#corose bride

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

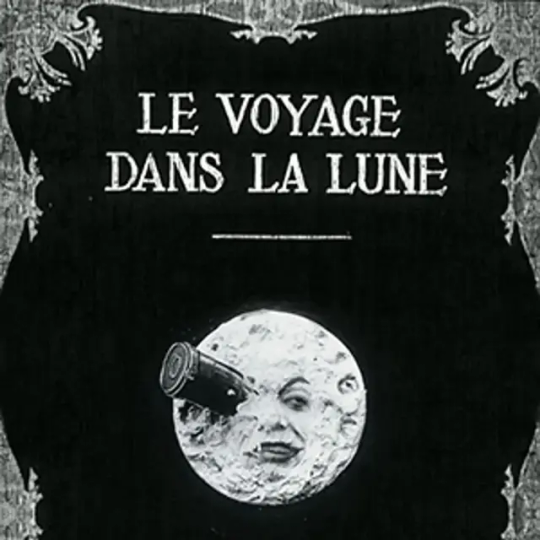

𝑃𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑒𝑐𝑙𝑖𝑝𝑠𝑒 𝑚𝑜𝑜𝑑 𝑏𝑜𝑎𝑟𝑑 🌚

#eclipse#moodboard#lisa frankenstein#jennifer's body#goth aesthetic#lisa swallows#dark academia#moon#le voyage dans la lune#corose bride

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm convinced Emilie's voice for Veronica is based off Emily of Corpse Bride. Which is kinda funny...

#wayward victorian confessions#corpse bride#nurse admin#i once saw a lovely corose birde edit to an ea song

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Memaw! How are you? I justed wanted to ask for your opinon in my favorite fairytale and comfort story, The Nutcracker

Also do you like Tum Burton movies? (Not tim burton himself, shitty man he is but his movies like Nightmare before Christmas, Corose Bride etc)

I dont like Tim Burton, but enjoy some of the movies he's directed (Seperate the art from the artist)

-L anon

i have never read the nutcracker so i dont have an opinion on it! and yes i do like some of his movies!! the nightmare before christmas will always be my favorite

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Using raineemery from tiktok as my reference I drew Emily from the Corose Bride! I absolutely adore her tiktoks and cosplays so it was a ton of fun drawing her.

1 note

·

View note