#cincinnati newspapers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

More Than A Daredevil, Ruth Neely Paved The Way For Cincinnati’s Women Journalists

When Ruth Neely France died in 1956 Cincinnati’s ink-stained wretches tumbled all over themselves to effusively memorialize Neely’s non-nonsense style and her outrageous adventures in the quest for a front-page headline. Some of the anecdotes were actually true. A few would have brought a smile to Neely’s face. In her day, she was not above a dash of hyperbole to keep her readers entranced.

Did she really climb to the top of the Suspension Bridge? Pilot a dirigible? Slide down a pocket fire escape from the tallest building in town? Yes, Ruth Neely did all this and more.

The daughter of an attorney, Neely was born in Kentucky around 1875, received an unusually thorough education for a woman at that time and taught in the Covington schools for several years. One day, she walked into the offices of the old Cincinnati Commercial Tribune and talked herself into an unpaid quasi-internship ferreting out bits of neighborhood news. Within a few months, the editor offered her a full-time position.

Neely was not the first woman hired by Cincinnati newspapers. A bevy of mostly unsigned scribes had compiled the society columns for decades prior and the Commercial Tribune’s competitor, the Cincinnati Post, already had a powerhouse “girl reporter” in Jessie M. Partlon. Neely’s influence, however, was unmatched and she was a force to be reckoned with for more than half a century.

As Miss Partlon discovered at the Post, newspapers considered women suitable for only two assignments – social tidbits or stunts. Miss Neely (she employed her birth name throughout her career even after marrying traveling salesman William France in 1912) dove into the latter role, quickly gaining a reputation as a dauntless daredevil.

Cincinnati was enthralled by a 1909 air show out at the Latonia racetrack. Glenn Curtiss was there, buzzing the grandstands while demonstrating maneuvers. So was Cromwell Dixon, a 17-year-old aeronaut with his motor-powered dirigible. All of the other aircraft were one-seater biplanes of various makes, requiring a great deal of skill and mechanical aptitude to fly. Cromwell Dixon’s dirigible was little more than a floating rowboat with a bamboo seat. Neely hopped aboard and drifted upward and out over a lake. She wrote:

“Not more than a decade ago I skated on the same lake. If, at that time, I had glanced upward and said to my companion, ‘Look, there goes a woman in an airship,’ I am sure he would have thought me mad. Yet it is but 10 years.”

Neely’s stunts gained her fame but exasperated her family and friends. She was undercover, investigating conditions in the women’s wing of the Cincinnati Workhouse, when a delegation from the Woman’s City Club arrived for a tour. According to the Cincinnati Post [9 September 1999]:

“The visitors were pleased to find the inmates in good condition and spirits – particularly one in a freshly laundered uniform ‘smiling smugly’ at them. When the club women realized who she was, they stared at each other in horrified consternation until one blurted out: ‘Mrs. Ross, it's your sister! It's Ruth!’ Mrs. Ross is said to have replied: ‘Good heavens! What on earth has she done now?’”

Among Neely’s other feats, she was the first woman in America to fly in an Army airplane to promote an enlistment drive. She climbed to the highest point on the Roebling Suspension Bridge for an interview with a worker repairing the span. He was startled but answered her questions.

Every report of Neely’s career dutifully mentioned the time she slid 34 stories from the top of the Union Central Tower, the tallest building in Cincinnati at that time, on a “wire fire escape contraption.” Well, not exactly.

Pietro “Peter” Vescovi traveled the country in 1914, demonstrating a “pocket fire escape” of his own invention, consisting of a spool of steel tape. His routine varied little from town to town. Vescovi found the tallest building in that particular burg, announced to the local newspapers that he would safely descend from the roof to the sidewalk, and collected headlines and sales. In Cincinnati, the brand-new Union Central Tower fit the bill. It was, at the time, the tallest building outside New York City.

On Friday, 30 January 1914, Vescovi stepped off a ledge on the fourth story of the Union Central Tower and glided to the pavement. Watching from the ground, Ruth Neely asked if she could give the apparatus a try. With an eye toward her own headlines, she suggested a higher launching point, so Vescovi led her to the 21st story. Fastening his steel spool to the window sill, Vescovi and Neely both stepped into space. She reported:

“We swung, swayed by the wind, slightly to eastward, affording just one hideous glimpse of the Vine street canyon. Then the breeze veered, whisking us, its plaything, westward ho. A huge mass of nothingness was disclosed, attached neatly to a bank of clouds. I closed my eyes.”

The pair alighted on the roof at the 17th floor. Neely insisting that she had clung to the unusual device so fervidly that her thumbprint dented a steel buckle on Vescovi’s harness.

Neely later flew around Cincinnati in an autogiro piloted by Amelia Earhart, and dropped her report of that flight onto the roof of the Cincinnati Post as the famed aviatrix buzzed the building.

After three decades at the newspapers, covering everything from gardening to political conventions, Neely spent a year writing and editing the three-volume “Women of Ohio,” including biographies of 1,200 women overlooked in the history books. She was an early member of the Women’s City Club, was instrumental in organizing the Cincinnati Peace League and participated in the local chapter of the Foreign Policy Association. A plaque at the Hamilton County Courthouse lists her as one of the women responsible for gaining women the vote. On her death, her good friend, Post columnist Al “Cincinnatus” Segal, opined:

“She was not the first woman, of course, to be a ‘regular reporter’ on a daily newspaper. But she had to prove, to many a skeptical male in the business, that she could use her wits and courage and come back with her story. She won her place, her journeyman’s rating, the hard way and she helped pave the way for the many women who followed her into city rooms since the early years of the century.”

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Old Folks (Mother and Father)

Artist: John Steuart Curry (American, 1897-1946)

Date: 1929

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio

#portrait#oil on canvas#fine art#couple#man#woman#indoor#dog#rocking chair#newspaper#crocheting#leisure#window#table#mill#rural landscape#american culture#john steuart curry#american painter#20th century painting#cincinnati museum#oil painting#artwork

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The questioning of one name that was previously prominent in regards to enslaved Blacks: "George Washington." This clipping piqued my interest because of my previous and current work within Catholic institutions. The Catholic Church would baptize previously enslaved Blacks at the request of the enslaver. Why would someone who has no remorse for enslaving this community turn around and ensure religion was bestowed upon them? For their own righteousness. Through transcribing baptismal records for previously enslaved Blacks, I came across many "George Washingtons." With Presidents Day being this past Monday, the 19th, during Black History Month, I thought it important to highlight that we established this holiday in light of our very first Slave-owning President, George Washington.

Cincinnati, Ohio📍Salem, Ohio📍

Publication: The Anti Slavery Bugle

Issue Date: February 2, 1856

https://reckoningradio.org/church-record-details/?child_id=9532

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

DELEGATES OF THE DAY - Purificacion Valera (Philippines 1952) and Edward Hogan (Malaysia 1950)

The Cincinnati Enquirer, July 6, 1956

#delegate of the day#purificacion valera#edward hogan#philippines#malaysia#1952#1950#the cincinnati enquirer#post-forum activities#*pictures#htyfnetwork#herald tribune world youth forum#new york herald tribune world youth forum#the world we want#vintage#1950s#newspaper

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

Great cover after Pete Rose passed away at 83.

0 notes

Photo

Richard Sanders birth announcement—August 23st 1940

0 notes

Text

Child labor was quite common in America deep into the 20th century. One of the most important reformist organizations was the National Child Labor Committee, created in 1904. Its leaders, many of whom were key figures in the progressive movement, understood that they would need to expose the realities of child labor in a visceral way. So they hired a photographer named Lewis Hine, whose photographs created a haunting record of American child labor.

One of the most common jobs for young boys was as a newspaper seller. Though this was not as grueling as factory work, it did have definite downsides. The day started early — here are some St. Louis newsboys beginning work at 5 am:

The newsboys were often exposed to bad habits on the streets:

Newspaper sellers, unlike most child laborers, did have some protections — “Newsboys’ Protective Associations” formed in many cities, and served as a sort of union and fraternal organization for the kids. Here, the Cincinnati Association is training kids in the “manly art of self-defense:”

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

745 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 7, 1919. Santa and his elves are putting in the toy supply for local department store Pogue's, from the Cincinnati Post newspaper. From The Golden Age of Department Stores, FB.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can't find on my blog if I've posted about this before, but the 19th century local dandy that wrote Edgar Allen Poe fanfiction, Douglass Sherley, was mentioned in this letter that a local historian dug up for me and it is fascinating. I'm just going to copy + paste my pillowfort post about it.

So the historian I've been in contact with was an incredible help, and went ahead and transcribed the bits of the letters that discuss Sherley.

"The description of Douglass Sherley is on the final page of that letter (page 6) and reads:

“By this time you have, doubtless, read of the horrible confirmation of the old reports about Douglass Sherley. I did not believe them before and cannot comprehend how he could have been guilty of such baseness. He has consented to leave the country for good next Monday, so ___ Sherley’s brother informed brother Will.” Bruce then goes on to talk about cantaloupes, I think. I believe the blank might be “Mrs.” or a first name.

Second letter, second page

“You say you did not read of Douglass Sherley’s disgrace. Don’t speak of it to anyone, for the disgraceful affair should never pollute a woman’s lips.' "

These letters are from August 23rd and August 28th 1896, and there are barely any mention of him in the Courier Journal after 1896. This is important because prior to that he was all over the paper. There were mentions of him going to numerous weddings and parties, he wrote columns for the paper, and he was involved in putting on things like operas and plays.

He also died in Martinsville, Indiana, which makes me wonder if that was where he moved. (I believe he still lived in Louisville for part of his last years.)

I think I've just about reached a wall with my research; the only other thing I have any interest (at the moment, at least) in chasing after are newspapers that he was in when he toured with James Whitcomb Riley. Someone else was kind enough to write a blog entry that includes clippings from non-Louisville newspapers, and they're an interesting look into how Sherley was known outside of Louisville:

The Wilmington, NC Weekly Star, 8 Dec 1893 (reprinted from the Indianapolis Journal):

Kentucky’s Oscar Wilde Douglass Sherley is doubtless, in a literary way, the most conspicuous person in Louisville. He is notable also in many other ways. At first glance he is seen to be what is styled a “character.” Being fond of character study himself, he would no doubt generously recognize his own claim to the classification. He is a large, well built, squarely adjusted man, with a massive head and neck, dark hair, an intelligent brown, suggestive of femininity in a way, keen and kindly eyes, a large brown mustache, worn in curly ends like the “beau catchers” of the traditional stage spinster, a pleasant, sensitive mouth, with the air of a man of the world, but withal a clean, temperate, perfectly correct man of the world. He has a droll habit of holding his head on one side and looking aslant through his eyeglasses, which gives him a unique expression, and without which and the flowers in his lapel, almost always a red rose, he would hardly be Douglass Sherley, Mr. Sherley is popular among the men, and also much liked by the women, his literary work being more generally appreciated by the latter. There is a fine, feminine, but not unmanly, quality in his writings, which really only women, or men with a like feminine streak, can interpret and enjoy.

A point of interest is this May 1886 article about Sherley from the Cincinnati Enquirer

A CLUB SCANDAL Douglas Sherley, of the Pelhams, Involved He Hunts for the Originator of the Story, and in His Search Punches a Bank Clerk SPECIAL DISPATCH TO THE ENQUIRER LOUISVILLE, KY., May 3 — Nothing is talked of in the clubs to-night except a difficulty which occured to-day between Mr. Douglas Sherley, Present of the Pelham Club, and Mr. Matt Smith, a member of that body. Mr. Sherley is a man of means and leisure, and belongs essentially to society. HE has written several books and has built an aesthetic house that has been the talk of the town for three years. The Pelham Club members are the younger set of society men and recently persuaded Mr. Sherley to accept the Presidency of their club. Within the last two weeks, however, a movement has been on foot in which twenty members of the club were interested to bring about Mr. Sherley’s removal. The understanding was that the twenty members in question should offer their resignations simultaneously to the Board of Directors. When questioned in regard to this unexpected action they were to say they would not belong to an organization which had for its Chief Executive a man who had been guilty of certain disgusting and unnatural practices that were charged against Mr. Sherley. When Mr. Sherley heard of this movement to-day he went at once to Mr. Matt Smith, a blank clerk, whom he had heard was one of his defamers, and demanded an immediate denial in writing of the nasty stories. Mr. Smith said he had not originated the stories, but had repeated them, and refused to sign the paper. Mr. Sherley, who is a fearless man and very athletic, promptly attacked young Smith and gave him a sharp blow in the neck. Smith attempted to return the blow, but outsiders interfered too quickly, and dragged the gentlemen apart before either was painfully injured. The affair quickly went the rounds, and the scandal has been vigorously discussed by society men all day. It is due Mr. Sherley to say that none of his friends believe the stories which gossips have put in circulation about him. He is an eccentric man, and some of his peculiarities have subjected him to comment, but he is a gentleman, nevertheless. Mr. Sherley has secured a cowhide and a pistol, it is said, and will either thrash or kill the man who is at the bottom of the outrage, if he can discover him.

I have a lot of thoughts about the connection but I'll get back around to that later

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Scandalous Can-Can Amused Cincinnati Until One Newspaper Clutched Its Pearls

No one really knows when or where the dance known as the can-can originated. Although associated with France, some authorities point to the exotic corners of Asia. Other boffins find roots in the Middle Ages, and a few discern a mutation of the Eighteenth-Century quadrille.

It took a long time for the can-can to land in Cincinnati. The first rumblings appeared in the local newspapers around 1860 with a few brief mentions about the sensation this dance caused in Paris. Mozart Hall, on Vine Street just north of Fountain Square, seems to have been the first Cincinnati venue to present the can-can locally. The Daily Gazette [10 March 1868] approved:

“Undine [a sort of Victorian “Little Mermaid”] drew a very large house last evening. The scenes are splendid as ever, and their audiences lose none of their enthusiasm. The new feature of the evening, the Can-Can, was a perfect success, eclipsing the former ballet completely.”

Among the Cincinnati theatrical community, anything that sold out one theater was soon added to the bill at several other stages and so it was with the innovative can-can. The Gazette [8 July 1868] reported that a newly redecorated Wood’s Theater, across the street from Mozart Hall, now offered this “fancy dance”:

“The little theater on Vine Street is so clean, with its new paint, and so cool, with its lace curtains, and its company so good, that there is little wonder that it is crowded nightly. The programme is full and complete, and very attractive. The rage for fancy dancing has got into the company, and can-can is given nightly.”

Only the Cincinnati Enquirer grumbled about the new can-can fad, but even the staid “Grey Lady of Vine Street” devoted a couple of lines [20 July 1869] in defense of the dance, quoting an otherwise unidentified “Cincinnati lady”:

“Now, I believe I know enough to know when a dance is improper. To me the can-can is full of all grace and refinement and bewitching charms. And I believe it is the fault of those horrid newspapers that have said so much about it.”

Just three days later, the Enquirer, presumably in its role as a “horrid newspaper,” editorialized [23 July 1869] against a production offered by Yale’s concert hall and saloon on Walnut Street:

“The Can-Can is not the most moral thing in the world when put forward in its most presentable shape. As rendered by the depraved creatures on Walnut Street it is filthy, obscene and disgusting, without arising to the dignity of the lascivious.”

The Enquirer rejoiced when the proprietor, whose name is variously reported as Phillip Yale, G. Wilkins Yale and J. Croissant-Yale, was arrested a week or so later. The competing Commercial Tribune reported the arrest [2 August 1869] but noted that the key witnesses for the prosecution were all Enquirer reporters:

“The local reporters of the Enquirer, who have assumed to determine the exact degree of immorality characterizing the can-can, as danced in the Walnut Street cellar, have been subpoenaed as witnesses against Yale, and will probably make some interesting revelations concerning this indecency, as compared with the many other indecencies which they seem to have seen.”

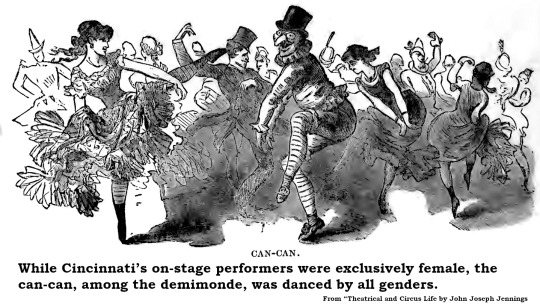

The Enquirer’s campaign drove the Yale family out of town. One news item had one of Yale’s sons accompanying one of the can-can dancers, Nellie Whitney, on a train eastward. The article specified that she danced at the Yale saloon on Walnut Street and identifies her as a “cyprian,” in other words, a prostitute. That could be some libelous hyperbole or it could be accurate, but it emphasizes the Enquirer’s objection to women dancing the can-can. While Cincinnati’s on-stage performers were exclusively female, the can-can, among the demimonde, was danced by all genders at Cincinnati’s bohemian soirees.

Despite the Enquirer’s disdain, the can-can continued its invasion of the Queen City. Just as the Yales closed their saloon, an advertisement appeared in the Commercial Tribune [14 August 1869] that Mademoiselle Aline Lefavre, who claimed to have introduced the can-can to the United States, would appear nightly at the Variety Theater on Race Street. In its advertisements, the Variety described Mlle. Lefvare as “the most beautifully formed woman in the world.”

The Commercial Tribune [3 May 1870] observed a sort of irony at work in the city’s esthetic morals. An exhibition that month at Wiswell’s Gallery, largely supported by charging admission to view paintings of “the type men like” as they used to say, featured a canvas depicting a very nude woman titled “Sleeping Beauty.” The paper’s art critic found it interesting that the can-can was condemned while a fully nude woman was celebrated:

“It was formerly a subject of animadversion that our ball-room belles dressed very low down in the neck – that is, wore no clothes much above the pit of the stomach; but had they gone in and become decollete down to their heels, that would simply have been Art – High Art. We see, too, how the moral comes in; to see the lady of the Can-Can is shocking, and we call for the police, but seeing her at second hand, through the eyes of the artist, it is great, and the price is all the same – only twenty-five cents.”

Perhaps the Commercial Tribune convinced the Variety Theater on Race Street to lean into the fine art proposition, because that establishment soon began offering, in addition to the can-can, an exhibition of “tableaux vivants” or “living pictures” in which women, clad only in flesh-colored tights, posed in the manner of Greek statuary or famous paintings. This despite the proprietor enduring several stints in the Workhouse on charges of operating a disorderly house.

Not to be outdone, the Vine Street Opera House announced a program headlined by “The Queen of the Serio-Comic Vocalists” Jennie Engle, Irish comics Mullen and McGee, as well as living pictures, the can-can and something billed as “weird dance.”

The show, it seems, must go on. And so it did. The forces of propriety and the minions of moral turpitude held an uneasy truce throughout most of the 1870s, with an arrest here while a new show popped up there, like whack-a-mole.

The fragile peace was broken dramatically in 1877 by the National Theater who booked Madame Ninon DuClos’ “Dizzy Blondes” for an extended engagement. The troupe claimed to specialize in the authentic Parisian can-can regardless of the reality that Mme. DuClos’ origins lay a lot closer to Dublin than Montmartre. Even though the Blondes were hauled into court and although they had been kicked out of Indianapolis, the show went on in Cincinnati for months. The Cincinnati Star [1 December 1877] simply sighed:

“The Dizzy Blondes at the National Theater have captivated a number of our young men, who come home exclaiming: “Did you ever?”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet Kit Kittredge!

Margaret Mildred Kittredge was born on May 19th. Her year is 1933 and she is incidentally modern. She lives in Cincinnati, Ohio, with her older brother Charlie, her mother Margaret, and her father Jack. She likes writing newspapers for her household, playing baseball, and going on big adventures with her friends (even if they get her into trouble). When she grows up, Kit wants to be a journalist.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

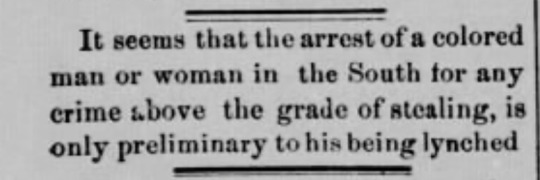

Imagine being lynched for petty crime's because of your skin color.

Cincinnati, Ohio 📍 Indianapolis, Indiana 📍

Publication: The Indianapolis Leader

Issue Date: May 7, 1881

#cincinnati#ohio#indianapolis#indiana#the south#lynching#africanamericanhistory#u.s. history#newspapers

0 notes

Text

Blooding Rite 1/1

The first time Alastor sees a man die, he's surprised.

He'll laugh himself sick much later at the very concept of being surprised at someone dying in a trench, on the front lines of the battlefield, in the middle of what the newspapers are starting to call 'The War to End All Wars'.

Not now though, as he stares at the bloodied remains Lt. James' jaw, hanging off his face as he stumbles back from the radio, his headset miraculously still attached, pulling the entire damned radio down on top of him as he collapses.

Lt. James, from Cincinnati, who moments earlier had been shouting that Alastor best be prepared to go over the top with the antenna, because their reception is absolute dog shit down here what with it pissing rain.

His mind is focused on how this scenario doesn't make sense: He's halfway out of the trench waving a metal baton in the air, desperately searching for a signal, while only James' head is visible -- how did James end up catching the bullet and not him?

There will be time to ponder later about the fickle proclivities of Death, but in the moment he's far too distracted about being tackled down into the trench himself by a blur of gray wool.

Animal instincts take over as soon as his back hits the dirt. Even with the wind knocked out him he's biting, clawing, kicking at the fucking Gerry on top of him. He can feel the kiss of the knife's blade against his palms and forearms as he struggles to protect the softest parts of himself, when he's not being clobbered over the face with the butt of a pistol.

The first time Alastor kills a man is only a few breaths later when he manages to get his own pistol out of the holster and blindly aim for the bastard's temple.

He hits his mark. The Gerry's body sags down on top of him, pushing him deeper into the mud. He's taking large, open-mouthed gasps of air, like a stunned fish out of the water -- at least until the gore coating face starts dripping into his mouth. That returns him to reality in a real jiffy.

He shoves the body off of him, rolling into a crouch as he swipes at his face with his sleeve in a futile effort to clean it. Tries to listen between the thunderous beat of his heart to what is going on around him.

Battle -- gunshots and screaming -- close but not too close, not near enough to him to panic. When he can stand, a quick glance over the top reveals no more Gerries waiting to pounce in the clearing fog, and he can hear his heartbeat start to quiet.

On impulse he pries the Gerry's pistol from his hand, and checks the cartridge.

Empty. Last bullet for Lt. James.

Makes sense, he supposes -- kill the radio operator, cut off communications, then kill the damned fool playing flag pole...

Better luck next time, old chum.

He tosses the pistol down as the sounds of the radio start to filter into his ears.

The radio is still working, that's good.

He pulls the antenna out of the muck and stumbles towards the operator's desk.

Stabs the antenna into the soft dirt on top of the trench.

Rights the operator's desk.

Hauls the radio back onto the desk as gently as he can considering how heavy it is.

Checks his sightlines for any imminent enemy incursions; finds none.

Hauls Lt. James' corpse to lie to one side of the desk.

Reconnects the cable connecting the battery cell to the antenna.

Pulls on the headset.

Ignores the tacky-wet sensation as the ear piece drags across his cheek.

Takes a deep breath.

Remembers that the northerners back at base camp will not understand him unless he talks in that flat, nasal accent they taught him back in special training.

Turns the microphone on and reports in.

"Ni-yen Too Easy, Report. Ni-yen Too Easy, Report." Base command replies.

Microphone's broken. Well fuck.

He slams the headset down in frustration, only for a loud squawk to emanate from the ear pieces.

"Ni-yen Too Easy, was that you?"

Microphone's only mostly broken then... He can work with that.

Pulls back on headphones.

Still ignores the tacky-wet sensation on his cheek.

Uses his pocket knife to start tapping out a message in Morse code on the mouthpiece of the headset.

"Copy that, Ni-yen Too Easy. Gerries sighted on the Eastern flank."

Well, no shit.

He can hear the battle drawing closer.

It takes twelve hours before Alastor finally receives the order to retreat to hand off to the runner to give to command. There's no other signalman close enough to lend him a spare headset, let alone relieve him from his post for as much as a piss break.

Twelve hours tapping out updates and confirmations in the alphabet he learned at his mother's knee, hiding under her desk as she worked.

None of them know Morse code like he does anyway.

By the time he's loaded up the radio and jumped into the back of the transport truck his head is throbbing with the mother of all headaches. His ears feel like they're bleeding. He does his best to hide the trembling in his limbs.

It takes hours to get back to base, and even though he's dead on his feet, he's more ravenous than tired, and lines up outside the canteen.

In a few days, once the casualties are accounted for and word spreads from the signal battalion about his field improvisation skills, they'll start calling him 'Radio Demon' because only someone in league with the Devil himself would have decided to stay in that hellhole, at his post for as long as he had, instead of retreating somewhere safer.

They make it sound like some altruistic act for his "brothers" -- in truth, he hadn't been thinking clearly enough to even realize that retreat was an option. If he had, he would have booked it as fast as possible away from the front line.

Tonight, though, the Radio Demon is rewarded for his heroism with a plate of congealed chipped beef on soggy toast and directed towards some damp benches, sitting out in the rain. The storm's onslaught has taken down one of the base's two mess tents, and Command cannot abide the idea of white officers having to eat with colored officers.

Only the finest for all these brave men dying on the front lines after all.

#hazbin hotel#alastor#hazbin alastor#alastor hazbin hotel#alastor the radio demon#the radio demon#hazbin hotel fanfiction#Hazbin Hotel fanfic

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Local television news broadcasters are airing suspiciously similar attacks on Joe Biden’s mental acuity and how it will affect the coming election—and it appears to be part of a coordinated effort.

The Sinclair Broadcast Group owns or operates 185 local television stations across the country, (#WKRC Cincinnati #CBS Channel 12) and dozens of their stations aired a segment from national correspondent Matthew Galka citing a Wall Street Journal article that makes dubious attacks on Biden’s age and mental awareness. The stations that aired the segment introduced it using startlingly similar, if not identical language, the Popular Information and Public Notice newsletters reported.

It’s not the first time Sinclair, owned by right-wing businessman David D. Smith, has appeared to be running a conservative propaganda campaign. Infamously in 2018, dozens of the company’s TV stations were caught airing an identical editorial about the dangers of biased and false news. This time around, the #RupertMurdoch owned #WallStreetJournal, as well as Murdoch’s cable news stations #FoxNews and #FoxBusiness, have gotten in on the act.

Smith himself has long been a donor to Republican causes through his family foundation, which counts right-wing nonprofits Young Americans for Liberty, Project Veritas, Turning Point USA, and Moms for Liberty among its recipients. In 2016, the Donald Trump campaign cut a deal with Sinclair that exchanged extensive access to Trump in return for positive coverage without fact-checking. That same year, Smith met with Trump and reportedly told him, “We are here to deliver your message.”

Earlier this year, Smith purchased The Baltimore Sun, insulting its staff and laying out a vision to steer it in the conservative direction of his TV stations. It’s quite obvious that Smith, Murdoch, and other conservative millionaires and billionaires are taking over as many media outlets as possible to push right-wing political propaganda, with the Biden age article and subsequent TV segments as examples of the end product they want. They’re finding vast opportunities in America’s declining news deserts, as well as the skeletal newspapers gutted by hedge funds and profit-seeking corporations. It doesn’t just bode well for the next election, but also portends a scary future for American democracy for decades to come."

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jackie Gleason was a hedonistic ne’er-do-well for his entire career. Long before he was famous he convinced the producers of the Broadway sketch comedy revue The Duchess Misbehaves to advance him a month’s salary, which he promptly wasted on booze, broads and card games. When he stumbled through rehearsals hungover and half drunk, he was fired and replaced with the burlesque comedian Joey Faye.

Broadway producer David Merrick had similar problems when Gleason starred in his production Take Me Along. He called Gleason “a big, fat drunken slob … who was appearing night after night virtually drunk on stage.”

Gleason and booze went hand in hand. Even his famous nickname – The Great One – was bestowed by Orson Welles when the larger than life duo got absolutely hammered together.

One afternoon when he was wasted on the golf course, Gleason engaged in a golf cart race, driving wildly out of control with his manager Bullets Durgom in the passenger seat. When the cart crashed and capsized, Durgom was hospitalized for a fractured spine.

Gleason was among the most popular personalities in America, but he was not without his haters. Television created a new subgenre in American media – the irate letter writer. Newspapers in the 1950s were filled with angry letters to the editor complaining about everyone and everything. In the decades prior to “mean tweets” it was the letters to the editor section where irate cranks expressed their lunatic feelings.

“Nothing Jackie Gleason does will ever look good to me,” wrote a viewer to The Cincinnati Enquirer in 1955. “He is not a comedian. He is a fat tub of lard who talks too much. What ever happened to his diet? I am glad he is off for the season. – No Gleason Fan.”

30 notes

·

View notes