#contemporary swedish photographer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

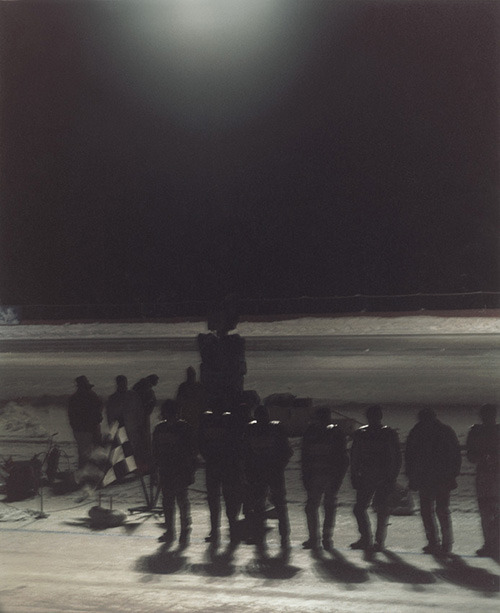

Martina Hoogland Ivanow, From the Speedway series, 2001-2005

#art#artist#contemporary art#contemporary artist#photography#photograph#photographer#swedish artist#woman artist#martina hoogland ivanow#non linear documentation

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

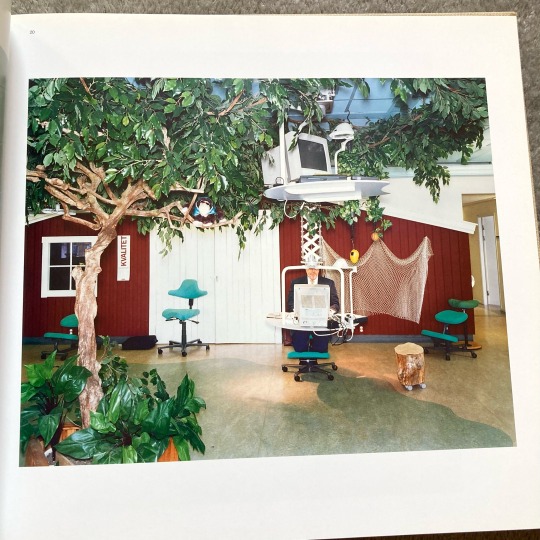

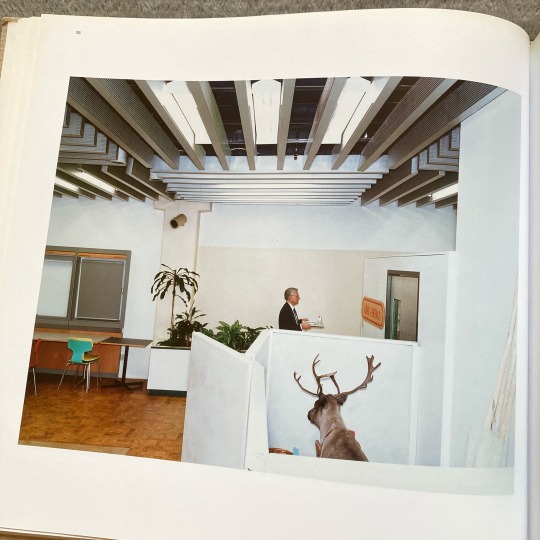

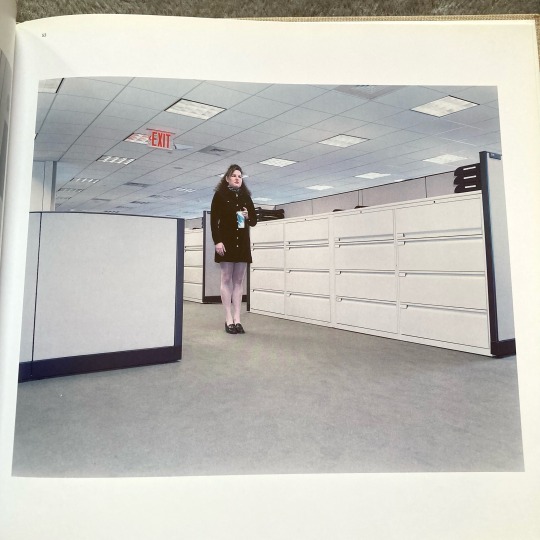

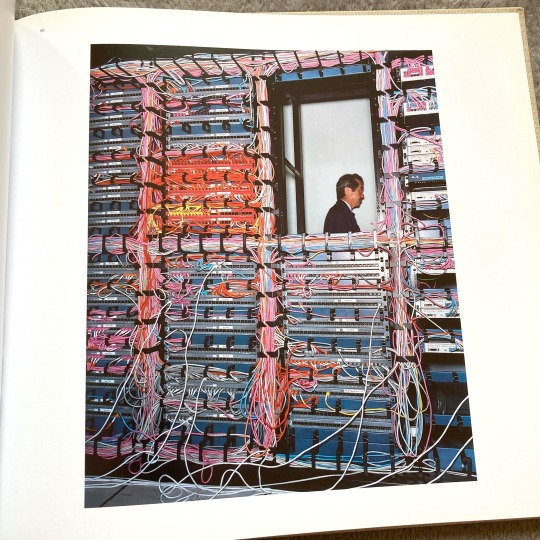

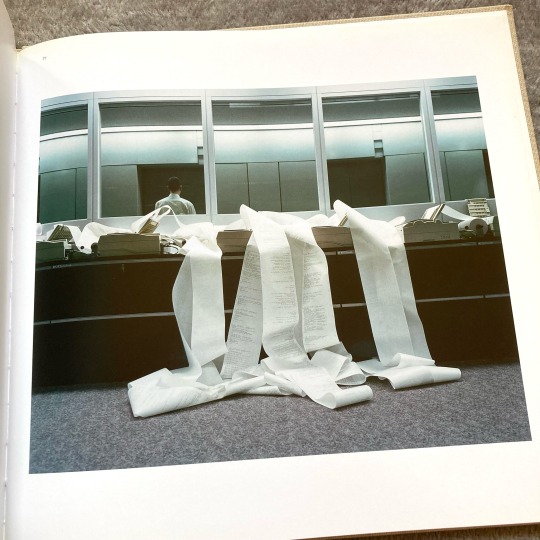

📚 From our personal bookshelf:

Office by Lars Tunbjörk - published by Max Ström, 2002

Please check out our STORE 📚👀

#photobooks#photobookjunkies#photobookjousting#buybooksnotgear#documentary photography#contemporary photography#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#photography books#Lars Tunbjork#swedish photographer#lensblr#liminal spaces#office space#mamiya 7

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tri-Weekly Most Successful YWAMag Selection #108

Carstruck © Matti Merilaid aka Street Matt :

#matti merilaid#street matt#the tri-weekly most successful YWAMag selection#art#artists on tumblr#photographers on tumblr#original photography#contemporary art#masterpieces#visual poetry#yes we are magazine#composition#perfections#cars#masters on tumblr#digital art#emotions#swedish photographers#gifts#magic

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tova Mozard (Swedish, b. 1978), Shins, 2002. Photograph, Inkjet print, 33.7 × 41.6 cm. (Source: Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden)

#photography#modern photography#contemporary photography#photographic arts#Swedish photography#modern Swedish photography#black and white#black and white photography#Swedish photographer#Tova Mozard#Moderna Museet#female visual artist#female photographer

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘100% feminist’: how Eleanor Rathbone invented child benefit – and changed women’s lives for ever

She was an MP and author with a formidable reputation, fighting for the rights of women and refugees, and opposing the appeasement of Hitler. Why isn’t she better known today?

Ladies please reblog to give her the recognition she deserves

By Susanna Rustin Thu 4 Jul 2024

My used copy of the first edition of The Disinherited Family arrives in the post from a secondhand bookseller in Lancashire. A dark blue hardback inscribed with the name of its first owner, Miss M Marshall, and the year of publication, 1924, it cost just £12.99. I am not a collector of old tomes but am thrilled to have this one. It has a case to be considered among the most important feminist economics books ever written.

Its centenary has so far received little, if any, attention. Yet the arguments it sets out are the reason nearly all mothers in the UK receive child benefit from the government. Its author, Eleanor Rathbone, was one of the most influential women in politics in the first half of the 20th century. She led the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (Nusec, the main suffragist organisation, also formerly known as the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies) from 1919, when Millicent Fawcett stood down, until the roughly five million women who were not enfranchised in 1918 gained the vote 10 years later. In 1929, aged 57, she became an MP, and remained in parliament until her death in 1946. While there, she built up a formidable reputation based on her advocacy for women’s rights, welfare reform and the rights of refugees, and her opposition to the appeasement of Hitler.

It would not be true to say that Eleanor Rathbone has been forgotten. Her portrait by James Gunn hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Twenty years ago she was the subject of a fine biography and she is remembered at Somerville college, Oxford – where she studied in the 1890s and ran a society called the Associated Prigs. (While the name was a joke, Rathbone did have a priggish side – as well as being an original thinker, tremendous campaigner, and stubborn, sensitive personality.) She also features in Rachel Reeves’s book The Women Who Made Modern Economics, although Reeves – who hopes shortly to become the UK’s first female chancellor – pays more attention to her contemporary, Beatrice Webb.

A thrilling tome … The Disinherited Family by Eleanor Rathbone. Photograph: Alicia Canter/The Guardian

But Rathbone, who came from a wealthy dynasty of nonconformist merchants, does not have anything like the name-recognition of the Pankhursts or Millicent Fawcett, or of pioneering politicians including Nancy Astor and Ellen Wilkinson. Nor does she enjoy the cachet of writers such as Virginia Woolf, whose polemic about women’s opportunities, A Room of One’s Own, was published five years after Rathbone’s magnum opus.

There are many reasons for Rathbone’s relative obscurity. One is that she was the first woman elected to parliament as an independent (and one of a handful of men at the time). Thus there is no political party with an interest in turning her into an icon. Having spent the past three years writing a book about the British women’s movement, I am embarrassed to admit that when I started, I didn’t know who she was.

Rathbone was not the first person to propose state benefits paid to mothers. The endowment of motherhood or family allowances, as the policy was known, was written about by the Swedish feminist Ellen Key, and tried out as a project of the Fabian Women’s Group, who published their findings in a pamphlet in 1912. But Rathbone pushed the idea to the forefront. A first attempt to get Nusec to adopt it was knocked back in 1921, and she then spent three years conducting research. The title she gave the book she produced, The Disinherited Family, reflected her view that women and children were being deprived of their rightful share of the country’s wealth.

The problem, as she saw it, was one of distribution. While the wage system in industrialised countries treated all workers on a given pay grade the same, some households needed more money than others. While unions argued for higher wages across the board, Rathbone believed the state should supplement the incomes of larger families. She opened the book with an archly phrased rhetorical question: “Whether there is any subject in the world of equal importance that has received so little consideration as the economic status of the family?” She went on to accuse economists of behaving as if they were “self-propagating bachelors” – so little did the lives of mothers appear to interest them.

Rathbone’s twin aims were to end wives’ dependence on husbands and reward their domestic labour. Family allowances paid directly to them could either be spent on housekeeping or childcare, enabling them to go out to work. Ellen Wilkinson, the radical Labour MP for Middlesbrough (and future minister for education), was among early supporters. William Beveridge read the book when he was director of the London School of Economics, declared himself a convert and introduced one of the first schemes of family-linked payments for his staff.

But others were strongly opposed. Conservative objections to such a radical expansion of the state were predictable. But they were echoed by liberal feminists including Millicent Fawcett, who called the plan “a step in the direction of practical socialism”. Trade unions preferred to push for a living wage, while some male MPs thought the policy undermined the role of men as breadwinners. Labour and the Trades Union Congress (TUC) finally swung behind family allowances in 1942. As the war drew to a close, Rathbone led a backbench rebellion against ministers who wanted to pay the benefit to fathers instead.

Rathbone celebrates the Silver Jubilee of the Women’s Vote in London, 20 February 1943. Photograph: Picture Post/Getty Images

It is for this signature policy that she is most often remembered today. At a time when hundreds of thousands of children have been pushed into poverty by the two-child limit on benefit payments, Rathbone’s advocacy on behalf of larger families could hardly be more relevant. The limit, devised by George Osborne, applies to universal and child tax credits – and not child benefit itself. But Rishi Sunak’s government announced changes to the latter in this year’s budget. From 2026, eligibility will be assessed on a household rather than individual basis. This is intended to limit payments to better-off, dual-income families. But the UK Women’s Budget Group and others have objected on grounds that child benefit should retain its original purpose of directly remunerating primary carers (the vast majority of them mothers) for the work of rearing children. It remains to be seen whether this plan will be carried through by the next government.

Rathbone once told the House of Commons she was “100% feminist”, and few MPs have been as single-minded in their commitment to women’s causes. As president of Nusec (the law-abiding wing of the suffrage campaign), she played a vital role in finishing the job of winning votes for women.

The last few years have seen a resurgence of interest in women’s suffrage, partly due to the centenary of the first women’s suffrage act. Thanks to a brilliant campaign by Caroline Criado Perez, a statue of Millicent Fawcett, the nonmilitant suffragist leader, now stands in Westminster, a few minutes walk from the bronze memorial of Emmeline Pankhurst erected in 1930. Suffragette direct action has long been a source of fascination. What is less well known is that militants played little part in the movement after 1918. It was law-abiding constitutionalists – suffragists rather than suffragettes – who pushed through the 1920s to win votes for the younger and poorer women who did not yet have them. Rathbone helped lead this final phase of the campaign, along with Conservative MP Nancy Astor and others.

Rathbone was highly critical of the militants, and once claimed that they “came within an inch of wrecking the suffrage movement, perhaps for a generation”. Today, with climate groups including Just Stop Oil copying the suffragette tactic of vandalising paintings, it is worth remembering that many women’s suffrage campaigners opposed such methods.

Schismatic though it was, the suffrage movement at least had a shared goal. An even greater challenge for feminists in the 1920s was agreeing on future priorities. Equal pay, parental rights and an end to the sexual double standard were among demands that had broad support. After the arrival in the House of Commons of the first female MPs, legislative successes included the removal of the bar on women’s entry to the professions, new rights for mothers and widows’ pensions. But there were also fierce disagreements.

Tensions between class and sexual politics were longstanding, with some on the left regarding feminism as a distraction. The Labour MP Marion Phillips, for example, thought membership of single-sex groups placed women “in danger of getting their political opinions muddled”. There was also renewed conflict over protective legislation – the name given to employment laws that differentiated between men and women. While such measures included maternity leave and safety rules for pregnant women, many feminists believed their true purpose was to keep jobs for men – and prevent female workers from competing.

Underlying such arguments was the question of whether women, once enfranchised, should strive for equal treatment, or push for measures designed to address their specific needs. As the debate grew more heated, partisans on either side gave themselves the labels of “old” and “new” feminists. While the former, also called equalitarians, wanted to focus on the obstacles that prevented women from participating in public life on the same terms as men, the new feminists led by Rathbone sought to pioneer an innovative, woman-centred politics. Since this brought to the fore issues such as reproductive health and mothers’ poverty, it is known as “maternalist feminism”.

Rathbone and other Liverpool suffragettes campaigning in 1910. Photograph: Shawshots/Alamy

The faultline extended beyond Britain. But Rathbone and her foes had some of the angriest clashes. At one international convention, Lady Rhondda, a wealthy former suffragette, used a speech to deride rivals who chose to “putter away” at welfare work, instead of the issues she considered important.

The specific policy points at issue have, of course, changed over the past century. But arguments about how much emphasis feminists should place on biological differences between men and women carry on.

Eleanor Rathbone did not live long enough to see the welfare state, including child benefit paid to mothers, take root in postwar Britain. Her election to parliament coincided with the Depression, and the lengthening shadows of fascism and nazism meant that she, like her colleagues, became preoccupied with foreign affairs. In the general election of 1935, the number of female MPs fell from 15 to nine, meaning Rathbone’s was one of just a handful of women’s voices. She used hers to oppose the policy of appeasement, and support the rights of refugees, including those escaping Franco’s Spain. During the war she helped run an extra-parliamentary “woman-power committee”, which advocated for female workers.

She also became a supporter of Indian women’s rights, though her liberal imperialism led to tensions with Indian feminists. During the war she angered India’s most eminent writer, Rabindranath Tagore, and its future prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, when she attacked the Congress party’s policy of noncooperation with Britain’s war effort. Tagore criticised what he called the “sheer insolent self-complacency” of her demand that the anti-colonial struggle should be set aside while Britain fought Germany.

Rathbone turned down a damehood. After their first shared house in Westminster was bombed, she and her life partner, the Scottish social worker Elizabeth Macadam, moved around the corner to a flat on Tufton Street (Macadam destroyed their letters, meaning that Rathbone’s intimate life remains obscure, but historians believe the relationship was platonic). From there they moved to a larger, quieter house in Highgate. On 2 January 1946, Rathbone suddenly died.

Rathbone’s blue plaque at Tufton Court. Photograph: PjrPlaques/Alamy

A blue plaque on Tufton Street commemorates her as the “pioneer of family allowances” – providing an alternative claim on posterity for an address more commonly associated with the Brexit campaign, since a house a few doors down became its headquarters. She is remembered, too, in Liverpool, where her experience of dispersing welfare to desperately poor soldiers’ wives in the first world war changed the course of her life, and where one of her former homes is being restored by the university.

I don’t believe in ghosts. But walking in Westminster recently, I imagined her hastening across St James’s Park to one of her meetings at Nancy Astor’s house near the London Library. Today, suffragettes are celebrated for their innovative direct action. But Rathbone blazed a trail, too, with her dedication as a campaigner, writer, lobbyist and “100% feminist” parliamentarian.

Sexed: A History of British Feminism by Susanna Rustin is published by Polity Press (£20). To support the Guardian order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

#Eleanor Rathbone#The Disinherited Family#Books by women#Books about women#Child benefit#National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (Nusec)#Rachel Reeve#The Women Who Made Modern Economics#Women in politics#UK#Seed: A History of British Feminism#Susan Rustin

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

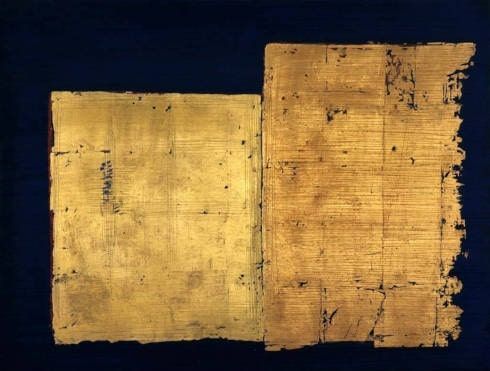

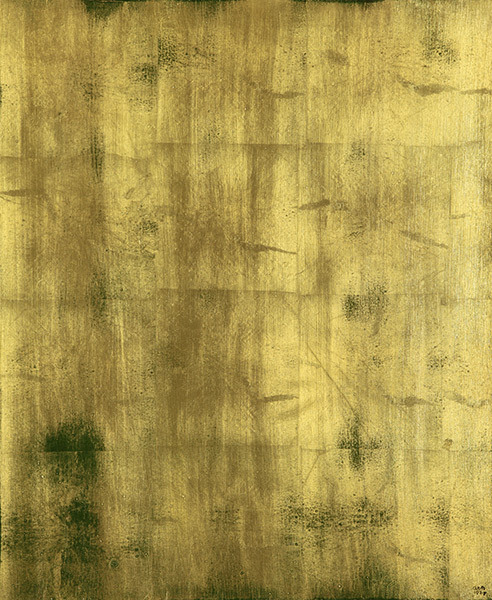

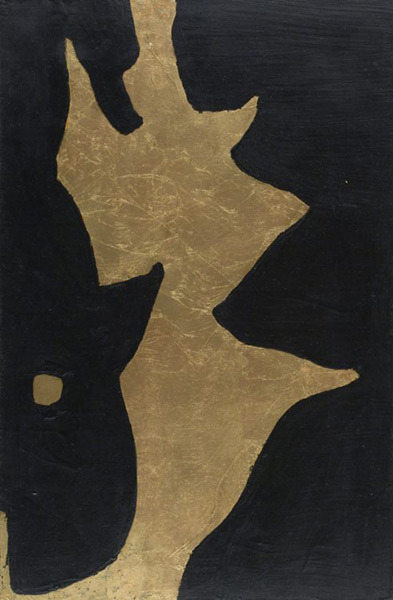

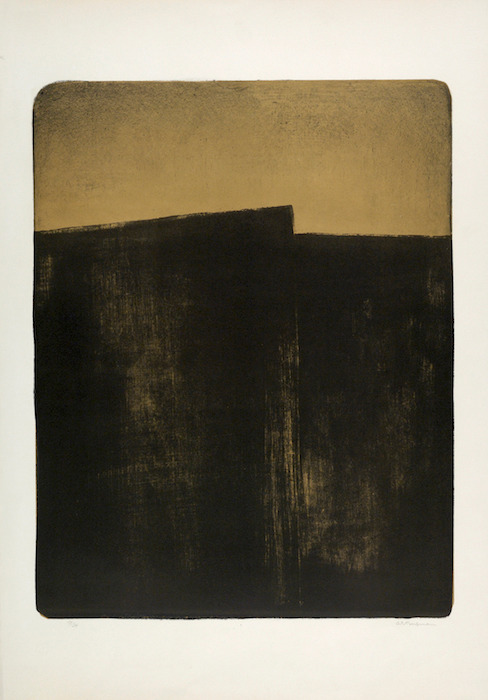

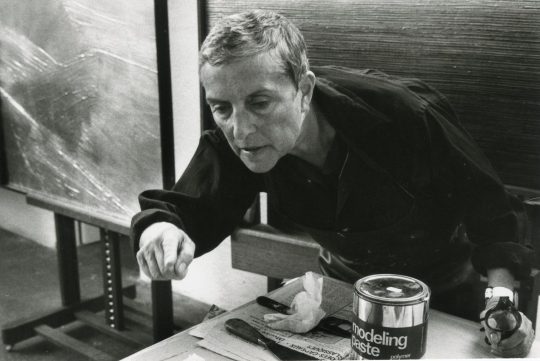

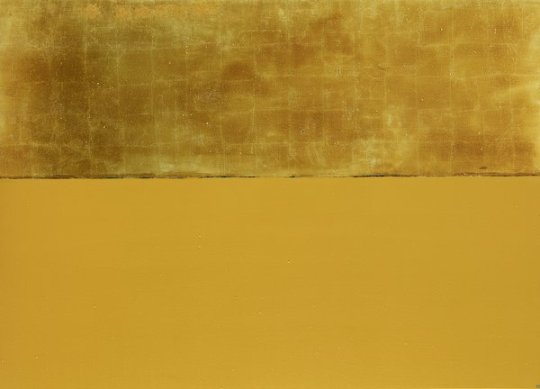

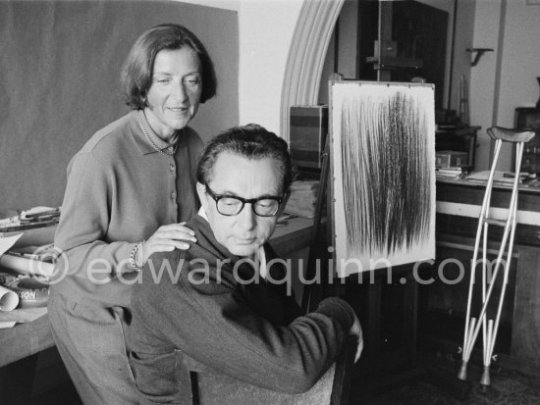

Anna-Eva Bergman (1909, Sweden - 1987 France)

Anna-Eva Bergman was born in Stockholm on May 29, 1909 to a Norwegian mother and a Swedish father. Her parents separated six months after she was born and her mother brought her to Norway where she later studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Oslo (1927) and at the School of Applied Arts in Vienna (1928).

Bergman's writings and drawings show her sense of humor and observation, and demonstrate a virtuosic talent for drawing. Later, she would prove herself as an illustrator and journalist.In April 1929 she moved to Paris and enrolled at the André Lhote Academy where she met Hans Hartung. They got married the same year in Dresden.

From 1933 to 1934, the couple lived on the island of Menorca in the Balearic Islands. The paintings and watercolors of this period show Bergman's interest in the golden ratio and architecture, and foreshadow the simple, constructed forms of her future work.After divorcing Hartung in 1938, Bergman returned to Norway where, up to 1945, she devoted herself mainly to illustration and writing. In 1946, she committed wholeheartedly to painting again and since then she began to paint with a non-figurative approach. Line and rhythm became fundamental. This period marks a major turning point in her artistic creation: she was inventing and building a singular universe little by little. She produced her first painting in gold leaf and definitively abandoned illustration.

During the summer of 1950, Bergman took a boat trip along the Norwegian coast, visiting the Lofoten Islands and Finnmark. This trip was decisive in the evolution of her painting. With the tempera technique, she rediscovered the transparency of the landscapes and the light of the midnight sun. In 1951, following several summers spent in Citadelløya (southern Norway), Bergman produced paintings and drawings depicting the structure of rocks worn by the sea. From this series, which she called Fragments of an Island in Norway, came her first motif: stone (1952). This is a major transition in her work. Her painting then evolved towards the search for a limited number of simple motifs.In 1952, Bergman moved to Paris and found Hans Hartung again.

They remarried in 1957.In 1958, in a series of works on paper of the same format, in tempera and metal leaf, Bergman used for the first time in painting the repertoire of forms that she had developed in her work since 1952: stone, moon, star, planet, mountain, stele, tree, tomb, valley, ship, prow and mirror. These archetypal forms inspired by Scandinavian nature and the powerful Nordic light would become the central elements of Bergman's work.In 1964, Bergman and Hartung traveled by boat along the Norwegian coast, past the North Cape. For several years, Bergman would use the sketches and photographs from this trip to in her work.The couple moved to Antibes in 1973 where together they designed their house and studios which later became the Hartung-Bergman Foundation.

Bergman's work evolved towards increasingly simpler forms and a restricted color palette. She abandoned the construction of her paintings based on the golden ratio and added two themes to her vocabulary of forms: waves and rain.Anna-Eva Bergman died on Friday, July 24, 1987 at the hospital in Grasse.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, I looked this up because holy fucking shit what, and it turns out this is almost certainly 100% apocryphal.

“Some sources state that in 17th-century Sweden Charles XI trialled the use of moose as a replacement for horses, which had to be imported, but this is disputed.” It is, however, apparently true that they drew the sleighs of royal couriers for a while, which is goddamned fabulous.

“Some sources state that as a development of this role Charles XI (1660–1697) trialled the use of moose cavalry,” with the idea they would cause fear on the battlefield (which, super true!), but “It is said that during training the moose was too fearful to allow itself to be ridden into battle and took fright at the sound of gunfire.[6] They were also said to be of too peaceful in nature for the purpose.[1] Moose were also more susceptible to disease than horses and there was difficulty in feeding the animals which were used to foraging across large areas rather than being fed on fodder in pasture.”

Which all seems reasonable. However, “Swedish historian Dick Harrison has stated that he has found no evidence for the trial or use of moose cavalry in contemporary sources and that it is most likely a myth.”

For the Russian thing, “Some news outlets have reported that Joseph Stalin attempted to introduce the moose as a replacement for horses in Soviet cavalry regiments based in the northern parts of the country during the 1930s.[5][8] The story is thought to have been popularised by a 2010 April Fools' Day article published in the Russian language edition of Popular Mechanics. […] The article claimed that 1,500 moose cavalrymen were trained for service in the Winter War of 1939 and 1940.[10] Machine guns were supposedly mounted to the antlers of the moose.”

Which… one begins to see how this was a clear parody.

But “The hoax article was widely reproduced in Russian media over the following years, often without the April Fools' Day disclaimer carried in the original article.” So as usual the culprit is lack of sourcing and proper attribution. And then it gets worse! “In 2017, a war museum in Lakhdenpokhya, Karelia, Russia showcased the doctored photographs from the Popular Mechanics article in an exhibition as a recent discovery of historic documents. The exhibition claimed that the "war moose" had been trained by the Soviet army for four years.”

There are some sources predating the Popular Mechanics article that say Stalin trialed the use of moose as cavalry, however, “The National Archives of Finland state that the Red Army did use limited numbers of moose during the Second World War, though as pack or draft animals, not as mounts.”

All of that said… holy shit wouldn’t it have been amazing if it really could’ve been done. Amazing and TERRIFYING.

Every time I see fantasy ideas where people ride deer or dogs or wolves or what-have-you 90% of my brain goes 'oh that's COOL', because it IS and I LOVE IT, but the other 10% that's annoying and a nerd is like. there is a reason we domesticated horses specifically for riding instead of any other animal!! If u look at the motion of the topline and legs, u may notice one of these is not like the others......

.......and also significantly less likely to launch you into space by changing the shape of its spine under your butt a billion times per minute

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

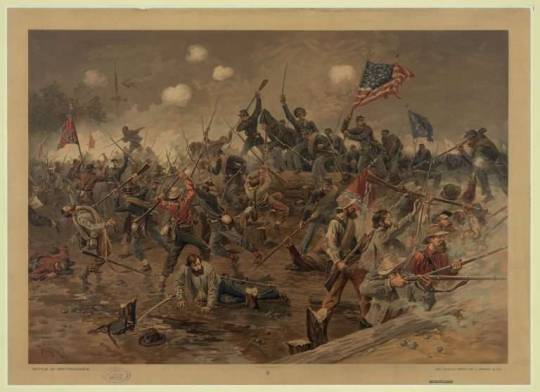

Crowd Scenes . 04 November 2024 . Battle of Spotsylvania Court House . Thure de Thulstrup 1887

Credit: Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division Original Author: Thure de Thulstrup, artist; L. Prang & Co., publisher Created: 1887 Medium: Chromolithograph Publisher: Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

An 1887 chromolithograph by well-known contemporary illustrator Thure de Thulstrup depicts a bayonet charge by Union forces during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. That bloody battle took place in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, over the course of nearly two weeks in May 1864, and resulted in more than 18,000 dead, wounded, captured, or missing Union soldiers, and more than 12,000 casualties on the Confederate side. During the fighting, a young West Point–educated Union colonel named Emory Upton concluded that attacking the Confederates' well-constructed earth-and-log works required a new mode of attack. Rather than advancing in long lines of infantry that halted in the open in order to exchange fire with a well-protected enemy behind earthworks, Upton argued for storming columns that never stopped to open fire, but instead advanced right up to the earthworks, engaging the enemy with the bayonet. He tested his new tactics as part of an all-out attack on the evening of May 10; its initial success impressed the Union commander Ulysses S. Grant, who duplicated the maneuver on a larger scale.

Thulstrip was a Swedish-born artist and magazine illustrator who specialized in military scenes. The print was published by L. Prang and Company in Boston, Massachusetts, a firm known for producing scenes from the Civil War, and for pioneering the sale of Christmas cards in the United States. The owner of the company, Louis Prang—a native of Prussia who emigrated to Boston in 1850–-has been referred to as the "father of the American Christmas card."

0 notes

Text

The mysterious New York nanny who helped shape 20th-century street photography

For much of her life, Vivian Maier was something of a mystery. Her photographic talent went largely unrecognized because she kept her work a secret from most of the people who knew her, including the New York and Chicago families she worked for as a live-in nanny and caregiver. Maier only printed a tiny fraction of the hundreds of thousands of images of bustling city life she snapped with her Rolleiflex and Leica cameras over some five decades, and showed them to almost no one, instead amassing boxes and boxes of negatives and unprocessed film.

Her fame came about posthumously, and only because the contents of her Chicago storge lockers were sold off at auction in 2007, after she had stopped paying the rent.

“Vivian Maier the mystery, the discovery, and the work — those three parts together are difficult to separate,” said Anne Morin, curator of the touring exhibition “Vivian Maier: Unseen Work,” which opened 31 May at Fotografiska New York, the American outpost of the Swedish contemporary photography museum.

The show, which runs through 29 September, does not attempt to unravel the puzzle of Maier’s life, however, instead focusing on the work itself, with more than 200 photographs on display, including about 50 vintage prints made by Maier. Morin places her work on the same level as that of renowned street photographers like Robert Frank and Diane Arbus, and worthy of a place in the history of photography. “Nobody doubts that,” Morin told CNN. “The work is strong and Maier had a marvelous eye. And in 10 years, we could do another completely different show — she has more than enough material to bring to the table.”

The exhibition is also a homecoming of sorts for Maier, who was born in New York to a family of French and German immigrants. She started capturing street scenes in the city as a young woman in the 1950s, first borrowing her mother’s Kodak Brownie box camera and then buying her own professional-grade Rollieflex, which she taught herself to use. Her confidence and skill in finding the right moment to snap the shutter is evident even in these early works, in which Maier zeroed in on the unique characters and situations that make up city life: Men snoring open-mouthed on park benches; a balloon from the Central Park Zoo floating to hide a doting father’s face as his baby reaches towards him.

But while Maier was known to use commercial studios in New York to have her film processed, she never seems to have made a serious effort to exhibit or sell her work. Maier’s return to New York as a popular icon is “a big thing not only for women, but also for all the artists who are working and are never recognized and never have the opportunity to be seen, to be shared, to exist,” Morin said. “It is never late to repair history.”

New York is “in many ways, the heart of photography history in America,” said Sophie Wright, the museum’s director. “So it’s amazing now to be in a position to be bringing Vivian back to that world. She’s a rediscovered, important voice of 20th-century photography.” Wright added that Maier’s photographs were taken with “so much thought and care and lack of self-consciousness — there’s no audience in mind. In a way, it’s pure, artistic expression for her.”

Maier’s name and work first captured the public imagination in 2009, the same year she died in Chicago, after the collector and amateur historian John Maloof shared scans of her work on the photo-sharing website Flickr. He was seeking advice on what to do with the thousands of negatives, prints and undeveloped rolls of film he had acquired over the past two years, after stumbling across Maier’s work at the auctions of her storage lockers.

Photographers and critics immediately remarked on Maier’s well balanced compositions, and her incisive and often humorous view of the people and places she came across, not just in New York, but also Chicago, where she moved in 1956 and spent most of her adult life, as well as the far flung locations she visited on vacations, from California to Europe and Asia. In 2011, Maloof published a book, “Vivian Maier: Street Photographer,” and with the filmmaker Charlie Siskel co-directed the 2013 documentary “Finding Vivian Maier,” which was nominated for an Academy Award.

A number of other gallery shows and biographies have also debuted in the years since— as well as a legal tussle over Maier’s estate, which is now overseen by Chicago’s Cook County Probate Court, and with which Maloof has signed an agreement to display and sell her work. (While Maier did not have any children of her own to inherit her estate, 10 potential heirs in Europe have been found among her extended family, and the court is looking into whether her brother Carl, who died in a psychiatric hospital in 1977, might have had any children.) The public’s appetite for Maier hasn’t diminished, however. When the current exhibition was on display at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris in 2021, amid the Covid-19 pandemic, more than 213,000 people attended over its four-month run. The opening preview in New York on 30 May had over 600 visitors.

Despite her immense popularity, some museums have been slow to accept her work, even those that have major photography collections. Wright attributes this caution over Maier’s work to the fact that she did not make many prints herself. “There’s a reticence to be seen to be driving a narrative for the work that’s not the artist’s,” she explained, as well as a nervousness around the politics of her situation as a woman who was vulnerable in her later years. (At the end of her life, as her hoarding led to her losing caretaking jobs, Maier was believed to have been facing homelessness, until two of her former charges, Lane and Matthew Gensburg, paid for an apartment for her to live in, and later a nursing home.)

Maloof and the photography dealer Howard Greenberg, who represents his extensive collection, acknowledge the concerns around posthumous printing of Maier’s work, and during a talk at the exhibition opening, said that led to their decision to only create uncropped, direct reproductions from her negatives. In the show, there are many instances where these later prints are displayed next to the ones Maier made herself, showing how she chose to focus on certain elements in a scene.

Maier’s presence can also be felt in the exhibition through audio recordings she made interviewing the children she cared for to encourage their critical thinking, which were also found in her storage lockers. They are played throughout the galleries. But the most persistent reminders of the artist behind these works are the numerous self-portraits she took, often as reflections in mirrored and glass surfaces, or simply as her shadow cast on the ground or a wall.

“The beating heart of the work is the self-representation,” Morin said, and it is these works she sees resonating the most with today’s audiences. “Everybody says, ‘Oh, my God, Vivian was the godmother of the selfie.’ But it’s different,” the curator continued. Maier’s self-portraits are a stubborn insistence in declaring her independence and identity, at a time when women, and especially domestic workers like her, were ignored and marginalized. “She wanted to record that,” Morin said, imagining Maier as saying: “I’m here at this moment. No one will erase my face. I exist and I have the proof.”

~ Helen Stoilas · June 24, 2024.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Michael B. Jordan Strips Down for Calvin Klein "The List" is PAPER's monthly roundup of the newest arrivals, capsules and collaborations. Scroll through, below, to see February's biggest fashion news.Michael B. Jordan Lands First Calvin Klein CampaignMichael B. Jordan strips down for his first-ever Calvin Klein campaign, photographed by Mert and Marcus, where he models a range of their new underwear styles. The images will be displayed on the brand's signature Houston St. and La Cienega billboards in SoHo starting today February 27.Maison Margiela x Gentle MonsterMaison Margiela x Gentle MonsterMaison Margiela x Gentle MonsterMaison Margiela x Gentle MonsterMaison Margiela x Gentle Monster have partnered to launch a new eyewear collection featuring eleven designs in sunglasses and optical frames that incorporate genuine threaded details of Maison Margiela’s signature stitch logo. Prices range from: $320-$680.Available starting February 28 at Gentle Monster and Maison Margiela on/offline storesGivenchy Voyou BagGivenchy Voyou BagGivenchy Voyou BagGivenchy Voyou BagGivenchy Voyou BagFirst seen on the Givenchy runway in Paris last September, the Voyou bag is a new style from the brand under Matthew M. Williams. "I wanted to revisit fashion archetypes with a kind of new language and a playful attitude," he says. "With the Voyou, you know at a glance that it's Parisian, but it's at home wherever it goes, and it makes an everyday style statement that has true staying power." It also features prominently in Givenchy's Spring campaign featuring Gigi Hadid.Available now at Givenchy stores and Givenchy.comDsquared2 Buddy by MySecretCaseDsquared2 is getting into sex toys with the launch of a new collab with MySecretCase. The USB-chargable collection consists of a clitoral sucker, dildo and a penis ring made in a soft skin-safe waterproof silicone all featuring the Dsquared2 logo.Available now at Dsquared2.comCDLP Adds Jockstraps to Core CollectionCDLP Adds Jockstraps to Core CollectionCDLP Adds Jockstraps to Core CollectionFans of Swedish label CDLP's tonal, minimalist underwear can now enjoy the same luxe experience with jockstraps. The brand, which launched the category briefly 2018 and 2020 in limited-edition styles, is officially reintroducing jockstraps to their core collection. The super soft silk-like fabric is lyocell, and the waistband is tonal black with signature CDLP debossed logo.Available now at CDLP.comCOS x YEBOAH COS and emerging designer Reece Yeboah join forces to launch his namesake brand YEBOAH with a new collaboration. The collection developed with COS combines street-luxe wear with contemporary tailoring codes.Available now at CosStores.comRimowa x PalaceRimowa x PalaceRimowa x PalaceRimowa teamed up with London-based skateboarding and clothing brand Palace to create a limited-edition suitcase and a deck and sticker set that merge Rimowa's engineering heritage and Palace's approach to fashion and streetwear.Available starting February 10 the at Rimowa stores worldwide and rimowa.com https://www.papermag.com/february-2023-fashion-news-calvin-klein-2656537230.html

0 notes

Text

Helene Schmitz, contemporary Swedish photographer ♀️

#women artists#women's art#women history month#womenhistorymonth#female photographer#helene schmitz#contemporary photographer#contemporary swedish photographer#swedish photographer#swedish artist

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martina Hoogland Ivanow, From the Speedway series, 2001-2005

#art#artist#contemporary art#contemporary artist#photography#photograph#photographer#swedish artist#Martina hoogland ivanow#woman artist#non linear documentation

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ewa-Marie Rundquist (Swedish, born 1958), Still life, N/D

#photography#still life#still-life#poppies#papaver#ewa-marie rundquist#rundquist#ewamarierundquist#swedish photographer#contemporary photography#vallmo#ewa marie rundquist

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Side Look of a Barcelonese #2 022 : Ceiling. © Matti Merilaid aka Street Matt :

The Side Look of a Barcelonese #2 022 : Ceiling. © Matti Merilaid aka Street Matt :

#matti merilaid#street matt#the side look of a barcelonese#choice of the day of YWAMag#choice of the day of the mag#art#perfections#swedish photographers#gifts#masters on tumblr#magic#contemporary art#yes we are magazine#b and w#masterpieces#composition#architecture#original content#artists on tumblr#photographers on tumblr#original photography#abstract#reflections#compo science#hypnotic images

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Inka & Niclas

Becoming Wilderness II, (2012) 2017

Archival Pigment Print

Courtesy of the artists and Nordic Stories Contemporary Art

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862 – 1944) was a true pioneer in abstract art, though her work was almost never seen outside her close circle during her lifetime. In her will, af Klint wrote that her works were not to be shown until twenty years after her death. She was convinced that her contemporaries were not ready to understand their meaning.

af Klint’s abstract paintings predate the first abstract works by Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich, male artists who are still regarded as the forerunners of twentieth-century abstract art.

af Klint’s powerful, groundbreaking, and striking oeuvre challenges the history of art as previously written. March is Women’s History Month, and quite fittingly, we’re kicking off with Hilma af Klint!

Image 1: Page spread: Left: Automatic drawing resembling handwritten note or scribble. Right: Black and white photograph of Hilma af Klint sitting on a chair.

Image 2: The Large Figure Paintings, No. 5, Group III, The Key to All Works to Date, The WU/Rose Series, 1907

Image 3: Cat. 163. No 4, Series V, 1920.

Hilma af Klint : a pioneer of abstraction Edited by Iris Müller-Westermann, with Jo Widoff ; with contributions by David Lomas, Iris Müller-Westermann, Pascal Rousseau, Helmut Zander. Ostfildern : Hatje Cantz, [2013] 295 pages : illustrations (chiefly color) ; 28 cm. Moderna Museet exhibition catalogue ; no. 375, 0347-9196 English Klint, Hilma af, 1862-1944 [2013] HOLLIS number: 990139574170203941

#Womenshistorymonth#HilmaafKlint#Womenartist#Swedishartist#Abstractart#Abstraction#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#fineartslibrary#harvard#harvard library#harvardfineartslib#harvardlibrary#painting

261 notes

·

View notes