#communalising

Text

J.5.1 What is community unionism?

Community unionism is our term for the process of creating participatory communities (called “communes” in classical anarchism) within the current society in order to transform it.

Basically, a community union is the creation of interested members of a community who decide to form an organisation to fight against injustice and improvements locally. It is a forum by which inhabitants can raise issues that affect themselves and others and provide a means of solving these problems. As such, it is a means of directly involving local people in the life of their own communities and collectively solving the problems facing them as both individuals and as part of a wider society. In this way, local people take part in deciding what effects them and their community and create a self-managed “dual power” to the local and national state. They also, by taking part in self-managed community assemblies, develop their ability to participate and manage their own affairs, so showing that the state is unnecessary and harmful to their interests. Politics, therefore, is not separated into a specialised activity that only certain people do (i.e. politicians). Instead, it becomes communalised and part of everyday life and in the hands of all.

As would be imagined, like the participatory communities that would exist in an anarchist society (see section I.5), the community union would be based upon a mass assembly of its members. Here would be discussed the issues that effect the membership and how to solve them. Thus issues like rent increases, school closures, rising cost of living, taxation, cuts and state-imposed “reforms” to the nature and quality of public services, utilities and resources, repressive laws and so on could be debated and action taken to combat them. Like the communes of a future anarchy, these community unions would be confederated with other unions in different areas in order to co-ordinate joint activity and solve common problems. These confederations would be based upon self-management, mandated and recallable delegates and the creation of administrative action committees to see that the memberships decisions are carried out.

The community union could also raise funds for strikes and other social protests, organise pickets, boycotts and generally aid others in struggle. By organising their own forms of direct action (such as tax and rent strikes, environmental protests and so on) they can weaken the state while building an self-managed infrastructure of co-operatives to replace the useful functions the state or capitalist firms currently provide. So, in addition to organising resistance to the state and capitalist firms, these community unions could play an important role in creating an alternative economy within capitalism. For example, such unions could have a mutual bank or credit union associated with them which could allow funds to be gathered for the creation of self-managed co-operatives and social services and centres. In this way a communalised co-operative sector could develop, along with a communal confederation of community unions and their co-operative banks.

Such community unions have been formed in many different countries in recent years to fight against numerous attacks on the working class. In the late 1980s and early 1990s groups were created in neighbourhoods across Britain to organise non-payment of the Conservative government’s Community Charge (popularly known as the poll tax, this tax was independent on income and was based on the electoral register). Federations of these groups were created to co-ordinate the struggle and pull resources and, in the end, ensured that the government withdrew the hated tax and helped push Thatcher out of government. In Ireland, similar groups were formed to defeat the privatisation of the water industry by a similar non-payment campaign in the mid-1990s.

However, few of these groups have been taken as part of a wider strategy to empower the local community but the few that have indicate the potential of such a strategy. This potential can be seen from two examples of libertarian community organising in Europe, one in Italy and another in Spain, while the neighbourhood assemblies in Argentina show that such popular self-government can and does develop spontaneously in struggle.

In Southern Italy, anarchists organised a very successful Municipal Federation of the Base (FMB) in Spezzano Albanese. This organisation, in the words of one activist, is “an alternative to the power of the town hall” and provides a “glimpse of what a future libertarian society could be.” Its aim is “the bringing together of all interests within the district. In intervening at a municipal level, we become involved not only in the world of work but also the life of the community … the FMB make counter proposals [to Town Hall decisions], which aren’t presented to the Council but proposed for discussion in the area to raise people’s level of consciousness. Whether they like it or not the Town Hall is obliged to take account of these proposals.” In addition, the FMB also supports co-operatives within it, so creating a communalised, self-managed economic sector within capitalism. Such a development helps to reduce the problems facing isolated co-operatives in a capitalist economy — see section J.5.11 — and was actively done in order to “seek to bring together all the currents, all the problems and contradictions, to seek solutions” to such problems facing co-operatives. [“Community Organising in Southern Italy”, pp. 16–19, Black Flag, no. 210, p. 17 and p. 18]

Elsewhere in Europe, the long, hard work of the C.N.T. in Spain has also resulted in mass village assemblies being created in the Puerto Real area, near Cadiz. These community assemblies came about to support an industrial struggle by shipyard workers. One C.N.T. member explains: “Every Thursday of every week, in the towns and villages in the area, we had all-village assemblies where anyone connected with the particular issue [of the rationalisation of the shipyards], whether they were actually workers in the shipyard itself, or women or children or grandparents, could go along … and actually vote and take part in the decision making process of what was going to take place.” With such popular input and support, the shipyard workers won their struggle. However, the assembly continued after the strike and “managed to link together twelve different organisations within the local area that are all interested in fighting … various aspects” of capitalism including health, taxation, economic, ecological and cultural issues. Moreover, the struggle “created a structure which was very different from the kind of structure of political parties, where the decisions are made at the top and they filter down. What we managed to do in Puerto Real was make decisions at the base and take them upwards.” [Anarcho-Syndicalism in Puerto Real: from shipyard resistance to direct democracy and community control, p. 6]

More recently, the December 2001 revolt against neo-liberalism in Argentina saw hundreds of neighbourhood assemblies created across the country. These quickly federated into inter-barrial assemblies to co-ordinate struggles. The assemblies occupied buildings, created communal projects like popular kitchens, community centres, day-care centres and built links with occupied workplaces. As one participant put it: “The initial vocabulary was simply: Let’s do things for ourselves, and do them right. Let’s decide for ourselves. Let’s decide democratically, and if we do, then let’s explicitly agree that we’re all equals here, that there are no bosses … We lead ourselves. We lead together. We lead and decide amongst ourselves … no one invented it … It just happened. We met one another on the corner and decided, enough! … Let’s invent new organisational forms and reinvent society.” Another notes that this was people who “begin to solve problems themselves, without turning to the institutions that caused the problems in the first place.” The neighbourhood assemblies ended a system in which “we elected people to make our decisions for us … now we will make our own decisions.” While the “anarchist movement has been talking about these ideas for years” the movement took them up “from necessity.” [Marina Sitrin (ed.), Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina, p. 41 and pp. 38–9]

The idea of community organising has long existed within anarchism. Kropotkin pointed to the directly democratic assemblies of Paris during the French Revolution> These were “constituted as so many mediums of popular administration, it remained of the people, and this is what made the revolutionary power of these organisations.” This ensured that the local revolutionary councils “which sprang from the popular movement was not separated from the people.” In this popular self-organisation “the masses, accustoming themselves to act without receiving orders from the national representatives, were practising what was described later on as Direct Self-Government.” These assemblies federated to co-ordinate joint activity but it was based on their permanence: “that is, the possibility of calling the general assembly whenever it was wanted by the members of the section and of discussing everything in the general assembly.” In short, “the Commune of Paris was not to be a governed State, but a people governing itself directly — when possible — without intermediaries, without masters” and so “the principles of anarchism … had their origin, not in theoretic speculations, but in the deeds of the Great French Revolution.” This “laid the foundations of a new, free, social organisation”and Kropotkin predicted that “the libertarians would no doubt do the same to-day.” [Great French Revolution, vol. 1, p. 201, p. 203, pp. 210–1, p. 210, p. 204 and p. 206]

In Chile during 1925 “a grass roots movement of great significance emerged,” the tenant leagues (ligas do arrendatarios). The movement pledged to pay half their rent beginning the 1st of February, 1925, at huge public rallies (it should also be noted that “Anarchist labour unionists had formed previous ligas do arrendatarios in 1907 and 1914.”). The tenants leagues were organised by ward and federated into a city-wide council. It was a vast organisation, with 12,000 tenants in just one ward of Santiago alone. The movement also “press[ed] for a law which would legally recognise the lower rents they had begun paying .. . the leagues voted to declare a general strike … should a rent law not be passed.” The government gave in, although the landlords tried to get around it and, in response, on April 8th “the anarchists in Santiago led a general strike in support of the universal rent reduction of 50 percent.” Official figures showed that rents “fell sharply during 1915, due in part to the rent strikes” and for the anarchists “the tenant league movement had been the first step toward a new social order in Chile.” [Peter DeShazo, Urban Workers and Labor Unions in Chile 1902–1927, p. 223, p. 327, p. 223, p. 225 and p. 226] As one Anarchist newspaper put it:

“This movement since its first moments had been essentially revolutionary. The tactics of direct action were preached by libertarians with highly successful results, because they managed to instil in the working classes the idea that if landlords would not accept the 50 percent lowering of rents, they should pay nothing at all. In libertarian terms, this is the same as taking possession of common property. It completes the first stage of what will become a social revolution.” [quoted by DeShazo, Op. Cit., p. 226]

A similar concern for community organising and struggle was expressed in Spain. While the collectives during the revolution are well known, the CNT had long organised in the community and around non-workplace issues. As well as neighbourhood based defence committees to organise and co-ordinate struggles and insurrections, the CNT organised various community based struggles. The most famous example of this must be the rent strikes during the early 1930s in Barcelona. In 1931, the CNT’s Construction Union organised a “Economic Defence Commission” to organise against high rents and lack of affordable housing. Its basic demand was for a 40% rent decrease but it also addressed unemployment and the cost of food. The campaign was launched by a mass meeting on May 1st, 1931. A series of meetings were held in the various working class neighbourhoods of Barcelona and in surrounding suburbs. This culminated in a mass meeting held at the Palace of Fine Arts on July 5th which raised a series of demands for the movement. By July, 45,000 people were taking part in the rent strike and this rose to over 100,000 by August. As well as refusing to pay rent, families were placed back into their homes from which they had been evicted. The movement spread to a number of the outlying towns which set up their own Economic Defence Commissions. The local groups co-ordinated actions their actions out of CNT union halls or local libertarian community centres. The movement faced increased state repression but in many parts of Barcelona landlords had been forced to come to terms with their tenants, agreeing to reduced rents rather than facing the prospect of having no income for an extended period or the landlord simply agreed to forget the unpaid rents from the period of the rent strike. [Nick Rider, “The Practice of Direct Action: the Barcelona rent strike of 1931”, For Anarchism, David Goodway (ed.), pp. 79–105] As Abel Paz summarised:

“Unemployed workers did not receive or ask for state aid … The workers’ first response to the economic crisis was the rent, gas, and electricity strike in mid-1933, which the CNT and FAI’s Economic Defence Committee had been laying the foundations for since 1931. Likewise, house, street, and neighbourhood groups began to turn out en masse to stop evictions and other coercive acts ordered by the landlords (always with police support). The people were constantly mobilised. Women and youngsters were particularly active; it was they who challenged the police and stopped the endless evictions.” [Durrutu in the Spanish Revolution, p. 308]

In Gijon, the CNT “reinforced its populist image by … its direct consumer campaigns. Some of these were organised through the federation’s Anti-Unemployment Committee, which sponsored numerous rallies and marches in favour of ‘bread and work.’ While they focused on the issue of jobs, they also addressed more general concerns about the cost of living for poor families. In a May 1933 rally, for example, demonstrators asked that families of unemployed workers not be evicted from their homes, even if they fell behind on the rent.” The “organisers made the connections between home and work and tried to draw the entire family into the struggle.” However, the CNT’s “most concerted attempt to bring in the larger community was the formation of a new syndicate, in the spring of 1932, for the Defence of Public Interests (SDIP). In contrast to a conventional union, which comprised groups of workers, the SDIP was organised through neighbourhood committees. Its specific purpose was to enforce a generous renters’ rights law of December 1931 that had not been vigorously implemented. Following anarchosyndicalist strategy, the SDIP utilised various forms of direct action, from rent strikes, to mass demonstrations, to the reversal of evictions.” This last action involved the local SDIP group going to a home, breaking the judge’s official eviction seal and carrying the furniture back in from the street. They left their own sign: ”opened by order of the CNT.” The CNT’s direct action strategies “helped keep political discourse in the street, and encouraged people to pursue the same extra-legal channels of activism that they had developed under the monarchy.” [Pamela Beth Radcliff, From mobilization to civil war, pp. 287–288 and p. 289]

In these ways, grassroots movements from below were created, with direct democracy and participation becoming an inherent part of a local political culture of resistance, with people deciding things for themselves directly and without hierarchy. Such developments are the embryonic structures of a world based around participation and self-management, with a strong and dynamic community life. For, as Martin Buber argued, ”[t]he more a human group lets itself be represented in the management of its common affairs … the less communal life there is in it and the more impoverished it becomes as a community.” [Paths in Utopia, p. 133]

Anarchist support and encouragement of community unionism, by creating the means for communal self-management, helps to enrich the community as well as creating the organisational forms required to resist the state and capitalism. In this way we build the anti-state which will (hopefully) replace the state. Moreover, the combination of community unionism with workplace assemblies (as in Puerto Real), provides a mutual support network which can be very effective in helping winning struggles. For example, in Glasgow, Scotland in 1916, a massive rent strike was finally won when workers came out in strike in support of the rent strikers who been arrested for non-payment. Such developments indicate that Isaac Puente was correct:

“Libertarian Communism is a society organised without the state and without private ownership. And there is no need to invent anything or conjure up some new organisation for the purpose. The centres about which life in the future will be organised are already with us in the society of today: the free union and the free municipality [or Commune].

”The union: in it combine spontaneously the workers from factories and all places of collective exploitation.

“And the free municipality: an assembly … where, again in spontaneity, inhabitants … combine together, and which points the way to the solution of problems in social life …

“Both kinds of organisation, run on federal and democratic principles, will be sovereign in their decision making, without being beholden to any higher body, their only obligation being to federate one with another as dictated by the economic requirement for liaison and communications bodies organised in industrial federations.

“The union and the free municipality will assume the collective or common ownership of everything which is under private ownership at present [but collectively used] and will regulate production and consumption (in a word, the economy) in each locality.

“The very bringing together of the two terms (communism and libertarian) is indicative in itself of the fusion of two ideas: one of them is collectivist, tending to bring about harmony in the whole through the contributions and co-operation of individuals, without undermining their independence in any way; while the other is individualist, seeking to reassure the individual that his independence will be respected.” [Libertarian Communism, pp. 6–7]

The combination of community unionism, along with industrial unionism (see next section), will be the key to creating an anarchist society, Community unionism, by creating the free commune within the state, allows us to become accustomed to managing our own affairs and seeing that an injury to one is an injury to all. In this way a social power is created in opposition to the state. The town council may still be in the hands of politicians, but neither they nor the central government would be able to move without worrying about what the people’s reaction might be, as expressed and organised in their community assemblies and federations.

#community unionism#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

FYI if you see a news article about a Jewish convention in Kerala, India, being bombed by anti-Zionist Muslims, it's a lie. The convention was one of Jehovah's Witnesses and no one knows who did it yet. Please be on the lookout for fake news of antisemitic violence attempting to communalise violence by Muslims and vice versa, not just in the West but all over the world. Both antisemites and Islamphobes are looking to capitalize on the ongoing Gazan genocide and Israel's rhetoric against Hamas so they can push their own agenda.

#free palestine#islamphobia#antisemitism#anti zionisim#palestinian genocide#gaza genocide#fascism#current events#knee of huss

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

En tout cas si la pénurie de pilules abortives, créées avec des molécules déposées par une seule entreprise américaine, qui a ralenti la production parce que les États-Unis sont là pire dystopie, prouve bien quelque chose, c'est qu'il faut lever les brevets sur toutes les molécules et il faut communaliser la pharmaceutique dans son ensemble.

Pareil pour les médocs de remplacement hormonal. Pareil pour l'insuline pour la ventoline pour pour pour pour

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hasina flees Bangladesh bleeds. What awaits Delhi? Top takeaways

A man proudly climbs atop the statue of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman – Bangabandhu, the founding father of Bangladesh and urinates on his head. While others bring down his statue with bricks and bats. Museums were ransacked and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s official residence ‘Ganabhaban’ was stormed. Protesters walked out with conquests – stolen furniture, her saree and inner garments. These were visuals from a Bangladesh that fell into the lap of anarchy after months of protests peaked to end Hasina’s 15-year rule and forced her to abruptly fly out of Dhaka. One of India’s friendly neighbours, Bangladesh shares a long history with the country and finds common ground in language, culture and cuisine with West Bengal across the border. Now its future is uncertain.

Sheikh Hasina recently visited India to attend PM Modi’s swearing-in ceremony and had acknowledged Dhaka’s good ties with Delhi when she became the Prime Minister for the fourth time in January this year after her party, the Awami League, won the general elections boycotted by much of the opposition over allegations of rigging. As the bloody crisis continues to swell, it’s pertinent to understand Delhi’s approach to the developments.

BANGLADESH NEW REGIME DOES NOT WANT CONFRONTATION WITH INDIA

What’s getting many anxious is the anticipation that the new government after Hasina might be anti-India or anti-Hindu. Even as Hasina faced allegations of widespread corruption, she could, to a large extent, control the communal elements. With her gone, the thought of an extremist regime got many worried. But Dhaka has assured that attacks on Hindus will be controlled and, as per a report today, such instances have been broadly controlled. Bangladesh is volatile, but the army is in constant touch with the Ministry of External Affairs in India. EAM Jaishankar also assured in Parliament that the Indian government is in touch with the Bangladesh Army in light of the recent developments.

BANGLADESH STILL NEEDS ECONOMIC AID AND SUPPORT FROM INDIA

Even as anti-India protests erupted in Dhaka months before and is still a dominant sentiment across the protest-engulfed country, Dhaka still needs economic aid and support from Delhi, which makes it clear that it can’t afford to have an anti-India stance at this point. Further, India has also not given shelter to Hasina to not upset the Army-backed caretaker government – a move that does not isolate Delhi from the rest of Southeast Asia and does not give advantage to China.

DELHI ON WAIT-AND-WATCH MODE

The movement that forced Hasina to step down also allegedly had the backing of Pakistan’s ISI and Jamat as claimed by experts, and what gave wind to it was the discontentment among the people over quota and employment. External forces which allegedly are at play could have their eyes on the stability around India. But India is on wait-and-watch mode and a top-level meeting on the crisis has also been chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi along with Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, Home Minister Amit Shah, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman.

CENTRE IN TOUCH WITH BENGAL GOVERNMENT OVER INFILTRATION FEARS

Bengal-Bangladesh border was a matter of concern as many feared large-scale infiltration amid the communal undertones that run through Dhaka’s volatile nerves. Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has appealed for peace and requested not to communalise the crisis as she assured that the state government would work according to the instructions of the Centre. However, the closing of the Petropol border has affected daily trade. Moreover, this is not a TMC Vs BJP battle, but a pivotal development that concerns India with the potential of reshaping geopolitics surrounding the subcontinent.

Published On:

Aug 7, 2024

Tune In

Source link

via

The Novum Times

0 notes

Text

"So more than ever, the point of the writer is to be unpopular. The point of the writer is to say: "I denounce you even if I'm not in the majority." "Only a novel can tell you how caste, communalisation, sexism, love, music, poetry, the rise of the right all combine in a society. And the depths in which they combine."

— Arundhati Roy

1 note

·

View note

Text

Congress’ Dinesh Gundu Rao Says BJP Raking Up Non-Issues Like Halal, Hijab to Communalise; Clears Air on Tie-Up With JDS

Last Updated: February 15, 2023, 09:04 IST

Dinesh Gundu Rao (in pic), who represents the Gandhinagar constituency in Bengaluru, also lamented that CM Basavaraj Bommai has not held a meeting with any of the city MLAs and has been taking ‘ad hoc’ decisions. (Twitter @dineshgrao)

The Congress leader said the BJP was raising non-issues like Halal, Hijab and the Tipu versus Savarkar debate as they…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

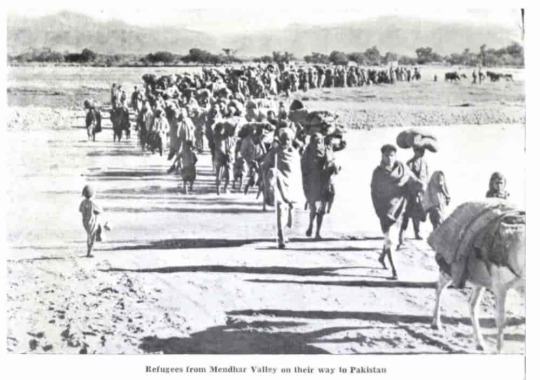

The Forgotten Jammu Massacre

In November 1947, thousands of Muslims were murdered in Jammu by paramilitaries under the command of Maharaja Hari Singh’s army, the Hindu Dogra ruler of Jammu and Kashmir. Although the precise number of victims in the killings that lasted for two months is unknown, estimates range from 20,000 to 237,000. Nearly half a million Muslims were compelled to flee across the border into the recently formed country of Pakistan. These Muslims had to settle in the part of Kashmir that is under Pakistan’s administration. The massacre of Muslims in Jammu and the forced migration of others set off a chain of events that included a war between India and Pakistan, two newly independent countries. These incidents also gave rise to theKashmir issue. The massacres occurred as part of a British-designed strategy to divide the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, as millions of Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs crossed the border from one side to the other.

An Orchestrated Massacre

Before the two-decade-long massacre against Jammu’s Muslim majority really began, The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) leaders from Amritsar met in secret with the Maharaja and his officials. They chose Poonch as the beginning place for the massacre of Muslims because of its record for fierce resistance. A two decade long and horrifying anti-Muslim pogrom began with the murder of a herdsman in the Panj Peer shrine and a Muslim labourer in the centre of Jammu city in the first week of September. Extremist Hindus and Sikhs committed the murders with the help and complicity of the Maharaja Hari Singh-led armies of the Dogra State. The RSS leaders and workers were complicit in organising and carrying out the atrocities.

Idrees Kanth, a fellow at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam who studied the history of Kashmir in the 1940s, told Al Jazeera that the immediate impact (of partition) was seen in Jammu. “The Muslim subjects from different parts of Jammu province were forcibly displaced by the Dogra Army in a programme of expulsion and murder carried out over three weeks between October-November 1947,”.

The Dogra Army personnel started evicting Muslim peasants from Jammu province in the middle of October. The majority of the refugees were housed in refugee camps in the districts of Sialkot, Jhelum, Gujrat, and Rawalpindi after being directed on foot toward West Punjab, which would eventually become a part of Pakistan.

On November 5, Kanth claimed about the Dogra Army forces’ planned evacuation of Muslims that “Instead of sending them to Sialkot, as they had been promised, the trucks drove them to wooded hills of Rajouri districts of Jammu, where they were executed.”

Demographic Changes

After the deaths and expulsion, the Muslims, who made up more than 60% of the population in the Jammu region, became a minority. According to a story from The Times, London, dated August 10, 1948: “2,37,000 Muslims were systematically exterminated – unless they escaped to Pakistan along the border – by the forces of the Dogra State headed by the Maharaja in person and aided by Hindus and Sikhs. This happened in October 1947, five days before the Pathan invasion and nine days before the Maharaja’s accession to India.”.

According to historians, the executions carried out by the Sikh and Hindu ruler’s armies were part of a “state sponsored genocide” to alter Jammu’s demographics, which had a predominately Muslim population.

Reports mention that Muslims who earlier were the majority (61 percent) in the Jammu region became a minority as a result of the Jammu massacre and subsequent migration.

According to PG Rasool, the author of a book The Historical Reality of Kashmir Dispute “The massacre of more than two lakh (two hundred thousands) Muslims was state-sponsored and state supported. The forces from Patiala Punjab were called in, RSS was brought to communalise the whole scenario and kill Muslims.”

Covering up of the Jammu Massacre

While it is unknown how many people were killed during the two-month-long killing spree, Horace Alexander’s report from The Spectator on January 16, 1948, is frequently cited. Alexander claimed that 200,000 people had died and that nearly 500,000 people had been displaced across the border into the recently formed country of Pakistan and the region of Kashmir that it controls.

India has ever since tried to free itself from the accountability of the past. The Jammu massacre has not only been left out of J&K’s historical narratives by the Indian state, but it has also been openly denied in its entirety.

Khurram Parvez, a noted human rights defender in Kashmir, told Al Jazeera that the ongoing conflict in Kashmir has its roots in 1947 massacre. “It is deliberately forgotten. Actually, the violence of that massacre in 1947 continues. Those who were forced to migrate to Pakistan have never been allowed to return,” he said.

What Does the Jammu Massacre mean for Kashmir today?

TheJammu massacregave India the opportunity to rewrite history, therefore relieving the Indian government from owning up to any responsibility for the atrocity. The Indian government is attempting to replicate this pattern in the Kashmir valley by systematically killing and exterminating Muslims and then covering it up. As more and more Indians obtain Kashmiri citizenship and are granted the ability to vote in state elections, this provides the necessary motive and encouragement for non-Kashmiris to relocate to Kashmir. While the right-wing BJP government has been milking the targeted killings of Kashmiri pandits in Kashmir. The communal violence against Muslims and the Jammu Massacre is the least talked about and written about in the history of the region.

1 note

·

View note

Text

everything in india sucks so bad right now wrt to religious minorities just...living their life, and here in [redacted] particularly it has been sooooo reprehensible this December. Just terrible. It’s awful to think we are going into every new year with such an overhanging sense of gloom of basic rights being snatched away let alone joy. It’s been fucked up but wishing everyone a really safe holiday season since most places get leave from now!!! stay safe and strong xoxo

#it was nrc-caa in 2019 December in late 2020 early 21 it was the communalisation of farmers protests by the govt and now the#anti conversion law coupled with non stop attacks in so many states on Christian and Muslim religious places this month and particularly#vulnerable Dalit communities which DO of course choose to follow diff faiths to get out of the caste system#been awful forever but particularly these three years it’s been crushing with Covid too...just have a nice last stretch of the year💞💞💞

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

India has been turned into an architecture of fractures wantonly and consciously wreaked; and that in the pursuit of fashioning these fractures, Indians have been encouraged to go after other Indians, liberally fed on lies and prejudice, exhorted by dog-whistling from the top and brazenly led to murder and mayhem by gas-lighter commanders possessed of run over the law. Indians have been killed for what they wear, what they eat, what they are called, what books they read, who they pray to. The killers have come to be treated like heroes of spectator sport; they’ve been garlanded and celebrated.

Sankarshan Thakur, ‘What wasn’t written’, The Telegraph

#The Telegraph#Sankarshan Thakur#India#Indians#lies#prejudice#dog-whistling#murder#mayhem#law#lynching#mob violence#communalisation#BJP#NDA

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

From: Rape and the Construction of Communal Identity by Kalpana Kannabiran

#embodied violence#communalising women's sexuality in south asia#kalpana kannabiran#essay 2#trigger warning rape#tw#rape#brahmanical patriarchy#women from minority communities#communalism#excpt

0 notes

Text

A.3.2 Are there different types of social anarchism?

Yes. Social anarchism has four major trends — mutualism, collectivism, communism and syndicalism. The differences are not great and simply involve differences in strategy. The one major difference that does exist is between mutualism and the other kinds of social anarchism. Mutualism is based around a form of market socialism — workers’ co-operatives exchanging the product of their labour via a system of community banks. This mutual bank network would be “formed by the whole community, not for the especial advantage of any individual or class, but for the benefit of all … [with] no interest … exacted on loans, except enough to cover risks and expenses.” Such a system would end capitalist exploitation and oppression for by “introducing mutualism into exchange and credit we introduce it everywhere, and labour will assume a new aspect and become truly democratic.” [Charles A. Dana, Proudhon and his “Bank of the People”, pp. 44–45 and p. 45]

The social anarchist version of mutualism differs from the individualist form by having the mutual banks owned by the local community (or commune) instead of being independent co-operatives. This would ensure that they provided investment funds to co-operatives rather than to capitalistic enterprises. Another difference is that some social anarchist mutualists support the creation of what Proudhon termed an “agro-industrial federation” to complement the federation of libertarian communities (called communes by Proudhon). This is a “confederation … intended to provide reciprocal security in commerce and industry” and large scale developments such as roads, railways and so on. The purpose of “specific federal arrangements is to protect the citizens of the federated states [sic!] from capitalist and financial feudalism, both within them and from the outside.” This is because “political right requires to be buttressed by economic right.” Thus the agro-industrial federation would be required to ensure the anarchist nature of society from the destabilising effects of market exchanges (which can generate increasing inequalities in wealth and so power). Such a system would be a practical example of solidarity, as “industries are sisters; they are parts of the same body; one cannot suffer without the others sharing in its suffering. They should therefore federate, not to be absorbed and confused together, but in order to guarantee mutually the conditions of common prosperity … Making such an agreement will not detract from their liberty; it will simply give their liberty more security and force.” [The Principle of Federation, p. 70, p. 67 and p. 72]

The other forms of social anarchism do not share the mutualists support for markets, even non-capitalist ones. Instead they think that freedom is best served by communalising production and sharing information and products freely between co-operatives. In other words, the other forms of social anarchism are based upon common (or social) ownership by federations of producers’ associations and communes rather than mutualism’s system of individual co-operatives. In Bakunin’s words, the “future social organisation must be made solely from the bottom upwards, by the free association or federation of workers, firstly in their unions, then in the communes, regions, nations and finally in a great federation, international and universal” and “the land, the instruments of work and all other capital may become the collective property of the whole of society and be utilised only by the workers, in other words by the agricultural and industrial associations.” [Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, p. 206 and p. 174] Only by extending the principle of co-operation beyond individual workplaces can individual liberty be maximised and protected (see section I.1.3 for why most anarchists are opposed to markets). In this they share some ground with Proudhon, as can be seen. The industrial confederations would “guarantee the mutual use of the tools of production which are the property of each of these groups and which will by a reciprocal contract become the collective property of the whole … federation. In this way, the federation of groups will be able to … regulate the rate of production to meet the fluctuating needs of society.” [James Guillaume, Bakunin on Anarchism, p. 376]

These anarchists share the mutualists support for workers’ self-management of production within co-operatives but see confederations of these associations as being the focal point for expressing mutual aid, not a market. Workplace autonomy and self-management would be the basis of any federation, for “the workers in the various factories have not the slightest intention of handing over their hard-won control of the tools of production to a superior power calling itself the ‘corporation.’” [Guillaume, Op. Cit., p. 364] In addition to this industry-wide federation, there would also be cross-industry and community confederations to look after tasks which are not within the exclusive jurisdiction or capacity of any particular industrial federation or are of a social nature. Again, this has similarities to Proudhon’s mutualist ideas.

Social anarchists share a firm commitment to common ownership of the means of production (excluding those used purely by individuals) and reject the individualist idea that these can be “sold off” by those who use them. The reason, as noted earlier, is because if this could be done, capitalism and statism could regain a foothold in the free society. In addition, other social anarchists do not agree with the mutualist idea that capitalism can be reformed into libertarian socialism by introducing mutual banking. For them capitalism can only be replaced by a free society by social revolution.

The major difference between collectivists and communists is over the question of “money” after a revolution. Anarcho-communists consider the abolition of money to be essential, while anarcho-collectivists consider the end of private ownership of the means of production to be the key. As Kropotkin noted, collectivist anarchism “express[es] a state of things in which all necessaries for production are owned in common by the labour groups and the free communes, while the ways of retribution [i.e. distribution] of labour, communist or otherwise, would be settled by each group for itself.” [Anarchism, p. 295] Thus, while communism and collectivism both organise production in common via producers’ associations, they differ in how the goods produced will be distributed. Communism is based on free consumption of all while collectivism is more likely to be based on the distribution of goods according to the labour contributed. However, most anarcho-collectivists think that, over time, as productivity increases and the sense of community becomes stronger, money will disappear. Both agree that, in the end, society would be run along the lines suggested by the communist maxim: “From each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.” They just disagree on how quickly this will come about (see section I.2.2).

For anarcho-communists, they think that “communism — at least partial — has more chances of being established than collectivism” after a revolution. [Op. Cit., p. 298] They think that moves towards communism are essential as collectivism “begins by abolishing private ownership of the means of production and immediately reverses itself by returning to the system of remuneration according to work performed which means the re-introduction of inequality.” [Alexander Berkman, What is Anarchism?, p. 230] The quicker the move to communism, the less chances of new inequalities developing. Needless to say, these positions are not that different and, in practice, the necessities of a social revolution and the level of political awareness of those introducing anarchism will determine which system will be applied in each area.

Syndicalism is the other major form of social anarchism. Anarcho-syndicalists, like other syndicalists, want to create an industrial union movement based on anarchist ideas. Therefore they advocate decentralised, federated unions that use direct action to get reforms under capitalism until they are strong enough to overthrow it. In many ways anarcho-syndicalism can be considered as a new version of collectivist-anarchism, which also stressed the importance of anarchists working within the labour movement and creating unions which prefigure the future free society.

Thus, even under capitalism, anarcho-syndicalists seek to create “free associations of free producers.” They think that these associations would serve as “a practical school of anarchism” and they take very seriously Bakunin’s remark that the workers’ organisations must create “not only the ideas but also the facts of the future itself” in the pre-revolutionary period.

Anarcho-syndicalists, like all social anarchists, “are convinced that a Socialist economic order cannot be created by the decrees and statutes of a government, but only by the solidaric collaboration of the workers with hand and brain in each special branch of production; that is, through the taking over of the management of all plants by the producers themselves under such form that the separate groups, plants, and branches of industry are independent members of the general economic organism and systematically carry on production and the distribution of the products in the interest of the community on the basis of free mutual agreements.” [Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho-syndicalism, p. 55]

Again, like all social anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists see the collective struggle and organisation implied in unions as the school for anarchism. As Eugene Varlin (an anarchist active in the First International who was murdered at the end of the Paris Commune) put it, unions have “the enormous advantage of making people accustomed to group life and thus preparing them for a more extended social organisation. They accustom people not only to get along with one another and to understand one another, but also to organise themselves, to discuss, and to reason from a collective perspective.” Moreover, as well as mitigating capitalist exploitation and oppression in the here and now, the unions also “form the natural elements of the social edifice of the future; it is they who can be easily transformed into producers associations; it is they who can make the social ingredients and the organisation of production work.” [quoted by Julian P. W. Archer, The First International in France, 1864–1872, p. 196]

The difference between syndicalists and other revolutionary social anarchists is slight and purely revolves around the question of anarcho-syndicalist unions. Collectivist anarchists agree that building libertarian unions is important and that work within the labour movement is essential in order to ensure “the development and organisation … of the social (and, by consequence, anti-political) power of the working masses.” [Bakunin, Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, p. 197] Communist anarchists usually also acknowledge the importance of working in the labour movement but they generally think that syndicalistic organisations will be created by workers in struggle, and so consider encouraging the “spirit of revolt” as more important than creating syndicalist unions and hoping workers will join them (of course, anarcho-syndicalists support such autonomous struggle and organisation, so the differences are not great). Communist-anarchists also do not place as great an emphasis on the workplace, considering struggles within it to be equal in importance to other struggles against hierarchy and domination outside the workplace (most anarcho-syndicalists would agree with this, however, and often it is just a question of emphasis). A few communist-anarchists reject the labour movement as hopelessly reformist in nature and so refuse to work within it, but these are a small minority.

Both communist and collectivist anarchists recognise the need for anarchists to unite together in purely anarchist organisations. They think it is essential that anarchists work together as anarchists to clarify and spread their ideas to others. Syndicalists often deny the importance of anarchist groups and federations, arguing that revolutionary industrial and community unions are enough in themselves. Syndicalists think that the anarchist and union movements can be fused into one, but most other anarchists disagree. Non-syndicalists point out the reformist nature of unionism and urge that to keep syndicalist unions revolutionary, anarchists must work within them as part of an anarchist group or federation. Most non-syndicalists consider the fusion of anarchism and unionism a source of potential confusion that would result in the two movements failing to do their respective work correctly. For more details on anarcho-syndicalism see section J.3.8 (and section J.3.9 on why many anarchists reject aspects of it). It should be stressed that non-syndicalist anarchists do not reject the need for collective struggle and organisation by workers (see section H.2.8 on that particular Marxist myth).

In practice, few anarcho-syndicalists totally reject the need for an anarchist federation, while few anarchists are totally anti-syndicalist. For example, Bakunin inspired both anarcho-communist and anarcho-syndicalist ideas, and anarcho-communists like Kropotkin, Malatesta, Berkman and Goldman were all sympathetic to anarcho-syndicalist movements and ideas.

For further reading on the various types of social anarchism, we would recommend the following: mutualism is usually associated with the works of Proudhon, collectivism with Bakunin’s, communism with Kropotkin’s, Malatesta’s, Goldman’s and Berkman’s. Syndicalism is somewhat different, as it was far more the product of workers’ in struggle than the work of a “famous” name (although this does not stop academics calling George Sorel the father of syndicalism, even though he wrote about a syndicalist movement that already existed. The idea that working class people can develop their own ideas, by themselves, is usually lost on them). However, Rudolf Rocker is often considered a leading anarcho-syndicalist theorist and the works of Fernand Pelloutier and Emile Pouget are essential reading to understand anarcho-syndicalism. For an overview of the development of social anarchism and key works by its leading lights, Daniel Guerin’s excellent anthology No Gods No Masters cannot be bettered.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

☑️ Study A Foreign Language

Is Persian Really A Foreign language considering how it has always been a larger part of the subcontinent for a considerable amount of time until it started to disappear and was taken over by other narratives which in one way or the other adapted certain words from the language to keep the momentum?

A Week or so ago, we saw an Issue of how Urdu was being communalised and taken into a whole other perspective so as to create this idea in people how certain languages belong to a certain society. We saw people backlashing this idea, as they should, and bringing into light how each was interconnected and not really a language of the particular community as these fascists believe it to be.

Today, 8 November 2021, I had my first Persian Lesson. A Fellow Classmate asked me, "Why Persian?" Well, I have always been a Fan of Urdu, and Persian intrigued me just as much.

Here is to New beginnings.

#persian#studyblr#student life#studyspiration#students#being productive#language#language learning#foreign languages#farsi#uni#study tips#college student#university student#university#study#college#academics#literature

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note 1: That everything goes on ‘is’ the crisis

12/4/2020

The abyss of greed and hate grows historically. When the victim is weak and helpless, evil is exposed even more. The conditional donation made in favour of Assam Arogya Nidhi by a few members of the Foreigners’ Tribunals in Assam (see the attached image below for details), a kangaroo court like institution in Assam which have brought nothing by horror to people’s life, reeks of racisms and a culmination of the same. It shows how even amidst death and despair some people are incapable of love or empathy. Even when we live in an expectational time when the human body is put to test and when we know that any human flesh can be affected by the virus, in Assam, as it is with other places, finding a soft target who can be manufactured as a carrier of the virus is seen with disturbing regularity. It does two things, if not more.

Firstly, it displaces the immediate concern of millions of migrant workers dying in the streets, trapped, foodless and not to say impoverished beyond measure. This shifts the attention or dilutes the attention that is given to the apathies of reverse migration happening in India to a blame game of who spread the virus.

Secondly, by shifting this blame solely on one community, it shift any repercussion of the virus onto Muslims, the soft target, so that they can be turned into demons for any catastrophe that the virus will cause in the future. This will dilute the criticism which the government would have to bare for their lack of effort in containing the pandemic. It establishes that Muslims are the superior careers of the virus and are more potent than any other beings.

This shows how a pandemic can be given a communal turn. It also shows us that communalism is more adaptive than we thought and how a fascist state never lets a crisis go to waste to drive its ends.

“This is a time for facts, not fear

This is a time for science, not rumours

This is a time for solidarity, not stigma

We are all in this together.”

These were the words of WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus back in January this year.

On the other hand, Indian Medical Association asked hospitals and practitioners to supress data in India and Press Trust of India with shocking ignorance tweeted: “Corovavirus is not a health emergency”.

We are amidst a major public health crisis where there is underreporting and a grave lack of testing in India yet everything goes on and a deepening of communalisation around the agents of virus. I am reminded of what Terry Egalton once said referring to Walter Benjamin that a situation where ‘everything goes on is the crisis’.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir - The family of Israr Ahmad Khan lived through the massacre of Jammu in what was then part of the princely state of Kashmir. He recalls that many of his relatives were killed during the violence that followed months after British rule over Indian sub-continent ended.

"My father was young then and other immediate family members were in Kashmir at that time. But many of my relatives were brutally killed," the 63-year-old told Al Jazeera.

"To be honest that was a mad period. There was no humanity shown at that time," Khan, who retired as senior police officer, said at his home in Jammu.

In November 1947, thousands of Muslims were massacred in Jammu region by mobs and paramilitaries led by the army of Dogra ruler Hari Singh.

The exact number of casualties in the killings that continued for two months is not known but estimates range from 20,000 to 237,000 and nearly half million forced into displacement across the border into the newly created nation of Pakistan and its administered part of Kashmir.

Khan said many of his relatives had escaped to Pakistan, where they continue to live. "The incident divided families. There were a lot of Muslims in Jammu but now you won't find many," he said.

The killings triggered a series of events, including a war between two newly independent nations of India and Pakistan, which gave birth to Kashmir dispute.

The killings took place when millions of Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs were crossing the border from the one side to the other, as part of British-designed plan to partition the subcontinent into India and Pakistan.

"The immediate impact (of partition) was in Jammu. The Muslim subjects from different parts of Jammu province were forcibly displaced by the Dogra Army in a programme of expulsion and murder carried out over three weeks between October-November 1947," Idrees Kanth, a fellow at International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, who researched the 1940s history of Kashmir, told Al Jazeera.

In mid-October, the Dogra Army troops began expelling Muslim villagers from Jammu province. The refugees were sent on foot toward West Punjab (later to form part of Pakistan), where most were accommodated in refugee camps in the districts of Sialkot, Jhelum, Gujrat and Rawalpindi.

On November 5, Kanth said, the Dogra Army soldiers began another organised evacuation of the Muslims but "instead of taking them to Sialkot, as they had been promised, the trucks drove them to forest hills of Rajouri districts of Jammu, where they were executed".

Kanth added that there may have been a systematic attempt by the dying Dogra regime to ensure that records of the incident are destroyed and made it a lesser known massacre of the partition.

"I guess as happens with certain events, they got lost to history and resurface at a later time and in that sense they sort of rewrite our memory of the past. I would say the particular incident was sort of lost on us to a great extent until the post 1990s when the event was resurrected as yet another example of Dogra regime's communal politics," Kanth said.

'Demographic changes'

The historians say that the killings carried out by the Hindu ruler's army and Sikh army was a "state sponsored genocide" to bring out demographic changes in Jammu - a region which had an overwhelming population of Muslims.

"The massacre of more than two lakh (two hundred thousands) Muslims was state-sponsored and state supported. The forces from Patiala Punjab were called in, RSS (a right-wing Hindu organisation) was brought to communalise the whole scenario and kill Muslims," said PG Rasool, the author of a book The Historical Reality of Kashmir Dispute.

The Muslims, who constituted more than 60 percent of the population of Jammu region, were reduced to a minority after the killings and displacement.

He said that when the then Indian Prime Minister of India Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru and Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah met a delegation of Muslims in Jammu, they were told about the "tragic events" but they preferred to remain silent.

"They didn't want that people in Kashmir - which had a Muslim majority from the beginning - should know about it because it could have led to demonstrations. The state from the beginning has tried to cover up it. I don't call it massacre but it was a staged genocide that is unfortunately not talked about," he said.

"They thought even if they lose Kashmir at least they should get Jammu and the only way was to have a Hindu majority."

Muhammad Ashraf Wani, a professor of History at the University of Kashmir, said that the Muslims in Jammu "do not talk about it because they fear for their survival".

"This is the worst tragedies in the history of Kashmir but unfortunately no one talks about it because the state doesn’t want anyone to remember it," Wani said.

Khurram Parvez, a noted human rights defender in Kashmir, told Al Jazeera that the perpetual conflict in Kashmir has its roots in 1947 massacre. "It is deliberately forgotten. Actually, the violence of that massacre in 1947 continues. Those who were forced to migrate to Pakistan have never been allowed to return," he said.

Five days after the Jammu killings, tribal militias from Pakistan’s North Western Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), where many of the Jammu Muslims had family ties, invaded Kashmir.

As the army of tribesmen rushed to Kashmir, the army of Dogra monarch fled to Jammu. The king Hari Singh signed the instrument of accession with New Delhi, which sent its army to fight the tribesmen.

The fighting of several weeks between tribesmen and Indian Army eventually led to first India-Pakistan war. When New Delhi and Islamabad agreed to a ceasefire in January 1948, the formerly princedom of Jammu and Kashmir was divided between the two countries.

The conflict born in 1947 has led to three wars between India and Pakistan. An estimated 70,000 people have been killed in the violence in past three decades since the armed revolt against Indian rule broke out in the region in 1989.

#india#pakistan#kashmir#dogra#hari singh#jammu#jammu and kashmir#muslims#new delhi#indian news#news#war#article 370

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get to Know the Filmmaker: Madhusree Dutta

Madhusree Dutta is one of the seminal feminist filmmakers in India, using documentaries to not only shine a line on marginalized communities and groups in India but use innovative film techniques in her documentaries.

Her biography states:

Madhusree has always been attracted towards the spatial and cultural labyrinths of the urban milieu. Migration and movement surfacing through various fluid cultural notes - railways as a metaphor for those conjunctions; feminisation process of the urban poor, communalisation of the identities, classification of resources and all contemporary forms to represent that status quo; transgressions of all kinds and forms at various scales engage and inform Madhusree’s works.

Dutta has uploaded several of her works to youtube and vimeo to watch:

Made in India

A rural artist paints her autobiography, Bollywood movie icons’ images get erased after the weekly run of the film, the national flag flutters on 150 kites, installation artist paints pop icons on the rolling shutters of shops, religious icons jostle for attention with plastic flowers on the vendor’s cart, metaphors of life cycle adorn the mud wall of a home, neighborhood boys craft the tale of WTC and the sale of toy planes goes up. Symbols of nationalism become a fashionable commodity.

I Live in Behrampada

The 45-minute film was shot after the first phase of the 1992-’93 riots that took place in Mumbai in the wake of the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya by Hindu mobs. I Live in Behrampada examines the internal dynamics of people living in the slum in Mumbai’s Bandra suburb and their relationship with the people living around the neighbourhood (x).

Memories of Fear

Concentrates on how girls from a very young age, are socially conditioned into different kinds of fear, concrete, abstract, and other kinds, which make them grow into suppressed individuals and complex personalities (x).

Imaginary / Tactile: Women Viewing Cinema

From Here to Here

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

While everyone is busy arguing about CAA, NRC, NPR, etc.. RBI (without making official press release) announced that Muslims and Aethist who migrated from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan will not be allowed to buy property in India..

Basically meaning, that if you want to register your property now, you will have to disclose your religion + if you are Muslim, then you will have to prove that your family has no relationships from any of the three countries. Similar rule has been proposed for opening bank account now...

The Wire: Financial Accountability Watchdog Condemns RBI's Attempt to 'Communalise Banking'.

https://thewire.in/banking/rbi-fema-kyc-religion

1 note

·

View note