#ceresole

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nijinska Scrapbook of Ballets Russes: 1923-1924

#talking#papillons#op. 2#ballet#casino de monte-carlo#palais des beaux-arts#theatre de monte-carlo#ballets russes#daphnis et chloe#le mariage d'aurore#mariage d'aurore#les biches#biches#les tentations de la bergere#tentations de la bergere#petrouchka#prince igor#danses polovtsiennes du prince igor#danses polovtsiennes#sheherazade#une education manquee#education manquee#l. bakst#leon bakst#borodine#alexandre borovskky#h. casadesus#ceresole

0 notes

Text

A Ceresole.

Opel Astra che puzza di fumo.

L'ho presa da poco e pagata un casino.

Ma è lì che andiamo.

Con una station wagon da 90.000km.

Nera. Oggettivamente brutta. Un baule enorme.

C'è chi ci rivede un'auto da cassamortaro.

Ma li andiamo.

Dove volevi andare tu.

Vestito di tutto punto, con il tuo coltellino sempre in tasca e la tua voglia di scherzare.

Macchina piena oserei dire.

Strade? Ardue e pericolose.

Ma è lì che vuoi andare.

"Un giorno quando andrò a Ceresole..." e lo dicevi per intendere ben altro.

Ma li siamo andati. Con quella macchina. Nera. Da cassamortaro.

E una volta arrivati?

"Andiamo ancora più su?"

E così abbiamo fatto.

A Ceresole, dove il Piemonte incontra la Valle d'Aosta.

Abbiamo mangiato una buonissima polenta.

Abbiamo riso e scherzato.

Abbiamo comprato pure la tanto desiderata calamita.

E poi siamo tornati. A casa. Nelle tue valli, che però la coincidenza ha voluto fossero anche le mie.

E dopo tanti anni da quel viaggio, hai deciso di tornare la.

Ce lo dici da qualche mese. Ci hai chiesto di salutarti per bene più e più volte.

L'avevi promesso che saresti tornato.

Ma questa volta da solo. Senza Opel Astra che sa di fumo. Nera.

Ma col cassamortaro.

Nonno... Non era così che doveva andare credo. Ma così è andata.

Hai saputo darci le dritte giuste e gli insegnamenti necessari anche in quel letto d'ospedale.

Quell'ospedale che mi ha visto nascere li quasi per caso.

E che ti ha portato lentamente al capolinea.

L'unica gioia è sapere che hai deciso di salutarci a casa tua. Dove la mia infanzia e la mia adolescenza si sono realizzate.

Quel luogo magico da Hobbit, quel posto che non vede strade ma solo monti, lì dove i suoni sono solo l'acqua del fiume Stura e degli uccellini al mattino.

Grazie per tutto quello che mi hai dato. Ed è stato davvero davvero tanto.

E grazie per avermi fatto conoscere la dignità. La capacità di esserci senza urlare. L'intelligenza degli sguardi attenti e sapienti. La dote di dire in modo pungente e simpatico verità scomode e piene di retorica.

Sei e sarai sempre ricordato come un uomo eccezionale e unico nel suo genere.

Ti voglio bene Nonno.

PS: con la tua dipartita Nonna sarà un uccello con un'ala spezzata. Dalle forza sempre, dovunque tu sia. Abbiamo bisogno che in qualche modo torni a volare, perché il suo mondo è quello che ci salva dal mondo reale. Grazie.

0 notes

Text

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

#estate #CeresoleReale #piemonte #VisitPiemonte #igersceresolereale #yallerstorino #ig_ceresolereale #LOVES_UNITED_PIEMONTE

0 notes

Text

Ceresole Reale, Italie

Rando du 31/08/2023

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lydia Lunch & Swans, White Columns, New York (1983).

Photo by Catherine Ceresole.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ikue Mori (DNA) photographed by Catherine Ceresole

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Piemonte (2) (3) by Stefania Urbini

Via Flickr:

(1) Cold faith, San Clemente. (2) (3) Ceresole Reale.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-violent Direct Action

A few months before he died, William James gave a lecture [4] in which he put himself “in the anti-militarist party’* but declared that “a permanently successful peace-economy cannot be a simple pleasureeconomy,” and insisted that “‘we must make new energies and hardihoods continue the manliness to which the military mind so faithfully clings.” For “martial virtues must be the enduring element” in a peaceful society, and anti-militarism must develop its own form of militancy. Like many other people before the Great War, he felt sure that “the martial type of character can be bred without war,” and he called for an “army against nature” to replace armies against fellowmen. (This idea/ of a peace-army is an old one, and is the basis of Pierre Ceresole’s Service Civile Internationale, whose British section is the International Voluntary Service.) But ten years after the Great War, Walter Lippmann pointed out [5] that “it is not sufficient to propose an equivalent for the military virtues. It is even more important to work out an equivalent for the military methods and objectives.” War is “one of the ways by which great human decisions are made,” so “the abolition of war depends primarily upon inventing and organising other ways of deciding those issues which hitherto have been decided by war.” Political anti-militarists had often assumed that these issues could be decided by another form of war, violent revolution, and religious pacifists had often assumed that they could be eliminated altogether by mutual conciliation. Lippmann would have none of this : “Any real programme of peace must rest on the premise that there will be causes of dispute so long as we can foresee, and that those disputes have to be decided, and that a way of deciding them must be found which is not war.”

So the problem is the positive one of replacing war as well as the negative one of resisting it; in fact we have to replace war before we resist it, since our resistance must by nature be both a moral and a political equivalent to war. The irony is that the solution has been there all the time; for the insoluble Kantian antinomy between violent resistance and non-resistance is only superficially insoluble and submits quite easily to Hegelian dialectic. The thesis is violent resistance, the antithesis is non-resistance, its opposite : and the synthesis is non-violent resistance, or passive resistance. We have already seen how this ideological change occurred historically, and the only problem now is to look a bit deeper. Lassalle said “passive resistance is the resistance that doesn’t resist.” Is this necessarily true?

The trouble is that passive resistance is usually thought of as an inner-directed and ineffective technique, bearing witness rather than doing something (as it tends to be, for instance, in the hands of individual’ conscientious objectors), and both the idea and the history of other-directed and effective passive resistance have been buried by the human obsession with violence. The suggestion that passive resistance is the solution to tyranny runs underground in political thought until the 16th century French humanist, Etienne de La Boetie, wrote an essay [6] advocating it as a way out of the “willing slavery” on which tyrants based their power: “If nothing be given them, if they be not obeyed, without fighting, without striking a blow, they remain naked, disarmed, and are nothing.” And he meant it politically as well as psychologically when he said, “Resolve not to obey, and you are free.” The same suggestion appears again in Shelley’s Mask of Anarchy[7]:

Stand ye calm and resolute, Like a forest close and mute, With folded arms and looks which are Weapons in unvanquished war.

And this is closely echoed in the old syndicalist song :

Ce n’est pas a coup de mitrcdlle Que le capital tu vaincras; Non, car pour gagner la bataille Tu n’auras qua croiser les bras,

“You have only to fold your arms.” The 19th century Belgian socialist, Anselm Bellegarrigue, developed a “theory of calm” in which revolution could be achieved by nothing more than “abstention and inertia”. And the industrial or pacifist general strike is only a special form of passive resistance; while the plan for “mobilisation against all war” which the Dutch pacifist, Bart de Ligt, put to the conference of the War Resisters’ International in 1934 s is simply the old pacifist and industrial general strikes combined and described in detail.

But collective passive resistance isn’t just another clever idea which has never been tried — history is full of examples. The most obvious method is the mass exodus, such as that of the Israelites from Egypt in the Book of Exodus, that of the Roman plebians from the city of Rome in 494 BC (according to Livy), that of the barbarians who roamed over Europe during the Dark Ages trying to find somewhere to live, that of the Puritans who left England and France in the 17th century, that of the Jews who left Russia around 1900 and Germany in the 1930s, that of all the refugees from Communist countries since the last War. Or there is the boycott, used by the American colonies against British goods before 1776, by the Persians against a government tobacco tax in 1891, by the Chinese against British, American and Japanese goods in the early years of this century, by several countries against South African goods today, and in a different sense by the negroes who organised the bus-boycotts in Montgomery in 1955–56 and Johannesburg in 1957. Then there is the political strike, such as the first Petersburg strike in 1905, the Swedish and Norwegian strikes against war between the two countries in the same year, the Spanish and Argentine strikes against their countries’ entry into the Great War, the German strike against the Kapp putsch in 1920, and dozens of minor examples every year — in fact all non-violent strikes are simply a familiar form of passive resistance. There is also the technique of non-co-operation, as used by the Greek women in Lysistrata, by the Dutch against Alva in 1567–72 (see the film La Kermesse Herdique), by the Hungarians under Ferenc Deak against the Austrian regime in 1861–67 (consider how Lajos Kossuth is much more famous than Deak because he was much more romantic — and much less successful), by the Irish against the British regime in 1879–82 (until Parnell ratted by making the Kiimainham Treaty with Gladstone), by the German sailors against their belligerent admirals in 1918, and by the Germans against the French occupation of the Ruhr in 1923–25; when this technique is used against an individual it is called “sending to Coventry” — the people mentioned above sent their oppressors to Coventry.

A more familiar technique is that of general resistance to oppression without the use of violence, because violence would be useless or unnecessary — as used by the Jews against Roman governors who brought images into Jerusalem in the 1st century AD, by the English against James II in 1686–87, by the German Catholics and Socialists against Bismarck in 1873–83, by the English Non-conformists against the Education Act in 1902 and the English trade-unionists against the Trade Disputes Act of 1906, by the Finns against the Russian regime’s introduction of conscription in 1902, by the Koreans against the Japanese regime in 1919 and the Egyptians against the British puppet regime in the same year, by the Samoans against the New Zealand regime in 1920–36, by the Norwegians and Danes against the Nazi regime in 1940–43, and by the Poles and Hungarians against the Russian regime in 1956 (with a disastrous climax in Hungary). All these techniques represent ways of resisting without using violence, but in most cases violence would have been used by the resisters if they had thought it would work. The change comes when non-violence is adopted because it is expected to work better than violence, and in particular when the non-violent action is directly against the source of dispute. When Thoreau refused to pay his poll-tax he was using civil disobedience; when he put a negro slave on the Canada train he was using direct action. And when non-violent direct action is used collectively it becomes an entirely new technique.

Whenever we feel that pacifism must stop being passivism and become activism, that it must somehow take the initiative and find a way between grandiose plans for general strikes which never have any reality and individual protests which never have any effect, that it must become concrete instead of abstract — when in fact we decide that what is needed is not so much a negative doctrine of non-resistance or non-violent passive resistance as a positive doctrine of non-violent active resistance, not so much a static peace as a dynamic war without violence — then our only possible conclusion is that the way out of the morass is through mass non-violent direct action. What sort of mass non-violent direct action? The answer was given more than half a century ago not by a war-resister at all but by a man who was leading resistance to racial oppression in South Africa, by an obscure Gujarati lawyer called Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Gandhi came to South Africa when he was only 23, with a brief from a Muslim firm in his home-town of Porbandar for a complicated commercial case involving its Pretoria branch. He got the case settled out of court within a few months, but in 1894 he decided to stay in South Africa to organise Indian resistance to the colour- bar. After ten years he had become the trusted leader of the Indian community, but there was nothing remarkable about his career. What happened then (and what made him so important in the history of non-violent resistance) was that he became a “charismatic” leader — Max Weber’s word for one who seems to have superhuman qualities and exerts inexplicable influence over his followers and opponents.

The significant date for the beginning of this change and for the birth of satyagraha is 11 September 1906, when Gandhi administered an oath of passive resistance against Transvaal’s “Black Bill” to 3,000 Indians in the Imperial Theatre at Johannesburg. The two great operations of 1907–09 and 1913–14 which followed made him and his technique famous, and soon after his return to India in 1915 he began using satyagraha against the British raj and against local injustices of all kinds. There were local operations at Viramgam (1915), Champaran (1917), Ahmedabad (1918), Kheda (1918), Kaira (1918), Kotgarh ,1921), Borsad (1923), Vaikam (1924–25), Nagpur (1927), Bardoli (1927–28), and in the Native States (1938–39), and there were three pairs of national operations, in 1919 and 1920–22, in 1930–31 and 1931–32, and in 1940–41 and 1942 — all directed by Gandhi himself or by his lieutenants. In the end, as everyone knows, the British Labour Government granted (granted!) independence to India after partition; and then, as everyone also knows, only a few months later, in January 1948, Gandhi was shot by a Hindu fanatic called Vinayak Godse — killed by his own like Socrates and Jesus. He had said, “Let no one say he is a follower of Gandhi,” but his charisma, his strange influence, lives on. The Indian Government and the ruling Congress party claim to follow him; but his real successor is not Jawaharlal Nehru, the Prime Minister of a new raj, but Vinoba Bhave, the leader since 1951 of the agrarian Bhudan movement — not so much Congress as the Praja Socialists. Like Albert Schweitzer (and,. of all people, Emma Goldman), Gandhi has become a useful saint whose name is invoked by people for whom his message means nothing. But he has genuine followers outside India as well, Albert Luthuli in South Africa, Kenneth Kaunda in Rhodesia, Martin Luther King in the USA, Danilo Dolci in Sicily, and Michael Scott — people who have learnt to use satyagraha from his example, finding it the only form of valid political action in the shadow of the concentration camp and the Bomb.

But what is satyagraha? It is a Gujarati word coined by Gandhi to replace the term “passive resistance”, which he disliked because k was in a foreign language and didn’t mean exactly what he meant. It is usually translated as “soul-force”, but the literal translation is “holding on to truth” (we should imagine a French or German leader in his place coining a word like veritenitude or wahrhaltung). For Gandhi, the goal was truth and the way was non-violence, the old Indian idea of ahimsa, which includes non-injury and non-hatred and is not unlike agape (or love) in the New Testament. But in the Indian dharma, as in the analogous Chinese too, the way and the goal are one — so nonviolence is truth, and the practice of ahimsa is satyagraha. This sort of reasoning can lead to meaningless metaphysical statements (such as the one that since non-violence is truth, violence is untruth and therefore doesn’t really exist), but it also leads to a healthy refusal to make any convenient distinction between ends and means. “We do not know our goal,” said Gandhi. “It will be determined not by our definitions but by our acts.” Or again, “If one[8] takes care of the means, the end will take care of itself.” This is a refreshing change from traditional political thought in which means, as Joan Bondurant says, “have been eclipsed by ends” — most European philosophers have tended to believe that if one takes care of the ends, the means will take care of themselves, with the results that we all know.

There has been much rather fruitless discussion of the exact meaning of satyagraha.[9] We are told it isn’t the same as passive resistance, which has been given another new name — duragraha — and is thought of as stubborn resistance which negatively avoids violence rather than as resistance which is positively non-violent by nature, as satyagraha is. Duragraha is obviously just a subtle method of coercion, but satyagraha, according to Gandhi, “is never a method of coercion, it is one of conversion,” because “the idea underlying satyagraha is to convert the wrong-doer, to awaken the sense of injustice in him.” The way of doing this is to draw the opponent’s violence onto oneself by some form of non- violent direct action, causing deliberate suffering in oneself rather than in the opponent. “Without suffering it is impossible to attain freedom,” said Gandhi, because only suffering “opens the inner understanding in man.” The object of satyagraha is to make a partial sacrifice of oneself as a symbol of the wrong in question. “Non-violence in its dynamic condition means conscious suffering. It does not mean meek submission to the will of the evil-doer, it means pitting one’s whole soul against the will of the tyrant.” Here is the dynamic war without violence that we needed, the moral and political equivalents of war — and at the same time a way of resisting war itself.

Richard Gregg has ingeniously explained the psychological effect of satyagraha as follows :

“Non-violent resistance acts as a sort of moral ju-jutsu. The nonviolence and good will of the victim act like the lack of physical opposition by the user of physical ju-jutsu, to cause the attacker to lose his moral balance. He suddenly and unexpectedly loses the moral support which the usual violent resistance of most victims would render him. He plunges forward, as it were,, into a new world of values. He feels insecure because of the novelty of the situation and his ignorance of how to handle it. He loses his poise and self-confidence. The victim not only lets the attacker come, but, as it were, pulls him forward by kindness, generosity and voluntary suffering, so that the attacker quite loses his moral balance. The user of non-violent resistance, knowing what he is doing and having a more creative purpose and perhaps a clearer sense of ultimate values than the other, retains his moral balance. He uses the leverage of superior wisdom to subdue the rough direct force or physical strength of his opponent.”

Everyone who has taken part in non-violent direct action knows how true this is, and knows the strange sense of elation and catharsis that results; ha can’t lose, since if he is attacked he wins by demonstrating the wrong he came to protest against, and if he is not attacked he wins by demonstrating his moral superiority over his opponent. But this means that he must choose non-violence because he is strong, not because he is weak. Gandhi always reserved particular scorn for what he called the “non-violence of the weak” (such as that of the pre-war and postwar appeasers of aggression), and insisted that non-violence should be used as a deliberate choice, not as a second-best. “I am not pleading for India to practise non-violence because she is weak,” he said. “I want her to practise non-violence conscious of her strength and power.” Gandhi was no weakling, in any sense. “Where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence,” he said, “I would advise violence ... But I believe that non-violence is infinitely superior to violence.” This is significantly like what Garrison said a hundred years ago between John Brown’s putsch at Harper’s Ferry and the outbreak of the American Civil War : “Rather than see men wearing their chains in a cowardly and servile spirit, I would as an advocate of peace much rather see them breaking the head of the tyrant with their chains.” It is typical of Gandhi that, although his first principle was non-violence, he raised Indian ambulance units to serve in the British Army for the Boer War, the Zulu “rebellion” of 1906 and the Great War, and in 1918 he even began a recruiting campaign in India. After independence, he said, he “would not hesitate to advise those who would bear arms to do so and fight for their country.” He also seems to have thought that violent self-defence against hopeless odds and a ruthless enemy (such as the Warsaw Ghetto rising in the spring of 1943) almost qualified as a form of non-violence. But his usual advice was of course to resist oppression without any violence at all. He had no hesitation in advising the Chinese, the Abyssinians, the Spanish Republicans, the Czechs, the Jews, the British, and anyone else who was attacked to offer satyagraha. For even the physically weak or outnumbered can use the non-violence of strength, and when they use it together they are no longer physically weak — “Ye are many, they are few.” This is the reverse of “peace at any price”; it is peace at my price. It is saying to the aggressor : You can come and take my country and hurt and even kill me, but I shall resist you to the end and accept my suffering and never accept your authority. For a time you will prevail, but I shall win in the end. This is not mere passive resistance, for satyagraha, as Gandhi said, “is much more active than violent resistance.”

And yet Gandhi still denied any coercive intention and often treated his opponents to chivalrous gestures (calling off the 1914 operation when there was a strike by white railwaymen, not using the Vaikam temple-road in 1924 when the police cordon was removed) and to overchivalrous compromises (with Smuts in 1908 and with Lord Irwin in 1931). Richard Gregg is quite sure that “non- violent resistance is a pressure different in kind from that of coercion,” and this is the view of most Gandhians; but Joan Bondurant has decided that “throughout Gandhi’s experiments with satyagraha there appears to be an element of coercion,” albeit “coercion whose sting is drawn.” Reinhold Niebuhr pointed out Gandhi’s mental confusion in denying any coercive intention when he was obviously coercing his opponents, and attributes it to political necessity. Clarence Case defined satyagraha without reservation as “non-violent coercion.” The truth is surely that there are two sides to coercion, and while a satyagrahi may be quite sincerely innocent of the slightest wish to coerce, the person at the receiving end of his satyagraha may feel very dceidedly coerced. Some people have even called the technique “moral blackmail”. Whatever Gandhi felt about what he was doing during his campaigns, there was no doubt in the minds of his South African, British and Indian opponents about what was happening to them. Satyagraha was “nothing but the application of force under another form,” complained Lord Irwin, the Viceroy who had to deal with the great Salt March in the spring of 1930 (and who, as Lord Halifax, was later the Foreign Secretary at the time of Munich). In the end the precise amount of coercion in satyagraha and even the precise definition of satyagraha are rather academic points. The only important point is whether satyagraha works, and how it works; if it can’t convert an opponent it is clearly better that it should coerce him gently rather than violently. For as Gandhi said, “You can wake a man only if he is really asleep; no effort that you may make will produce any effect upon him if he is merely pretending sleep.” And so many men are doing just that.

Satyagraha should be studied in practice rather than in theory. It “is not a subject for research,” Gandhi told Joan Bondurant (who happened to be carrying out research into satyagrahaX “You must experience it.” No doubt, but first you must observe it in action; and one very interesting thing about Gandhi’s campaigns is that they failed in direct proportion to the size of their objectives. The Viramgam tariff-barrier and the Champaran indigo racket and the Kaira forcedlabour custom and the Vaikam road-ban on untouchables were all broken, but were the Indians in South Africa freed—or even those in India? Gandhi called himself “a determined opponent of modern civilisation” and insisted that independence meant more than “a transference of power from white bureaucrats to brown bureaucrats”. But swaraj, which meant self-rule before it meant Home Rule, and which was to change so much, has come to mean little more than government by Indians instead of Englishmen, and it has hastened the irresistible advance of modern civilisation throughout the sub-continent. Who wears home-spun hhadi now? Gandhi won the little battles and lost the big ones. No doubt the little battles might have been lost too if he hadn’t been there, and the big defeats might have been much bigger (though Subhas Bose said he made things worse himself); but his own victories were still minor ones. Nor were they bloodless— the Amritsar massacre at the Jallianwalla Bagh on 13 April 1919 was a direct result of his campaign, and he himself admitted a “Himalayan miscalculation”; and he wasn’t able to do much to stop the frightful communal riots after Partition, though he tried. He always succeeded most when he attempted least. His ideal was reconciliation, but the only opponents he reconciled were the ones who accepted his terms. The Boers simply stepped back to gain time before making a bigger jump, and the English simply lost their patience with the inscrutable orientals who kept outwitting them. Gandhi didn’t win them over like some gentle modern Christ-~he threw them neatly over his shoulder like some modern Jack the Giant-Killer. The important thing about him isn’t what he tried to do but what he did.

We should bear this in mind when we use his ideas. He linked many things to satyagraha which aren’t actually essential to it. His religious ideas (non-possession, non-acquisition, chastity, fasting, vegetarianism, teetotalism) and his economic ideas (self-sufficiency, handlabour, back to the land) don’t necessarily have anything to do with the satyagraha that is practised by people after Gandhi. If it is objected that he wouldn’t have liked it, remember what he said to similar complaints about himself: “It is profitless to speculate whether Tolstoy in my place would have acted differently from me.” He wasn’t Tolstoy; we aren’t Gandhi. Everyone has a unique background and personality. Gandhi came from the puritanical Vaishnava sect and the respectable pe>$t-bourgeoi$ Modh Bania sub-cast, and he had a profound sense of sin (or obsessive guilt complex). We don’t have to share this background and personality to qualify for non-violent direct action. We shouldn’t worry because he said satyaghara “is impossible without a living faith in God,” especially when he also said that “God is conscience. He is even the atheism of the atheist.” When he talked about the ramaraj (the kingdom of God) he meant not a Hindu theocracy but a society based on sarvodaya (the good of all), which is exactly what we want Nor should we worry because he said “it takes a fairly strenuous course of training to attain to a mental state of non-violence,” when it has been found that inexperience and untrained people can be completely non-violent. When Gandhi rejected bhakti and jnana for karma, he was only saying that love and knowledge aren’t enough, that direct action is necessary too. When we feel rather horrified by his plan for a sort of revised seventh age of man — sans meat, sans drink, sans sex, sans everything — we should remember that his personal ideal was moksha (release from existence, the same as nirvana) and his denial of self was intended to lead to a denial of life. But we can feel reverence for life according to our own traditions without sharing his eschatological opinions. We can make use of what he did without agreeing with what he thought.

What we should do — what indeed he would have wanted us to do — is to take from him what we can without being false to ourselves; so long as we follow the essential ideas of non-violence, self-sacrifice, openness and truth. “A tiny grain of true non-violence acts in a silent, subtle, unseen way,” he said, “and leavens the whole society.” So we should sow it. This is what the new post-war pacifists have done, and this is how they have at last discovered how war-resisters can really resist war.

#non violence#pacifism#non violent direct action#direct action#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

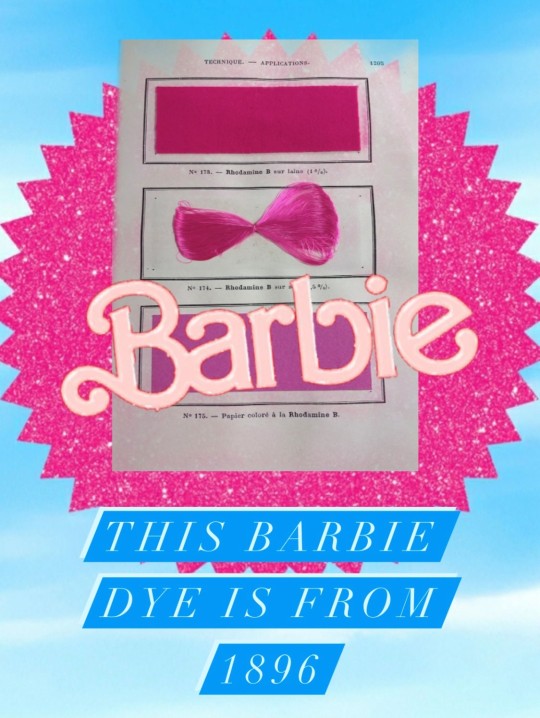

This is probably the most Barbie book that we have. The color was first created in 1887 by Maurice Ceresole and named Rhodamine after the Greek word for rose.

Traité des matières colorantes organiques artificielles, de leur préparation industrielle et de leurs applications, 1896.

#barbie#barbie filter#dyes#pink#rhodamine#barbiecore#dye books#colors#pink stuff#the barbie movie#barbie 2023#shades#shades of pink#othmeralia

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una pluriclasse con due alunni. Non si sgomita a Ceresole Reale per trovare un posto nella scuola più piccola d’Italia. La tengono viva, quest’anno, Raffaele ed Emanuele (che frequentano la seconda e la terza elementare) con la maestra Noemi, 22 anni appena.

Tanta freschezza, ieri mattina, per il primo giorno del nuovo anno scolastico. Ceresole, la perla alpina del Gran Paradiso a 1.600 metri di quota, conta 160 abitanti: riaprire la scuola ogni anno è tutto tranne che semplice. «Per noi sentir suonare la campanella è un enorme successo perché vuol dire che siamo riusciti a mantenere attivo un presidio fondamentale per la vita del paese», conferma il vicesindaco Mauro Durbano. Andare a scuola a Ceresole del resto, come viverci tutto l’anno, è una scelta di vita. Ed è in parte quello che è successo alla maestra Noemi Dalla Gasperina, fresca di laurea in Scienze dell’educazione, che comunque la montagna la conosce piuttosto bene visto che abita a Locana.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

E59: Ceresole Reale - Colle di Trione (28,8 km; 2601 hm)

Der See schien noch zu schlafen als ich loszog

Bis zum ersten Pass waren es knappe 1200 Höhenmeter und schon kurz nach dem kleinen Rundweg um den See ging es gleich richtig zur Sache - zunächst noch vor der Sonne geschützt durch einen Lärchenwald

später sah das ganze dann so aus:

doch der Blick vom Colle della Crocetta (2641m) entschädigte alle Mühen

Wieviel Glück kann man eigentlich mit dem Wetter haben?!

Der lange Abstieg war dann leider weniger schön, da meldeten sich hier und da mal meine Knie. Zum Ende hin lief ich durch eine Alpe, es roch ein wenig nach Kuhscheisse aber daneben auch noch nach frischer Milch - der Bauer hatte kurz zuvor seine Kühe gemolken

In Pialpetto gönnte ich mir in einem Restaurant eine Portion Gnocchi mit Erbsen und hinterher gleich noch zwei Eis - ich brauchte Zucker, da ich mich für einen zweiten Aufstieg an diesem Tag entschlossen hatte (ein hochgelegener Bergsee und eine trockene Nacht lockten mich zu Zelten). Nochmal 1600 hm bis zum Colle di Trione waren aber nochmal ein ordentliches Brett… Und es dauerte bis ich in den Tritt kam, die Hitze war Brutal. Kurzzeitig dachte ich sogar, dass ich es garnicht bis hoch schaffen werde, die Gelassenheit ging mir da kurzweilig verloren. Zum Glück führte der Weg entlang eines großen, kalten Gebirgsbach. Und dann musste ich leider feststellen, dass sich am Laghi di Trione schon reichlich Kühe breit gemacht und alles vollgeschissen hatten

Es half nichts, ich musste weiter Richtung Gipfel aufsteigen. Wie schon so oft auf der Tour wurde mein Mut und meine Ausdauer belohnt und ich fand den perfekten Platz!

Mit freier Sicht in das Grand Paradiso Massiv genoss ich einen traumhaften Abend, hatte kurzzeitig sogar Besuch von einem Steinbock

und bei untergehender Sonne gab ich mich einfach dem Moment hin

Und als wäre das noch nicht genug, erfüllte sich kurz nach Mitternacht ein lang ersehnter Traum - die Milchstraße, so klar und schön (iPhone Kamera leider nicht gut genug)

Danke!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mia mamma è pazza.

Dopo il trauma COVID che non ha ancora superato, è subentrato il trauma siccità.Ora è incazzata come una biscia perché vorrebbe svuotare la diga di Ceresole che non è proprio la vasca dei pesci del parchetto e cementificarla per evitare dispersioni nel terreno.Ovviamente l'ecosistema del lago è irrilevante.

Ora la chiudo in un ospizio

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#estate #CeresoleReale #piemonte #VisitPiemonte #igersceresolereale #yallerstorino #ig_ceresolereale #LOVES_UNITED_PIEMONTE

0 notes

Text

Ceresole Reale, Italie

Rando du 29/08/2023

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beastie Boys, White Columns, N.Y. (1983).

Photo by Catherine Ceresole.

21 notes

·

View notes