#c: ewald

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Please Murder Me (1956)

My rating: 6/10

There's a certain cognitive dissonance to watching Angela Lansbury play a femme fatale type, but she does it quite well, and this is rather an entertaining yarn.

#Please Murder Me#Peter Godfrey#Al C. Ward#Donald Hyde#Ewald André Dupont#Angela Lansbury#Raymond Burr#Dick Foran#Youtube

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

An extensive list of the sources I have found on Internet Archive

Last updated 6/8/25

It would be quite selfish of me to keep these to myself, wouldn't it? This list will be updated frequently, in accordance to what I have found. These were found while doing my own research for various topics, and taken from the bibliographies of many books. Some of these I will have cited in posts of mine, many others will not appear anywhere in my work. Mostly primary sources, but quite a few books make their appearance.

Sorted alphabetically by surname of author

*Some sources, for the sake of readability, have their title somewhat shortened and/or authors removed. In this case, the sourced author will be chosen according to reverse alphabetization, as this is how they are listed on the Archive

A

Alden, John Richard. General Gage in America: Being Principally a History of his Role in the American Revolution

Anburey, Thomas. With Burgoyne to Quebec; An Account of the Life at Quebec and of the Famous Battle at Saratoga

Atwood, Rodney. The Hessians: Mercenaries From Hessen-Kassel in the American Revolution

B

Balderston, Marion and Syrett, David. The Lost War: Letters From British Officers During the American Revolution

Bass, Robert D. The Green Dragoon

Burr, Aaron. Memoirs of

C

Clinton, George. Public Papers of Volume 1 Volume 2 Volume 3 Volume 4 Volume 5 Volume 6 Volume 7 Volume 8 Volume 9 Volume 10

Clinton, Henry. Observations on Some Parts of the Answer of Earl Cornwallis to Sir Henry Clinton's Narrative Clinton, Henry. The American Rebellion; Sir Henry Clinton's Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782

Commanger, Henry Steele. Spirit of '76: The Story of The American Revolution as Told by Participants

E

Ewald, Johann von. Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal

G

Grant, Alfred. Our American Brethren: A History of Letters in the British Press During the American Revolution, 1775-1781

H

Hamilton, Alexander. Papers of Volume 5 Volume 8 Volume 9 Volume 10 Volume 12 Volume 13 Volume 15 Volume 16 Volume 18 Volume 19 Volume 22

K

Kapp, Friedrich. The Life of Frederick William von Steuben

Kemble, Stephen. Journal of

L

Laurens, Henry. Papers of Volume 1 Volume 2 Volume 3 Volume 4 Volume 7 Volume 8 Volume 11 Volume 12 Volume 13

Lefkowitz, Arthur S. George Washington's Indispensable Men

M

Massey, Gregory D. John Laurens and The American Revolution

Moultrie, William. Memoirs of

Murdoch, David H. Rebellion in America: A Contemporary British Viewpoint, 1765-1783

P

Parton, James. The Life and Times of Aaron Burr

R

Ramsay, David. The History of The Revolution of South Carolina

Robson, Eric. Letters From America, 1773 to 1780, Being the Letters of a Scots Officer, Sir James Murray, to his Home During the War of American Independence

S

Steiner, Bernard Christian. The Life and Correspondence of James McHenry

Stevens, Benjamin Franklin. The Campaign of Virginia, 1781: An Exact Reprint of Six rare Pamphlets on the Clinton-Cornwallis Controversy

T

Tarleton, Banastre. A History of The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in The Southern Provinces of North America

V

Van Doren, Carl. Secret History of the American Revolution: An Account of the Conspiracies of Benedict Arnold and Numerous Others

W

Ward, Christopher. The War of The Revolution

Washington, George. Papers of Agricultural papers

#writings#amrev#american revolution#alexander hamilton#john laurens#henry laurens#george washington#william moultrie#david ramsay#george clinton#baron von steuben#how many volumes does alexander have? dont worry about it#aaron burr#resources#banastre tarleton#james mchenry#thomas gage#john burgoyne#henry clinton#sir henry clinton#charles cornwallis#benedict arnold#hessian#hessians

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

supernatural animatic - intersection by jake ewald

plz watch my animatic !!! i started it like last summer and never finished it but decided to upload it anyways bc nothing is perfect in the name of art.

anyways the s2 finale is one of my favs in the whole show (obviously) and the lyrics of this song fit very well with the plot !! crossroads = intersection like come on !

but fr like a song about losing someone who you love so dearly they are a part of you and being lost without them is peak winchester brothers. the line “when all i know is you and all you are is home” in particular perfectly describes the relationship between sam and dean similar to chucks speech in s5ep22 where he says “they never really had a roof and four walls, but they were never homeless”.

“this old hungry bloodhound” is another line that fits almost like a puzzle piece with the plot of supernatural, referencing the fact that in a year, dean is going to be hunted by hell hounds to clear his debt.

i think also “the words don’t sound the same” can be interpreted as deans fear following sam’s revival that what he brought back wasn’t his brother.

sorry to ramble i just really love supernatural and also jake ewald (hello mobo and sbd fans !). i tried uploading this onto tiktok but it got copyrighted almost immediately :c

PLZ SHARE UR THOUGHTS I LOVE HEARING PPLS OPINIONS !!!♡♡

#never getting over sam’s first death#supernatural#spn#sam winchester#dean winchester#sam and dean#the winchester brothers#the brothers ever#supernatural fanart#spn fanart#animatic#animation#spn s2#sam winchester fanart#dean winchester fanart

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Alexander Hamilton: A Timeline

As Alexander Hamilton’s time serving as Captain of the New York Provincial Company of Artillery is about to become my main focus within The American Icarus: Volume I, I wanted to put a timeline together to share what I believe to be a super fascinating period in Hamilton's life that’s often overlooked. Both for anyone who may be interested and for my own benefit. If available to me, I've chosen to hyperlink primary materials directly for ease. My main repositories of info for this timeline were Michael E. Newton's Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton and The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series on Founders Online, and the Library of Congress, Hathitrust, and the Internet Archive. This was a lot of fun to put together and I can not wait to include fictionalizations of all this chaos in TAI (literally, 20-something chapters are dedicated to this) hehehe....

Because context is king, here is a rundown of the important events that led to Alexander Hamilton receiving his appointment as captain:

Preceding Appointment - 1775:

February 23rd: The Farmer Refuted, &c. is first published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. The publication was preceded by two announcements, and is a follow up to a string of pamphlet debate between Hamilton and Samuel Seabury that had started in the fall of 1774. The Farmer Refuted would have wide-reaching effects.

April 19th: Battles of Lexington and Concord — The first shots of the American War for Independence are fired in Lexington, Massachusetts, and soon followed by fighting in Concord, Massachusetts.

April 23rd: News of Lexington and Concord first reaches New York. [x] According to his friend Nicholas Fish in a later letter, "immediately after the battle of Lexington," Hamilton "attached himself to one of the uniform Companies of Militia then forming for the defense of the Country by the patriotic young men of this city." It is most likely that Hamilton enlisted in late April or May of 1775, and a later record of June shows that Hamilton had joined the Corsicans (later named the Hearts of Oak), alongside Nicholas Fish and Robert Troup (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 127; for Fish's letter, Newton cites a letter from Fish to Timothy Pickering, dated December 26, 1823 within the Timothy Pickering Papers of the Massachusetts Historical Society).

June 14th: Within weeks of his enlistment, Hamilton's name appears within a list of men from the regiments throughout New York that were recommended to be promoted as officers if a Provencal Company should be raised (pp. 194-5, Historical Magazine, Vol 7).

June 15th: Congress, seated in Philadelphia, establishes the Continental Army. George Washington is unanimously nominated and accepts the post of Commander-in-Chief. [x]

Also on June 15th: Alexander Hamilton’s Remarks On the Quebec Bill: Part One is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 22nd: The Quebec Bill: Part Two is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 25th: On their way to Boston, General Washington and his generals make a short stop in New York City. The Provincial Congress orders Colonel John Lasher to "send one company of the militia to Powle's Hook to meet the Generals" and that Lasher "have another company at this side (of) the ferry for the same purpose; that he have the residue of his battalion ready to receive" Washington and his men. There is no confirmation that Alexander Hamilton was present at this welcoming parade, however it is likely, due to the fact that the Corsicans were apart of John Lasher's battalion. [x]

Also on June 25th: According to a diary entry by one Ewald Shewkirk, a dinner reception was held in Washington's honor. It is unknown if Hamilton was present at this dinner, however there is no evidence to suggest he could not have been (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 129; Newton cites Johnston, Henry P. The Campaigns of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn, Vol. 2, pg. 103).

August 23-24th: According to his friend Hercules Mulligan decades later in his “Narrative” (being a biographical sketch, reprinted in the William & Mary Quarterly alongside a “Narrative” and letters from Robert Troup), Hamilton and himself took part in a raid upon the city's Battery with a group composed of the Corsicans and some others. They managed to haul off a good number of the cannons down in the city Battery. However, the Asia, a ship in the harbor, soon sent a barge and later came in range of the raiding party itself, firing upon them. According to Mulligan, “Hamilton at the first firing [when the barge appeared with a small gun-crew] was away with the Cannon.” Mulligan had been pulling this cannon, when Hamilton approached and asked Mulligan to take his musket for him, taking the cannon in exchange. Mulligan, out of fear left Hamilton’s musket at the Battery after retreating. Upon Hamilton’s return they crossed paths again and Hamilton asked for his musket. Being told where it had been left in the fray, “he went for it, notwithstanding the firing continued, with as much unconcern as if the vessel had not been there.”

September 14th: The Hearts of Oak first appear in the city records. [x] Within the list of officers, Fredrick Jay (John Jay’s younger brother), is listed as the 1st Lieutenant, and also appears in a record of August 9th as the 2nd Lieutenant of the Corsicans. This, alongside John C. Hamilton’s claims regarding Hamilton’s early service, has left historians to conclude that either the Corsicans reorganized into the Hearts of Oak (this more likely), or members of the Corsicans later joined the Hearts of Oak.

December 4th: In a letter to Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, John Jay writes “Be so kind as to give the enclosed to young Hamilton.” This enclosure was presumably a reply to Hamilton’s letter of November 26th (in which he raised concern for an attack upon James Rivington’s printing shop), however Jay’s reply has not been found.

December 8th: Again in a letter to McDougall, Jay mentions Hamilton: “I hope Mr. Hamilton continues busy, I have not recd. Holts paper these 3 months & therefore cannot Judge of the Progress he makes.” What this progress is, or anything written by Hamilton in John Holt’s N. Y. Journal during this period has not been definitively confirmed, leaving historians to argue over possible pieces written by Hamilton.

December 31st: Hamilton replies to Jay’s letter that McDougall likely gave him around the 14th [x]. Comparing the letters Hamilton sent in November and December I will likely save for a different post, but their differences are interesting; more so with Jay’s reply having not been found.

These mentionings of Hamilton between Jay and McDougall would become important in the next two months when, in January of 1776, the New York Provincial Congress authorized the creation of a provincial company of artillery. In the coming weeks, Hamilton would see a lot of things changing around him.

Hamilton Takes Command - 1776:

February 23rd: During a meeting of the Provincial Congress, Alexander McDougall recommends Hamilton for captain of this new artillery company, James Moore as Captain-Lieutenant (i.e: second-in-command), and Martin Johnston for 1st Lieutenant. [x]

February-March: According to Hercules Mulligan, again in his “Narrative”, "a Commission as a Capt. of Artillery was promised to" Alexander Hamilton "on the Condition that he should raise thirty men. I went with him that very afternoon and we engaged 25 men." While it is accurate that Hamilton was responsible for raising his company, as acknowledged by the New York Provincial Congress [later renamed] on August 9th 1776, Mulligan's account here is messy. Mulligan misdates this promise, and it may not have been realistic that they convinced twenty-five men to join the company in one afternoon. Nevertheless, Mulligan could have reasonably helped Hamilton recruit men between the time he was nominated for captancy and received his commission.

March 5th: Alexander Hamilton opens an account with Alsop Hunt and James Hunt to supply his company with "Buckskin breeches." The account would run through October 11th of 1776, and the final receipt would not be received until 1785, as can be seen in Hamilton's 1782-1791 cash book.

March 10th: Anticipating his appointment, Hamilton purchases fabrics and other materials for the making of uniforms from a Thomas Garider and Lieutenant James Moore. The materials included “blue Strouds [wool broadcloth]”, “long Ells for lining,” “blue Shalloon,” and thread and buttons. [x]

Hamilton later recorded in March of 1784 within his 1782-1791 cash book that he had “paid Mr. Thompson Taylor [sic: tailor] by Mr Chaloner on my [account] for making Cloaths for the said company.” This payment is listed as “34.13.9” The next entry in the cash book notes that Hamilton paid “6. 8.7” for the “ballance of Alsop Hunt and James Hunts account for leather Breeches supplied the company ⅌ Rects [per receipts].” [x]

Following is a depiction of Hamilton’s company uniform!

First up is an illustration of an officer (not Hamilton himself) as seen in An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Uniforms of The American War For Independence, 1775-1783 Smith, Digby; Kiley, Kevin F. pg. 121. By the list of supplies purchased above, this would seem to be the most accurate depiction of the general uniform.

Here is another done in 1923 of Alexander Hamilton in his company's uniform:

March 14th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that "Alexander Hamilton be, and he is hereby, appointed captain of the Provincial company of artillery of this Colony.” Alongside Hamilton, James Gilleland (alternatively spelt Gilliland) is appointed to be his 2nd Lieutenant. “As soon as his company was raised, he proceeded with indefatigable pains, to perfect it in every branch of discipline and duty,” Robert Troup recalled in a later letter to John Mason in 1820 (reprinted alongside Mulligan’s recollections in the William & Mary Quarterly), “and it was not long before it was esteemed the most beautiful model of discipline in the whole army.”

March 24th: Within a pay roll from "first March to first April, 1776," Hamilton records that Lewis Ryan, a matross (who assisted the gunners in loading, firing, and spounging the cannons), was dismissed from the company "For being subject to Fits." Also on this pay roll, it is seen that John Bane is listed as Hamilton's 3rd Lieutenant, and James Henry, Thomas Thompson, and Samuel Smith as sergeants.

March 26th: William I. Gilbert, also a matross, is dismissed from the company, "for misbehavior." [x]

March-April: At some point between March and April of 1776, Alexander Hamilton drops out of King's College to put full focus towards his new duties as an artillery captain. King's College would shut down in April as the war came to New York City, and the building would be occupied by American (and later British) forces. Hamilton would never go back to complete his college degree.

April 2nd: The Provincial Congress having decided that the company who were assigned to guard the colony's records had "been found a very expensive Colony charge" orders that Hamilton "be directed to place and keep a proper guard of his company at the Records, until further order..." (Also see the PAH) According to historian Willard Sterne Randall in an article for the Smithsonian Magazine, the records were to be "shipped by wagon from New York’s City Hall to the abandoned Greenwich Village estate of Loyalist William Bayard." [x]

Not-so-fun fact: it is likely that this is the same Bayard estate that Alexander Hamilton would spend his dying hours inside after his duel with Aaron Burr 28 years later.

April 4th: Hamilton writes a letter to Colonel Alexander McDougall acknowledging the payment of "one hundred and seventy two pounds, three shillings and five pence half penny, for the pay of the Commissioned, Non commissioned officers and privates of [his] company to the first instant, for which [he has] given three other receipts." This letter is also printed at the bottom of Hamilton’s pay roll for March and April of 1776.

April 10th: In a letter of the previous day [April 9th] from General Israel Putnam addressed to the Chairmen of the New York Committee of Safety, which was read aloud during the meeting of the New York Provincial Congress, Putnam informs the Congress that he desires another company to keep guard of the colony records, stating that "Capt. H. G. Livingston's company of fusileers will relieve the company of artillery to-morrow morning [April 10th, this date], ten o'clock." Thusly, Hamilton was relieved of this duty.

April 20th: A table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress titled "A Return of the Company of Artillery commanded by Alexander Hamilton April 20th, 1776." The Library of Congress itself lists this manuscript as an "Artillery Company Report." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table and describe the return as "in the form of a table showing the number of each rank present and fit for duty, sick, on furlough, on command duty, or taken as prisoner." [x]

The table, as seen above, shows that by this time, Hamilton’s company consisted of 69 men. Reading down the table of returns, it is seen that three matrosses are marked as “Sick [and] Present” and one matross is noted to be “Sick [and] absent,” and two bombarders and one gunner are marked as being “On Command [duty].” Most interestingly, in the row marked “Prisoners,” there are three sergeants, one corporal, and one matross listed.

Also on April 20th: Alexander Hamilton appears in General George Washington's General Orders of this date for the first time. Washington wrote that sergeants James Henry and Samuel Smith, Corporal John McKenny, and Richard Taylor (who was a matross) were "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. stark was President for “Mutiny"...." The Court found both Henry and McKenny guilty, and sentenced both men to be lowered in rank, with Henry losing a month's pay, and McKenny being imprisoned for two weeks. As for Smith and Taylor, they were simply sentenced for disobedience, but were to be "reprimanded by the Captain, at the head of the company." Washington approved of the Court's decision, but further ordered that James Henry and John McKenny "be stripped and discharged [from] the Company, and [that] the sentence of the Court martial, upon serjt Smith, and Richd Taylor, to be executed to morrow morning at Guard mounting." As these numbers nearly line up with the return table shown above, it is clear that the table was written in reference to these events. What actions these men took in committing their "Mutiny" are unclear.

May 8th: In Washington's General Orders of this date, another of Hamilton's men, John Reling, is written to have been court martialed "for “Desertion,” [and] is found guilty of breaking from his confinement, and sentenced to be confin’d for six-days, upon bread and water." Washington approved of the Court's decision.

May 10th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington recorded that "Joseph Child of the New-York Train of Artillery" was "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. Huntington was President for “defrauding Christopher Stetson of a dollar, also for drinking Damnation to all Whigs, and Sons of Liberty, and for profane cursing and swearing”...." The Court found Child guilty of these charges, and "do sentence him to be drum’d out of the army." Although Hamilton was not explicitly mentioned, his company was commonly referred to as the "New York Train of Artillery" and Joseph Child is shown to have enlisted in Hamilton's company on March 28th. [x]

May 11th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington orders that "The Regiment and Company of Artillery, to be quarter’d in the Barracks of the upper and lower Batteries, and in the Barracks near the Laboratory" which would of course include Alexander Hamilton's company. and that "As soon as the Guns are placed in the Batteries to which they are appointed, the Colonel of Artillery, will detach the proper number of officers and men, to manage them...." Where exactly Hamilton and his men were staying prior to this is unclear.

May 15th: Hamilton appears by name once more in General George Washington’s General Orders of this date. Hamilton’s artillery company is ordered “to be mustered [for a parade/demonstration] at Ten o’Clock, next Sunday morning, upon the Common, near the Laboratory.”

May 16th: In General Washington's General Orders of this date, it is written that "Uriah Chamberlain of Capt. Hamilton’s Company of Artillery," was recently court martialed, "whereof Colonel Huntington was president for “Desertion”—The Court find the prisoner guilty of the charge, and do sentence him to receive Thirty nine Lashes, on the bare back, for said offence." Washington approved of this sentence, and orders "it to be put in execution, on Saturday morning next, at guard mounting."

May 18th: Presumably, Hamilton carried out the orders given by Washington in his General Orders of May 16th, and on the morning of this date oversaw the lashing of Uriah Chamberlain at "the guard mounting."

May 19th: At 10 a.m., Hamilton and his men gathered at the Common (a large green space within the city which is now City Hall Park) to parade before Washington and some of his generals as had been ordered in Washington's General Orders of May 15th. In his Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene (on page 57), William Johnson in 1822 recounted that, (presumably around or about this event):

It was soon after Greene's arrival on Long Island, and during his command at that post, that he became acquainted with the late General Hamilton, afterwards so conspicuous in the councils of this country. It was his custom when summoned to attend the commander in chief, to walk, when accompanied by one or more of his aids, from the ferry landing to head-quarters. On one of these occasions, when passing by the place then called the park, now enclosed by the railing of the City-Hall, and which was then the parade ground of the militia corps, Hamilton was observed disciplining a juvenile corps of artillerist, who, like himself, aspired to future usefulness. Greene knew not who he was, but his attention was riveted by the vivacity of his motion, the ardour of his countenance, and not less by the proficiency and precision of movement of his little corps. Halt behind the crowd until an interval of rest afforded an opportunity, an aid was dispatched to Hamilton with a compliment from General Greene upon the proficiency of his corps and the military manner of their commander, with a request to favor him with his company to dinner on a specified day. Those who are acquainted with the ardent character and grateful feelings of Hamilton will judge how this message was received. The attention never forgotten, and not many years elapsed before an opportunity occurred and was joyfully embraced by Hamilton of exhibiting his gratitude and esteem for the man whose discerning eye had at so early a period done justice to his talents and pretensions. Greene soon made an opportunity of introducing his young acquaintance to the commander in chief, and from his first introduction Washington "marked him as his own."

Michael E. Newton notes that William Johnson never produced a citation for this tale, and goes on to give a brief historiography of it (Johnson being the first to write about this). While it is possible that General Greene could have sent an aide-de-camp to give his compliments to Hamilton after seeing his parade drill, there is no certain evidence to suggest that Greene introduced Hamilton to George Washington. Newton also notes that "John C. Hamilton failed to endorse any part of the story." (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 150-152).

May 26th: Alexander Hamilton writes a letter to the New York Provincial Congress concerning the pay of his men. Hamilton points out that his men are not being paid as they should be in accordance to rules past, and states that “They do the same duty with the other companies and think themselves entitled to the same pay. They have been already comparing accounts and many marks of discontent have lately appeared on this score.” Hamilton further points out that another company, led by Captain Sebastian Bauman, were being paid accordingly and were able to more easily recruit men.

Also on May 26th: the Provencal Congress approved Hamilton’s request, resolving that Hamilton and his men would receive the same pay as the Continental artillery, and that for every man he recruited, Hamilton would receive 10 shillings. [x]

May 31st: Captain Hamilton receives orders from the Provincial Congress that he, “or any or either of his officers," are "authorized to go on board any ship or vessel in this harbour, and take with them such guard as may be necessary, and that they make strict search for any men who may have deserted from Captain Hamilton’s company.” These orders were given after "one member informed the Congress that some of Captain Hamilton’s company of artillery have deserted, and that he has some reasons to suspect that they are on board of the Continental ship, or vessel, in this harbour, under the command of Capt. Kennedy." Unfortunately, I as of writing this have been unable to find any solid information on this Captain Kennedy to better identify him, or his vessel.

June 8th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that Hamilton "furnish such a guard as may be necessary to guard the Provincial gunpowder" and that if Hamilton "should stand in need of any tents for that purpose" Colonel Curtenius would provide them. It is unknown when Hamilton's company was relieved of this duty, however three weeks later, on June 30th, the Provincial Congress "Ordered, That all the lead, powder, and other military stores" within the "city of New York be forthwith removed from thence to White Plains." [x]

Also on June 8th: the Provincial Congress further orders that "Capt. Hamilton furnish daily six of his best cartridge makers to work and assist" at the "store or elaboratory [sic] under the care of Mr. Norwood, the Commissary."

June 10th: Besides the portion of Hamilton's company that was still guarding the colony's gunpowder, it is seen in a report by Henry Knox (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 920) that another portion of the company was stationed at Fort George near the Battery, in sole command of four 32-pound cannons, and another two 12-pound cannons. Simultaneously, another portion of Hamilton's company was stationed just below at the Grand Battery, where the companies of Captain Pierce, Captain Burbeck, and part of Captain Bauman's manned an assortment of cannons and mortars.

June 17th: The New York Provincial Congress resolves that "Capt. Hamilton's company of artillery be considered so many and a part of the quota of militia to be raised for furnished by the city or county of New-York."

June 29th: A return table, reprinted in Force, Peter's American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 1122 showcases that Alexander Hamilton's company has risen to 99 men. Eight of Hamilton's men--one bombarder, two gunners, one drummer, and four matrosses--are marked as being "Sick [but] present." One sergeant is marked as "Sick [and] absent" and two matrosses are marked as "Prisoners."

July 4th: In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress approves the Declaration of Independence.

July 9th: The Continental Army gathers in the New York City Common to hear the Declaration read aloud from City Hall. In all the excitement, a group of soldiers and the Sons of Liberty (who included Hercules Mulligan) rushed down to the Bowling Green to tear down an equestrian statue of King George III, which they would melt into musket balls. For a history of the statue, see this article from the Journal of the American Revolution.

Also on July 9th: the New York Provincial Congress approve the Declaration of Independence, and hereafter refer to themselves as the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York. [x]

July 12th: Multiple accounts record that the British ships Phoenix and Rose are sailing up the Hudson River, near the Battery, when as Hercules Mulligan stated in a later recollection, "Capt. Hamilton went on the Battery with his Company and his piece of artillery and commenced a Brisk fire upon the Phoenix and Rose then passing up the river. When his Cannon burst and killed two of his men who I distinctly recollect were buried in the Bowling Green." Mulligan's number of deaths may be incorrect however. Isac Bangs records in his journal that, "by the carelessness of our own Artilery Men Six Men were killed with our own Cannon, & several others very badly wounded." Bangs noted further that "It is said that several of the Company out of which they were killed were drunk, & neglected to Spunge, Worm, & stop the Vent, and the Cartridges took fire while they were raming them down." In a letter to his wife, General Henry Knox wrote that "We had a loud cannonade, but could not stop [the Phoenix and Rose], though I believe we damaged them much. They kept over on the Jersey side too far from our batteries. I was so unfortunate as to lose six men by accidents, and a number wounded." Matching up with Bangs and Knox, in his own journal, Lieutenant Solomon Nash records that, "we had six men cilled [sic: killed], three wound By our Cannons which went off Exedently [sic: accidentally]...." A William Douglass of Connecticut wrote to his wife on July 20th that they suffered "the loss of 4 men in loading [the] Cannon." (as seen in Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 142; Newton cites Henry P. Johnston's The Campaigns of 1776 in and around New York and Brooklyn, vol. 2, pg. 67). As these accounts cobberrate each other, it is clear that at least six men were killed. Whether these were all due to Hamilton's cannon exploding is unclear, but is a possibility. Hamilton of course was not punished for this, but that is besides the point.

One of the men injured by the explosion of the cannon was William Douglass, a matross in Hamilton's company (not to be confused with the William Douglass quoted above from Connecticut). According to a later certificate written by Hamilton on September 14th, Douglass "faithfully served as a matross in my company till he lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors date Douglass' injury to June 12th, but it is clear that this occurred on July 12th due to the description Hamilton provides.

July 26th: Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives (who he mistakenly addresses as the "The Honoruable The Provincial Congress") concerning the amount of provisions for his company. He explains that there is a difference in the supply of rations between what the Continental Army and Provisional Army and his company are receiving. He writes that "it seems Mr. Curtenius can not afford to supply us with more than his contract stipulates, which by comparison, you will perceive is considerably less than the forementioned rate. My men, you are sensible, are by their articles, entitled to the same subsistence with the Continental troops; and it would be to them an insupportable discrimination, as well as a breach of the terms of their enlistment, to give them almost a third less provisions than the whole army besides receives." Hamilton requests that the Convention "readily put this matter upon a proper footing." He also notes that previously his men had been receiving their full pay, however under an assumption by Peter Curtenius that he "should have a farther consideration for the extraordinary supply."

July 31st: The Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York read Hamilton's letter of July 26th at their meeting, and order that "as Capt. Hamilton's company was formally made a part of General Scott's brigade, that they be henceforth supplied provisions as part of that Brigade."

A Note On Captain Hamilton’s August Pay Book:

Starting in August of 1776, Hamilton began to keep another pay book. It is evident by Thomas Thompson being marked as the 3rd lieutenant that this was started around August 15th. The cover is below:

For unknown reasons, the editors of The Papers of Alexander Hamilton only included one section of the artillery pay book in their transcriptions, being a dozen or so pages of notes Hamilton wrote presumably after concluding his time as a captain on some books he was reading. The first section of the book (being the first 117 image scans per the Library of Congress) consists of payments made to and by Hamilton’s men, each receiving his own page spread, with the first few pages being a list of all men in the company as of August 1776, organized by surname alphabetically. The last section of the pay book (Image scans 181 to 185) consists of weekly company return tables starting in October of 1776.

As these sections are not transcribed, I will be including the image scans when necessary for full transparency, in case I have read something incorrectly. Now, back to the timeline....

August 3rd: John Davis and James Lilly desert from Hamilton's company. Hamilton puts out an advertisement that would reward anyone who could either "bring them to Captain Hamilton's Quarters" or "give Information that they may be apprehended." It is presumed that Hamilton wrote this notice himself (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 147-148; for the notice, Newton cites The New-York Gazette; and the weekly Mercury, August 5, 12, and September 2nd, 1776 issues).

August 9th: The Convention of the Representatives resolve that "The company of artillery formally raised by Capt. Hamilton" is "considered as a part of the number ordered to be raised by the Continental Congress from the militia of this State, and therefore" Hamilton's company "hereby is incorporated into Genl. Scott's brigade." Here, Hamilton would be reunited with his old friend, Nicholas Fish, who had recently been appointed as John Scott's brigade major. [x]

August 12th: Captain Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives concerning a vacancy in his company. Hamilton explains that this is due to “the promotion of Lieutenant Johnson to a captaincy in one of the row-gallies, (which command, however, he has since resigned, for a very particular reason.).” He requests that his first sergeant, Thomas Thompson, be promoted as he “has discharged his duty in his present station with uncommon fidelity, assiduity and expertness. He is a very good disciplinarian, possesses the advantage of having seen a good deal of service in Germany; has a tolerable share of common sense, and is well calculated not to disgrace the rank of an officer and gentleman.…” Hamilton also requested that lieutenants James Gilleland and John Bean be moved up in rank to fill the missing spots.

August 14th: The Convention of the Representatives, upon receiving Hamilton’s letter of August 12th, order that Colonel Peter R. Livingston, "call upon [meet with] Capt. Hamilton, and inquire into this matter and report back to the House."

August 15th: Colonel Peter R. Livingston reports back to the Convention of the Representatives that, "the facts stated by Capt. Hamilton are correct..." The Convention thus resolves that "Thomas Thompson be promoted to the rank of a lieutenant in the said company; and that this Convention will exert themselves in promoting, from time to time, such privates and non-commissioned officers in the service of this State, as shall distinguish themselves...." The Convention further orders that these resolutions be published in the newspapers.

August ???: According to Hercules Mulligan in his "Narrative" account, Alexander Hamilton, along with John Mason, "Mr. Rhinelander" and Robert Troup, were at the Mulligan home for dinner. Here, Mulligan writes that, after Rhineland and Troup had "retired from the table" Hamilton and Mason were "lamenting the situation of the army on Long Island and suggesting the best plans for its removal," whereupon Mason and Hamilton decided it would be best to write "an anonymous letter to Genl. Washington pointing out their ideas of the best means to draw off the Army." Mulligan writes that he personally "saw Mr. H [Hamilton] writing the letter & heard it read after it was finished. It was delivered to me to be handed to one of the family of the General and I gave it to Col. Webb [Samuel Blachley Webb] then an aid de Champ [sic: aide-de-camp]...." Mulligan expresses that he had "no doubt he delivered it because my impression at that time was that the mode of drawing off the army which was adopted was nearly the same as that pointed out in the letter." There is no other source to contradict or challenge Hercules Mulligan's first-hand account of this event, however the letter discussed has not been found.

August 24th: Alexander Hamilton helped to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Herman Zedwitz from committing treason. On August 25th, a court martial was held (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 5th Series, vol. I, pp. 1159-1161) wherein Zedwitz was charged with "holding a treacherous correspondence with, and giving intelligence to, the enemies of the United States." In a written disposition for the trial, Augustus Stein tells the Court that on the previous day [this date, August 24th] Zedwitz had given him a letter with which Stein was directed "to go to Long-Island with [the] letter [addressed] to Governour Tryon...." Stein, however, wrote that he immediately went "to Captain Bowman's house, and broke the letter open and read it. Soon after. Captain Bowman came in, and I told him I had something to communicate to the General. We sent to Captain Hamilton, and he went to the General's, to whom the letter was delivered." By other instances in this court martial record, it is clear that Stein had meant Captain Sebastian Bauman (and to this, Zedwitz's name is also spelled many different times throughout this record), which would indicate that the "Captain Hamilton" mentioned was Alexander Hamilton, Bauman's fellow artillery captain. Bauman was the only captain serving by that name in the army at this time (see Heitman, Francis B. Historical Register of the Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, pg. 92). It could be possible that Alexander Hamilton personally delivered this letter into Washington's hands and explained the situation, or that he passed it on to one of Washington's staff members.

August 27th: Battle of Long Island — Although Alexander Hamilton was not involved in this battle, for no primary accounts explicitly place him in the middle of this conflict, it is significant to note considering the previous entry on this timeline.

May-August: According to Robert Troup, again in his 1821 letter to John Mason, he had paid Hamilton a visit during the summer of 1776, but did not provide a specific date. Troup noted that, “at night, and in the morning, he [Hamilton] went to prayer in his usual mode. Soon after this visit we were parted by our respective duties in the Army, and we did not meet again before 1779.” This date however, may be inaccurate, for also according to Troup in another letter reprinted later in the William & Mary Quarterly, they had met again while Hamilton was in Albany to negotiate the movement of troops with General Horatio Gates in 1777.

September 7th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington writes that John Davis, a member of Alexander Hamilton's company who had deserted in early August, was recently "tried by a Court Martial whereof Col. Malcom was President, was convicted of “Desertion” and sentenced to receive Thirty-nine lashes." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered that it be carried out "on the regimental parade, at the usual hour in the morning."

September 8th: In his General Orders of this date, Washington writes that John Little, a member of "Col. Knox’s Regt of Artillery, [and] Capt. Hamilton’s Company," was tried at a recent court martial, and convicted of “Abusing Adjt Henly, and striking him”—ordered to receive Thirty-nine lashes...." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered it, along with the other court martial sentences noted in these orders, to be "put in execution at the usual time & place."

September 14th: Hamilton writes a certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who “lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships” on July 12th. Hamilton recommends that a recent resolve of the Continental Congress be heeded regarding “all persons disabled in the service of the United States.”

September 15th: On this date, the Continental Army evacuated New York City for Harlem Heights as the British sought control of the city. According to the Memoirs of Aaron Burr, vol. 1, General Sullivan’s brigade had been left in the city due to miscommunication, and were “conducted by General Knox to a small fort” which was Fort Bunker Hill. Burr, then a Major and aide-de-camp to General Israel Putman, was directed with the assistance of a few dragoons “to pick up the stragglers,” inside the fort. Being that Knox was in command of the Army’s artillery, Hamilton’s company would be among those still at the fort. Major Burr and General Knox then had a brief debate (Knox wishing to continue the fight whereas Burr wished to help the brigade retreat to safety). Aaron Burr at last remarked that Fort Bunker Hill “was not bomb-proof; that it was destitute of water; and that he could take it with a single howitzer; and then, addressing himself to the men, said, that if they remained there, one half of them would be killed or wounded, and the other half hung, like dogs, before night; but, if they would place themselves under his command, he would conduct them in safety to Harlem.” (See pages 100-101). Corroborating this account are multiple certificates and letters from eyewitnesses of this event reprinted in the Memiors on pages 101-106. In a letter, Nathaniel Judson recounted that, “I was near Colonel Burr when he had the dispute with General Knox, who said it was madness to think of retreating, as we should meet the whole British army. Colonel Burr did not address himself to the men, but to the officers, who had most of them gathered around to hear what passed, as we considered ourselves as lost.” Judson also remarked that during the retreat to Harlem Heights, the brigade had “several brushes with small parties of the enemy. Colonel Burr was foremost and most active where there was danger, and his con-duct, without considering his extreme youth, was afterwards a constant subject of praise, and admiration, and gratitude.”

Alexander Hamilton himself recounted in later testimony for Major General Benedict Arnold’s court martial of 1779 that he “was among the last of our army that left the city; the enemy was then on our right flank, between us and the main body of our army.” Hamilton also recalled that upon passing the home of a Mr. Seagrove, the man left the group he was entertaining and “came up to me with strong appearances of anxiety in his looks, informed me that the enemy had landed at Harlaam, and were pushing across the island, advised us to keep as much to the left as possible, to avoid being intercepted….” Hercules Mulligan also recounted in his “Narrative” printed in the William & Mary Quarterly that Hamilton had “brought up the rear of our army,” and unfortunately lost “his baggage and one of his Cannon which broke down.”

September 28th: In his General Orders of this date, Washington wrote that William Higgins of Hamilton’s artillery was “convinced by a General Court Martial” where “Col. Weedon is President” for the crime of “‘plundering and stealing’.” Higgins was “ordered to be whipped Thirty-nine lashes.” Although this noted court martial is written in the present tense, the editors of The George Washington Papers reveal in the second note of the document that Higgins was “convicted the previous day [September 27th] for having “‘[broken] open a Chest & stealing a Number of Articles out of it in a Room of the Provost Guard’” as was written in the court marrial’s proceedings, which can be found in the Library of Congress’ George Washington Papers.

September ???: As can be seen in Hamilton's August 1776-May 1777 pay book, while stationed in Harlem Heights (often abbreviated as "HH" in the pay book), nearly all of Hamilton's men received some sort of item, whether this be shoes, cash payments, or other articles.

October 4th: A return table for this date appears in Alexander Hamilton’s pay book, in the back. These return tables are not included in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton for unknown reasons.

The table, as seen above, provides us a snapshot of Hamilton’s company at this time, as no other information survives about the company during October. His company totaled to 49 men. Going down the table, two matrosses were “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder, four gunners, and six matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and two matrosses were marked as “On Furlough.” Interestingly, another two matrosses were marked as having deserted, and two matrosses were marked as “Prisoners.”

October 11th: In Hamilton’s pay book, below the table of October 4th, another weekly return table appears with this date marked.

The return table, as seen above, again records that Hamilton’s company consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, two matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and one captain-lieutenant [being James Moore], one sergeant, and two matrosses were marked as being “On Furlough.”

To the right of the date header, in place of the usual list of positions, there is a note inside the box. The note likely reads:

Drivers. 2_ Drafts_l?] 9_ 4 of which went over in order to get pay & Cloaths & was detained in their Regt [regiment]

Drafts were men who were drawn away from their regular unit to aid another, and it’s clear that Hamilton had many men drafted into his company. This note tells us that four of these men were sent by Hamilton to gather clothing for the company, and it is likely that they had to return to their original regiment before they could return the clothing. This, at least, makes the most sense (a huge thank you to @my-deer-friend and everyone else who helped me decipher this)!! In the bottom left-hand corner of the page, another note is present, however I am unable to decipher what it reads. If anyone is able, feel free to take a shot!

October 25th: Another weekly returns table appears in Hamilton’s company pay book. Once more, this table of returns was not transcribed within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

The table, as seen above, shows that Hamilton’s company still consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, it can be seen that one matross and one drummer/fifer were “Sick [but] present,” and one sergeant, two bombarders, one gunner, and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent.” Interestingly, one matross was noted as being “Absent without care”. Two matrosses were listed as “Prisoners” and again two matrosses were listed as having “Deserted.”

Underneath the table, a note is written for which I am only able to make out part. It is clear that two men from another captain’s company were drafted by Hamilton for his needs.

October 28th: Battle of White Plains — Like with Long Island, there is no primary evidence to explicitly place Alexander Hamilton, his men, or his artillery as being involved in this battle, contrary to popular belief. See this quartet of articles by Harry Schenawolf from the Revolutionary War Journal.

November 6th: Captain Hamilton wrote another certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who was injured during the attacks on July 12th. This certificate is nearly identical to the one of September 14th, and again Hamilton writes that Douglass is “intitled to the provision made by a late resolve of the Continental Congress, for those disabled in defence of American liberty.”

November 22nd: As can be seen in Hamilton's pay book, all of his men regardless of rank received payments of cash, and some men articles, on this date.

December 1st: Stationed near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General Washington wrote in a report to the President of Congress, that the British had formed along the Heights, opposite New Bunswick on the Raritan River, and notably that, "We had a smart canonade whilst we were parading our Men...." Alexander Hamilton's company pay book placed he and his men at New Brunswick in around this time (see image scans 25, 28, 34, and others) making it likely that Hamilton had been present and helped prevent the British from crossing the river while the Continental Army was still on the opposite side. In his Memoirs of My Own Life, vol. 1, James Wilkinson recorded that:

After two days halt at Newark, Lord Cornwallis on the 30th November advanced upon Brunswick, and ar- Dec. 1. rived the next evening on the opposite bank of the Rariton, which is fordable at low water. A spirited cannonade ensued across the river, in which our battery was served by Captain Alexander Hamilton,* but the effects on eitlierside, as is usual in contests between field batteries only, were inconsiderable. Genei'al Washington made a shew of resistance, but after night fall decamped...

Though Wilkinson was not present at this event, John C. Hamilton similarly recorded in both his Life of Alexander Hamilton [x] and History of the Republic [x] that Hamilton was part of the artillery firing the cannonade during this event. Though there is no firsthand account of Hamilton's presence here, it is highly likely that he and his company was involved in holding off the British so that the Continental Army could retreat.

December 4th?: Either on this date, or close to it, Alexander Hamilton’s second lieutenant, James Gilleland, left the company by resigning his commission to General Washington on account of “domestic inconveniences, and other motives,” according to a later letter Hamilton wrote on March 6th of 1777.

December 5th: Another return table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress. This table is headed, "Return of the States of part of two Companeys of artilery Commanded by Col Henery Knox & Capt Drury & Capt Lt Moores of Capt Hamiltons Com." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table, and note that Hamilton's "company had been assigned at first to General John Scott’s brigade but was soon transferred to the command of Colonel Henry Knox." They also note that the table "is in the writing of and signed by Jotham Drury...." [x]

The table, as seen above, notes part of the "Troop Strength" (as the Library of Congress notes) of Captain Jotham Drury and Captain Alexander Hamilton's men. As regards Hamilton's company, the portion that was recorded here amounted to 33 men.

December 19th: Within his Warrent Book No. 2, General George Washington wrote on this date a payment “To Capn Alexr Hamilton” for himself and his company of artillery, “from 1st Sepr to 1 Decr—1562 [dollars].” As reprinted within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

December 25th: Within Bucks County, Pennsylvania, hours before the famous Christmas Day crossing of the Delaware River by Washington and the Continental Army, Captain-Lieutenant James Moore passed away from a "short but excruciating fit of illness..." as Hamilton would later recount in a letter of March 6th, 1777. According to Washington Crossing Historic Park, Moore has been the only identified veteran to have been buried on the grounds during the winter encampment. His original headstone read: "To the Memory of Cap. James Moore of the New York Artillery Son of Benjamin & Cornelia Moore of New York He died Decm. the 25th A.D. 1776 Aged 24 Years & Eight Months." [x] In his aforementioned letter, Alexander Hamilton remarked that Moore was "a promising officer, and who did credit to the state he belonged to...." As Hamilton and Moore spent the majority of their time physically together (and therefore leaving no reason for there to be surviving correspondence between the two), there is no clear idea of what their working relationship may have looked like.

December 26th: Battle of Trenton — Alexander Hamilton is believed to have fought in he battle with his two six-pound cannons, having marched at the head of General Nathanael Greene's column and being placed at the end of King Street at the highest point in the town. Michael E. Newton does note however that there is no direct, explicit evidence placing Hamilton at the battle, but with the knowledge of eighteen cannons being present as ordered by George Washington in his General Orders of December 25th, it is highly likely the above was the case (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 179-180; Newton cites a number of sources for circumstantial evidence: William Stryker's The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, Jac Weller's "Guns of Destiny: Field Artillery In the Trenton-Princeton Campaign" [Military Affairs, vol. 20, no. 1], and works by Broadus Mitchell).

December ???: Within Hamilton’s pay book, a note appears for December on the page dedicated to Uriah Crawford (not to be confused with Uriah Chamberlain, as evidenced by both men appearing separately in the pay roll of March-April, 1776), a matross in his company. See a close up of the image scan below.

The note likely reads:

To Cash [per] for attendance during sickness [ampersand?] funeral expenses —

This note would thus indicate that Chamberlain likely passed away and a funeral was held, or attend the funeral of someone else, sometime during the month. That Hamilton paid the expenses for the funeral is quite a telling note. Chamberlain was also provided a pair of stockings in December.

Final Months - 1777:

January 2nd: Battle of Assumpink Creek — Near Trenton, the Continental Army positioned itself on one side of the Assumpink Creek to face the approaching British, who sought to cross the bridge into Trenton. In a letter of January 5th to John Hancock, Washington explained that "They attempted to pass Sanpink [sic: Assumpink] Creek, which runs through Trenton at different places, but finding the Fords guarded, halted & kindled their Fires—We were drawn up on the other side of the Creek. In this situation we remained till dark, cannonading the Enemy & receiving the fire of their Field peices [sic: pieces] which did us but little damage." According to James Wilkinson, who was present at this battle, Hamilton and his cannons were present. [x] Corroborating this, Henry Knox wrote in a letter to his wife of January 7th that, "Our army drew up with thirty or forty pieces of artillery in front", and an anonymous eyewitness account which noted that "within sevnty of eighty yards of the bridge, and directly in front of it, and in the road, as many pieces of artillery as could be managed were stationed" to stop the crossing of the British (see Raum, John. History of the City of Trenton, New Jersey, pp. 173-175). Further, another eyewitness account from a letter written by John Haslet reported a similar story (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 181; for Haslet's account, Newton cites Johnston, Henry P. The Campaigns of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn, Vol. 2, pg. 157). This surely would have been a sight to behold.

January 3rd: Battle of Princeton -- Overnight, the Continental Army marched to Princeton, New Jersey with a train of artillery. Once more, Alexander Hamilton was not explicitly mentioned to have been present at the battle, however with 35 artillery pieces attacking the British (see again Henry Knox's letter of January 7th), and the large role these played in the battle, there is little doubt that Hamilton and his men played a part in this crucial victory (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 182). According to legend, one of Hamilton's cannons fired upon Nassau Hall, destroying a painting of King George II. However, this has been disproven by many different scholars and writers, including Newton.

January 20th: In a letter to his aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hansen Harrison, George Washington requests Harrison to “forward the Inclosed to Captn Hamilton….” Unfortunately, the letter Washington intended to be given to Alexander Hamilton has not been found. It is believed by both the editors of Washington and Hamilton’s papers that this letter contained Washington’s request for Hamilton to join his military family.

Also on January 20th: Many of Hamilton’s men received payments of cash on this date. Alongside cash, one man, John Martim, a matross in Hamilton’s company, was paid cash “per [Lieutenant] Thompson” for his “going to the Hospital.” The hospital in particular, and the circumstances surrounding Martim’s stay are unknown. [x]

January 25th: As printed in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, an advertisement appeared in the Pennsylvania Evening Post directly naming Hamilton. Only one sentence, the advertisement alerts Hamilton that he “should hear something to his advantage” by “applying to the printer of this paper….” Presumably this regarded George Washington wishing to make Hamilton his newest aide-de-camp.

January 30th: Alongside cash, a greatcoat, and cash per “Doctor [Chapman?]” and a cash balance due to him, Alexander Hamilton paid his third lieutenant Thomas Thompson for gathering “sundries in Philadelphia” and for his “journey to Camp”. See close up of the image scan below. [x]

Several other later pages in the pay book indicate that Hamilton and his men were in Philadelphia at some point in January and February. It is thus plausible that Hamilton went to see the printer of the Pennsylvania Evening Post and it may be possible that Lieutenant Thompson had accompanied him and have had picked up his items while in the city, however whether or not Hamilton actually made that journey, and Thompson’s involvement are my speculation only. It is also entirely possible that Thompson's "journey to Camp" was in reference to seeing the doctor, and had picked up the "sundries" then.

March 1st: At Morristown, New Jersey, in his General Orders of this date, George Washington announces and appoints Alexander Hamilton “Aide-De-Camp to the Commander in Chief,” and wrote that Hamilton was “to be respected and obeyed as such.”

March 6th: Alexander Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his artillery company for the last time. Hamilton explains a delay in writing due to having only “recently recovered from a long and severe fit of illness.” He goes on to explain the state of the company—that only two officers, lieutenants Thomas Thompson and James Bean, remained with the company and that Lieutenant Johnson "began the enlistment of the Compan⟨y,⟩ contrary to his orders from the convention, for the term of a year, instead of during the war" which, Hamilton explained, "with deaths and desertions; reduces it [the company] at present to the small number of 25 men." Hamilton then requests that Thomas Thompson be raised to Captain-Lieutenant, for Lieutenant Bean, "is so incurably addicted to a certain failing, that I cannot, in justice, give my opinion in favour of his preferment."

Remarkably, the New York Provincial Company of Artillery still survives to this day, and is the longest (and oldest) continually serving regular army unit in the history of the United States. For a deeper history of the company up to the present day, see this article from the American Battlefield Trust. The company are commonly referred to as “Hamilton’s Own” in honor of the young man who raised the company in 1776.

#I put WAY too much effort into this 😭#I really hope this is useful to someone and not just me lol#grace's random ramble#alexander hamilton#amrev#historical alexander hamilton#captain hamilton#amrev fandom#timelines#the new york provincial company of artillery#american history#american revolution#the american revolution#battle of trenton#battle of princeton#ten crucial days#historical timelines#historical research#george washington#continental army#reference#the american icarus#TAI#historical hamilton#aaron burr#hercules mulligan#robert troup#nathanael greene#18th century correspondence#18th century history

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

all of God's creatures

.

Joshua Tobey

::

Masao Yamamoto - Birds

::

Southern Song Dynasty 12th c.

::

American glazed earthenware brick, late 19th or early 20th c.

::

Andy Warhol - Archie the dog, Polaroid

::

Greer Lankton

::

Japan, Meiji period, 1880

::

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi - Flora and Fauna

::

John Wilhelm

::

Scott Prior - Two Cows

::

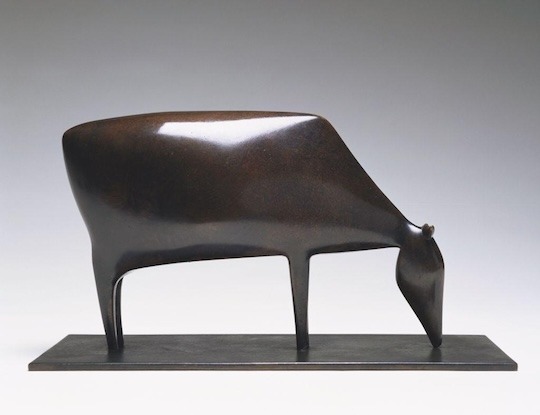

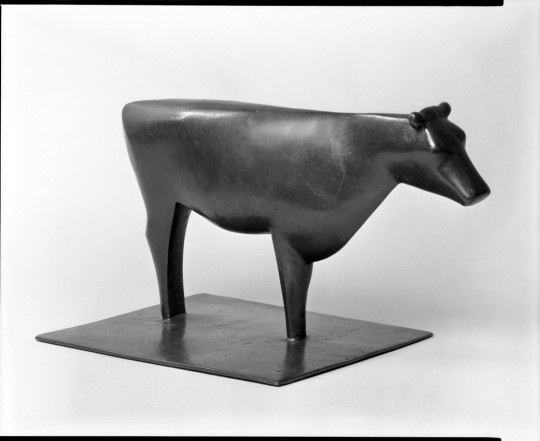

Ewald Mataré - Grazing Cow

::

Polar bear, whale skeleton

::

Shōmosai Masamitsu - Fox, early 19c.

::

Joe Brainard - Whippet on a Green Couch

::

Yoshitomo Nara

::

William Wegman - Farmer and Son

::

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Victor Ewald (1860-1935) - Brass Quintet No. 1 in B-flat minor, Opus 5 (c. 1890; rev. 1912)

The Center Brass Quintet :

Aaron Montoya, trumpet • Luke Harju, trumpet

Rubén Pérez Alonso, horn • Jeremiah Umholtz, trombone;

Elizabeth Speltz, tuba

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

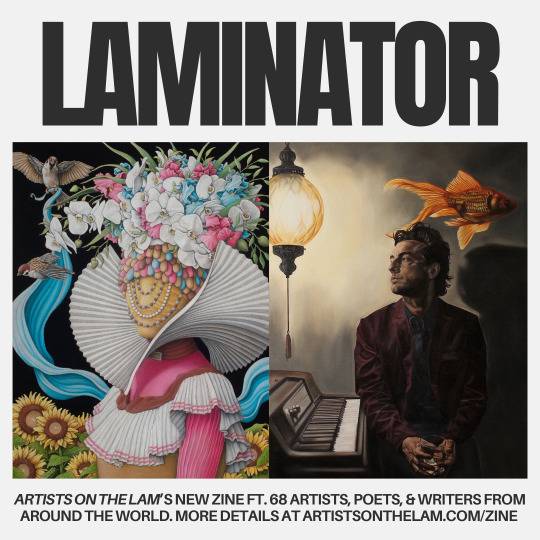

Love to LA. 💛 Embrace (2020), watercolor on paper, a self-portrait by Fei Ewald (Los Angeles, California) in my zine, LAMINATOR Vol. 1.

Fei is a Singaporean-American artist creating with anything she can get her hands on, literally. Working through grief and loss, she learned to entangle her memories with the tangible world by weaving, printmaking, and painting. While her practice still invokes the past, her present focus is the joy of working with accessible, everyday materials. As her dad used to say, “When in doubt, have fun!”

LAMINATOR (c) Jenny Lam 2024

#watercolor#watercolour art#painting#paper#paper art#los angeles#la artist#california#california artist#grief#love#portrait#art#artists on tumblr#zine#art zine#artwork#women in art#female artists#loss

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[E. The world takes shape from the most elementary forms of the activity of consciousness - cont'd]

[2. In the Philosophie der Arithmetik, Husserl was already beginning to describe this region where the unity of the lived and the known opened up on the horizon of the world - cont'd]

c. Now, [regarding intentionality]

it is not part of our project to undertake the analysis of its historical context nor [that] of its philosophical implications

we would simply like to situate intentional analysis according to its original meaning, as a thematic form of analysis of lived experience

Of the six characteristics that Brentano assigned to intentionality, Husserl recognizes only two: and these two, it must be said, are

the most general

the most abstract

those which carry the least radical significance for the subsequent developments of intentional analysis

i. As a decisive property of consciousness, intentionality can be defined as the mode of relation of consciousness to its content; and to this extent, intentionality always implies

– not real, actual (wirklich) content [as if an effect of the outside world on consciousness],

– but at least the presence of [an internal] content which may be

real or unreal

perceived or fictitious

etc.

“I imagine Jupiter just like Bismarck, the tower of Babel just like the cathedral of Cologne”;

– Michel Foucault, The Essence of Lived Experience, d'après Phénoménologie et psychologie, ca. 1954, BnF, Fonds Foucault, NAF 28730, boîte 46, dossier 2, établie par Sabot et Ewald

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

SATANIC HISPANICS | Trailer, Poster & Images

Satanic Hispanics is an anthology of 5 short films from some of the leading Latin filmmakers in the horror genre, spotlighting Hispanic talent both in front and behind the camera.

When police raid a house in El Paso, they find it full of dead Latinos, and only one survivor. He’s known as The Traveler, and when they take him to the station for questioning he tells them those lands are full of magic and talks about the horrors he’s encountered in his long time on this earth, about portals to other worlds, mythical creatures, demons and the undead. Stories about Latin American legends.

Directed by Mike Mendez, Demián Rugna, Eduardo Sánchez, Gigi Saul Guerrero, and Alejandro Brugués.

Written by Alejandro Mendez, Demián Rugna, Pete Barnstrom, Lino K. Villa, Shadan Saul, Raynor Shima; and starring Patrick Ewald, Mike Mendez, Alejandro Brugués; starring Efren Ramirez, Greg Grunberg, Hemky Madera, Jonah Ray Rodrigues, Patricia Velásquez, Jacob Vargas, Ari Gallegos, Demian Salomon, Christian Rodrigo, and Michael C. Williams.

DREAD's SATANIC HISPANICS in Theaters September 14th, 2023.

#youtube#dread#satanic hispanics#trailer#poster#images#horror#latin#mike mendez#demián rugna#eduardo sánchez#gigi saul guerrero#alejandro brugués

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

HRCYED 2: July Plan | Pt. 1

Time frame: July 7th ~ August 7th

Books in order:

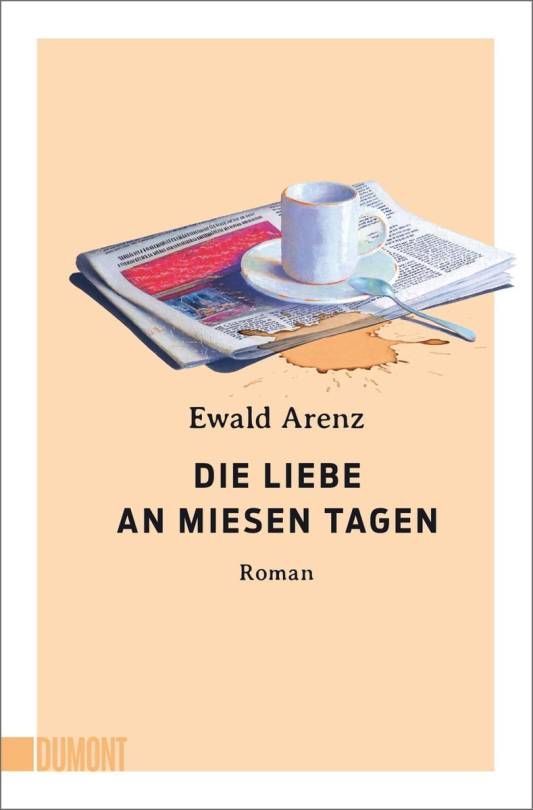

Die Liebe an miesen Tagen, Ewald Arenz (2023) | Pages: 384

Der Duft von Schokolade, Ewald Arenz (2007) | Pages: 272

The Hobbit, J. R. R. Tolkien (1937) #0 | Pages: 389

Davyan - Der Aschenprinz, C. M. Spoerri (2023) #1 | Pages: 464

Die Tanzenden, Victoria Mas (2019) | Pages: 240

Dracula, Bram Stoker (1897) | Pages: 454

Total Page Count: 2203

The first half of the books I'm planning to read for July! I planned the first month of the reading challenge to be impossible to complete on purpose, because I lowkey wanted to find out the hard way how many books I can read in said time frame. I really don't have any expectations, but I know this is going to challenge me a lot.

Still, July will be the last month I'm unemployed and have the time to read a lot. After that I either forget the challenge even existed (joking- ..I hope), or it's simply getting way less books that I manage to read per month.

Read prompts:

Readathon challenge (Year in Aeldia): 6/12

By the 100s: 3/7

Even Bigger Rainbow: 1/14

Last 10 Years: 1/12

Spooky Creatures: 1/8

Completed Challenges: 0/25

1 note

·

View note

Text

Einsatznachtrag

Donnerstag 19.06.2025

Einsatz: 1236

Gegen 20:53 Uhr wurden die Feuerwehren der Stadt Alzenau, Kahl und die Feuerwehrinspektion Aschaffenburg-Land 3 zu einer Technischen Hilfeleistung 2 | VU - mehrere PKW auf die Staatsstraße 2808 alarmiert.

Schwerer Verkehrsunfall mit sechs Verletzten – Fahrzeuge in Vollbrand auf der Strecke zwischen Alzenau und Kahl

Am Donnerstag, den 19. Juni 2025, wurde die Freiwillige Feuerwehr Alzenau um 20:53 Uhr zu einem Verkehrsunfall auf der Ortsverbindungsstraße zwischen Alzenau und Kahl alarmiert. Auf der Staatsstraße 2805 kam es zu einem Frontalzusammenstoß zwischen einem Skoda Kodiaq, in dem sich eine vierköpfige Familie befand, und einem Peugeot 206 CC, besetzt mit zwei jungen Frauen. Die Unfallursache ist derzeit Gegenstand polizeilicher Ermittlungen.

Beim Eintreffen der ersten Feuerwehrkräfte standen beide Fahrzeuge bereits in Vollbrand. Ersthelfer hatten sich bis dahin bereits um die teils schwer verletzten Insassen gekümmert. Ein Rettungswagen und ein Notarzt waren ebenfalls bereits vor Ort.

Die Feuerwehrsanitäter unterstützten umgehend die medizinische Versorgung der insgesamt sechs verletzten Personen, darunter zwei kleine Kinder im Alter von einem und sieben Jahren. Einige Beteiligte erlitten schwere bis lebensbedrohliche Verletzungen.

Parallel wurde die Brandbekämpfung unter schwerem Atemschutz mit zwei C-Rohren und einem Schaumrohr eingeleitet. Für die sichere Landung des Rettungshubschraubers wurde ein geeigneter Landeplatz in unmittelbarer Nähe vorbereitet. Die Staatsstraße 2805 wurde währenddessen im Auftrag der Polizei voll gesperrt. Hierfür wurde die Freiwillige Feuerwehr Kahl nachalarmiert.

Aufgrund der starken Rauchentwicklung und der bevorstehenden Landung eines Rettungshubschraubers musste auch der Zugverkehr auf der parallel verlaufenden Bahnstrecke Alzenau–Kahl vorübergehend vollständig eingestellt werden. Nach Abschluss der Löscharbeiten sowie der Lande- bzw. Startphase des Rettungshubschraubers konnte der Bahnverkehr in enger Abstimmung mit dem anwesenden Notfallmanager der Bahn langsam an der Unfallstelle vorbeigeführt werden – bis die Bergungsarbeiten vollständig abgeschlossen waren.

Nach der notärztlichen Erstversorgung wurden alle Verletzten zur weiteren Behandlung in umliegende Kliniken gebracht.

Im Einsatz waren unter der Leitung von Einsatzleiter Rettungsdienst Florian Ewald vom Malteser Hilfsdienst Aschaffenburg insgesamt sechs Rettungswagen, zwei Notarzteinsatzfahrzeuge, ein Rettungshubschrauber sowie der Helfer vor Ort (HvO) Alzenau.

Der Einsatzleiter der Feuerwehr, Kommandant Timo Elsesser, konnte auf rund 50 Einsatzkräfte mit neun Fahrzeugen zurückgreifen. Kreisbrandinspektor Georg Thoma unterstützte ihn bei der Einsatzführung.

Nach der Unfallaufnahme durch die Polizei sowie einen von der Staatsanwaltschaft hinzugezogenen Gutachter wurde die Fahrbahn gereinigt und die ausgebrannten Fahrzeuge durch ein Bergungsunternehmen abtransportiert.

Eingesetzte Fahrzeuge:

Feuerwehr Alzenau 11/1

Feuerwehr Alzenau 12/1

Feuerwehr Alzenau 23/1

Feuerwehr Alzenau 40/1

Feuerwehr Alzenau 56/1

Feuerwehr Alzenau 61/1

Weitere Kräfte:

Feuerwehr Kahl 23/1

Feuerwehr Kahl 40/1

Feuerwehr Kahl 56/1

Feuerwehrinspektion Aschaffenburg-Land 3

Rettungsdienst mit Sechs Fahrzeugen

Notarzt mit zwei Fahrzeugen

Einsatz Leiter Rettungsdienst (Malteser)

Helfer Vor Ort Alzenau

Rettungshubschrauber Christoph 2

Abschleppdienst mit zwei Fahrzeugen

Straßenbaulastträger

0 notes

Text

73 muestra internacional de cine en la @cinetecanacionalmx

Sparta

Austria-Alemania-Francia, 2022, 101 min.

D: Ulrich Seidl. G: Ulrich Seidl y Veronika Franz. F en C: Wolfgang Thaler y Serafin Spitzer. E: Monika Willi. Con: Georg Friedrich (Ewald), Hans-Michael Rehberg (padre de Ewald), Florentina Elena Pop (novia de Ewald), Marius Ignat, Octavian-Nicolae Cocis. CP: Ulrich Seidl Filmproduktion, Arte France Cinéma, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Parisienne de Production, Essential Filmproduktion, Parisienne de Production. Prod: Philippe Bober, Michel Merkt y Ulrich Seidl. Dist: PIANO.

Buscando comenzar una nueva vida, Ewald deja a su novia y su trabajo, y se traslada a un páramo rural empobrecido de Rumania. Con la ayuda de niños de la zona, transforma una escuela en ruinas en una fortaleza donde puedan jugar libremente. Sin embargo, la desconfianza no tardará en surgir entre los habitantes y Ewald tendrá que enfrentarse a una verdad reprimida durante mucho tiempo. Sparta es la película hermana de Rimini (2002) que culmina el díptico de Ulrich Seidl sobre la imposibilidad de escapar del pasado y el dolor de encontrarse a uno mismo. El director austriaco continúa su exploración de los aspectos más oscuros de la naturaleza humana, evitando al mismo tiempo la provocación fácil.

#cinetecanacional #muestrainternacionaldecine #cine #kino #film #laultimafunciondecine #sparta

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Your Likeness | Chapter 1 - Common grounds

Chapter 1 | Common grounds

Chapter warnings: Violence, blood, political conflict

For all tags, see AO3 : GoingHaywire

For more information, join my Hitman related Discord server

“Welcome to Jerusalem, 47.” Diana Burnwood’s voice stated through Agent 47’s earpiece. He stood as usually taciturn and obedient, analysing his surroundings. On the expanse of his head laid a kippah, donned as a distraction, out of place compared to the crisp black suit barely matching it.

But then, men of Jewish descent had no set appearance, so no one would question him too much. Not when he was in the holiest city of them all.

“Before you, you see the building of The Knesset, which holds the unicameral legislative branch of the Israeli government. Naturally, a restless country like this one has a fair bit of security around its political buildings. Despite its youth, this land holds secrets, one of them going by the name of Ewald Cohen. A powerful Jewish man, currently seeking aid for a wicked plan dabbling into force-migration. Long story short, he pleas for a Palestinian removal act. Our client wants him out of business, as to be expected. And so, it shall be done. Good luck, 47. And remember, I know it’s unlike you, but no unnecessary blood, especially not in there. It would mean a lockdown of the city, and the last thing we need is ourselves blowing our own cover.”

Agent 47 let his icy eyes take in every inch of the building before him – yellow brick, like a large box placed in the middle of a city, yet it had something of a temple – something ancient, like Jerusalem itself. He was not one for pretty architecture, though found interest in knowing how to get in – and out.

The way he looked now, he knew there would be no way that he could get past security without being frisked – if he took the main entrance, that was. Metal-detecting gates would be too troublesome at the moment. And without the correct papers, he wouldn’t get past the front desk, not with all those guards around.

The first thing one would notice was the plenty presence of soldiers, standing on watch. Judging by the stance of one of the younger men, 47 deduced that the change might soon be there. He should take advantage of it, knock one of them out and don a disguise. In the crowd, he’d be hardly noticed.

Deciding it the best approach, he made his way to a more secluded area, successfully knocking out a guard after distracting him, and put on his uniform. He discarded of his suit and the kippah by stuffing them into the stranger’s backpack, hiding the unconscious body of the soldier in the shrubbery. 47 brought the backpack with him, going forth.

In the distance, doors opened. Right in time, he thought to himself, creeping back to the place where the guard had stood. A new row of guards went up to the ones standing at the gates, freshly uniformed and without dark circles under their eyes, like the ones that the men at the gate had been sporting.

A wordless exchange, 47 mimicked his temporary peers with a gesture to the side of the head, saluting them. One of them raised an eyebrow, unfamiliar with the piercing blue eyes meeting his.

But then, the IDF stood never still in the stream of new guards, with drafted soldiers in their late teenage years obligated to serve a short time. There would be new recruits every time of day, so there lingered no long suspicion.

He followed them inside, proceeding through the halls until they stopped at what seemed like a canteen. It had never been so easy to march into such an important building with an automatic weapon in hand.

“I hadn’t noticed you taking over Adam’s shift.”

Agent 47 had already taken off the boots he had been wearing - a size too small - when he noticed that he was being spoken to. Before him stood a young man, no older than twenty-five, a toothpick between his chapped lips.

“Oh, yes. Adam felt ill so I was sent to take his place.”

“I don’t recognise you.”

“I haven’t been here for long.”

“You don’t seem to be drafted, either. What’s a man of your age doing in the lowest rank?”

47 sighed, feigning exhaustion. “Listen, yadid. I’ve been standing all day and I’m tired.”

The young man let out a scoff. “I’m not your friend, old man. Well then, guess your age is getting the better of you. Have fun returning home with your walking stick.”

“Shlomo!” a man of higher status called, sending him a warning glare. “Stop picking on our new recruits.”