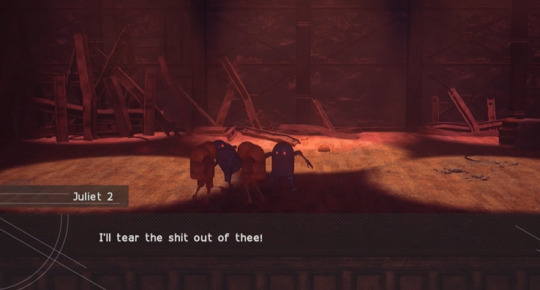

#but the romeos and juliets section made me scream out loud. so you see its not always bad to be vulgar you just gotta

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

okay sometimes automata's writing feels a bit too ''trying hard to be shocking/vulgar'' like making the little sister machine press 9S about how children are born and it can be a bit. eyerolling. but sometimes it can be really, really funny

#when games have the rating to swear a lot and be vulgar theres like TO ME a still accpetable amount before it#just feels like when a child learns a new swear word for the first time and keeps repeating it knowing its bad and they shouldnt say it#the robots faking having sex was just teetering on the line but the insistence of asking where children come felt forced#but the romeos and juliets section made me scream out loud. so you see its not always bad to be vulgar you just gotta#execute it a certain way. earn your right to make sex jokes or swear a ton#also jackass was another good example of a good vulgar joke. set it up and then let it linger on its own

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 2: ANGRY!

I’m mad! You’re mad! These composers are mad!!

...maybe?

I mean, there definitely is fire in each of these compositions, but it’s hard to really prescribe and attach an emotion onto a piece of music. Unless a composer tells us “Yeah, I’m UPSET” in relation to one of their pieces, we, as listeners, don’t really have the authority to say a composer was definitively “mad,” or a composition is “angry.”

We can, however, describe how a composition makes us feel. These compositions make me feel like the composers are angry. Sometimes, I think they’re absolutely livid. But were they really actually mad?

...maybe?

Shostakovich composing his 10th Symphony, 1953 (colorized)

Who knows? Maybe you don’t feel incensed at all upon listening to these songs. Maybe you think I just picked loud percussive dissonant songs and none of them made you feel like the composers wanted to punch a hole in a wall in the middle of composition. Well, that’s truly the beauty of music, especially classical music; we all can make our own interpretations of music, and we can all get emotional feelings from music, but no interpretation is actually wrong. Everybody is right. Especially me. I’m super right on this one.

I THINK THESE COMPOSERS ARE ANGRY!

1. Planets Suite (I. Mars, the Bringer of War) by Gustav Holst (Performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra)

Ok, so I started the playlist with a really cliched piece. Sue me. But I think this movement exemplifies, in my mind, what angry music should sound like. It’s brutal, it’s dark, and sometimes it’s angry even in a quiet intensity. I think there’s a good reason this movement is as ubiquitous as it is; it’s just really really angry.

2. Symphonic Metamorphosis after Themes by Carl Maria von Weber (Mov. 1, Allegro) by Paul Hindemith (Performed by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra)

One of the harder things about developing this playlist was setting a barometer for what I felt qualified a piece or movement as being “angry” or “mad.” This movement was close to being replaced by either the second (”Turandot”) or the fourth (”March”) movement of the same piece, but I really love the dark and stormy beginning and ending to this particular movement. If you ever get the chance to listen to this Turandot and Weber’s Turandot, do so; the changes Hindemith made are pretty nifty. Also, the UMD Wind Ensemble is performing this piece on Friday, October 13 (!).

3. String Quartet No. 3 in F Major (Mov. 3, Allegro Non Troppo: Forces of War Unleashed) by Dmitri Shostakovich (Performed by the Taneyev Quartet)

And so, we have arrived in the Shostakovich block of this playlist. As you’ll come to learn (I guess right now), Shostakovich is my favorite composer. I’m not going to give away Shostakovich’s life story (that might be for another week!), but at the very least I can tell you the man went through quite a lot in his life, and he seemed to express the hardships and troubles he faced daily in his music. Shostakovich wrote this quartet in the midst of the constant repression of his works by the Soviet government, and this movement seems to reflect some of the anger he must have felt in having his art censored and repressed by his own government. Side note: there’s a really funky viola part in this movement!

Among the first results when you search Google Images for “funky viola.” I can’t say I’m surprised. What I can say is that I wish I could have this much funk.

4. String Quartet No. 8 in C Minor (Mov. 2, Allegro) by Dmitri Shostakovich (Performed by the Brodsky Quartet)

Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet is one of my two favorite pieces of music, period. Every single note, to me, speaks to Shostakovich’s personal tumult and his own conception of immortality through music.

The most common musical motif in this piece is the DSCH motif, or the notes D natural, E flat (”Es” in German musical notation), C natural, and B natural (”H”) in sequence. The quartet starts with this motif, and many of the movement’s themes are based around this motif. Shostakovich used this specific sequence of notes because it spelled out his name: Dmitri Schostakowitsch.

It is largely unclear the actual specific mindset Shostakovich was in when writing this quartet, but we do know that he wrote it shortly after facing severe muscle weakness and very reluctantly joining the Communist Party. Some argue that he was suicidal writing this piece; that much like Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet was a suicide note. In this line of thinking, the quartet is autobiographical, and the constant repetition of DSCH is representative of Shostakovich screaming his name into eternity, hoping he will be remembered after he passes (this claim is somewhat contentious; our source on the matter is at times unreliable, and in this instance, refuted by Maxim, Dmitri’s son). Other analyses point to this quartet being anti-fascist, while still others see the quartet as a reaction to the destruction of Dresden, the city in which he wrote this quartet.

No matter the interpretation of the context, it seems clear to me that each movement encapsulates a different emotion; the second movement is the pure essence of anger towards a hopeless situation.

5. Symphony No. 10 in E Minor (Mov. 2, Allegro) by Dmitri Shostakovich (Performed by the Orchestra of the Moscow Philharmonic Society)

Otherwise known as the “Stalin” movement by our favorite somewhat disreputable source, Volkov. It’s easy to imagine that this movement represents Stalin, with its harsh brass lines, intense string melodies, and powerful percussive rhythms, so it’s not a surprise that a link between this movement and the Soviet leader has formed in the common conscience. Whatever the topic actually is, Shostakovich is absolutely livid about it. Get out of his way.

6. Peer Gynt Suite No. 1 (Mov. 4: In the Hall of the Mountain King) by Edvard Grieg (Performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra)

Alright, alright. This one is pretty cliched, too. You could even argue that the first half of the piece is more spooky and creepy than angry, and thus makes this movement ineligible for this playlist. But I think the second half is fierce and and angry enough, and plus this is a really convenient way for me to plug the UMD Repertoire Orchestra concert on the 18th (featuring this suite, Liberty Fanfare, and Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony!). It’s stretching the limits of “angry,” I guess, but it’s worth it for a little bit of advertising. (Plus I think it’s pretty angry.) I’ll make up for it with the rest of the playlist, I promise.

But as long as I like it, that’s what counts, right? Right?

7. Concerto Grosso No. 1 (Movs. 4 and 5: Cadenza and Rondo) by Alfred Schnittke (Performed by the New Stockholm Chamber Orchestra)

This piece took a while to grow on me, but it’s become on of my favorites in the string orchestra (plus harpsichord /prepared piano) canon. At times, the piece feels like a parody of baroque music, and other times it feels like an homage to it. The Rondo movement in particular is one of my favorites because it has the “Grandma Schnittke” character (attested to by the composer himself) playing a tango on the harpsichord. And it sounds just like you would imagine a tango being played on a harpsichord would sound: amazing.

8. Romeo and Juliet Suite: Montagues and Capulets by Sergei Prokofiev (Performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra)

Much of this movement of the suite is from the section of the ballet called The Dance of the Knights, but I prefer the suite version because of its unique opening. I’ve always felt like this piece feels like a march to the gulag or some other sinister or otherwise life-ending excursion. The theme of this movement in my mind does not match up well with my (very basic) conception of ballet, but I saw a recording of a performance and it actually looked pretty cool. Hey, did you know that the UMD Symphony Orchestra is (maybe? probably?) playing this movement and others from the various Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet Suites on Friday, October 20th???

9. Alexander Nevsky (Mov. 5: Battle on the Ice) by Sergei Prokofiev (Performed by the Russian State Symphony Orchestra)

To close out this playlist, we have an adaptation of Prokofiev’s score for Sergei Eisenstein’s first movie with sound, Alexander Nevsky. Nevsky was a Grand Prince of Kiev in medieval Rus, and this particular scene in this “biography” details the battle between Nevsky’s forces and the Teutonic Knights of Livonia on a frozen lake on the border of modern Estonia and Russia. It’s an interesting watch, and the music written by Prokofiev could not better express the danger of battle, but also the calm uncertainty of the battle’s aftermath. Hopefully, the ending of this piece was able to resolve any pent-up anger from the rest of the playlist.

Whew! What a long post! I always tend to ramble when Shostakovich is on the mind. Thanks for sticking with me this far, and thanks for listening to The ƒ-hole on WMUC Digital. Check out the three performances I mentioned in this post, and don’t forget to tune in next week when I will play John Williams’ March from 1941!

0 notes