#cyprus sinns

Text

Nah I think tumblr should see this

#chronmune#lime sinns#cyprus sinns#oc art#not my ocs but y'know#this happened bc dot said cyprus is a babygirl#bbg#my art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

next steps re: lizzy biting the big one

starting with india, kenya, pakistan, grenada, or cyprus, countries begin to leave the commonwealth

liz truss tries to do some diplomacy about it and it doesn’t work

charles the third of his name or what the fuck ever tries to do some diplomacy about it, says something BREATHTAKINGLY RACIST and actively makes it worse. countries start leaving even faster.

australia peaces out

scotland announces a new independence vote before the end of the year

wales, not to be outdone, announces an independence vote before the end of the MONTH

canada peaces out

someone starts a conspiracy theory on tiktok that liz truss had the queen poisoned just after their official meeting

Ireland announces the affirmative results of the reunification vote it held while you motherfuckers were distracted via the Sinn Féin twitter. britain pulls a spain circa 2017 and tries to prevent it

king charles III dies of a heart attack from stress, smh guys he just wanted to live out the remainder of his life in peace while directly profiting from the imperial and colonial violence of his mother ancestors, he wasn’t expecting to actually have to WORK for it

king arthur returns, sword in hand, to reclaim his rightful place as king. the tories, desperate at this point for some kind of miracle, let him do it.

his first act as king is to demand the abolition of the british monarchy, because “strange women lying in ponds and distributing swords is no basis for a system of government”

someone calls a vote of no confidence in liz truss. she fails it (in large part due to the conspiracy theory), they hold an election

Christopher eccleston becomes the prime minister

#queen elizabeth II#king charles iii#king arthur#british politics#the commontwealth#anyway. just some food for thought#wales scotland ireland know we are all rooting for you#christopher eccleston

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

dispatch on the unrest in belfast

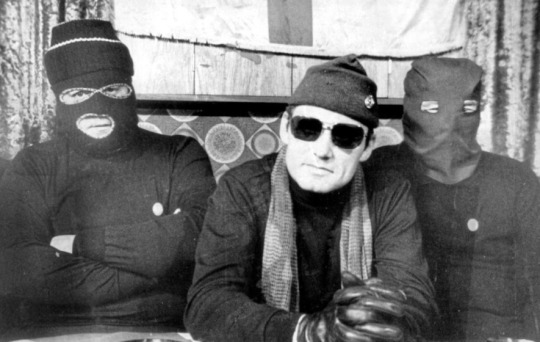

in the late 1950s a group of British Army soldiers from Northern Ireland became notorious for butchering civilians in Cyprus. they were defending the British occupation from the EOKA, led by (no, really) General Grivas, who wanted reunification with Greece. despite Grivas attempts to prevent it the war quickly became a sectarian conflict between Christian Greek Cypriots and Muslim Turkish Cypriots. it was an extremely bloody conflict fought with civilian lives. for the first time in war the pipe bomb replaced the heavy artillery.

when the British surrendered in 1960 those soldiers returned home and, in order to combat the Catholic civil rights movement, became involved in civilian loyalist organisations like the Loyal Orange Lodge until in 1966 when they formed the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). their innovation was to apply the experience in Cyprus to Northern Ireland to defend a partition which was not, at this stage, actually under attack. that year they carried out a string of random killings on the Catholic Falls Road. the civil rights movement developed into an armed struggle for national liberation, the British Army was deployed to combat it, and the UVF were transformed into anonymous soldiers for apartheid, armed by the South African regime, among others, and receiving clandestine support from the British.

pictured: Gusty Spence, first prince of loyalist terror, flanked by his retainers

when Gusty Spence, the leader of the UVF, was caught and imprisoned, he gradually lost control of the organisation. by the end of the 70s it had turned from a politically motivated death squad into an organized crime syndicate and was competing with several other paramilitary rackets, especially the UDA who still control the drug trade in Protestant areas. when Gusty Spence got out of prison he and several other former UVF brigadeers would join the Progressive Unionist Party, which combined loyalism with socialism. they were instrumental in negotiating the ceasefire known as the Good Friday Agreement in the 90s.

the sectarian killings died down but never disappeared. the far-right DUP, led by arch-reactionary Ian Paisley and maintaining secretive associations with both the Loyal Orange Lodge and the UVF (alongside Paisley’s several failed attempts to create his own paramilitary organization known as Third Force), became the dominant unionist party and the dominant party in Stormount, while Sinn Feinn, the political wing of the Provisional IRA, had become the leading republican party throughout the 1980s. apart from a few weak gestures they both agreed on a bunch of austerity cuts and fought tooth and nail against abortion and so on, reiterating the “carnival of reaction north and south” in microcosm.

throughout the 2000s a lot changed. the sectarian Royal Ulster Constabulary was disbanded and replaced with the dysfunctional Police Service Northern Ireland. the loyalist paramilitaries generally decomissioned as requested. it seemed like things were changing. by 2011 the final report of the Independent Monitoring Comission was cautiously optimisitc, writing that “In our first year [2004], each week there were on average four victims of paramilitary violence, some in sectarian incidents. In the last six-monthly period on which we reported the number was about a third of that and none were sectarian” (IMC, pg. 14). but already in 2003 Peter R. Neumann, a researcher on terrorism and partisan conflict, predicted that “the current peace process may not be the ending of the conflict but the suppression of it into the politics of threat and coercion” (Neumann, Britain’s Long War, pg. 1). fifty years after Marcuse was worried about ‘repressive desublimation’ in America, we were finally enjoying the good old ‘disciplinary society’ in Northern Ireland.

the loyalist paramilitaries went through a profound involution, becoming ethnoreligious dictatorships with exclusive police authority over the communities they claim to represent, battling among each other for control over housing estates. they possessed exclusive control over the black market, forced all businesses to pay them protection, and controlled most commercial services (taxi cabs, window cleaners, and so on). they exiled troublemakers, wounded lawbreakers, and murdered their opponents. your neighbours are taken away in the middle of the night and no one asks what happened. you wake up to breaking glass and gunshots, but no screams. then the paramilitaries appropriate the house of their victim and lease it out themselves. the IMC make an uncharacteristically wry remark that this is just “one amongst many ways in which paramilitaries continued to do what they had always done, namely doing violence to their own communities.” (IMC, pg. 14)

The Comission writes that “when we started we observed a scene from which terrorism against the organs of the state had largely disappeared,” yet “as we close we see classic signs of insurgent terrorism” (IMC, pg. 15). the very next year, in December 2012, the UVF and UDA were able to mobilize a huge crowd of Protestants in a campaign of civil disobedience over the removal of the Union Jack from City Hall. this was the first time since the partition that loyalism had taken on the appearance of a genuinely popular movement, looking more like Catholic civil rights marchers of the 60s than Black & Tans. the transformation of loyalism into a form of militant political activism with its own demo circuit was one of a few significant changes of the last decade (we won’t have time for the others in this post). throughout the 2010s they carried out agitprop, pamphleteering, posting up placards and organizing protests against the traitors, touts and frauds at Stormount, even training their own professional activists like Jamie Bryson, all soliciting Protestants to help them protect their cultural identity, heritage and the usual hogwash.

the sedition intensified when, on the 11th of July, 2018, in order to protest ... something, all over Co. Down and Belfast masked and armed volunteers hijacked busses and cars and burned them out, blockaded the roads with burning tires, and hid pipe bombs in the wreckage (BBC). but there was no pretension that this was an act of popular will. it all happened before 5am, and the UVF immediately contacted the police and the press to claim responsibility.

now on the seventh day of violent unrest in Belfast we find this tendency reaching its fullest expression. the events are widely reported on as ‘riots’, but the attacks are identical to the UVF sedition in 2018 and, anyway, require a level of organization which only a paramilitary possess. the difference is that in this instance, like in the Flag protests of 2012-2013, the paramilitaries were able to mobilize ordinary Protestants. but how mobilized are they?

“When the hostage espouses the cause of the terrorist ... then another justice is active than the justice of the law, other scales than the scales of justice.” (Baudrillard, Cool Memories V 2000-2004)

whenever an ordinary person is beaten, shot, exiled or killed by the UVF, our neighbours do not, as we do, hide under their beds and pray. instead, very often, they celebrate. they regard acts of terror as occasions for saturnalia; they come out into the street and cheer, they open buckfast or bacardi, they call their friends to let them know, and in their voices one hears earnest excitement. after the involution of terror we can no longer really blame this on the red mist of bigotry. it makes no difference to armoured Protestants whether the victim is enemy or friend. the order of the spectacle wins out over the mode of terror.

if one looks closely at the events in belfast, common people are present but they are spectators, not participants. elderly women and babies in prams along with their families line up along the sidewalk to watch and cheer while the professionals blow things up. if this is a riot, it’s a strange kind of riot. in some sense The Belfast Riots Did Not Take Place. the pipe bomb returns to Belfast as a simulation of the pipe bomb of the Troubles, already a simulation of the pipe bomb of the Cyprus Emergency, a retaliation to an attack that hasn’t happened yet. but pay close attention to the redirection that has taken place; the bomb is thrown, not into the window of a Republican bar, like the petrol bomb that killed Matilda Gould, but into a line of riot police, like the pipe bomb at the Haymarket riot.

so, what’s next?

some commentary has been made about the fact that the military has been deployed to settle the unrest. this seems like something new, perhaps the first time since the Good Friday Agreement. but, in fact, the military were already deployed in Northern Ireland from the beginning of COVID-19 to support the health services and supply logistics (BBC). it’s significant that they were not called in for the 2012-2013 Flag protests or the ‘Day of Disorder’ in 2018. the state of exception brought about by the pandemic has possibly adjusted the scales. furthermore, the military, previously arming and collaborating with the UVF, are now being deployed specifically to prevent them.

the IMC reported that very few of the killings, by 2011, were sectarian. the Flag protests were sectarian only indirectly, affirming the Protestant ‘siege mentality’, but the enemy was Stormont and not the specter of armed republican revolution. the 2018 disorder had no sectarian content at all. conversely, the incident which incited this week’s Belfast Riots was much more explicitly sectarian. it’s a lot of horseshit: they (prominently, the DUP) wanted Michelle O’Neill, Deputy First Minister and member of Sinn Feinn, arrested for violating COVID restrictions to go to a funeral. the riots began the day the PPS decided not to prosecute. the contention is that COVID restrictions are being unequally enforced between Protestants and Catholics. a paranoid inversion of the real inequality was typically a justifciation for sectarian violence during the Troubles. in one of the most violent moments of the riot the Lanark Way peace wall, separating the Falls and the Shankill, was set on fire and breached, Protestant rioters storming the Catholic street and attacking its residents (the Guardian).

is this the last gasp of an old order of sectarian violence, quickly being replaced by a new kind of reactionary populism? or are these the early ripples of a new, increasingly violent sectarian resurgence? will the tensions between the UVF and the British Army continue to escalate, or will the civil war transform into an ethnic conflict, like in Cyprus? we cannot anticipate the outcome. but the last 6 days seem like significant ones to me. we should remain sensitive to the changes that are coming.

133 notes

·

View notes

Link

Cyprus Avenue

Last November, Gerry Adams announced that he would be stepping down at leader of Sinn Féin - and when you combine this with the passing of Martin McGuinness, it leaves the party at a crossroads. Doesn’t mean that Eric still wouldn’t be peeved to find him inhabiting the body of his grandchild, though...

0 notes

Text

8-1 | Table of Contents | DOI 10.17742/IMAGE.GDR.8-1.2 | HetzerPDF Coming Soon!

[column size=one_half position=first ]Abstract | The visual essay is based on research carried out between 2010 and 2015 under the title “Bodies of Crisis—Remembering the German Wende.” The project mainly consisted of oral-history research and a series of performance events presented in the UK and Germany. In 27 interviews, women from East Germany recollected their embodied quotidian experience amidst the political transition from a socialist to a capitalist state in 1989 and thereafter. Live performance opened up access points for a transcultural translation of this experience involving practitioners from diverse cultural and creative backgrounds. The performance work extended the culturally specific experience beyond the East German case by pointing toward global struggles for existence, acceptance, and emancipation.[/column]

[column size=one_half position=last ]Résumé | Cet essai visuel est le résultat du projet d’études «Bodies of Crisis – Remembering the German Wende» (Corps de la crise – Souvenir de la chute du Mur), réalisé à l’Université de Warwick de 2010 à 2015. Au moyen de 27 interviews, des femmes de l’Allemagne de l’Est se sont remémoré les expériences corporelles de leur vie quotidienne pendant l’époque troublée de 1989 et 1990. Ces interviews ont jeté la base d’un spectacle vivant impliquant des artistes variés, ouvrant un espace d’expression transculturel et artistique de ces expériences de temps de crise. La performance a montré l’universalité des expériences spécifiques de l’Allemagne de l’Est au regard des enjeux mondiaux que sont la survie, la reconnaissance et l’émancipation.[/column]

Maria Hetzer | Berlin

Negotiating Memories of Everyday Life during the Wende

#gallery-0-5 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-5 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

The visual essay is based on collaborative research a group of performance-based researchers conducted between 2010 and 2015 under the title “Bodies of Crisis—Remembering the German Wende.” The project mainly consisted of oral-history research and a series of performance events presented in the UK and Germany. In 27 interviews, women from East Germany recollected their embodied quotidian experience amidst the political transition from a socialist to a capitalist state in 1989 and thereafter. Live performance opened up access points for a transcultural translation of this experience involving practitioners from diverse cultural and creative backgrounds. The performance work extended the culturally specific experience beyond the East German case by pointing toward global struggles for existence, acceptance, and emancipation. The following sequence of images and clips invites readers to reflect on the embodied quotidian as a valuable approach to the study of the historical experience of 1989. Short commentaries consider how memories of somatic quotidian experience influence the experience of the body vis-à-vis wider social change.

Performance collaborators: Maiada Aboud, endurance art researcher (UK/Israel); Jessica Argyridou, video performance artist (Cyprus); David Bennett, dancer-researcher (UK); Michael Grass, heritage researcher and visual designer (UK/Germany); Linos Tzelos, musician (Greece). Further studio collaborators: Elia Zacharioudaki, actress (Greece); Osama Suleiman, media artist (Saudi Arabia/Jordan); Gordon Palagi, actor (USA).

Copyright lies with the project or photographers/agencies referenced in the image captions. Project photographers for Bodies of Crisis: Michael Grass (MG), Maria Rankin (MR), Ian O’Donoghue (IOD). My sincere thanks go to Seán Allan and Nicolas Whybrow, who supervised this research project, as well as Marc Silberman and two anonymous reviewers who made valuable comments on a draft of this essay. More information on the performance research can be found on the project’s website http://bodycrisis.org.

TRACK ONE: Historiography and the embodied quotidian

A reassessment of historical writing about 1989 reveals a general disregard for everyday and somatic practice. This is by no means a particular disposition of the discourse about the German Wende. Indeed, Henri Lefebvre reminds us that the body and more embodied practices tend to be forgotten in Western philosophical thinking and history (161). In cultural studies, critics have explored everyday practices as a resource for resisting modernity’s tedious routines and repressive demands (de Certeau xiv; Highmore 3). Here, the everyday encapsulates a limited set of practices by excluding a wide range of the sensate, i.e., issues of the body such as nutritional habits and hygiene. (For nutritional habits and German-German cultural history, see Weinreb in this issue.) One of many aspects nurturing this disregard of the somatic quotidian in Wende history is the relatively limited amount of available visual documentation depicting daily life before the advent of the digital age. In our studio work, we explored the ephemerality of everyday practice and created potential historical documents of the everyday of 1989. The image on the right is based on eyewitness accounts relating the changing taste of apples (“appearing shiny and delicious, but not tasting like an apple at all”) and other daily products.

Tasting apples. ©Bodycrisis / MG (IMAGE 1):

Twentieth-century German historiography has given the everyday prominence as a space of performing Eigen-Sinn in capturing individual agency vis-à-vis wider sociopolitical demands and state control (Lüdtke 13). In this context, the everyday functioned as a gatekeeper for the reassessment of GDR reality in light of the still dominant totalitarianism approach in historiography (Lindenberger 1). (On the need for a new approach to researching the everyday of the GDR, see Rubin and Ebbrecht-Hartmann in this issue.) In the context of writing and remembering 1989-90, however, the everyday has remained out of focus, as has the individual agent of change. Accordingly, historians have largely analyzed East Germans as a political mass (Grix 3). The image on the right shows one of the most significant demonstrations of East Germans for political reforms, taking place on Berlin Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989. This image belongs to the canon of documents framing the reality of the Wende.

November 4, 1989, Berlin, Alexanderplatz © Andreas Kämper, Robert Havemann Gesellschaft (IMAGE 2):

In some cases, historians have turned to examine the everyday of prominent agents for political change, for example, Bärbel Bohley as a leading representative of the GDR civil rights movement (Olivo ix). In short, we know little about how ordinary citizens organized and accomplished the everyday of 1989-90 when confronted with substantial socioeconomic and political change, nor do we know how it is remembered today. The period of the political Wende, 1989-90, disintegrates when employing an everyday approach. Many envision 1989 as the last year of the GDR and thus subsume its everyday under a more generally defined GDR normality that finally came to an end in November 1989. Correspondingly, East Germans woke up to the everyday of the now unified Berlin Republic in October 1990. Accounts following this narrative declared the temporary end of everyday life (Moran 216).

Round Table talks, East Berlin, 1989 © dpa / BAKS (IMAGE 3):

Frequently researchers approach the everyday of 1989-90 as a transitional, extraordinary, and somewhat anarchic period in which many East Germans made rules on the go and experimented in all areas of life (Links et al. 1; Holm and Kuhn 644). Hence, these accounts tend to document experimental practices and thriving subcultural communities, e.g., squatting and alternative living experiments, techno culture, and political projects. (On squatters and techno culture, see Smith, and on subcultural artists, see Eisman in this issue.) In summary, when we do find pictures of the everyday in 1989-90, they depict a temporary, exceptional period of sociocultural practices that render obsolete the realities hitherto known as ordinary.

Kommune I, the most famous squat in Mainzer Straße, East Berlin 1990 © Umbruch Bildarchiv (IMAGE 4):

In the context of narratives that focus on 1989-90 as a period of state and sociocultural transition from an Eastern to a Western model, this exceptionality seems particularly obvious. Searching for traces of the everyday in this discourse, many examples establish GDR citizens as the historical Other. They feed German-German cultural stereotyping by concentrating on consumption, depicting extraordinary events such as shopping sprees to West Berlin and West Germany, targeting a demand for bananas, cheap electronics, second-hand cars, and other Western daily goods. This kind of focus still dominates the discussion about the nature of GDR citizens’ needs and wishes for the future.

Example of an East German supermarket (Kaufhalle) addressing the desires of East Germans in 1990 © dpa / MZ.web (IMAGE 5):

By contrast, the interviews I conducted for this research project emphasized the persistence of known quotidian practices. Interviewees maintained that mundane practices of the everyday remained the same, in line with Lefebvre’s analysis that in times of change the everyday is last to change (131). This continuity of practices sanctioned feelings of reliability in a suddenly insecure political environment. It also enabled political participation on a daily basis, for example, by providing reliable childcare to workers so they could convene and rally for political action during the transitions of 1989-90. As a result, interviewees remembered integrating political participation into their daily routines and regimes, rather than substituting known everyday practices with new ones or changing their approach to daily life altogether. This everyday stability enabled societal change through active engagement with a political situation that was perceived as highly precarious, potentially changing the everyday forever.

Young East German woman eating © Bodycrisis / private (IMAGE 6):

On the level of the somatic, our group of performers undertook research in a studio setting that drew attention to the importance of conceptualizing a vital, energetic, accelerated political body. As such, the interviewees framed the everyday as characterized by all sorts of seemingly ordinary practices, a heightened level of energy that further supported restlessness, and a resistance to sleep, thus pushing the limits of the everyday. In our analysis of the interviews this corresponded with remembered practices of hesitation and excessive media consumption, consequently postponing obligations or fulfilling them halfheartedly.

Yet how do we translate this ambivalence of an everyday on the edge, an everyday we have come to understand as precarious but equally stabilized by repeated embodied practice? The live, performing body can generate insight into these parameters by allowing for a provisional and temporally limited identification of the self in others through somatic empathy, situatedness, and avowal of difference. As a result of our performance work, we devised hybrid cultural performance nodes that capture and intersect with the somatic experience from other cultural conflicts and scenarios. These nodes not only reflect back on the analysis of the specific historical experience of 1989-90, but also deflect attention from the extraordinary and unique aspects of the historical situation to focus on common, transcultural parameters for the explication of the relationship between somatic experience, the everyday, and social change.

The following video showcases our aesthetic engagement with the interviews on the precariousness of living through 1989 and grasping embodied quotidian experiences of 1989.

The ambivalence of everyday practice in a state crisis. Scene from the performance, Apples © Bodycrisis / IOD (IMAGE 7). Please click on the image to start video sequence of live performance:

TRACK TWO: Beyond the East/West divide

Stereotyping was and still is one of the most pronounced features of German-German memory work of the Wende (see Weinreb on stereotypes of German-German obesity and Klocke on attitudes toward medical care). Discussions of what it means to be East or West German intensified with the advent of the German unification process. Since then, cultural and social stereotyping prolongs the systemic competition that was part and parcel of the Cold War. Stereotypes predominantly derived from and referred to everyday practice: the way Easterners walked and talked, carried and dressed themselves (see Eghigian 37). These tropes remain virulent today and have become the legacy of successive generations. For example, in 2010 the German Federal Court was called upon to decide on the ethnic identity of East Germans after a woman from the East accused a Western employer of ethnic discrimination when he handed back her job application with the negative comment “Minus: Ossi” (Ossi is a derogatory term for Easterner). However, the Court rejected this instance of prejudice. While the ruling can be read as a rejection of lived experience as such, the Federal Court was unable to identify it as an instance of cultural discrimination. On these grounds, goes the legal argument, East Germans would be constituted as an independent ethnic community. We might speculate about the intellectual and material consequences for a revaluation of the Wende process in light of a postcolonial theoretical paradigm.

An East German woman’s application to a Western employer marked down “Minus Ossi” © dpa / n24.de (IMAGE 8):

Interestingly, the women interviewed for the project did not focus on the way in which the all-encompassing rejection of work experience mirrored an overall rejection of the lived experience of GDR citizens that was evident in the Wende process. This rejection ranged from blue collar to academic work in the context of liquidating and converting institutions (Abwicklung), not to mention political bureaucracy. While a minority of women employees were made redundant as early as 1990, the symbolic rejection of quotidian practices that came with ridiculing and mocking their outward appearance and habits seemed to weigh much more at this particular point in their lives. It was within this context that the interviews conducted for the Bodies of Crisis project picked up on stereotyping in relation to how it informed everyday practice. Meta’s account was the most pronounced in identifying a strategy of creative everyday resistance. She remembered engaging in camouflage tactics: “I hated the stereotyping, I really did… I moved to Berlin during that time… I got myself a map of Berlin and pretended to be a tourist, dressing like a stranger.”

Plan for the “New Berlin,” 1997. Map of Berlin with demarcation of Wall © Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung Berlin (IMAGE 9):

Against this backdrop, East Berlin occupies a specific place in cultural memory and the practice of cultural stereotyping—where counterculture thrived in the 1980s GDR and where subcultures blossomed in the early 1990s, often nurtured by activists from West Berlin seeking to extend their urban playground in the East. (On West German activists in East Berlin, see Smith in this issue.) East Berlin evolved as a comfort zone of social experimentation, while the new federal states in the East faced the consequences of rapid reorganization in all areas of life: mass unemployment and widespread industrialization, the breakdown of social and cultural services and institutions, rapid demographic declines caused by East-West and urban migration, shrinking cities and deserted rural areas—the post-socialist landscapes of change.

Projecting histories onto bodies © Bodycrisis / IOD (IMAGE 10):

Following Meta’s account of her resistance to stereotyping, we traced the transformation of the Easterner into a tourist or stranger in our performance work. Among many attempts at identifying transcultural nodes of resemblance, an Arab-Israeli member of our group injected her own cultural associations of self-estrangement. In her analogy, Arab women in Israel are the Other of history, confronted with strong social and cultural stereotyping and consequently social discrimination in many aspects of daily life. This stereotyping is nurtured from a multitude of perspectives which preclude women’s accounts of resistance from fitting neatly into normative ethnic narratives of subjugated victims (Aboud 1). As the stereotypes go: in Arab eyes, women are either submissive or deviant daughters within a patriarchal system; in Israeli eyes, they are looked upon as politically and culturally conservative and unmodern, if not a potential threat to society and state control. Women seem constrained to perform within this frame of social stereotyping.

Translating the comfort zone of stereotyping © Bodycrisis / MR (IMAGE 11):

However, Arab-Israeli women can also assume such ascribed social roles and practices to their advantage in order to secure individual agency and room to maneuver in the everyday. Cultural camouflage also plays an important role here. For example, mimicking an Arab girl who does not understand Hebrew may provide protection in challenging public situations. In situations such as these, women utilize the stereotype to reclaim individual agency. Metaphorically speaking, they stretch the veil and turn it back into a piece of fabric they can mold into multiple shapes. The ambivalence of this twofold approach to cultural stereotyping can be usefully applied to the everyday of 1989-90.

Tentatively exploring cultural practices for room to maneuver © Bodycrisis / MR (IMAGE 12):

As such, the continuity of everyday practices provided a comfort zone, helping to preserve a sense of self in the light of intense devaluation of the former life and everyday practices in dominant public discourses. Moreover, we might imagine this comfort zone as an oxygen tent that can conserve everyday practice and that counteracts the suffocating quality of capitalist consumerism and overall change. Prolonged everyday practices thus served as a source of social identification and belonging, but also as cultural capital to secure scarce financial resources. To give but one example, it limited potential excessive buying and experimentation, throwing out all household items in exchange for new Western goods (Bude et al. 31). Everyday practices also formed a cocoon against the bitter reality of social discrimination based on cultural stereotyping, for example, by fostering a disregard for public discourse on GDR politics of the body (e.g., disregard for makeup, mainstream naturism, and sex practices) or deliberately ignoring advertisements that promote specific ideals of beauty.

Lastly, Meta’s account reveals how reticence to assimilate culturally on the level of the everyday and particular practices could be used as a means for self-identification beyond the felt provincialism of German-German stereotyping. Here, everyday practices served as a buffer zone, confronting and undermining expectations and stereotypes of what East Germans are and how they prefer to identify themselves.

Scene from the performance, The map © Bodycrisis / IOD (IMAGE 13) Please click on the image to start video sequence of live performance:

TRACK THREE: Exploring socialist politics of the body

Jahrhundertschritt

Gleichschritt und eigener Weg, Hitlergruß und Proletarierfaust,

Militarismus und Widerstand, Diktatur und Freiheit

– ein Rückblick auf das 20. Jahrhundert. (Mattheuer 1)

[Step of a century

Marching and individual pace, Hitler sign and proletarian fist,

Militarism and opposition, dictatorship and freedom –

Looking back on the twentieth century.]

What is left of the liberated woman in German discourses of 1989 relating to embodied quotidian experience? Discussions of socialist politics of the body regarding the everyday remain infrequent and often limited to exploring nudist practices as an exotic but widespread phenomenon in the GDR. Nudist practices often signal a point of reference for cultural differences between East and West and symbolize generally a different image of women in GDR society—the liberated woman.

Jahrhundertschritt by Wolfgang Mattheuer © Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (IMAGE 14):

Naturism may have emerged as a powerful trope of cultural distinction because it was such a pronounced and visible feature of GDR beach culture. As West Germans began to frequent East German beaches and declared nude bathing inappropriate, many East Germans felt annoyed and deprived of a habitual, quotidian practice. Gradually the Eastern nude beaches turned into “textile zones” (i.e., swim suits required) for Western tourists where naturism was prohibited by local authorities. Naturism is also strongly connected to the image of the liberated woman, a trope that was cultivated as a reality in the GDR by authorities and citizens alike and that found its symbolic expression in visualizations of the confident female nude: natural, that is, nonchalantly unshaven and naked. Thus, we can regard the image of the nude bather as a seemingly strong document of performing mainstream East German politics of the body.

East German bathing © Eulenspiegel Verlag (IMAGE 15):

However, while some maintain that naturism is a movement grounded in turn-of-the-century German culture, others show its evolution among independent movements across the globe (BritNat 1). Be that as it may, by the 1940s it had become a cross-cultural phenomenon. In images of an early conference of British naturists, we can discern female presenters and participants.

Participants of the 1941 conference of British Naturists’ Associations © IMAGO / Welt.de (IMAGE 16):

The history of naturism in the GDR is complex, and by no means were the petty-bourgeois fathers of the new socialist German state initially inclined to accept it as a mainstream cultural practice (McLellan 143). Only gradually did it become a mass movement that gained political momentum and emerged as a defining symbolic feature of a society that strove for the liberation of people from all sorts of oppression around the globe.

GDR stamp illustrating allegiance to a global fight against racism incorporating a drawing by John Heartfield © 123RF (IMAGE 17):

By the end of the socialist state, however, mainstream nudism first and foremost stood for the emancipated GDR woman, freed from the patriarchal politics of the gaze.

The fist as a symbol for global feminist struggle © history.org.uk (IMAGE 18):

Correspondingly, West German public discourse since the 1970s has seen a strong correlation between feminism and culturally specific politics of the body related to shaving, rather than a permissive attitude toward displays of nudity. This correlation led to a cultural stereotype that still identifies women as lesbians and feminists on grounds that they employ a more “natural” approach to daily body practices, i.e., no body shaving. The cliché says: feminists are hairy and stink (Eisman 628). Needless to say, we have strong evidence to the contrary, for example, images of a female team from West Germany in the 1972 Olympic Games display unshaven armpits. The life circumstances of Ingrid Meckler-Becker, one of the women portrayed in the photo, suggest a non-correlation between unshaven armpits and feminism: she was a conservative party member, married with children, and a schoolteacher. This cultural stereotype based on daily hygiene has gained new momentum to include East Germans in the post-Wall Berlin Republic. It exemplifies the union of fashion-based everyday practices and time-specific politics of the body at work.

The Olympic team of the FRG, June 1972 © ullstein bild / Tagesspiegel.de (IMAGE 19):

As part of the Bodies of Crisis project, we realized performance research on the relationship between cultural stereotypes rooted in public discourse that links everyday practice to political struggle. The creation of living statues targeted the visualization of the fashion-based, temporal, and cross-cultural elements of symbolism and aimed to account for their situatedness in localized political narratives and cultural discourses. The image shown here depicts the design of a performance response to the research question: how can we ascribe politics of the body their space in situated—that is, local and culturally specific—historiography without unnecessarily exoticizing it?

Scene from performance work, Fist © Bodycrisis / MG (IMAGE 20):

This important question also provided the background for most audience reactions to the project. We performed Bodies of Crisis for festival and academic audiences in London and Coventry (UK) as well as Bremen (Germany) with 30 to 80 people attending at any one time. In different organized feedback formats as well as informal conversations, spectators reacted to aspects of the performance they deemed well-suited (or not) to creating a transcultural understanding of historical experience. German audience members tended to refer to the relationship between memory work and nostalgia, a good reminder of enduring discursive parameters. Some were pleased by the emphasis on quotidian experience, even though it might not lend itself easily to political ideologization. Others were concerned that the performance offered no commentary framing the particular historical experience of GDR women in a socialist dictatorship, since this provided the main material. These viewers wanted to draw out the dangers of nurturing a possibly nostalgic view on the past, in contrast to UK spectators who could identify with images, quotidian behavior, and the depicted conflicts. The latter felt encouraged to become engaged in a transcultural conversation of crisis experience. Yet, since the performance work had been the collective creation of performers from multiple cultural backgrounds, it ceased “belonging” to a single cultural meta-narrative. As such, talking about nostalgia, for example, a main driver for memory discourses of German and anglophone publics, proved meaningless to Arab spectators, who were instead eager to discuss the necessity to re-perform the specific politics of the body on stage, displaying unshaven female nudes.

Scene from performance work, Tub © Bodycrisis / MG (IMAGE 21):

Works Cited

Aboud, Maiada. Stigmata: Marks of Pain in Body Performance by Arab Female Artists. Ph.D. dissertation, Sheffield-Hallam University, 2016.

Bude, Heinz, Thomas Medicus, and Andreas Willisch. Überleben im Umbruch. Am Beispiel Wittenberge. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2012.

BritNat. bn.org.uk, accessed September 30, 2016.

de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. U of California P, 1984.

Eghigian, Greg. “Homo Munitus: The East German Observed.” Socialist Modern: East German Everyday Life and Culture, edited by Paul Betts and Kathy Pence. U of Michigan P, 2008, pp. 37-70.

Eisman, April A. “Review of Art of Two Germanys / Cold War Cultures.” German History, vol. 27, no. 4, 2009, pp. 628-30.

Grix, Jonathan. The Role of the Masses in the Collapse of the GDR. Macmillan, 2000.

Highmore, Ben, editor. Everyday Life. Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies. Routledge, 2012.

Holm, Andrej, and Armin Kuhn. “Squatting and Urban Renewal: The Interaction of Squatter Movements and Strategies of Urban Restructuring in Berlin.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 35, no. 3, 2011, pp. 644-58.

Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. Columbia UP, 2004.

Lefebvre, Henri. Critique of Everyday Life. Vol. 2. Verso, 1991.

Lindenberger, Thomas. “Eigen-Sinn, Domination and No Resistance.” Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, docupedia.de/zg/Eigensinn, accessed October 4, 2016.

Links, Christoph, Sybille Nitsche, and Antje Taffelt, editors. Das Wunderbare Jahr der Anarchie: Von der Kraft des zivilen Ungehorsams 1989/90. Ch. Links Verlag, 2004.

Lüdtke, Alf. The History of Everyday Life: Reconstructing Historical Experiences and Ways of Life. Princeton UP, 1995.

Mattheuer, Wolfgang. Text next to sculpture in Bonn, Haus der Geschichte. commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%22Der_Jahrhundertschritt%22_(Step_of_Century),_Wolfgang_Mattheuer,_1984 -_Bonn.jpg, accessed October 4, 2016.

McLellan, Josie. “Visual Dangers and Delights: Nude Photography in East Germany.” Past & Present, vol. 205, no. 1, 2009, pp. 143-74.

Moran, Joe. “November in Berlin: The End of the Everyday.” History Workshop Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, 2004, pp. 216-34.

Olivo, Christiane. Creating a Democratic Civil Society in Eastern Germany: The Case of the Citizen Movements and Alliance 90. Macmillan, 2001.

Clip and Image Notes

Image 1: “Tasting apples.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Michael Grass.

Image 2: “November 4, 1989, Berlin, Alexanderplatz.” Copyright by Andreas Kämper, Robert Havemann Gesellschaft, 1989. Available online: revolution89.de/fileadmin/_processed_/csm_O_3.9.1_02_org_8b629c5d5d.jpg

Image 3: “Round Table talks, East Berlin, 1989.” Copyright by dpa / BAKS. Available online:

baks.bund.de/de/aktuelles/20-jahre-runder-tisch-in-polen-und-deutschland-demokratie-und-freiheit-in-europa

Image 4: “Kommune I, the most famous squat in Mainzer Straße, East Berlin 1990.” Copyright by Umbruch Bildarchiv.

Image 5: “Example of an East German supermarket (Kaufhalle) addressing the desires of East Germans in 1990.” Copyright by dpa / MZ.web. Available online: mz-web.de/kultur/ddr-geschichte-streit-um-vergangenheit-entzweit-viele-menschen-3193808

Image 6: “Young East German woman eating.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, private.

Image 7: “The ambivalence of everyday practice in a state crisis. Scene from the performance, Apples.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Ian O’Donoghue, 2012.

Image 8: “An East German woman’s application to a Western employer marked down “Minus Ossi”.” Copyright by dpa / n24.de. Available online: http://www.stuttgarter-nachrichten.de/media.media.f7378dec-32a6-4b52-b51a-1f3cf99b354c.normalized.jpeg

Image 9: “Plan for the “New Berlin” 1997. Map of Berlin with demarcation of Wall.” Copyright Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung Berlin, 1997.

Image 10: “Projecting histories onto bodies.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Ian O’Donoghue, 2012.

Image 11: “Translating the comfort zone of stereotyping.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Maria Rankin, 2012.

Image 12: “Tentatively exploring cultural practices for room to maneuver.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Maria Rankin, 2012.

Image 13: “Scene from the performance, The map.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Ian O’Donoghue, 2012.

Image 14: “Jahrhundertschritt by Wolfgang Mattheuer.” Copyright Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Available online: zeithistorische-forschungen.de/sites/default/files/medien/static/mattheuer1.jpg

Image 15: “East German bathing.” Copyright by Eulenspiegel Verlag / Welt.de.

Image 16: “Participants of the 1941 conference of British Naturists’ Associations.” Copyright by IMAGO / Welt.de.

Image 17: “GDR stamp illustrating allegiance to a global fight against racism incorporating a drawing by John Heartfield.” Copyright by Nightflyer. Available online: de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Stamps_of_Germany_(DDR)_1971,_MiNr_1702.jpg

Image 18: “The fist as a symbol for global feminist struggle.” Copyright by history.org.uk. Available online: goo.gl/images/u9d1uK

Image 19: “The Olympic team of the FRG, June 1972.” Copyright by ullstein bild / Tagesspiegel.de. Available online: tagesspiegel.de/images/heprodimagesfotos85120130902_imago-jpg/8725044/4-format2.jpg

Image 20: “Scene from performance work, Fist.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Michael Grass, 2012.

Image 21: “Scene from performance work, Tub.” Copyright by Bodycrisis, Michael Grass, 2012.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 International License although certain works referenced herein may be separately licensed, or the author has exercised their right to fair dealing under the Canadian Copyright Act.

Negotiating Memories of Everyday Life during the German Wende 8-1 | Table of Contents | DOI 10.17742/IMAGE.GDR.8-1.2 | HetzerPDF Coming Soon! Abstract | The visual essay is based on research carried out between 2010 and 2015 under the title “Bodies of Crisis—Remembering the German…

0 notes

Text

January 9, 2017 - Monday

Armed conflicts and attacks

January 2017 Jerusalem vehicular attack

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu blames the Islamic State for the attack that killed four soldiers and injured 15 others in East Jerusalem. (CNN)

Sinai insurgency

An attack by several gunmen and a truck bomb on a police checkpoint in El-Arish leaves 13 dead and 15 wounded, including the attackers. (Al Jazeera)

A U.S. Navy destroyer fires three warning shots at four Iranian fast-attack vessels after they close in at a high speed near the Strait of Hormuz, according to U.S. defense officials. (Reuters)

Disasters and accidents

A California storm in the Calaveras Big Trees State Park fells the 1,000-year-old American tree, the Pioneer Cabin Tree. (BBC)

2016 Irkutsk mass methanol poisoning

The death toll from people who drank poisonous methanol in Irkutsk, Russia, rises to 76. (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty)

January 2017 European cold wave

Dozens of people die in eastern Europe and Italy in recent days as a result of a cold snap with cancelled flights, frozen rivers, and traffic accidents. (Independent Online SA)

Law and crime

Two Orange County police officers are killed in connection with an apprehension attempt of a murder suspect. (CNN), (Reuters)

Lawyers of former Chadian President Hissène Habré, who was convicted of crimes against humanity last May and sentenced to life in prison, appeal the verdict, claiming there were irregularities in the trial and question the credibility of some witnesses. (The Guardian)

Politics and elections

Death of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

The Iranian government declares three days of national mourning following the death of the former president and one of the key figures in the Islamic Republic. (The Daily Mail)

President Hassan Rouhani praises Rafsanjani as a great man of the Iranian Revolution. (BBC)

Cyprus dispute

Greek and Turkish local leaders of Cyprus resume talks to end the division of the island before a high level multilateral conference takes place in Geneva this week in the latest effort to reunify the island. (The Guardian)

The cabinet of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte investigates an email leak that allegedly indicates the involvement of the vice president Leni Robredo in attempts to overthrow Duterte. (ABS-CBN)

Renewable Heat Incentive scandal

Martin McGuinness of Sinn Féin resigns as the NI deputy first minister in protest of handling by the Democratic Unionist Party of a failed energy scheme that cost Northern Irish taxpayers £490 million. His decision will likely lead to a snap election. (BBC)

115th United States Congress

Talks between top Donald Trump advisers and Speaker Paul Ryan happen at the capital to discuss tax reform. (The Washington Post)

Sports

Clemson defeats Alabama 35–31 to win the 2017 College Football Playoff National Championship. (ESPN)

0 notes

Text

Oh shit he did one of the intro things :o

I still haven't made lime and cyprus proper puppet designs yet rip </3, but dot mentioned cyprus having a midlife crisis, do now there's this

#I do think it's a little funny that lime ends up with the schrödinger's mouth but 🤷#chron dhmis au#pass 2#lime sinns#cyprus sinns#c!j!harvey#dhmis au#I started figuring out the rest of the intros too but I didn't finish that#my art

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Cyprus Avenue

“Gerry Adams has disguised himself as a new-born baby and successfully infiltrated my family home,” says Eric Miller in Cyprus Avenue - but who is Gerry Adams? This BBC profile should tell you just about all you need to know.

0 notes