#but he recognizes that harry may not survive despite their efforts because even if he’s a damn good scientist. science isn’t magic.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Whumptober day 27

prompt: ‘I can’t walk.’

fandom: Salvation

title: Alone in the Cold

a/n: This is the last of the trio of connected stories (see days 25 and 26 for the previous stories) and the last of 2018′s Whumptober stories that have been completed for some time I just haven’t gotten around to posting them. I’m looking forward to this year’s whumptober though I haven’t decided on the fandom and I don’t quite know when I’m going to find the time to write given my work schedule. I barely find the time for a few hundred words lately. Anyway, enjoy this last story.

For the first time in months, he’s been left alone. They didn’t want to leave him, but there wasn’t a choice. Jillian had finally found work, but it often took her out of town for a handful of days at a time. Alycia and Liam also had work and routinely would be gone for periods. Normally, these were staggered so someone was always with him to help when he was too weak or tired to do anything. Harris was traveling, sent on a mission by the king, and Grace couldn’t afford to leave again without the king becoming suspicious.

He’d argued with the three teenagers, adults almost, before they left. He would admit to being weak still and growing tired far quicker than he liked, but he believed he was healed enough to be on his own. They wanted to delay their departure, talk with their employers or simply cut the travel time by taking a dangerous short cut. It wasn’t worth the risk and the gold they’d bring in would make his current struggles to survive on his own worth it. They were the town pariahs, mostly him, but also them by association. No help came to them during his illness and recover and none would now. No one would come by to check on him when no one had seen any activity in or around the house for a few days.

At least he thinks it’s been a few days since he fell. He knows he hit his head, which disoriented him and he’s pretty sure he passed out at least twice beyond the initial loss of consciousness. Then there’s the fever from being on the cold floor for who knows how long. It’s probably three days. He’s ninety percent sure, no eighty percent sure that it’s only been three days. It can’t have been any longer than that. Now, if only he could be as sure of when they’d return. He’s sure they told him, but the head injury or perhaps it was the fever, took that from him, which really is unfair. As far as he knows, he might be down here for another week before one of them returns.

He wakes later cold and hurting, still. And alone. It’s been a long time since he’s been alone and it’s not just his recovery that he’s thinking about. Even before then, when they’d be away from home for different periods of time, he never really felt alone like now. He missed them and looked forward to the whole makeshift family being back together again, but now, with the illness and loss of time, he feels the loneliness sinking in. He tries to remember them, to think of the fun they’ve had together to ward off some of that, but his mind is muddled and holding onto memories is difficult. They wind up mixed together, the good with the bad and it seems the bad win out often. He remembers drowning, but it shifts to Liam or Alycia being the ones caught under the weights and waves, tumbling deeper and deeper down the river until he loses sight of them.

The sun is setting, bringing another round of darkness and coldness which won’t help the memories. He alternates between freezing and burning up. The coughing started last night or maybe the night before. His chest aches even as it grows more difficult to cough. Breathing is hard.

He can’t stand, he tried a lot at first, but his muscles are weak and his bones ache at the pressure he puts on them. Some time ago, though, he managed to push himself to his side, tilting forward until he’s nearly laying on is chest. An arm and a foot stop that tumble. The position saves him when he coughs hard enough to bring up bile. There’s nothing in him to actually throw up. Bringing up acid is worse; it burns and the effort makes him hurt worse.

When will they come home?

He wakes to pain, shooting pains up his back and legs. He’s on his back and there are arms under him. He starts, causing the pain to spike and he can’t hold back the cry that comes. There’s some talking, but he can’t focus on it.

“I need to get you off the floor, Darius.” It sounds like Harris. Harris shouldn’t be here. Where’s Liam or Alycia? Why’s Harris here?”

“Because I got a feeling something happened to you,” Harris says.

Maybe it’s the fever that’s messing with his mind, making whoever it is say that it’s Harris. The town people don’t like him and they’ve come after him before. Maybe it’s them again. He squirms away, moving despite the ripples of pain the come from the effort.

“Darius, it’s me. Harris. I promise. Open your eyes and you’ll see.”

Darius considers it, but he likes the idea that it’s Harris, not one of the townspeople come to hurt him.

“If I was a townsperson come here to hurt you, don’t you think I’d have done that already?” There’s a sigh that Darius recognizes. No one can sigh like Harris.

“Finally,” Harris says. “Do you believe me now?”

“Yeah,” Darius says, voice weak.

“Good because I need to get you off this floor before you get sicker. Can you get up?”

“Do you think I’d… still be down here if I could?” Darius coughs. He opens his eyes finally, trying to fix Harris with a glare, but he’s not sure it works. In the candle light, he knows Harris can see how pale he is and the glaze to his eyes.

“How long have you been down here?”

“I don’t know,” Darius says, feeling lost. All along he knew that he was losing track of time, but it’s another thing to admit to it. At least Liam and Alycia aren’t here.

“They should be here. Where are they?”

“Work.” Darius wonders what’s going on. Is Harris reading his mind?

“You’re speaking your thoughts. Again. Now, let’s get you up and in some dry clothes. You’re already ill, but let’s see if we can stop it from getting worse. Are you able to help me at all in getting you standing?”

“Maybe. I think I’ve been down here for a while, Harris.” Some worry seems into his raspy voice.

“It’s time to get you up then.” Harris waits a moment until he sees Darius ready himself to be lifted. He’s always been stronger than Darius and while lifting him might’ve been a strain, it was never impossible. After the curse, however, with the weight loss from being ill and bedridden for so long, lifting him was only a matter of avoiding the aches and pains. It had been getting easier in the last month with the broken bones and burns healed, but he is back to being careful tonight.

Darius tries to hold back the gasps and cries of pain as Harris lifts him off the floor but halfway to the bedroom, he’s lost the battle. He mutters an apology in between gasps of pain that turn easily to coughs.

“It’s fine, Darius,” Harris says. “You don’t have to hold back.” Harris opts to pick up his pace, setting Darius down on the bed in the dark room. He leaves him for a moment, partly so that Darius has time to rest, but also to get the candle so he can see what he’s working with.

Back in the bedroom, he decides his first task is to get Darius into dry clothes. Darius helps as much as he can, but his time on the floor has sapped him of whatever strength he’d gotten back during his recovery. By the end, even the cries of pain have weakened and his eyes are barely open. The coughing is less frequent, but his breathing has turned more strained.

The change of clothes also allows Harris to check on any injuries. There’s some bruising and cuts, which he takes care of, but it seems the worse outcome of Darius’ accident is a cold that has chosen, quite dangerously for a man who’s not quite mobile, to settle in his lungs. Leaving Darius dozing under a few layers of blankets, Harris goes to get the fire going so he can heat up some bricks to help warm Darius up quicker. Even with the fever heating him up, Darius is lacking in body heat. Bricks added into the blankets will help. With luck, they may be able to cut the illness short and prevent the lung infection from worsening. In his condition, it would be all to easy for such an infection to take him.

It takes a while for the fire to get going and the bricks to be warm enough and while he waits, he goes back frequently to check on Darius. He’s not asleep, but awareness is largely gone. He moves when Harris checks on him, but he never opens his eyes or says anything.

When the bricks are warmed enough, Harris carefully pulls them out and carries them into the bedroom. As he’s arranging them under the blankets, wrapping them so Darius isn’t burned, the man stirs.

“Thanks,” he says, voice raspy.

“You’re welcome.” Harris finishes with the last brick and moves to sit on the edge of the bed by Darius’ chest. He checks his temperature, not surprised that there’s been no change. “How’re you feeling?”

“Sick, again.” He sighs, coughing when that disturbs his breathing. Harris eases him up a little to make the coughing easier. When Darius is done, he sets him back down before going looking for another pillow. He takes the two on the other beds, Alycia and Liam’s, using those to prop Darius up. Darius thanks him again, relief evident even as he’s working on getting his breathing under control.

“It may not be as bad as you think, Darius,” Harris says once Darius seems able to keep up conversation.

“Neither of us knows how long I was laying on the floor, Harris. I’m cold, feverish, and… there’s a rattle in my lungs. None of this looks… good.”

Darius is normally a positive person, but Harris noticed that dwindling over the last several years as his run ins with the law and angry town folk increased. The past few months dealing with recovering from the curse seemed to take the last of that positivity away. He wouldn’t just let Darius give up, though. He isn’t ready to lose him.

“So you’re just giving in? What about your kids,” Harris asks knowing that it’s a rather low blow, but he hopes that it works.

“Alycia and Liam will be fine. I’ve done what I can. They’ll probably be better off without me.”

“We are talking about the same Liam and Alycia here, right? The young girl who ran all the way to a strange kingdom looking around for the one person who could help you? And what about Liam? You do remember how hard he searched to find a witch who would help you. Jillian was the only witch who chose not to follow the order of the curse and he travelled miles to find her.”

“I’m useless, Harris,” Darius admits after a pause. “The three of them are out there working, working hard for people who won’t ever appreciate their true talents while I get sick because I can’t keep my balance.”

“Other than the recent injuries and the townsfolk, do you enjoy what you do? Do you enjoy your life?”

“Not counting that and the law, I love it all. The experiments, the successes and the failures. Seeing Liam and Alycia grow up happy and free of their pasts, yes, but I’m far too much of a burden. Even sometimes a good horse has to be killed if it’s injured so severely.”

“Damn it, Darius, stop being so dramatic. You’re not some prized horse. You’re part of our family and you have two kids who, though grown up, still depend on you. Not to mention the friends you have that aren’t ready to see you put out to pasture, to go with your stupid horse idea.”

Darius doesn’t speak, looking away from Harris.

“Look, we both know that life isn’t easy, especially yours as you seem to attract trouble, but I don’t think you’re ready to give up yet. I think you’re exhausted and empty and justifiably so. You don’t have to get better tonight, but you do have to find the reason to keep going. And if it’s not for yourself right now, then make it for us. Keep going on for us.”

“You really think that’ll work?”

“For the moment, yes. We’ll get you back to your old annoying, cheerful, moody self soon enough. But for now, you can keep going for us because I think I can speak for everyone else when I say we’re not ready to give up on you yet.”

“Okay.”

“Okay?”

“Yes, okay. I can’t promise anything, but you’re right in one thing. I don’t have the energy to keep going on, but I don’t want to give up. I can find the energy for you guys.”

“I’ll hold you to that.”

“I know.”

“Now, you should try to get some sleep. I’ll wake you later with some broth to help keep your strength up.”

“Thank you, Harris,” Darius says as he closes his eyes.

“Anytime, Darius. Anytime.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

From The Bill from My Father: A Memoir by Bernard Cooper

Light shot from the lens of the projector and burrowed through the room. It flickered over the furniture and gave the dark a restless depth. I watched dust motes whirl and collide in the beam, and this bright turmoil, this erosion of countless powdery grains, was proof of a fact I knew all along but hadn’t grasped until that moment: the world was being ground to bits. I was still transfixed when I heard my father tell me to snap out of it and pay attention to what was on the screen.

In a wood-paneled office, a stout black woman sat across a desk from a white man, whose bony hands were folded atop an ink blotter. A pen holder slanted in his direction, and next to it a name plate identified him as a judge. His lips moved nonstop, but the film was silent and I couldn’t make out a word he was saying. All the while he stared into the camera with the unnatural expression of a person who’d been told to act natural and not stare into the camera. The woman paid respectful attention, leaning forward once or twice in a futile effort to interrupt. She clutched under one arm a leather-bound book that was either a Bible or a volume of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. On the desk beside her lay an overstuffed purse.

The judge was still yammering when the purse, without so much as a twitch of forewarning, stood up, wavered on two spindly legs, and walked toward him, though “walked toward him” suggests that the purse had a particular destination, whereas its halting progress was more along the lines of two steps forward, one step back. For a moment I wondered whether it was a marionette, though I couldn’t see strings, and besides, who in their right mind would make a marionette that looked like a staggering handbag? No, the purse’s senselessness hinted at the possibility that it once possessed sense and now was trying to get along without it. This was animal motion, too reflexive with muscle and nerve to be anything inanimate.

The judge’s mouth stopped moving when the scruffy whatever-it-was lurched into his line of vision. He gave it a wary, sidelong glance, ready to react should something unexpected occur, which, considering what had occurred already, would have to be inconceivably strange. That’s when the camera slowly zoomed in, moving as if it, too, were an animal, a predator hunting its unsuspecting prey. It slid between the woman and the judge, intent on the mound in the middle of the desk. Feathers slowly came into focus. Wings bristled as the creature breathed.

“What is it?” I whispered.

“Watch,” said my father.

He had been a witness to the actual event, but because I didn’t know this yet, his Watch was like a magic command that caused what happened next to happen. A stump emerged from the thing’s right side, which until that point had looked identical to its left. The stump pivoted toward the camera and paused long enough to reveal its severed end. A tunnel of tendon and pearly bone led inside the creature’s body, the sight no less gruesome in black-and-white. The woman’s fingers descended into view, holding an eyedropper by its rubber bulb. She squeezed until a bead of clear liquid glistened at its tip, then angled it toward the cavity. The stump strained upward.

The idea of watching the creature being fed made me speechless, queasy. How much closer would the camera zoom? What kind of contractions would swallowing involve? That blind, groping, hungry stump was the neediest thing I’d ever seen. Leaving the room was out of the question; my father would view my retreat as rudeness, or worse, as proof that I was a delicate boy unworthy of paternal wisdom. I couldn’t have fled anyway; sunk in the possessive depths of the couch, I could barely move.

The droplet wobbled.

“Sugar water,” said my father.

Not until later that night, after unsuccessfully begging myself to please stop thinking about the gaping wound, did I realize that sugar water referred to the solution in the eyedropper. At the time, however, my father might as well have said spoon clock or hat bell for all the sense his comment made.

The pendulous droplet fell into the stump. Then another and another. For all that creature knew it had started to rain, and the rain tasted sweet. As the woman doled out the final drops, words scrolled up the screen:

There is hope for you too

when you see how divine power

keeps Lazarus alive!

Mrs. Martha Green’s decapitated fowl

lives to become

THE MIRACLE CHICKEN!

This 20th century wonder brings a possibility

of new life and new healing

to an army of believers.

It’s all TRUE!

This movie is AUTHENTIC!

The woman’s purse was a headless chicken. I might have uttered this fact aloud since it came as such a great, if short-lived, relief. My father had used the phrase “like a chicken with its head cut off” to describe all manner of frenzied activity, applying it to bad drivers and harried salespeople and even to my mother, who cooked dinner in a state that could be described either as motherly gusto or stifled rage. Every time I heard the expression, I pictured the figurative chicken running around a barnyard in circles and spurting a geyser of blood before dropping dead in the dust. Dropping dead forever, I should add, because it never occurred to me that a chicken might survive its execution, give hope to humans, and star in a film. Wasn’t a head indispensable?

Dad towered beside the projector, his figure awash in flickering light. He loosened his tie and unbuttoned his collar.

“There’s your old man,” he said, pointing to the screen.

A crowd dressed in Sunday finery milled around the front lawn of a clapboard house. People stepped aside to let my father pass, a sea of hats parting before him. Mrs. Green trailed in his wake. She cradled Lazarus in her arms, careful not to let the bird be jostled and also not to hide it from view. Making his way through the crowd, Dad cast frequent backward glances to make sure Mrs. Green and her bird were behind him. Photographers jockeyed to get a good shot. Reporters frantically scrawled on their notepads. Men and women craned their necks, some letting children straddle their shoulders to get a better look.

Mrs. Green refuses to hand Lazarus over to the S.P.C.A. despite a court order from Judge Stanley Moffatt. Her attorney, Edward S. Cooper, claims the bird is “an act of providence for the benefit of all mankind.”

The throng of spectators, two or three people deep, waited behind a listing picket fence as my father escorted Mrs. Green into a yard overgrown with blooming hibiscus and bougainvillea. She seemed at home there, so I supposed the yard was hers. It may have been an effect of the grainy eight-millimeter film, but this ramshackle Eden glowed with an ancient, paper-thin light, as if the screen had turned to parchment. It wouldn’t have surprised me if one of the bushes had burst into flame and spoken in a holy baritone.

My father carried his monogrammed briefcase by his side. He and Mrs. Green walked to a small table that had been set up on a patch of grass. They glanced nervously at the camera, humbled by the expectant crowd. Black and Caucasian faces looked on, soldiers in an army of believers. Mrs. Green gazed almost sorrowfully at the bundle in her arms. Hesitant to let it go, she inhaled a bracing, duty-bound breath, then gingerly lowered the chicken onto the table. Its feet dangled like scrawny tassels, and once his legs touched the table top, they buckled without a hint of resistance.

I’d learned over the years to heed my father’s impatience as one would a storm warning, and watching him stand there on-screen, I recognized signs of impending anger as he glared at that motionless bird. A prominent vein bulged on his forehead. His grip on the briefcase tightened. I could almost hear him thinking, Of course this would happen. What did I expect? Just when things were going my way, fate sticks out its leg and trips me. He and Mrs. Green stood side by side and I thought I saw him nudge her with a silent ultimatum: Do anything you have to do, but get that goddamn poultry to move! You want people thinking this is some kind of hoax? I felt the weight of his briefcase in my hand, his hot collar encircling my neck, his heart thumping inside my chest. “What if it doesn’t move?” I asked. Meaning if it didn’t, would we both be ashamed?

He looked worried in the movie but not in real life. He smiled faintly and crossed his arms.

“That bird’s as alive as I am,” he said.

Silent concern rippled through the crowd; a few people used their hats as fans or consulted hefty, gilt-edged Bibles. Mrs. Green patted her forehead with a hankie. The twentieth-century wonder looked about as wondrous as a feather duster.

What were my father and Mrs. Green to do? They couldn’t rouse it by snapping their fingers or waving their hands in front of its face. Maybe they could communicate to the bird through touch, the way Annie Sullivan had tapped the word water on Helen Keller’s hand. Of course, it wouldn’t look good if my father and Mrs. Green started poking at the chicken; you can’t badger a miracle to happen and then expect people to marvel when it does.

I gasped when the chicken sprang to its feet, wings thrashing the air. Feathers bristled when it stretched its stump. The camera pulled back as if rearing in fear and astonishment. People in the background flung up their arms in a mute hallelujah. Mrs. Green’s unbounded joy caught my father off guard; he swayed in her embrace, eyeing the chicken over her shoulder. Big letters bellowed from the screen:

Cock-A-Doodle-Do!

My father’s high, delighted laughter rose over the sound of the projector.

“Is that chicken something?”

“Rooster, you mean?”

“Chicken,” he corrected, annoyed that I might have missed the big finish, might have been distracted when water turned to wine.

“Chickens don’t crow,” I told him.

“What?”

Tricky business, repeating a statement that belonged, I realized too late, in the “back talk” category. I scrambled to match oinks and tweets and moos with the appropriate animal, only to discover that the correspondences were more debatable than I’d realized. My rooster remark sounded arrogant now, and possibly untrue. “Do roosters crow?” I found myself asking.

The projector lit my father’s face from below. His chin and brow were islands of light, his eye sockets deep, unreadable. “Supposing a chicken doesn’t crow,” he said. “Then this one’s more of a miracle.”

* * *

Remember the headless rooster?” I asked.

My father leaned toward the microphone.

“Chicken,” he insisted, then sat back in his chair.

“But the chicken supposedly crowed, Dad. And chickens—I’d stake my life on this—don’t crow. They cackle. Or cluck?”

The querulousness in my voice, and the irritation in his, had been preserved for thirty years.

“Look,” he said, “if the client says a chicken crowed, the chicken crowed. Mrs. Green heard it. So did half the people who were at the press conference that day. Maybe they were in a religious state. That kind of thing has never happened to me personally, so I wouldn’t know. All I know is that Mrs. Green buys the chicken from a local butcher, takes it home for dinner, puts a pot of water on the stove, and when she goes to pluck the thing, it stands up and starts strutting around the kitchen like this was just another day on the farm. She’s standing there gawking when a voice comes out of nowhere and tells her to name the bird Lazarus, and she hollers, ‘Praise the Lord.’” Here my father lifted his arthritic arms as high as he was able, the jumpsuit stretching taut across his belly. “She gets on the phone to call her friends, who call their friends, and so on, and pretty soon people are showing up at Mrs. Green’s house in droves, lining up just to get a look at the thing. Being your enterprising type, she starts charging admission. Can you blame her? She sees a brass ring and she grabs it. That’s America.”

Book “The Bill from My Father: A Memoir” by Bernard Cooper

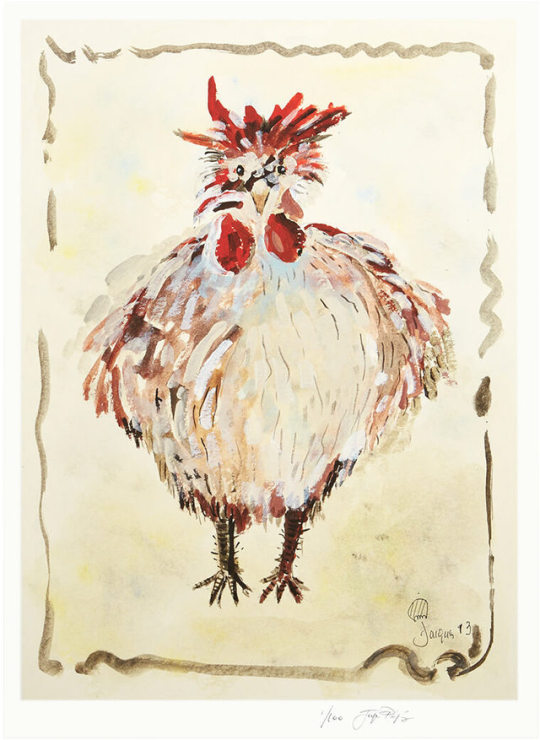

Painting” “The Cock” by Chef and Artist Jacques Pepin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Optimism When Things are Easy is a Sham

By Don Hall

"For mine I am an optimist by nature. My reading of history is that the world has always stepped back from the edge of disaster. Against all odds, here we are, alive and kicking." — Rabbi Laibl Wolf

Optimism isn’t merely hope. It isn’t happiness or a cheery disposition.

Optimism is an act of resilience against the brutal harshness of living the existential crisis.

It’s darkest just before the dawn implies that there will be a dawn. What if there won’t be? What if it’s just more darkness? If the implacable timpani of human greed, a self correcting planetary environment, and the algorithm that defines our modern interaction has no end, should that result in giving in to the despair?

As optimism is a breeze when things are going your way, despair is the path of least resistance when things turn to dire. Seeing through the mist at a better future takes effort and commitment like a solid marriage or a massive novel you’ve committed to writing. It’s a project to be managed not a feeling to languish within.

One cannot truly call himself an optimist who refuses to see the horror. Pretending that people are essentially kind and generous is stuffing the ostrich head in the sand. People are apes with higher brain functions and follow the rules of the jungle. Tribalism, essentialism, war for resources, the history of brutality of all humanity goes far beyond Hannah Jones’ 1619 Project. Taken in whole, we aren’t a very enlightened and forgiving species.

Further, optimism is an individual choice. It’s not something that can be enforced but it is something that can be inspired. The American Experiment, despite its many missteps and flaws, is grounded in a belief that humans can govern themselves justly and effectively. Given the larger picture, belief in democracy is only slightly more delusional than the guy playing slots so he can pay his rent. The odds are astronomically against success and yet the choice to persevere is made.

“We have to reject the notion that we’re suddenly gripped by forces that we cannot control. We’ve got to embrace the longer and more optimistic view of history and the part that we play in it. If you are skeptical of such optimism, I will say something that may sound controversial. I used to say this to my staff in the White House, young interns who would come in, any group of young people that I met with, and that is that by just about every measure, America is better, and the world is better, than it was 50 years ago, 30 years ago, or even 10 years ago.” — President Barack Obama

This isn’t just hopeful bullshit. This is completely pragmatic, data-driven reality.

Despite the horrors of police killing unarmed black men in viral videos that seem to crop up every other day, the number of unarmed black men killed or injured by police in America has decreased dramatically in the past five years.

Despite the heartbreaking realities of homelessness in America, more people have more access to food and healthcare than ever in the history of the country.

Despite the histrionics of the trans-activists burning Harry Potter books as an expression of (quasi-authoritarian) outrage, the LGTBQ + community is at a unique and unprecedented place of societal acceptance in America.

That’s not hopeful thinking. Those are cold, hard facts. Optimism is not rooted in fantasy but grounded in seeing a fuller picture and recognizing progress when it smacks you in the face. Ignoring the macrocosm and expanding the microcosm’s importance is the choice of children. A child only sees how things affect himself; an adult comprehends that there is more to see and a larger consequence to that ego-driven hyperbole than self-interest.

It’s darkest just before the dawn. There’s the rub. What if there is no light at the end of the tunnel? What if Trump manages to maintain his seat in the Oval Office? What if he packs the SCOTUS with a six-three conservative majority? What if we go to war with China? What if the planet continues the onslaught of climate disaster? If history tells any story at all, it is this:

There is always a dawn.

In the closing moments of the horror film The Mist, after enduring a terrifying night of uncertainty and surviving monsters (both genuine monsters and the monsters humans reveal themselves to be under extreme fear and rage), Thomas Janes is finally escaping. With him is a woman and a child. Once the vehicle runs out of gas and they are still enveloped by the impenetrable mist, they hear what they believe are more monsters. In that moment of despair Janes decides that dying by his hand is better than facing the monsters so he shoots both the child and the woman. As he prepares to kill himself, the monsters he fears turn out to be soldiers and the true horror was his giving into the fear.

If, after the pandemic is under some semblance of decline, the economy starts to find its footing, and Trump is in prison (either in 2022 or 2026), you gave in the despair you’re gonna feel pretty fucking stupid and then spend the rest of your days justifying your shortsighted pessimism.

If you mourn Justice Ginsburg and laud her achievements in changing America for the better yet respond to injustice by throwing cans at cops and justifying looting and destruction, you will have missed the lesson of her life. She never screamed in the streets or stomped her existential adolescent feet to express her desire for a better future. Ginsburg focused her rage and slowly, deliberately, and effectively worked through the democratic system she believed in and fomented lasting change.

Recently, a poll indicated that roughly two-thirds of Zoomers did not know that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. The tragedy is not their myopic narcissism and pathological disregard for history. It is their dismissal of those who survived the Holocaust because they refused to give in to despair.

When you see someone who has one of those death camp tattoos on their arm you are witnessing a genuine, tried and true, bona fide optimist.

Optimism is hardest when things turn to shit but it is then when it is most necessary.

0 notes

Text

Nothing Worse Than Jury Duty

A drarry drabble. sorry i gave the English wizarding world jury duty ...

There was something worse than jury duty, Harry Potter realized as he stumbled into the dark chambers of the court. There was jury duty with Draco Malfoy.

Harry had been running late, of course. He blamed that on the fact that he’d been pretending his summons wasn’t a real thing. It had arrived two weeks ago, warning him of the upcoming requirements. Despite several -- embarrassing in retrospect -- attempts to set it on fire, it remained crisp and somehow judgmental of his efforts to dodge the duty.

So when the day finally arrived, he’d slept through three alarms, burnt his toast and spent an extra fifteen minutes looking for his keys before he remembered he was a wizard and could just accio them. He was also pretty sure he was wearing mismatched socks.

And, because this was his life after all, Malfoy looked flawless and composed. Stunning, really. He was definitely wearing socks of the same color. Harry didn’t even need to see them to know that. Perhaps they even coordinated with the man’s deep emerald robes that had not a single wrinkle in them.

Harry smoothed a hand over his own plaid button down that he’d thrown over a paint-splattered black t-shirt. The jeans he’d been able to scrounge off the top of his laundry basket were battered and ripped and there was a hole right below his butt cheek that he was just pretending wasn’t there.

There was nothing he could do about it now, though. Resigned to his fate, he took the only remaining seat -- of course it was next to Malfoy -- ducking his head to avoid the judge’s disapproving glare.

“Thank you for joining us Mr. Potter. As I was saying …” the judge, replete with a heavy, old-fashioned white wig, continued. It made him feel all of eleven, which was appropriate considering his school boy nemesis was perched beside him, smirking.

They may have long-moved on from the days of stinging hexes and nasty slurs -- and god so much worse -- but there was still something that sat heavy and charged between them. Harry was now just able to recognize the origin of it a little better than he had years ago.

“Potter,” Malfoy said as his greeting, not even turning to look at him. Which Harry was glad about. It gave him a moment to take him in and adjust to his nearness. It wasn’t like they avoided each other these days. The wizarding world was a small one. They ran in the same circles, had many of the same friends. Malfoy even came to pub nights a couple times a month. Harry would have thought he’d have gotten used to the man by now. But no. His palms were already sweating.

It was just that he was so pretty. And smelled really fucking good. Like lemons and soap. Harry let his eyes trace over his sharp jawline and down the long column of his pale throat. He wanted to bite down into that soft space above Malfoy’s delicate clavicle. The thought shook him out of his trance, and he sucked in a deep breath. Which immediately backfired when the waft of citrus hit his nostrils.

There was a faint blush cresting along Malfoy’s cheeks. “Can I help you, Potter?” Even the way his cultured rasp rolled along Harry’s name sent shivers of anticipation down his spine. He wanted to hear it whispered to him. Moaned out between those lips. Well, ideally it would be Harry instead of Potter, but beggars couldn’t be choosers.

Harry had no retort, so he just mumbled something that was definitely unintelligible and dragged his eyes off Malfoy. Fucking jury duty.

Somehow despite his huge and raging crush on the man, Harry was able to hide it. It involved a lot of plotting -- such as coming up with creative ways of avoiding sitting right fucking next to him unexpectedly -- and well-timed trips to the loo. Sometimes for a wank. But those were only in his weakest moments. Usually he could at least wait til he got home to imagine finally getting his hands and mouth and tongue all over that lithe, beautiful body.

This wouldn’t do, though. If the thorough directions on the summons were to be believed - and why wouldn’t they be? - he would be stuck in this little room with Malfoy for the next three days waiting to see if they were picked for the jury. Now that he knew they were both in the pool, he couldn’t well avoid him either. That would be rude.

Bloody fucking hell. How was he supposed to get through this without Malfoy realizing? Merlin, it was hopeless.

It wasn’t that Harry thought he’d mock him, anymore.

In the years after the war, Malfoy had matured. His humor tended to run a little closer to dry sarcasm than others’, but the malice behind it was gone. That had been stripped away in the brutal days when none of them knew how to move forward, but somehow were forced to keep surviving. It had been stripped during the weeks Malfoy returned to help rebuild Hogwarts in the brutal heat of the summer following the battle. It had been stripped away by the at first tentative attempts at apologies that turned into actual friendships.

What was left was Draco. Strong and broken and insecure and not quite kind but not quite an asshole either. What was left was a man Harry actually admired. Far too much for Harry’s own good.

So, he wasn’t worried Draco would mock him when -- not if, because let’s be honest, that’s just how things were looking for him today -- he found out. It was the fear of seeing pity in Draco’s eyes as he let him down gently. That would be too much to take. Harry would have to become a hermit. Perhaps even move to a different county. Not that he was being dramatic or anything.

“You didn’t come to the last pub night,” Draco said, just loud enough for Harry to hear. The interview portion had started with an elderly witch in a large sparkly purple hat who had to use an ear trumpet and still made the barrister repeat every question. This was going to be awhile.

“You noticed?” Harry asked, swallowing hard.

There was a pause, as if Draco just realized he had just admitted to something. The rose pink on his cheeks deepened and Harry thanked Merlin for his own swarthy complexion. “Ron had wanted to challenge you to some ridiculous drinking challenge. That’s all.”

Harry laughed under his breath. “Did anyone take him up on it.”

“Seamus. He ended up in a skirt singing Celestina Warbeck’s latest single on top of the bar.” Draco smiled fully this time, turning to look at Harry for the first time since he’d arrived. Their eyes caught and held and suddenly there were just sitting there grinning at each other. Close enough for Harry to see all of the thick lashes that blinked over liquid silver eyes in a long slow sweep.

“Rookie move, Seamus,” Harry murmured, his eyes dropping to Draco’s lips when his teeth dug into the soft flesh there. Fuck. “Don’t bet against Ron.”

There was a beat of silence and then Draco shifted to face the front of the room once again.

“Hot date, then?” he drawled.

Ha. That was funny. Hermione kept trying to set him up with various friends and co-workers, but the last one he’d given into had spent the entire night talking about obscure troll history and then had snuck out when the bill had come, leaving Harry to cover all of it while trying not to burst into flames from the mortification of being ditched. The waiters’ expressions had been the worst part.

That had been three months ago and he’d firmly put his foot down over any more blind dates. Which left him spending most nights with a nice glass of red wine and a contrary house elf for company. He was kind of okay with it, too. Unless, of course, a particular blonde bloke felt like joining him. He wouldn’t mind that.

“Um. No,” Harry pressed his palms into the rough fabric of his jeans. “I’m at the end of a big renovation project. Sometimes I get a bit carried away, forget about the time.”

Draco’s lips tipped up. It looked almost....fond. But Harry must be imagining it.

“That’s right, you and your houses,” Draco said like he was remembering something he’d forgotten. Harry knew that Draco knew all about it, though. Draco even asked him about his latest projects with some frequency.

Everyone after the war had been pushing him to become an auror. He was made for it. Even he thought so. But once training had started, the idea of years and years of continued violence and dark magic became a nightmare instead of a dream realized. He’d quit one month in and traveled for a bit.

After he returned to England, he’d been a bit restless until he’d started tackling the monster that was Grimmauld Place and discovered that swinging a sledgehammer into actively complaining walls made him feel better than anything else in his life.

It was like free therapy. Where he didn’t have to talk about all of the things that lurked in the darkest corners of his mind and woke him up at night covered in a cold sweat.

“Yeah,” Harry said. Dumbly. Merlin, it wasn’t like he thought he was the wittiest person ever, but this was a low point. He literally could not think of any other words to say.

The smirk was back. But then Draco surprised him. “I’d like to see one, some day. If you wouldn’t mind.”

Harry’s mind went blank. And then everything rushed back in, a roaring wave of thoughts and ideas and sounds and emotions. “I’d love that. You can even…”

Draco glanced at him, one slim eyebrow lifted. “Yes?”

Come on, Potter You defeated Voldemort. You saved the wizarding world. You’re a fucking Gryffindor. This shouldn’t be that hard.

He took a deep breath, and there was that hint of lemons again. “Tonight? And we could get dinner afterward if you want.” He said it. He said it quickly so that it was all one word, but he said it.

The soft, gentle smile crinkled the lines around Malfoy’s eyes. “That sounds perfect. Harry.”

They both turned back to watch as the elderly witch was finally dismissed from the stand and a young wizard with a spiky mohawk that was changing colors took her place.

Draco’s arm pressed against his and neither of them moved to put distance between them. The warm heat radiated through the rest of Harry’s body and he tried not to think about what might come after dinner.

Perhaps jury duty wasn’t so bad after all.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Our lives are a mess. Reading “The Blazing World” I’m reminded of a performance by the brilliant artist Bobby Baker I once attended. She delivered a monologue about her life that included a scattering of memories, disappointments, happy highlights and concerns about contemporary issues. With each subject she added dry ingredients into a pot collecting them all until it overflowed. She poured it over herself till her clothes, hair and face were completely soiled and a floury cloud floated around her head. She stared around at the audience solemnly proclaiming: “What a mess!” The sight was comical, but through the manner in which she delivered the monologue it was understood that her whole being had tragically unravelled. In a similar way, the life of this novel’s central character Harriet Burden (or Harry as many intimates call her) is a mess. The narrative reflects her state of mind as it is a loose collection of fragments: personal notebooks, statements from family, friends and an art critic as well as gallery show reviews. It is an assemblage which is incomplete, meandering and circuitous. But in its fragmentation it becomes a truer portrait of a person than any straightforward narrative could hope to represent. This account is a more meaningful reflection of the many facets of personality and the multi-layered ways in which a person can be viewed.

Harriet is an artist in her sixties living in New York City who is frustrated with the way female artists don’t get taken as seriously as men. She devises a grand artistic project to expose this prejudice and take revenge by exposing the art world’s sexist nature. Three living male artists are selected by her to present original shows as their own work when really Harriet is the true artist. Only after the third show does she reveal her grand prank through an indirect route by writing an article for an obscure art publication under the pseudonym of a fictional critic. With so much subterfuge going on, people naturally question whether Harriet has made all this up or if she’s created one of the most ingenious artworks of our time. The book begins with a preface from someone attempting to answer this riddle by compiling the various accounts about the late Harriet Burden into a somewhat chronological order. This may all sound exhaustingly convoluted, but it’s actually quite straightforward to follow the story once you get the gist. At it’s heart, “The Blazing World” is really about the more profound question of personality.

It’s as if “The Golden Notebook” were written by Susan Sontag, but of course the writing is totally unique and purely the innovation of Siri Hustvedt. It’s a brilliant assemblage of knowledge full of clever word play, innovative narrative technique, psychological insights and dramatic twists. It’s sparked by a feeling of real anger: about our complacency to accept things as they are when there has been so much hard intellectual work dedicated to progress. It’s a passion which burns on every page. Harriet is a voracious reader and thinker. Therefore, her notebooks are layered with a heady amount of references to great works by psychologists, artists, philosophers, writers, scientists and theologians. I love it when I finish a novel with a long list of books and authors that I want to look up and learn even more from. This novel has given me a list longer than most. But this isn’t a showy intellectual feat by Hustvedt. This knowledge is layered into her central character’s reasoning because it relates to the ontological issues which stir her heart and cause her to create such an elaborate complex deceitful artistic project.

Going even further, accounts from both Harriet’s friends and enemies offer counter arguments to the statements Harriet makes. For instance, the primary question at the centre of this novel asks if art by women is taken less seriously. On one side a psychoanalyst named Rachel said: “With almost no exceptions, art by men is far more expensive than art by women. Dollars tell the story.” Harriet echoes this thought when she says: “Money talks. It tells you about what is valued, what matters. It sure as hell isn’t women.” However, an art critic named Oscar states: “To suggest, even for an instant, that there might be more men than women in art because men are better artists is to risk being tortured by the thought police.” Whereas a bi-racial artist named Phineas muses upon the superficiality of the art in general world concluding that: “It was all names and money, money and names, more money and more names.” Later on Harriet suggests that the question of gender isn’t even her central preoccupation: “it’s more than sex. It’s an experiment, a whole story I am making.” Points of view jostle against each other until a multi-layered portrait of this and other questions are presented and the reader must come to their own conclusions.

The accounts which struck me the most in this novel are Harriet’s own recorded in her various notebooks. One of her preoccupations is her fight against time, against being marginalized forever as a footnote rather than having made a grand statement about life. She states: “I am writing this because I don’t trust time.” Her tireless efforts to create and communicate show how desperately serious she is about the issues she raises. Having spent her life living somewhat quietly as a wife and mother she has reached middle age and is now keenly aware that if she doesn’t make her statement soon time will defeat her. With great precision she observes that: “Time creeps. Time alters. Gravity insists.” The razor-sharp language used cuts right to the heart of what she means and is merciless in its exactitude. Through short dramatic fragments of memory she recollects scenes from her past: her father who didn’t want her, the discovery of her husband’s infidelity, the cruelty of schoolmates who misunderstood her and finally the pernicious betrayal which threatens to dismantle her grand artistic project.

There is plenty of humour to be found in this novel as well. The comedy is of a highly intellectual sort – plays on words and jokes that need a footnote about a French cultural theorist to fully understand them. But there is also humour of a more bawdy nature cutting down the ridiculous importance men place on their manhood “He worries over semen flow, a bit low, the flow, compared to days gone by. You’d think he had walked around with a volcano down there for years, conceited man” and a satirical humour that slices apart Harriet’s perceived enemies in a merciless way. Harriet pokes fun at the art world and its parade of ego-driven denizens, but somewhat sadly she finds little to laugh about in how seriously she takes herself. For it is perhaps the most important characteristic of Harriet’s personality that she takes the world so seriously and expects everyone else to as well despite her partner Bruno trying to tell her differently: “Harry’s magic kingdom, where citizens lounged about reading philosophy and science and arguing about perception? It’s a crude world, old girl, I used to tell her.” Because no one seeks to understand the world with as much intellectual vigour and passion as she does, she desires to take revenge upon the people who don’t take her or the world so seriously. The fact that she does this through an artistic prank so elaborate it can only be comprehended after her death is a tragic joke itself. What she really desires is recognition, not revenge. She daydreams that after her death someone will come upon her work and “nodding wisely, my imaginary critic will stare for a long time and then utter, here is something, something good.” The creation of any art is an act of faith that the artist's vision will be recognized and understood and influence the culture its a part of.

Siri Hustvedt is a supremely talented writer and this novel might be her great masterpiece. Feminism and experimental forms of narrative have always had a strong presence in her novels like “The Blindfold” and “The Enchantment of Lily Dahl” while in “What I Loved” she created a novel about the NYC art world and the breakdown of a family. “The Blazing World” seems to synthesize all her primary concerns and turns them into an astonishing story. The truth lies not in any one account in this collection of fragments, but in between the pages and how we construct an idea of Harriet/”Harry.” This is what novels artfully do for us when they are written as brilliantly as this book: give us an incomplete picture of the world to fill in with our own understanding of it. But in the end it's not the artist herself who really matters but the art she leaves behind. As Harriet notes: “I am myself a myth about myself. Who I am has nothing to do with it.” At a certain point personality dissolves and the integrity of the art work's ideas are what determine whether it will stand throughout time. It's my hope that this novel will survive to be read for centuries.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://www.classicfilmfreak.com/2018/07/12/stars-in-my-crown-1950-starring-joel-mccrea-ed-begley-and-dean-stockwell/

Stars in My Crown (1950) starring Joel McCrea, Ed Begley and Dean Stockwell

“Take your choice—either I speak or my pistols do.” —Josiah Gray

Stars in My Crown is a multi-layered film. First of all, while it’s called a Western, it really isn’t one—there are no stagecoach robberies, rampaging Indians, gunfights or a stalwart prairie woman standing by her man. The setting is the South, for one thing.

Stars in My Crown has more the feel of a precursor of TV’s The Waltons, with its emphasis on family, personal relations and homespun philosophies. Yes, clearly intended as a family picture, by its very nature, what might be called the “soft touch,” it borders on being a sentimental tearjerker, a simplistic painting of those long-gone “good old days,” even a pious exercise in religiosity, as the main character is a preacher.

Because the story is narrated (voice of Marshall Thompson) by a young boy about life in a small Southern town, and because one of the subplots touches on racial prejudice, the film, however timidly and unintentionally, anticipates To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). The film’s climax produces a memorable line as a resourceful parson tricks hooded Ku Klux Klaners into freeing an innocent black man.

That the black man’s survival contradicts the less happy fate of Tom Robinson in Mockingbird reveals that much has changed in American life in the brief twelve years between the two films or, rather, that that idealized “soft touch” is no longer valid, not that it ever was.

Jacques Tourneur, who made a special effort to direct Crown because it appealed to him, narrowly avoids the possible sanctimonious preaching and overt sentimentality of the subject matter. His tight control keeps things moving at a fair clip, considering the material is slow-moving by its very nature. Still, the film is dated to a certain extent, and its religious simplicities may not be to everyone’s taste.

Further, the presence of one of the “nice guys” of the movie business, Joel McCrea, predisposes an audience to expect a movie of equal niceness. Something of a cowboy from an early age, McCrea had always wanted to make Westerns, urging studios and directors to put him on a horse. Finally lucky in the ’40s, prior to Stars in My Crown he appeared in six Westerns in a row and many thereafter, challenging his two most popular cowboy-actor contemporaries, Randolph Scott and James Stewart.

When parson Josiah Gray (McCrea) arrives in Walesburg, he proves far from the ordinary country clergyman. “I’m the new preacher in town,” he says, walking up to a bar. “I am to give my first sermon here and now.” The drinkers laugh and Josiah draws two pistols, simply laying them on the bar. “Thanks,” he says to those crouching behind the bar.

Josiah leads the effort to build the town’s first church, falls in love and marries Harriet (Ellen Drew) and the two adopt Josiah’s orphaned nephew, John (Dean Stockwell).

Among events in the life of the town, Josiah defends a hapless citizen (Arthur Hunnicutt) from the local bully (Jack Lambert), a procrastinating churchgoer, Jed Isbell (Alan Hale in his last film), will suffer a Josiah sermon “Just as soon as you get God to plow that bottom land for me!” and a medicine man/magician (Charles Kemper) entertains adults and kids alike.

Most important, Josiah must resolve the two key subplots. First, he resents that a new doctor, Daniel Harris (James Mitchell), is leery of religion. Harris believes Josiah is helping spread the current typhoid epidemic by disregarding his advice about quarantining the citizenry. When the woman (Amanda Blake) he wants to marry falls ill from the disease and the parson saves her through prayer, Harris apologies.

Then there is Josiah’s defense of a poor black sharecropper, Uncle Famous Prill (Juano Hernandez), who won’t sell his mica-rich land to greedy store owner Lon Backett (Ed Begley). When Backett’s white-sheeted KKK men threaten to lynch Prill, Josiah insists on first reading Prill’s will from two sheets of paper he removes from his coat pocket.

What he reads highlights the generosity and kindness of Prill, who, it seems, has left his horse to this person, his rifle to another and so on. Knowing everyone in town, he makes the men under their sheets the beneficiaries. The Klansmen drop their rope, abandon their torches and walk away, ashamed. When the parson tosses aside the pages, John discovers they are blank. “This ain’t a will,” he says. “Yes, it is, son,” Josiah replies. “It’s the will of God.”

In the final scene, everyone gathers at the church, the good, the bad and the ugly, regardless of previous dispositions and affiliations. The congregation sings the title song, “Will There Be Any Stars (in My Crown)?” His land plowed or not, even Jed Isbell is there.

All ends well in this sentiment, idealized world. Fantasy it might be, but a well-done movie that can be enjoyed on its own terms, in the context of its time.

A special touch added to Stars in My Crown, one not always recognized, perhaps even noticed so well does it mirror the screen, is the score by Adolph Deutsch, London-born despite his name. Better known for his comedy scores (Some Like It Hot, 1959, and The Apartment, 1960) and film noirs (They Drive by Night, 1940, and The Maltese Falcon, 1941), the music here is strikingly atypical of his style.

Added to the abundant source music of frequent hymn-singing, the score is a pastiche of homespun Americanareminiscent of Aaron Copland in Our Town (1940) and The Red Pony (1949), or Hugo Friedhofer in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946).

youtube

0 notes