#but so many articles now are written with very obvious biases in favor of the ship

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I know and understand that Buddie gets engagement but the Buddie dicksucking the press has been doing is really, umm... it's really something!

#As someone who has been here for years#it's also just... weird as fuck to see#It was never like this before LOL#IF Buddie was mentioned in the press it was within the context of “fans want to see this”#but so many articles now are written with very obvious biases in favor of the ship#and it's just so ODD#like. Where was this energy when Buddie was literally the ONLY practical choice for both characters?#Where was this energy ANYWHERE over the past few years? like what are we doing#What changed#tv: 911#jack.txt

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The psychology of passive barriers

A surprising thing happens to people in their forties. After working hard, buying a house, and starting a family, they suddenly realize that they'd better start being responsible with their money. They begin reading financial books and trying to learn how to set up a nest egg for themselves and their families. It's a natural part of growing older. If you ask these people in their forties what their biggest life worry, the answer often is, quite simply, money. They want to learn to manage their money better, and they'll tell you how important financial stability is to them. Yet the evidence shows something very different. In the table below, researchers followed employees at companies that offered financial-education seminars. Despite the obvious need to learn about their finances, only 17% of company employees attended. This is a common phenomenon.

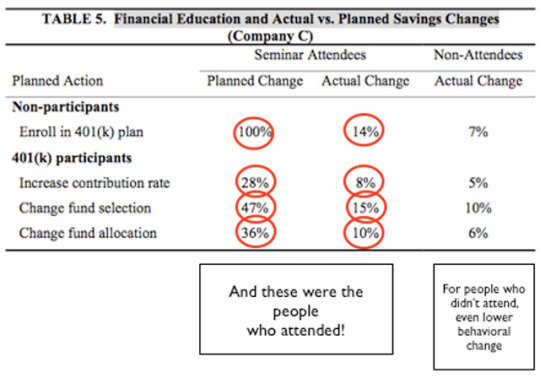

As Laura Levine of the Jump$tart Coalition told me and I paraphrase Bob doesn't want to attend his 401(k) seminar because he's afraid he'll see his neighbor thereand that would be equivalent to admitting he didn't know about money for all those years. They also don't like to attend personal-finance events because they don't like to feel bad about themselves. But of those who did attend the employer event, something even more surprising happens. Of the people who did not have a 401(k), 100% planned to enroll in their company's 401(k) offering after the seminar. Yet only 14% actually did. Of those who already had a 401(k), 28% planned to increase their participation rate. 47% planned to change their fund selection (most likely because they learned they had picked the default money-market plan, which was earning them virtually nothing). But less than half of people actually made the change. This is the kind of data that drives economists and engineers crazy, because it clearly shows that people are not rational. Yes, we should max out our 401(k) employer match, but billions of dollars are left on the table each year because we don't. Yes, we should start eating healthy and exercising more, but we don't. Why not? Why wouldn't we do something that's objectively good for us? Barriers are one of the implicit reasons you can't achieve your goals. These barriers can be psychological or profoundly physical, like something as simple as not having a pen when you need to fill out a form. But the underlying factor is that they are breathtakingly simple and if I pointed them out to you about someone else, you would be sickened by how seemingly obvious they are to overcome. It's easy to dismiss these barriers are trivial, and say, Oh, that's so dumb! when you realize that not having an envelope nearby could cost someone over $3,000. But it's true. And by the end of this article, you'll be able to identify at least three barriers in your own life whether you want to or not.

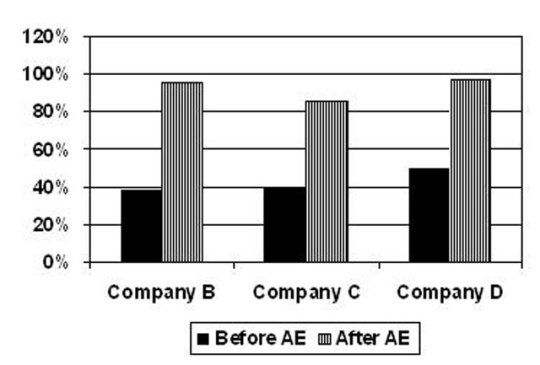

Why People Don't Participate in Their 401(k)s If you're like me, whenever you hear that one of your co-workers doesn't participate in their 401(k) especially if there's an employer match you scratch your head in confusion. Even though this is free money, many people still don't participate. Journalists will cite intangibles like laziness and personal responsibility, suggesting that people are getting less responsible with their money over time. Hardly. It turns out that getting people to enroll in their 401(k) is just plain hard. Using simple psychological techniques, however, we can dramatically increase the number of people who participate in their company's retirement plan. One technique, automatic enrollment, automatically establishes a retirement plan and contribution. You can opt out at any time, but you're enrolled by default. Here's how it affects 401(k) enrollment. (AE = automatic enrollment.)

From 40% participation to nearly 100% in one example. Astonishing. Today, J.D. has given me the opportunity to talk about one of the ways to drive behavioral change when it comes to your money. I call them barriers. While I do this, I'm going to ask you for a favor. You'll see examples of people who lost thousands of dollars because they wouldn't spend one hour reading a form. It's easy to call these people lazy and there's certainly an element of that but disdainfully calling someone lazy doesn't explain the whole story. Getting people to change their behavior is extraordinarily hard even if it will save them thousands of dollars or save their lives. If it were easy, you would have a perfect financial situation: You'd have no debt, your asset allocation would be ideal and rebalanced annually, and you'd have a long-term outlook without worrying about the current economic crisis. You'd be at your college weight, with washboard abs and tight legs. You'd have a clean garage. But you don't. None of us are perfect. That's why understanding barriers is so important to changing your own behavior. Just Spend Less Than You Earn! There's something especially annoying about comments on personal-finance blogs. On nearly every major blog post I ever made, someone left a comment that goes like this: Ugh, not another money tip. All you need to know is: spend less than you earn. Actually, it's not that simple. If that were the case, as I pointed out above, nobody would be in debt, overweight, or have relationship problems of any kind. Simply knowing a high-level fact doesn't make it useful. I studied persuasion and social influence in college and grad school, for example, but I still get persuaded all of the time. These commenters make the common mistake of assuming that people are rational actors, meaning they behave as a computer model would predict. We know this is simply untrue: Books like Freakonomics and Judgment in Managerial Decision Making are great places to get an overview of our cognitive biases and psychological motivations. For example, we say we want to be in shape, but we don't really want to go to the gym. (J.D. is a prime example of this, and he'll be the first to admit it.) We believe we're not affected by advertising, but we're driving a Mercedes or using Tupperware or wearing Calvin Klein jeans. There are dramatic differences in what we say versus what we do. Often, the reason is so simple that we can't believe it would affect us. I call these barriers, and I've written about them before: Last weekend, I went home to visit my family. While I was there, I asked my mom if she would make me some food, so like any Indian mom would, she cooked me two weeks' worth. I came back home skipping like a little girl. Now here's where it gets interesting. When I got back to my place, I took the food out of the brown grocery bag and put the clear plastic bags on the counter. I was about to put the bags in the fridge but I realized something astonishing:

if I got hungry, I'd probably go to the fridge, see the plastic bags, and realize that I'd have to (1) open them up and then I'd have to (2) open the Tupperware to (3) finally get to the food. And the truth was, I just wouldn't do it. The clear plastic bags were enough of a barrier to ignore the fresh-cooked Indian food for some crackers!! Obviously, once I realized this, I tore the bags apart like a voracious wolf and have provided myself delicious sustenance for the past week. I think the source of 95%+ of barriers to success isourselves. It's not our lack of resources (money, education, etc). It's not our competition. It's usually just what's in our own heads. Barriers are more than just excuses they're the things that make us not get anything done. And not only do we allow them to exist around us, we encourage them. There are active barriers and passive barriers, but the result is still the same: We don't achieve what we want to. I believe there are two kinds of barriers. Active barriers are physical things like the plastic wrap on my food, or someone telling me that it'll never work, etc. These are hard to identify, but easy to fix. I usually just make them go away.Passive barriers are things that don't exist, so they make your job harder. A trivial example is not having a stapler at your desk; imagine how many times a day that gets frustrating. For me, these are harder to identify and also harder to fix. I might rearrange my room to be more productive, or get myself a better pen to write with. Today, I want to focus on passive barriers: what they are and how to overcome them. How to Destroy Passive Barriers Psychologists have been studying college students for decades to understand how to reduce unprotected sex. Among the most interesting findings, they pointed out that it would be rational for women to carry condoms with them, since often the sexual experiences they had were unplanned and these women can control the use of contraceptives. Except for one thing. When they asked college women why they didn't carry condoms with them, one young woman typified the responses: I couldn't do thatI'd seem slutty. As a result, she and others often ended up having unprotected sex because of the lack of a condom. Yes, technically they should carry condoms, just as both partners should stop, calmly go to the corner liquor store, and get protection. But often they don't. In this case, the condom was the passive barrier: Because they didn't have it nearby and conveniently available, they violated their own rule to have safe sex. Passive barriers exist everywhere. Let's look at some examples. Passive Barriers in E-mail I get emails like this all the time: Hey Ramit, what do you think of that article I sent last week? Any suggested changes? My reaction? Ugh, what is he talking about? Oh yeah, that article on savings accountsI have to dig that up and reply to him. Where is that? I'll search for it later. Marks email as unread Note: You can yell at me for not just taking the 30 seconds to find his email right then, but that's exactly the point: By not including the article in this followup email, he triggered a passive barrier of me needing to think about what he was talking about, search for it, and then decide what to reply to. The lack of the attached article is the passive barrier, and our most common response to barriers is to do nothing. Passive Barriers on Your Desk A friend of mine lost over $3000 because he didn't cash a check from his workplace, which went bankrupt a few months later. When I asked him why he didn't cash the check immediately, he looked at me and said, I didn't have an envelope handy. What other things do you delay because it's not convenient? Passive Barriers to Exercise I think back to when I've failed to hit my workout goals, and it's often the simplest of reasons. One of the most obvious barriers was my workout clothes. I had one pair of running pants, and after each workout, I would throw it in my laundry basket. When I woke up the next morning, the first thing I would think is: Oh god, I have to get up, claw through my dirty clothes, and wear those sweaty pants again. Once I identified this, I bought a second pair of workout clothes and left them by my door each day. When I woke up, I knew I could walk out of my room, find the fully prepared workout bag and clothes, and get going. Passive Barriers to Healthy Eating Too many people create passive barriers to healthy eating. You're sitting at your desk at work and you get hungry. Rather than reach for a healthy snack (because you don't have one with you a passive barrier), you go to the vending machine for a bag of Cheetos. Here's a real-life example of passive barriers preventing J.D. from eating healthy. We were in Denver together in 2013 for a conference. During a long day with no breaks, he didn't have a healthy snack with him. But he did have Hostess Sno-Balls. Bad J.D. That's not even food.

J.D. needs to remove passive barriers to healthy eating If you find yourself snacking on Cheetos (or Sno-Balls) all day at work, try this: Dont take any spare change in your pockets for the vending machine. Even if you leave quarters in your car, that walk to the parking lot is barrier enough not to do it. Give yourself an alternative. Carry a healthy snack with you, like apple slices. Remove the passive barrier to eating healthy. Applying Passive Barrier Theory to Your Own Life As we've seen, the lack of having something nearby can have profound influences on your behavior. Imagine seeing a complicated mortgage form with interest rates and calculations on over 100 pages. Sure, you should calculate all of it, but if you don't have a calculator handy, the chances of your actually doing it go down dramatically. Now, we're going to dig into areas where passive barriers are preventing you from making behavioral change sometimes without you even knowing it. Fundamentally, there are two ways to address a passive barrier. You're missing something, so you add it to achieve your goals. For example, cutting up your fruit as soon as you bring it home from the grocery store, packing your lunches all at once, or re-adding the attachment to a followup email so the recipient doesn't have to look for it again.Causing an intentional passive barrier by deliberately removing something. You put your credit card in a block of ice in the freezer to prevent overspending. (That's not addressing the cause, but it's immediately stopping the symptom.) Or you put your unhealthiest food on the other side of the house, so you have to walk to them. Or you install software like Freedom to force yourself not to browse Reddit three hours a day. Personally, here are a few passive barriers I've identified (and removed) for myself: I keep my checkbook by my desk, because for the few bills I receive in the mail, I tend to never mail them in. I keep a gym bag of clothes ready to work out. And I cut up my fruit when I bring it home from the store, because I know I'll get lazy later. Now let's see how this can work for you. Here's an exercise I'd like you to do: Get a piece of paper and a pen or open the note-taking app on your phone.Identify ten things you would do if you were perfect. Don't censor. Just write what comes to mind. And focus on actions, not outcomes. Examples: I'd work out four times per week, clean my garage by this Sunday, play with my daughter for 30 minutes each day, and check my spending once per week.Now, play the Five Whys game: Why aren't you doing each of these things? Let's play out the last step with the example of exercising regularly. Let's assume I say that I want to exercise three times per week, but I only go twice per month. Let's do the Five Whys: Why do I excercise only twice per month? Because I'm tired when I get home from work.Why? Because I get home from work at 6 p.m.Why? Because I leave late for work, so I have to put in eight hours.Why? Because I don't wake up in time for my alarm clock.Why? HmmBecause when I get in bed, I watch Netflix for a couple of hours. Here's a possible solution: Put the computer in the kitchen before you go to sleep sleep earlier come home from work at an earlier time feel more rested work out regularly. That's a gross oversimplification, but you see what I mean. Homework: Pick ten areas of your life that you want to improve. Force yourself to understand why you haven't done so already. Don't let yourself cop out: I just don't want to isn't the real reason. And once you find out the real reasons you haven't been able to check your spending, or cook dinner, or call your mom, you might be embarrassed at how simple it really was. Don't let that stop you. Passive barriers are valued in their usefulness, not in how difficult they are to identify. The Bottom Line Passive barriers are subtle factors that prevent you from changing your behavior. Unlike active barriers, passive barriers describe the lack of something, making them more challenging to identify. But once you do, you can immediately take action to change your behavior. You can apply barriers to prevent yourself from spending money, cook and eat healthier, exercise more, stay in touch with your friends and family, and virtually any other behavior. You can do this with small changes or big ones. The important factor is to take action today. A caveat: Sometimes people take this advice to mean, The reason I haven't been sticking to my workout regimen is that I don't have the best running shoes. I should really go buy those $150 shoes I've been eyeingthat will help me change my behavior. Resolving passive barriers is not a silver bullet: Although they help, you'll be ultimately responsible for changing your own behavior. Instead of buying better shoes immediately, I'd recommend setting a concrete goal Once I run consistently for 20 days in a row, I'll buy those shoes for myself before spending on barriers. Most changes can be done with a minimum of expense. J.D.'s note: This is one of my favorite guest articles in the history of Get Rich Slowly. It had a profound effect on me, my life, and my work. This piece was originally published on 17 March 2009. I'm reprinting it today to celebrate the newly-published second edition of Ramit's book, I Will Teach You to Be Rich [my review].

0 notes

Link

The term “one-drop rule”has its own rather curious history. It was used repeatedly in scholarly works on race relations more than a generation ago. Today, it can be found in a wide variety of publications that deal with race relations in the United States. Yet the lexical community has been either negligent or resistant about the term, for as of a very few years ago, allthe purportedly unabridged dictionaries of the English language and their updated collegiate versions did not include it. These dictionaries have begun to catch up as dictionaries and facsimiles like Wikipedia have become ubiquitous online. Even the venerable Oxford English Dictionary, which is supposedly based on historical principles, has an online version that now includes the term. The phrase currently appears in many books, magazines, and on the Internet, firmly supported by its conciseness in referring to a powerful social rule.

African Americans have necessarily had a different experience than whites with this rule. After the Civil War and prior to the mid-1960’s, many people then called “Negroes”—at least those middle-class people who could—adopted white values about complexion and hair, and many older African Americans can still remember battling with chemical lighteners and straighteners. As iswell known, however, with the second civil rights movement, many African Americans embraced Negroid appearance as an emblem of their commitment to that battle. As will become clear, however, this sense of common interest among African Americans is far older than the recent civil rights era, for it first appeared in parts of the American colonies prior to the American Revolution and showed signs of strengthening in the young republic in the years following. Following the more radical years of the late 1960s and 1970s, the pendulum swung back. Since the 1980s African Americans and others have placed substantial value on light coloring, straight hair, and European-derived facial features, to the point where sales of skin and hair products, and even cosmetic surgery, have skyrocketed.

For mixed-race people, individual personal struggles with the color line also have a long history. Frederick Douglass recorded his handling of its difficulties in 1848 while on his way to a Negro convention in Buffalo. After boarding a lake steamer, Douglass accepted a spontaneous invitation by his fellow passengers to give a speech. Afterwards he learned that a certain white passenger had announced his disagreement with a point made by Douglass and had declared that he would not “discuss this question with a nigger.”In response, Douglass passed word to this critic “that he was much mistaken in supposing me to be a nigger, that I was but a half negro—that my Dear Fatherwas as white as himself, and if he could not condescend to reply to negro blood, to reply to the Europeanblood.”In such instances, however, the one-drop rule itself was not in dispute; indeed at times many American blacks have actually reinforced its dominance as a social norm.

Discerning the historical reasons underlying the one-drop rule raises important evidentiary and conceptual problems. The brief explications in this article deal with various facets of the rule in hopes that this discussion will collectively and tentatively suggest why it came into being. One crucial dimension of the one-drop rule is its uniqueness (with a single exception as will become clear). Today, many foreign observers from other parts of the Americas are so differently socialized that they find the rule nearly impossible to understand. We do indeed need to inquire why the rule developed in the United States and not elsewhere in the Caribbean and in Latin America, that is, in other colonies and later in independent nations that were all part of the overall European and African settlement of the New World after Columbus.Another important attribute of this social classification is so obvious that it has often been overlooked, though it needs only a brisk statement here. The rule applies primarily to people of mixed African-European background, and not to other patterns of so-called “racial intermixture.” It does not apply to people whose apparent heritage is confined to some combination of Caucasian, Hispanic, Asian, or Native American ancestry. It applies only to Americans of entirely or partially African descent. Race in the United States has never been just about white and black. But to make the task of this essay manageable, the discussion here will attend mainly to European- and African-descended Americans—the ones on whom the one-drop rule has fallen most heavily.16A far more complex facet of the rule concerns the apparently simple matter of dating its beginnings. Here we run into serious difficulties, primarily because extant references to its existence are uncommon and appear in few widely scattered sources. Indeed this brief study depends on a mere handful of such references, and the likelihood of others having escaped the author’s attention is virtually guaranteed. Color is viewed as the most predominant physiognomic feature of racial distinction. After all, we have been using either a Portuguese/Spanish or an English designation of color—Negro/black—in connection with Africans for many centuries. While differences in hair and facial features are recognized, they are not frequently commented upon in public in the dominant white society; skin color has been and remains the most important social marker, with the configuration of hair, nose width, lips and other features often used as secondary reinforcements. All these markers are facial, a fact that underscores the importance of sheer public appearance in social situations. The anomalies for personal identity resulting from the one-drop rule are apparently never-ending. It has meant our having had a Miss America, Vanessa Williams, who was called “black” even though her ancestry was apparently much more European than African. The same might be said of General Colin Powell, who remains “African American” largely by his own assertion. This particular personal choice is not new: the prominent nineteenth-century abolitionist, Robert Purvis, who was born and raised in South Carolina and moved to Philadelphia. There he was often told that he was light enough to pass for white, but he continued to live as a black man in both his private and public life.19 The complexion and features of actress-model Halle Berry are such that her visually perceived race can vary greatly depending on lighting, makeup, and camera angle. The same rule has also operated with a professional golfer, Tiger Woods, who has mounted a losing personal battle to resist it. His mixed ancestry is Thai, Chinese, American Indian, Dutch, and African American. Yet in this country he has been hailed as “black” throughout his career. Without hesitancy the US media, both white and African American, have described him consistently with such phrases as “the Great Black Hope,” “the first Black to win the U.S. Amateur,” and “a 19-year-old who just happens to be black.” Woods has fought this designation with public objections, by checking “Asian” on his census form, and by inventing his own term—“Cablinasian” (for Caucasian, Black, Indian and Asian). Such battles are very old. Two hundred years after their alleged long-term liaison, the numerous descendants of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson (or possibly one of his male relatives) are today grouped in two categories both by the media and by themselves—the “black” descendants and the “white” ones.

It is also important to recognize that the rule has frequently been violated. There have been a rather small number of isolated local pockets occupied by people who were openly acknowledged to be of two-or three-way intra-mixtures. In more heavily settled areas, sheer reputation has occasionally overridden the rule. The courts at many levels have treated it gingerly and with stunning inconsistency, and state statutes have variously tried to skirt it or to reinforce it with fractional exactitudes that themselves have varied greatly over time. In general, however, the law has tended increasingly either to tighten the rule or to give up trying to define it with a written definition. Nonetheless, the rule has operated socially with a power not seen in any other country, with a revealing exception in the British West Indies that will need our attention. The appalling dissonances in this social system have affected both blacks and whites. Preferences in skin color (as well as hair form) have been and remain so complex for both groups that they can only be summarized here, without more than alluding to the dimensions of gender that so strongly affect their operation. As most Americans are aware, a relatively light complexion has had positive personal and social value, especially among African Americans but also among whites. In many black families and communities, there remain personal biases in favor of lightness, a long-established, flexible set of preferences that have not been entirely destroyed by 1960s–1970s public and personal campaigns summed up by the slogan “black is beautiful.”Nor have whites entirely lost their traditional biases for a light complexion among black people and, indeed, among themselves at least among those still committed to a muted version of old-fashioned Nordicism. Less studied and commented upon is a common but far from universal negative response among AfricanAmericans to whites with very light complexions. Indeed, a great many African Americans are far more sensitive than most whites to gradations in color in all people, and out of necessity for many years they have had to deal with the social rule about race imposed by the dominant culture. For present purposes this paper will avoid these and other complications, for there is danger here of veering off into an exceedingly swampy field of idiosyncratic, elusive, and highly variable valuations, a place long populated by popular magazines, curious social scientists, ambitious advertising agencies, and assorted myth-and trouble-makers, as they all speculate knowingly about such weighty icons as Aunt Jemima, Lady Clairol, and “good”hair.

All these valuations exist within a confined space of social definition. As a pasture of changing ambiguities, they are fenced in rigidly by the one-drop rule. Yet they are far from being the sole aspect of that rule’s dissonant nature. At a theoretical level, the rule unsteadily perches on a rigid and arbitrary dividing line between the social and the biological sciences. Until a century ago, almost everyone assumed that “blood”was the conveyor of physical inheritance. In this genetic age, it is almost astonishing that the term blood has moved back into scholarly discourse when the very people who use it know perfectly well that blood is not the transmitter of inherited characteristics in human or other living beings.

Another anomaly in this concept is more ironic. The conclusions of archeology, paleontology, and evolutionary biology join in the finding that it is highly probable that all human beings are of African descent. The species Homo sapiens originated in the northeastern part of Africa, along the Great Rift Valley, with some possibility of emergence also in the southern regions of the continent. Those parts of the continent were no more the direct cradles of African Americans than of Euro-Americans or Native Americans, since only a small number of the people living in eastern and southern Africa were caught up in the Atlantic slave trade that began in the sixteenth century. Except in the very early years of the trade, almost all the forced migrants from Africa to the Americas originally came from the western portions of the African continent, a huge expanse of coastal and near-coastal regions that stretched for some three thousand miles from the Sahara desert in the north to the Namibian desert in the south. Only a small proportion—some five percent—came from homelands onthe huge island of Madagascar and along the southeastern African coast. Yet if one goes back far enough in time, all Americans, including the first settlers from Asia whom Columbus called “Indians”and the more numerous later immigrants from Africa, Europe, and Asia, may also be accurately described as being—very distantly in time—“of African descent.”

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 15.0px 0.0px; line-height: 16.0px; font: 14.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #343434; -webkit-text-stroke: #343434} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} — Winthrop Jordan

https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91g761b3

#mixed race#critical race theory#critical theory#black history#one drop#one drop rule#racism#antiblackness#anti blackness#antiblack#anti black#desirability#desirability politics#african american

0 notes

Text

The psychology of passive barriers

A surprising thing happens to people in their forties. After working hard, buying a house, and starting a family, they suddenly realize that they'd better start being responsible with their money. They begin reading financial books and trying to learn how to set up a nest egg for themselves and their families. It's a natural part of growing older.

If you ask these people in their forties what their biggest life worry, the answer often is, quite simply, “money”. They want to learn to manage their money better, and they'll tell you how important financial stability is to them.

Yet the evidence shows something very different.

In the table below, researchers followed employees at companies that offered financial-education seminars. Despite the obvious need to learn about their finances, only 17% of company employees attended. This is a common phenomenon.

As Laura Levine of the Jump$tart Coalition told me — and I paraphrase — “Bob doesn't want to attend his 401(k) seminar because he's afraid he'll see his neighbor there…and that would be equivalent to admitting he didn't know about money for all those years.”

They also don't like to attend personal-finance events because they don't like to feel bad about themselves. But of those who did attend the employer event, something even more surprising happens.

Of the people who did not have a 401(k), 100% planned to enroll in their company's 401(k) offering after the seminar. Yet only 14% actually did.

Of those who already had a 401(k), 28% planned to increase their participation rate. 47% planned to change their fund selection (most likely because they learned they had picked the default money-market plan, which was earning them virtually nothing). But less than half of people actually made the change.

This is the kind of data that drives economists and engineers crazy, because it clearly shows that people are not rational. Yes, we should max out our 401(k) employer match, but billions of dollars are left on the table each year because we don't. Yes, we should start eating healthy and exercising more, but we don't.

Why not? Why wouldn't we do something that's objectively good for us?

Barriers are one of the implicit reasons you can't achieve your goals. These barriers can be psychological or profoundly physical, like something as simple as not having a pen when you need to fill out a form. But the underlying factor is that they are breathtakingly simple — and if I pointed them out to you about someone else, you would be sickened by how seemingly obvious they are to overcome.

It's easy to dismiss these barriers are trivial, and say, “Oh, that's so dumb!” when you realize that not having an envelope nearby could cost someone over $3,000. But it's true. And by the end of this article, you'll be able to identify at least three barriers in your own life — whether you want to or not.

Why People Don't Participate in Their 401(k)s

If you're like me, whenever you hear that one of your co-workers doesn't participate in their 401(k) — especially if there's an employer match — you scratch your head in confusion.

Even though this is free money, many people still don't participate. Journalists will cite intangibles like laziness and personal responsibility, suggesting that people are getting less responsible with their money over time. Hardly.

It turns out that getting people to enroll in their 401(k) is just plain hard. Using simple psychological techniques, however, we can dramatically increase the number of people who participate in their company's retirement plan. One technique, automatic enrollment, automatically establishes a retirement plan and contribution. You can opt out at any time, but you're enrolled by default.

Here's how it affects 401(k) enrollment. (“AE” = automatic enrollment.)

From 40% participation to nearly 100% in one example. Astonishing.

Today, J.D. has given me the opportunity to talk about one of the ways to drive behavioral change when it comes to your money. I call them barriers.

While I do this, I'm going to ask you for a favor. You'll see examples of people who lost thousands of dollars because they wouldn't spend one hour reading a form. It's easy to call these people “lazy” — and there's certainly an element of that — but disdainfully calling someone lazy doesn't explain the whole story. Getting people to change their behavior is extraordinarily hard — even if it will save them thousands of dollars or save their lives.

If it were easy, you would have a perfect financial situation: You'd have no debt, your asset allocation would be ideal and rebalanced annually, and you'd have a long-term outlook without worrying about the current economic crisis. You'd be at your college weight, with washboard abs and tight legs. You'd have a clean garage.

But you don't.

None of us are perfect. That's why understanding barriers is so important to changing your own behavior.

“Just Spend Less Than You Earn!”

There's something especially annoying about comments on personal-finance blogs. On nearly every major blog post I ever made, someone left a comment that goes like this: “Ugh, not another money tip. All you need to know is: spend less than you earn.”

Actually, it's not that simple. If that were the case, as I pointed out above, nobody would be in debt, overweight, or have relationship problems of any kind. Simply knowing a high-level fact doesn't make it useful. I studied persuasion and social influence in college and grad school, for example, but I still get persuaded all of the time.

These commenters make the common mistake of assuming that people are rational actors, meaning they behave as a computer model would predict. We know this is simply untrue: Books like Freakonomics and Judgment in Managerial Decision Making are great places to get an overview of our cognitive biases and psychological motivations.

For example, we say we want to be in shape, but we don't really want to go to the gym. (J.D. is a prime example of this, and he'll be the first to admit it.) We believe we're not affected by advertising, but we're driving a Mercedes or using Tupperware or wearing Calvin Klein jeans.

There are dramatic differences in what we say versus what we do. Often, the reason is so simple that we can't believe it would affect us. I call these barriers, and I've written about them before:

Last weekend, I went home to visit my family. While I was there, I asked my mom if she would make me some food, so like any Indian mom would, she cooked me two weeks' worth. I came back home skipping like a little girl.

Now here's where it gets interesting. When I got back to my place, I took the food out of the brown grocery bag and put the clear plastic bags on the counter. I was about to put the bags in the fridge but I realized something astonishing:

…if I got hungry, I'd probably go to the fridge, see the plastic bags, and realize that I'd have to (1) open them up and then I'd have to (2) open the Tupperware to (3) finally get to the food. And the truth was, I just wouldn't do it. The clear plastic bags were enough of a barrier to ignore the fresh-cooked Indian food for some crackers!!

Obviously, once I realized this, I tore the bags apart like a voracious wolf and have provided myself delicious sustenance for the past week.

I think the source of 95%+ of barriers to success is…ourselves. It's not our lack of resources (money, education, etc). It's not our competition. It's usually just what's in our own heads. Barriers are more than just excuses — they're the things that make us not get anything done. And not only do we allow them to exist around us, we encourage them. There are active barriers and passive barriers, but the result is still the same: We don't achieve what we want to.

I believe there are two kinds of barriers.

Active barriers are physical things like the plastic wrap on my food, or someone telling me that it'll never work, etc. These are hard to identify, but easy to fix. I usually just make them go away.

Passive barriers are things that don't exist, so they make your job harder. A trivial example is not having a stapler at your desk; imagine how many times a day that gets frustrating. For me, these are harder to identify and also harder to fix. I might rearrange my room to be more productive, or get myself a better pen to write with.

Today, I want to focus on passive barriers: what they are and how to overcome them.

How to Destroy Passive Barriers

Psychologists have been studying college students for decades to understand how to reduce unprotected sex. Among the most interesting findings, they pointed out that it would be rational for women to carry condoms with them, since often the sexual experiences they had were unplanned and these women can control the use of contraceptives.

Except for one thing.

When they asked college women why they didn't carry condoms with them, one young woman typified the responses: “I couldn't do that…I'd seem slutty.” As a result, she and others often ended up having unprotected sex because of the lack of a condom. Yes, technically they should carry condoms, just as both partners should stop, calmly go to the corner liquor store, and get protection. But often they don't.

In this case, the condom was the passive barrier: Because they didn't have it nearby and conveniently available, they violated their own rule to have safe sex.

Passive barriers exist everywhere. Let's look at some examples.

Passive Barriers in E-mail

I get emails like this all the time:

“Hey Ramit, what do you think of that article I sent last week? Any suggested changes?”

My reaction? “Ugh, what is he talking about? Oh yeah, that article on savings accounts…I have to dig that up and reply to him. Where is that? I'll search for it later. Marks email as unread”

Note: You can yell at me for not just taking the 30 seconds to find his email right then, but that's exactly the point: By not including the article in this followup email, he triggered a passive barrier of me needing to think about what he was talking about, search for it, and then decide what to reply to. The lack of the attached article is the passive barrier, and our most common response to barriers is to do nothing.

Passive Barriers on Your Desk

A friend of mine lost over $3000 because he didn't cash a check from his workplace, which went bankrupt a few months later. When I asked him why he didn't cash the check immediately, he looked at me and said, “I didn't have an envelope handy.” What other things do you delay because it's not convenient?

Passive Barriers to Exercise

I think back to when I've failed to hit my workout goals, and it's often the simplest of reasons. One of the most obvious barriers was my workout clothes. I had one pair of running pants, and after each workout, I would throw it in my laundry basket. When I woke up the next morning, the first thing I would think is: “Oh god, I have to get up, claw through my dirty clothes, and wear those sweaty pants again.”

Once I identified this, I bought a second pair of workout clothes and left them by my door each day. When I woke up, I knew I could walk out of my room, find the fully prepared workout bag and clothes, and get going.

Passive Barriers to Healthy Eating

Too many people create passive barriers to healthy eating. You're sitting at your desk at work and you get hungry. Rather than reach for a healthy snack (because you don't have one with you — a passive barrier), you go to the vending machine for a bag of Cheetos.

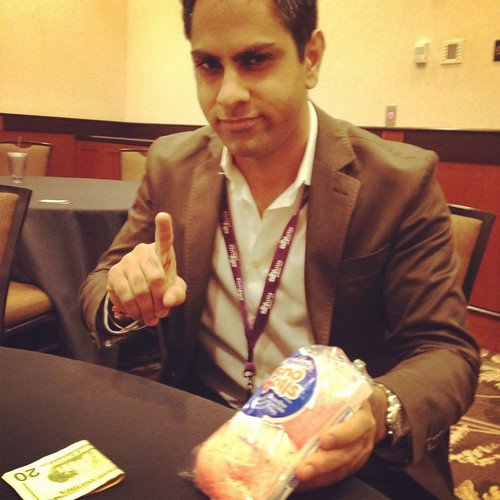

Here's a real-life example of passive barriers preventing J.D. from eating healthy. We were in Denver together in 2013 for a conference. During a long day with no breaks, he didn't have a healthy snack with him. But he did have Hostess Sno-Balls. Bad J.D. That's not even food.

J.D. needs to remove passive barriers to healthy eating

If you find yourself snacking on Cheetos (or Sno-Balls) all day at work, try this: Don’t take any spare change in your pockets for the vending machine. Even if you leave quarters in your car, that walk to the parking lot is barrier enough not to do it. Give yourself an alternative. Carry a healthy snack with you, like apple slices. Remove the passive barrier to eating healthy.

Applying Passive Barrier Theory to Your Own Life

As we've seen, the lack of having something nearby can have profound influences on your behavior. Imagine seeing a complicated mortgage form with interest rates and calculations on over 100 pages. Sure, you should calculate all of it, but if you don't have a calculator handy, the chances of your actually doing it go down dramatically.

Now, we're going to dig into areas where passive barriers are preventing you from making behavioral change — sometimes without you even knowing it.

Fundamentally, there are two ways to address a passive barrier.

You're missing something, so you add it to achieve your goals. For example, cutting up your fruit as soon as you bring it home from the grocery store, packing your lunches all at once, or re-adding the attachment to a followup email so the recipient doesn't have to look for it again.

Causing an intentional passive barrier by deliberately removing something. You put your credit card in a block of ice in the freezer to prevent overspending. (That's not addressing the cause, but it's immediately stopping the symptom.) Or you put your unhealthiest food on the other side of the house, so you have to walk to them. Or you install software like Freedom to force yourself not to browse Reddit three hours a day.

Personally, here are a few passive barriers I've identified (and removed) for myself: I keep my checkbook by my desk, because for the few bills I receive in the mail, I tend to never mail them in. I keep a gym bag of clothes ready to work out. And I cut up my fruit when I bring it home from the store, because I know I'll get lazy later.

Now let's see how this can work for you. Here's an exercise I'd like you to do:

Get a piece of paper and a pen — or open the note-taking app on your phone.

Identify ten things you would do if you were perfect. Don't censor. Just write what comes to mind. And focus on actions, not outcomes. Examples: “I'd work out four times per week, clean my garage by this Sunday, play with my daughter for 30 minutes each day, and check my spending once per week.”

Now, play the “Five Whys” game: Why aren't you doing each of these things?

Let's play out the last step with the example of exercising regularly. Let's assume I say that I want to exercise three times per week, but I only go twice per month. Let's do the Five Whys:

Why do I excercise only twice per month? Because I'm tired when I get home from work.

Why? Because I get home from work at 6 p.m.

Why? Because I leave late for work, so I have to put in eight hours.

Why? Because I don't wake up in time for my alarm clock.

Why? Hmm…Because when I get in bed, I watch Netflix for a couple of hours.

Here's a possible solution: Put the computer in the kitchen before you go to sleep → sleep earlier → come home from work at an earlier time → feel more rested → work out regularly.

That's a gross oversimplification, but you see what I mean.

Homework: Pick ten areas of your life that you want to improve. Force yourself to understand why you haven't done so already. Don't let yourself cop out: “I just don't want to” isn't the real reason. And once you find out the real reasons you haven't been able to check your spending, or cook dinner, or call your mom, you might be embarrassed at how simple it really was. Don't let that stop you. Passive barriers are valued in their usefulness, not in how difficult they are to identify.

The Bottom Line

Passive barriers are subtle factors that prevent you from changing your behavior. Unlike “active” barriers, passive barriers describe the lack of something, making them more challenging to identify. But once you do, you can immediately take action to change your behavior.

You can apply barriers to prevent yourself from spending money, cook and eat healthier, exercise more, stay in touch with your friends and family, and virtually any other behavior. You can do this with small changes or big ones. The important factor is to take action today.

A caveat: Sometimes people take this advice to mean, “The reason I haven't been sticking to my workout regimen is that I don't have the best running shoes. I should really go buy those $150 shoes I've been eyeing…that will help me change my behavior.”

Resolving passive barriers is not a silver bullet: Although they help, you'll be ultimately responsible for changing your own behavior. Instead of buying better shoes immediately, I'd recommend setting a concrete goal — “Once I run consistently for 20 days in a row, I'll buy those shoes for myself” — before spending on barriers. Most changes can be done with a minimum of expense.

J.D.'s note: This is one of my favorite guest articles in the history of Get Rich Slowly. It had a profound effect on me, my life, and my work. This piece was originally published on 17 March 2009. I'm reprinting it today to celebrate the newly-published second edition of Ramit's book, I Will Teach You to Be Rich [my review].

The post The psychology of passive barriers appeared first on Get Rich Slowly.

from Finance https://www.getrichslowly.org/passive-barriers/ via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

[Ilya Somin] Kavanaugh and Executive Power - the Good, the Bad, and the Overblown

Much of the debate over Judge Brett Kavanaugh's nomination to the Supreme Court focuses on his view of executive power. But the discussion here actually encompasses four separate issues: the question of when a sitting president can be investigated and tried for possible violations of criminal and civil law, judicial deference to executive branch agencies' interpretations of law, judicial deference on national security issues, and the theory of the "unitary executive." It is important to address each of these issues separately, because Kavanaugh's positions have very different implications for them. In my view, concern on the first issue is overblown, and Kavanaugh is actually likely to help constrain executive overreach on the second. On the other hand, there is good reason to worry about his record on national security and the unitary executive.

I. The Overblown.

Many Democrats fear that Kavanaugh might cast votes in favor of neutering the Mueller investigation of Donald Trump's possible collusion with Russia during the 2016 campaign, and investigations of other types of wrongdoing by Trump and his associates. It is indeed true that in a 2009 Minnesota Law Review article, Kavanaugh argued that Congress should pass a statute shielding the president from investigation and prosecution until after he has left office, because "we should not burden a sitting President with civil suits, criminal investigations, or criminal prosecutions." But as, Harvard law professor Noah Feldman and Benjamin Wittes of the Brookings Institution explain, liberal fears are likely misplaced. And neither of them, to put it mildly, are fans of Trump. The fact that Kavanaugh argued that a congressional statute would be needed to shield the president from investigation (and possibly even prosecution) suggests that he does not believe that the Constitution forbids such investigations in and of itself. Unless and until Congress enacts the type of statute Kavanaugh advocates (which seems unlikely to happen anytime soon), he would likely vote to allow Mueller to continue his investigation, and the same for other investigations into wrongdoing by Trump.

For what it is worth, I do not agree that the sort of sweeping immunity statute Kavanaugh advocates is a good idea. There is a solid case for postponing investigations into petty illegality by the president. If, for example, evidence indicates that the president smoked a marijuana joint or committed some minor violation of tax law, there may be good reason to avoid burdening him with investigation and prosecution until he leaves office. The situation is very different in cases where he may have committed a serious violation of the law, especially one that undermines constitutional constraints on government power, or threatens national security. I am not convinced that it is safe to rely solely on impeachment as the sole remedy for such wrongdoing, until the president leaves office. But, be that as it may, this is a disagreement about policy, not about the dictates of the Constitution.

Kavanaugh's support for unitary executive theory (discussed more fully below) could potentially lead him to conclude that Mueller's appointment as special counsel is unconstitutional. But, for reasons Wittes explains, that is unlikely, because Mueller's authority is constrained in ways that fit what Kavanaugh himself has advocated in the past. Moreover, as prominent conservative lawyer George Conway (ironically, also known for being the husband of Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway) has explained, the Mueller investigation is constitutional even under a very rigorous application of unitary executive theory, because Mueller is subject to control and removal by his superiors in the Justice Department. The question of the legality of Mueller's investigation may never reach the Supreme Court. But if it does, I think there is little reason to think Kavanaugh would vote to immunize Trump from further investigation.

II. The Good.

On the issue of Chevron deference, Kavanaugh's skepticism of judicial deference to executive agencies' interpretation of law might very well help constrain abuses of executive power. The 1984 Chevron decision states that courts must defer to agency interpretations of federal law in most cases where the law is ambiguous, and the agency's view of its meaning is "reasonable," which in practice is often a very low standard. In a 2016 Harvard Law Review article, Kavanaugh argued that, "[i] many ways, Chevron is nothing more than a judicially orchestrated shift of power from Congress to the Executive Branch" and that it encourages the executive to play fast and loose with the law because its "inherent aggressiveness is amped up significantly" by the expectation of judicial deference. He fears that "executive branch agencies often think they can take a particular action unless it is clearly forbidden." For reasons discussed here (in analyzing Justice Neil Gorsuch's similar views), I largely agree.

Kavanaugh's concerns about Chevron echo those recently expressed by Justice Anthony Kennedy; so his elevation to the Court may not change the balance on this issue much. Chevron deference has also begun to attract skepticism from many judges across the political spectrum. Cutting back on judicial deference to agencies has obvious appeal to conservative and libertarian critics of the administrative state. But it should also appeal to liberals who fear that Republican agency heads are likely to be ideologically biased, and bend the law to their own preferences. See, for example, this praise of Kavanaugh's critique of Chevron by prominent liberal legal scholar Jed Shugerman. Cutting back Chevron could also help strengthen the rule of law in ways that should appeal to people with a wide range of political preferences. As Neil Gorsuch put it in a well-know opinion written when he was a lower court judge, judicial deference to executive agencies allows the latter to "reverse its current view 180 degrees anytime based merely on the shift of political winds and still prevail [in court]." Surely there's something wrong with that.

It unlikely that Kavanaugh's confirmation would lead to the complete overruling of Chevron. But it would likely continue - and perhaps accelerate - the trend towards tighter, and less deferential judicial review of agency decisions.

III. The Seriously Problematic.

Kavanaugh's record on judicial deference to the executive on national security issues is far less reassuring. As legal scholar Stephen Vladeck explains in the Washington Post, he has extended broad deference in several cases dealing with the rights of Guantanamo detainees. In that respect, Vladeck emphasizes, he is very different from Justice Kennedy, who was much more willing to enforce legal limits on executive national security policy. Kavanaugh's deferential attitude may also come through in his concurring opinion to the DC Circuit's denial of en banc review of a decision upholding the NSA's collection of a vast amount of "bulk data" from American electronic cell phone records. While some of Kavanaugh's reasoning was based on direct application of Supreme Court precedent, he also emphasized that "[t]he Government's program for bulk collection of telephony metadata serves a critically important special need – preventing terrorist attacks on the United States.... In my view, that critical national security need outweighs the impact on privacy occasioned by this program." This argument implies that other national security justifications might well also qualify as "special needs" that justify searches that would otherwise violate the Fourth Amendment.

Wide-ranging judicial deference on national security cases is not justified by the text of the Constitution. Unlike some other constitutions, ours has very little in the way of "emergency powers" provisions that diminish or cancel out constitutional rights in time of war or other national security threats. The major exception is the power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, which has not been invoked in any of our current conflicts. The standard expertise-based arguments for special judicial deference are seriously flawed, and have led to severe abuses in the past.

The other area where Kavanaugh's views on executive power are potentially troubling is his support of "unitary executive" theory - the idea that the Constitution requires nearly all executive power to be concentrated in the hands of the president. I used to support this view myself. But I now believe I was wrong to do so. Unitary executive theory was sound in a period where the scope of executive power was confined to its comparatively narrow original bounds. But, for reasons I summarized here, it is both dangerous and contrary to the original meaning to concentrate so much authority in one person's hands in an era when the executive wields vastly greater power than was granted to the federal government in the original Constitution.

Judge Kavanaugh's views on national security deference and the unitary executive are well within the mainstream of modern legal thought. He is no wild-eyed radical, or partisan apologist for Trump. His controversial opinions on national security issues actually came in cases challenging Obama administration policies.

But the fact that these ideas are mainstream is not as comforting as it may seem. Historically, most of the worst Supreme Court decisions came about precisely because mainstream legal thought went wrong on some important issue - not because the justices who voted for them were fools or extremists. A misguided "mainstream" is far more dangerous than the occasional fluky extremist ruling. When it comes to national security and the unitary executive, Kavanaugh is an especially thoughtful and articulate defender of positions on which mainstream conservative jurisprudence has gone wrong.

The fact that he may be wrong about these two questions doesn't necessarily mean he would be an undesirable Supreme Court justice,overall. Kavanaugh's flaws here should be weighed against his excellent record on many other issues, such as his strong support for freedom of speech. At this point in our history, neither Republicans nor Democrats are likely to give us an ideal Supreme Court justice who gets every important issue right. Very far from it, in fact. We could easily do far worse than Kavanaugh, who is a very solid choice in many ways. Still, Judge Kavanaugh's positions on executive power are an important aspect of his overall record, and they deserve serious scrutiny.

0 notes

Link