#but the only one to join him was gauguin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“if i am worth anything later, I am worth something now. for wheat is wheat, even if people think it is grass in the beginning”

is such a beautiful line from van gogh.

#i think the story of van gogh is nice even if its tragic#he believed in this artist utopia where artists would work together#but the only one to join him was gauguin#who ridiculed his work so hard ppl attributed it to van goghs later meltdowns#so it brings me a lot of joy when i see their works next to each others now#but while everyone fights for a photo with a van gogh painting#few seem to care for gaugin’s work#maybe thats not the moral to take away from it#it just feels poetic

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

OC Brain Rot Post #1: Thea and Abby and the Rivals Fight at the Mansion

OC Brain Rot (originally based on this post) is where I basically ramble some about my OCs and what they're up to currently outside of my writings and arts. Basically, these posts are, in essence, brain dumps. Sometimes there might only be a couple sentences and half-formed ideas, others might go into meta involving my ocs and whichever game universe they are apart of.

Most post will be based around my otome OCs but some original ones might slip in once in a while! You just never know where my brain might take me.

I'll also make a big, huge note here that these posts won't be spoiler-free! At the beginning of each post, I'll try and make note of which game and OCs I'll be talking about. Spoiler parts will be under the cut.

For this post, there will be Spoilers below about the Interlude route of Ikemen Vampire, right around Chapters 10 and 11.

Thea and Abby will feature in this rot. Normally, they are two characters that have their own universes. However, I also fall inevitably into joining their universes together just so I can have them both interacting with the boys and being friends (Thea is quite protective of the shy and timid Abby), so I'll also include some thoughts about both of them together in this part of the Interlude route.

Here we go, onto the brain rotting!

-----

For Context: The Interlude Route in Ikemen Vampire is a transition arc between the first and second acts, right before the act 2 for the suitors are released and two new characters are introduced. MC is stuck in the past because Comte's magical time door is broke and going home is likely an impossibility at this point, unless you want to be lost in the time soup for all eternity. So now, MC is trying to make the best of the change in her plans.

Vlad, still bent on not letting the vision he saw in the future come to pass, revives the rivals to our suitors and they have been terrorizing everyone the past few chapters. Where I'm at currently, Vlad has met with Comte and Leonardo and they tried to talk things out, purebloods to pureblood, but Vlad still refuses to stop his mission and the three part ways.

He then sends the ones he's revived to the mansion in an all out attack. Napoleon and Jean take the most brunt in fighting Wellington and Gilles with Leonardo and Comte assisting them. Dazai and Sebastian were guarding the door while the other non-fighters (Mozart and Isaac) were in the piano room. Theo had gone on his own to face off against Gauguin to get revenge with Arthur following him to make sure he didn't do anything stupid, such as going through with the revenge quest he was on.

This is initially where the girls start off in. Vincent is also in the piano room but soon goes out on his own because he also figures that Theo was about to do something stupid and while I initially thought it was dumb of him because he left the non-fighters defenseless (his little info blerb he's the strongest of the non-purebloods and I had many instances of 'why you do that, something bad gonna happen to the non-fighters! Vincent, my love!') but he didn't want for Theo to do his stupid thing, so he goes to Theo and it's sweet (me still thinking it was dumb but whatever, narrative gonna do what it wants).

For Thea, she goes with Vincent after Theo. No risking yourself for your brother nonsense! She cares too much about Theo too, she's gonna stop him. And she knows a little bit about fighting (as stated in this power-scaling reblog I did), so she'll be mostly okay. Theo pulls her to him as he flips the pool table in the game room and all four of them are dodging bullets, currently.

For Abby, she stays with Mozart and Isaac in the piano room, scared as this is some terrifying shit going on! When Vincent said he was leaving for Theo, Abby was very, very scared, numerous things running through her head, all of them not good. Worried for everyone outside fighting currently, for Sebastian and Dazai guarding the door, for Theo and Arthur out on their own, and now Vincent going on his own to find Theo. She wishes she could curl up in a corner somewhere, close her eyes and cover her ears until all of this was over, but she can't, not when all of her friends are fighting right now.

Before Vincent leaves, she does tug on his sleeve, wanting to ask him to stay. She knows how strong he is and wants him to stay with them, but seeing his eyes, how worried yet determined how he is. He was set on finding Theo.

So, in the face of that, all she could do was let go of his sleeve and say "Be careful."

Vincent smiles and gently pats her shoulder, promising to come back soon, with Theo in tow.

Once he's gone, however, Salieri comes after Mozart with a knife and we're back in terror time again. Isaac stays the closest to her, they're both terrified! Mozart shielding both of them. He manages to break the mind control over him with standing in front of the piano, reminding him that he had admired his music in their first lives, what has happened to you to attack another music lover? Things seem to simmer down in the music room because of that.

In the combined universe of both girls, it's relatively the same, Vincent still goes off to find Theo, but Thea goes with him, determined to find Theo and to help him or stop him from doing the stupid thing. Abby still tugs on Vincent's sleeve, still sacred but ultimately lets him and Thea go. They both cared a lot about the younger van Gogh, so who was she to stop them just because she's scared?

And... this is as far as I've gotten with this brain rot. Just a fun little brain exercise to put the girls in the goings on with what I'm playing currently. Hope to be able to share some more brain rots with you guys soon!

#krys talks#krys's adventures in fanfiction#krys's babies#dorothea reid (oc)#abigail clarke (oc)#ikemen vampire#ikevamp spoilers#They also went with Arthur and company when he was going to face against Worth#bc Thea didn't want her boy doing something stupid then either with Abby tagging along bc she saw Arthur from the window and got worried#their boys sure are stupid sometimes#all the boys can be stupid sometimes#that's why they love them of course#their silly vampire boys

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art, an amazing way of expressing yourself. From the secrets hidden in a color scheme to a saddening message from a joyful and radiant painting. Art comes in many different forms and I will be talking about Vincent Van Gogh

A quote I admire (from a series, Doctor Who)

"To me, Van Gogh is the finest painter of them all. Certainly, the most popular great painter of all time, the most beloved. His command of colour, the most magnificent. He transformed the pain of his tormented life into ecstatic beauty. Pain is easy to portray, but to use your passion and pain to portray the ecstasy an joy and magnificence of our world... no one had ever done it before. Perhaps no one will ever again. To my mind, that strange, wild man, who roamed the fields of Provence was not only the world's greatest artist, but also one of the greatest men who have ever lived."

Vincent Van Gogh was born in 1853 in the country of Netherlands, he was the son of a pastor, he grew in a religous and cultured atmosphere, Vincent was emotionally unstable, he lacked in self-confidence and had an identity crisis that gave him a hard time following his path in life. He belived that his true calling was to preach about the gospel.

But it took years for him to discover is calling as an artist. In 1860-1880, when he decided to become an artist Van Gogh had experienced two unsuitable and unhappy romances and had worked unsucessfullyas a clerk in a bookstore, an art salesman, and a preacher in the Barinage (a mining district in Belgium) where he was dismissed for overzealousness

He remained in Belgium to study art, determined to give happiness by creating beauty. The works of his early Dutch period are somber-toned, sharply lit, genre paintings of which the most famous is "The Potato Eaters" (1885) . In that year van Gogh went to Antwerp where he discovered the works of Rubens and purchased many Japanese prints.

In 1886, he went to Paris to join his brother Théo, the manager of Goupil's gallery. In Paris, van Gogh studied with Cormon, inevitably met Pissarro, Monet, and Gauguin. Having met the new Impressionist painters, he tried to imitate their techniques; he began to lighten his very dark palette and to paint in the short brush strokes of the Impressionists’ style. Unable to successfully copy the style, he developed his own more bold and unconventional style. In 1888, Van Gogh decided to go south to Arles where he hoped his friends would join him and help found a school of art. At The Yellow House, van Gogh hoped like-minded artists could create together. Gauguin did join him but with disastrous results. Van Gogh’s nervous temperament made him a difficult companion and night-long discussions combined with painting all day undermined his health. Near the end of 1888, an incident led Gauguin to ultimately leave Arles. Van Gogh pursued him with an open razor, was stopped by Gauguin, but ended up cutting a portion of his own ear lobe off. Van Gogh then began to alternate between fits of madness and lucidity and was sent to the asylum in Saint-Remy for treatment.

In May of 1890, after a couple of years at the asylum, he seemed much better and went to live in Auvers-sur-Oise under the watchful eye of Dr. Gachet. Two months later, he died from what is believed to have been a self-inflicted gunshot wound "for the good of all." During his brief career, he did not experience much success, he sold only one painting, lived in poverty, malnourished and overworked. The money he had was supplied by his brother, Theo, and was used primarily for art supplies, coffee and cigarettes.

Van Gogh's finest works were produced in less than three years in a technique that grew more and more impassioned in brush stroke, in symbolic and intense color, in surface tension, and in the movement and vibration of form and line. Van Gogh's inimitable fusion of form and content is powerful; dramatic, lyrically rhythmic, imaginative, and emotional, for the artist was completely absorbed in the effort to explain either his struggle against madness or his comprehension of the spiritual essence of man and nature.

In spite of his lack of success during his lifetime, van Gogh’s legacy lives on having left a lasting impact on the world of art. Van Gogh is now viewed as one of the most influential artists having helped lay the foundations of modern art.

https://www.vangoghgallery.com/misc/biography.html

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

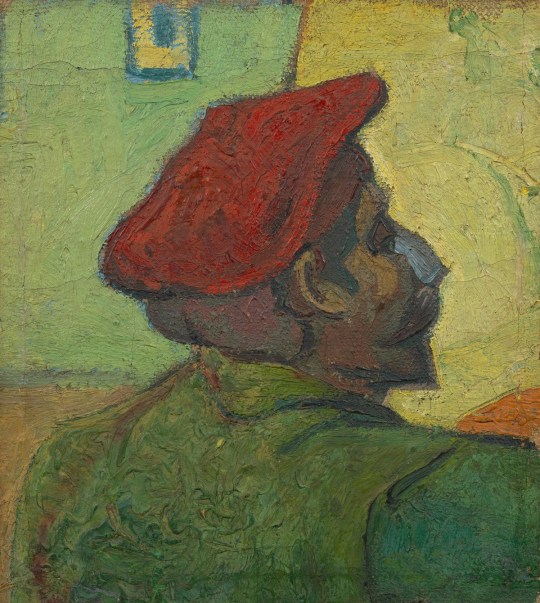

The Painter of Sunflowers and The Man in a Red Beret

— The Painter of Sunflowers (Portrait of Vincent van Gogh), by Paul Gauguin (1888).

— Paul Gauguin (Man in a Red Beret), by Vincent van Gogh (1888).

–

It’s like trying to compare Gauguin and Van Gogh. They were friends, as well.

— John Lennon talks with Robert Hilburn from The LA Times (10 October 1980).

–

Certain relationships are charged with an intensity of feeling that incinerates the walls we habitually erect between platonic friendship, romantic attraction, and intellectual-creative infatuation. One of the most dramatic of those superfriendships unfolded between the artists Paul Gauguin (June 7, 1848–May 8, 1903) and Vincent van Gogh (March 30, 1853–July 29, 1890), whose relationship was animated by an acuity of emotion so lacerating that it led to the famous and infamously mythologized incident in which Van Gogh cut off his own ear — an incident that marks the extreme end of what Sir Thomas Browne contemplated, two centuries earlier, as the divine heartbreak of romantic friendship.

— ‘Gauguin’s Stirring First-Hand Account of What Actually Happened the Night Van Gogh Cut off His Own Ear’ by Maria Popova for Brain Pickings.

–

Imagine all the people living life in peace

Arles [town in the South of France where van Gogh had moved to on February 1988]; Wednesday, 3 October 1888

My dear Gauguin,

[…]

I must tell you that even while working I never cease to think about this enterprise of setting up a studio with yourself and me as permanent residents, but which we’d both wish to make into a shelter and a refuge for our pals at moments when they find themselves at an impasse in their struggle.

[…]

Now I’d like to see you taking a very large share in this belief that we’ll be relatively successful in founding something lasting.

[…]

I believe that if from now on you began to think of yourself as the head of this studio, which we’ll attempt to make a refuge for several people, little by little, bit by bit, as our unremitting work provides us with the means to bring the thing to completion — I believe that then you’ll feel relatively consoled for your present misfortunes of penury and illness, considering that we’re probably giving our lives for a generation of painters that will survive for many years to come.

[…]

About the room where you’ll stay, I’ve made a decoration especially for it, the garden of a poet […]. And I’d have wished to paint this garden in such a way that one would think both of the old poet of this place (or rather, of Avignon), Petrarch, and of its new poet — Paul Gauguin.

However clumsy this effort, you’ll still see, perhaps, that while preparing your studio I’ve thought of you with very deep feeling.

Let’s be of good heart for the success of our enterprise, and may you continue to feel very much at home here.

Because I’m so strongly inclined to believe that all this will last for a long time.

Good handshake, and believe me

Ever yours, Vincent

–

We’re all going to live there, perhaps forever, just coming home for visits. Or it might just be six months a year. It’ll be fantastic, all on our own on this island. There some little houses which we’ll do up and knock together and live communally.

— John Lennon, on his plan to buy a Greek island where the Beatle family could live together (1967). In The Anthology.

–

We were all going to live together now, in a huge estate. The four Beatles and Brian would have their network at the centre of the compound: a dome of glass and iron tracery (not unlike the old Crystal Palace) above the mutual creative/play area, from which arbours and avenues would lead off like spokes from a wheel to the four vast and incredibly beautiful separate living units. In the outer grounds, the houses of the inner clique: Neil, Mal, Terry and Derek, complete with partners, families and friends. Norfolk, perhaps, there was a lot of empty land there. What an idea! No thought of wind or rain or flood, and as for cold… there would be no more cold when we were through with the world. We would set up a chain reaction so strong that nothing could stand in our way. And why the hell not? ‘They’ve tried everything else,’ said John realistically. 'Wars, nationalism, fascism, communism, capitalism, nastiness, religion – none of it works. So why not this?

— Derek Taylor, in his autobiography Fifty Years Adrift (1984).

–

— Self-Portrait with Portrait of Émile Bernard (Les misérables), by Paul Gauguin (1888).

Readers of the Mercure may have noticed in a letter of Vincent’s, published a few years ago, the insistence with which he tried to get me to come to Arles to found an atelier after an idea of his own, of which I was to be the director.

At the time I was working at Pont-Aven, in Brittany, and either because the studies I had begun attached me to this spot or because a vague instinct forewarned me of something abnormal, I resisted a long time, till the day came when, finally overborne by Vincent’s sincere, friendly enthusiasm, I set out on my journey.

I arrived at Arles toward the end of the night and waited for Dawn in a little all-night café. The proprietor looked at me and exclaimed, “You are the pal, I recognize you!”

A portrait of myself which I had sent to Vincent explains the proprietor’s exclamation. In showing him my portrait Vincent had told him that it was a pal of his who was coming soon.

Neither too early nor too late I went to rouse Vincent out. The day was devoted to getting settled, to a great deal of talking and to walking about so that I might admire the beauty of Arles and the Arlesian women, about whom, by the way, I could not get up much enthusiasm.

The next day we were at work, he continuing what he had begun, and I starting something new.

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

I don’t admire the painting but I admire the man. He was so confident, so calm. I so uncertain, so uneasy.

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

My memory of meeting John for the first time is very clear. … I can still see John now - checked shirt, slightly curly hair, singing ‘Come Go With Me’ by the Del Vikings. He didn’t know all the words, so he was putting stuff in about penitentiaries - and doing a good job of it. I remember thinking, ‘He looks good - I wouldn’t mind being in a group with him.’ … Then, as you all know, he asked me to join the group, and so we began our trip together. We wrote our first songs together, we grew up together and we lived our lives together. And when we’d do it together, something special would happen. There’d be that little magic spark. I still remember his beery old breath when I first met him here [Woolton church fete] that day. But I soon came to love that beery old breath. And I loved John. I always was and still am a great fan of John’s.

— Paul McCartney, in Bill Harry’s The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia (2003).

–

In the beginning he was a sort of fairground hero. He was the big lad riding the dodgems and we thought he was great. We were younger, me and George, and that mattered. It was teenage hero worship. I’ve often said how my first impression of him was his boozy breath all over me—but that was just a cute story. That was me being cute. It was true, but only an eighth of the truth. I just used to say that later when people asked me for my first memory of John. My first reaction was never simple—that he was great, that he was a great bloke, and a great singer. My REALLY first impression was that it was amazing how he was making up all the words.

He was singing “Come Go with Me to the Penitentiary,” and he didn’t know ONE of the words. He was making up every one as he went along. I thought it was great.

— Paul McCartney, according to Hunter Davies annotations of their phonecall on 3 May 1981.

–

And if I say I really knew you well What would your answer be?

Between two such beings as he and I, the one a perfect volcano, the other boiling too, inwardly, a sort of struggle was preparing. In the first place, everywhere and in everything I found a disorder that shocked me. His colour-box could hardly contain all those tubes, crowded together and never closed. In spite of all this disorder, this mess, something shone out of his canvases and out of his talk, too. […]

In spite of all my efforts to disentangle from this disordered brain a reasoned logic in his critical opinions, I could not explain to myself the utter contradiction between his painting and his opinions. […]

One thing that angered him was to have to admit that I had plenty of intelligence, although my forehead was too small, a sign of imbecility. Along with all this, he possessed the greatest tenderness, or rather the altruism of the Gospel.

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

I could just often be the sort of baddie in a situation, and he could be a real soft sweetie, you know? Took everyone by surprise, that!

— Paul McCartney, interviewed by David Frost (1997).

–

I was feeling insecure…

From: Vincent | To: Paul | Wednesday, 3 October 1888

I find my artistic ideas extremely commonplace in comparison with yours.

I always have an animal’s coarse appetites. I forget everything for the external beauty of things, which I’m unable to render because I make it ugly in my painting, and coarse, whereas nature seems perfect to me.

Now, however, the energy of my bony carcass is such that it goes straight to the target; from that comes a perhaps sometimes original sincerity in what I make, if, that is, the subject lends itself to my rough and unskilful execution.

–

Tony Sheridan: [John] never saw himself as a very good singer, for instance.

Interviewer: Really?

Tony Sheridan: No. He never saw himself as comparable to Paul McCartney, even. Which, you know, he was playing with a guy, writing songs with a guy whom he thought was better than he was in many ways. So he had this immense ego and this immense sort of – it was like a motor in him that had to go to new lengths and reach new heights in order to impress somebody or the whole world or whatever.

— In A Long And Winding Road (2003).

–

“Most people in Britain think I’m somebody who won the pools, you know,” he says drily, drawing on a Gauloise. “Won the pools and married a Hawaiian dancer or actress somewhere. Whereas in the States, we’re treated like artists. Which we are! Or anywhere else for that matter,” he added. “But here, it’s like, the lad who knew Paul, got a lucky break, won the pools and married the actress.”

— John Lennon, interviewed for Melody Maker (2 October 1971).

–

It may have been the one that had my song, 'Here, There and Everywhere.’ There were three of my songs and three of John’s songs on the side we were listening to. And for the first time ever, he just tossed it off, without saying anything definite, 'Oh, I probably like your songs better than mine.’

— Paul McCartney, interviewed by Joan Goodman for Playboy (1984).

–

Knowing that love is to share

From the very first month, I saw that our common finances were taking on the same appearance of disorder. What was I to do? […] I was obliged to speak, at the risk of wounding that very great susceptibility of his. It was thus with many precautions and much gentle coaxing, of the sort very foreign to my nature, that I approached the question. I must confess that I succeeded far more easily than I should have supposed.

We kept a box, – so much for hygienic excursions at night, so much for tobacco, so much for incidental expenses, including rent. […] We gave up our little restaurant, and I did the cooking on a gas stove, while Vincent laid in provisions, not going very far from the house. Once, however, Vincent wanted to make soup. How he mixed it I don’t know; as he mixed his colours in his pictures, I dare say. At any rate, we couldn’t eat it. And my Vincent burst out laughing and exclaimed: “Tarascon! La casquette au père Daudet!” On the wall he wrote in chalk: Je suis Saint Esprit. Je suis sain d’esprit. [I am the Holy Spirit. I am sane.]

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

You’ve got to hide your love away

On several nights I surprised him in the act of getting up and coming over to my bed. To what can I attribute my awakening just at that moment?

At all events, it was enough for me to say to him, quite sternly, “What’s the matter with you, Vincent?” for him to go back to bed without a word and fall into a heavy sleep.

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

All I can ever say about it is that I slept with John a lot because you had to, you didn’t have more than one bed - and to my knowledge John was never gay.

— Paul McCartney, in The Brian Epstein Story (2000).

–

To say “I love you” would break all my teeth.

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

You can actually say, “I love you,” to someone, but it’s quite hard. And so that’s why it’s usually easier when you’re a bit drunk. It’s like ‘Here Today’ [on 1982’s Tug of War], which was for John, and there is the line, (sings) “Du du du du du du du, I love you,” and it is a bit of a moment in the song. It would be a bit like Keith Richards saying to Mick, “I love you.” I mean he does, but I’m not sure he’s going to say it. I’m sure the Gallaghers love each other on some level, probably quite deeply, but that certainly isn’t going to get said soon. I think it’s quite an interesting subject and I felt it most recently with [wife] Nancy, I knew I loved her but to actually say, “I love you,” you know, it’s just not that easy.

— Paul McCartney, interview with Pat Gilbert for MOJO (November 2013).

–

Hear me, my lover I can’t be held responsible now For something that didn’t happen I knew you for a minute Oh, it didn’t happen Only for a minute

–

During the latter days of my stay, Vincent would become excessively rough and noisy, and then silent. […]

The idea occurred to me to do his portrait while he was painting the still-life he loved so much – some ploughs. When the portrait was finished, he said to me, “It is certainly I, but it’s I gone mad.”

That very evening we went to the café. He took a light absinthe. Suddenly he flung the glass and its contents at my head. I avoided the blow, and, taking him bodily in my arms, went out of the café, across the Place Victor Hugo. Not many minutes later Vincent found himself in his bed where, in a few seconds, he was asleep, not to awaken again til morning.

When he awoke, he said to me very calmly, “My dear Gauguin, I have a vague memory that I offended you last evening.”

Answer: “I forgive you gladly and with all my heart, but yesterday’s scene might occur again and if I were struck I might lose control of myself and give you a choking. So permit me to write to your brother and tell him that I am coming back.”

My God, what a day!

When evening had come and I had bolted my dinner, I felt I must go out alone and take the air along the paths that were bordered by flowering laurel. I had almost crossed the Place Victor Hugo when I heard behind me a well-known step, short, quick, irregular. I turned about on the instance as Vincent rushed toward me, an open razor in his hand. My look at the moment must have had great power in it, for he stopped and, lowering his head, set off running towards home.

Was I negligent on this occasion? Should I have disarmed him and tried to calm him? I have often questioned my conscience about this, but I have never found anything to reproach myself with. Let him who will fling the stone at me.

With one bound I was in a good Alesian hotel, where, after I had enquired the time, I engaged a room and went to bed.

I was so agitated that I could not get to sleep till about three in the morning, and I awoke rather late, at about half-past seven.

Reaching the square, I saw a great crowd collected. Near our house there were some gendarmes and a little gentleman in a melon-shaped hat who was the superintendent of the police.

This is what had happened.

Van Gogh had gone back to the house and immediately cut off his ear close to the head. He must have taken some time to stop the flow of the blood, for the day after there were a loto f wet towels lying about on the flag-stones in the two lower rooms. […]

When he was in a condition to go out, with his head enveloped in a Basque beret which he had pulled far down, he went straight to a certain house where for want of a fellow-countrywoman one can pick up an acquaintance, and gave the manager his ear, carefully washed and placed in an envelope. “Here is a souvenir of me,” he said. Then he ran off home, where he went to bed and to sleep. […]

I had no faintest suspicion of all this when I presented myself at the door of our house and the gentleman in the melon-shaped hat said to me abruptly and in a tone that was more than severe, “What have you done to your comrade, Monsieur?”

“I don’t know…”

“Oh, yes… you know very well… he is dead.”

I could never wish anyone such a moment, and it took me a long time to get my wits together and control the beating of my heart.

Anger, indignation, grief, as well as shame at all these glances that were tearing my person to pieces, suffocated me, and I answered, stammeringly: “All right, Monsieur, let us go upstairs. We can explain ourselves there.”

In the bed lay Vincent, rolled up in the sheets, humped like a guncock; he seemed lifeless. Gently, very gently, I touched the body, the heat of which showed that it was still alive. For me it was as if I had suddenly got back all my energy, all my spirit.

Then in a low voice I said to the police superintendent: “Be kind enough, Monsieur, to awaken this man with great care, and if he asks for me tell him I have left for Paris; the sight of me might prove fatal to him.”

— On the events of 23 of December 1988. In The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

Auvers-sur-Oise, c. 17 June 1890

My dear friend Gauguin,

Thank you for having written to me again, my dear friend, and rest assured that since my return I have thought of you every day. I stayed in Paris only three days, and the noise, etc., of Paris had such a bad effect on me that I thought it wise for my head’s sake to fly to the country; but for that, I should soon have dropped in on you.

And it gives me enormous pleasure when you say the Arlésienne’s portrait [above], which was based strictly on your drawing, is to your liking. I tried to be religiously faithful to your drawing, while nevertheless taking the liberty of interpreting through the medium of colour the sober character and the style of the drawing in question. It is a synthesis of the Arlésiennes, if you like; as syntheses of the Arlésiennes are rare, take this as a work belonging to you and me as a summary of our months of work together. For my part I paid for doing it with another month of illness, but I also know that it is a canvas which will be understood by you, and by a very few others, as we would wish it to be understood.

–

There are only about 100 people in the world who understand our music. George, Ringo, and a few friends around the world. Some of the artists who recorded our numbers have no idea how to interpret them. […] When Paul and I write a song, we try and take hold of something we believe in – a truth. We can never communicate 100 per cent of what we feel, but if we can convey just a fraction, we have achieved something. We try to give people a feeling – they don’t have to understand the music if they can just feel the emotion. This is half the reason the fans don’t understand, but they experience what we are trying to tell them. Lack of feeling in an emotional sense is responsible for the way some singers do our songs. They don’t understand, and are too old to grasp the feeling. Beatles are really the only people who can play Beatle music.

— John Lennon, Lennon & McCartney Interview for Flip Magazine (May 1966).

–

My friend Dr. Gachet here has taken to it altogether after two or three hesitations, and says, “How difficult it is to be simple.” Very well - I want to underline the thing again by etching it, then let it be. Anyone who likes can have it.

Have you also seen the olives? Meanwhile I have a portrait of Dr. Gachet with the heart-broken expression of our time. If you like, something like what you said of your “Christ in the Garden of Olives” not meant to be understood, but anyhow I follow you there, and my brother grasped that nuance absolutely.

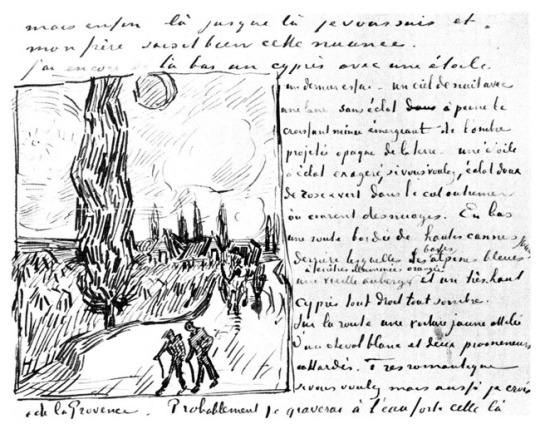

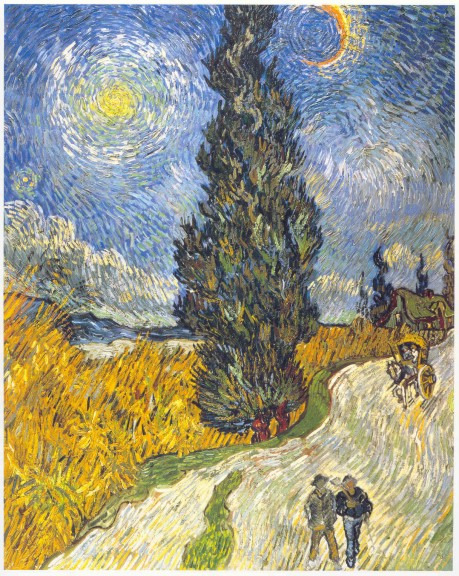

[Here Vincent drew a sketch of the “Cypress with Star.”]

I still have a cypress with a star from down there, a last attempt - a night sky with a moon without radiance, the slender crescent barely emerging from the opaque shadow cast by the earth - one star with an exaggerated brilliance, if you like, a soft brilliance of pink and green in the ultramarine sky, across which some clouds are hurrying. Below, a road bordered with tall yellow canes, behind these the blue Basses Alpes, an old inn with yellow lighted windows, and a very tall cypress, very straight, very sombre.

On the road, a yellow cart with a white horse in harness, and two late wayfarers. Very romantic, if you like, but also Provence, I think.

— Road with Cypress and Star, by Vincent van Gogh.

I shall probably etch this and also other landscapes and subjects, memories of Provence, then I shall look forward to giving you one, a whole summary, rather deliberate and studied. My brother says that Lauzet, who does the lithographs after Monticelli, liked the head of the Arlésienne in question.

But you will understand that having arrived in Paris a little confused, I have not yet seen your canvases. But I hope to return for a few days soon.

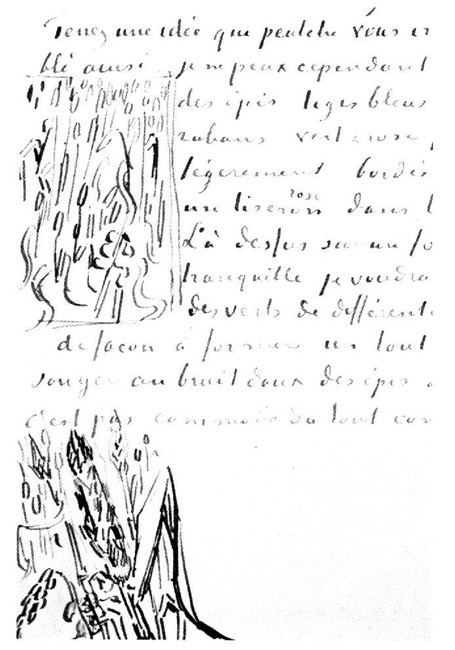

[Here was drawn a sketch of “Ears of Wheat.”]

I’m very glad to learn from your letter that you are going back to Brittany with De Haan. It is very likely that - if you will allow me - I shall go there to join you for a month, to do a marine or two, but especially to see you again and make De Haan’s acquaintance. Then we will try to do something purposeful and serious, such as our work would probably have become if we had been able to carry on down there.

Look, here’s an idea which may suit you, I am trying to do some studies of wheat like this, but I cannot draw it - nothing but ears of wheat with green-blue stalks, long leaves like ribbons of green shot with pink, ears that are just turning yellow, lightly edged with the pale pink of the dusty bloom - a pink bindweed at the bottom twisted round a stem.

— Ears of Wheat, by Vincent van Gogh.

After this I would like to paint some portraits against a very vivid yet tranquil background. There are the greens of a different quality, but of the same value, so as to form a whole of green tones, which by its vibration will make you think of the gentle rustle of the ears swaying in the breeze: it is not at all easy as a colour scheme.

— Unfinished unsent letter from Vincent van Gogh to Paul Gauguin.

–

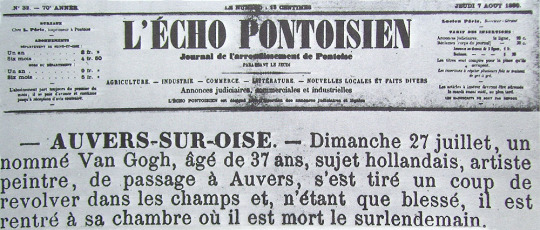

— Auvers-sur-Oise. — Sunday 27 July, a man named Van Gogh, 37, a Dutch fellow, painter, on his way through Auvers, shot himself in the fields and, being only wounded, returned to his room where he died two days later.

–

Here is what I know on his death.

That Sunday he went out immediately after breakfast, which was unusual. […] When we saw Vincent arrive night had fallen, it must have been about nine o'clock. Vincent walked bent, holding his stomach, again exaggerating his habit of holding one shoulder higher than the other. Mother asked him: “M. Vincent, we were anxious, we are happy to see you to return; have you had a problem?”

He replied in a suffering voice: “No, but I have…” he did not finish, crossed the hall, took the staircase and climbed to his bedroom. I was witness to this scene. Vincent made such a strange impression on us that Father got up and went to the staircase to see if he could hear anything.

He thought he could hear groans, went up quickly and found Vincent on his bed, laid down in a crooked position, knees up to the chin, moaning loudly: “What’s the matter,” said Father, “are you ill?” Vincent then lifted his shirt and showed him a small wound in the region of the heart. Father cried: “Malheureaux, [unhappy man] what have you done?”

“I have tried to kill myself,” replied Van Gogh.

[…]

Vincent had gone to the wheat field where he had painted previously […]. Vincent shot himself with a revolver and fainted. The freshness of the evening revived him. On all fours he sought the revolver to finish himself off, but could not find it (and it was not found the following day). Then Vincent gave up looking and came down the hill to regain our house.

[…]

In the morning of the following day, two gendarmes of the Méry brigade, probably alerted by a public rumour, appeared at the house. […] The gendarme then entered the room, and Rigaumon, always in the same tone, questioned Vincent: “Are you the one who wanted to commit suicide?”

- Yes, I believe, replies Vincent in his usual soft tone.

- You know that you do not have the right?

Always in the same even tone Van Gogh replied: “Gendarme, my body is mine and I am free to do what I want with it. Do not accuse anybody, it is I that wished to commit suicide.”

[…]

Theo arrived by train in the middle of the afternoon. I remember seeing him arrive, running. […] But his face was marked by sorrow. He immediately climbed up to his brother who he kissed and spoke to him in their native language. Father withdrew and did not help them. He did not go back in during the night. After the emotion that he had felt on seeing his brother, Vincent had fallen into a coma. Theo and my father kept watch on the casualty until his death, which occurred at one o'clock in the morning.

— Memoirs of Vincent Van Gogh’s stay in Auvers-sur-Oise (1956), by Adeline Ravoux (aged 76).

–

Paris, 5 August 1890

To say we must be grateful that he rests - I still hesitate to do so. Maybe I should call it one of the great cruelties of life on this earth and maybe we should count him among the martyrs who died with a smile on their face.

He did not wish to stay alive and his mind was so calm because he had always fought for his convictions, convictions that he had measured against the best and noblest of his predecessors. His love for his father, for the gospel, for the poor and the unhappy, for the great men of literature and painting, is enough proof for that. In the last letter which he wrote me and which dates from some four days before his death, it says, “I try to do as well as certain painters whom I have greatly loved and admired.” People should realize that he was a great artist, something which often coincides with being a great human being. In the course of time this will surely be acknowledged, and many will regret his early death. He himself wanted to die, when I sat at his bedside and said that we would try to get him better and that we hoped that he would then be spared this kind of despair, he said, “La tristesse durera toujours” [The sadness will last forever]. I understood what he wanted to say with those words.

A few moments later he felt suffocated and within one minute he closed his eyes. A great rest came over him from which he did not come to life again.

— Letter from Theo van Gogh to Elisabeth van Gogh.

–

Vincent van Gogh did not kill himself, the authors of new biography Van Gogh: The Life have claimed.

Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith say that, contrary to popular belief, it was more likely he was shot accidentally by two boys he knew who had “a malfunctioning gun”.

The authors came to their conclusion after 10 years of study with more than 20 translators and researchers.

It has long been thought that he shot himself in a wheat field before returning to the inn where he later died.

[…]

But author Steven Naifeh said it was “very clear to us that he did not go into the wheat fields with the intention of shooting himself”.

“The accepted understanding of what happened in Auvers among the people who knew him was that he was killed accidentally by a couple of boys and he decided to protect them by accepting the blame.”

He said that renowned art historian John Rewald had recorded that version of events when he visited Auvers in the 1930s and other details were found that corroborated the theory.

They include the assertion that the bullet entered Van Gogh’s upper abdomen from an oblique angle - not straight on as might be expected from a suicide.

“These two boys, one of whom was wearing a cowboy outfit and had a malfunctioning gun that he played cowboy with, were known to go drinking at that hour of day with Vincent.

"So you have a couple of teenagers who have a malfunctioning gun, you have a boy who likes to play cowboy, you have three people probably all of whom had too much to drink.”

He said “accidental homicide” was “far more likely”.

“It’s really hard to imagine that if either of these two boys was the one holding the gun - which is probably more likely than not - it’s very hard to imagine that they really intended to kill this painter.”

Gregory White Smith, meanwhile, said Van Gogh did not “actively seek death but that when it came to him, or when it presented itself as a possibility, he embraced it”.

He said Van Gogh’s acceptance of death was “really done as an act of love to his brother, to whom he was a burden”.

— by Will Gompertz for BBC News (17 October 2011).

–

Now everybody seems to have their own opinion Who did this and who did that But as for me I don’t see how they can remember When they weren’t where it was at

–

For a long time I have wanted to write about Van Gogh, and I shall certainly do so some fine day when I am in the mood. I am going to tell you now a few rather timely things about him, or rather about us, in order to correct an error which has been going around in certain circles.

— In the introductory chapter of The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

I’d like to say this is just as I remember it, if it hurts anyone or any families of anyone who’ve got a different memory of it. Let me say first off, before you read this book even, that I loved John. Lest it be seen that I’m trying to do my own kind of revisionism, I’d like to register the fact that John was great, he was absolutely wonderful and I did love him. I was very happy to work with him and I’m still a fan to this day. So this is merely my opinion. I’m not trying to take anything away from him. All I’m saying is that I have my side of the affair as well, hence this book. When George Harrison wrote his life story I Me Mine, he hardly mentioned John. In my case I wouldn’t want to leave him out. John and I were two of the luckiest people in the twentieth century to have found each other. The partnership, the mix, was incredible. We both had submerged qualities that we each saw and knew. I had to be the bastard as well as the nice melodic one and John had to have a warm and loving side for me to stand him all those years. John and I would never have stood each other for that length of time had we been just one-dimensional.

— Paul McCartney, in the introduction of Many Years from Now.

–

All the rest everyone knows who has any interest in knowing it, and it would be useless to talk about it were it not for that great suffering of a man who, confined in a madhouse, at monthly intervals recovered his reason enough to understand and furiously paint the admirable pictures we know.

The last letter I had from him was dated from Anvers, near Pontoise. He told me that he had hoped to recover enough to come and join me in Brittany, but now was obliged to recognize the impossibility of a cure:

“Dear Master” (the only time he ever used this word), “after having known you and caused you pain, it is better to die in a good state of mind than in a degraded one.”

He sent a revolver shot into his stomach, and it was only a few hours later that he died, lying in his bed and smoking pipe, having complete possession of his mind, full of the love of his art and without hatred for others.

In Les Monstres Jean Dolent writes, “When Gauguin says ‘Vincent’ his voice is gentle.” Without knowing it but having guessed it, Jean Dolent is right.

You know why… . .

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

At one point during the evening at the Waldorf-Astoria, McCartney answers a random question with, “No, I always felt much closer to John.” Out of the mouth of anyone else, “John” is just a name, a mere monosyllable. But when the name is uttered by McCartney, the ghostlike presence of John Lennon suddenly descends on the evening. Lennon’s name, so simply invoked by McCartney, takes on the power of a talisman, conjuring up an entire shared cultural scrapbook of images defining musical collaboration and the purest of camaraderie. McCartney owns the pronunciation of “John” the way Katharine Hepburn made “Spensah�� Tracy her own.

— In the Paul McCartney interview The act you’ve known for all these years: McCartney today, by Andrew Marton for the Boston Globe (3 December 2000).

–

How long did we remain together? I couldn’t say, I have entirely forgotten. In spite of the swiftness with which the catastrophe approached, in spite of the fever of work that seized me, the time seemed to me a century.

Though the public had no suspicion of it, two men were performing there a colossal work that was useful to them both. Perhaps to others? There are some things that bear fruit.

— The Intimate Journals of Paul Gauguin by Paul Gauguin (1936).

–

[And amalgamation of often imperfect (and other times scary) parallels that possibly led John to compare his relationship with Paul to that of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. An overly long self-indulgent post.]

More on the painters series:

The Surrealist | Lennon - McCartney & René Magritte

#lennon mccartney#macca#johnny#vincent van gogh#paul gauguin#we were more artsy#the person I actually picked as my partner#meta#my stuff#Early Days#The Pound Is Sinking#Here Today#Imagine#Jealous Guy#here there and everywhere#Hide your Love Away

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Loving Vincent

‘One can speak poetry just by arranging colours well, just as one can say comforting things in music.’ Vincent van Gogh

I imagine that not many of you know this but I completed a Masters degree a couple of years ago in Philosophy (of Art), specifically in the history of art and how what we value in works of art has changed over time, with particular focus on Dutch Art. What started out as an interest in the work of Aelbert Cuyp very quickly found itself fascinated by Vincent van Gogh, not necessarily because of his oh so famous works such as Starry Night and Sunflowers but more because I wanted to know who this character was who emerged during Impressionism in a very different way to other more classic members such as Monet and Renoir.

I have been reading a lot on van Gogh at the moment, visiting exhibitions etc. and I think there is enough documented on how unhappy he was, but let us look at the little happiness we can take from it all. Vincent lived a very sad and lonely life, struggling to find himself for much of it. From the tender age of sixteen he worked as an assistant in an art gallery for seven years, but this was not what suited him and he did not suit it. He later worked as a teacher in England, as well as in a bookshop, learning languages such as Latin and Greek in Amsterdam. He not only struggled to find himself as a person but also as an artist, which is evident in the change in his style of painting over the years.

It was the movement of Impressionism that moved him particularly, which was emerging in French society at the time. Artists that particularly moved him included Monet, Renoir, Gauguin, Cézanne, and Ernest Quost’s Garden of Hollyhocks. During the years of 1886 and 1887, Vincent’s style can be seen to be very similar to that of the more traditional impressionists, including his painting Montmartre: Behind Le Moulin de la Galette 1887 (pictured below). It was not just the paintings that he admired during this time, but the artists themselves and Vincent longed to have friends who would inspire him and who he could inspire also – to start a little circle of artists. He hoped that those joining him in this circle would be those he admired most, namely impressionist painters of the time, sadly nothing came of this.

It was in the last moments of his life and in death that Vincent found happiness. Following unsuccessful attempts at selling his work and several mental breakdowns, Vincent’s brother (Theo) wrote to him on 16th July 1889 with great news, that in January 1890 there would be an exhibition in Brussels called Les Vingt (The Twenty) that would feature twenty avant-garde artists of the time, of which Vincent was invited to be one. Not only was this the first time that he would be asked to exhibit his work but he would have the opportunity of displaying his work alongside those he admired and longed to be with, including Renoir, Cézanne and Toulouse-Lautrec. As much as we know of his unhappiness, it is important to note that during Vincent’s last days, he did begin to get recognition for his work. Although Les Vingt gained mixed reviews, both by other artists and the public, many did enjoy his work.

A month after the closing of Les Vingt, Vincent was given another opportunity to showcase his work, this time in Paris in March 1890 as the Société des Artistes Indépendants, in which he put ten works up for exhibition. At this exhibition, the master of the impressionists Monet described Vincent’s work as being ‘the best in the exhibition’, Theo told Vincent.

Tragically, this recognition is not enough to pull Vincent out of the state he is in and he ultimately shoots himself in the stomach, managing to make his way back to his bedroom where he dies two days later, with his brother by his side. Theo writes to his wife Jo that Vincent’s last words include that ‘this is how I wanted to go & it took a few moments & then it was over & he found peace he hadn’t been able to find on earth’. At his funeral, there were twenty attendees, half of which were artists. There were his canvases hung all around him, decorating the room like a halo.

Vincent’s friend Bernard notes that ‘the coffin was covered in a simple white cloth and surrounded with masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he loved so much, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere.’ Theo also writes to his wife, once more, that ‘there were masses of bouquets and wreaths. Dr Gachet arrived first with a magnificent bunch of sunflowers because he [Vincent] loved them so much’.

Shortly after the funeral, Vincent’s memory was already largely engrained in the minds of many. Quost who painted the Garden of Hollyhocks, which Vincent loved so much, gifted this to Theo with a note on the back that read ‘To Theo van Gogh. This painting that my friend Vincent loved so much.’ Sadly, Theo too passed away only six months after Vincent’s death, having been stricken with Syphilis. In 1914, Theo’s remains were taken to be buried with his brother, having played such a large part in Vincent’s growth and life as an artist and man.

The van Gogh’s graves constantly had sunflowers planted on them from their death to 1950, by Dr Gachet and then by his son Paul. When France had been occupied, the Germans asked permission to be able to lay flowers at their final resting place.

Perhaps Vincent did not find quite what he wanted in life, knowing mostly loneliness and being largely misunderstood. In death however, he has been immortalised as one of the greatest artists to have ever lived. It is impossible to not love a man who loved others so deeply, who loved the world and the flowers and the stars. It is nothing short of a tragedy to think it was not long after his death that he began to gain true recognition and sell paintings, not long at all. But life gives with the same hand with which it takes.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s Get Label-Conscious: Making a Museum Vice a Museum Virtue

By: Kathryn Holihan

On November 3, 2018 artist Michelle Hartney secretly hung her own labels next to prominent works by Picasso and Gauguin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York. Her self-titled “Hang and Run” performance calls for museums to “separate the art from the artist,” for both Picasso and Gauguin share exploitative and chauvinistic pasts, yet continue to be venerated by museums across the world. Quoting feminist scholar Roxanne Gay and comedian Hannah Gadsby, Hartney’s labels prompt the question: “what is the responsibility of the art institution to educate viewers and turn the presentation of an artist’s work into a teaching moment?”

Michelle Hartney’s “Hang and Run” performance: https://www.michellehartney.com/correct-art-history

Though Hartney’s website has little to say about her decision to craft guerilla museum labels, this act undoubtedly hits the museum where it hurts. Museums are label-conscious. Nearly every object on display comes paired with a label (sometimes lovingly referred to as a “tombstone”), listing basic information, including the title, artist, date, medium, and inventory number of a work. Some labels offer additional content, be it a visual description of the work, an explanation of the artistic process, or other information to assist the viewer in the act of observation. In just a few lines (because who wants to read a long museum label?), they pack a lot of punch. They should address a target audience, use accessible language, engage with the object, and, perhaps, even raise a provocative question. And though you won’t find this listed among the International Council of Museums (ICOM) standards or the V&A’s ten points to writing a gallery text, I suspect museum professionals (as museum-goers themselves) also know that in the galleries—perhaps more than we’d like to admit—our eyes dart right for the label, after only a passing glance at the artwork itself. The label is our collective museum vice, but museum professionals might make it a virtue.

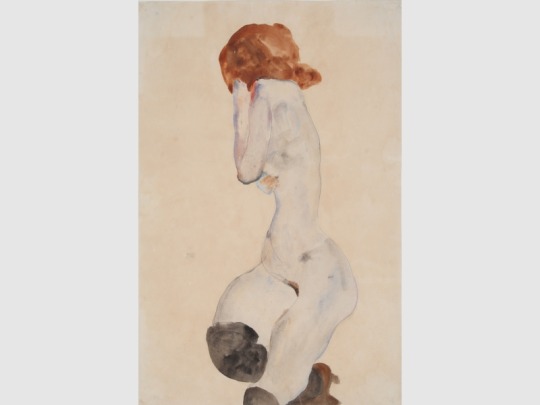

Egon Schiele, UMMA, and #MeToo

A recent exhibit at UMMA’s State Street entrance showcased a new acquisition of works by the Austrian expressionist and controversial figure, Egon Schiele. In preparation for the show, Associate Curator Laura De Becker studied Schiele’s career, including the allegations lodged against him for sexual misconduct in the early twentieth century. The vagaries surrounding the circumstances of the charges, however, far exceeded what De Becker would be able to recapitulate in a mere tombstone caption. Whereas the exhibit’s digital announcement cited Schiele’s problematic status, a conventional label listing the title, artist, date, and medium, was all that accompanied the featured works in the museum gallery. “We received a complaint about this,” De Becker reported, “and we decided to write that label,” referring to an additional text she penned in response to visitor feedback, titled “Curator Laura De Becker reflects upon Egon Schiele in the #MeToo era.”

Female Nude in Black Stockings, Egon Schiele

In this additional caption, De Becker contextualized the controversy surrounding Schiele, the moral panic prompted by his “pornographic” nudes, and his exhibition of work to a minor, for which he served a short prison sentence. De Becker further embedded Schiele’s polemical past within contemporary debates regarding consent and the treatment of women, invoking conversations reenergized by the #MeToo movement. “Museums are reevaluating their practice in displaying and discussing works by artists such as Schiele,” the new caption explained, reflexively gesturing to the ways in which artists are being “scrutinized anew” not only at UMMA, but in many other museums. In the 2018 exhibition Klimt and Schiele at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston, for example, curators revised wall texts to bring Schiele’s transgressions to light. The text, however, confined to a small series of Schiele’s early works, minimized the artist’s culpability to a specific period of his artistic career. In so doing, the MFA passed up the opportunity to, as Becker puts it, “review historical practices through the lens of evolved thinking,” be it in an ethical, moral, or legal sense.

In writing the additional caption for the Schiele exhibit at UMMA, De Becker reported, “I did not offer up any truths. This is a complicated issue, which museums are still dealing with.” Above all, she explained, “this prompted the centuries-long question: Can we disconnect art from its maker?” Using the label to prompt critical questions, De Becker embraced the politics of the label. Responding to visitorship, she mobilized the caption, not as an “objective” museal tool, but as a means to engage the public and perhaps prompt a different reading of the artwork in light of its historical past. Among a set of challenging questions contained in the new label, De Becker asked, “How do such issues affect how we look at these images now and what role does the viewer play when seeing and admiring them?”

“Race-ing through the Archive”

Shortly upon assuming her role as deputy director of curatorial affairs and curator of modern and contemporary art at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA), Vera Grant and her colleagues began a concerted “deep drive” through UMMA’s holdings. Grant calls this ongoing venture “race-ing through the archive,” for the “elusive task of digging through the [museum] archives” is at its core an assessment of the many dimensions of race, gender, and sexuality manifest in UMMA’s encyclopedic collection. Grant’s use of the word “archive” here is deliberate, as the UMMA staff considers issues of representation—who, how, and what is being represented and to whom—from level of the artwork’s subject matter down to the language of its accompanying label. The ultimate goal, Grant attests, is to “share our own dilemmas and thoughtfulness in how we address these matters.”

Though denoted as a standard museum protocol, the act of labeling is far from simple or standardized. The label is at once liberating and limiting. “It is part of a spatial grid within which we move and interact in this world,” Grant explains. As a form of categorization, the label provides a certain sense of comfort in a complex world. “It’s almost like a form of conquering and then we can move on” she adds. But by the same hand, a label is severely limiting, as Grant notes, “that’s how labels work—they don’t tell many stories, they tell one.” A strong statement on the wall might create a miscommunication or prevent engagement across cultures. Despite the serious advantages and disadvantages of the object label, one thing is clear: it is powerful. It can elicit an array of reactions, as Grant speaks from experience about the “abundance of responses to a bit of square footage on the wall.”

One initiative stemming from “race-ing through the archive” was to address “the charged and unexamined nature of lingering object captions,” Grant reports. Take, for instance UMMA’s re-examination of the uncritical, original caption paired with the charged work J. Marion Sims: Gynecological Surgeon. Both the label and illustration lionize Sims, who stands with his arms folded at the head of the hospital scene. The illustration reproduces a racist, medical gaze, as it prompts the observer to join the ranks of other visiting surgeons who ogle the patient—an Alabama slave known only by her first name, Lucy. The caption centers less on Lucy, and more on the heroic and mythical biography of James Marion Sims, the so-called “father of gynecology.” A portion of the troubling description (below) served as the illustration’s official caption since the illustration’s accession to the University collection:

Little did James Marion Sims, M.D., (1813-1883) dream, that summer day in 1845, as he prepared to examine the slave girl, Lucy, that he was launching on an international career as a gynecologic surgeon; or that he was to raise gynecology from virtually an unknown to respected medical specialty. Nor did he realize that his crude back-yard hospital in Montgomery, Alabama, would be the forerunner of the nation's first Woman's Hospital, which Sims helped to establish in New York in 1855. Dr. Sims, who became a leader in gynecology in Europe as well as in the United States, served as president of The American Medical Association, 1875-1876; and was honored by many nations.

Contextualizing and reframing this object and text pairing, UMMA hopes to wield the power of the label to address contemporary issues, in this instance, the entanglement of violence, slavery, and medicine. Performing an academic “hang and run” of their own, Grant and her colleagues are getting label-conscious. While “race-ing through the archive,” UMMA hopes to leverage the label as a tool for grappling with artistic limitations and interrogating the museum’s own authority. Welcoming visitors into the fold, labels solicit a public response to the same questions facing museum curators: how might we use tensions manifest in the collection to reflect on the past and present and the evolution of cultural understanding? In the galleries, the visitor’s eye might still dart right to the label, but now it talks back.

Kathryn Holihan is a doctoral candidate in German Studies at the University of Michigan, where she is also a graduate of the Museum Studies Program and a participant in the Science, Technology, and Society Program. Her dissertation project Staging the Somatic: The Popular Hygiene Exhibition in Germany, 1882 1931 examines a series of hygiene exhibitions staged in twentieth-century Germany. She investigates how a group of curators, politicians, medical officials, and artists wielded public display to produce and popularize knowledge about the body. Kathryn has taught German and History courses including the original course Unsolved Mysteries: Crime, Criminology, and the Detective in Modern Germany. Kathryn is a member of a Think Tank Act conducting research on museums and public efficacy. She is also the education and curatorial assistant at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

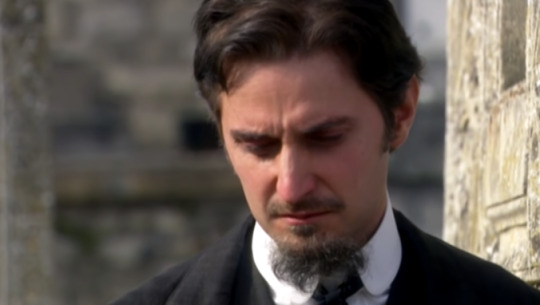

How quickly time flies. If Besotted hadn’t reminded me in the comments, I would’ve completely forgotten that I had a last episode of The Impressionists to catch up with. Forgetting the Re-Watch is symptomatic. I may have enjoyed the show, and the wide smiles that Armitage was allowed to brighten the screen with were certainly welcome, but somehow this mini-series was never – and never will be – my favourite of Richard’s works.

It’s not *all* because of the wig and look of Claude Monet. *That* is easily balanced out by the wide smiles! My lukewarm feelings about this mini-series has more to do with my general lack of enthusiasm for impressionism. I fully appreciate the importance of this arts movement for the development of painting and art in general, and I understand the impressionists’ value. In many case I actually do find their paintings particularly evocative, beautiful and touching. I guess, my problem with them is that they have become too popular – which usually makes me turn away from something. That’s unfair – but unfortunately true. But I totally concede that – particularly Monet’s – Impressionist paintings are incredibly beautiful.

Quick Summary

We pick up again in episode 3 of TI with the group celebrating Edouard Manet’s formal recognition as an artist after he has been awarded the Légion d’Honneur. However, Manet is suffering from syphilis and his health deteriorates. He dies in 1883. Monet, OTOH, is living with Alice Hochedé after his wife’s death. The two of them become a couple, marry and eventually settle in Giverny. Monet develops his serial painting technique, always following the changing light.

A large part of this episode is taken up with the life and travails of Paul Cézanne who is seen as a revolutionary new painter by the impressionists. Despite an affluent background, he lives in poverty with his working class wife and illegitimate son. First shunned by the art world, Cézanne’s genius is eventually recognised and he joins the Impressionists as the most celebrated painters in the world. They overcame all the obstacles and changed painting – and art – forever. So much for the summary of episode 3.

Beards and Hair

I was quite amused in this episode about the changing hairstyles of Claude Monet. Starting out with short hair and a pipe, the next scene in a café he had long hair again. Continuity was a bit lax there, I thought 😂. But at least we could see that RA really knew how to smoke. Yep, as an ex-smoker (almost 6 months to the day) I notice such things. – Eventually the episode settled into short hair for Claude. And I couldn’t help but feel reminded of my personal hero Leon Trotzky…

Tenuous. I know. But fun. Right down to the left eyebrow.

However, let’s stay quickly with the look – ok, I am a not a fan of facial shrubbery at all, and particularly not these kind of standalone shrubs on upper lip and chin. If there has to be facial hair, give me a full blown meadow that covers all (beard) or stay with the manicured lawn aka stubble. Looking at the overgrown goatee on Richard’s chin, however, I am wondering whether it is actually his own. Not only because he has always been so proud of his fast growth and thus the conclusion lies near. No, but also because of the tell-tale triangle underneath his lower lip. Mr Armitage has, indeed, a rather pretty beard-growth pattern (see evidence on right).

Elder statesman or ill-fitting wig?

I was quite taken with the elder statesman look he was given in the latter part of the episode, once Monet had settled down with Alice and concentrated on creating Giverny as his inspirational garden. (I don’t really think that Richard has an old man’s face, yet, though, so I finally was reconciled with Julian Glover playing Monet senior in the framework plot.) In fact, I found myself fascinated by the grey temples and the short hair, and I kept screen-shooting.

#gallery-0-7 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-7 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-7 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-7 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

I also enjoyed that his eye crinkles came into play…

Things I Loved

As always, Richard – even considerably younger and less experienced than today – was a pleasure to watch. I loved the scenes where he glowed with enthusiasm, happiness and lust for life, smiling widely with glowing teeth. But I especially liked the scenes where you could hear him laugh. It really doesn’t happen very often at all that you can hear Richard Armitage laugh in one of his roles. He is the go-to man for scowling (Guy of Gisborne, John Thornton), growling (Francis Dolarhyde, Thorin Oakenshield) and frowning (John Porter, Daniel Miller). And yet his laugh is an absolute joy. In German we call his kind of laugh “gurgling” – but that doesn’t quite hit it in English. What I like about it is not what it looks like (although I believe that *every* laugh looks beautiful), but what it sounds like. Reminder:

youtube

That’s what he laughed like in his younger years. (I think his laugh now has become slightly deeper, more baritone, whereas it sounded more tenor way back in the early 2000s.) And it is infectious. Bookmark and keep near for any rainy day. It definitely works.

Ok, moving on. The old fogey in me also quite enjoyed the mature-lovestory-section of this episode. We were discussing it somewhere in the comments, I believe, and the series didn’t really get into it, but there are suspicions that Monet and Alice Hoschedé started their relationship even before she split with her husband and moved in with the Monets. Her youngest child may even have been by Monet. In that sense, it was lovely that the series spent a little time with Monet’s and Alice’s relationship. I wasn’t quite convinced by Richard’s choice to play Monet as out of breath as if he had just raced a marathon when he catches Alice in the garden and proposes. But this completely balanced everything out:

Why yes, Mr Thornton, I am coming home with you.

Not to mention this:

Gorgeous crinkles, like arrows pointing at happy eyes.

Ok, bonus for the romantics among you:

Yeah, man, this was such a clean show, it almost seemed as if it was made for school TV. You know what I mean? Your history/art/literature teacher wheeling in the big TV and the VCR, and then you’d sit through an hour of veritable and highly educational but mindnumbingly clean-and-boring docudrama? Well, to be suitable for teenagers, no tit may be shown, no mention of sex may be made and no tongue may be used. 😂

And Where It Went Wrong For Me

And maybe that is what ultimately irked me about this show, or what prevented me from saying ” I love Love LOVE The Impressionists!!” It’s not that I need sex in every TV show to keep me engaged. And I am a big fan of contextualising history and presenting it in a way that the viewers can relate to. In that sense it was great that this mini-series made an attempt at showing the personal sacrifices all those pioneering painters had to make in order to succeed with their art. From losing Bazille in the war, via Manet’s syphilis, Degas’ eye illness and declining fortunes, to the overwhelming poverty of Monet and Cézanne, TÍ is not simply a list of artistic milestones in the painters’ lives, but a look at how they progress as painters as well as men. And herein may also be the problem for me – I never fully committed to the show, and maybe so because of the lack of women in the narrative. Don’t get me wrong – of course I “saw” Camille and Alice, and Mme Manet, Mme Cézanne and various models. But that’s exactly it, “various models”. Sure, you don’t have to explain to me that the 19th century was still a time dominated by men. But that doesn’t mean that in their private lives, men were uninfluenced (and untouched) by women. Or that women artists did not exist or not contribute to the development of art. Berthe Morisot and Eva Gonzalez were part of the impressionist set – they don’t even turn up in passing in this series. The wives and women remain in their traditional role as nurturer, house-keeper and mothers.

Women. Reduced to nurturers and parasol-bearers?

(Left-field thought: Maybe it is also because this show was made in 2006 that women aren’t represented more prominently?) And all that may also be due to the limited amount of time available (3 hours) for a group of painters. In fairness, it would’ve been impossible to depict the lives and times of the impressionists in detail, and hence also a number of *male* protagonists of the movement (Pissarro? Gauguin? Sisley? Matisse?) had to be left out in order to contain the show. However, for me the whole show remained somewhat one-dimensional.

The Disclaimer

For fans of Richard Armitage, however, TI is definitely a worth-while show to watch. The smiles, the laugh, and the mannerisms that are just delightful to recognise. From Richard’s insistent innovative use of his teeth, to delicate hand movements and holding his head at *that* characteristic angle, there are certain “trademarks” in his acting repertoire that superfans such as us have no trouble identifying.

#gallery-0-8 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-8 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-8 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-8 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

And Richard convincingly acts emotions and draws the audience into the emotional world of the sensitive artist.

Lastly I want to commend the mini series for producing beautiful images. I loved the wide shots especially because they illustrated so clearly what the impressionists were after.

These shots play with the impressionists’ emphasis of depicting the *moment*, pinpointing the changeability of art, and the transience of life. The impressionists’ penchant for working plein air is ideally illustrated here. And the series is obviously also conscious of depicting movement rather than static subjects, and the different qualities of light – during the day, the seasons, inside and outside, in rain, sun or locomotive steam – as these are impressionist characteristics that are often also attributed to film (and photography). In that sense the series puts the theory into practice.

Last note: Just as I was watching episode 3 of TI, the news came through that a Monet painting has set a new record price for works by the artist. From the “haystack” series of paintings, the picture was sold for $110m in New York. An indication of how *right* the impressionists were.

I finish with a quote by Berthe Morisot, of all people.

It is important to express oneself… provided the feelings are real and are taken from your own experience.

The impressionist painters did that beautifully, and showed us that it can be done and *should* be done. No one better to portray “real” feelings than Richard. And I am always happy to see how he expresses them.

Re-Watching The Impressionists [part 3] – Finale How quickly time flies. If Besotted hadn't reminded me in the comments, I would've completely forgotten that I had a last episode of

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Audience With… Brett Anderson

UNCUT Magazine

December 2010

Interview: John Lewis

Brett Anderson has some fans in odd places. This month, Uncut’s email boxes are positively heaving with questions from adoring fans in Peru, Serbia, Japan, New Zealand, Belgium, South Africa, Slovenia and Russia. “I’m quite popular in odd places,” he says. “Suede had No 1s in Chile and Finland. We were massive in Denmark. If asked why Denmark, my stock answer was that, well, I’m a depressed sex maniac and so are most Scandinavians. We toured China long before most Western pop groups. I remember playing Beijing, to a crowd divided by armed soldiers facing the audience. That was pretty scary.” Anderson is currently back in the Far East, speaking to Uncut as he overlooks Kowloon Harbour, preparing for solo dates. Later in the year he’ll be in London for a big O2 show with Suede (sans original guitarist Bernard Butler, although the two remain good friends). “I wanted to check out what the stage was like at the O2 Arena,” he says. “So I went to see The Moody Blues with my father-in-law. Come on, you can’t argue with ‘Nights In White Satin’. What a tune!”

I presume you’re aware of the ‘reallybanderson’ Twitter account purporting to be by you. Amused or offended? Helen, Birmingham

Twitter is one of those strange things, like Facebook, that I don’t have anything to do with. But I have to grudgingly admit that the reallybanderson Twitter updates are rather funny [starts giggling]. And the guy doing it is obviously a bit of a Suede fan, because there are some very detailed references to b-sides and bla-di-blah. I can’t exactly complain about it without coming across as a real tit. It’s just fun and no-one really thinks it’s me, it’s a cartoon version of me reflected through some fairground mirror. I don’t think anyone reads it and thinks, ‘Oh, Brett Anderson has Jas Mann from Babylon Zoo doing his washing up, or Brett punched Damon in the street.’ It is, ha ha ha, quite witty. Having shown them the picture inside the Best Of Suede CD, my kids would like to know why you refused to feed me for five years? Also – can my mum have her top back? And are you around for a trip to the Imperial War Museum? Bernard Butler

Yes, what most fans don’t realise is that we kept Bernard in a cage for five years, and fed him edamame beans and tap water. Regarding his mum’s top – he should know that it’s long been ripped up and destroyed by the front row of the Southampton Joiners, or somesuch venue. Now, the Imperial War Museum – me and Bernard were talking about getting older the other day and he said: “Are you finding yourself increasingly interested in British military history?” And I have become oddly fascinated with watching WWI docs on YouTube. It’s not just the personal tragedies, but the sense of it being a shocking transition point between the Victorian world and modernity. The idea that they were going into war on horseback, and by the end of it they were in tanks. Blimey. So tell Bernard I will be going to the museum, soon… What’s your favourite Duffy song? Kris Smith, Wembley

I thought “Rockferry” was a very beautiful, stirring track. So that’s the only one I know well, but I’m really pleased for Bernard that that was a big success [Butler co-wrote and produced much of the album]. He’s an incredibly talented person and works incredibly hard, and he’s one of those people who is just obsessed with music. People like that deserve success. Did I ask him to join the Suede show at the O2? No. I told him about it, but he’s moved on so far from Suede that it would have been odd, and we’ve had a completely different lineup since he left. I don’t think he’d want to be jumping around a stage again! He’s much happier doing what he does now, I think he’s really found his calling. Do you still have your cat, Fluffington? Claire Vanderhoven, Holland

Unfortunately, he’s ascended to cat heaven. He had 15 long years of adoration. Am I getting another cat? Well, I recently got married, and my wife brought two Italian greyhounds with her. I don’t know if anyone is aware of them, but Italian greyhounds are like little cats. Ours are eight years old but look like miniature foxes, bonsai greyhounds. But incredibly fast, like little bullets. When they’re not running they spend their whole life under the duvet. Someone once told me they were bred by the Pharaohs as bedwarmers! Brett, do you have a copy of the single I recorded with Suede: “Art” b/w “Be My God”? If so, could I have one? Mike Joyce