#but no nation state has rights and especially none that prioritize its own existence over indigenous people's lives

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

everyday for the past two months it's been waking up in the morning to the most horrifying war crimes being committed by a fascist colonial power run by a death cult, followed by said power fabricating the most offensive and easily debunked lies to excuse said war crimes, then the entire fucking world media believing them and waving around their pathetic little crocodile tears as i pass by the news that the soldiers of that world power shot an old woman in the entrance of a hospital and used her as bait to shoot any medic who tried helping her, followed by a video of parents looking through the charred remains of children's limbs and scalps trying to recognize their own. and then i go to brazilian TV and find the news that a brazilian palestinian has finally been able to leave Gaza and all the reporters wanna focus on is how they're probably a terrorist because of these posts from 2015 where they condemn israel's actions. and then i look at the presidents of the only few nations who have the power to stop this genocide with a single phone call and how they entirely refuse to do shit about it, just to be told on tumblr dot com that praying for the dismantlement of the state of israel is evil and inconsiderate because don't you know they suffered really really badly in the past (but also please don't google the rates of poverty of holocaust survivors and how they're treated by the government of the country that was supposed to be a safe haven. well at least george from pennsylvania can move and have a beautiful view of the burned olive tress from the multigenerational house he stole in the west bank, and isn't THAT what really matters)

#anyways today's lie was the israeli government posting a picture of a kurdish woman who had been raped and killed in may 2023#claiming it is a israeli woman from oct 7#meanwhile they ravage Al Shifa hospital because there are terrorist bases there guys trust us!!!!!#they're right behind these premature babies suffocating because the incubators have no more energy!!!!!#just one more group of terrorist guys and we'll be fine and have peace forever!!!!!!#god what a bunch of ghouls#and western powers are gladly funding this shit#but nooooo don't call for a free palestine don't u know it's actually a call for genocide 🥺 unlike whatever we are doing in gaza#godddd#fuck the US fuck France fuck Germany fuck Russia and FUCK ISRAEL 🖕🖕🖕#''right to defend itself'' babygirl you don't even have a right to exist. your PEOPLE have a right to exist and feel safe like all others#but no nation state has rights and especially none that prioritize its own existence over indigenous people's lives

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fighting Voter Suppression in Hog Country, North Carolina

A voter waits in line a polling place in Black Mountain, North Carolina | Photo by Brian Blanco/Getty Images

In an election like none before it, the residents of North Carolina’s hog- and poultry-intensive eastern counties are fighting to regain the power of their vote

This story was originally published on Civil Eats.

Elsie Herring spends many days documenting and responding to complaints from her neighbors — about everything from the stench coming off of factory farms to the clearcutting of trees for timber to the emissions from nearby factories. But lately, when Herring, a community organizer for the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (EJN), gets a call, she’s also been making sure the person on the other end of the line has a plan in place to vote.

With almost two million swine within its borders, Herring’s native Duplin County in eastern North Carolina is the top hog-producing county in the United States. And because many residents have pre-existing health conditions, in part from living alongside the waste produced by so many animals, many are choosing to mail their ballots in this year rather than venture to the polls, where COVID-19 presents an additional threat.

But, in a part of the state home to many people of color, Herring worries about reports of minority ballot rejection rates. In North Carolina, the ballots of white voters are being rejected at a rate of .5 percent, while Black voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 1.8 percent rate and Native American voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 4 percent rate (eight times more than white voters’), according to October 21 data from the U.S. Elections Project.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other.

“They’re disproportionate, and right there, that tells me they’re trying to suppress the Black votes,” Herring says. “That has always been their focus, to suppress our vote and not allow us the right.”

And so, she carefully walks her neighbors through the mail-in voting process: “We’re telling them to be careful and aware of what they’re writing and not writing on their ballots. The witness name has to be printed, and you have to have their signature and address. If that’s not there, they kick it out.”

Herring’s fears about the suppression of minority votes are not ill-founded, given recent and long-term efforts in North Carolina. Over the last decade, the state’s General Assembly, which the Republican party has controlled since 2010, has gerrymandered voting district maps along racial lines and passed numerous laws aimed at making it harder for minorities to vote (though many of the measures have not held up in court and are no longer in place).

In the midst of these ongoing efforts, many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities in the eastern part of the state say they’ve repeatedly watched as their elected officials promote the interests of hog and poultry companies over their safety and well-being — as evidenced by the number and density of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) permitted in their communities and the ineffectiveness of the facilities’ waste-disposal systems.

In addition to enabling the industry to concentrate around low-income communities of color, residents say state lawmakers have limited the tools those communities once had at their disposal to protest the resulting pollution.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other: Without people in office to protect their interests, polluting industries such as the state’s industrial hog and poultry operations proliferate and remain largely unchecked, Herring says. And when industries pollute with little consequence, damaging the health and quality of life of the people around them, people are less likely to prioritize getting to the polls, especially given the fact that many are already dealing with myriad other issues, including poverty, food and housing insecurity, and lack of quality education and access to healthcare.

“It’s particularly troubling that when someone who is harmed by all these cumulative impacts seeks to remedy that . . . they find [that] the legislature in recent years has taken very intentional steps to deprive them of long-available remedies,” says Will Hendrick, staff attorney and manager of the Waterkeeper Alliance’s North Carolina Pure Farms, Pure Waters campaign.

“The reaction is, ‘My vote won’t matter — corporations control everything, and that won’t change.’”

Sherri White-Williamson, who worked for years in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office for Environmental Justice before returning two years ago to her hometown in Sampson County, says she has tried to encourage young people in her town to vote. “The reaction is, ‘Why should I? My vote won’t matter — they [corporations] control everything, and that won’t change,’” says White-Williamson, who now works as the NC Conservation Network’s environmental justice policy director. “People who live in communities and get stuff dumped on them feel less empowered to be able to effect any change.”

As a swing state that voted for Barack Obama in 2008, Mitt Romney in 2012, and Donald Trump in 2016, North Carolina will be pivotal in this election. The U.S. Senate race between Republican incumbent Thom Tillis and his Democratic challenger Cal Cunningham could affect which party controls Congress as well. And while there are many conservative parts of the state, the demographics are changing as metropolitan areas continue to grow and more Latinx and young people register to vote.

Despite the factors stacked against them — made worse by the pandemic — Herring says many people in eastern North Carolina are still determined to make their voices heard. This year, groups like the one she’s involved with are working to educate voters and ensure they have transportation to the polls. And while Herring’s biggest concern is that her community’s votes will be under attack, she asks: “What can we do to combat that? I don’t know, other than just showing up at the polls to bring about a change.”

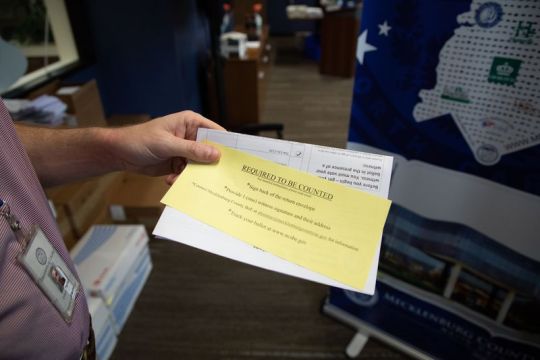

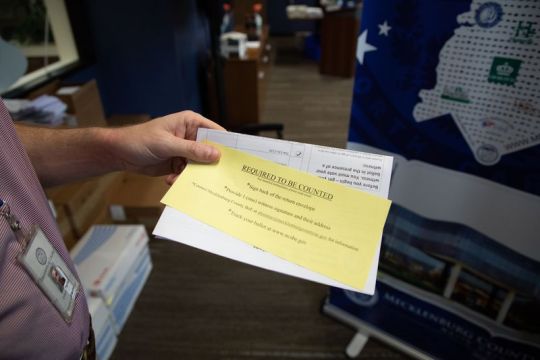

Photo by Logan Cyrus/AFP via Getty Images

An employee of the Mecklenburg County Board of Election in Charlotte, North Carolina holds up instructions that are mailed with absentee ballots for the 2020 election.

Suppressing the vote

In 2011, Republicans gained control of both of North Carolina’s Congressional houses and redrew the legislative district maps in the once-a-decade redistricting process to favor their party. In 2017, a district court and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the maps were illegally racially gerrymandered, meant to dilute the voice of Black voters. Two years after lawmakers submitted new maps, federal judges struck down the voting districts again, this time as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, saying they had been drawn with “surgical precision” — and were among the most manipulated in the nation. Lawmakers were ordered a second time to redraw the maps, which will be redone yet again in 2021, based on the 2020 Census.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in the state have made two other attempts at passing voter suppression laws. HB 589, one of the most dramatic voting rights rollbacks in the U.S., was overturned in federal court after it had been in effect for several years, and the voter ID requirement HB 1092 was blocked by a federal judge.

“There are a lot of different ways people are trying to cut back who is eligible to vote, whose votes count after they are cast, and who is going to feel comfortable voting,” says Kat Roblez, staff attorney with Forward Justice, a nonpartisan organization advancing racial, social, and economic justice in the South. In the Old North State — and nationwide — these tactics commonly include in-person voter intimidation at the polls, periodic purges of voter rolls, the spread of misinformation, voter ID requirements, and felony disenfranchisement laws, she says.

This year, the pandemic and the divisive nature of politics bring additional concerns. While in 2016, about 25 percent of total votes were cast by mail, this year that portion will be almost twice that, according to the Pew Research Center — and voting in a new way comes with its own complications. “It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion,” says Roblez. At the same time, many residents have concerns about the effectiveness of the postal service itself, prompted by budget cuts and policy changes put in place over the summer.

“It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion.”

The increased number of demonstrations by white supremacist and neo-Confederate groups is also worrisome, Roblez says. “What we’re most concerned about in some of the more rural areas is . . . Confederate parades coming to the polls,” she says, recalling how last February, demonstrators hung Confederate flags at a polling site in Alamance County, North Carolina.

Social distancing requirements will also necessitate larger polling places, which can put rural precincts, with less infrastructure available, at a disadvantage. “In an instance where a bigger polling location is needed, they might close two others that are smaller, but that [new] location may not be as accessible,” explains Joselle Torres of Democracy NC.

White-Williamson remembers seeing voter suppression growing up in Sampson County — a particular business owner showing up at the polls to confuse and discourage Black voters, for example — but she hasn’t been aware of polling-place suppression efforts in recent years.

Still, she could see it happening this year. George Floyd was originally from Clinton, the town where she lives, and after his murder at the hands of a white police officer in May, protestors pulled down the Confederate statue in front of the Sampson County courthouse, sparking heated public debates.

“There are a lot of things fresh on people’s minds,” she says. “As a Republican county, I see the potential for there to be efforts at polling places to discourage voting, like what we’re seeing around the country.”

Jeff Currie, a member of the Lumbee Tribe who works as a riverkeeper protecting the Lumber River watershed, believes the poor education system in low-income parts of the state also has a role to play in the area’s disenfranchisement.

“If the education system is not saying ‘vote,’ people don’t understand what voting is — they lack civics training and education and the cultural sense that that’s what you do,” he says.

As Election Day approaches, Democracy NC and Forward Justice are placing volunteer vote protectors at polling places across the state who “are ready and trained to sound the alarm” if they see signs of suppression, adds Torres.

Chuck Liddy/Raleigh News & Observer/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

A pig at Silky Pork Farms in Duplin County, North Carolina

Corporations over constituents

While legislators have tried to limit voting, the hog and chicken industries in eastern North Carolina have grown exponentially in ways that damage their surroundings, residents say. In the 1970s, family farmers in North Carolina raised an average of 60 pigs per farm, and the animals were free to roam around outside. That began to change in the 1980s and ’90s, however, as state lawmakers like teacher and farmer Wendell Murphy sponsored and helped pass bills that shielded large-scale hog farms from local zoning regulations and gave the industry subsidies and tax exemptions.

Now, North Carolina ranks second in the country for the number of hogs it produces, and the state’s average hog farm houses more than 4,000 animals. The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties — the top two hog-producing counties in the country — produce 4 billion gallons of wet waste a year, making up 40 percent of the North Carolina’s total. The waste is stored in open-air pits and periodically sprayed on nearby fields.

The foul-smelling chemicals the facilities release — ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, in particular — have been associated with difficulty breathing, blood pressure spikes, increased stress and anxiety, and decreased quality of life. Additionally, a 2018 study found higher death rates of all studied diseases — including infant mortality, mortality due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia — among communities located near hog CAFOs.

The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties produce 4 billion gallons of waste a year. The waste is stored in open-air pits.

For years, residents have spoken out about their suffering. They’ve told their representatives that the odor from the facilities forces them indoors all the time; they can’t sit on their porches, play in their yards, open their windows, or hang their laundry on the line; they have to buy bottled water rather than drinking from their wells; and “dead boxes” containing pig carcasses line the roads, and buzzards, flies, gnats fill the air.

And yet, says Naeema Muhammad, organizing co-director of the NC EJN, the state legislators and regulatory agencies don’t listen — and repeatedly prioritize large corporations as they make decisions about the permitting and regulation of these facilities. Time after time, she says, “legislators pass bills unmistakably against their constituents, in favor of the industry.”

In 2013, 500 residents of eastern North Carolina filed nuisance suits against the Chinese-owned Smithfield subsidiary Murphy-Brown, LLC, which owns the majority of the hogs in the state, complaining of the health problems and unpleasant ills the company subjected them to. In a victory for the hog-farm neighbors, juries ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the first five of the more than 20 cases to be tried, awarding the 10 plaintiffs in the first lawsuit more than $50 million in damages. (This number was reduced to a total of $3.25 million due to the state’s punitive-damages cap.) The industry is currently appealing the ruling.

As these lawsuits worked their way through the justice system, though, Herring watched in horror as her county’s representative in the state legislature, Jimmy Dixon, sponsored a bill that tied the hands of disadvantaged people looking for protection from factory farm pollution. The bill, passed in 2017, limits the compensation plaintiffs can receive in civil suits like the Smithfield case to a sum related to the diminished value of their property, and prevents them from receiving damages related to health, quality of life, and lost income.

Dixon, who did not respond to a request for comment in this story, said the bill was designed to protect farmers from the “greedy” lawyers who would sue them. “This bill is designed to protect 50,000 hardworking North Carolina farmers who are feeding a hungry world,” Dixon wrote in a 2017 op-ed in The Raleigh News & Observer.

In 2018, Senator and farmer Brent Jackson sponsored a similar bill that practically eliminates the right of residents to sue industrial hog operations by declaring that agricultural operations cannot be considered nuisances if they employ practices generally accepted in the region (like spraying hog waste on fields, for example). “With Senate Bill 711 on the books, we don’t have a leg to stand on,” Herring says. “We have to take what they give us, and [we don’t] have an avenue for recourse.”

Though legislators say they have the interests of farmers and consumers in mind, Muhammad thinks it’s more about campaign contributions. “You have people in power that are owned by the corporations — they’ve taken so much money from them, even if they wanted to do better, the industries would go after them,” she says.

John Althouse/AFP via Getty Images

In 1999, floodwaters from Hurricane Floyd engulfed a Burgaw, North Carolina hog waste lagoon.

Disproportionately polluting poor and minority communities

Those most affected by CAFO pollution are people of color. Duplin and Sampson counties have the highest share of Latinx residents in the state, with 23 and almost 21 percent, respectively. The residents of these two counties are also about 25 and 26 percent Black, as compared with the statewide average of 22 percent.

In 2014, NC EJN, Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH), and Waterkeeper Alliance filed a Title VI Civil Rights complaint with the Office of Civil Rights at the U.S. EPA claiming the North Carolina environmental regulatory agency allowed industrial swine facilities in the state to operate “with grossly inadequate and outdated systems of controlling animal waste and little provision for government oversight” — and that they had an “unjustified disproportionate impact on the basis of race” against Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people.

In 2018, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) settled the complaint, and this year, they put measures in place including a program of air and water monitoring near hog operations and involving impacted community members in permitting decisions. “I believe there’s a group of people [at the DEQ] who are trying to do the right thing,” says Muhammad. “With more collaboration with communities, we’ve seen some change. But you have a body of people who want to hold onto those old ways.”

In the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color.

Another complicating factor is the fact that the state has cut the regulatory agency’s budget year after year. “If you don’t have the budget to hire the staff to do the inspections, that’s a problem,” White-Williamson says.

While the size of pork industry has stabilized since a moratorium on new facilities with the lagoon-and-sprayfield system went into effect in 1997, no such limit was put in place on chicken operations, and as a result, the size of the poultry industry has tripled since then.

According to a report released this summer by the Waterkeeper Alliance and Environmental Working Group, between 2012 and 2019, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys in Duplin, Sampson, and Robeson counties increased by 36 percent to 113 million, compared to only 17 percent in the rest of the state. The racial disparities continue as well: In Robeson County, 42 percent of residents identify as Native American — compared to 1.6 in the state as a whole, according to 2018 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The concentration of chicken CAFOs worries environmental advocates, because rather than being kept in pits, the drier chicken feces is stored in large, uncovered piles and runs off into waterways when it rains. North Carolina chickens produce three times more nitrogen and six times more phosphorous than its hogs, causing environmental damage like toxic algal blooms and fish kills.

Unlike with hogs, the chicken industry does not have to notify the government when it opens a new facility, even if it is in an area prone to floods. As a result, the state environmental regulation agency often does not even know where chicken CAFOs are located, and inspections occur only when a complaint arises.

Lumber Riverkeeper Jeff Currie, who can smell poultry CAFOs from his house, says in the two years that have passed since Hurricane Florence, he’s documented 17 new operations consisting of 320 new barns in the watersheds he watches over.

Currie points out that, in the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline and a controversial wood pellet plant were both slated to be built in low-income communities of color in the area this year. While the pipeline was cancelled in July, the pellet plant is on its way to completion. If you don’t have the money to hire a private attorney and exert influence, Currie says, “you get dumped on.”

The effects of disenfranchisement

The environmental injustices piled onto low-income communities of color stem in part from their lack of political influence; disenfranchisement efforts on the part of politicians and parties who’d like to stay in power only make it worse.

Eastern North Carolina residents say that even without the state’s attempts to make voting difficult for them, the democratic process is frustrating, because when it comes to protecting them from agricultural pollution, there are no candidates who actually represent their interests.

“You get to the point where you’re like, what’s the point?” Currie says. “It’s not party-based — they all took the money. So who do you go to to try to get a bill introduced to end poultry operations in the 100-year floodplain?”

It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage.

White-Williamson believes even if solid state- and federal-level lawmakers were elected in 2020, it would take decades to recover from the damage that has resulted from the regulatory rollbacks, budgetary priorities, and culture of hatred that elected officials have promoted over the last few years. “It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage,” she says. “I feel like this is going to [take] almost a generation to straighten out.”

Muhammad is similarly concerned. “I’ve looked at everybody running from the federal level down to the local level, and I don’t hold out hope it’ll be a process that’ll bring about a lot of change,” she says.

And yet, despite the lack of strong local representation on CAFOs, many eastern North Carolina residents are still motivated by a desire to see change at the top, and they’re mobilizing to help each other get out the vote. Because, despite the roadblocks placed in their way and their lack of expectation for change, they have hope that things can get better — they offer as examples the victory in the Smithfield nuisance cases and the collapse of the oil pipeline project. Though the overall system is structured against them, they’ve seen small successes, and they plan to keep at it.

“If we have to continue to fight for the right to vote, so be it,” Herring says. “Whatever the issue is in our communities that is keeping us from living the best lives we can for our families and children, we have to organize, stay informed, hold meetings, make trips, write letters, make phone calls — do whatever we have to do to keep the issue on the forefront until we bring about change. We can’t give up.”

• Fighting Voter Suppression, Environmental Racism, and Corporate Agriculture in Hog Country [Civil Eats]

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/31HCIWv https://ift.tt/3jvz0Fh

A voter waits in line a polling place in Black Mountain, North Carolina | Photo by Brian Blanco/Getty Images

In an election like none before it, the residents of North Carolina’s hog- and poultry-intensive eastern counties are fighting to regain the power of their vote

This story was originally published on Civil Eats.

Elsie Herring spends many days documenting and responding to complaints from her neighbors — about everything from the stench coming off of factory farms to the clearcutting of trees for timber to the emissions from nearby factories. But lately, when Herring, a community organizer for the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (EJN), gets a call, she’s also been making sure the person on the other end of the line has a plan in place to vote.

With almost two million swine within its borders, Herring’s native Duplin County in eastern North Carolina is the top hog-producing county in the United States. And because many residents have pre-existing health conditions, in part from living alongside the waste produced by so many animals, many are choosing to mail their ballots in this year rather than venture to the polls, where COVID-19 presents an additional threat.

But, in a part of the state home to many people of color, Herring worries about reports of minority ballot rejection rates. In North Carolina, the ballots of white voters are being rejected at a rate of .5 percent, while Black voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 1.8 percent rate and Native American voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 4 percent rate (eight times more than white voters’), according to October 21 data from the U.S. Elections Project.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other.

“They’re disproportionate, and right there, that tells me they’re trying to suppress the Black votes,” Herring says. “That has always been their focus, to suppress our vote and not allow us the right.”

And so, she carefully walks her neighbors through the mail-in voting process: “We’re telling them to be careful and aware of what they’re writing and not writing on their ballots. The witness name has to be printed, and you have to have their signature and address. If that’s not there, they kick it out.”

Herring’s fears about the suppression of minority votes are not ill-founded, given recent and long-term efforts in North Carolina. Over the last decade, the state’s General Assembly, which the Republican party has controlled since 2010, has gerrymandered voting district maps along racial lines and passed numerous laws aimed at making it harder for minorities to vote (though many of the measures have not held up in court and are no longer in place).

In the midst of these ongoing efforts, many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities in the eastern part of the state say they’ve repeatedly watched as their elected officials promote the interests of hog and poultry companies over their safety and well-being — as evidenced by the number and density of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) permitted in their communities and the ineffectiveness of the facilities’ waste-disposal systems.

In addition to enabling the industry to concentrate around low-income communities of color, residents say state lawmakers have limited the tools those communities once had at their disposal to protest the resulting pollution.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other: Without people in office to protect their interests, polluting industries such as the state’s industrial hog and poultry operations proliferate and remain largely unchecked, Herring says. And when industries pollute with little consequence, damaging the health and quality of life of the people around them, people are less likely to prioritize getting to the polls, especially given the fact that many are already dealing with myriad other issues, including poverty, food and housing insecurity, and lack of quality education and access to healthcare.

“It’s particularly troubling that when someone who is harmed by all these cumulative impacts seeks to remedy that . . . they find [that] the legislature in recent years has taken very intentional steps to deprive them of long-available remedies,” says Will Hendrick, staff attorney and manager of the Waterkeeper Alliance’s North Carolina Pure Farms, Pure Waters campaign.

“The reaction is, ‘My vote won’t matter — corporations control everything, and that won’t change.’”

Sherri White-Williamson, who worked for years in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office for Environmental Justice before returning two years ago to her hometown in Sampson County, says she has tried to encourage young people in her town to vote. “The reaction is, ‘Why should I? My vote won’t matter — they [corporations] control everything, and that won’t change,’” says White-Williamson, who now works as the NC Conservation Network’s environmental justice policy director. “People who live in communities and get stuff dumped on them feel less empowered to be able to effect any change.”

As a swing state that voted for Barack Obama in 2008, Mitt Romney in 2012, and Donald Trump in 2016, North Carolina will be pivotal in this election. The U.S. Senate race between Republican incumbent Thom Tillis and his Democratic challenger Cal Cunningham could affect which party controls Congress as well. And while there are many conservative parts of the state, the demographics are changing as metropolitan areas continue to grow and more Latinx and young people register to vote.

Despite the factors stacked against them — made worse by the pandemic — Herring says many people in eastern North Carolina are still determined to make their voices heard. This year, groups like the one she’s involved with are working to educate voters and ensure they have transportation to the polls. And while Herring’s biggest concern is that her community’s votes will be under attack, she asks: “What can we do to combat that? I don’t know, other than just showing up at the polls to bring about a change.”

Photo by Logan Cyrus/AFP via Getty Images

An employee of the Mecklenburg County Board of Election in Charlotte, North Carolina holds up instructions that are mailed with absentee ballots for the 2020 election.

Suppressing the vote

In 2011, Republicans gained control of both of North Carolina’s Congressional houses and redrew the legislative district maps in the once-a-decade redistricting process to favor their party. In 2017, a district court and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the maps were illegally racially gerrymandered, meant to dilute the voice of Black voters. Two years after lawmakers submitted new maps, federal judges struck down the voting districts again, this time as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, saying they had been drawn with “surgical precision” — and were among the most manipulated in the nation. Lawmakers were ordered a second time to redraw the maps, which will be redone yet again in 2021, based on the 2020 Census.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in the state have made two other attempts at passing voter suppression laws. HB 589, one of the most dramatic voting rights rollbacks in the U.S., was overturned in federal court after it had been in effect for several years, and the voter ID requirement HB 1092 was blocked by a federal judge.

“There are a lot of different ways people are trying to cut back who is eligible to vote, whose votes count after they are cast, and who is going to feel comfortable voting,” says Kat Roblez, staff attorney with Forward Justice, a nonpartisan organization advancing racial, social, and economic justice in the South. In the Old North State — and nationwide — these tactics commonly include in-person voter intimidation at the polls, periodic purges of voter rolls, the spread of misinformation, voter ID requirements, and felony disenfranchisement laws, she says.

This year, the pandemic and the divisive nature of politics bring additional concerns. While in 2016, about 25 percent of total votes were cast by mail, this year that portion will be almost twice that, according to the Pew Research Center — and voting in a new way comes with its own complications. “It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion,” says Roblez. At the same time, many residents have concerns about the effectiveness of the postal service itself, prompted by budget cuts and policy changes put in place over the summer.

“It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion.”

The increased number of demonstrations by white supremacist and neo-Confederate groups is also worrisome, Roblez says. “What we’re most concerned about in some of the more rural areas is . . . Confederate parades coming to the polls,” she says, recalling how last February, demonstrators hung Confederate flags at a polling site in Alamance County, North Carolina.

Social distancing requirements will also necessitate larger polling places, which can put rural precincts, with less infrastructure available, at a disadvantage. “In an instance where a bigger polling location is needed, they might close two others that are smaller, but that [new] location may not be as accessible,” explains Joselle Torres of Democracy NC.

White-Williamson remembers seeing voter suppression growing up in Sampson County — a particular business owner showing up at the polls to confuse and discourage Black voters, for example — but she hasn’t been aware of polling-place suppression efforts in recent years.

Still, she could see it happening this year. George Floyd was originally from Clinton, the town where she lives, and after his murder at the hands of a white police officer in May, protestors pulled down the Confederate statue in front of the Sampson County courthouse, sparking heated public debates.

“There are a lot of things fresh on people’s minds,” she says. “As a Republican county, I see the potential for there to be efforts at polling places to discourage voting, like what we’re seeing around the country.”

Jeff Currie, a member of the Lumbee Tribe who works as a riverkeeper protecting the Lumber River watershed, believes the poor education system in low-income parts of the state also has a role to play in the area’s disenfranchisement.

“If the education system is not saying ‘vote,’ people don’t understand what voting is — they lack civics training and education and the cultural sense that that’s what you do,” he says.

As Election Day approaches, Democracy NC and Forward Justice are placing volunteer vote protectors at polling places across the state who “are ready and trained to sound the alarm” if they see signs of suppression, adds Torres.

Chuck Liddy/Raleigh News & Observer/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

A pig at Silky Pork Farms in Duplin County, North Carolina

Corporations over constituents

While legislators have tried to limit voting, the hog and chicken industries in eastern North Carolina have grown exponentially in ways that damage their surroundings, residents say. In the 1970s, family farmers in North Carolina raised an average of 60 pigs per farm, and the animals were free to roam around outside. That began to change in the 1980s and ’90s, however, as state lawmakers like teacher and farmer Wendell Murphy sponsored and helped pass bills that shielded large-scale hog farms from local zoning regulations and gave the industry subsidies and tax exemptions.

Now, North Carolina ranks second in the country for the number of hogs it produces, and the state’s average hog farm houses more than 4,000 animals. The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties — the top two hog-producing counties in the country — produce 4 billion gallons of wet waste a year, making up 40 percent of the North Carolina’s total. The waste is stored in open-air pits and periodically sprayed on nearby fields.

The foul-smelling chemicals the facilities release — ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, in particular — have been associated with difficulty breathing, blood pressure spikes, increased stress and anxiety, and decreased quality of life. Additionally, a 2018 study found higher death rates of all studied diseases — including infant mortality, mortality due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia — among communities located near hog CAFOs.

The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties produce 4 billion gallons of waste a year. The waste is stored in open-air pits.

For years, residents have spoken out about their suffering. They’ve told their representatives that the odor from the facilities forces them indoors all the time; they can’t sit on their porches, play in their yards, open their windows, or hang their laundry on the line; they have to buy bottled water rather than drinking from their wells; and “dead boxes” containing pig carcasses line the roads, and buzzards, flies, gnats fill the air.

And yet, says Naeema Muhammad, organizing co-director of the NC EJN, the state legislators and regulatory agencies don’t listen — and repeatedly prioritize large corporations as they make decisions about the permitting and regulation of these facilities. Time after time, she says, “legislators pass bills unmistakably against their constituents, in favor of the industry.”

In 2013, 500 residents of eastern North Carolina filed nuisance suits against the Chinese-owned Smithfield subsidiary Murphy-Brown, LLC, which owns the majority of the hogs in the state, complaining of the health problems and unpleasant ills the company subjected them to. In a victory for the hog-farm neighbors, juries ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the first five of the more than 20 cases to be tried, awarding the 10 plaintiffs in the first lawsuit more than $50 million in damages. (This number was reduced to a total of $3.25 million due to the state’s punitive-damages cap.) The industry is currently appealing the ruling.

As these lawsuits worked their way through the justice system, though, Herring watched in horror as her county’s representative in the state legislature, Jimmy Dixon, sponsored a bill that tied the hands of disadvantaged people looking for protection from factory farm pollution. The bill, passed in 2017, limits the compensation plaintiffs can receive in civil suits like the Smithfield case to a sum related to the diminished value of their property, and prevents them from receiving damages related to health, quality of life, and lost income.

Dixon, who did not respond to a request for comment in this story, said the bill was designed to protect farmers from the “greedy” lawyers who would sue them. “This bill is designed to protect 50,000 hardworking North Carolina farmers who are feeding a hungry world,” Dixon wrote in a 2017 op-ed in The Raleigh News & Observer.

In 2018, Senator and farmer Brent Jackson sponsored a similar bill that practically eliminates the right of residents to sue industrial hog operations by declaring that agricultural operations cannot be considered nuisances if they employ practices generally accepted in the region (like spraying hog waste on fields, for example). “With Senate Bill 711 on the books, we don’t have a leg to stand on,” Herring says. “We have to take what they give us, and [we don’t] have an avenue for recourse.”

Though legislators say they have the interests of farmers and consumers in mind, Muhammad thinks it’s more about campaign contributions. “You have people in power that are owned by the corporations — they’ve taken so much money from them, even if they wanted to do better, the industries would go after them,” she says.

John Althouse/AFP via Getty Images

In 1999, floodwaters from Hurricane Floyd engulfed a Burgaw, North Carolina hog waste lagoon.

Disproportionately polluting poor and minority communities

Those most affected by CAFO pollution are people of color. Duplin and Sampson counties have the highest share of Latinx residents in the state, with 23 and almost 21 percent, respectively. The residents of these two counties are also about 25 and 26 percent Black, as compared with the statewide average of 22 percent.

In 2014, NC EJN, Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH), and Waterkeeper Alliance filed a Title VI Civil Rights complaint with the Office of Civil Rights at the U.S. EPA claiming the North Carolina environmental regulatory agency allowed industrial swine facilities in the state to operate “with grossly inadequate and outdated systems of controlling animal waste and little provision for government oversight” — and that they had an “unjustified disproportionate impact on the basis of race” against Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people.

In 2018, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) settled the complaint, and this year, they put measures in place including a program of air and water monitoring near hog operations and involving impacted community members in permitting decisions. “I believe there’s a group of people [at the DEQ] who are trying to do the right thing,” says Muhammad. “With more collaboration with communities, we’ve seen some change. But you have a body of people who want to hold onto those old ways.”

In the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color.

Another complicating factor is the fact that the state has cut the regulatory agency’s budget year after year. “If you don’t have the budget to hire the staff to do the inspections, that’s a problem,” White-Williamson says.

While the size of pork industry has stabilized since a moratorium on new facilities with the lagoon-and-sprayfield system went into effect in 1997, no such limit was put in place on chicken operations, and as a result, the size of the poultry industry has tripled since then.

According to a report released this summer by the Waterkeeper Alliance and Environmental Working Group, between 2012 and 2019, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys in Duplin, Sampson, and Robeson counties increased by 36 percent to 113 million, compared to only 17 percent in the rest of the state. The racial disparities continue as well: In Robeson County, 42 percent of residents identify as Native American — compared to 1.6 in the state as a whole, according to 2018 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The concentration of chicken CAFOs worries environmental advocates, because rather than being kept in pits, the drier chicken feces is stored in large, uncovered piles and runs off into waterways when it rains. North Carolina chickens produce three times more nitrogen and six times more phosphorous than its hogs, causing environmental damage like toxic algal blooms and fish kills.

Unlike with hogs, the chicken industry does not have to notify the government when it opens a new facility, even if it is in an area prone to floods. As a result, the state environmental regulation agency often does not even know where chicken CAFOs are located, and inspections occur only when a complaint arises.

Lumber Riverkeeper Jeff Currie, who can smell poultry CAFOs from his house, says in the two years that have passed since Hurricane Florence, he’s documented 17 new operations consisting of 320 new barns in the watersheds he watches over.

Currie points out that, in the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline and a controversial wood pellet plant were both slated to be built in low-income communities of color in the area this year. While the pipeline was cancelled in July, the pellet plant is on its way to completion. If you don’t have the money to hire a private attorney and exert influence, Currie says, “you get dumped on.”

The effects of disenfranchisement

The environmental injustices piled onto low-income communities of color stem in part from their lack of political influence; disenfranchisement efforts on the part of politicians and parties who’d like to stay in power only make it worse.

Eastern North Carolina residents say that even without the state’s attempts to make voting difficult for them, the democratic process is frustrating, because when it comes to protecting them from agricultural pollution, there are no candidates who actually represent their interests.

“You get to the point where you’re like, what’s the point?” Currie says. “It’s not party-based — they all took the money. So who do you go to to try to get a bill introduced to end poultry operations in the 100-year floodplain?”

It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage.

White-Williamson believes even if solid state- and federal-level lawmakers were elected in 2020, it would take decades to recover from the damage that has resulted from the regulatory rollbacks, budgetary priorities, and culture of hatred that elected officials have promoted over the last few years. “It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage,” she says. “I feel like this is going to [take] almost a generation to straighten out.”

Muhammad is similarly concerned. “I’ve looked at everybody running from the federal level down to the local level, and I don’t hold out hope it’ll be a process that’ll bring about a lot of change,” she says.

And yet, despite the lack of strong local representation on CAFOs, many eastern North Carolina residents are still motivated by a desire to see change at the top, and they’re mobilizing to help each other get out the vote. Because, despite the roadblocks placed in their way and their lack of expectation for change, they have hope that things can get better — they offer as examples the victory in the Smithfield nuisance cases and the collapse of the oil pipeline project. Though the overall system is structured against them, they’ve seen small successes, and they plan to keep at it.

“If we have to continue to fight for the right to vote, so be it,” Herring says. “Whatever the issue is in our communities that is keeping us from living the best lives we can for our families and children, we have to organize, stay informed, hold meetings, make trips, write letters, make phone calls — do whatever we have to do to keep the issue on the forefront until we bring about change. We can’t give up.”

• Fighting Voter Suppression, Environmental Racism, and Corporate Agriculture in Hog Country [Civil Eats]

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/31HCIWv via Blogger https://ift.tt/3orBhVR

0 notes

Text

Cyber-attacks are the newest frontier of war, and can strike harder than a natural disaster. Heres why the US could struggle to cope if it got hit.

Imagine waking up one day, and feeling like a hurricane hit — except everything is still standing.

The lights are out, there is no running water, you have no phone signal, no internet, no heating or air conditioning. Food starts rotting in your fridge, hospitals struggle to save their patients, trains and planes are stuck.

There are none of the collapsed buildings or torn-up trees that accompany a hurricane, and no flood waters. But, all the same, the world you take for granted has collapsed.

This is what it would look like if hackers decided to take your country offline.

Business Insider has researched the state of cyber warfare, and spoken with experts in cyber defense, to piece together what a large-scale attack on a country like the US could look like.

Nowadays nations have the ability to cause war-like damage to their enemy’s vital infrastructure without launching a military strike, helped along by both new offensive technology and the inexorable drive to connect more and more systems to the internet.

What makes infrastructure systems so vulnerable is that they exist at the crossroads between the digital world and the physical world, said Andrew Tsonchev, the director of technology for cyber defense firm Darktrace.

Computers increasingly control operational technologies that were previously in the hands of humans — anything from the systems that route electricity through power lines, to the mechanism which opens and closes a dam.

“These systems have been connected up to the wild west of the internet and there are exponential opportunities to break into them,” said Tsonchev. This creates a vulnerability which experts say is especially acute in the US.

Most US critical infrastructure is owned by private businesses, and the state does not incentivize them to prioritize cyber defense, according to Phil Neray, an industrial cybersecurity expert for the firm CyberX.

“For most of the utilities in the US that monitoring is not in place right now,” he said.

One of the most obvious vulnerabilities experts identify is the power grid, relied upon by virtually everyone living and working in a modern country.

Hackers showed that they could plunge thousands of people into darkness when they knocked out parts of the grid in Ukraine in 2015 and 2016. These hits were limited to certain areas, but a more extreme attack could hit a whole network at once.

Researchers for the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) are preparing for just that kind of scenario.

They told Business Insider just how painstaking — and slow — a restart would be if ever the US lost control of its power lines.

DARPA program manager Walter Weiss has been simulating a blackout on a secretive island the government primarily uses to study infectious animal diseases.

On the highly restricted Plum Island, Weiss and his team ran a worst-case scenario which requires a so-called “black start,” in which the grid has to be brought back from total deactivation.

“What scares us is that once you lose power it’s tough to bring it back online,” said Weiss. “Doing that during a cyber attack is even harder because you can’t trust the devices you need to restore power for that grid.”

DARPA staged what a cyber attack on the US power grid could look like in November.

(Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency)

The exercise requires experts to fight a barrage of cyber threats while also grappling with the logistics of restarting the power system in what Weiss called a “degraded environment.”

That means coordinating teams across different substations without phone or internet access, all while depending on old-fashioned generators that need to be refueled constantly.

Trial runs of this work, Weiss said, showed just how fragile and prone to disruption a recovery effort is. Substations are often far apart, and minor errors or miscommunications — like forgetting one type of screwdriver — can set an operation back by hours.

A worst-case scenario would require interdependent teams to coordinate these repairs across the entire country, as much of the population waits in darkness.

But even an attack on a seemingly less important utility could have a catastrophic impact.

Maritime ports are another prime target — San Diego and Barcelona reported attacks in a single week in 2018.

Both said their core operations stayed intact, but it is easy to imagine how interrupting the complicated logistics and bureaucracy of a modern shipping hub could ravage global trade, 90% of which is ocean-borne.

Itai Sela, the CEO of cybersecurity firm Naval Dome, told a recent conference that “the shipping industry should be on red alert” because of the cyber threat.

The world has already seen glimpses of the destruction a multipronged cyber attack could cause.

In 2010, the Israeli-American Stuxnet virus targeted the Iranian nuclear program, reportedly ruining one fifth of its enrichment facilities. It taught the world’s militaries that cyber attacks are a real threat.

Read more: The Stuxnet Attack On Iran’s Nuclear Plant Was ‘Far More Dangerous’ Than Previously Thought

The most intense frontier of cyber warfare is currently Ukraine, which is fighting a simmering conflict against Russia.

Besides the attacks on the power grid, the devastating NotPetya malware in 2017 paralyzed Ukrainian utility companies, banks, and government agencies. The malware proved so virulent that it spread to other countries.

Hackers have also caused significant disruption with so-called ransomware, which freezes computer systems unless the users had over large sums of money, often in hard-to-trace cryptocurrency.

An ongoing attack on local government services in Baltimore has frozen about 10,000 computers since May 7, getting in the way of ordinary activities like selling homes and paying the water bill. Again, this is proof of concept for something far larger.

In March this year, a cyber attack on one of the world’s largest aluminum producers, Oslo-based Norsk Hydro, forced it to close several plants which provide parts for carmakers and builders.

Norsk Hydro was hit by a cyber attack on Tuesday, March 19.

(Terje Pedersen/AFP/Getty Images)

In 2017 the WannaCry virus, designed to infect computers to extract a ransom, burst onto the internet and caused damage beyond anything its creators could have foreseen.

It forced Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the world’s biggest contract chipmaker, to shut down production for three days. In the UK, 200,000 computers used by the National Health System were compromised, halting medical treatment and costing nearly $120 million.

The US government said North Korean hackers were behind the ransomware.

Read more: Trump administration goes on media blitz to blame North Korea for massive WannaCry cyber attack

North Korean hackers were also blamed for the 2015 attack that leaked personal information from thousands of Sony employees to prevent the release of “The Dictator”, a comedy movie about Kim Jong Un.

These isolated events were middling to major news events when they happened. But they occur against a backdrop of lesser activity which rarely makes the news.

The reason we don’t hear about more attacks like this isn’t because nobody is trying — governments regularly tell us that they are fending off constant attacks from adversaries.

In the US, the FBI and DHS say Russian government hackers have managed to infiltrate critical infrastructure like the energy, nuclear, and manufacturing sectors.

The UK’s National Security Centre says it repels around ten attempted cyber attacks from hostile states every week.

Read more: US security officials say Russian hackers could shut down nuclear power plants and electric facilities in America

Although the capacity is there, like with most large-scale acts of war, state actors are fearful to pull the trigger.

James Andrew Lewis, a senior vice president and technology director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Business Insider that the fear of retaliation keeps many hackers in check.

“The caveat is how a country like the US would retaliate,” he said. “An attack on this scale would be a major geopolitical move.”

Despite the growing dangers, this uneasy and unspoken truce has kept the threat far from most people’s minds. For that to change, Lewis believes the world needs to see a real, large-scale attack with real collateral.

“I’m often asked: How many people have died in a cyber attack? Zero,” he said.

“Maybe that’s the threshold. People underappreciate the effects that aren’t immediately visible to them.”

The post Cyber-attacks are the newest frontier of war, and can strike harder than a natural disaster. Heres why the US could struggle to cope if it got hit. appeared first on Gyrlversion.

from WordPress http://www.gyrlversion.net/cyber-attacks-are-the-newest-frontier-of-war-and-can-strike-harder-than-a-natural-disaster-heres-why-the-us-could-struggle-to-cope-if-it-got-hit/

0 notes

Text

Wait For The Moment

Like many children, classrooms were the formative environment of my youth. These were places where I did an awful lot of learning (most of the time). Some learning happened formally at desks or seated around a rug; other times, this was less structured, like learning how to share or be creative through interaction with others and my own independent learning. All in all, much of my learning happened in a school setting.

Though I cannot remember all the lessons over the years, I remember a lot about the schools. My first few schools I lived nearby and could walk to. As a teenager, I would carpool with family friends. I remember within each one, where some classrooms were located, where I could go #2 and stored my things, and how to enter and access each building.

Now fast forward to being a “young” adult, my professional career has revolved around the academic calendar, in a mix of school buildings and campuses. After graduating for the final time as a student, my career has stayed close to education. Since I’ve been in the workforce, my daytime is spent still orbiting around these institutions: on college campuses, presenting to a variety of school classrooms and youth programs, or based within one school at a time.

At the latest school where I work, a public high school, hundreds- if not thousands- of our students organized and participated in a walkout in March. This was hardly the singular example- a neighbor school had its own 3rd grade class simultaneously organize their own protest. Students across the country- and globe- have been staging walkouts and protests months after the latest mass school shooting. This was not the first, just the latest in a long line. These actions were in response to the shooting earlier this year at Marjory Stoneman High School in Florida. More students were marching on Friday, many participating from my same high school.

There is no one that (openly) agreed with these senseless acts of violence and shootings (that I know of, although I could be wrong on that somehow). Reactions ranged, from tweets placing blame to those of uncontrolled- and justified- emotion. Most notably though, there have been the voices, strength, anger, and leadership of students. Since the Parkland shooting, the nation- and world- have taken notice of the leadership by these young people of Marjory Stoneman, and others like them.

Granted interviews and a microphone, many of the surviving students have been heralded as the fulcrum to finally crack the debate on gun rights and common sense reform. With access to a platform and to politicians, many students and victim’s families are making their voices heard, having confronted their local politicians on gun control and those recipients of NRA funding.

All of that is amazing.

Now remember, none of these young people were seeking out this opportunity. Instead, they witnessed, experienced and survived a school shooting.

While no one is really supporting the fact that this shooting happened, many are taking this opportunity to remind of the importance, and constitutional right, of guns. Even in Florida, within weeks of the shooting, the state voted to arm teachers (I wonder where that brilliant idea came from..). And then things like this happen, and you wonder how this was ever considered a positive idea.

So the safety’s off, let’s talk about guns if that’s what y’all want.

...

(1) The notion of Gun Reform

Gun reform doesn’t mean:

-No one should own a gun

-You shouldn’t be able to be safe and protect yourself

-You are losing your freedoms

Who in the world needs an assault rifle? I mean, maybe it’s because I do not like nor support the extreme weaponization of anyone and am likely always going to be antiwar. Still, who could ever need an assault weapon? Why is a bump stock necessary for hunting or for you safeguarding you property?

Let’s be clear too: if the argument is “it’s in the Constitution, Bill of Rights, etc.,” this would not be the first time we reformed or rewrote our founding documents. Remember that these documents were written into law at the founding of our country, centuries ago..when slavery was legal. Not to mention, without our formalized (racist) institutions and much of the country unexplored/destroyed by European immigrants, safety looked differently.

So I’m sorry NRA, private industries and interested citizens. A few things may need to be adjusted for the times, guns included. To start, let’s acknowledge that the rates of shootings in this country are inexcusable- and truly, preventable. Trying to prevent the next shooting is not an agenda; it’s called logical sense. There is really never going to be a time where it is “appropriate” to talk about guns, seeing as we are constantly using and killing with them across the country- so maybe we should be done talking?

For those of y’all looking for voices of reason, there are perspectives and people speaking on both sides. Be sure you’re at least listening to those who have had experience with firearms talk about some minuscule improvements to gun laws. Reform with gun laws- like any reform- doesn’t mean that the original no longer exists. It adapts and updates with the times, which leads to trying to decide between...

(2) Guns or people?

By the way, though I think that the notion that guns = safety is a false equivalency, it’s a little sad that there are some people who seem to prioritize guns > human life. Like seriously, if I told you definitively, with research, personal testimony and the like, that with fewer guns in X country, there was less violence, fewer deaths and no increase in burglaries or vindictive animals who killed humans, there would still be people arguing for guns.

I get that this is something that seems deeply rooted into the fabric of our country and ‘American’ (I would counter these are not all positive affiliations, but I digress). If that is your angle, how do you respond to the folks with military experience who contend that these are not an everyday necessity for folks? Or that in fact more guns especially in schools have a direct link to greater/worser penalties and punishment of students of color in our school system?

Arming teachers, anyone, in a school building is a license to increase the school-to-prison pipeline and add capital punishment to the list of responsibilities of teachers. When our schools, and especially punitive discipline procedures, require an overhaul, we want to give out more guns? Hell no. Most teachers are not interested, most educators are overworked, and most students- namely students of color- are already over disciplined. A gun will make that situation better? If you talked to most educators- no, not her- the issues they are facing in schools and education, having a gun is not likely to be high on the list.

And then there’s the ongoing, supposed link between...

(3) Guns, Shootings, and Mental Health

As access to guns is relatively easy in this country, there are a diverse array of folks who own and gain access to weapons. This includes people living with a number of mental illnesses as well as those who do not. Some of them, maybe, have committed crimes, killing others and/or themselves. Some of these shootings are not in the least related to the issue or perpetuated by folks with mental health illnesses.

Now I can agree with the idea that some people should not have firearms. If someone has been diagnosed with a mental disorder, and specific ones that can be determined by mental health professionals, perhaps they should have some evaluation before getting a gun, if ever. I also think that if someone is an overt or closeted racist, xenophobe, anti-semitic, homo-, bi- or transphobic, they too should have difficulty gaining access to a weapon.

I can also agree that there is a connection between shootings, guns, and mental health concerns. Whether a large shooting with numerous casualties or a single shot that leaves no one dead, there are lifetime effects for the survivors. Mental health services are a necessity for the folks that have to live with this trauma. It also would unfortunately seem that among those who are shot and killed in senseless killings have their own history of mental health diagnoses.

Commonly, the most public retort after a mass shooting committed by a white man, we talk about mental health. Maybe these folks need services and support. Maybe we need to actually tend to reforming and updating our mental health system, rather than shuttling folks into our jails and prisons, and giving people the help they need. However, we only talk about mental health on certain instances when guns and shootings are discussed, and that boils down to...

(4) Privilege- who do we hear from and whose lives do we value

I hate what happened at Parkland. And yet. There are people dying of gun violence everywhere in our country. People of color continue to be killed at alarming rates, publicly in examples by police. Even in instances of clear murder, these police shooters or night watchmen are most often let free without punishment. There are poor people, trans people, undocumented people and others whose deaths are not given any public, mainstream attention though their lives are lost too.

Specifically after Parkland, we have heard from the primarily same group of white and light-skinned students. Now I don’t entirely fault the students themselves. They are naming the discrepancy of how much coverage their largely white, largely affluent school and community have received since the shooting; how that might be different if there school was made up of different students. And that’s great.

However, it seems like there are others in their own school looking to speak and be heard..and they aren’t getting a chance. Beyond the school in Parkland, there are others, survivors of gun violence, clamoring to be heard who go unnoticed. There are innumerable organizations and organizing vying to amend our gun problem. These are commonly ignored, overlooked and not given the resources necessary or deserved- though on they fight and change the world. Maybe the students can not just acknowledge others but actually invite other students into the fold, onto the platform?

...

I know there are people with guns who say they are liberal or vote Democrat. I know Republicans that want gun reform. I do not think is simply a black and white- or rather, blue or red political issue. As is so commonly the case, there are an abundance of options that exist between current gun procedures and allowances and stripping everyone of their guns.

Also, there is no denying there is a problem with school shootings. Although there is also a problem with shootings in movie theaters; at nightclubs; at concerts; at churches, mosques and temples. I am not naive enough to think that guns are the only problem here. However, if people are unwilling to talk about the big issues that are destroying our world- you know, like systemic racism, xenophobia, and the like- then getting rid of your damn guns to at least shrink the damage people can inflict seems like a must.

People, daily if not hourly if not every minute in this country, are killed by the bullet. Those involved in the struggle, and those parked outside it. Millions are invested- and proposed to continue being spent- on our protection and institutions of “safety.” This includes guns and weaponry, $95M alone in Chicago that could be spent on other more dire services.

However, if you would rather keep your gun, I am totally open to thinking how that can be possible. If you are unhappy that people want to reign in the lax policies and availability of guns, that’s okay- don’t sing about it. If change is hard for you, get in line. Because while this may not be the time you want to have this conversation, we are having this conversation; there is no perfect time to wait for. Actually, with how constant shootings occur, there is no way we can discuss an ideal time: this is an ever present reality in our country. How could there ever be a time where we are not talking about this? How can this not matter enough to be a topic now, tomorrow and from now on until we curb the violence? In some sick, twisted way, it may appear beneficial to those clinging to their guns to hold out for a moment of peace and no shootings to talk, seeing as that time does not seem to be coming.

There is no argument when the right time is to get into it and dialogue about the issues related to guns and gun violence. Rather, if there is a problem- a constant, daily problem, across communities and locations- you either confront it and have the conversation or you allow it to continue. Stop waiting for the moment and do something.

(This latest blog is named after my favorite tune by Vulfpeck, straight outta Ann Arbor! You can listen to the song- featuring THE Antwaun Stanley- here. It’s worth listening beyond the introductory 45 seconds too.)

0 notes

Text