#czech karst

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“There are some that suggest that areas of heavy limestone have some sort of connection to paranormal events.”

I’m watching a video about the hauntings of Houska Castle in the Czech Republic, and this line came out, and I just …

Okay. Noodling around, apparently this is about properties of limestone as a material (made of deceased organic creatures, so more psychically permeable), which is a whole different ballgame, but if it was about limestone areas, I can tell you exactly why they’re associated with hauntings and other mysterious things.

It’s because they’re full of fucking holes.

Limestone is ridiculously vulnerable to water, and karst caves can be fucking huge. As an exercise, hop over to wikipedia’s list of longest cave systems in the world, and head down through the list, and see how many of them are limestone (with some gypsum for variety). The same for the list of deepest cave systems. Limestone areas are often just riddled with gaps and holes and weird formations, and weird noises from weird formations, and people vanishing because goddamn holes opened up under them when a below-ground cave finally got eaten enough to collapse. They’re just …

Limestone areas are full of caves. The caves go long and deep and weird. People hide in them. People die in them. People vanish near them. They’re just full of holes. So yeah, they’ve a reputation for weird shit and people going missing. Because they’re full of holes.

Sorry. I’m actually not opposed to paranormal stuff. I quite like ghost stories and paranormal exploration and all of that. Just. Talk about the actual natural causes first?

Especially since this particular case, Houska Castle, the whole thing is that a bottomless pit opened up in the limestone under it and is rumoured to descend to hell. And like. Yes? It’s limestone. That shit do happen.

The stories are really fun, though.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went to a presentation about the discoveries in Králova jeskyně ("the King's Cave", except it's actually named after a speleolog named Král) in the hill Květnice, here in Czechia. The cave was only discovered in 1972, because a dog fell into it - no one had even believed there could be karst caves there, but they are, and the more they find of them the more they realise they're pretty amazing. They recently found this amazing calcite pond with crystals.

The pond is under two meters in diameter and the crystals are up to an inch in size. So fairly small, but still incredibly impressive and amazing.

They said it's so recent they haven't yet had time to figure out if there's anything like it anywhere else in the world, only that it's unique in the context of Moravia as far as we know so far. Which is part of the reason I'm posting about it - in this particular case they're all volunteers, and I thought if by any chance this post finds someone who knows from speleology and knows of something comparable, maybe they'd welcome some input. It sounded like they would be glad to know if it really is unique or if there's anything like it out there, and how come this sort of thing happens. Here's the website of the Czech Speleological Society in case you are that sort of person.

It's not open to public - very narrow caves, no way to let people in without destroying it. They only let people in Králova jeskyně once a year, into a fraction of the spaces they know of, and smaller children in particular can only enter a really small fraction because the rest involves crawling and climbing and requires helmets. They said even just that one annual open door day and their own working in the cave for 50+ years has been enough to mess with the climate and processes inside a bit. (The entry fees from the annual open door day help fund the exploration of the cave.)

So you just have to admire the pictures.

source - Czech news article, photos by Michal Beneš, one of the volunteer speleologists who explore and look after the cave.

Made me think of Gimli and the Glittering Caves, let me tell you. Soooo amazing.

(It's also an important roosting place for bats. They said they know of eight species that winter there, and that, as they keep finding new sections of the cave, they also keep finding bats and finding out bats have their own ways of getting in, so no one really knows for sure how many bats actually live there.)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

21 Facts about the 𝗖𝘇𝗲𝗰𝗵 𝗥𝗲𝗽𝘂𝗯𝗹𝗶𝗰:

1. The Czech Republic was formed in 1993, following the peaceful split of Czechoslovakia in what is known as the Velvet Divorce.

2. The country is home to over 2,000 castles, making it one of the highest densities of castles in the world.

3. Prague, the capital city, is home to the largest ancient castle in the world, Prague Castle, according to the Guinness Book of World Records.

4. The Czech Republic is the birthplace of the world-famous Pilsner lager, originating from the city of Plzeň (Pilsen) in 1842.

5. The country has a long tradition of puppetry and marionette exhibitions. Puppetry was added to UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2016.

6. The Gregor Mendel, the founder of genetics, was born in 1822 in what is now the Czech Republic.

7. The Czech Republic ranks as one of the top countries in terms of beer consumption per capita. The tradition of brewing dates back to the 10th century.

8. The currency used is the Czech koruna (CZK), as the country has not adopted the Euro.

9. The Charles University in Prague, established in 1348, is one of the oldest universities in the world.

10. The traditional Christmas dinner in the Czech Republic often includes carp, which families sometimes keep alive in their bathtubs before preparing it for the meal.

11. The Czech Republic is the birthplace of the renowned Art Nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha.

12. The country's landscape is quite diverse, including bohemian paradise's rock cities, Moravian karst caves, and mountain ranges like the Krkonoše, home to the highest peak in the country, Sněžka.

13. The Czech Republic is known for its spa towns, including Karlovy Vary, Mariánské Lázně, and Františkovy Lázně, attracting visitors seeking relaxation and therapeutic treatments.

14. The Moravian Karst, a protected nature reserve in the eastern part of the Czech Republic, features more than 1,000 known caves and gorges.

15. The Velocipedes Museum in Česká Třebová is one of the world's largest museums dedicated to bicycles and motorcycles.

16. The Czech language belongs to the West Slavic group of languages and is known for its challenging pronunciation and grammar.

17. Traditional Czech glassmaking and crystal production have a long history, with Bohemian crystal being highly prized worldwide.

18. The Olomouc cheese, known as Olomoucké syrečky or tvarůžky, is a smelly, aged cheese from the region of Olomouc, famous throughout the country.

19. The Czech Republic has a significant tradition of animation and film, with filmmakers like Jan Švankmajer gaining international acclaim.

20. Kutná Hora, a town in the Czech Republic, is home to the Sedlec Ossuary, a small Roman Catholic chapel, adorned with decorations made out of human bones.

21. The Czech Republic was the first former Eastern Bloc state to gain developed economy status according to the World Bank, showcasing its successful transition from a state-controlled economy to a market-driven one.

#czech republic#ancestors alive!#what is remembered lives#memory & spirit of place#ancient ways#sacred ways#folkways#traditions

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Top 10 Most Beautiful Places to Visit in Czech Republic | Breathtaking Destinations | Life Travel

https://expedia.com/affiliate/7UOXNXE

https://airalo.tp.st/UYXhV3Jr

http://knowledgeglaxy.com/travels/

Description:

Discover the most beautiful destinations in the Czech Republic! From the charming streets of Prague to fairy-tale castles, breathtaking nature, and historic towns, this list showcases must-visit places in one of Europe’s most stunning countries.

🌍 Places Featured: 1️⃣ Prague – Charles Bridge, Astronomical Clock & Prague Castle 2️⃣ Český Krumlov – A fairy-tale town with a stunning castle 3️⃣ Karlovy Vary – A famous spa town with colorful architecture 4️⃣ Kutná Hora – Home to the unique Sedlec Ossuary (Bone Church) 5️⃣ Bohemian Switzerland National Park – Incredible rock formations & landscapes 6️⃣ Telč – A picturesque town with pastel-colored Renaissance houses 7️⃣ Pilsen – The birthplace of the world-famous Pilsner beer 8️⃣ Moravian Karst – Stunning caves and natural rock formations 9️⃣ Olomouc – A historic city with baroque fountains & a UNESCO-listed column 🔟 Adršpach-Teplice Rocks – Unique rock formations and breathtaking trails

✈️ Plan your Czech adventure and experience its rich history, culture, and natural beauty!

🔔 Don’t forget to Like, Comment & Subscribe for more travel inspiration!

#CzechRepublic#Travel#Prague#VisitCzechRepublic#BucketList#FairyTaleDestinations#EuropeTravel#HiddenGems#Tourism#Adventure#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exploring Europe’s Hidden Gems: Offbeat Tour Packages for Adventurers

Europe is often associated with iconic landmarks like the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Colosseum in Rome, and Big Ben in London. However, the continent is also home to countless hidden gems waiting to be explored. For adventurers seeking something different, Europe tour packages focused on offbeat destinations offer the perfect opportunity to discover the road less traveled. These unique spots promise authentic experiences, breathtaking scenery, and cultural richness that rival any mainstream destination.

Why Choose Offbeat Destinations in Europe?

Hidden gems in Europe provide a quieter, more intimate travel experience. Away from the bustling crowds of popular tourist spots, these destinations allow you to connect deeply with local culture and nature. Opting for offbeat Europe tour packages also often means more budget-friendly options and a chance to support lesser-known communities.

Top Hidden Gems to Include in Your Europe Tour Packages

1. Hallstatt, Austria

Nestled between the Salzkammergut Mountains and a serene lake, Hallstatt is a picture-perfect village. Known for its salt mines and charming streets, it’s a peaceful escape for travelers seeking tranquility. Many Europe tour packages offer guided tours of Hallstatt’s salt caves and boat rides on the lake.

2. Kotor, Montenegro

This UNESCO World Heritage site features stunning fjord-like landscapes and well-preserved medieval architecture. Climbing the Kotor Fortress offers panoramic views, while the old town’s winding streets are perfect for exploration.

3. Gjirokastër, Albania

Gjirokastër is a hillside town filled with Ottoman-era architecture. Known as the “City of Stone,” it offers a glimpse into Albania’s history. Visit the Gjirokastër Castle for breathtaking views and insight into the area’s past.

4. Faroe Islands, Denmark

For nature lovers, the Faroe Islands are an untouched paradise. With dramatic cliffs, cascading waterfalls, and puffin colonies, this remote destination is ideal for hiking and photography. Some Europe tour packages even include ferry trips between the islands.

5. Český Krumlov, Czech Republic

This fairy-tale town boasts cobblestone streets, a stunning castle, and vibrant Baroque architecture. It’s a smaller, less crowded alternative to Prague, perfect for a romantic or family getaway.

Activities for Adventurers in Offbeat Europe

1. Hiking in the Julian Alps, Slovenia

The Julian Alps offer pristine trails, alpine lakes, and rustic huts for a true wilderness experience. Lake Bohinj and Triglav National Park are must-visit spots.

2. Exploring the Caves of Aggtelek, Hungary

The Aggtelek Karst and Slovak Karst Cave Systems are UNESCO-listed wonders. Guided tours take you through intricate formations and underground rivers.

3. Stargazing in La Palma, Canary Islands

Dubbed the "Starlight Reserve," La Palma offers some of the clearest skies in the world. Astronomy enthusiasts will love the observatories and night sky tours.

4. Wine Tasting in Douro Valley, Portugal

Escape to the Douro Valley for vineyard tours and wine tastings. The terraced landscapes and traditional winemaking methods make this region truly special.

Tips for Booking Offbeat Europe Tour Packages

Research Thoroughly: Ensure the package includes lesser-known destinations you’re excited to explore.

Check Inclusions: Look for itineraries that cover local guides, meals, and unique experiences like cave tours or stargazing.

Travel During Shoulder Seasons: To avoid crowds and high prices, visit during spring or autumn.

Pack Smart: Include essentials like hiking boots, layered clothing, and a good camera to capture memories.

The Benefits of Choosing Hidden Gems

1. Authentic Cultural Experiences

Interacting with locals and experiencing traditional festivals or crafts in lesser-visited areas offers an unmatched cultural connection.

2. Fewer Crowds

Hidden gems provide a relaxed atmosphere, allowing you to fully immerse yourself without jostling for space.

3. Eco-Friendly Tourism

By visiting lesser-known areas, you’re contributing to sustainable tourism and spreading economic benefits to small communities.

Conclusion

Europe’s hidden gems offer a unique blend of adventure, culture, and natural beauty. Opting for offbeat Europe tour packages ensures that you’ll uncover unforgettable experiences far from the beaten path. From the serene Faroe Islands to the historic streets of Český Krumlov, these destinations promise memories that will last a lifetime. So, take the road less traveled and discover a side of Europe that few get to see.

FAQs

1. What makes offbeat destinations in Europe special? Hidden gems in Europe offer unique cultural and natural experiences, fewer crowds, and a more authentic connection to local life.

2. Are offbeat Europe tour packages budget-friendly? Yes, these packages often cost less than mainstream tours while offering excellent value through unique experiences.

3. What should I pack for offbeat destinations? Essentials include sturdy hiking boots, layered clothing, a travel guide, and a good camera.

4. Is it safe to travel to lesser-known places in Europe? Absolutely! Most destinations in Europe are safe, but it’s always wise to follow local travel advisories.

5. Can offbeat destinations cater to families? Yes, many hidden gems offer family-friendly activities, making them perfect for adventurers of all ages.

#tourism#travelblogger#tourist#europe#tourisim#travel photography#travel#traveling#europe tour 2025#travel blog

1 note

·

View note

Text

An unforgettable adventure in the Punkva Caves

Last week I finally had the opportunity to explore the famous Punkva Caves in the Moravian Karst. This trip had been on my bucket list for a long time, and I have to say: it was worth it!

The history of these fascinating caves goes back a long way. Parts of the caves were explored as early as the 17th century, but it wasn't until 1909 that the Czech speleologist Karel Absolon succeeded in penetrating deeper into the underground labyrinth. His discoveries led to the caves being opened to the public in 1910.

My adventure began with an exciting ride in the cable car. As we floated gently over the picturesque landscape of the Moravian Karst, I could hardly contain my anticipation of the subterranean experience to come. The view from the top was breathtaking and gave a foretaste of the natural wonders that awaited me.

Once inside the caves, I was overwhelmed by the beauty of the stalactites and stalagmites that have formed over thousands of years. Our guide explained that some of these formations grow up to 1cm per century - a fascinating thought of the time spans that nature has been at work here.

The highlight of the tour was undoubtedly the boat trip on the underground river Punkva. In the silence of the cave, interrupted only by the gentle lapping of the water, I felt like I was in another world. When we reached the famous Macocha Abyss, I was speechless in the face of the enormous 138 metre deep gorge.

The Punkva Caves are not only a natural wonder, but also a testament to human exploration and perseverance. The thought of the early explorers who explored this subterranean world with simple means is remarkable.

After the excursion, I was amazed at what Mother Nature is capable of and grateful for this unique experience. The Punkva Caves are definitely worth a visit - a fascinating journey into the depths of the earth and the history of human exploration.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Koněprusy Caves (Czech: Koněpruské jeskyně), also Zlatý kůň (Golden Horse), is a cave system in the heart of the limestone region known as Bohemian Karst in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic

0 notes

Text

AuthorVillari, Luigi, 1876-1959IllustratorHulton, WilliamLoC No.04031171 TitleThe Republic of Ragusa: An Episode of the Turkish ConquestCreditsProduced by Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net(This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)LanguageEnglishLoC ClassDB: History: General and Eastern Hemisphere: Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, SlovakiaSubjectDubrovnik (Croatia) -- HistoryCategoryTextEBook-No.55332Release DateAug 10, 2017Copyright StatusPublic domain in the USA.

THE eastern shore of the Adriatic from the Quarnero to the Bocche di Cattaro is a series of deep inlets and bays, with rocky mountains rising up behind, while countless islands, forming a veritable archipelago, follow the coastline. The country is for the most part bare and stony. The cypress, the olive, the vine grow on it, but never in great quantities. Patches of juniper and other bushes are often the only relief to the long stretches of sterile coast. Here and there more favoured spots appear. At Spalato and in the Canale dei Sette Castelli, on the island of Curzola, in the environs of Ragusa, the vegetation is luxuriant, almost tropical. But Dalmatia is always a narrow strip, and as one pro2ceeds southwards it becomes ever narrower, the mountain ranges at various points coming right down to the water’s edge. The land is subject to intense heat in summer, and is free from great cold, even in the middle of winter. But it suffers from fierce winds, from the bora, which, whirling down from the treeless wastes of the Karst mountains in the north-east, sweeps along the coastline with terrific force. Another curse from which it suffers is the frequency and severity of the earthquakes, which from time to time have wrought fearful havoc among the Dalmatian towns.

But in spite of these disadvantages, along this shore a Latin civilisation arose and flourished which, if inferior to that of Italy, nevertheless played an important and valuable part in European development. Many wars were fought for the possession of Dalmatia. Roman, Byzantine Greek, Norman, Venetian, Hungarian, Slave, and Austrian struggled for it, and each left his impress on its civilisation, although the influence of two among these peoples far surpassed that of all the others—the Roman and the Venetian.

Dalmatia has at all times been essentially a borderland. Geographically it belongs to the eastern peninsula of the Mediterranean, to the Balkan lands. But this narrow strip of coast, as Professor Freeman said,1 “has not a little the air of a thread, a finger, a branch cast forth from the western peninsula.” In its history its character as a march land is still more noticeable, and this feature has always been manifested in a series of civilised communities in the towns, with a hinterland of3 barbarous or semi-civilised races. Here were the farthest Greek settlements in the Adriatic, settlements placed in the midst of a native uncivilised Illyrian population. Here the Romans came and conquered, but did not wholly absorb, the native races. Then the land was disputed between the Eastern and the Western Empires, later between Christianity and Paganism, later still between the Eastern and Western Churches. The Slavonic invasion, while almost obliterating the native Illyrian race, could not sweep away the Roman-Greek civilisation of the coast. Again Dalmatia became the debating ground between Venetian and Hungarian, the former triumphing in the end. When Christianity found itself menaced by the Muhamedan invasion, Dalmatia was the borderland between the two faiths. A hundred years ago it was involved in one phase of the great struggle between England and France. To-day, under the rule of a Power which may be said to be all borderland, it is the scene of another nationalist conflict between two races. As before we still have a civilised fringe, a series of towns, with a vast hinterland inhabited by Slaves, by a race less civilised, yet wishing to become civilised on lines different from those of the Latin race. It is still the borderland between the Catholic and the Orthodox religions, and also between the two branches of the South-Slavonic people—the Croatians and the Serbs.

0 notes

Photo

#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#small pasque flower#flowers#nature#pulsatilla pratensis#czech karst#koniklec luční#český kras

94 notes

·

View notes

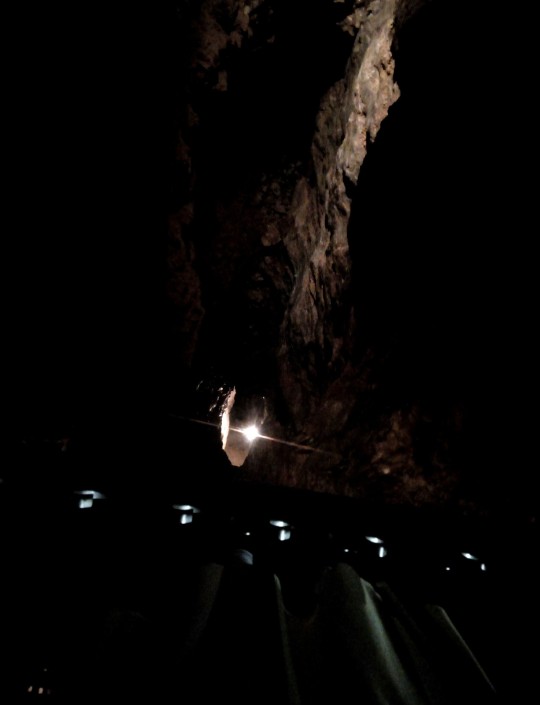

Photo

“ The Witch of Katerinska Cave” by Mark Gubics @500px

1 note

·

View note

Video

tumblr

butnomatter.theroadislife

Plitvice Lakes, Croatia 🗾

#plitvice#enchanted lake#national park#czech republic#nature#waterfall#travel#karst#limestone#geology#vivid#instagram#theh earth story

823 notes

·

View notes

Text

My dad and I had both free monday, so we went on a trip to the Moravian Karst - to the Sloup-Šošůvka & Catherine (Kateřinská) caves:

And... I couldn't resist to buy ANOTHER pair of bat socks 😄

#letter orc's clan#my photos#moravian karst#sloup-šošůvka caves#kateřinská cave#the czech republic#caves#nature

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

15.09.2018, Blansko, Czechia.

#blansko#czechia#czech republic#Česká republika#Kateřinska jeskyně#Moravský kras#moravian karst#karst#cave#south moravia#travel#nature#photography#caterina cave

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

last rays

Zanfoar

Karst formations - Czech Republic

#last rays#sun rays#sunrays#sunshine#sun ray#forest trees#zanfoar#czech#czechia#Misty Morning#misty sun#Misty#natural light#nature#landscapes

43 notes

·

View notes