#by John Seabrook of the new yorker

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

With the news in Hathras, India, remember that crowd crush (NOT a stampede) is 100% preventable and 100% the responsibility of organizers of events and local authority, NOT the people or victims involved in the crush, who often do not even realize that there is a crush occuring

Link about Hathras:

Link about crushes vs "stampedes", and why you should be wary of the use of the latter word:

#text#this is a very specific issue I have but. just getting this out ahead of things#dont interact w media calling it a stampede#the word stampede is specifically used to undermine people In a crush#by portraying them as wild animals instead of. you know. logical and compassionate human beings who are panicked and don't have all#of the information to make decisions to avoid a crush during.#which could be avoided if authorities intervened since they have methods to communicate over radio and should be prepared for large crowds#anyway .#india#hathras#death tw#a2t#also will recommend the long and incredible article Crush Point#by John Seabrook of the new yorker#covers much of the same issues but in more depth

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

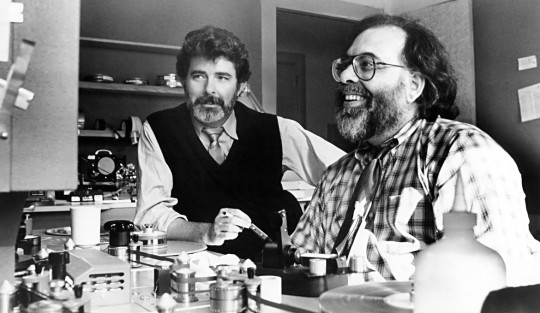

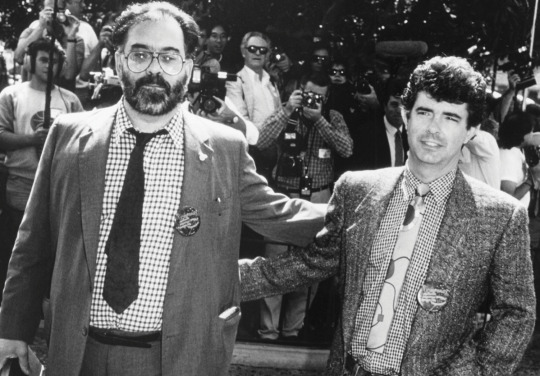

Lucas & Coppola: the inspiration for Obi-Wan and Anakin's relationship.

So I was going through this old article of The New Yorker and came across this quote:

"Just as a benevolent father figure (Obi-Wan) helps Luke in his struggle against his dark father, the older Coppola took young George under his wing at film school, and helped him get his first feature film made." - John Seabrook, The New Yorker, 1997

Now, it's known that Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas were close friends, but after looking further into it, there's some interesting parallels to be made:

Coppola started out as a mentor figure, taking Lucas on as a protégé.

He helped George get THX-1138 and American Graffiti off the ground. Lucas filmed second unit shots for The Godfather and assisted in the editing, developed the script for Apocalypse Now with John Milius.

Overtime, their relationship had blossomed into a more brotherly one, with them becoming "equals".

"[Our relationship is] sort of "mentor-mentee". I mean, he's taught me everything. He's five years older than I am but, you know, when you're 20 and 25 years old, that's a big gap. And so, he's always been my mentor and helped me get through everything. You know, we've know each other for, you know, what? Over 35 years now. And so, the relationship is more brotherly than it probably is mentor-mentee at this point. It's more older brother-younger brother kind of thing. [...] We pretty much are equal in terms of what we know about what we're doing."

Sound familiar?

Wait 'til you hear about the dynamics of their friendship:

"Francis and I, we were very good friends right from the moment we met. Uh, we’re very different."

"Francis is very flamboyant and very Italian and very, sort of, “go out there and do things!”"

"I'm very, sort of, “let's think about this first, let's not just jump into it.” Um, and so he used to call me the “85-year-old man.”"

"But together, we were great. Because, y’know, I would kinda be the weight around his neck that slowed him down a little bit to keep him from getting his head chopped off. "

"And, uh, on— aesthetically and everything, we sort of had very compatible sensibilities in terms of that. I was strong in one area, he was strong in another, and so we could really bounce ideas off of each other. But we were very much the opposite, in the way we operated and the way we did things... and that, I think, allowed us to have a very active relationship."

A mentor-mentee relationship that turned into a brotherly one.

Two men with opposite personalities - one more outgoing, the other more cautious - that complemented each other's beautifully.

Yin and Yang.

Just like Obi-Wan with Anakin (or Obi-Wan with Qui-Gon, if we wanna talk about the mentee needing to slow the mentor down a bit so he doesn't get into trouble).

So I dunno if there's more to it, but when I read all this... I read one more reason (in addition to the others) for why the "Anakin and Obi-Wan weren't compatible enough, Qui-Gon should've been the Master because they had more in common" interpretation doesn't track.

Like, if that's your opinion/theory, cool.

But there is no way you'll convince me that the author - who had almost that exact bond with Coppola - would then go and intentionally write Obi-Wan and Anakin's bond as lacking and "a failing for Anakin".

Edit:

Just found this quote and I figured I'd add 'em :D

"[After the Warner Bros scholarship] I had a choice between going back to graduate school or going off on this little adventure, and I decided to go off on the adventure with Francis."

Edit #2:

Said Stephen Spielberg in the George Lucas 2016 biography "A Life":

“I think Francis always looked at George as sort of his upstart assistant who had an opinion. An assistant with an opinion, nothing more dangerous than that, right?”

A description reminiscent of both the Qui-Gon/Obi-Wan dynamic but also... kinda the Obi-Wan/Anakin one.

#bts tidbits#francis ford coppola#george lucas#obi-wan kenobi#anakin skywalker#star wars#collection of quotes#obi wan and anakin#I'd also argue Lucas and Coppola's relationship was a basis for Han and Luke's relationship too...

371 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cynthia Kittler’s illustration of Kendrick Lamar, Lady Gaga and Thom Yorke for John Seabrook’s article about Coachella in this week’s New Yorker magazine.

#Cynthia Kittler#Great Illustration#Kendrick Lamar#Lady Gaga#Thom Yorke#John Seabrook#Coachella#The New Yorker Magazine

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Florence Welch Interview

Transcript of Florence Welch’s interview with John Seabrook for the New Yorker Festival.

October 11th, 2019.

New York, NY.

Edited for clarity.

John Seabrook: I’m going to properly introduce you because I think a woman this accomplished needs a proper introduction. For those of you who read the New Yorker this week, let me assure you that I wrote this myself, no machine helping me. In ten years as a band, Florence and the Machine have released four chart topping, award winning studio albums. Lungs, 2009, Ceremonials, 2011, How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful, 2015, and High as Hope last year. These many-layered works weave together a range of different styles, from the bands punky first single “Kiss With a Fist,” to the rich choral and percussive tapestries of songs like “Shake It Out,” to Neo-Soul such as “Where Is the Love” (sic), and to the startlingly honest lyrics of “Hunger.” Heartbreak and loneliness rarely feel as delightful and inviting as in a Florence Welch song. The music performs the very rare trick of remaining true to its indie roots while at the same time, sounding expansive and monumental. While British listeners sometimes look to Kate Bush as a musical antecedent, here in New York, we are maybe more inclined to think of Patti Smith, in her path-finding career as a poet who found a way to address the big issues of literature, death, love loneliness, and beauty in the idiom popular song. And we are especially inclined to think of you as following Patti tonight because you are literally sitting in the seat that Patti was warming only an hour ago.

The band has also released two live albums that established themselves as major festival headliners, with a sound big enough to fill the green fields of Glastonbury and deserts of Coachella—where the artist broke her foot performing in 2015. With lyrics intimate enough to touch each individual heart in the crowd of 100,000, Florence lent her extraordinary vocal talents to Calvin Harris’ “Sweet Nothing,” and her eye for clothes and visual imagery to the band’s 29 music videos. She has also recorded several outstanding covers including “Stand By Me,” “Tiny Dancer,” and Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away.” And finally, and most relevant to the discussion tonight, Florence is the author of this book, “Useless Magic,” which is a 2018 collection of her lyrics, poems, journal entries, and sketches, which will serve as our primary text for this evening. Here ends the introduction.

Florence Welch: (Laughs) Thank you so much for having me. Oh, British people find it really hard to hear the things that they’ve done.

J: I know, you’re so modest. It’s hard to hear all that.

F: Everyone’s cheering and I’m like, “Oh no.” This is my nightmare.

J: Let’s take a deep breath and not talk about your accomplishments any more.

F: Okay, good. That’s done, that’s done. (Laughs)

J: Let’s talk about—you’re on a bit of a hiatus at the present from touring. Can we start there? Talk about how that happened, where that came from.

F: Yeah, of course. Well, I definitely wanted to do the New Yorker, because I love the New Yorker so much. So, this was the last thing that I said yes to. I’m very glad I did, you guys are very loud! Yeah, the last—well, I’ve been touring, oh my gosh, I’ve been touring since I was twenty-one? And it is kind of a cycle of two years of—actually we did not stop touring between Lungs and Ceremonials, because we booked a U2 tour somewhere in the middle when we were supposed to be making the next record, and they were like, “You’ve got to do this. This is pretty big.” Like, oh. Okay. And you know, that was a big thing that helped get us going in America. But I was trying to make Ceremonials as well, so yeah, Lungs and Ceremonials was just sort of one—ugh, I don’t know how long that was. Like five years of touring?

And then I had a break. And it was also kind of a breakdown (laughs). Which is what happens when you don’t stop touring for five years. But actually, I don’t know. I don’t think that was because of the touring, I think it was then when the touring stopped, all the structures that I��d been using...with touring you’re kind of very taken care of, so you can be quite a high functioning fuck-up, which is what I was. Very high functioning, but so self-destructive and with such a lack of any will to take care of myself. People take care of you on tour. Like, if you show up and do the show, people get you dressed, and you ripped all your clothes, and they’ll carry you to a plane. The thing is that I never messed up any shows, which was weird. Like I would mess up hotel rooms, and my whole life, and my relationships, and blah blah blah. But never the shows, so, I don’t know what that was about (laughs).

Then I went back on tour for How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful, after my break slash breakdown, and that was the first tour that I’d done sober and...yeah, it was amazing. The whole process of that record and kind of how heartbroken I was not just over a relationship, but also the breakdown of my relationship with partying and how those things that I thought defined me didn’t work anymore.

And this person really didn’t want to go out with me. Which now, in hindsight, I really don’t blame them for because I don’t know if you want to date someone who shows up at your house with a bottle of vodka shouting, “Why will you not go out with me?” And they’re like, “Because of this. All of this.” And I’m like, “I don’t understand!” Now I kind of really respect them for that. Like, “Oh wow, ‘cause like you had a sense of self, and you had self-respect, I get it!” But yeah, How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful, was a huge healing process, and when I came to the end of it, I did this thing where I dove straight into making High as Hope. I think I’m a person who works in extremes, so again, I didn’t stop working for...I just didn’t stop. I don’t know how to relax. I think that’s probably clear, so I started making High as Hope immediately and that meant that the next tour came around really fast. Although I would say that these shows that I’ve just done have been my favorite I’ve ever done, I loved them.

J: Where were they?

F: Well, all over the world. They were in loads of different places. But it was again, like a year and a half of travel and I’m not a natural traveler. Like I’m not—

J: You don’t like flying I think? F: Oh my god, I’m so scared of flying. It’s the worst! I had hypnotism on it and it wore off (laughs). Nobody told me that hypnotism wears off! Or I just think my anxiety is so powerful that it destroyed the hypnotism. It like, defeated it. I remember reading that the lead singer of The Liars is also really afraid of flying. I think it could be a lead singer thing as well, ‘cause you think that you are the center of the universe and if something really dramatic and catastrophic is going to happen, it should happen to you. So I think there’s a level of ego involved with the fear of flying that I’m hoping in time, I will dismantle.

I find travel in itself, and being away—especially without kind of the crutch of, you know, partying—I get lonely and it’s hard. Although I love the shows and performing, it’s such a big part of me, I...after this tour, I was just worn out by the travel. I was like, I just need to not get on planes for awhile, and I really need to just stay in one place, and try and be like, a human, because although performing runs in my veins, touring is so monotonous, and it starts to feel like you’re losing your mind—and I don’t have much left to lose. So I need it.

J: And there really isn’t any better way to do it probably, right?

F: I keep wondering. I was like, to my manager, “I’m thirty-three, I can’t sleep on a bus anymore!” She’s like, “This is how it is.” You know, I keep trying to think of ways to make it more holistic, but we’ve tried everything and there’s just no getting around the travel because people want to see you, and I’m so lucky to have the fan base in so many places that I do, and I appreciate people and I want to see them. But it means you’re going to have to sleep on a moving vehicle. Which is fucking weird (laughs). When you’re not passed out drunk it’s weird.

J: It’s not like, you curl up in your bunk and the bus takes off and you wake up in the next place the next morning?

F: I don’t know, my brain is so juttery anyway, like sleeping on something that is juttery is a nightmare for me. When I’m trying to sleep on a bus, I’m already someone who tends to get really stuck in their head, and my head is a place that rattles around, so to be in the actual physical representation of that every night, is like a nightmare. I’ve always had a hard time sleeping since I was a kid, and I’m a really light sleeper, always kind of dreaming. I don’t know if I ever get that deep, so yeah. Some things are easier when you can just pass out drunk.

J: Right. We’ll get to that part. Let’s jump back to the beginning of your career. We’re talking about a decade here, so it’s really not a great deal of time but you hit the ground running. I thought we would sort of go through your life by talking about a few songs and your professional life. We’re gonna start with “Dog Days Are Over,” which isn’t the first single I think from the album. I think—

F: “Kiss With a Fist,” yeah.

J: In a way, this is the second single, but perhaps ultimately the bigger hit from the album. I’m not sure, but I feel like this is a song where you first discovered your sound? Or at least for me, I feel like this is where I first heard your sound. Maybe for a lot of us. So I wondered if you could talk about how this song happened, and the lyrics are up here. We can talk about a few of those too. But talk a little, generally, about where this song came from, and how it fit into what work you’d been doing at the time.

F: Ehm, what was I doing? I think I was still at art college, and I—or maybe I’d dropped out?

J: You were at Camberwell College of the Arts, for one year.

F: I wasn’t a very committed art student. I made a lot of installations. I already loved patterns and fabrics and fake flowers and I’d make these big installations, and then kind of sleep in them, and pretend it was an art piece—I was just really hungover. Like, “It’s art! It’s definitely art. Don’t touch it!” I was making flyers for the first Florence and the Machine shows using the photocopier. So I’m sorry for the use of supplies and then not handing anything in.

I’d met Isa of “Isa Machine” fame. She is amazing and we kind of grew up together. She used to babysit my cousin, and then we kind of lost touch. So in South London, for awhile there was a big art collective that squatted the buildings that I lived really near, so when I was a teenager I used to break into all the squat parties, and they would bring all these christmas trees, and everyone would be wearing like, bin bags and crazy outfits, and I was like, “Oh I found them! I found my people!” I was at one of those parties and Isa was there. She was the DJ. She called herself “Laydee Isa,” but it had like seven E’s and seven Z’s. She was like “Oh, I used to babysit your cousin!” And I was like, “Heeey!” I was kind of out of it, I think. She said she had a studio, and that I should come down and make a song.

At the time, there were so many boys in bands. It was around that time of The Libertines, and The White Stripes, and The Strokes—it was a very band oriented time. So I had been writing some songs but because everything was on guitar, and I didn’t know how to play guitar, I just assumed that I would be a singer in someone else’s band, or I’d be a front-woman. I think there was a kind of internalized self-doubt as well. I know I’m not a trained musician. I didn’t have the attention span to sit and learn the piano, or the focus. I was good at singing. I think my attention span doesn’t work...I was like, “I’m already good at this thing.” I could never focus enough to properly learn, which I really regret, actually. I really regret that. So I didn’t have the sort of—I didn’t have the idea that I could make my own band basically. I thought I would be a front-person for someone else’s, but then I started writing songs, and there were so many guitarists about, and that’s how I wrote “Kiss With a Fist.”

They were kind of little gothic fairytales. There’s so much guilt and drama involved—I don’t know what I was. It was kind of like, I think I was already trying to process...I just think from an early age, I felt so much shame, and I don’t really know why. I don’t know where that came from. I think those songs were a way of trying to process what I felt was wrong about me, and through these metaphors—like, this idea that you’d done something terrible, but a bird has seen you do it. So you get the bird, and kill the bird and you eat it so that it can’t tell anybody what you did. I don’t know what the fuck I was doing. But then, you go to sleep, and you’re like, “It’s fine, I got the guy, I’m good.” But when you wake up, you try to speak, and all that comes out of your mouth is the bird singing what you did, and that’s the only thing you can say—which is so dark for a nineteen year old. I think I was just snogging people I wasn’t supposed to or something. But even before, I always felt sort of sensitive as a kid, and I don’t know. I felt like other people had a ticket to kind of get through life that I didn’t know. And how did you get that thing? And everyone seems to have a map, and I don’t. I think these songs were a way of trying to express through these little metaphors how it felt. I was already really obsessed with death in the way that you are as a teenager, and kind of imagining my own funeral all the time. I put these songs with guitars, ‘cause that’s what was around, so that would be like “Birdsong,” in which I wrote with Dev Hynes of Blood Orange. ‘Cause there were so many musicians about—like Kid Harpoon was around, Dev was playing with the Test Icicles at the time, and you could kind of play with anyone. Me and Dev were just sitting in the top room of a pub, and we kind of came up with that song just before we did a show together. That’s kind of how I would make the songs with whoever was around. Isa was sort of the first person who gave me the instrument, who was like, “Why don’t you just try and do something on this?” We called it the “shit keyboard,” it cost like 100 pounds, it was a Yamaha. It burned in a fire!

J: Before or after you used it?

F: After! It burned in a fire. She was the first person who—I think as well because she was another young woman, I think, as a female songwriter...I don’t know if this comes from, like—I had to kind of unlearn deference. I had to really stop deferring. That’s something that’s quite hard, especially when most of the people I was writing with were male. I was instinctively deferring because I was a young woman. I think with Isa, we were kind of the same age, and we kind of bossed each other around! There wasn’t any sort of power imbalance or anything. So she handed me this keyboard and she’s like, “Just do what you want.” The first song that I actually wrote, which you can tell because it’s just an ascending scale, was “Between Two Lungs,” and that was kind of the first thing that sort of felt like it really came truly from me. I was so excited by that, then that the next song we wrote was “Dog Days.” That was like, the first two. They’re not the most complicated chords, but because I never fucking played anything, I thought they were amazing! I was just like, “I’m making this sound? Can you hear this?” Like yeah, it’s fucking piano. It makes that sound for everybody. But because I was the one getting to put them in order and stuff, I just thought like, “This sounds incredible.” She only had like a little...it was in Crystal Palace, which is in South London, we didn’t really have any equipment. We stole drums from someone. The sound of the drums—which I now realize is the same beat as “People Have the Power” (Claps hands to “Dog Days'' percussive rhythm). Which is what we were doing in Patti’s show. We used pens and stuff, and it was kind of, the feeling of that song just came from a lot of enthusiasm, but not really any skill or equipment. So, that’s how it came about.

J: Can I ask you a little bit about the words in the song? “Happiness hit her like a train on a track,” and then later, “happiness hits her like a bullet in the back.” Is it happiness that’s chasing her here? Because it sounds like a celebratory song. Like, the dog days are over and now we’re gonna have some fun! But then it seems like happiness is the thing that’s after her.

F: Well it kind of always was in my mind because I would have such extreme feelings of joy but then I would end up staying out for like three days, so the happiness would always come back down to just terror and panic. I also think that my joy and excitement switch is very close to my panic switch, and I sometimes I don’t know which one is going to go. I think somehow I also equated—I was very mistrustful of happiness, and I think already by the time I was writing the song, I was a very messy person. Not like, untidy, but kind of messy emotionally. I think I’d already done quite a lot of damage to myself and others by that time. We start young in England. By the time I wrote this song, I think I was already, like...yeah, happiness hit her, like a bullet in the back, struck from a great height, by someone who should’ve known better than that. It was sort of like, I didn’t deserve this. You should know better, and I also knew I wanted to be a singer and a performer, and there is this sense that you’ve been struck from a great height, but you are the fucking wrong person (laughs).

J: Huh… okay (laughs). Let’s go from there into writing songs versus writing poetry, because the book is mainly songs, but actually there are poems in the back, and the preface has this interesting line, which I will read. “The act of singing gives the most mundane words and phrases reverence and glory, you can make a shrine out of anything.” I was just wondering, are there certain poems that don’t become songs, and why? Is there something that makes it a song, and something that makes it a poem?

F: I think the first things that I ever started writing when I was a kid was poetry. I mean it wasn’t good, but when I was seven or eight, I was writing poetry. Then I think when I started to think about actually writing my own poetry—like High as Hope is actually an album formed out of poems to begin with. It was a friend of mine called Robert Montgomery who was...he’s a poet, but also a visual artist, and he takes his poems and he turns them into big art pieces with neon lights, and he had said to me, “I think you’re a poet, and I think you should try and write some poetry.” So with that encouragement, I was like, “Okay, okay. I’ll try.” The first thing that I wrote, that wasn’t consciously in mind as a song, but it was a poem, was just a list of things that I thought I couldn’t put into a song.

J: That’s in here! That’s very interesting.

F: Yeah, it’s about getting kicked out of Topshop for drinking Rosé in the changing rooms. I was like, “I don’t know. It doesn’t sing well. So I guess it’s going here.”

J: But you also said in this poem that is not a song, “I’m not sure I can put these things into a song, these muddy trinkets, not beautiful enough. Too bloody and ragged. I always felt the songs should transcend the swamp.” F: Yeah, I think there was a way that I could use metaphor and my imagination to kind of beautify the things that had happened to me, or that I’d done, and in a way kind of own them. Like, when I talk about giving things reverence, I never wanted to actually have the songs written down because I thought that if you saw how sometimes ordinary some of the words are—like the word “kitchen sink” is in “Dog Days,” but when you’re singing something you’re turning it into a hymn almost. You’re giving it a spiritual quality, so I was worried that if the songs were written down, they would maybe lose that. So when I was writing, and I know it’s a song, I feel as if there’s a character or something that’s coming through me that’s bigger than me, and has very big ideas. It’s quite clear on things, kind of understands the bigger questions and I just have to let it happen. So when I was writing poetry, it was a different voice, and it felt like it was almost an even more personal voice because these things were just going to stay on the page. They weren’t going to be viewed with the grandeur of song. They were just going to live there, and who is that person? The drunk Topshop person?

J: You even talked about that—“This new voice, this me voice, is it conversational? Confessional?” Actually there is a poem (New York Poem (for Polly)) I put up here. This is one of the poems from the book. It’s a beautiful poem and it also has your parents and New York in it. So I thought it would give us a jumping off point for your parents. Your mother and father both appear in several of your songs, and have been part of your life. Your mother is a renaissance scholar...

F: Yeah, she is. She’s very smart.

J: And what’s her focus? What’s her specialty?

F: Her focus is the renaissance, above all else. I think even in our childhood her focus was definitely the renaissance (laughs). She’s written four or five books on renaissance studies. It’s funny, she’s always having...she’s always horrified by my exquisitiveness (sic), and how much I love clothes, and bags. But I’m like, “You write books on renaissance shopping, and when we go to museums, I have to stop you from touching things. You love stuff too! Just stuff in the past.” So she’s very interested in what people wore, and textiles, and how people shopped, so she’s read a lot of books about that. And I love shopping too, mom!

J: Didn’t she say to you, when you said you could remember every single outfit you wore, “What a horrible waste of a brain?”

F: (Laughs). I was like, “Oh, you know how I remember things mom? I remember things by what outfit I wore.” She went, “Oh what a waste of your brain.” I was dyslexic as a kid, and she’s worked so hard to get into the upper echelons of academia, and she just keeps getting more and more titles that I can’t even remember now.

J: She’s a provost.

F: Oh, she’s a provost! She’s a provost, yeah, but it just keeps going up. So I don’t know—

J: Dean?

F: No, she’s been that, yup. But I think it’s higher now.

J: So what’s next, chancellor?

F: I think that’s next! But she’s such an impressive person; she would tell me that when I was a baby she was trying to finish papers, or finish books, and she would rest me on a photocopier—it seems like me and my mum both love photocopiers. She just kept working, but I think...none of her children went into academia, and she’s a huge advocate for higher education. That was something that...I was really dyslexic when I was in school, and I couldn’t spell and I struggled at school. I mean, I still don’t think I can do my times tables. Numbers is like a foreign language to me. She’s very staunch; she’s so within herself. She’s incredibly strong, she’s been through so much. I always felt like I was unacademic, emotional, and creative, and sometimes she would look at me as if she had given birth to an octopus. Like, “What is this thing?” I always really looked up to her though, for her drive and her work ethic, and how much she...we’re both very hard workers, I think. I definitely got that from her. And obviously her love of the renaissance has affected me (laughs).

J: And your father comes from, well a journalism family, right? His father was the editor of The Spectator?

F: He was the editor of The Telegraph. I think maybe and The Spectator. I think maybe both, yeah.

J: Okay. And he was a frustrated writer? Or a wishy was-writer, became an advertising guy?

F: Yeah, I think my father is incredibly charming and charismatic and he should have been a performer, really. He is a sort of poet as well, and he was always so imaginative, and would tell me stories when I was a kid that he would then...he was like, “I’m writing a book now!” He moved to Russia when I was fourteen to write a Russian crime novel that my mother tries to pin all my therapy on. Like, I think there’s other stuff. Like not just Dad moving to Russia to write a spy novel, I think there’s other things at play.

J: Did that in fact have a big effect on you?

F: I don’t think it was just that (laughs). I think she’s deflecting slightly. He’s a really creative person and actually he was much more encouraging of me going into the arts. My mother was so desperate for me to go to university. She just didn’t see music. She saw music as a dangerous career, it wasn’t a “forever” career, she was worried I was going to get hurt. She was like, “Get a degree, get some stability, and then do your music thing.” She would, every time I got paid, be like, “It’s not forever money. Put that away.”

But my father, he was always—I mean they’re divorced, so they were like two sides of, you know—they had very different opinions about lots of things. So they didn’t work together. He’s a true bohemian at heart, and he tour-managed us for our whole tour that we did with MGMT around Europe, and England. He did it in his camper-van! MGMT offered us this tour, and it was the first tour we’d ever got. It was a huge break for us actually. We didn’t have any money, and we couldn’t afford a tour bus, so my dad took his sundance camper-van, and we drove all the way around Europe! I mean, MGMT are out there, but I think they thought we were really crazy. So we would just show up there, pots and pans clanking, like, “We’re here!” The first show we did—I mean, I did the show as an early, pre-Lungs era shows where I’d be wearing one of Rob’s t-shirts, drunk and screaming and that was the show. It was excellent (laughs). Then I fell off some speaker stacks. We all had to share a dressing room, as well. That was really cute. Then MGMT came off stage after that show, and they all came off stage, and they’re all like, “Oh my god. The ghost Andy Worhol was in the fucking audience.” Then my dad walked in.

J: Oh, that was your dad? F: It was my dad! Because he had this grey hair, and he kind of dressed as an Andy Worhol, and was right up front. I was like, “Yeah, this is my father, who is managing us.” Then I moved from the tour bus, and then I brought my girlfriend on tour with me. I was like, “Yeah, just come with us!” We got banned from MGMT’s tour bus for being a bad influence (laughs). Which, if you know MGMT, that’s a big achievement.

J: Yeah, that’s a big achievement. Congratulations! Well that gets me into the next subject, which is drinking. Which we both have in common.

F: (Laughs) J: So after the success of Lungs, you were thrown into the world of success and fashion. In particular, you became a darling of fashion. You did the costume ball—anyway, when you read your interviews from that time, you bragfully...in interviews you’re falling apart! You’re drinking at your hotel—you set your hotel room at the Bowery hotel on fire? But the bar bill was more than the hotel damage cost!

F: Yeah, it is (laughs).

J: Anyway, I guess it’s not surprising that with this life came drinking, but it got to a point where it was not manageable.

F: Yeah, I remember waking up and I mean, when you wake up and there’s a huge flame mark on the side of your room, but you’ve been asleep in that room, and you’ve got to figure out where it came from, you’re like, “Was there a fire? And I slept through it? Dope.” Like that is really...I called my publicist at the time, and was like, “Something’s happened!” He was like, “Oh my god, yes, ‘cause there’s a huge bill on my credit card.” I was like, “I think it was the fire.” That was the bar tab. The fire was cheaper than the bar tab.

It was hard. I’ve grown up in South London, and that whole scene is like punk on a pirate ship, it’s sort of pirate folk, and everyone fends for themselves, and the whole gig is like an extended drinking game where you just have to play in the middle. And the game carries on. It was just like an interlude. That is the scene that I grew up in, and I was kind of insecure, I think, about singing pop music.

J: In your family? F: Just in general, and I kind of thought as a way to subvert that, I would just party the hardest. I think as it was a very kind of male dominated scene—like the indie scene that I came up in—it was also a way to kind of outdo everyone. I was very proud of the fact that I could drink as much—and more—than all of the guys. I was the only woman on the first NME tour, and we were opening and they were fucking terrified of me. I think I came into the second show with a black eye, dressed as a bat, jumping off things. I think that’s kind of what I understood, that that was rock and roll, and if you couldn’t go the hardest, you were letting rock and roll down. You were letting these legendary people down.

I was someone who struggled with hangovers, just because I could go...I had insane endurance, but also people would come up to me who I thought were the craziest drinkers and drug-takers I’d ever met, and be like, “Woah. You go harder than anyone I’ve ever met!” I was like, “Oh my god.” But I’ve always had a lot of energy, but I think really why I would stay out for so long is my...you know that sense of shame I spoke about in the beginning? That was there before any of the drinking and the drugs. I already had that. Then to escape that, you know, it would give me an escape from that, but the things I did, or the things I would say, or the way I would treat people just confirmed the way that I felt as a kid. It was just like, you are bad. There is something wrong with you, and then I would carry on trying to escape it in that way, but it would just keep getting worse.

My psyche is pretty fragile; I’m not actually someone who should have a lot of stimulants. They gave me a vitamin shot today, and I’m like, “I’m fucked. I’m high on vitamins! I’m going to have to go to hospital for vitamin overdose!” That’s from a b12 shot. So I don’t know what I thought I was doing when I was partying. Some people are tough, I’m kind of a fragile person. I have a fragile sense of self. The hangovers that I had didn’t seem normal, they were like, “I’m dying. I can’t think, I can’t breathe, like I feel like my skin is—” Maybe it’s ‘cause I drank more than everyone else? I don’t know, but it’s a particular quality that was telling me this does not work for me, but I kept doing it, again and again, and it was always the same feeling. You’ve been doing that in whatever way since you were fourteen, and by the time you get to 27, it’s just—ugh. I didn’t want to feel that way anymore, and it was so repetitive. At some point, the fun bit had gone. As much as I tried to get it back, I just couldn’t. When the fun goes, I’m sorry to tell you if any of you are umming and ahhing, it does not come back. The first year that I stopped, I felt like I’d really lost a really big part of who I was, and how I understood myself. I also felt like I was letting down rock and roll history ‘cause I couldn’t cope. I had to kind of rebuild from scratch a little bit. The thing is that now, I don’t know, it’s almost like the idea of rock and roll that we had...we’ve seen it so many times, it doesn’t end well. I don’t want to be part of that story. J: The 27 year old story.

F: Yeah, I was 27 when I stopped and my mum, literally the speech she gave at my party, where I’d arrived already out of my mind drunk; like I was on the table and she was trying to make a speech. She was like, “Please, just keep her alive. Please.” I laughed about it at the time, but if I think about it now it makes me feel so sad for my mum and how scared she must have been. I feel like at that point there’s...this poem is kind of about that, because I felt like there was a split, there is the person who carried on partying, and didn’t come back. So there’s this ghost version of me. Then there was the person who got to carry on living, and doing the things that I’ve done. It really feels much more rock and roll than anything I ever did when I was drinking. I was doing shows, and connecting with people, and that to me—especially with everything going on in the world—to be conscious and to be present and to really feel what’s going on, even though it’s painful, it feels much more like a truly reborn spirit of rock and roll. It feels like that’s what it should be about right now.

J: The last album was sober, and this song is a remarkable song. It’s maybe not specifically about drinking, but it’s confessional nature I think is what’s a part of whatever transformation you went through. So could you have written [Hunger] as a drinking person? Or do you feel something changed in your songwriting?

F: Oh my god, no. I could have never, ever. I don’t think I could have written this song. I couldn’t have even written this for How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful. In the recording of How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful, I was sober but a lot of the songs weren’t sober because I’d written them when I was drinking, so it was like trying to pull things that were just a big mess. Like, “Okay.” I was in a terrible state. In your first year of your sobriety you’re just insane. So I definitely couldn’t have written it then, but sort of four years down the line, what started to happen was I decided to see underneath—’cause when you’re out there drinking there’s so much surface chaos. You literally can’t see beyond what you did last night as you’re trying to clean that up, and make sure nobody finds out what happened, and who saw? And was there a camera phone? You’re just living in this constant...you can’t ever get any further than the drama that just happened yesterday. So after some time, and some time getting to re-know myself, I started looking at the stuff that was underneath that, that was at the core of it. That’s when I felt able to write this song. I think also I just wasn’t so ashamed of myself at the time. When you’re drinking like I was, you carry around so much shame, and so much of that has lifted that I felt able to say and be honest about things that I just never, ever would have.

When I was really in disordered eating, I would make pacts to myself every night that I will never tell anyone. That was the thing. You can carry on what you’re doing, but you can never tell. Living with that kind of—

J: You kept that promise, because I think when your sister saw this song, she read the first lines, and said she never knew.

F: No, she didn’t. Like, my mum didn’t know. My sister was like, “You better tell mom. You’re putting this out as a big pop song.” I was terrified. I was so scared. I luckily had really good people around. I had my manager, Hannah Giannoulis; she heard this song, and she… I was doing it as a thought experiment. I was never going to release it. I was like, “This is an experiment. This is not for public consumption.” And she heard it, and was like, “This is a really important song.” I was really scared. I was so scared of anger. I’m really bad with anger anyway, but I think it’s because I have so many years of internalized anger against myself for what I was doing, or the way I was behaving that to say it, I expected anger. I expected people to be furious with me for putting something like this out there in a song. I tried to put it off, I pushed back the whole touring schedule. Actually when it was released, people were so kind. I don’t think I gave people enough credit. It was so liberating and it changed me as a performer actually, because once you’ve said your most shameful thing, it’s almost like you’ve got nothing left to lose. So the performances just became so much more open and free, and also when the people who listen to your music accept you at your worst, it is the most beautiful thing. I felt so connected with people on this tour. I’m so grateful to everyone.

#florence welch#florence + the machine#fatm#edited for clarity aka removing florence's adorable rambling that she always does while she collects her thoughts#i love this interview so so much but the quality is pretty poor and therefore pretty inaccessible to non-fluent engl speakers and hoh people#so i put my typing skills to work#if there are any other interviews you'd like transcribed let me know!#this is how i'm putting off writing oof oof oof#also really cant tell if she's saying mom or mum? it sounds like when shes referring to her she says mum#but then if shes speaking to her its mom

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

George Lucas wearing a t-shirt that reads: STAR WARS: a film with comic-book characters, an unbelievable story, no political or social commentary, lousy acting, preposterous dialogue, and a ridiculously simplistic morality. —John Seabrook of The New Yorker

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Practice is the only path to mastery.

| John Seabrook, The Next Word

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maggie Rogers Wants to Keep It Real

by John Seabrook, for The New Yorker.

Not long ago, the folk-pop star was an N.Y.U. student whose homework demo blew Pharrell Williams away. Now she’s selling out Radio City.

Maggie Rogers, the twenty-five-year-old singer-songwriter, producer, and improbable pop star, had a couple of days off in the city the other week, before playing a sold-out show at the Hammerstein Ballroom. “Heard It in a Past Life,” Rogers’s début album, came out in January, and now she’s trying to figure out, as she put it, “How big is too big?” and “What do I really want?” Rogers had just announced two October shows at Radio City Music Hall; the tickets sold out in an hour. That’s pretty big, whether the artist wants it or not.

Keep Reading.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Checklist Of Most Standard Music Genres

What's higher than listening to a moody song on a rainy day, or a tear-inducing pop ballad while you're traveling alone on the subway, throughout every week while you just feel off? The most important surprise is this idea that LGBTQ music or LGBTQ artists didn't all of a sudden grow to be visible with Stonewall, that there were intervals or little pockets throughout the century the place LGBTQ individuals were making music, making data, were out in their own lives, had been performing as out and so they weren't receiving the censorship we'd expect. Clearly I knew of issues like the Weimar period of Berlin cabaret, however I really wasn't conscious of how massive that scene was and to find in just about each major forums.adobe.com metropolis in America at the moment, in every capital of Europe that related scenes additionally existed. I suppose this new sense of freedom that individuals felt instantly after the first World War allowed folks to be a bit more free, to precise themselves more openly and readily. By the point Hjellstrom first picked up the guitar, the boy-band wave had already crested, however Martin and his colleagues, taking Denniz PoP's mantle, had infiltrated all of pop music with their methodical strategy to songwriting and production. When journalist John Seabrook wrote a ebook about this motion, he referred to as it The Tune Machine: within a couple of years of Cheiron's demise, music, the business, had grow to be industrialized. Martin's once-proprietary pop process is now international gospel: Producers take beats and chord progressions, offer them as much as a sequence of "top-line" songwriters reminiscent of Hjellstrom to reward it with melody and hits are made. The GW-eight is packed with an enormous collection of styles representing a broad vary of music genres, from modern rock, pop, dance, jazz and beyond. Along with the wonderful library of up to date sounds and styles, the GW-8 is equipped with ethnic instrument sounds and authentic regional musical types, with particular focus on Latin American genres. Each backing model has 4 intros, four primary patterns, and four ending progressions so that you can craft your individual preparations stay.

The divas of the Nineteen Nineties artists, resembling Madonna, and Mariah Carey offered albums that prolonged their rule of the music charts. The Swedish celebrity Carola Häggkvist continued her rule of European charts. Different tendencies included Teen pop singers similar to Disney Channel star Hilary Duff. Pop punk acts reminiscent of Simple Plan and Fall Out Boy have grow to be increasingly widespread, in addition to pop rock acts such as Ashlee Simpson and Avril Lavigne and emo music akin to Hawthorne Heights, Lostprophets, and Dashboard Confessional. Sarcastically, it could be music critics, in many ways the ideological culprits in Hamilton's story, who've completed the most — after the artists themselves, of course — to unsettle the racial categories which have stunted our understanding of rock historical past. Outlets from The New Yorker to The Fader to MTV Information now often characteristic music writing by young critics of color who strategy pop, rap, and rock with a far sharper, samirabranco543.mywibes.com subtler, and, above all, diverse racial consciousness than the white writers Hamilton cites. In the meantime, a lot of the most inept writing on race and music continues to return from white male critics. Even articulate and aware writers site visitors in previous, reified notions of soul" and funk," the immaterial essences by which they define, and otherize, black music. The tan-brick bunker was, for almost a decade, the finest hit manufacturing unit on the planet. It was founded in the early nineties by Denniz PoP, a remix pioneer with a present for melody who propelled Swedish pop band Ace of Base to global fame, co-producing All That She Desires and The Signal. He cared little for the divide between the membership and the radio, making music that bridged each worlds: beats you may't sit still for and melodies you possibly can't forget. To road-take a look at his prototypes, he'd blast them in empty discotheques within the dead of morning to assess their dance-flooring effectiveness. The approach gave radio pop, lengthy a crucial castaway, an unforgettable immediacy. Interest in music therapy continued to achieve help through the early 1900s resulting in the formation of several quick-lived associations. In 1903, Eva Augusta Vescelius based the Nationwide Society of Musical Therapeutics. In 1926, Isa Maud Ilsen founded the National Association for Music in Hospitals. And in 1941, Harriet Ayer Seymour founded the National Foundation of Music Remedy. Though these organizations contributed the first journals, books, and academic courses on music therapy, they sadly were not able to develop an organized medical occupation. First, the bias of the survey you mention: If pop music is what is being marketed to young girls then that will be the music they report liking. You see, they have been informed that is their music. If the media were to suddenly inform them that most pop artists are lame and that rock was the brand new thing for them, they'd start shopping for rock once more. Young people (female and male) are simply swayed by developments and once they reply to a survey the bulk will report themselves as being hip to the pattern. Lounge music refers to music performed in the lounges and www.magicaudiotools.com bars of hotels and casinos, or at standalone piano bars. Generally, the performers embody a singer and one or two other musicians. The performers play or cowl songs composed by others, especially pop standards, many deriving from the times of Tin Pan Alley. Notionally, a lot lounge music consists of sentimental favorites loved by a lone drinker over a martini, although in observe there may be far more selection. The time period also can seek advice from laid-again electronic music, also named downtempo, because of the fame of lounge music as low-key background music.But even as the city continued to hyperlink its id to music made on guitars, artists tinkered with digital sounds and programmed beats in the local music scene. In 2010, singer Mikky Ekko launched his debut EP Reds. He parlayed its standout observe, a moody ballad with stunning turns called Who Are You, Really?" into mainstream pop success. Inside two years, he'd signal a major label deal, hyperlink up with slicing-edge producers like Clams On line casino, and co-write a song for Rihanna (Keep," a song the pair would later perform as a duet at the Grammys in 2013).

1 note

·

View note

Text

The author of The New Yorker, John Seabrook, came to this conclusion, that it makes no sense to spend money on the automation of rough work, since people can get the minimum wage and the whole process will be cheaper. “It was only those growers who first had access to the capital to buy the technology who could prevail,” Erik Nicholson, the national vice-president of the United Farm Workers, told me. “Those who didn’t could not compete and were run out of business, and their farms were put up for sale, and you had a dramatic consolidation of land in the Midwest.” Maybe other industries will face automation soon, and people will only do heavy manual labor. Robots will be too smart for us.

The author of The New Yorker, John Seabrook, came to this conclusion, that it makes no sense to spend money on the automation of rough work, since people can get the minimum wage and the whole process will be cheaper. “It was only those growers who first had access to the capital to buy the technology who could prevail,” Erik Nicholson, the national vice-president of the United Farm Workers, told me. “Those who didn’t could not compete and were run out of business, and their farms were put up for sale, and you had a dramatic consolidation of land in the Midwest.” Maybe other industries will face automation soon, and people will only do heavy manual labor. Robots will be too smart for us.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Download PDF The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory EBOOK BY John Seabrook

Download Or Read PDF The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory - John Seabrook Free Full Pages Online With Audiobook.

[*] Download PDF Visit Here => https://best.kindledeals.club/0393241920

[*] Read PDF Visit Here => https://best.kindledeals.club/0393241920

New Yorker staff writer John Seabrook tells a fascinating story of creativity and commerce that explains how songs have become so addictive.Over the last two decades a new type of song has emerged. Today’s hits bristle with “hooks,” musical burrs designed to snag your ear every seven seconds. Painstakingly crafted to tweak the brain’s delight in melody, rhythm, and repetition, these songs are industrial-strength products made for malls, casinos, the gym, and the Super Bowl halftime show. The tracks are so catchy, and so potent, that you can’t not listen to them.Traveling from New York to Los Angeles, Stockholm to Korea, John Seabrook visits specialized teams composing songs in digital labs with novel techniques, and he traces the growth of these contagious hits from their origins in early ’90s Sweden to their ubiquity on today’s charts. Featuring the stories of artists like Katy Perry, Britney Spears, and Rihanna, as well as expert songsmiths like Max Martin, Ester Dean, and Dr.

0 notes

Text

Sunday Reading: Creative Innovators

From The New Yorker’s archive: pieces by Rebecca Mead, John Seabrook, Hilton Als, Judith Thurman, and Kelefa Sanneh about artistic visionaries. from Humor, Satire, and Cartoons https://ift.tt/35vlKNw from Blogger https://ift.tt/32plYno

0 notes

Link

Where will predictive text take us?

John Seabrook | The New Yorker | Oct 2019

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

What does it mean that I found the most compelling sentences in John Seabrook’s “The Next Word” to be some of those composed by the GPT-2? And not because they were AI-created but because their language was bold and “original,” writing that one might be tempted, in another context, to describe as “alive” with its insight and craft? The implicit meaning terrifies Seabrook, I believe, who sees in it his potentially imminent obsolescence, though he makes some “herculean” effort to cloak his existential dread as a professional writer in misguided meandering around the “uncanny valley.” What he does not seem to see, beneath the uncanny valley, is a fault line even more threatening, destabilizing, and catastrophic to his cherished egocentric notions of original selfhood and unique personal value as a member of the New Yorker—and The New Yorker—intelligentsia.

“Had my computer become my co-writer?” Seabrook wonders early in his essay about Google’s Smart Compose, whose suggestions he “had been trying to ignore“ for many days. “I’d always finished my thought by typing the sentence to a full stop, as though I were defending humanity’s exclusive right to writing, an ability unique to our species.” What he fails to come to terms with is the way in which the “technology” of his society, his culture, his ontology, his language, his computer—and progressively, the internet, his phone, social media—had always been a co-writer, conditioning the very matrix of knowledge and associations by which he understood how to compose or interpret any text, in just the way that GPT-2 does without the underlying “understanding.” “Perhaps because writing is my vocation, I am inclined to consider my sentences, even in a humble e-mail, in some way a personal expression of my original thought,” Seabrook writes, admitting his categorical error, his failure to interrogate the very notion of an “original thought.” Does he naïvely believe that it “originates” sui generis, out of his brain and mind, disconnected in any way from its surrounding social and technical framework—or does he acknowledge that it “originates” from the cybernetic web, just as the Google and Open AI technology, and their subsequent output does?

“Each human world is a certain configuration of techniques, of culinary, architectural, musical, spiritual, informational, agricultural, erotic, martial, etc., techniques,” write the anonymous authors—or author, or bot, or geist, or specter—of The Invisible Committee in To Our Friends. “And it’s for this reason that there’s no generic human essence: because there are only particular techniques, and because every technique configures a world, materializing in this way a certain relationship with the latter, a certain form of life. So one doesn’t ‘construct’ a form of life; one only incorporates techniques, through example, exercise, or apprenticeship.” The form of life, the social and material technologies and techniques, which Seabrook and all of us have incorporated presuppose the sort of “cybernetic” social control and mediation which can provoke the terror of the “uncanny valley” when we are confronted with them in the form of a new technology of explicit simulation. As The Invisible Committee points out, because we presuppose as a given the preceding technical matrix that produces us and which we reproduce, “our familiar world rarely appears to us as ‘technical’: because the set of artifices that structure it are already part of us. It’s rather those we’re not familiar with that seem to have a strange artificiality.”

And how quickly we are able to incorporate the new technics, techniques, and technologies into our “natural” form of life. “I will gladly let Google predict the fastest route from Brooklyn to Boston,” Seabrook admits, “but if I allowed its algorithms to navigate to the end of my sentences how long would it be before the machine started thinking for me?” As if the machine were not already thinking for him by directing his route, by giving his search results, by updating his social feeds. As if the “machine,” more broadly conceived, were not already thinking for him in designing his routes—his jobs, his real estate sectors, his modes of transport, his urban architectures—even before the advent of Google. Guy Debord and the situationists proposed the psychogeography of la dérive precisely as a practical resistance to the built in logical, systematic, cybernetic programming of our movement through the urban environment. “In reality, cybernetized capitalism does practice an ontology, and hence an anthropology, whose key elements are reserved for its initiates,” The Invisible Committee explains. “The rational Western subject, aspiring to master the world and governable thereby, gives way to the cybernetic conception of a being without an interiority, of a selfless self, an emergent, climatic being, constituted by its exteriority, by its relations. A being which, armed with its Apple Watch, comes to understand itself entirely on the basis of external data, the statistics that each of its behaviors generates. A Quantified Self that is willing to monitor, measure, and desperately optimize every one of its gestures and each of its affects. For the most advanced cybernetics, there’s already no longer man and his environment, but a system-being which is itself part of an ensemble of complex information systems, hubs of autonomic processes—a being that can be better explained by starting from the middle way of Indian Buddhism than from Descartes. ‘For man, being alive means the same thing as participating in a broad global system of communication,’ asserted Wiener in 1948.”

Hence, the dread of the “uncanny valley” and Seabrook’s guarded fear of being replaced by AI machine writers—or worse, “a powerful database of ever more writers, editorial boards, and topics,” as GPT-2 itself writes, in a parody of modern technocapitalist media managerial philosophy. Seabrook’s terror at these ghouls which lack the interiority of a “self” but nevertheless “can do the task flawlessly without understanding anything about the rules of language,” is actually a sublimated fear of something existentially prior. The cherished “personal expression of my original thought” was never thus to begin with. “By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs,” writes Donna Haraway. “The cyborg is our ontology; it gives us our politics. The cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centers structuring any possibility of historical transformation.” As Haraway explains, embracing this framework as a possibility for feminist, liberationist dialectical reconstruction, no clear lines of demarcation of the sort Seabrook seeks can be drawn between the “uncanny” new technologies of AI and our already existing cybernetic existence, nor between “science” and “magic”:

A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world-changing fiction. The international women’s movements have constructed “women’s experience,” as well as uncovered or discovered this crucial collective object. This experience is a fiction and fact of the most crucial, political kind. Liberation rests on the construction of the consciousness, the imaginative apprehension, of oppression, and so of possibility. The cyborg is a matter of fiction and lived experience that changes what counts as women’s experience in the late twentieth century. This is a struggle over life and death, but the boundary between science fiction and social reality is an optical illusion.

Late in his essay, Seabrook describes in bodily, visceral terms his intellectual confrontation with what the mirror of AI reflects back, as “initial excitement had curdled into queasiness.” But he seems unable to see his own reflection through the optical illusion of this science fiction made social reality. “It hurt to see the rules of grammar and usage, which I have lived my writing life by, mastered by an idiot savant that used math for words,” Seabrook confesses. “It was sickening to see how the slithering machine intelligence, with its ability to take on the color of the prompt’s prose, slipped into some of my favorite paragraphs, impersonating their voices but without their souls.” He cannot acknowledge the radical nature of his own persona’s “impersonation,” nor confront the implications it might have on the state of his “soul.” “A long time ago, the whole world could have said that it lived in a golden age of machines that created wealth and kept peace,” writes GPT-2. “But then the world was bound to pass from the golden age to the gilded age, to the world of machine superpowers and capitalism, to the one of savage inequality and corporatism. The more machines rely on language, the more power they have to distort the discourse, and the more that ordinary people are at risk of being put in a dehumanized social category.” As we are all cyborgs, and the line between “human” and “machine” is an optical illusion, one can easily swap these terms in the preceding quotation. Just hit Command-F, and let the computer do the work of finding the phrase for you.

0 notes

Text

How Blackpink, Red Velvet, And More Are Redefining Womanhood In K-pop

By T.K. Park and Youngdae Kim

When you think of K-pop, the seven young men of BTS most likely come to mind, but the women artists are enjoying a heyday of their own. Red Velvet recently hit seven cities on their first North American tour, while Blackpink took Coachella by storm, mingling backstage with their fans Ariana Grande and Will Smith. Wonder Girls’ Sunmi and Girls’ Generation’s Tiffany have broken free from the girl groups that made them and are now headlining their own U.S. tours. And these women are doing it with confidence, strength, and flair, completely unconcerned with the male gaze — or with anyone else’s gaze for that matter.

The English-language discourse about K-pop idols, and in particular female idols, is still shaped in large part by the 2012 New Yorker article by John Seabrook titled “Factory Girls.” Published in the same year that “Gangnam Style” became a global phenomenon, Seabrook’s article painted a picture of women K-pop idols as carefully-crafted objects, using Girls’ Generation — the most successful K-pop girl group until that point — as the primary focus. It was a familiar story to anyone who had been following K-pop. The artists are recruited in their adolescence, put through a rigorous training regimen, and undergo plastic surgery so that they can execute the vision of their producer: an image of beautiful yet demure Korean women, in contrast to the male idols who more freely deviate from the conventional gender norms.

Getty Images

Girls’ Generation perform at the KBS Korea-China Music Festival in August 2012

This caricature won a great deal of purchase, in part because it contained a modicum of truth, and also because it fit female K-pop stars into the prevailing U.S. preconception about Asians and women: Asians are supposed to be mechanical, women are meant to be objectified, and therefore it made sense that Asian women pop stars were mechanically objectified.

But even in 2012, this description was not entirely on the mark. It is true enough to say a persistent strain in K-pop’s girl groups involves turning women into an object of male desire — as is the case with female pop artists anywhere. But it is a mistake to think the women of K-pop solely traffick in marketing themselves as manufactured objects of that desire. In truth, even the most “manufactured” K-pop girl groups display a great deal of agency, and their profile evolves as their careers progress.

1990s-2000s: The Dueling Sides of Femininity

Fin.K.L’s “To My Boyfriend,” released in 1998

Objectification and agency formed the current and countercurrent as long as girl groups have existed in the modern K-pop idol scene. For the first generation of K-pop girl groups of the late 1990s, this was partly a function of their reference materials: The girl groups that emulated U.S. artists leaned more toward displaying confidence and independence, while groups that emulated Japanese acts hewed closer to the conventional image of demure Asian women. The latter was the mainstream at first. Influenced by Japanese groups like SPEED, the leading first generation K-pop girl groups, such as S.E.S. and Fin.K.L, established the course that many came to regard as the standard K-pop path for women as an object of male desire: a gaggle of cute girls growing into adorable young women over time. Meanwhile, groups like Baby V.O.X. and Diva, which emulated the hip-hop-based music and images of TLC, formed the countercurrent of women artists with confident and spunky attitudes.

Girls’ Generation’s “Gee,” released in 2009

The first generation K-pop girl groups’ popularity entered a fallow period around 2003, when idol groups overall lost ground to R&B acts. Then in 2007 Wonder Girls, Kara, and Girls’ Generation debuted, forming the second generation of K-pop girl groups. It was also this generation that perfected the strategy of turning female artists into a carefully-curated product, cultivating what came to be known as “uncle fans” — middle-aged men with disposable income and dubious motives. These are the “factory girls” that Seabrook encountered, as the second-generation girl groups were the first ones that enjoyed meaningful popularity in the U.S. market by appearing on Billboard charts, performing on late night talk shows, and going on nationwide tours.

But not even Girls’ Generation, the archetype of a female K-pop idol group, was content only to project an image of demure young women. From the beginning, Girls’ Generation had a streak of strength and independence that was overshadowed during the peak of their careers but re-discovered later. For example, the lyrics of 2007’s “Into the New World,” the group’s first hit single, showed unflinching resolve: “Don’t wait for any special miracle / The rough road ahead of us is / The unknown future and a wall / We won’t change, we won’t give up.” These words re-emerged as a slogan for the 2016-17 Candlelight Protests that led to the impeachment and removal of then-president Park Geun-hye.

Even in this “peak objectification” period, there were plenty of female K-pop idols that emphasized confidence and agency. 2NE1, debuting in 2009, is a notable example. 2NE1 inherited the spunky image of Baby V.O.X. and Diva, and blended the contemporary hip-hop aesthetics favored by their production company YG Entertainment. The result is a group that consciously rejected the conventional cute-sexy axis in favor of being swag-based alpha girls. Further, the female idols of the first generation would evolve toward being more dominant and in-charge as their careers progressed. Lee Hyo-ri, who began her solo career in 2003 after a successful run in Fin.K.L, did more than merely project an image. By actively participating in the creation of her own music, she was claiming true agency over every aspect of her artistry. This pattern would repeat with other female idols who advanced their careers, like BoA, Tiffany, and Sunmi.

Gain’s “Bloom,” released in 2012

The later part of this period was also characterized by an aggressive marketing of sexuality. Three notable examples — HyunA, Gain, and IU — demonstrate three distinct ways in which women of K-pop sublimated their sexuality into artistry. Provocateur HyunA is the grown-up version of her former group Wonder Girls, maintaining the bright and cheerful atmospherics but with more skin and suggestive dance moves. Gain, on the other hand, does not suggest — she affirmatively expresses her sexuality, making her presentation not about the gaze that she would attract, but about the desire she feels. This is especially evident in the music video of her 2012 single “Bloom” with its jaw-dropping depiction of self-pleasure, making Gain more popular among women than men. IU is arguably the most cerebral of the three, as she relishes the subversive force created by the knowing look behind her girlish face. Like Madonna, IU leverages her feminine charm as a means of control. IU’s seemingly more traditional sexuality is in fact a highly-cultivated device, inducing submission from men to whom she appears to be submissive.

2010s-Present: Redefining Womanhood

The women of K-pop face a unique challenge compared to their male counterparts. Unlike K-pop boy bands whose fandom is mostly women, K-pop girl groups are beloved by men and women alike, with each artist having a different mixture of male and female fans. In the past few years, the women of K-pop became more attuned than ever to the complex gender dynamics of their fans, who are living in the age of #MeToo-era feminism and fluid gender identity. Of course, the more “conventional” K-pop girl groups, such as Twice or IZ*One, continue to remain hugely popular. Yet equally popular are groups like MAMAMOO, who flaunt their sexuality and do it on their own terms, not to meet anyone else’s expectations.

Blackpink’s “DDU-DU DDU-DU,” released in 2018

Blackpink arguably is the leader of the latter group. Fresh from their Coachella debut, Blackpink is this generation’s 2NE1, combining their predecessor’s alpha-girl swag with model-like looks. With more flash, more glam, and more swag, the four women of Blackpink — Jisoo, Jennie, Rosé, and Lisa — dominate the stage like four Beyoncés, totally devoid of any aegyo (cute expressions) that has long characterized K-pop girl groups.

Red Velvet, on the other hand, continues SM Entertainment’s girl-group tradition of cute girls growing into cheery young women. Yet like their predecessor Girls’ Generation, Red Velvet maintains a streak of independence that rejects being mere objects of desire (for example in “Bad Boy,” in which they view the men who refuse to bow to them as a challenge worth conquering.) Further, Red Velvet wears its feminism proudly: The group’s leader Irene recently made waves by saying at a fan meeting that she read Kim Ji-young, Born 1982, Cho Nam-ju’s best-selling feminist novel. Irene’s statement was met with howls of sexist outrage. But Irene and Red Velvet persisted, never apologizing for her belief in gender equality.

LOONA’s “Butterfly,” released in 2019

LOONA presents still another possibility, attracting LGBT fandom with gender fluidity. With its “girl of the month” concept — introducing a new member every month for a calendar year — LOONA initially appeared to be on a similar track as Red Velvet. Yet with songs and music videos that appealed to the aesthetics of same-sex attraction, intricate choreography that puts them on-par with their male counterparts, and an inclusive concept that allows them to represent every girl, LOONA is cultivating an entirely new kind of diverse fanbase.

Where will the female K-pop idols go next? Of course, the previous generation will continue the process of maturing into their own artistry. Taeyeon of Girls’ Generation, for example, is rapidly emerging as a major figure in her own right. But the latest development is suggesting that the women of K-pop are on their way to overcoming the final frontier of idol music: gaining agency over the presentation of their looks, image, and music. With new girl groups such as (G)I-dle featuring women artists who are producing their own music and narrative, that reality doesn’t seem so unlikely. Far from being “factory girls,” the women of K-pop are increasingly charting their own course with greater independence than ever.

The post How Blackpink, Red Velvet, And More Are Redefining Womanhood In K-pop appeared first on Gyrlversion.

from WordPress http://www.gyrlversion.net/how-blackpink-red-velvet-and-more-are-redefining-womanhood-in-k-pop/

0 notes

Text

The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory - John Seabrook | Music |966999238

The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory John Seabrook Genre: Music Price: $12.99 Publish Date: October 5, 2015 There's a reason hit songs offer guilty pleasure—they're designed that way. Over the last two decades a new type of hit song has emerged, one that is almost inescapably catchy. Pop songs have always had a "hook," but today’s songs bristle with them: a hook every seven seconds is the rule. Painstakingly crafted to tweak the brain's delight in melody, rhythm, and repetition, these songs are highly processed products. Like snack-food engineers, modern songwriters have discovered the musical "bliss point." And just like junk food, the bliss point leaves you wanting more. In The Song Machine, longtime New Yorker staff writer John Seabrook tells the story of the massive cultural upheaval that produced these new, super-strength hits. Seabrook takes us into a strange and surprising world, full of unexpected and vivid characters, as he traces the growth of this new approach to hit-making from its obscure origins in early 1990s Sweden to its dominance of today's Billboard charts. Journeying from New York to Los Angeles, Stockholm to Korea, Seabrook visits specialized teams composing songs in digital labs with new "track-and-hook" techniques. The stories of artists like Katy Perry, Britney Spears, and Rihanna, as well as expert songsmiths like Max Martin, Stargate, Ester Dean, and Dr. Luke, The Song Machine shows what life is like in an industry that has been catastrophically disrupted—spurring innovation, competition, intense greed, and seductive new products. Going beyond music to discuss money, business, marketing, and technology, The Song Machine explores what the new hits may be doing to our brains and listening habits, especially as services like Spotify and Apple Music use streaming data to gather music into new genres invented by algorithms based on listener behavior. Fascinating, revelatory, and original, The Song Machine will change the way you listen to music.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Will Computer-generated Writing Replace the Human Kind?

Will Computer-generated Writing Replace the Human Kind?

Free on KU

You may recall my sci-fi romance, A Heaven For Toasters, taking place some 100 years in the future. Leo, the android protagonist, exhibits some distinctly human characteristics—including the ability to feel human emotions. But could Leo become a writer or poet?

The Economist recently shared an article cheekily called Don’t Fear the Writernator– a reference to literature’s…

View On WordPress

#Economist#fake news#GPT-2#John Seabrook#Johnson#Santa Barbara#The New Yorker#University of California#Writernator

0 notes