#conjugium

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Some serious considerations on marriage. Wherein (by way of caution and advice to a friend) its nature, ends, events, concomitant accidents, &c. are examined. Conjugium Conjurgium

Seymar, William. (William Seymar is a pseudonymous anagram for William Ramsey.) Cf. Halkett and Laing Conjugium conjurgium: or, some serious considerations on marriage. Wherein (by way of caution and advice to a friend) its nature, ends, events, concomitant accidents, &c. are examined. By William Seymar Esquire. London: printed for John Amery at the Peacock over against St. Dunstan’s Church in…

View On WordPress

#Conjugium conjurgium#Early Conduct Book#Early modern advice book#early printed books#English marriage customs#Sex relations

0 notes

Text

Reply to @hammondegg

She really didn’t want to trust this guy... but he knew Acetylene. Hell, he might know him better than anybody.

“I just...” She clenches her fists. “Lamp is such a horrid man! Treating me like a pawn in his sick game! I hate it!”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Couple of Hearts (Conjugium Corda), Silviya R

‘Couple of Hearts’ 56x38cm acrylic, watercolours, pen ink, 24ct gold leaf on 300GSM Bockingford paper The heart shares with the lotus flower and the rose the qualities of the hidden, enfolded center beneath the outer surface of things, the secret locked away; when we want to 'let someone in', we must give them 'the key'. *Conjugium - from latin: marriage, husband/wife; couple; pair; close connection

https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Painting-Couple-of-Hearts-Conjugium-Corda/126627/2902999/view

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beneficed conjugium for my mailorder friends, mailorder conjugium for my beneficed friends!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

@acetyleneactor

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of the Alchemic of the Sabbath

Within the context of Traditional Witchcraft, the corpors of sorcery we term ‘Sabbatic Craft’ arises from varied occult teachings, ritually transmitted from initiator to initiate, whose shared elements originate in the Sabbath of the Witches. An historical feature of the Traditional Witchcraft lodges which gave rise to Sabbatic Craft is the presence and magical legacy of cunning-folk. Ever resourceful, this stratum of folk-magicians collected a variety of occult charms as the needs of enchantment dictated. In many streams of magic feeding the traditions of Sabbatic Witchcraft, Alchemy, herbalism, and apothecary were realms of magical study practiced by initiates, as were the degraded remnants of ancient religion wherein the Spirit-Cup occupied potent strands of power. However, despite the presence of these ancillary disciplines within the covine, the philtre, over time, has almost exclusively been the preserve of the Witch or sorcerer, rather than the esteemed doctor, alchemist or apothecary.

As such, the Philtre is the Fluid Emanant of the Sabbath, the Wine expressed from the Blasphemous Conjugium of Midnight: a suspect poison to some, and yet a nectar of illumination to others. The Cauldron, as the earthly Temple of the Lady, commands the heart of this Circle, for it is She who governs the Array of Vessels, their manifold powers, and their manipulation via Art to bring forth strange wines. The infernal flame of the Deval Tubalo-Cain, in fiery expression and in absence, serves the Mistress in the capacity of directed Ignis to her Aqua. Their combined seed in the Grand Operation of Art yields the encharmed waters of the Potion. This power is also expressed alchemically as the Conjunction of Sun and Moon, these same two Lamps of Heaven held in high veneration by the witch.

Thus it is that Witch and Alchemist, despite differences of magical expression, patron spirits, and professed goals of their work, share the common aim of Transmutation. To the Alchemist, this power is a gift of God, encrypted in the Tabula Natura, and poured out in blessing upon righteous men who devote their lives and fortunes to the work of the Laboratory. To them who go forth by night in the Companie of the Good, the Art of Transmutation is a needful component of sorcery; its practice encompasses the alchemical rubric, but extends beyond the Laboratory to the Heart of the Sabbath itself. Transmutation lies at the heart of Sabbatic Witchcraft praxes, and is both the Nascent Desire and the Manifest Proof of the Work.

Transmutation effects a desired change from one thing into another such that the New Flesh stands as a light unto the shadow of its former self, transformed in virtue. It is the heart of our Work of the Vessel: not limited to the fluids of the Potion, it extends to all waters, be they elements or principia, and their manifest zones of temporality. In common with chrysopoesis, Our Transmutation seeks a perfected state from a foundational matter deemed imperfect, through a series of focused actions with the aid of spirit-intercession. The Witches’ Transmutation occurs via the Cauldron of the Sabbath, the Artificer’s Fire, the Lightning-bolt, the Night Flight, the Magic Circle, Round-Dance, the Feast of Midnight, and the Sabbath-Wine. Each of these mysteries radiates the power in uniquity within Our Circle, and each has specific bearing upon the potion. Via the roads of Transmutation we call forth the World not as we wish it to be, but as it already is, albeit it distant in space and time: for by all-possibility are all things manifest. Thus Transmutation, in part, seeks to harness the unmanifest, and draw it ever toward the present flesh. When, by power of Art, we bring forth the Work in bodies of flesh, the strictures of Will, Desire, and Belief serve as our Trine. And yet, before our parameters are defined, Opposition must serve. Endeavour, therefore, in silence, stasis, and darkness to conjure that which mirrors the Unmanifest in perfection.

Daniel A. Schulke, Ars Philtron - On the Alchemic of the Sabbath, pgs. 30-32

#traditional witchcraft#witchcraft#cultus sabbati#daniel schulke#ars philtron#alchemy#occult#quotes#excerpt#magic

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some serious considerations on marriage. Wherein (by way of caution and advice to a friend) its nature, ends, events, concomitant accidents, &c. are examined. Conjugium Conjurgium

Seymar, William. (William Seymar is a pseudonymous anagram for William Ramsey.) Cf. Halkett and Laing Conjugium conjurgium: or, some serious considerations on marriage. Wherein (by way of caution and advice to a friend) its nature, ends, events, concomitant accidents, &c. are examined. By William Seymar Esquire. London: printed for John Amery at the Peacock over against St. Dunstan’s Church in…

View On WordPress

#Conjugium conjurgium#Early Conduct Book#Early modern advice book#early printed books#English marriage customs#Sex relations

0 notes

Photo

@acetyleneactor

I Married a Witch (René Clair, 1942)

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post-Shadowbringers Fics

Blinding (nsft)

Indulgence

Domiciliary

Sub Rosa (nsft)

Dayspring (nsft)

Solicitude

Suspire

Two Elezen One Catgirl (Wyrmelliferel)

Compersion (nsft, Wyrmelliferel)

Coeruleus (nsft, Wyrmelliferel)

Felidae (nsft, Wyrmelliferel)

Sustained

Post Meridian

Tea Time

Lullaby

Vernal

Amor-rot

Forged in Fury, Tempered in Ice

Caldor

Portraiture

Anniversaire

Companion

Conjugium

Little

Garden

Entanglement

Egress

Reverie

Sweet Song

Drawn

Reverie Reflected

Sprint

Balneum

Sway

(Post 5.3)

Remigro

Ancient Words

Lubentia (nsft)

Bound

Célèbre

Development

Telling the Bees

Telling

Conflicted

Acta Diurna

Memini

Propriety (Estinyan, nsft implied)

How Betula Got Her Name

Missive

A Family in Starlight

Dulcis Somnia

Expergo (Wyrmelliferel)

Salinity

Amiss(ive)

Falconry (Estinyan)

Hearthward

Reclaimed

Tempestuous

Eternal Devotion

Complement (takes place before 5.3)

Advenientia

Devoir

Anniversaire, Another

Receptum

The Hand that Rocks the Cradle

A More Perfect Union

Positions (approaching angst)

0 notes

Photo

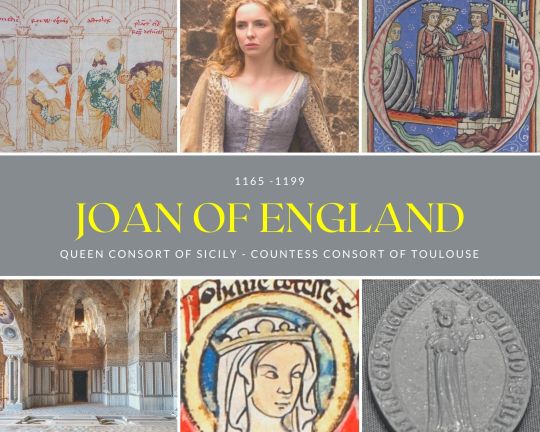

THE PLANTAGENET QUEEN CONSORTS OF SICILY - part 1

“Tanti ergo mysterii ratione, simul & veneratione inducti nos Will. divina favente clementia, Rex Siciliae, Ducatus Apuliae, & Principatus Capuae, Johannam Puellam Regii excellentia sanguinis illustrissimam, Filiam Henrici magnifici Regis Anglorum, divino nutu & felici auspicio, sacri lege matrimonii & maritali nobis foedere copuIamus, ut bonum conjugium castae dilectionis fides exhibeat; unde nobis in posterum proles Regia, Deo dante, succedat quae, divini gratia muneris, virtutum simul & generis titulo ad Regni possit & debeat festigium sublimari.”

in Foedera, conventiones, literæ, et cujuscunque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliæ et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices, principes, vel communitates, ab ineunte sæculo duodecimo, viz. ab anno 1101…, p.17

Joan was born in Angers, France, on October 1165 to Henry II, first Plantagenet King of England, and Eleanor, titular Duchess of Aquitaine (“Regina Alienor, mense Octobris, Amdegavis peperit filiam, et vocata est in baptismate Johanna.” in Chronique de Robert de Torigny, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel, I, p. 357). She was the seventh child (and third and last daughter) and, among her siblings, she could count future Kings of Egland, Richard I Lionheart and John I Lackland.

As a child, and together with her younger brother John, she was sent to Fontevrault Abbey (which benefitted from the Plantagenets’ protection and support), where she would be prepared for a bright future, possibly as a queen consort somewhere in Europe.

As a matter of fact, Henry had tried to marry her off to the Kings of Aragon or Navarre, although without success. In 1169, when Joan was still four, her father had begun negotiation to get his daughter engaged to Guglielmo II of Sicily. At first, even this attempt appeared to be fruitless, as the Sicilian King would have preferred to ally (via marriage) himself with the Byzantine Emperor, Manouel I Komnenos. As the Emperor got, instead, closer to Frederick I Hohenstaufen, Guglielmo resumed his negotiations with Henry II.

In 1176 Guglielmo of Sicily officially asked permission to marry Joan, who had at that time already left the Abbey and reached England. On May 20th of the same year, Henry officialized his permission and, by the end of August, Joan set off from Southampton, headed for her new Kingdom. After a difficult journey by sea (the future bride had to stop in Naples, where she celebrated Christmas), she finally reached Palermo in late January 1177.

Guglielmo and Joan got married in the Royal Chapel (it’s not certain if in Palermo or Monreale) and, on February 13th, Joan was crowned (together with her husband, at his second coronation) Queen of Sicily in Palermo’s Cathedral (“Convocatis autem rex Guilielmus Proceribus Sicilie et magna Populi multitudine, prenominatam filiam Regis Anglie in Cappella sua desponsavit, et se et eam gloriose coronari fecit, et sollemnes de illa nuptias celebravit Anno MCLXXVI, mense Februarii, Ind. X ” in Chronicon Romualdi II, archiepiscopi Salernitani, p. 41). Joan’s coronation should be considered a peculiar event for her time since it was already unusual for 12th-century queens to be crowned, but it was even rarer they got anointed with the holy chrism. Even though the joint coronation might lead us to think she would, from now on, regarded as equal to her husband, a co-regent, in reality, that ceremony was more a way to consecrate her role as a consort and (hopefully) mother of the future king. Guglielmo bestowed on his wife a rich dowry, worthy of a Queen, which included the lordship of Monte Sant’Angelo, the cities of Siponto and Vieste, the castles of Alesina, Pesco, Capracotta, Barano, Sirico and many other estates (“Comitatum Monti Sancti Angeli, Civitatem Siponti & Civitatem Vestae cum omnibus justis tenementis & pertinentiis earum. In servitio autem concedimus ei, de Tenementis Comitis Golfridi, Alesine, Peschizam, Bicum, Caprile, Baranum, & Sfilizum, & omnia alia quae idem Comes de honore eiusdem Comitatus Monti Sancti Angeli tenere dinoscitur” in Foedera, conventiones, literæ, et cujuscunque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliæ et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices, principes, vel communitates, ab ineunte sæculo duodecimo, viz. ab anno 1101…, p.17 ).

In his Chronica, Abbot Robert of Torigny records that Guglielmo and Joan had a son, Boemondo, who was invested by his father with the Duchy of Apulia (“Audivimus a quibusdam quod Johanna, uxor Guillermi regis Siciliae, filia Henrici regis Anglorum, peperit ei filium primogenitum, quem vocaverunt Boamundum. Qui cum a baptismate reverteretur, pater investivit eum ducatu Apuliae per aureum sceptrum, quod in manu gerebat.” in Chronique de Robert de Torigny, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel, II, p. 115). If Robert de Torigny is to be believed (which is unlikely), that would mean Bohemond died as an infant since Guglielmo died on November 18th 1189 without living issues (“[…] alteram duxit Siciliae rex Willelmus, qui prole caruit […]” in Matthæi Parisiensis, monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica majora, p. 326).

The lack of a direct heir gave rise to a succession crisis. The rightful heir was Guglielmo’s aunt, Costanza. What made Costanza’s claim less appealing in her future subjects’ eyes was her marriage to Frederick I Hohenstaufen’s son, Heinrich. To many, the perfect alternative to Costanza, a woman married to a foreign prince, was Tancredi of Lecce, the last (illegitimate) male representative of the Hauteville house in Italy. Taking advantage of the fact that Costanza and her husband were, at that moment, stuck in Germany, Tancredi was crowned King of Sicily in January 1190.

Having lost her role as a Queen consort, and lacking an heir which would have consented her to act as a regent, Joan was confined by Tancredi in the Zisa Palace, inside late Guglielmo’s harem, amid many Arab born beauties, and closely guarded by Muslim eunuchs.

In that same year, Joan’s brother, Richard (who had succeeded his father the year before), on his way to the Holy Land, arrived in Sicily (obligatory passage towards the Middle Eastern) together with French King, Philippe II Auguste. Richard demanded King Tancredi to release Joan, give back to her dowry (which had been seized by the Sicilian King following Guglielmo’s death) and financially support the Third Crusade as it had been previously agreed upon by the late king. At first, Tancredi ignored Richard’s requests, limiting himself to just deliver Joan to her kingly brother on September 28th. The English King retaliated by militarily occupying Messina, where he ordered the construction (or the renovation) of a wooden castle commonly known as Matagrifone (lit. “killing Griffones”, where the Grifoni/Griffones stands for Levantines and Greeks, as they were called by Northern Europeans) and from where his troops pillaged and massacred the population. The long sojourn in Sicily put a strain on the relationship between the two Kings, already so different (“The king of France, whatever transgression his people committed, or whatever offence was committed against them, took no notice and held his peace; the king of England esteeming the country of those implicated in guilt as a matter of no consequence, considered every man his own, and left no transgression unpunished, wherefore the one was called a Lamb by the Griffones, the other obtained the name of a Lion.” in The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes concerning the deeds of Richard the First, King of England, p. 17-18). Philippe Augustus didn’t approve of Richard’s behaviour and arrived to plot against him together with Tancredi. The tense situation led the two allies to meet to talk it out. They reached an agreement, which included the dissolution of the betrothal between Richard and Philippe’s sister, Alys, and the pledge to defend each other’s lands as if they were their own.

After a brief stay in Messina (and after, it is said, having charmed Philippe Augustus), Joan was sent by her brother on the other side of the Messina Strait, to the newly conquered Bagnara Calabra, where she was joined by her mother and Berengaria of Navarre, Richard’s new fiancée. Finally, at the beginning of March 1191, a treaty was signed between Tancredi and Richard. Tancredi had to reimburse Joan for her dowry (which the Sicilian King was going to keep) with almost 570kg of gold. Moreover, one of Tancredi’s daughters would in future marry Arthur of Brittany, Richard’s nephew and heir. If the marriage would never take place, the Sicilian King had to pay Richard a further sum of 570kg of gold.

In April 1191, the English party set sail towards the Holy Land (the Frenchmen had already departed). A storm dispersed the fleet, separating Richard from his sister and future wife. The women (and the treasure ship) reached Cyprus, where they were taken prisoners by Isaakios Komnēnos, ruler of the island. At the beginning of May, Richard arrived in Cyprus and demanded his sister and fiancée’s release. Since Isaakios refused, the English King attacked and occupied the island. The former ruler was forced to surrender, he was then imprisoned and shackled in silver chains since Richard had promised him he would not be put in irons. Before leaving Cyprus, Richard married Berengaria and sold the island to the Knights Templar. The English army finally arrived in Acre in June, accompanying (as a prisoner) them was the so-called Damsel of Cyprus, Isaakios’s daughter and heiress.

Arabic sources state that around September Richard had tried to come to terms with Salah al-Din, by offering his sister Joan as spouse to the Sultan’s brother, Al-Adil. The records add that this match was made impossible by the Christian clergy’s refusal to allow it without a pre-emptive conversion of the future husband (Joan’s objection to this union wouldn’t have mattered much), but Richard might have just tried to gain time since, when Salah al-Din accepted the offer, the English King backed off, stating they would need a Papal dispensation to let a dowager Queen marry an infidel. In lieu of his sister, Richard then offered his niece’s hand. At this point, Salah al-Din broke the negotiations.

Together with her sister-in-law, Joan left the Holy Land by the end of 1192 and most certainly lived with Berengaria until 1196, when she married (by order of her brother Richard) Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse and Marquis of Provence (“MCXCVI […] Eodem anno comes de Sancto Egidio duxit in uxorem Johannam sororem Ricardi regis, quondam reginam Siciliae……” in Annales Monastici, Annales de Burton, vol. I, p. 192). Raymond, nine years her senior, was at his fourth marriage. The union between the Plantagenet princess and the Count of Toulouse finally put an end to the families’ (Aquitaine and Toulouse) feud as Richard gave up on his claim on Toulouse.In 1197, in Beucaire, Joan gave birth to a son Raymond (“MCXCVII. Johanna comitissa de Sancto Egidio, soror Ricardi regis Angliae, peperit Reimundum suum primogenitum” in Annales Monastici, vol. I, p. 192), followed by, the next year, Jeanne (“V. Kal. Junii, Anno MCCLV, obiit illustrissima Johanna filia Raymundi Comitis & Regina Johanna, uxor quondam Domini Bernardi de Turre” Extrait de l’ancien Obituaire de l’abbaye de la Vaissi en Auvergne in Histoire Genealogique de la Maison D’Auvergne, p. 499). The marriage between Joan and Raymond is described by some as unhappy, but the reason behind it perhaps could be that, because he had shown certain sympathies towards the Catharism, Raymond was seen as a heretic. In his Chronique, 13th-century chronicler Guillaume de Puylaurens, writes how, pregnant of her third child, and intending to avenge the many injuries suffered by her husband by the hand of his enemies, she besieged the castle of Casser. Despite her good intentions, her expedition failed and so Joan ran to her brother Richard to ask for his help, to help and support her husband. It must have been a great shock for her when, along the way, she found out her brother was dead (“Comme sa mère était une femme énergique, prévoyante et ayant à coeur de se venger des offenses que bien des Grands et des Capitaines avaient faites à son mari, à peine eut-elle fait ses relevailles, qu'elle marcha contre le Sire de St.-Félix , et assiégea le château de Casser. Mais cette passer en secret aux assiégés des armes et ce qui leur était nécessaire. Vivement émue de ces menées, elle quitta le camp, dont elle fut à peine libre de sortir; car les traîtres mirent le feu à son logis, et elle s’ échappa au milieu des flammes. Poussée par le ressentiment de cette in jure, elle accourut vers son frère, le roi Richard, pour en obtenir satisfaction; elle ne trouva que son cadavre. Richard avait été tué à la guerre, et ce nouveau chagrin causa la mort de Jeanne.” in Chronique de Maître Guillaume de Puylaurens sur la guerre des Albigeois – 1202-1272, p. 20-21). According to the Annales of the Winchester Priory, Joan gave orders that the soldier who had mortally injured her brother was to be tortured, blinded, skinned and quartered (“[…]sed Marchadeus misit eum clam rege ad Johannam comitissam Sancti Egidii sororem regis, qui fecit ei evelli ungues pedum et manuum et oculos, et postea excoriari et equis detrahi.” in Annales Monastici: Annales monasterii de Wintonia, A.D. 519-1277, p. 71). John had succeeded his brother Richard on the throne, and Joan thought about asking for her other brother’s help. She reached him in Normandy, but all she could get was an annuity of 100 golden marks. Wearied and heartbroken, she felt her end was near and, despite being married and pregnant, she asked permission to take religious vows and become a nun in Fontevrault Abbey. Despite some initial reserve, after seeing how determined she was, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter, caved in and consecrated her to God and to the order of Fontevrault. Joan died on September 24th 1199 in Rouen. She was 33 years old. After she died, her belly was opened and her child, a boy, was extracted. Baptised as Richard, her son lived only for a couple of hours and was later buried in Rouen’s Cathedral. (“[…]cette princesse ayant obtenu la grâce qu'elle avoit demandée avec tant d'instance, mourut- bientôt après, le 24 de septembre de l'an 1199, &, comme elle étoit avancée dans sa grossesse, on l'ouvrit dès qu'elle fut morte. On lui tira un enfant qui eut le temps de recevoir le baptême & qui, étant décédé presque aussitôt, fut inhumé dans l'église de Notre-Dame de Rouen.” in Histoire générale de Languedoc, p. 190). According to her wishes, she was buried in Fontevrault Abbey, at her father’s feet and next to her brother Richard. She would be later joined by her mother (1205), buried next to Henry II, and her son Raymond (1249), buried next to her (“Quant au corps de la comtesse, la prieure de Fontevrault l'apporta avec elle dans cette abbaye, où il fut inhumé aux pieds du roi Henri H, père de cette princesse, & à côté du roi Richard, son frère.” in Histoire générale de Languedoc, p. 190). In her will, she presents herself as “queen Joan of Sicily”, leaving aside the humbler title of Countess of Toulouse. Admist the generous distribution of bequests among her servants, many churches and the main beneficiary, the Abbey of Fontevrault, Joan assigned an annual payment of 20 marcs to the Abbey to commemorate “the anniversary of the king of Sicily and herself”.

Her husband Raymond would marry two more times, with the Damsel of Cyprus, and after divorcing her, with Leonor of Aragon. He would be succeeded in 1222 by his and Joan’s son, Raymond VII.

Sources

- Annales Monastici, Annales de Burton

- Annales Monastici: Annales monasterii de Wintonia, A.D. 519-1277

- Bowie, Colette, To Have and to Have Not: The Dower of Joanna Plantagenet, Queen of Sicily (1177–1189), in Queenship in the Mediterranean. Negotiating the Role of the Queen in the Medieval and the Early Modern Eras

- Calendar of documents preserved in France, illustrative of the history of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol.1. A.D. 918-1206

- Chronicle of Richard of Devizes concerning the deeds of Richard the First, King of England

- Chronique de Maître Guillaume de Puylaurens sur la guerre des Albigeois (1202-1272)

- Chronique de Robert de Torigni, abbé du Mont-Saint-Michel

- Delle Donne, Fulvio , GIOVANNA d'Inghilterra, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani

- Foedera, conventiones, literæ, et cujuscunque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliæ et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices, principes, vel communitates, ab ineunte sæculo duodecimo, viz. ab anno 1101

- Histoire genealogique de la Maison D’Auvergne

- Histoire générale de Languedoc

- Matthæi Parisiensis, monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica majora

- Wieruszowski, Helene , The Norman Kingdom of Sicily and the Crusades, in A History of the Crusades, vol. II, The Later Crusades, 1189-1311

#History#Women#Women in history#Historical women#English history#Joan of England#Guglielmo ii#Richard i lionheart#Norman swabian Sicily#People of Sicily#Women of Sicily#Myedit#Historyedit#House of Hauteville

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@acetyleneactor

James Stewart and his wife Gloria

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE BOOK OF RUTH - From The Douay-Rheims Bible - Latin Vulgate

Chapter 4

INTRODUCTION

This Book is called Ruth, from the name of the person whose history is here recorded; who, being a Gentile, became a convert to the true faith, and marrying Booz, the great-grandfather of David, was one of those from whom Christ sprang according to the flesh, and an illustrious figure of the Gentile church. It is thought this book was written by the prophet Samuel. Ch. --- The Holy Ghost chose that the genealogy of David, and of the Messias, should be thus more clearly ascertained. Theodoret. --- Christ proceeded from the Gentiles, as well as from the Jews, and his grace is given to both. W. --- Send forth, 0 Lord, the lamb, the ruler of the earth, from Petra. Isai. xvi. This was the capital city of Arabia Petrea, where Ruth is supposed to have lived, (Tostat) being, according to the Chal. &c. the daughter of Eglon, king of Moab. The Jews also pretend that Booz was the same person as Abesan, the judge. But it is by no means certain to what period this history belongs. Usher places it under Samgar, about 120 years after Josue. C. --- Salien believes that the famine, which obliged Elimelech to leave Bethlehem, happened under Abimelech, and that Noemi returned in the 7th year of Thola, A.C. 1243. This event certainly took place under some of the judges; so that we may consider this book as an appendix to the preceding, like the last chapters, (Judg. xvii. &c. H.) and a preface to the history of the kings. C.

The additional Notes in this Edition of the New Testament will be marked with the letter A. Such as are taken from various Interpreters and Commentators, will be marked as in the Old Testament. B. Bristow, C. Calmet, Ch. Challoner, D. Du Hamel, E. Estius, J. Jansenius, M. Menochius, Po. Polus, P. Pastorini, T. Tirinus, V. Bible de Vence, W. Worthington, Wi. Witham. — The names of other authors, who may be occasionally consulted, will be given at full length.

Verses are in English and Latin.

HAYDOCK CATHOLIC BIBLE COMMENTARY

This Catholic commentary on the Old Testament, following the Douay-Rheims Bible text, was originally compiled by Catholic priest and biblical scholar Rev. George Leo Haydock (1774-1849). This transcription is based on Haydock's notes as they appear in the 1859 edition of Haydock's Catholic Family Bible and Commentary printed by Edward Dunigan and Brother, New York, New York.

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

Changes made to the original text for this transcription include the following:

Greek letters. The original text sometimes includes Greek expressions spelled out in Greek letters. In this transcription, those expressions have been transliterated from Greek letters to English letters, put in italics, and underlined. The following substitution scheme has been used: A for Alpha; B for Beta; G for Gamma; D for Delta; E for Epsilon; Z for Zeta; E for Eta; Th for Theta; I for Iota; K for Kappa; L for Lamda; M for Mu; N for Nu; X for Xi; O for Omicron; P for Pi; R for Rho; S for Sigma; T for Tau; U for Upsilon; Ph for Phi; Ch for Chi; Ps for Psi; O for Omega. For example, where the name, Jesus, is spelled out in the original text in Greek letters, Iota-eta-sigma-omicron-upsilon-sigma, it is transliterated in this transcription as, Iesous. Greek diacritical marks have not been represented in this transcription.

Footnotes. The original text indicates footnotes with special characters, including the astrisk (*) and printers' marks, such as the dagger mark, the double dagger mark, the section mark, the parallels mark, and the paragraph mark. In this transcription all these special characters have been replaced by numbers in square brackets, such as [1], [2], [3], etc.

Accent marks. The original text contains some English letters represented with accent marks. In this transcription, those letters have been rendered in this transcription without their accent marks.

Other special characters.

Solid horizontal lines of various lengths that appear in the original text have been represented as a series of consecutive hyphens of approximately the same length, such as ---.

Ligatures, single characters containing two letters united, in the original text in some Latin expressions have been represented in this transcription as separate letters. The ligature formed by uniting A and E is represented as Ae, that of a and e as ae, that of O and E as Oe, and that of o and e as oe.

Monetary sums in the original text represented with a preceding British pound sterling symbol (a stylized L, transected by a short horizontal line) are represented in this transcription with a following pound symbol, l.

The half symbol (1/2) and three-quarters symbol (3/4) in the original text have been represented in this transcription with their decimal equivalent, (.5) and (.75) respectively.

Unreadable text. Places where the transcriber's copy of the original text is unreadable have been indicated in this transcription by an empty set of square brackets, [].

Chapter 4

Upon the refusal of the nearer kinsman, Booz marrieth Ruth, who bringeth forth Obed, the grandfather of David.

[1] Then Booz went up to the gate, and sat there. And when he had seen the kinsman going by, of whom he had spoken before, he said to him, calling him by his name: Turn aside for a little while, and sit down here. He turned aside, and sat down.

Ascendit ergo Booz ad portam, et sedit ibi. Cumque vidisset propinquum praeterire, de quo prius sermo habitus est, dixit ad eum : Declina paulisper, et sede hic : vocans eum nomine suo. Qui divertit, et sedit.

[2] And Booz taking ten men of the ancients of the city, said to them: Sit ye down here.

Tollens autem Booz decem viros de senioribus civitatis, dixit ad eos : Sedete hic.

[3] They sat down, and he spoke to the kinsman: Noemi, who is returned from the country of Moab, will sell a parcel of land that belonged to our brother Elimelech.

Quibus sedentibus, locutus est ad propinquum : Partem agri fratris nostri Elimelech vendet Noemi, quae reversa est de regione Moabitide :

[4] I would have thee to understand this, and would tell thee before all that sit here, and before the ancients of my people. If thou wilt take possession of it by the right of kindred: buy it and possess it: but if it please thee not, tell me so, that I may know what I have to do. For there is no near kinsman besides thee, who art first, and me, who am second. But he answered: I will buy the field.

quod audire te volui, et tibi dicere coram cunctis sedentibus, et majoribus natu de populo meo. Si vis possidere jure propinquitatis, eme, et posside : sin autem displicet tibi, hoc ipsum indica mihi, ut sciam quid facere debeam : nullus enim est propinquus, excepto te, qui prior es : et me, qui secundus sum. At ille respondit : Ego agrum emam.

[5] And Booz said to him: When thou shalt buy the field at the woman's hand, thou must take also Ruth the Moabitess, who was the wife of the deceased: to raise up the name of thy kinsman in his inheritance.

Cui dixit Booz : Quando emeris agrum de manu mulieris, Ruth quoque Moabitidem, quae uxor defuncti fuit, debes accipere : ut suscites nomen propinqui tui in haereditate sua.

[6] He answered: I yield up my right of next akin: for I must not cut off the posterity of my own family. Do thou make use of my privilege, which I profess I do willingly forego.

Qui respondit : Cedo juri propinquitatis : neque enim posteritatem familiae meae delere debeo : tu meo utere privilegio, quo me libenter carere profiteor.

[7] Now this in former times was the manner in Israel between kinsmen, that if at any time one yielded his right to another: that the grant might be sure, the man put off his shoe, and gave it to his neighhour; this was a testimony of cession of right in Israel.

Hic autem erat mos antiquitus in Israel inter propinquos, ut siquando alter alteri suo juri cedebat, ut esset firma concessio, solvebat homo calceamentum suum, et dabat proximo suo : hoc erat testmonium cessionis in Israel.

[8] So Booz said to his kinsman: Put off thy shoe. And immediately he took it off from his foot.

Dixit ergo propinquo suo Booz : Tolle calceamentum tuum. Quod statim solvit de pede suo.

[9] And he said to the ancients and to all the people: You are witnesses this day, that I have bought all that was Elimelech's, and Chelion's, and Mahalon's, of the hand of Noemi:

At ille majoribus natu, et universo populo : Testes vos, inquit, estis hodie, quod possederim omnis quae fuerunt Elimelech, et Chelion, et Mahalon, tradente Noemi :

[10] And have taken to wife Ruth the Moabitess, the wife of Mahalon, to raise up the name of the deceased in his inheritance lest his name be cut off, from among his family and his brethren and his people. You, I say, are witnesses of this thing.

et Ruth Moabitidem, uxorem Mahalon, in conjugium sumpserim, ut suscitem nomen defuncti in haereditate sua, ne vocabulum ejus de familia sua ac fratribus et populo deleatur. Vos, inquam, hujus rei testes estis.

[11] Then all the people that were in the gate, and the ancients answered: We are witnesses: The Lord make this woman who cometh into thy house, like Rachel, and Lia, who built up the house of Israel: that she may be an example of virtue in Ephrata, and may have a famous name in Bethlehem:

Respondit omnis populus, qui erat in porta, et majores natu : Nos testes sumus : faciat Dominus hanc mulierem, quae ingreditur domum tuam, sicut Rachel et Liam, quae aedificaverunt domum Israel : ut sit exemplum virtutis in Ephratha, et habeat celebre nomen in Bethlehem :

[12] And that the house may be, as the house of Phares, whom Thamar bore unto Juda, of the seed which the Lord shall give thee of this young woman.

fiatque domus tua, sicut domus Phares, quem Thamar peperit Judae, de semine quod tibi dederit Dominus ex hac puella.

[13] Booz therefore took Ruth, and married her: and went in unto her, and the Lord gave her to conceive and to bear a son.

Tulit itaque Booz Ruth, et accepit uxorem : ingressusque est ad eam, et dedit illi Dominus ut conciperet, et pareret filium.

[14] And the women said to Noemi: Blessed be the Lord, who hath not suffered thy family to want a successor, that his name should be preserved in Israel.

Dixeruntque mulieres ad Noemi : Benedictus Dominus, qui non est passus ut deficeret successor familiae tuae, et vocaretur nomen ejus in Israel.

[15] And thou shouldst have one to comfort thy soul, and cherish thy old age. For he is born of thy daughter in law: who loveth thee: and is much better to thee, than if thou hadst seven sons.

Et habeas qui consoletur animam tuam, et enutriat senectutem : de nuru enim tua natus est, quae te diligit : et multo tibi melior est, quam si septem haberes filios.

[16] And Noemi taking the child laid it in her bosom, and she carried it, and was a nurse unto it.

Susceptumque Noemi puerum posuit in sinu suo, et nutricis ac gerulae fungebatur officio.

[17] And the women her neighbours, congratulating with her and saying: There is a son born to Noemi: called his name Obed: he is the father of Isai, the father of David.

Vicinae autem mulieris congratulantes ei, et dicentes : Natus est filius Noemi : vocaverunt nomen ejus Obed : hic est pater Isai, patris David.

[18] These are the generations of Phares: Phares begot Esron,

Hae sunt generationes Phares : Phares genuit Esron,

[19] Esron begot Aram, Aram begot Aminadab,

Esron genuit Aram, Aram genuit Aminadab,

[20] Aminadab begot Nahasson, Nahasson begot Salmon,

Aminadab genuit Nahasson, Nahasson genuit Salmon,

[21] Salmon begot Booz, Booz begot Obed,

Salmon genuit Booz, Booz genuit Obed,

[22] Obed begot Isai, Isai begot David.

Obed genuit Isai, Isai genuit David.

Commentary:

Ver. 1. Gate, where justice was administered. --- Calling. Heb. Ploni Almoni. C. --- Prot. " Ho! such a one." H. --- This form of speech is used concerning a person whose name we know not, or will not mention. 1 K. xxi. 2. C. --- The name of this man is buried in eternal oblivion, perhaps because he was so much concerned about the splendour of his family, that he would not marry the widow of his deceased relation. T.

Ver. 2. Here, as witnesses, not as judges, v. 9. C. --- This number was requisite in matters of consequence. Grotius.

Ver. 3. Will sell. Some Latin copies read, "sells, or has sold." But the sequel shews that she was only now disposed to do it. But what right had Noemi or Ruth to the land, since women could not inherit? The latter might indeed retain her title, as long as she continued unmarried. But Noemi only acted in her behalf. Selden thinks that their respective husbands had made them a present of some land. Josephus (v. 11) asserts, that the person whom Booz addressed had already possession, and that he resigned his claim, as he would not take au other wife. C. --- Our brother. He was his nephew, and calls him brother, as Abraham did Lot. W.

Ver. 4. This. Heb. "I thought to uncover thy ear," or to admonish thee. Virgil (frag.) uses a similar expression, Mors aurem vellens, vivite, ait, venio: "Death pulls the ear; live now, he says, I come." --- Not. Heb. printed erroneously, "But if he will not redeem it." Ken.

Ver. 5. When. Heb. again corruptly, "On the day thou buyest the land of the hand of Noemi, I will also buy it of Ruth," &c. It ought to be, conformably to some MSS. and the ancient versions, "thou must also take Ruth," v. 10. Capel, p. 144, and 362. Kennicott. H. --- We see here the observance of two laws, the one preserving the inheritance in the same family, and the other obliging the next of kin to marry the widow of the deceased, if he would enjoy his land. Lev. xxv. 10. Deut. xxv. 5. C. --- Such widows as designed to comply with this condition, took possession of the land on the death of their husband, and conveyed it to those whom they married, till their eldest son became entitled to it. Abulensis, q. 30 to 61. --- Inheritance. The son to be born, would be esteemed the heir of his legal parent. M.

Ver. 6. Family. Heb. "I cannot redeem it for myself, lest I spoil my own inheritance." He was afraid of having too many children, and sensible that the first son that should be born of the proposed marriage, would not be counted as his. H. --- The miserable Onan had the same pretext. Gen. xxxviii. 9. Chal. "Since I cannot make use of this privilege, having already a wife, and not being allowed to take another, as that might cause dissensions in my family, and spoil my inheritance, do thou redeem it,….as thou art unmarried."

Ver. 7. Israel. Heb. "and this was the testimony in Israel." The ceremony here specified is very different from that which the law prescribed. Deut. xxv. 7. But Josephus says, that they complied with all the regulations of the law, and that Ruth was present on this occasion. C. --- Perhaps the law was not executed in all its rigour, when another was found to marry the widow, (W.) and when no real brother was living. T.

Ver. 9. Chelion. As Orpha, his widow, took no care to comply with the law, all his possessions devolved on his brother’s posterity. M. --- It was presumed that she would marry some Moabite. C.

Ver. 10. Moabitess. The sons of Elimelech were excused in taking such women to wife, on account of necessity, and to avoid the danger of incontinence, which is a greater evil. Booz was under another sort of necessity, and was bound to comply with the law; (C.) so that he was guilty of no sin, as Beza would pretend. T. --- Some also remark, that the exclusion of the people of Moab from the Church of God, regarded not the females, (S. Aug. q. 35, in Deut. Serar. T. &c.) particularly if they embraced the true religion. According to the Rabbins, Obed should have been accounted a Moabite, as they say children follow the condition of their mothers: but we need not here adopt their decisions. --- People. Heb. "and from the gate of his place." In the assemblies, the legal son of Mahalon would represent him, though he was also considered as the son of Booz, at least if the latter had no other, as was probably the case.

Ver. 11. Israel, by a numerous posterity. --- That she. Heb. "mayst thou acquire riches," &c. C. --- Prot. "do thou (Booz) worthily in," &c. H. --- Ephrata: another name of Bethlehem. Ch.

Ver. 12. Phares. His family was chief among the five, descended from Juda. M.

Ver. 14. Successor. Heb. "redeemer, that his (Booz, or the Lord's) name," &c. C.

Ver. 15. Comfort. Heb. "to make thy soul revive."

Ver. 17. Obed; "serving," to comfort the old age of Noemi, (v. 15,) who gave him this' name. (Serar. q. 14,) at the suggestion of her neighbours. M.

Ver. 18. These. Hence the design of the sacred writer becomes evident, (C.) to shew the genealogy of David, from whom Christ sprang, as it had been foretold. See Gen. xlix. Mat. i. &c. W.

Ver. 19. Aram. He is called Ram in Heb. and 1 Par. ii. 9.

Ver. 20. Salmon. Heb. and Chal. Salma, (H.) though we read Salmon in the following verse. C. --- This is one argument adduced by Houbigant, to shew that this genealogy is now imperfect. He concludes that Salma ought to be admitted, as well as Salmon; and, as the reason for calling the first son of Ruth, Obed, "serving or ploughing," seems rather harsh, as we should naturally expect some more glorious title. He thinks that the immediate son of Ruth was called Jachin, "he shall establish;" and that Solomon called one of the pillars before the temple by his name, as he did the other Booz, "in strength," in honour of his ancestors. Baz icin means, "In strength (or solidity) it (he) shall (stand or) establish." As the son of Booz established his father's house, (v. 10. 11,) so these pillars denoted the stability of the temple. We must thus allow that the hand of time has mutilated the genealogy of David, and that two ought to be admitted among his ancestors, who have been here omitted, as S. Matthew likewise passes them over as well as three others, who were the descendants of Joram. The same omission of Jachin occurs 1 Paral. ii. 11, where we find Salma instead of Salmon. Houbigant supposes that the sacred writers, Esdras and S. Matthew, gave the genealogies as they found them, without correcting the mistakes of transcribers. Chronolog. sacra, p. 81. But there might be some reason for the omission which we do not know; and Nahasson, Booz, and Joram might be said to beget Salmon, Obed, and Jechonias, though they were not their immediate children. Salien and many others assert, that there were three of the name of Booz, succeeding each other, so that six persons instead of four fill up the space of 440 years, from the taking of Jericho till the building of the temple. Salien, A. 2741, in which year he places the birth of the third Booz, who married Ruth, seventy years afterwards. Petau allows 520 years from the coming out of Egypt till the fourth year of Solomon, so that he leaves above 420 years to the three generations of Booz, Obed, and Isai. But he prudently passes over this chronological difficulty. Usher supposes that each of these people were almost 100 years old when they had children; and he produces many examples of people who lived beyond that age, but he does not mention any, since the days of Moses, who had children at such an advanced age, much less that many in the same family, and in succession, were remarkable for such a thing. Moreover, according to Houbigant's chronology, Booz and Obed must have had children when they were almost 120, and Isai in his 107th year. But by admitting Salma and Jachin, the five persons might each have sons when they were about seventy, and thus would complete 347 years. See C. ii. 1. H.

Ver. 22. David, the king, whom Samuel crowned, though he did not live to see him in the full enjoyment of his power, (H.) as he died before Saul. C. --- Thus the greatest personages have people of mean condition among their ancestors, that none may be too much elated on account of their high birth. Ruth, notwithstanding her poverty, was a striking figure of the Christian Church. H. --- The Gentiles were strangers to Christ, on account of their errors, but related to him in as much as they were his creatures. Their miserable condition pleaded hard for them, that Jesus would receive them under his protection, espouse and give them rest and peace. Booz would, not marry Ruth till the nearer relation had refused, and thus brought dishonour on himself; (Deut. xxv.) so Jesus was principally sent to the lost sheep of the house of Israel, and did not send his apostles to the Gentiles till the Jews had rejected their ministry. C. --- See S. Amb. de fide, iii. 5. D. - Ruth was also a pattern of the most perfect virtues. See Louis de Puente. T.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conjugium satis est juvenem dominare ferocem.

Conjugium satis est juvenem dominare ferocem.

Qual o significado de “Conjugium satis est juvenem dominare ferocem.” ? Casarás e amansarás.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

@acetyleneactor

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some serious considerations on marriage. Wherein (by way of caution and advice to a friend) its nature, ends, events, concomitant accidents, &c. are examined. Conjugium Conjurgium

Some serious considerations on marriage. Wherein (by way of caution and advice to a friend) its nature, ends, events, concomitant accidents, &c. are examined. Conjugium Conjurgium

Seymar, William. (William Seymar is a pseudonymous anagram for William Ramsey.) Cf. Halkett and Laing Conjugium conjurgium: or, some serious considerations on marriage. Wherein (by way of caution and advice to a friend) its nature, ends, events, concomitant accidents, &c. are examined. By William Seymar Esquire. London: printed for John Amery at the Peacock over against St. Dunstan’s Church in…

View On WordPress

#Conjugium conjurgium#Early Conduct Book#Early modern advice book#early printed books#English marriage customs#Sex relations

0 notes

Text

Of - POWDERS, MAGNETS, ATOMS, MECHANICS

Of – POWDERS, MAGNETS, ATOMS, MECHANICS

Of the Curing and Causing of Wounds 527JBA. Walter Charleton The magnetick cure of wounds. 1650445J Digby, Kenelm, The Cure of Wounds By The Powder Of Sympathy 1658508J William Gibson.The farriers dispensatory 1721494J Mead A mechanical account of poisons in several essays 1702493J John Radcliffe (1650-1714) Pharmacopoeia Radcliffeana: or, Dr. Radcliff’s…

View On WordPress

#Conjugium conjurgium#English marriage customs#oligodynamic#The island of the day before.#The Powder of Sympathy

0 notes