, who wrote Das Kätchen von Heilbronn (The Little Catherine of Heilbronn), a drama set in Swabia in the Middle Ages; Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, author of Das Marmorbild (The Marble Statue), a novella about a man who struggles to choose between piety and a world of art, and Novalis, author of Hymnen an die Nacht (Hymns to the Night), a collection of six poems.

Folk tales collected by the Brothers Grimm became very popular during the Romantic period, as they represented a pure form of national literature and culture.

Biedermeier and Young Germany (19th century)

The Biedermeier period contrasts with the Romantic era and is best exemplified by poets Adelbert von Chamisso, Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, and Wilhelm Müller.

Young Germany was a youth movement whose main proponents were Karl Gutzkow, Ludolf Wienbarg, and Theodor Mundt.

Realism and Naturalism (19th century)

The most representatives realist authors are Gustav Freytag, Theodor Fontane, and Theodor Storm, while Gerhart Hauptmann was the most important naturalist writer.

Weimar literature (20th century)

During the Weimar Republic, writers such as Erich Maria Remarque, Heinrich Mann, and Thomas Mann presented a bleak look at the world and the failure of politics and society.

Expressionism (20th century)

As a modernist movement, Expressionism presented the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it for emotional effect. Famous authors include novelists Alfred Döblin and Franz Kafka, playwrights Ernst Toller and Georg Kaiser, and poets August Stramm and Else Lasker-Schüler.

Neue Sachlichkeit (20th century)

Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) arose as a reaction against expressionism and was characterized by its political perspective on reality and portrayal of dystopias in an emotionless reporting style, showing cynicism about humanity. Authors associated with this movement include Erich Kästner, Hans Fallada, and Irmgard Keun.

Nazi Germany (1933-1945)

During the Nazi regime, some authors went into exile, while others submitted to censorship. The former, who either were of Jewish ancestry or opposed the regime for political reasons, include writers Alice Rühle-Gerstel and Anna Seghers, playwright Bertolt Brecht, and poet and novelist Hermann Hesse/Emil Sinclair.

Those who stayed and engaged in inner emigration include writer Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen, poet and essayist Gottfried Benn, writer Hans Blüher, and poet and novelist Ricarda Huch.

Post-war literature (20th century)

The most famous authors in West Germany were Edgar Hilsenrath, Günter Grass, Heinrich Böll, and Group 47, a group of participants in writers’ meetings invited by Hans Werner Richter.

East German writers include Christa Wolf, Heiner Müller, Reiner Kunze, and Sarah Kirsch.

Contemporary literature (21st century)

Fantasy and science fiction authors include Andreas Eschbach, Frank Schätzing, and Wolfgang Hohlbein. Some of the most important poets are Aldona Gustas, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, and Jürgen Becker. Thriller is best represented by Ingrid Noll. Fiction novelists include Herta Müller, Siegfried Lenz, and Wilhelm Genazino.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Adventurous Simplicissimus (Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus)

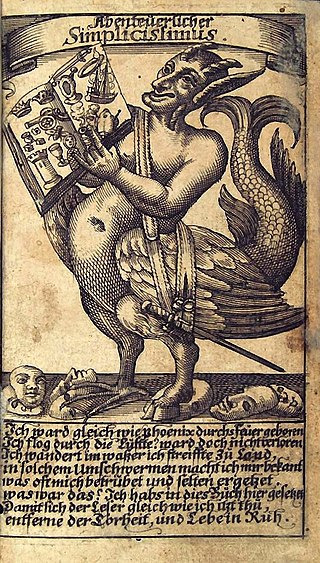

Frontispiece of the novel „The Adventurous Simplicissimus“, 1669

"I was born of fire like Phoenix. I flew through the air, and I wasn't lost. I wandered in the water, I roamed on land, in such wanderings I made known to myself what often saddened me and seldom delighted me; what was that? I have written it in this book here that the reader, like me, remove himself from folly and live in peace.”

-Hans Jakob Christoffel of Grimmelshausen (1621-1676)

The Adventurous Simplicissimus (Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus) is a story set against the backdrop of the 30 Years‘ War (1618-1648) in Germany - and is considered the world’s first adventure novel and most important baroque prose work in German. The novel tells the adventurous life of the main character and his simple, sometimes naive and innocent view at the world. In the end he becomes a hermit and writes down his life in retrospect.

Life itself is an exciting adventure and sometimes not without a certain irony - because things often turn out differently than you imagined. Experiences shape us, determine our actions and our view at this world:

#Traveling

#Quotes

#Music

#Movies

#Books

#Simplicius Simplicissimus (personal view on different topics)

„Grimmelshausen Hotel“ in Gelnhausen (we live nearby☺️) - the house where Hans Jakob Christoffel of Grimmelshausen was born.

For a collection of my best photos - visit my side blog „play-of-colors“. For a collection of some quotes which reflect my mindset - visit my side blog „mental-food“.👋🏻

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Der Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus .. Gottfried von Strassburg .. August Schleicher .. about Verb qaddara

Simplicius verzettelt seinen Saurbrunnen an einem unrechten Ort Das 18. Kapitel ★★ Simplicius verzettelt seinen Saurbrunnen an einem unrechten Ort .. (an einem un*-rechten Ort) draw attention to (neglect and overlooking) pointing to (lack of Te’dabbur) • (Te’dabbur) is the complete opposite of (neglect and overlooking) ~ (se foutre de qqch – not give a damn – ne pas accorder d’importance à…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Another lovely antique book finding...just across the street! It's not everyday you stumble into something like this, especially when it's for free! Here we have a 1880 printing of the 17th century work, "Simplicius Simplicissimus" (Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus) by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen. It's considered to be the first adventure novel in the German language and Germany's first literary masterpiece.

The Pining Poet ©: "We are Dark Academia."

Go to www.thepiningpoet.com to find out how you can contribute to the first-ever Dark Academia digest! Submit your original content entries for Dark Academian writing/poetry/prose/style/fashion via our website. See you there...

#kamillealexandra #author #poet #prose #thepiningpoet #writing #poetry #poems #freeverse #writers #WritingCommunity #darkacademia #ejournal #darkacademiaaesthetic

#literaryquotes #literature #literaryjournal #poetrycommunity #quotes #novels #classicliterature #booklovers #antiqueshop #antique #antiquebook #antiquebooks #adventurestories #grimmelhausen #deutschland #germany

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The modern German novel begins with The Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus (Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch, 1668) by Hans Grimmelshausen (1622?–76). One of the greatest novels of the 17th century, this 5-part, 400-page book is a boisterous Oktoberfest of genres bumping bellies: bildungsroman, picaresque, allegory, (anti)war novel, hagiography, fantastic voyage, romance, ghost story, sermon, and utopian novel. Referring to the frontispiece depicting a leering satyr/phoenix/bird/fish creature pointing at a book, one German critic admitted “the history of literary forms stands helpless before such a Tragelaph.”64 Initially, it resembles a picaresque novel, especially Alemán’s Guzman of Alfarache, which had been adapted into German by Aegidius Albertinus in 1615. Beginning about halfway through the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), the narrator explains how he was raised nameless and uneducated among peasants until the marauding Imperial army looted his village when he was 12 or 13; he escapes into the nearby forest and is taken under the wing of a religious hermit who names him Simplicius because of his ignorance—he’s never seen a horse, and assumes soldiers riding them are a centaurlike hybrid of man and wolf—and brainwashes him with Christianity before allowing him to read more books borrowed from the local pastor. After the hermit dies, Simplicius returns to the world at war and yo-yos from one camp to another; treated like a fool, he becomes a professional jester until he can work his way up the ranks. He becomes a marauding prankster known as the Hunter of Soest, and on one occasion discovers an abandoned treasure in a haunted house, which seems to ensure his fortune. Knowing he’s betraying his Christian upbringing but powerless to resist, Simplicius then accompanies a young nobleman to Paris, where he becomes an actor and a gigolo, the beginning of a downward moral spiral that takes him back penniless to Germany, where he scrapes by as a traveling quack until he’s forced back into the army. Determined to settle down, he marries a country lass (who turns into a drunk), reunites with his “father” (who tells Simplicius he is actually the son of the hermit who raised him, a Scottish nobleman who abandoned the world in disgust), travels some more (Russia and Asia) before returning home disillusioned with everything, and becomes a hermit—choosing the life that had been forced upon him as a frightened boy. So it seems the entire novel has been a sermon against unchristian behavior, and a religious call for renunciation of the sinful world.

But Grimmelshausen complicates this picaresque pilgrim’s progress in many intriguing ways. On the one hand, the novel is graphically realistic, much more so than spiritually oriented works are. The attack on young Simplicius’s village is described in sickening detail: the soldiers ransack and torch everything, torture the peasants, and rape the women. Later, peasants capture a soldier, cut off his nose, and force him to lick their assholes before they bury him alive in a barrel; when other soldiers capture the cleansed peasants, “They bound their hands and feet together round a fallen tree in such a way that their backsides (if you will forgive me again) were sticking up nicely in the air. Then they pulled down their trousers, took several yards of fuse, tied knots in it and ran it up and down in their arses to such effect that the blood came pouring out. The peasants screamed pitifully, but the soldiers were enjoying it and did not stop their sawing until they were through the skin and flesh and down to the bone.”65 Young Grimmelshausen was an eyewitness to such atrocities—the first third of the novel is somewhat autobiographical; his handling of a child’s POV is superb—and his willingness to report what he saw so unflinchingly makes Simplicissimus a primary source for historians of the Thirty Years’ War. (You’ll recall the Spanish Estebanillo González is also set during that conflict and captures some of the chaos of war, but Grimmelshausen focuses on the civilian population.)

Such language also makes the novel a primary document in the rise of realism in fiction; not since Thomas Nashe had any novelist dared to describe the aftermath of battle in such gruesome terms as he uses: “there were heads that had lost the bodies they belonged to and bodies lacking heads; some had their entrails hanging out in sickening fashion, others their skull smashed and the brain spattered over the ground; . . . there were shot-off arms with the fingers still moving, as if they wanted to get back into the fighting, . . .” (2.27). The dialogue is equally realistic: “Pox on you, brother, are you still alive?” one soldier greets another. “By the holy fuckrament, the Devil looks after his own!” (1.26). As a licensed fool, Simplicius doesn’t mince words when asked to describe a fashionable visitor: “This lady has hair as yellow as baby shit and the parting is as white and as straight as if she had been hit on the scalp with a curry-comb. And her hair is in such neat rolls it looks like hollow pipes, or as if she had a pound of candles or a dozen sausages hanging down each side. And oh, look at her lovely smooth forehead, is it not more beautifully curved than a fat buttock and whiter than a dead man’s skull which has been hanging out in the wind and rain for years?” (2.9). Simplicius often embarrasses himself by farting noisily; people vomit, shit, swear, scratch at lice and fleas. There’s sex and some nudity: sailing on the Danube for Vienna, Simplicius “had eyes for nothing but the women who answered the calls from the boats with literal rather than verbal bare-arsed cheek” (5.3).66 The point is religious writers don’t write like this—nowhere in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress does a farmboy tell a dairymaid “that she could kiss his arse and go fuck her mammy in the bargain” (3.23)—which calls into question the ostensibly religious orientation of the novel. Something else is afoot.

Though highly realistic, more so than most pre-20th-century novels, Simplicissimus is, on the other hand, highly unrealistic and brazenly supernatural. Grimmelshausen’s novel often reads like a Grimms’ fairy tale, for Simplicius lives in a demon-haunted world where people still cast spells, foretell the future, and consort with devils. When he leaves the forest for the town, some citizens “thought I was a spectre, a ghost or some such phenomenon” (1.19)—phenomena as real to them as the butcher or the baker. In book 2, Simplicius is foraging at night and sneaks into a farmhouse, where he spies a few people who “had a sulphurous blue lamp on the bench by the light of which they were greasing sticks, brooms, pitchforks, stools and benches. Then, one after the other, they flew out of the window on them.” Puzzled, he sits on one of the benches and instantly shoots out the window and lands about 150 miles northeast to witness a witches’ dance, described with Boschean extravagance. Invited to join the dance, “I cried out loud to God, at which the whole crew vanished” (2.17). Simplicius insists this actually happened, and wasn’t a dream; citing similar stories from reputable scholars, including the story of Faust, he dares the reader to disbelieve him: “if you don’t believe it, you will have to think up some other way in which I went in such short time from Hersfeld or Fulda (I still don’t know where I was, wandering round in the forest) to the vicinity of Magdeburg” (2.18). There he is taken into a regiment that includes a prevost-sergeant who “was a true sorcerer and black magician who knew a spell for finding out thieves and another to make not only himself as bullet-proof as steel, but others too.” To find a thief, “the sorcerer muttered a few words and puppies started to jump out of people’s pockets, sleeves, boots, flies and any other openings in their dress, one, two, three or more at a time” (2.22). A little later, Simplicius invents a pocket-sized instrument that enables him to hear things taking place miles away, and again taunts the reader: “However, I am not surprised if people do not believe what I have just written” (3.1). The treasure he discovers is guarded by a “ghost or wraith” (3.12), which is not a product of his imagination, nor is the demon who speaks to him from inside a man undergoing exorcism (5.2). Near the end is the greatest test of the reader’s incredulity: tossing some stones into the “enchanted” Mummelsee, “a supposedly bottomless lake” (5.10)—a real lake in the Black Forest, but now known to be only 55 feet deep—some sylphs come to the surface, give him a magic jewel that enables him to breathe underwater, then take him to the center of the earth for a 16-page tour of their subterranean world and discuss their place in the Christian scheme of things.67

All this takes place on the “factual” plane of the novel, and doesn’t include numerous instances where people are mistaken for devils, or Simplicius’s allegorical dream of the military establishment as a tree (which allows Grimmelshausen to criticize further the suffering inflicting upon civilians) “with Mars, the God of War, on the top, and covering the whole of Europe with its branches” (1.18). One chapter is entitled “How Simplicius Was Dragged Down into Hell by Four Devils and Treated to Spanish Wine” (2.5), followed by “How Simplicius Went to Heaven and Was Turned into a Calf” (2.6), but these are merely pranks soldiers play on the naïve lad. Later he meets a madman who calls himself Jupiter, whom Simplicius plays along with by referring himself to Ganymede or Mercury, and layered on top of other references to classical mythology and German folklore is an elaborate set of references to Chaldean astrology. It’s tempting to call this magic realism were it not closer to the aesthetics of the medieval morality play, where figures representing devils or the sun shared the same stage as mortals. Christianity is part and parcel of this magical/medieval world: throughout the novel, saints and angels are evoked in the same breath as figures from myth and folklore, supernatural events are defended with citations of similar events in the Bible, and Christian theology is indistinguishable from the world of myth and magic. If you believe in the miracles in the Bible, the novel implies, then you’re no different from those who believe witches ride broomsticks and sorcerers cause puppies to magically crawl out of your pocket. As in Don Quixote, there is a clash between old-world and new-world weltanschauungs, and by the end of the novel, Christianity has been so thoroughly contaminated by its association with outdated mythology that Simplicius’s quixotic decision to renounce the world at age 33 and become a Christian hermit can only be regarded as the act of a simpleton. The novel encourages figurative detachment from the world, not literal.

Grimmelshausen certainly didn’t drop out to play the holy fool: he managed estates, ran several inns, was the mayor of a small town, had 10 kids, and wrote more than 20 books. He converted from Protestantism to Catholicism when younger (to help his careers, it’s been suggested), but he knew the only real magic is the act of artistic creation. There’s a lovely passage near the end of book 1 in which an officer’s secretary praises writing as a way to make a living; Simplicius thinks he’s talking about magic (and is reminded of “Fortunatus’s inexhaustible purse”), but Grimmelshausen is also praising the novelist’s art of creating something from nothing:

I once criticised him for his dirty inkwell but he replied that it was the best thing in his whole room for he could draw up out of it anything he wanted: fine gold ducats, fine clothes, in short all his possessions had been fished out of his inkwell one by one. I refused to believe that such magnificent things could be obtained from such a paltry container. He replied that it was the spiritus paperi, as he called the ink, that did it, and that an inkwell was called a well because you could draw up all sorts of things out of it. (1.27)

Out of Grimmelshausen’s dirty inkwell came this devilishly clever satire on 17th-century society, a world “so full of foolishness that no one takes any notice or laughs at it anymore,” as Simplicius notes (3.17), encouraging him to “castigate all follies and censure all vanities” (2.10). Simplicissimus begins like a picaresque bildungsroman but opens up into a Menippean satire, a blitzkrieg against pretension, hypocrisy, superstition, and especially the alleged nobility of war. There’s no bullshit here about dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, a con kings and politicians have been using to recruit cannon-fodder ever since Horace penned that piece of propaganda. The Thirty Years’ War was essentially a family squabble between the Hapsburgs and the Bourbons for territorial control over Europe (with some Protestant vs. Catholic window-dressing), about as noble as a mob turf war, and though Grimmelshausen sarcastically notes war is good for business (5.5), he rubs his reader’s face in its barbaric nature with a force that wouldn’t be felt again until the antiwar novels of the 20th century. As Simplicius fools his way through war-torn, phantasmagoric Germany, I was remind of Slothrop in Gravity’s Rainbow; Grimmelshausen even indulges in some Pynchonesque personification: on one of his foraging expeditions, Simplicius sees “a sight for sore eyes or, rather, empty bellies: hanging up in the chimney were hams, sausages and sides of bacon. They seemed to be smiling at me, so I gave them a come-hither look, wishing they would come and join my comrades in the woods, but in vain; the hard-hearted things ignored me and stayed hanging there” (2.31). Simplicissimus belongs to the same insubordinate platoon as The Good Soldier Švejk, The Tin Drum, and Catch-22.

Though Grimmelshausen drew upon personal experiences for the early parts of the novel, he drew mostly upon his extensive reading. Scholars have shown that more than 150 books went into the making of this erudite novel, ranging from classical authors and the medieval Parzival to the 6-page passage from Antonio de Guevara’s 16th-century theological tract that concludes book 5. A German translation of Charles Sorel’s iconoclastic antinovel Francion (see pp. 182–86 below) was a major inspiration, but Grimmelshausen also drew upon Italian novellas and German jestbooks (like Till Eulenspiegel), encyclopedias and almanacs, and manuals on witchcraft like Johann Wier’s De Præstigiis dæmonium (2.8). A battle scene that sounds like an eyewitness report actually comes from a German translation of Sidney’s Arcadia (which should give military historians pause). On one occasion, Simplicius visits a pastor and finds him “reading my Chaste Joseph” (3.19)—a biblical novel Grimmelshausen published in 1666, though it’s only 1639 at this point! That’s so obviously an anachronism that it has to be deliberate, another taunting call for the suspension of disbelief like Simplicius’s magical bench ride and his sylph-escorted journey to the center of the earth. It’s all one to “the old inkslinger” (2.4).

Cervantes waited 10 years to publish a sequel to Don Quixote, but Grimmelshausen jumped on the unexpected success of Simplicissimus. When the 5-book novel was reprinted in 1669, he added a 6th book simply entitled Continuation (Continuatio), though scholars are divided on whether this forms an organic whole with the previous part, or is the first of several sequels Grimmelshausen published over the next few years.

Like most hastily written sequels, the Continuation isn’t very good. Picking up where book 5 left off, Simplicius’s solitary life as a hermit seems to be driving him crazy, for first he recounts a long, allegorical dream that starts in hell with Lucifer gnashing his teeth at the declaration of peace that ended the Thirty Years’ War, which morphs into a didactic tale of a rich young Englishman who ruins himself through conspicuous consumption. Our hairy hermit then encounters a statue that comes to life, and—after Simplicius decides to hit the road as a pilgrim—he gets into an argument with some toilet paper, who delivers a long economic history of its many metamorphoses from seed to paper (a remarkable set-piece that again brings Pynchon to mind). Mistaken for the Wandering Jew, spooked by ghosts, Simplicius has further bizarre adventures as he travels to Egypt, then is shipwrecked on a deserted island off the coast of Australia, where he leads a Robinson Crusoe-type existence—this section was based on the popular English novelette by Henry Neville, The Isle of Pines (1668)—and there he writes the entire Simplicissimus novel on palm leaves. Refusing rescue by a Dutch sea captain, Simplicius intends to live out the rest of his pious life on his island hideaway, “an example of change and a mirror of the inconstancy of human life.”68 Although the book offers further displays of the author’s outlandish erudition, it’s too didactic, too medieval.

Grimmelshausen returns to form in The Life of Courage (Die Landstörtzerin Courasche, 1670).69 Near the end of Simplicissimus, our protagonist had boasted of seducing and dumping a beatiful lady, a “man-trap” whose “easy virtue soon disgusted him” (5.6); nine months later, she leaves a baby on his doorstep, who Simplicius reluctantly makes his son and heir. Audaciously blurring the distinction between fiction and reality, Grimmelshausen states in a headnote that this unnamed woman read Simplicissimus and was so insulted at her portrayal therein that she decided to avenge herself by telling the story of her life, revealing that the woman he took for an aristocrat was actually a promiscuous adventuress infected with syphilis—which raises an intriguing possibility: Did Simplicius contract the disease from her? Untreated, it can cause insanity, which would explain the underwater sylphic adventure later in book 5 and the talking toilet paper. Indeed, the entire bizarre Continuation can be read as a neurosyphilitic hallucination. If nothing else, it stinks up the odor of sanctity with which Simplicissimus ends.

Just as the Continuation anticipates Robinson Crusoe, this short novel anticipates Defoe’s Moll Flanders, but with no apology at the end for the life she’s led. (Grimmelshausen, however, tacks on a homiletic warning against following her example.) Inspired by a German translation of Lopez de Úbeda’s Justina, Grimmelshausen backtracks to the very beginning of the Thirty Years’ War. Born in Bohemia, 13-year-old Libuschka disguises herself as a boy to avoid rape from invading soldiers and joins the army: “I made a great effort to get rid of all my woman’s habits and acquire man’s. I took great pains to learn to swear like a trooper and drink like a fish . . . so that no one should suspect there was something I had not been endowed with at birth” (2). When it’s revealed during a fight she lacks that certain something, she defiantly calls her vulva Courage, which becomes her girl-power nom de guerre in her fight against male prejudice as well as opposing armies.70 Over the next dozen years, she is repeatedly married to soldiers, repeatedly raped by other other soldiers, then becomes a prostitute, then a black marketeer, doing whatever it takes to survive the war, and marrying whoever promises shelter from the storm. (Through no fault of her own, her husbands usually perish before their first anniversary.) She’s smart, as courageous as her name implies, and fiercely independent; she doesn’t really descend into criminal behavior until later in life, when she joins a band of Gypsies. And that child she left on Simplicius’s doorstep? Not hers, but her slutty maid’s. Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned, and Courage takes self-incriminating delight in telling Simplex (as she calls him) how wrong he was about everything.

Like Simplicissimus, Courage is graphically realistic but includes a few magical elements. The Spanish Justina tried to dodge sexual encounters, but Courage welcomes them: she’s a novelty in novels of this period, a sexually active woman who doesn’t feel guilty about scratching her itch (as puts it). While we have to remember that a man is writing this, Grimmelshausen was a worldly one and knew that women have sexual desires too, which you wouldn’t guess from most novels published before the 20th century. Like Simplicius, Courage occasionally reads courtly romance novels, but only to pick up “pretty turns of phrase from” for the purposes of seduction (5; cf. Simplicissimus 3.18: “these books taught me how to lure the female sex”). Rebelling against the polite romance tradition, Grimmelshausen opposes his hard-core realism to their unrealistic fantasies; like his model Charles Sorel, he was out to destroy the mainstream novel, and Courage is an earthy and bracing alternative to most 17th-century fiction.

One of Courage’s longer-term relationships was with a lackey/paramour she nicknamed Tearaway, from the time she told him, “Tear yourself away from that cart and go and fetch the dappled grey from the grazing” (16). After she dumped him for drunkenness and domestic violence, this rascal became one of Simplicius’s gang during his Hunter of Soest period. He tells his story in Tearaway (Der seltzame Springinsfeld, 1670), which begins when the young scribe Courage had hired to write down her memoir runs into Simplicius, lately returned from Australia, and his old servant Tearaway at an inn.71 The scribe tells them what Courage dictated to him—Simplicius interrupts to admit he was also banging Courage’s maid, so that baby is his son after all—and also of her life with the Gypsies. (Grimmelshausen may be the first to write about them in fiction.) We learn that Simplicius, as pious as ever, is annoyed that readers are treating his Simplicissimus merely as a jestbook like Till Eulenspiegel instead of the Christian allegory he intended. Incongruously, he is now making a living as a traveling salesman peddling an elixir that improves wine, using a magic book as part of his spiel—another occasion Grimmelshausen uses, like the dirty inkwell, for a tribute to the power of imaginative writing—and after nine chapters of metafictional scene-setting, Tearaway tells how he spent the war. Like much of Simplicissimus, Tearaway is a grim, grunt’s-eye view of war, where greed for booty trumps patriotic duty, and which brings out the worst in everyone. Tearaway admits “Soldiers are there to persecute the peasants and any that leave them in peace aren’t doing their job properly,” but also notes “some peasants were worse than the good soldiers themselves. They not only murder soldiers, innocent and guilty, whenever they managed to get hold of them, when they had the chance, they stole from their neighbours, even from their own friends and relations” (13). This section is sketchy, obviously worked up not from firsthand experience but from the same war chronicle Grimmelshausen used for Courage, Eberhard von Wassenberg’s Erneuerter Teutscher Florus (1647). After the war is over, Tearaway marries a widow and becomes a crooked innkeeper, abandons both, then marries a hurdy-gurdy player and scrapes out a living accompanying her on the fiddle as wandering musicians. This colorful, realistic account of tramping morphs into a fairy tale in which his wife discovers a magical bird’s nest that confers invisibility on its owner; Tearaway’s too cowardly to use it for gain—she isn’t, and winds up being burned as a witch as a result—and the tatterdemalion is still playing for pfennigs when he runs in to his old master. Simplicius tries to recall him to Christian principles, which Tearaway initially dismisses as “a load of monkish tripe” (27), though he repents just before he dies.

“The Miraculous Bird’s Nest” (Das wunderbarliche Vogelnest, 1672 [part 1] and 1675 [part 2]) is the title of the last two sections of what Grimmelshausen eventually called the Simplician Cycle. In part 1, a do-gooder named Michael uses the cloaking device to obstruct various misdeeds while searching for an honorable way to make money; in part 2, an unnamed merchant, less scrupulous than Michael (and more like Tearaway’s wife), takes advantage of invisibility to commit various acts of greed, lust, and sorcery. The miraculous bird’s nest functions as a “lens through which the bearer perceives reality” (Negus, 124), another analog for one of fiction’s purposes. Simplicius’s son appears in one episode in part 1, but otherwise the 2-part novel is only thematically related to the preceding novels, emphasizing once again the inconstancy of fortune, the prevalence of evil, and the consequent necessity of adhering to Christian principles. Books 1 through 8 of the Simplician Cycle depicted a world at war, but in these final two books Grimmelshausen argues that the world at peace is just as dangerous. They sound mildly entertaining, but as they’ve not been translated, I can only direct the interested reader elsewhere for more on the conclusion to Grimmelshausen’s 10-part, 800-page meganovel.72

Unlike part 2 of Don Quixote, the second half of the Simplician Cycle isn’t as impressive as the first half (i.e., Simplicissimus), but that doesn’t prevent Grimmelshausen from occupying the same lofty position in early German literature, and his influence on later German writers is profound. He impressed Ludwig Tieck and other German Romantics, the Grimm brothers and Goethe, and his work played a patriotic part in the unification of Germany in the 19th century. Most major German novelists of the 20th century have paid tribute to him: Thomas Mann borrowed from his work for his Felix Krull and Doctor Faust, and in his introduction to a Swedish translation of Simplicissimus, he wrote: “It is the rarest kind of monument to life and literature, for it has survived almost three centuries and will survive many more. It is a story of the most basic kind of grandeur—gaudy, wild, raw, amusing, rollicking and ragged, boiling with life, on intimate terms with death and the devil—but in the end, contrite and fully tired of a world wasting itself in blood, pillage and lust, but immortal in the miserable splendor of its sins.”73 Hesse greatly admired Grimmelshausen, and from him Bertolt Brecht conceived the idea for his play Mother Courage and Her Children (1949). Grimmelshausen’s earthy, erudite, punning language was an inspirational starting point for Arno Schmidt’s even more outlandish diction. I implied earlier that the young Simplicius has something in common with Oskar Matzerath in Günter Grass’s Tin Drum (1959), and Grimmelshausen steals the show in Grass’s erudite critifiction The Meeting at Telgte (1979), an imaginary conference of several German authors in 1647, in which Grass affectionately roasts the old inkslinger:

In his green doublet and plumed hat he looked like something out of a storybook. . . . [After he] had offered his services in a long-winded speech well larded with tropes, Harsdörffer took Dach aside. True, he said, the fellow prates like an itinerant astrologer—he had introduced himself to the assemblage as Jupiter’s favorite, whom, as they could see, Venus had punished in France—but he had wit, and was better read than his clowning might lead one to suspect. . . . His lies, said Harsdörffer, are as inspired as any romances; his eloquence reduces the very Jesuits to silence; not just the church fathers, but all the gods and their planets are at his fingertips; he is familiar with the seamy side of life, and wherever he goes, in Cologne, in Recklinghausen, in Soest, he knows his way about. . . . Hofmannswaldau stood dumbfounded; hadn’t the fellow just quoted a passage from Opitz’s translation of the Arcadia? . . . His words seemed as trustworthy as the sheen of the double row of buttons on his green doublet. (6–7)

In this novel Grimmelshausen is still in his mid-twenties, but someday, the narrator predicts, “he would let every foul smell out of the bag; a chronicler, he would bring back the long war as a word-butchery, let loose gruesome laughter, and give the [German] language license to be what it is: crude and soft-spoken, whole and stricken, here Frenchified, there melancolicky, but always drawn from the casks of life. Yes, he would write! By Jupiter, Mercury, and Apollo, he would!” (112–13).

#steven moore#the novel: an alternative history 1600-1800#hans jakob christoffel von grimmelshausen#simplicissimus#tom nashe#miguel de cervantes#bertolt brecht#arno schmidt

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Obwohl das Gedicht in der Barockzeit die beliebteste literarische Ausdrucksform war, wurden natürlich auch erzählende Texte verfasst, etwa Romane, Schwank, Satire oder Sprüche. Bekanntestes Werk ist hier der Schelmenroman Der Abentheuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch von Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen aus dem Jahr 1668. Er gilt als der erste Abenteuerroman. Ansonsten gab es im Barock viel nicht-fiktionale oder Sachliteratur: Reisebeschreibungen, Predigten und journalistische wie wissenschaftliche Werke.

Bildquelle https://stock.adobe.com/de/images/book-frontispiece-simplicius-simplicissimus-der-abenteuerliche-simplicissimus-teutsch-picaresque-baroque-novel-written-in-1668-by-hans-jakob-christoffel-von-grimmelshausen/333521774?as_campaign=ftmigration2&as_channel=dpcft&as_campclass=brand&as_source=ft_web&as_camptype=acquisition&as_audience=users&as_content=closure_asset-detail-page

0 notes

Text

It has come to our attention that some millennials on Tumblr people don’t like 1st person narrative in fiction. We were quite baffled by the notion (”But... like... Song of Achilles is 1st person. And half of Bleak House. And Gone Girl!”). Immortality AU, of course, is 1st person, and so are the books on this list which we compiled off the top of our heads because they are immensely popular and/or personal faves:

British and Irish Classics:

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Villette by Charlotte Bronte

Tom Jones by Henry Fielding (the omniscient narrator narrates in the 1st person)

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

all (?) of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

half of Bleak House by Charles Dickens

Vendetta by Marie Corelli

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie

Murder at the Vicarage by Agatha Christie

as well as other Christie stories, including Poirot ones

loads of classic horror short stories

American Classics:

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

all or most of Edgar Allen Poe

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote

Other Classics:

Justine by the Marquis de Sade

Much of Pushkin’s work

La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas, fils

Modern English-language novels

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller

As Meat Loves Salt by Maria McCann

half of The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley

also: some of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s short stories, most notably the one with the Lesbian Reveal

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

half of House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

Mysterious Skin by Scott Heim

Exquisite Corpse by Poppy Z. Brite

The Hotel New Hampshire by John Irving

Fingersmith by Sarah Waters

Tipping the Velvet by Sarah Waters

Rivers of London by Ben Aaronovitch

High Fidelity by Nick Hornby

A Long Way Down by Nick Hornby

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon

American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie by Alan Bradley

Fight Club by Chuck Palahniuk

The Quiet American by Graham Greene

Modern non-English novels

The Tin Drum by Günter Grass

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

Foucault’s Pendulum by Umberto Eco

A Heart So White by Javier Marias

ALL epistolary, memoir and diary-style novels:

Dracula by Bram Stoker

Les Liaisons dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos

The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Fanny Hill by John Cleland

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir

Just Kids by Patti Smith

Carrie by Stephen King

I, Claudius by Robert Graves

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ by Sue Townsend

The Diary of Bridget Jones by Helen Fielding

We Need To Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver

Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar

World War Z by Max Brooks

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

half of Emily Climbs by Lucy Maud Montgomery

Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer

Children’s Books:

How to Survive Summer Camp by Jacqueline Wilson

The Best Christmas Pageant Ever by Barbara Robinson

There’s also books that pass by English speakers because they’ve never been translated or never caught on, but are popular in other countries:

Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (the first novel in the German language)

Six Bullerby Children by Astrid Lindgren

Brothers Lionheart by Astrid Lindgren

Felidae by Akif Pirinçci (cat detective mysteries)

Der Rumpf by Akif Pirinçci (thriller from the PoV of a disabled mastermind)

Confessions of Felix Krull by Thomas Mann

Olfi Obermeier und der Ödipus by Christine Nöstlinger (coming-of-age story of a boy who grows up in a household ruled by women)

Konopielka by Edward Redliński

The Devil's Elixirs by E.T.A. Hoffmann

Aischa by Federica de Cesco (coming-of-age story of a Muslim immigrant girl in Paris)

Lélia by George Sand

Chronicler of the Winds by Henning Mankell

The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by Jan Potocki

#1st person narration#is great#between them your Authoresses read 99% of these books#many of them are all-time faves#what's the rationale behind disliking 1st person?#has it ever been explained?#or is it just an edgy thing that kids-these-days do?

114 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch Teil 1 | Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen | Action & Adventure Fiction, War & Military Fiction | Audiobook full unabridged | German | 1/7 Content of the video and Sections beginning time (clickable) - Chapters of the audiobook: please see First comments under this video. Der Abentheuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch ist ein Schelmenroman von Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, erschienen 1668. Er wird gemeinhin als das wichtigste Werk seiner Art im 17. Jahrhundert betrachtet. Ferner gilt er als der erste deutschsprachige Abenteuerroman mit stark autobiographischen Zügen, da er die Lebenswege von Autor und Held im Dreißigjährigen Krieg (1618–1648) teilweise zusammenführt, ohne sie freilich zur Deckungsgleichheit zu bringen. (Summary nach Wikipedia) Prooflisteners: Al-Kadi, Buechermaus, Rolf Kaiser, Hokuspokus This is a Librivox recording. If you want to volunteer please visit https://librivox.org/ by Priceless Audiobooks

0 notes

Photo

Matthias Habich Und alle haben geschwiegen ist ein deutscher Fernsehfilm aus dem Jahr 2012, der anhand einer fiktiven Geschichte das Unrecht in der westdeutschen Heimerziehung thematisiert. Der Film basiert auf dem Buch Schläge im Namen des Herrn von Peter Wensierski von 2006. Die Fernsehpremiere erfolgte am 4. März 2013 im ZDF. ‚Und alle haben geschwiegen‘ gibt den Opfern zurück, was ihnen im Heim geraubt wurde: Ihre Würde“. Peter Wensierski (* 1954 in Heiligenhaus) ist ein deutscher Schriftsteller, Journalist und Dokumentarfilmer. Er arbeitet seit 1993 für das Nachrichtenmagazin Spiegel (Deutschland-Ressort). Bekannt wurde er auch durch seine Bücher (u. a. Schläge im Namen des Herrn), dazugehörige Dokumentationen im Fernsehen sowie als Preisträger des Bundesfilmpreises für Berliner Blau und eines „Europäischen Fernsehpreises“ 1993 für einen Film über Berlin-Marzahn. Besetzung Senta Berger: Luisa Keller Matthias Habich: Paul Alicia von Rittberg: junge Luisa Leonard Carow: junger Paul Antje Schmidt: Gertrud Keller Marie Anne Fliegel: Schwester Elisabeth Birge Schade: Schwester Ursula Jasmin Schwiers: Jana Michels Anke Sevenich: Schwester Clara Handlung 2008: Luisa ist aus den USA nach Deutschland zurückgekehrt, um nach jahrzehntelangem Verdrängen endlich über die Zeit in einem Kinderheim der evangelischen Kirche zu sprechen. Sie und Paul sind eingeladen worden, vor dem Runden Tisch im Bundestag darüber zu berichten, was sie dort erleiden mussten. Für beide ist es auch ein Wiedersehen nach langer Zeit, denn nach ihrer kurzen Liebe hatten sie den Kontakt zueinander verloren. 1964: Weil ihre alleinerziehende Mutter schwer erkrankt, kommt die sechzehnjährige Luisa ins Kinderheim. Dort werden alle Kinder und Jugendlichen nur als Nummern angesprochen, Luisa wird Nr. 84. Wie alle dort wird sie geschlagen, gedemütigt und drangsaliert. Der gleichaltrige Paul fällt ihr auf, als er am ersten Tag nach seiner Ankunft das Vaterunser vorbeten soll. Neben ihm steht der Pfarrer bereit, um jeden Fehler oder Versprecher mit Schlägen auf die Hände zu ahnden. Paul stottert. Alle Insassen müssen schwere Arbeit verrichten, die Mädchen in der Mangelstube oder beim Putzen, die Jungen in den Werkstätten. Ständig werden sie von den Schwestern überwacht und gemaßregelt. Als die Leiterin des Heims, Schwester Elisabeth, in die Mangelstube kommt, um Luisa zu begrüßen, traut sich das Mädchen, eine Frage zu stellen: wann sie wieder zur Schule gehen dürfe, ihre Lehrerin glaube, dass sie das Abitur schaffen könne. Die Antwort der Schwester zerstört all ihre Hoffnungen. Die Mädchen seien dazu bestimmt, einen Mann zu finden, ihn und die Kinder zu umsorgen und den Haushalt zu führen. Dazu brauche sie kein Abitur. Kurze Zeit später kommt die Diplompädagogin Jana Michels in das Heim, um im Rahmen eines Forschungsprojekts über die Zusammenarbeit von Jugendämtern und Kirchen eine Arbeit über die Entwicklung der diakonischen Jugendheime in Deutschland zu schreiben und Vorschläge zur Verbesserung zu machen. Nach zähen Gesprächen mit der Anstaltsleitung erreicht sie, dass die Jugendlichen nach dem Besuch des Bischofs eine Stunde Zeit für sich erhalten, ohne Überwachung. Paul und Luisa nutzen die Gelegenheit, um zu fliehen. Sie brechen in ein Bauernhaus ein, holen neue Kleider und essen etwas. Mit einem Mofa können sie dem zurückkehrenden Bauern entkommen, werden aber bald von der Polizei eingeholt und wieder ins Heim gebracht. Nach ihren Erfahrungen dort sind sie sicher, brutal bestraft zu werden. Luisa stürzt sich aus dem Fenster, überlebt aber und kommt ins Krankenhaus. Sie hat Glück und muss dank Janas Bemühungen nicht mehr ins Heim zurückkehren. Paul dagegen wird in ein Straflager geschickt, wo er zwei Jahre lang hart arbeiten muss, bis er nicht mehr „von Nutzen“ ist und wieder ins Kinderheim zurückgeschickt wird. Rezeption „Was man bisher nur aus abstrakten Erzählungen kannte, macht der Film emotional erfahrbar: Wie eine Gefangene wird Luisa herumkommandiert, ihr Haar wird geschoren, selbst ihre Identität wird ihr geraubt: Sie ist nicht mehr Luisa, sie ist nur noch eine Nummer. Beschwert sie sich, wird sie gemaßregelt, begehrt sie gegen Ungerechtigkeit auf, wird sie geschlagen. Die verliebten Blicke der Teenagerin, die sie dem Jungen Paul zuwirft, werden argwöhnisch von den verhärmten Schwestern registriert, Sexualität ist verboten, Freiheit ist verboten, Spaß ist verboten, alles ist verboten. Das Heim ist ein Gefängnis.[…] Die ehemaligen Heimkinder werden als Erwachsene dargestellt von Senta Berger und Matthias Habich – und diese Besetzung ist ausgezeichnet. Nicht nur, weil beide hervorragende Schauspieler sind und in der Lage, den naturgemäß etwas hölzernen Szenen vor dem Parlamentsausschuss Leben einzuhauchen. Sondern vor allem auch, weil die über viele Jahre stimm- und rechtlosen Heiminsassen, die vor Scham geschwiegen haben über ihr Schicksal, so ihrer Opferrolle entkommen. Zwei der besten deutschen Schauspieler spielen die Heiminsassen – das sind keine kaputten Existenzen, sondern Stars. ‚Und alle haben geschwiegen‘ gibt den Opfern zurück, was ihnen im Heim geraubt wurde: Ihre Würde“. (Stefan Kuzmany auf Spiegel.de) „Regisseur Dror Zahavi hat sich an das düstere Thema gewagt: das Versagen der deutschen Nachkriegspädagogik. Er beschönigt nichts, kommt ohne Voyeurismus aus: Nicht alle Schwestern sind Unmenschen, aber das System begünstigt die, denen das Quälen Spaß bereitet. Ein sehenswerter Film.“ (Monika Maier-Albang auf sueddeutsche.de Matthias Habich (* 12. Januar 1940 in Danzig) ist ein deutscher Schauspieler. Sein erster großer Erfolg ist 1973 die Hauptrolle im Fernseh-Sechsteiler Die merkwürdige Lebensgeschichte des Friedrich Freiherrn von der Trenck unter der Regie von Fritz Umgelter. Danach folgen mit Die unfreiwilligen Reisen des Moritz August Benjowski und Des Christoffel von Grimmelshausen abenteuerlicher Simplicissimus gleich zwei Vierteiler unter dem gleichen Regisseur mit ihm (beide ausgestrahlt 1975). Spätestens jetzt ist er einem breiten Fernsehpublikum in Deutschland bekannt. Sein Kinodebüt gibt Habich 1976 als eiskalter preußischer Offizier in Der Fangschuß. Es folgen Rollen in Kinofilmen. Nach zahlreichen Rollen in Theater und im Fernsehen spielt er sich 1999 mit der Hauptrolle in der TV-Serie Klemperer – Ein Leben in Deutschland endgültig in die erste Liga der deutschen Charakterdarsteller. 2001 erhält er den Deutschen Filmpreis für seine Leistung in Caroline Links vielfach preisgekröntem Drama Nirgendwo in Afrika. Im Kino ist er 2009 neben der internationalen Produktion Der Vorleser, an der Seite von Kate Winslet und Ralph Fiennes, auch im Drama Waffenstillstand zu sehen. Für seine Rolle im Fernsehfilm Ein halbes Leben erhält Habich gemeinsam mit seinen Schauspielerkollegen Josef Hader und Franziska Walser sowie Regisseur Nikolaus Leytner den Grimme-Preis. Nach zwei Kinofilmen 2010 wirkt Habich vor allem wieder in Fernsehproduktionen mit, u. a. 2012 im Thriller Das Kindermädchen, als Familienpatriarch, der mit der dunklen Vergangenheit seiner Familie konfrontiert wird. Unter der Regie von Margarethe von Trotta spielt Habich 2015 in Die abhandene Welt schließlich wieder eine Kinohauptrolle, als Witwer, der auf einem Zeitungsfoto seine angeblich tote Frau wiederzuerkennen glaubt. Mittlerweile hat Habich in circa 100 Film- und Fernsehproduktionen mitgewirkt. Er lebt in Paris, Zürich und Locarno.

0 notes

Text

We had to read Simplicius Simplicissimus (ger.: Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus) from Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen. I don't remember a lot of it, but I do remember that non of us could stand it. Then again, we read it in 7th grade [we were all 12 - 13 year old kids] and some teachers said they wouldn't read it with a class that young so maybe we just didn't understand it? I don't know but so far I'm not planning on rereading that.

what books were you assigned to read in a class that you still hold a violent and bitter grudge against

for me it’s into the wild and the scarlet letter

119K notes

·

View notes

Link

LibriVox turns 15 this month! In all these years, we have achieved many goals. Here are some gems from our catalog that seemed very ambitious when LibriVox first started out. But today, with more than 14,200 completed projects, they are just a small part of a much bigger whole.

Speaking about “whole”, let’s start with a complete set. Already back in 2012, we completed all plays by William Shakespeare. Add to this selections of favourite monologues and scenes from his plays and his sonnets, and you will find most of the great bard’s output here.

We are not quite there yet with Mark Twain, who wrote a tremendous number of books, short stories and newspaper articles. Our reader John Greenman is dedicated to record everything Twain has ever written, so of course he did one of the seven versions of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as well.

Wait – seven versions of the same book? Yes! We call this “choice of voice” and it’s unique to LibriVox. Many of our books have 2, 3, … 7 versions, but the most popular one amongs our readers is A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, with 11 completed versions to date.

Thinking about this a bit more though, if you count single pieces in our many collections, there is even more “choice of voice”. Probably the most recorded poem on LibriVox is by Edgar Allen Poe. The Raven has 25 versions in a number of English collections and an additional 22 in this multilingual one.

Yes of course, LibriVox loves languages too! So far, our catalog contains projects in 100 languages. Not every one of these is a completed stand-alone project though, but more than 50 different languages can be found in our collection of Multilingual Recordings of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

This leads us to the book with the most translations in our catalog. It is a classic adventure story by Jules Verne, who is just as popular among our readers as Charles Dickens. His fantastic story 20,000 Miles under the Sea is available in the original French and as translations into English, German, Spanish, and Dutch.

Speaking of classics, LibriVox has a wide selection from many different countries. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra is a wonderful book from Spain, and we have it in the original Spanish, and in translations into English, Dutch (adaptation) and German (first book only).

Or are you a Francophone? Then you must know Les Miserables, the tragic story in five volumes by Victor Hugo. You can listen to it in the original French, as well as in translations into English, Dutch, and (almost completed) Spanish.

One book that was published in many versions and translations over the centuries is the Bible. While LibriVox has many versions of various books of the Bible, we have three completed versions: The Spanish Reina Valera Version, the King James Version, and the World English Bible, a solo recording that is 100 hours long!

Not even Leo Tolstoy’s epic War and Peace is that long! Listening to every one of the 17 volumes takes a mere 3 days, 22 hours, and 40 minutes, which, to be fair, is also very ambitious, if you’d want to do it in one go.

Not every ambitious project is necessarily very long. Sometimes, it’s the difficulty of the text that makes recording it a challenge. One of these texts is Der Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch, a picaresque novel written in the 17th century by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen.

Although the language is significantly more modern, James Joyce’s Ulysses is also considered notoriously complicated. Our first version (of two) dates back to the early days of LibriVox and was completed in 2007. It is rather experimental and some chapters were recorded in live meetings of LibriVox volunteers.

Since these live group recordings need quite a bit of planning, there are only very few in our catalog. However, in 2010, our Dutch members pulled it off and met in person for a special recording for our 5th anniversary. The result is Natuurlijke Historie voor de Jeugd by De Schoolmeester.

Italian author and winner of the Nobel Prize Luigi Pirandello also had a big plan: He wanted to write 365 novellas and publish them in 24 volumes. However, he died too early to see his goal completed, but still, 15 volumes of the Novelle per un anno were published, and 13 of them can be found here.

So many ambitions fulfilled – and so many still in progress! Among our ongoing multi-volume projects that are yet only partially completed are The National Geographic Magazine (first 10 years completed), Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects (4 to go), and Library of the World’s Best Literature, Ancient and Modern (45 volumes in total).

For 15 years, we at LibriVox have been following our goal

To make all books in the public domain available, narrated by real people and distributed for free, in audio format on the internet.

And we will keep on doing just that! Together, we will make it happen! Thank you to all our volunteers who helped out over the years and whose smallest contribution brought us one step closer to reach our goal. If you want to be a part of this great project, you are certainly welcome to Volunteer for LibriVox.

On to the next 15 years!

via Libricox

0 notes

Video

youtube

Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch Teil 1 | Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen | Action & Adventure Fiction, War & Military Fiction | Audiobook full unabridged | German | 2/7 Content of the video and Sections beginning time (clickable) - Chapters of the audiobook: please see First comments under this video. Der Abentheuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch ist ein Schelmenroman von Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, erschienen 1668. Er wird gemeinhin als das wichtigste Werk seiner Art im 17. Jahrhundert betrachtet. Ferner gilt er als der erste deutschsprachige Abenteuerroman mit stark autobiographischen Zügen, da er die Lebenswege von Autor und Held im Dreißigjährigen Krieg (1618–1648) teilweise zusammenführt, ohne sie freilich zur Deckungsgleichheit zu bringen. (Summary nach Wikipedia) Prooflisteners: Al-Kadi, Buechermaus, Rolf Kaiser, Hokuspokus This is a Librivox recording. If you want to volunteer please visit https://librivox.org/ by Priceless Audiobooks

0 notes

Video

youtube

Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch Teil 1 | Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen | Action & Adventure Fiction, War & Military Fiction | Audiobook full unabridged | German | 3/7 Content of the video and Sections beginning time (clickable) - Chapters of the audiobook: please see First comments under this video. Der Abentheuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch ist ein Schelmenroman von Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, erschienen 1668. Er wird gemeinhin als das wichtigste Werk seiner Art im 17. Jahrhundert betrachtet. Ferner gilt er als der erste deutschsprachige Abenteuerroman mit stark autobiographischen Zügen, da er die Lebenswege von Autor und Held im Dreißigjährigen Krieg (1618–1648) teilweise zusammenführt, ohne sie freilich zur Deckungsgleichheit zu bringen. (Summary nach Wikipedia) Prooflisteners: Al-Kadi, Buechermaus, Rolf Kaiser, Hokuspokus This is a Librivox recording. If you want to volunteer please visit https://librivox.org/ by Priceless Audiobooks

0 notes

Video

youtube

Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch Teil 1 | Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen | Action & Adventure Fiction, War & Military Fiction | Audiobook full unabridged | German | 4/7 Content of the video and Sections beginning time (clickable) - Chapters of the audiobook: please see First comments under this video. Der Abentheuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch ist ein Schelmenroman von Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, erschienen 1668. Er wird gemeinhin als das wichtigste Werk seiner Art im 17. Jahrhundert betrachtet. Ferner gilt er als der erste deutschsprachige Abenteuerroman mit stark autobiographischen Zügen, da er die Lebenswege von Autor und Held im Dreißigjährigen Krieg (1618–1648) teilweise zusammenführt, ohne sie freilich zur Deckungsgleichheit zu bringen. (Summary nach Wikipedia) Prooflisteners: Al-Kadi, Buechermaus, Rolf Kaiser, Hokuspokus This is a Librivox recording. If you want to volunteer please visit https://librivox.org/ by Priceless Audiobooks

0 notes