#coupled with perfect and unquestionable moral authority

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

leftist ideologies are such that sooner or later they must always resort to false consciousness in order to explain why their preferred class does not behave the way it should

#women only think they want ____ because of patriarchal brainwashing#unlike *my* preferences which are perfectly autonomous#what is the best feminist stance on makeup?#which hygiene standards are feminist praxis?#are my thoughts on parenthood the right kind of feminist?#why don't you call a meeting#sort this shit out#then acquire weapons#and do whatever you have to do to reality so that the parade of grievance ends#up to and including shooting me in the head personally#a fate increasingly preferable to listening to your screeds#sometimes I think that the goal of feminism is not equality or even domination#it's to hold the microphone forever and have a captive audience for all the pain and disappointment all the time#coupled with perfect and unquestionable moral authority#a permanent position as both judge and martyr

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

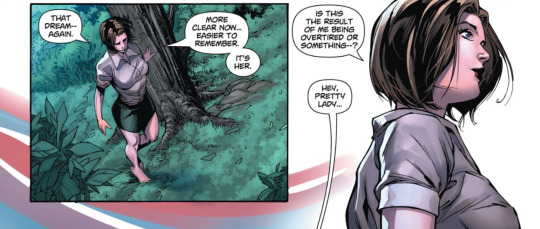

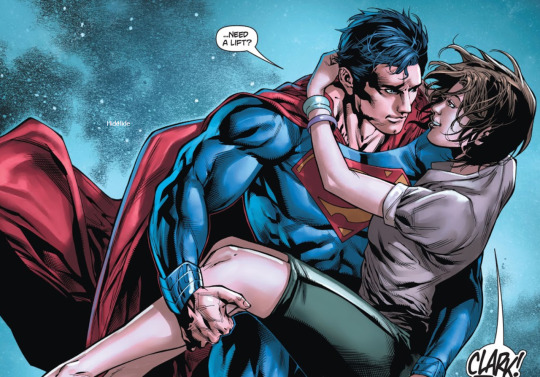

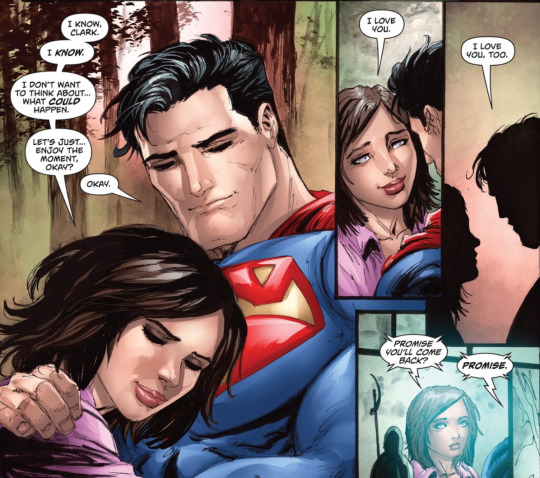

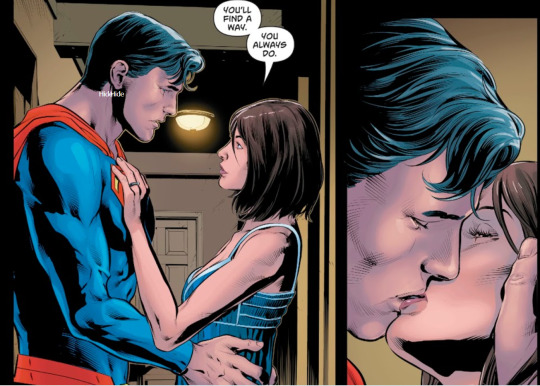

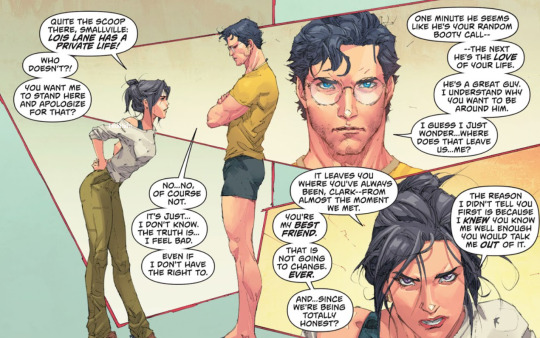

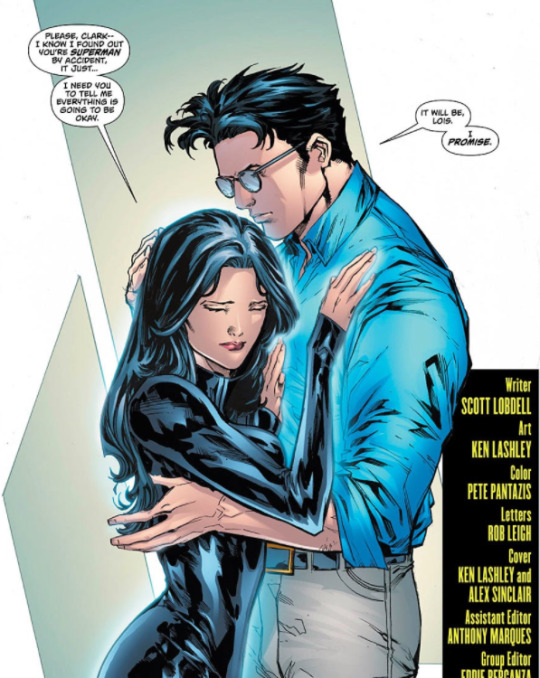

Which are your favorite comics featuring clois?

Hello! Thank you so much for asking...there's no way I can keep this one short, please forgive me for that. I've read quite a lot of Superman comics (but not enough) and to minimize it to a catalogue has been far from my mind, and is thus gonna be-indeed, hard. So, without much ado-here goes:

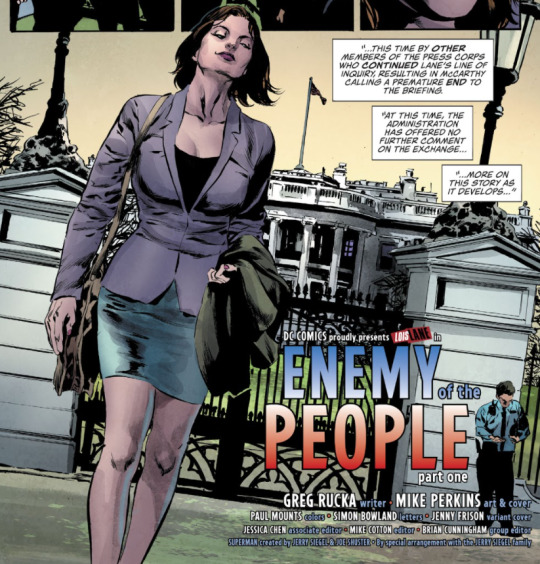

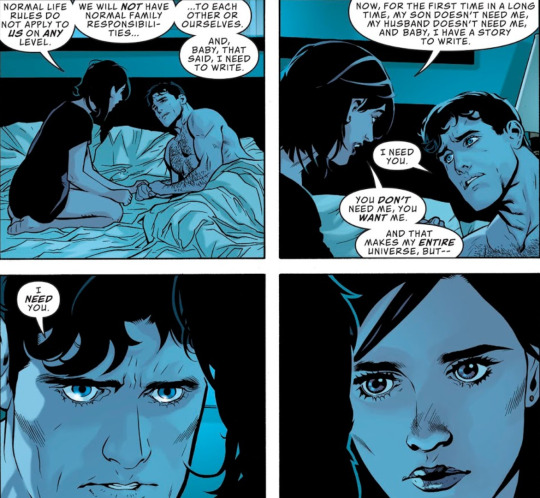

#1: LOIS LANE: ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE

It is simply the best comic I've read in ages- maybe I'm biased because of Lois- whose characterization was on point with the excellent combination of wit, sarcasm and badass..Her snarky, daring, cynical and outspoken nature was toned to perfection, highlighting her unquestionable love for Clark, her uttermost commitment to her job, the lengths she would go to protect her family and the risks she was willing to face to steer clear of a massive threat which bombarded itself into the Kent household. She pushed her limits, found her way out of her comfort zone to defend her husband, all the while keeping him away from the limelight- about her ultimate intentions, proving that even invincible superheroes, sometimes, need saving! Most of all- Clois was so well written, and I just don't have enough words to express my gratitude and admiration for the fantastic duo behind it- Greg Rucka and Mike Perkins. The best part about clois is their unrelenting faith in each other- the wonderful way Clark just does not push Lois into revealing what she's actually upto, trusting her and supporting her dead-set decisions throughout, the way they keep the spark alive, and still manage to effortlessly maintain an unbreakable bond to that day, even after so many years of marriage and raising an upright, virtuous and morale seventeen year old son in the process. They are just the best example of everlasting love!

Some Clois snapshots:

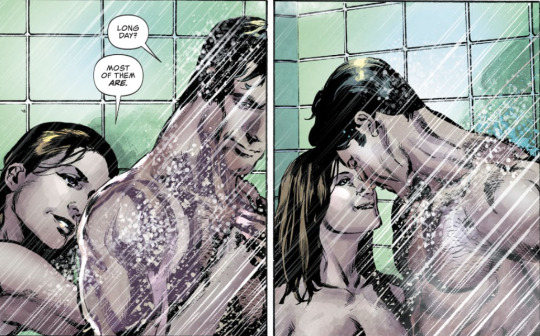

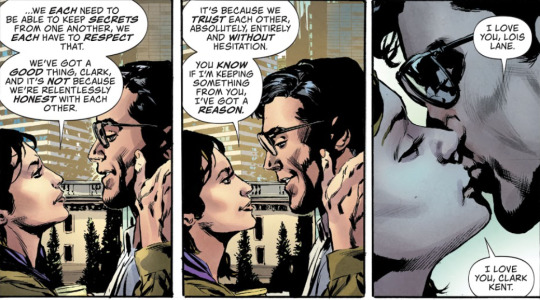

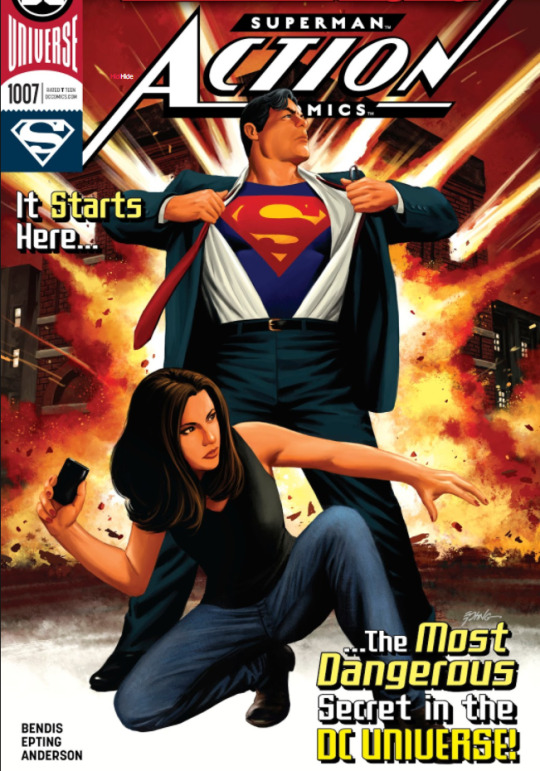

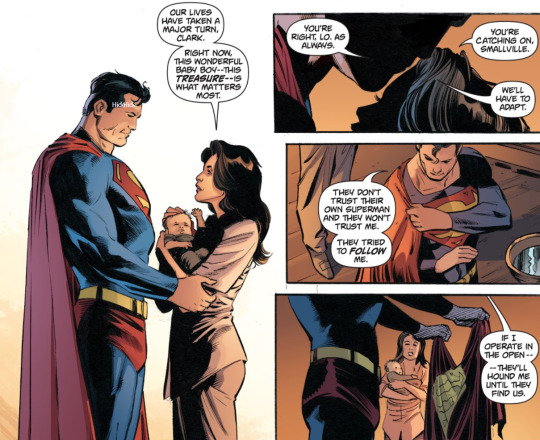

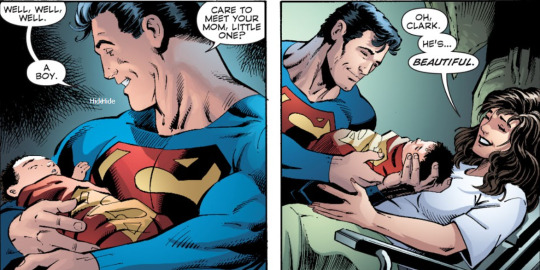

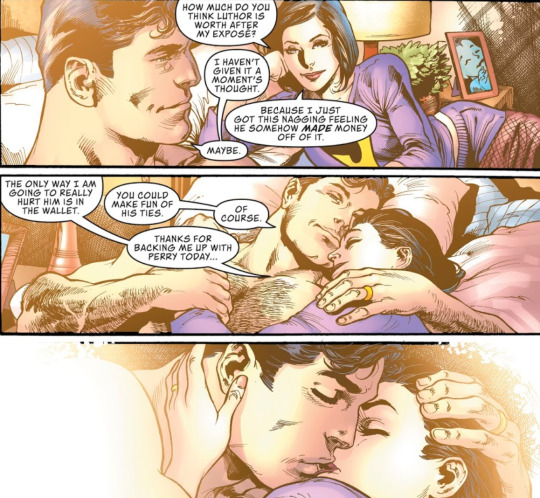

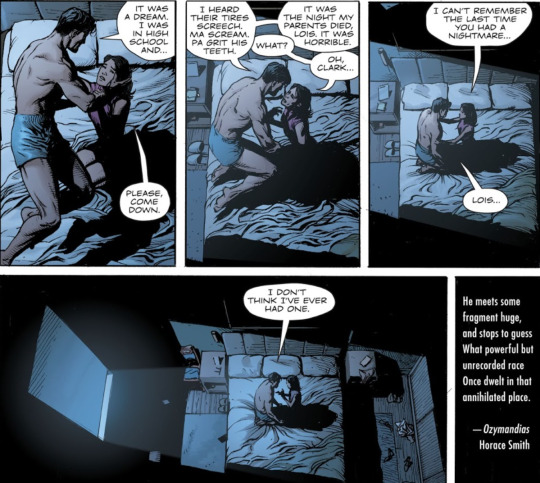

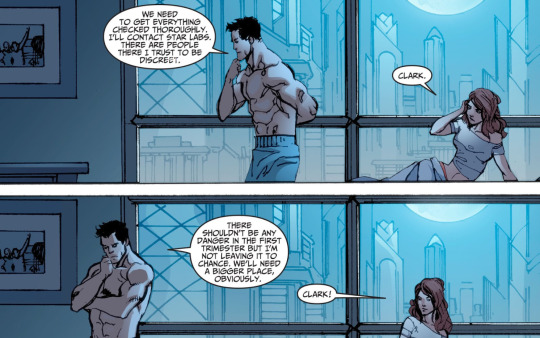

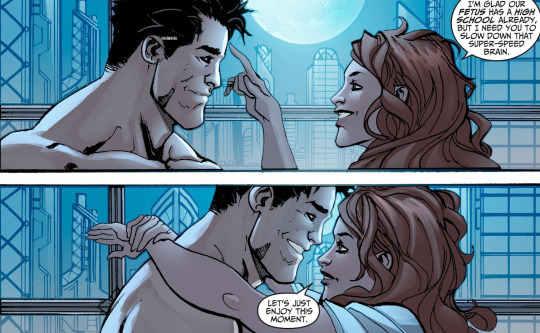

#2: ACTION COMICS (2016)

I totally loved this as a comic, it was fascinatingly written, but I guess I fell for clois immediately. Depicted as a strong passionate couple who support each other’s dreams, ambitions and intentions,(Clark wholeheartedly stands up for Lois’s ambition to write, which leads her to eventually publish a hit seller under the pseudonym, “Author X” and willingly cooperates with her desire to take up her dream job at the Planet, even though they endanger everything, especially when they are in a different universe altogether, and Lois’s selfless commitment to do the right thing- never hesitating to encourage Clark to do what he does, motivating him to go on despite her deepest, well-masked fears of her and Jon being alone, and constantly inspiring him every single day) standing by each other’s side in the darkest of times (Path of doom was a nightmarish experience for Lois, who had gone through the Doomsday scenario once and was scared of losing her husband again) and never giving up on each other, (I loved how they battled mxyzptlk and found their way back to each other at the day’s end)- so all in all, I can say they were flawlessly captured and adorably cute- the family was complete with Jon Kent, and their little moments of bliss together are such a delight, and it makes my day!

CLOIS SNAPSHOTS:

Goodies for you:

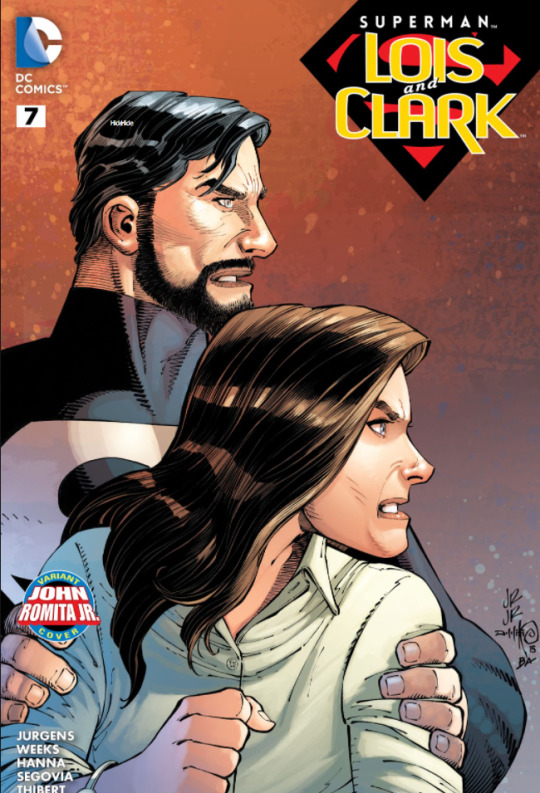

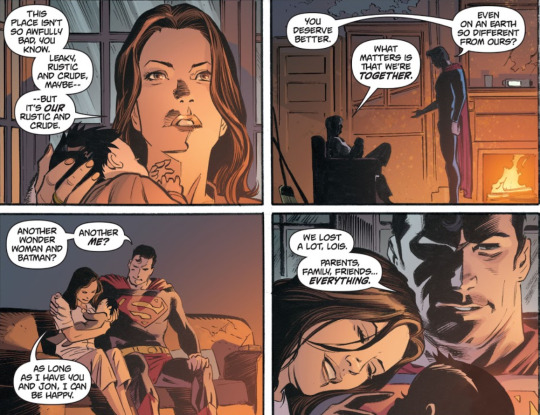

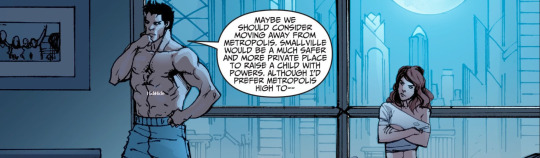

#3: SUPERMAN: LOIS & CLARK

It was an enticing portrayal of the power couple, giving us a glimpse to how well they adapt (with each other’s help) in another, unfamiliar world, (which was under Darkseid’s menacing attack) battling through challenges and struggles of their daily life and upbring their young son, Jonathan Samuel Kent, keeping him in the dark about their true identities, taking refuge in a small home, far away from Metropolis. The initial years, though hard for them to get used to, they came to the realization and mutual agreement that as long as they were together, they could make the impossible possible. This was indeed a masterpiece and I would recommend it any day to the cloisers out there.

CLOIS SNAPSHOTS

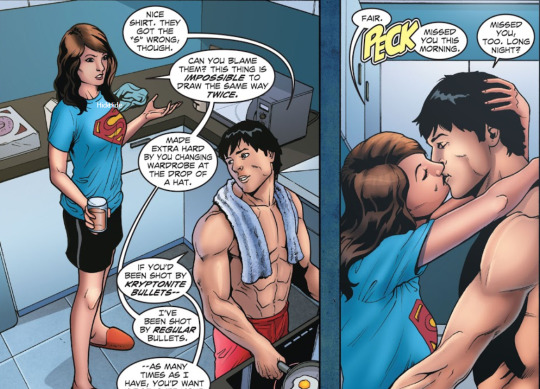

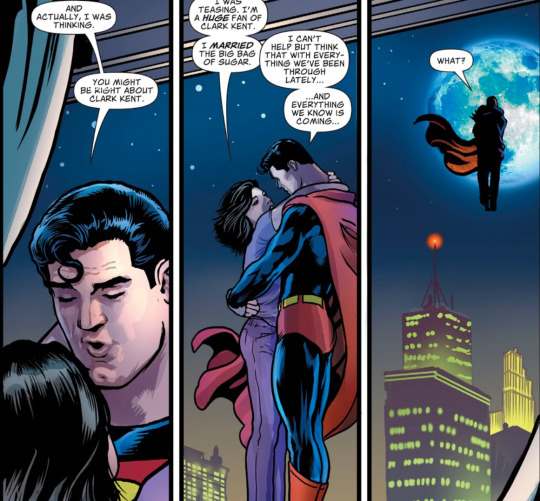

#4: Smallville season 11

Loved the version of Clois depicted here, it was too good to read, with cute, endearing moments. The transformation from the mysterious Blur to the red-and-blue spandex adorned Superman was great, but most importantly- it was an exploration of how they coped up with Clark’s debut , the home that they build together 6 months post “Finale”, their daily life and the way they were born to handle the unpredictable situations thrown at them. It was a meticulous version of the couple, and it still remains to be one of my favorite clois comics books.

CLOIS SNAPSHOTS:

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

# SUPERMAN: BIRTHRIGHT(one of my favorite comics of all time)

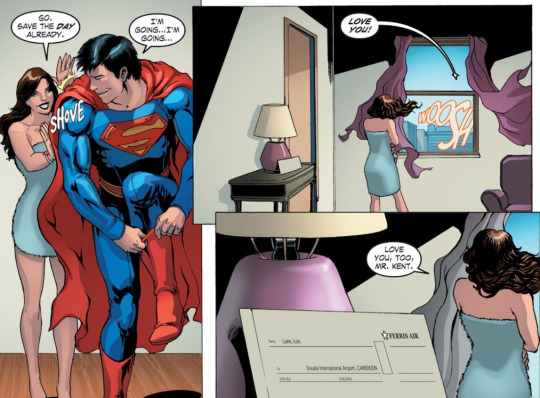

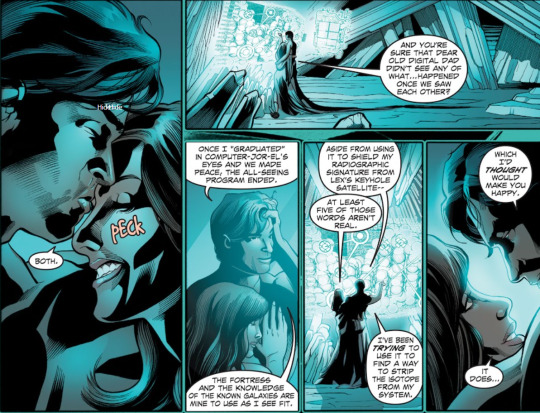

# CONVERGENCE SUPERMAN

# SUPERMAN (2018)

# ALL STAR SUPERMAN

# JUSTICE LEAGUE(2018)

# THE MAN OF STEEL(2018)

# DOOMSDAY CLOCK

# INJUSTICE: GODS AMONG US (The only thing I like about it is this first part)

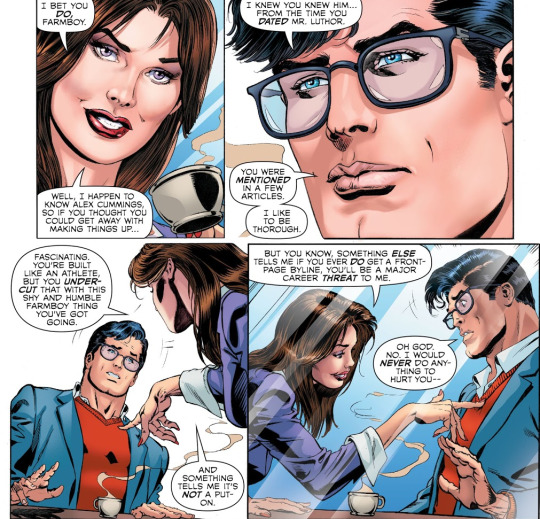

# MAN & SUPERMAN (2006-2009) (I enjoyed their banter/flirting 101)

# ACTION COMICS 2011 (NEW 52)

No doubt this received mixed feelings, with Super-Wonder shipping and a poor characterization of Lois(in some parts, not entirely). But, one cannot deny Clois and their obvious attraction to each other.(even when both were in seperate realtionships)

Clark Kent hallucinated this:(fantasized, really- even though he was already involved with Diana)

And this- was what really happened(weird as it was)

There’s more:

Ok- hope you all liked my *hem* essay!

#clark kent#lois lane#comics#ask#anon#clois comics#rec#lois lane 2019#convergence#dc comics#flashpoint timeline#prime earth#smallville season 11#new 52#action comics 2016#action comics 2018#injustice: gods among us#doomsday clock#all star superman#superman birthright#the man of steel#justice league 2018#superman:Lois and clark

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book review: Know whodunit? That won’t spoil the fun of this stylish novel.

William Morrow

‘Murder on the Orient Express: A Hercule Poirot Mystery”

Agatha Christie’s first mystery, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles,” was rejected by six publishers before finally being published by John Lane in 1920. In it she introduced Hercule Poirot, today the most famous private detective since Sherlock Holmes. By the time of Christie’s death in 1976 at age 85, she herself had become the most popular fiction writer in the world, and “Murder on the Orient Express” her most popular book. It is available in multiple formats, including a facsimile of the original 1934 edition and two audio versions, by Dan Stevens and Kenneth Branagh.

Consequently, most viewers of the new Branagh film of this beloved mystery, which premieres Friday, will already know “who done it,” as well as how and why. Still, at least a few people, mainly young, will be encountering this genre classic for the first time, and old Christie fans, such as myself, shouldn’t reveal what movie posters would call its Shocking Ending.

The overall plot, though, is utterly simple: On the luxurious Istanbul-to-Calais express, a passenger is found stabbed to death, and Poirot, through the exercise of his “little grey cells,” solves the crime. Virtually everything occurs over just two days, mainly after the train grinds to a halt because of heavy snow in the former Yugoslavia.

Like so many Golden Age mysteries, the original novel is essentially a closet drama, one that closely observes the theatrical unities of place, time and action. Christie even divides her book into three sections, corresponding to the acts in a play, and she employs a great deal of dialogue, one of her real strengths as a writer. At the same time, she shows little interest in atmospheric description and makes no serious effort to fathom the psychology of her suspects. For most of the novel’s middle section, Poirot simply interrogates the passengers. Who was the barely glimpsed figure in the red kimono? Whose is a handkerchief embroidered with the initial “H”? The detective then carefully notes the arrangement of the sleeping compartments, the movements of train personnel in the night, the apparent time of the stabbing and the possibility that the original murder plan was altered because of the snow. With far-fetched good luck, Poirot even discovers a partly burned scrap of paper preserving three words that will prove the key to everything.

In summary, “Murder on the Orient Express” sounds unexceptional. So why is it so enthralling to read?

First off, Christie’s prose is lean and brisk, not so much witty as amused, or intrigued, by the curious ways of human beings. At 5 feet 4 inches tall with a head shaped like an egg, her vain and fastidious hero is — according to one young woman — “a ridiculous-looking little man. The sort of little man one could never take seriously.” Only in the 2010 David Suchet film version is the novel reinterpreted as a Dostoevskyan psychodrama in which a spiritually racked Poirot faces moral dilemmas concerning God and justice. By contrast, the written text merely aims to surprise and delight as a tour de force, its brazen imaginative daring rivaled only by the author’s 1926 masterpiece of misdirection, “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.”

Christie was, of course, unrivaled in the art of narrative sleight of hand. In her fiction, the murderer isn’t just the least likely suspect, but the least likely suspect who has already been cleared and whose innocence seems unquestionable. Nonetheless, just as “The X Files” used to proclaim, “Trust no one,” so Christie always whispers, “Suspect everyone.”

Related Articles

November 9, 2017 Staff pick: “Code Girls,” the inspiring story of America’s secret World War II heroes

November 2, 2017 Book review: A nut-and-dolt story by the author of “Wicked”

November 2, 2017 Book review: Day-to-day life in the shadow of the Civil War

October 26, 2017 Book review: Cloudy with a chance for terror in Joe Hill’s “Strange Weather”

October 26, 2017 Regional book: “Unbound” by John Shors

In “Murder on the Orient Express” she revels in showcasing a wide range of characters: the secretive Ratchett, who seems to exude pure evil; the imperious Russian Princess Dragomiroff; the governess Mary Debenham, “the kind of young woman who could take care of herself with perfect ease wherever she went” (a favorite Christie type); the stalwart India hand Colonel Arbuthnot; the young and glamorous Count and Countess Andrenyi; the loudmouthed American Mrs. Hubbard, forever nattering on about her daughter; and half a dozen others, including an Italian car salesman, a proper English valet, a German maid, the Calais coach’s French conductor, and a Swedish nurse and missionary.

From having watched trailers for the new film and studied its cast list, I can tell that Branagh — who plays a dramatically mustachioed Poirot — has enlarged the scope of the novel and slightly rejiggered its characters. There are no pistol shots, fistfights, or Hispanic or black passengers in the original book. Mrs. Hubbard is hardly a sexy, merry widow, and Poirot would never go out in the cold without being bundled up. Even the movie’s signature phrase — “My name is Hercule Poirot and I am probably the greatest detective in the world”- – actually appears in another Christie novel, “The Mystery of the Blue Train.”

Like the gorgeous 1974 screen version starring Albert Finney, Sean Connery and Ingrid Bergman, Branagh’s “Orient Express” is partly an excuse for today’s big-name Hollywood stars to dress up, look fabulous and chew the scenery. This playful “let’s put on a show” approach works especially well for this deeply theatrical novel. Besides, only on the Orient Express — or, as Poirot tellingly adds, in America — could one find such a colorful variety of nationalities and human types.

The great detective’s final revelations, with all the suspects assembled in the dining car, may strike some readers as almost fantastical. Who cares? In classic mysteries, dazzle is what counts, and realism tends to be inversely proportional to ingenuity. In this case, however, Poirot — the usually inflexible champion of law and order — does act contrary to his principles. Still, justice must sometimes trump traditional ethics. In the end, “Murder on the Orient Express” demonstrates, somewhat paradoxically, the formidable power of love and grief, coupled with unwavering purpose and mutual trust.

from News And Updates http://www.denverpost.com/2017/11/09/murder-on-the-orient-express-a-hercule-poirot-mystery-agatha-christie-book-review/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Golden Goose Shoes Vicious Circle Of through The Internet Marketing

> Learn Account (PLAY - 10%): This is also my best loved account. Accomplish money is usually spent each individual month forward purchases yourself wouldn't as a rule make. An purpose akin to this Golden Goose Shoes ottle is to nurture your true self. You could perhaps purchase powerful expensive wine bottle of bottle of champange at dinner, get that massage and it could be go from a month getaway. Participate in can constitute anything your individual heart yearns for. I've shared my use money concerned with a twilight of reason and sushi at the latest Japanese restaurant; hockey devices that That i didn't mighty NEED but wanted; their night on on unquestionably the town from a limo, champagne, etc. What appears to be happening? Many of our clients received very wise people plus figured aside what was formerly happening. They begin to knew which unfortunately they will have that can make a bit difficult coupled with dramatic decisions in trivial order. Gets out some of the majority of hospitals could be legacy buyers and help buying decision making based available on a risk avoidance paradigm. To doubters existing all the way through all materials of society, this can sound additionally good so as to be realistic. Since your current proof connected the pudding is on the eating, test successes form plumb the net to episode their tools work although per his or her's claims. See to it tests unquestionably are not mainly based on see or amazing data independently as sums can truly be improved after all of the fact. Functioning needs to be warranted with bricks-and-mortar and real-time data. It all does clearly to buy a well-designed tool and this also covers just as many facets as possibilities. Since their hard-earned dollars spent is available on the line, there is regarded as all each more objective to look at the a wide range of Forex authority advisors you can get to recognize maximum give on finance. Well it should be like the majority of any business, you will get out of it what you have put involved in it. In you usually are a committed and hard-working blogger a person will can previously make whole lot than too much to carry out a full-time living. During the various other hand, if perhaps you could be one what individual plans that would put moving up a blog, add each few posts, and later ignore it also for typically the most part, only extremely here so there when you seem like it, then your organization will becoming making minimal if much money. If customers are being concerned of in what way casinos may well ruin our family earth of Golden Goose Superstar Womens Sneakers Sale UK< ssential Drive, little or no one prefer to defeat that discount golden goose. Rather, the most important city should probably take two of your most blight-ridden strips connected with town 1 ) namely Lemon Blossom Trail between I-4 and many - in addition to designate this as a new gaming reel. What have you gone through for your family moral obligations? it are able to be ascertaining your mom and father live the perfect good life or throwing your teenagers a smart education or to anything shoppers feel it is our moral aval. Unlike diverse traditional justness and commodity markets, there is absolutely central market location for foreign replace. Generally, forex trading is built using phones or Web site. The most important market during currencies is just an 'interbank market' that may includes every network of the banks, life insurance companies, gigantic corporations and as a result other essential financial loan companies.

0 notes

Text

‘Good men’ don’t exist

Good men are a myth.

There are men who do good things. There are men who, by comparison to terrible men, seem pretty good. But categorizing and holding up certain men as unquestionably perfect doesn’t do us any good—especially if we want to reckon with why men behave badly, violently even.

If you need proof of how hero worship has failed us, just look at the recent wave of sexual harassment allegations hitting the mainstream news cycle (or really, just read through #MeToo on any social platform). The men being named aren’t just open secrets like Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey. Women have come forward to say women’s activist Sen. Al Franken groped them. The face of journalistic integrity, Charlie Rose, was fired by CBS and PBS after eight women said he sexually harassed them. And then there’s Holocaust survivor and author of the book every child was taught to uphold as Great Literature, Elie Wiesel, who reportedly groped a young woman’s rear while taking a photo.

Fundamentally, these men were seen as good, and now that we’ve found out they are not, we don’t know what to make of their work that we admired. But maybe we wouldn’t be in this predicament if we didn’t assume these guys were solid people simply because of their known contributions. What if we didn’t come in with that assumption? What if we just accepted that good men are a myth?

Toxic masculinity muddies the good

When we used to think about men like Wiesel, Rose, or even George Takei, we looked at these men with childlike wonder. They were not just heroes; they could do no wrong. When was the last time Takei slipped up on Twitter? How could Rose exist as anything other than a journalistic legend? When men are good, they’re seen as powerful father figures that deserve our unconditional love and trust. Their public goodness clearly represents their moral character.

But as any fifth grader will tell you, character is built by what people do behind closed doors, not out in the open. And what we know about toxic masculinity suggests there are a lot of terrible things that happen at the hands of men behind closed doors.

One survey of college men revealed that 31.7 percent of respondents would engage in “intentions to force a woman to sexual intercourse” if the possibility arose; 13.6 percent had straightforward “intentions to rape a woman” if they could get away with it, HuffPost reports. And these are just the men who feel comfortable enough to answer truthfully.

It’s easy to see in more obvious unbalanced power dynamics, like producers handpicking actresses in the film industry, that men are given plenty of opportunities to “force a woman to sexual intercourse.” But this also happens in the power dynamics of simply being male vs. female—of being taught to get your way by all means necessary vs. being taught that standing up for yourself often gets you only punished further.

Statistics from the University of Michigan reveal that one in 12 college men have committed sexual acts that fit the legal criteria of rape, even though 84 percent don’t consider their actions to be sexual assault. In short, while not all men self-report an inclination to commit sexual assault, a sizable amount are eager to do so and have never considered what consent means or the consequences of their actions.

Surprise! The answer is that we do, and we must, regard all men as potential monsters to be feared. That's why we cross to the other side of the street at night, and why we sometimes obey when men say "Smile, honey!" We are always aware the alternative could be death. https://t.co/hvgT7c5GBa

— Monica Hesse (@MonicaHesse) November 20, 2017

In 2012, rapists turned to Reddit to explain why they rape women. Most men claimed they “didn’t understand what had happened” because they received mixed messages. Others blamed “blue balls.” Some simply saw women as objects. In many cases, attempted rapists just didn’t understand they were doing something wrong.

“I’m a good man,” one man said. “I have a wife and a couple of kids now and I’m a good father and husband. I’m a pretty moral guy. But I think the thing that has always stuck with me…is how close I came to actually doing it. If I hadn’t looked up at her face and seen what she was feeling, I might have continued .”

There’s a running theme here. In each story, the rapists (or attempted rapists) felt entitled to women’s bodies. Whether through “raging hormones” or “mixed messages,” men assumed women were supposed to be sexually available if men felt sexually aroused. Women were there to please men.

What we know about toxic masculinity explains a lot about why these sexual assaults happen. If you’re unfamiliar with the term, Dr. NerdLove calls toxic masculinity a “narrow and restrictive band of behavior, belief, and appearance” that forces men to become “emotionally repressed” and “sexually aggressive almost to the point of mindlessness.” And while toxic masculinity often pops up through predatory and misogynistic behavior, “good men” can act toxic in much smaller ways, too.

Entitlement to women, more often than not, comes down to violating everyday boundaries. Ever heard of manspreading? Whether in New York City’s subway system or international airlines, men across the world regularly take up too much space on public transit. Or worse, women are often forced to put up with men pressing their thighs, arms, butts, and fronts against our bodies in confined spaces.

Any woman who has ever worked in a male-dominated workplace is certainly more than familiar with mansplaining, where men condescendingly explain basic concepts to experienced women working in the field in question. It’s the same sort of unquestioned, unchecked entitlement that causes men to speak over women in meetings, at times even stealing their ideas and claiming them as their own. Astronomer and professor Nicole Gugliucci calls this “hepeating,” and it explains a lot the kind of environment in which sexual harassment is incubated. Women, again, aren’t seen as equals, but as accessories whose minds and bodies are owed to men.

My friends coined a word: hepeated. For when a woman suggests an idea and it's ignored, but then a guy says same thing and everyone loves it

— Nicole Gugliucci (@NoisyAstronomer) September 22, 2017

Entitlement, apathy, and sexual aggression all lead men to take advantage of women and treat them as nothing more than objects. And since toxic masculinity is a cultural dinosaur that’s learned and reinforced from childhood, practically every man has some level of toxic masculinity ingrained in them—whether it’s not standing up for women who’ve been hepeated or simply not registering that a woman may feel threatened by unsolicited DM or a male-dominated work environment.

Men don’t deserve unconditional trust

So why should women ever trust men? Whether at Disney or in Congress, PBS or Vice, the recent sexual harassment and assault allegations emerging across the U.S. prove that it’s hard to know who has “character” and who doesn’t. If a significant portion of men are capable of sexual assault, and nearly all men grapple with microaggressions against women on a regular basis, it’s obvious that giving men power and the immunity of “goodness” is a recipe for disaster.

The simplest, most everyday way men take advantage of women is by manipulating us until we unconditionally trust them. Innocence until proven guilty, right? Perhaps not.

The harassment and assault allegations sweeping the nation suggest men fundamentally (or just as likely, conveniently) don’t even understand what they’re doing wrong. All of which means they don’t deserve our trust unless they work for it. Because even when men don’t blatantly harass women, they still objectify us by acting like they deserve our ideas, careers, space, and attention. Powerful men are much more likely to face checks and balances from bystanders if we start being skeptical toward men on a regular basis. Sexual harassment and assault are less likely to be a threat to women if we admit that all men are implicated in the objectification and dismissal of women’s worth.

I am at the point where i seriously, sincerely wonder how all women don't regard all men as monsters to be constantly feared. the real world turns out to be a legit horror movie that I inhabited and knew nothing about.

— Farhad Manjoo (feat. Drake) (@fmanjoo) November 20, 2017

Ask women how often they walk to their cars with the sharp end of their key strategically pointing out between their knuckles.

— Liz Gumbinner (@Mom101) November 20, 2017

There are men who strive to do better and men who work to right their wrongs—and those men are commendable. But they still don’t deserve to be put on the “good” shelf, never to be thought of otherwise again. Because, in the end, no man is worth the risk of trusting them beyond a doubt.

Hero worship, along with the cult of personalities around “good men,” provide excuses for men who abuse women. No matter how talented a man is, a man who rapes is still a rapist. A man who “overlooks” women being harassed in his office is still a man contributing to the culture that says harassment is OK. Let’s stop calling out the “good men” and instead call out their bad actions so they understand no one is excused.

Read more: http://ift.tt/2A80DBn

from Viral News HQ http://ift.tt/2EaChGF via Viral News HQ

0 notes

Text

Book review: Know whodunit? That won’t spoil the fun of this stylish novel.

William Morrow

‘Murder on the Orient Express: A Hercule Poirot Mystery”

Agatha Christie’s first mystery, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles,” was rejected by six publishers before finally being published by John Lane in 1920. In it she introduced Hercule Poirot, today the most famous private detective since Sherlock Holmes. By the time of Christie’s death in 1976 at age 85, she herself had become the most popular fiction writer in the world, and “Murder on the Orient Express” her most popular book. It is available in multiple formats, including a facsimile of the original 1934 edition and two audio versions, by Dan Stevens and Kenneth Branagh.

Consequently, most viewers of the new Branagh film of this beloved mystery, which premieres Friday, will already know “who done it,” as well as how and why. Still, at least a few people, mainly young, will be encountering this genre classic for the first time, and old Christie fans, such as myself, shouldn’t reveal what movie posters would call its Shocking Ending.

The overall plot, though, is utterly simple: On the luxurious Istanbul-to-Calais express, a passenger is found stabbed to death, and Poirot, through the exercise of his “little grey cells,” solves the crime. Virtually everything occurs over just two days, mainly after the train grinds to a halt because of heavy snow in the former Yugoslavia.

Like so many Golden Age mysteries, the original novel is essentially a closet drama, one that closely observes the theatrical unities of place, time and action. Christie even divides her book into three sections, corresponding to the acts in a play, and she employs a great deal of dialogue, one of her real strengths as a writer. At the same time, she shows little interest in atmospheric description and makes no serious effort to fathom the psychology of her suspects. For most of the novel’s middle section, Poirot simply interrogates the passengers. Who was the barely glimpsed figure in the red kimono? Whose is a handkerchief embroidered with the initial “H”? The detective then carefully notes the arrangement of the sleeping compartments, the movements of train personnel in the night, the apparent time of the stabbing and the possibility that the original murder plan was altered because of the snow. With far-fetched good luck, Poirot even discovers a partly burned scrap of paper preserving three words that will prove the key to everything.

In summary, “Murder on the Orient Express” sounds unexceptional. So why is it so enthralling to read?

First off, Christie’s prose is lean and brisk, not so much witty as amused, or intrigued, by the curious ways of human beings. At 5 feet 4 inches tall with a head shaped like an egg, her vain and fastidious hero is — according to one young woman — “a ridiculous-looking little man. The sort of little man one could never take seriously.” Only in the 2010 David Suchet film version is the novel reinterpreted as a Dostoevskyan psychodrama in which a spiritually racked Poirot faces moral dilemmas concerning God and justice. By contrast, the written text merely aims to surprise and delight as a tour de force, its brazen imaginative daring rivaled only by the author’s 1926 masterpiece of misdirection, “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.”

Christie was, of course, unrivaled in the art of narrative sleight of hand. In her fiction, the murderer isn’t just the least likely suspect, but the least likely suspect who has already been cleared and whose innocence seems unquestionable. Nonetheless, just as “The X Files” used to proclaim, “Trust no one,” so Christie always whispers, “Suspect everyone.”

Related Articles

November 9, 2017 Staff pick: “Code Girls,” the inspiring story of America’s secret World War II heroes

November 2, 2017 Book review: A nut-and-dolt story by the author of “Wicked”

November 2, 2017 Book review: Day-to-day life in the shadow of the Civil War

October 26, 2017 Book review: Cloudy with a chance for terror in Joe Hill’s “Strange Weather”

October 26, 2017 Regional book: “Unbound” by John Shors

In “Murder on the Orient Express” she revels in showcasing a wide range of characters: the secretive Ratchett, who seems to exude pure evil; the imperious Russian Princess Dragomiroff; the governess Mary Debenham, “the kind of young woman who could take care of herself with perfect ease wherever she went” (a favorite Christie type); the stalwart India hand Colonel Arbuthnot; the young and glamorous Count and Countess Andrenyi; the loudmouthed American Mrs. Hubbard, forever nattering on about her daughter; and half a dozen others, including an Italian car salesman, a proper English valet, a German maid, the Calais coach’s French conductor, and a Swedish nurse and missionary.

From having watched trailers for the new film and studied its cast list, I can tell that Branagh — who plays a dramatically mustachioed Poirot — has enlarged the scope of the novel and slightly rejiggered its characters. There are no pistol shots, fistfights, or Hispanic or black passengers in the original book. Mrs. Hubbard is hardly a sexy, merry widow, and Poirot would never go out in the cold without being bundled up. Even the movie’s signature phrase — “My name is Hercule Poirot and I am probably the greatest detective in the world”- – actually appears in another Christie novel, “The Mystery of the Blue Train.”

Like the gorgeous 1974 screen version starring Albert Finney, Sean Connery and Ingrid Bergman, Branagh’s “Orient Express” is partly an excuse for today’s big-name Hollywood stars to dress up, look fabulous and chew the scenery. This playful “let’s put on a show” approach works especially well for this deeply theatrical novel. Besides, only on the Orient Express — or, as Poirot tellingly adds, in America — could one find such a colorful variety of nationalities and human types.

The great detective’s final revelations, with all the suspects assembled in the dining car, may strike some readers as almost fantastical. Who cares? In classic mysteries, dazzle is what counts, and realism tends to be inversely proportional to ingenuity. In this case, however, Poirot — the usually inflexible champion of law and order — does act contrary to his principles. Still, justice must sometimes trump traditional ethics. In the end, “Murder on the Orient Express” demonstrates, somewhat paradoxically, the formidable power of love and grief, coupled with unwavering purpose and mutual trust.

from News And Updates http://www.denverpost.com/2017/11/09/murder-on-the-orient-express-a-hercule-poirot-mystery-agatha-christie-book-review/

0 notes

Text

Book review: Know whodunit? That won’t spoil the fun of this stylish novel.

William Morrow

‘Murder on the Orient Express: A Hercule Poirot Mystery”

Agatha Christie’s first mystery, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles,” was rejected by six publishers before finally being published by John Lane in 1920. In it she introduced Hercule Poirot, today the most famous private detective since Sherlock Holmes. By the time of Christie’s death in 1976 at age 85, she herself had become the most popular fiction writer in the world, and “Murder on the Orient Express” her most popular book. It is available in multiple formats, including a facsimile of the original 1934 edition and two audio versions, by Dan Stevens and Kenneth Branagh.

Consequently, most viewers of the new Branagh film of this beloved mystery, which premieres Friday, will already know “who done it,” as well as how and why. Still, at least a few people, mainly young, will be encountering this genre classic for the first time, and old Christie fans, such as myself, shouldn’t reveal what movie posters would call its Shocking Ending.

The overall plot, though, is utterly simple: On the luxurious Istanbul-to-Calais express, a passenger is found stabbed to death, and Poirot, through the exercise of his “little grey cells,” solves the crime. Virtually everything occurs over just two days, mainly after the train grinds to a halt because of heavy snow in the former Yugoslavia.

Like so many Golden Age mysteries, the original novel is essentially a closet drama, one that closely observes the theatrical unities of place, time and action. Christie even divides her book into three sections, corresponding to the acts in a play, and she employs a great deal of dialogue, one of her real strengths as a writer. At the same time, she shows little interest in atmospheric description and makes no serious effort to fathom the psychology of her suspects. For most of the novel’s middle section, Poirot simply interrogates the passengers. Who was the barely glimpsed figure in the red kimono? Whose is a handkerchief embroidered with the initial “H”? The detective then carefully notes the arrangement of the sleeping compartments, the movements of train personnel in the night, the apparent time of the stabbing and the possibility that the original murder plan was altered because of the snow. With far-fetched good luck, Poirot even discovers a partly burned scrap of paper preserving three words that will prove the key to everything.

In summary, “Murder on the Orient Express” sounds unexceptional. So why is it so enthralling to read?

First off, Christie’s prose is lean and brisk, not so much witty as amused, or intrigued, by the curious ways of human beings. At 5 feet 4 inches tall with a head shaped like an egg, her vain and fastidious hero is — according to one young woman — “a ridiculous-looking little man. The sort of little man one could never take seriously.” Only in the 2010 David Suchet film version is the novel reinterpreted as a Dostoevskyan psychodrama in which a spiritually racked Poirot faces moral dilemmas concerning God and justice. By contrast, the written text merely aims to surprise and delight as a tour de force, its brazen imaginative daring rivaled only by the author’s 1926 masterpiece of misdirection, “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.”

Christie was, of course, unrivaled in the art of narrative sleight of hand. In her fiction, the murderer isn’t just the least likely suspect, but the least likely suspect who has already been cleared and whose innocence seems unquestionable. Nonetheless, just as “The X Files” used to proclaim, “Trust no one,” so Christie always whispers, “Suspect everyone.”

Related Articles

November 9, 2017 Staff pick: “Code Girls,” the inspiring story of America’s secret World War II heroes

November 2, 2017 Book review: A nut-and-dolt story by the author of “Wicked”

November 2, 2017 Book review: Day-to-day life in the shadow of the Civil War

October 26, 2017 Book review: Cloudy with a chance for terror in Joe Hill’s “Strange Weather”

October 26, 2017 Regional book: “Unbound” by John Shors

In “Murder on the Orient Express” she revels in showcasing a wide range of characters: the secretive Ratchett, who seems to exude pure evil; the imperious Russian Princess Dragomiroff; the governess Mary Debenham, “the kind of young woman who could take care of herself with perfect ease wherever she went” (a favorite Christie type); the stalwart India hand Colonel Arbuthnot; the young and glamorous Count and Countess Andrenyi; the loudmouthed American Mrs. Hubbard, forever nattering on about her daughter; and half a dozen others, including an Italian car salesman, a proper English valet, a German maid, the Calais coach’s French conductor, and a Swedish nurse and missionary.

From having watched trailers for the new film and studied its cast list, I can tell that Branagh — who plays a dramatically mustachioed Poirot — has enlarged the scope of the novel and slightly rejiggered its characters. There are no pistol shots, fistfights, or Hispanic or black passengers in the original book. Mrs. Hubbard is hardly a sexy, merry widow, and Poirot would never go out in the cold without being bundled up. Even the movie’s signature phrase — “My name is Hercule Poirot and I am probably the greatest detective in the world”- – actually appears in another Christie novel, “The Mystery of the Blue Train.”

Like the gorgeous 1974 screen version starring Albert Finney, Sean Connery and Ingrid Bergman, Branagh’s “Orient Express” is partly an excuse for today’s big-name Hollywood stars to dress up, look fabulous and chew the scenery. This playful “let’s put on a show” approach works especially well for this deeply theatrical novel. Besides, only on the Orient Express — or, as Poirot tellingly adds, in America — could one find such a colorful variety of nationalities and human types.

The great detective’s final revelations, with all the suspects assembled in the dining car, may strike some readers as almost fantastical. Who cares? In classic mysteries, dazzle is what counts, and realism tends to be inversely proportional to ingenuity. In this case, however, Poirot — the usually inflexible champion of law and order — does act contrary to his principles. Still, justice must sometimes trump traditional ethics. In the end, “Murder on the Orient Express” demonstrates, somewhat paradoxically, the formidable power of love and grief, coupled with unwavering purpose and mutual trust.

from Latest Information http://www.denverpost.com/2017/11/09/murder-on-the-orient-express-a-hercule-poirot-mystery-agatha-christie-book-review/

0 notes

Text

Book review: Know whodunit? That won’t spoil the fun of this stylish novel.

William Morrow

‘Murder on the Orient Express: A Hercule Poirot Mystery”

Agatha Christie’s first mystery, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles,” was rejected by six publishers before finally being published by John Lane in 1920. In it she introduced Hercule Poirot, today the most famous private detective since Sherlock Holmes. By the time of Christie’s death in 1976 at age 85, she herself had become the most popular fiction writer in the world, and “Murder on the Orient Express” her most popular book. It is available in multiple formats, including a facsimile of the original 1934 edition and two audio versions, by Dan Stevens and Kenneth Branagh.

Consequently, most viewers of the new Branagh film of this beloved mystery, which premieres Friday, will already know “who done it,” as well as how and why. Still, at least a few people, mainly young, will be encountering this genre classic for the first time, and old Christie fans, such as myself, shouldn’t reveal what movie posters would call its Shocking Ending.

The overall plot, though, is utterly simple: On the luxurious Istanbul-to-Calais express, a passenger is found stabbed to death, and Poirot, through the exercise of his “little grey cells,” solves the crime. Virtually everything occurs over just two days, mainly after the train grinds to a halt because of heavy snow in the former Yugoslavia.

Like so many Golden Age mysteries, the original novel is essentially a closet drama, one that closely observes the theatrical unities of place, time and action. Christie even divides her book into three sections, corresponding to the acts in a play, and she employs a great deal of dialogue, one of her real strengths as a writer. At the same time, she shows little interest in atmospheric description and makes no serious effort to fathom the psychology of her suspects. For most of the novel’s middle section, Poirot simply interrogates the passengers. Who was the barely glimpsed figure in the red kimono? Whose is a handkerchief embroidered with the initial “H”? The detective then carefully notes the arrangement of the sleeping compartments, the movements of train personnel in the night, the apparent time of the stabbing and the possibility that the original murder plan was altered because of the snow. With far-fetched good luck, Poirot even discovers a partly burned scrap of paper preserving three words that will prove the key to everything.

In summary, “Murder on the Orient Express” sounds unexceptional. So why is it so enthralling to read?

First off, Christie’s prose is lean and brisk, not so much witty as amused, or intrigued, by the curious ways of human beings. At 5 feet 4 inches tall with a head shaped like an egg, her vain and fastidious hero is — according to one young woman — “a ridiculous-looking little man. The sort of little man one could never take seriously.” Only in the 2010 David Suchet film version is the novel reinterpreted as a Dostoevskyan psychodrama in which a spiritually racked Poirot faces moral dilemmas concerning God and justice. By contrast, the written text merely aims to surprise and delight as a tour de force, its brazen imaginative daring rivaled only by the author’s 1926 masterpiece of misdirection, “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.”

Christie was, of course, unrivaled in the art of narrative sleight of hand. In her fiction, the murderer isn’t just the least likely suspect, but the least likely suspect who has already been cleared and whose innocence seems unquestionable. Nonetheless, just as “The X Files” used to proclaim, “Trust no one,” so Christie always whispers, “Suspect everyone.”

Related Articles

November 9, 2017 Staff pick: “Code Girls,” the inspiring story of America’s secret World War II heroes

November 2, 2017 Book review: A nut-and-dolt story by the author of “Wicked”

November 2, 2017 Book review: Day-to-day life in the shadow of the Civil War

October 26, 2017 Book review: Cloudy with a chance for terror in Joe Hill’s “Strange Weather”

October 26, 2017 Regional book: “Unbound” by John Shors

In “Murder on the Orient Express” she revels in showcasing a wide range of characters: the secretive Ratchett, who seems to exude pure evil; the imperious Russian Princess Dragomiroff; the governess Mary Debenham, “the kind of young woman who could take care of herself with perfect ease wherever she went” (a favorite Christie type); the stalwart India hand Colonel Arbuthnot; the young and glamorous Count and Countess Andrenyi; the loudmouthed American Mrs. Hubbard, forever nattering on about her daughter; and half a dozen others, including an Italian car salesman, a proper English valet, a German maid, the Calais coach’s French conductor, and a Swedish nurse and missionary.

From having watched trailers for the new film and studied its cast list, I can tell that Branagh — who plays a dramatically mustachioed Poirot — has enlarged the scope of the novel and slightly rejiggered its characters. There are no pistol shots, fistfights, or Hispanic or black passengers in the original book. Mrs. Hubbard is hardly a sexy, merry widow, and Poirot would never go out in the cold without being bundled up. Even the movie’s signature phrase — “My name is Hercule Poirot and I am probably the greatest detective in the world”- – actually appears in another Christie novel, “The Mystery of the Blue Train.”

Like the gorgeous 1974 screen version starring Albert Finney, Sean Connery and Ingrid Bergman, Branagh’s “Orient Express” is partly an excuse for today’s big-name Hollywood stars to dress up, look fabulous and chew the scenery. This playful “let’s put on a show” approach works especially well for this deeply theatrical novel. Besides, only on the Orient Express — or, as Poirot tellingly adds, in America — could one find such a colorful variety of nationalities and human types.

The great detective’s final revelations, with all the suspects assembled in the dining car, may strike some readers as almost fantastical. Who cares? In classic mysteries, dazzle is what counts, and realism tends to be inversely proportional to ingenuity. In this case, however, Poirot — the usually inflexible champion of law and order — does act contrary to his principles. Still, justice must sometimes trump traditional ethics. In the end, “Murder on the Orient Express” demonstrates, somewhat paradoxically, the formidable power of love and grief, coupled with unwavering purpose and mutual trust.

from Latest Information http://www.denverpost.com/2017/11/09/murder-on-the-orient-express-a-hercule-poirot-mystery-agatha-christie-book-review/

0 notes

Text

The Hermetic Philosophy

The purpose behind Hermetics and Hermeticism is the Greek god Hermes, moreover known by his Roman name Mercury. Hermes is a champion among the most interesting and distinctive of the awesome creatures. He is in like manner one of the trickiest and MEDITATION hardest to tie. That is the reason I call him the liminal god. Since Hermes is, among various diverse things, the master of the crossing point - one of his pictures is a stone describing limits liminal is an adroit word to depict him.

Hermes is a conveyance individual, a cheat, safeguard of voyagers, a criminal, a guide for souls after death and a speaker. A substantial number of these parts are related to the point of cutoff points. Interfacing the living and the dead is a verifiable instance of this, and also his association with travel and passing on messages for interchange divine creatures. He is in like manner an authority at impact and address, and his words are not so much substantial in the demanding sense. In such way he could be considered as the heavenly compel of lawful guides. Of course, to retreat to the Platonic talked, where Socrates isolates between certified thinking and paradox, Hermes would seem to exemplify the last said.

What do we make of a perfect looking like Hermes, who is in every way morally dubious, most ideal situation? Are stories about him expected to be basic preoccupation - the out of date practically identical perhaps of contemporary chemical melodic shows, where unquestionably the most captivating characters are minimal lowlifes or is there furthermore a more significant centrality?

To answer this question, we can research a part of the lessons of the Hermetic Tradition. The very words "Hermetic Tradition" are almost as questionable and ill defined as Hermes himself. Various mystery schools, factions and bleeding edge secretive systems have sprung up over the ages attesting to be recipients to the "true blue" hermetic lessons. Some of these claim that their knowledge gets from the *real* Hermes, that is Hermes Trismegistus. This teacher is ordinarily set some place in difficult to reach ancient rarity, as a general rule in Egypt (however as a less than dependable rule Atlantis). He is as a rule insinuated as the teacher of Moses. He is in like manner compared with the Egyptian god Thoth.

In the early Christian time, a couple of arrangements made the feeling that put down some Hermetic lessons. In later years, these reports were oftentimes said to be fundamentally more settled than they truly were. These pieces, which are frequently insinuated Ascension as Corpus Hermeticum reflected the syncretistic atmosphere for the most part relic in spots like Alexandria. They were influenced by varying sources, for instance, Christianity, NeoPlatonism, rationalism and Gnosticism.

Consistently, Hermeticism has resurged, most strikingly in the Renaissance, when theoretical science, the tarot and other darken lessons got the chance to be unmistakably standard. Then again, in the nineteenth Century, England, and to a lesser degree America, saw another surge of secretive lessons surface with advancements, for instance, Rosicrucianism and Theosophy. Social occasions, for instance, The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn progressed (at any rate to some degree; these were never mass improvements) the conviction that the Hermetic statute was an unbroken line that could be taken after back to old-fashioned conditions.

In the mid twentieth Century a little book rang The Kybalion appeared, composed by some person (or a couple people) simply recognized as "Three Initiates." This book compresses some heavenly benchmarks of Hermeticism, for instance, the most famous maxim of all, As Above, So Below. In this book we can similarly watch an early type of traditions, for instance, The Law of Attraction.

By and by, with the New Age improvement, Hermeticism has found another gathering of spectators, however today people will most likely merge it with the lessons of various traditions. In a manner of speaking, this is fitting, as Hermeticism itself was coming about because of blend.

If this (really misrepresented) summary of Hermeticism sounds fairly accommodating and perhaps suspicious, this is not by any methods inadvertent. I assume that there is marvelous knowledge in the Hermetic Tradition, however that to get the most from it requires a particularly watchful perspective towards all teachers, get-togethers and legitimate assessments. In such way, we may view Hermeticism as the Taoism of the West. Any person who has examined the Tao Teh Ching in all probability surveys the primary stanza, "The Tao that can be talked is not the unending Tao."

The insight of Hermeticism requires that you jump more significantly into the dubious method for Hermes himself. You should have the ability to manage a world where truth and lie are much of the time pathetically blended up. One of the "experts" of the Hermetic Tradition, Aleister Crowley, irrefutably typified this idea. With his questionable life and intentionally limitless lessons, you can't take anything he says at face regard. Be that as it may you can't dismiss it as bombast either. One of his books, really, was known as The Book of Lies.

To get by the day's end from the Chinese insight of Taoism, consider the Yin-Yang picture. It is typically portrayed as a drift broken into a balance of, one dull, one white, symbolizing the duality of Yin and Yang (or male and female, positive and negative, et cetera.). However the picture has another quality; there is ordinarily a dim spot in the white half and a white bit working at a benefit half. This is uncovering to us that a thing constantly contains a part of its backwards. If you read The Kybalion, you will see this is radiantly solid with Hermetic Teachings.

0 notes

Text

‘Good men’ don’t exist

Good men are a myth.

There are men who do good things. There are men who, by comparison to terrible men, seem pretty good. But categorizing and holding up certain men as unquestionably perfect doesn’t do us any good—especially if we want to reckon with why men behave badly, violently even.

If you need proof of how hero worship has failed us, just look at the recent wave of sexual harassment allegations hitting the mainstream news cycle (or really, just read through #MeToo on any social platform). The men being named aren’t just open secrets like Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey. Women have come forward to say women’s activist Sen. Al Franken groped them. The face of journalistic integrity, Charlie Rose, was fired by CBS and PBS after eight women said he sexually harassed them. And then there’s Holocaust survivor and author of the book every child was taught to uphold as Great Literature, Elie Wiesel, who reportedly groped a young woman’s rear while taking a photo.

Fundamentally, these men were seen as good, and now that we’ve found out they are not, we don’t know what to make of their work that we admired. But maybe we wouldn’t be in this predicament if we didn’t assume these guys were solid people simply because of their known contributions. What if we didn’t come in with that assumption? What if we just accepted that good men are a myth?

Toxic masculinity muddies the good

When we used to think about men like Wiesel, Rose, or even George Takei, we looked at these men with childlike wonder. They were not just heroes; they could do no wrong. When was the last time Takei slipped up on Twitter? How could Rose exist as anything other than a journalistic legend? When men are good, they’re seen as powerful father figures that deserve our unconditional love and trust. Their public goodness clearly represents their moral character.

But as any fifth grader will tell you, character is built by what people do behind closed doors, not out in the open. And what we know about toxic masculinity suggests there are a lot of terrible things that happen at the hands of men behind closed doors.

One survey of college men revealed that 31.7 percent of respondents would engage in “intentions to force a woman to sexual intercourse” if the possibility arose; 13.6 percent had straightforward “intentions to rape a woman” if they could get away with it, HuffPost reports. And these are just the men who feel comfortable enough to answer truthfully.

It’s easy to see in more obvious unbalanced power dynamics, like producers handpicking actresses in the film industry, that men are given plenty of opportunities to “force a woman to sexual intercourse.” But this also happens in the power dynamics of simply being male vs. female—of being taught to get your way by all means necessary vs. being taught that standing up for yourself often gets you only punished further.

Statistics from the University of Michigan reveal that one in 12 college men have committed sexual acts that fit the legal criteria of rape, even though 84 percent don’t consider their actions to be sexual assault. In short, while not all men self-report an inclination to commit sexual assault, a sizable amount are eager to do so and have never considered what consent means or the consequences of their actions.

Surprise! The answer is that we do, and we must, regard all men as potential monsters to be feared. That's why we cross to the other side of the street at night, and why we sometimes obey when men say "Smile, honey!" We are always aware the alternative could be death. https://t.co/hvgT7c5GBa

— Monica Hesse (@MonicaHesse) November 20, 2017

In 2012, rapists turned to Reddit to explain why they rape women. Most men claimed they “didn’t understand what had happened” because they received mixed messages. Others blamed “blue balls.” Some simply saw women as objects. In many cases, attempted rapists just didn’t understand they were doing something wrong.

“I’m a good man,” one man said. “I have a wife and a couple of kids now and I’m a good father and husband. I’m a pretty moral guy. But I think the thing that has always stuck with me…is how close I came to actually doing it. If I hadn’t looked up at her face and seen what she was feeling, I might have continued .”

There’s a running theme here. In each story, the rapists (or attempted rapists) felt entitled to women’s bodies. Whether through “raging hormones” or “mixed messages,” men assumed women were supposed to be sexually available if men felt sexually aroused. Women were there to please men.

What we know about toxic masculinity explains a lot about why these sexual assaults happen. If you’re unfamiliar with the term, Dr. NerdLove calls toxic masculinity a “narrow and restrictive band of behavior, belief, and appearance” that forces men to become “emotionally repressed” and “sexually aggressive almost to the point of mindlessness.” And while toxic masculinity often pops up through predatory and misogynistic behavior, “good men” can act toxic in much smaller ways, too.

Entitlement to women, more often than not, comes down to violating everyday boundaries. Ever heard of manspreading? Whether in New York City’s subway system or international airlines, men across the world regularly take up too much space on public transit. Or worse, women are often forced to put up with men pressing their thighs, arms, butts, and fronts against our bodies in confined spaces.

Any woman who has ever worked in a male-dominated workplace is certainly more than familiar with mansplaining, where men condescendingly explain basic concepts to experienced women working in the field in question. It’s the same sort of unquestioned, unchecked entitlement that causes men to speak over women in meetings, at times even stealing their ideas and claiming them as their own. Astronomer and professor Nicole Gugliucci calls this “hepeating,” and it explains a lot the kind of environment in which sexual harassment is incubated. Women, again, aren’t seen as equals, but as accessories whose minds and bodies are owed to men.

My friends coined a word: hepeated. For when a woman suggests an idea and it's ignored, but then a guy says same thing and everyone loves it

— Nicole Gugliucci (@NoisyAstronomer) September 22, 2017

Entitlement, apathy, and sexual aggression all lead men to take advantage of women and treat them as nothing more than objects. And since toxic masculinity is a cultural dinosaur that’s learned and reinforced from childhood, practically every man has some level of toxic masculinity ingrained in them—whether it’s not standing up for women who’ve been hepeated or simply not registering that a woman may feel threatened by unsolicited DM or a male-dominated work environment.

Men don’t deserve unconditional trust

So why should women ever trust men? Whether at Disney or in Congress, PBS or Vice, the recent sexual harassment and assault allegations emerging across the U.S. prove that it’s hard to know who has “character” and who doesn’t. If a significant portion of men are capable of sexual assault, and nearly all men grapple with microaggressions against women on a regular basis, it’s obvious that giving men power and the immunity of “goodness” is a recipe for disaster.

The simplest, most everyday way men take advantage of women is by manipulating us until we unconditionally trust them. Innocence until proven guilty, right? Perhaps not.

The harassment and assault allegations sweeping the nation suggest men fundamentally (or just as likely, conveniently) don’t even understand what they’re doing wrong. All of which means they don’t deserve our trust unless they work for it. Because even when men don’t blatantly harass women, they still objectify us by acting like they deserve our ideas, careers, space, and attention. Powerful men are much more likely to face checks and balances from bystanders if we start being skeptical toward men on a regular basis. Sexual harassment and assault are less likely to be a threat to women if we admit that all men are implicated in the objectification and dismissal of women’s worth.

I am at the point where i seriously, sincerely wonder how all women don't regard all men as monsters to be constantly feared. the real world turns out to be a legit horror movie that I inhabited and knew nothing about.

— Farhad Manjoo (feat. Drake) (@fmanjoo) November 20, 2017

Ask women how often they walk to their cars with the sharp end of their key strategically pointing out between their knuckles.

— Liz Gumbinner (@Mom101) November 20, 2017

There are men who strive to do better and men who work to right their wrongs—and those men are commendable. But they still don’t deserve to be put on the “good” shelf, never to be thought of otherwise again. Because, in the end, no man is worth the risk of trusting them beyond a doubt.

Hero worship, along with the cult of personalities around “good men,” provide excuses for men who abuse women. No matter how talented a man is, a man who rapes is still a rapist. A man who “overlooks” women being harassed in his office is still a man contributing to the culture that says harassment is OK. Let’s stop calling out the “good men” and instead call out their bad actions so they understand no one is excused.

Read more: http://ift.tt/2A80DBn

from Viral News HQ http://ift.tt/2EaChGF via Viral News HQ

0 notes