#circa 1840s

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

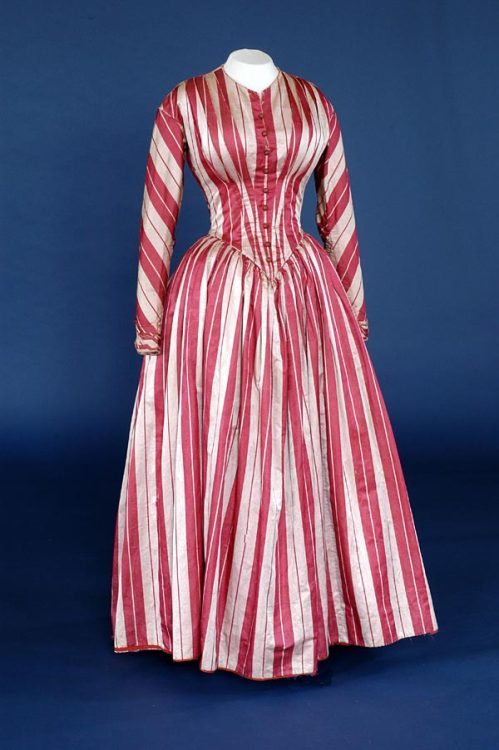

I can practically smell the candy cane on this British dress from 1849! Surprise, though--it isn't a holiday gown... it's a wedding gown!

As many folks know, the concept of the white wedding dress is fairly modern, dating to the middle of the 19th century. And even then, it wasn't ubiquitous. Wedding gowns weren't the "wear it once" they are today, and many women sought to find dresses they could later incorporate into their wardrobes. Even my grandmother, who married in the 1940s, wore a brown dress for her wedding. Part of that was a financial decision, of course, but I love the idea of colorful, practical wedding wear, too.

This dress is silk damask, which is always exciting for me. That means the pattern is reversible! Not something you would notice by just looking at it.

In classic 1840-1850 transitional wear, it's got a lot going for it: the very tailored waist looks very 1880s, while the silhouette is firmly in the 1840s. Those candy cane arms, though!

From the Bowes Museum.

#fashion history#costume#textiles#historical costuming#victorian fashion#silk dress#costume history#threadtalk#striped#circa 1849#circa 1840s#holiday gown

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

submitted by @edwardian-girl-next-door 💜🤍

#historical fashion poll submission#historical fashion polls#fashion poll#historical dress#historical fashion#dress history#fashion history#fashion plate#19th century#19th century fashion#19th century dress#mid 19th century#circa 1840#1840s fashion#1840s#1841#skirt

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

1844

#historical fashion#fashion#historical#history#historical clothing#historical dress#long dress#victorian#victorian era#textiles#textile#19th century fashion#mid 19th century#19th century#fashion plate#fashion dress#victorian fashion#old fashioned#victorian dress#dress#dresses#victorian pattern#victorian clothing#victorian history#fashion magazine#high fashion#historical costuming#historically#historical costume#circa 1840

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ironworks of Borsig in Berlin (1847) by Karl Eduard Biermann. Märkisches Museum.

#karl eduard biermann#märkisches museum#berlin#19th century art#industrial design#germany#german art#1840s#1847#circa 1840#painting#kunst#europe#art history#kunstwerk#urban landscape#artwork#oil painting#german artist#german painter#deutsche geschichte#architektur#architecture#19th century architecture#northern europe#industrial#industrial revolution#19th century#museums#ironwork

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

First page done!

The first page (chapter 1) of my “Sunset Riders” comic is done! Gee, this took forever!

#oc dump#original comic#digital art#old west#circa 1840#my ocs#oc illustration#An assassin seeking refuge#A convicted sheriff#Some random horse girl will show up and gets taught how to shoot guns by a morally ambiguous assassin?#black and white

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

c.1840 Vermont Home For Sale in Quaint Village Overlooking a Waterfall $165K

$165,000 Here is a lovely Vermont home for sale in a quaint village of 1,246 residents. The three-bedroom, 1.5-bath home has a metal roof, hardwood floors, built-ins. The back room overlooking the waterfall has lovely natural light that would be perfect for a family room, studio or office. The back deck is another great space that offers the perfect spot to sit and unwind with your morning coffee…

#1840#circa#old houses under 50k#Vermont#Vermont home for sale#Vermont real estate#vt#vt real estate

0 notes

Text

#mod terror#Alexander McDonald circa 1840 from Royal Museums Greenwich#Franklin Expedition Physician Hotties

0 notes

Text

Textile Sample Book (French, circa 1840-50).

Woven wool and silk fabrics on paper.

Images and text information courtesy The Met.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

tower of togrhol, iran. built in 1140

photo potentially by luigi pesce, circa 1840s-60s

#iran#persian#ancient persia#architecture#archaeology#ruins#ancient history#history#historic photo#curators on tumblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

“This raises the question: if industrial production is necessary to meet decent-living standards today, then perhaps capitalism—notwithstanding its negative impact on social indicators over the past five hundred years—is necessary to develop the industrial capacity to meet these higher-order goals. This has been the dominant assumption in development economics for the past half century. But it does not withstand empirical scrutiny. For the majority of the world, capitalism has historically constrained, rather than enabled, technological development—and this dynamic remains a major problem today.

It has long been recognized by liberals and Marxists alike that the rise of capitalism in the core economies was associated with rapid industrial expansion, on a scale with no precedent under feudalism or other precapitalist class structures. What is less widely understood is that this very same system produced the opposite effect in the periphery and semi-periphery. Indeed, the forced integration of peripheral regions into the capitalist world-system during the period circa 1492 to 1914 was characterized by widespread deindustrialization and agrarianization, with countries compelled to specialize in agricultural and other primary commodities, often under “pre-modern” and ostensibly “feudal” conditions.

In Eastern Europe, for instance, the number of people living in cities declined by almost one-third during the seventeenth century, as the region became an agrarian serf-economy exporting cheap grain and timber to Western Europe. At the same time, Spanish and Portuguese colonizers were transforming the American continents into suppliers of precious metals and agricultural goods, with urban manufacturing suppressed by the state. When the capitalist world-system expanded into Africa in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, imports of British cloth and steel destroyed Indigenous textile production and iron smelting, while Africans were instead made to specialize in palm oil, peanuts, and other cheap cash crops produced with enslaved labor. India—once the great manufacturing hub of the world—suffered a similar fate after colonization by Britain in 1757. By 1840, British colonizers boasted that they had “succeeded in converting India from a manufacturing country into a country exporting raw produce.” Much the same story unfolded in China after it was forced to open its domestic economy to capitalist trade during the British invasion of 1839–42. According to historians, the influx of European textiles, soap, and other manufactured goods “destroyed rural handicraft industries in the villages, causing unemployment and hardship for the Chinese peasantry.”

The great deindustrialization of the periphery was achieved in part through policy interventions by the core states, such as through the imposition of colonial prohibitions on manufacturing and through “unequal treaties,” which were intended to destroy industrial competition from Southern producers, establish captive markets for Western industrial output, and position Southern economies as providers of cheap labor and resources. But these dynamics were also reinforced by structural features of profit-oriented markets. Capitalists only employ new technologies to the extent that it is profitable for them to do so. This can present an obstacle to economic development if there is little demand for domestic industrial production (due to low incomes, foreign competition, etc.), or if the costs of innovation are high.

Capitalists in the Global North overcame these problems because the state intervened extensively in the economy by setting high tariffs, providing public subsidies, assuming the costs of research and development, and ensuring adequate consumer demand through government spending. But in the Global South, where state support for industry was foreclosed by centuries of formal and informal colonialism, it has been more profitable for capitalists to export cheap agricultural goods than to invest in high-technology manufacturing. The profitability of new technologies also depends on the cost of labor. In the North, where wages are comparatively high, capitalists have historically found it profitable to employ labor-saving technologies. But in the peripheral economies, where wages have been heavily compressed, it has often been cheaper to use labor-intensive production techniques than to pay for expensive machinery.

Of course, the global division of labor has changed since the late nineteenth century. Many of the leading industries of that time, including textiles, steel, and assembly line processes, have now been outsourced to low-wage peripheral economies like India and China, while the core states have moved to innovation activities, high-technology aerospace and biotech engineering, information technology, and capital-intensive agriculture. Yet still the basic problem remains. Under neoliberal globalization (structural adjustment programs and WTO rules), governments in the periphery are generally precluded from using tariffs, subsidies, and other forms of industrial policy to achieve meaningful development and economic sovereignty, while labor market deregulation and global labor arbitrage have kept wages extremely low. In this context, the drive to maximize profit leads Southern capitalists and foreign investors to pour resources into relatively low-technology export sectors, at the expense of more modern lines of industry.

Moreover, for those parts of the periphery that occupy the lowest rungs in global commodity chains, production continues to be organized along so-called pre-modern lines, even under the new division of labor. In the Congo, for instance, workers are sent into dangerous mineshafts without any modern safety equipment, tunneling deep into the ground with nothing but shovels, often coerced at gunpoint by U.S.-backed militias, so that Microsoft and Apple can secure cheap coltan for their electronics devices. Pre-modern production processes predicated on the “technology” of labor coercion are also found in the cocoa plantations of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, where enslaved children labor in brutal conditions for corporations like Cadbury, or Colombia’s banana export sector, where a hyper-exploited peasantry is kept in line by a regime of rural terror and extrajudicial killings overseen by private death squads.

Uneven global development, including the endurance of ostensibly “feudal” relations of production, is not inevitable. It is an effect of capitalist dynamics. Capitalists in the periphery find it more profitable to employ cheap labor subject to conditions of slavery or other forms of coercion than they do to invest in modern industry.”

Capitalism, Global Poverty, and the Case for Democratic Socialism by Jason Hickle and Dylan Sullivan

598 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cradleboard (Bibi k'inpi) made from wood, leather, glass beads, metal, and porcupine quills. Dakota, western Great Lakes Region, circa 1840.

from The Peabody Essex Museum

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

submitted by @edwardian-girl-next-door 💚💜

#historical fashion poll submission#historical fashion polls#fashion poll#historical dress#historical fashion#dress history#fashion history#fashion plate#19th century#19th century fashion#19th century dress#mid 19th century#circa 1840#1840s fashion#1840s#1843#skirt

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

1840s

#1840s#1840s fashion#circa 1840#fashion#historical#historical fashion#victorian#victorian era#victorian fashion#historical clothing#historical dress#history#long dress#gown#day dress#fashion dress#dress#dresses#victorian history#historical costuming#bonnets#hats#19th century fashion#mid 19th century#1800s dress#mid 1800s#1800s#victorian dress#victorian england#19th century

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Duchess Amelia of Württemberg (1847) by Karl Joseph Stieler. Schloss Altenburg.

#karl joseph stieler#württemberg#altenburg#19th century art#nobility#historical#female portrait#1847#1840s#1840s fashion#historical fashion#victorian#fashion history#circa 1840#19th century#oil painting#painting#art#artwork#thüringen#deutsche geschichte#german royalty#german nobility#european royalty#kunst#kunstwerk#museums#schloss altenburg#german artist#german painter

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emerald, Diamond, Silver and Gold Pendant Brooch, Circa 1840

Source: 1stdibs.com

#1stdibs.com#antique jewelry#emerald#diamond#silver#gold#antique emerald and diamond brooch#antique emerald and diamond jewelry#high jewelry#luxury jewelry#fine jewelry#fine jewellery pieces#gemville

465 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been researching a topic just weird and niche enough-- cup plates--that it occurred to me the history, museum, and literature folks on Tumblr might be able to help me with. To date the most definitive research on cup plates was published in 1971. The author was unable to find a single contemporaneous image of cup plates in use. I set out to see if I could find new information now that so much has been digitized, and so far have not been able to improve much on the 1971 work.

The topic: Cup plates. Above is a photograph of a few glass cup plates in my collection, all most likely made circa 1820s-1840s. Cup plates are small saucers about 3-3.5 inches in diameter made of glass or porcelain. Glass cup plates were made in North America while the porcelain ones were mostly made in England for export to America. In informal or private settings or when in a great hurry, people would pour their tea into the saucer to cool quickly before drinking it directly from the saucer. To protect the table, they then set the dripping tea cup on the cup plate. Etiquette manuals railed against the practice of saucer-sipping and the only description I found of people actually using cup plates was in a context where people were in too much hurry to drink their tea more slowly. I found more references to drinking from a saucer (minus cup plate mention) and they, too, often mentioned haste and always implied that this was an impolite custom. Nonetheless, it was common enough that a housekeeping manual from the 1840s showed where the cup plates should be placed on an informal tea table. This seems to have been a uniquely American practice but strangely, only one travel narrative that I found mentions this odd custom (in the context of a frenetic meal on a riverboat). I figured English travelers would've commented on it, which is one reason I concluded it wasn't behavior travelers would have seen frequently because they weren't in as many casual or intimate spaces. You will find a lot of misinformation on the Internet about cup plate use but what I've written here is more accurate.

How can you help? I have been looking for images or printed references to cup plates being used. I've searched the Library of Congress, Smithsonian Institution, various museums that have good digital collections, academic databases for scholarly articles, and archive.org and came up with exactly one image, which is the diagram in the aforementioned housekeeping manual (Beecher), though I found numerous images of people drinking tea from a saucer (minus cup plate). I go to a lot of museums and am constantly looking for contemporaneous images that depict cup plates in use and still haven't seen any.

If you, in the course of your research, work, or hobbies, happen to encounter a 19th Century (or even 18th C though I think they were invented in the 19th, I could be wrong) written or visual reference to cup plates being used would you please share it with me-- a link to the reference or photo/screencap with citation or other documentation (e.g. I saw this at X museum on X date) would be perfect.

#u.s. history#us history#american history#history#19th century#1800s#nineteenth century#museums#glass#glassware#my stuff

176 notes

·

View notes