#but i have been reading mysteries recently and i also found some original text nancy drew books at work today

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

breaking news: turns out leaving a fic idea to simmer indefinitely in the drafts means that you can come back to it years later with a better ability to potentially execute the concept. more at 11

#if this doesnt pan out i will be quietly deleting this post in shame thanks for understanding#but i have been reading mysteries recently and i also found some original text nancy drew books at work today#and i am once again putting on [redacted] while i'm cleaning my room#so i'm not NOT thinking about my 'angie was a nancy drew girl' fic idea again#also not important but jfc the audhd really jumps tf out of me with this sometimes dbxbxhhxbsnx

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Masterpiece: America’s 50-Year-Old Love Affair with British Television Drama by Nancy West

2 out of 5 stars ✨✨

Synopsis:

What accounts for Masterpiece's longevity and influence? Masterpiece offers two reasons: the power of its drama and its aspirational appeal. West delivers great stories, stories that transport, enthrall, enrich, and comfort us, while also speaking to a uniquely American belief in the possibility of self-improvement, even self-transformation, through the acquisition of "culture."

My Notes:

"Enjoying this so far, but clearly the editor fell asleep at the wheel. I’ve noticed a bunch of stupid little mistakes. Like they ask a question that has an A, B, or C answer then say the answer is D. What? Number the questions with 2.2 or 7.2, all clear mistakes. Plus no spacing between certain words. I’m glad I only paid 99 cents for the Kindle version."

"I don’t think the author watched the Downton Abbey movie right, or totally misinterpreted it."

"I knew this wasn’t right but I double checked and rewatched the video of Fred Rogers giving his speech to Congress in 1969, he was not wearing his trademark cardigan sweater as the author states in this book. He’s wearing a suit. There’s a bunch of photographs of it as well. Sigh."

"Sometimes I feel while reading this that I’m getting yelled at for being a fan of Masterpiece."

"I’m fairly certain 2005’s Bleak House had fifteen episodes, not sixteen. Unless she’s splitting the first episode in two because that one was sixty minutes while the other episodes were only thirty minutes. Gonna look that up, be right back. I’m back, and I was right, it’s only fifteen episodes. I do remember when this aired on Masterpiece in hour long installments, it was eight episodes."

"Mas terpiece. Did nobody edit or check this book before print? Either they don’t space between two words or put a space in the middle of a longer word."

"Bette Davis never played Queen Victoria in film or television. She did however portray Queen Elizabeth l twice. Takes two minutes to fact check folks."

"It says here in 2015 Wolf Hall was the first Tudor program to air on Masterpiece in 25yrs is incorrect. In 2003 they aired Henry VIII and I only remember that cause Sean Bean was in it. That’s only like 12yrs. Plus the Virgin Queen in 2006."

"Now they calling my fav 80s fun crime shows indisputably crappy with low grade actors. Damn lady. WTF. 😆"

"Jolyon was not Soames’ brother but his cousin. Come on, it takes just a minute to fact check this stuff."

"In the 2008 rebranded opening for Masterpiece while Colin Firth is in the montage it is not from Pride & Prejudice because that program was not broadcast on PBS in America originally. The image is from 1999’s The Turn of the Screw."

"I fully believe no one edited or saw a finale copy before publishing. Did no one notice the countless words running together without a space between them? You can forgive an error like this sure, but this book is riddled with them."

"How dare they forget to add Kelley Hawes to the cast of 1998s Our Mutual Friend."

And again they forget to put Kelley Hawes’ name in the cast list for Wives & Daughters. Two strikes. I know they limiting the cast list to three, but come on now."

"I see they are putting the big names for this cast list, but they leave out Miranda Richardson for The Lost Prince and Gillian Anderson for Bleak House."

"I’m that person I know, but I just gotta point out for the 2007-2008 season they just say The Complete Jane Austen. Like no, they were all separate movies. You had Persuasion, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and the miniseries Sense & Sensibility. They premiered for the first time (originally aired on A&E) Emma starring Kate Beckinsale, and 1995’s Pride & Prejudice."

"Weird that while they are listing all the programs, at least till publication of this book, they don’t mention all the Sharpe films, or even all the Prime Suspect."

"Can we really consider The Collection or the excellent recent adaptation of Howard’s End true blue Masterpiece programs? I mean Howard’s End first aired on Starz then a year later on Masterpiece. The Collection was exclusive to Amazon Prime for like two years I think. Hmm."

"Ah, Prime Suspect is in the Mystery section. Makes sense.

"The few photos are left to be viewed at the end of the book. Wouldn’t it have been more practical, and more visually appealing, to have the photos on the pages were the programs/actors were discussed. Like we’re talking Downton Abbey here’s the text and a photo. I don’t know about this layout they got going here."

"The best photo for Sherlock they found was the region 2 dvd cover? Are you fucking series?"

"Why include a photo of 1995’s Pride & Prejudice when it’s not an original production of Masterpiece? I mean they rebroadcast the series like twelve or thirteen years after it premiered on A&E stateside. I call bull shit."

My Review:

Not great, but the best we’ll probably ever get which is sad. I’ve watched Masterpiece for decades now so I was super excited to get this book. I’m not sure what I was expecting, not what we got, but it’s not an entirely bad read. I wish it was more of an in-depth look into the productions, there’s fifty years worth. This book does go into some details about certain series, a few classics but much more about certain recent programs. I love Downton Abbey, but Masterpiece is much more than that show. I can forgive a few grammatical errors here and there, or the non spaces between words, but this book is littered with them. Did they not proof read or edit this book before publication? The biggest crime this book commits is the abundance of factual errors. Like the plot lines of certain programs, character relationships, episode counts, years, and so forth. It literally takes two minutes to fact check this stuff. Diehard fans are gonna take notice of those errors. I also hated how they crammed the few photos they had to the back of the book. It’s visually unappealing. I wished the photo was on the page when the program was talked about. With countless photos of the program Sherlock out there this book decided to go with a DVD cover. Completely lazy. Happy I didn’t pay $30 for this, only $0.99 for the Kindle version when it was on sale. Honestly not worth more than that. To be fair this book has interesting elements, just not enough to save it from being a disappointing read.

#masterpiece#america's 50yr old love affair with british television#nancy west#nonfiction#television#history#tv companion piece#kindle#my reviews

0 notes

Text

On Elias

[this is the third (3rd) time I’ve tried posting this since Tumblr’s mobile search/tag search keeps eating the post. because it’s perfectly fine with showing untagged personal posts and spam whenever you search for something, but randomly decides when to show Actual Content]

ok look I know people don’t always read the OP’s tags but I keep getting “I��M SURE HE’S EVIL” comments on a pair of gifsets with fairly obviously positive parallels and reblogging something just to definitively say “that mysterious character is eviiiiiiil” is Not Cool, even if it’s in the tags.

Yes, recent commentator, Elias definitely broke into the house. It's probably why he suggested that the Johnsons go out in the first place! But the common assumption is A) that he planted the books and B) that he did so for a malicious reason. It seems as obvious as it could possibly be while remaining unconfirmed. It seems so obvious in such a twisty show that I think it isn’t that straightforward.

Gosh, where to begin? Firstly, names and etymology are pretty good theory fodder and Easter eggs, e.g., ‘Hap’=haphephobia and all its ‘hap’-prefixed variants; ‘Khatun’ is both an old title of nobility and a modern word referring to any woman. 'Rahim' means ‘merciful’ or 'servant of the merciful'. 'Elias' is a cognate of 'Elijah'. Elijah was the Abrahamic prophet who sort of had a special connection with women and children; who was cared for by an angel; who resurrected the dead; who entered Heaven without dying at the end of his earthly life; who is sometimes believed to have become an angel. All of this information is available on Wikipedia! So even if Elias did plant the books, I don’t automatically assume he’s malicious.

There’s this interesting bit in an interview with The Atlantic:

Marling: [...] I think one of the original stories that was influential actually comes from Jewish mysticism. Do you know it?

Kornhaber: Is this leaving the door open for Elijah at Passover?

Marling: Yeah. It’s so beautiful. I think it’s amazing to try and use that as a reminder of trying to stay open. I struggle with that all the time. You get scared and you close the door. But I think The OA, she’s inviting them to let a new thing in.

(Principal Gilchrist's first name is another cognate of Elijah - 'Ellis' - and his surname means 'servant of Christ'. People have made the connection between Ellis and his "water under the bridge" comment to Ellis Island and the nearby Statue of Liberty, plus he has a snow globe of the latter.)

Elias’ potential connection with an ‘evil’ Rachel was probably debunked early by Zal Batmanglij on Twitter: the plants in her cell died because she refuses to water them as an act of rebellion. I'm too lazy to go through the whole thing about why her name being on the office wall in large Braille doesn't automatically mean she works there in the first place. I think she and Elias are connected (because of his car crash analogy and the “[My brother] never got to hear it”/”I’m a listener” lines), but I doubt it’s as evil agents.

Elias is shocked and defensive when he bumps into French in the house - but the scene follows French, so of course we aren't shocked and suspicious about French’s presence. Basically, the audience has had the same reaction to Elias breaking in as Elias initially has to French breaking in. Part of what makes Elias seem suspicious is his reaction. IMO Elias doesn't even imply or confirm that the OA was lying - he just doesn't correct French. The other 'suspicious' thing he does is...move his eyes while hugging French, which isn’t incriminating on its own since the emotion is ambiguous.

There's confusing reasoning behind why Elias would place the books in the first place. The books seem tailored to match major aspects of the OA's story. The immediate assumption is that if someone planted the books, they meant for the Crestwood Five to find them and conclude that she based lies upon them. But if that's the case, Elias likely had no way of knowing that French would break in, go to her room, thoroughly search her room, and look where he did. There was no guarantee that any of the Five would find the books, jump to the conclusion that OA was lying, then share the discovery with the others.

Alternatively, you could argue that Elias planted the books intending for someone else to find them during an investigation and use it as proof that OA was making up stories, and the Five would fall for it in the process. But in that case, why did he let French leave with all of the books? And remember, Buck kept one and the rest let him. It’s possible that they submitted the other books to the FBI offscreen, or that Elias replaced the books. But I’ve never seen the theory cover what happened to the books after the reveal, so I won’t play with that hypothetical situation here.

Maybe Elias planted the books for someone else to find and didn’t know French took them. After all, we don't know what happened after the hug. But that introduces a new set of logical problems. How would French sneak a big, heavy box out of the house? He could take it if Elias had already left or wasn’t watching him...but why would Elias leave French unsupervised? Does anyone think that Elias ensured French left, then French broke in again not long afterwards and took the books, all offscreen? And couldn’t his presumably nearby car be a potential giveaway?

So, the books don't make much sense as an attempt to disillusion the Five. Some people think French's reaction stretches audience suspension of disbelief, right - I think it's an even bigger stretch that the FBI would predict a break-in and his reaction. To a lesser extent, the books also don't make sense as an attempt to frame OA, because they end up with the boys and don’t seem to play a role beyond breaking their faith. As for how French took the books while Elias was there, Elias advocates strategic passivity and avoids direct persuasion; I don't find it outlandish that French would say something like "I need to show proof to the others" then take the box, and Elias wouldn’t protest because it's not part of his agenda either way.

The next most obvious explanation for the books is if they really are OA’s. They weren’t necessarily used to construct a lie.

In the previous episode, OA had a conversation with BBA about how cultures that suffer more loss tend to have more totems. OA knew this because of an exhibit that she loved so much as a child that she made her parents take her back twice. It made a lasting impact on her, as evidenced by the wolf hoodie that reminds her of Homer’s. BBA is not with the boys when French reveals the books, so she doesn't even have the chance to recall that conversation. We don’t know if BBA learned about the books after the boys did. And the books were specifically stored beneath the wolf hoodie. The Five may not be aware of the hoodie’s significance; Elias wouldn’t know the hoodie’s significance unless OA wore it to a session and he asked why she has a hoodie with a wolf on it, or she spontaneously told him, both of which seem a bit far-fetched. (Onscreen, at least, she never wore it to a therapy session.)

Ehh, miscellaneous notes:

It’s uncertain that OA can read English text. But the conversation with BBA says that the Thing Itself isn't as important as what it symbolises. (“Objects carry meaning in difficult times.”) She doesn't need to be able to read the books in order for them to mean something. Anyway, she might’ve been bilingual from a young age; she was 7 or 8 when she went blind and she seems fluent in English by the time we see her in the American boarding school. (There might be proof that she can write in English, since she signed the bottom of the note she left for her parents? It’s been interpreted both ways so idk.)

The Five getting discovered in the abandoned house probably wasn’t set up by Elias. BBA had previously slipped and told Principal Gilchrist about it while driving to save Steve.

I don’t strongly rule it out, but I don’t think Elias spied on the Five, because he only realises who French is when he tells him his name. Unless he’s pretending.

Why were the books under OA’s bed, under the hoodie? Maybe she hid her totems in case her parents found them, since Nancy already thought she had delusions that could easily be linked to The Oligarchs and The Iliad. It’s unclear to me, but there might be a moment in the first episode where OA shoves the video camera under her bed (starts at 29:15-ish), foreshadowing that she might’ve done the same thing with the books later.

The issues I have with my own theory are:

According to the label on the Amazon box, the books were delivered in September. That's at odds with how OA's video was posted in February 2016. But the FBI (or another organisation) ordering the books also doesn't make sense: they would’ve been planning to discredit her months before she returned or assembled the Five or told her story. Even if they knew about the experiments, Hap dumping OA on the road in February seemed entirely spontaneous; that itself was the result of a seemingly random event (getting caught by the sheriff). More importantly, I’d question why the boys didn't notice the discrepancy in dates, and why the FBI didn't realise it themselves. (Like, all they had to do was remove the label or use a different box.) How can they predict a very specific chain of events yet not be smart enough to remove a label? It’s not impossible in the broader scope of the story - maybe they have reality-warping powers, maybe there’s time travel involved - but right now it’s a big stretch just to support the basic theory that Elias planted the books. So I suspect the label is a minor production oversight. Considering exactly how briefly the date is onscreen and difficult to read even when the scene is paused, I think it wasn’t meant to be read by the audience. (Compare the length of the date’s visibility and its readability to earlier in the scene, when French looks at the newspaper clippings, or whenever a phone/computer screen takes up the frame.)

How did OA order the books? The hardest part is how she went online, but she could’ve placed the order sometime in the first episode before the router was taken away. It’s possible to order things from Amazon without a credit card and have them sent to a pickup point or post office, so that’s not a big issue if she had money somewhere (or stole it from her parents, which is 100% in-character for her). Sneaking the package into the house is another problem - but, then again, she’s cunning and her room is conveniently located so things can fairly easily go in/out of her window.

Elias suggested that the Johnsons go out for a family dinner. That somewhat complicates the timeframe he would’ve had for breaking in; if the outing had gone 'normally' they would've returned home before it was very late, yet still at an unpredictable time. (Again, he probably had no way of knowing they’d choose French's workplace, that it’d go badly, etc.) He was unable to break into the Johnsons' home on the night the OA finished her story, which is why he broke in later on, when French did. I guess Nancy and Abel went home after the incident at the Olive Garden and Elias saw the house was occupied, so he waited, and luckily for him they left the next day?

I’m not sure whether Elias lies when French asks if OA told him about Homer, the mine, and Hap’s studies. She told Elias specifics about the first and third premonitions, but it’s unclear how much she explained the second, Homer wasn’t mentioned by name onscreen, and we don’t know if she talked about the movements and angels. It’s worth noting that right after their last session, Elias does lie. OA explained her dreams, including the previous night’s. Afterwards, Nancy assumes Elias knows what happened last night...but he says no, seemingly to see how Nancy explains it. He’s capable of minor lies to Learn Things for ambiguous reasons. (Does he lie to Nancy for OA’s benefit? Or is it because he doesn’t trust OA, or is it simply an effort to hear different sides? I think the tone of the scene suggests he’s trying to help OA, but you might think it’s deliberately misleading. Anyway, they’re not all mutually exclusive motives.)

If the books really were OA’s, what was her reaction when she returned home and they were missing? She probably wouldn't tell her parents. But what would she think happened? Possibly she might be able to put two and two together since she’d previously helped Steve sneak into her room. Maybe she doesn’t seem sad right before the shooting because she deduced that the Five wanted to help her, and she didn’t know that the boys concluded she was lying.

We might be able to get general sense of where The OA is headed by examining Brit and Zal's previous work. Sound of My Voice is the most similar. One of the most common (and plausible) theories for SOMV is that Maggie was telling the truth and the 'FBI agent' wasn't actually an FBI agent. But there are other reused elements that were subverted: OA is much less intimidating and more personable than Maggie; the Five are inclined to believe her without being cult-like; the agent was trying to catch Maggie without her knowledge instead of possibly pretending to help her. I kinda hope it's a meta Red Herring planted for people who've watched both.

Elias was in the house for a reason. I think the video camera and all of the tapes might be a Chekhov's Gun. Brit Marling said something along the lines of "it’s worthy to question Elias’ motives"; he doesn’t necessarily have Good intentions. However, him planting the books isn’t a sure thing and we know nothing about whatever he did in the time gap before the shooting; there’s no indication that he helped or hindered OA in any way, if they’re still in contact, etc. So I think it’s a Bit Much to leap to "ELIAS IS EVIL" Not everyone who thinks he planted the books assumes he’s evil, which is nice. But it's Tiring seeing the evil accusation treated as if it's rare or a new theory, especially considering the depth of analysis that the rest of the show receives.

#elias rahim#the oa#oatheories#prairie johnson#oa#my oa theories#@ search function meet me in the pit you bitch#what are you doing? why are you so determined to smear elias' literally good name?#it's still not showing up??? i'm going to flip a table????

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1: Birth

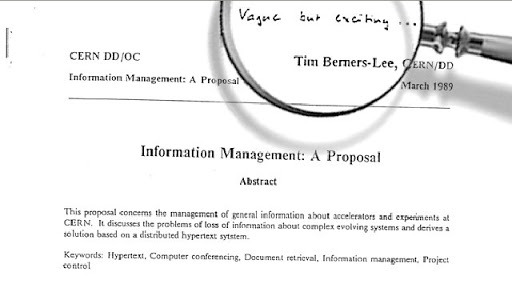

Tim Berners-Lee is fascinated with information. It has been his life’s work. For over four decades, he has sought to understand how it is mapped and stored and transmitted. How it passes from person to person. How the seeds of information become the roots of dramatic change. It is so fundamental to the work that he has done that when he wrote the proposal for what would eventually become the World Wide Web, he called it “Information Management, a Proposal.”

Information is the web’s core function. A series of bytes stream across the world and at the end of it is knowledge. The mechanism for this transfer — what we know as the web — was created by the intersection of two things. The first is the Internet, the technology that makes it all possible. The second is hypertext, the concept that grounds its use. They were brought together by Tim Berners-Lee. And when he was done he did something truly spectacular. He gave it away to everyone to use for free.

When Berners-Lee submitted “Information Management, a Proposal” to his superiors, they returned it with a comment on the top that read simply:

Vague, but exciting…

The web wasn’t a sure thing. Without the hindsight of today it looked far too simple to be effective. In other words, it was a hard sell. Berners-Lee was proficient at many things, but he was never a great salesman. He loved his idea for the web. But he had to convince everybody else to love it too.

Tim Berners-Lee has a mind that races. He has been known — based on interviews and public appearances — to jump from one idea to the next. He is almost always several steps ahead of what he is saying, which is often quite profound. Until recently, he only gave a rare interview here and there, and masked his greatest achievements with humility and a wry British wit.

What is immediately apparent is that Tim Berners-Lee is curious. Curious about everything. It has led him to explore some truly revolutionary ideas before they became truly revolutionary. But it also means that his focus is typically split. It makes it hard for him to hold on to things in his memory. “I’m certainly terrible at names and faces,” he once said in an interview. His original fascination with the elements for the web came from a very personal need to organize his own thoughts and connect them together, disparate and unconnected as they are. It is not at all unusual that when he reached for a metaphor for that organization, he came up with a web.

As a young boy, his curiosity was encouraged. His parents, Conway Berners-Lee and Mary Lee Woods, were mathematicians. They worked on the Ferranti Mark I, the world’s first commercially available computer, in the 1950s. They fondly speak of Berners-Lee as a child, taking things apart, experimenting with amateur engineering projects. There was nothing that he didn’t seek to understand further. Electronics — and computers specifically — were particularly enchanting.

Berners-Lee sometimes tells the story of a conversation he had with his with father as a young boy about the limitations of computers making associations between information that was not intrinsically linked. “The idea stayed with me that computers could be much more powerful,” Berners-Lee recalls, “if they could be programmed to link otherwise unconnected information. In an extreme view, the world can been seen as only connections.” He didn’t know it yet, but Berners-Lee had stumbled upon the idea of hypertext at a very early age. It would be several years before he would come back to it.

History is filled with attempts to organize knowledge. An oft-cited example is the Library of Alexandria, a fabled library of Ancient Greece that was thought to have had tens of thousands of meticulously organized texts.

Photo via

At the turn of the century, Paul Otlet tried something similar in Belgium. His project was called the Répertoire Bibliographique Universel (Universal Bibliography). Otlet and a team of researchers created a library of over 15 million index cards, each with a discrete and small piece of information in topics ranging from science to geography. Otlet devised a sophisticated numbering system that allowed him to link one index card to another. He fielded requests from researchers around the world via mail or telegram, and Otlet’s researchers could follow a trail of linked index cards to find an answer. Once properly linked, information becomes infinitely more useful.

A sudden surge of scientific research in the wake of World War II prompted Vanneaver Bush to propose another idea. In his groundbreaking essay in The Atlantic in 1945 entitled “As We May Think,” Bush imagined a mechanical library called a Memex. Like Otlet’s Universal Bibliography, the Memex stored bits of information. But instead of index cards, everything was stored on compact microfilm. Through the process of what he called “associative indexing,” users of the Memex could follow trails of related information through an intricate web of links.

The list of attempts goes on. But it was Ted Neslon who finally gave the concept a name in 1968, two decades after Bush’s article in The Atlantic. He called it hypertext.

Hypertext is, essentially, linked text. Nelson observed that in the real world, we often give meaning to the connections between concepts; it helps us grasp their importance and remember them for later. The proximity of a Post-It to your computer, the orientation of ingredients in your refrigerator, the order of books on your bookshelf. Invisible though they may seem, each of these signifiers hold meaning, whether consciously or subconsciously, and they are only fully realized when taking a step back. Hypertext was a way to bring those same kinds of meaningful connections to the digital world.

Nelson’s primary contribution to hypertext is a number of influential theories and a decades-long project still in progress known as Xanadu. Much like the web, Xanadau uses the power of a network to create a global system of links and pages. However, Xanadu puts a far greater emphasis on the ability to trace text to its original author for monetization and attribution purposes. This distinction, known as transculsion, has been a near impossible technological problem to solve.

Nelson’s interest in hypertext stems from the same issue with memory and recall as Berners-Lee. He refers to it is as his hummingbird mind. Nelson finds it hard to hold on to associations he creates in the real world. Hypertext offers a way for him to map associations digitally, so that he can call on them later. Berners-Lee and Nelson met for the first time a couple of years after the web was invented. They exchanged ideas and philosophies, and Berners-Lee was able to thank Nelson for his influential thinking. At the end of the meeting, Berners-Lee asked if he could take a picture. Nelson, in turn, asked for a short video recording. Each was commemorating the moment they knew they would eventually forget. And each turned to technology for a solution.

By the mid-80s, on the wave of innovation in personal computing, there were several hypertext applications out in the wild. The hypertext community — a dedicated group of software engineers that believed in the promise of hypertext – created programs for researchers, academics, and even off-the-shelf personal computers. Every research lab worth their weight in salt had a hypertext project. Together they built entirely new paradigms into their software, processes and concepts that feel wonderfully familiar today but were completely outside the realm of possibilities just a few years earlier.

At Brown University, the very place where Ted Nelson was studying when he coined the term hypertext, Norman Meyrowitz, Nancy Garrett, and Karen Catlin were the first to breathe life into the hyperlink, which was introduced in their program Intermedia. At Symbolics, Janet Walker was toying with the idea of saving links for later, a kind of speed dial for the digital world – something she was calling a bookmark. At the University of Maryland, Ben Schneiderman sought to compile and link the world’s largest source of information with his Interactive Encyclopedia System.

Dame Wendy Hall, at the University of Southhampton, sought to extend the life of the link further in her own program, Microcosm. Each link made by the user was stored in a linkbase, a database apart from the main text specifically designed to store metadata about connections. In Microcosm, links could never die, never rot away. If their connection was severed they could point elsewhere since links weren’t directly tied to text. You could even write a bit of text alongside links, expanding a bit on why the link was important, or add to a document separate layers of links, one, for instance, a tailored set of carefully curated references for experts on a given topic, the other a more laid back set of links for the casual audience.

There were mailing lists and conferences and an entire community that was small, friendly, fiercely competitive and locked in an arms race to find the next big thing. It was impossible not to get swept up in the fervor. Hypertext enabled a new way to store actual, tangible knowledge; with every innovation the digital world became more intricate and expansive and all-encompassing.

Then came the heavy hitters. Under a shroud of mystery, researchers and programmers at the legendary Xerox PARC were building NoteCards. Apple caught wind of the idea and found it so compelling that they shipped their own hypertext application called Hypercard, bundled right into the Mac operating system. If you were a late Apple II user, you likely have fond memories of Hypercard, an interface that allowed you to create a card, and quickly link it to another. Cards could be anything, a recipe maybe, or the prototype of a latest project. And, one by one, you could link those cards up, visually and with no friction, until you had a digital reflection of your ideas.

Towards the end of the 80s, it was clear that hypertext had a bright future. In just a few short years, the software had advanced in leaps and bounds.

After a brief stint studying physics at The Queen’s College, Oxford, Tim Berners-Lee returned to his first love: computers. He eventually found a short-term, six-month contract at the particle physics lab Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (European Council for Nuclear Research), or simply, CERN.

CERN is responsible for a long line of particle physics breakthroughs. Most recently, they built the Large Hadron Collider, which led to the confirmation of the Higgs Boson particle, a.k.a. the “God particle.”

CERN doesn’t operate like most research labs. Its internal staff makes up only a small percentage of the people that use the lab. Any research team from around the world can come and use the CERN facilities, provided that they are able to prove their research fits within the stated goals of the institution. A majority of CERN occupants are from these research teams. CERN is a dynamic, sprawling campus of researchers, ferrying from location to location on bicycles or mine-carts, working on the secrets of the universe. Each team is expected to bring their own equipment and expertise. That includes computers.

Berners-Lee was hired to assist with software on an earlier version of the particle accelerator called the Proton Synchrotron. When he arrived, he was blown away by the amount of pure, unfiltered information that flowed through CERN. It was nearly impossible to keep track of it all and equally impossible to find what you were looking for. Berners-Lee wanted to capture that information and organize it.

His mind flashed back to that conversation with his father all those years ago. What if it were possible to create a computer program that allowed you to make random associations between bits of information? What if you could, in other words, link one thing to another? He began working on a software project on the side for himself. Years later, that would be the same way he built the web. He called this project ENQUIRE, named for a Victorian handbook he had read as a child.

Using a simple prompt, ENQUIRE users could create a block of info, something like Otlet’s index cards all those years ago. And just like the Universal Bibliography, ENQUIRE allowed you to link one block to another. Tools were bundled in to make it easier to zoom back and see the connections between the links. For Berners-Lee this filled a simple need: it replaced the part of his memory that made it impossible for him to remember names and faces with a digital tool.

Compared to the software being actively developed at the University of Southampton or at Xerox or Apple, ENQUIRE was unsophisticated. It lacked a visual interface, and its format was rudimentary. A program like Hypercard supported rich-media and advanced two-way connections. But ENQUIRE was only Berners-Lee’s first experiment with hypertext. He would drop the project when his contract was up at CERN.

Berners-Lee would go and work for himself for several years before returning to CERN. By the time he came back, there would be something much more interesting for him to experiment with. Just around the corner was the Internet.

Packet switching is the single most important invention in the history of the Internet. It is how messages are transmitted over a globally decentralized network. It was discovered almost simultaneously in the late-60s by two different computer scientists, Donald Davies and Paul Baran. Both were interested in the way in which it made networks resilient.

Traditional telecommunications at the time were managed by what is known as circuit switching. With circuit switching, a direct connection is open between the sender and receiver, and the message is sent in its entirety between the two. That connection needs to be persistent and each channel can only carry a single message at a time. That line stays open for the duration of a message and everything is run through a centralized switch.

If you’re searching for an example of circuit switching, you don’t have to look far. That’s how telephones work (or used to, at least). If you’ve ever seen an old film (or even a TV show like Mad Men) where an operator pulls a plug out of a wall and plugs it back in to connect a telephone call, that’s circuit switching (though that was all eventually automated). Circuit switching works because everything is sent over the wire all at once and through a centralized switch. That’s what the operators are connecting.

Packet switching works differently. Messages are divided into smaller bits, or packets, and sent over the wire a little at a time. They can be sent in any order because each packet has just enough information to know where in the order it belongs. Packets are sent through until the message is complete, and then re-assembled on the other side. There are a few advantages to a packet-switched network. Multiple messages can be sent at the same time over the same connection, split up into little packets. And crucially, the network doesn’t need centralization. Each node in the network can pass around packets to any other node without a central routing system. This made it ideal in a situation that requires extreme adaptability, like in the fallout of an atomic war, Paul Baran’s original reason for devising the concept.

When Davies began shopping around his idea for packet switching to the telecommunications industry, he was shown the door. “I went along to Siemens once and talked to them, and they actually used the words, they accused me of technical — they were really saying that I was being impertinent by suggesting anything like packet switching. I can’t remember the exact words, but it amounted to that, that I was challenging the whole of their authority.” Traditional telephone companies were not at all interested in packet switching. But ARPA was.

ARPA, later known as DARPA, was a research agency embedded in the United States Department of Defense. It was created in the throes of the Cold War — a reaction to the launch of the Sputnik satellite by Russia — but without a core focus. (It was created at the same time as NASA, so launching things into space was already taken.) To adapt to their situation, ARPA recruited research teams from colleges around the country. They acted as a coordinator and mediator between several active university research projects with a military focus.

ARPA’s organization had one surprising and crucial side effect. It was comprised mostly of professors and graduate students who were working at its partner universities. The general attitude was that as long as you could prove some sort of modest relation to a military application, you could pitch your project for funding. As a result, ARPA was filled with lots of ambitious and free-thinking individuals working inside of a buttoned-up government agency, with little oversight, coming up with the craziest and most world-changing ideas they could. “We expected that a professional crew would show up eventually to take over the problems we were dealing with,” recalls Bob Kahn, an ARPA programmer critical to the invention of the Internet. The “professionals” never showed up.

One of those professors was Leonard Kleinrock at UCLA. He was involved in the first stages of ARPANET, the network that would eventually become the Internet. His job was to help implement the most controversial part of the project, the still theoretical concept known as packet switching, which enabled a decentralized and efficient design for the ARPANET network. It is likely that the Internet would not have taken shape without it. Once packet switching was implemented, everything came together quickly. By the early 1980s, it was simply called the Internet. By the end of the 1980s, the Internet went commercial and global, including a node at CERN.

Once packet switching was implemented, everything came together quickly. By the early 1980s, it was simply called the Internet.

The first applications of the Internet are still in use today. FTP, used for transferring files over the network, was one of the first things built. Email is another one. It had been around for a couple of decades on a closed system already. When the Internet began to spread, email became networked and infinitely more useful.

Other projects were aimed at making the Internet more accessible. They had names like Archie, Gopher, and WAIS, and have largely been forgotten. They were united by a common goal of bringing some order to the chaos of a decentralized system. WAIS and Archie did so by indexing the documents put on the Internet to make them searchable and findable by users. Gopher did so with a structured, hierarchical system.

Kleinrock was there when the first message was ever sent over the Internet. He was supervising that part of the project, and even then, he knew what a revolutionary moment it was. However, he is quick to note that not everybody shared that feeling in the beginning. He recalls the sentiment held by the titans of the telecommunications industry like the Bell Telephone Company. “They said, ‘Little boy, go away,’ so we went away.” Most felt that the project would go nowhere, nothing more than a technological fad.

In other words, no one was paying much attention to what was going on and no one saw the Internet as much of a threat. So when that group of professors and graduate students tried to convince their higher-ups to let the whole thing be free — to let anyone implement the protocols of the Internet without a need for licenses or license fees — they didn’t get much pushback. The Internet slipped into public use and only the true technocratic dreamers of the late 20th century could have predicted what would happen next.

Berners-Lee returned to CERN in a fellowship position in 1984. It was four years after he had left. A lot had changed. CERN had developed their own network, known as CERNET, but by 1989, they arrived and hooked up to the new, internationally standard Internet. “In 1989, I thought,” he recalls, “look, it would be so much easier if everybody asking me questions all the time could just read my database, and it would be so much nicer if I could find out what these guys are doing by just jumping into a similar database of information for them.” Put another way, he wanted to share his own homepage, and get a link to everyone else’s.

What he needed was a way for researchers to share these “databases” without having to think much about how it all works. His way in with management was operating systems. CERN’s research teams all bring their own equipment, including computers, and there’s no way to guarantee they’re all running the same OS. Interoperability between operating systems is a difficult problem by design — generally speaking — the goal of an OS is to lock you in. Among its many other uses, a globally networked hypertext system like the web was a wonderful way for researchers to share notes between computers using different operating systems.

However, Berners-Lee had a bit of trouble explaining his idea. He’s never exactly been concise. By 1989, when he wrote “Information Management, a Proposal,” Berners-Lee already had worldwide ambitions. The document is thousands of words, filled with diagrams and charts. It jumps energetically from one idea to the next without fully explaining what’s just been said. Much of what would eventually become the web was included in the document, but it was just too big of an idea. It was met with a lukewarm response — that “Vague, but exciting” comment scrawled across the top.

A year later, in May of 1990, at the encouragement of his boss Mike Sendall (the author of that comment), Beners-Lee circulated the proposal again. This time it was enough to buy him a bit of time internally to work on it. He got lucky. Sendall understood his ambition and aptitude. He wouldn’t always get that kind of chance. The web needed to be marketed internally as an invaluable tool. CERN needed to need it. Taking complex ideas and boiling them down to their most salient, marketable points, however, was not Berners-Lee’s strength. For that, he was going to need a partner. He found one in Robert Cailliau.

Cailliau was a CERN veteran. By 1989, he’d worked there as a programmer for over 15 years. He’d embedded himself in the company culture, proving a useful resource helping teams organize their informational toolset and knowledge-sharing systems. He had helped several teams at CERN do exactly the kind of thing Berners-Lee was proposing, though at a smaller scale.

Temperamentally, Cailliau was about as different from Berners-Lee as you could get. He was hyper-organized and fastidious. He knew how to sell things internally, and he had made plenty of political inroads at CERN. What he shared with Berners-Lee was an almost insatiable curiosity. During his time as a nurse in the Belgian military, he got fidgety. “When there was slack at work, rather than sit in the infirmary twiddling my thumbs, I went and got myself some time on the computer there.” He ended up as a programmer in the military, working on war games and computerized models. He couldn’t help but look for the next big thing.

In the late 80s, Cailliau had a strong interest in hypertext. He was taking a look at Apple’s Hypercard as a potential internal documentation system at CERN when he caught wind of Berners-Lee’s proposal. He immediately recognized its potential.

Working alongside Berners-Lee, Cailliau pieced together a new proposal. Something more concise, more understandable, and more marketable. While Berners-Lee began putting together the technologies that would ultimately become the web, Cailliau began trying to sell the idea to interested parties inside of CERN.

The web, in all of its modern uses and ubiquity can be difficult to define as just one thing — we have the web on our refrigerators now. In the beginning, however, the web was made up of only a few essential features.

There was the web server, a computer wired to the Internet that can transmit documents and media (webpages) to other computers. Webpages are served via HTTP, a protocol designed by Berners-Lee in the earliest iterations of the web. HTTP is a layer on top of the Internet, and was designed to make things as simple, and resilient, as possible. HTTP is so simple that it forgets a request as soon as it has made it. It has no memory of the webpages its served in the past. The only thing HTTP is concerned with is the request it’s currently making. That makes it magnificently easy to use.

These webpages are sent to browsers, the software that you’re using to read this article. Browsers can read documents handed to them by server because they understand HTML, another early invention of Tim Berners-Lee. HTML is a markup language, it allows programmers to give meaning to their documents so that they can be understood. The “H” in HTML stands for Hypertext. Like HTTP, HTML — all of the building blocks programmers can use to structure a document — wasn’t all that complex, especially when compared to other hypertext applications at the time. HTML comes from a long line of other, similar markup languages, but Berners-Lee expanded it to include the link, in the form of an anchor tag. The <a> tag is the most important piece of HTML because it serves the web’s greatest function: to link together information.

The hyperlink was made possible by the Universal Resource Identifier (URI) later renamed to the Uniform Resource Indicator after the IETF found the word “universal” a bit too substantial. But for Berners-Lee, that was exactly the point. “Its universality is essential: the fact that a hypertext link can point to anything, be it personal, local or global, be it draft or highly polished,” he wrote in his personal history of the web. Of all the original technologies that made up the web, Berners-Lee — and several others — have noted that the URL was the most important.

By Christmas of 1990, Tim Berners-Lee had all of that built. A full prototype of the web was ready to go.

Cailliau, meanwhile, had had a bit of success trying to sell the idea to his bosses. He had hoped that his revised proposal would give him a team and some time. Instead he got six months and a single staff member, intern Nicola Pellow. Pellow was new to CERN, on placement for her mathematics degree. But her work on the Line Mode Browser, which enabled people from around the world using any operating system to browse the web, proved a crucial element in the web’s early success. Berners-Lee’s work, combined with the Line Mode Browser, became the web’s first set of tools. It was ready to show to the world.

When the team at CERN submitted a paper on the World Wide Web to the San Antonio Hypertext Conference in 1991, it was soundly rejected. They went anyway, and set up a table with a computer to demo it to conference attendees. One attendee remarked:

They have chutzpah calling that the World Wide Web!

The highlight of the web is that it was not at all sophisticated. Its use of hypertext was elementary, allowing for only simplistic text based links. And without two-way links, pretty much a given in hypertext applications, links could go dead at any minute. There was no linkbase, or sophisticated metadata assigned to links. There was just the anchor tag. The protocols that ran on top of the Internet were similarly basic. HTTP only allowed for a handful of actions, and alternatives like Gopher or WAIS offered far more options for advanced connections through the Internet network.

It was hard to explain, difficult to demo, and had overly lofty ambition. It was created by a man who didn’t have much interest in marketing his ideas. Even the name was somewhat absurd. “WWW” is one of only a handful of acronyms that actually takes longer to say than the full “World Wide Web.”

We know how this story ends. The web won. It’s used by billions of people and runs through everything we do. It is among the most remarkable technological achievements of the 20th century.

It had a few advantages, of course. It was instantly global and widely accessible thanks to the Internet. And the URL — and its uniqueness — is one of the more clever concepts to come from networked computing.

But if you want to truly understand why the web succeeded we have to come back to information. One of Berners-Lee’s deepest held beliefs is that information is incredibly powerful, and that it deserves to be free. He believed that the Web could deliver on that promise. For it to do that, the web would need to spread.

Berners-Lee looked to his successors for inspiration: the Internet. The Internet succeeded, in part, because they gave it away to everyone. After considering several licensing options, he lobbied CERN to release the web unlicensed to the general public. CERN, an organization far more interested in particle physics breakthroughs than hypertext, agreed. In 1993, the web officially entered the public domain.

And that was the turning point. They didn’t know it then, but that was the moment the web succeeded. When Berners-Lee was able to make globally available information truly free.

In an interview some years ago, Berners-Lee recalled how it was that the web came to be.

I had the idea for it. I defined how it would work. But it was actually created by people.

That may sound like humility from one of the world’s great thinkers — and it is that a little — but it is also the truth. The web was Berners-Lee’s gift to the world. He gave it to us, and we made it what it was. He and his team fought hard at CERN to make that happen.

Berners-Lee knew that with the resources available to him he would never be able to spread the web sufficiently outside of the hallways of CERN. Instead, he packaged up all the code that was needed to build a browser into a library called libwww and posted it to a Usenet group. That was enough for some people to get interested in browsers. But before browsers would be useful, you needed something to browse.

The post Chapter 1: Birth appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.

Chapter 1: Birth published first on https://deskbysnafu.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Letter to the Editor: Matthew Clemente’s Response to Kevin Hart’s “A Return to God After God”

JANUARY 13, 2019

Matthew Clemente’s Response to Kevin Hart’s “A Return to God After God” (November 25, 2018)

IT IS UNCOUTH to respond to a review of one’s work — this can be admitted from the start. Doubly so when one holds one’s reviewer in high regard, as I earnestly do. I have an enormous respect for Kevin Hart, who is not only a careful scholar but also a genuine artist, someone who brings together theology, philosophy, poetry, and the artistry of living in the manner called for by The Art of Anatheism. What is more, I was honored and humbled by Dr. Hart’s interest in the two works I co-edited. His review was thorough and thoughtful, engaging not only the volumes themselves but the philosophical currents that inspired them. Nevertheless, after reading the review I could not help but to feel that — out of fairness to our contributors who put so much time, care, and effort into their chapters — a couple of his claims necessitated responses.

First, Hart makes the assertion that “not many of the contributors have a rich knowledge of theology […] Many in the collections seem to be theological liberals, but theirs is not the theological liberalism of Ritschl or Tillich; it is a liberalism home grown in the thin soil of cultural studies.” Admittedly, I myself have not undergone the type of rigorous theological training needed to plumb the depths of my own Roman Catholic tradition. But I don’t believe the same could be said of, say, Emmanuel Falque, who has written extensively on the Church Fathers — in particular, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, and Augustine — as well as medieval theologians such as Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Bonaventure, and Erigena. John Panteleimon Manoussakis’s most recent book, The Ethics of Time (2017), proposes one of the more original, yet orthodox readings of Augustine’s Confessions in recent memory. It does so, in part, by developing key concepts such as the problem of movement (kinesis) in the thought of Maximus the Confessor, and the understanding of the diastemic nature of fallen creation in the writings of Gregory of Nyssa, then relating them to contemporary thinkers, including theologians like Hans Urs von Balthasar and John Zizioulas. Another contributor, Marianne Moyaert, has spent her career developing the notion of “Comparative Theology,” which attempts to “help theologians to further develop their doctrinal traditions” by encouraging them to engage rigorously with the sacred texts of other faiths. And, as Hart rightly notes, Christina Gschwandtner has written clear and careful treatments of many theologians and philosophers of religion, including a remarkably thorough consideration of the works of Ephrem the Syrian, in one of the volumes under review. All these scholars possess a rich understanding of Christian theology. None of them, as far as I am aware, considers himself or herself to be a theological liberal. Nor, I think, would most impartial observers question the depth of theological understanding of some of the more renowned contributors to the volumes such as Julia Kristeva, Thomas Altizer, John Caputo, and Jean-Luc Nancy.

Second, Hart writes, “I found myself asking why almost all the contributors seem so uninterested in putting pressure on Kearney’s ideas. It is strange […] upon completing these two volumes one would put them down with a sense that anatheism is the very last word in the philosophy of religion, with little to be said by way of correction.” This assertion struck me as odd for two reasons. First, because The Art of Anatheism — which I co-edited with Kearney — makes plain that its purpose is to “further develop the anatheist proposal.” That is, to explore how “anatheism — the return to God after the death of God — opens naturally to a philosophy of theopoetics.” The import of Kearney’s thesis is, as expressly stated, to be assumed. Second, and more to the point, it is patently untrue that neither volume includes criticism of Kearney’s work. Indeed, the very critiques that Hart raises in his review are addressed at length. “One target of Kearney’s criticism,” he writes, “endorsed by several of his admirers, is Christian dogma […] before agreeing to dissolve or at least minimize reliance on doctrine, one might want to be given good reasons why one should do so.” A fair point — one which Marianne Moyaert explicitly makes in her essay “Anatheism and Inter-Religious Hospitality.” Distancing herself from Kearney, she writes:

I share with Kearney the firm conviction that a spirit of interreligious hospitality has the potential to break through the spiral of tribal tendencies, but I do not share his negative stance on dogmatic traditions. I do not think dogmatic theism necessarily excludes welcoming strange gods; matters are more nuanced.

Relying on documents such as Dei verbum (the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation) and the writings of thinkers like John Henry Newman, Moyaert argues that her “particular dogmatic tradition contains theological resources for dialogue even though it also claims that in Christ, God’s revelation reaches its climax.” Agreeing with Hart’s assertion that “some dogmas, if not all of them, attempt to indicate mysteries,” she concludes that “Catholic theology also acknowledges that Deus semper maior est. Not only do we not grasp the fullness of his revelation; his gracious self-communication extends beyond the boundaries of our own Christian tradition.”

Hart writes: “It is odd that, over the course of two quite thick volumes, there is no concern registered about what one might retrieve of the sacred in the brave new world that Kearney sketches […] not all the sacred is benign. Some of it is quite malign.” This critique finds echoes in both books under review. Manoussakis dedicates a sizable portion of his essay to “Destructive Poetics, Painful Pleasure, and the Erotics of Thanatos.” Freud, Nietzsche, Lacan, Sartre, and Deleuze factor heavily in this anatheistic reading of the death drive and its relation to the divine. Jacob Rogozinski, in “The Twofold Face of God,” examines the horrible ambiguity of the divine in the story of Abraham — the God who demands the sacrifice of Isaac. Jean-Luc Nancy and James Wood each provide critical challenges to anatheism from atheistic perspectives. (Nancy even counters Kearney’s interpretation of da Messina’s Annunciata, offering a reading of his own. Where Kearney reads the painting as the secular made sacred, Nancy reads it as the sacred made profane.) And L. Callid Keefe-Perry, in “The Wager That Wasn’t,” questions whether Kearney sets up an authentic wager at all — whether the risk of choosing a “malign” deity is even possible for the anatheist proposal. “Kearney wants anatheism to persist in a moment of true tension […] And yet, I cannot help but to wonder if, in fact, the philosopher doth protest too much.”

It is neither my job nor my intention to review the reviewer or even his review. I hesitated before writing this response. As I said above, I have nothing but respect for Kevin Hart, and I would not have written this had I not felt that I owed it to the exceptional scholars who contributed to the two volumes; I felt obligated to highlight the rigor and clarity of their work. It is my hope that this congenial reply fosters more dialogue around what I consider to be a vital topic, and that it emphasizes not only the exactness we demand of our scholars, but also the hospitality, generosity, and goodwill characteristic of all those engaged in a genuine pursuit of wisdom.

¤

Kevin Hart’s Response to Matthew Clemente

Matthew Clemente thinks I have been a little rough with regard to the two collections of essays on Richard Kearney with which he has been involved. The review struck me as benign, all the more so because I put Kearney front and center in the review; he is not only a friend but also a philosopher whose itinerary is close to my own in some respects. In more than one way, Kearney and I belong to the same family, and I would like to see him treated well. That Clemente also wishes to treat him well is evident; and at heart we disagree more about the importance of historical knowledge and the proper treatment of intellectual positions than the rightness of the path Kearney has taken.

Doubtless that knowledge and treatment would have been more expressly articulated had I composed a long and careful essay on anatheism and its supporters. However, a review is a short piece, written partly to indicate to potential buyers if a given book is something they should own, and partly to maintain as high a standard of intellectual debate as is possible in the media. To be sure, I regret that so much discussion of religion these days is conducted without due knowledge of theology and the history of theology; it means that our intellectual engagements with religion, which are so important, are conducted with reference mainly to the living present, and often in ignorance of important distinctions, concepts, arguments, and practices. Clemente begins by conceding his own lack of “rigorous theological training,” which does not put him in a particularly good place from which to speak about my criticisms. He then identifies four contributors who, he thinks, are theologically well educated, one of whom I mention in the review for the depth of her knowledge of a writer in the early Church. Three contributors are defended, then, out of 35, which I take to be consistent with my judgment that “not many of the contributors have a rich knowledge of theology” [my emphasis].

Clemente also objects to my caveat that there is little offered by way of criticism of Kearney’s project. Any interesting idea benefits by having smart and well-educated people put pressure on it, and this can be done in all sorts of ways. One can examine examples that Kearney gives, ponder different ways of drawing distinctions than the ones he proposes, and explore counter-examples to his case. These things, along with several others, help the community to assess the value and strength of a position. What’s more, they help the author to sharpen his or her ideas and so produce the best work possible.

It’s true: I did not find enough of this critical practice in the two volumes under review. According to Clemente, my discontent was because I did not notice that the contributors sought to “further develop” Kearney’s ideas. On the contrary, I did; but I thought that the bulk of the two volumes simply didn’t engage those ideas at a level that would make anyone wish to take them up in preference to others that are also put before us in conferences, seminars, libraries, bookshops, journals, and the media. No doubt I could have applauded two friends, Emmanuel Falque and John Manoussakis, among others, for the depth of their philosophical and theological knowledge; and no doubt I could have thrown up my hands, for the umpteenth time, when reading Jean-Luc Nancy, who plays a very loose game with monotheism, and whose prose strikes me as rough and ready at best. But a review is a review, not an essay and not an exercise in grading term papers; and a review of two edited collections, with a total of 35 different contributions, must look a little more often to the mile than to the inch.

¤

Matthew Clemente is a teaching fellow at Boston College specializing in philosophy of religion and contemporary continental thought. He is author of Out of the Storm: A Novella and is editor (with Richard Kearney) of The Art of Anatheism.

Kevin Hart is the Edwin B. Kyle Professor of Christian Studies at the University of Virginia. His most recent books are Barefoot (Notre Dame University Press, 2018) and Poetry and Revelation (Bloomsbury, 2018). He is currently preparing a set of Gifford Lectures to deliver at the University of Glasgow.

Source: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/letter-to-the-editor-matthew-clementes-response-to-kevin-harts-a-return-to-god-after-god/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Is It Time For Us To Take Astrology Seriously?

New Post has been published on https://kidsviral.info/is-it-time-for-us-to-take-astrology-seriously/

Is It Time For Us To Take Astrology Seriously?

In an April marked by angry eclipses portending unexpected change, the ancient, long-debunked practice of astrology and its preeminent ambassador might be weirdly suited for the 21st century.

View this image ›

Illustration by Justine Zwiebel for BuzzFeed

Every Tuesday and Thursday from noon until 7 p.m., Bart Lidofsky pins a small plastic name tag to his shirt (“Bart Lidofsky, Astrologer”) and receives customers at the Quest Bookshop on East 53rd Street in New York City. After I wander up to him and introduce myself — I am there to have my natal chart read — he leads me to a little table in the back of the store and pulls a gauzy green curtain closed behind us. “For privacy,” he says.

Quest specializes in spiritual, esoteric, and New Age literature, but also sells crystals, runes, incense, divination equipment, mala beads, essential oils, candles, pendulums, gemstones, and “altar supplies.” It smells like church in here. You can picture the clientele — people who are comfortable pontificating about auras, people who know how to hang wind chimes. Lidofsky has been performing astrological readings for 20 years, and his bio contains a long string of bona fides: He’s a member of the American Federation for Astrological Networking and the National Center for Geocosmic Research, and frequently delivers lectures for the New York Theosophical Society. Or, as he calls it, “the Lodge.”

After we sit down, Lidofsky asks for the precise date, time, and location of my birth, and spends the next 45 minutes determining, in his words, “how things fit together.”

Before I leave, Lidofsky — who wears a robust white goatee and small wire-frame glasses — hands me his business card. It is pale blue, and features a photograph of Saturn alongside all the pertinent contact information. “Feeling lost in a difficult world?” it wonders in extra-large type. “Help is available.”

View this image ›

Until recently, I thought of astrology, when I thought of it at all, as frivolous and nearly embarrassing — a pseudoscience unworthy of consideration by serious people. I’m sure I felt at least partially implicated via my age and gender: A short screed in an 1852 edition of the New York Times called astrology’s audience “women and girls who are compelled to struggle as a living,” and declared the practice more odious than “the dozen other species of street swindles for which our city is famous.” In the late 1980s, when a former chief of staff published a provocative memoir claiming Nancy Reagan relied on a San Francisco astrologer to, as Time magazine put it, “determine the timing of the President’s every public move,” Ronald Reagan had to publicly insist that “at no time did astrology determine policy.” It was a major humiliation. Even the celebrity astrologer Steven Forrest has acknowledged his field’s dubious image. “I am often embarrassed to say what I do… Astrology has a terrible public relations problem,” he wrote in an essay for Astrology News Service.

But then there was this sense — suddenly, on the street — that astrology had credence. A 2013 New York magazine story claimed that “plenty of New Yorkers wouldn’t buy an apartment or accept a new job without an astral okay.” An occult bookstore opened on a dusty corner of Bushwick and was rhapsodically covered by the Times (its name, Catland, referenced a song by the British experimental band Current 93; its location in Brooklyn indicated a certain kind of culturally conscious clientele). People were talking frankly about their aspects. They knew which planets are in retrograde; they were jittery about eclipses. And it turns out what I’ve been observing anecdotally in New York — among my undergraduate writing students at New York University, in the press, between the otherwise high-functioning attendees of Brooklyn dinner parties — is supportable, at least in part, by statistics. According to a report from the National Science Foundation published earlier this year, “In 2012, slightly more than half of Americans said that astrology was ‘not at all scientific,’ whereas nearly two-thirds gave this response in 2010. The comparable percentage has not been this low since 1983.” While this sort of acceptance isn’t unprecedented, it’s still a curious spike. Astrology is gaining believers, and has been for a while.

In some ways, these numbers jibe with some broader cultural shifts: Whereas an astrological dabbler may have previously glanced at his horoscope in the newspaper while swirling cream into his coffee, there is now a vast and endless expanse of websites featuring complex, customized forecasts, some further broken down into insane and arbitrary-seeming categories (on Astrology.com, for example, you can consult a “Daily Flirt,” “Daily Home and Garden,” “Daily Dog,” or “Daily Lesbian” horoscope, among other variations). There is more access to astrology, just as there is more access to everything: A person can shop around, compare their fortunes, wait to find what they need.

When I speak to a former student, now 22, about the increase — it seems likely it’s at least in part attributable to her and her peers — she describes astrology’s mysteriousness as its most alluring attribute. She reads her horoscope every month, faithfully. Its inherent fallibility, she says, is precisely what makes it fun. For her, astrology is about feeling the strange thrill of indulging something (vaguely) supernatural, but it’s also about getting what she is really after, what we are all really after now: actionable, interactive information. These days, there aren’t many problems Google can’t solve. Except the problem of what happens next.

While folks her age are hardly the first group to feel the draw of the unknown, it also makes sense that a generation that came of age with the whole of human knowledge in its pockets might find the ambiguity of astrology a little welcome sometimes. For people born with the web, information has always been instantly accessible, so astrology’s abstruseness — and, ironically, its promises of clarity regarding the only real unknowable: the future — becomes appealing. This generation’s predicament, as I understand it, has always felt Dickensian: “We have everything before us, we have nothing before us.”

But then I’m reminded, again, that inaccuracy, or, at least, a belief in the fluidity of truth, is at the heart of the present-day zeitgeist: Our news is often hasty and unverified, our photos are filtered and retouched, our songs are pitch-corrected, our unscripted television programs are storyboarded into oblivion, and most everyone shrugs it all off. Astrology might not offer the most accurate or verifiable information, but at least it offers information — arguably the only currency that makes sense in 2014.

In that way, astrology seems perfectly positioned to become the defining dogma of our time.

View this image ›

The earliest extant astrological text is a series of 70 clay tablets known collectively as Enuma Anu Enlil. The originals haven’t been recovered, but copies were found in the library of King Assurbanipal, a seventh-century B.C. Assyrian leader who reigned at Nineveh, in what’s presently northwestern Iraq. (Some of the tablets are now held by the British Museum in London.) The Enuma Anu Enlil contains various omens and interpretations of celestial phenomena, and accurately notes things like the rising and setting of Venus. According to the historian Benson Bobrick, the Assyrians at Nineveh had distinguished planets from fixed stars and figured out how to follow their courses, allowing them to predict eclipses; they also established the lunar month at 29 1/2 days.

By 700 B.C., the Chaldeans — tribes of Semitic migrants who settled in a marshy, southeastern corner of Mesopotamia — had discerned that the planets traveled on a set, narrow path called the ecliptic, and that constellations moved 30 degrees every two hours. In his book The Fated Sky, Bobrick explains how “the twelve [observed] constellations were eventually mapped and formed into a Zodiac round (about the sixth-century B.C.), and the signs in turn (as distinct from the constellations) were established as twelve 30 degree arcs over the course of the next 200 years.” As early as 410 B.C., astrologers had begun making natal charts, noting the exact alignment of the heavens at the moment of a baby’s birth.

Bobrick eventually suggests that astrology is, in fact, “the origin of science itself,” the practice from which “astronomy, calculation of time, mathematics, medicine, botany, mineralogy, and (by way of alchemy) modern chemistry” were eventually derived. “The idea at the heart of astrology is that the pattern of a person’s life — or character, or nature — corresponds to the planetary pattern at the moment of his birth,” Bobrick writes. “Such an idea is as old as the world is old — that all things bear the imprint of the moment they are born.”

It’s at least hard to untangle the development of astrology from the rise of astronomy, and for a long time, the two fields were essentially synonymous; the divide between the supernatural and the natural wasn’t always quite so entrenched. As Bobrick writes, the “occult and mystical yearnings” of Copernicus, Brahe, and Galileo helped to “inspire their scientific work,” and astronomy and astrology remained close bedfellows until almost the end of the 17th century.

Nick Popper, a historian and author who has studied the intersection of science and mysticism, explains the relationship this way: “In Europe before the Enlightenment, for example, most individuals recognized a distinction between the two. Astronomy was the knowledge of the map of the stars and their movements, while astrology was the interpretation of their effects. But knowledge of the movements of the stars was primarily useful for its service to astrology. On its own, astronomy was most valuable as a timepiece.”

For early modern Europeans, astrology was undeniable and ubiquitous, a guiding force in various essential fields, including medicine. “Every noble court worth its salt had an astrologer on consultation,” Popper tells me. “Typically a physician skilled in taking astrological readings. Many brought in numerous people to help interpret significant events. These figures were [frequently] charged with determining propitious dates, anticipating future transformations, and using horoscopes to assess the character of all sorts of figures. This predictive capacity was not deemed a ‘low’ knowledge, as now, but seen as an utterly vital political expertise.”

Johannes Kepler, one of the forefathers of modern astronomy (he determined the laws of planetary motion, which allowed Newton to determine his law of universal gravitation; Kant later called Kepler “the most acute thinker ever born”), wrote in 1603 that “philosophy, and therefore genuine astrology is a testimony of God’s works, and is therefore holy. It is by no means a frivolous thing.” Three years later, in 1606, he declared: “Somehow the images of celestial things are stamped upon the interior of the human being, by some hidden method of absorption … The character of the sky flowed into us at birth.”

View this image ›

“There are so many misconceptions about astrology, it boggles me.” Susan Miller, arguably the most broadly influential astrologer practicing in America right now, is sitting across from me at a white-tablecloth restaurant on New York’s Upper East Side wearing a dark blue sheath dress, black tights, black knee-high boots, and Hitchcock-red lips. “The biggest is that it’s for women. I have 45% male readers. People just assume that it’s all women. It’s not.”

She is petite and precisely assembled, but not in a grim, bloodless, Park Avenue way. There is something openhearted about her, a vulnerability that borders on guilelessness. I find her instantly kind. We will sit here together for over four hours.

Miller founded a website called Astrology Zone on Dec. 14, 1995; the site presently attracts 6.5 million unique readers and 20 million page views each month. She released a new version of her smartphone app (“Susan Miller’s AstrologyZone Daily Horoscope FREE!”) late last year; her old app was downloaded 3 million times. Miller is hip to the way astrology functions online, having embraced the web from the very start of her career. She is active across most social media platforms, and fluent in the quick rhythm of virtual interaction, often acting as a kind of kooky, round-the-clock therapist. Offline, she employs 30 people in one way or another, has written nine books, and is aggressively feted by the fashion industry, a community in which she functions as an omniscient, beloved oracle.

Miller was born in New York, still lives in the city, and doesn’t have a whiff of bohemian mysticism about her. Instead, she presents as intelligent and detail-oriented, with none of the candles-and-crystals whimsy endemic to New Age bookstores. (A minor concession: Her iPhone, which beckons her often, is set to the “Sci-Fi” ringtone.) She appears legitimately compelled to help people, and offers an extravagant amount of free services to her followers. Of course, “free services” can be a potentially devious vehicle for other, less altruistic pursuits — and Miller does sell her books and calendars on her website, and frequently pushes a premier version of her app featuring longer horoscopes — but it is very, very easy to read and follow Astrology Zone without ever making an explicit financial investment in it. (Miller insists she makes “pennies” from the non-pop-up advertisements on the site.) I believe her when she says she considers her readers friends.