#cross continent trip 1998

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

25 Years Ago: My first cross-country adventure

The Bay Bridge, which I first saw on Thursday 19 February 1998. This photo taken on 24 June 2022. Camera: Olympus XA2 Film: Fuji 200 I’ve lived on the West Coast of the United States for almost twenty-three years. I’m quickly reaching the point where my West Coast life will be longer than my East Coast life. Quite the accomplishment! It’s even more the accomplishment when you consider that a few…

View On WordPress

#alternative comics expo#ape#Bay Area#canzine#comix#cross continent trip 1998#small press expo#spx#zines

0 notes

Photo

‘Endangered Wildlife’ Carved Lantern, October 2021

For several years Eco Zhang has been carving intricately designed lanterns for Dalston Curve Garden’s annual Pumpkin Lantern Festival. We were unable to host our Lantern Festival this year, but nevertheless Eco has created a beautiful lantern and it is one with a timely and vital message.

As world leaders gather in Glasgow at the COP26 summit to discuss Climate Change, including its devastating impact on nature, habitats and biodiversity. Eco’s poignant creation is illustrated with wildlife from across the globe, all endangered to varying degrees, some to the edge of extinction. In her own words, she describes the thinking behind her artwork;

“The theme of the pumpkin is inspired by my trip to Namibia last year. Seeing the stunning nature and wildlife has changed the way I see our environment. The balance between human and nature needs to be put at the forefront of sustainable development. We need to remind ourselves that we are living on the same planet sharing the same valuable resource with many others”

We’ve listed below the endangered creatures that have been illustrated by Eco and we’ve included information about them from the World Wildlife Fund’s website. You can read more at worldwildlife.org/species

The Giant Panda, whose status is listed as ‘vulnerable’ is threatened by habitat loss in the forests of Southwest China. Severe threats from humans have left just over 1,800 pandas in the wild.

The Amur Leopard is important ecologically, economically and culturally. Illegal wildlife trade and prey scarcity in North-Eastern China & the Russian Far East have led to its status being listed as ‘critically endangered’.

The rarely-seen Saola, often called the Asian Unicorn, was discovered in 1992 in North-Central Vietnam and is already ‘critically endangered’. Scientists have categorically documented Saola in the wild on just four occasions and none exist in captivity.

Sunda Tigers — estimated to be fewer than 400 remaining today are holding on for survival in the remaining patches of forest on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia. They are listed as ‘critically endangered’.

The Enigmatic Owlet-Nightjar, endemic to New Caledonia’s Melaleuca Savanna and humid forests, has not been sighted since 1998. The bird has been classified as ‘critically endangered’ as its population is unlikely to number more than 50 individuals.

Populations of Black Rhino declined dramatically in the 20th century at the hands of European hunters and settlers, with numbers dropping by 98% to less than 2,500, between 1960 and 1995. Thanks to persistent conservation efforts across Africa, Black Rhino numbers have doubled from their historic low 20 years ago to around 5,600 today, although they are still considered ‘critically endangered’.

The ‘endangered’ Asian Elephant is the largest land mammal on the Asian continent. They are threatened by loss of forest and grassland habitats in South and Southeast Asia, as well as human-elephant conflict, poaching and illegal wildlife trade.

Humans have encroached upon the territory of the Cross River Gorilla, clearing forests in Cameroon and Nigeria for timber and to create fields for agriculture and livestock. Its status is ‘critically endangered’.

Because of ongoing and potential loss to their sea-ice habitat, resulting from Climate Change, Polar Bears were listed as a ‘threatened species’ in the US under the ‘Endangered Species Act’ in 2008.

North Atlantic Right Whale is one of the most ‘endangered’ of all large whales, with a long history of human exploitation and no signs of recovery despite protection from whaling since the 1930s

The ‘critically endangered’ Hawksbill Turtle is threatened by the loss of nesting and feeding habitats in the world's tropical oceans, by excessive egg collection, fishery-related mortality, pollution, and coastal development. It is most threatened by wildlife trade.

The Northern Brown Howler is one of the world’s most endangered primate species, with potentially as few as 50 mature individuals in the wild. Its conservation status is ‘critically endangered’ because of the destruction of its habitat in the forested parts of Brazil.

While the Blue Throated Macaw has a high population in captivity, in its native home of North-central Bolivia it is on the verge of extinction, with estimates of only between 350 - 400 birds surviving. It is ‘critically endangered’.

While it’s hard not to feel depressed, almost to the point of feeling helpless, when reading about these levels of habitat destruction and species decline, it makes us even more determined to double our efforts to use all of the Garden’s resources and platforms to fight for nature and biodiversity, beginning with what we can do here at home in Hackney.

Thanks to Eco and her pumpkin lantern for focusing our attention in such a bittersweet way. You can see more of her beautiful art work at: instagram.com/ecozhangdesign

Thanks to Sandra Keating for her lovely photos which are copyright Dalston Eastern Curve Garden.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

From left: Photo by Gi Naps/Getty Images; Photo by Rose Hartman/Archive Photos/Getty Images; Photo by Victor Virgil/Gamma-Rafo via Getty Images

Today, the House of Jean Paul Gaultier is relaunching its ready-to-wear line after a hiatus of six years. It comes 16 months after fashion’s “Maestro of Mehmed”, as journalist Georgina Howell dubbed her in the early ’90s, took her final bow as the brand’s designer, implying that this iteration of its namesake. will not be designed. Instead, the reins are taken over by a dedicated team from their atelier, with help crafted from the rotating doors of some of the most independent designers working today – Palomo Spain, Ottolinger, Nix Lecourt Mansion, Alan Crosetti and Marvin M’Tumo .

Since starting his own label in 1976, Jean Paul has been instrumental in turning underwear into acceptable outerwear, making sailor fashion sexy and, more generally, paving the way for designers to experiment with diverse and unexpected castings on the runway. have been responsible for. He also dedicated an entire collection – AW97 – to the fight against racism. The collection, titled ‘Fight Racism’, featured graphic prints of young anti-fascists with slogans printed on their chests.

In fact, with such a rich history behind it, and vintage JPGs becoming increasingly collectible since the recent renaissance—partly stemming from the Kardashians’ love of all things net—more thanks to the label’s revival. Couldn’t be the right time- the line to wear from now. Although it is a well-known fact that Jean Paul himself decided to step back from the category in 2014 after a somewhat tumultuous feud with Florence Tetier (graphic designer and co-founder). November MagazineNow serving as the brand’s creative and brand director, Ghar is poised to enter the field again. in an interview with WWDJPG’s general manager, Antón Gégy, described the relaunch as an opportunity to “celebrate Jean Paul Gaultier, its values, its archives and its history”. And what better way to raise the glass to the core of fashion? Horrible Instead look at seven of the most show-stopping moments from its most iconic era, the ’90s. Long live Gaultier!

Photo by Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

Madonna’s Conical Corset from the Blonde Ambition Tour, 1990

Back in 1989, when Jean-Paul Gaultier was told by an assistant that Madonna had told the audience, she was convinced that he was playing a trick with her. They knew how obsessed he was with her, just could not do be true But she soon found herself on the phone to the original queen of pop, making a match in ’90s fashion heaven. Naturally, Madonna already knew what she wanted: to create something for her that surrounded Jean Paul’s signature masculine-feminine crossover. Inspired by his love of the late ‘queen of Paris punk’ Edwij Belmore, Jean Paul conceived a pinstripe suit – the top of ’80s manhood – and a corset with the now famous conical bra, which he designed six years ago on AW84 had started for. /85.

Photo by Victor Virgil/Gamma-Rafo via Getty Images

Eva Herzigova’s cut-out dress, 1992

Thought harnesses were a new thing on the runway? Wrong! After all, you’re not known as a fashionista Horrible Without a sprinkling of kinks here and there, as this look proves well. Presented on JPG’s AW92 runway, this dress, so slick in its fit that clothes can even put on Eva’s body, exemplifies the powerful-yet-playful take on sexuality that serves as a throughline throughout the French designer’s body of work. runs as. Styled with bicep-clad opera gloves and proudly crafting the Czech-Italian supermodel’s bust, there’s a distinctive dome-y tone at play here, though no compromise on the beauty of the silhouette or the quality of the make. It speaks to an ideological throughline that runs through Jean Paul’s work – that no matter who a woman is or wants to be, she always has the right to be chic!

Photo by Pierre Guillaud/AFP via Getty Images

Houndstooth bodysuit inspired by Leigh Bowery, 1991

In an interview with iD in 2018, Jean Paul declared his love for the “London Way”, which means “just creating your own style, your own creativity and being free to do what you want to do”. When he took the idea back to Paris, it wasn’t very popular, but that didn’t stop him from creating his own trademark approach to design. He spent his youth in the 80s at famous London nightclubs such as Blitz and Heaven, where he met performance artist Leigh Bowery. In a nod to Bowery’s influence on fashion, Jean Paul sent down his interpretation of the Leigh Bowery Houndstooth bodysuit—which would later inspire Alexander McQueen for AW09 and Gareth Pugh for SS07.

Photo by Pierre Guillaud/AFP via Getty Images

‘Chic Rabbi’ Collection, 1993

For AW93/94, Jean Paul presented the ‘Chic Rabbi’ collection, inspired by the traditional dress of Hasidic Jews. Models in streamels and black suits danced to the sounds of a violinist who played live on the catwalk. The usual circle of supermodels was there, but Jean Paul also decided to cast someone who visually embodied the cultural context: a man with a big beard. During the ’80s and ’90s, designers were known for their casting choices, pioneering their diversity. “I’m fascinated by strong personalities, people who capture my imagination because they walk well down the street,” Gaultier explained in a 2014 interview. “Showing just one type of girl is a flaw,” he adds, “something I’ve always fought with. One kind of beauty – no. If I show a bigger girl, I’ll always show a younger girl.” will show.” It is now legend that Gaultier once posted an advertisement in a French daily newspaper release Looking for “atypical” models, saying that “facial distortions should not be avoided in application”.

Photo by Arnal/Garcia/Gama-Rafo via Getty Images

Mesh Tattoo Top, 1993

Back in 1993, the trend Declared this prestigious collection as “a startling vision of cross-cultural harmony”. While we’d be inclined to cringe at the somewhat reasonable look now that Jean Paul drove down the runway for the SS94 (which can actually be read as another nod to Leigh Bowery) it certainly Historical perspective. It also marked the debut of Jean Paul’s iconic mesh tops, which were inspired by a tattoo convention he once found himself spinning around – today, they are some of his most sought-after designs. The collection also includes heavy notes of punk, grunge, and 18th century men’s frock coats made in Jodhpur and denim in the typical JPG style. How did he ever find the place for all this?!

Photo by Pierre Vuthe/Sigma/Sigma via Getty Images

Björk!, 1994

Jean Paul’s celebrity friends don’t start and end with Madonna. A year after Björk’s properly titled debut solo album, First entry, Taking the music and fashion worlds by storm, she appeared on the designer’s AW94/95 show, about a magical train that stopped in a small village somewhere high in some mountains. And what, duh?! As you’d expect from JPG, the show was a mish-mash this time in terms of different styles of traditional arctic costume. The models trotted down the snow-covered runway (which almost tripped Kate Moss), decked out in a hell of a lot of fur, silk, wool, and leather.

Photo by Pierre Verdi / AFP via Getty Images

Op-Art Inspired Catsuit, 1995

Two women riding a motorcycle hit them. One of them descends and climbs onto a loft at a DJ booth. Jean Paul’s AW95 ‘Mad Max’ Show Has Started. As he was in the middle of designing the costumes for Luc Besson’s famous film fifth element In which Bruce Willis and Milla Jovovich fight a mysterious cosmic force, they had science-fiction in mind, which means it was technology and cyber-heavy. The bodysuit inspired by Viktor Vasarelli’s op-art paintings became the show’s most memorable aspect—now made super collectible by Kim K and Cardi B and partly responsible for the JPG-madness we’re seeing on Depop these days. Also on the show was Carmen Dell’Orefice, who walked with a live falcon on her arm and sported ornate football armor that lit up like a circuit board. Really prestigious.

Photo by Victor Virgil/Gamma-Rafo via Getty Images

trompe l’oeil torso top, 1995

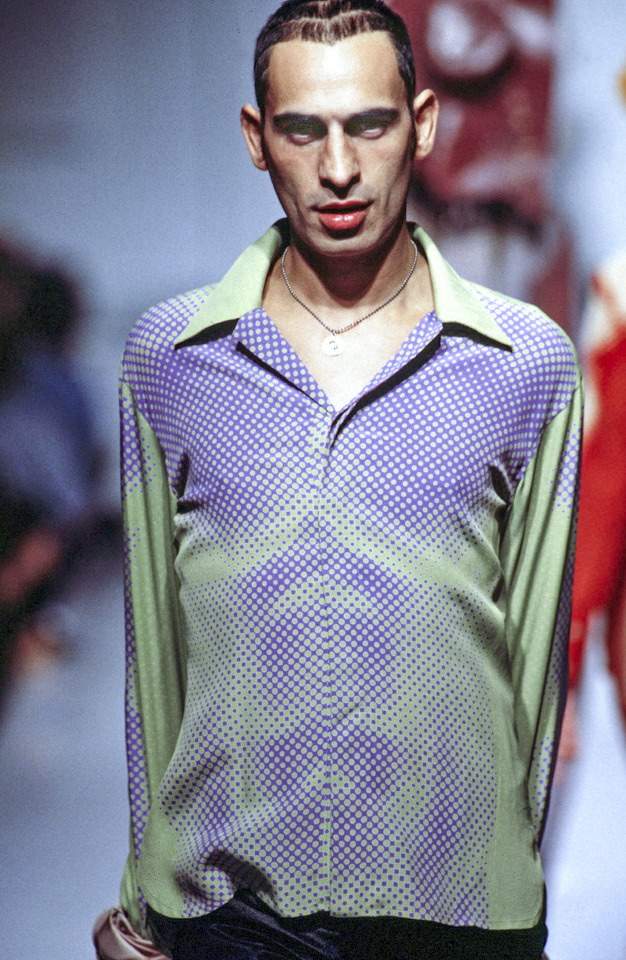

The next season, Jean Paul took his quest for sci-fi polka dots further, this time translating it into menswear. This time, however, he brought his knack for trompe l’oeil print placement to the table—skills he had previously flexed in the aforementioned Les Tautouzes, and even as early as 1992, when he sculpted the enviable Presented Printed Mesh Top with Toros. The look sported here by Tanel Bedrossiantz is perhaps a little more figurative in its approach, though no less direct is its infrared-style suggestion of what might lie beneath the longtime house muse’s button-down shirt.

Photo by Danielle Simon/Gamma-Rafo via Getty Images

JPG Set Sale, 1998

In a promo video for JPG’s new ready-to-wear line, Bella Hadid is wearing a big red ship on her head. In case you didn’t already know, it debuted at the Haute Couture SS98 show, where it takes us back to the Age of Enlightenment. It was a time of scientific progress, the advent of modern capitalism and of course colonialism. The ‘explorers’ were sailing around the world from Europe, ‘discovering’ new lands for them – a ship serving as a nod to the continent’s shameful past. Some say, however, that it was during the Enlightenment that the fashion we know today – as a form of self-expression that can be accessed by the public – first began to emerge, making the historical period a fashion show. became an ideal subject. .

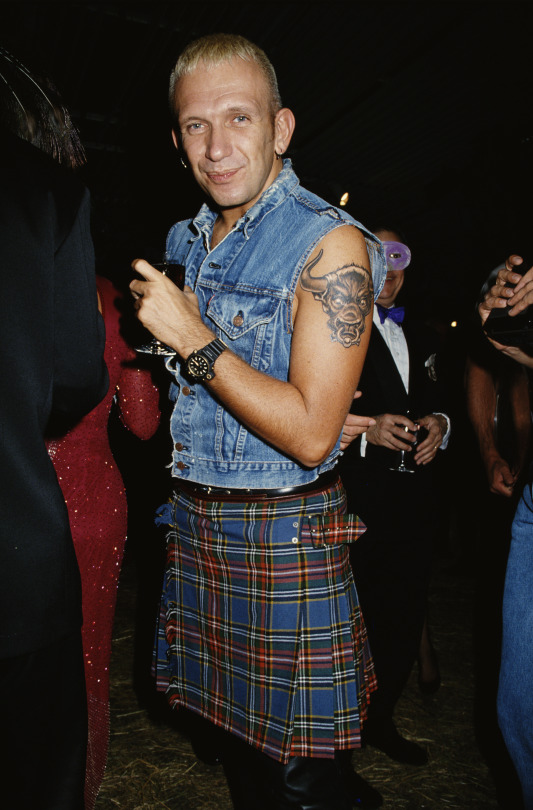

Photo by Rose Hartman / Archive Photos / Getty Images

Man Himself!, 1992

Sure enough, to write a list of Jean Paul Gaultier’s most iconic looks from his most iconic decade, and not for the man himself. Indeed, as Florence Tetier spoke to her before the label’s launch, “Everybody knows who she is!” whether it’s his striped Whether paired with a pleated black skirt or, as seen here, a denim vest and a punkish tartan kilt, JPG’s personal style has made her one of the most instantly recognizable designers of our time. Plus, there’s a direct connection between what she wore and what we then saw on the runway. While we may have never seen a proper, French Navy-standard Sailor From the designer, “he’s done a lot of stripes and nautical-inspired pieces,” notes Florence. “It’s really nice to see the link between the way he dresses and the way he designs.” we love you, Jean Paul! Follow iD on Instagram and TikTok for more fashion.

.

The post Jean Paul Gaultier’s most iconic 90s moments appeared first on Spicy Celebrity News.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flags of Pakistan Political Parties

Pakistan Peoples Party - Murtazi Bhutto's faction

image by Joe McMillan The Pakistani flag is derived from a party flag. The ruling PPP of Benazir Bhutto uses a flag which incorporates the basic flag design (white inclined crescent and star on dark green), the same is true for the separatist faction of the PPP let by Mrs Bhutto's brother. Both parties use vertical tricolors. Harald Müller, 28 October 1996 Yesterday I saw on the news a report on the murder of Pakistani politician Murtazi Bhutto, brother of prime minister Benazir Bhutto, and one of the strongest oppositions leaders. There was a short scene from archives of one of his speeches a few days ago, where he sat at the table on which there was a flag I haven't seen before. I suppose that it is the flag of his party (which I don't remember what it is called). The flag was a vertical tricolour of red (at the hoist) - black - green with a white crescent and star very similar in shape to the one on Pakistani national flag. The flag looks quite dark with this choice of colours, but quite effective if you ask me. Željko Heimer, 22 September 1996 This would appear very similar to an old flag of Libya (1950-1969), which was red-black-green in three stripes, but horizontal(with the black stripe twice as wide as the other stripes). There was a white crescent and star on the black stripe. Source: The International Flag Book in Colour, C.F. Pedersen (1970) James Dignan, 25 September 1996 Two offshoots of this party are represented in the newly elected parliament, PPP-Parliamentarians and PPP-Sherpao. PPP-P won 71 of the 342 seats (25.8% of the vote) and is the largest single block in the National Assembly. PPP-Sherpao won two seats. The websites of both Benazir Bhutto's faction of the party and her brother's widow show identical flags, a red-black-green vertical tricolor with a white crescent and star on the black stripe. (I'm not quite clear on how these long-established factions relate to the offshoots elected to parliament, as Benazir herself is in exile and definitely persona non grata.) We show (below) a plain tricolor without the crescent and star, identifying it as the flag of the faction led by Benazir. I saw a number of the plain tricolors, especially before crossing the Indus River from Punjab into the Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP), as well as a few on the outskirts of Peshawar on which some kind of white logo but not the crescent and star had been applied to the black stripe. I'm forwarding the flag as seen on the party websites. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003 The latest photos I have (but months before Joe's trip) show the flag with a white horizontal sword in the lower part. Jaume Ollé, 31 January 2003 Might it have been an arrow? One of the PPP factions was using an arrow as a party symbol, although I did not see it on a flag. The unidentifiable logo I saw was clearly not a sword--it looked like an American football with an inscription below it.Joe McMillan, 1 February 2003

Pakistan Peoples Party - Benazir Bhutto's faction

image by Jorge Candeias Yesterday, in a news report on the nuclear tensions between India and Pakistan, I saw an unknown to me flag: a 1:2 vertical tricolour of red, black and green. It was being flown in a military parade. Any ideas? Jorge Candeias, 18 May 1998 It's the flag of the Pakistan People's Party, of which Benazir Bhutto is the leader. Flags of political parties throughout the sub-continent tend to be modified at the whim of the maker: crescents, stars, slogans, images of people, (usually the leader), etc., are all commonly displayed on them. Glen Robert-Grant Hodgins, 19 May 1998 A few days ago, television news covered the arrival back in Pakistan of Benazir Bhutto. A large rally was shown in one scene, with a lot of flags, mainly of two sorts. One of those was a variant on a flag shown above (Murtazi Bhutto's faction), with the white crescent and star on a red-black-green vertical tricolour. It had the addition, however, of script in white under the crescent and star. James Dignan, 22 October 2007 image by Eugene Ipavec, 28 December 2007At the funeral of Benazir Bhutto, the coffin was covered with the red-black-green tricolor flag of the Pakistan People's Party, but oddly with a crescent & star in the middle stripe as identified here as the flag of the PPP's "Murtazi Bhutto's faction." Benazir Bhutto's faction's flag used to lack the charge. I assume the party has reunited in the four years since? The coffin flag was in the longer proportions of the Benazir faction, and the crescent & star were rendered differently (thicker): Eugene Ipavec, 28 December 2007 image by Clay Moss, 28 December 2007 I have also seen a party flag variant(?) with an arrow that was prominently displayed on BBC. I saw two versions of this same flag. One was on BBC's website and the other was on BBC television. Clay Moss, 28 December 2007A recent Reuters news photo showed the PPP flag of red/black/green tricolor with crescent and star, but also what appears to be an arrow and Arabic script just below, all in the center black stripe. Is this a faction flag of the PPP and which one? Tom Carrier, 29 December 2007 A second flag was also in evidence - a France-like tricolour of red-white-blue, with script across the bottom in red and white, and three or four Roman/European letters vertically in red on the white stripe, "? P M A". James Dignan, 22 October 2007

Muslim League

The ruling party in Pakistan is currently the Muslim League. It's flag is a white crescent on a green field, (just like the Pakistani national flag, but without the white bar at the hoist); in fact, the Pakistani national flag was based upon the flag of the Muslim League, just as the Indian national flag was based upon that of the Indian National Congress. Glen Robert-Grant Hodgins, 19 May 1998 Parties of this name have come and gone since before independence. The current incarnation was the party of former Prime Ministers Junejo and Nawaz Sharif. It is now split into a number of factions, five of which won seats in the October election: PML-Quaid-i-Azam (69 seats, 25.7% of the vote), PML-Nawaz (14 seats, 9.4%), PML-Functional (4 seats, 1.1%), PML-Junejo (2 seats, 0.7%) and PML-Shahid Zia (1 seat, 0.3%). The flag of the PML is green with the white crescent and star--basically the national flag minus the white stripe at the hoist. This flag can also be seen at the website-in-exile of the Nawaz faction. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Jamiat e Islami

image by António Martins and Mario Fabretto Yesterday, the news was full of reports from demonstrations against Mrs Bhutto, now led by the party jam'at alislami. Its flag replaces the white stripe of the national flag by a light blue and a white stripe (ratio approx 2:1). Moreover, the crescent and star point towards the hoist. Perhaps, the orientation of the crescent reflects the orientation of the party (which, in this case, is considered to be a "fundamentalist" one). Harald Müller, 28 October 1996 In yesterday's paper Publico I saw a photo taken in Islamabad (a demonstrator holding a sign saying "CRUSH INDIA") with two or three flags on background: per bend azure over green, a bend argent. Does this ring a bell to someone? António Martins, 15 May 1998 That's the flag of the party Jamiat Al Islami. At least three versions are know, all in vertical blue (at hoist) and green at fly (1:4) and a narrow white stripe between the two bands. The differences are the following:

1) the first one has the crescent and star (like the Pakistan national flag) and below the shahada.

2) the second has only the crescent and star (reported by Harald Mueller, former list member, with the crescent pointing towards the hoist and slighty rotated to the bottom; but I saw it in TV with the crescent and star in normal position).

3) The third has only the shahada and no crescent and star.

Seems to me that the last one is the official version. The second one is the most frequently used by the people; the first one is a variant of the other two. Jaume Ollé, 17 May 1998 image by Jorge Hurtado The Party Jamât-e-Islami (Islamist party) flag was seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 The Jamaat-e-Islami is a very conservative Islamist party that is one of the two leading components of the MMA, the Islamist coalition. The MMA won 53 seats in the national assembly (11.3% of the vote) as well as control over the state assembly of NWFP. We have an image of one and describe several others on our party flag page. I saw this flag on at least 100 houses and commercial buildings between the Indus and Peshawar--green field with light blue and white vertical stripes at the hoist, and on the green field a crescent star opening toward the upper hoist (the crescent thinner and shallower than that on the national flag) and the shahada in white at the top. Also visible on the party website. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Jamiat Ulama'a e Islam

image by Santiago Dotor A poster was displayed in Quetta, Pakistan, showing this flag along with what appear to be variants of the Taliban flag (white with one or another variant of the shehada), displayed in Quetta, Pakistan. Al Kirsch, 13 October 2001 Some time ago I recorded a photo from the news of a demonstration in Sindh. The demonstrators hoisted a flag in the Catalan pattern (4 bars) white on dark (probably black or dark red). Many years ago, when Islamism didn't exist at the level of political organisations, I saw this flag many times on TV in new related to Pakistan, Sindh or Punjab (green, black or blue were the colors that I seemed to see). Currently the flag seems to be identified as an Islamist party flag, but why does it exist from many years ago? Can it be a regional flag? Probably regional flags exist in Pakistan. Some years ago, in my notes, and from other vexillologists, it seems that is has only three white bars (and four green). I saw a photo of Jaipur in Punjab with a similar flag (the flag is not totally visible, but could be three white bars on blue of three blue bars on white. Jaume Ollé, 30 August 1999 The faction of this even more hardline Islamist party led by Fezlur Rehman (and known by the ironic abbreviation JUI-F) is the other main component of the MMA coalition. The JUI flag, seen in the logo on its website http://www.juipak.org is black with four narrow white horizontal stripes. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Variants of this flag

image by Santiago Dotor During demonstrations in Peshawar, this flag was also seen in a square (1:1) format, almost certainly black (it could be mistaken with very-very dark green at first glance) and had four white horizontal stripes. The proportion of the white and black stripes was 2:3. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003 I have just seen a documentary on the "Talibanization" of Pakistan, and in it the Islamist MMA party was holding a rally, at which there was a variation of this flag with the black stripes twice the size of the white stripes. Nygdan, 9 January 2006

National Alliance Party

image by Joe McMillan A coalition of moderate secular parties which won 12 seats (4.6% of the vote) in the national assembly. Athttp://pakistanspace.tripod.com/1977.htm the flag of the Pakistan National Alliance, which seems to be the same group, is shown as green with nine white stars, 3 x 3, each star tilted about 30 degrees counterclockwise. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003 The nine stars flag was reported some years ago as the flag of IDA, Islamic Democratic Alliance. Jaume Ollé, 31 January 2003

Millat Party

image by Joe McMillan One of the component parties of the PNA. I saw this flag--divided lower hoist to upper fly, red over green, with the white crescent and star overall--on Pakistani television on 12 January and was able to identify it from http://www.millatparty.com Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Khaksar Tehrik

This is the flag of Khaksar Tehrik, a political party in Pakistan. The English translation of "Tehrik" is "Movement". Seehttp://allama-mashriqi.8m.com/ for information on Allama Mashriqi -scholar and founder of the Khaksar movement Office of Allama Mashriqi, 29 Nov 1999

Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf

image by Joe McMillan A small party favoring "a model moderate Islamic republic, political freedom, economic opportunity, and social justice," but best known for being led by the great cricket player Imran Khan, who won the party's only parliamentary seat (the party got 0.8% of the vote). The flag can be seen at http://insaf.org.pk: horizontally green over red with a white crescent and star overall. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Pakistan Awami Tehreek

image by Joe McMillan A rather Iranian-looking flag for a party with 1 parliamentary seat and 0.7% of the vote. Despite its small support base, I saw several of these flags on the outskirts of Peshawar: horizontal tricolor, red-white-green. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Party El Jihad Tanzim

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, this flag is fairly new as far as I know, though I have seen the flag on TV. Can anybody identify the inscription? Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 The inscription is Akbar = The greatest. Dov Gutterman, 16 October 2001 I would like to contest your translation of Party Al-Jihad Tanzim. It could be read Akbar, but I believe it to be Al-Jihad. Though it could very well have been written this ambiguous way to convey both meanings. As with the following pages which do indeed say al-Jihad, a small 'h' (chhoTii he) is occasionally used instead of the big 'H' (baRii He) in Urdu. If this were pure Arabic, you would be uncontested. But in my opinion, this is a Nastaliq (Perso=Arabic style of the Arabic Alphabet) rendering of Al-Jihad. Kurt Singer, 24 February 2005

Party Sipâh-e-Sâhaba

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, several variants are known. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 This flag and variants was seen in various reports in 2001, and is more fully described on our page on Party Sipâh-e-Sâhaba.

Party Arkat el Mujahideen

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, this flag is fairly new as far as I know. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 I believe the inscription is 'the jihad'. Santiago Dotor, 16 October 2001 On ABC Television last night, there was a piece on Pakistanis who've gone to fight with the Taliban in Afghanistan. At one point, there was a brief shot of a billboard in Pakistan about those who've fought. The camera focused on a flag depicted on the bottom left (the "signature" area) of the sign (that is, a small picture of a flying flag on a pole, not a real flag). The flag was white, with two green stripes running across it- rather than five stripes, white-green-white-green-white, it seemed to be two thick stripes in the center of the flag. In the center of the flag, covering the stripes (they weren't visible under it) was a black and white globe, shown as a circle/sphere with latitude and longitude marked (no continents). Written on the globe was an Arabic (or Urdu/Pashto?) word or two, but the camera moved away before I could make it out. Nathan Lamm, 5 December 2001

Party Jihad

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, the Party Jihad, which advocates holy war in Kashmir. This is a fairly new flag as far as I know. I believe the inscription is 'jihad'. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001

Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM)

image by Jarig Bakker This party flag can be seen at http://www.mqm.com/ Dov Gutterman, 15 Dec 1999 The MQM was founded in 1981 as "Muhajir Quami Mahaz" (Muhajir National Movement), and was mainly concerned with the rights of post-partition Urdu-speaking migrants from India to Pakistan, who it would like to see recognized as constituting a "fifth nationality". In 1987 the party won a majority of seats in Karachi, and, with 13 seats, became the third biggest party in the National Assembly in 1988. In 1993 the party split in three groups: - The "official" MQM - MQM-Altaf, led by Altaf Husain. resident in London - MQM-Haqiqi, led by Afaq Ahmed It seems that the MQM-Altaf became the dominant party under the name Muttahida Quami Movement. In 1999 the Pakistani government launched a secretive operation against the MQM, which cost the lives of several prominent party-members, which in its turn caused demonstrations in Karachi Source: Political Handbook of the World, 1997 Fischer Weltalmanach 2001 Jarig Bakker, 17 September 2001 The MQM movement applied to become a member of the UNPO some years ago. They are from the Sind minority living in the Southern part of Pakistan. Pacer Prince, 27 September 2001 Muttahida Quami Movement (formerly Mohajir Quami Movement) (MQM) - The MQM is a mainly Karachi-based party that caters to the interests of Mohajirs, the Muslims who emigrated from India to Pakistan at partition in 1947 and their descendants. It won 13 seats (3.1% of the vote) in the new national assembly. The flag, as shown at http://www.mqm.orgconsists of vertical stripes of red and dark green at the hoist and a large white field in the fly. The green stripe is sometimes shown equal to the red one and sometimes slightly narrower. Click here for an equal width red/green stripe version. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA)

I haven't seen any of these in town [Islamabad], but at the website of the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) is the MMA party flag: white with a green crescent open toward the upper hoist, with the Arabic words Allahu akbar (God is great) inscribed within the horns of the crescent and the party name in Urdu script at the bottom. This is the union of Islamist parties that got so much attention for its strong showing in the recent elections, including gaining control of the provincial legislature in the heavily Pashtun Northwest Frontier Province. Joe McMillan, 12 January 2003

Pushtunkuwa Milli Awami Party (Pushtunkuwa National Awami Party)

image by Santiago Dotor Yesterday I saw a TV report about the arrest of Maulana Fazlur Rehman, leader of the pro-Taleban Pakistani party Jamiat Ulema Islam. Even though most images showing him attending demonstrations showed the black flag with white stripes we have already discussed, another demonstration showed several people waving large flags unlike any other of the Pakistani UFEs we have discussed. These were vertical tricolours of red-white-green, with a red star in the centre pointing downwards. The shade of red appeared slightly orange on my monitor. I guess you are thinking I saved my image upside down by some mistake. Well, I am afraid I didn't! I did see several flags, all of them with the red stripe by the *hoist*, and those in which I could see the central star, this was pointing *down*. Santiago Dotor, 8 October 2001 BBC TV also had similar footage. I agree that the red looked orange. My impression - and it's only an impression - was that some stars were pointing downwards, some sideways. Difficult to tell in a couple of seconds and without the video running! I wasn't clear from the commentary who the demonstrators were - the former king of Afghanistan was also mentioned. André Coutanche, 8 October 2001 This red-white-green tricolour with red upside-down star is that of the Pushtunkuwa National Awami Party. The star is correct as in the image (upside down), even if there might be variations as in Santiago Tazón's image below. It has been reported onYahoo Daily News, wrongly attributed to the Jamuhari Watan Party, unless this party uses the same flag. The caption reads: "Pakistani men wave their party's flag and hold up banners during a rally of the JWP (Jamuhari Watan Party, a leftist, nationalist, pro-democracy party) in central Quetta October 7, 2001. Thousands of Pakistan's Pasthun-speaking people heard their leader, Mehmoud Khan Achakzai, call for an independent, democratic government in Afghanistan. The Achakzai leftist Nationalist party is opposed to any U.S. military intervention, saying a democratic Afghanistan would root out foreign terrorists like Osama Bin Laden. REUTERS/Jerry Lampen" Jaume Ollé, 12 October 2001

Variant of the flag

image by Santiago Tazón I saw this flag in the TV news, today. A Spanish TV channel was broadcasting a report about the Islamic movements of Pakistan, they mixed several images and in one of them appeared several flags like the image that I made. Three vertical stripes, green, white and red; all of them same width. In the center of the white stripe a red five points star. I don't know what group uses it. Santiago Tazón, 7 October 2001

Islamic Students Organization of Pakistan (Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba)

image by Juan Manuel Gabino Villascán According to the "El Universal" (Mexican newspaper) this is the flag of the "Islamic Students Organization of Pakistan". I can just identify the text that says "Pakistan" at the end of the sentence, may be it is the organization's name. The orange text says: "Allahu Akbar" (God is almighty). Juan Manuel Gabino Villascán, 13 October 2001 The flag of Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba is green at the hoist, narrow red vertical stripe, last half (more or less) light blue with white crescent and star opening to fly. Whatever website I got this from says the organization was formed in 1947. "Jamiat" means something like "union," I believe, so this would be something like "Islamic Union of Students." A similar flag is at http://www.jamiat.org/about/flag.asp. The colors are the same, but the green and red bands in the hoist are of about equal width, the crescent and star face the hoist, the crescent is thinner and shallower, and the Takbir (Allahu akbar) appears in red between the crescent and the star. The name on this site is given as Islami Jamiat Talibat Pakistan, which should mean Islamic Union of Students of Pakistan. Sounds like the same group, but the site says it was founded in 1969, so apparently not--maybe an offshoot. Joe McMillan, 2 February 2003 Mr. Juan Manuel Gabino Villascan IS correct on Allaahu Akbar, however the text on the flag says 'Bagistan' NOT 'Pakistan'! Kurt Singer, 24 February 2005 by Santiago Dotor I saw on Polish TG a flag hoisted during an anti-American demonstration in Pakistan (most probably in Peshawar). This flag does not seem to be any of Pakistani political movements' flags, nor it is the Taliban movement's flag, as far as the outside world knows anything about Taliban regime. It's probable that it's to connected to some political and religious movement involving Taliban and Pakistani Moslems. Bartek Wojciechowski, 22 September 2001 There is something written under the crescent. Fortunately, in a TV news coverage this evening a slightly enlarged version of the flag appeared. I took a TV screenshot of it and analyzed the content of the inscription. Please note it has a rather low degree of accuracy, as: - the shooting quality was poor - transposing images via TV-MAC-PC gives shabby effects - the flag appeared for mere 2.05 sec - the flag was waving - the flag (and letters) was actually inverted - the flag appeared in the very corner of the TV screen - I don't speak Urdu. I have some knowledge of Persian (written in Arabic script as well) though and I tried to put down the letters: I don't understand the first word (words?), but the middle one and the last one go "...Talib Pakistan". That's quite understandable, isn't it? I hope somebody with good command of Urdu or Arabic, maybe will able to correct my version and say what it means. Bartek Wojciechowski, 26 September 2001 This is the flag of islami jamiat e talabe (Islamic Students Organization). Their official website is at: www.jamiat.org.pk Dr. Zafar Iqbal, 22 April 2006

Hizb ut Tahrir

image by Joe McMillan Black with the shahada. Given the source, undoubtedly a radical Islamist group, but a minor political party. The transliteration of the name is not typical of Urdu, so this may actually be an Arab group of some kind, but the source is in Pakistan. Source:http://www.khilafah.com.pk Joe McMillan, 2 February 2003

Pakistan Christian Congress

image by Joe McMillan Vertical tricolor, red-yellow-green, with a red Latin cross on the center. Source: http://pakistanchristiancongress.com Joe McMillan, 2 February 2002

Sindh National Front

image by Joe McMillan Seven horizontal stripes, white and red. The party says it seeks provincial autonomy on the United States, Swiss, and Canadian model. Source: http://snfsindh.netfirms.com/snf.htm Joe McMillan, 2 February 2002

Gilgit-Baltistan United Movement (GBUM)

image by Chrystian Kretowicz, 29 March 2008 One of the most prominent political movements in present-day Northern Areas of Pakistan (known also as Boloristan, Dardistan, Karakuram, Balawaristan, etc). It advocates a far-reaching autonomy for Gilgit-Baltistan State within Pakistan with the status similar to that of Azad Kashmir. The other main political movements there: Balawaristan National Front and Karakuram National Movement, demand outright independence for the state under their name. The image of the flag of Gilgit-Baltistan United Movement was obtained from the Chairman of GBUM, Mr.Manzoor Hussain Parwana. Chrystian Kretowicz, 29 March 2008

Hezb-e-Mughalstan (Mughalstan Party)

image from http://www.dalitstan.org/mughalstan/ located by Dov Gutterman, 26 May 2002 Hezb-e-Mughalastan stands for independence and reunification of Muslim areas of Pakistan, north India and neighbouring regions. This is a fictional creation, as is most of the other organizations mentioned on www.dalitstan.org. J.A. Sommansson, 23 Febraury 2005

Pasban

image by Ian MacDonald, 18 May 2006 An image of this flag was provided by an anonymous site visitor. It can be seen in use at the Pasban home page. [Ed.] Pasban ( The Defenders), is a Pakistani political movement that aims to uproot what it sees as the current oppressive system and to establish a welfare state in Pakistan. Pasban's president is Altaf Shakoor, born in Karachi in 1959. An engineer by education and trader by profession, Shakoor was president of the students' union at NED University of Engineering and Technology in 1981–1982. The flag consists of a red field with a wide white stripe along the hoist, and a large white disk bearing a red star extending to the edges of the disk. Written verically down the hoist side of the white stripe is the word PASBAN. Ian MacDonald, 18 May 2006

All Pakistan Minorities Alliance

image by Ian MacDonald, 1 January 2013 The All Pakistan Minorities Alliance flag is red, white and blue, sometimes with the letters APMA written vertically down the white stripe. There’s a photo in http://liam-theactivist.blogspot.com.es/2011/03/blasphemy-and-death-in-pakistan.html. Other photos in http://zeenews.india.com/photogallery/day-in-pics-23rd-september_2526.html?pagenumber=1 andhttp://news.kuwaittimes.net/2012/09/23/pakistan-govt-rejects-filmmaker-bounty-fresh-rallies-held-across-pakistan, with the red at hoist and no letters. Jaume Olle, 1 December 2012

#PPP#Pakistani#Pakistan People#Pakistan History#Pakistan#Flags of Pakistan Political Parties#Flags#December 2007#Bhutto#Benazir Bhutto#Assassination of Benazir Bhutto

0 notes

Text

Flags of Pakistan Political Parties

Pakistan Peoples Party - Murtazi Bhutto's faction

image by Joe McMillan The Pakistani flag is derived from a party flag. The ruling PPP of Benazir Bhutto uses a flag which incorporates the basic flag design (white inclined crescent and star on dark green), the same is true for the separatist faction of the PPP let by Mrs Bhutto's brother. Both parties use vertical tricolors. Harald Müller, 28 October 1996 Yesterday I saw on the news a report on the murder of Pakistani politician Murtazi Bhutto, brother of prime minister Benazir Bhutto, and one of the strongest oppositions leaders. There was a short scene from archives of one of his speeches a few days ago, where he sat at the table on which there was a flag I haven't seen before. I suppose that it is the flag of his party (which I don't remember what it is called). The flag was a vertical tricolour of red (at the hoist) - black - green with a white crescent and star very similar in shape to the one on Pakistani national flag. The flag looks quite dark with this choice of colours, but quite effective if you ask me. Željko Heimer, 22 September 1996 This would appear very similar to an old flag of Libya (1950-1969), which was red-black-green in three stripes, but horizontal(with the black stripe twice as wide as the other stripes). There was a white crescent and star on the black stripe. Source: The International Flag Book in Colour, C.F. Pedersen (1970) James Dignan, 25 September 1996 Two offshoots of this party are represented in the newly elected parliament, PPP-Parliamentarians and PPP-Sherpao. PPP-P won 71 of the 342 seats (25.8% of the vote) and is the largest single block in the National Assembly. PPP-Sherpao won two seats. The websites of both Benazir Bhutto's faction of the party and her brother's widow show identical flags, a red-black-green vertical tricolor with a white crescent and star on the black stripe. (I'm not quite clear on how these long-established factions relate to the offshoots elected to parliament, as Benazir herself is in exile and definitely persona non grata.) We show (below) a plain tricolor without the crescent and star, identifying it as the flag of the faction led by Benazir. I saw a number of the plain tricolors, especially before crossing the Indus River from Punjab into the Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP), as well as a few on the outskirts of Peshawar on which some kind of white logo but not the crescent and star had been applied to the black stripe. I'm forwarding the flag as seen on the party websites. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003 The latest photos I have (but months before Joe's trip) show the flag with a white horizontal sword in the lower part. Jaume Ollé, 31 January 2003 Might it have been an arrow? One of the PPP factions was using an arrow as a party symbol, although I did not see it on a flag. The unidentifiable logo I saw was clearly not a sword--it looked like an American football with an inscription below it.Joe McMillan, 1 February 2003

Pakistan Peoples Party - Benazir Bhutto's faction

image by Jorge Candeias Yesterday, in a news report on the nuclear tensions between India and Pakistan, I saw an unknown to me flag: a 1:2 vertical tricolour of red, black and green. It was being flown in a military parade. Any ideas? Jorge Candeias, 18 May 1998 It's the flag of the Pakistan People's Party, of which Benazir Bhutto is the leader. Flags of political parties throughout the sub-continent tend to be modified at the whim of the maker: crescents, stars, slogans, images of people, (usually the leader), etc., are all commonly displayed on them. Glen Robert-Grant Hodgins, 19 May 1998 A few days ago, television news covered the arrival back in Pakistan of Benazir Bhutto. A large rally was shown in one scene, with a lot of flags, mainly of two sorts. One of those was a variant on a flag shown above (Murtazi Bhutto's faction), with the white crescent and star on a red-black-green vertical tricolour. It had the addition, however, of script in white under the crescent and star. James Dignan, 22 October 2007 image by Eugene Ipavec, 28 December 2007At the funeral of Benazir Bhutto, the coffin was covered with the red-black-green tricolor flag of the Pakistan People's Party, but oddly with a crescent & star in the middle stripe as identified here as the flag of the PPP's "Murtazi Bhutto's faction." Benazir Bhutto's faction's flag used to lack the charge. I assume the party has reunited in the four years since? The coffin flag was in the longer proportions of the Benazir faction, and the crescent & star were rendered differently (thicker): Eugene Ipavec, 28 December 2007 image by Clay Moss, 28 December 2007 I have also seen a party flag variant(?) with an arrow that was prominently displayed on BBC. I saw two versions of this same flag. One was on BBC's website and the other was on BBC television. Clay Moss, 28 December 2007A recent Reuters news photo showed the PPP flag of red/black/green tricolor with crescent and star, but also what appears to be an arrow and Arabic script just below, all in the center black stripe. Is this a faction flag of the PPP and which one? Tom Carrier, 29 December 2007 A second flag was also in evidence - a France-like tricolour of red-white-blue, with script across the bottom in red and white, and three or four Roman/European letters vertically in red on the white stripe, "? P M A". James Dignan, 22 October 2007

Muslim League

The ruling party in Pakistan is currently the Muslim League. It's flag is a white crescent on a green field, (just like the Pakistani national flag, but without the white bar at the hoist); in fact, the Pakistani national flag was based upon the flag of the Muslim League, just as the Indian national flag was based upon that of the Indian National Congress. Glen Robert-Grant Hodgins, 19 May 1998 Parties of this name have come and gone since before independence. The current incarnation was the party of former Prime Ministers Junejo and Nawaz Sharif. It is now split into a number of factions, five of which won seats in the October election: PML-Quaid-i-Azam (69 seats, 25.7% of the vote), PML-Nawaz (14 seats, 9.4%), PML-Functional (4 seats, 1.1%), PML-Junejo (2 seats, 0.7%) and PML-Shahid Zia (1 seat, 0.3%). The flag of the PML is green with the white crescent and star--basically the national flag minus the white stripe at the hoist. This flag can also be seen at the website-in-exile of the Nawaz faction. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Jamiat e Islami

image by António Martins and Mario Fabretto Yesterday, the news was full of reports from demonstrations against Mrs Bhutto, now led by the party jam'at alislami. Its flag replaces the white stripe of the national flag by a light blue and a white stripe (ratio approx 2:1). Moreover, the crescent and star point towards the hoist. Perhaps, the orientation of the crescent reflects the orientation of the party (which, in this case, is considered to be a "fundamentalist" one). Harald Müller, 28 October 1996 In yesterday's paper Publico I saw a photo taken in Islamabad (a demonstrator holding a sign saying "CRUSH INDIA") with two or three flags on background: per bend azure over green, a bend argent. Does this ring a bell to someone? António Martins, 15 May 1998 That's the flag of the party Jamiat Al Islami. At least three versions are know, all in vertical blue (at hoist) and green at fly (1:4) and a narrow white stripe between the two bands. The differences are the following:

1) the first one has the crescent and star (like the Pakistan national flag) and below the shahada.

2) the second has only the crescent and star (reported by Harald Mueller, former list member, with the crescent pointing towards the hoist and slighty rotated to the bottom; but I saw it in TV with the crescent and star in normal position).

3) The third has only the shahada and no crescent and star.

Seems to me that the last one is the official version. The second one is the most frequently used by the people; the first one is a variant of the other two. Jaume Ollé, 17 May 1998 image by Jorge Hurtado The Party Jamât-e-Islami (Islamist party) flag was seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 The Jamaat-e-Islami is a very conservative Islamist party that is one of the two leading components of the MMA, the Islamist coalition. The MMA won 53 seats in the national assembly (11.3% of the vote) as well as control over the state assembly of NWFP. We have an image of one and describe several others on our party flag page. I saw this flag on at least 100 houses and commercial buildings between the Indus and Peshawar--green field with light blue and white vertical stripes at the hoist, and on the green field a crescent star opening toward the upper hoist (the crescent thinner and shallower than that on the national flag) and the shahada in white at the top. Also visible on the party website. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Jamiat Ulama'a e Islam

image by Santiago Dotor A poster was displayed in Quetta, Pakistan, showing this flag along with what appear to be variants of the Taliban flag (white with one or another variant of the shehada), displayed in Quetta, Pakistan. Al Kirsch, 13 October 2001 Some time ago I recorded a photo from the news of a demonstration in Sindh. The demonstrators hoisted a flag in the Catalan pattern (4 bars) white on dark (probably black or dark red). Many years ago, when Islamism didn't exist at the level of political organisations, I saw this flag many times on TV in new related to Pakistan, Sindh or Punjab (green, black or blue were the colors that I seemed to see). Currently the flag seems to be identified as an Islamist party flag, but why does it exist from many years ago? Can it be a regional flag? Probably regional flags exist in Pakistan. Some years ago, in my notes, and from other vexillologists, it seems that is has only three white bars (and four green). I saw a photo of Jaipur in Punjab with a similar flag (the flag is not totally visible, but could be three white bars on blue of three blue bars on white. Jaume Ollé, 30 August 1999 The faction of this even more hardline Islamist party led by Fezlur Rehman (and known by the ironic abbreviation JUI-F) is the other main component of the MMA coalition. The JUI flag, seen in the logo on its website http://www.juipak.org is black with four narrow white horizontal stripes. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Variants of this flag

image by Santiago Dotor During demonstrations in Peshawar, this flag was also seen in a square (1:1) format, almost certainly black (it could be mistaken with very-very dark green at first glance) and had four white horizontal stripes. The proportion of the white and black stripes was 2:3. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003 I have just seen a documentary on the "Talibanization" of Pakistan, and in it the Islamist MMA party was holding a rally, at which there was a variation of this flag with the black stripes twice the size of the white stripes. Nygdan, 9 January 2006

National Alliance Party

image by Joe McMillan A coalition of moderate secular parties which won 12 seats (4.6% of the vote) in the national assembly. Athttp://pakistanspace.tripod.com/1977.htm the flag of the Pakistan National Alliance, which seems to be the same group, is shown as green with nine white stars, 3 x 3, each star tilted about 30 degrees counterclockwise. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003 The nine stars flag was reported some years ago as the flag of IDA, Islamic Democratic Alliance. Jaume Ollé, 31 January 2003

Millat Party

image by Joe McMillan One of the component parties of the PNA. I saw this flag--divided lower hoist to upper fly, red over green, with the white crescent and star overall--on Pakistani television on 12 January and was able to identify it from http://www.millatparty.com Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Khaksar Tehrik

This is the flag of Khaksar Tehrik, a political party in Pakistan. The English translation of "Tehrik" is "Movement". Seehttp://allama-mashriqi.8m.com/ for information on Allama Mashriqi -scholar and founder of the Khaksar movement Office of Allama Mashriqi, 29 Nov 1999

Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf

image by Joe McMillan A small party favoring "a model moderate Islamic republic, political freedom, economic opportunity, and social justice," but best known for being led by the great cricket player Imran Khan, who won the party's only parliamentary seat (the party got 0.8% of the vote). The flag can be seen at http://insaf.org.pk: horizontally green over red with a white crescent and star overall. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Pakistan Awami Tehreek

image by Joe McMillan A rather Iranian-looking flag for a party with 1 parliamentary seat and 0.7% of the vote. Despite its small support base, I saw several of these flags on the outskirts of Peshawar: horizontal tricolor, red-white-green. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Party El Jihad Tanzim

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, this flag is fairly new as far as I know, though I have seen the flag on TV. Can anybody identify the inscription? Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 The inscription is Akbar = The greatest. Dov Gutterman, 16 October 2001 I would like to contest your translation of Party Al-Jihad Tanzim. It could be read Akbar, but I believe it to be Al-Jihad. Though it could very well have been written this ambiguous way to convey both meanings. As with the following pages which do indeed say al-Jihad, a small 'h' (chhoTii he) is occasionally used instead of the big 'H' (baRii He) in Urdu. If this were pure Arabic, you would be uncontested. But in my opinion, this is a Nastaliq (Perso=Arabic style of the Arabic Alphabet) rendering of Al-Jihad. Kurt Singer, 24 February 2005

Party Sipâh-e-Sâhaba

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, several variants are known. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 This flag and variants was seen in various reports in 2001, and is more fully described on our page on Party Sipâh-e-Sâhaba.

Party Arkat el Mujahideen

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, this flag is fairly new as far as I know. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001 I believe the inscription is 'the jihad'. Santiago Dotor, 16 October 2001 On ABC Television last night, there was a piece on Pakistanis who've gone to fight with the Taliban in Afghanistan. At one point, there was a brief shot of a billboard in Pakistan about those who've fought. The camera focused on a flag depicted on the bottom left (the "signature" area) of the sign (that is, a small picture of a flying flag on a pole, not a real flag). The flag was white, with two green stripes running across it- rather than five stripes, white-green-white-green-white, it seemed to be two thick stripes in the center of the flag. In the center of the flag, covering the stripes (they weren't visible under it) was a black and white globe, shown as a circle/sphere with latitude and longitude marked (no continents). Written on the globe was an Arabic (or Urdu/Pashto?) word or two, but the camera moved away before I could make it out. Nathan Lamm, 5 December 2001

Party Jihad

image by Jorge Hurtado Seen on a visit to Pakistan from February to March 2001, the Party Jihad, which advocates holy war in Kashmir. This is a fairly new flag as far as I know. I believe the inscription is 'jihad'. Michel Lupant, published in Gaceta de Banderas, October 2001

Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM)

image by Jarig Bakker This party flag can be seen at http://www.mqm.com/ Dov Gutterman, 15 Dec 1999 The MQM was founded in 1981 as "Muhajir Quami Mahaz" (Muhajir National Movement), and was mainly concerned with the rights of post-partition Urdu-speaking migrants from India to Pakistan, who it would like to see recognized as constituting a "fifth nationality". In 1987 the party won a majority of seats in Karachi, and, with 13 seats, became the third biggest party in the National Assembly in 1988. In 1993 the party split in three groups: - The "official" MQM - MQM-Altaf, led by Altaf Husain. resident in London - MQM-Haqiqi, led by Afaq Ahmed It seems that the MQM-Altaf became the dominant party under the name Muttahida Quami Movement. In 1999 the Pakistani government launched a secretive operation against the MQM, which cost the lives of several prominent party-members, which in its turn caused demonstrations in Karachi Source: Political Handbook of the World, 1997 Fischer Weltalmanach 2001 Jarig Bakker, 17 September 2001 The MQM movement applied to become a member of the UNPO some years ago. They are from the Sind minority living in the Southern part of Pakistan. Pacer Prince, 27 September 2001 Muttahida Quami Movement (formerly Mohajir Quami Movement) (MQM) - The MQM is a mainly Karachi-based party that caters to the interests of Mohajirs, the Muslims who emigrated from India to Pakistan at partition in 1947 and their descendants. It won 13 seats (3.1% of the vote) in the new national assembly. The flag, as shown at http://www.mqm.orgconsists of vertical stripes of red and dark green at the hoist and a large white field in the fly. The green stripe is sometimes shown equal to the red one and sometimes slightly narrower. Click here for an equal width red/green stripe version. Joe McMillan, 30 January 2003

Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA)

I haven't seen any of these in town [Islamabad], but at the website of the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) is the MMA party flag: white with a green crescent open toward the upper hoist, with the Arabic words Allahu akbar (God is great) inscribed within the horns of the crescent and the party name in Urdu script at the bottom. This is the union of Islamist parties that got so much attention for its strong showing in the recent elections, including gaining control of the provincial legislature in the heavily Pashtun Northwest Frontier Province. Joe McMillan, 12 January 2003

Pushtunkuwa Milli Awami Party (Pushtunkuwa National Awami Party)

image by Santiago Dotor Yesterday I saw a TV report about the arrest of Maulana Fazlur Rehman, leader of the pro-Taleban Pakistani party Jamiat Ulema Islam. Even though most images showing him attending demonstrations showed the black flag with white stripes we have already discussed, another demonstration showed several people waving large flags unlike any other of the Pakistani UFEs we have discussed. These were vertical tricolours of red-white-green, with a red star in the centre pointing downwards. The shade of red appeared slightly orange on my monitor. I guess you are thinking I saved my image upside down by some mistake. Well, I am afraid I didn't! I did see several flags, all of them with the red stripe by the *hoist*, and those in which I could see the central star, this was pointing *down*. Santiago Dotor, 8 October 2001 BBC TV also had similar footage. I agree that the red looked orange. My impression - and it's only an impression - was that some stars were pointing downwards, some sideways. Difficult to tell in a couple of seconds and without the video running! I wasn't clear from the commentary who the demonstrators were - the former king of Afghanistan was also mentioned. André Coutanche, 8 October 2001 This red-white-green tricolour with red upside-down star is that of the Pushtunkuwa National Awami Party. The star is correct as in the image (upside down), even if there might be variations as in Santiago Tazón's image below. It has been reported onYahoo Daily News, wrongly attributed to the Jamuhari Watan Party, unless this party uses the same flag. The caption reads: "Pakistani men wave their party's flag and hold up banners during a rally of the JWP (Jamuhari Watan Party, a leftist, nationalist, pro-democracy party) in central Quetta October 7, 2001. Thousands of Pakistan's Pasthun-speaking people heard their leader, Mehmoud Khan Achakzai, call for an independent, democratic government in Afghanistan. The Achakzai leftist Nationalist party is opposed to any U.S. military intervention, saying a democratic Afghanistan would root out foreign terrorists like Osama Bin Laden. REUTERS/Jerry Lampen" Jaume Ollé, 12 October 2001

Variant of the flag

image by Santiago Tazón I saw this flag in the TV news, today. A Spanish TV channel was broadcasting a report about the Islamic movements of Pakistan, they mixed several images and in one of them appeared several flags like the image that I made. Three vertical stripes, green, white and red; all of them same width. In the center of the white stripe a red five points star. I don't know what group uses it. Santiago Tazón, 7 October 2001

Islamic Students Organization of Pakistan (Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba)

image by Juan Manuel Gabino Villascán According to the "El Universal" (Mexican newspaper) this is the flag of the "Islamic Students Organization of Pakistan". I can just identify the text that says "Pakistan" at the end of the sentence, may be it is the organization's name. The orange text says: "Allahu Akbar" (God is almighty). Juan Manuel Gabino Villascán, 13 October 2001 The flag of Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba is green at the hoist, narrow red vertical stripe, last half (more or less) light blue with white crescent and star opening to fly. Whatever website I got this from says the organization was formed in 1947. "Jamiat" means something like "union," I believe, so this would be something like "Islamic Union of Students." A similar flag is at http://www.jamiat.org/about/flag.asp. The colors are the same, but the green and red bands in the hoist are of about equal width, the crescent and star face the hoist, the crescent is thinner and shallower, and the Takbir (Allahu akbar) appears in red between the crescent and the star. The name on this site is given as Islami Jamiat Talibat Pakistan, which should mean Islamic Union of Students of Pakistan. Sounds like the same group, but the site says it was founded in 1969, so apparently not--maybe an offshoot. Joe McMillan, 2 February 2003 Mr. Juan Manuel Gabino Villascan IS correct on Allaahu Akbar, however the text on the flag says 'Bagistan' NOT 'Pakistan'! Kurt Singer, 24 February 2005 by Santiago Dotor I saw on Polish TG a flag hoisted during an anti-American demonstration in Pakistan (most probably in Peshawar). This flag does not seem to be any of Pakistani political movements' flags, nor it is the Taliban movement's flag, as far as the outside world knows anything about Taliban regime. It's probable that it's to connected to some political and religious movement involving Taliban and Pakistani Moslems. Bartek Wojciechowski, 22 September 2001 There is something written under the crescent. Fortunately, in a TV news coverage this evening a slightly enlarged version of the flag appeared. I took a TV screenshot of it and analyzed the content of the inscription. Please note it has a rather low degree of accuracy, as: - the shooting quality was poor - transposing images via TV-MAC-PC gives shabby effects - the flag appeared for mere 2.05 sec - the flag was waving - the flag (and letters) was actually inverted - the flag appeared in the very corner of the TV screen - I don't speak Urdu. I have some knowledge of Persian (written in Arabic script as well) though and I tried to put down the letters: I don't understand the first word (words?), but the middle one and the last one go "...Talib Pakistan". That's quite understandable, isn't it? I hope somebody with good command of Urdu or Arabic, maybe will able to correct my version and say what it means. Bartek Wojciechowski, 26 September 2001 This is the flag of islami jamiat e talabe (Islamic Students Organization). Their official website is at: www.jamiat.org.pk Dr. Zafar Iqbal, 22 April 2006

Hizb ut Tahrir

image by Joe McMillan Black with the shahada. Given the source, undoubtedly a radical Islamist group, but a minor political party. The transliteration of the name is not typical of Urdu, so this may actually be an Arab group of some kind, but the source is in Pakistan. Source:http://www.khilafah.com.pk Joe McMillan, 2 February 2003

Pakistan Christian Congress

image by Joe McMillan Vertical tricolor, red-yellow-green, with a red Latin cross on the center. Source: http://pakistanchristiancongress.com Joe McMillan, 2 February 2002

Sindh National Front

image by Joe McMillan Seven horizontal stripes, white and red. The party says it seeks provincial autonomy on the United States, Swiss, and Canadian model. Source: http://snfsindh.netfirms.com/snf.htm Joe McMillan, 2 February 2002

Gilgit-Baltistan United Movement (GBUM)

image by Chrystian Kretowicz, 29 March 2008 One of the most prominent political movements in present-day Northern Areas of Pakistan (known also as Boloristan, Dardistan, Karakuram, Balawaristan, etc). It advocates a far-reaching autonomy for Gilgit-Baltistan State within Pakistan with the status similar to that of Azad Kashmir. The other main political movements there: Balawaristan National Front and Karakuram National Movement, demand outright independence for the state under their name. The image of the flag of Gilgit-Baltistan United Movement was obtained from the Chairman of GBUM, Mr.Manzoor Hussain Parwana. Chrystian Kretowicz, 29 March 2008

Hezb-e-Mughalstan (Mughalstan Party)

image from http://www.dalitstan.org/mughalstan/ located by Dov Gutterman, 26 May 2002 Hezb-e-Mughalastan stands for independence and reunification of Muslim areas of Pakistan, north India and neighbouring regions. This is a fictional creation, as is most of the other organizations mentioned on www.dalitstan.org. J.A. Sommansson, 23 Febraury 2005

Pasban

image by Ian MacDonald, 18 May 2006 An image of this flag was provided by an anonymous site visitor. It can be seen in use at the Pasban home page. [Ed.] Pasban ( The Defenders), is a Pakistani political movement that aims to uproot what it sees as the current oppressive system and to establish a welfare state in Pakistan. Pasban's president is Altaf Shakoor, born in Karachi in 1959. An engineer by education and trader by profession, Shakoor was president of the students' union at NED University of Engineering and Technology in 1981–1982. The flag consists of a red field with a wide white stripe along the hoist, and a large white disk bearing a red star extending to the edges of the disk. Written verically down the hoist side of the white stripe is the word PASBAN. Ian MacDonald, 18 May 2006

All Pakistan Minorities Alliance

image by Ian MacDonald, 1 January 2013 The All Pakistan Minorities Alliance flag is red, white and blue, sometimes with the letters APMA written vertically down the white stripe. There’s a photo in http://liam-theactivist.blogspot.com.es/2011/03/blasphemy-and-death-in-pakistan.html. Other photos in http://zeenews.india.com/photogallery/day-in-pics-23rd-september_2526.html?pagenumber=1 andhttp://news.kuwaittimes.net/2012/09/23/pakistan-govt-rejects-filmmaker-bounty-fresh-rallies-held-across-pakistan, with the red at hoist and no letters. Jaume Olle, 1 December 2012

#PPP#Pakistani#Pakistan People#Pakistan History#Pakistan#Flags of Pakistan Political Parties#Flags#December 2007#Bhutto#Benazir Bhutto#Assassination of Benazir Bhutto

0 notes

Text

Geführte Wohnmobilreisen USA, Kanada, Neuseeland und Hausboot Touren in Irland, Schottland, Frankreich und Deutschland mit ADAC-Reisen Frankfurt/Main und DERTOUR

With your New Zealand motorhome, you have numerous options for making your round trip. However, always pay attention to where you are staying, because you are not allowed to stand everywhere with the motorhome of your choice - our New Zealand travel experts are at your side with advice and action. Renting a motorhome or camper through Motorhome Republic is a breeze. Are you looking for a cheap provider for a motorhome in New Zealand?

Meet the locals by motorhome?

We as a travel specialist for New Zealand will be happy to help you make this dream come true - but without a motorhome. We do it differently from other travel agencies because we know from our local knowledge and experience that a motorhome trip through New Zealand is not the way to get the most out of your trip. For this reason, you can marvel at all of this directly from the window of your motorhome while driving. Just for information, not only the large mobile homes, but also the 2 bed campers with shower / toilet have a length of 6.40m to 7.10m. This is not the first time we have been with the motorhome and we have learned to park very brazenly (but not in violation of traffic), but even in many places we did not have the opportunity to do so.

Which flight route is the longest?

explains how long the shortest flight in the world takes. The shortest scheduled flight in the world is offered by a European airline. It is less than three kilometers between the Scottish Orkney Islands Westray and Papa Westray. According to the plan, a flight takes just two minutes.

Motorhomes without a corresponding certificate are not allowed to spend the night at many well-located campsites. The lakeside towns, Rotorua and Taupo, are easy to reach with a day trip and are centers for recreation in nature and offer a lot of fun for holidaymakers with mobile homes. In the cold months, however, we recommend heated motorhomes !. Our New Zealand travel offer includes cheap Fly & Drive trips (flight with camper, motorhome or rental car), rental car trips with pre-booked hotels, guided bus tours, adventure tours in small groups and with a German-speaking tour guide, hiking tours, bike tours, day trips, hotels and bed and breakfast houses and much more. Since 1998 we have been organizing guided and guided motorhome trips and houseboat tours.

Not later than 4 to 6 months before the start of the trip, as RV trips in New Zealand are very popular and campers are therefore quickly sold out.

The lakeside towns, Rotorua and Taupo, are easy to reach with a day trip and are centers for recreation in nature and offer a lot of fun for holidaymakers with mobile homes.

All the important information you need for a motorhome tour through New Zealand can be found in our practical motorhome guide.

Our accompanied motorhome tour through New Zealand is ideal for all travelers who like to travel independently, but still do not want to do without the security and the company of a group as well as a local German-speaking tour guide.

What is the climate like in Australia?

In the south of the continent, Maui campervans the Australian summer (October to March) is the most beautiful season. In autumn and winter (May to September) it can be cool and windy, snow also falls in the Australian Alps and Tasmania. The rainy season in the tropical north (wet season) extends from November to April.

And our RV in New Zealand was just great too. Of course you can also read my testimonials about my own motorhome tours in New Zealand. You shouldn't miss this ferry crossing on a motorhome trip through New Zealand. Anyone exploring New Zealand with a motorhome can hardly miss a visit to the metropolis Auckland. In principle, you can therefore drive your motorhome in New Zealand with a German driver's license. And if you are still looking for a suitable rental motorhome, you could find it among others at our partner SHAREaCAMPER. Driving around New Zealand in a motorhome doesn't just have advantages. 14 days flight and motorhome, for example, from Christchurch to Auckland. New Zealand flight and RV rental, individual travel, inexpensive travel modules and campers. We never had any problems and our motorhome was definitely one of the longest campers. We went one step further and were on the road with a large motorhome that measured a proud 7.30 meters. For beginners who have never driven a motorhome before, I would not recommend at least the North Island of New Zealand as the first choice travel destination with a large camper.

Neuseeland bietet eine große Anzahl an Campingplätzen, die Wohnmobilreisende aufsuchen können, um dort zu übernachten. Die verschiedenen Wohnmobil-Modelle in Neuseeland bieten jeweils eine gute Ausstattung auf kompaktem Raum. So können Sie es sich während Ihrer Wohnmobilreise in Neuseeland im Zuhause auf Rädern gemütlich machen!

0 notes

Text

098 Michael Eskenazi; President & Founder at Felix & Norton

http://www.alainguillot.com/michael-eskenazi/

This is the story of how Michael Ezkenzi created Felix & Norton.

In the early 1960s in the home kitchen at the age of eight, Michael Eskenazi was already wearing a chef’s hat, cooking up lavish 5-course meals for his family, always finished off with a lavish chocolatey dessert. Yummy chocolate was already his passion, all day long and even in his dreams.

Growing up, he had aspirations of becoming a great chef, but it remained simply a hobby while he worked for a variety of clothing retailers.

The inspiration to follow his dreams came during a trip to Manhattan where he discovered gourmet cookie boutiques on every corner, which was followed just days later by an incredible stroke of fortune - his employer fired him from his job. It was time to do what he was meant to do- Make people smile by baking the best cookies in the world!

Back from New York, and supported by his wife and a close friend, Michael began the most important challenge, creating the cookie recipes.

Simple research showed him that multiple chocolate chip cookie recipes consisted of all the same ingredients in varying quantities. If he was to sell only cookies, they would have to be the best cookies anywhere, so it would have to start with finding the best of each of the main ingredients.

For almost a year, his home kitchen became a lab. Different flours, different butters and of course different chocolates were tested hundreds of times. Family and friends were invited and forced to eat and give ratings for multiple versions of each recipe gaining a few pounds and lots of happiness, to create the recipes that are still used today.

On April 24, 1985, the first Monsieur Félix & Mr. Norton cookie shop opened on Queen Mary Road in Montreal. To be sure that some customers showed up the first day, cookies were brought early in the morning to various radio stations. Hopefully one or two of the eight selected stations would say something nice. They all did. By 9 am, there was a line up stretching down the block with hundreds of cookie connoisseurs waiting to sample these new creations. It was love at first bite, the fan base was starting to be built.

During the first four years, 8 boutiques were opened. Félix & Norton cookies became well-known throughout Montreal. Michael and Félix & Norton became local celebrities, cover stories in magazines and newspapers, radio and TV appearances.