#cladogram

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

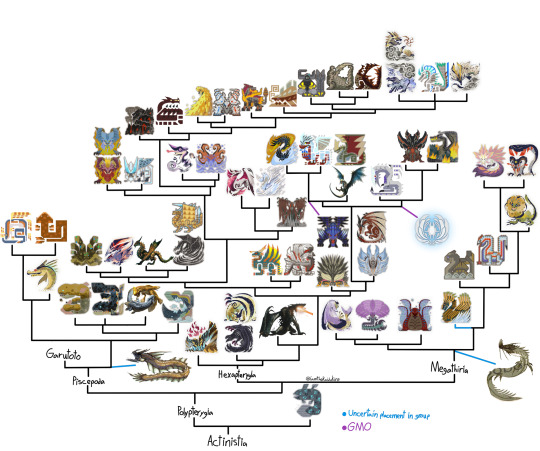

The new Polypterygia tree!

Not a whole lot changed outside of species being added. But piscine wyverns finally got a scientific name and Somnacanth has its own family of leviathans. Because this is just building off the last iteration, there is still fanon and recontextualizing and reworking many outlandish traits some of these monsters have and basically giving some of canon/what some of the hunters guild tells us the middle finger for the sake of more interesting theories.

Once again thanks to @mayfly0678 for the name “Polypterygia” and Lizardwizard for the spore theory.

And of course, here’s the almost 20,000 word google doc to go with it.

Now I have to do the same thing with bird and flying wyverns, except I have to make a document from scratch for it… ughhh

#monster hunter#speculative biology#speculative evolution#monsterhunter#monhun#monster hunter biology#elder dragon#piscine wyvern#leviathan#taxonomy#phylogeny#phylogenetics#cladistics#speculative zoology#Cladogram

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cladogram of rattiles in the Middle Temperocene.

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#cladogram

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

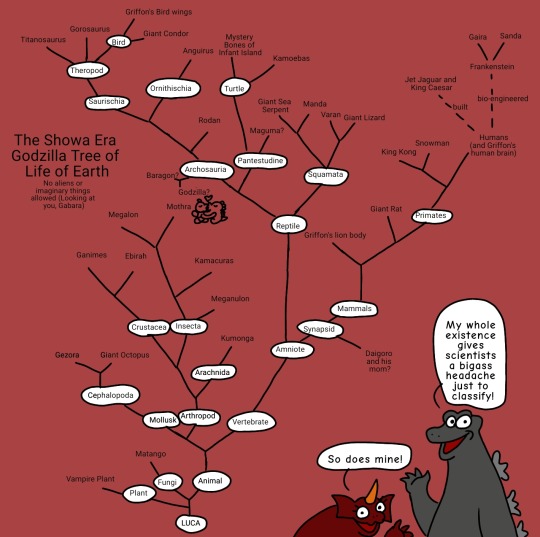

The Tree of Life with Showa Godzilla Monsters

Did this for fun (except when Godzilla, Baragon and Maguma came, they were HARD to classify). Keep in mind this is strictly real and terrestrial Kaiju, so no Ghidorah or Gabara.

#Godzilla#toho monsters#kaiju#kaiju art#taxonomy#cladogram#ゴジラ#tokusatsu#digitalart#mothra#king ghidorah#except no he isn't here#rodan#anguirus#baragon#king kong

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm so mad.

I was looking into tyrannosaur family trees, as one does, and was all like, hey, Tyrannosaurus and Tarbosaurus are considered sister taxons despite being on opposite sides of the world, what gives? How have we all missed this crucial fact!

I was thinking about it the past few days, and decided to make a passion project where I remade the tyrannosaur family tree with more intake from geography and what biology we had. Today I started it and was looking into papers, and then I remembered something. Beringia. The landmass that was once in place of the Bering Strait. It wasn't just open for migrations during the human migrations, but also in the Cretaceous period.

My passion project was ruined because I forgot about thE BERING STRAIT HBJGVHJHGVFHJHKCS

#tyrannosaurus rex#tyrannosaurus#tyrannosauroidea#tyrannosaurid#tyrannosaurs#tarbosaurus#tarbosaurus bataar#tyrannosaurus mcraeensis#phylogeny#phylogenetic trees#phylogenetic tree#phylogenetics#cladograms#cladogram#science#earth science#earth sciences#paleontology#paleontologist#aspiring paleontologist#this is why I will never be a paleontologist like I want to be#I'm so dumb#dumbass#dumbass scientist

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to do more aline stuff but I have other stuff to do so have the cladogram of all the clades so far.

Have a big boi so you can get an idea of the life forms in the right side of the cladogram

#speculative biology#speculative evolution#spec evo#alien life#alien planet#Aline#Aline 24-k#megapterygiostoma#alien animal#alien cladogram#cladogram#clade#family tree#biology#spec bio

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh hey i forgot abt this again but heres the finale of the cladogram series (for now teehee). The rest can be found HERE

The Radapillupods represent the final major group of Radiathopods. And hold some of the most derived orders of species seen on Irou. Everything from pattern-changing browsers, to titanic filter feeders, to multi-locomotive hunters, Before concluding on Irou's second emergence of sapience.

#my art#artist on tumblr#art#speculative biology#worldbuilding#alien species#neo-anthropocene#cladogram#xenobiology#speculative zoology#speculative evolution#exobiology#astrobiology

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

My own MH Theropod cladograms!

some of the placements are a bit iffy and its mainly just speculation as il admit some of them are very hard to classify but hopefully this all works!

but i had fun doing it while listening to GU Glavenus theme!

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was motivated to draw my lost Iggyverse dragon cladogram from years ago and now HERE IT IS. It's a bit basic but you can still get the gist. I've drawn species sheets of the sapient ones - water dragons, dragon whales, fire dragons, and dragonkin - you can find on my Toyhou.se!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

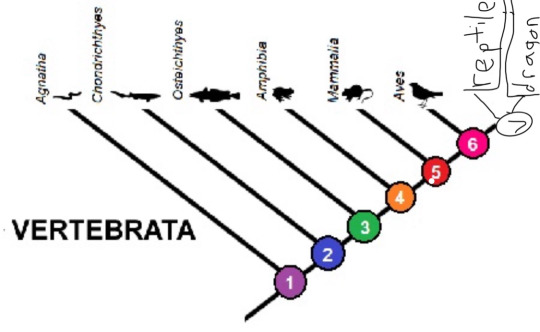

About dragons, specially ones with 4 legs and 2 wings such as in the Wings of Fire book series or How to Train Your Dragon movies.

TL;DR : Dragons are a different class than reptiles but evolved from reptiles. They evolved wings first and then evolved front limbs, letting them have 6 limbs.

They have 6 limbs, unlike any other animal, and this had never been evolved in animals before. This bothered me to no end as reptiles don't have this many limbs. I've been trying to wrap my head around this for a while now but I think I've come up with a good enough biological explanation for a make believe fantasy creature:

Dragons have to be their own class, such as mammals, birds, or amphibians. They seem like reptiles, as they'd be most closely related to them, but they have to be their own class, as having a completely different number of limbs is a major difference. At some point in time, dragons and reptiles would've split when a reptile evolved wings of some sort and also another pair of limbs, which I explain after this poorly edited cladogram of the classes:

Dragons being a different class would explain the many different species of dragon in some media, such as the aforementioned Wings of Fire or How to Train Your Dragon.

As to how I think this would happen, I believe that, like I said, some reptile species evolved wings and more limbs and that was the first dragon, but that's not exactly the case. We have seen animals evolve wings from limbs, but never wings out of nowhere, that isn't how evolution works. So I believe that this hypothetical reptile evolves front-limb wings for gliding at first (similar to the draco in concept but a bone structure more like bats perhaps), and eventually they become powerful enough for flight. This reptile would then have experience some environmental pressure that causes it to also need front limbs, so individuals with small beginnings of front limbs would survive. Natural selection, evolution, adaptations, etc, etc. This reptile now has wings that evolved from front limbs and a new pair of front limbs, so it is now a dragon. Essentially, some reptile evolved wings and then evolves the front limbs afterwards.

This seems the most plausible, as we have never seen wings evolve by themselves in animals, they always come from limbs that existed first, which I've already said.

I think that maybe some reptile species population gets geographically isolated in a mountainous region with unstable ground they aren't fit to survive in. The first thing that evolved is wings to fly above the unstable terrain, and then the second thing they evolve is limbs to have stable footing when they do have to land. Evolving wings is more important as it allows them to stay off the ground and save themselves from falls, so this happens first, and then evolving another set of limbs helps them when they inevitably have to land, so both traits evolve in the correct order. This explains why dragons love mountains in media, too. It's the land they're best suited to traverse as they evolved specifically for it.

Sorry this went on a long time and probably repeated several points! If I got anything wrong such as biology terms or spelling mistakes, tell me and I'll fix it! I just needed to get this off of my chest as I finally came up with an answer to this after like a year of thinking about it. No offense to any series with dragons like this!

#wings of fire#never actually read that#how to train your dragon#fantasy taxonomy#dragons#cladogram#taxonomy

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

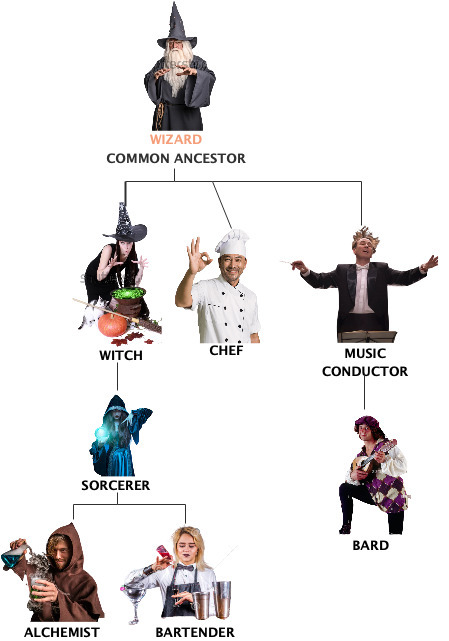

bio teacher approves

Further new discoveries have been made on my theory.

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s finally here! The new and improved 2023 version of my Piscine wyverns, most leviathans, and true elder dragons phylogenetic tree. (Outdated, here’s the current version.)

There is quite the substantial difference between this version and the older ones. Each species profile is also more in depth than my last tree, the flying wyvern tree, because there’s a lot more room for speculation in these monsters. A lot of this is also recontextualizing and reworking many outlandish traits some of these monsters have and basically giving some of canon/what some of the hunters guild tells us the middle finger for the sake of more interesting theories. Some of the scientific names for the families were made by my friend TheCuriousOne. They came up with the names for their own tree and allowed me to use some of these names too.

Because the written description is almost 100,000 characters long, I had to put it in a google doc that you can read here! I even added a chapter index so you can skip to the families you want to read.

This is probably the most in depth monster hunter cladogram on the internet

#monster hunter#monster hunter biology#monsterhunter#monhun#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#speculative anatomy#phylogeny#phylogenetics#phylogenetic tree#taxonomy#cladogram#cladograms#elder dragons#piscine wyverns#leviathans#monster hunter rise#monster hunter world

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cladogram of the Early Rodentocene.

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#cladogram

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

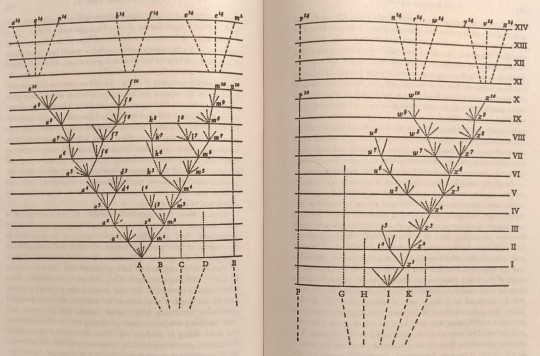

The accompanying diagram will aid us in understanding this rather perplexing subject. Let A to L represent the species of a genus large in its own country; these species are supposed to resemble each other in unequal degrees, as is so generally the case in nature, and as is represented in the diagram by the letters standing at unequal distances.

"On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life" - Charles Darwin

0 notes

Text

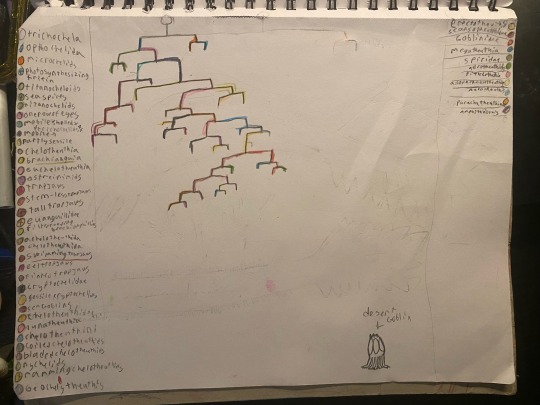

Both chelotheuthids and trapjaws are trichochelids

And desert goblin 👍

#erythra#speculative biology#speculative evolution#erythra art#spec evo#original species#lmao#cladogram#taxonomy#alien taxonomy#erythra goblin#goblin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

my family tree <3

i guarentee there's more kids than i know of. also blogs reproduce asexually they should've taught you that in school

ABCDEFGHI KLMNOP RSTUVWXY

23/26

#and per se and#only the most suited to their environment survived#just like real evolution#i guess this is more a cladogram than a family tree.#there is also cwforletters but they died extremely quickly

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

what are the different kinds of seals im curious

There are many different ways to categorize seals/pinnipeds, but we'll be focusing on the most integral to Seal Gameplay.

There are three families in your cast of playable characters: earless or "true" seals, eared seals, and walrus. These are then further split up in subfamilies, tribes, and genera. I'll sum up a brief overview of each subfamily's character class and the species within.

Phocinae: DEFENSIVE SUPPORT

These are the most common earlygame party members, and their support for the DPS can make or break a playthrough. You start the game with a Harbor seal along with your first party member, it needs no introduction. Some of these also splinter off into healing as well, but the Baikal seal also has an offensive supporter edge to it as its massive Perception stat lets it easily expose enemies' weak points and lower defenses. The Ringed and Ribbon seals are also very popular picks, they're simple but very effective at raising stats (ringed raises speed, ribbon attack)

Monachinae: DPS / ATTACKER

The bread and butter of any pinniped party. There's not much i can say about DPS seals, they do big damage! The most popular of these, of course, is the Leopard seal: It's a late-game add, but very worthwhile as it has the highest base attack stat, with good HP. Elephant seals are also a popular pick and synergize well with many fur seal species. Monk seals also have some support qualities, but it seems they're not used that often.

Otariinae: HEALING

Sea lions tend to range on a spectrum of focuses on either all-in-one healing or over-time healing. It's not as picked, but i often use an Australian sea lion in my party compositions for the over time healing, since it works really well with Spotted seals' shielding and DEF mechanics (walruses as well). Overall though, a Steller sea lion can work with mostly any party due to its simplicity.

Arctocephalinae: OFFENSIVE SUPPORT

You wouldn't believe just how much offensive status effects a fur seal can have up its theoretical sleeve. There are many subcategories under this character class such as focus on STUNs, enemy vulnerabilities, DMG over time, etc. Guadalupe fur seals especially are a hot topic: a lot of newbies tend to get intimidated by their risky and RNG-reliant strategies, but the more i've used them the more i can say they can absolutely be worth the risk.

Walruses: TANKING

Walruses are the only species in the Odobenidae family, so if you want a reliable tank there's just one pick. For what it's worth i don't really use tanks but i can definitely see the appeal in their shielding and DEF stats. They're also the only species that can redirect damage from an ally onto them.

Hope this helps!

#If you were talking about stuff like taxonomy wikipedia has a lot of info on that!! E.G. the cladogram on the main page for pinnipeds#I just wanted to do a funny cause ive been doing a lot of RPG stuff lately#not daily#asks#mod ribbon

237 notes

·

View notes