#copernicus translations

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

'I knew it was you.'

コペルニクス (Copernicus) by REISAI | JPN Lyrics

#vocal synths#vocaloid#vocaloid gif#gifset#v flower#vocaloid flower#copernicus#REISAI#ours#suicide tw#hanging tw#cults tw#< for the song#flashing#if anyone can correct/verify the translation then please do

1 note

·

View note

Text

Naruto ocs Seiya and Taro I have no idea if doing Akatsuki ocs it's an ok thing to do but whatever, I'm cringe but I'm free a bit of info about them bellow

Both Seiya and Taro are adapted ocs, Seiya's original name is Copernicus (the star of Copernicus) and he looks like this on his original self

his lore as an akatsuki member/Naruto oc is basically based on the story he alredy has, of course with some changes, like the fact that he is no longer a literal star/celestial being, instead I decided to translate his original sun/star-related powers to a kekkei-genkai

on his original story he is connected to Rosters/chickens so in Naruto verse he has a summoning contract with them

appart from that I wont go in details about his dramatic background yet, mostly because that part is still a wip, tho I alredy have some important points set, I just need to connect everything. He is from Kirigakure (The Village Hidden in the Mist)

Taro is a mix of 2 characters, Talus (a character that's related to Copernicus story) and My lycansona Marcel.

She not only share physical features of both, but also a bit of the lore of each. Which I won't go in much detail yet either because (again) it's still a wip, and because her lore is thought to be a bit triggering, so it's something I want to treat in the right way. She comes from Iwagakure (The Village Hidden in the Stones) Deidara bestie

#my art#digital art#oc#ocs#original characters#naruto oc#akatsuki oc#akatsuki#Seiya#copernicus#Taro#talus#Marcel

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript:

Peter Apian (1495-1552) Michael Ostendorfer (ca. 1490-1549) Artist

Astronomicum Caesareum

Ingolstadt 1540

Rare Book Division

This work is considered to be one of the most beautiful and spectacular contributions to the art of I6th-century book making. Astronomicum Caesareum was published by Petrus Apianus (Peter Apian), one of the foremost mathematicians, astronomers, and cartographers of the ith century. The book's title translates to "Imperial Astronomy" and is a direct reference to its two dedicatees, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and King Ferdinand I of Spain.

This is a particularly vibrant, pristine copy of Astronomicum Caesareum, which is perhaps Apian's most notable published work. The book features more than 20 elaborately decorated rotating disks, called volvelles, which, when manipulated, represent the functions of the astrolabe and other astronomical instruments used to calculate the positions of stars and planets. As one might imagine, over time and with use, these moving paper elements do not often survive intact.

This book was extremely cool. You can’t really tell from the photo how thick that stack of discs is, but it is… uh…. thick.

Transcript:

Andreas Cellarius (ca. 1596-1665)

Harmonia Macrocosmica

Amsterdam: Johannes Janssonius 1661

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division

The only celestial atlas published in the Netherlands during the golden age of Dutch cartography, Harmonia Macrocosmica completes the multivolume history of all creation first conceived by Gerardus Mercator in 1569. It consists of 29 charts depicting the competing worldviews of Claudius Ptolemy, Martianus Capella, Nicolaus Copernicus, and Tycho Brahe. Engraved plates in the Baroque style illustrate more than 400 pages of text and depict the motions of the sun, moon, and planets, as well as delineations of classical and biblical constellations. In the preface, Cellarius notes his intention to create a second volume to address the new astronomical observations made available by the invention of the telescope. Unfortunately, this was never realized, due to his death in 1665.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Richard Dawkins

This is a slightly edited version of the essay written to accompany the transcript of the conversation between myself, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris and the late, much-lamented Christopher Hitchens, recorded in Christopher's flat in Washington DC in September 2007 and published in 2019 as The Four Horsemen.

Among the many topics the ‘four horsemen’ discussed in 2007 was how religion and science compared in respect of humility and hubris. Religion, for its part, stands accused of conspicuous overconfidence and sensational lack of humility. The expanding universe, the laws of physics, the fine-tuned physical constants, the laws of chemistry, the slow grind of evolution’s mills – all were set in motion so that, in the 14-billion-year fullness of time, we should come into existence. Even the constantly reiterated insistence that we are miserable offenders, born in sin, is a kind of inverted arrogance: such vanity, to presume that our moral conduct has some sort of cosmic significance, as though the Creator of the Universe wouldn’t have better things to do than tot up our black marks and our brownie points. The universe is all concerned with me. Is that not the arrogance that passeth all understanding?

Carl Sagan, in Pale Blue Dot, makes the exculpatory point that our distant ancestors could scarcely escape such cosmic narcissism. With no roof over their heads and no artificial light, they nightly watched the stars wheeling overhead. And what was at the centre of the wheel? The exact location of the observer, of course. No wonder they thought the universe was ‘all about me’. In the other sense of ‘about’, it did indeed revolve ‘about me’. ‘I’ was the epicentre of the cosmos. But that excuse, if it is one, evaporated with Copernicus and Galileo.

Turning, then, to theologians’ overconfidence, admittedly few quite reach the heights scaled by the seventeenth-century archbishop James Ussher, who was so sure of his chronology that he gave the origin of the universe a precise date: 22 October, 4004 bc. Not 21 or 23 October but precisely on the evening of 22 October. Not September or November but definitely, with the immense authority of the Church, October. Not 4003 or 4005, not ‘somewhere around the fourth or fifth millennium bc’ but, no doubt about it, 4004 bc. Others, as I said, are not quite so precise about it, but it is characteristic of theologians that they just make stuff up. Make it up with liberal abandon and force it, with a presumed limitless authority, upon others, sometimes – at least in former times and still today in Islamic theocracies – on pain of torture and death.

Such arbitrary precision shows itself, too, in the bossy rules for living that religious leaders impose on their followers. And when it comes to control-freakery, Islam is way out ahead, in a class of its own. Here are some choice examples from the Concise Commandments of Islam handed down by Ayatollah Ozma Sayyed Mohammad Reda Musavi Golpaygani, a respected Iranian ‘scholar’. Concerning the wet-nursing of babies, alone, there are no fewer than twenty-three minutely specified rules, translated as ‘Issues’. Here’s the first of them, Issue 547. The rest are equally precise, equally bossy, and equally devoid of apparent rationale:

If a woman wet-nurses a child, in accordance to the conditions to be stated in Issue 560, the father of that child cannot marry the woman’s daughters, nor can he marry the daughters of the husband whom the milk belongs to, even his wet-nurse daughters, but it is permissible for him to marry the wet-nurse daughters of the woman . . . [and it goes on].

Here’s another example from the wet-nursing department, Issue 553:

If the wife of a man’s father wet-nurses a girl with his father’s milk, then the man cannot marry that girl.

‘Father’s milk’? What? I suppose in a culture where a woman is the property of her husband, ‘father’s milk’ is not as weird as it sounds to us.

Issue 555 is similarly puzzling, this time about ‘brother’s milk’:

A man cannot marry a girl who has been wet-nursed by his sister or his brother’s wife with his brother’s milk.

I don’t know the origin of this creepy obsession with wet-nursing, but it is not without its scriptural basis:

When the Qur’aan was first revealed, the number of breast-feedings that would make a child a relative (mahram) was ten, then this was abrogated and replaced with the number of five which is well-known.[1]

That was part of the reply from another ‘scholar’ to the following recent cri de coeur from a (pardonably) confused woman on social media:

I breastfed my brother-in-law’s son for a month, and my son was breastfed by my brother-in-law’s wife. I have a daughter and a son who are older than the child who was breastfed by my brother-in-law’s wife, and she also had two children before the child of hers whom I breastfed. I hope that you can describe the kind of breastfeeding that makes the child a mahram and the rulings that apply to the rest of the siblings? Thank you very much.

The precision of ‘five’ breast feedings is typical of this kind of religious control-freakery. It surfaced bizarrely in a 2007 fatwa issued by Dr Izzat Atiyya, a lecturer at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, who was concerned about the prohibition against male and female colleagues being alone together and came up with an ingenious solution. The female colleague should feed her male colleague ‘directly from her breast’ at least five times. This would make them ‘relatives’ and thereby enable them to be alone together at work. Note that four times would not suffice. He apparently wasn’t joking at the time, although he did retract his fatwa after the outcry it provoked. How can people bear to live their lives bound by such insanely specific yet manifestly pointless rules?

With some relief, perhaps, we turn to science. Science is often accused of arrogantly claiming to know everything, but the barb is capaciously wide of the mark. Scientists love not knowing the answer, because it gives us something to do, something to think about. We loudly assert ignorance, in a gleeful proclamation of what needs to be done.

How did life begin? I don’t know, nobody knows, we wish we did, and we eagerly exchange hypotheses, together with suggestions for how to investigate them. What caused the apocalyptic mass extinction at the end of the Permian period, a quarter of a billion years ago? We don’t know, but we have some interesting hypotheses to think about. What did the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees look like? We don’t know, but we do know a bit about it. We know the continent on which it lived (Africa, as Darwin guessed), and molecular evidence tells us roughly when (between 6 million and 8 million years ago). What is dark matter? We don’t know, and a substantial fraction of the physics community would dearly like to.

Ignorance, to a scientist, is an itch that begs to be pleasurably scratched. Ignorance, if you are a theologian, is something to be washed away by shamelessly making something up. If you are an authority figure like the Pope, you might do it by thinking privately to yourself and waiting for an answer to pop into your head – which you then proclaim as a ‘revelation’. Or you might do it by ‘interpreting’ a Bronze Age text whose author was even more ignorant than you are.

Popes can promulgate their private opinions as ‘dogma’, but only if those opinions have the backing of a substantial number of Catholics through history: long tradition of belief in a proposition is, somewhat mysteriously to a scientific mind, regarded as evidence for the truth of that proposition. In 1950, Pope Pius XII (unkindly known as ‘Hitler’s Pope’) promulgated the dogma that Jesus’ mother Mary, on her death, was bodily – i.e. not merely spiritually – lifted up into heaven. ‘Bodily’ means that if you’d looked in her grave, you’d have found it empty. The Pope’s reasoning had absolutely nothing to do with evidence. He cited 1 Corinthians 15:54: ‘then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory’. The saying makes no mention of Mary. There is not the smallest reason to suppose the author of the epistle had Mary in mind. We see again the typical theological trick of taking a text and ‘interpreting’ it in a way that just might have some vague, symbolic, hand-waving connection with something else. Presumably, too, like so many religious beliefs, Pius XII’s dogma was at least partly based on a feeling of what would be fitting for one so holy as Mary. But the Pope’s main motivation, according to Dr Kenneth Howell, director of the John Henry Cardinal Newman Institute of Catholic Thought, University of Illinois, came from a different meaning of what was fitting. The world of 1950 was recovering from the devastation of the Second World War and desperately needed the balm of a healing message. Howell quotes the Pope’s words, then gives his own interpretation:

Pius XII clearly expresses his hope that meditation on Mary’s assumption will lead the faithful to a greater awareness of our common dignity as the human family. . . . What would impel human beings to keep their eyes fixed on their supernatural end and to desire the salvation of their fellow human beings? Mary’s assumption was a reminder of, and impetus toward, greater respect for humanity because the Assumption cannot be separated from the rest of Mary’s earthly life.

It’s fascinating to see how the theological mind works: in particular, the lack of interest in – indeed, the contempt for – factual evidence. Never mind whether there’s any evidence that Mary was assumed bodily into heaven; it would be good for people to believe she was. It isn’t that theologians deliberately tell untruths. It’s as though they just don’t care about truth; aren’t interested in truth; don’t know what truth even means; demote truth to negligible status compared with other considerations, such as symbolic or mythic significance. And yet at the same time, Catholics are compelled to believe these made-up ‘truths’ – compelled in no uncertain terms. Even before Pius XII promulgated the Assumption as a dogma, the eighteenth-century Pope Benedict XIV declared the Assumption of Mary to be ‘a probable opinion which to deny were impious and blasphemous’. If to deny a ‘probable opinion’ is ‘impious and blasphemous’, you can imagine the penalty for denying an infallible dogma! Once again, note the brazen confidence with which religious leaders assert ‘facts’ which even they admit are supported by no historical evidence at all.

The Catholic Encyclopedia is a treasury of overconfident sophistry. Purgatory is a sort of celestial waiting room in which the dead are punished for their sins (‘purged’) before eventually being admitted to heaven. The Encyclopedia’s entry on purgatory has a long section on ‘Errors’, listing the mistaken views of heretics such as the Albigenses, Waldenses, Hussites and Apostolici, unsurprisingly joined by Martin Luther and John Calvin.[2]

The biblical evidence for the existence of purgatory is, shall we say, ‘creative’, again employing the common theological trick of vague, hand-waving analogy. For example, the Encyclopedia notes that ‘God forgave the incredulity of Moses and Aaron, but as punishment kept them from the “land of promise”’. That banishment is viewed as a kind of metaphor for purgatory. More gruesomely, when David had Uriah the Hittite killed so that he could marry Uriah’s beautiful wife, the Lord forgave him – but didn’t let him off scot-free: God killed the child of the marriage (2 Samuel 12:13–14). Hard on the innocent child, you might think. But apparently a useful metaphor for the partial punishment that is purgatory, and one not overlooked by the Encyclopedia’s authors.

The section of the purgatory entry called ‘Proofs’ is interesting because it purports to use a form of logic. Here’s how the argument goes. If the dead went straight to heaven, there’d be no point in our praying for their souls. And we do pray for their souls, don’t we? Therefore it must follow that they don’t go straight to heaven. Therefore there must be purgatory. QED. Are professors of theology really paid to do this kind of thing?

Enough; let’s turn again to science. Scientists know when they don’t know the answer. But they also know when they do, and they shouldn’t be coy about proclaiming it. It’s not hubristic to state known facts when the evidence is secure. Yes, yes, philosophers of science tell us a fact is no more than a hypothesis which may one day be falsified but which has so far withstood strenuous attempts to do so. Let us by all means pay lip service to that incantation, while muttering, in homage to Galileo’s muttered eppur si muove, the sensible words of Stephen Jay Gould:

In science, ‘fact’ can only mean ‘confirmed to such a degree that it would be perverse to withhold provisional assent.’ I suppose that apples might start to rise tomorrow, but the possibility does not merit equal time in physics classrooms.[3]

Facts in this sense include the following, and not one of them owes anything whatsoever to the many millions of hours devoted to theological ratiocination. The universe began between 13 billion and 14 billion years ago. The sun, and the planets orbiting it, including ours, condensed out of a rotating disk of gas, dust and debris about 4.5 billion years ago. The map of the world changes as the tens of millions of years go by. We know the approximate shape of the continents and where they were at any named time in geological history. And we can project ahead and draw the map of the world as it will change in the future. We know how different the constellations in the sky would have appeared to our ancestors and how they will appear to our descendants.

Matter in the universe is non-randomly distributed in discrete bodies, many of them rotating, each on its own axis, and many of them in elliptical orbit around other such bodies according to mathematical laws which enable us to predict, to the exact second, when notable events such as eclipses and transits will occur. These bodies – stars, planets, planetesimals, knobbly chunks of rock, etc. – are themselves clustered in galaxies, many billions of them, separated by distances orders of magnitude larger than the (already very large) spacing of (again, many billions of) stars within galaxies.

Matter is composed of atoms, and there is a finite number of types of atoms – the hundred or so elements. We know the mass of each of these elemental atoms, and we know why any one element can have more than one isotope with slightly different mass. Chemists have a huge body of knowledge about how and why the elements combine in molecules. In living cells, molecules can be extremely large, constructed of thousands of atoms in precise, and exactly known, spatial relation to one another. The methods by which the exact structures of these macromolecules are discovered are wonderfully ingenious, involving meticulous measurements on the scattering of X-rays beamed through crystals. Among the macromolecules fathomed by this method is DNA, the universal genetic molecule. The strictly digital code by which DNA influences the shape and nature of proteins – another family of macromolecules which are the elegantly honed machine-tools of life – is exactly known in every detail. The ways in which those proteins influence the behaviour of cells in developing embryos, and hence influence the form and functioning of all living things, is work in progress: a great deal is known; much challengingly remains to be learned.

For any particular gene in any individual animal, we can write down the exact sequence of DNA code letters in the gene. This means we can count, with total precision, the number of single-letter discrepancies between two individuals. This is a serviceable measure of how long ago their common ancestor lived. This works for comparisons within a species – between you and Barack Obama, for instance. And it works for comparisons of different species – between you and an aardvark, say. Again, you can count the discrepancies exactly. There are just more discrepancies the further back in time the shared ancestor lived. Such precision lifts the spirit and justifies pride in our species, Homo sapiens. For once, and without hubris, Linnaeus’s specific name seems warranted.

Hubris is unjustified pride. Pride can be justified, and science does so in spades. So does Beethoven, so do Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Christopher Wren. So do the engineers who built the giant telescopes in Hawaii and in the Canary Islands, the giant radio telescopes and very large arrays that stare sightless into the southern sky; or the Hubble orbiting telescope and the spacecraft that launched it. The engineering feats deep underground at CERN, combining monumental size with minutely accurate tolerances of measurement, literally moved me to tears when I was shown around. The engineering, the mathematics, the physics, in the Rosetta mission that successfully soft-landed a robot vehicle on the tiny target of a comet also made me proud to be human. Modified versions of the same technology may one day save our planet by enabling us to divert a dangerous comet like the one that killed the dinosaurs.

Who does not feel a swelling of human pride when they hear about the LIGO instruments which, synchronously in Louisiana and Washington State, detected gravitation waves whose amplitude would be dwarfed by a single proton? This feat of measurement, with its profound significance for cosmology, is equivalent to measuring the distance from Earth to the star Proxima Centauri to an accuracy of one human hair’s breadth.

Comparable accuracy is achieved in experimental tests of quantum theory. And here there is a revealing mismatch between our human capacity to demonstrate, with invincible conviction, the predictions of a theory experimentally and our capacity to visualize the theory itself. Our brains evolved to understand the movement of buffalo-sized objects at lion speeds in the moderately scaled spaces afforded by the African savannah. Evolution didn’t equip us to deal intuitively with what happens to objects when they move at Einsteinian speeds through Einsteinian spaces, or with the sheer weirdness of objects too small to deserve the name ���object’ at all. Yet somehow the emergent power of our evolved brains has enabled us to develop the crystalline edifice of mathematics by which we accurately predict the behaviour of entities that lie under the radar of our intuitive comprehension. This, too, makes me proud to be human, although to my regret I am not among the mathematically gifted of my species.

Less rarefied but still proud-making is the advanced, and continually advancing, technology that surrounds us in our everyday lives. Your smartphone, your laptop computer, the satnav in your car and the satellites that feed it, your car itself, the giant airliner that can loft not just its own weight plus passengers and cargo but also the 120 tons of fuel it ekes out over a thirteen-hour journey of seven thousand miles.

Less familiar, but destined to become more so, is 3D printing. A computer ‘prints’ a solid object, say a chess bishop, by depositing a sequence of layers, a process radically and interestingly different from the biological version of ‘3D printing’ which is embryology. A 3D printer can make an exact copy of an existing object. One technique is to feed the computer a series of photographs of the object to be copied, taken from all different angles. The computer does the formidably complicated mathematics to synthesize the specification of the solid shape by integrating the angular views. There may be life forms in the universe that make their children in this body-scanning kind of way, but our own reproduction is instructively different. This, incidentally, is why almost all biology textbooks are seriously wrong when they describe DNA as a ‘blueprint’ for life. DNA may be a blueprint for protein, but it is not a blueprint for a baby. It’s more like a recipe or a computer program.

We are not arrogant, not hubristic, to celebrate the sheer bulk and detail of what we know through science. We are simply telling the honest and irrefutable truth. Also honest is the frank admission of how much we don’t yet know – how much more work remains to be done. That is the very antithesis of hubristic arrogance. Science combines a massive contribution, in volume and detail, of what we do know with humility in proclaiming what we don’t. Religion, by embarrassing contrast, has contributed literally zero to what we know, combined with huge hubristic confidence in the alleged facts it has simply made up.

But I want to suggest a further and less obvious point about the contrast of religion with atheism. I want to argue that the atheistic worldview has an unsung virtue of intellectual courage. Why is there something rather than nothing? Our physicist colleague Lawrence Krauss, in his book A Universe from Nothing,[4] controversially suggests that, for quantum-theoretic reasons, Nothing (the capital letter is deliberate) is unstable. Just as matter and antimatter annihilate each other to make Nothing, so the reverse can happen. A random quantum fluctuation causes matter and antimatter to spring spontaneously out of Nothing. Krauss’s critics largely focus on the definition of Nothing. His version may not be what everybody understands by nothing, but at least it is supremely simple – as simple it must be, if it is to satisfy us as the base of a ‘crane’ explanation (Dan Dennett’s phrase), such as cosmic inflation or evolution. It is simple compared to the world that followed from it by largely understood processes: the big bang, inflation, galaxy formation, star formation, element formation in the interior of stars, supernova explosions blasting the elements into space, condensation of element-rich dust clouds into rocky planets such as Earth, the laws of chemistry by which, on this planet at least, the first self-replicating molecule arose, then evolution by natural selection and the whole of biology which is now, at least in principle, understood.

Why did I speak of intellectual courage? Because the human mind, including my own, rebels emotionally against the idea that something as complex as life, and the rest of the expanding universe, could have ‘just happened’. It takes intellectual courage to kick yourself out of your emotional incredulity and persuade yourself that there is no other rational choice. Emotion screams: ‘No, it’s too much to believe! You are trying to tell me the entire universe, including me and the trees and the Great Barrier Reef and the Andromeda Galaxy and a tardigrade’s finger, all came about by mindless atomic collisions, no supervisor, no architect? You cannot be serious. All this complexity and glory stemmed from Nothing and a random quantum fluctuation? Give me a break.’ Reason quietly and soberly replies: ‘Yes. Most of the steps in the chain are well understood, although until recently they weren’t. In the case of the biological steps, they’ve been understood since 1859. But more important, even if we never understand all the steps, nothing can change the principle that, however improbable the entity you are trying to explain, postulating a creator god doesn’t help you, because the god would itself need exactly the same kind of explanation.’ However difficult it may be to explain the origin of simplicity, the spontaneous arising of complexity is, by definition, more improbable. And a creative intelligence capable of designing a universe would have to be supremely improbable and supremely in need of explanation in its own right. However improbable the naturalistic answer to the riddle of existence, the theistic alternative is even more so. But it needs a courageous leap of reason to accept the conclusion.

This is what I meant when I said the atheistic worldview requires intellectual courage. It requires moral courage, too. As an atheist, you abandon your imaginary friend, you forgo the comforting props of a celestial father figure to bail you out of trouble. You are going to die, and you’ll never see your dead loved ones again. There’s no holy book to tell you what to do, tell you what’s right or wrong. You are an intellectual adult. You must face up to life, to moral decisions. But there is dignity in that grown-up courage. You stand tall and face into the keen wind of reality. You have company: warm, human arms around you, and a legacy of culture which has built up not only scientific knowledge and the material comforts that applied science brings but also art, music, the rule of law, and civilized discourse on morals. Morality and standards for life can be built up by intelligent design – design by real, intelligent humans who actually exist. Atheists have the intellectual courage to accept reality for what it is: wonderfully and shockingly explicable. As an atheist, you have the moral courage to live to the full the only life you’re ever going to get: to fully inhabit reality, rejoice in it, and do your best finally to leave it better than you found it.

-

[1] https://islamqa.info/en/27280 [2] http://www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/view.php?id=9745 [3] ‘Evolution as fact and theory’. [4] For which I wrote an afterword.

#Richard Dawkins#atheism#moral courage#intellectual courage#intellectual honesty#science#religion is a mental illness

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Army Museum Worker Discovers Early Medieval Sword in Poland

The collection of the Army Museum in Białystok, Poland has been enriched after renovation with a unique relic of great historical value – an early medieval sword of the Viking type, dating from the 9th or 10th centuries. It was found by an employee of this institution while diving in the Supraśl River over two years ago.

This rare artifact, which was found by museum employee Szczepan Skibicki in 2022 while diving in the Supraśl River, is among only a handful of similar swords discovered in the country.

Skibicki stumbled upon the sword in a river bend where erosion had exposed a sand deposit. “At about 120cm [four feet] deep,” Skibicki recalled, as translated from Polish to English through Facebook, “I spotted an interesting object which turned out to be a sword! Then for the first and last time, I screamed for joy under the water!… Thanks to my education and work I knew how to secure it and which services to notify.”

He likened the discovery to winning the lottery, reflecting on the extraordinary luck involved in unearthing such a treasure.

The sword, which may have been linked by Baltic or Viking cultures, was forged in the late ninth or early tenth century, according to experts. Despite Poland’s lack of Viking activity, archeological evidence demonstrates that the Vikings were present at important administrative and commercial hubs during this time. The unique hilt of the weapon denotes its design, which is in keeping with Viking craftsmanship while also suggest potential Baltic community influences.

Dr. Ryszard Kazimierczak of Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń highlighted the sword’s rarity and cultural significance: “The sword is unique due to its form, shape, and the degree of preservation of organic material visible on the hilt. This is incredibly rare for artifacts of this age.”

“We think there is a high probability that there was a fight by the river, a battle and the sword was in the water with its owner,” Kaźmierczak said, per the museum’s Facebook post.

The blade itself tells a story of conflict, bearing micro-cracks, scratches, and splinters likely resulting from combat. “The middle part shows how time and use have acted upon it,” explained Robert Sadowski, director of the Army Museum. “When these swords were used in battle, the middle part absorbed the most blows, leading to the wear and tear visible today.”

The Ministry of Science and Higher Education noted in its press release that before the sword could be transferred to the Army Museum it had to go through legal protocol overseen by the Provincial Conservator of Monument. Once it became the property of the Army Museum, the sword went into conservation involving specialists from the Institute of Archaeology of the Nicolaus Copernicus University.

By Leman Altuntaş.

#Army Museum Worker Discovers Early Medieval Sword in Poland#Army Museum in Białystok Poland#ancient sword#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#medieval history

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! Your TBR is probably very long already but I must pitch in with Andrzej Sapkowski's Hussite Trilogy! It has: Hussites (duh), Inquisition, tons of Medieval goodness, clueless garbage protagonist who insists he's Silesian and not German and DEFINITELY not a heretic, demons, cameos by Copernicus and Gutenberg + many a reminder that Sapkowski is an EruditeTM and lover of history.

I hope the English translation does it justice.

...aha. I went to the library yesterday to pick up my stack of holds. Then today I went to the bookstore in the "I deserve a little treat" mood that could not possibly backfire. The result is that my bedside table now looks like this:

So I might quite possibly have enough books for the time being. However, if this fails, I shall indeed keep your suggestion in mind. 😂

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

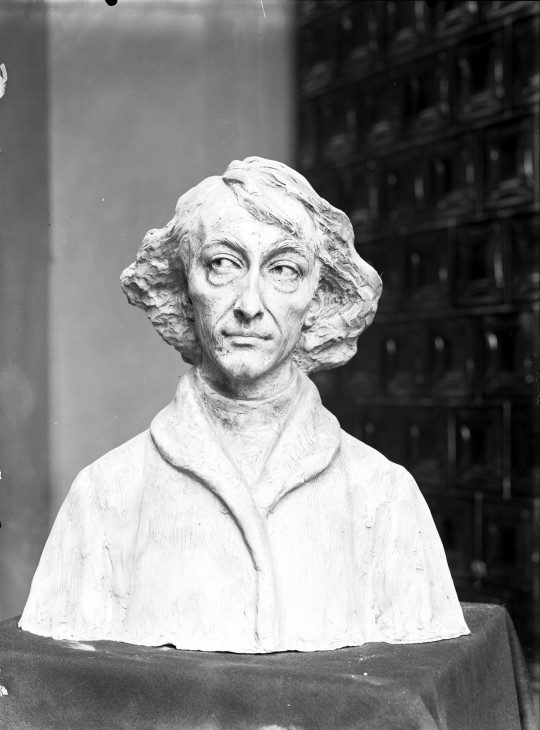

Nicolaus Copernicus (Konstanty Laszczka, Polish sculptor)

Happy birthday, Nicolaus Copernicus!

Nicolaus Copernicus (February 19, 1473 — May 24, 1543) is primarily known as an exceptional astronomer who formulated the true model of the solar system, which led to an unprecedented change in the human perception of Earth’s place in the universe. This great Pole, who is rightly included among the greatest minds of the European Renaissance, was also a clergyman, a mathematician, a physician, a lawyer and a translator. He also proved himself as an effective strategist and military commander, leading the defence of Olsztyn against the attack of the German Monastic Order of the Teutonic Knights. Later on, he exhibited great organizational skills, quickly rebuilding and relaunching the economy of the areas devastated by the invasion of the Teutonic Knights. He also served in diplomacy and participated in the works of the Polish Sejm.

Copernicus’ scientific achievements in the field of economics were equally significant, and place him among the greatest authors of the world economic thought. In 1517 Copernicus wrote a treatise on the phenomenon of bad money driving out good money. He noted that the“debasement of coin” was one of the main reasons for the collapse of states. He was therefore one of the first advocates of modern monetary policy based on the unification of the currency in circulation, constant care for its value and the prevention of inflation, which ruins the economy. In money he distinguished the ore value (valor) and the estimated value (estimatio), determined by the issuer. According to Copernicus, the ore value of a good coin should correspond to its estimated value. This was not synonymous, however, with the reduction of the coin to a piece of metal being the subject of trade in goods. The ore contained in the money was supposed to be the guarantee of its price, and the value of the legal tender was assigned to it by special symbols proving its relationship with a given country and ruler. Although such views are nothing new today, in his time they constituted a milestone in the development of economic thought.

Additionally Copernicus was not only a theorist of finance, but he was also the co-author of a successful monetary reform, later also implemented in other countries. It was Copernicus, the first of the great Polish economists, who in 1519 proposed to King Sigismund I the Old to unify the monetary system of the Polish Crown with that of its subordinate Royal Prussia. The principles described in the treatise published in 1517 were decades later repeated by the English financier Thomas Gresham and are currently most often referred to around the world as Gresham’s law. Historical truth, however, requires us to restore the authorship of this principle to its creator, for example through the popularization of knowledge about the Copernicus-Gresham Law. (© NBP - We protect the value of money).

#nicolaus copernicus#mikołaj kopernik#sculpture#poland#science#konstanty laszczka#scienceblr#scientists#science academia#astronomy#thomas gresham#science history#renaissance#16th century#polish artist#study inspiration#solar system#planets#prussia#kingdom of poland#*

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Painted Hall, Greenwich

During the king’s coronation I visited Greenwich's "Painted Hall." This series of rooms depict scenes relating to the success of British Protestantism and the beginning of burgeoning imperial expansion. Following the vital English naval victory over France at La Hougue in 1692, Queen Mary ordered that a hospital be built for retired seamen, in keeping with the existing hospital for former soldiers at Chelsea. While Mary died before its completion her husband, William III, saw the projected through. Sir Christopher Wren (of St Paul’s fame) and his assistant, Nicholas Hawksmoor, designed a grand series of buildings at Greenwich, in London. The Royal Hospital at Greenwich acted as a retirement home for sailors between the 1700s and late 1900s. And at its heart is the Painted Hall, a series of rooms where a relatively unknown artist, James Thornhill, was commissioned to paint scenes of British-Protestant triumph.

At the centre is King William III and Queen Mary shown overseeing ‘The Triumph of Peace and Liberty over Tyranny.’ Immediately above the couple and to their left is the allegorical figure of Prudence holding a mirror, one of the four Cardinal Virtues.

To her right are Providence and Concord, while to her left is Justice. Beneath Justice is a woman representing Europe, who is accepting the ‘cap of liberty,’ the ancient red Phrygian cap, from William, who in turn is accepting an olive branch from ‘Peace.’

Beneath William’s foot is the defeated Louis XIV of France with a broken sword, and a tumbling, discarded papal crown. Beneath them the ‘Spirit of Architecture’ along with Truth and Time are overseeing plans showing the actual construction of the hospital.

Above it all, Apollo rides his chariot, while the signs of the zodiac are arrayed around the edges. At the bottom, Pallas Athena and Hercules crush the Hydra and the Gorgon, ‘expelling the Vices from the Kingdom of William and Mary.’

Another section of the ceiling shows a captured Spanish galley laden with the spoils of war, a reference to the British capture of Gibraltar in 1704. Diana, Goddess of the moon, passes mastery of the tides over to British sailors. Beneath them are representations of the English rivers Avon, Severn and Humber.

To the left and the right, scientific advancement is celebrated by the presence of astronomers Tycho Brahe, John Flamsteed, Copernicus and Newton’s ‘Principia.’ The gods Neptune and Cybele oversee it all.

The next section of the ceiling shows HMS Blenheim being filled with the spoils of war by the winged figure of Victory. Beneath are more river representations along with the City of London and figures representing navigation and astronomy. On the left is Galileo, while Zeus and Juno watch from above.

The painted hall took decades to complete, and saw further dynastic change, as George I, originally of Hanover, became king after William III’s successor, Queen Anne, died. George maintained the Protestant ascendancy, as portrayed in the upper hall chamber adjoining the main hall.

Here we see George I, his wife Sophia of Hanover and their children and grandchildren beneath St Paul’s, overseen the a figure representing “the Golden Age” with overflowing cornucopia. The artist, James Thornhill, added himself on the right. Over them is an inscription quoting Virgil's Eclogues, which translates as ‘a new generation has descended from the heavens.’

On the left of the upper hall is a depiction of William III’s arrival in England at the start of the Glorious Revolution in 1688, while George I is shown arriving on the opposite side of the hall (rather unrealistically in a chariot) in 1714.

#painted hall#the painted hall#greenwich#history#british history#art#art history#william iii#william of orange#william and mary#george i#queen anne#17th century#18th century

137 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok I know i asked a song just the other day but this one is too good to pass up yknow. Also why not let me do the honors

月を見つけた人 feat.結月ゆかり 麗, Hayden - ikomai

Song Title:

The Mankind Who Discovered the Moon!

"The people who discovered the moon ♪

I want to meet them in the sky ♫

Copernicus too Columnist too (?)

Someone who found something else〜 ♪♪

Even if they are not around anymore (their footprints are remaining ♬)

A step looking that small but a very big step ♪♪♪

People who danced at a festival ♪

The view, laughing is also entertaining ♫

Artist too Athlete too !

People who laugh off everything〜 !!

Even if the wind blows oppositely ♩♬

The left foot that they stepped forward with ♪

An important step!

Probably Evolution's Step!! "

(mind you this bit is nowhere near an optimal translation, just know that i have tried and failed miserably)

i like the translation! the song is super cute/mellow with a jazzy vibe. i really like the tuning as well! might need to check out more of ikomai's works now...

youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A shufflemancy for Dazai's relationship with Chuuya

General disclaimer: I hope these make sense to you, but you always know yourself best what is and isn't true to you and your canon. As per usual we rolled three times.

As always: Please heed the TW's. The final song in this list deals with death, loss and suicide themes.

The Shufflemancy says...

The Thing That's Only There by Pure Palette

It's a cute song about two friends who are very close and rely on each other. I don't have much to say, it's an obvious song.

Official audio | Lyrics | Lyric video

WILD STARS by μ’s

A song about a couple discussing their relationship status under a dark sky. In live shows the choreography is also reflective of this and the group break up into 'couples'.

Official audio | Lyrics | Lyric video

Let's go Somewhere by reinou

This song takes place after one of the characters has died (I don't think it's ever stated how she died) but the song focuses on the effect it had on the girl crushing on her. At this point she is suicidal because of the death and now shuts herself away in her room with only the memories to comfort her.

Official video | Lyrics

Other songs that came up:

Copernicus by REISAI (JPN lyrics)

I can't translate this song and there is no EN translation I can find.

-

Conclusion:

I think your relationship for the most part could have been friendly, none of these songs suggest hostility or bitterness (expect for at the end).

Given that all of the songs do not ever establish a romantic relationship (songs one is platonic, song two discusses it, in song three the other girl was never told about the love her friend had for her) I think it could be perhaps you didn't ever discuss the status of your relationship.

Death seems to be a theme within the last song (and Copernicus), I would keep that in mind as well. I will note that 'death' is a broad concept within readings like this, it could easily mean the end of the friendship, not a literal death.

This is all speculation of course!

#🐾 | kin readings#shufflemancy#kin shufflemancy#dazai osamu kin#bsd kin#bungou stray dogs kin#fictionkin

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are we so fascinated with aliens?

Robert Smith is convinced the aliens have won. "The invasion has happened—it's all over," says the University of Alberta space historian who teaches a course on the history of extraterrestrials.

It's not so much that Smith believes in their literal existence, only that aliens have staked their claim in the human imagination.

"Look at the TV listings on any given night, and it's clear they are everywhere," he says. "The number of programs with extraterrestrials is striking."

Just last month, the seventh film of the Alien franchise, "Alien Romulus," was released in theaters worldwide. The series has gripped the collective imagination since 1979 and is showing no signs of slowing down. Romulus has grossed more than $225 million worldwide so far, making it the third-highest-grossing film in the series.

When he isn't tracking every detail of the James Webb telescope, launched in December of 2021, for an upcoming book on the subject, Smith is reviewing his notes for a senior seminar called "The History of the Extraterrestrial Life Debate." According to him, it's the only course in the world that probes "the existence, nature and possible significance of extraterrestrial life from the ancient world to today."

Smith contends aliens have been invading our imagination at least since the ancients. The Greek philosopher Epicurus—who first came up with the idea that the universe is made up of atoms—speculated about other worlds, as did the Roman poet Lucretius.

In the second century CE, Lucian of Samosata wrote what is considered the first work of science fiction, a satire called "A True Story" about inhabitants of the sun and the moon fighting over the colonization of Venus.

"There's always been this fascination with what you could call the other, often very similar to us but sometimes different or even wildly different," says Smith.

"The extraterrestrial becomes a kind of mirror, and by trying to understand how people see extraterrestrials, we're also learning about what people think it is to be human."

Even the Catholic Church of the Middle Ages considered the possibility of aliens as a manifestation of God's power, says Smith.

"If you attended a medieval university … one of the topics you would likely have examined would have been other worlds, because if you said there were no other worlds, it was regarded as limiting God's power."

The popular fascination with aliens took off with the publication of "Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds," by French author Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle in 1686, says Smith. Considered the first scientific blockbuster in publishing history, it was read by many people at the time and is still in print today after almost 100 editions.

The best English translation of the text, according to Smith, was done by a former U of A English professor and science fiction writer, H.A. Hargreaves, in 1990.

Considered one of the first major works of the Enlightenment, it was partly inspired by Copernicus' revolutionary discovery that Earth revolved around the sun, rather than the other way around. That shift in cosmology allowed for the possibility of other solar systems, and therefore other worlds.

By the 18th century, "The great majority of educated people probably believed in life on other worlds," says Smith.

The popularity of "Conversations" and the idea of extraterrestrial life increased well into the 19th century, fueling a hot debate between two major intellects of the age—scientist David Brewster and Anglican minister and philosopher of science William Whewell. That debate "spawned a huge body of literature," says Smith, including perhaps the most famous alien invasion tale of all time: H.G. Wells' 1897 "War of the Worlds," which left its indelible mark well into the 20th century.

Wells' novel was widely seen as a reflection of anxiety over British imperialism. The author once said the story was prompted by a discussion with his brother about the brutal British colonization of Tasmania; he wondered what would happen if Martians treated England the same way.

War of the Worlds tapped into a fundamental human fear, famously manifested when the 1938 CBS Radio version narrated by Orson Welles reportedly caused panic among some listeners who didn't realize it was fiction.

For the most part, says Smith, interest in aliens dropped off slightly in the first half of the 20th century as astronomers surmised that solar systems were relatively rare. But the mania picked up again with the space race of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

"As soon as we sent a spacecraft into space, we were thinking about the implications of that," says Smith. "Remember, the Americans actually celebrated their bicentennial in part by looking for life on Mars (with the launch of Viking 1 in 1976)."

Since then, interest in aliens has been relentless and pervasive, with a flood of movies attesting to our fascination with all things extraterrestrial, from "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," "Star Trek" and "2001: A Space Odyssey" to "Alien," "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," "The X-Files" and "Dr. Who." And that barely scratches the surface.

After taking the long view, does Smith believe in the existence of extraterrestrials? He prefers to defer to the great science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke. "Two possibilities exist: Either we are alone in the universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying."

IMAGE: "Alien: Romulus" — the seventh film in the long-running franchise — is the latest example of how humans depict extraterrestrials as objects of both fascination and dread. Credit: Disney

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the world at large, people who are able to free themselves from this self-centered way of thinking are truly uncommon. Above all, when one stands to gain or lose, it is exceptionally difficult to step outside of oneself and make correct judgments, and thus one could say that people who are able to think Copernicus-style even about these things are exceptionally great people. Most people slip into a self-interested way of thinking, become unable to understand the facts of the matter, and end up seeing only that which betters their own circumstances.

Genzaburo Yoshino, How Do You Live? (translated by Bruno Navasky)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On the ground below, colors in the phalanx began to shift and move. Complicated and detailed circuit patterns appeared and gradually filled the entire formation. Ten minutes later the army had made a thirty-six kilometer square computer motherboard.

Von Neumann pointed to the gigantic human circuit below the pyramid and began to explain, 'Your Imperial Majesty, we have named this computer Qin I. Look, there in the center is the CPU, the core computing component, formed from your five best divisions. By referencing this diagram, you can locate the adders, registers, and stack memory. The part around it that looks highly regular is the memory. When we built that part, we found that we didn't have enough soldiers. But luckily, the work done by the elements in this component is the simplest, so we trained each soldier to hold more colored flags. Each man can now complete the work that initially required twenty men. This allowed us to increase the memory capacity to meet the minimum requirements for running the Qin 1.0 operating system. Observe also the open passage that runs through the entire formation, and the light cavalry waiting for orders in that passage. That's the system bus, responsible for transmitting information between the components of the whole system.

'The bus architecture is a great invention. New plug-in components, which can be made from up to ten divisions, can quickly be added to the main operation bus. This allows Qin I's hardware to be easily expanded and upgraded. Look further still - you might have to use the telescope for this - and there's the external storage, which we call the 'hard drive' at Copernicus's suggestion. It's formed by three million soldiers with more education than most. When you buried all those scholars alive after you unified China, it's a good thing you saved these ones! Each of them holds a pen and a notepad, and they're responsible for recording the results of the calculations. Of course, the bulk of their work is to act as virtual memory and store intermediate calculation results. They're the bottleneck for the speed of computation. And, finally, the part that's closest to us is the display. It's capable of showing us in real time the most important parameters of the computation.'"

- from Cixin Liu's The Three-Body Problem, translated by Ken Liu

#it's a fucking human computer#literally!#just the visual of this#i want to take a class of children and organize them into a computer#make some NAND and NOR gates out of them#brilliant#just brilliant#cixin liu#the three-body problem#ken liu#books#reading#quotes#translation#translated works#computers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Draco coils around the north celestial pole, as depicted in 'Urania’s Mirror', a set of constellation cards published in London.

Illustrator: Sidney Hall, c.1824.

Check the following information which I've cobbled together from a number of sources:

In the 2nd century CE, the astronomer Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus of Alexandria, c. 100 – c. 170 AD) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European, Byzantine and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming one of the most influential astrological and astronomical texts until Polish-born Nicolaus Copernicus (1471 - 1543) formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its centre.

One of the constellations included in this treatise was Draco, which is located in the northern hemisphere and contains the north ecliptic pole*. Today, it is one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and is bordered by the following constellations:

Boötes - name derives from ancient Greek via Latin, meaning 'ox-driver', 'herdsman', 'plowman'.

Camelopardalis - the etymology of this constellation derives from the Latinization of the Greek for 'giraffe' and 'camel'

Cepheus - named after a king of Aethiopia in Greek mythology

Cygnus - ("the Swan") the name can be traced back to various myth regarding swans

Hercules - named after the Roman mythological hero based upon Greek hero, Herakles

Lyra - often represented on star maps as a vulture or an eagle carrying a stringed musical instrument known as a lyre

Ursa Minor ('The Little Bear')

Ursa Major ('The Great Bear')

The name 'Draco' translates from the Latin for 'dragon'. To the ancient Greeks, Draco was associated with Ladon, the mythical dragon who guarded the golden apples of Hesperides. As part of his twelve labours, Heracles killed Ladon and stole the golden apples, which is why the Hercules constellation appears near Draco in the night sky, with the Greek hero treading on the dragon's head with his foot.

The link above is from the website 'In-The-Sky.org' which was founded by Dominic Ford, a Senior Research Associate at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge UK. The page provides information about the constellation Draco. I suggest you visit it and scroll down to the second picture. It shows Draco as it appears to the unaided eye, and then if you roll your mouse over it, you will see labels of all the constellations in that area of the sky. PS: I am bookmarking this excellent website for future reference.

*The ecliptic is the plane on which Earth orbits the Sun. The ecliptic poles are the two points where the ecliptic axis, the imaginary line perpendicular to the ecliptic, intersects the celestial sphere. (Truthfully, I must admit I don't really understand this, it is too complicated for my brain to comprehend!).

The two ecliptic poles are mapped below. Map from study.com website.

0 notes

Text

"History is made productive and meaningful if, despite its difference from the present, it informs how people think about their world."

- Alison Landsberg, Engaging the Past: Mass Culture and the Production of Historical Knowledge

About Me

My name is Tombstone and I study the history of science, religion, and death in the late Middle Ages and Early Modern period in Western Europe. I am interested in the intersection of science and religion (mostly Christianity but with special regard for the role of Judaism and Islam in the preservation, translation, and dissemination of ancient thought) from the 1200s, when the first universities were founded, to the 1700s, the dawn of the Scientific Revolution. I study these cultural shifts through the lens of death, dying, and remembrance.

Introduction to Historical European Scientific and Religious Reading Material

This list is taken mostly from my own bookshelf and class syllabi, with some contributions from scholarly journals and other academic sources. While I have read the majority of them, I cannot vouch for everything on this list, and part of academia is using your own critical thinking to determine which side of an argument you fall on. History is brilliantly multi-faceted, largely subjective in the face of an incalculable number of unknowns, and constantly expanding. As such, this list will be periodically updated and modified. Happy reading!

General Information

Books:

DECKARD, MICHAEL FUNK, and PÉTER LOSONCZI, eds. Philosophy Begins in Wonder: An Introduction to Early Modern Philosophy Theology and Science. 1st ed. The Lutterworth Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cgfbss.

Evans, John H. Morals Not Knowledge: Recasting the Contemporary U.S. Conflict between Religion and Science. 1st ed. University of California Press, 2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt2204r5c.

History of Science

Books:

Briggs, Robin. The Scientific Revolution of the Seventeenth Century. Seminar Studies in History. Edited by Patrick Richardson. London: Longman Group Limited, 1969.

Cohen, H. Floris. How Modern Science Came into the World: Four Civilizations, One 17th-Century Breakthrough. Amsterdam University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt45kddd.

Falk, Seb. The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2020.

Gabriele, Matthew, and David M. Perry. The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2022.

Hannam, James. God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science. London: Icon Books Ltd., 2010.

Strathern, Paul. The Other Renaissance: From Copernicus to Shakespeare. London: Atlantic Books, 2024.

Articles:

Goulding, Robert. “Histories of Science in Early Modern Europe: Introduction.” Journal of the History of Ideas 67, no. 1 (2006): 33–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3840398.

Harrison, Peter. “Curiosity, Forbidden Knowledge, and the Reformation of Natural Philosophy in Early Modern England.” Isis 92, no. 2 (2001): 265–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3080629.

Smith, Pamela H. “Art, Science, and Visual Culture in Early Modern Europe.” Isis 97, no. 1 (2006): 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1086/501102.

Smith, Pamela H. “Science on the Move: Recent Trends in the History of Early Modern Science.” Renaissance Quarterly 62, no. 2 (2009): 345–75. https://doi.org/10.1086/599864.

History of Religion

Books:

Cahill, Thomas. Heretics and Heroes: How Renaissance Artists and Reformation Priests Created our World. New York: Anchor Books, 2014.

Jardine, L. (1996). Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance. Macmillan Publishers.

Massing, M. (2022). Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther, and the Fight for the Western Mind. Harper Perennial.

Schama, S. (1987). The Embarrassment of Riches. Random House, Inc.

Spivey, N. (2001). Enduring Creation: Art, Pain and Fortitude. Thames and Hudson.

Watson, R. N. (2006). Back to Nature: The Green and the Real in the Late Renaissance. University of Pennsylvania Press.

History of Death

Books:

Ariès, Philippe. The Hour of Our Death. Translated by Helen Weaver. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1991.

Booth, P., & Tingle, E. (Eds.). (2020). A Companion to Death, Burial, and Remembrance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, c. 1300–1700. Brill Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004443433

Brown, Peter. The Ransom of the Soul: Afterlife and Wealth in Early Western Christianity. Harvard University Press, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvjf9wtn.

Doig, A. (2023). This Mortal Coil: A History of Death. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Hope, V. M. (2009). Roman Death : The Dying and the Dead in Ancient Rome. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. (not technically within the scope of my research, but a fascinating read nonetheless)

Articles:

Ariés, Philippe. “The Reversal of Death: Changes in Attitudes Toward Death in Western Societies.” American Quarterly 26, no. 5 (1974): 536–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711889.

Palgi, Phyllis, and Henry Abramovitch. “Death: A Cross-Cultural Perspective.” Annual Review of Anthropology 13 (1984): 385–417. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2155675.

Dividers by @wethairjoel

#history#bibliography#early modern history#early modern period#early modern europe#middle ages#medieval history#european history#history of science#death#history of death

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Hot Gates and Other Occasional Pieces by William Golding

Most readers know William Golding only as the author of his first novel, Lord of the Flies, which quickly became school literature. Golding wrote eleven other novels, a play and a number of essays, some of which were collected in two volumes. The first collection, The Hot Gates and Other Occasional Pieces, was published in 1965 and showcases the originality of Golding’s thinking.

The essay that gave the book its title is about a trip to the Hot Gates in Greece, where Leonidas and an army of Spartans made their famous last stand against the Persian army. Nature and farmers have transformed the surroundings of the battle field; Golding remarks, “If you go to the Hot Gates, take some historical knowledge and your imagination with you.” And that is what he did. The other essays that make up the book’s first part are about subjects as diverse as personal crosses, the English Channel, Stratford, Copernicus, Golding’s experiences as amateur archaeologist and his early fascination with Egypt. The essay about Stratford takes a look at the Shakespeare Industry and the mass tourism in the Bard’s birthplace. Visiting the buildings that have some sort of connection with Shakespeare can be disappointing: “Very soon, among the thatch and the half-timber, the paneling and wattle, you begin to feel frustrated because these places, although connected with the name you know, illuminating nothing, put you in touch with nothing.”

The second part of the book begins with an essay titled “Fable”. It is an expanded version of a lecture on Lord of the Flies that Golding first gave in 1962 and that answered some of the questions that students often asked about the novel. It explains what Golding tried to achieve but also points out that he had given up his earlier belief that the author has any authority about the meaning of his works once they are published.

The other writings in the same section of the book are mainly reviews of novels he had read when he was younger, such as The Swiss Family Robinson, Treasure Island, several of Jules Verne’s novels and Tolstoy’s War and Peace (a review of Constance Garnett’s translation). The last essay in this section is about education, especially about how education has jumped onto the bandwagon of ‘Science’ at the expense of philosophy, history and aesthetic perception: “Education … is moving … to the world where it is better to be envied than ignored, better to be well-paid than happy, better to be successful than good—better to be vile, than vile-esteemed.” Golding counters, “Our humanity rests on the capacity to make value judgments, unscientific assessments, the power to decide that this is right, that wrong, this ugly, that beautiful, this just, that unjust. Yet these are precisely the questions which ‘Science’ is not qualified to answer with its measurement and analysis.” One of the side effects of this development is a diminished ability to appreciate literature and “the power of expression in all its richness”.

The third part is inspired by the author’s travels to the USA for lectures at various universities. One of these pieces, “Body and Soul”, describes how his soul is left behind when he travels by jet and his experiences until his soul has caught up are written without any first person pronouns. The last part contains two vivid autobiographical pieces that make you wish Golding had written an entire autobiography. I am looking forward to reading Golding’s second collection of essays, A Moving Target, which was published in 1982.

William Golding: The Hot Gates and Other Occasional Pieces. Faber & Faber, 1965; e-book version, 2013. ISBN 9780571265480.

Review submitted by Tsundoku.

0 notes