#cinema italiano.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cinefestival "Immersi nelle Storie" 2024: "Oltre le parole" per rompere il silenzio sulla violenza di genere. Alessandria - ’Aula Magna dell’ITC Leonardo da Vinci

Alessandria ospita la proiezione del film di Emanuele Di Leo, una pellicola che affronta il dramma della violenza e dell’omofobia, seguita da un incontro con il regista e i protagonisti.

Alessandria ospita la proiezione del film di Emanuele Di Leo, una pellicola che affronta il dramma della violenza e dell’omofobia, seguita da un incontro con il regista e i protagonisti. Alessandria, 8 novembre 2024 – L’evento atteso al Cinefestival “Immersi nelle Storie – A casa dopo l’uragano”, organizzato dall’Associazione La Voce della Luna, porta in scena la proiezione del film “Oltre le…

#Alessandria#Alessandria eventi#Alessandria today#auditorium Leonardo da Vinci#Cinefestival#cinema italiano.#cinema sociale#coinvolgimento#comune di Alessandria#Comunità#consapevolezza#Consulta Pari Opportunità#Cultura#Cultura cinematografica#dramma sociale#Educazione#Emanuele Di Leo#Emozioni#evento gratuito#festival di cinema#FICC#film indipendenti#Giovanna Nocetti#giustizia sociale#Google News#Immersi nelle storie#Inclusione#italianewsmedia.com#La voce della Luna#Massimo Previtero

0 notes

Text

Gloria Guida, 1970s

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

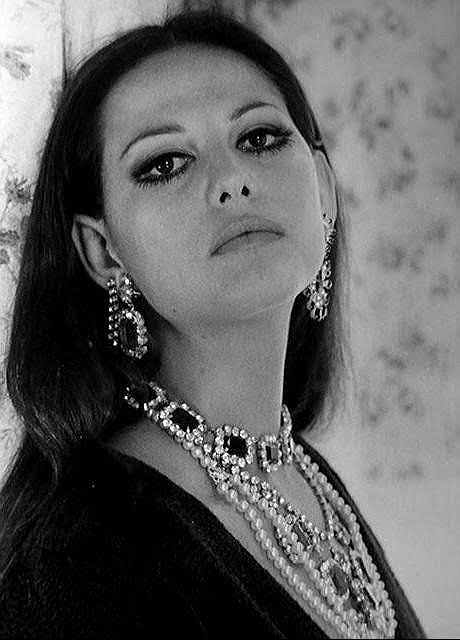

bella sofia. 🤍

#classic cinema#cinema italiano#old hollywood#old hollywod glamour#sofia loren#sophia loren#1950s#vintage#retro

392 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyways the main reason i love luca guadagnino is that, in an industry oversaturated with women/femininity always portrayed as the object of desire, he truly shows what it means to be (insanely) attracted to men and masculinity. god i don't fucking know exactly how he manages to do it but he does, oh he DOES. he understands it. and as a person who is indeed attracted to men and masculinity (and i mean not the over inflated, perfectly patinated, self serving power fantasy kind, but the vulnerable, real, crude, obscenely carnal kind) it's so validating to be on the other side of things. to actually being allowed to be fully INSIDE a desiring perspective. so hot.

#challengers#luca guadagnino#call me by your name#masculinity#mike faist#art donaldson#josh o'connor#patrick zweig#tashi duncan#tashi donaldson#zendaya#l'avevo scritto in italiano dovevo fare una versione in eng#movies#film#mine#my post#cinema#masculine#i love men#thoughts

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Faye Dunaway & Marcello Mastroianni in A PLACE FOR LOVERS / AMANTI (dir. Vittorio De Sica, 1968)

#a place for lovers#vittorio de sica#cinema#vintage#marcello mastroianni#faye dunaway#cinema italiano#italian cinema#black and white#films#old hollywood#old films#movie stills#film stills#actors#hollywood actress#60s film#60s#60s icons#1968#sixties#1960s#60s cinema

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chelo Alonso posing on the balcony of her Paris apartment in 1958

#she was so gorgeous omf#cubana#chelo alonso#italian cinema#cinema italiano#1950s#1950s actresses#photography#Cuban actress#Paris#50s actress#50s cinema#frostedmagnolias

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cosplay the Classics: Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger (1950)

My closet cosplay of Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

The Star

When Alida Valli arrived in America, she arrived with ten years of screen experience under her belt and thirty credits—a substantial resume for a twenty-six-year-old. By the 2000s, Valli had committed over one hundred roles to film, on top of her television and theatrical work. In her seven-decade film career, Valli demonstrated outstanding versatility as genres shifted and styles evolved. In a half dozen countries, a bevy of heavy hitters directed her: Alfred Hitchcock, Pier Paolo Passolini, Luchino Visconti, Carol Reed, Mario Bava, Georges Franju, Margarethe von Trotta, Dario Argento, Bernardo Bertolucci, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Claude Chabrol, to name just a few.

She became one of the most accomplished performers to ever emerge from Italian cinema, though Alida Valli’s American period seems like a footnote to her rich biography and filmography. (With the exception, of course, of the British-American production, The Third Man (1949)). How did Hollywood stardom evade such a talented, experienced young actor with a face that photographed beautifully from every angle? Well, let’s begin at the beginning.

Alida Altenburger, later Valli, was born in what was Pola, Italy—and is now Pula, Croatia—to a noble family that would soon relocate to Como in the north of Italy. When Alida was in her teens, she enrolled in the Centro sperimentale di cinematografia in Rome to study screen acting. The young Alida must have displayed some natural talent because her first film credit came just a year or so later.

Valli quickly became a popular star—primarily in telefoni bianchi (White Telephone) films. Telefoni bianchi was a film genre/stylistic movement aesthetically characterized by art deco. The films often depicted luxurious and/or bourgeois lifestyles; as a white telephone was a symbol of status, it in turn became a symbol of the genre. Telefoni bianchi films are typically comedic or light in tone and they avoid suggestions of intellectual depth or addressing social issues. As you probably already know, to consciously avoid “politics” is always a political decision. This movement was part of a broader push under Mussolini’s National Fascist Party to cultivate an aspirational fiction of affluent urbanity and to forge a new ideal of Italian-ness based largely on consumerism and consumer goods. The relatively carefree lifestyles depicted in the telefoni bianchi films was far removed from the lived reality of the majority of Italians during the global depression of the 1930s.

(Oversimplified-but-probably-necessary historical notes here: Italy as a single, unified nation was only about sixty-years-old at this point; meaning a unified sense of Italian-ness was kinda new. Then, in the first half of the twentieth century, Europe saw huge cultural and social changes engendered by industrialization, imperialism, and war. Use of mass media was a key factor in the nationalist goals of Mussolini’s government to shape a new new definition of modern Italian-ness.)

The rise of telefoni bianchi films was in large part due to Italy cutting down on importing American movies in the 1930s. Telefoni bianchi were one way to fill that gap, not simply by reflecting the polish and sheen of Hollywood productions but also by retooling American-style propaganda for Italian audiences. The emphasis on simplified narratives in telefoni bianchi stories, where any problem can be faced with good, traditional values and hard work, is a direct descendant of similar American films of the period. [1]

Alida Valli in the telefoni bianchi film Ore 9: lezione di chimica (1941)

Likewise, up-and-coming stars, like Alida Valli, were built up to replace (and hopefully surpass) American stars who were popular in Italy. One fan magazine somewhat superficially compared Valli to Loretta Young. They were both fresh-faced starlets who started to work professionally from a very young age, but their typical roles and styles of characterization were very different. However, I do think it’s worth noting that both actresses were often paired with older male leads early in their careers. The teen-aged Valli made multiple films with Amadeo Nazzari, who was fourteen years her senior. Teen-aged Young had some of her first major roles opposite Lon Chaney (thirty years older), Conway Tearle (thirty-five (!!!) years older), Ronald Colman (twenty-two years older), and John Barrymore (thirty-one years older). Additionally, in my opinion, playing in adult roles so young had the unintended consequence of both actresses playing more mature roles sooner than seems logical.

Of this period in Valli’s career, in his book Mussolini’s Dream Factory, Stephen Gundle wrote:

“Valli was predominantly an ingénue. She played fiancées, schoolgirls, daughters of industrialists and taxi drivers, dancers, secretaries and students. She was one of the many new faces that lent their countenances to a gallery of female types that corresponded to roles available to young women at the time.”

The two most cited films of Valli’s telefoni bianchi era are Mille lire al mese / A Thousand Lire per Month (1939) and Ore 9: lezione di chimica / Schoolgirl Diary (1941). I have yet to track down a copy of Mille lire, but, if Ore 9 is a representative indication of Valli’s telefoni-bianchi work, the reason for her massive popularity is clear: Valli’s Anna has youthful exuberance tempered with an acerbic and headstrong edge. From a technical perspective, Valli displays sharp comedic timing and perfectly executed control over her voice, facial expressions, and body language. (These are skills I knew Valli had from her later work, but it is a revelation to see that she already had them at only 19-20 years old!)

Though she was a staple star of telefoni bianchi, Valli branched out into more dramatic roles by the end of the decade; making a mark especially in period dramas. The characterization that first proved Valli’s dramatic chops was Luisa in Piccolo mondo antico / Old-Fashioned World (1941). Piccolo mondo was part of yet another emergent, albeit short-lived, Italian cinematographic movement: calligrafismo. This movement was more stylistically diverse than telefoni bianchi, but has likewise been criticised for avoiding deeper themes or social commentary. Calligrafismo films focused on formal sophistication—meant to emphasize film as art and Italian technical prowess—and literary source material—usually from the 19th century. Piccolo mondo is a lauded representative of calligrafismo and its director, Mario Soldati, is considered one of the movement’s premiere practitioners.

Alida Valli in Piccolo mondo antico (1941)

Valli’s character Luisa is a woman of bourgeois status who marries a nobleman for love and has to suffer the consequences. The events of Piccolo mondo take place over the course of a decade and so the then twenty-year-old Valli had to play Luisa as: a hopeful but anxious young bride, a faithful and self-possessed wife and mother, and many stages of extreme grief over the loss of a child and estrangement from her husband. Giving such a role to a performer that young, I think, could easily result in histrionics, but Valli genuinely pulls it off. Valli managed to give Luisa dignity and melancholy that belied her performer’s age. Her work particularly in the last third of the film is very strong and effectively heart-rending.

At the start of the decade, Valli firmly established the breadth of her technical abilities as an actor, but, in 1943, Mussolini’s fascist regime collapsed. Reflecting later in 1965 on her work in the 1930s and early ‘40s, Valli stated:

“I was a young girl, 16, 17, 18 years old and I was successful and privileged. Everything was easy and when things come to you easily you do not stop to ask if things are right or not. I made films as automatically as a secretary types a letter. If no one explains to you what evil is, how do you know what is evil? … I never thought that a cinema like that [i.e. white telephone films] was wrong or that it would end, because no one thought that Fascism would end.” [2]

Valli’s candor here is appreciated; highlighting the ignorance that privilege can breed. It’s a strange position for a teenager to be in, not formally tied or allegiant to Fascism, but still part of the corporatist machine that props it up.

The new government of Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, but then Nazi Germany invaded and occupied the north of Italy. The majority of professionals in the film industry, which was centered almost exclusively in Rome at the time, refused to collaborate with the invaders. Some filmmakers fled to Venice to establish a film colony there. Valli made the decision to “retire” from acting. Her refusal to work on films for the occupiers made Valli a target, but, with the help of friends, she was able to stay in her beloved Rome, albeit in hiding. It was while Valli was in hiding that she met and married her husband, musician Oscar de Mejo.

Valli’s “retirement” ended in 1945, though she had not been absent from Italian screens in the interim, as her earlier films were still circulating. Valli soon had an especially well-regarded turn in Eugenia Grandet (1946) as the long-suffering daughter of a wealthy miser. Valli’s performance as the title character displays all of the variety and depth she had cultivated in her first decade in film—and it was captured beautifully by cinematographer Václav Vích. Returning to the screen after the war, and contending with your star image potentially being associated with a fallen fascist regime, must have been massively challenging for the twenty-five-year-old. Despite her success in Eugenia Grandet, the potential of a fresh start in America must have seemed promising for Valli—with her husband and baby in tow, of course.

Alida Valli in Eugenia Grandet (1946)

Unfortunately, the notorious David O. Selznick was the one who scouted Valli.

The first film she made for Selznick was The Paradine Case (1947), directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Valli was still learning English while the film was in production and, as a result, had to study her lines phonetically. You would never guess that watching the film as Valli gives a layered performance with intriguing nuance in much of her line delivery. The Paradine Case had a troubled production and it is understandably regarded as a lesser film of Hitchcock’s, Valli’s work is the strongest aspect of the film.

Selznick’s plans for Valli lacked forethought and were in no way based on her versatility or unique skills as a performer. Selznick’s marketing for the star harped on her becoming the next Bergman or Garbo, rather than the first Alida Valli. Starting with Valli’s very first Selznick production, rather than getting a typical title card for her credit, she was represented solely as “Valli” with a cursive namemark. Selznick explained this odd decision as a way to evoke Garbo-ness. (Although, it was actually Nazimova who originated the namemark gimmick in the US.) The “Valli” gimmick did not offer the mystique Selznick had imagined. Alida Valli herself recounted how foolish the marketing was if for no other reason than that there was an established, popular star called Rudy Vallée around. Having David O. thoughtlessly micromanaging her star image meant that Valli’s adjustment to the Hollywood system of filmmaking was the equivalent of playing on hard mode.

“‘In Europe, actors are just people. We have to do things for ourselves,’ she explained. ‘But suddenly, I sign the American contract, and everything is done for me as if by magic. I am no longer a person—I am a Thing.’” —Valli quoted in “Double Life” by Inez Robb in Modern Screen, June 1948

Valli’s second American film was the forgettable The Miracle of the Bells (1948). However, while The Third Man would be Valli’s next release, the film I’m cosplaying here, Walk Softly, Stranger, was already in the can. Selznick disliked the original ending of WSS and demanded re-writes and re-shoots. Selznick’s ending satisfied no one. Howard Hughes, whose distribution company, RKO, was handling the film’s release, reportedly chose to shelve WSS. But, after the success of The Third Man, Hughes wished to capitalize on the pairing of Joseph Cotten and Valli. WSS was un-shelved nearly two years after it was produced; unfortunately retaining its egregious, tacked-on “happy” ending (which I’ll talk more about later).

Portrait of Alida Valli from Modern Screen, June 1948

After her fifth film, The White Tower (1950), Valli bought herself out of her contract and returned to Europe. Why Valli left so abruptly is likely a mix of personal and professional issues. While filming The White Tower, Valli was having marital issues and she was pregnant with her second child. According to Valli, Selznick did not want his star to be pregnant. Working under Selznick seemed nightmarish. In addition to the ridiculous constraints on how she was meant to conduct her personal life, it must have been clear to Valli by 1950 that she would never have the opportunities to build a career with the same range that she had proven herself capable of in Italy.

Why Valli left Hollywood is maybe not such a great mystery. Regardless, it’s also clear that if the rigid studio system had thoughtfully cast Valli in higher quality material and/or allowed her to do comedy—something she brought up multiple times in the press while she was in the US—the American viewing public might have had a better chance to appreciate her skill. Selznick instead took a stellar actress and limited her to a knock-off Bergman. What a massive waste.

Valli’s American period was inarguably difficult, but it seemed to galvanize her for her return to Europe. Despite a rather large hiccup in her personal life that affected her career in the early 1950s, Valli found international acclaim. Valli not only worked in her native Italy, but also Spain, France, Britain, Mexico, and, yes, even the United States again. From the 1950s to the 2000s, Valli traversed new genres, styles, and movements freely and with dauntless creativity. If you mostly know Alida Valli for The Third Man (or perhaps for her supporting roles in giallo classics like Suspiria (1977) or Lisa and the Devil (1973)), take this essay as a prompt to check out more of her work! I plan to as well because I’ve seen her in over a dozen films and still feel like I’ve only scratched the surface!

——— ——— ———

[1] I’ve seen the work of Sicilian-born American director Frank Capra listed as a primary influence on these films—something I’d like to research further to be perfectly honest!

[2] from O. Fallaci, ‘Lo specchio del passato’, L’Europeo, 14 January 1965. but cited from Gundle’s Mussolini’s Dream Factory. Gundle doesn’t specify, but I assume this is his own translation from the original Italian.

——— ——— ———

The Film

Joseph Cotten and Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

To defer to Eddie Muller: Walk Softly, Stranger is a noir “near miss.” Rather than a proper film noir, it’s a romantic melodrama with a little noir seasoning, marred by studio interference. But, WSS’s complicated romantic storyline and noir-ish subplot, not to mention great performances by the leads and support, stick with you—even if the aforementioned tacked-on ending spoils the final effect.

My closet cosplay of Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

A Mysterious Stranger (Cotten) arrives in Ashton, a picture-postcard of small-town America—down to the big factory owning practically everything in said small town. With a touch of recon, the stranger ingratiates himself to a magnanimous local widow, Mrs. Brentman (Spring Byington). She even helpfully produces his pseudonym for him: Chris Hale, the boy child of the family who lived in her house before her. In this opening sequence, Chris is established as an adept wheeler dealer.

After securing lodging, Chris’s next target becomes Elaine Corelli (Valli), the daughter of the factory’s owner. Chris lays it on thick, but he’s missing a key bit of information: Elaine is now in a wheelchair. A few months prior to their meeting, Elaine took a bad fall on a ski jump and took permanent damage. So begins a fraught love story between Chris and Elaine.

Chris starts getting comfortable in his new identity. He has a home, a job, friends, a doting auntie, and is dating the richest girl in town. What’s initially meant to be a chance to lie low starts to seem like a genuine second chance at a normal life. The suspense kicks in when this unexpected peace is put in jeopardy as a character from Chris’s old life shows up in town unannounced. When Chris is eventually cornered by his criminal former cohorts, it results in Chris getting ventilated, a massive car accident, and then, unexpectedly, Chris still alive and headed to prison.

Collage of the hair and makeup reference photos of Valli I used for this cosplay

WSS is a languidly paced movie, matching the sleepy-but-contented nature of Ashton. It’s an unsung example of one of my favorite narrative devices: the city as a character. Personally, I think this is a key reason why WSS’s ending is so jarring. Ashton is socially stratified, but it’s still a town with communal spirit. It’s exactly this spirit that gives Chris the false hope of a fresh start—a nostalgic yearning not for what-was but for what-could-have-been. In the original script’s ending, Chris’ death is implied and Mrs. Brentman passes along the poem “John Brown’s Body” to Elaine. It’s a melancholic ending that both matches the Sehnsucht-ish tone of the film and taps into the film’s theme of alienation within an idyllic image of the American Dream. The re-worked ending has a rambunctious energy, nonsensical Will-Hayes-ian logic, and a troubling continuation of Chris and Elaine’s relationship.

In addition to the regrettable ending, I also feel that WSS missed an opportunity to examine Elaine’s character arc thoughtfully. Elaine first appears alone on the patio of the Ashton country club while there’s a lively party going on inside. We get to know Elaine along with Chris; as we share his perspective for the whole of the film. It’s clear that her recent disabling event has left her in a well of self-pity. There’s not much time devoted to Elaine’s new quotidian reality, because the film is really Chris’ story. So, a lot of what we learn about Elaine is indirect. For example, we learn how long it’s been since Elaine’s accident via a social column. From the way Elaine speaks and the micro-expressions and reactions that Valli registers, it can be inferred that Elaine was a social butterfly before her St. Moritz accident—but also that her social circle was composed of fair-weather friends. Elaine is almost always by herself when we (and Chris) encounter her. This makes her seem not only chronically isolated, but vulnerable. And, since we know Chris is not exactly on the level, this creates an interesting tension that the filmmakers seem only mildly aware of.

Much of Elaine’s dialogue about herself is rife with internalized ableism. She even goes so far as to liken her current state to death. Of course, Elaine is still new to her disability and the grief experienced during the adjustment period from able-bodied to disabled in an ableist society is real and common. WSS would be a stronger film if this element had been examined with a bit more perspective. The film does, however, touch on a complicating factor to Elaine’s experience of disability: the privileges she’s afforded as a wealthy person. Even though Elaine is often reliant on others to compensate for the lack of accessibility you would expect in 1940s America, she has the resources and capacity to take long trips and go out and socialize. There’s certainly no hint of trouble in paying medical bills—she’s literally the richest girl in town. Addressing Elaine’s social and economic privilege is not very thoughtfully done however, as Chris’ challenge to Elaine’s self-pity is flattened into patronizing abled savior type stuff.

That said, to Chris, Elaine is neither a target of pity nor someone who needs to be taken care of. She’s simply a very pretty, very rich girl that he’s very attracted to. Her disability is not coupled with any infantilization or inherent character defect—both all too common tropes in Hollywood films. I’ll admit, for a film to admit that a woman being disabled doesn’t make her less desirable is nice to see (and unfortunately is still a novelty), but how WSS handles it leaves a lot to be desired.

Alida Valli in Walk Softly, Stranger

There’s more depth to Elaine than we usually get for disabled women on film—particularly women with visible disabilities—even though she’s not a fully-developed lead. Valli’s performance imbues Elaine with intellect, dignity, and complex, layered emotions. There’s a scene shortly before the climax of the film where Elaine and Chris have an earnest conversation about where they stand with one another. It’s revealed that Elaine has known Chris was a phony from their very first meeting when he slipped up with one of his lies. Through this one reveal, we learn by implication that Elaine was never a dupe and that in those situations where she seemed vulnerable to him, she wasn’t. Regardless of how many windows Chris entered by unbidden, Elaine had more control of the situation than we, and Chris, realized.

Chris’ and Elaine’s arcs in the film align in that both learn to accept a new way of life. For Chris, it’s about recognizing that he can, in fact, lead an honest life and that he’s entitled to one (after righting his past wrongs of course). For Elaine, it’s recognizing that St. Moritz was not the end of her life and that her future will be different but still full of potential. This theme of new life is sublimated in the scene where Chris and Elaine lay their respective cards on the table—this discussion doesn’t take place in the library, where they normally hang out, but in a solarium surrounded by lush plants.

WSS careens disjointedly into its final sequence. Chris has survived an encounter with a gambling kingpin and he’s serving time. (For which crime though? And under his assumed name?) Elaine is there to meet him as he’s transferred from the hospital ward to the penitentiary. Elaine explains that she’s going to wait for him. This revelation is couched in a self-hating, ableist monologue. Where it seemed just a few scenes ago that Elaine was making progress, suddenly she thinks that she and Chris will “deserve” one another more when he’s an ex-convict, broken by the system. (???) Her own estimation of herself should have transformed by this point in the story. In what’s supposed to be a hopeful coda, any suggestion of character development for Elaine is summarily wiped out.

All that said, I still recommend checking out WSS. It’s a nuanced, affecting melodrama and a complicated entry in the evolution of disability representation in Hollywood films. The dialogue is snappy and it has an interesting story structure; buffeting between the relative peace of Ashton life and Chris’ criminal undertakings. Alida Valli and Joseph Cotten are always worth watching and Spring Byington is as delightful as ever as the lonely and sweet landlady.

If you’d like a noir-inspired double feature with Walk Softly, Stranger, Out of the Past (1947) also features a former criminal who tries to find a new life on the straight and narrow, which turns out to be too narrow. Or watch it with Hollow Triumph (1948), where a criminal tries to hide out in a small town by taking over a local’s identity. (An added benefit to HT is that it has some entertainingly off-the-wall plot devices.)

——— ——— ———

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

——— ——— ———

Further Reading/Viewing

Mussolini’s Dream Factory: Film Stardom in Fascist Italy by Stephen Gundle

Spellbound by Beauty: Alfred HItchcock and His Leading Ladies by Donald Spoto

Il romanzo di Alida Valli by Lorenzo Pellizzari and Claudio M. Valentinetti

The RKO Story by Richard B. Jewell and Vernon Harbin

Alida / Alida Valli: In Her Own Words (2021)

#Alida Valli#1940s#1950s#cosplay#film#cinema#american film#classic movies#classic film#cinema italiano#film stars#filmblr#film history#history#David O. Selznick#film noir#noir#noirvember#robert stevenson#classic cinema#old hollywood#cosplay the classics#closet cosplay#classic hollywood#hollywood#Joseph Cotten

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday Luca Marinelli +40🎂❣️

#luca marinelli#nicolo di genova#nasone del mio cuore#the old guard#tog2#tog fandom#best actor#cinema italiano

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monica Bellucci e Gianni Versace, 1995.

#monica bellucci#gianni versace#versace#90s actress#90s actors#90s icons#90s films#90s style#anni 90#90s aesthetic#90s fashion#90s music#90s#90s supermodels#90s nostalgia#90s movies#vintage icons#vintage women#italian actress#italian style#old money#old hollywood#vintage film#vintage style#italian photography#italian girl#cultura italiana#poesia italiana#cinema italiano#italian cinema

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

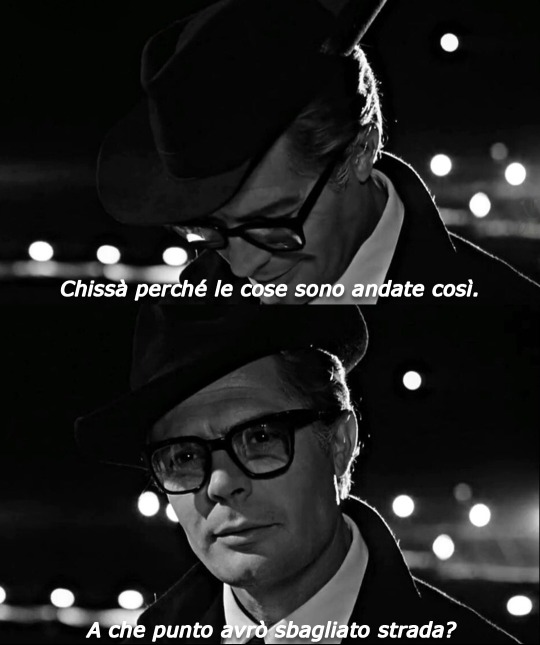

#federico fellini#8½#citazioni#frasi#seguimi#compagnia#seguimi e ti seguo#noia#pensieri#domande#film#cinema#cinemetography#cinema italiano

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

India (Roberto Rossellini, 1958)

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sophia Loren.

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

y'all i had a good day after weeks 💌

#la notte#michelangelo antonioni#marcello mastroianni#jeanne moreau#monica vitti#italian cinema#cinema italiano#european film festival#indian habit centre#dhoomimal art gallery#tribal art#bhil art#scuola nazionale di cinema#delhi#दिल्ली#دہلی#film screening#restoration#60s#1960s#neo realism#studyblr#booklr#dark academia#light academia#aesthetic#studyblog#book blog#delhi blog#film blog

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Invelle - direct by Simone Massi

#Invelle#Simone Massi#italian movie#italian movies#cinema italiano#animation#traditional animation#ooh wow#art#black and white#my gifs

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claudia Cardinale portraits

#claudia cardinale#cinema#vintage#actors#old films#60s vintage#italian actors#cinema italiano#classic hollywood#old hollywood#60s women#60s fashion#portrait photography#b&w#black & white#make up inspo#60s makeup

188 notes

·

View notes