#credit of the film his character is revealed to have more nuance and more depth than expected in the final act. the supporting cast is wall

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Silence of the lambs

The Enduring Legacy of The Silence of the Lambs

Few films have captured the collective imagination quite like The Silence of the Lambs. Released in 1991 and directed by Jonathan Demme, the film is a masterclass in suspense, psychological depth, and storytelling. Adapted from Thomas Harris' novel, it transcends the thriller genre, offering an unnerving exploration of the human psyche that remains as compelling today as it was over three decades ago.

A Cinematic Masterpiece

At its core, The Silence of the Lambs is a psychological cat-and-mouse game between two unforgettable characters: Clarice Starling, a young FBI trainee portrayed by Jodie Foster, and Dr. Hannibal Lecter, an incarcerated cannibalistic psychiatrist brought to chilling life by Anthony Hopkins. The film weaves their interactions with the grisly hunt for a serial killer named Buffalo Bill, creating a narrative rich in tension and subtext.

Jonathan Demme's direction plays a critical role in immersing the audience in the story. His use of close-ups, particularly during Clarice and Lecter's conversations, creates an almost unbearable intimacy. We feel Clarice’s vulnerability and Lecter’s predatory intellect with each frame. The result is a palpable sense of unease that lingers long after the credits roll.

A Study in Power and Vulnerability

One of the film’s most remarkable achievements is its nuanced portrayal of gender and power dynamics. Clarice Starling, a woman navigating a male-dominated field, is an unconventional protagonist for a crime thriller of the era. Foster imbues her character with a quiet resilience, making Clarice relatable and deeply human. Her journey is not just about catching a killer but also about confronting her own fears and insecurities.

Conversely, Hannibal Lecter is a study in controlled chaos. Hopkins' portrayal is simultaneously mesmerizing and terrifying. With his refined manners and piercing intelligence, Lecter challenges our notions of villainy. He’s monstrous yet strangely charismatic, making his interactions with Clarice both captivating and profoundly unsettling.

A Legacy of Excellence

The Silence of the Lambs is one of the few films to achieve the "Big Five" at the Academy Awards, winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Adapted Screenplay. Its success solidified its place in cinematic history, but its true legacy lies in its cultural impact.

Hannibal Lecter has become one of cinema’s most iconic characters, inspiring countless imitations and spinoffs, including the critically acclaimed TV series Hannibal. Clarice Starling, meanwhile, remains a symbol of determination and courage, resonating with audiences as a trailblazing heroine.

Why It Still Resonates

The film’s enduring appeal can be attributed to its timeless themes. It delves into the darkest corners of humanity, exploring fear, manipulation, and the search for identity. It’s a reminder that monsters don’t always hide in the shadows—they can wear human faces, smile politely, and speak eloquently.

Moreover, The Silence of the Lambs refuses to offer easy answers. It leaves viewers unsettled, forcing them to grapple with the moral ambiguities of its characters and the world they inhabit. This complexity ensures that each viewing feels fresh, revealing new layers to its story and characters.

Conclusion

The Silence of the Lambs is more than just a film—it’s an experience, a psychological deep dive that lingers in the mind long after the screen fades to black. Its influence on cinema and pop culture is immeasurable, and its ability to terrify, provoke, and enthrall remains undiminished. Whether you’re a longtime fan or a newcomer, revisiting this classic is a chilling reminder of why it continues to haunt us.

0 notes

Text

#law and disorder#1958#british cinema#charles crichton#t.e.b. clarke#michael redgrave#robert morley#ronald squire#joan hickson#lionel jeffries#elizabeth sellars#brenda bruce#jeremy burnham#george coulouris#meredith edwards#harold goodwin#john le mesurier#allan cuthbertson#michael trubshawe#sam kydd#john paul#minor brit comedy whose irreverence and slightness is really a strength; there isn't a lot to this‚ but it's honestly#so charming and so feather light that you can't help but be kind of swept along with it. a lot of what works rests on Redgrave's shoulders#in a beautifully measured turn as an unrepentant con artist who views increasingly long stretches in prison as a fair trade for the money#he can make and put away for the betterment of his son (who of course‚ knowing nothing of his father's 'work'‚ chooses to pursue a#career in the law). Morley at first appears to be playing the same kind of larger than life cartoonish buffoon he so often did but to the#credit of the film his character is revealed to have more nuance and more depth than expected in the final act. the supporting cast is wall#to wall brit character acting legends and that was the main appeal for me; nearly every speaking role is taken by someone of note‚ even if#(as in the case of permafave Alfie Burke) it's literally just 30 seconds of screentime. disposable fluff at the end of the day‚ but a#delightful kind of fluff‚ and a moreish kind‚ like cotton candy.

Law and Disorder (1958)

"Right, now listen boys, it's all lined up: we're getting rid of the judge."

"What?"

"Knock off a judge? You must be raving, we'll spend the rest of our lives in clink."

"Here, let me out!"

"We don't have to touch him. Police are gonna arrest him."

"Oh, that's better. Thought we'd turned nasty."

#law and disorder#michael redgrave#robert morley#1950s#british cinema#alfred burke#mariocki#wait you're not saying this is like. a decent film with Alfie in it??!! ;-p

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agents of SHIELD Season 1 Rewatch Update

Ok so I’m having a difficult time remembering what it was that made me hate this show so much (aside from the unforgivable Minecraft reference) and stop watching in Season 1.

Just got through ep 14 and holy cow, I’m honestly not sure whether the storylines for seasons 2, 3, and 4 were planned this far in advance, but if they were then these folks did such an overwhelmingly good job of keeping their eye on the ball.

Best I can figure, I’m having a good time on this attempt thanks to prequel-goggles. I already know where this story is going, who these people will become and what’s going to make them into what they will be, and I can appreciate this older storyline in light of the circumstances it precedes -- rather than for what it is without that context.

(It certainly helps that some of the dumber stuff is already starting to be replaced by the better stuff, like it’s ep 15 and the “night-night gun” was just replaced by the much more palatable “icer,” and they haven’t tried to call the individual dwarves by name for ages now)

Also there’s some pretty good cinematography, the graphics are really respectable, watching this found family slowly realize how much they love each other is sooo charming, and the affectations required of a MCU-spin-off-sci-fi-spy-show are really well balanced with the character drama which is its true heart.

I know ep 1x08 (”The Well”) is six and a half years old so maybe spoiler warnings are not necessarily required but here we go

Remember when Thor 2 came out and then this show had to earn its stripes as co-existing in the MCU so they had to address the fact that aliens ripped up London and the whole world knows about it?

Not being able to afford the likes of Chris Hemsworth was something they obviously had to work around, and plopping in that rando dweeby Asgardian as a twist was definitely one way to do it.

But the real showstopper is that the through-line of the episode is the examination of the similarities and differences of Ward and May, especially once they both come in contact with the Asgardian rage-stick.

Seeing Ward nearly incapacitated by his traumatic childhood memories serves two important purposes. First, it makes some good strides towards humanizing the man, who until now has been that hot-and-cocky kind of character that just expects to appeal to an audience but hasn’t yet earned any appeal whatsoever. By now, we’ve had a reference to his toxic dynamic with his older/younger brothers, and seeing him reliving his experience with the well suddenly opens him up and gives some dimension to that tall-dark-handsome cardboard cutout.

Second, those experiences are a really good twist!! When it’s revealed that he’s not remembering being tortured in a well by his brother, he’s remembering allowing his brother to torture his other brother down a well and not having the guts to do anything about it. It’s a good one-two punch because you weren’t expecting to pity the guy, and now that you’ve spent twenty minutes pitying him for being victimized, you get to grapple with the much more complex emotion of the kid!Ward not knowing how to get out of this lose-lose situation and understanding that his current character must be in some way informed by this regret and guilt.

THIRD, after seeing Ward go through all this and barely hold it together, we get to see how May handles this level of relive-your-worst-trauma-and-incinerate-yourself-with-unbridled-rage when she has to pick up the rage-stick and .... instead of it leaving her on the ground like it’s just done to Ward, she somehow experiences 0.00000% change in personality or capability WhatSoEver.

She not only isn’t affected, she summons all the broken pieces of rage-stick and effortlessly wields the fully formed berzerker staff to defeat the rest of the baddies single-handed. It says so much about her character, about the depths of the trauma that sent her to the place we met her in in the pilot. We still don’t know what happened, but this her “my secret is I’m always angry” moment, and it’s a level of anger has been repeatedly and thoroughly cataloged throughout the episode so far.

It also gives these fools something to bond over. And while I’m seriously disinterested in their weird little Thing that didn’t go anywhere and didn’t really impact much, it was a nice way to avoid progress in the “Skye’s falling for her SO” storyline that I don’t care for either.

But Skye makes her move in this episode! She and Ward dance around the possibility that maybe they’re into each other and they could possibly move from antagonistic strangers to folks who are a little into each other. But he does the gentle thing and turns her down! (without closing the door entirely, I must add) And then he wanders off on his own and ... May’s wandering off on her own ... and they share some micro expressions and then, seriously you guys this sequence is so tasteful and understated, just look:

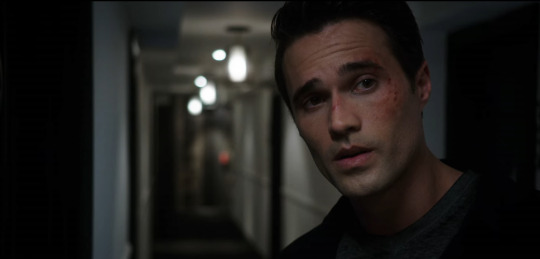

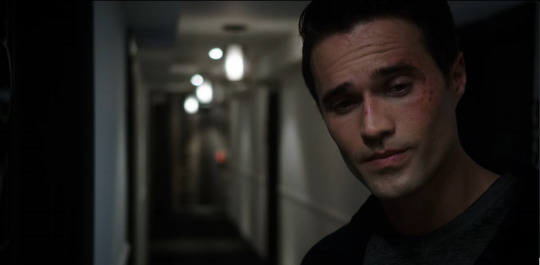

Ward leaves Skye at the bar with a parting “I’m beat, another time, maybe,” and off her wistful look we cut directly to this chiaroscuro hallway.

Ward enters the frame, starts unlocking his hotel room. He's just another monochrome shape in this monochrome place.

But then there’s May entering the shot at the far end of the hallway, and her motion and his turning to look at her frames her monochrome shape in this nice little white triangle between him and her door.

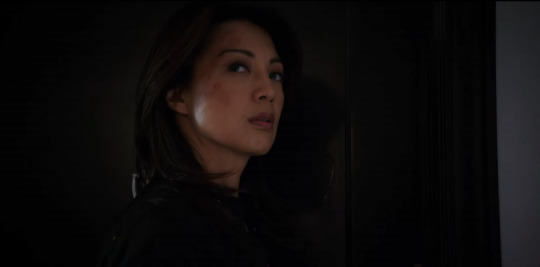

And there’s a tasty little rack focus that pulls the instant she passes in front of the door, making sure our attention is on her and the little white label of her bottle that really pops in the sea of black.

By this point in time, we’ve been shown, graphically, intimately, a dark shadow in his past, and we’ve been shown the physical and emotional toll its taken on him (an insight provided by the magic alien macguffin, btw). We haven’t been told anything, we experienced his experiences with him via the power of cinema. Her specific trauma is still a mystery at this point, but we’ve been given enough information to understand and appreciate its effects on her character. So not only can we sympathize with Ward now, we can sympathize with his empathy for May in this moment.

She catches him looking.

I mentioned micro expressions and screenshots do not do these performances justice. How does one catch in a single frame the millisecond that an eyebrow ticks in asking a silent question?

Typical for her, May’s answer is also communicated through body language.

From that canted, inviting look, we pan down as she unlocks her door and enters. She passes through the frame and disappears inside, after giving us a reminder that her plans are to apply alcohol to her issues. (Remember that Ward turned down Skye’s invitation at a bar of all places)

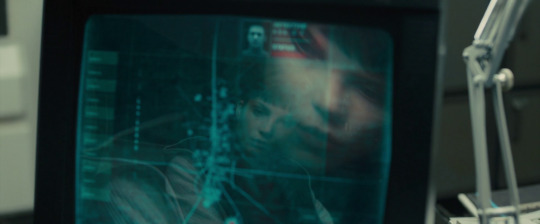

Oh, and what has our framing left us to contemplate? Is that a bed I see in there? (Remember that Ward turned down Skye’s invitation) Let me point out that this shot of just the bed after May walks by is on screen by itself for maybe a fraction of a second. Just a suggestion of a thing, really.

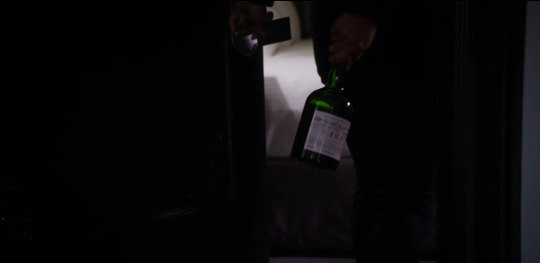

Ward contemplates.

I love returning to this shot because it’s literally the same set up, and my instant reaction is that it’s another insert, a POV shot, and I fully expect to return to the single shot on Ward to discover his decision the second he makes it.

INSTEAD. Ward walks immediately into THIS FRAME, too, black-shape-on-white-shape in the same way May was introduced to this scene. And we stay here as he closes the door behind him ...

Letting us know everything we need to know without a single word needing to be spoken.

Another fraction of a frame dwelling on that shot and then immediately fade to black. Credits. Show’s over, folks.

And not that there’s any particular meaning in it, but they were super careful to minimize what colors were allowed to appear in this sequence? Like there’s a particular sort of green in that weird armchair, which sort of matches the green-glass of her bottle. And there’s the red of the fire alarm fixtures which more or less matches the red of his, y’know, fresh facial wounds. EVERYTHING else (other than, I guess, their skin tones) falls somewhere along the white-black spectrum. NICE. BEAUTIFUL. I LIKE IT A LOT.

And the Netflix synopsis for this episode is “In the aftermath of the events chronicled in the feature film Thor: the Dark World, Coulson and the S.H.I.E.L.D. team try to pick up the pieces.” 1) I’m realizing that they literally go around picking up pieces of the rage-stick and that’s hilarious but mostly I mean to say 2) this MCU-tie-in episode could have met the brief being as vapid and non-impactful as that blurb makes it sound. But it took the opportunity to open up its characters for us to see their gooey insides, and hell they picked two of the best characters to dig into for this one, considering Ward’s tragic backstory plays as both a misdirect and actual inciting incident for his betrayal of SHIELD, and May’s tragic backstory feeds a couple of B-plots this season as well as being the major catalyst for a lot what happens in season FOUR. SEASON FOUR, PEOPLE. THE SEEDS ARE WAY BACK HERE IN SEASON ONE.

REMEMBER HOW THESE CHARACTERS WERE INTRODUCED THOUGH?? I DO, I JUST WATCHED THE PILOT LIKE YESTERDAY. WE MEET WARD FULLY ENSCONCED IN HIS GUISE OF SHIELD BADASS SUPERSTAR; HE IS LITERALLY ASKED TO EXPLAIN WHAT SHIELD MEANS TO HIM, AND WE GET TO HEAR THE FIRST OF HIS MANY LIES. WE MEET MAY IN HER OWN PERSONALLY-DESIGNED WHITE-COLLAR HELL, TURNING COULSON’S OFFER DOWN THE SECOND SHE HEARS HIS VOICE BECAUSE SHE’D RATHER STAPLE DOCUMENTS FOR ETERNITY THAN BE OUT IN THE FIELD WHERE SHE CAN MAKE ANOTHER MISTAKE LIKE THE ONE SHE CAN’T FORGIVE HERSELF FOR.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. This show knows how to weave a character-driven story, and it’s done it for six seasons straight, juggling constantly evolving -- grounded, nuanced, impactful -- character arcs with the external factors (Thor: The Dark World, for one) that force certain narrative decisions.

(until they decide to ignore those factors altogether, lol, I’m looking at you, season 5, you wacky maverick you)

#agents of shield#aos#the well#grant ward#melinda may#a long rant about things I love#it's nice to rant about positive things for a change

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little Women (2019) Thoughts

After some frustrations (this movie sold out incredibly fast), I managed to see this new adaptation (not a remake, very much so) with my two youngest siblings, with whom I’ve read and discussed the book, and seen both the 1994 and 2017 miniseries. Briefly, all of us prefer the 94 film (with Winona Ryder as Jo and Christian Bale as Laurie), but all three versions, this one included, have many charms worth discussing.

To start with, this film avoids the recasting issue that plagues Amy in the 94 version by starting with Jo in New York, using a flashback structure (similar to, but much better utilized, as that seen in the 2011 Jane Eyre film). Though Amy is still way too old, Gerwig’s script and Florence Pugh’s performance don’t push the character into the kind of ludicrous unlikeability of having a clearly 20-something actress do things that 10 year olds would be ashamed of. The visuals are also glorious, much better than the trailer seemed to suggest to me - the scene in the valley where Laurie proposes to Jo was jaw-droppingly gorgeous in use of landscape and framing (though ever since 1995′s Sense and Sensibility, I’ve been worried whether landscapes in period drama are CGI. Ah, well). As noted previously, the structure also prevents one of the most obvious complaints that hit the 2017 miniseries very hard - that it’s a “remake” of the justly beloved 1994 film. By making a film that focuses so much on aspects that the 1994 film elides or omits, it’s clearly not a remake, but a new adaptation saying interesting things about the book (though, as I remarked to my brother, it’s almost like the “deleted scenes” version of the book, focusing on a lot of stuff that doesn’t seem to happen in the book, providing depth and motivation for the adult sections).

All this positives made the film quite enjoyable and worthwhile seeing. That is not to say there aren’t drawbacks. The chief complaint I have are the moments where my philosophical differences with Gerwig rub too hard the wrong way. The line about Marmee being ashamed of her country, Amy’s speech about coverture (though that is likely fairly solid in terms of feminist rhetoric of the time, and likely deserves more study by myself), which struck me more as commentary on what Gerwig thinks about her audience than about the book. More than these two notes, however, was the handling of the ending. I have no objection to the ending Alcott gave Jo (especially in light of Little Men and Jo’s Boys) - marriage to a man she loved (who I believe she loves, though I know that seems to be a minority position) as well as worldwide success as an author. Gerwig, on the other hand, deliberately implies that Jo gets the book, and the marriage is fiction demanded by her editor. (For more support for the Jo/Bhaer ending, I provide these excellent links - https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/tag/professor-bhaer/ - examining Bhaer in the books and films and provides great weight to the argument that Bhaer is more than just a commercial decision or “spiteful” whim as Gerwig claims - and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=osdVRusNGgg, examining the way the 2017 miniseries handled the issue.) The way Gerwig handles Bhaer is very romantic - perhaps to the exclusion of his intellectual appeal for Jo, though his honesty about Jo’s potboilers is well handled - but when it becomes an intentional, obvious parody of the “airport scene” in a romcom and it’s revealed as a fake demanded by the editor, a sour note is struck. Everything works towards Jo/Bhaer being satisfying in the film, which makes the attempt at philosophical statement deliberately scolding the audience for wanting that satisfaction much more frustrating.

Well, I say everything works. There’s one element that is completely unnecessary, even though it had a lot of promise. Jo makes the impassioned speech about female ambition which made the trailers, and though excellent articles point out that it’s directly from another Alcott novel - https://slate.com/culture/2019/12/little-women-movie-ending-explained-twist-jo-bhaer-married.html - normally would NEVER link to Slate, but this is honestly well argued on both sides, and I really appreciate Heather Schwedel’s take arguing in favor of the book and Jo/Bhaer). The speech doesn’t quite work for me - perhaps knowing that it’s from Alcott will help when it comes out on bluray, but it felt out of place. That quibble aside, unlike the trailer, the film has Jo end the speech with “But I’m so lonely.” Which I thought was a beautiful bit of nuance - showing the tension (often derisively mocked with the commentary about “having it all”) of ambition and the human desire for connection and community approval. That loneliness could have played well into a less ironic, above-it-all ending with Bhaer - but instead, Gerwig inexplicably decides to play Jo’s desire for Laurie some more, adding in a letter from Jo to Laurie begging him to propose again. I could sort of see the desire in Gerwig to play with the excellently handled Jo/Amy relationship, but it throws the emotions for a loop, and doesn’t work at all.

A few other moments don’t work quite as well. Jo’s writing of her novel - though perhaps, like the female ambition scene, was actually a common practice in novel writing of the mid-1800s, felt too much like a film pitching process instead of writing a prose narrative. That clash of artistic process wasn’t helped at all by the generic scoring of that section of the film by Alexandre Desplat. Perhaps unfairly, the 1994 film had a truly transcendent score by Thomas Newman, which stands out not only as a nearly perfect score for the film, but one of the best film scores of all time. The 2017 miniseries isn’t nearly as good as Newman’s, but does provide powerful moments like this one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EosnXGSiDck

Lastly, Eliza Scanlan and Emma Watson as Beth and Meg are both left behind by several choices in the script, partly the fault of the flashback structure, but partly because it’s clear that Jo and Amy clearly interested Gerwig most (and it’s to her credit that she gave Meg the “my dream is valid” speech). Watson’s weakness as an actress continues to plague her scenes, especially in the scene where she voices her frustration about her poverty to her husband, and her eyebrows refuse to stop overacting. Beth is mostly just lost - interestingly, none of the filmed versions that I recall have allowed Meg to comfort Jo after the selling of her hair - this film highlights the Jo/Amy relationship in that moment, and the 94 film gives it to Beth (likely to beef up her part). Much as I love Claire Danes, I think Annes Elwy from the 17 miniseries is the best, most nuanced and accessible Beth on screen that I’ve seen.

In conclusion, this film is a work of art worthy of enjoyment and analysis, despite these disagreements I have. There’s a clear sense that Gerwig and her team created a richly textured world that existed outside of what we see - each scene gives the actors things to do that enrich their lives in my mind, and I love spending time with them. It resists easy relationship resolution - Jo’s frustrations with Amy don’t end with the ice breaking incident, and unlike a lot of the other versions, give Amy a LOT of mature and intelligent conversations, showing that it’s not all Amy’s fault that the two don’t get along. I don’t think Ronan, despite being one of my favorite actresses, will replace Ryder as my perfect Jo (even though I think I’ll appreciate Ronan as an actress much longer than Ryder - since her later career seems to be entirely made up on neurotic mannerisms, sadly), but she’s very powerfully written and played. Laurie follows a different route than Christian Bale or Jonah Haeur-King, but like those two, is also incredibly good. The proposal scene chooses differently, but equally powerfully and realistically, with what Laurie does in the face of rejection. Marmee played by Laura Dern is beautifully done, though she doesn’t have the script of Emily Watson in the miniseries giving her a lot more depth and connection with the audience. I don’t know that Florence Pugh can displace Kirsten Dunst as young Amy, but she’s definitely one of the best Amys on screen (though I think Kathryn Newton in the miniseries did a better job of changing her body language and mannerisms to show the character aging). Definitely recommended, and recommended to discuss afterwards!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

What We Talk About When We Talk About Luv: The Beauty and Horror of Blade Runner 2049′s Tragic Antiheroine

“I’m the best one.” Luv declares as she struts away from K, fresh blood from a stolen kiss adorning her face as she departs, having again reduced her opponent to helplessness and having again decided, bafflingly, not to kill him.

If we think of Blade Runner 2049 as a pretentious yet inferior movie, a pale imitation of its source material lacking all the intellectual and emotional resonance of the original, these four words spoken by Luv mean nothing, existing as a tossed off line spoken by a tossed off character in a film that accomplishes nothing aside from looking pretty and making you wish you were watching the original.

I disagree. I think Luv is incredible, one of the most fascinating, nuanced, and profoundly tragic characters I’ve encountered in a very long time, a figure who both deserves and rewards our attention. Though it’s easy to miss during an initial viewing (I certainly did) Luv has a rich, deep story arc that branches through the whole of Blade Runner 2049, one that both parallels and intersects with K’s story, the two characters informing each other even as they violently ricochet off one another. Once understood, the tragic depths of Luv’s story don’t just reveal a remarkable character but enrich the movie as a whole, adding an extra dimension to a narrative already dense with meaning.

Luv, like our central protagonist K, is a Nexus-9 Replicant model, a product of the Wallace Corporation. When we first meet her she is in the process of selling other Replicants as Off-World slave labor. This may seem like a betrayal of the first order but, as we will soon learn, Luv does not see it that way.

Luv works directly under CEO Niander Wallace himself, acting as his personal assistant, assassin, and all purpose fixer. While Niander Wallace is the face Technological Capitalism chooses to show the world--brilliant, eccentric, full of glorious and high minded ambition, a Ted Talk come to life--Luv represents it’s actual real world consequences: empty sadism, nihilistic violence, and ignorant self-aggrandizement, which is not to say that Luv is stupid. Luv knows she is a slave but nevertheless exalts in her position because she is the best slave, Niander Wallace’s chosen instrument. If Niander Wallace is God, and he certainly seems to think he is, Luv is his "First Angel”, the chosen means by which he enacts his will on the world. Luv knows this, but she can’t bring herself to fully comprehend its ramifications, a failure of understanding that ultimately leads to her tragic destruction.

Any discussion of tragedy would be incomplete without at least a brief detour to account for the Ancient Greeks, the originators of Tragedy as Western Civilization knows it, so let’s get it out of the way now. All tragedy results, on a fundamental level, from a failure to obey the message inscribed above the Oracle of Delphi: “Know Thyself”. When you don’t understand yourself, you open yourself up to becoming prey of the Gods, what today we might call the Passions, though few Greek Tragedians would have recognized a distinction between the two. (Euripides being the notable exception.) The most famous embodiment of this kind of tragedy through self-ignorance was Oedipus, the subject of the tragedy Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. Though a prisoner of fate, Oedipus effectively strolled into his own cage by letting his passions rule him, first by giving in to his wrath by killing a stranger he met on the road, and then by giving in to his lust by marring the wife of the man he killed. When wisdom finally comes to Oedipus in the form of the realization that the man he killed was his father and the woman he married is his mother, it arrives too late to save him, and instead destroys him.

The character of Luv in Blade Runner 2049 bears less direct blame for her own tragic fate, yet the mechanisms by which it operates are fundamentally similar. Luv does not understand herself. The result is pain and suffering, yet it is far more nuanced than it first appears. What superficially manifests as depraved cruelty is, in fact, the result of a more fundamental lack, the sort of profound misunderstanding of her own nature that elevates her from the status of a mere hired goon to a character worthy of our consideration, and even our sympathy.

Unless I’ve overlooked something (which is entirely possible) Blade Runner 2049 makes no mention of whether or not Luv has the sort of artificial memory implants that prove such an integral part of K’s personality and story. Knowing this is vital to understanding her character, and while there is no way to be absolutely certain, I believe Luv’s actions clearly demonstrate her lack of a synthetic past, maliciously depriving her replicant mind of what Eldon Tyrell in the first movie called “a cushion or a pillow for their emotions”. As a result I believe, despite her often cold exterior, Luv is a raging tumult of conflicting, contradictory emotions she can neither understand nor control, paramount of which are her feelings regarding K.

Luv expresses interest in K during their first meeting, her fascination paralleling the sparks that fly between Rachel and Deckard in the old recording they both listen to. Unlike the meet-cute that occurred thirty years prior in the first Blade Runner, the attraction isn’t mutual, and when Luv attempts to inquire further into K’s life he rebuffs her. This quiet, polite rejection will ultimately have devastating consequences for both characters. K makes a powerful enemy, while Luv becomes divided against herself, afflicted with powerful feelings she has no context for or understanding of. As Kierkegaard said, life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards. Without any history there can be no understanding, we become disconnected and begin to float, easy prey for any passing impulse. Knowing this doesn’t let us absolve Luv of her misdeeds, but it does give us a chance to reach a better understanding of her, as well as the more enigmatic aspects of her behavior.

We see Luv cry twice in Blade Runner 2049. The first time is when she sees her master Niander Wallace stroking and bidding happy birthday to a newborn female replicant (credited only as ‘Female Replicant’) who he then proceeds to murder by stabbing her in the womb, a brutal crime committed for no real reason other than vent his frustration and illustrate a point in a monologue he’s delivering more or less to himself. The second time is when Luv tortures and kills Lieutenant Joshi, K’s master. Both instances involve a woman being murdered, stabbed to death specifically, their body violated with a piece of metal in a grotesque pantomime of the act of heterosexual lovemaking. (When Blade Runner’s symbolism isn’t Judeo-Christian it’s Freudian. Freud would have diagnosed Luv with the three A’s: Ambiguity, Alienation, Ambivalence.)

When Luv cries with Niander Wallace it is in response to the nameless female replicant shedding her plastic birth caul and spasming into life. Luv casts a fleeting glance upward as the tear rolls down her cheek as if in acknowledgement to a higher power that bestows the transcendent spark of life, but if that’s the case any pretense to the sacred is destroyed when Niander Wallace murders the newborn replicant, an act that serves as a vulgar reaffirmation of his own mastery over life and death.

When Luv cries a second time it’s in response to her torturing Lieutant Joshi by crushing shattered glass into her hand, an act of sadism that concludes with Luv murdering the Lieutenant outright.

The fact that Luv sheds tears in both instances despite their profoundly different circumstances may lead us to the conclusion that Luv’s tears have no real emotional resonance, instead being an involuntary autonomic response to any extreme stimuli, what is little more than a bug in her design. It’s a natural assumption, but one that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

Luv is the best one, at least as far as her status as a consumer-grade product is concerned. She is the pinnacle of Wallace design, the closest to perfection he’s yet managed to come. If Luv had a fault in her genetic architecture that made her cry at inappropriate times, Niander Wallace would likely have disposed of her with the same dispassionate matter-of-factness he disposes of everything that mildly displeases him. Yet if Luv’s tears are genuine, how can we make sense of them?

The answer is the absence of her memories. Without the mental foundation of memory that would provide her with a chance to ground the violent events she experiences and violent emotions she feels in context, Luv is helpless to control how she reacts, a condition her judiciously maintained cool exterior can only do so much to hide.

The tears she sheds while witnessing the nameless female replicant’s birth and the tears she sheds while torturing and killing Lieutenant Joshi are both genuine. This is naturally confusing since the situations are so different, but as the author Leonard Richardson writes in his book Constellation Games, (which I cannot recommend highly enough) crying does not mean you’re sad, it means you’re experiencing an emotion that’s too large to keep inside of you. Blade Runner 2049 throws us off the scent because the first time Luv cries the cause is obvious, then when she cries for a second time it seems completely inappropriate to the situation, yet when we appreciate the emotional tumult storming inside Luv, both reactions begin to make congruous sense. The first time Luv cries it is out of empathy and a sense of the sublime. The second time Luv cries it is out rage fueled by a mix of resentment and jealously.

When Luv first strolls into Lieutenant Joshi’s office she says in regards to K “I like him. He’s a good boy.” an evaluation Lieutenant Joshi’s silence seems to affirm. Lieutenant Joshi is a character who, let us not forget, is for all intents and purposes K’s owner and master, having the same power dynamic with him that Niander Wallace has with Luv. Killing Lieutenant Joshi not only serves the practical purpose of giving Luv free reign to access Lieutenant Joshi’s computer and find K, but it also gives Luv a chance to eliminate a romantic rival, experience the catharsis of killing a human master in a way she never could with Niander Wallace (who she needs to reaffirm her status as the Highest Angel), and eliminate the person that has enforced rigid control over every aspect of K’s life. She’s acting out of a very warped sense of duty to K, not quite the sort of redeeming "kinship” that led Roy Batty to save Deckard’s life at the last moment, but a kind of solidarity nonetheless.

When viewed from this perspective, the desires motivating Luv are very fundamental and very human. She wants solidarity with her fellow replicants. She wants revenge on those who’ve enslaved her. She wants to experience romantic love. The fact that she gets none of these things, that she has been explicitly denied the capacity to understand what these desires are and how to act on them and is instead forced to derive comfort from her status as the best one, the best product, the best slave, is what elevates her as a character beyond the stark dichotomy of victim or villain to the higher echelon of tragic antiheroine.

Luv spares K’s life twice in open defiance of the spirit, if not the letter, of Niander Wallace’s commandments. The first time is when she and her fellow Wallace fixers storm Deckard’s Las Vegas sanctuary and abduct him. K fights back despite being wounded thus forcing Luv to beat him into submission, though when the time comes to move in for the kill, she holds back. Instead she kills Joi, K’s holographic A.I. companion, crushing the emitter that contains her consciousness beneath her radiantly polished boot.

Immediately before doing so she says “I do hope you’re satisfied with our product.” Luv looks at Joi when she speaks the line, though it seems to be intended for Joi, K, and Luv herself, all three of whom are themselves commercial products of the Wallace Corporation. It’s a line that can be read as pure sarcasm, yet when considered in the context of what we’ve been talking about, we can view it as a sort of question, and a sort of appeal as well. Joi and Luv are both Wallace Corporation products, but Luv knows herself to be the best product. There is an implicit “Why?” in Luv’s words and actions, an inquiry that demands an answer from K. “Why Joi and not me? Am I not the superior model?” K choosing Joi over her is an insult to her attraction and an affront to her pride, yet the only way she can express her outrage is with violence. By destroying Joi she demonstrates her preeminent status as a product, while also eliminating another rival for K’s affections.

Luv departs without another word, leaving K alive. It’s safe for us to assume that Luv hasn’t simply fallen victim to the classic bad guy cliché of incorrectly assuming the good guy’s dead. They are are both the same model of replicant, there’s no reason for us to think she isn’t precisely aware of both K’s limits and his potential. Luv is still intrigued by K in a way she doesn’t understand, and lets him live secure the the knowledge that they will meet again under similarly unpleasant circumstances. By then the scales will have completely fallen from K’s eyes and he will be endowed with an unshakable sense of purpose, his own personal raison d'être. Luv will not be so fortunate.

K, at great cost, comes to understand who and what he really is in time for him to act on it in a way that gives purpose to his life and, more importantly, his death. Like all great villains Luv is K’s antitheses, a distorted reflection of him, what C.G. Jung might identify as his shadow-self. K begins the movie doing the same thing Luv does, namely killing on cue in accordance with his design. The difference is K encounters people who change his worldview, making him aware of the possibility of altering his circumstances. Luv never gets that chance.

The name ‘Luv’ is obviously dumb, the kind of dull platitude you’d find on a candy heart or in a rushed-off text message, and the fact that it is the name Niander Wallace chose to bestow on his First Angel shows the true indifference he feels regarding her, how the contempt he has for all life extends to her as well, despite his lofty rhetoric and empty praise.

Names are powerful, but they aren’t enough to imbue one’s life with meaning and purpose, a fact illustrated when a massive advertisement addresses K by his adopted name, the name Joi gave him, calling him “A good Joe.” Not only does this show that even something as personal as a name bestowed by a loved one can be corrupted and co-opted by Technological Capitalism, but that both Joi and the advertisement are probably making decisions based on the same artificial intelligence program, leading both of them to pick the same name out of thin air. This works to expose K to the artificiality of the relationship he had with Joi, forcing him to seek out something more authentic and human. It’s the sort of epiphany Luv is denied, so while she does seek to form a sort of relationship with K, the why and how of it completely eludes her, leading her to act on a sort of animal instinct that can’t distinguish between aggression and affection, two very different human Passions that appear to her as indistinct aspects of the same raw emotional yearning she becomes less and less capable of containing over the course of the story, a compulsion that climaxes with her beating and stabbing K nearly to death, then following it up immediately with a deep, soulful kiss.

The final battle between K and Luv at the sea wall isn’t just a grim parody of the iconic scene of two lovers passionately entwined in the surf from From Here To Eternity. (Though it is at that.) It’s a baptism.

Christian baptism is a ritual where the physical is sanctified and thus made to represent the spiritual, its invocation of grace elevating the ritual to transcend the mundane and evoke the divine. When Luv and K fight they are also sanctified by the symbolism surrounding them, which renders the conflict more significant than two people beating each other up. It is the physical versus the spiritual, the sacred versus the profane, the meaningful versus the meaningless, an elemental confrontation between the loftier and baser aspects of reality. For Luv the thing that matters most to her and carries the most meaning are her Passions, which aren’t in themselves bad, but when misunderstood and uncontrolled lead to destruction. In her fury she attacks and defeats K, and in her infatuation she yet again neglects to kill him. Her mercy is rewarded with death.

The final contest between K and Luv is their mutual attempt to drown one another, one that ends by demonstrating the ultimate disparity in their respective personalities. Both Luv and K forcibly hold one another underwater for what are at first roughly equivalent amounts of time. K survives because he is able to exert enough control over himself to hold his breath until he can turn the tables. Luv in contrast dies because she is a slave to her Passions. Instead of holding her breath and waiting for an opportunity to regain the upper hand she rages, clawing and growling, resisting with all her unchecked strength until her life is totally spent.

K and Deckard partake of the waters, die, and are born again. Luv is subjected to the same trial, but she is denied such grace. She is the First Angel, the most raw and brilliant and terrible, and as such, she must fall in all her dreadful glory, our horrible, beautiful, drowned Lucifer.

Like the studio-mandated happy ending of the original Blade Runner that everyone loathes, there could be another ending to this movie, a more conventionally satisfying ending where K and Luv gain a deeper understanding of themselves and, in doing so, find the capacity to care about and even love each other. It would be nice, but it would also deny Luv her final tragic grandeur, and us the vision of a true antiheroine.

The actress Sylvia Hoeks’ portrayal of Luv is as eerily perfect as the character herself, a performance that easily ranks among the best popular depictions of uncanny quasi-humanity ever rendered, on par with Christian Bale’s Patrick Bateman, Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lector, and Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty. Luv is also different, a step beyond but also a step removed. The sheer virtuosity of Sylvia Hoeks’ performance is largely based in restraint, the sort of illusion of control that Luv is so good at deceiving herself with that it’s easy for us, the audience, to be deceived as well. It is right and good that we bemoan the lack of good female roles in popular cinema, but such objections can come to ring hollow when they come from an audience that routinely overlooks outstanding exemplars like Luv, a rendering that’s brave enough to not be obvious, whose peripheral status in the narrative does nothing to diminish. I don’t think we’re going to see a great many characters equal to Luv in the future, not only because it’s rare for a concept this good to be executed this well, but the demographic of people who were once most inclined to notice such things are now largely intellectually hemmed in by an ideology that Blade Runner 2049 does not neatly fit into, and who thus deem it unworthy of consideration. It is my ardent hope that it will eventually find a public worthy of it, just as its predecessor did. It’s the reason why I’m writing this, why I’m proselytizing for Luv, who is, after all, the best one.

OTHER PUNS I CONSIDERED WHEN TITLING THIS ESSAY

All You Need Is Luv

Luv Will Tear Us Apart

Luv Story

Luv Actually

The Luv Guru

Me Luv You Long Time

233 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final

Over the past two or more decades, television has changed into a new model of storytelling, which is different from the conventional serial forms and episodic that were previously televised. Complex TV is the new model, which infuses multifaceted narratives as the norm television shows that air throughout the developed world. Essentially, it has redefined episodes under the guidance of serial chronicling with a shift in balance. It includes dismissing the requirement for the plot of television show to close inside the scene in way that foregrounds continuing stories in a scope of genres. A plethora of serial practices exist that can be employed based on the supposition that the narrative in the series builds over time. Being unconventional is the most defining feature of complex television. However, there are other features that characterize narrative complexity in modern TV. They focus on the serial as opposed to the episodic. They have an extended depth in the way characters are portrayed. Typically, the script is that of narration and storytelling coupled with an ongoing and constant plot. Characters also shift in perspective with each varying episode. It is also common to come across a commentary in television shows that explore their narrative stunts. Suspense is also a major feature that seems to be part of complex television, and the most active audience speculates about what might become of lead characters or a major twist in the plot (Mittell 20). Collective intelligence between the fans and the film is ubiquitous, and they participate quite intensively from the first to the last episode. This case study focuses on a series of TV shows that are ideal examples in demonstrating the Complex TV phenomenon, and they include Westworld, American Gods, Walking Dead, and Legion.

A lot of people conflate the description of the film as, “Highly Serialized Drama” with long-form episodic examples such as the X-Files and Twin Peaks. For a show to live up to its concept, it should not be predicated on a central narrative enigma not attached to future events triggered by narrative statements (Mittell 19). A show such as Revenge typically embodies complex television because its narrative thrust is simply forward moving, but with a keenness on insights and flashbacks that pop up in episodically so that the viewer understands key aspects about characters. Viewers do not have to grapple with deep mysteries in which they have to piece together hints to understand a character. Therefore, the common feature is that viewers are aware of narrative statements that are accumulated over time so that they have a clear understanding of possible future events that shape subsequent episodes. It is against the same backdrop that viewers and fans of Westworld, American Gods, Walking Dead, and Legion should understand them in terms of complex television. Character portrayal, the plot, the narrating, and storytelling style is in such a way as to dissuade viewers while maintaining a concrete storyline characteristic of complex television.

Westworld disorients viewers through its robotic characters portrayed as having their lives hanging on a loop. Thus, it means that the show’s storyline takes place over a long time, but it could also appear in a sequence, which further confuses the viewer. Westworld is reminiscent of the Marvel series Legion in which the characters’ bodies are swapped, and the audience is just not sure if the characters are really themselves or their swapped personalities. The common shifts between characters in complex television are thematically triggered by contemporary phenomenon among people whereby they have to constantly interrogate the realities around them. For instance, one might view their perception of an unusual scene as magical, artificial intelligence, psychosis, or just the side effects of trauma. The fact that they are not sure is reflected in complex television through character shifts. With the information age at its peak, it is quite difficult for one to differentiate between what is real and fake. The notions of reality are increasingly being distorted by a bombardment of news from different online platforms. Therefore, the idea that characters in Legion can swap bodies reflects the experiences of a typical contemporary television viewer. Perhaps the confusion created in complex television is the real source of fascination that the audience has with contemporary television shows.

The character swaps in a single storyline of a show and the use of robots show that the two shows mirror the transcending feature of complex television that projects a future that seems quite far but increasingly plausible. Traditionally, television has often been a way to escape reality, but complex television exposes certain ways through which realism gets constructed. It makes the audience to think whereby it is common to come across fans reading online recaps of shows just to understand certain things such as the real character, an actor’s alter ego or a twisted aspect of the plot. Towards the end of Westworld’s first season, for instance, there were already murmurs in its fan base that it had failed to exhaust the themes of humanity and consciousness. Some pundits went as far as challenging the notion that the series portrayed complexity as being equal to ingenuity. Complex television such as Westworld creates another significant platform in entertainment, including dynamic entertainment blogs keen to delve into the complexities of plot, character portrayal, and other nuanced issues.

Complex television is also about an extended depth of characters, and episodes vary from each in ways not contemplated by the viewer. The opening scene of American God, for instance, demonstrates the complexity characteristic. The series is based on an adaptation from one of Neil Geiman’s novels. The show is, indeed, human fantasy, but it is the depth of characters that makes it stand out from the rest of the shows aired around the same period of cable news networks. The audience for American Gods has to be really captivated, and it has to watch quite actively to understand even the first episode. There are soliloquies that are quite overdone. For example, “Technical Boy” in the film, who is the god of technology, soliloquizes, describing language as “a virus”, religion as “an operating system”, and prayers as “spam”. The gods undergo some temporal shifts and change their body shapes.

In one lewd scene, a goddess sucks people inside her by repeatedly having sex with them. Until that point, “Technology boy’s” point about language is evident. There is no difference with Westworld, which portrays a futuristic theme park in which humans have sex with lifelike robots before murdering them. Boston Dynamics and Jurassic Park are quite a phenomenon in the series. There is an enviable depth in character portrayal and the roles they play to advance the plot and set the stage for the next episodes. Interestingly, character complexity may sometimes turn off fans instead of intriguing them. The raping and murder scenes in Westworld might be quite unlikable, but they emphasize the typical feature of complex television.

The opening and closing brackets of each episode in most shows is debatably the most vital feature of the role screen time in establishing a balance between the serial and episodic form. Screen time often defines a specific episode as a distinct part of storytelling and it also entails the break between episodes (Mittell 27). A scene in many shows starts with a critical marker(s), for example, a short recap of scenes in the past episode, an opening title sequence of variable length. Similarly, a scene ends with closing credits that preview future accounts.. The show, Walking Dead illustrates the feature of opening and closing credits quite well. The storytelling in the show’s season finale evokes the events that shaped scenes in previous episodes. At the same time, it makes major and minor references to characters throughout the series. The devices employed to bring up the major theme of zombie survival, which also follows the current trend of narration in complex television. All of the screen-time elements as illustrated in Walking Dead exist outside the story-world and even its narrative. Like in series, the plots are stringed and arced across one full season. Nonetheless, the producers of the show always understand and try to make it such that each episode is a separate narrative that follows the pattern of screen time already set in the previous episodes. However, the first ten minutes of each episode is actually a recap of the final act in the previous scene. The compelling bridge between episodes is manifested in the way fans religiously look forward to the next episode.

Characters in complex television shows have intricate histories, which further convey the same inherent feature. Character complexity tends to compliment character depth. In Legion, for instance, David, the main character, has a complex history that only requires several visits to blog sites to be able to fathom. He is born of Charles Xavier and a survivor of the catatonic Holocaust. The latter was the former’s patient during his earlier visit to Israel. Up to that point, it just seems complicated that David exists in the first place. The viewer immediately becomes curious about his peculiarities. The audience soon realizes that David has telekinetic powers that enable him to make kitchen explosions. Further probes, of course, using online explainers, reveal that his experience is about the process of psychotherapy and treatment, which as the show indicates, is engaging and vigorous.

Complex TV is unique for its cinematic and novelistic features, which are compliments accorded to it by media pundits. However, the medium has significant aesthetic accomplishments that are worth noting. The first one, which is also an artistic breakthrough, is that it has created an active and engaged community of viewership that has an equally ubiquitous online presence. Although other modes exist to be used in television storytelling, complex television functions majorly within the several choices of locating story-worlds, characters, time, and events in continuing serial and episodes. The goal is to reflect a world where the imagined and the real are not so far apart.

0 notes

Text

ART OF THE CUT WITH Martin Bernfeld, editor of ӈellboy

Editor Martin Bernfeld in the cutting room for Hellboy.

Martin Bernfeld has been editing features for 15 years, including Project Almanac, Paranormal Activity: The Ghost Dimension, Power Rangers, The Babysitter, and Bent.

For this interview, I talked with Martin about his latest film, Hellboy.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: What was post-production schedule like? When did they start principal photography?

BERNFELD: They started shooting Hellboy in the middle of September 2017 in Bulgaria, and I was hired at the end of October. So I jumped on a plane after getting the call that I was hired on the film and had quite a lot of dailies to catch up on.

Editor Martin Bernfeld, on location in Bulgaria

I edited in Bulgaria through the finish of shooting and stayed another week after they wrapped to finish the assembly. We relocated to London after the Christmas break to start the director’s cut through picture lock.

While we were originally scheduled to finish at the end of November, it carried through into January making it one year and four months of post.

HULLFISH: How did you and the director get connected on this project?

BERNFELD: I interviewed for it, set up through my agent. I talked with Neil and Lloyd Levin one of the producers. I liked what they said about the direction and vision there was for the film.

While it was tough to start in the middle of production, Neil and I managed to spend some lunch breaks having more in-depth conversations about what he’s looking for and make sure we were on the same page before attacking dailies.

HULLFISH: Did you bring your own editorial team to Bulgaria?

BERNFELD: I wanted to, but they had already had two Bulgarian assistants that were organizing the footage ready to be edited. I used those assistants during principal photography and hired a new editorial crew when moving to London. It was a great team. Luke Clare was my first assistant and Gemma Bourne was the second. I didn’t know them prior, but they all came highly recommended from other editors.

vimeo

HULLFISH: Well, this is obviously a big VFX movie. You did Power Rangers with Dody Dorn. Dody and you and I talked about that movie when it came out. How does your VFX background help when it comes to editing a movie like this?

BERNFELD: I do have a fairly good understanding of the VFX process: what you can and can’t do and how to achieve what you are looking for when you have to reimagine or rethink sequences editorially. We also had a strong VFX supervisor — Steve Begg — He and I had a very tight working relationship. There was one specific sequence — the giant fight — that needed some rethinking. It was designed to play as one long shot. When all the takes were stitched together to achieve the one shot, it was running at 7 minutes which is obviously too long and too slow. We were aiming for a 2.30-3min action sequence that had the energy and pace we wanted. I had to work out a way to keep the same action and get it into the 2.30-3min and still maintain the concept of the oner.

David Harbour as ‘Hellboy’ and Sasha Lane as ‘Alice Monoghan’ in HELLBOY. Photo Credit: Mark Rogers.

That’s where having a good understanding of how to best integrate a digital camera takeover helped the process of eliminating time and communication with the VFX supervisor to find a way to shorten the scene.

For example, I took the profile shot of Hellboy running and shortened it by adding a camera whip pan to a full CG shot revealing the giant. From there the camera booms down into another plate of Hellboy, which tracks with him running up the giant and going in for a punch, this plate was also reduced significantly.

Other stitches were more complicated in execution, but the same concept. However, there were a few beats that we felt landed better and were funnier when cutting to them directly, so we deviated from the one long shot concept. At the end of the day, we had to do what was best for the movie.

At the mix for Hellboy.

HULLFISH: So you have to have the imagination to come up with something interesting that tells the story, but understand the restrictions of what can be done with what was shot.

BERNFELD: Right, because Hellboy (the character) is not full CGI. David Harbour was in makeup and the suit rolling around and punching blue placeholders as a representation of a giant. You have all these interactions that need to tell the story that’s in the script or previz. It was a challenge, but it’s a fun little ride.

HULLFISH: I would think your Power Rangers experience would have given you a great background for having to do that.

BERNFELD: Absolutely. The whole third act in Power Rangers is practically one long action sequence and 90 percent CG. Working with empty plates of a location, with the opportunity to add anything you want, makes you focused on how animation can help you tell the story and timing of VFX shots. A shot of an empty plate with no monster can feel very long in an action scene, even with rough animation. But once the shots are finished you need more time then you think to register the action, so not cutting the action so tight at an early stage helped me when approaching some scenes in Hellboy.

I worked on a few lower budget films with complicated VFX, before Power Rangers, and those budget restrictions train you on how to be more specific and creative in what you need to tell the story within the means you have.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk a little bit about the importance of being able to collaborate with people — having the type of personality that allows you to give-and-take with the director, with VFX people, with assistants…

BERNFELD: I feel collaboration is essential to the post process. When I hire assistants, I try to find people who like to be part of a team. Someone who takes pride in their work and wants to take ownership of the task I give them, whether it is sound work or temp VFX. I want them to feel involved in the creative process, and that they are very much part of the movie.

Personally, I always try to stay positive and optimistic regardless of what situations and demands are thrown at Post, and I try and hire assistants that do the same. They are the first line of contact, so representing the cutting room well I feel is important.

Same when it comes to the director, producers or the studio. I want them to know that I’m in it with them, we’re one team. We’ll take every note into account and do whatever needs to be done to make it a great movie. I believe as an editor that we are there to help create the director’s vision of the film with every tool at our disposal.

HULLFISH; Sounds like something you might have said to the director in your interview!

BERNFELD: Yes! I do stress that in my interviews. I like to collaborate and get any new ideas. There never a bad idea; every idea can lead to a good one.

HULLFISH: Tell me about the nuts and bolts of looking at a scene when you’re looking at a blank timeline and a bin full of dailies for a scene. What is your approach? How do you handle that?

BERNFELD: First, the dailies get organized by my assistants. I like to have my bins in Frame view, and they’re all organized in script order. It doesn’t matter where the slate lands alphabetically. Q can come before A (in the lettering of the camera set-ups). Then a KEM roll is created where I view my dailies from. As I watch the takes I cut my preferred line readings and moments into a selects sequence. Once I’m done going through all the footage from the given scene, I reorganize that selects sequence into the scripted version of the scene and then I start whittling that down into my first cut of the scene.

Avid timeline screenshot from Hellboy. To see more detail, option-click on the image and choose to open in a new tab. From there you can zoom in.

I don’t always edit from the beginning through the end. When I’m watching the dailies, I keep a close eye on certain beats that I feel will be pillars of the scene, and will build out the sequence around those. I let the moments tell me where I need to be.

Editorially — when I construct the scene — I always think back to the staple five questions: Where am I? Why am I here? Where have I come from emotionally? What does the character want in the scene? and “What’s the goal of the scene and what does the scene really need?”

Those questions are lingering in my head when I watch all the dailies and I always look for those small nuances that will give me those answers to best tell the story.

HULLFISH: So when you’re watching your KEM roll, you are actively pulling stuff out as you see it?

BERNFELD: Yes, but one key step before I start pulling material is to re-read the scene from the script first. That gives me a fresh memory of the beats and nuances in the script so I don’t overlook any of those important moments.

Having those in mind also helps me spot if something isn’t coming across clearly in the shot footage. I can report back to the director to get their thoughts to find a solution. Either we pick it up when possible, I look for an editorial workaround, or perhaps it was purposefully left out and then I can continue without that moment.

When I approach a scene, I like to build out every single beat in the script and don’t focus too much on running time. Multiple times I’ve gone back to my assemblies in month eight or ten of cutting and brought back that built out beat after we oversimplified a scene or need to highlight information. I like this approach because it enables me to go back and pull small ideas that I created. I find it helps to have a strong backbone of an assembly.

Milla Jovovich as ‘Nimue the Blood Queen’ and Penelope Mitchell as ‘Ganeida’ in HELLBOY. Photo Credit: Mark Rogers.

HULLFISH: Do you remember the length of that first assembly? And did you even bother to watch the assembly all the way through?

BERNFELD: I watched it and it was too long, but you could get a strong sense of where to focus first. I think it was about two hours and forty-five minutes.

HULLFISH: What are some of the things that you and the director found as you started to watch things in context and how things changed when you did see scenes next to each other?

BERNFELD: We focused primarily on pacing and getting the movie down to a proper length. We had conversations about the structure and where we were trying different placements for different scenes to help the pacing and storytelling.

HULLFISH: Were there structural changes?

BERNFELD: The opening scene got shuffled around a bit. It was the introduction to Nimue (Milla Jovovich) and sets up who the villain is; what her powers are; and what the threat of the movie is going to be. We tried it in four different places to see if there was a stronger way to introduce her. When we put the introduction later, she became not as important and threatening so in the end, so we left it where it was scripted. But we had to try all the options, and assess what is best for the story. Trial and error are one area of editing that I love and feel are important to the final product.

Once we settled on where it belonged, the other factor we had to manage was the duration. It was a heavy dialogue-driven scene, with the assembly version at seven-minutes long, and we brought it down to a five-minute scene. But once we previewed, the audience wasn’t responding to it as a prologue, so we decided to try a narrative by Ian McShane. It ended up as a two and half minute introduction of the character, which worked better for an audience and to get to Hellboy earlier.

Because the script was fairly linear in order of events, there wasn’t a ton of opportunity for restructuring. However, we did move one scene about our secondary villain called Gruagach, a talking pig. We delayed his finding of Nimue’s head so we could get into Hellboy’s story and live with him before starting the two parallel stories.

David Harbour stars as ‘Hellboy’ in HELLBOY. Photo Credit: Mark Rogers.

HULLFISH: I love the solution of cutting down the opening villain introduction by writing some narration and doing some ADR which allowed you to shorten the scene in ways that I’m assuming were not possible by just eliminating dialogue that was already spoken.

BERNFELD: We tried it many different ways. We cut the scene as tight as possible with the only dialogue needed for exposition, but that turned it emotionless. So a better way was to go with narration which also gave us the opportunity to play with the tone for the movie.

HULLFISH: Were you able to pull previous music cues or sound effects from previous movies to be able to temp out this movie?

BERNFELD: One conversation that I had with Neil and Lloyd the producer before I started editing was that we wanted a very different approach to tone for this movie. So we deliberately did not use any temp score from the earlier movies, or original sound design. We wanted to make this became a more grounded version. Very early on we talked about Hellboy being an old-school rocker which brought us to our music needle drops living in the rock world.

After screening it, there were discussions about the classic rock choices, so we took a stab at modernizing the soundtrack — like Kanye West. However, after our recruited screenings bumped a bit on the modern music, we went back to the old-school rock and roll, since that is in the DNA of Hellboy’s character and what people were looking for.

HULLFISH: When picking temp scores, how did you choose which ones to consider?

BERNFELD: I like to listen to a wide variety of scores and pull from every movie imaginable, I find that this gives a fresh idea for the music. The challenge is to keep the musical tone as consistent as possible. We mostly used The Mummy, Alien, The Descent, and we also snuck in some Under the Skin and JFK.

HULLFISH: JFK? Wow!

BERNFELD: I know! It’s different, but it suited the scene! We also used Gone Girl for some of the more modern tonal cues.

We were lucky to have our composer, Ben Wallfisch, join very early in the process, which made a big difference to be able to edit the movie with the music that will be in the final film. We had several conversations with Ben about the tone, wanting to make this a different sounding movie. He was really excited about trying something completely different.

He made us a couple of musical suites we could work with: a hero suite and a villain suite. As his demos came in for the individual scenes we stripped away all the temp so we can work with the new tracks and give him feedback. He would come back with revisions as the edit evolved and made an amazing score for the movie!

HULLFISH: Also I would think with something that is very unique and different you run the risk of having temp love on stuff that you’ve listened to that his stuff might be great but because you’ve listened to something so different for so long it doesn’t want to stick.

BERNFELD: We really considered that not “falling in love with temp” because the last thing we wanted to do was not give Ben the opportunity to give us something completely different.

HULLFISH: Nuts-and-bolts-wise, with the suits that he gave you, was he giving you stems of some kind so that if you wanted to use the theme without the full orchestration you could?

BERNFELD: He didn’t actually, he provided us a mix of the cues. I worked closely with the music editor, Tony Lewis, to modify cues as the edit evolved — obviously with Ben’s involvement throughout the whole process.

We had the same approach with sound design, which also started early on. This was done by Phaze. We had a lot of conversations on how the different creatures and environments should sound like. We tossed design stems back and forth throughout the whole process to develop the sounds, so by the time we got to the mix stage we didn’t spend the time developing or changing ideas. It was just a matter of mixing it. That proved to be very helpful because we had a limited time to mix the film.

HULLFISH: How are you managing the replacement of your early sound design that you did with the stuff Phaze did?

BERNFELD: Phaze always gave me stems split into backgrounds and hard effects, so I could take what they had done and manipulate it and add new ideas. I like to communicate with ideas in the timeline, having a representation of what I’m looking for helps me convey my thoughts that they can then take and expand on and make better.

HULLFISH: Are you doing the same process with the VFX stuff?

BERNFELD: Yes, I like to have temp comps in-house for timing purpose. Once VFX shots come in, I always keep three iterations of the shot in the timeline including the temp comp that we did in-house. I always like to have a quick reference of the shot’s progress when things move fast and you are dealing with over eighteen hundred visual effects shots. Towards the end, we had approximately 100 shots a day coming in that needed to be looked at and given notes on. Sometimes you don’t catch everything in the immediate, that is when it’s helpful to have a quick history of the progression. If I always wipe my timeline clean it takes a longer time to find older versions and compare iterations. So my timeline can become quite big, up to eight or nine video tracks.

HULLFISH: What about audio tracks? Do you have a limit on how many you like? Do you keep a bin of your favorite D-Verbs and audio effects?

BERNFELD: It depends on the movie, but on Hellboy, I worked with 24 audio tracks: four dialogue tracks where I add EQs, compressor and De-esser on them for the dialogue to sound crispier and punch through better. Then I have my mono sound effects and my stereo sound effects and my music tracks, then two mono and two stereo tracks that have the universal D-Verb effect on it.

Milla Jovovich as ‘Nimue the Blood Queen’ and David Harbour as ‘Hellboy’ in HELLBOY. Photo Credit: Mark Rogers.

With my D-verb tracks, I can quickly add ringouts to either Dialogue, SFX or Music, to make transitions sound better without constantly rendering. The track has as much ‘verb as possible, which I control by how much volume the segment has.

The D-verb tracks have been a huge asset for scenes that take place in large spaces. For example, in Hellboy, there is a full dialogue scene that takes place in a church.

In addition to keeping the dialogue on its original tracks, I also mix it down and put it on my ‘verb track. I can then watch the scene and with the use of my Avid Artist Mix – I can easily record and change the volume as the scene goes on — how much ‘verb I want — because it changes based on how close you are to characters and based on the emotion of the scene.

HULLFISH: Wow that’s pretty cool. I never heard anybody talk about doing that before. That’s pretty interesting. Let’s talk about a couple of specific scenes that I have access to — the Father/Son Scene in the Osiris Club.

vimeo

BERNFELD: I really loved that scene because of its simplicity and how it focuses on the two characters and their father-son connection and relationship that is the basis of the movie. It also allowed for their banter to shine. Ian McShane played a more tough dad role, and David Harbour conveyed Hellboy much more of a teenager — a lot of attitude and insecurities. It was fun to cut together because of their wide range of performances they gave. And that doesn’t pertain to this scene only, in every single scene David Harbour constantly gave options to play with so you can go in whichever direction you wanted.

HULLFISH: At the beginning of our conversation, you talked about the questions you always ask yourself as you’re going through a scene. What would that internal dialogue have looked like on THIS scene?

BERNFELD: Where and Why? Since this is a new location, I had to make sure we establish the setting and convey Hellboy’s emotional state.

Where are we emotionally? Hellboy just killed his friend, so I wanted to continue that emotion and sadness going into his bedroom shaving his horns. Broom, his father comes in to comfort his son with tough love.

Broom’s agenda? He is the head of the BPRD and wants to send Hellboy on another mission to help him, the only way he knows how.

The goal? To establish their relationship and show Hellboy asking what the words his friend told him before he died meant. Ian quickly breezes over that and says its nonsense, but clearly, he knows what it means and doesn’t want to tell Hellboy. This is important as this is the theme and backbone of the movie.

HULLFISH: You almost need a sense like an actor would have of: what’s my motivation? Where does my character have to go? What do I have to reveal in this scene so that some other scene, later on, makes sense?

BERNFELD: Absolutely. That’s what I love about editing. You get all the pieces and it’s sort of like a little sandbox that you can start playing in. What nuances that you — as an editor — find intriguing and what emotionally brings something out in you when you’re watching the dailies.

HULLFISH: What about the “Arrived” clip?

vimeo

BERNFELD: This was a pivotal scene where our villain and hero meet each other. Nimue tries to persuade Hellboy to join her side, be a king and rule the world, yet he doesn’t want to. In order to emphasize her motivation and why she didn’t just kill him when he refused, we tried out a lot of additional dialogue to clarify. We cut the new dialogue with over-the-shoulder and wide shots. But in the end it turns out we didn’t need as much to explain her motivation, the audience got it. So we ended up stripping a lot of that away. I kept a couple of small couple lines and the scene turned out better for it.

HULLFISH: I love the idea that landing on the final solution for this scene was a process. It needed to go through iterations.

BERNFELD: Definitely. That’s why I like to make my assemblies as good as possible, well knowing that it will change, but if I put everything in there then I don’t have to go back to dailies as often to find or recreate beats. I can pull from my assembly and quickly put together a version that combines the old with the new and refine as necessary. I then circle back through dailies again to make sure there isn’t a better performance or different line readings if the intention has changed.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that a lot of times you would make a version and then move along and then come back to an old version you did. What kind of organizing are you doing in your bins and in your project to be able to find those previous cuts of scenes quickly and easily?

BERNFELD: I keep my first couple of versions in my scene bins where I have my KEM rolls and my selects. I like to keep everything in one place.

HULLFISH: Once you start making revisions those are someplace else? They’re in the reel?

BERNFELD: I usually edit the revisions in the reels so I don’t have too many subsequences to keep track off. I have a bin with ideas and structures that I try, which I might come back to at a later stage if needed.

HULLFISH: Do you break the film into reels once you’ve done your first assembly? Or you break it into reels right away as you are assembly the scenes?

BERNFELD: I put the full assembly together and then divide it into reels.

HULLFISH: Martin, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me today.

BERNFELD: Thank you, it was an absolute pleasure speaking with you too!

Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors