#cw: executions

Text

kinda vampy

#art#digital art#my art 🦷#mcr#gerard way#my chemical romance#digital painting#vampire#cw blood#i feel like theres a looooot of texture going on in this but. maybe its tasteful??#either way im really happy with this piece :)#the lighting probably wasnt executed the best but idc lol#its been a while since ive done a piece WITH a background#so im giving myself some slack#kinda wish i have enough patience to figure out how to make his face look like its burning but ohhhhwellll#thats for another time

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

mdni. cw: hybrids. takes place a little before this drabble.

it’s not his fault you smell so good—that’s what your tiger hybrid tells himself, anyway.

yuuji does what he can while you’re at work: he cleans the apartment, exercises, and bathes (though he struggles to reach the base of his tail). he even makes food for you—what little he can, anyway, given the sad state of your kitchen. the rest of the day is his own, and is usually spent daydreaming about you.

that’s why he’s frantically rutting against the pillow on your bed. he knows it’s wrong, knows you would flip out if you caught him humping your pillow as if his life depended on it. but his cock aches for you; every time you cross his mind, every time he thinks about your soft skin and warm smile and shimmering eyes, he leaks a mess in his shorts.

usually, yuuji buries a nose in your sheets to soak in your scent while he jerks himself off. but your pillowcase is smooth and cool to the touch, the insert deliciously plush. it makes him think of you, how he wants to mount you—to put his full weight on your back and feel the friction of your dewy flesh against his. to fill you up yet leave you craving more.

but he can’t have you. so he fucks your pillow the way he yearns to fuck you. he can smell you everywhere; your scent embraces him, makes him feel like you’re there as he shuts his honey deep eyes and pants raggedly. and when he climaxes, he does it with the sweetest cry, one that would surely have you stroking his rosy ears.

yuuji whines as he floats back to reality, rolling onto his back. he’s still hard and thobbing, though he doesn’t want to deal with it, and your pillow is covered in his creamy spend. he makes a mental note to wash your bedding before you come home (he’ll frame it as a surprise). but for now, he curls up and drifts off to thoughts of you.

#sorry i had a vision. idk if it’s executed well but at least u can see it now#tw hybrids#cw hybrids#yuuji x reader#yuuji <3

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Curtwen Week Day 4: Haunted

#fuck yall I really wasn’t sure about this last night but looking at it now I think it’s grown on me#I tried going for a 1960s comic book look#because I really like the vibes of old comics#they’re very cool#honestly this came out very different from what I had planned originally#but then I had this idea and ran with it#also I made the executive decision of doing long hair Curt because A) It’s my drawing and I can do what I want and B) I love the idea that#curt had the long hair like in SAD post fall#whoever originally had that idea is a genius- I wish I could remember who it was#but yeah I love doing stylized stuff like this#I don’t do it as often as I want to#I have another saf idea similar to this that I’ve had on the back burner that I might do soon ish#i suppose we’ll see#I’m not making any promises#but yeah this one is a bit different from the drawings for the other three days#I got a bit of reprieve from all the rendering I’ve been doing#fun fact: palm trees are technically a type of grass#because it doesn’t have bark and it doesn’t have rings to tell how old it is#curtwen week#Curtwen week 2024#Curtwen#spies are forever#tin can bros#tin can brothers#agent Curt mega#curt mega#owen carvour#Joey richter#my art#cw guns

947 notes

·

View notes

Text

don’t worry y’all marinette was just showing her her new nails!! 💅

#carpetbug art#miraculous#miraculous ladybug#ml#miraculous fanart#cw suggestive#aged up kagami#kagami#kagami tsurugi#marigami#kagaminette#<- implied teehee#this idea has been rotting in my head for a while so decided to tackle art block by drawing it#idk how well i managed to execute it but whateverrrrrr#anyways. girl sex 🫶

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lonely Mountains (2023)

Original Dungeon Meshi drawing by sweepswoop_ on Twitter

#moomins#moominvalley#art#moomins snufkin#snufkin moomin#moomin snufkin#snufkin#moomintroll#I'm not gonna M/S tag this sjgkkskhkdg#moominvalley 2019#moomin meme#the episode still really annoys me in terms of premise and execution. just. MT honey what are you DOING#Why are you violating your bestie's one (1) boundary??? After 2 and a half seasons of character development???#if it happened earlier in the show I wouldn't be as bothered BUT IT DIDN'T AND IT QUESTIONS WHAT THE POINT OF THE MP@C ARC IS#swearing cw

179 notes

·

View notes

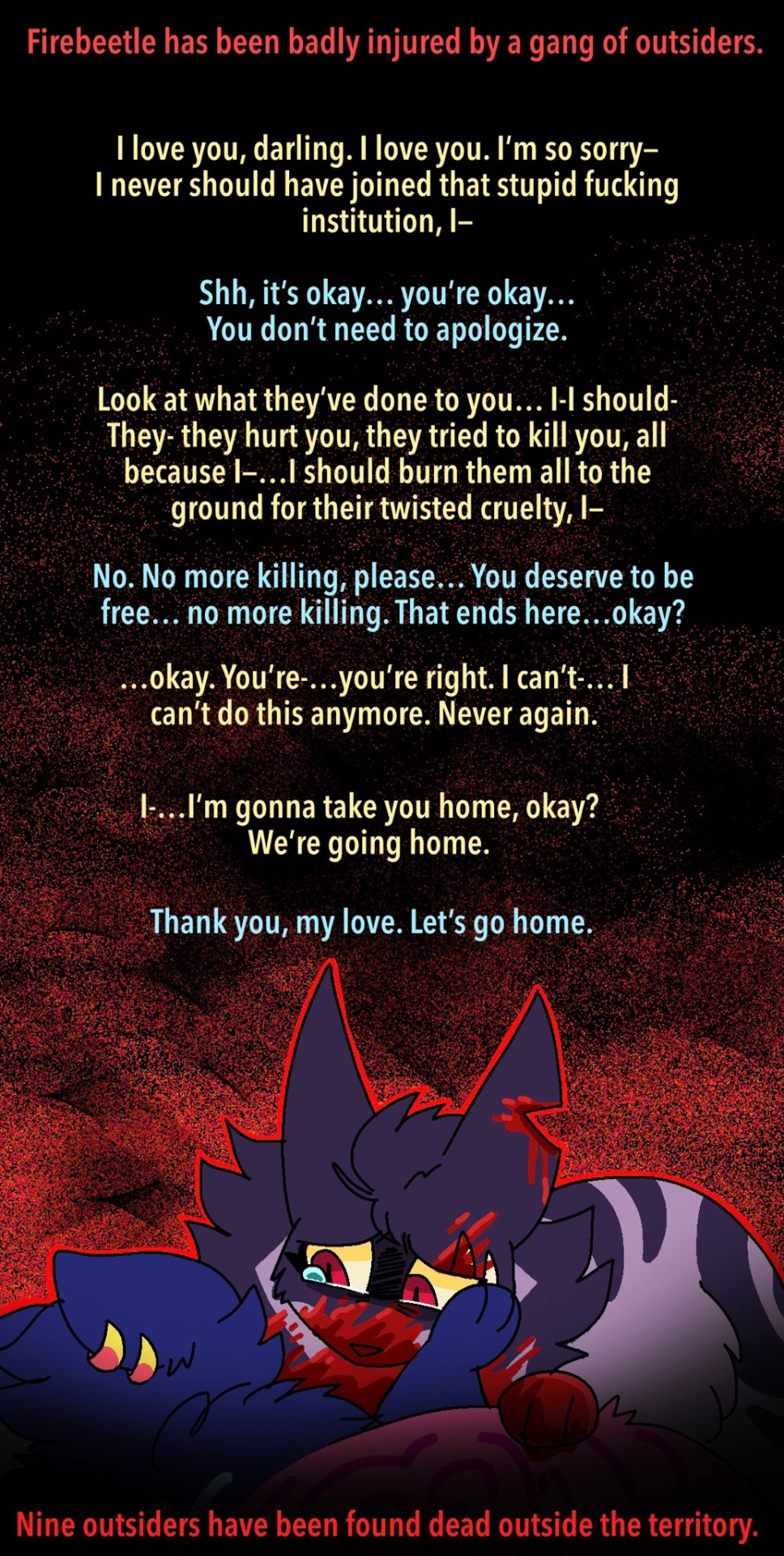

Text

#clangen#wc clangen#warriors#Warrior cats#wc#artists on tumblr#art#my art#aphidmoons#this was originally going to be a different big ass like 3 huge page update full of gore#but making this and the next few updates has been an executive function HELL and I HATED it#so I scrapped it all and I’m doing something new for this update instead#sorry for all the gore fans lmao#tw blood#blood warning#cw blood

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Do it, Gale.”

“Until we wake, my love.”

wip. I wish this ending had a different cinematic than when he does it alone, so here’s my vision of it

#gale dekarios#bg3 gale#gale of waterdeep#baldur's gate 3#bg3#my art#wip#gale x tav#bg3 spoilers#major character death#cw death#sketch#digital art#gale x male tav#gale x durge#cw blood#sorry that I’ve not posted any finished drawing recently#executive dysfunction really is a beast#bg3 fanart#galemance

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

“the dessert you don’t have to feel bad abt!” “guilt-free snacking!” “all the flavor none of the regret!” skill issue

#personally I am trying to free myself from the shackles of shame and help others do the same#but keep being a miserable marketing executive I guess#I love eating!! fuck u forever!!!!!#body neutrality#diet culture#body postivity#fuck diet culture#intuitive eating#cw food shame#tw food#tw food shame#bbge.text

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

Examples of music/media-based time measurement:

How long it takes for a song to finish playing ("It took me 2 songs to do this)

How long it takes for a TV show episode to finish ("It took me 3 episodes to do this")

Examples of food/drink-based time measurement:

The time it takes to finish a drink ("I'll stop when my water bottle's empty", "It took me two glasses of water to finish this")

The time it takes for a stick of gum to lose its flavor

The time it takes to eat something ("I want to finish this task before I finish my snack")

Examples of emotional/body-related things-based time measurement:

The time it takes for pain to develop (from poor posture, stiffness, and/or disability) ("I'll take a break when my foot gets sore")

The time it takes to feel bored, antsy, or under/overstimulated ("I finished a task before I bored of it")

#I hope I'm not the only one who does this stuff?#plum rambles#poll#adhd#amism#actuallyadhd#time blindness#executive dysfunction#neurodiversity#neurodivergent#neurodivergence#disability#disabled#disabled pride#mental disability#food#cw food#tw food

637 notes

·

View notes

Text

More old ones.

#resident evil#albert wesker#chris redfield#luis serra#luis serra navarro#luis sera#luis sera navarro#leon kennedy#leon scott kennedy#jake muller#claire redfield#jill valentine#ada wong#barry burton#rebecca chambers#sheva alomar#alex wesker#ashley graham#serrennedy#serennedy#cw execution mention#cw arson mention

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clothing fold study. Slightly suggestive under cut

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

ils m'ont tué pour la raison égoïste de m'aider

#OMG THIS TOOK SO LONG#IT WAS SOOOOOO WORTH IT THOUGH#also excuse if the french is wrong i used deepl... my beloved#trying to relearn french its so hard#ah i need to stop getting off topic and tag things#csr#continue stop rise#black batter csr#scotcharts#digital art#art#artists on tumblr#off game#off fangame#bugs tw#tw insects#cw bugs#tw bug#fav#favfavfav#i love this one alot actually#NO SPOILERS PLEASE IM NOT EVEN HALFWAY THROUGH BXE#bxe#bx execute

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

the so-called Terror: a dialogue

or: Why some concerns about the concept of revolution aren't worth your concern.

Frev happened 235 years ago. Rusrev happened 107 years ago. Chrev happened — do people still care when and how Chrev happened, or how Chrev was precisely inspired by the violent and popular aspects of Frev? No. Nein. Pas du tout. In all possibility, all that you hear is "Here is Why You Must Not Do Any More Revolutions".

That each of the Frev, Rusrev, and Chrev happened many years ago is a fact now misused and abused by those with no introspection in history or politics, only to show how "we are no longer living in the age of revolutions".

Against the Logic of the Guillotine. Because, as we all know, Louis Capet certainly survived by finding good talking points, and he loved facts and logic, and he facted so factually and he logiced so logically, that he won the rap battle against every member of the Third Estate and every petit bourgeois in each city and every peasant in each village and every enslaved person of Saint-Domingue, and therefore retained an absolute monarchy through the power of open reformist liberal discussion marketplace free-speech... (mumble jumble) ... both sides can have a point ideas opinions scientific human nature requires permissive modern enlightenment.

Enlightenment. It was philosophy that started the frev, and whether or not a person thinks highly of the frev, they cannot but admit: making sense of the frev is definitely very brain-consuming. This is where troll questions come in, and they are extremely brain-consuming if you, like me, sometimes get tempted to answer in good faith.

Most of the time, though, we on the left would brush away these troll questions. We'd respond... by not responding, because it's a waste of your time and energy to serve nuance, context, empathy, and primary sources, when, to the person who trolls you, if you know too much then you're an elitist, and if you know too little then you're a fake leftist, and if you know just the correct amount of things, then you're an elitist-fake-leftist. There's not even a sense of victory if you manage to fact-and-logic your way out.

But then, you log off, you do your twenty-five-hour-per-day paid shift, you eat, you shower, and you lie awake at night thinking: what if that person who comes off as a troll could unlearn what was certainly only a social condition? What if most trolls can become my leftist comrades?

Leftism. The title of a "leftist" is indeed a broad and vague one, and I totally understand that, for some of my fellow Marxists, it can be extremely annoying to debate a person who criticises capitalism as much as you do, but who, unlike you, does not take inspiration from any historical attempt at making a sustainable alternative. I mean, even Steve Bannon tries to brand himself as following Lenin, and he's already more specific in his wording than the liberal whose reason for calling themselves a "leftist" is that they would welcome trans people to become cops.

So what happens when the lines between Marxists and liberals constantly get blurred? And what if, in the night of the world, in the sombre stretch through each trembling horizon, all the way up into your own shadow, you hear what might as well be guns?

Well... To paraphrase Slavoj Žižek, himself paraphrasing someone whomst must not be mentioned: when I hear guns, I reach for my pop culture. I reach for my cultural osmosis, and I reach, and I reach, until I realise that the culture has not really osmosed upon me yet, because I never watched superhero films as a child, and cannot really name the so-called evil revolutionary villains in Gotham, and even without meaning to side-eye, I already am looking askew. The only problem, is how I, as someone who cannot have enough of Žižek's works, should be doing this looking-askew thing ...

Let's watch an instructional video to learn more.

(Alsip turns on the telly and shows the following.)

Trudy: Welcome to the Historic Hinterland, the show where we make the history that you've never heard of still feel as comfortable as home. I'm Trudy Mainstream. On this show, we don't ask for sources, we don't require history degrees, and we've only got one rule: we don't take "it's complicated" for an answer.

(Alice and Bob stare at each other from either side of Trudy, both waiting for Trudy to finish their introduction)

Trudy: Victor Hugo's Les Mis: can we finally de-politicise it? Jorjor Well's 90-84: why does it perfectly illustrate how the bourgeois intellectual is always the only sane man? Revolutionary Girl Utena: seriously, can she just calm down and be a pretty prince instead? Revolutions: can they be stopped at the right point in time? Today we’re talking about revolutions, and we’re leaving neither stone nor barrel-of-the-gun unturned.

(Both Alice and Bob already look tired.)

Trudy: My guests are Alice Kalandro, author of "From a Shakespearean Reading of Marx to a Marxist Reading of Shakespeare", and Bob Kinbote, beloved novelist, screenwriter, director, actor, whose 1992 debut "To Drown Next to You" about the tragic martyrdom of Olympe de Gouges, the feminist forerunner French revolutionary, has recently gotten a theatre adaptation. Bob, why is it so difficult to connect with all these self-proclaimed soon-to-be revolutionaries?

Bob: It's all about human nature, Trudy. That's the catch. If you start a revolution, and then it fails, you basically end up with a system much worse than the one you started with, all while ruining the reputation of your country among its neighbours. And human nature ensures that you shall go down as the most notorious of tyrants, monsters, beasts, and repressed queers.

Trudy: Ooh, I’d keep that last one off the list, really. I mean, I don’t know about her, but I’m not up for this language: I'm literally a they/them.

Alice: Well nice to meet you, Trudy, I'm Alice, and I’m also non-binary. You would have known that already, had you taken a glance at the About the Author paragraph on the front flap of my book.

Bob: And I don’t mean this as disparaging our queer audience in general. As an ally, I’m very aware of my optics, you see.

Trudy: But you don’t want any of our repressed queer viewers getting any ideas. Law and order, darling!

Bob: Not at all. Dare I say that the threat of totalitarianism is always one that worsens the lives of everyone, queer or trans or otherwise. And I don’t mean this as part of the community, but I know that wherever they oppress women, the queer people and the trans people would suffer simultaneously, at exactly the same rate and to exactly the same degree. The chevalier d’Éon, blessed be their soul, would have also perished on the scaffold had they decided to stay in France… Alice, you’ve written about Coriolanus and how he’s basically both gay and a rebel against his own mother, his own Rome. The archetypal restless youth. Would you say that Coriolanus ended up being a pathetic pawn of the totalitarian Volsci?

Alice: I’m not here to define things, and you’re not going to trick me into defining totalitarianism for you. But pray tell: How would a revolution fail, and how would a failed revolution worsen lives? Who gets disproportionately hit by this worsening you seem to be warning us about?

Bob: Trudy, you’ve got yourself a real sham rebel here. I mean, you've all heard about that lady whose great granddad used to own and sell all the eggs in China, right?

Alice: The source of her family’s case was a single thread that she tweeted half a century after it allegedly happened. Oh, we’re onto quite the great (!) example.

Bob: And she’s not the only example. Throughout the twentieth century, Hungarian mobs were raging through Cuban pagoda gardens, easily tearing apart like paper the precious Burkinabe musical boxes that used to entertain many an innocent young Haitian boyar.

Trudy: And why so much violence?

Alice: I must interrupt. What kind of violence are we talking about?

Bob: Long story short, it all started with the Guillotine, and the quick and painful executions thereby…

Alice: the probability that someone is an expert about the French Revolution is inversely correlated with the frequency at which they wax lyrical about how painful an execution by the guillotine was. And why am I, an amateur literary critic, and you, a historical novelist, the ones invited for this particular topic? Where are Jean-Clément Martin and Florence Gauthier and Peter McPhee and Clifford D Conner? Where is that tumblr user who’s been studying the so-called Terror of 1792-94, as well as the historiography thereof, for nearly two decades, and who can recount every love-language that the Duplays have shown to Robespierre?

Alice: (Now looking straight at you, the reader) Frankly, this is not my area of expertise. I won't tell you which particular British commonwealthmen influenced Jean-Paul Marat while he was a young physician practicing in England, and therefore imply that even the British were not and are not ontologically counterrevolutionary... because I am not a historian. All I can tell you, is why most of the conservatives and lower-l liberals are asking the wrong questions.

Trudy: Alice, this is a fun show about fun history for the average audience, we’ve got no time for this smug little elitism of yours.

Bob: Oh, but let her… I’m sorry, let Them carry on. Alice, you don’t want to talk about the Guillotine, so what type of violence are you referring to here? Struggle sessions?

Alice: I mean, are we talking about law-making violence or law-preserving violence, and are we touching upon the difference between mythic violence and divine violence at all?

Trudy: Alice, those are some jargons that will take eternity to explain. And our average audience don’t have eternity. I mean, are we categorising violences the way some very careful environmentalists would categorise their bins?

Alice: I can explain, and it's incredibly fun and unfortunately average, and I'm sure that after I explain, the average audience will keep my explanation safe in their hands, warm in their arms, and other types of comfortable in their various other bodily orifices.

(Alice makes sure that Trudy and Bob are not going to interrupt.)

Alice: When we hear about violence in the news, who is usually represented as the perpetrators of that violence? The answer is “mobs”. Protestors are framed as mobs with banners and war-cries. The armies of certain countries are framed as foreign mobs. Even workers on a strike — and for the majority of workers, being on a strike in the 2010s and early 2020s in the UK basically means taking the day off — are framed as mobs who want to cause a fuss instead of doing their job.

Bob: So that's what you call law-making violence? Come on, violence is violence, and all violence is always bad.

Alice: Bad for whom?

Bob: So your point is that some violence is good then?

Alice: My point is that, whenever violence makes the news, they are usually represented as done by mobs to the so-called normal and average person. What doesn't make the news, however, are the...

Bob: authors of children's books about talking owls and hats that decide your fate, the last instalment of which is now almost old enough to be a university student?

Trudy: Excuse me, that one author you must not name is still selling books, is still tweeting, and those tweets are still hitting the headlines. That doesn't sound like being silenced, because that is the opposite of being silenced. Remember, Bob, we are talking about hypothetical revolutions, and so far one has not happened to target that one author. Now, let Alice finish.

Alice: Thanks a lot, Trudy. What doesn't make the news are why such outbursts of so-called “mob violence” became necessary in the first place. When you hear that a workers' strike is going on, you think to yourself, these lazy people want a pay rise while they don't do their job, and they're coercing their employers. But behind their visible, short-term coercion is subtle and long-term coercion, done by their employers to them, by asking them to endure inhumane working conditions, decreasing pay when adjusted for inflation, and systematically high rate of burnout. And when those workers are public transport staff, are NHS staff, or are teachers in public schools, it is this government who has already been coercing all of them for years on end.

Bob: And the protests among university students?

Alice: Behind every protest is a genocide that both the Tory party and the Labour party actively do, all day, every day, using taxpayers' money while actively ignoring how the majority of this country would like the genocide to end, forever. And I agree with you on one point: all violence is always bad for somebody, so, would you say that the violence that you do not personally get to see are necessarily less horrifying?

Bob: So you call what is done by this government "law-preserving violence"?

Alice: Precisely. Whereas workers' strikes, as well as the making of new work contracts by the employers, are law-making violence. Even the signing of a contract can be violent. Any of you who unfortunately have to pay high subscription fees for our techno-feudal masters, because you want to read papers, watch anime, play games, even simply to keep in touch with friends, would certainly confirm.

Trudy: But you've always got the right not to use google or amazon or microsoft or apple or ex-twitter or any one of the other privatised commons without which your livelihood can and will be affected severely.

Bob: And workers do have the right to strike if they are willing to let their livelihood be affected severely.

Alice: And why do you think the livelihoods of striking workers are always affected? It's because even those workers who simply decide to not clock in for the day and spend their time chilling out in the sun are, in the eyes of the law, already violent subjects. If you live in the UK and there's a strike, but the striking workers are under a different employer than yours, then you're not allowed to join them in striking. If that doesn't imply a negative attitude to the exercising of your legal rights in the realm of habits, I don't know what does. And as soon as you can be framed as violent, any harm that you subsequently receive gets trivialised and ignored. Sure, why care about these striking workers' livelihood, why care about the cops shutting them down in the most cowardly of outbursts, when these workers, though they do not act visibly, are already seen as mobs, already the part-of-no-part?

Trudy: Ooh, watch out, everybody! Here comes another jargon.

Bob: I recognise that one. Rancière. And as long as I can beautifully pronounce the names of the French philosophers, I shall never worry about their thoughts.

Trudy: And you're off topic now, Alice. How could strikes compare to revolutions? I mean, strikes usually don't last very long. I have heard of peasants' uprisings that last a year or several years. And so peasants' uprisings cause more violence than strikes. And revolutions usually last longer than peasants' uprisings. Ergo, revolutions are even more violent than peasants' uprisings.

Bob: Precisely. When does a revolt become a revolution? When does your 21st-century well-organised and voted-for strike become another Big Swamp Village, and your rebellion against the Qin Dynasty is quickly quashed and only becomes slogan fodder for some radically strange people whom you shall never see or hear from, who lives millennia down the line?

(Alice looks at Bob as if through the looking-glass).

Bob: As you asked in the beginning, Trudy, you do need to stop before the revolution begins. Let's cut the branch that might have grown full straight, and burn we must Apollo's laurel-bough.

(Trudy is not really getting the reference here, and falls into awkward silence. Alice is, finally, almost amused.)

Bob: Indeed, and the historian's task is to draw the objective line between those time-stretches and those levels of violence. As an Artist, though, I would like to entertain ambiguities. Maybe there's a bit of Jacobin in every one of us, everywhere, all the time. And that's what's horrifying about the French Revolution. I'm going to explore that in the sequel to my novel, "To Wobble Away from You", where Robespierre's friend, like the one in Henri Béraud's sentimental novel, discovers that he's secretly just like Robespierre, or intend to possess him, or maybe even to be possessed by this bloodthirsty dictator, and so this friend, he falls into an identity crisis ...

Alice: I see that neither of you are listening to me. The Russian Revolution was sparked by the strike of women working in the textile industry. Bob — Dr Kinbote — you clearly do your own research in preparation for your creative output, you know that the revolutionaries in every revolution knew when they were doing a revolution. You don't need to draw the line after the events. That is the one thing that we as non-historians can still very responsibly do. And no, there is no such thing as historians being objective. But, again, this show is not exactly concerned with objectivity, is it?

Trudy: How do you know that it's not just an uprising? Surely, by the time you've guillotined, say, the ten-thousandth aristocrat, you would want to question yourself regarding what you're doing?

(Trudy takes out a lean slice of cake and starts eating.)

Alice: I would indeed question myself, but not in the way you seem to be suggesting that I do. You have a point, Trudy, in that most revolutions have longer-lasting effects than uprisings do. As indeed, in actually-existing socialisms, it was always revolutions, and not uprisings, that could, and indeed managed to, uproot old regimes forever. My question is therefore about the planning of the new regime. Take the French Revolution.

Bob: Have you never heard of the Bourbon Restoration? Napoleon was the most ingenious emperor since Alexander met Hephaistion, but Napoleon lost eventually. He died a prisoner.

Alice: Toussaint l'Ouverture also died while extralegally arrested and kept in solitary confinement by Bonaparte's marshals. Exactly one of these two deserved to die a prisoner. Exactly one of them deserved to die at all, and he's not called Toussaint. If you had sincerely believed the Corsican who lost land and principles, the Tsar-kisser who was capable of neither virtue nor terror, to somehow still be a revolutionary, you would have definitely hated him, you would have been disgusted by him, and you would have titled him a bloodthirsty dictator. And yet you put his ingenuity out of all context, and therefore insult even this ingenuity.

Bob: You're avoiding the question. I'm saying that old regimes can, in fact, come back.

Alice: Anything "can" happen. The entire universe "can" suddenly turn into piles of porous cheese, and nobody would be left to give the good news to the ghost of G.K. Chesterton. Well, except me, I guess. I'll remain while everyone else spends the rest of eternity swimming in their long-owed nutrition. Why, I'm too bitter, too pedantic, to dissolve even among the richest of bacterial cultures.

(Trudy is now choking on their cake.)

Alice: As long as your vision is one that centres threats from without, anything could be seen as the beginning of a butterfly effect. But the effect of the revolution was profoundly felt when the restored monarchy, far from the normative status it used to have pre-revolution, is largely seen as a subversion, as supposed to an extension of the norm. And you can always find your counter-examples, but in both the Russian Revolution where the Tsar abdicated and was later killed out of emergency, and the Chinese Revolution where the last Emperor survived and tried to become a puppet emperor under imperial Japan, you never have a restoration that spans the entire land of the country. The point is exactly to reach for the theories that make such a reversal impossible to even imagine.

Trudy: Are you saying that history has a definitive direction of progress, and that the Bourbons were simply unfortunate in that they happened to be travelling against the tide of the times?

Alice: Nobody is travelling against the tide of times. And there is no tide separate from each of us; every individual is already part of such a tide. As much as no one person can, without the help of entire classes of people — and yes, "classes" plural, for Mao was notable for his emphasis on the collaboration between peasants and proletariat factory-workers and even part of the petit-bourgeoisie — build an entire revolution from scratch, we must also be aware: no one person can be so unfortunate as to be completely independent from the revolution, as someone passively observing the revolution, as someone whom the revolution happens "to". This is what universal equality looks like: from the nobles who had privilege own to lands they barely visited to those enslaved since childhood, nobody could say they had no agency, rights, or responsibilities in a revolution.

Bob: Well tell me what agencies Antoinette had then. She was only a depressed mother —

Alice: A depressed mother who chose to ask the troops of her father's country to quash the army and citizens of her husband's country. She wanted to ensure that she survived and maintained her right as the queen no matter which side won.

Trudy: But surely Robespierre was wrong to demand the arrests of Danton and Camille Desmoulins, who were his friends to start with? I mean, the revolutionary tribunal was not controlled by Robespierre, and the tribunal had the choice to acquit the Dantonists, but even with that possibility in mind, you still wouldn't in your sane mind cause trouble for your friends to have to defend themselves in front of the jury, would you?

Alice: Now you are asking an interesting question! What do you think separates Robespierre's actions from the two of them?

Bob: That Danton sold himself to the British (as if to clean his mouth, he spits right after saying the word "British"), and Desmoulins wrote his newspaper without fact-checking, but Robespierre did neither of those two things — that Robespierre was the "Incorruptible", and he always presented to the National Convention what was evidenced as the truth?

Alice: That is the least of Robespierre's concern. You only need to read Robespierre's speech after the arrest of the Dantonists to say that it wasn't any good action on Robespierre's part that made him think of himself as less gullible, as, indeed, "incorruptible".

Bob: Ah, you admit it then? You admit that Robespierre thought of himself as ontologically untouchable by the law, whatever actual position he occupied within the Convention?

Alice: No. Quite the opposite. Robespierre, at the time of the fall of the Dantonists, was already thinking of himself as equally involved, and equally active in the revolution, as the Dantonists were. And so as long as the Dantonists could be condemned at any moment, so could Robespierre. Neither his past friendship with them, nor his difference in opinion, nor his abstinence from indulgence was focused on, because if there was one thing Robespierre avoided, it was being a hero of the revolution, being a hero atop the Convention, atop all citizens active and passive.

Trudy: Wait, I saw in a film that Robespierre personally asked his men to go to the printers' workshop, where they were publishing Desmoulins's Le Vieux Cordelier, and those men wrecked the workshop, confiscated their copies of Desmoulins's newspaper, and then threatened to arrest the printers...

Bob: Wajda's Danton. The masterpiece of 1983. It makes me fall in love with Polish cinema all over again. One of the most brilliantly threatening Robespierre I have the fortune to have seen in media.

Alice: Ok, watch out for the word "threatening", because I'm about to use it. Robespierre never threatened physical violence against the printers working alongside Desmoulins. That was one of the many factual errors of that film. I'm not a film critic, and besides, Florence Gauthier has already thoroughly sick-burnt the ever-loving sick-burn out of Wajda. But even in such a biased film, one thing was done right: Danton was indeed represented as a nouveau-riche, who was somehow remembered as a hero of the true proletarians. And I think we can all agree on the certain harms — not even the dangers that lurk, but the harms that already is — of hero-worshipping. (Suddenly becoming quieter in voice and less formal in tone) i shall not advice anybody to spit at andrej wajda's plaque, located at the intersection of józefa hauke-bosaka and śmiała streets in warsaw's żoliborz oficerski. i give this address so that our entirely apolitical audience can know they shall not forcefully eject their saliva at wajda's plaque. moving on: I am not here to tell you about what good things Robespierre did. If he was adamant that he did not want to become separated from the people, from the revolution, and seen as someone independent from the people, from the revolution, then I am also adamant that we move on from him. You don't really care about his personal life, do you? You don't have any stakes over whether or not he secretly wanted to retire early and spend the rest of his life learning to cook for his found family and write poems for Saint-Just and Le-Bas to make into operetta-like songs.

Trudy: Indeed I'm getting bored of him.

Bob: So would you say that Robespierre was a successful person, then? As an Artist, I'm of course open to all kinds of definition of the word "successful", even if it's a success at making himself condemnable, and indeed, eventually extralegally condemned.

Alice: Ok, quick-fire then. When you hear the word "successful", Trudy, what is the first image that you see in your mind's eye?

Trudy: Oh, he was a gentleman with the fashion sense of the ancien régime, wasn't he? He had a powdered wig, and wore sunglasses, and had intricate white lace cuffs that surround his wrists ...

Alice: He couldn't afford lace. He wore fine linen. Ugh, this isn't about Robespierre the person though, is it?

Trudy: (ignoring Alice) ... and wore the neatest of breeches, and even his Adam's apple was especially perfumed to have the taste of ...

Bob: The bourgeoisie aesthetic. There it is. Robespierre managed to learn to be a professional lawyer, and he found the support of a well-to-do carpenter, and the ladies who heard his speeches live in the Convention's galleries found him attractive, all because the French Revolution did nothing but make the rich white men who weren't born into noble families gain the rights and privileges of ancien-régime nobles. Whereas everybody else, from the women to the people of colour to the gays to the lesbians to the bis...

Trudy: Why are you saying lesbians as if they are not also women? And gay men being women? Excuse me?

Alice: Ok, the carpet value judgement that the French Revolution was "bourgeois", and therefore unremarkable, is often rather insidious, since... — Bob, would I be correct if I call you a leftist?

Bob: Absolutely. Eat the Rich, and so on and so on.

Alice: So you're a leftist, and from what you have said about the queer and trans community so far, I gather that you sincerely believe in the leftist cause in a broad sense. And yet, you are still not immune to reactionary propaganda.

(Bob almost jumps out of his chair.)

Alice: To claim the French Revolution was, and aimed to only be, a bourgeois revolution, your central argument would have to be that the revolutionaries disposed of one set of hierarchy, only for the purpose of ushering another in. What you've done here, is that you've represented the revolution as a noisy crime that destroyed another crime, and so was flawed in the best case, and meaningless in the worst, insofar as it did not in one swift step go from the ancien régime to fully automated luxury gay space communism.

Trudy: But what if I've wanted just that? What if, here's an idea, jumping immediately into Fullo-auto-Luxo-gay-spa-Commo is good actually? If you are so confident that your platonic vision is going to succeed, then down with the terror! Just bring on the good results already!

Alice: (somehow managing to ignore Trudy) ... And this argument, this "bourgeois revolution" judgement, it depends as much on what the French Revolution was not as on what it was, and so it is as ideological as it is historical. Finally, a good use for the non-historian that I am. it's possible that one gains access to all primary sources and insight to none, and so comes to this very wrong conclusion. And this is where I must warn you, Bob: as much as you've been clever enough to recognise French philosophers, you still need to watch out for the done-your-own-research-and-indeed-accessed-many-primary-sources-but-doing-so-very-poorly pitfall, that writers of historical novels are always tempted to fall into. Because the question is not simply "why did the terror happen" but also "why was the terror a necessary step between the ancien régime and any vision of utopia".

Trudy: And why was it?

Alice: The shortest answer is that for a revolution to succeed you need everybody's participation. You need every citizen to agree on a set of new rights and new principles. Universality, basically. Now here's the difficult part: universality doesn't fall from the sky. It appears like an intrusion. It surprises even the people doing it. So you cannot simply programme an entire country by hitting a button. Those who get hit, I am afraid to say, might as well include yourself.

Trudy: What if revolutionaries cut off the supply line of my local supermarket? Or the electricity to a children's hospital?

Bob: My research has told me that this didn't happen very often in history. Things like a flood or an earthquake might end up doing those things, but revolutionaries have the agency that natural phenomena lack.

Alice: That it is, Dr Kinbote. If your idea of a revolution involves a disruption to the supply line of the most basic of goods and services, you need to ask yourself: why are those supply lines so risky to maintain in the first place? If any temporary flood could claim the electricity of an entire hospital, then the hospitalised patients' lives and livelihoods are being artificially devalued already.

Basically though, detractors of revolution-as-a-concept tend to do this: if they see a revolutionary from a peasant or worker background, they dismiss them as jealous losers; if they see a revolutionary from a bourgeois-proper or noble-family background, they dismiss them as people with hypocritical morals; if they see a revolutionary who's not exactly rich and not exactly poor, then they dismiss them as jealous losers with hypocritical morals.

Bob: I don't think this is the show where we analyse why things happen in real life, Alice. Real life is messy and illogical.

Alice: (somehow managing to also ignore Bob) While we could, in a now-clichéd Žižekian move, assert that "robespierre's problem was not that he was too radical, but that he wasn't radical enough", we must not lose sight of how the new-left (derogatory) formula of either "robespierre was an anti-liberal bourgeois" or "robespierre was an anti-bourgeois liberal", both of which Yannick Bosc has already dispelled, necessarily implies reductive identity politics. And the problem with identity politics is that it supposes that a person cannot care about a social issue that does not immediately affect their material livelihood.

Bob: these new-leftists that you speak of, Alice, are they in the room with us right now?

(Alice casts a glance at you, the reader)

Alice: They might as well be. A psychological inconsistence on the part of these new-leftists is that, if the French Revolution really was, as they claim, an unimportant bump near the beginning of the long road of capitalism, and an unworthy prequel to the various revolutions in the 20th century, then these new-leftists themselves would never spend so much time and energy arguing against its memory. In doing this, they basically admit that they're incapable of writing a history of international leftism, without having the French Revolution as a flawed and hopeful first.

Bob: But isn't that just the founding of the version of France as we know it today? I mean, in feudal times you found a state by conquering and looting. Just because the state being founded is a king-less state, doesn't make that conquering and looting any less necessary. Even if you imagine a timeline where Napoleon never lost the last Coalition wars, he'd had to constantly threaten the rest of the crowned heads of Europe not to start the Eighth and the Ninth and the Umpteenth Coalition war.

Alice: Ok, I've already answered earlier why Bonaparte doesn't count as a revolutionary, and now you've also said the word "threaten" one too many times.

Trudy: What's wrong with threatening people?

Alice: Ha, what is wrong with threatening? I'm glad you asked. If you want to threaten some people, you'd have to maintain that those people are guilty, and you'd have to sustain that sense of guilt. You'd have to hang the metaphorical sword above their heads, and ensure that no matter how they repent, how they apologise, how they do their reparations, that guilt shall remain. Even if you want to be extra wholesome, and always forgive your enemies no matter what they've done — and this is not about me, I don't want to tell you whether or not to forgive your enemies — even if forgiveness is granted from your side, the threatening stance remains. You forgive out of your own decision to leave things behind in their flawed status, and not because enough reparations have been paid. Because, let's face it: as long as we see time as linear, a person who is already your enemy is unlikely to ever do enough reparations for you to stop calling them your enemy. If you forgive them, good for you: now they are the enemy that you've forgiven. Forgiven, but still the enemy.

Bob: Forgive but never forget, as the saying goes.

Alice: And this is not just for personal conflicts and whether or not they end in forgiveness. In most cases, the death penalty is exactly such a threatening violence. When a criminal is led to execution, that doesn't really do anything to this one criminal. Because death is something that doesn't happen to you; you're always only observing others die. And if no reparation is ever enough, then paying one's own life for one's crimes would also not be enough. No, executions serve to warn other criminals, whether they're already arrested, or still avoiding arrest: this is your fate, these gallows, and you shall spend the rest of your waking hours fleeing from this. Of course, the death penalty is only one of the more obvious ways through which a state gains monopoly to violence. Prisons aren’t inherently any less threatening. They’re literally there as boundaries to be indefinitely maintained. In the UK, when a person is persecuted, their case says “R versus [their name]”. They’re literally the nobody being reminded of their guilt, because they are framed as enemies of the monarch. Everybody will be able to name the king or the queen, but nobody will ever be able to name every one of the condemned. Such violence, done by the state to the individual person, is precisely the opposite of Terror. It quashes any individual agency, any possibility at clearing one’s name. Hence we can say that the violence that founds a state necessarily threatens, even if that threatening is empty, and even if the person being threatened is already dead. You need only recall the outrage from conservative and not-so-conservative Americans (both Trudy and Bob recoil at hearing “Americans”) when you dare to commemorate _ _ _ _ _ Bushnell.

Bob: I'm against the death penalty. As for prisons, I cannot see an effective way towards reform yet...But that’s not the point. My point is, prisons and executions featured heavily in the vast majority of revolutions, and that’s against my principles. I’d like you to name me one successful revolution where purges and political prosecution didn't happen, where nobody died. Go on, I'll wait.

Alice: I kinda wanted to say that death is a certainty no matter which historical period you look at, but you know, I’m not a historian, so why listen to me?

But no, what I really wanted to say is, revolution doesn’t only change whether the king is in charge or a convention is in charge, it changes literally how the enemies of the state are treated.

To use the example of criminal prosecution again, those that are executed — and for the records, I do not believe anybody ever deserves to be executed either, I’m just talking about people like the Dantonists — when they perished on the scaffold, it was their guilt that stopped existing.

Bob: So, forget, but never forgive?

Alice: That is the aim. Well, what is forgotten is the hubris of the individual. You remember the names of Danton and Desmoulins and Philippeaux and Lacroix d’Eure-et-Loir, but you don’t remember what kind of self-important embezzlement and fabrications they were up to, and more crucially than that, you don't remember the name of the president over the Convention on the day they were first suspected, on the day they were arrested, on the day they were tried, and on the day they were executed. Take an even more extreme example: everybody has heard about Antoinette, and many have heard of her friend, Madame de Lamballe, who died in the September 1792, when the sans-culottes of Paris executed those whom they believed could collaborate with the very-quickly-approaching Prussian troops. Very few people can remember the names of the people who killed Madame de Lamballe. It’s always how the noble ladies and the gentlemen and the non-binary highborns were cute and cultured and well-mannered and soft-spoken, and they’re contrasted against this nameless mob, and we as modern-day readers are told, again and again, that these nobles knew not why the mob even was there.

Trudy: Could nobles themselves join the revolution?

Alice: Why they could. They had the imperative to. If you're relatively rich and have more spare time, you're likely to be among the first people in your country to be literate. And if you manage to be literate, you can manage to become literary. And then you'd be the first readers of Rousseau and of Voltaire.

You could even argue that, since nobles were significant proponents of calling the Estates General, it was the nobles who started the French Revolution. Even though their personal goals ranged from “wanting to do a job outside of their duties as nobles” to “wanting to not pay taxes” to “sincerely believe that the king’s powers should be limited” to “willing to give up their own privileges and commit to the republican cause”, the noble status on its own did not limit anybody from having the agency to act.

Literally, there is no such thing as the "target audience of a revolution", because nobody is simply the audience of a revolution.

I encourage you to read more about Michel Lepeletier, his younger brother Félix, and the maybe-Dantonist-maybe-Hébertist that was Hérault-Séchelles. As for those nobles who neglect to act, well, they don’t have to repay anything. They just need to be thrown into the void. It’s the individual’s violence against the state that produces this effect.

Trudy: Ok, in the beginning you talked about mythic violence and divine violence. Would it be accurate to say that mythic violence is when threatening, and divine violence is when hitting the target directly?

Alice: Basically, mythic violence = the violence that founds a state. You've got roughly two types of theory of how any state comes to be: the social contract theory, and the theory where you think of the state as the protection of the interest of a particular class. The latter basically states that every state started off by being illegitimate.

Bob: Conquering and looting?

Alice: Precisely. If you apply this to the modern history of France, then the way we talk about Bonaparte largely reflects what we think of illegitimate violence. In short, Bonaparte was more similar to Louis XVI — or, if you're being generous, Louis IX — than he was to the Jacobins he professed to have inherited his politics from. And even if your only measure is body-count, Bonaparte still costed the lives of more French people per year than any pre-thermidor conventionnel ever did.

Bob: But why "divine" violence? What's divine about the (horrifying word ahead) Reign of Terror?

Alice: I'd avoid saying the "Reign of Terror" because, as I have said just now about Bonaparte, 1792 to 1794 was not the height of political persecution. The thermidorians gave way to unprincipled threatening-by-death of the remaining montagnards. The directoire was even less self-organised, and that paved way for Bonaparte.

Bob: Ok, Robespierre didn't want to personally gain supernatural powers, I can concede that point. Even his harshest detractors wouldn't go near that trope. As an Artist, I must be moderate in my criticism, so I won't go near that trope either. What is it that made you, a champion of the Robespierrist cause, use that particular word?

Alice: Ok, you have a point, the name is a confusing one. Out of curiosity, are either one of you religious?

Trudy: Nah.

Bob: Not even spiritual, only high-spirited.

Alice: Great. While I suspect that we are three different types of atheists, what concerns the word "divine" here is not "actually gaining powers beyond the human scope". No, the transition from mythic to divine is like the transition from paganism to monotheism, from powers that reference each other to one power that has no reference for its own power, from powers that be to a power that only emerges at instances where it surprises even itself. The Old Testament is full of examples of laws being used as guidance and not as commands for exactly this reason: you decide without anyone, not even the Supreme Being, guaranteeing your moral purity. Purity itself is already a myth.

And I'm afraid that the very concept of democracy is now being used as if it was a synonym of purity, as if was a pagan belief. You hear those twitter users with marble statues as profile pictures singing their praises to "their" Western philosophy. You see the first-past-the-post system being maintained as if it was some ancient tradition. You see the Labour Party quickly devolving into Tory-lite, and somehow by being the lesser-of-two-evils they consistently pat their own backs, scratch their own armpits, and do various other self-inflicted vulgarly pleasurable things.

Bob: I'm aware that we tend to avoid this question, but: How is the storming of the Capitol different from the storming of the Bastille?

Alice: Ok, do you know many names of the people who physically filmed themselves trespassing into the Capitol Building? Do you know the name or pseudonym of the persons who inspired them?

Trudy: I think everybody does now.

Alice: Alright, then, do you know the name of anybody who personally fired glass bottles at the Bastille guards? What about the women who used their femininity as decoy to bypass the guards? Who were personally responsible for ending Jourdan de Launay's whole career, and then his life as well?

Trudy: I don't think anybody knows that.

Alice: This was why I mentioned the part-of-no-part right there. The point of a revolution is not for one person to become a Robespierre, a Lenin, a Mao, a Castro, or anyone else whose black legends we on the left still have to keep dispelling. The point is for us to become the stormers of Bastille, to become the sans-culottes in September 1792. Of course, it's understandable that you have your favourite historical politicians or soldiers or poets, and it's admirable to learn lessons from them. I cannot have enough of Kropotkin, and I'm not even an anarchist. But revolutions are specifically about how the anonymous proletariat rebels against that situation — and this next part is important — by tearing down both the bourgeoisie and themselves.

Trudy: I thought the proles only rebel to get more handouts.

Bob: Or, failing that, we can ask the bourgeoisie to be gentle with us.

Alice: Asking another class to be gentle with your class is nonsensical, because class conflict precedes class distinction. You're at odds with the bourgeoisie even before a dictatorship-of-the-bourgeoisie came into being with the directoire. And indeed, the principle of fascism...

Trudy: Scary word spotted!

Alice: The principle of fascism is not really "eliminating an enemy within" à la antisemitism. No, fascism starts when someone thinks that a strong enough political leader can effectively let the proletariat and the bourgeoisie to coexist while being gentle to each other. In that sense, the number of people subscribing to such a principle is already frighteningly large.

You simply cannot treat the class struggle the way you treat the struggle against queer-phobia or against transphobia. The day you end queer- or trans- phobia is the day where we in the queer community shall live in peace and harmony, and the people outside of this community shall also live in peace and harmony. But the day you end class struggle is the day where everybody still is, still lives, but not as their former class anymore. The day you end class struggle is the day where you neither need to have alongside you a revolutionary leader like Robespierre or like Lenin, nor need to become such a leader yourself. Of course, you would still have leadership to ensure that, for example, that power plants and railways can function.

Bob: So why is it that nobody is doing a revolution right now?

Alice: You have not been following the news in Burkina Faso, have you? Also, technically the Chinese Revolution is still continuing. You've also got revolutionary parties everywhere in the Third World...

Trudy: Ugh, I don't want to hear about the Third World. It's against my well-balanced principles to over-intrude into issues of countries that are not my own. Unless it's the US of A. Intercourse that stupid baka country. We're talking about revolution, the fashionable subject, and not the Third World. Your dream of a day of rupture in the form of popular uprising is going to land you in a cultish environment, Alice.

Alice: And I don't want to get into the differences between those who believe in a day of rupture versus those who do not, even though I can talk about how none of the French, the Russian, or the Chinese, at the time of their respective revolutions, predominantly believed in a day of rupture. They had no idea what you're talking about. Nonetheless, let's remember that those three countries are not the only examples. You only need to look at how many countries in the world have done a revolution in the past two hundred years to know that a revolution does not necessarily require any one particular type of religious belief.

(This is where Alsip turns off the telly. The following is Alsip speaking directly to you, the reader.)

Belief. It's easier to define yourself as what you positively believe in, than as what you do not believe in. To say "I don't believe in the ancien régime" is easy. To say "I believe in universal suffrage and the granting of citizenship to all formerly enslaved people" is much more difficult. To say "I don't believe that there was such a thing as the Reign of Terror" is easy. It's much more difficult, and much more effective, to say "I do believe that the anonymous proletariat can and should fight the few who defend a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, and in this process befriend any petit-bourgeois who are willing and capable to systematically abolish their own privileges".

This is also why simply stating that you are anti-capitalist, if it used to work as practice, now no longer works as a theory. This is also why I take issue with the slogan "Eat the Rich", because such a goal presumes the existence of a certain class that you construct as "the Rich". And as much as I may pride myself on offending individual capitalists, I'd argue that, for me and my fellow Marxists, this cannot be the only tactic. A more radical slogan would concern the much less dramatic, and seemingly much more mundane action of feeding the poor, of doing the simplest thing that is the most difficult to do: establishing order from within the chaos of late-stage whatever-ism. To relish in the excess of destroying capitalism is not the thing that differentiate us from fascists. To go from the liberation from the system to a system of liberation, on the other hand, sets us firmly against the fascists, whose liberation from the system stops at a system of artificially-maintained harmony between classes, a system so brittle it constantly requires war with other countries to obfuscate its internal contradictions.

The liberals (derogatory) who say that the French Revolution was good in theory but bad in practice, who hail the storming of the Bastille but abhor anything that happened between 1792 and 1794, they simply overestimate the power of habits. They deem habits as above all laws. They could even agree that every person has the legal right to unionise, to strike, to revolt, and to demand a change to the constitution of their country. But, they would ask, are we really used to going to such lengths and measures? Are we really allowing the possibility that someone as beautiful as Hérault-Séchelles could be guillotined wrongfully? Are we ready to face something like the war in the Vendée, with such a both-are-worse situation as that of Carrier versus Charette (i.e. the unprincipled Left versus the populist Right)? A Marxist who wants to recognise all history of revolutions (with all the flaws that have been persisting) as their own shall, with much grief in their heart, answer Yes and Yes and Yes.

These very liberals often admire the Dantonists: they want a revolution that can be walked back on. They actively want to cut the branch that might have grown full straight. They want Apollo's laurel-bough to be burnt. To paraphrase No. 33 from Kafka's Zürau Aphorisms: anti-capitalist liberals do not underestimate habits, for they allow their own habits of limiting subjective violence to be violated by their own negligence towards systemic violence, and in so doing, they are like the capitalists that they have been anti-ing.

I would like to say a very Happy Birthday to Louis-Antoine Saint-Just. The time is already 25th August 2024 where I am. This is now the 257th of the Many Happy Returns.

This piece is supposed to be all about how Saint-Just resembles a painting by Paul Klee, a painting that Walter Benjamin admired and wrote a significant comment about, Benjamin, whose Critique of Violence much influences my current analysis of the French Revolution and of the Russian and Chinese revolutions. It turns out that, since my degree was in maths and not in history, such a Benjaminian reading-of-Saint-Just is not yet clear to me.

I must note that Benjamin himself actually saw the French Revolution as the violence that founds a state. It was in Žižek's Violence (2007) that the clear equations of "French Revolution = aiming at (though didn't manage to achieve) a dictatorship of the proletariat = the abolishing of the classes of proletariat and of bourgeoisie at once = the boundless destruction of guilt = divine violence" were established.

As I have said before, if I could hypothetically talk to Saint-Just for only a day, I would be sure to say that his Constitution and his strategies and his principled personality are all continuously admired and influential to this day, and yet I would still be very hesitant to describe to him the world that we currently live in.

And that was why I came to the realisation that commemorating Saint-Just cannot stop at making memes about him, translating papers about him, or telling those who have been duped by his black legend about How Saint-Just Was Good, Actually. No, I need to start with my own theory-reading.

I've basically put into this piece all the research and thoughts that I'd had since I started regularly reading about the French Revolution in 2023, and even some since earlier. I'll obviously still be wrong about a lot of things, and so for those of you who spent time reading all the way through this piece: I welcome any and all criticisms. Please, just tell me and I'll either edit this piece or do better in the next long post of this kind. and

if I persist while knowing I am wrong,

the Archangel of Terror strike me down.

I would like to thank, in no particular order, my mutuals Lin @enlitment, Aes @aedesluminis, Adam @czerwonykasztelanic, Nesi @nesiacha, Kes @sparvverius, Maki @makiitabaki, Claude @18thcenturythirsttrap, Jefflion @frevandrest, Lazare-Petit, and Citizencard @citizen-card, for their patience and encouragement as I write my various frev-related posts and translations. Die Partei hat immer recht.

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#saint-just#louis antoine saint just#frev shitposting#alsip.txt#cw liberal (derogatory) takes#cw misgendering#cw death#cw execution#cw genocide

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

i hate this feeling. like i have hope for the future but no matter how much, how hard i try to get better and improve myself and do my best its never enough. its like im almost there, almost on the path to healing but everytime i get close enough im shoved back to where i started. i wake up every day and think today is going to be the day it finally works. i keep trying every single day to commit to healthier habits but they still aren't getting easier and i don't feel any better and now i'm just even more tired than before. staying in bed all day makes me feel like shit but so does doing anything. i just want to get better and i hate feeling like im so close but never really getting anywhere. i feel like im stuck in a loop at this point.

#vent#tw depression#adhd#adhd problems#tw depressing stuff#depressing shit#executive dysfunction#mental health#mental illness#neurodivergent#vent post#personal#tw depressing thoughts#vent blog#cw vent#personal vent#venting

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This song will never be added to pjsk because it's too suggestive" well first thing first through Vivid Bad Squad all things are possible so jot that down,

#jay rambles.txt#posts that would get me publically executed on twitter. hopefully not here#regardless of what your opinion is I just think VBS getting the bulk or these is very funny#cw suggestive

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hisoillu#illumi zoldyck#hisoka morow#prshp don’t follow#despite my respect for canon hisoka’s very creepy and gross characterization#& the very interesting execution#like it’s super well done he makes my skin crawl#but i won’t characterize him as one in my brain palace#becaus it makes me super upset#and being insane and self indulgent is my top priority#SHOUT OUT TO STRETCH MARKS ILLUMI#THE PERSON WHO SAID THAT I LOVR YOU#suggestive language cw#just in case ❤️#hunter x hunter#hxh#hxh fanart#illumi#hisoka#hxh illumi#hxh hisoka#illuhiso

131 notes

·

View notes