#d3a

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kim, Franzi and Marie when they are about to ruin your life 😌

#kim jülich#franzi winkler#marie grevenbroich#die drei ausrufezeichen serie#die drei ausrufezeichen#d3a#die drei !!!#the three detectives#My stuff D3A edition

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tag 5

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 December 1941. Aichi D3A1 Type 99 Model 11 ‘Val’. The primary dive bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy, it was involved in almost all their actions, including the attack on Pearl Harbour.

@ron_eisele via X

#d3a val#aiachi aviation#dive bomber#aircraft#ww2 history#ww2 aircraft#ww2#pacific theater#imperial japanese navy#ww2 aviation#wwii aircraft#wwii planes

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Die-Drei-Ausrufezeichen-Monat Prompts

Ein kleines Projekt um endlich mal Schwung in den Fan Kreationen für Die Drei Ausrufezeichen zu bringen.

Typischer „…-Monat“ Aufbau.

Für jeden Tag habe ich prompts zusammen gewürfelt, bestehend aus einer Folgen/Band Nummer und einem typischen Fan Fiction Trope.

Jegliche Form von Fan Kreation kann genutzt werden. Fan Art, Fan Fic, Moodboards, Edits und Meme Posts wären auch möglich. (Und falls euch noch andere Formen einfallen, die natürlich auch!)

Mein Ziel ist es für jeden Tag eine Fan Fiction zu schreiben und zu veröffentlichen. Vielleicht werde ich auch noch zusätzlich mal Meme Posts oder moodboards posten. Es muss auch nicht jeden Tag ein Prompt genutzt werden und auch nicht zu jedem was gemacht werden. Das ist nur mein persönliches Ziel und ich wollte euch einladen vielleicht mit zumachen!

Der Fokus sollte auf Nebencharakteren liegen oder zumindest zum Teil. z.B. Haupt+Nebencharakter Dynamik (Aber natürlich kein Muss.)

Falls ihr die Dinge die ihr macht hier postet, wäre den Blog zu markieren ganz nett. :)

Falls ihr Fics auf AO3 veröffentlicht, wäre ein Link cool. Ich habe vor eine Collection für diese Aktion zu machen.

Geplanter Start ist am 04.08

(Früheres anfangen oder späteres Einsteigen ist auch völlig okay. Ergo auch nach den 31 Tagen noch.)

1. 52 | Coffee Shop AU

2. 68 | Fake Relationship

3. 76 | Sick Fic

4. 53 | Fake relationship

5. 43 | Time Travel Fix it

6. 36 | Crack Fic

7. 65 | First Kiss

8. 11 | First Kiss

9. 34 | Amnesia

10. 2 | missing scene

11. 71 | Fake Relationship

12. 28 | Sharing a bed

13. 47 | Huddle for warmth

14. 21 | unrequited love

15. 81 | Sharing a bed

16. 35 | Hurt/Comfort

17. 83 | established relationship

18. 24 | fairytale AU

19. 78 | Tattoo artist x florist AU

20. 17 | sad ending

21. 3 | mutual pining

22. 54 | sad ending

23. 22 | Misscommunication

24. 41 | First kiss

25. 72 | Mutual pining

26. 85 | Major Character Death

27. 80 | enemies to lovers

28. 1 | miscommunication

29. 8 | Tattoo Artists x Florist AU

30. 26 | Hurt/Comfort

31. 74 | amnesia

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay, so here is the thing. XD Yes, they do have their fair share of episodes including them crushing on boys. But. But. Listening to them again when you are older you notice, funny enough they are also very queer (like I had not realised how much til I started listing to the audio dramas again). Like definitely some sapphic stuff going on there, kinda like with the dynamic between Justus, Peter and Bob actually being fairly queer in one way or another. Kim, Franzi and Marie´s dynamic is actually way queerer, than you might remember. One thing for example living in my mind rent free is that one time where Marie was going on about how pretty Franzis eyes are.

“Drei Fragezeichen AU where they’re all lesbians” isn’t that just Die drei Ausrufezeichen

I... I didn't expect this but I highly appreciate it, even though I rarely remember anything about doe drei Ausrufezeichen anymore. But didn't they have hilariously many episodes with drama about specific boys?

#I might be biased looking at my blog name but the point still stands /j#and also the fact that movie Marie was very very sapphic in my humble opinion#(sapphic Marie really saves this movie. besides that I´m like... it exists for sure)#Queering Die Drei Ausrufezeichen#feels appropriate here XD#reblog + response#die drei ausrufezeichen#d3a#die drei !!!

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tag 3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1942 06 04 Midway - Just Another Hole in My Head - Roy Grinnell

Second Lieutenant Charles M. Kunz, attached to the 221st Marine Fighter Sqdr, was at Midway. When the battle began he flew his first combat mission in a Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo. Kunz shot down two Aichi D3A Val, being injured in the process. When he landed, he downplayed his injuries, saying "it's just another hole in my head." In the words of Charles: "I saw tracers go through my cockpit and rip my wings. I would make violent turns hoping that the enemy would not be able to follow me. I was continuing to fly at full throttle and performing those maneuvers when I was hit in the head by a shard. My plane was seriously damaged and I knew I wouldn't be able to attack again, so I headed to the island and landed." Lieutenant Kunz was decorated with the Naval Cross for his action at Midway.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A Japanese D3A Val shot down by Naval gunfire lies in the water off Guam beach as Marines continue to stream ashore. Agat Beachhead." However, a handwritten note on the back asserts that that plane could not have been shot down, as no Japanese planes opposed the landings. July 21, 1944.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danke danke danke für diese Beschreibung der Reihe. Fast es echt gut zusammen finde ich. Und jaaa, ich liebe das die drei Ausrufezeichen Fälle so character driven sind echt total. Eine der Sachen die ich an der Reihe liebe ist das sie gesellschaftliche Themen eigentlich ganz gut aufarbeiten. Zumindest in den „späteren Fällen“. Die Probleme der ersten Folgen Stichwort Diat Culture und ein negatives Selbstbild bei Kim werden relative „schnell“ fallen gelassen bzw. aufgearbeitet im Vergleich zu dem immer noch in den Die drei Fragezeichen existierenden ziemlich präsenten Fat Shaming. Und ja, nichts stört mich mehr als Leute die über die drei Ausrufezeichen herziehen und es einfach nur als den "Mädchenkram" oder alternativ "das ist einfach nur voll misogyn" abtun.

In letzer Zeit bin ich recht obsessed mit den drei Ausrufezeichen/ Die drei !!!. Und bevor jemand kommt „die sind ja nur ein billiger ??? Abklatsch aber mit Mädchen“, das wird sogar in Universe angesprochen, keine Sorge.

Die Fälle sind nicht soo anspruchsvoll, aber die Geschichten sind stark character driven, was ich mag. Es gibt eine logische Entwicklung der Charaktere, es gibt Veränderungen und es wird mit sensiblen Themen wie Fremdenhass, Suizid und dem Tod sehr verantwortungsvoll umgegangen. Und letztens gab es auch den ersten LGBT+ Charakter :) Alles in allem mag ich die Bücher und die Hörspiele sehr und finde es schade, dass die Reihe als purer Mädchenkram abgetan wird

Oben sind die drei Hauptcharaktere Kim, Franzi und Marie zu sehen, unten Kommissar Peters, der engste Vertraute der drei und die (mahnende) Stimme der Vernunft in vielen Fällen.

#rebloging this as the first thing#because yes#thank you for being literally the only person I have seen make fan art of them#and for just liking them#part of the reason I actually feel comfortable to make this blog#I love your fan art so much#gonna go on a reblog spree of your art after this haha#D3A fan art#kim jülich#franzi winkler#marie grevenbroich#kommisar peters#die drei ausrufezeichen#D3A#Die drei !!!#reblog + thoughts

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marine Air’s Dark Day at Midway

Marine Aircraft Group 22’s experience at the Battle of Midway serves as a hard lesson in trying to do too much with too little.

The 4th of June 1942 was a very bad day for Marine Corps aviation. At the Battle of Midway, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 22 suffered terrible losses and contributed little to the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s spectacular victory that day. The group’s fighting squadron, VMF-221, lost far more aircraft than its pilots shot down. Its dive-bomber squadron, VMSB-241, suffered staggering losses without hitting a single Japanese ship.

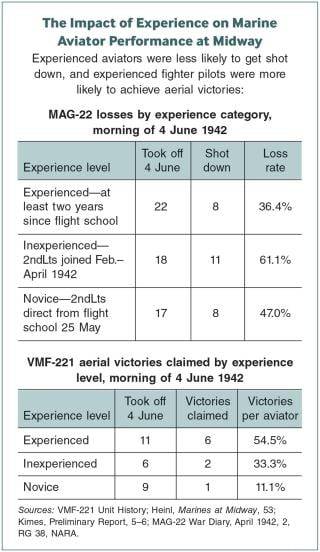

Midway historians have thoroughly chronicled the actions of these two squadrons and touched on some reasons for their performance. The most cited causes are the obsolescence of Marine aircraft and the inexperience of Marine aviators.1 A closer examination of archival material reveals additional factors that impaired the group’s performance at Midway and new insights into why MAG-22 sent such green pilots into battle.

The heart of MAG-22’s troubles lay in its two competing missions: While forward deployed to defend an advanced base, the group also served as a de facto training command for new aviators. This alone would have undermined its combat readiness. But additional factors worked against MAG-22. In the weeks before the battle, the flight hours the group devoted to training were limited by its responsibilities to defend Midway Atoll and by logistical shortfalls. During the battle, Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 were unable to coordinate aircraft from three services based at the atoll. Finally, imprecise direction from Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz led to misunderstandings of how MAG-22 would employ its fighting squadron.

Present-day naval commanders are acutely familiar with the challenge of balancing combat readiness and forward presence. As naval leaders look for ways to maintain Navy and Marine Corps forces in the western Pacific and prepare for possible conflict there, the experience of MAG-22 at Midway provides a sobering reminder of the risks of attempting to do too much with too little.

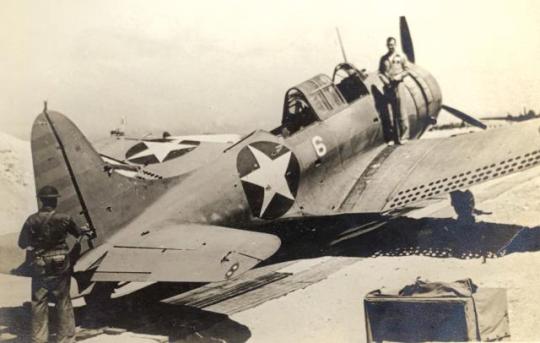

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. National Naval Aviation Museum

MAG-22’s Very Bad Day

At 0555 on 4 June 1942, Midway’s radar detected a large formation of aircraft 93 miles northwest of the atoll. MAG-22’s siren wailed. In accordance with orders issued the previous evening by Lieutenant Colonel Ira L. Kimes, the commander of MAG-22, VMF-221 launched its aircraft immediately. A detachment of six Navy TBF Avengers took off next, followed by four Army Air Forces B-26 Marauders armed with torpedoes. The TBFs and B-26s proceeded independently to attack the Japanese carriers. The 16 SBD-2 Dauntlesses and 12 SB2U-3 Vindicators of VMSB-241 took off last and rendezvoused about 20 miles east of Midway’s Eastern Island.2

VMF-221’s commanding officer, Major Floyd B. Parks, had organized his 21 F2A-3 Buffalos and seven F4F-3 Wildcats into four divisions of Buffalos and one of Wildcats. All but one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 were mission ready and got airborne, though the divisions became slightly disorganized during the hasty scramble. The Japanese strike consisted of 108 aircraft—36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, 36 Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” carrier attack aircraft, and 36 Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zeke,” or Zero, fighters. In accordance with Kimes’ plan, MAG-22’s fighter direction center funneled all five of VMF-221’s divisions to intercept the incoming strike. The Marines had the altitude advantage, and the separate divisions launched a series of overhead gunnery passes against the Japanese bomber formations. As the slower Marine aircraft recovered for additional passes, the nimbler Zeros overtook them and sent one after another tumbling downward.3

There is little doubt VMF-221 got the worst of the fight. The Japanese shot down 15 Marine fighters and severely damaged another nine, leaving just one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 ready to fly. Though Kimes afterward estimated Japanese losses at 43 aircraft, his surviving pilots definitively claimed just nine victories. Kimes’ estimate included “probable victories by missing fighter pilots” as well as claims by rear-seat gunners of VMSB-241.4 The actual total was far lower. VMF-221 probably shot down just three aircraft outright. Another 16 Japanese aircraft survived the raid but either ditched or were so irreparably damaged they could not fly again.5

A PBY Catalina flying boat had spotted the Japanese carriers, and MAG-22 passed their location to VMSB-241.6 Major Lofton R. Henderson, the squadron commander, led the SBDs. Major Benjamin W. Norris, the executive officer, led the SB2Us. While Henderson took his unit to 9,000 feet, Norris climbed to 13,000 feet.7 On paper, the SB2U-3s were nearly as fast as the SBD-2s, but the two flights proceeded independently.8

Because the Marine dive bombers were slower than the TBFs and B-26s, had taken off last, and had flown east before heading northwest, VMSB-241 did not attack until a half hour after the TBF and B-26 attacks had ended. The Japanese combat air patrol had shot down five of the six Avengers and two of the four Marauders; none had scored a hit. When Henderson and his SBDs spotted the carrier Hiryū at about 0755, the Japanese combat air patrol still had 13 fighters aloft.9

Henderson conducted a glide-bombing attack. A dive-bombing attack would have facilitated bombing accuracy and complicated fighter gunnery and antiaircraft solutions. But more than half of Henderson’s pilots were too inexperienced to attempt the technique, and the cloud cover would have made dive bombing particularly difficult.10

The combat air patrol’s Zeros attacked Henderson first. On their second pass, they sent him down in flames. The remaining SBDs continued the gliding attack. One by one, the Marines released their bombs—and missed. Some came petrifyingly close for the Hiryū’s crew, and many Marines mistakenly believed they had scored hits.11

Norris and his Vindicators arrived at about 0820, less than ten minutes after the surviving SBD-2s had departed and amid an attack by Army Air Forces B-17 Flying Fortresses. The combat air patrol had doubled to 26 fighters. Norris descended through the clouds toward the carrier Akagi. The Zeros could not find the dive bombers as long as they were in the safety of the cloud bank, but neither could the Marines see the ships below. When they emerged at 2,000 feet, they saw only the battleship Haruna. Norris also attempted a gliding attack. The Haruna maneuvered evasively, neatly avoiding every one of the Marines’ bombs. The SB2Us hugged the surface and flew back to Midway.12 Only 8 of VMSB-241’s 16 SBD-2s and 8 of its 12 SB2U-3s returned.13

VMSB-241 conducted two more strikes during the battle. That evening Norris led five SB2U-3s and six SBD-2s in a vain search for burning carriers. They found nothing, and Norris did not return, lost in the inky, moonless squalls. On 5 June, VMSB-241 attacked the cruisers Mogami and Mikuma. The squadron lost another Vindicator to antiaircraft fire and again scored no hits.14

What Was Done Well

MAG-22 did some things remarkably well in its first action. Due to superb intelligence and early warning, no airworthy planes were caught on the ground. The fighter direction center placed the fighters in an optimum intercept position. The dive bombers located the Japanese carriers. Most impressively, every fighter and dive-bomber pilot attacked without hesitation into the teeth of a formidable defense.

MAG-22’s efforts indirectly contributed to the destruction of the Akagi and two other carriers, the Kaga and Sōryū, later that morning. As historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully demonstrated, the cumulative effect of the series of failed attacks by bombers from Midway and U.S. carriers created conditions that delayed Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s counterattack and placed his carriers at greater vulnerability to the dive bombers from the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and Yorktown (CV-5). Dodging the attacks required the carriers to maneuver violently. Defending against them required the carriers to launch and recover fighters. Perhaps just as important, Nagumo faced a series of menacing dilemmas, complicating his decision-making. When the dive bombers from the Enterprise and Yorktown appeared overhead at 1020, Kates and Vals were still below on the hangar decks, where their fuel and ordnance amplified the destructive power of the American bombs.15

VMF-221 also helped reduce the strength of Nagumo’s counterpunch when it did come. The only carrier that survived the Enterprise and Yorktown dive-bomber attacks was the Hiryū. It was her air group that VMF-221 had attacked. Though the Marine fighters shot down just two Kates outright, another seven Kates were shot down by Marine antiaircraft guns, ditched, or were too damaged to participate in the strikes against the U.S. carriers.16 In other words, the Marines did not bring down many aircraft, but the ones they did bring down were the right ones—aircraft from the Hiryū’s air group.

Nonetheless, 4 June had been an awful day for MAG-22. It had lost many aircraft, shot down only a handful of the enemy, and hit no ships. Forty-two MAG-22 Marines had died; 36 pilots and gunners were missing; and six Marines had been killed in the bombing of Eastern Island.17

‘Not a Combat Airplane’

On 17 April, Major (soon to be Lieutenant Colonel) Ira L. Kimes (below) landed at Midway Atoll to replace Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace as MAG-22 commander. Accompanying Kimes were six second lieutenants, green aviators who replaced six captains, seasoned fliers, who left the atoll with Wallace three days later. Public Domain

Every surviving Marine fighter pilot from VMF-221 attested to the superiority of the Zero over the Marine fighters. Captain

The F2A-3 is not a combat airplane. It is inferior to the planes we were fighting in every respect.

It is my belief that any commander that orders pilots out for combat in a F2A-3 should consider the pilot as lost before leaving the ground.18

Kimes agreed. In his endorsement to his aviator’s statements, Kimes recommended that the fleet relegate the F2A-3 Buffalo, the F4F-3 Wildcat, and the SB2U-3 Vindicator to training commands.19

The Vindicator was indeed past its usefulness. However, there is evidence that neither fighter was to blame for VMF-221’s poor performance. With improved tactics, Marine and Navy pilots would achieve far better results with the F4F in the Solomons. Captain Marion Carl, the only Marine to shoot down a Zero over Midway, believed the F2A-3 was as maneuverable and fast as the F4F-3, and its only drawbacks were that it could not absorb punishment and was less stable as a gunnery platform than the Wildcat.20

Some British and Dutch Buffalo aces, whose squadrons suffered grievously against Imperial Japanese Navy Zeros, attributed their lopsided outcome to Japanese proficiency and numbers rather than the Buffalo’s inferiority. Finnish Buffalo pilots enjoyed great success flying the planes against the Soviets.21 The Buffalo’s mixed performance in other theaters suggests that other factors contributed to VMF-221’s poor performance.

‘Half-Baked Flyers’

When VMF-221 and VMSB-241 had landed on Eastern Island in December 1941, both squadrons were top heavy with experience. VMF-221’s most junior pilot had been flying for at least a year since flight school.22 But the 57 aviators who flew on 4 June included 35 second lieutenants, none of whom had been with their squadron more than four months, and 17 of whom had arrived on 27 May directly from flight school.23

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles.

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

In the first half of 1942, Marine aviation had two conflicting missions: defending the fleet’s advanced bases and training new aviators. Newly winged aviators reported to the fleet with just 200 hours of flight time, and none in the aircraft they would fly in combat.24 The new aviators needed operational training, but the aircraft they needed to train in were defending advanced bases in the Pacific.

On 8 January 1942, Brigadier General Ross E. Rowell, the commander of 2d Marine Air Wing, described the dilemma in a letter to Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., the commander of Aircraft, Battle Force, Pacific Fleet: “I have now accumulated 35 second lieutenants in various stages of advanced training. . . . If ComAirBatFor approves and you want some half-baked flyers, send me a dispatch to that effect.” Halsey approved; he directed Rowell to order the green fliers to squadrons like VMF-221 and VMSB-241.25 This decision set in motion a sequence of personnel transfers that diluted the combat readiness of forward-deployed squadrons. As inexperienced aviators joined squadrons at advanced bases, experienced aviators left to form new squadrons in Hawaii and California.

Marine aviation was still following its prewar training pipeline. Once students were designated naval aviators, they reported to squadrons in the Fleet Marine Force for about a year of operational flight training in combat aircraft.26

Not only did MAG-22 not have a year to train its new aviators, but the group’s commitment to the defense of Midway also required it to devote most of its operational flights to patrols and radar calibration vice gunnery and tactics. Less than 30 percent of VMF-221’s missions from December 1941 to May 1942 were dedicated to improving the lethality of its fighter pilots.27

Logistics shortfalls further impinged on the group’s training. A shortage of .50-caliber machine-gun ammunition often limited gunnery practice to dummy runs.28 In the final week before combat, PBY Catalinas and B-17 Flying Fortresses drew thirstily from Midway’s fuel stocks, which were already limited due to an incredible blunder. On 22 May, demolition charges placed at an underground fuel storage facility detonated when one of the defense battalion batteries fired its 11-inch guns. The station lost 375,000 gallons of precious aviation fuel and its pipeline to Eastern Island.29 The resulting shortage prevented the group from providing the 17 Marines fresh out of flight school with anything more than familiarization flights. VMSB-241 could not even check out its new pilots in their SBDs.30

Without question, MAG-22 fought the Battle of Midway with inferior aircraft and many “half-baked” pilots. Though the odds were stacked against the group’s aviators, command decisions may have stacked the odds higher than they needed to be.

‘No Organized Plan Whatsoever’

In a 1966 interview, MAG-22’s former executive officer stated there had been “no organized plan whatsoever” to coordinate Midway’s Army Air Forces, Navy, and Marine aircraft.31 Though not strictly true, his characterization betrays how Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 struggled to coordinate air operations.

In anticipation of the coming fight, Nimitz had abundantly reinforced Midway. In addition to MAG-22, Midway’s air force included 31 PBYs, 17 B-17s, the 4 B-26s, and the 6 TBFs. Nimitz assigned tactical control of all these to the naval air station commander, Navy Captain Cyril T. Simard, and sent an experienced aviator and a naval base air defense detachment to coordinate air operations.32

While the naval air station directed scouting operations superbly, integrating the bombers in a coordinated strike proved beyond its reach. Each aircraft type attacked without regard to the next, permitting the Japanese the opportunity to fend off each in turn. As Kimes observed in perfect hindsight, “It would have been better had they arrived simultaneously.”33

Coordination was exacerbated by the physical separation of the naval air station and MAG-22 command posts. Simard and his air operations officer were on Sand Island; Kimes and his command post were on Eastern Island. According to Kimes’ executive officer, the “Marines ran their own show” but did not command the other services’ bombers on Eastern Island, including the six Navy TBFs.34

Kimes’ air group struggled to coordinate its own aircraft. VMSB-241 does not seem to have attempted to integrate its SBD and SB2U attacks. Most puzzlingly, MAG-22 allocated no fighter protection to VMSB-241 for its strike against the Japanese carriers.

‘Go All Out for the Carriers’

Kimes employed his fighting squadron in what Marine Corps doctrine termed “general support.” As then–Major William J. Wallace lectured Marine officers at Quantico in 1941, general support was an offensive mission that allowed fighters the freedom to be “on the prowl.” In contrast, missions that tied fighters to protection missions, such as escorting bombers, were termed “special support.” As a fighter pilot, Wallace clearly favored the freedom to go find trouble and emphasized, “The rule, then, for the employment of fighter units should be-—general support wherever and whenever possible.”35

In January 1942, now–Lieutenant Colonel Wallace took command of Marine aviation on Midway, which he retained until relieved by Kimes in April. It was Wallace who had developed the fighter direction system MAG-22 employed for defense of the atoll. As Wallace’s views on fighter employment reflected Marine Corps doctrine, and Wallace commanded MAG-22 until two months before the battle, this bias likely influenced Kimes’ decision to place all of VMF-221 in general support on 4 June.

MAG-22’s fighter employment stands in stark contrast to how Japanese and U.S. carrier task forces operated on 4 June. Carriers were far more vulnerable to air attack than an island base. Nonetheless, every Japanese and American task force commander allocated fighter escorts to increase their bombers’ chances of getting through the enemy’s fighters.

Hitting the Japanese fleet was exactly what Nimitz had in mind when he reinforced Midway with so many aircraft. On 20 May, Nimitz provided the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King, with some views on the role of land-based aircraft he had drawn from the recent Battle of the Coral Sea:

The shore commander should assign attack missions designed to render the greatest possible assistance to the Fleet Task Force when it is engaged and should particularly be ready to provide fighter protection when it is practicable.36

Nimitz incorporated these views in his planning guidance for Midway. In a 23 May memorandum to his chief of staff, Captain Milo F. Draemel, Nimitz explicitly directed that “Midway planes must thus make the CV’s [aircraft carriers] their objective, rather than attempting any local defense of the atoll.”37 In an undated memorandum likely written about the same time, Nimitz reiterated his intent to Captain Arthur C. Davis, his air officer:

Balsa’s [Midway’s] air force must be employed to inflict prompt and early damage to Jap carrier flight decks if recurring attacks are to be stopped. Our objectives will be first—their flight decks rather than attempting to fight off the initial attacks on Balsa. . . . If this is correct, Balsa air force . . . should go all out for the carriers . . . leaving to Balsa’s guns the first defense of the field.38

But in his operations order for Midway, Nimitz was less clear in the tasks he assigned to Simard at Midway:

(1) Hold MIDWAY.

(2) Aircraft obtain and report early information of enemy advance by searches to maximum practicable radius from MIDWAY covering daily the greatest arc possible with the number of planes available between true bearings from MIDWAY clockwise two hundred degrees dash twenty degrees. Inflict maximum damage on enemy, particularly carriers, battleships, and transports.

(3) Take every precaution against being destroyed on the ground or water. Long range aircraft retire to OAHU when necessary to avoid such destruction. Patrol planes fuel from AVD [seaplane tender] at French Frigate Shoals if necessary.

(4) Patrol craft patrol approaches; exploit favorable opportunities to attack carriers, battleships, transports, and auxiliaries. Observe KURE and PEARL and HERMES REEF. Give prompt warning of approaching enemy forces.

(5) Keep Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander Hawaiian Sea Frontier fully informed of air searches and other air operations; also the weather encountered by search planes.39

The very explicit language Nimitz used in his planning guidance—that Midway’s aircraft “should go all out for the carriers”—is not reflected in his order. Absent such direction, Simard left it to Kimes to command the Marine squadrons as he saw fit. In accordance with Marine Corps doctrine, Kimes placed his fighting squadron in general support over Midway—and sent his dive bombers against the Japanese fleet without fighter escorts. Had he allocated one or two divisions from VMF-221 to escort VMSB-241, more Marine dive bombers may have survived to drop bombs on the Hiryū, and their accuracy may have improved had they attacked with less interference from the Japanese combat air patrol.

Trying to Do More with Less

MAG-22 had not gone all out for the carriers but had massed its fighters in defense of Midway. Naval Air Station Midway had struck the Japanese carriers with every bomber available but had been unable to coordinate their attacks to increase their chances for success and survival. Most tragically, many of the Marines lost in the battle were just not ready to fight the Imperial Japanese Navy, despite their willingness and eagerness to try.

MAG-22’s very bad day is a cautionary tale. Trying to do more with less—in MAG-22’s case, trying to defend Midway while training novice aviators—carries risks that may be hidden until they are exposed through combat. In his report of the battle, Kimes included a page and a half of candid comments and recommendations.40 After Midway, Marine aviators applied the lessons MAG-22 had learned at enormous cost and achieved spectacular results against the same foe in the Solomons, often under the leadership of aviators who had survived Midway.

Those same lessons are noteworthy today. Naval experts have cautioned the naval services against maintaining too much forward presence with too little fleet.41 An enduring lesson of MAG-22 may be that very bad days result from very bad choices, and that choosing to do more with less is often a very bad choice.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

just saw somebody censor the word ‘death’ on Facebook by writing it as ‘d3a+h’ and I’m once again filled with hatred for this method of unnecessary and ridiculous censorship in words 🙃

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Japanese Navy

On April 5, 1942, the Type 99 ship-borne bomber launched from the aircraft carrier Mizuku

@Matsuda_HI via X

#d3a val#aichi aviation#dive bomber#aircraft#imperial japanese navy#ww2 history#ww2#ww2 aircraft#pacific theater#ww2 aviation#wwii aircraft#wwii planes

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kim -> Autistic

Franzi -> ADHD

Marie -> AuDHD

Every good triad ship has one autistic person, one ADHDer and one AuHDer and I will not take criticism.

#I mean sometimes Kim also has ADHD energy but 🤷#Autistic Kim Jülich#ADHD Franzi Winkler#AuDHD Marie Grevenbroich#kim/franzi/marie#kim jülich#franzi winkler#marie grevenbroich#die drei ausrufezeichen#d3a#die drei !!!#self reblog#My stuff D3A edition

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

-> A message blinked on Alty's palmhusk. It was from temporalAbstraction [TA]. That was Gochov, what could he want? [TA]: _)) Y0u aren't busy with anything. I'm here t0 ap0l0gize f0r my sudden absence. [TA]: _)) S0mething happened and. I d0n't kn0w if y0u'll believe me 0r n0t.

[BD]: You hav3 no -d3a what - was do-ng [BD]: R3al abl3-st of you to assum3 -'m always do-ng noth-ng you know [BD]: But 3nough about how you should be canc3l3d [BD]: Th-s b3tt3r b3 a good apology [BD]: And a sch3dul3d dat3 n-ght [BD]: Plus at l3ast thr33 curs3d m3m3s

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heyaaa strangers!! :] I'm back- sorry I forgot 2 post 1 of these yesterday!!..

This is "Courtney was Caught" Courtney's d3a*h technically-

Im sorry if it looks/sounds cringe/weird.. I tried my best honestly.. so ya..

Hope u like it thou!! Took me awhile 2 do even thou its only 24 sec long.. but ya hope u like it seya later with another 1 soon ig..

[P.s. I posted this at 4 am almost 5 am cause I'm awake so why not I was gonna post this around 2 am but I didnt- I know I'm awake on a school night all because I woke up at 2 am but ya seya guys soon ig-..] :]

#IOTS#TDI#TDI Courtney#TDI Duncan#TDI Gwen#Total Drama Island#Duncney#Island of the Slaughtered#eavee ry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aichi D3A (Val)

WWll Japanese carrier-based bomber

4 notes

·

View notes