#cleobis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Carl Ernst von Stetten (1857–1942)

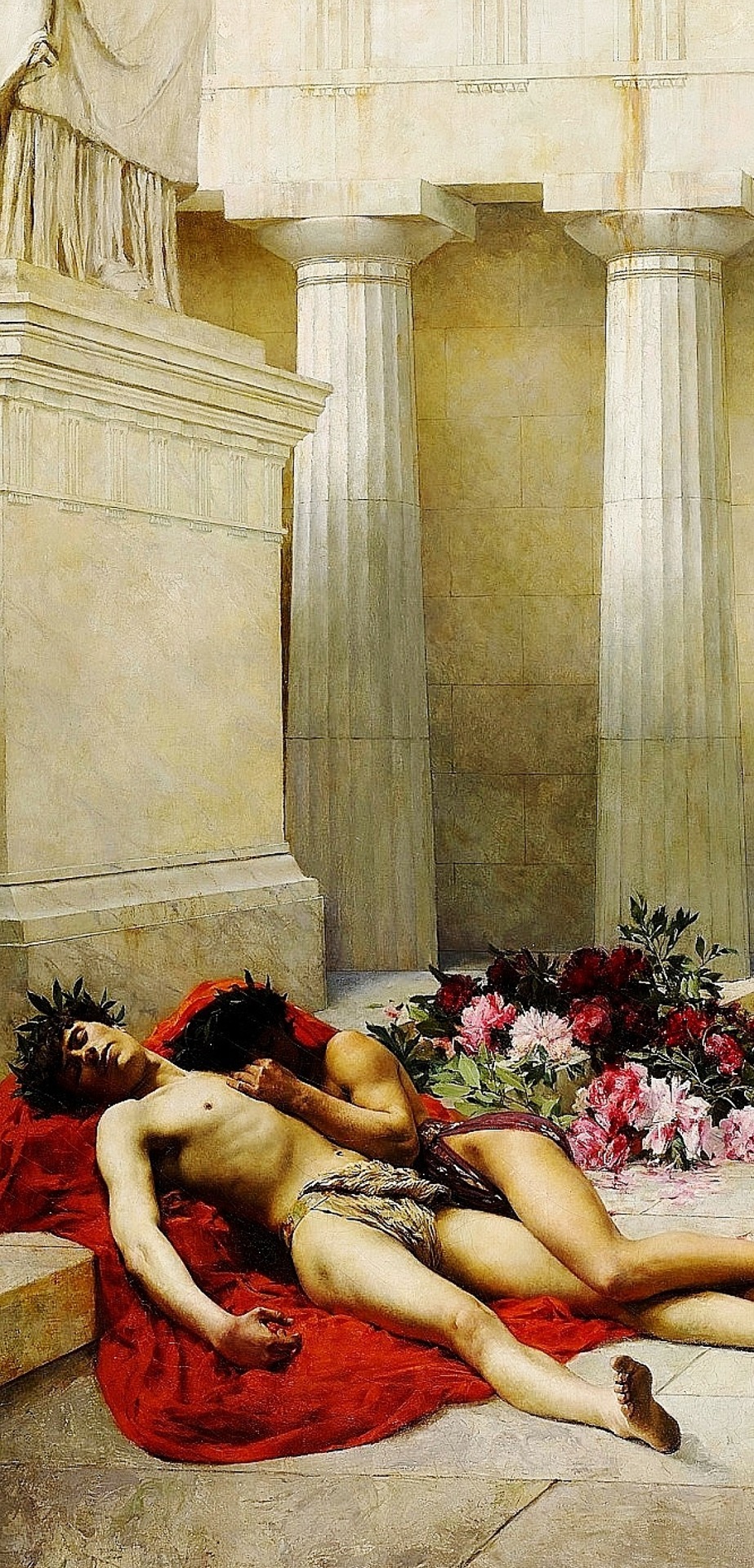

Cleobis and Biton, 1884, detail.

748 notes

·

View notes

Text

The meaning and function of the Cleobis and Biton tale in the Croesus logos of Herodotus' Histories

youtube

Franco Basso on the meaning and function of the Cleobis and Biton tale in the Croesus logos

In this final talk from the summer 2024 edition of the Herodotus Helpline series, Franco Basso (Cambridge) explores the significance of the phrasing 'Phthoneros te kai tarachodes'. in Herodotus' story of the Argive brothers Cleobis and Biton (1.31), considered by Herodotus' Solon to be the second most blessed individuals he knew of after the Athenian Tellus. The talk also considers the wider importance of this short passage in Herodotus' account of the Lydian king Croesus.

From the youtube channel of Herodotus Helpline

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the story, Solon tells of how these Argive brothers took their mother named Cydippe, a priestess at the temple of Hera, to a festival for the goddess to be held in town. When their mother's oxen could not be found, the brothers yoked themselves to their mother's cart and drove her the six miles to the temple.[2] Having arrived at the festival, the mother prayed for Hera to bestow a gift upon her sons for their strength and devotion, which Hera listened and rewarded the sons. When the prayers and the sacrifice were over, Kleobis and Biton fell asleep in the temple and never woke up, which was the gift Hera bestowed on the boys: allowing for them to die. To honor the two brothers, the people of Argos dedicated statues of them to the temple of Apollo at Delphi, allowing for these statues to be seen as funeral memorials.

Upon hearing this story, Solon's advice to Croesus were “the uncertainties of life mean that no one can be completely happy.” Either one can experience the joys of having continuous prosperity, much like Tellus, or one can experience a life of death, which can be granted as a reward like it was to Kleobis and Biton. The lesson of the legend is to showcase that those who live a moderately happy life are shown to have a glamorous death. It also shows that "it was better for a man to die than to live."

Cleobis and Biton. 1884. Carl Ernst von Stetten German 1857-1942. oil/canvas. Sotheby’s Jan. 2023. http://hadrian6.tumblr.com

644 notes

·

View notes

Text

CARL ERNST VON STETTEN-1857-1942 Cleobis and Biton 1884-detail.

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cleobis and Biton

Two over-life-size Archaic kouroi (6.5 ft / 2 m) are housed at the Delphi Museum, and date to c. 580 BCE. Their names (Cleobis and Biton) are actually written on their bases, and the sculptor is given as Polymides of Argos: such inscriptions are unusual for this early date. They are ideal representations of strength and masculinity, in the Peloponnesian style.

The myth of Cleobis and Biton is told in Herodotus, 1.31. The two sons carried their priestess mother by cart in place of oxen. They travelled from Argos to the Argive Heraion, some 45 stadia.

At their arrival they collapse, and their mother prays to Hera that they may die in their sleep - the easiest death for mortals. Herodotus tells this story as part of Solon's answer to Croesus' questioning as to who the happiest man is.

μετὰ ταύτην δὲ τὴν εὐχὴν ὡς ἔθυσάν τε καὶ εὐωχήθησαν, ἐν αὐτῷ τῷ ἱρῷ οἱ νεηνίαι οὐκέτι ἀνέστησαν ἀλλ᾽ ἐν τέλεϊ τούτῳ ἔσχοντο. Ἀργεῖοι δὲ σφέων εἰκόνας ποιησάμενοι ἀνέθεσαν ἐς Δελφοὺς ὡς ἀριστῶν γενομένων.

After this prayer they sacrificed and feasted. The youths then lay down in the temple and went to sleep and never rose again; death held them there. The Argives made and dedicated at Delphi statues of them as being the best of men.

Herodotus, 1.31.5

(the full passage in translation and original can be found here)

Perhaps, in this case, there is some truth to Herodotus' stories…

Continue reading...

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay what's the meaning behind the Ganymede and Zeus myth? Like what's the symbolism of it?

In my opinion for starters it symbolizes the divine meaning of beauty. Ganymedes was known for being incredibly beautiful and caught Zeus's eyes because he was beautiful. The word for "beautiful" in greek at that time was "καλός" (kalόs) giving also the word used for older greek κάλλος (k'allos) which means "beauty". That very same word nowadays in Greek means "good" so literally became a virtue rather than a description of a person so the evolution of our language kinda is a wink at how important beauty and health was in antiquity.

Beauty and health of the body was very important in ancient Greece and were considered divine properties. In fact the ideal man in antiquity, according also to writings like Xenophon was called "Καλός καγαθός" (Beautiful and Virtuous at heart). The aspet of beauty and youth also play their part here speaking on how important youth and strength was for the ancient greeks

Symbolically Ganymedes was chosen and taken by Zeus (aka elevated to divinity) because he had the divine property of beauty and in one way the virtue as well. He was also young and youth and beauty go side by side as well as virtue is by n large linked to the age of youth where people do heroic or honorable acts. (similarly to the legend of the story of Cleobis and Biton, the two brothers that harnesed themselves to their mother's cart, Cydippe the priestess of Hera, and dragged her cart for miles and miles till she got to the temple to offer sacrifices for a elebration. Cydippe watched her sons almost become equivalent to gods in the eyes of her people that day and so she prayed to Hera to let them have a gift suitable for them now that they are at the top of their glory so no evil shall ever overshadow their glory. Hera heard her prayers and her sons went to sleep that day and never woke up. They died in their sleep peacefully in the most glorious moment of their lives and nothing ever overshadowed their name again)

Ganymedes when he is at the peak of his beauty is taken by Zeus and offered immortality; his beauty was immortalized when it was to its peaque. Also the way that he was immortalized was a sign of glory. Glory as I mentioned above is mostly linked in youth so Ganymedes receiving glory and honor as a young man, symbolizes how most of the time people achieve great things in their youth. Literally, for me at least, the myth of Ganymedes is the very representation of the ideal for Greeks Καλός καγαθός. Καλός Ganymedes already was aka "beautiful" so now he also became αγαθός aka "glorious" or "virtuous" and was loved by the gods for it aka by Zeus, the king of gods himself.

On a sadder note I could take another step and speak on how usually deification of humans happens by n large after their death so Ganymedes being lifted to heavens could also be a symbol of how often young men die young but take this with a grain of salt

I hope you got some answers for your question here ^_^

#katerinaaqu answers#greek mythology#zeus#ganymede#zeus and ganymede#greek mythology symbolism#Greek Mythology#myths with zeus#hera#zeus and hera

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The story of Cleobis and Biton or The gift of everlasting sleep

#yellowjackets#jackie taylor#natalie scatorccio#greek mythology#one day i'll get to the actaeon bit!!#web weaving

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tasked with translating a version of the story of Cleobis and Biton for my latin homework, and let me tell you what a fascinating experience that was as someone unfamiliar with the story

"She... she does what now. That can't possibly be right. Did I translate it wrong? That can't possibly be the actual story. Surely this is some poetic phrasing that I'm not grasping—*checks wikipedia*—oh no okay Juno is just for real an asshole for no reason

#'hey juno my sons worked really hard to help me get here so i could pray to you. can you give them a blessing instead of me please'#'yeah sure no problem' *kills both of them instantly* 'now theyll never be unhappy again lol'

0 notes

Text

My rotten soldiers

(probably the reason I favor Delphi despite it all)

#cleobis & biton#if you think they’re the dioscuri you can fuck clean off#no wait i’m sorry come back#we can talk politely about it over coffee don’t leave#anyway kouroi#THE kouroi#my sons#delphi#delphi museum

0 notes

Text

The figure of ἐπιστάµενος (a person with knowledge) and the relationship between poetry and history in Herodotus

"To begin with a striking internal parallel, Herodotus introduces the Athenian lawmaker and poet Solon into his narrative as one of several Greek wise men or sages, σοφισταί (29.1), who visited the court of the Lydian king Croesus in Sardis. Before Solon has demonstrated his disregard for the king’s wealth, Croesus too makes much of the wisdom (σοφίη) that Solon has gained through his travels. However, when Solon proclaims his fellow Athenian Tellos and the Argive brothers Cleobis and Biton to be more prosperous than his fabulously wealthy host, Croesus demands to know the basis for Solon’s rankings, to which the Athenian replies (1.32.1):

ὁ δὲ εἶπε· Ὦ Κροῖσε, ἐπιστάµενόν µε τὸ θεῖον πᾶν ἐὸν φθονερόν τε καὶ ταραχῶδες ἐπειρωτᾷς ἀνθρωπηίων πρηγµάτων πέρι.

‘Croesus’, Solon replied, ‘you are asking me about human affairs, as one who knows how utterly resentful and disruptive [sc. of human prosperity] the deity is.’

Solon’s self-description as ἐπιστάµενος45 is underscored by the emphatic placement of the participle immediately after his direct address of the king. As I have argued elsewhere,46 the explication of this gnomic generalisation by the Herodotean Solon incorporates several references to surviving pieces of the historical Solon’s poetry, beginning with his statement that he sets the limit of a human’s life at 79 years (32.2 W2, cf. 27).

If we look beyond Herodotus, external parallels confirm the use of ἐπιστάµενος to describe the skill and wisdom of the archaic singer/poet. At Odyssey 11.367-8, Alcinous praises the arrangement (µορφή) and good sense (φρένες ἐσθλαί) that characterise Odysseus’ tale of his travails while traveling from Troy: ‘You have told your story in expert fashion, like a singer’ (µῦθον δ’ ὡς ὅτ’ ἀοιδὸς ἐπισταµένως κατέλεξας).47 Solon’s longest surviving poem (13 W2) contains a generic description of a poet as ‘instructed in the gifts of the Olympian Muses, expert in the full measure of lovely skill/wisdom’ (ἱµερτῆς σοφίης µέτρον ἐπιστάµενος, 52). The parallel with the most striking Herodotean resonance, however, occurs in four lines from the Theognidean corpus, describing the poet’s responsibility to his audience (769-72):

χρὴ Μουσῶν θεράποντα καὶ ἄγγελον, εἴ τι περισσόν εἰδείη, σοφίης µὴ φθονερὸν τελέθειν, ἀλλὰ τὰ µὲν µῶσθαι, τὰ δὲ δεικνύεν, ἄλλα δὲ ποιεῖν· τί σφιν χρήσηται µοῦνος ἐπιστάµενος;

The attendant and messenger of the Muses, if he should know Something extraordinary, must not be grudging of his wisdom, But must seek out knowledge, display it, and compose it. What good will it do him if he alone is knowledgeable?

The recurrent emphasis on the poet’s special knowledge/wisdom/expertise culminates in the pointedly deferred participle, ἐπιστάµενος. Robert Fowler calls special attention to the penultimate line, with its triple admonition to ‘seek out, display, and compose knowledge’.48 Fowler suggests that these activities comprise precisely what Herodotus means by that much-discussed phrase in the first clause of his opening sentence, ἱστορίης ἀπόδεξις. In Fowler’s own words, ‘[Herodotus] sought knowledge and, good Greek that he was, shared it publicly’.

In fact Fowler’s formulation fails to do justice to the specificity of this text, since by its criteria what Herodotus proves himself to be in sharing the results of his inquiries is not merely a good Greek, but more precisely a good Greek poet. In other words, at the end of his prologue—an unmistakably prominent juncture in his narrative—Herodotus not only invokes the precedent of the Odyssey but also, and more broadly, promises the kind of generalising insight into the nature of the human condition traditionally professed by poets. It is as if Herodotus anticipated Aristotle’s criticism in the Poetics (1451a–b) that history—and indeed, explicitly Herodotean history—is less philosophical than poetry because it tends to focus on specific past events rather than universal human truths.49 On the contrary: from the outset Herodotus frames his account of historical particulars as a manifestation of the sobering universal truth that human prosperity is fleeting. In other words, Herodotus brings to historical narrative a poet’s eye for an issue of fundamental importance, mankind’s place in the universe at large.50 This is also reflected in the tendency of prominent advisor figures in the Histories to utter gnomic generalities when offering counsel in the face of specific crises, as they warn their powerful interlocutors about divine resentment of human prosperity and mortal liability to misfortune (Solon to Croesus, 1.32); or the cycle of human affairs that prevents anyone from enjoying continual success (Croesus to Cyrus, 1.207.2); or the deity that cuts down whatever is outstanding and allows no one but himself to ‘think big’ (Artabanus to Xerxes, 7.10ε)."

From the article of Charles C. Chiasson "Herodotus' Prologue and the Greek Poetic Tradition", Histos 6 (2012), 114-143

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hera would never do anything bad to me; my brother and I literally just dragged our ailing mother to her shrine and she promised us a big rewar--*dies*

I want to study the people who say stuff like "I stopped worshipping the vengeful and hateful Christian god to worship Hera."

11K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Detail : Cleobis and Biton. 1884. Carl Ernst von Stetten German 1857-1942. oil/canvas. Sotheby’s Jan. 2023. http://hadrian6.tumblr.com

686 notes

·

View notes

Text

cat called cleo as in short for cleopatra but i secretly call her cleo as in short for cleobi, because i love being pretentious <3

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thomas Blanchet, Cleobis and Biton (c. 1660) Nicolas-Pierre Loir, Kleobis and Biton (c. 1649) Adam Müller, Kleobis and Biton (1830)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

idk something about the end of spn has me thinking about the story of King Croesus from Greek history/mythology. (adapted from my own translation)

According to Herodotus, Croesus was the king of Lydia for 14 years (and 14 days) before his downfall. The story starts with the visit of Solon, an Athenian scholar who was well respected, especially in regards to his travels. Croesus hosted Solon in his palace and paraded him around to show off all his wealth and accomplishments. In Ancient Greek, there is a word “ολιβος” (olibos), which which is sort of a hard word to translate, and it means something like happy or blessed or prosperous. Anyway, because of Solon’s worldliness, Croesus asked him who, out of all the men he has ever met or heard tales of, is most ‘olibos’ of all.

Solon answered him that it was Tellus the Athenian, and when questioned why, he said this: “Tellus had a well off city and good and beautiful children, and he lived to see many children born to all of them, and all lived to adulthood. He was also well of in the world of goods and money, and his death was radiant. He died heroically and honorably on the battlefield, and his public funeral occurred on the very spot where he fell.”

Croesus had of course asked expecting himself to be named the most ‘olibos’, so he asked who was next after Tellus.

Solon responded, “Cleobis and Biton, for they were blessed in wealth and strength of body. In particular there is this story of their death: their mother was an attendant in the Festival of the Argive Hera, so it was imperative that she make it to the city for the festival. However, their oxen had not made it back from the field in time, so Cleobis and Biton went under the yolk themselves and brought their mother to the city on their wagon. After arriving, they were honored by all at the festival and a best end of life came to them. The gods showed it plainly that in these matters, it is better for men to have died rather than live. After their death, they were honored with statues at the temple.”

Becoming angry Croesus said, “My Athenian guest, are you seriously casting aside our prosperity, so that you make us not even on par with the worth of private men?”

And Solon said to Croesus, “In a great amount of time, there are many things people do not wish to see, and many more things they do not wish to suffer, but to me you both appear to be to be very wealthy and the king of many men, but I cannot answer if you are most ‘olibos’ yet, not until I learn that you have died well. For the wealthy one is not more ‘olibos’ than the one having enough for the day.”

Croesus was not thrilled about what he had to say, and Solon went on his way. Croesus would not soon forget these words. Despite his attempts to prevent a prophecy, his son dies by spear in a boar hunting accident. After mourning the death of his son, he declares war against the persians and soon finds himself and his city besieged.

After ruling for 14 years and being besieged for 14 days, Croesus’s city was taken and he was placed upon a funeral pyre by the Persian king Cyrus. Up on the pyre, having lost his son and his kingdom, Croesus remembered the words of Solon, that no one is ‘olibos’ in life, and he wept.

Once the pyre was lit, Croesus prayed to Apollo to save him, and out of a windless calm and a cloudless sky, rain suddenly poured down on Croesus, extinguishing the flames.

And in thinking about Dean’s death in the finale, I can’t help but to think of Croesus on the pyre, remembering that the gods made it so that it is better for humans to be die heroically than remain alive, and that no one living can ever be happy or prosperous, because they just might lose it all before their death. Of course Dean couldn’t be happy in life, because he always had something to lose, and when he lost Cas, he didn’t have any reason to pray that someone come save him from a pyre of his own, pinned on that piece of rebar in that barn.

#classicist on main#been thinking on this one for a while#pls reblog this i worked hard#dean winchester#castiel#spn#supernatural#supernatural meta#spn meta#destiel#deancas#debeaux talks

15 notes

·

View notes