#comte de foix

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Antoine de Bourbon, Roi de Navarre.

#royaume de france#royaume de navarre#maison de bourbon#antoine de bourbon#Antoine de Vendôme#roi de navarre#vive le roi#Duc de Vendôme#pair de france#duc de beaumont#comte de marle#engravings#Seigneur de La Fère#comte de foix#vicomte de béarn#french aristocracy#house of bourbon#kingdom of navarre#kingdom of france#bourbon vendôme#royalty#médiathèque michel-crépeau

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In total, Leonor governed Navarre as lieutenant, with some minor hiatuses, from 1455 to 1479, making her the effective ruler of the realm for nearly twenty five years. Out of her female predecessors, only Juana I served a longer period; however, Juana I was detached from the governance of the realm and physically distant from Navarre. Leonor however, remained in the kingdom throughout her lieutenancy, making her the female sovereign with the highest record of residency in Navarre.

One of the enabling factors for Leonor’s constant presence in the realm was the “Divide and Conquer” power-sharing mechanism that she employed with her husband, Gaston of Foix. Blanca and Juan had a similar division of duties, but unlike her parents’ often contrary objectives, all of Leonor and Gaston’s actions can be seen to be working toward their joint goals of obtaining the Navarrese crown and politically dominating the Pyrenean region. In order to achieve their ambitions, the couple were adept at working as a team even when physically seperated or carrying out divergent duties.

Politically, it appears that they took on different areas of negotiatiion. Gaston was the designated emissary to the French court, which was entirely appropriate as one of the French king’s leading magnates. One important example of his involvement in negotiations of this type include Gaston’s visit to the French court in the winter of 1461–62 to negotiate the marriage between their heir and the French princess, Magdalena, which ensured Louis XI’s backing for Leonor’s promotion to primogenita. Gaston also conducted negotiations on behalf of his father-in-law, Juan of Aragon, with the King of France, with a successful outcome in the case of the Treaty of Olite in April 1462, which was intimately connected to the marriage that Gaston was orchestrating for his son and Magdalena of France.

Even though Gaston normally took on the role of intermediary with the French crown, there are two letters issued by Leonor during her marriage in December 1466 as lieutenant of Navarre that show her involvement in French affairs. These letters were written during a period of extreme crisis, when Juan II’s difficulties in Catalonia were matched with Leonor’s continuing struggle with the Peralta clan in Navarre. In these letters, Leonor was playing on her familial connection to Louis XI, in hopes of his aid and backing, asking him to “commend this poor kingdom and the said princess to him [Louis XI] as one who is of his house.” Moreover, these letters show Leonor’s independent interaction in crucial diplomatic negotiations with France, both in receiving embassies directly from Louis and in sending her own personal ambassador, Fernando de Baquedano, with detailed instructions on how to proceed.

Gaston appears to have been more engaged with marital negotiations for their numerous offspring than Leonor. However, this may be due to the fact that the couple overwhelmingly chose French marriages for their children. Only three of Leonor’s children did not contract a French betrothal: Pierre who became a cardinal, a daughter who died young, and Leonor’s youngest son, Jacques (or Jaime), who married into the Navarrese nobility. Given the fact that Gaston was more intimately connected to the French court and the nobility of the Midi, it seems reasonable that he would take on the role of chief negotiator for these matches. All of the marital arrangements for their children were made in order for Gaston and Leonor to achieve their joint goals, the acquisition of the throne of Navarre and the consolidation of their power and influence in the Pyrenean region.

Another area where Gaston necessarily played a more central role was militarily. Robin Harris acknowledges Gaston’s successful military career and notes that after his useful military service to the French crown, “the comte was permitted by the [French] king in the last years of his life to employ his military resources in order to further his family’s interests in Navarre.” Gaston also performed many military services for his father-in-law; the agreement of 1455 that promoted Leonor and Gaston to the successors of the realm required Gaston to go to Navarre on Juan’s behalf and retake those areas that had fallen to the rebels “for the honor of the King of Navarre as well as for his own interests and those of the princess his wife."

However, there is some evidence for Leonor’s involvement in one military foray. In the winter of 1471, Leonor took part in a daring attempt to seize the capital, Pamplona, from her opponents, the Beaumonts. Leonor participated in an attempt to storm one of the city gates with a group of armed supporters. Moret notes that “this surprise was reckless; for it exposed the person of the princess to obvious risk and was somewhat rash.” Moreover, the element of surprise was ruined by the cries of her supporters shouting “ Viva la Princesa !” which alerted the Beaumont troops to the threat, and Leonor and her supporters were swiftly ejected from the city.

Like her mother, the noted peacemaker, Leonor was also involved in moves to reduce the civil discord in the realm. Zurita credited Leonor with “making a great effort to resolve the differences of the parties and subdue the kingdom into union and calm.” Leonor represented her father in negotiations for a truce with the supporters of the Principe de Viana on March 27, 1458, at Sang ü esa. Zurita notes, “The princess Lady Leonor was there at that time in Sangüesa and signed the treaty with the power of the king her father.” Leonor was instrumental in the forging of another truce that was contracted in Sangüesa, in January 1473, and she was also present at a conference with her father and her half-brother Ferdinand in Vitoria in 1476 “accompanied by the nobility of Navarre to renew the treatties . . . and attempt to arrive at a stable peace.

Although both spouses were named to the lieutenancy of Navarre, the documentary evidence clearly demonstrates that Leonor appears to have taken on the bulk of the administration of the realm. This was entirely appropriate as it was Leonor, not Gaston, who had the hereditary right to the crown. Moreover, it was logical for Leonor to remain in Navarre so that her husband could look after his own patrimonial holdings and continue to serve as a military commander for the King of France.

Leonor was an active lieutenant but she struggled to implement her rule fully across the kingdom, as many areas were dominated by the Beaumont faction who were opposed to her and her father Juan of Aragon. This meant that at times, she had no control or access to certain key cities in the realm, including the capital, as mentioned previously. Her grandfather’s impressive seat at Olite was the center of her sister’s court, but Leonor eventually regained her hold on the castle and used it as one of her primary residences between 1467 and 1475. Sangüesa remained an important base for Leonor, and she was also associated with Tudela on the southern edge of the kingdom.

Leonor’s difficulty in implementing her rule across the whole of the kingdom is illustrated by a prolonged struggle between the lieutenant and the town of Tafalla, which consistently refused to send representatives when she called together meetings of the Cortes. Tafalla was a center of Beaumont strength, which had supported her brother Carlos in his struggle with Juan of Aragon and was thus bitterly opposed to her appointment to the lieutenancy. Between 1465 and 1475 there is a series of missives from Leonor both summoning representatives from the town and then expressing disappointment when they failed to arrive. During this period, Leonor appears to have called a meeting of the Cortes at least six times, but the town consistently refused to send envoys to the assembly. There is a sense of increasing exasperation and anger in these documents at the repeated failure to participate in these important events. At one point, in late 1471, Leonor personally came to the town to give advance notice of her intent to call another Cortes the following summer, perhaps to circumvent any excuse that the town did not have sufficient time to send representatives, but Tafalla still did not participate in the assembly.

As her authority was contested, Leonor was keen to stress her agency and her position in the documents that she issued. However, at times she even struggled with the chancery; between 1472–73, Juan de Beaumont retained the seals of the kingdom and refused to let Leonor have access to them. In 1475, she granted a reduction in taxes to the important city of Estella acknowledging the reduced capacity of the city to pay after the population had shrunk from the effects of war and flooding. In this document she stressed her efforts to assist all of the urban centers of the realm, to help them recover from the years of civil conflict and devastation, “the other good towns of the said realm have been refurbished by our certain knowledge, special grace, our own change and royal authority.

Leonor’s address clause drew on all of her family and marital ties as a means of establishing her authority:

“Lady Leonor, by the grace of God princess primogenita , heiress of Navarre, princess of Aragon and Sicily, Countess of Foix and Bigorre, Lady of Bearn, Lieutenant general for the most serene king, my most redoubtable lord and father in this his kingdom of Navarre.”

The signet that Leonor used for the majority of her lieutenancy as well as her sello secreto had heraldic devises that mirror her address clause, bearing the arms Navarre, her family dynasty of Evreux, her husband’s counties of Foix, Béarn, and Bigorre, and finally the Trast á mara connections to Aragon, Castile, and Léon.

To sum up, Gaston and Leonor’s ability to divide up roles and responsibilities demonstrates the couple’s effective partnership, using each partner in the most appropriate arena. Moreover, this division was entirely necessary as the couple’s widespread territorial holdings and the demands of balancing the complicated and difficult political situation both within Navarre and the Midi and between France, Castile, and Aragon meant that both partners needed to be fully engaged and active in order to achieve their mutual goals and further their dynastic interests.

Even though Leonor and Gaston generally employed this mode of “Divide and Conquer” that left Leonor primarily responsible for the administration of Navarre while Gaston oversaw his own sizable patrimony, the couple did work together as a unit whenever possible. Documentary evidence shows that Gaston came to stay with Leonor in Navarre for short periods, particularly during the autumn of 1469 and 1470. There is also some additional evidence to indicate an earlier reunion in 1464, which appears to indicate a desire on the part of the couple to be together. Gaston and his party were stuck in the mountain passes between Foix and Navarre on his way to visit Leonor. The princess issued a series of orders to dispatch men and pay for additional recruits and mules in the mountains in order to clear the passes and roads for Gaston, including one order for 300 men to be sent to help. Gaston’s death in 1472 took place on another journey to see his wife in Navarre; he died en route of natural causes in the Pyrenean town of Roncesvalles.

Overall, Gaston and Leonor worked together with the mutual goal of obtaining the crown of Navarre, throwing the weight of Gaston’s power, wealth, connection, and military forces behind Leonor’s hereditary rights and were willing to fight off opposition from their own family in order to succeed. They worked in partnership, with each partner taking on the most appropriate role; Leonor was responsible for the governance of Navarre, and Gaston supported her militarily and financially. They both worked on diplomatic efforts to achieve their ambitions; Gaston used his position as a powerful French vassal and general to gain support while Leonor negotiated with her Iberian relatives to maintain their rights.

[...] Tragically perhaps, Leonor hardly had a chance to enjoy the position of queen regnant when it finally came her way. Leonor’s death, only a few weeks after her father’s in February 1479, meant that her rule as queen lasted less than a month. Leonor changed her address clause to reflect her altered position as “Queen of Navarre, Princess of Aragon and Sicily, Duchess of Nemours, of Gandia, of Montblanc and Peñafiel, Countess of Bigorre and Ribagorza and Lady of Balaguer.” Ram í rez Vaquero points out that most of these titles were disputed; several were titles that should have come to her as part of her paternal inheritance from her father but in reality would have gone to her half-brother Ferdinand de Aragon. In addition, the French titles that Leonor had held as Gaston’s wife had already been passed to her grandson. It appears that Leonor had enough time to mount a formal coronation, on January 28, 1479, at Tudela, firmly establishing herself as Queen of Navarre, even if only for a brief moment. Moret remarked that “out of all the kings and queens of Navarre she was the one who reigned the shortest, although she may have been the one who desired [the crown] most.”

— Elena Woodacre, "Leonor: Civil War and Sibling Strife", The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics and Partnership, 1274-1512 (Queenship and Power)

#gotta love ruthless ambitious mutually devoted power couples 💅#(they can have a little fratricide. as a treat)#historicwomendaily#Leonor of Navarre#Gaston of Foix#aka the self-declared malewife#Navarre history#Leonor fighting and scheming and waiting for the throne for decades only to finally succeed and then die less than a month later#biggest of Ls honestly#I do wonder what she would have thought about that twist of fate#Was she bitter about the hollow victory of it all?#Or was there nothing but satisfaction that she died as the Queen of Navarre#a position she had fought for for so long#or...both?#(also let's get one loud 'BOO' for Juan the Faithless aka one of the worst historical fathers I have ever read about)#(this is the guy who raised Ferdinand 'I'm going to lock up my own daughter' of Aragon btw. This is where he learned it from)

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is your name Gascon like Gaston from Beauty and the Beast?

...No.

Gascon is a demonym, describing the people of the historical French province of Gascogne (Gascony in English). It's in the southwest of the country, along the border with Spain:

My father's family, and thus my family name, are Gascon - although my full lineage encompasses a much broader range of French regional identities. Still I've gotten used to Anglos having trouble figuring out that my name is French on first glance, since it doesn't look like one of the more common French Louisiana family names like Boudreaux, Landrieu, etc. It's also a useful reference point for my Mediterranean complexion and dark eyes, which are sometimes remarked on by my lovers.

And really, while I can somewhat understand mixing up words in a different language with only a single letter separating them, I don't care for the implication that the people who make that mistake have such a small reference pool for French names/geography that they have to rely on a Disney movie of all things to fill in the blanks. Consider instead

Gaston Leroux, author of Le Fantôme de l'Opéra

a truly ridiculous number of comtes de Foix and vicomtes de Béarn, almost comparable to the number of French kings named Louis

Gaston Chevrolet, racecar driver and founder of the automobile company along with his brothers

Gaston Lagaffe, protagonist of a Franco-Belgian comic strip named for him

Etc.

#Not-so-pointless observation#Odd to be asked about my online handle like this#But then I've seen multiple people mix it up before

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"they understand me [...] better than any man can"

Images text:

"At the end of the 14th century Gaston III, Comte de Foix (1331-1391) wrote a book about hunting called Livre de Chasse, which included a section on how he took care of the greyhounds he used in the hunt. Gaston explains that their kennels should be built of wood and at least a foot off the ground, with a loft where the dog could be cool in the summer and warm in the winter. It should also have fresh straw added to its floor each day and have a door that opens into a sunny yard, so that

the houndes may go withoute to play when them liketh for it is grete likyng for the houndes whan thei may goon in and out at their lust."

A simple translation: "the hounds may go outside to play when they like, for the hounds greatly like it when they can go on, in and out, whenever they desire."

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you try your best, but you don't succeed...

"Death of the Count of Foix (Gaston III Phoebus). f. 126

Gaston Fébus [also spelt Phoebus] (30 April 1331 – 1391) was the eleventh count of Foix (as Gaston III) and viscount of Béarn (as Gaston X) from 1343 until his death.

between c. 1470 and 1472

Jean Froissart (Chroniques, Vol. IV, part 2)

British Library, Harley 4379"

#middle ages#manuscript#medieval france#comte de foix#count of foix#gaston III#its sad to see the poor lad's face...

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Le Trésor”

Photo/Composition-MMIXX

https://chorisar.blog/2019/10/17/tresor-medieval/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Chasse au lapin.

Le livre de chasse de Gaston Fébus, comte de Foix, 1331-1391

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'art du camouflage, f° 114r

Gaston III (comte de Foix ; 1331-1391).

Gaston Phébus, Livre de la chasse. — Gace de la Buigne, Déduits de la chasse.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Guerre entre Girard de Cazaubon et le comte de Foix. Reddition de Roger Bernard III, 1460, Jean Fouquet

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Portrait Of Madame Du Barry”, 1789-1820, by Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun (French painter, 1755 - 1842).

The subject of this elegant portrait, Jeanne Du Barry (1743-1793), was one of the courtesans of the eighteenth century that Élizabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun painted in the course of her long career. What is known of her life reads like a cautionary tale. Jeanne Bécu was born out of wedlock into the servant class of Vaucouleurs, a town on the Meuse river in the province of Champagne near the frontier separating France from the Duchy of Lorraine. The child’s mother, Anne Bécu-Cantigny (1713-1788), was a seamstress, while her father is usually presumed to be Jean Jacques Gomard de Vaubernier (1715-1804), called père or frère Ange, a monk of the tertiary order of St. Francis (Picpus) in whose institution Anne was occasionally employed. With her young daughter, Anne Bécu, travelled to Paris in the company of a financier and supplier to the royal army who had interests in the area, a certain Billard du Monceaux, entrusting them to the care of his mistress, “Mademoiselle Frédéric,” with whom they lived both in the city and in a country house at Courbevoie. When Jeanne was six, her mother married a servant, Nicolas Rançon, who was given employment in a warehouse on the island of Corsica that had recently become a French possession. Over a period of eight years, Jeanne received a sound education in a convent school for indigent or wayward girls run by the nuns of Sainte-Aure not far from the church of Saint Étienne du Mont. She then served for a time as a companion to the widow of a tax concessioner, Madame de Delley de La Garde, one of whose sons became infatuated with her, causing her to be dismissed. She had a brief dalliance with a hairdresser named Lametz, the result of which may have been the birth of a young girl called Betzi. For a time Jeanne apparently made her living as a shop girl under the signboard À la Toilette on the rue Neuve-des-Petits-Champs. Eventually the lovely “Mademoiselle Lange” or “Mademoiselle de Beauvernier,” as she was then alternately calling herself, worked as a prostitute and may even have been employed for a brief spell in the brothel kept by the maquerelle, Marguerite Gourdan or in the gambling den of the so-called “marquise” Dufresnoy. She was ultimately taken up by a notorious sharpster belonging to the minor aristocracy of Gascony, comte Jean Du Barry de Céres (1723-1794), who was known to the Paris police as le Roué (the Rake). He quickly turned his lodgings into a place where he could hire out his “protégée” to men who could pay the exorbitant prices she could garner, among them the Duc de Richelieu and the Treasurer of the royal navy, Maximilien Radix de Sainte-Foix. By the spring of 1768 Jean Du Barry had contrived to present the young woman to Louis XV’s premier valet de chambre, Dominique Lebel, who for years had served his master as a procurer of girls lodged in a house in the town of Versailles, the Parc-aux-Cerfs. Through the intrigues of Richelieu and Lebel, Jeanne was introduced to the monarch, who was immediately smitten with her charm. These famously included an exquisite complexion, a beautiful bosom — as can be seen from the marble bust of her carved by Augustin Pajou, Musée du Louvre—, a profusion of ash-blonde hair, blue eyes that were often half closed and a pronounced lisp, which gave her speech a childlike innocence. Until this time, Louis’s official mistresses had been either of the highest aristocracy or, in the case of Madame de Pompadour – who had recently died at the age of forty-three of physical exhaustion and tuberculosis – of the highest ranks of the moneyed class. Once she had been stealthily married off to Du Barry’s younger brother Guillaume – who was quickly dispensed with – and titled “comtesse Du Barry,” Jeanne was formally presented at Court in the third week of April 1769. She was assigned luxuriously appointed apartments in Versailles and other royal residences and was immediately surrounded by a coterie of courtiers, male and female alike, military officers and state officials. The Comtesse du Barry soon incurred the intense loathing of the royal family (the king’s spinster daughters, his grandson and heir, the Dauphin, and especially the latter’s wife, Marie Antoinette) and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the duc de Choiseul. Madame Du Barry found herself in the crosshairs of much of the Court and the representatives of the underground press, for whom she was easy prey. The comtesse, who was clever beyond her years and quickly assimilated the tastes, manners and conventions of the aristocracy, was installed in great opulence at Versailles, and her official presentation to the royal family took place on 22 April 1769. Considerably less grasping and meddlesome than the Pompadour, she did exercise some influence in the realms of fashion and the arts. The painters Joseph Vernet, Jean Baptiste Greuze, Jean Honoré Fragonard and François Hubert Drouais, the sculptor Augustin Pajou and the architect Claude Nicolas Ledoux all derived considerable benefit from her largesse. Undeniably, the finest work of art she ever owned was Sir Anthony van Dyck’s full-length Portrait of King Charles I of England at the Hunt (Musée du Louvre, Paris), a painting she sold to Louis XVI after her fall from grace. In the area of politics, she finally brought about the banishment from Court of her nemesis, the powerful Choiseul, who was unrelenting in his hostility to her. Through some of her allies — notably Choiseul’s replacement, the duc d’Aiguillon (old Richelieu’s kinsman), the Comptroller General of Finance and head of the fine arts administration, the abbé Terray, and the Chancellor of France and Keeper of the Seals, René Nicolas Maupeou — she may have had an impact on the conduct of affairs of state, but less than her higher-born predecessors had had. That being said, she was profligate and lavished great sums of money provided to her by the royal bankers on herself, her Du Barry relations and the favorites who paid court to her. The king purchased for her the Château de Luciennes (the eighteenth-century spelling of Louveciennes), and she commissioned Ledoux to design and construct an exquisite little neo-classical pavilion for which Jean Honoré Fragonard painted the four-panelled Progress of Love in the Hearts of Young Girls (The Frick Collection, New York). She foolishly rejected these masterpieces and replaced them with a set of more fashionable but rather insipid neo-Greek compositions by Joseph Marie Vien. The four years of her tenure as official mistress of the king were the highpoint of Madame Du Barry’s life. After Louis XV died of smallpox in 1774, Jeanne Du Barry was disgraced and banished from Court. After a period of confinement in a convent, she lived in retirement at Luciennes, where she was visited by new lovers, most prominent among them Hyacinthe Hugues Timoléon de Cossé, duc de Brissac, the governor of Paris. As the Revolution approached, Madame Du Barry remained unswervingly loyal to the monarchy. She eventually came under the scrutiny of agents of the local revolutionary clubs. The reported theft of her jewels in 1791 was the pretext she used to make several crossings to England where French spies noted her close contacts with exiled supporters of the old regime. She even wore morning in London when Louis XVI was guillotined. In early September of 1792, Brissac, whom Louis XVI had appointed commander of his Swiss Guards, was killed by a mob as he and other prisoners were crossing through Versailles; it is said that his head was carried to the château at Louveciennes. Denounced for crimes of aristocracy and treason, the comtesse Du Barry was arrested on September 22, 1793. At first incarcerated in the prison of Sainte-Pélagie, she was later transferred to the Conciergerie. At her trial some of her servants, notably her cook Salanave and her Bengali groom Zamor, betrayed her (J. Baillio, ‘Un portrait de Zamor, page bengalais de Madame Du Barry,’ Gazette des Beaux-Arts, vol. CXLIV, no. 1065, October 2002, pp. 233-242). On receiving the death sentence, the distraught woman revealed the location of many of the valuables she had hidden on her estate. On 8 December 1793—18 Frimaire an II of the revolutionary calendar—Jeanne Du Barry and her Flemish bankers, the Vandenyvers father and two sons, were executed. How Vigée Le Brun originally became acquainted with Madame Du Barry is unknown. It could have been through her brother-in-law, Jean du Barry, whose portrait she had executed when she was only eighteen. Or, more likely, it could have been upon the recommendation of the duc de Brissac, whose portrait “en costume de cérémonie” she had executed in pastel in the early 1780s, a work exhibited at Pahin de la Blancherie’s Salon de la Correspondance in 1781 and 1782. In the dated list of portraits and subject pictures done between 1768 and 1789 that she appended to vol. I of her memoirs, the painter accounts for a number of likenesses of Du Barry: a copy of a portrait of her by another artist done in 1778 (unlocated or unidentified); a portrait done from life in 1781, which is either the half-length in which she is shown wearing a white muslin chemise or peignoir and a straw hat, a work that exists in two more or less well preserved autograph versions (figs. 1 and 2), or the almost knee-length portrait showing the comtesse wearing a creamy white satin dress à l’espagnole holding a wreath of flowers and leaning on a porphyry column, a work completed and signed and dated the following year (fig. 3); and a full-length portrait (1787), which either never existed or has not survived, and one of the aforementioned portraits of her wearing a peignoir. There is no mention however in the lists of the present portrait, which she began at the Château de Louveciennes during at the end of September 1789, leaving it unfinished only weeks before she felt obliged to leave France. She does however refer to it in the text of the Souvenirs: “The third portrait that I did of Mme Dubarri is in my house. I began it around the middle of September 1789. From Louveciennes, we heard incessant cannonades, and I remember the poor woman telling me. ‘If Louis XV were still alive, certainly none of this would be happening.’ I painted the head and sketched out the body and the arms, then I was obliged to make a trip to Paris. I hoped to be able to return to Louveciennes to finish my work, but Berthier and Foulon had just been assassinated [22 July 1789]. I was out of my mind with fear, and I could only think of leaving France. I therefore left this painting half finished. I know not how by chance comte Louis de Narbonne came into possession of it during my absence. Upon my return to France, he returned it and I have just finished it.” Madame Le Brun left Paris with her daughter in October of 1789, the same night that the royal family was forcibly removed by a mob from the Versailles and made to take up residence in Paris at the Palais des Tuileries, a major step in the eradication of the centuries-old monarchs. She settled in Rome and on July 2, 1790, after a financially profitable stay in Naples, she wrote to Madame Du Barry that she was hoping to return to Louveciennes to complete the portrait in October of that year. “I was hoping to stay here only six weeks, but I have so many paintings to do that I am staying six months. That postpones my beloved project for Louveciennes, that of finishing your portrait, but I will come back with pleasure, because there everything is lovely, everything is fine…” This is undoubtedly the unfinished portrait of the comtesse Du Barry which the duc de Rohan Chabot found in the Paris townhouse on the rue de Grenelle, of the murdered duc de Brissac, reporting in a letter to her, “I picked up the three portraits of you which were at his house. I kept one of the smaller ones. It’s the original of the one which shows you wearing a white chemise or a peignoir and a hat with a plume, the second is a copy of the one in which the head is finished, but the clothing is only sketched in. Neither of them is framed” (C. Vatel, Histoire de Madame du Barry d’après ses papiers personnels et les documents des archives publiques, Versailles, 1883, III, pp. 201-202).Here Madame du Barry is shown seated on a bench in a garden next to a tree with an ivy-covered trunk. The skin tones of her face are florid, and there is a beauty spot under her left eye. Her left hand fondles a thick braid of the unpowdered tresses, but the rest of her hair is arranged in curls around her face or falls to her shoulders. The artist has woven a gold bordered transparent veil into this coiffure in the manner of a turban knotted at the top and falling onto her back. Over a filmy long-sleeved shift attached with gold buttons running down the arms to the wrists, she wears a golden ochre gown shot with green reflections which is caught up under her ample bosom with a sash of pink silk tied at the rear into a large bow. In her right hand she holds a nosegay composed of a white lily—a symbol of Madame Du Barry’s royalist convictions—and a pink rose she has just picked from the flowering bush at the lower right of the portrait. Vigée Le Brun returned to Paris after her twelve-year exile from France during the period of the Émigration and took up once again residence in the Hôtel Le Brun on the rue du Gros-Chenet. Sometime after this event, the portrait was restored to her by the comte de Narbonne-Lara, the son of a lady-in-waiting to Louis XV’s daughters, Louise Elisabeth de France, Duchess of Parma and Piacenza (1727-1759) and Madame Adélaïde de France (1732-1801). On December 15, 1802, eleven months after her return from exile, the Prussian composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814) visited with a group of friends the French artist’s studio. Among the many works he noticed were unfinished portraits of Marie Antoinette (possibly a bust-length picture) and the Comtesse Du Barry, the work under discussion. It inspired him with melancholic thoughts: “Melancholic reflections in which I did not expect to indulge myself in the cheerful studio of the genial artist were inspired by the view of two unfinished portraits placed near each other: that of Mme du Barry and that of the unfortunate queen of France. How many thoughts does a similar, rather strange, juxtaposition by Mme Lebrun, not elicit, it seems to me.” (J.F. Reichardt, Vertraute Briefe aus Paris Geschrieben in den Jahren 1802 und 1803 […], A. Laquiante, ed., Paris, 1896, pp. 148-151.) Details of why or precisely when Vigée Le Brun returned to the present portrait and finished it are few. She refers to its completion in her Souvenirs only briefly: "I know not how by chance comte Louis de Narbonne came in possession of it during my absence. Upon my return to France [in 1801], he returned it and I have just finished it." As Vigée Le Brun began writing her celebrated memoirs in the early 1820s—they were published in 1835—one may presume that she resumed work on the painting and completed it in the early to mid-1820s, a dating that accords with the style of much of the drapery and landscape setting. The finished portrait was hung in the second of Vigée Le Brun’s two salons that contained the most important of the paintings she had retained, rooms overlooking the garden of the townhouse she occupied at the end of her long life, the Hôtel du Coq, which was located at 99 rue Saint-Lazare across from the construction site of the locomotive station that later became the Gare Saint-Lazare. A red-chalk copy of the bust by the engraver Alexandre-Vincent Sixdeniers (1795-1846) is today preserved in a private Swiss collection. A patiche of the painting showing Madame Du Barry wearing a green silk dress over a short-sleeved undergarment, which is usually attributed to Vigée Le Brun's niece by marriage, Eugénie Tripier Le Franc, formerly in the collection of the subject’s biographer Charles Vatel, is today in the Musée Lambinet, Versailles. Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, the daughter of a minor painter, Louis Vigée, was born and brought up in Paris. She became a member of the Académie de St-Luc in 1774 and of the French Academy in 1783. She was a highly fashionable portrait painter, patronised particularly by Queen Marie Antoinette. Between 1789 and 1805 she travelled in Europe and visited Russia.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Memoirs of Chevalier d'Eon translated by Antonia White

So lets talk about The Memoirs of Chevalier d'Eon translated by Antonia White. This book is not a translation of d’Eon’s memoirs as you may have assumed from the title. If you want to read a translation of her (uncompleted) memoirs you’re looking for The Maiden of Tonnerre translated by Roland A. Champagne, Nina Ekstein, and Gary Kates. This is a translation of the book Memoires du Chevalier d'Éon by Frédéric Gaillardet.

I’ve alluded to this book in the past but I thought I should write a post on it so people know whats up.

So basically Frédéric Gaillardet was from Tonnerre, the same town d’Eon was from. In 1835 Gaillardet obtained form a family member of d’Eon “manuscripts, printed matter and various papers” as well as her baptismal certificate, death certificate, and papers relating to her autopsy. He also got permission to search the archives of foreign affairs where he found papers relating to d’Eon.

But something surprised him about d’Eon’s papers; the complete lack of evidence that d’Eon had ever sex with, well, anyone. He just couldn’t believe that d’Eon had never had sex, “a fault explained by my youth and the kind of literature in which I had tried myself”, Gaillardet explains “I was twenty-five years old ... I dreamed only of complicated adventures, tragic loves and dark secrets.”

Gaillardet let his imagination get the better of him and became convinced that d’Eon must have had a life full of secret love affairs, and so he decided to add a fictional part to his book consisting of all these sexual encounters he imagined d’Eon must have had. This resulted in a book that “consisted of an authentic part and a romantic part.” And so the mix of fact and fiction that was Memoires du Chevalier d'Éon was published in 1836. Despite the fictional additions, “or perhaps because of it, it sold a lot”.

Gaillardet seems to have believed that it was clear what parts of his book were fact and which were fiction. But then “an unexpected incident” occurred that showed Gaillardet that he had “relied too much on the perspicacity of certain readers.” In 1861 another book about d’Eon Un Hermaphrodite by Louis Jourdan was published. “This publication piqued my curiosity little, because its title was in my eyes a label of pure fantasy” recalls Gaillardet, “having met one day in the offices of the Press with M. Jourdan, whom I had not had the honour to know until then, I approached him, named myself and said to him “I've learned that you have published a book in which you speak of the Chevalier d’Eon. As I myself published two volumes on this character twenty-five years ago, I would be curious to read yours. Send him to me.”

Jourdan surprised and embarrassed responded "I did not know you had returned from the United States, that is why I did not send you my volume, but I will send it to you, if you will give me your address.”

Gaillardet replied that “he could simply have the book dropped off for me at the Press, where I came every day.”

“A week, a month passed, and I received nothing. I said to myself then that my colleague had probably recoiled from an expense of three francs, and I promised myself to buy what he did not believe he should offer me. But I was obliged by my health to leave Paris, and I forgot M. Jourdan and his book.”

However later while in a reading room Gaillardet recalled Un Hermaphrodite and asked for a copy. “I was at first a little surprised, even a little piqued, in my self-esteem, not to see the slightest allusion to the Memoirs published by me and containing so many documents on the same subject.” Recalls Gaillardet “But I consoled myself, thinking that I was certainly going to be taught completely new things about a time that they said to have been studied with a magnifying glass”.

But Gaillardet was surprised to find almost a complete reproduction of his own work “not only in substance, but also in form, not only in their authentic part, but also and especially in their fictitious part.” In fact is was above all what Gaillardet had invented that “seduced the author” of Un Hermaphrodite which reproduced the numerous fictional love affairs from Memoires du Chevalier d'Eon including a love affair with a completely fictitious character of Gaillardet creation.

Upset by this blatant plagiarism Gaillardet determined to do two things; the first was to demand justice for this blatant disregard of his intellectual property. The second was to publish a new edition of his Memoirs on d’Eon this time sticking to the “the strict historical truth”.

Gaillardet brought civil action against Jourdan. In response to this he received a letter from Jourdan containing an unlikely story. A young man had come to him needing money. He advised the young man to research the life of the Chevalière d'Eon, promising to “review his work, correct it and sign it, so that the book could find a publisher.” The young man brought to him “a long manuscript, written entirely in his hand, assuring me that this work, as to form, was his own, that he had done research, etc., etc.”

Jourdan begged Gaillardet for forgiveness and requested that they sort the matter out of court. Gaillardet was at first unconvinced by this story but then the young man who wrote the book stepped forward to take responsibility for his mistake. The young man explained that in taking Gaillardet’s work as historical fact he believed that it was public domain and thus fine for him to reproduce in his own book. Gaillardet ended up forgiving Jourdan and the young man for the whole misunderstanding.

In working on his new book Gaillardet “with a magnifying glass in his hand” as the author of Un Hermaphrodite would say, came to a new conclusion: d’Eon was a virgin.

Gaillardet goes on to cite some of the evidence which lead him to this conclusion which I think is interesting enough to repeat here as it is not only evidence of d’Eon’s virginity but also of her asexuality.

The evidence is “a series of letters from the Marquis de l'Hospital, enamelled with Gallic jokes about the scandalous chastity of his embassy secretary [d’Eon]” and “the repeated confessions” of d’Eon herself “who wrote, in 1763,” to her friend Sainte-Foix that she "has always lived without horses, without a cabriolet, without a dog, without a cat, without a parrot and without a mistress".

And in 1771 d’Eon wrote to the Comte de Broglie:

I am mortified enough to still be as nature made me, and that the calm of my natural temperament never having brought me to pleasures, this resulted in the innocence of my friends to imagine, both in France and Russia and England, I was the female gender; the malice of my enemies has fortified everything.

It’s interesting to note that d’Eon denies being a woman in this letter considering she was telling people as early as 1772 that she was a woman, and evidence suggests is was most likely her that started the rumours in the first place. However this may perhaps be part of her ruse, she may not have wanted to seem too keen to admit she was a woman, as this would not suit the narrative she had created.

Gaillardet ends up publishing his new book Mémoires Sur La Chevalière d'Éon in 1866 this one based strictly on historical fact.

Why the English translation was based on the first (and factually inaccurate) edition I can not tell you. But be aware that The Memoirs of Chevalier d'Eon are not actually her memoirs.

I haven’t actually read either French editions of this book (beyond google translating a few bits and pieces). And I haven’t read the English translation cover to cover, because honestly I have no desire to read a semi-erotic fanfic about d’Eon fucking seemingly every woman she met. However the events talked about in this post are covered by Gaillardet himself in the preface and epilogue of Mémoires Sur La Chevalière d'Éon, as well as in the introduction of the English translation.

All of the quotes in this post are from Mémoires Sur La Chevalière d'Éon and were translated with google translate.

#chevalière d'eon#frédéric gaillardet#I mean this post is more about gaillardet than d’eon but its a interesting story#and its good to know so you don’t get mislead#honestly thank god he admitted he made it all up#cause I swear if he hadn't have we would still be dealing with people today citing his book

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

so there’s nothing known about charlotte ever receiving any other important proposals so somehow i’m just imagining charlotte chilling at the ( slightly boring ) court of jeanne de valois, living her best life sneaking out and having fun in nearby villages

and then fucking pope alexander has to come in, annul her mistress’ marriage to the french king, and then gets chosen over one of the comte de foix’s daughters to marry the pope’s son like

idk but i think she was initially rather displeased with the pope.

#she had a good life and then pope alexander meddled skaljdfsh#what do you mean history can't be rewritten? ( ooc. )

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Year of the Dog - French Hounds “(1) Only three old Saintongeois hounds survived the French Revolution, two dogs and a bitch. Count Joseph de Carayon-Latour in the mid-19th century crossed the last of the old Hound of Saintonge with a few of the remaining old-type Grand Bleu de Gascogne. The hounds that were white with black ticking were retained and later given the name Gascon Saintongeois.

In the middle of the 20th century, hunters in the southwest of France selected smaller dogs from litters of Grand Gascon Saintongeois for hunting hare and other small game. These became the Petit Gascon Saintongeois.

The Grand Gascon Saintongeois is used for hunting big game including wild boar, roe deer and sometimes gray wolf, usually in a pack. The Petit Gascon Saintongeois is a versatile hunter, usually used on hare and rabbit, but it can also be used for big game.

(2) The Porcelaine gets its name from its shiny coat, said to make it resemble a porcelain statuette. The Porcelaine is thought to be a descendant of the English Harrier, some of the smaller Laufhounds of Switzerland, and the now-extinct Montaimboeuf. There have been records of the breed in France since 1845 and in Switzerland since 1880. The breed actually disappeared after the French Revolution (1789–99) but has been reconstructed. Breeders in the UK are attempting to have the Porcelaine accepted as a recognized breed.

(3) The Grand Bleu de Gascogne may descend from dogs left by Phoenician traders, its ancestors were contemporaries with the St Hubert Hound and English Southern Hound, Comte de Foix kept a pack in the 14th century and Henry IV of France kept a pack in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

The Grand Bleu de Gascogne is noted for its focus on the hunt, as well as a good nose and distinctive, sonorous, deep howl, the breed is "instinctively a pack hound". In the past, it was used to hunt deer, wolves, and boar; in the field it is considered a rather slow and ponderous worker and today is predominantly used to hunt hares.

The Grand Bleu de Gascogne has had a significant influence on the development of several breeds of scent hounds. After the French Revolution, it was used to revitalise the old Saintongeois, creating the Gascon Saintongeois, and the Bluetick Coonhound is considered a direct descendant of the Grand Bleu. The Grand Bleu de Gascogne was used by Sir John Buchanan-Jardine in the development of the Dumfriesshire Hound; in Britain, any native hounds with blue marbled coats are still referred to as 'Frenchies' after this breed.”

On Redbubble!

You can support me on Patreon! Half the funds will go to a local no-kill shelter!

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WOMEN’S HISTORY † LEONOR I.a NAFARROAKOA (2 February 1426 – 12 February 1479)

Leonor I.a Nafarroakoa was the youngest of the four children of Joan II d’Aragó and Zuria I.a Nafarroakoa. In 1440, her mother died and the throne of Navarre should have passed to Leonor’s older brother, Karlos, but instead Joan kept on ruling Navarre and excluded Karlos from power. At some point (either 1436 or 1441), Leonor married Gaston IV, comte de Foix and vicomte de Béarn, son of Jehan de Foix-Grailly and Jehanne d’Albret, daughter of the Constable Charles d’Albret who had died at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Leonor and Gaston had ten children. Meanwhile, in 1451, civil war broke out between Leonor’s father and brother. Karlos was taken prisoner after the Battle of Aybar in 1452 and Joan tried to disinherit him in favor of Leonor. Instead, Karlos spent much of his time abroad in Italy at the court of his uncle, Alfons V d’Aragó. In 1455, Joan formally disinherited Karlos and as well as his elder daughter, Zuria, and proclaimed that Leonor was his lawful heir and would act as governor of the kingdom in his absence. Afterwards, Leonor traveled to Navarre and took up the role of governor. Karlos died in 1461 and the following year, Joan placed Zuria into Leonor’s custody. Zuria died a year later and was rumored to have been poisoned. Despite her loyalty to her father, Joan deposed her as governor in 1468 in the midst of civil war in Aragon and ordered the assassination of her advisor, Nicolas de Etchabarri. Joan’s actions did nothing to improve the civil war and in 1471, he was forced to reinstate Leonor as governor. His actions may have been motivated by the fact that Gaston was French and Joan was not on good terms with the French king, Louis XI. Around the same time, Leonor’s eldest son, Gaston, Vianako printzea, died in a tournament accident and her husband died while leading an army to her rescue. Joan finally died 20 January 1479. Leonor was crowned queen 28 January 1479, but died less than a month later on 12 February at the age of 53. She was succeeded as the ruler of Navarre by her grandson, François Fébus, the son of her eldest son Gaston by Madeleine de France. Leonor’s third surviving son, Jean de Foix, vicomte de Narbonne, married Marie d’Orléans, younger sister of Louis XII de France, and was the father of Germaine de Foix, second wife of Fernando II de Aragón. Meanwhile, Leonor’s third daughter, Marguerite de Foix, married Frañsez II, dug Breizh, and was, thus, the mother of Anna Breizh, the twice queen of France. Finally, her fourth daughter, Catherine de Foix, was the grandmother of Anna Jagellonica, wife of Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I, the second son of Philipp the Handsome and Juana I de Castilla.

#eleanor of navarre#house of trastamara#spanish history#french history#european history#women's history#history#women's history graphics#nanshe's graphics#medieval

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juanna la locad childhood

JUANNA LA LOCAD CHILDHOOD SERIES

The foreign candidate is Louis of Anjou (☁377), contested King of Naples, OTL husband of Joans's half-sister. It would strengthen the claim of Joana (but Martin, his son and grandson are still senior to Urgell in the genealogy of the house) and gave her a much-needed base of power. Having said that, if Joana and Mathew, with uncanny political wisdom, managed to play the Catalan élites in their favour but Mathew died childless as OTL, the logical local candidate is James of Urgell (☁380), heir to the most senior noble of Catalonia and male scion of the house of Barcelona. This contrasts with the other players of the "game of thrones" who were linked to powerful foreign royal families. A scion of a junior line of the Foix family part of the Catalan aristocracy for some generations, both his mother and his grandmother came from undistinguished families and his only cousins, the Count of Pallars and the Viscount of Cabrera, actually fought against him in 1396. Another disadvantage for Mathew and Joana : the relatively low-level genealogical connections of the Count of Foix. That did not stop Mathew of Foix to invade Catalonia in 1396 OTL, but he was easily repelled by Martin, as he did not have any local support. Finally, the queen was still in childbearing age (she was pregnant when John Ist died), so why bother to change the rules (and convince the troublesome corts to go along) ?įor all these reasons, I found it very unlikely John Ist would ever change the rules of inheritance in favour of his first marriage's daughter. He even titled his sons "Dauphin of Girona" ! Furthermore, the salic system of inheritance (as illustrated by the french laws of succession) was already installed in the crown Aragon by the will of James Ist - even if the kingdom of Aragon itself had known a female transmission. John Ist, both by personal inclination and by his second wife's influence, was very close to France. How might Aragon develop otherwise? Who might she remarry if Mathieu still leaves her without children (let's assume the problem was his, not hers) so in 1398 she's a 23 year-old widow who's also a queen of Aragón, Valencia, Majorca, Sardinia and Corsica, Countess of Barcelona. Now, what if Juan had somehow passed a law that stipulated his daughters could succeed in lack of a male heir? Or Juana had been successful in claiming the crown on her father's death in 1395. Plus, Mathieu died in '98, but Juana never remarried, and even in her own lifetime, in spite of being the senior Aragonese claimant, her younger half-sister, Yolanda, claimed the Aragonese crown. Still OTL, Juana had no children from her marriage to Mathieu, Comte de Foix, but when her father died in '95, she'd only been married to Mathieu for two years. However, Martin was having some issues with the Sicilian nobility and as a result, his wife, Maria de Luna, had to secure the Aragonese realm until he could arrive. OTL, when her father died without sons, the Aragonese crown passed to his brother, King Martin of Sicily. The Institute is continually accepting new book and edition proposals.No, not Juana la Loca, daughter of Fernando II of Aragon, but the daughter of King Juan I of Aragon.

JUANNA LA LOCAD CHILDHOOD SERIES

Reference works are published in the series RMS. Significant collections of papers appear in MISC. Published treatises include the works of influential writers from Guido of Arezzo to Jean Philippe Rameau. Significant research findings resulting from the edition-making efforts are published in the series MSD. (See CMM for sacred and secular music and CEKM for keyboard music). The scholarly editions include the complete works of major composers who lived up until the seventeenth century, composers such as Machaut, La Rue, Dufay, Willaert, Clemens, Rore, Compère, Crecquillon, Romero, and others. The publications of the Institute are wide-ranging and comprise scholarly editions, books, and treatises. Since its founding, the Institute has published more than 650 scholarly volumes including the yearbook Musica Disciplina. The publications of the Institute are used by scholars and performers alike and constitute a major core collection of early music and theoretical writings on music. Founded by Armen Carapetyan in 1946, AIM supports interest in Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque music.

0 notes

Text

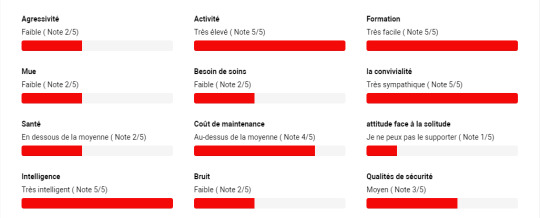

Dressage de chiens Braque de Weimar à Sanary sur mer dans le Var 83

10 leçons pour éduquer et dresser son Braque de Weimar facilement à Toulon, La Ciotat, La Seyne sur mer, Ollioules. Educateur canin, dresseur de chiens & comportementaliste canin à Saint-Cyr sur mer. Tarifs dressage chiens à Toulon 83

Prendre rendez-vous 06 56 72 29 85

Adopter et vivre avec un Braque de Weimar. Histoire, éducation, santé et comportement

Histoire de la race Braque de Weimar

Weimaraner, ou Weimar Hound, est un représentant très rare dans une cohorte de chiens de chasse. Ce chien aristocratique remonte vraisemblablement au Moyen Âge, bien que les normes de race d'aujourd'hui ne se soient développées qu'au tournant des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles.

Le Braque de Weimar appartient au groupe des héritiers de la Bracken européenne (ou continentale) - des chiens d'arrêt à poil court, qui sont depuis longtemps communs sur le continent européen et ont des caractéristiques similaires à la fois extérieures et de travail. Parmi ses proches parents, ce chien se distingue nettement par sa couleur grise originale aux teintes spectaculaires, qui rend populaire la version de sa relation de longue date avec les chiens dits de Saint-Louis (Chiens gris de St-Loi), un dont on trouve la description dans d'anciennes sources manuscrites de l'époque légendaire des Croisades. . Des chroniques remontant au XIIIe siècle racontent qu'à la cour du roi de France Louis IX, dit Saint Louis, des chiens gris argentés sont apparus en 1254, après son retour dans son pays natal d'un autre voyage en Orient.

Dans les sources littéraires médiévales, il y a des références au fait que ces chiens étaient originaires de Tartarie - c'est ainsi que les pays de langue latine appelaient le territoire qui s'étendait des frontières de l'Asie centrale à ses limites septentrionales. Peut-être que les animaux ont été présentés à Louis par l'un des dirigeants asiatiques, avec qui le monarque français a décidé d'établir des liens en Palestine. La description la plus détaillée est contenue dans le Livre de la chasse, l'un des meilleurs traités médiévaux sur ce divertissement des rois et des aristocrates. Son auteur est le comte Gaston de Foix, l'un des commandants de la guerre de Cent Ans et un chasseur passionné.

À la fin du XIVe siècle, les chiens gris sont devenus très populaires parmi la noblesse française, car ils ont démontré d'excellentes qualités dans la chasse aux gros animaux - cerf, sanglier, ours. Plus tard, les chiens ont également montré des capacités remarquables pour chasser les renards, les lapins et aller chercher des oiseaux. À la suite de l'aristocratie française, cette merveilleuse race a été emportée par des personnes couronnées d'autres pays de l'Europe féodale, et après elles leurs vassaux. Sur les tapisseries médiévales et les peintures représentant des scènes de chasse, vous pouvez voir des meutes de chiens gris - aussi nobles que leurs propriétaires titrés. Ces animaux sont également représentés sur les toiles des maîtres du XVIIe siècle, par exemple dans les peintures du peintre flamand Anthony van Dyck.

Parmi les géniteurs possibles du Braque de Weimar figurent également les chiens de Saint-Hubert, élevés au début du Moyen Âge dans l'abbaye de Saint-Hubert (Belgique). Les animaux de cette race, aujourd'hui disparue, sont considérés comme les ancêtres de nombreux chiens modernes. Ils avaient une couleur différente, parmi laquelle il y avait aussi du gris.

En tant que race distincte, le Braque de Weimar a commencé à se former au début du 19ème siècle. Selon des informations non confirmées, le duc de Weimar Karl August a été l'initiateur de sa création. Selon la légende, dans ses possessions, Saxe-Weimar, à l'est de l'Allemagne moderne, le duc était engagé dans l'élevage d'une race universelle de chiens - robustes, rapides et possédant également les qualités d'un chien de compagnie. Soit dit en passant, dans ces endroits, le chien est généralement appelé le "Silver Ghost". Il a reçu un tel nom en raison de sa couleur, coulée en argent, de sa capacité à se faufiler rapidement et silencieusement dans les champs, en restant invisible pour les proies.

De nombreux cynologues modernes, reconnaissant que la race a été élevée dans les environs de Weimar, pensent que le grand-duc de Weimar n'a rien à voir avec son origine, et la légende de la relation du Braque de Weimar avec les chiens gris de Saint-Louis a commencé à être popularisé par les amateurs de la race à la fin du 19e siècle pour sa reconnaissance en tant que race distincte et indépendante. Le fait est que pendant longtemps le braque de Weimar a été considéré comme une variété grise du chien courant allemand à poil court ou un croisement entre de grands chiens allemands et des braques anglais. Apparemment, ces déclarations étaient justifiées, puisque lors d'une exposition à Berlin en 1880, ces chiens ont été classés comme métis, sans leur trouver de traits de race originaux. Selon certains rapports, le Burgos Hound, Hugenhund, Schweishund ont été impliqués dans d'autres activités d'élevage. travaux prévus, ainsi que de nombreuses publications d'histoires fascinantes sur l'ancienne origine noble de la race et sa relation avec les chiens royaux français ont fait leur travail, et en 1896, une commission de délégués de diverses sociétés de chasse allemandes a finalement nommé le Braque de Weimar une race indépendante. À ce jour, il est reconnu par toutes les organisations cynologiques éminentes.

En 1897, le club de chasse allemand Weimaraner a été fondé et pendant longtemps, cette race a été une sorte de privilège protégé au sein de l'aristocratie allemande. Au départ, seuls les membres du Club étaient autorisés à acheter un chien. Et s'il était extrêmement difficile d'acheter un Braque de Weimar même dans son pays natal, alors en dehors de l'Allemagne, c'était généralement impossible. Dans les années 20 du siècle dernier, l'intérêt pour les chiens gris de l'Ancien Monde s'est manifesté aux États-Unis, mais les premiers individus envoyés à l'étranger étaient auparavant stérilisés, ce qui rendait impossible leur élevage en Amérique. En 1929, le Club a accepté le premier étranger dans ses rangs - l'Américain Howard Knight, qui a réussi à convaincre ses collègues allemands de vendre plusieurs chiens reproducteurs pour l'élevage dans le Nouveau Monde. En 1941, il crée le Weimaraner Club of the USA et en devient le président. Dans les années 1950, les Weimaraners ont acquis une popularité incroyable, devenant les animaux de compagnie de personnalités telles que le président Eisenhower et la star de cinéma Grace Kelly. Plus tard, un intérêt public supplémentaire pour eux a été alimenté par le photographe et artiste William Wegman, lui-même, soit dit en passant, qui est devenu mondialement célèbre grâce à ses images réussies de ces chiens.

L'engouement de masse pour les braques de Weimar - tant aux États-Unis qu'en Europe - a conduit au fait qu'aujourd'hui ils sont de plus en plus considérés comme des chiens de compagnie, des animaux de compagnie, des participants à des expositions et des championnats prestigieux. Dans le même temps, les qualités de chasse de beaucoup d'entre eux sont très ordinaires. Cependant, un bon chien de travail peut être trouvé. Ils représentent principalement les lignées allemandes et américaines, puisqu'en Allemagne et aux USA les éleveurs privilégient encore les qualités de travail de l'animal.

Il n'y a pas si longtemps, certains éleveurs européens et leurs homologues américains se sont lancés dans l'élevage de Braques de Weimar bleus. Ces chiens se distinguent par leur couleur de pelage gris bleuté d'origine. Aujourd'hui, ils sont élevés principalement comme chiens de compagnie, bien que les qualités de travail des pointeurs bleus soient identiques aux capacités exceptionnelles de leurs homologues gris. En 2009, aux États-Unis, des passionnés ont créé un club spécialisé, et depuis lors, à dessein, mais jusqu'à présent sans succès, ils ont cherché à faire reconnaître les Braques de Weimar bleus et à leur donner le statut de race indépendante.

Apparences du Braque de Weimar

Le Braque de Weimar est un chien assez grand de carrure athlétique, musclé, franchement musclé. Chez les mâles, la hauteur au garrot peut aller de 59 à 70 cm, poids - de 30 à 40 kg. Les femelles, en règle générale, sont plus petites: leur taille est de 57 à 65 cm, leur poids est de 25 à 35 kg. Selon la norme, les limites extrêmes ne sont pas souhaitables.

Tête

La tête, vue de dessus, ayant un contour en forme de coin, est proportionnelle au corps. Le crâne est légèrement convexe, pas large, la protubérance occipitale est faiblement développée. Le front est divisé par un sillon ; lorsque le chien est tendu, la région frontale est couverte de plis. La ligne de transition du front au museau est lisse, à peine marquée. Le nez est droit, avec une bosse miniature au niveau du lobe. Le lobe lui-même, dépassant au-dessus de la mâchoire inférieure, est grand. Il est peint dans une couleur chair foncée, virant progressivement au gris plus près de l'ar��te du nez. Les lèvres sont retroussées, la supérieure recouvre la inférieure et pend un peu, formant de petits plis aux commissures de la bouche. Les bords des lèvres, le ciel, les gencives sont d'une couleur chair rosée unie.

Mâchoires et dents

Les mâchoires avec un ensemble complet de dents semblent impressionnantes, démontrant clairement la capacité du Braque de Weimar à tenir un gibier de taille décente lors de la récupération. Les canines supérieures et inférieures se rejoignent solidement en ciseaux. Les pommettes musclées et bien définies sont clairement exprimées.

Yeux

Arrondi, de taille moyenne, placé légèrement obliquement. Leurs coins extérieurs s'élèvent légèrement plus près des oreilles. La couleur des yeux des chiots est bleu azur, chez les chiens adultes - ambre, d'intensité et de tonalité variables: du clair au foncé. L'expression des yeux trahit l'intelligence et l'attention. Les paupières sont bien ajustées contre le globe oculaire, leur couleur peut être chair ou correspondre au ton du pelage.

Oreilles

Grandes, larges, arrondies aux extrémités et tombantes exactement aux commissures de la bouche. Réglez hautes. Chez un chien, qui est alerté par quelque chose, les oreilles se dressent à la base et se tournent vers l'avant.

Queue

Une queue forte et épaissie à la base est placée assez basse, ce qui n'est pas caractéristique de la plupart des races apparentées au Braque de Weimar. Elle est densément couverte de poils et se rétrécit vers la pointe. Lorsque le chien est détendu et paisible, il la maintient abaissée et, lorsqu'il est alerte, la soulève à une position horizontale ou plus élevée.

Le pelage

La longueur du pelage définit deux variétés de race : poil court et poil long. Le premier se caractérise par une laine courte, mais pas autant que dans la plupart des races identiques, très épaisse, dure, lisse. Le sous-poil est très clairsemé voire inexistant.

Le Braque de Weimar à poil long est recouvert d'un pelage soyeux assez long, avec ou sans sous-poil. Le pelage peut être droit ou légèrement bouclé. Sur les côtés, sa longueur est de 3 à 5 cm, les poils de la partie inférieure du cou, du devant de la poitrine et de l'abdomen sont légèrement plus longs. Les membres sont décorés de franges et de "pantalons", la queue - de "franges". Des poils longs et fluides sont présents à la base des oreilles, des poils légers et soyeux bordant leurs pointes.

Couleur

La norme autorise trois variations dans la couleur du Braque de Weimar : gris argenté, gris clair, gris foncé (souris). Ils peuvent avoir des nuances claires, par exemple, le cuivre, montrer un subtil brunâtre. Le pelage sur la tête et les oreilles est généralement légèrement plus clair que sur le reste du corps. Des marques blanches miniatures sur la poitrine et les orteils sont acceptables. La présence d'autres taches, marques de bronzage est considérée comme un inconvénient. Certains individus peuvent avoir une bande sombre, "ceinture", le long de la colonne vertébrale. En couleur, elle contraste avec la couleur dominante de l'animal. Ces chiens ne sont utilisés dans l'élevage que s'ils ont des qualités de chasse exceptionnelles.

Personnalité du Braque de Weimar

Les braques de Weimar sont des chiens énergiques, joueurs et amicaux. Ils sont dévoués de manière désintéressée à la famille dans laquelle ils vivent et ont besoin d'un contact constant avec une personne. Garder ces animaux dans un chenil, comme les autres chiens de chasse, ne devrait pas l'être, car cela les fait souffrir. Les braques de Weimar endurent également la solitude à la maison et la compagnie d'un autre animal ne les soulage pas du désir d'être proche du propriétaire. Il convient de noter qu'un chien laissé à lui-même pendant longtemps peut paniquer, «casser» les meubles de l'appartement et même se blesser en tentant de s'échapper de la maison. Inquiet, le Braque de Weimar se met à aboyer, gémir, hurler et même creuser. Le chien ne se calmera que lorsque le propriétaire apparaîtra sur le seuil. Ces animaux de compagnie adorent suivre leurs propriétaires bien-aimés, adorent s'asseoir à leurs pieds et avoir des «conversations» avec eux, ce à quoi ils sont très enclins. Le Braque de Weimar est un chien assez équilibré. Il se méfie des étrangers, mais ne fait pas preuve d'agressivité s'il est sûr que ses maîtres ne sont pas en danger. En raison de sa méfiance envers les étrangers, de son attention, de son esprit vif, de sa capacité à aboyer à tous les bruits et bruissements suspects à l'extérieur des portes, le chien peut devenir un bon gardien, mais le devoir de garde n'est clairement pas sa vocation.

Avec les enfants, surtout les plus âgés, ces chiens établissent des relations amicales et partenariales. Ils sont tolérants envers les enfants, mais, après avoir commencé un jeu avec ceux-ci, ils peuvent les blesser accidentellement.

Les braques de Weimar sont amicaux avec les autres chiens, surtout s'ils ont grandi à côté d'eux, mais ils ont rarement de bonnes relations avec les chats. Si ce chien est toujours capable de supporter l'animal de compagnie du propriétaire vivant avec lui dans la même maison, alors le représentant de la tribu des chats qui a erré imprudemment sur son territoire ne sera certainement pas accueilli. En fait, tous les petits animaux, ainsi que les oiseaux, éveillent un instinct de chasse indomptable chez le Braque de Weimar, devenant ses victimes potentielles.

Pendant la traque, les Braque de Weimar se manifestent selon leur tempérament inné et leurs qualités personnelles. Il existe des chiens de chasse extrêmement obéissants, mais très souvent, il y a des individus complètement «imprudents» qui deviennent instantanément incontrôlables pendant le travail.

Caractéristiques du Braque de Weimar

Éducation et formation du Braque de Weimar

Le Braque de Weimar est un chien extrêmement intelligent, attentif et compréhensif. Il se prête parfaitement à l'entraînement, mais, étant de mauvaise humeur, il peut faire preuve d'égarement et d'entêtement. Compte tenu de ces traits de caractère, le propriétaire doit faire preuve de fermeté et de patience dans l'élevage de l'animal. Il est nécessaire de former un animal de compagnie à l'obéissance dès son plus jeune âge, mais si l'autoritarisme dans l'éducation est acceptable, les méthodes qui incluent des cris grossiers et l'utilisation de la force physique comme punition doivent être exclues. La brutalité du propriétaire conduira au fait que le chien deviendra méfiant, les commandes seront exécutées de manière incertaine, avec prudence. Il sera très difficile de regagner la confiance du chien. Mais les friandises et les éloges stimuleront le Braque de Weimar à montrer ses meilleures qualités.

Lorsqu'il élève un chien acquis pour la chasse, le propriétaire doit trouver un terrain d'entente, car son obéissance inconditionnelle et son désir de plaire peuvent priver le chien de l'initiative dont il a besoin pendant le travail.

Santé et maladie du Braque de Weimar

Les Braques de Weimar forts et robustes se distinguent par une excellente santé, mais la prédisposition héréditaire à certaines maladies peut être un danger potentiel pour eux. Le tractus gastro-intestinal est à risque chez ces animaux, et une maladie comme le volvulus, caractéristique des chiens à poitrine profonde, peut leur être fatale. Après avoir remarqué les premiers signes d'indigestion chez votre animal, vous devez immédiatement contacter un vétérinaire qui lui prescrira un aliment diététique spécial. Habituellement, dans ces cas, il est recommandé au chien de se nourrir plusieurs fois par jour en petites portions. Pour éviter les volvulus, les experts conseillent de placer les plats contenant de la nourriture pour chiens sur une surface surélevée. Cela empêchera l'ingestion rapide de nourriture et l'entrée d'air dans l'estomac.

Les braques de Weimar sont sujets aux dermatoses et la maladie de von Willebrand, un trouble héréditaire de la coagulation sanguine, peut également les menacer. Ces chiens peuvent aussi avoir des problèmes ophtalmiques : atrophie cornéenne, torsion de la paupière, distichiasis - apparition d'une rangée supplémentaire de cils. Dans 24% des cas de décès prématuré d'un chien, le cancer en est la cause, principalement fibrosarcome, mastocytome, mélanome. Les braques de Weimar ont également une prédisposition à la dysplasie de la hanche et du coude.

Certains animaux de compagnie souffrent de troubles obsessionnels compulsifs - éprouvant de l'anxiété, les animaux commencent de temps en temps à sucer la literie et les couvertures.

Eleveurs de Braque de Weimar

https://www.uncompagnon.fr/fiche/4794/elevage-de-braque-de-weimar.html

https://www.domaineduneply.com/presentation?locale=fr

Standard du Braque de Weimar fiche FCI N° 99

Trouver un éducateur canin pour le Braque de Weimar près de chez vous

Nos Tarifs :

Tarifs éducation canine

Tarifs école du chiot

Tarifs pension canine

Tarifs Taxi animalier courtes distances

0 notes