#convergent evolution of the horror genre

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

take a drink every time an indie horror game has Subterranean Flesh Tunnels

#mouthwashing#convergent evolution of the horror genre#gynecological horror#I don't hate this game but I also don't want to see it get hyped to oblivion#like it's ok- the characters are cool- the dialogue is good- but I still say this works better as a drama than it manages to actually scare#subterranean animism#subterranean flesh tunnels

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Tumblr fam! 🌸 here with a little journey through the intriguing history of hentai. 📚 Let’s explore the roots in Edo-period shunga art, evolving into the avant-garde ‘ero-guro’ of the 20th century. Fast forward to the gaming boom in the 80s and 90s, giving birth to the iconic ‘eroge’ and ‘hentai anime.’

Shunga, originating during the Edo period, was a fascinating blend of art and sexual expression, often created for the upper class. It served not only as a form of entertainment but also as a medium for sexual education. The later emergence of ‘ero-guro’ challenged societal norms with its explicit depictions of sex, violence, and horror. These underground manga pieces were a rebellion against conventional storytelling, pushing the boundaries of artistic expression in unique ways.

In the digital age, the 80s and 90s witnessed a seismic shift in Japan’s cultural landscape. The rising popularity of video games and anime led to the creation of adult-oriented content, known as ‘eroge.’ As gaming evolved, so did the hentai genre, expanding into ‘hentai anime.’ This convergence paved the way for a diverse range of narratives, exploring not only explicit content but also complex themes and emotions. It’s fascinating to see how this evolution mirrors the broader progression of Japanese media. 🌟

diving deeper into the modern era, the internet has played a pivotal role in the global dissemination of hentai. With online platforms and fan communities, individuals worldwide can access and share this genre. This digital age has democratized the creation and consumption of hentai, fostering a diverse array of artistic expressions and perspectives.

It’s essential to recognize that hentai isn’t a monolithic entity; it spans a spectrum of genres and themes, from the fantastical to the thought-provoking. Some argue it’s a space where taboos are explored, while others see it as an extension of artistic freedom. Navigating these nuanced discussions allows us to appreciate the cultural impact of hentai beyond its explicit nature, acknowledging its role in shaping the broader landscape of anime and manga.

#chubby#curvy body#body positive#big tiddy committee#anime#sexy ebony#ebony#ebonybeauty#ebonycurves#thick ebony#black animation#black anime character#black anime#black anime girl#black tumblr#anime edit#anime manga#anime woman#anime fanart#anime art#anime and manga#anime tiddies#fat anime

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

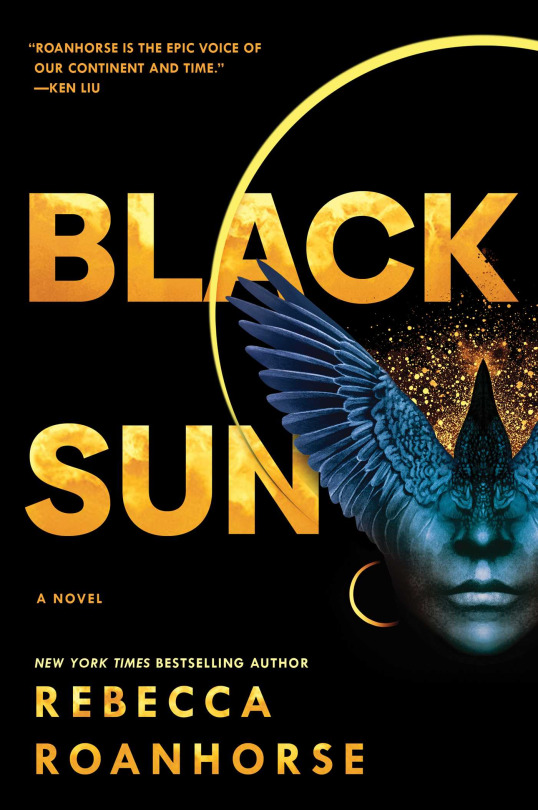

Black Sun. By Rebecca Roanhorse. New York: Saga Press, 2020.

Rating: 3/5 stars

Genre: fantasy

Part of a Series? Yes, Between Earth and Sun #1

Summary: In the holy city of Tova, the winter solstice is usually a time for celebration and renewal, but this year it coincides with a solar eclipse, a rare celestial event proscribed by the Sun Priest as an unbalancing of the world. Meanwhile, a ship launches from a distant city bound for Tova and set to arrive on the solstice. The captain of the ship, Xiala, is a disgraced Teek whose song can calm the waters around her as easily as it can warp a man’s mind. Her ship carries one passenger. Described as harmless, the passenger, Serapio, is a young man, blind, scarred, and cloaked in destiny. As Xiala well knows, when a man is described as harmless, he usually ends up being a villain.

***Full review under the cut.***

Content Warnings: blood, violence, gore, body horror, drug/alcohol use, self-harm, suicide, mutilation, reference to child sex slavery

Overview: I came across this book while looking for fantasy novels set in non-European-inspired worlds. I got really exited about the premise: a pre-Columbian, indigenous-inspired story? With multiple perspectives? And crows? It sounded great! Unfortunately, I couldn’t give this book more than 3 stars for a number of reasons: I felt like the writing could have been a little bit better and that character motivations could have been more clear; and I ultimately didn’t feel like the story was a true race-against-the-clock until the end. While I’m intrigued enough to pick up book 2 in the series, I do wish this book had done a little more to make me feel connected to the plot and the characters.

Writing: Roanhorse’s writing reminds me of some New Adult prose styles: it feels straight-forward, clear, and well-balanced, but sometimes tends to tell more than show, especially when it comes to emotion. I really liked that I could follow the prose without issue, but I often felt like Roanhorse was dumping some info on me and expecting me to absorb it right away. For example, Xiala (one of the protagonists) tells us that she’s always felt like an outsider and that’s why she has such an immediate connection with Serapio (another protagonist), but I didn’t exactly feel that. There were also some worldbuilding details that seemed to be inserted to flesh out the world - which was great - but ultimately didn’t feel relevant to what was going on in the plot.

This book is also told from multiple perspectives and flashes forward and backward in time. While I personally was able to follow the voices and time skips just fine, some readers might find it a challenge.

Also, without spoiling anything, the end of this book seemed to rush by WAY too fast, and I honestly didn’t feel like most of the book was building to it.

The worldbuilding, however, was wonderful. I really liked the way Roanhorse described the look and feel of everything from the tastes, smells, sights, etc. and I loved how diverse and rich everything felt. While I don’t know enough about various Indigenous groups to comment on whether or not the cultural elements were incorporated well, I did like that various populations didn’t seem to be monoliths and varied in terms of social structure, dress, and custom.

Plot: The plot of this book follows two-ish threads: in one thread, Xiala must get Serapio to the city of Tova in time for “the Convergence,” a time when the celestial bodies are aligned AND there’s a lunar eclipse. In the other, Naranpa must navigate a plot to oust her from the priesthood while also dealing with rising opposition from clan Carrion Crow (and their cultists, with whom Okoa is involved).

Because of the many POV characters and the flashbacks in time, it was difficult to feel any sense of urgency in either plot thread. Xiala and Serapio’s thread was a travel narrative, and most of the conflict stemmed from the fact that the crew just straight up did not trust Xiala. At first, I thought we were getting a narrative where the crew mistrusts Xiala because she’s Teek, but then they appear to be ok with her in what was a pleasant subversion of my expectations. But then something happens and we’re back to what I expected, and it proves inconvenient for getting Serapio to Tova in time. Because I didn’t feel like I had much of a reason to want Xiala and Serapio to succeed (Serapio’s motivations are mysterious and Xiala mostly wants wealth), I felt pretty “meh” about them potentially missing their deadline. I would have much rather seen Xiala (and perhaps the crew?) be challenged and grow from the setbacks she experiences at sea, and for her to become more personally connected to Serapio so the journey shifts from one done to earn untold wealth to one where Xiala wants to help her friend (even if said friend ends up being deceptive).

The Tovan plot is likewise a little “meh” because there wasn’t a huge sense of urgency or suspense. I felt like I didn’t know the clans enough to feel strongly about their politics (aside from understanding that killing people is bad in the abstract), nor did I have a concrete reason for wanting the institution of the priesthood to remain (once I learned more of their history and the fact that most priests - called “Watchers” - would rather be elitist than minister to the people).

Perhaps that’s why I felt a little underwhelmed by the plot as a whole: while things certainly happened, I ultimately didn’t feel like they impacted the characters’ inner lives much, or if they did, that evolution was told to us more than shown. While I understand that Black Sun is the first book in a series, I still would have liked the plot to have more of an impression on the characters.

Characters: I think it’s safe to say that this book follows 4 main protagonists: Xiala (a Teek sea captain who fills the Han Solo archetype), Serapio (the mysterious blind man with crow-themes magic powers), Naranpa (the Sun Priest who struggles against traditionalists to make the priesthood more active in people’s lives), and Okoa (the son of the murdered Carrion Crow clan matriarch). While I liked all of these characters, I do wish they had been a little less dependent on archetypes (lusty sea captain, Chosen One, etc). Maybe things will change as they develop in later novels, but for now, they’re fun and certainly likeable in their own ways, but not mind-blowing.

Xiala is likeable in that she’s a hot mess with a heart of gold. She drinks, swears, and gets into trouble, all in the pursuit of earning enough wealth to make a living. She is also Teek - a member of a (rumored) all-female island clan, whose members have special sea-based magic. I liked Xiala’s connection to the sea and the way she communicates her people’s stories and cultural values. However, I do wish she was challenged a little more to want something more than material reward.

Serapio is an intriguing character in that he fits the archetype of dark, mysterious Chosen One. While I appreciated that he wasn’t a gruff loner (instead, he seemed eager to connect with people while recognizing that his appearance might unsettle them), I also think his backstory is a little too “edgy” for my tastes. His motivations were somewhat shrouded in mystery, which made it hard to know whether or not I wanted to root for him to succeed, but because he’s not a complete jerk, I found him interesting enough.

The connection between Xiala and Serapio could have been a lot stronger than it was. While I liked that they bonded over their “outsider” statuses, I ultimately felt like this was told to us rather than shown. Thus, when they kind of sort of “get together” later in the novel, it doesn’t feel earned. I didn’t understand what Xiala saw in Serapio other than his physical attractiveness and (maybe?) feeling like he didn’t treat her as a foreigner. While fine, I wanted Xiala to be more attracted to Serapio’s personal qualities, not just that he was nice to her. Same thing for Serapio: I didn’t get the sense that he had genuine feelings for Xiala personally, just that she was intriguing because she was Teek.

Naranpa, the Sun Priest, was an interesting figure in that she was caught up in the politics of the priesthood. While I liked watching her navigate the various setbacks and conflicts with traditionalists, I ultimately wish I had been given a more compelling reason to root for Naranpa to succeed. Trying to make the priesthood more hands-on and philanthropic is all well and good, but it felt too abstract. I wanted Naranpa to have more personal stakes - because she comes from the “gutters” of the city, is she more invested? But if so, how does she reconcile that with her decades-long absence from where she grew up? There was a little of that, but ultimately, I didn’t feel like I had a reason to want the priesthood to continue. I didn’t understand why Naranpa was so attached to the priesthood as an institution; why didn’t didn’t she cut her losses and go elsewhere?

Okoa is something of a late addition. His perspective doesn’t appear right away, but I think that worked out fine, considering when it appeared. Okoa is a warrior who finds himself torn between keeping peace between his clan and the Priesthood and joining a rebellious cult who wants to restore the old religion and seek revenge against the Priesthood for past trauma. While I think his perspective was important, I didn’t personally feel invested in this plot or Okoa’s dilemma. Perhaps it’s because I didn’t feel like the rebels were treated as having a real grievance; we’re told about the past and told that it was harmful, but because we don’t get the perspective of someone dedicated to the Cause, I didn’t feel like I could sympathize with it. Okoa himself is resistant, calling the rebels “cultists” and saying that though he understands their grief, he doesn’t want to support violence. Perhaps if Okoa felt threatened by the cultists, or if their cause was a true threat to the stability and well-being of the clan, then I could feel more involved. But as it stands, Okoa was somewhat wishy-washy, and I couldn’t quite understand the stakes to make his indecision feel justified.

Side or supporting characters were interesting. I really liked that Roanhorse included plenty of queer characters, including trans and non-binary/third gender characters who use pronouns like xe/xir. My favorite was probably Iktan, the head of what is essentially the assassin’s branch of the priesthood.

TL;DR: Black Sun is an intriguing fantasy with intricate worldbuilding and premise. While I personally felt like the inner lives of the characters could have been more developed and the plot more compelling, I think this book (and author) will satisfy many fantasy lovers, and I look forward to picking up the next novel in the series.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

DURING THE POSTWAR PERIOD, the genres of the fantastic — especially science fiction — have been deeply intertwined with the genres of popular music, especially rock ’n’ roll. Both appeal to youthful audiences, and both make the familiar strange, seeking escape in enchantment and metamorphosis. As Steppenwolf sang in 1968: “Fantasy will set you free […] to the stars away from here.” Two recent books — one a nonfiction survey of 1970s pop music, the other a horror novel about heavy metal — explore this heady intermingling of rock and the fantastic.

As Jason Heller details in his new book Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded, the magic carpet rides of the youth counterculture encompassed both the amorphous yearnings of acid rock and the hard-edged visions of science fiction. In Heller’s account, virtually all the major rock icons — from Jimi Hendrix to David Crosby, from Pete Townshend to Ian Curtis — were avid SF fans; not only was their music strongly influenced by Heinlein, Clarke, Ballard, and other authors, but it also amounted to a significant body of popular SF in its own right. As Heller shows, many rock stars were aspiring SF writers, while established authors in the field sometimes wrote lyrics for popular bands, and a few became rockers themselves. British fantasist Michael Moorcock, for example, fronted an outfit called The Deep Fix while also penning songs for — and performing with — the space-rock group Hawkwind (once memorably described, by Motörhead’s Lemmy Kilmister, as “Star Trek with long hair and drugs”).

Heller’s book focuses on the “explosion” of SF music during the 1970s, with chapters chronicling, year by year, the exhilarating debut of fresh music subcultures — prog rock, glam rock, Krautrock, disco — and their saturation with themes of space/time travel, alien visitation, and futuristic (d)evolution. He writes, “’70s pop culture forged a special interface with the future.” Many of its key songs and albums “didn’t just contain sci-fi lyrics,” but they were “reflection[s] of sci-fi” themselves, “full of futuristic tones and the innovative manipulation of studio gadgetry” — such as the vocoder, with its robotic simulacrum of the human voice. Heller’s discussion moves from the hallucinatory utopianism of the late 1960s to the “cool, plastic futurism” of the early 1980s with intelligence and panache.

The dominant figure in Heller’s study is, unsurprisingly, David Bowie, the delirious career of whose space-age antihero, Major Tom, bookended the decade — from “Space Oddity” in 1969 to “Ashes to Ashes” in 1980. Bowie’s 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars was a full-blown SF extravaganza, its freaky starman representing “some new hybrid of thespian rocker and sci-fi myth,” but it had a lot of company during the decade. Heller insightfully analyzes a wide range of SF “concept albums,” from Jefferson Starship’s Blows Against the Empire (1970), the first rock record to be nominated for a Hugo Award, to Parliament’s Mothership Connection (1975), which “reprogramm[ed] funk in order to launch it into tomorrow,” to Gary Numan and Tubeway Army’s Replicas (1979), an album “steeped in the technological estrangement and psychological dystopianism of Dick and Ballard.”

Heller’s coverage of these peaks of achievement is interspersed with amusing asides on more minor, “novelty” phenomena, such as “the robot dance craze of the late ’60s and early ’70s,” and compelling analyses of obscure artists, such as French synthesizer wizard Richard Pinhas, who released (with his band Heldon) abrasive critiques of industrial society — for example, Electronique Guerilla (1974) — while pursuing a dissertation on science fiction under the direction of Gilles Deleuze at the Sorbonne. He also writes astutely about the impact of major SF films on the development of 1970s pop music: Monardo’s Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk (1977), for example, turned the cantina scene from Star Wars into a synth-pop dance-floor hit. At the same time, Heller is shrewdly alert to the historical importance of grassroots venues such as London’s UFO Club, which incubated the early dimensional fantasies of Pink Floyd and the off-the-wall protopunk effusions of the Deviants (whose frontman, Mick Farren, had a long career as an SF novelist and, in 1978, released an album with my favorite title ever: Vampires Stole My Lunch Money). Finally, Heller reconstructs some fascinating, but sadly abortive, collaborations — Theodore Sturgeon working to adapt Crosby, Stills & Nash’s “Wooden Ships” as a screenplay, Paul McCartney hiring Star Trek’s Gene Roddenberry to craft a story about Wings. In some alternative universe, these weird projects came to fruition.

Heller’s erudition is astonishing, but it can also be overwhelming, drowning the reader in a welter of minutiae about one-hit wonders and the career peregrinations of minor talents. In his acknowledgments, Heller thanks his editor for helping him convert “an encyclopedia” into “a story,” but judging from the format of the finished product, this transformation was not fully complete: penetrating analyses frequently peter out into rote listings of albums and bands. There is a capping discography, but it is not comprehensive and is, strangely, organized by song title rather than by artist. The index is similarly unhelpful, containing only the proper names of individuals; one has to know, for instance, who Edgar Froese or Ralf Hütter are in order to locate the relevant passages on Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk, respectively.

That said, there is no gainsaying the magisterial authority displayed in assertions such as: “The first fully formed sci-fi funk song was ‘Escape from Planet Earth’ by a vocal quartet from Camden, New Jersey, called the Continental Four.” And who else has even heard of — much less listened to — oddments like 1977’s Machines, “the sole album by the mysterious electronic group known as Lem,” who “likely took their name from sci-fi author Stanislaw Lem of Solaris fame”? Anyone interested in either popular music or science fiction of the 1970s will find countless nuggets of sheer delight in Strange Stars, and avid fans, after perusing the volume, will probably go bankrupt hunting down rare vinyl on eBay.

While Heller’s main focus is the confluence of rock ’n’ roll and science fiction, he occasionally addresses the influence of popular fantasy on major music artists of the decade. Marc Bolan, of T. Rex fame, was, we learn, a huge fan of Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, while prog-rock stalwarts Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer managed “to combine science fiction and fantasy, fusing them into a metaphysical, post-hippie meditation on the nature of reality.” What’s missing from the book, however, is any serious discussion of the strain of occult and dark fantasy that ran through 1960s and ’70s rock, the shadows cast by Aleister Crowley and H. P. Lovecraft over Jimmy Page, John Lennon, Mick Jagger, and (yes) Bowie himself. After all, Jim Morrison’s muse was a Celtic high priestess named Patricia Kennealy who went on, following the death of her Lizard King, to a career as a popular fantasy author. Readers interested in this general topic should consult the idiosyncratic survey written by Gary Lachman, a member of Blondie, entitled Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius (2001).

Heller does comment, in passing, on an incipient musical form that would, during the 1980s, emerge as the dark-fantasy genre par excellence: heavy metal. Though metal was, as Heller states, “just beginning to awaken” in the 1970s, his book includes sharp analyses of major prototypes such as Black Sabbath’s Paranoid (1970), Blue Öyster Cult’s Tyranny and Mutation (1973), and the early efforts of Judas Priest and Iron Maiden. This was the technocratic lineage of heavy metal, the segment of the genre most closely aligned with science fiction, especially in its dystopian modes, and which would come to fruition, during the 1980s, in classic concept albums like Voivod’s Killing Technology (1987) and Queensrÿche’s Operation: Mindcrime (1988).

But the 1980s also saw the emergence of more fantasy-oriented strains, such as black, doom, and death metal, whose rise to dominance coincided with the sudden explosion in popularity of a fantastic genre that had, until that time, largely skulked in the shadow of SF and high fantasy: supernatural horror. Unsurprisingly, the decade saw a convergence of metal music and horror fiction that was akin to the 1970s fusion of rock and SF anatomized in Strange Stars. Here, as elsewhere, Black Sabbath was a pioneer, their self-titled 1970 debut offering a potent brew of pop paganism culled equally from low-budget Hammer films and the occult thrillers of Dennis Wheatley. By the mid-1980s, there were hundreds of bands — from Sweden’s Bathory to England’s Fields of the Nephilim to the pride of Tampa, Florida, Morbid Angel — who were offering similar fare. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos inspired songs by Metallica, Mercyful Fate, and countless other groups — including Necronomicon, a German thrash-metal outfit whose name references a fictional grimoire featured in several of the author’s stories.

By the same token, heavy metal music deeply influenced the burgeoning field of horror fiction. Several major 1980s texts treated this theme overtly: the doom-metal outfit in George R. R. Martin’s The Armageddon Rag (1983) is a twisted emanation of the worst impulses of the 1960s counterculture; the protagonist of Anne Rice’s The Vampire Lestat (1985) is a Gothic rocker whose performances articulate a pop mythology of glamorous undeath; and the mega-cult band in John Skipp and Craig Spector’s splatterpunk classic The Scream (1988) are literal hell-raisers, a Satanic incarnation of the most paranoid fantasies of Christian anti-rock zealots. The heady conjoining of hard rock with supernaturalism percolated down from these best sellers to the more ephemeral tomes that packed the drugstore racks during the decade, an outpouring of gory fodder affectionately surveyed in Grady Hendrix’s award-winning study Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction (2017). Hendrix, himself a horror author of some note, has now published We Sold Our Souls (2018), the quintessential horror-metal novel for our times.

Hendrix has stated that, prior to embarking on this project, he was not “a natural metal fan”:

I was scared of serious metal when I was growing up. Slayer and Metallica intimidated me, and I was too unsophisticated to appreciate the fun of hair metal bands like Mötley Crüe and Twisted Sister, so I basically sucked. […] But I got really deep into metal while writing We Sold Our Souls and kind of fell in love.

The author’s immersion in — and fondness for — the genre is evident on every page of his new novel. Chapters are titled using the names of classic metal albums: “Countdown to Extinction” (Megadeth, 1992), “From Enslavement to Obliteration” (Napalm Death, 1988), “Twilight of the Gods” (Bathory, 1991), and so on. The effect is to summon a hallowed musical canon while at the same time evoking the story’s themes and imparting an emotional urgency to its events. These events also nostalgically echo 1980s rock-horror novels: like The Armageddon Rag, Hendrix’s plot chronicles the reunion of a cult outfit whose breakup decades before was enigmatically fraught; like The Scream, it features a demonic metal band that converts its worshipful fans into feral zombies; like The Vampire Lestat, it culminates in a phantasmagoric stadium concert that erupts into a brutal orgy of violence. Yet despite these pervasive allusions, the novel does not come across as mere pastiche: it has an energy and authenticity that make it feel quite original.

A large part of that originality lies in its protagonist. As the cock-rock genre par excellence, its blistering riffs and screeching solos steeped in adolescent testosterone, heavy metal has had very few notable female performers. But one of them, at least in Hendrix’s fictive history, was Kris Pulaski, lead guitarist of Dürt Würk, a legendary quintet from rural Pennsylvania that abruptly dissolved, under mysterious circumstances, in the late 1990s, just as they were poised for national fame. Kris was a scrappy bundle of nerves and talent, a kick-ass songwriter and a take-no-prisoners performer:

She had been punched in the mouth by a straight-edge vegan, had the toes of her Doc Martens kissed by too many boys to count, and been knocked unconscious after catching a boot beneath the chin from a stage diver who’d managed to do a flip into the crowd off the stage at Wally’s. She’d made the mezzanine bounce like a trampoline at Rumblestiltskins, the kids pogoing so hard flakes of paint rained down like hail.

But that was eons ago. As the story opens, she is staffing the night desk at a Best Western, burned out at 47, living in a broken-down house with her ailing mother and trying to ignore “the background hum of self-loathing that formed the backbeat of her life.” She hasn’t seen her bandmates in decades, since she drunkenly crashed their tour van and almost killed them all, and hasn’t picked up a guitar in almost as long, constrained by the terms of a draconian contract she signed with Dürt Würk’s former lead singer, Terry Hunt, who now controls the band’s backlist. While Kris has lapsed into brooding obscurity, Hunt has gone on to global success, headlining a “nu metal” outfit called Koffin (think Korn or Limp Bizkit) whose mainstream sound Kris despises: “It was all about branding, fan outreach, accessibility, spray-on attitude, moving crowds of white kids smoothly from the pit to your merch booth.” It was the exact opposite of genuine metal, which “tore the happy face off the world. It told the truth.”

To inject a hint of authenticity into Koffin’s rampant commodification, Hunt occasionally covers old Dürt Würk hits. But he avoids like the plague any songs from the band’s long-lost third album, Troglodyte, with their elaborate mythology of surveillance and domination:

[T]here is a hole in the center of the world, and inside that hole is Black Iron Mountain, an underground empire of caverns and lava seas, ruled over by the Blind King who sees everything with the help of his Hundred Handed Eye. At the root of the mountain is the Wheel. Troglodyte was chained to the Wheel along with millions of others, which they turned pointlessly in a circle, watched eternally by the Hundred Handed Eye.

Inspired by the arrival of a butterfly that proves the existence of a world beyond his bleak dungeon, Troglodyte ultimately revolts against Black Iron Mountain, overthrowing the Blind King and leading his fellow slaves into the light.

One might assume that Hunt avoids this album because the scenario it constructs can too readily be perceived as an allegory of liberation from the consumerist shackles of Koffin’s nu-metal pablum. That might be part of the reason, but Hunt’s main motivation is even more insidious: he fears Troglodyte because its eldritch tale is literally true — Koffin is a front for a shadowy supernatural agency that feeds on human souls, and Dürt Würk’s third album holds the key to unmasking and fighting it. This strange reality gradually dawns on Kris, and when Koffin announces plans for a massive series of concerts culminating in a “Hellstock” festival in the Nevada desert, she decides to combat its infernal designs with the only weapon she has: her music. Because “a song isn’t a commercial for an album. It isn’t a tool to build name awareness or reinforce your brand. A song is a bullet that can shatter your chains.”

This bizarre plot, like the concept albums by Mastodon or Iron Maiden it evokes, runs the risk of collapsing into grandiloquent absurdity if not carried off with true conviction. And this is Hendrix’s key achievement in the novel: he never condescends, never winks at the audience or tucks his tongue in cheek. Like the best heavy metal, We Sold Our Souls is scabrous and harrowing, its pop mythology fleshed out with vividly gruesome set pieces, as when Kris surprises the Blind King’s minions at their ghastly repast:

Its fingernails were black and it bent over Scottie, slobbering up the black foam that came boiling out of his mouth. Kris […] saw that the same thing was crouched over Bill, a starved mummy, maggot-white, its skin hanging in loose folds. A skin tag between its legs jutted from a gray pubic bush, bouncing obscenely like an engorged tick. […] Its gaze was old and cold and hungry and its chin dripped black foam like a beard. It sniffed the air and hissed, its bright yellow tongue vibrating, its gums a vivid red.

The irruption of these grisly horrors into an otherwise mundane milieu of strip malls and franchise restaurants and cookie-cutter apartments is handled brilliantly, on a par with the best of classic splatterpunk by the likes of Joe R. Lansdale or David J. Schow.

Hendrix also, like Stephen King, has a shrewd feel for true-to-life relationships, which adds a grounding of humanity to his cabalistic flights. Kris’s attempts to reconnect with her alienated bandmates — such as erstwhile drummer JD, a wannabe Viking berserker who has refashioned his mother’s basement into a “Metalhead Valhalla” — are poignantly handled, and the hesitant bond she develops with a young Koffin fan named Melanie has the convincing ring of post-feminist, intergenerational sisterhood. Throughout the novel, Hendrix tackles gender issues with an intrepid slyness, from Kris’s brawling tomboy efforts to fit into a male-dominated world to Melanie’s frustration with her lazy, lying, patronizing boyfriend, with whom she breaks up in hilarious fashion:

She screamed. She broke his housemate’s bong. She Frisbee-d the Shockwave [game] disc so hard it left a divot in the kitchen wall. She raged out of the house as his housemates came back from brunch.

“Dude,” they said to Greg as he jogged by them, “she is so on the rag.”

“Are we breaking up?” Greg asked, clueless, through her car window.

It took all her self-control not to back over him as she drove off.

Such scenes of believable banality compellingly anchor the novel’s febrile horrors, as do the passages of talk-radio blather interspersed between the chapters, which remind us that conspiratorial lunacy is always only a click of the AM dial away.

While obviously a bit of a throwback, We Sold Our Souls shows that the 1980s milieu of heavy metal and occult horror — of bootleg cassettes and battered paperbacks — continues to have resonance in our age of iPods and cell-phone apps. It also makes clear that the dreamy confluence of rock and the fantastic so ably anatomized in Heller’s Strange Stars is still going strong.

¤

Rob Latham is a LARB senior editor. His most recent book is Science Fiction Criticism: An Anthology of Essential Writings, published by Bloomsbury Press in 2017.

The post Magic Carpet Rides: Rock Music and the Fantastic appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://bit.ly/2SMN28U via IFTTT

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EALING GOES DARK by Nathaniel Thompson

If you’ve been sticking around these Streamline parts for a while, it’s no secret that one of my very favorite things to write about is Ealing Studios, the venerable British film factory that became synonymous with hilarious madcap comedies in the ‘50s starring the likes of Alec Guinness and Peter Sellers. However, there’s way, way more to Ealing than that, which shouldn’t be surprising when you consider it actually started in the silent era and ran for six decades before it flourished as both a production company and a shooting facility. The studio was bought by the BBC in 1955, which effectively signaled the end of its golden era until the Ealing name was revived again in the early 2000s. It was also where films like SHAUN OF THE DEAD (2004) was shot, so needless to say, its history is full of surprises.

For some reason, the Ealing output is still barely recognized in the U.S. apart from a tiny handful of key titles, all comedies apart from what is easily the most influential British horror film of all time, DEAD OF NIGHT (‘45). However, Ealing dabbled in almost every conceivable genre and performed some fascinating experiments with them over the course of its lifetime; at least until recently. Its vital role in the evolution of British crime films has usually been downplayed in favor of other biggies including Hammer Films. You can find a couple of Ealing crime gems still undervalued by American audiences in the currently running “Brit Noir” spotlight at FilmStruck, a really diverse and highly worthwhile selection of examples showing how film noir was flourishing across the pond during its heyday in Hollywood. As with America, the zenith here was the decade or so after World War II when the world was still heavily scarred and in shock, gradually rebuilding itself and finding new senses of national identity that weren’t always entirely pretty. Ealing’s noir contributions may have been small in number, but they’re very high in quantity. The studio was no stranger to crime films by the time the postwar wave hit, with dark crime elements driving some of its fascinating but frequently forgotten early offerings like: ESCAPE! (‘30), THE FOUR JUST MEN (‘39), DEATH DRIVES THROUGH (‘35), SALOON BAR (‘40), LABURNUM GROVE (‘36) and BIRDS OF PREY (The Perfect Alibi, ‘30).

IT ALWAYS RAINS ON SUNDAY (‘47) features frequent Ealing star, Googie Withers (the terrified wife in the great haunted mirror segment from DEAD OF NIGHT) as Rose, a married lower-class housewife whose life turns upside down when ex-boyfriend Tommy (John McCallum, soon to be husband of Withers) turns up on her doorstep. Tommy’s just escaped from prison where he’s been doing time for a nasty robbery, and against her better judgment, Rose agrees to hide him out under the noses of her husband and children. If that premise sounds similar to the later Neil Simon comedy Seems Like Old Times well, yeah it is in theory, but the execution and story direction are wholly different as IT ALWAYS RAINS ON SUNDAY follows the course of a single day gone very, very bad. The ending goes about as grim as you could get while still making this safe for the Production Code to carry in the U.S., and both of the leads are quite amazing with performances featuring a kind of raw, carnal intensity at times that you’d never expect to see in a 1947 British film.

A fine companion film—if you’ve got more of an afternoon to spare— and another look at the lower class, POOL OF LONDON (1951), takes place after the rations and rebuilding seen in SUNDAY had become a not-quite-distant memory. Ealing was surprisingly progressive in casting black actors in leading roles, and this is an early example with Earl Cameron, (a Bermuda-born actor seen in such films as THUNDERBALL, ‘65), in his screen debut and given center stage as Johnny, a Jamaican sailor on leave with an American named Dan (Bonar Colleano) who becomes embroiled in smuggling and other criminal activity around the titular dock area. A while back our own Streamline writer Kimberly Lindbergs made a fine case for this film’s value as an early look at race relations on film and a key entry in the filmography of the terrific Basil Dearden (who still hasn’t earned auteur status and perhaps never will, but almost everything he directed is well worth watching).

What I’d like to point out here is how effectively Dearden picks up on the proto-kitchen sink realism that was already seeping into Ealing noir in SUNDAY and brings it to the forefront here, charting two courses that repeatedly converge and diverge over the course of one shore leave in a way that seems both plausible and accurate to the time while also visually inventive enough to rank with other slice-of-life noir studies of the period. For further evidence of Dearden’s underexploited skill with British noir, try (if you can) to see another of his Ealing classics, THE BLUE LAMP (‘50), a more traditional urban thriller starring a very young Dirk Bogarde.

You can even use them as an interesting comparison with the director of SUNDAY, Robert Hamer, who wasn’t one of the more prolific Ealing directors but did make his mark with that film and a very unusual noir-tinged period film, PINK STRING AND SEALING WAX (‘45). If you really want to get ambitious with your home programming, of course, you might also want to toss in Hamer’s most famous film, the Ealing classic KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS (‘49), which may be a comedy classic but also features a body count higher than all of the aforementioned films combined!

#FilmStruck#Ealing Studios#Robert Hamer#It Always Rains on Sunday#Googie Withers#StreamLine Blog#Nathaniel Thompson

22 notes

·

View notes

Link

DURING THE POSTWAR PERIOD, the genres of the fantastic — especially science fiction — have been deeply intertwined with the genres of popular music, especially rock ’n’ roll. Both appeal to youthful audiences, and both make the familiar strange, seeking escape in enchantment and metamorphosis. As Steppenwolf sang in 1968: “Fantasy will set you free […] to the stars away from here.” Two recent books — one a nonfiction survey of 1970s pop music, the other a horror novel about heavy metal — explore this heady intermingling of rock and the fantastic.

As Jason Heller details in his new book Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded, the magic carpet rides of the youth counterculture encompassed both the amorphous yearnings of acid rock and the hard-edged visions of science fiction. In Heller’s account, virtually all the major rock icons — from Jimi Hendrix to David Crosby, from Pete Townshend to Ian Curtis — were avid SF fans; not only was their music strongly influenced by Heinlein, Clarke, Ballard, and other authors, but it also amounted to a significant body of popular SF in its own right. As Heller shows, many rock stars were aspiring SF writers, while established authors in the field sometimes wrote lyrics for popular bands, and a few became rockers themselves. British fantasist Michael Moorcock, for example, fronted an outfit called The Deep Fix while also penning songs for — and performing with — the space-rock group Hawkwind (once memorably described, by Motörhead’s Lemmy Kilmister, as “Star Trek with long hair and drugs”).

Heller’s book focuses on the “explosion” of SF music during the 1970s, with chapters chronicling, year by year, the exhilarating debut of fresh music subcultures — prog rock, glam rock, Krautrock, disco — and their saturation with themes of space/time travel, alien visitation, and futuristic (d)evolution. He writes, “’70s pop culture forged a special interface with the future.” Many of its key songs and albums “didn’t just contain sci-fi lyrics,” but they were “reflection[s] of sci-fi” themselves, “full of futuristic tones and the innovative manipulation of studio gadgetry” — such as the vocoder, with its robotic simulacrum of the human voice. Heller’s discussion moves from the hallucinatory utopianism of the late 1960s to the “cool, plastic futurism” of the early 1980s with intelligence and panache.

The dominant figure in Heller’s study is, unsurprisingly, David Bowie, the delirious career of whose space-age antihero, Major Tom, bookended the decade — from “Space Oddity” in 1969 to “Ashes to Ashes” in 1980. Bowie’s 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars was a full-blown SF extravaganza, its freaky starman representing “some new hybrid of thespian rocker and sci-fi myth,” but it had a lot of company during the decade. Heller insightfully analyzes a wide range of SF “concept albums,” from Jefferson Starship’s Blows Against the Empire (1970), the first rock record to be nominated for a Hugo Award, to Parliament’s Mothership Connection (1975), which “reprogramm[ed] funk in order to launch it into tomorrow,” to Gary Numan and Tubeway Army’s Replicas (1979), an album “steeped in the technological estrangement and psychological dystopianism of Dick and Ballard.”

Heller’s coverage of these peaks of achievement is interspersed with amusing asides on more minor, “novelty” phenomena, such as “the robot dance craze of the late ’60s and early ’70s,” and compelling analyses of obscure artists, such as French synthesizer wizard Richard Pinhas, who released (with his band Heldon) abrasive critiques of industrial society — for example, Electronique Guerilla (1974) — while pursuing a dissertation on science fiction under the direction of Gilles Deleuze at the Sorbonne. He also writes astutely about the impact of major SF films on the development of 1970s pop music: Monardo’s Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk (1977), for example, turned the cantina scene from Star Wars into a synth-pop dance-floor hit. At the same time, Heller is shrewdly alert to the historical importance of grassroots venues such as London’s UFO Club, which incubated the early dimensional fantasies of Pink Floyd and the off-the-wall protopunk effusions of the Deviants (whose frontman, Mick Farren, had a long career as an SF novelist and, in 1978, released an album with my favorite title ever: Vampires Stole My Lunch Money). Finally, Heller reconstructs some fascinating, but sadly abortive, collaborations — Theodore Sturgeon working to adapt Crosby, Stills & Nash’s “Wooden Ships” as a screenplay, Paul McCartney hiring Star Trek’s Gene Roddenberry to craft a story about Wings. In some alternative universe, these weird projects came to fruition.

Heller’s erudition is astonishing, but it can also be overwhelming, drowning the reader in a welter of minutiae about one-hit wonders and the career peregrinations of minor talents. In his acknowledgments, Heller thanks his editor for helping him convert “an encyclopedia” into “a story,” but judging from the format of the finished product, this transformation was not fully complete: penetrating analyses frequently peter out into rote listings of albums and bands. There is a capping discography, but it is not comprehensive and is, strangely, organized by song title rather than by artist. The index is similarly unhelpful, containing only the proper names of individuals; one has to know, for instance, who Edgar Froese or Ralf Hütter are in order to locate the relevant passages on Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk, respectively.

That said, there is no gainsaying the magisterial authority displayed in assertions such as: “The first fully formed sci-fi funk song was ‘Escape from Planet Earth’ by a vocal quartet from Camden, New Jersey, called the Continental Four.” And who else has even heard of — much less listened to — oddments like 1977’s Machines, “the sole album by the mysterious electronic group known as Lem,” who “likely took their name from sci-fi author Stanislaw Lem of Solaris fame”? Anyone interested in either popular music or science fiction of the 1970s will find countless nuggets of sheer delight in Strange Stars, and avid fans, after perusing the volume, will probably go bankrupt hunting down rare vinyl on eBay.

While Heller’s main focus is the confluence of rock ’n’ roll and science fiction, he occasionally addresses the influence of popular fantasy on major music artists of the decade. Marc Bolan, of T. Rex fame, was, we learn, a huge fan of Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, while prog-rock stalwarts Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer managed “to combine science fiction and fantasy, fusing them into a metaphysical, post-hippie meditation on the nature of reality.” What’s missing from the book, however, is any serious discussion of the strain of occult and dark fantasy that ran through 1960s and ’70s rock, the shadows cast by Aleister Crowley and H. P. Lovecraft over Jimmy Page, John Lennon, Mick Jagger, and (yes) Bowie himself. After all, Jim Morrison’s muse was a Celtic high priestess named Patricia Kennealy who went on, following the death of her Lizard King, to a career as a popular fantasy author. Readers interested in this general topic should consult the idiosyncratic survey written by Gary Lachman, a member of Blondie, entitled Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius (2001).

Heller does comment, in passing, on an incipient musical form that would, during the 1980s, emerge as the dark-fantasy genre par excellence: heavy metal. Though metal was, as Heller states, “just beginning to awaken” in the 1970s, his book includes sharp analyses of major prototypes such as Black Sabbath’s Paranoid (1970), Blue Öyster Cult’s Tyranny and Mutation (1973), and the early efforts of Judas Priest and Iron Maiden. This was the technocratic lineage of heavy metal, the segment of the genre most closely aligned with science fiction, especially in its dystopian modes, and which would come to fruition, during the 1980s, in classic concept albums like Voivod’s Killing Technology (1987) and Queensrÿche’s Operation: Mindcrime (1988).

But the 1980s also saw the emergence of more fantasy-oriented strains, such as black, doom, and death metal, whose rise to dominance coincided with the sudden explosion in popularity of a fantastic genre that had, until that time, largely skulked in the shadow of SF and high fantasy: supernatural horror. Unsurprisingly, the decade saw a convergence of metal music and horror fiction that was akin to the 1970s fusion of rock and SF anatomized in Strange Stars. Here, as elsewhere, Black Sabbath was a pioneer, their self-titled 1970 debut offering a potent brew of pop paganism culled equally from low-budget Hammer films and the occult thrillers of Dennis Wheatley. By the mid-1980s, there were hundreds of bands — from Sweden’s Bathory to England’s Fields of the Nephilim to the pride of Tampa, Florida, Morbid Angel — who were offering similar fare. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos inspired songs by Metallica, Mercyful Fate, and countless other groups — including Necronomicon, a German thrash-metal outfit whose name references a fictional grimoire featured in several of the author’s stories.

By the same token, heavy metal music deeply influenced the burgeoning field of horror fiction. Several major 1980s texts treated this theme overtly: the doom-metal outfit in George R. R. Martin’s The Armageddon Rag (1983) is a twisted emanation of the worst impulses of the 1960s counterculture; the protagonist of Anne Rice’s The Vampire Lestat (1985) is a Gothic rocker whose performances articulate a pop mythology of glamorous undeath; and the mega-cult band in John Skipp and Craig Spector’s splatterpunk classic The Scream (1988) are literal hell-raisers, a Satanic incarnation of the most paranoid fantasies of Christian anti-rock zealots. The heady conjoining of hard rock with supernaturalism percolated down from these best sellers to the more ephemeral tomes that packed the drugstore racks during the decade, an outpouring of gory fodder affectionately surveyed in Grady Hendrix’s award-winning study Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction (2017). Hendrix, himself a horror author of some note, has now published We Sold Our Souls (2018), the quintessential horror-metal novel for our times.

Hendrix has stated that, prior to embarking on this project, he was not “a natural metal fan”:

I was scared of serious metal when I was growing up. Slayer and Metallica intimidated me, and I was too unsophisticated to appreciate the fun of hair metal bands like Mötley Crüe and Twisted Sister, so I basically sucked. […] But I got really deep into metal while writing We Sold Our Souls and kind of fell in love.

The author’s immersion in — and fondness for — the genre is evident on every page of his new novel. Chapters are titled using the names of classic metal albums: “Countdown to Extinction” (Megadeth, 1992), “From Enslavement to Obliteration” (Napalm Death, 1988), “Twilight of the Gods” (Bathory, 1991), and so on. The effect is to summon a hallowed musical canon while at the same time evoking the story’s themes and imparting an emotional urgency to its events. These events also nostalgically echo 1980s rock-horror novels: like The Armageddon Rag, Hendrix’s plot chronicles the reunion of a cult outfit whose breakup decades before was enigmatically fraught; like The Scream, it features a demonic metal band that converts its worshipful fans into feral zombies; like The Vampire Lestat, it culminates in a phantasmagoric stadium concert that erupts into a brutal orgy of violence. Yet despite these pervasive allusions, the novel does not come across as mere pastiche: it has an energy and authenticity that make it feel quite original.

A large part of that originality lies in its protagonist. As the cock-rock genre par excellence, its blistering riffs and screeching solos steeped in adolescent testosterone, heavy metal has had very few notable female performers. But one of them, at least in Hendrix’s fictive history, was Kris Pulaski, lead guitarist of Dürt Würk, a legendary quintet from rural Pennsylvania that abruptly dissolved, under mysterious circumstances, in the late 1990s, just as they were poised for national fame. Kris was a scrappy bundle of nerves and talent, a kick-ass songwriter and a take-no-prisoners performer:

She had been punched in the mouth by a straight-edge vegan, had the toes of her Doc Martens kissed by too many boys to count, and been knocked unconscious after catching a boot beneath the chin from a stage diver who’d managed to do a flip into the crowd off the stage at Wally’s. She’d made the mezzanine bounce like a trampoline at Rumblestiltskins, the kids pogoing so hard flakes of paint rained down like hail.

But that was eons ago. As the story opens, she is staffing the night desk at a Best Western, burned out at 47, living in a broken-down house with her ailing mother and trying to ignore “the background hum of self-loathing that formed the backbeat of her life.” She hasn’t seen her bandmates in decades, since she drunkenly crashed their tour van and almost killed them all, and hasn’t picked up a guitar in almost as long, constrained by the terms of a draconian contract she signed with Dürt Würk’s former lead singer, Terry Hunt, who now controls the band’s backlist. While Kris has lapsed into brooding obscurity, Hunt has gone on to global success, headlining a “nu metal” outfit called Koffin (think Korn or Limp Bizkit) whose mainstream sound Kris despises: “It was all about branding, fan outreach, accessibility, spray-on attitude, moving crowds of white kids smoothly from the pit to your merch booth.” It was the exact opposite of genuine metal, which “tore the happy face off the world. It told the truth.”

To inject a hint of authenticity into Koffin’s rampant commodification, Hunt occasionally covers old Dürt Würk hits. But he avoids like the plague any songs from the band’s long-lost third album, Troglodyte, with their elaborate mythology of surveillance and domination:

[T]here is a hole in the center of the world, and inside that hole is Black Iron Mountain, an underground empire of caverns and lava seas, ruled over by the Blind King who sees everything with the help of his Hundred Handed Eye. At the root of the mountain is the Wheel. Troglodyte was chained to the Wheel along with millions of others, which they turned pointlessly in a circle, watched eternally by the Hundred Handed Eye.

Inspired by the arrival of a butterfly that proves the existence of a world beyond his bleak dungeon, Troglodyte ultimately revolts against Black Iron Mountain, overthrowing the Blind King and leading his fellow slaves into the light.

One might assume that Hunt avoids this album because the scenario it constructs can too readily be perceived as an allegory of liberation from the consumerist shackles of Koffin’s nu-metal pablum. That might be part of the reason, but Hunt’s main motivation is even more insidious: he fears Troglodyte because its eldritch tale is literally true — Koffin is a front for a shadowy supernatural agency that feeds on human souls, and Dürt Würk’s third album holds the key to unmasking and fighting it. This strange reality gradually dawns on Kris, and when Koffin announces plans for a massive series of concerts culminating in a “Hellstock” festival in the Nevada desert, she decides to combat its infernal designs with the only weapon she has: her music. Because “a song isn’t a commercial for an album. It isn’t a tool to build name awareness or reinforce your brand. A song is a bullet that can shatter your chains.”

This bizarre plot, like the concept albums by Mastodon or Iron Maiden it evokes, runs the risk of collapsing into grandiloquent absurdity if not carried off with true conviction. And this is Hendrix’s key achievement in the novel: he never condescends, never winks at the audience or tucks his tongue in cheek. Like the best heavy metal, We Sold Our Souls is scabrous and harrowing, its pop mythology fleshed out with vividly gruesome set pieces, as when Kris surprises the Blind King’s minions at their ghastly repast:

Its fingernails were black and it bent over Scottie, slobbering up the black foam that came boiling out of his mouth. Kris […] saw that the same thing was crouched over Bill, a starved mummy, maggot-white, its skin hanging in loose folds. A skin tag between its legs jutted from a gray pubic bush, bouncing obscenely like an engorged tick. […] Its gaze was old and cold and hungry and its chin dripped black foam like a beard. It sniffed the air and hissed, its bright yellow tongue vibrating, its gums a vivid red.

The irruption of these grisly horrors into an otherwise mundane milieu of strip malls and franchise restaurants and cookie-cutter apartments is handled brilliantly, on a par with the best of classic splatterpunk by the likes of Joe R. Lansdale or David J. Schow.

Hendrix also, like Stephen King, has a shrewd feel for true-to-life relationships, which adds a grounding of humanity to his cabalistic flights. Kris’s attempts to reconnect with her alienated bandmates — such as erstwhile drummer JD, a wannabe Viking berserker who has refashioned his mother’s basement into a “Metalhead Valhalla” — are poignantly handled, and the hesitant bond she develops with a young Koffin fan named Melanie has the convincing ring of post-feminist, intergenerational sisterhood. Throughout the novel, Hendrix tackles gender issues with an intrepid slyness, from Kris’s brawling tomboy efforts to fit into a male-dominated world to Melanie’s frustration with her lazy, lying, patronizing boyfriend, with whom she breaks up in hilarious fashion:

She screamed. She broke his housemate’s bong. She Frisbee-d the Shockwave [game] disc so hard it left a divot in the kitchen wall. She raged out of the house as his housemates came back from brunch.

“Dude,” they said to Greg as he jogged by them, “she is so on the rag.”

“Are we breaking up?” Greg asked, clueless, through her car window.

It took all her self-control not to back over him as she drove off.

Such scenes of believable banality compellingly anchor the novel’s febrile horrors, as do the passages of talk-radio blather interspersed between the chapters, which remind us that conspiratorial lunacy is always only a click of the AM dial away.

While obviously a bit of a throwback, We Sold Our Souls shows that the 1980s milieu of heavy metal and occult horror — of bootleg cassettes and battered paperbacks — continues to have resonance in our age of iPods and cell-phone apps. It also makes clear that the dreamy confluence of rock and the fantastic so ably anatomized in Heller’s Strange Stars is still going strong.

¤

Rob Latham is a LARB senior editor. His most recent book is Science Fiction Criticism: An Anthology of Essential Writings, published by Bloomsbury Press in 2017.

The post Magic Carpet Rides: Rock Music and the Fantastic appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://bit.ly/2SMN28U

0 notes