#category of godling

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nico's head bobs in a small nod, eyes sliding closed in a brief prayer for his mother. He'd spent years trying to find her spirit to little luck, and he'd almost lost himself in the search. Fortunately, even if he hadn't found is mother, he at least found some peace.

Fiddling absentmindedly with his ring around his thumb, he shrugs a little. "A travel around a lot, but usually I'm in Camp Half-Blood. It's on Long Island, New York," he explains, before squinting at the other, realizing her older brother might not know where any of those places are. "Uhm, it's kind of far away from Greece. Camp is one of the few places demigods can be safe though."

" the PRECIPICE of a tragic backstory, isn't it? " zagreus' smile falls off, but only slightly, " i am very sorry to hear about your mother. may she rest in peace. " he's never quite HEARD the overworld term italy in such blatancy before, but maybe he and thanatos had begun a conversation about it in passing. a conversation he'd hardly clung to closely to, it seems. though it may be a given, since the sun-warmed earth seemed to curse his presence. BUT WHEN DID HE EVER LET THAT STOP HIM?

he vowed to find away around it, suddenly in dire need to be able to readily visit nico whenever he pleased. which was the right of siblings, was it not? he planned to take his role as older VERY seriously.

" and where do you reside now, younger brother? "

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be honest, my go-to when I think of Durge is the category of beings that 3.5e cheerily named 'Abominations.' Just one that happens to look more like a regular mortal and maybe was created on purpose (although maybe Bhaal made Durge totally by accident and just rolled with it). Also the fact that Bhaal appears to want them is a shift (gods (and everybody else in existence) want their abominations locked far, far away from everything and everyone).

'Abominations are mistakes - the unwanted, unforeseen offspring of misguided deific concourse. Abortions of spirit, abominations live on, nurtured by their quasi-deific powers and pure, undiluted hate of their forebears and all naturally formed creatures. [...] Abominations come in an overwhelming variety of forms, all terrible. [...] All abominations are born directly (or indirectly) from a god and some lesser creature (or idea [such as being built by the god rather than involving another parent])...' - Epic Level Handbook

They age so slowly it's borderline impossible to die of old age (sure they can die of old age but they'll be around to see the deaths of universes, so it's meaningless form the human perspective), and barely ever need to eat, sleep or breathe.

They heal fast, have innate spell-like abilities, and always have at least one or more abilities tied to their parent's portfolio.

It was specifically the atropals that brought me here:

'Atropal scions are clots of divine flesh given form and animation by bleak-hearted gods of death. When a stillborn godling rises spontaneously as an undead, a great abomination is born. If that abomination is defeated, but any fragment or cast-off bit of flesh remains, an atropal scion may yet arise from those fragments, lessened in power from its divine beginnings, but no less hateful for its stature.' - Libris Mortis: The Book of Undead

Durge is neither undead (alas) nor an evil god-zombie-foetus abomination, but the point that abominations may be born of a death god's discarded flesh remains the closest thing to an explanation of how the fuck their origin story makes sense I can find.

#Shame the in-game doesn't match up#My god if you're going to go extra special born of death Bhaalspawn lean into it! Give me a horror!#/durge#lore stuff#edgelord hours

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

a brief analysis on hades npcs' favorite blood sibling

this is not a popularity contest. this is my attempt at analyzing if certain characters prefer a certain sibling based on the info we have now.

prefers mel:

artemis. she likes zag of course, but this is obvious.

this is sad and ofc horrendously unfair to zag, but as predicted, so far hades does speak to mel with more respect than he did zag for most of hades 1, as evidenced by him already calling her "daughter" not "girl." perhaps hades's relationship with zag has changed significantly post-game, and obviously the circumstances and baggage of zag's upbringing (which hades was responsible for) vs hades meeting mel for the first time as a capable young woman are very different, but. yeah.

this is a guess, but i'm gonna say hermes likes her more as well, although only just. he's eager to get her to olympus and they've just been in contact for longer as he's a friend to the silver sisters. however i do think that there's an argument to be made that zag prioritizes speed over mel, both in character and gameplay, so hermes might relate to that with zag more.

possibly charon. i might have put him in the "no preference" category, because i don't think mel being able to understand him better necessarily means he likes her more, but i do think that he might prefer mel juuuuuuust barely only because he offers her loyalty cards without her needing to beat his ass lmao. there is no shoplifting option for mel yet so if it is added, i might change my mind, but so far i don't think she'd be the type to do it anyway.

possibly aphrodite but if so, it's not by much imo. she definitely likes zag, but says to mel "you look like you can break some hearts even without my aid" which sounds like approval of mel's messy situationships lol. to me her nicknames "little godling" vs "gorgeous" kind of implies the slightest more fondness of mel but again, not by much.

prefers zag:

chaos. outwardly asked "where's your more fun brother :/" and explicitly once told mel to shut up lol. also because i think a being called primordial chaos is understandably more interested in a story of "snarky, rebellious kid runs away from home and shakes up family status quo while blasting his way through the underworld" rather than "perfectionist does what she's told/tries to set the world in order." obviously chaos still supports mel, but definitely finds zag more interesting. chaos had to specifically set up trials for mel to get entertainment out of her lol.

skelly. one of my theories as to what's going on with skelly is that he's cosplaying his living self just for shits and giggles because it's a war, but also like. it's skelly lol so who knows. i think his personality in 1 is more his "natural self" which so far we've only seen come out around zag.

cerberus. :/

no preference:

homer. i know homer describes them differently (zag as a lazy, responsibility-avoiding slob vs mel as a tragic duty-focused, orphan princess), but i think that's not because homer prefers mel, but because he's crafting his diction to the story being told. hades 1 is a story with a twist wherein he reveals a laid-back prince is actually just lonely and misses his mom (imo he describes zag much more sympathetically as time goes on), but hades 2 is a war story and mel has been raised as a soldier all her life, so his tone is just different with mel from the offset. it's not fun to make light of her because the stakes are higher.

demeter: the real answer is persephone, persephone is her favorite lol. imo she seems just glad to have alive grandkids.

poseidon and zeus? haven't seemed to notice a preference so far from either of them. they have a more pressing reason to support mel because war and all, but also artemis mentions they don't really believe she can do it, which makes sense, but it makes me wonder if their support with mel is a bit patronizing, or like "well what have we got to lose." they also don't seem particularly worried about zag missing of course but i think these two have so many nieces and nephews and relatives that any preference they have between mel or zag is miniscule.

theories on returning characters we haven't seen yet:

prefers zag: nyx (just due to her raising him... but a case can be made for mel due to the silver sisters/mel living in shadow/hecate's relationship with nyx), dionysus (party boys), achilles & patroclus (probably), sisyphus & orpheus (power of friendship), thanatos & meg (obvious), asterius (respect for their many battles)

prefers mel: athena (level-headed warrior women), ares (a witch assassin groomed specifically for war? "go ahead and torture my family, but i will still come back to kill you over and over again"? absolutely), eurydice (cooking gal pals), theseus (please god it'd be so funny)

no preference: idk dusa? and hopefully persephone. the kids need a parent who doesn't have a favorite. i do think she will always have a soft spot for zag because he found and brought her home, but also i'm sure persephone will also want to spend a lot of one-on-one time gardening with her daughter.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New Gods

by SalParadiseLost Bruce lives in a careful balance. He has adopted the wrong children. His children are godlings born for the worst of humankind, and they always carry a risk of potentially hurting the humanity that Bruce was born to protect. So far, his children have behaved, but the threat of them being put down looms large. His children are at risk again when they find themselves at the centre of a murder mystery involving the death of a young god. Magic traces found at the murder mean that the murderer could only be Dick, Jason, Tim or Bruce himself. Bruce and his sons race to figure out who the murderer could be before the other gods lose patience and decide that killing Bruce's godlings is the safest path after all. Words: 4353, Chapters: 1/?, Language: English Fandoms: Batman - All Media Types Rating: Mature Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings Categories: Gen Characters: Tim Drake, Dick Grayson, Jason Todd, Bruce Wayne, Diana (Wonder Woman), Clark Kent Relationships: Tim Drake & Dick Grayson, Dick Grayson & Jason Todd, Dick Grayson & Bruce Wayne, Tim Drake & Jason Todd, Tim Drake & Dick Grayson & Jason Todd & Bruce Wayne, Tim Drake & Dick Grayson & Jason Todd, Diana (Wonder Woman) & Clark Kent & Bruce Wayne Additional Tags: Alternate Universe, Alternate Universe - Gods & Goddesses, Good Parent Bruce Wayne, Dick Jason and Tim are siblings, Protective Bruce Wayne, Protective Dick Grayson, Protective Tim Drake, Protective Jason Todd, They are all gods of hyperspecific things, Murder Mystery, Mystery, some body horror, Visceral Depictions of Bodies, Tim likes to cosplay people dying so, Discussions of School Shootings, I realise these tags seem very random via https://ift.tt/GteInsi

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

misc ocs, outside the category of my usuals--

- Cibby is a redraw of a very, very old OC of mine. As a kid I used to imagine all my OCs/fandoms had a ‘hub world’ they could visit and mingle, and she was suppose to be the guardian and protector of it. She is/was a Very Powerful, Cannot Touch godling who likes sweets and parties. Her original-original form was so incredibly themed off Kirby it was blatant (her original name was just ‘kirby’, too), & I tried to pull a Little Bit of that back with all the stars motifs and her eyes

- Rahiam is another old OC who I didn’t really redesign here, so much as just redraw a bunch of old arts (as I did with Gaboro, who is from the same story). She’s a little light-based bunny who glows in the dark like a lightbulb

- four FF OCs, drawn in theatrhythm style (Sorta). Leon, Lilias, Line, Lief. I have a joke going with myself that any FF OC I make must have a L-name, in “tradition”.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

* ── 𝖕𝖗𝖔𝖒𝖕𝖙 𝑵𝑰𝑵𝑬 ❜ ⟨⟨ 𝖣𝖮𝖭'𝖳 𝖡𝖤 𝖠𝖥𝖱𝖠𝖨𝖣 𝖮𝖥 𝖥𝖠𝖨𝖫𝖴𝖱𝖤. 𝖳𝖧𝖠𝖳'𝖲 𝖳𝖧𝖤 𝖶𝖠𝖸 𝖳𝖮 𝖲𝖴𝖢𝖢𝖤𝖤𝖣. ⟩⟩

silas ... was humbled by/during the olympics.

there's no easy or better way to say that. he's a professional athlete at heart, always has been - so while he isn't going to begrudge any others ...any of the wins they brought home, it bothers him to no end that he's been beat. silas is not a quitter. that's in his essence. he'll try & try & try again. as many times as it needs until he wins. but with the olympics, he can't, because it's a one-time deal. at least for the year.

so it drives him mad to know that he was bested, especially in his events ... is a hard pill to swallow & definitely messes with his psyche. it's going to take quite a bit & a lot of all-nighter training sessions to get over that. he wanted to be best in all the categories he participated in, sure, but pankration & wrestling are the categories he had his heart in & not acing them hurt. but at the same time he also realized that he's good at throwing things, so he's definitely thinking of ways to utilize that for fights.

silas learned from this, unfortunately, but he also greatly enjoyed competing with other pantheons, seeing other godlings like him fight, train & perform. he is, still, regardless of win or lose, an athlete & athletes build one of the greatest & most supportive communities, so he will eventually swallow his pride & be happy for .... all the winners.

one day.

for now he'll keep on pouting & pushing himself harder during training.

but one day, he'll accept defeat.

maybe.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Was that part of why he'd held off as long as he had? It wasn't like he feared the rejection. Actually getting an answer had been more of a surprise to the Son of Time than just being ignored would have been. Calvin mostly dismissed it as something more akin to 'this is something that will actively benefit all of us if you know' than. Anything else. "Well, here's hoping everybody gets answers when they really need them." There wasn't much else he could say. People that needed to lean on those answers from above absolutely had his support.

A brief mental note made for Isaac's more competitive side definitely jumping out, while he'd yet to even mildly stoke an ember of it. He'd be just as content placing in one of the categories as he would just... Cheering people on.

"That's my plan at least. Not exactly all that good at persuading people but figure can't hurt to try." He knew some of them would have some pre existing connections to call upon, some of them had encountered fellow godlings on quests, Calvin was... Mostly just gonna hope he was charming enough to make a good impression. "Put my hat in the ring for 100m dash, fencing and long jump but don't hold out much hope for 'em." Athletics and support not exactly something he'd ever been all that trained in. He'd learned to fight and survive and... Well that only really got you so far in something like this.

"I think most of us have a similar story." Similar, but not the same. Isaac had spent enough time as a kid hoping his father would suddenly appear - speaking into the proverbial void. Here the rules made sense; make your offering, say your prayer, maybe they listen, and then maybe they respond. Isaac was infringing upon forty, yet his father still held all the power. Whatever the son of Thanatos wanted from the patron, it was one-sided and one of the burdens of their divinity. "At least you got a response, that's more than some can say." Isaac had also been fortunate, but he'd also prayed before anyone told him that Thanatos might not respond. He thought briefly of the hesitation that Axel had mentioned, then left the thought to the wayside.

"For some of us, the competition is half the fun." Isaac, smiled, the implication that included Isaac felt obvious, though he left it in suspense. Win or lose, the spirit of the contest itself was enough to incense the chip on Isaac's shoulder. He'd considered asking for favor in the games ahead, but in this, Isaac wished to stand on his own. Ender prayed to the wrong God and was cursed when it fell through, Hercules went mad and killed his family, and Bellerophon fell off his pegasus and broke his back. Favor came and favor went just as quickly - they needed to be able to hold their own. "Hopefully we walk away from the games with more allies than enemies."

"Have you decided what contests you're competing in?" Isaac might be able to guess based off of what he'd observed because admittedly, the demigod had been watching. Some of his own contests weren't decided based on any particular skill - in some Isaac didn't think he'd succeed. Chariot racing among them, it was the ideal of riding next to his fellow demigods, wind rushing past them as they charged. That was just exciting.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

(please note that I have no beta reader, and have no intention of fixing any issues/mistakes. this was written between moments of quiet at work, so its not the best but i didnt intend it to be. enjoy :) ))

Fandoms: God of War Ragnarok

Rating: General Audience

Warnings: No Warnings Apply

Categories: M/F

Characters: Atreus Kratosson-Laufeyson, Angrboda, Fenrir

Relationships: Atreus/Angrboda

Additional Tags: these two are dorks, young love, both of these idiots are touch-starved and you can’t tell me otherwise, fluff, Fenrir is just there to be a giant pillow :)

When Atreus had popped back into Ironwood unannounced, Angrboda hadn’t been expecting it to be so he could take her on a journey to show her something in Midgard.

The red-haired teen was unpredictable on the best of days, sure, but this took the cake. He checked in sometimes, showing up in Wildwoods, Freya’s house, or Ironwood interchangeably and with very little warning. Only for a few hours, but still. To have him visit to take her to another realm? That was new.

Fenrir had yipped happily, bouncing back and forth on his paws like a pup. It took a decent amount of time full of pets and playing fetch to wear him down enough to make a tear between realms, most of that time was spent with Atreus being lovingly squashed under the hulking form of his own wolf.

While the realm travel was quick, the boat ride was not. Angrboda skimmed her fingertips over the lake’s surface, soaking in the differences between this water’s coloring compared to Ironwood’s. The light of the sun made the untouched portion of water glimmer iridescently like a geode full of quartz.

Unsurprisingly, the hike up the side of the mountainside was just as gorgeous. The trees were covered with leave again, the thick canopy of green letting speckled beams of light through. Angrboda lifted her palms upward to splay the warmth upon them, and Atreus took small glances from the corner of his eyes to watch the gleam of golden metal looped in her hair. Gold was everywhere around them and it was simply beautiful.

“Hold on, I’ll climb up and help you.” Atreus called behind him, already beginning to scale the short way up the rock face they had reached, fingers digging into the crevices in the surface.

With a grunt, the boy heaved himself over the side. He turned back to his friend, who simply crooked an eyebrow at him. Bending over, he reached his hand out to the other teen. Angrboda took it gratefully, a smile blossoming across her face.

It only took a single tug from the godling and a minor jump from the giantess to clear the wall. Laughter rang through the air as the two rebalanced themselves, hands still laced together.

Atreus was the first to notice, eyes flickering between their connected hands and Angrboda, watching as she reached with her free hand to push a stray braid out of her face.

Her motions froze when she glanced at their hands, the other warm against hers. They released each other quickly, faint pink shades painting their faces equally.

Angrboda was the first to break the awkward silence, letting a small laugh out, Atreus following soon after. Like a spell being broken, the tension faded as quickly as it had formed. The two giants jumped from cropped rocks, throwing branches off the cliff for Fen to chase, and debating who would win the leg race this time around ( ‘You don’t have your magic steed this time!’).

Finally, Atreus planted his foot on the very edge of the cliff’s ledge and pointed out toward the lake.

“This is what I thought you should see,” the boy proclaimed proudly, eyes shining with anticipation and joy, “I found this view on one of my last trips back here.”

“It’s beautiful...,” Angrboda easily admitted, voice laced with awe.

It was indeed beautiful. The lake shimmered like the finest glass, the gentle waves lapping at the shores. The trees filled the landscape with thick layers of varying shades of green. The towers stood tall, strong columns of gray and golds against the bright blue of the water. Tyr’s temple was a shining gold beacon in the center, as intricate and pretty as the lake itself.

Jormungandr stood out the most though, his large body laid just right to appear like a mountain range against the clear sky. His scales caught the sun’s rays perfectly, causing them to shine as iridescently as the lake itself. It was breathtaking and Angrboda could already feel herself reaching into her satchel for her brushes.

With a canvas in hand, Angrboda plopped herself down on the ledge, legs dangling off the edge. She patted the spot next to her, eyes roaming the blank sheet as she plotted the course of her paints.

Atreus stared for a moment longer before dropping down onto his rear as roughly as his friend had, careful to not bump her.

Their thighs were touching, heat radiating where they touched. Atreus could feel his face flush, ear burning as he was sure his entire body had sent all its blood to his head. The rush made him dizzy, but he couldn’t help the smile that curled his lips.

Angrboda was leaning against his shoulder now, eyes squinted and nose scrunched up in concentration as she moved her paintbrush across the page, bright yellow spreading widely. Atreus had a feeling yellow was her favorite color.

He wasn’t sure if he should put his hand around her or simply leave her be. What qualified as appropriate in this situation? Would she stop leaning on him if he touched her back? He didn’t want to make her uncomfortable.

A million thoughts buzzed in his head, making the dizziness worse. Without realizing it, he had set his head atop hers, leaned to the side so his cheek rested against her hair, eyes closed against the bright sun.

The young giantess stilled for a moment, a blush of her own coloring her skin before she returned to her work. One strand of her braids fell foward, partly blocking her view but she didn’t move to adjust it back into place, instead letting it gently hang down. It was fine where it was and so was she.

By the time Angrboda finished, the sun had moved far to the west but hadn’t set yet. There was still plenty of light left, shimmering over the Lake of Nine and warming the two teens in its glow.

Leaning a little further into Atreus’s side, Angrboda ran her finger over the faded material of his sash, eyes and finger tracing the yellow trails along the dulled red. Her eyes struggled to stay open, the warmth and comfort of both the sun and another person beside her a bizarre mix of nostalgic and foreign.

The battle was lost before it had even begun, both teens’ breathing evening out as sleep overcame them, perhaps one more swiftly than the other.

---

Atreus startled awake when he felt a large form settle around him, relaxing at the sight of the spotted fur of Fenrir while laid to curl around him and Angrboda. Said giantess only opened one eye to peek at what had spooked her glorified body pillow, tiredness blurring her vision.

With a contented sigh, the young girl closed her eye again and shifted further into Atreus’s tunic. Embarrassment could be dealt with tomorrow, right now she was too comfortable to care.

The young boy couldn’t quite say the same, he was certain his entire face was as bright red as the fruits in his mother’s garden. The heat returned with a vengeance, his head dizzy and stomach clenching but....it wasn’t bad. There was a giddiness there too, youthful awe and wonder at the causal closeness between them.

The godling leaned his head back against Fen’s shoulder, patting it gently with his hand. The wolf whined softly, wiggling his massive muzzle under his owner’s arm. The boy in turn let out a quiet laugh, half hum and half chuckle.

Scratching up and down Fen’s snout, Atreus could feel himself drifting back to sleep. His eyes felt heavy, and his fingers slowed, though Fenrir didn’t seem to mind as he too was wavering in his wakefulness.

Cautiously, as though to not break the peace between them, Atreus lowered his other arm to wrap around Angrboda, pushing their heads together as they both relaxed and allowed slumber to claim them.

#atreus x angrboda#angrboda#atreus#gowr#god of war ragnarok#my writing#fluff#these kids are soft and so am i#the dizziness thing is from how i feel when people touch me or i touch others#as i too am touch starved#might add onto this with another one shot of the consequences of falling asleep in the sun with no sunscreen ripppp

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Astrology & the Greek Goddesses

Aries

Nike: Goddess of Victory

In Greek mythology, Nike was a goddess who personified victory in any field including art, music, war, and athletics.

Artwork by Serathus on https://www.deviantart.com/serathus/art/Nike-288927384

Taurus

Gaia: Goddess of the Earth

Gaia was the Greek goddess of the Earth, mother of all life. She represented fertility (the ability to create life).

Artwork by Desirée Delgado on https://www.salvabrani.com/pimage/60446819991030506//

Gemini

Aphrodite: Goddess of Love & Beauty

Aphrodite was the Greek goddess of love, beauty, desire and all aspects of sexuality. She was depicted as a beautiful woman often accompanied by the winged godling Eros (Love). Her attributes included a dove, apple, scallop shell and mirror.

Artwork by Guangjian Huang on http://www.hgjart.com

Cancer

Hera: Goddess of Women & Marriage, Queen of the Gods

Hera is the goddess of women, marriage, family and childbirth. Hera was seen as a matronly figure who was the patroness and protector of married women, presiding over weddings as well as blessing marriages. Hera is usually depicted with the animals she considers sacred: cow, lion and peacock. The word Hera is often connected with the Greek word hora, which means season, and is interpreted as “ripe for marriage”.

Artwork by Scebiqu on https://www.deviantart.com/scebiqu/art/SMITE-Hera-770926471 and edit found on https://da-jis-thighs.tumblr.com/post/178842871779/hera-icons-that-brought-me-pain-free-to-use

Leo

Alectrona: Goddess of the Sun

Alectrona (also known as Electryone or Electryo) was the greek goddess of the sun. It is thought that she might have also been the goddess of morning or 'waking from slumber'.

Artwork by Tae Sub Shin on https://legendofthecryptids.fandom.com/wiki/Category:Artist:_Tae_Sub_Shin

Virgo

Persephone: Goddess of Spring, Queen of the Underworld

Persephone was the goddess of spring growth & bounty. Once upon a time when she was playing in a flowery meadow with her Nymph companions, she was seized by Hades, the God of the Underworld, and carried off to the underworld as his bride. Then on, she was also the Queen of the Underworld. Her annual return to the earth in spring was marked by the flowering of the meadows and the sudden growth of the new grain. Her return to the underworld in winter, conversely, saw the dying down of plants and the halting of growth.

Artwork by Elena Kukanova on https://www.deviantart.com/ekukanova/art/Vana-the-Ever-Yong-879525831

Artwork by BohemianWeasel on https://www.deviantart.com/mirachravaia/journal/Talks-with-Tolkien-artists-BohemianWeasel-567104787

Artwork by Mia Araujo on https://americangallery.wordpress.com/category/araujo-mia/

Libra

Themis: Goddess of Divine Justice, Law & Order

Themis was the goddess of divine law and order - the traditional rules of conduct first established by the gods. She was the divine voice (themistes) who first instructed mankind in the primal laws of justice and morality, such as the precepts of piety, the rules of hospitality, good governance & conduct of assembly. In Greek, the word themis referred to divine law, those rules of conduct long established by custom. Unlike the word nomos, the term was not usually used to describe laws of human decree.

Artwork by Kryseis Art on https://www.deviantart.com/kryseis-art/art/Justice-698602554

Scorpio

Hecate: Goddess of Magic & the Occult, the Triple Goddess

Hecate was the chief goddess presiding over magic and spells. She is variously associated with crossroads, entrance-ways, night, light, magic, knowledge of healing herbs and poisonous plants, ghosts, necromancy, and sorcery. She is most often shown holding a pair of torches, a key, snakes, the black she-dog and the polecat.

Artwork by Kim Dreyer on https://www.deviantart.com/ambercrystalelf/art/Hecate-Triple-Goddess-374598950

Sagittarius

Artemis: Goddess of Hunt & the Wilderness

Artemis was the goddess of hunting, the wilderness and wild animals. In ancient art, Artemis was usually depicted as a girl or young maiden with a hunting bow and quiver of arrows.

Artwork by Yujin Jung on https://siznart.artstation.com/projects/LvK5v

Capricorn

Demeter: Goddess of Agriculture, Harvest & Abundance

Demeter is the goddess of the agriculture and harvest, presiding over grains and the fertility of the earth. She presided also over the sacred law and the circle of life. She is the goddess of abundance.

Found on https://mythologyexplained.com/demeter-in-greek-mythology/

Aquarius

Athena: Goddess of Wisdom, the Arts & War Strategy

Athena is the goddess of wisdom and knowledge. As such, she is not only the goddess of war strategy and the protectress who upholds peace for the city of Athens. She is also the goddess of civilisation, the arts, literature and architecture. Her major symbols include owls, olive trees and the Gorgoneion (a magic pendant showing the Gorgon's head, a symbol of protection against evil). In art, she is generally depicted wearing a helmet and holding a spear.

Art by Tsuyoshi Nagano on http://en.tis-home.com/tsuyoshi-nagano/works/8034

Pisces

Amphitrite: Goddess & Queen of the Ocean

Amphitrite was one of the 50 sea nymph (Nereid) sisters. While Amphitrite was dancing and singing with her sisters, she caught the eye of Poseidon, the God of the Ocean, who fell in love with her. Now the attentions of a powerful god proved unwanted though, and Amphitrite fled from the advances of Poseidon. Amphitrite decided to flee to the furthest extremes of the sea, or at least the Mediterranean Sea, and so the Nereid hid herself away near the Atlas Mountains at the furthest point east of the Mediterranean. The disappearance of Amphitrite only caused Poseidon to become more infatuated with the Nereid, and so the new ruler of the seas sent out aquatic creatures to find the hidden Amphitrite. One such tracker of Amphitrite was the sea god Delphin (Delphinus) who came across Amphitrite as he swam between the islands. Delphin didn’t forcibly take Amphitrite back to Poseidon, but through his eloquent words, Delphin convinced the Nereid of the positive elements of marrying Delphin, and so Amphitrite returned to the palace of Poseidon. Poseidon was so thankful to Delphin for bringing his love back to him, that the likeness of the dolphin shaped god was placed amongst the stars. Upon accepting Poseidon's hand in marriage, Amphitrite became the Goddess and Queen of the Ocean.

Artwork by David Guillet on https://www.scififantasyhorror.co.uk/superb-fantasy-art-david-gaillet/

#astrology#zodiac#horoscope#greek mythology#goddesses#queens#aries#taurus#gemini#cancer#leo#virgo#libra#scorpio#sagittarius#capricorn#aquarius#pisces#divine feminine#nike#gaia#aphrodite#hera#alectrona#persephone#themis#hecate#artemis#demeter#athena

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ninshubur, Inanna’s Sukkal: Just a Servant or Something More?

Special thanks to my girlfriend for providing the vintage shoujo parody above, feat. Inanna, Ninshubur and Eblaite artifacts Due to its unique character this post requires a special preface. Most of my “serious” coverage of mythology is meant to be presented as rigorously as possible for a layperson doing this mostly for entertainment, which is who I ultimately am. This post represents a departure from this standard - it’s basically entirely unfounded speculation, personal feelings and wishful thinking. Similar posts often get passed around accompanied by grandiose claims from commenters, so I will stress that I wrote this for personal reasons and only discuss personal feelings. I do not claim this is some sort of suppressed truth, as I am particularly not fond of cases where personal interpretations - which I view as valid if they are acknowledged as just that - are used to claim modern, rigorous research is in fact phony or a nefarious conspiracy. With that out of the way - as stated in the title, I’m going to discuss a case which as many of the regular readers are aware of is close to my heart - that of how Mesopotamian literature depicts the relationship between Inanna and Ninshubur (a deity I like so much that she now has a longer and better sourced wikipedia page than many more major Sumerian deities). I plan to show why I personally think that regardless of the intent of the original authors, there is enough subtext in known sources - presumably not necessarily intentional - to interpret them as a couple. I will also try to highlight Ninshubur’s rarely discussed prominence, both in myths and elsewhere. Parts of the article simply discuss vaguely relevant historical background and primary sources. As usual, I am also providing a bibliography. Therefore, I hope that even if you are not really interested in ultimately pretty silly speculation, you will find something interesting under the cut. Meanwhile, if you are interested in relationships between women more than scholarship, I hope that this post will serve as a fun example why the study of mythology can lead one to find unintended subtext.

The basics - Inanna, Ninshubur and the descent myth

Impression of a cylinder seal from the Old Akkadian period depicting Inanna (Wikimedia Commons) Inanna was one of the major deities worshiped by the Sumerians, the ancient inhabitants of the southern part of modern Iraq. She was also adopted into the beliefs of other cultures of ancient Mesopotamia. In hierarchical listings of deities she is usually placed somewhere right behind the pantheon heads. She was responsible for, among other things, kingship, love, war and assorted celestial matters. She is also one of the most recurring deities in literary compositions written in Sumerian, with a considerable number being available as part of the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Inanna’s love life was regarded as rather complex. Her most recurring lover was the shepherd god Dumuzi, who is a classic specimen of the clade of periodically dying deities, a category which also included the likes of medicine godling Damu, king Gudea’s personal deity Ningishzida and the elusive underworld god Alla. Multiple narratives about the courtship and love of Inanna and Dumuzi were in circulation in antiquity, most of them joyful. However, some also deal with Dumuzi’s untimely death (which,it should be noted, was also a subject of works unrelated to his relationship with Inanna). The degree of Inanna’s involvement varied from composition to composition, from cause to passive onlooker to vengeful avenger. Arguably, however, the most famous is Inanna’s Descent, in which Dumuzi’s death is attributed to his unwillingness to mourn Inanna during *her own* temporary death. A prominent aspect of this myth is also Inanna’s reliance on Ninshubur, a goddess of slightly lesser caliber serving as her sukkal. Sukkal is a term which can refer to a deity’s “ second in “command” - in other words, a sidekick. The word was also used to describe a rank of human court officials, in which context authors variously translated it as “vizier” or “envoy”. Despite the nature of her position, Ninshubur’s status was hardly a minor deity, judging from her popularity in the sphere of personal worship and from a number of theological texts. She was arguably the archetypal example of a sukkal, and her functions - those of a divine messenger, diplomat and mediator - largely stem from this status. Dumuzi’s and Ninshubur’s roles in the story differ greatly. Prior to the reveal that he was not partaking in the customary mourning rites, Dumuzi has minimal presence in the narrative. Ninshubur, by contrast, is an active participant, entrusted with enacting an emergency plan in case of Inanna’s prolonged stay in the underworld, equivalent to death. A long section is dedicated to her grief and to the journey she undertakes to attempt to convince major gods to resurrect Inanna. Ninshubur’s adventure culminates in the creation of two artificial genderless beings who manage to revive Inanna, at the command of the god Enki. Subsequently, Ninshubur reunites with the resurrected Inanna, who praises her for her devotion and protects her from the galla, demonic underworld constables. The term also denoted mundane policemen, or at least people who could be roughly considered their equivalent in ancient Mesopotamia. In the discussed myth, they are meant to deliver a replacement for the resurrected Inanna to the underworld at the orders of its ruler, Ereshkigal. In this myth - but surprisingly not anywhere else - Ereshkigal is regarded as Inanna’s older sister. Much of the popular perception of the story appears to be centered on this relation but it is ultimately Ninshubur whose connection with Inanna is particularly close, as seen in the quote below (all quotes from Inanna’s Descent in the article are sourced from ETCSL): This is my minister of fair words, my escort of trustworthy words. She did not forget my instructions. She did not neglect the orders I gave her. She made a lament for me on the ruin mounds. She beat the drum for me in the sanctuaries. She made the rounds of the gods' houses for me. She lacerated her eyes for me, lacerated her nose for me. She lacerated her ears for me in public. In private, she lacerated her buttocks for me. Like a pauper, she clothed herself in a single garment. All alone she directed her steps to the Ekur, to the house of Enlil, and to Urim, to the house of Nanna, and to Eridug, to the house of Enki. She wept before Enki. She brought me back to life. How could I turn her over to you? Afterwards, Ninshubur, who apparently spent the rest of her Inanna-free time weeping at the entrance to the underworld, accompanies Inanna during visits to various lesser underlings’ houses (well, temples); as it turns out, they too mourned properly, and after brief words of praise are left to their own devices. However, that is not the case when it comes to Dumuzi: They followed her to the great apple tree in the plain of Kulaba. There was Dumuzid clothed in a magnificent garment and seated magnificently on a throne. The demons seized him there by his thighs. (...) They would not let the shepherd play the pipe and flute before her She looked at him, it was the look of death. She spoke to him, it was the speech of anger. She shouted at him, it was the shout of heavy guilt: "How much longer? Take him away." Holy Inanna gave Dumuzid the shepherd into their hands. The rest of the myth is poorly preserved, but seemingly Inanna eventually has a change of heart and the well-known system in which Dumuzi and his sister switch places in the underworld every 6 months is established. The ending doesn’t address why it was Ninshubur, rather than Dumuzi, who received the instructions pertaining to the mourning of Inanna’s death and her subsequent resurrection. It doesn’t also explain why Ninshubur stood by the entrance of the underworld, waiting for Inanna, something not even the other mourners did. The goal of this article is to find out if there are any grounds to assume that there is a romantic component to this issue, at least from a modern point of view. I’ve noticed that there are few, if any, academic publications dealing with related matters, and that generally potential lesbian subtext - intended or not - in myths generally is hardly discussed, therefore I hope it will be an interesting curiosity to you, if nothing else.

Gay relationships in Mesopotamian mythology

Naturally, the first question which needs to be addressed is whether any form of love between people of the same gender occurs in relevant literature in the first place. The answer is a cautiously optimistic “yes.” Of course, almost everyone is aware of the speculation about the nature of the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, the most famous heroes of Mesopotamian literature. Therefore it probably comes as no surprise to any readers that many modern authors seek evidence that at least in some portrayals they were in love. The problem is arguably less whether anyone did interpret them as in love, and more how common it was and which sources show it best. Authors who present this view include the world’s arguably greatest Gilgamesh expert, Andrew R. George, as well as hittitologist Gary Beckman. According to George, the notion that Gilgamesh and Enkidu loved each other is present first and foremost in a version of the poem Death of Gilgamesh, known from Tell as-Sib excavations in Iraq’s Diyala region (ancient Me-Turan). The poem is Sumerian in origin and predates the famous standard Epic of Gilgamesh, which only developed after the Old Babylonian period. The passage in mention is apparently not actually present in many of the known copies. It features the head god, Enlil, informing elderly, sick (the illness seems to be the doing of Namtar, known as both a disease of death and as an envoy of the netherworld) Gilgamesh that in the afterlife he’ll be reunited with Enkidu. Due to the emotional value of this passage I will simply let you read it yourself:

The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts vol 1 by A. R. George, p. 142 The belief that loved ones might be reunited in the afterlife appears in texts from various periods of Mesopotamian history, so it can be safely assumed it was not an uncommon idea, even if the most famous myths present the afterlife as incredibly unpleasant. Additionally, Enkidu is evidently treated as a member of Gilgamesh’s family but not a sibling here. My first thought after reading George’s description of the Me-Turan version of the tale of Gilgamesh and Enkidu was to wonder if it is possible that versions which seemingly stresses the view of them as a couple might reflect the needs of a specific audience. Thanks to George’s own studies, as well as those of other authors, we do know that the stories of Gilgamesh were often adapted to fit the tastes of one audience or another. For example, in Hurrian and Hittite translations locally popular deities, such as Shaushka (known as “Queen of Nineveh” or “Ishtar of Subartu”), Hittite Sun God of Heaven, or personified Sea known in both these cultures factored into the story (both as replacements of familiar characters and as stars of brand new “story arcs”), while the descriptions of distant Uruk are often shortened as they were of comparatively little interest to inhabitants of Syria and Anatolia. Could therefore the Me-Turan version represent an adaptation written by and/or for people who were invested in the view of Gilgamesh and Enkidu as a couple more than the average aficionado of similar poetry in ancient Mesopotamia? That would be my assumption, but you should bear in mind it is nothing more than that I am not an actual authority. I am not aware of any examples of mythical figures other than Gilgamesh and Enkidu engaging in similar endeavors. The other potentially relevant evidence comes from different genres of texts, such as omens, magical formulas and (middle Assyrian) laws. Sadly, there isn’t much evidence for gay relationships and what there is doesn’t necessarily match the sphere of myth, to put it lightly (the aforementioned legal texts, in particular, are not exactly pleasant to read). For what it’s worth, there are sporadic references to love magic meant to guarantee the love of a man for another man, alongside the much more common straight variations (both with men and women as targets of the ritual). I will not address the issue of the galla (not to be confused with the homonymous underworld constables!) and similar priestly classes here as the matter is not settled, and many researchers involved are hardly rigorous (this article in particular is a nightmare but it’s not much better elsewhere). All that can be said about the galla with certainty is that they were lamentation singers. It has been argued that they were possibly regarded as possessing a distinct, unique identity, but what that entailed is hard to tell. It does appear that their mythical counterparts in Inanna’s Descent, the two entities created by Enki, are genderless, at the very least. Galla priests performed songs in a “dialect” of Sumerian, emesal, popularly understood as “women’s speech” - however, it’s not really an accurate translation. While the precise meaning is unclear, something like “high pitched speech” might be more appropriate. Emesal is sometimes regarded as a “sociolect” spoken by a specific group (ie. women) but it’s actually more likely to be first and foremost a “genrelect” reserved for specific liturgical purposes according to recent research. As summed up by Piotr Michalowski in a very brief encyclopedic summary, it appears to be “restricted to direct speech of goddesses and women in certain types of literary texts, in particular lamentations.” Bear in mind even this use is not universal: Dumuzi speaks emesal in some texts, Inanna does not in others. Enheduanna, arguably the most famous woman in Mesopotamian history, did not write in emesal, even when it came to direct speech; meanwhile, there are references to purification specialists - who were not galla - reciting emesal texts. Emesal aside - no primary sources actually discuss the sexuality of the galla to any meaningful degree and it’s not even certain if all galla were assigned male at birth, to put it in modern terms. Therefore, any such assumptions pertaining to them are just speculation, often with a dash of vintage orientalism thrown in for good measure. That’s it for men. How about women? As noted by Frans Wiggermann in his brief and somewhat flawed overview of references to sexuality in Sumerian and Akkadian texts there are no known direct references to women attracted to women and to relevant activity in any primary sources (I think there is a passage in a late hymn to Nanaya which might be an exception, I wrote about it a few months ago). He provides no clear explanation for this, though he notes that most scribes were obviously men aligned with the dominant power structures. This state of affairs largely shapes the character and contents of many sources. I personally think it’s safe to say that the fact the literacy rate among men was much higher than among women is at least partially to blame.

Female literacy, religiosity and relationships between women in myths

Generally speaking, the level of literacy even in cultures with a rich scribal tradition was naturally pretty low in the bronze and iron ages, with the only estimate I found (pretty old, I should note) being 2-5% for “western Asia and Egypt” collectively. These are therefore presumably the figures we can apply to ancient Mesopotamia for example in the Ur III and early Old Babylonian periods, when many of the famous myths developed in their presently known textual forms. While it was not entirely impossible for a woman to become a scribe, or to learn how to write through other means (ex. as part of a noblewoman’s preparation for courtly life), it was much less common for them than for men. For instance, only between 4 and 6 (2 cases are uncertain) scribes or scholars identified by name in colophons of known texts were women. Of course, not every text has a colophon with such information, so it’s not impossible that we in fact know more texts written or copied by women, but whose authorship will never be possible to prove. It’s also worth noting these few examples indicate the presence of women (not many, but still) on most stages of scribal education. Nameless female scribes also at times appear in economic documents. Nevertheless, references to women in other similar professions are somewhat infrequent. The exception to this was female physicians, who were generally expected to be literate. I’ve gathered some more detailed information here. This perhaps is somewhat of a reach, but I personally assume both the lack of references to romantic relations between women and the relatively small number of compositions dealing with bonds between female deities seemingly not based on blood relation (and even the latter are hardly common!) can be attributed to the comparatively small number of female scribes, outlined above. A similar argument has been advanced by Alhena Gadotti, though in reference to mortal women as characters in texts copied in scribal schools: women “were generally not part of the cultural, political, and economic elite that the Old Babylonian scribal schools produced and therefore did not play a particularly prominent part in the corpus.” As remarked by Joan G. Westenholz and Julia M. Asher-Greve, interest in female deities was somewhat higher among women than men - “numerous women chose the temple of a goddess for their votive gifts (...), or preferred the cult of a goddess (...), or have names composed with that of a goddess, or are depicted worshiping a goddess” [on cylinder seals - clarification mine]. It’s of course impossible to deal in absolutes, though - there’s ample evidence for personal devotion to gods like Shamash, Zababa, Dagan or Marduk among women, and to goddesses such as Inanna, Ninisina or Namma among men; kings were almost always men but there is a fair share of areas where the source of kingship was at least in certain time periods held to be a female deity - Ninisina in Isin in the Isin-Larsa period, Ishara in Ebla c. 1700 BCE, Belet Nagar, nomen omen, in Nagar in the Old Babylonian period, Inanna in Uruk at various points in time, etc. Still, I think the point might be valid.

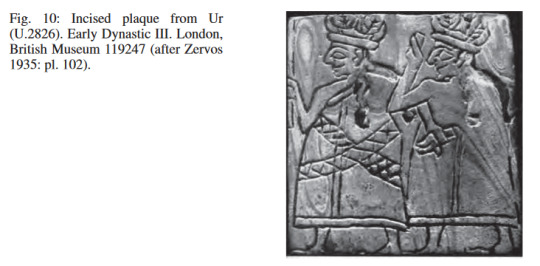

A possible depiction of Geshtinanna and Geshtindudu (Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 387; identified as such on p. 168) Other than Inanna and Ninshubur in Inanna’s Descent and a number of other sources, the only two goddesses I am aware of who appear to share a close bond in myths and aren’t a mother-daughter pair (like Nisaba and Sud/Ninlil or Ninhursag and Ninkasi) are Dumuzi’s sister Geshtinanna and a certain Geshtindudu, who are to my knowledge not attested outside of a small handful of mythical fragments. Julia M. Asher-Greve outright describes these two as “divine girlfriends' ' - I presume not in the romantic sense, though. This is probably just a paraphrase of the ETCSL translation of Dumuzid’s Dream which indeed introduces Geshtindudu as “Her [Geshtinanna’s] girl friend.” Asher-Greve also speaks of it as “one of the few relationships between goddesses based on friendship.” As for other relations based on friendship: I’ve seen references to a myth(?) about Ninisina and Nintinugga - the medicine goddess par excellence and her small time “ersatz” from Nippur - visiting each other (source; it’s on p. 5), but I have not been able to locate it so I can’t tell if it should count as another example. Additionally, while the myth Enlil and Sud deals first and foremost with the relationship between Sud and her mother Ninlil and with her tumultuous romance with Enlil, it seems a poorly preserved section also had Sud interact with Enlil’s sister Aruru (who you may know as the creator of Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh). Given how Enlil and Sud generally seems to have notably more “Ninlil-centric” outlook than its “rival” myth Enlil and Ninlil (which treats Ninlil, a popular and high-ranking deity, oddly poorly), perhaps this should be counted as an example too, though it has been argued the passage might simply indicate that the bridegroom’s sibling played some role in traditional marriage rites. While each of these myths surely could be an interesting topic, I sadly won’t discuss them in detail here (do expect a post on Enlil and Sud at some point, though), as the this article is ultimately about Inanna’s Descent and other sources pertaining to Ninshubur.

Inanna’s Descent once more

While I already provided a brief overview of Inanna’s Descent earlier, the fact that its contents are frequently misinterpreted - often by authors with no knowledge but a large audience - means that some more context is needed. From Jungian nonsense (with all due respect for Olga Tokarczuk, whose works I generally enjoy, her Anna In w grobowcach świata falls into this category) and weird attempts at elevating Ereshkigal well beyond the rank attributed to her in antiquity to a baffling attempt at understanding the myth in Nietzschean terms, Inanna’s Descent is arguably among the most tormented Mesopotamian literary texts, both online and offline. To begin with, it’s important to place it in the context of Sumerian beliefs regarding proper care for the dead. As we can learn from a variety of sources, from myths to prayers to personal letters, the Sumerians viewed mourning and other related matters as incredibly important. Mourning was expressed in many forms, though particularly notable were funerary libations - you can find a reference to this even in the discussed myth: she offers generous libations at his wake, proclaims Inanna about the purported funeral of Ereshkigal’s supposed late husband. Elsewhere, the city of Enegi, associated particularly closely with the cult of the dead, is itself called the “libation pipe of the earth.” Known texts stress that close family, such as spouses, siblings, or children, should be involved in funerary rites. As a matter of fact, from some texts we learn that the status of the dead in the underworld depends entirely on their close ones’ proper adherence to funerary customs. The important role of family in mourning rites creates a problem for the narrative of Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur is not exactly a family member. She is a courtier. While the “public figures” of ancient Mesopotamia were often mourned publicly by a large number of people, here the mourning seems to be private. As far as I understand - Ninshubur is essentially instructed to act as a family member would. Following the usual genealogy of Inanna, there is no real place for Ninshubur on her family tree, as it is generally safe to assume Inanna’s parents are Nanna and Ningal, while she is herself childless. In fact, there is no strong indication Ninshubur was even conceptualized as part of a family tree in the first place. As noted by Frans Wiggermann, texts are largely silent about her parentage. To be fair this is not uncommon for servant deities, divine spouses (even the most prominent ones like Aya and Shala have no established genealogy!) and the like. Curiously, Ninshubur’s mourning is described in very similar terms as that of Ningishzida’s wife Ninazimua in a composition possibly dealing with the former’s death, as Jeremy Black and Judith Pfitzner remarked in their respective articles about the composition Ningishzida and Ninazimua. Of course, this alone is not exactly a strong argument, as parallels can be drawn between these and the figures of mourning sisters and mothers in other texts dealing with deaths of gods. Still, it does appear to be somewhat of an outlier to have a servant, rather than a relative, express grief in such a composition. It’s worth noting that while the only example we have is Inanna’s Descent, we know from preserved Sumerian catalogs of hymns and other similar compositions that there were a considerable number of currently lost texts which dealt with Ninshubur’s grief over something that happened to Inanna. Whether this was a different version of the story or some other, presently unknown, sorrowful event (perhaps banishment only known from an incredibly fragmentary text?) is impossible to tell. A number of researchers, most recently Dina Katz, have proposed that Inanna’s Descent as we know it was in reality the result of combining multiple older narratives, as it only dates back to the Old Babylonian period. I speculate that the aforementioned unknown Ninshubur texts could perhaps have been predecessors to the version of the myth we see today. Such a process of development was not uncommon for Mesopotamian myths. Both Epic of Gilgamesh and Enuma Elish are well known examples. Additionally, this theory explains the dissonance between the usual character of Dumuzi and his relationship with Inanna, known from countless love songs, and that presented in Inanna’s Descent. Katz argues that this presently purely theoretical “original” did not feature Dumuzi - Inanna was saved by Ninshubur’s intervention and Enki’s trick alone, and the addition of a replacement for her seems superficial given the presence of “water of life” in the myth. Inanna’s Descent wasn’t the only myth in which she appears which also served as explanation of Dumuzi’s death, as I already mentioned much earlier - in Inanna and Bilulu, for instance, she tracks down the killer instead (given the extreme level of violence, it would perhaps be fair to call the author a Sumerian Tarantino). At the same time, is somewhat unique in portraying Dumuzi’s death as being the result of his own shortcomings - something which probably indicates the compilers were more invested in Inanna than him, and that perhaps the goal was to merge as many different elements as possible into a coherent tale. As a small digression I should note this is not the most negative portrayal of Dumuzi in known sources: late enigmatic lists of so-called “Seven Conquered Enlils” (in which the name is used just as a title, something like “lord”) place Dumuzi in the company of various well known mythical antagonists, like Tiamat, Asag or Mummu, not to mention the mysterious cosmogonic figure Enmesharra, whose disposition is generally villainous too, as seen for example in the text Enlil and Namzitara. The change in focus from Inanna (or rather than equivalent of her) to Dumuzi only occurs in a very vague adaptation of Inanna’s Descent - the 1st millennium BCE Ishtar’s Descent. While Inanna’s Descent is known from nearly 50 copies, found anywhere from the major cities of Mesopotamia like Ur and Nippur to scribal schools located on the western periphery of the “cuneiform world,” the other myth has only a handful of them, all of exclusively Assyrian provenance. The myths are often conflated online, which leads to horrific misconceptions. Katz argues that the latter myth represents an attempt at state revival of Dumuzi’s (or, to be more accurate, Tammuz’s, as the name was rendered in Akkadian) cult undertaken by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which strikes me as a convincing argument. The change in focus is rather surprising, as the dying god par excellence, as noted by Berndt Alster, “did not belong to the leading deities in any period of Mesopotamian history” (unlike Ninshubur!). A huge difference between Inanna’s Descent and Ishtar’s Descent is the absence of Ninshubur. In the latter myth, Papsukkal, a male messenger deity associated with Anu (and, at an early stage, with the war god Zababa, at home in Kish, modern Tell al-Uhaymir in central Iraq), makes an appearance instead, introduced not as a personal attendant of the heroine, but simply as a servant of the “great gods” collectively. What’s also missing are any references to the instructions regarding mourning and petitioning other gods on her behalf. Evidently, whatever factors resulted in the portrayal of Ninshubur in Inanna’s Descent did not apply to Papsukkal. However, it’s important to stress that the very focus of Inanna’s Descent is different from that of Ishtar’s Descent. Dina Katz noted that while Ishtar’s Descent as a whole seems to be focused on the matter of very broadly understood fertility, “we cannot associate Inanna’s death and revival with procreation in nature nor with fertility in general,” contrary to what one can often read online. After all, fertility is a matter an agricultural deity would be much more concerned with, and Inanna’s Descent is ultimately not focused on Dumuzi and Geshtinanna, the only figures associated with agriculture in the original myth. At the time when the new myth had most likely been composed, Ninshubur was hardly a relevant figure, having seemingly lost her relevance at some point during the Kassite period, in the mid to late second millennium BCE. However, it’s not like the first millennium Ishtar (the myth does not associate her with a specific location like Assur, Nineveh or Arbela) didn’t have a variety of female courtiers who could’ve made an appearance in the myth in her stead. A particularly notable example is the well-attested incorporation of Hurrian Ninatta and Kulitta, a duo of goddesses sharing a rather close relation in myths with Shaushka, the “Ishtar of Subartu” as she was sometimes called, into Assyrian Ishtar cults. Coincidentally, there is no evidence for female scribes in the first millennium BCE, the time of the “translation’s” composition (I put that in quotation marks because while the text is often incorrectly labeled as such, it was actually, as outlined above, pretty much a new myth). Was this a factor in the evident change in sensibilities between Inanna’s Descent and Ishtar’s Descent? Hard to tell, but I personally would not rule it out. To sum up: ultimately, what is important for the subject of the article are two facts about Inanna’s Descent: 1. Ninshubur acts as one would expect a family member 2. Her bond with Inanna is uniquely close The evidence for the two points above does not start or end with Inanna’s Descent alone.

Beyond Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur, sukkals and “wife goddesses”

Probably the strongest argument in favor of viewing Inanna and Ninshubur as uniquely close is the use of an uncommon synonym of the word sukkal, SAL.ḪUB2 (reading uncertain; the 2 should be subscript but tumblr doesn’t allow that, it seems), to refer to the latter. This term is very sparsely attested and only ever used to a handful of deities, exclusively sukkals, in all cases to indicate they are very closely associated with their divine “employers.” In addition to Ninshubur, it occurs for example in relation to Enlil’s sukkal Nuska, envisioned at times as a son of Enlil’s distant ancestors Enul and Ninul and a senior deity in his own right, and to Nabu, Marduk’s sukkal turned son turned pantheon head. I sadly have no access to an article which apparently decisively established its meaning - Vizir, concubine, entonnoir... Comment lire et comprendre le signe SAL.ḪUB2? by Antoine Cavigneaux and Frans Wiggermann - but thanks to the help of a friend I was able to learn a few months ago that, in their words, the authors conclude that it denotes a sukkal “who is dear or intimate.” This interpretation is presumably supported by the fact that in one of the few texts using this term (seemingly the one which is actually largely responsible for scholarly interest in establishing its meaning), Ninshubur is referred to as Inanna’s “beloved SAL.ḪUB2“ and appears among her family members - while her parents, brother, etc. are listed first, Ninshubur’s relation is seemingly more significant than that of in-laws in it, for what it’s worth. Other courtiers, like Nanaya, do not make an appearance. One more possible source is a curiosity from the Hittite capital from Hattusa (located near modern village Boğazkale in central Turkey), specifically a ritual related to the goddess Pinikir. This is (tragically) not the time and place to discuss Pinikir in detail, but it will suffice to say that she was understood as reasonably Inanna- or Ishtar-like. While the text in mention comes from a Hurro-Hittite milieu (Hittites, relatively “young” by the standards of Ancient Near East, viewed Hurrian culture as prestigious), it was written in Akkadian, and it’s primarily concerned with an Elamite goddess, making it uniquely cosmopolitan. Pinikir, whose name is spelled logographically as ISHTAR there, is invited to come alongside her family to receive offerings. She is described as the daughter of Nanna and Ningal and twin sister of Utu/Shamash; the other two figures invoked, Ea/Enki (addressed as “your [ie. Pinikir’s] creator”) and the goddess’ sukkal, instantly bring a variety of myths to mind (Descent, of course, but also Inanna and Enki and the less known Agushaya texts). The name of the sukkal, however, is Ilabrat, spelled syllabically. As far as I am aware, such a pairing is not attested anywhere else, and Ilabrat is generally speaking only Anu’s sukkal, unlike Ninshubur and even Papsukkal, who have multiple roles. While the researcher most involved in the study of this text, Gary Beckman, makes no such connection, I personally think it’s possible that a hypothetical forerunner to this late text featured Ninshubur. Beckman on linguistic grounds concludes Hurrians likely adopted Pinikir, and a variety of rituals connected to her and her usual associate, the enigmatic deity DINGIR.GE6 (“Goddess of the Night”; reading of the name remains unknown; once again, the numer should be subscript, once again), from a Mesopotamian intermediary and not directly from Elam. He proposes that the transfer happened during the period of well-attested intense Sumero-Hurrian contacts in the late third or early second millennium BCE (the text in mention, meanwhile, is no older than the 14th century BCE, I believe). This, coincidentally, was also a time of immense interest in Ninshubur, including theological texts presenting her as one of the “great gods,” side by side with Enlil, Ninlil, Inanna, Ninurta and the like. Perhaps much later on a Hittite scribe, not necessarily fully aware of Ninshubur’s existence (she was, after all, not really a deity of any relevance anymore in the late Bronze Age), worked with older Hurrian material which originally had Ninshubur in this role, but assumed the name is merely a logographic spelling of Ilabrat’s, a phenomenon attested in many locations in the Old Babylonian period? This is only my own, not necessarily valid, speculation, though. Another curiosity is a text in which Inanna calls Ninshubur “mother” - this, however, is not a statement of actual kinship, but rather of respect. Senior gods of the pantheon are often called “father” or “mother” by other deities regardless of actual parentage. Such statements aren’t even necessarily reflections of alternate genealogies or anything of that sort. A good example can be found even just in Inanna’s Descent: Ninshubur addresses Enlil, Nanna and Enki this way, even though none of them are attested as her actual father (and only Nanna was regarded as Inanna’s father between these 3). Presumably Ninshubur’s recurring participation in Inanna’s adventures, and her capability to appease her or to “soothe her heart” was worthy of such reverence.

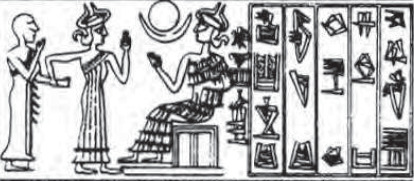

Impression of a cylinder seal depicting a mediating goddess, possibly Ninshubur as indicated by accompanying inscription (Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 406; identified as such on p. 207)

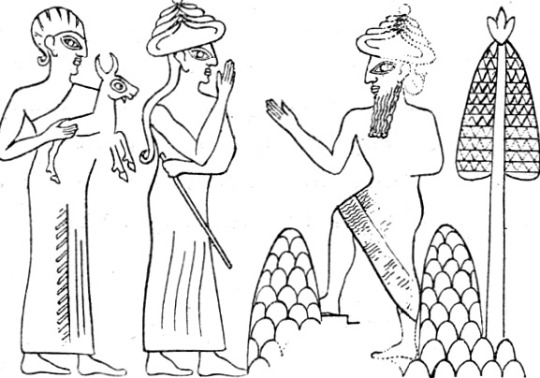

Impression of a cylinder seal possibly depicting Ninshubur (middle) interceding between governor of Lagash, Lugal-ushumgal, and the Akkadian king Shar-Kali-Sharri (wikimedia commons; goddess identified as Ninshubur in Goddesses in Context by J. M. Asher-Greve and W. G. Westenholz, p. 180) The closeness between Inanna and Ninshubur wasn’t limited to texts of mythical nature, and had a very real religious dimension too. Ninshubur was a common object of popular devotion, appearing in personal names, in seal inscriptions, and in other similar sources because she was believed to be capable of mediating with Inanna (and with other deities as well, on the account of being a divine messenger and diplomat). While a sukkal could act as a mediator in the cult of their master, most sukkals are deities with no personality, no individual role in myths and limited, if any popularity: for instance, Ishkur’s sukkal is simply the deified lightning, Nimgir. The difference between Ninshubur and Inanna and that which existed between most sukkals and their masters has been described by Frans Wiggermann as that between “command and execution” and “cause and effect.” To my knowledge very few other sukkals maintained the degree of popularity Ninshubur enjoyed, a notable exception being Nuska. Both of them were listed among the “great gods” every now and then: for example, in a text from the reign of the Third Dynasty of Ur (as I already noted, seemingly a period of prosperity for Ninshubur) both appear side by side with Enlil, Ninlil, Nanna, Inanna, Ninurta, Nergal and Utu - the creme de la creme of the pantheon. Ninshubur is also the only sukkal whose role I’ve seen compared to that of the “wife goddesses” (this is not a genuine scholarly term, I use it for simplicity’s sake). Julia M. Asher-Greve and Joan G. Westenholz specifically draw parallels between her role in Inanna’s cult with that played by Aya, the type specimen of the “wife goddesses” (her to-go epithet is quite literally “the bride,” kallatum) in the cult of Inanna’s solar twin. Of course, this does not indicate that she was ever seen as Inanna’s spouse - but it does at the very least show that it wouldn’t be entirely impossible to claim she was close to that status. While there is no known evidence for Ninshubur status actually moving between that of wife and sukkal when it comes to Inanna, it should be noted that she, as a matter of fact, does move between these two roles in one very specific case. In the area of Lagash and Girsu (modern Al-Hiba and Telloh in Iraq), especially in the third millennium BCE, Ninshubur was associated with Nergal (well, Meslamtaea, as he was typically called in the south early on in Mesopotamian history). As remarked by Wilfred G. Lambert, Ninshubur in this context appears to show up both as sukkal and, unexpectedly, as Nergal’s wife (Nergal’s love life seems to be a rather complex matter). This is rather unique as Ninshubur was generally viewed as unmarried. I don’t think Nergal is exactly similar to Inanna - though both deities share a warlike character - but this association, especially coupled with the modern observations regarding Ninshubur and Aya - does appear to support the idea that you could see Ninshubur likewise moving between status of sukkal and wife when it comes to Inanna. Especially taking into account that, as far as I am aware, it is only Inanna in relation to whom she gets to be a SAL.ḪUB2.

Ninshubur as the lesbian Enkidu?

One final point I’d like to make is that it is possible to make a number of comparisions between Ninshubur’s status to that of the only unambiguously attested gay love interest in Mesopotamian mythology, Enkidu.

A little discussed (outside scholarly circles, that is) aspect of the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu which I’ve already mentioned early in the article is the fact that in the oldest sources do not yet present the latter as the “wild man” created to serve as a foil to Gilgamesh by the gods. Instead, he is the king’s courtier or servant, though a very close one - a status not too dissimilar from Ninshubur’s connection to Inanna in mythical context.

Obviously, the development from servant to cherished companion to lover was gradual, and presumably how the relationship was perceived varied too. Still, it’s worth stressing that while integral to Enkidu as a character in our modern perception, his origin story was actually a novelty compared to his position as Gilgamesh’s beloved, which predates the composition of a singular Epic of Gilgamesh. According to Andrew R. George, it’s possible that his newer “backstory” was meant to stress that to develop as a character Gilgamesh had to interact with a challenger completely from the outside of own sphere.

As a linguistic curiosity it’s worth mentioning that in the old standalone poems Enkidu’s position has been described in a few cases (for example in Gilgamesh and Akka or in Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld) with the poetic term shubur-a-ni, which shares its etymology with Ninshubur’s name. “Shubur” is a term referring to the land also known as Subartu - the areas north of Mesopotamia, inhabited chiefly by Hurrians, or “Subarians,” as Mespotamians called them. However, it also acquired the meaning of “servant.”

You may therefore ask if Ninshubur was the “Lady of Subartu” in origin, perhaps a “Subarian” equivalent of the god Martu/Amurru who embodied traits associated with “Westerners” (that is, Amorites from Syria) or was she always just “Lady of Servants” as Frans Wiggermann interprets her name? That’s hard to tell. Nothing prevents her from being both at once, as acknowledged even by the aforementioned author, especially taking into account that Hurrians were present in Mesopotamia on all levels of society in the 3rd millennium BCE already. Speculating about her origin, fascinating as it is, ultimately is not the concern here.

Another prominent similarity between Enkidu and Ninshubur is that based on a variety of texts the latter fulfilled an important, rather specific role in Inanna’s life, serving as a source of good advice, a characteristic also well attested for Enkidu. In Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld it is the loss of this advice that Gilgamesh laments after it turns out his friend cannot come back to life (a passage which George interprets as one of the early examples of the tradition according to which the two of them were in love). It should be noted that in Ninshubur’s case whether her advice was followed or not is a complicated matter - as we learn from one composition, one of Inanna’s abilities is knowing when to disregard both bad and good advice.

Finally, there is a less direct similarity. It is undeniable that Inanna and Gilgamesh both have heterosexual relationships with other characters, but Enkidu actually doesn’t in sources predating the development of his backstory, and I’ve already outlined Ninshubur’s marital status before. However, Inanna’s and Gilgamesh’s heterosexual relationships are not necessarily emphasized in compositions dealing with their adventures. It is instead their relationships with their respective “sidekicks” that commonly come to the forefront. In Gilgamesh’s and Enkidu’s case, this requires no examples, as various episodes from the Epic are well known. Similarly, in addition to her role in Inanna’s Descent, Ninshubur also appears in the myth Inanna and Enki, where she likewise defends the eponymous heroine from any harm which may befall her - in this case at the hands of Enki’s guards, rather than underworld demons. Ninshubur also praises Inanna after the daring scheme appears to work, leading to the transfer of me (divine powers) to Uruk.

Finally, there is the myth known as Agushaya or, in older literature, Ea and Saltu. While the relations between specific deities in it generally speaking reflects the Sumerian texts which formed the base of the scribal curriculum in the Old Babylonian period, it is presently only known from Akkadian versions. What makes it somewhat of a curiosity is the presence of Ninshubur, otherwise almost exclusively present in literary texts written in Sumerian - perhaps a lost Sumerian original awaits us somewhere out there. While the text uses the name Ishtar to refer to the protagonist, her relation with Ninshubur mirrors Inanna’s in the two texts above.

Saltu (“Strife”), mentioned in the title, is essentially a hostile copy of the heroine, formed by Ea out of dirt from underneath his fingers (note the similarity to Enki’s preferred mode of creation in Inanna’s Descent). Ninshubur apparently provides her mistress with information about this new adversary, whose very appearance fills her with fear. It has been argued by Benjamin R. Foster that a set of odd scribal errors which recur in the passage is meant to be a unique way to render agitated stuttering. Sadly, the middle of the text is not preserved, making it impossible to tell if Ninshubur played any other role in it beyond that.

Closing remarks

The examples above do not show that anyone actually viewed Inanna and Ninshubur as a couple, and it is not my goal to prove decisively that anyone did at the time of the discussed texts’ composition. While obviously there definitely were women attracted to other women in every time and place (how was it expressed and whether modern labels could be easily applied to them is a different matter), it is ultimately not really possible to determine whether they left behind any indirect traces in Mesopotamian textual sources, and how to locate them. The only point which I believe I’ve been able to prove above is that Ninshubur’s relationship with Inanna is uniquely close. As such, both this connection and Ninshubur’s character and broader role in Mesopotamian religion deserve more scholarly attention (can you believe there is no monograph on the concept of sukkal yet?) and more presence in the public perception of Mesopotamian mythology, and more specifically Inanna’s Descent I do personally think there are grounds to debate whether there is subtext in the discussed myths. Even if it was not intended by their authors nearly 4000 years ago, it is hard to deny that from a modern perspective the implications are certainly there. If nothing else, discussing this topic could possibly make the study of relationships between women in ancient texts - not necessarily romantic ones, mind you - more prominent than it is now, both among academics and laypeople. Additionally I think the discussed topic deserves exploration in fiction. As I’ve pointed out above, using the example of Gilgamesh and the reinterpretation of stories about him, certain aspects of myths could be emphasized or de-emphasized to match the expectations of new audiences, without the core of the story being lost. I think this still holds true. Ultimately what I want to say is not “Ninshubur is clearly gay in Inanna’s Descent,” it’s “wouldn’t it be interesting to consider if she was, and whether the ancient sources make it viable?” And that is the question I would like to leave you, the reader, with.

Bibliography

J. M. Asher-Greve, J. G. Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources