#claude vignon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Claude Vignon

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

En l'honneur du Nouvel An Chinois qui nous fait passer dans l'Année du Serpent, en voici quelques-uns !

Ici, les serpents de Salammbô et de Cléopâtre :

Marseille, MuCEM, expo "Salammbô - Fureur ! Passion ! Éléphants !"- Carl Strathmann - "Salammbô"

MuCEM - expo "Pharaons Superstars !"- Henri Ducommun du Locle - "Cléopâtre"

Louvre-Lens - expo ''Champollion - La Voie des Hiéroglyphes'' -François Barois - "Cléopâtre mourant"

MuCEM - expo "Pharaons Superstars! "- Claude Vignon - "Cléopâtre se donnant la mort"

#serpent#année du serpent#nouvel an chinois#aspic#salammbô#cléopâtre#marseille#louvre-lens#MuCEM#salammbô - fureur ! passion ! éléphants !#pharaons superstars !#champollion#champollion la voie des hiéroglyphes#carl strathmann#henri ducommun du locle#suicide#françois barois#claude vignon

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un peu de Provence

View On WordPress

#Agar#Alexandre Desgoffe#Alexandre Manjaud#Amable Lombard#Anaxagore#Antiochus#Camille Bouchard (1889-1973)#Charles Ginoux#Claude Vignon#Dante#Divine comédie#Draguignan#Emmanuel Lapouge (peintre)#Esterel#Félix Ziem#François Ier#Frédéric Montenard#Gabriel Guay#Georges Chénard-Huché#Hécube#Julien Gustave Gaillardin#Louis Boulanger#Michel François Dandré-Bardon#Moustiers Ste Marie#Périclès#Philippe de Champaigne#Prosper Barrigue de Fontainieu#Provence#Révolte des Maccabées#Rembrandt

0 notes

Text

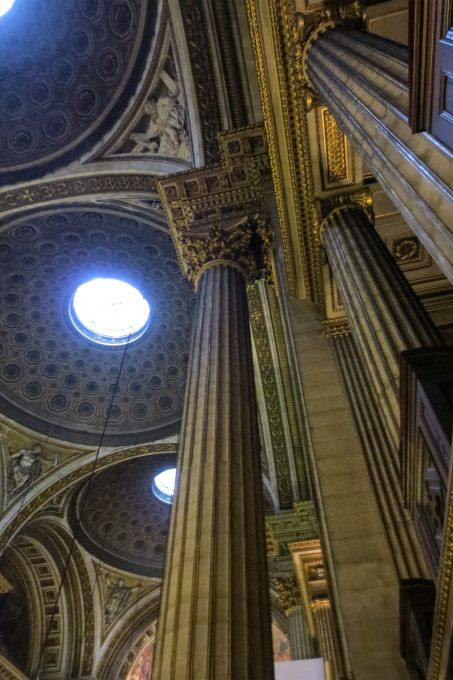

In 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte would sign the decree for the construction of a temple in honor of the glory of the French army: “...it will be the most august and the most imposing of all...Reward with which the victor of kings and peoples "The founder of empires rewards his army."

A competition was called and the project of the architect Pierre-Alexandre Vignon was chosen for the construction of the Church of the Madeleine, Paris. Today considered one of the best examples of neoclassical architecture, its model was the Maison Carré (Roman era).

Neoclassicism disappears when you enter its interior, where the baroque surrounds the walls, only the coffered vaults remind us of the majestic Pantheon of Agrippa.

Its construction lasted eighty-five years due to political instability in France at the end of the 19th century 18th and early 19th. The political changes of the time caused its use to be modified several times. It was about to be a railway station. Between 1835 and 1837, Jules-Claude Ziegler painted “L'Histoire du christianisme” in the apse and between 1835 and 1857, the Paris-based Italian sculptor Marochetti carved the figure of Mary Magdalene for the altar.

One of the most important pieces of the church is the organ from 1846, the work of Aristide Gavillé-Coll.On the outside, the 52 Corinthian columns give it an imposing appearance and support the pediment, the work of the sculptor P. Lemaire, which represents The Last Judgment, which was made in 1833.

Fhoto ©️Buiron Christophe

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vigilance

Artist: Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (French, 1824-1898)

Date: 1867

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Collection: National Galleries' Scotland, Edinburg, Scotland

Description

Puvis de Chavannes’s muted palette and flat, decorative forms had an important influence on French symbolism in the late 1880s and 1890s. This is a version of La Vigilance (Vigilance) which was one of four decorative panels commissioned by the writer and sculptor Claude Vignon, alias Noémie Cadiot, for her house at 148 rue de la Tour in Paris. The mural scheme featured four allegorical figures intended to represent the principal elements of artistic creation: Vigilance, Meditation, History and Fantasy. The flame, which Vigilance holds aloft against a new dawn, symbolises the moment of artistic inspiration.

#painting#oil on canvas#symbolism#vigilance#allegorical figure#pierre puvis de chavannes#french painter#flame#desert landscape#female figure#mountains#sky#19th century

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claude Vignon (Born Marie-Noémi Cadiot), ca, 1828/32-1888

Daphne converted into laurel, 1866, mabre, 210 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille, France

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

La circuncisión de Claude Vignon (Tours, 1593 - París, 1670) Óleo sobre tela H. 82 cm.; L. 113 cm. Inv. 1994-4-1

Información e imagen de la web del Museo de Bellas Artes de Tours.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flourishing with Herodotus

"FLOURISHING WITH HERODOTUS

by royalhistsoc | Jul 13, 2023 | General, Guest Posts, History and Human Flourishing | 0 comments

In this second post of the ‘History and Human Flourishing’ series, Suzanne Marchand explores the contemporary value and relevance of Herodotus in historical teaching and methodology. Though often overlooked in favour of a ‘scientific’ approach advocated by nineteenth-century acolytes of Thucydides, Herodotus and his Histories remain a rich — and much needed — guide to history as the story and study of human behaviours. In this post, Suzanne considers Herodotus’ appeal and lessons for historians today.

This post is the second contribution to the Society’s 3-part ‘History & Human Flourishing’ blog series. The first, by Darrin M. McMahon, explores the often-neglected study of the history of human happiness.

There is, in my view, too much Thucydides in our histories and perhaps in our hearts today. This is partly the fault of the nineteenth century, when he became exemplary of the ‘right’ kind of historian: cynical, disciplined, grimly determined not to waste time on trifling matters. Power, for him — in a way oddly reminiscent of the also still-pervasive work of Michel Foucault — is what drives history and defines all human interactions, regardless of what anyone might say. So much have we accustomed ourselves to this cynical view that even the cultural historians among us struggle to wrest ourselves from its grip.

This is why it might be healthy to recall that Thucydides devised his historical principles to demonstrate his superiority to an already famous predecessor — one who has always, also, had his advocates, even if his reputation suffered a tremendous blow in the age of Leopold von Ranke. Pace the military strategists and the philosophers of international relations, we historians do not have to be eternal Thucydideans. Indeed, in doing so we might find new means of flourishing by embracing some of the richer and weirder methods of writing — and especially of teaching — history and of conceiving human nature that Thucydides renounced.

Herodotus gave us so much broader a picture of the calculated and crazy things we do, how rulers succeed and screw up, how cruel and clever we can be.

The spurned predecessor to whom I refer to is, of course, Herodotus, whose Histories relate, in shaggy dog fashion, the cosmopolitan backstory and then the unfolding of the Persian Wars.

It would wrong to insinuate, as Thucydides does in the famous passage at 1.122, that Herodotus wrote merely for entertainment, and did not care about truth, or to assert, as would Plutarch five centuries later, that Herodotus maliciously skewed his story. There are entertaining and improbable stories in The Histories, such as the rescuing of the poet Arion by a sympathetic dolphin, and plausible but probably exaggerated ones, like the water management projects of Assyrian Queen Nitocris (1.185). But even more, there is with Herodotus a rich variety of life, women as well as men (by one count, only six are mentioned in Thucydides, to 370+ in The Histories). To these we may add animals, gods, rivers, kings, and others, motivated not just by self-interest or the yearning for power, but by dreams, vanity, misunderstanding, passion, stupidity, pride, or simply unknown forces the historian cannot fathom.

In Book 6 (6.129-130), Herodotus tells the story of Hippokleides, set to make an advantageous marriage, who drinks too much at his engagement banquet, resulting in a bout of ribald dancing during which, it is suggested, he reveals his privates. When his prospective father-in-law tells him that he has danced away his good fortune (the original ‘balls up’), the merry-maker’s response — still used as an adage in modern Greek — is ‘Hippokleides doesn’t care!’ Don’t we all recognize a Hippokleides in our lives, perhaps (at least occasionally) in ourselves?

Image 1: Claude Vignon, “Croesus showing Solon his Treasure” (1630s) Wikimedia commons

Cicero termed Herodotus the ‘father of history,’ but in the same breath bracketed him with Theopompus, known for his long-winded digressions and his innumerabilies fabulae. What Cicero didn’t note was that Herodotus’ approach had a purpose: to convey a great deal of information and insight into human behaviour, at home, and abroad. Over the centuries, thousands of Herodotean fact-checkers have attempted to verify his information, sometimes finding him mistaken, but often recognising ways in which he was interestingly (if not perfectly accurately) right — about the Egyptian labyrinth, for example, or Persian horse lore.

But an even better reason for teaching Herodotus, or better teaching like Herodotus rather than, unrelentingly, like Thucydides, is that Herodotus gave us so much broader a picture of the calculated and crazy things we do; how rulers succeed and screw up, how cruel and clever we can be. Of course, his was also a very Greek way of seeing the world, and Herodotus’ stories about the despots of the East must be read with this in mind. But as he says in the very first line of his history, his intent throughout is to record for posterity the great deeds of the Greeks and the Persians, as well as to explain why they fought. I believe that Herodutus meant it, as he meant to show, too, that Egypt was full of wonderous things; that Scythia was home to brave if barbaric tribes; that some Greeks were cowards and tyrants; and others, at least some of the time, ingenious and courageous.

What if we accepted a bit more of the Herodotean worldview, and his approach to engaging with the past?

Herodotus certainly did care about human happiness. One of his most beloved tales, that of Solon and Croesus (1.29-33), goes right to the heart of the issue. As Herodotus relates, during travels he initiated to avoid having to repeal laws he imposed in Athens, Solon visited the extraordinarily wealthy king of the Medes. During his visit, the proud king shows Solon his riches, whereupon Solon launches into a story, the moral of which is that as fortune is ever changeable, one should not count oneself happy until one rests on one’s deathbed, surrounded by adoring family and friends.

The story acts as a prophecy, as Croesus will soon fall prey to an epic form of pride inciting a fall. Croesus will recall Solon’s admonition as he is about to be burnt on a pyre after the conquest of his kingdom (1.86). This is no mundane proverb, and it teaches an important, perhaps better, lesson than most Disney movies: one can and should try to live a good, honourable life. But one might fail, and not necessarily because of a ‘fatal flaw’ — fortune can simply deal a bad hand. Isn’t this a sensible way for us to conceive of our fellow humans and their flaws? Sometimes the flaws get you, sometimes you simply have bad luck (which might be structurally conditioned). If the seventeenth century read the story as a warning against enjoying worldly riches (see image 1 above), we might read it as an admonition not to judge people by their fates, and to take seriously the view that there, but for the grace of God, or fortune, go I.

Image 2: Karl Gottfried von Lück, ‘Tomyris with the Head of Cyrus’, Frankenthal Porcelain Manufactory, c. 1773; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.

Most especially, I would like to advocate for more Herodotean teaching in the classroom … Environmental history has spurred us to put nature and animals in the picture, as did Herodotus; he would approve of discussing commerce and foodways.

What if we accepted a bit more of the Herodotean worldview, and his approach to engaging with the past? I don’t think scholarly history can do this entirely, but it would be a relief to escape the unrelenting cynicism of the Thucydidean-Foucauldians. But most especially, I would like to advocate for more Herodotean teaching in the classroom. College students have endured all too much ‘high’ political and military history in high school, and find more engaging lectures on ‘everyday life,’ whether in discussions of colonial Salem, or Roman Britain, or Nazi Germany. Environmental history has spurred us to put nature and animals in the picture, as did Herodotus; he would approve of discussing commerce and foodways.

Why not indulge in a few good stories, such as that of Queen Tomyris, who avenged her army’s slaughter at the hands of Cyrus by having him decapitated and his head dipped in a bag of blood? Herodotus told this story (1.212), and it was so memorable that even when his Greek text was lost to the West, medieval and early modern writers (including Shakespeare) knew and repurposed it; eighteenth-century porcelain makers, too, recreated it (see image 2). The story may well be apocryphal, but these too can occasion good teaching moments. Let’s see what we can do to make college history more Herodotean. Even if it won’t save us from the disdain of an increasingly presentist culture, at least, like Hippokleides, we might enjoy a last binge.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Suzanne Marchand is Boyd Professor of European Intellectual History at Louisiana State University. Her current research projects include a history of Herodotus’ readers from 1700 to the present, tentatively titled Herodotus and the Instabilities of Western Civilization. Her wide-ranging research interests include classical studies, art history, anthropology, history, and theology in modern Europe, as well as in the history of porcelain and related topics in the history of material culture and consumption in Central Europe.

Suzanne’s publications include the article ‘Herodotus and the Fate of Universal History in Nineteenth-Century Germany’, Journal of Modern History (forthcoming, 2023) and the monographs Porcelain. A History from the Heart of Europe (Princeton UP, 2020) and German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Race, Religion, and Scholarship (Cambridge UP, 2009).

Her essay, ‘Flourishing with Herodotus’ appeared in Darrin McMahon’s edited collection, History & Human Flourishing (OUP, 2023)."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎨 hands at the museum of fine arts, boston.

claude vignon's david / michaelina wautler's self-portrait / vincent van gogh's postman joseph roulin

#art#art history#paintings#studyblr#art student#museums#museum studies#aya rambles#renaissance#post impressionism#impressionism#portrait#realism#dark acamedia#academia#light academia#grey academia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claude Vignon

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Much Is Too Much? (1 Kings 4:20-28)

A dimension of any rule or government is to realize that – with any sort of success, security, and wealth – there is always a dark underbelly to it.

King Solomon’s court, by Claude Vignon (1593-1670) The people of Judah and Israel were as numerous as the sand on the seashore; they ate, they drank and they were happy. And Solomon ruled over all the kingdoms from the Euphrates River to the land of the Philistines, as far as the border of Egypt. These countries brought tribute and were Solomon’s subjects all his life. Solomon’s daily…

View On WordPress

#1 kings#1 kings 4#economic system#economy#ethics#exploitation#faithfulness#first kings#god&039;s law#government#holy scripture#injustice#jesus christ#justice#king solomon#morality#oppression#sermon on the mount#social system#success#wealth

0 notes

Text

El simbolismo de la Naturaleza: Lirios

Los lirios recibieron su nombre de la diosa griega Iris, quien transportaba las almas de las mujeres al mundo subterráneo y personificaba al arcoiris. En botánica, el género Iris incluye a los lirios, cuyos colores variados evocan al arcoiris.

En la antigüedad griega, el lirio simboliza belleza y amor, de ahí que en las futuras representaciones clásicas y neoclásicas de ninfas y deidades femeninas, como Flora, estuvieran presentes. Las tumbas de las mujeres eran adornadas con ellos. También son comunicación divina, esto relacionado con la función de Iris como mensajera de los dioses.

Aparecen frecuentemente en el Cantar de los Cantares, texto fechado alrededor del siglo V a.C., aunque atribuido al rey Salomón. En él se hacen las siguientes menciones:

"Yo soy la rosa de Sarón, y el lirio de los valles."

"Como el lirio entre los espinos, así es mi amiga entre las doncellas."

"Mi amado es mío, y yo suya; él apacienta entre los lirios."

"Tus dos pechos, como gemelos de gacela, que se apacientan entre lirios."

"Sus mejillas, como una era de especias aromáticas, como fragantes flores; sus labios, como lirios que destilan mirra fragante."

"Mi amado descendió a su huerto, a las eras de las especias, para apacentar en los huertos, y para recoger los lirios. Yo soy de mi amado, y mi amado es mío; él apacienta entre lirios."

Los lirios se hallan en las representaciones de la Anunciación como flor o viga florida, sostenida por María, el arcángel Gabriel o en un jarrón. En el mundo cristiano, son símbolo de los símbolo de los castos; transmiten pureza, inocencia, virginidad y luz. Santos como San Luis de Gonzaga y San Antonio de Padua llevan. Además de la rosa, el lirio es una de las flores de la Virgen María. Su asociación deviene tanto del Cantar de los Cantares como de las Sagradas Escrituras, particularmente de los evangelios de Mateo y Lucas:

Mateo 6:28 - 29

"Y por el vestido, ¿por qué os afanáis? Considerad los lirios del campo, cómo crecen; no trabajan, ni hilan; pero os digo, que ni aun Salomón con toda su gloria se vistió así como uno de ellos."

Lucas 12:27 - 28

"Considerad los lirios, cómo crecen; no trabajan, ni hilan; y os digo, que ni aun Salomón con toda su gloria se vistió como uno de ellos. Y si así viste Dios la hierba, que hoy está en el campo, y mañana es echada al horno, ¿cuánto más a vosotros, hombres de poca fe?"

Cuando el lirio es morado, simboliza la humildad de María. La Sibila de Cumas, quien vaticinó el nacimiento de Jesús, también lleva un lirio.

Luis VII adoptó el lirio en su emblema durante las cruzadas y, así, su nombre evolucionó de "flor de Luis" a flor de lis, cuyas tres hojas simbolizan la verdad, la sabiduría y el valor.

www.tarotdeana.tumblr.com

Imágenes:

"Flora", por Claude Vignon.

"Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose" por John Singer Sargent.

"La Anunciación", por Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Tríptico de la Anunciación, por Robert Campin.

Lee mitos griegos aquí.

Lee mitos coreanos aquí.

Lee mitos japoneses aquí.

#tarot#cartomancia#tarot reading#ocultismo#ocultista#tarot cards#witchcraft#brujería#artes ocultas#cosas de brujas#lilies#lirium#lirio#lirios#flores#simbolismo#symbolism#simbologia#simbolos#arte

1 note

·

View note

Text

Claude Vignon, Saint Jerome in His Study, c. 1620-1630

1 note

·

View note

Photo

È PIÙ SACRO VEDERE CHE CREDERE - UCCIDERE LA LETTERA

Per salvare dalla catastrofe il mondo non serve a nulla salvare tutte le parole che lo compongono: serve solo salvare il loro significato. La lettera, afferma san Paolo, uccide: e allora per salvare il mondo bisogna uccidere le lettere di ogni parola; rompere fino al midollo ogni parola, e liberarne numinoso il significato.

Nell’immagine, “San Paolo apostolo”, olio su tela dipinto da Claude Vignon nel 1622-24, conservato presso l’Harvard Art Museum di Cambridge, in Massachusetts (foto © President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Testo di Pier Paolo Di Mino.

Ricerca iconografica a cura di Veronica Leffe.

https://www.libroazzurro.it/index.php/note/questo-visibile-parlare/247

1 note

·

View note

Text

Claude Vignon, 1593-1670

The Rape of Proserpina, n/d, oil on canvas, 63x77 cm

Private Collection

19 notes

·

View notes