#but getting the native plant habitat established is taking up 100% of the time and energy I have for gardening

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tomatoes my wife grew and basil that I grew (cheese and olive oil we bought at the store)

#I've got to set up a real proper garden instead of just a few plants here and there#but getting the native plant habitat established is taking up 100% of the time and energy I have for gardening#once it's sustainable on its own and relatively weed-free#i can relax and just putter around growing all the veggies i want#my stuff#food#tomatoes

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The World's Marvellously Freaky Carnivorous Plants Are in More Trouble Than We Knew

https://sciencespies.com/nature/the-worlds-marvellously-freaky-carnivorous-plants-are-in-more-trouble-than-we-knew/

The World's Marvellously Freaky Carnivorous Plants Are in More Trouble Than We Knew

It’s hard to fathom that carnivorous plants exist. When Charles Darwin first described how a Venus flytrap worked, calling it “one of the most wonderful [plants] in the world”, some people simply didn’t believe him.

Today, just as we’ve come to appreciate the gruesome nature of these remarkable predators – which can capture and eat flies, rats, salamanders, or the droppings from shrews - they’re now fast disappearing.

The first systematic assessment of carnivorous plants around the world has found a quarter of all known species are at risk of imminent extinction.

“Without urgent action, we stand to lose some of the most ecologically unique, evolutionary interesting, and horticulturally-celebrated species on the planet,” scientists warn.

As of January 2020, researchers have described roughly 860 species of carnivorous plants in total, and while habitats vary, these plants are usually found in wetlands.

Unfortunately, wetlands are also some of the most vulnerable to clearing, logging, and climate change, which puts the future of carnivorous plants at odds with human development and our emissions.

In recent years, pitcher plants and Venus fly traps have received more interest from scientists and the public, but their conservation status in many cases is unknown.

In 2011, a review of carnivorous plant species found habitat loss from agriculture, the collection of wild plants, pollution, and changes to natural systems were the biggest threats. At the time of the research, however, only 600 species had been described; comprehensive data were available for only 48 species.

In the years since, we’ve come to understand carnivorous plants a lot better, and the implications have scientists concerned.

If nothing changes, climate predictions suggest nearly 70 percent of modelled species will be adversely impacted by climate changes. By 2050, several species are expected to lose 100 percent of their potential range.

The first conservation examination since 2011 now shows us well on the way to that reality.

Compiling full or partial data from all known species, researchers found carnivorous plants were most diverse “in some of the most heavily cleared and disturbed areas of the planet,” including Western Australia, Southeast Asia, the Mediterranean, Brazil, and the eastern United States.

In the end, the authors say eight percent of all species (69 species in total) are critically endangered, 6 percent are endangered, 12 percent are vulnerable, and another 3 percent are near threatened.

“Globally speaking, the biggest threats to carnivorous plants are the result of agricultural practices and natural systems modifications, as well as continental scale environmental shifts caused by climate change,” says botanist and ecologist Adam Cross from Curtin University in Australia.

“In Western Australia, which harbours more carnivorous plant species than any other place on Earth, the biggest threat remains the clearing of habitat to meet human needs, resulting hydrological changes, and of course the warming, drying climate trend that affects much of Australia.”

Even if these plants could flee from human development and the effects of climate change, many have nowhere to go. Carnivorous plants are highly specialised, and as such, many species occupy very specific niches.

This extreme restriction means many carnivorous plants are moving towards the edge of extinction in a rapidly changing world.

In the current global analysis, at least 89 species are known from only a single location. Worldwide, almost a quarter of all species are facing three or more existential threats, including global climate change, the clearing of land for agriculture, mining and development, and illegal poaching.

While the plucking and selling of precious carnivorous plants is illegal in most parts of the world, in economically deprived areas it’s hard to stop black markets from popping up. The study authors say these trades remain an “open, tolerated secret”.

“Everyone has mobile phones and the internet for eBay, so there’s a massive trade in the world of rare plants, and it gets bigger and bigger every year,” one naturalist explained to the BBC in 2016.

“People in Europe and North America want specifically different ones, which drives people to go up the mountains, rip them out and bring them back to sell locally and internationally.”

So hungry are carnivorous plant collectors, they will sometimes pay US$1,000 for a single plant. It’s not unusual for requests about the plants to roll in to researchers and photographers within days or even hours of a new photograph reaching the internet. All the authors of the present work have experienced such requests for these rare plants.

There have even been tragic instances when entire populations have been poached within days of their discovery.

While Venus fly traps are popular among collectors, tropical pitcher plants were found to be the most at-risk from poaching, especially in Malaysian Borneo, Indonesia, and the Philippines, which all rank in the top six worldwide for most critically endangered carnivorous plants. Brazil is number one, with 13 species facing critical extinction.

To prevent these plants from disappearing in the near future, scientists say we need to take immediate action.

“Conservation initiatives must be established immediately to prevent these species being lost in the coming years and decades,” argues taxonomist and field botanist Alastair Robinson from Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria in Australia.

“Urgent global action is required to reduce rates of habitat loss and land use change, particularly in already highly-cleared regions that are home to many threatened carnivorous plant species, including habitats in Western Australia, Brazil, southeast Asia and the United States of America.”

The cultivation of rice and oil palm are destroying habitats in Southeast Asia, while logging and development in Australia encroaches on native flora. In fact, Western Australia’s ‘wheatbelt’ has one of the highest rates of habitat clearance on the planet.

In South Africa, extreme drought has left many wetland ecosystems unusually dry, and high intensity and frequent fires in Brazil are wiping out precious wilderness when humans don’t get there first.

One region in Brazil is said to harbour at least 70 species of carnivorous plant. It’s also headed towards ecological collapse thanks to climate change, which is expected to remove up to 82 percent of suitable habitat by 2070.

But all is not lost. Scientists say if we can shift our attitudes and actions as a global community, shutting down the illegal market of carnivorous plants and implementing better development regulations, we could save at least some of these species.

Carnivorous plants are pioneers, the authors say, and when they are exposed to wet soil, they stick to it like a fly in a trap, producing large quantities of seeds to colonise new areas.

“Thus, while suitable habitat remains and natural ecological processes can be maintained, there is hope for [carnivorous plants] to survive (in) the Anthropocene,” the authors conclude.

The study was published in Global Ecology and Conservation.

#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Pittsburgher Undertaking Native Tree, Shrub, and Forest Restoration on a Small Budget

Our guest blogger notes that he has no formal training in gardening or botany which perhaps makes this an even more inspiring story. In the past two years this one individual (with the help of a friend) has planted 1,500 native trees and shrubs as well as numerous native forbs on about 15 acres of his own property and that of willing neighbors. His goal is to attract pollinators such as native songbirds, butterflies, moths, and other insects. His plans include planting at least 500 more native trees and shrubs each upcoming year. We invited him to share his experience, written in his own words, on this ambitious endeavor as part of a blog series inspired by our new exhibition We are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene.

Motivation

My parents taught me bird watching starting from my preteens. I finally saw my first pileated woodpecker (Brookgreen Gardens, South Carolina) at age 14. Canoeing through the Okefenokee swamp in southern Georgia/northern Florida in the spring, we would see brilliant yellow/orange-ish prothonotary warblers flitting some 20 feet away among the knees of towering cypress trees and also the flocks of honking sandhill cranes overhead. One of my daughter’s middle names is Dendroica for the warblers. The other daughter is named after the tallest tree species (if I am pressed, I am not sure if it is for giganteum or sempervirens; my father calls her “little twig”). And my son is named after the last name of the most famous modern biologist. This project for me is about giving back. I am no expert about what I am contributing here. I welcome corrections and comments. The other motivation is that this project is doable with not much money, and anyone could do this. If you do not have the land, find a willing neighbor/friend who does, and start planting natives and removing invasive plants on their property.

Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania

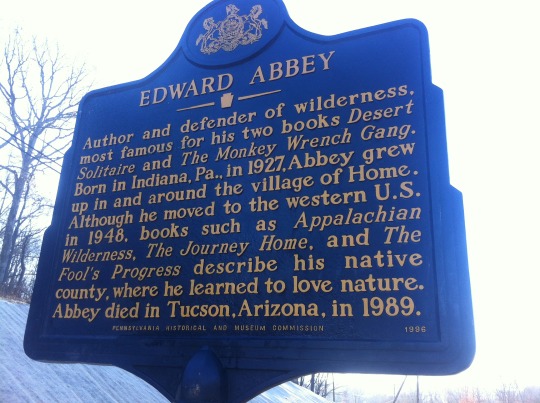

Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania are marvelous ecological areas and the birth areas of noted environmentalists such as Rachel Carson and Edward Abbey. We get plenty of rain, even in the summer, which means we do not have the droughts observed in other parts of the country. Western Pennsylvania is riddled with creeks, which are ample places to plant native trees and shrubs that will never have to be watered as the creek riparian zone will take care of them. We also have clay soil (I know I will swear about the slate rocks when digging holes with a posthole digger by hand), which holds moisture and minerals. Lots of things can grow here. Because of topography, there are many places where houses cannot be built, so there is ample space for native trees, shrubs, and wildflowers.

Pittsburgh National Park

We can think of Pittsburgh as “Pittsburgh National Park,” and the city already supports a huge biomass of bird populations such as the thousands and thousands of crows wintering here each year. If we would just plant lots and lots of flowering trees such as the dogwoods and redbuds and hawthorns and shrubs such as northern bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), we could increase the habitat to attract more beautiful songbirds such as rose-breasted grosbeaks, cedar waxwings and scarlet tanagers to spend more of their time here. I grew up in the Piedmont area of North Carolina, and every spring we would be greeted with the explosions of the dogwoods and redbuds that are endemic in the woods. The same could be done here with our hillsides that are refractory to building houses but not to populating them with dogwoods, redbuds, serviceberries, and hawthorns.

Growing native plants in large clusters

I am no expert on native plants and have consulted with many people as well as just Googled information. Somewhere I had read of a research study in which the authors determined that the planting of 250 wild flowers of one species was necessary to get another butterfly species to appear. A guiding principle is to identify multiple high wildlife value specimens, and then plant lots and lots of each of those species. (I should note that most wildlife management principles state that diversity is better than lots of one species; in my case I am promoting clusters of diversity). If we all wanted to purchase watermelons, but the markets would only keep a few in stock, we would eventually stop making plans to go to a market with the purpose to get a watermelon. And if a bird encounters not one serviceberry tree, but instead a forest of 300 serviceberry trees, we may instead have enticed a flock of these birds. For example, I have observed a flock of cedar waxwings rushing back and forth among a cluster of black cherry trees to eat the fruit. A solitary tree would get less activity. With sufficient establishment of native trees, shrubs, and wildflowers, we may entice birds to nest in the area. The Powdermill Nature Reserve (part of Carnegie Museum of Natural History) Bird Banding project has documented the precipitous decline of songbirds, with some declines as much as 70 percent over the last 50 years. We can repopulate our yards and our woods and our cliffs along the rivers and highways with native species that will restore habitats and help stabilize the populations of the songbirds that are left and perhaps even help grow them.

Early in this project I was fortunate to get a state of Pennsylvania biologist on the phone, and he emphasized that I should concentrate on plant species that use lots of water as these species will generate lots of biomass. With the drainage creek behind by house, I am inspired to plant along its sides every step of its 1000 feet. I am on 2 acres plus. I also have multiple agreeable neighbors on similar or larger acreages, and all these neighbors have acres of woods that they leave alone and have allowed me to remove the invasive trees, shrubs, and grasses and plant the hundreds of native trees, shrubs, and forbs. I am inspired by the biologist at Indiana University who mowed an old overgrown field in Bald Eagle State Park to set back succession to an earlier stage of growth. The mowing was done in wide strips so that as those areas grew back they could mow additional areas. In the following spring he was able to observe several pairs of nesting golden winged warblers, a songbird species that has had a precipice decline in the last 50 years. While I do not expect such spectacular success, one can use the Allegheny County population data from eBird to gauge which songbird species we may be able to attract to nest in the area. In the woods behind my house, I have seen wood thrushes and hooded warblers sporadically each year. Perhaps the growing of a smorgasbord of native trees, shrubs, and forbs will entice them to lengthen their stays.

Bambi

One white tailed deer consumes 200 pounds of leaves and twig matter each month, roughly a ton per year. Typically, when one sees one Bambi, there are another 4 browsing within 50 feet, which is the equivalent of 5 tons of leaf and twig destruction each year. As a gardener, I think of Bambi as rats with long legs. While Bambi has evolved to eat everything, they have yet to develop a taste to eat galvanized steel. For this reason, metal cages are used to protect any plant at risk for Bambi. We have made metal cages from half inch mesh hardware cloth, chicken wire and 16 gauge welded wire fencing. Cages range from 1 foot high to 2 foot high, to 3 foot high to 6 foot high with diameters of 6 inches (18 inch linear fencing made into a cylinder) and 8 inches (24 inch linear fencing made into a cylinder). I am not planning to remove the cages. If I had more funds, the cages would be typically 8 feet tall and 2 to 3 feet in diameter as is done at the Pittsburgh Botanical Gardens as well as at Nine Mile Run in Frick Park.

507 trees and shrubs planted in November 2017

In November 2017, we planted

100 northern bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) seedlings, one to two feet in lengths (www.coldstreamfarm.net)

100 Norway spruce (although it is not a native, Norway spruce is recommended by the Penn State Extension, and I hope to someday attract crossbills which also fly over to Norway) four-year transplants, 12-15 inches in height with 12-15 inch long roots (Mussers Nursery, Indiana County, PA)

100 red-twig dogwood (Cornus sericea; www.coldstreamfarm.net) two to three foot in length seedlings

102 two to three foot long pagoda dogwood stakes (Cornus alternifolia; www.wholesalenurseryco.com/product/pagoda-dogwood-stakes/)

100 eastern white pine four-year transplants, 12-15 inches in height with 12-15 inch long roots from Mussers

5 black willows from Mussers

Soon after planting, 4 inch by 6 inch rectangles of paper were folded over and then stapled in place over the terminal buds of the white pines to protect them from winter browsing by the deer

In spring 2017, I got 300 six-year eastern white pine transplants (Mussers Nursery) that had roots of 2 feet in length. It took me multiple weekends and after work hours that spring to manually posthole the holes for these six-year transplants. Rotting in the basement while waiting to be planted, at least 100 trees did not survive the planting process/the summer.

I learned my lesson. I purchased a gas-powered auger with a 6-inch diameter by 30 inch long bit from Home Depot online. The 6-inch bit is much easier to dig with than the 8-inch bit. My volunteer and I and the gas-powered auger were able to dig over 100 30-inch deep, 6-inch diameter holes in just a couple of hours. This time we got four-year white pine transplants with only 15-inch length roots and planted them the same day we picked them up. The eastern white pines will grow to 100 feet and the spruce trees should grow to 50 to 75 feet. It is like planting an ‘instant forest’. Half inch mesh two-foot hardware cloth cut into two foot sections to prepare cylindrical cages were used to protect the red-twig dogwood seedlings. Each cage was buried about 4 to 6 inches to prevent deer and weather from knocking over the cage. I purchased 4 rolls of 100 feet by 6 feet of 14 gauge welded wire fence (Deacero Steel Field Fence 6 ft. H x 100 ft. L (7745)) from Ace Hardware, and what with shipping cost a total of about $500. We made 50 cages from each roll using tin-snips. 102 cages were used for the planting of the pagoda dogwood cuttings. About 12 inches of these 6 foot cages were submerged into the hole to prevent deer and weather from knocking them over. Native dogwoods other than the common flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) were chosen because of the flowering dogwood’s predilection for Anthracnose, a fungal infection that can make the tree look ugly and potentially die. The pagoda dogwoods were planted in moist soils, and the tall cages should protect them from the deer and allow the dogwood to eventually achieve 20 foot heights.

The costs for planting in November 2017 The 100 spruce, 100 white pine and 5 black willows from Mussers cost $341 plus the cost of gas driving to pick them up. The 100 red-twig dogwood ($146 plus shipping) and the northern bayberry ($172 shipping included) were from Cold Stream Farm. The 102 pagoda dogwood stakes shipped from a Tennessee wholesale nursery were $187. The 200 foot of 2 foot hardware cloth to make the 100 cages for the red-twig dogwoods was about $140. And the pagoda dogwood cages cost about $250.

So the cost of planting 507 trees and shrubs was about $1250 or about $2.50 total per plant which overall is economical. Labor is considered to be voluntary and is not included in these calculations. On the other hand, I am still living in my old unfixed house with my ancient toilets of which one takes 20 seconds to flush and is relegated only to flushing liquids. In 2015 when I got the house, I had repair insurance for the first year though I was unable to convince a plumber that a toilet that took 20 seconds to flush needed to be replaced under that home repair insurance plan. My skimping on fixing my old house allows me the funds to plant a forest that will live for ages.

Invasive plant garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) removal With garlic mustard, I like to pull the first years of this biennial plant whereas others suggest pulling the second year flowers and leaving them to dry and die and decompose. Rosettes are hand pulled and can be left to dry out and die. First year plants including the entire root can be pulled after rains that softened up the grounds. The removed plants are placed in the crooks of tree branches to allow the garlic mustard to dry out and die and decompose.

Example future project: American woodcock project One section of the woods is fairly open with a couple of acres of privet with moist soil and the idea is to replace the privet with alder (300 alder seedlings can be purchased from Mussers Nursery for $150 total) to improve the area to possibly attract woodcock so that the birds have space for their mating dances and space to look for earthworms. We have a heavy duty hand weedy-shrub pulling device (Pullerbear) which can be used to pull invasive shrubs such as privet, multiflora rose, and Japanese barberry out of the ground.

Some sources of information on the web

Landscaping for Birds - A go to website from Cornell Ornithology. I use this website to help decide which classes of trees and shrubs to plant in mass.

Beechwood Farms - Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania. Beechwood Farms has an excellent native plant nursery.

eBird - (dates and populations and locations) of birds in Allegheny County from ebird.

PSU Extension Lawn Alternatives - One of many excellent sites from Penn State Extension.

Garden Planner Dripworks - Where I get my drip irrigation supplies.

Prairie Moon - This is where I purchase about a hundred-dollars of native forbs and shrub seeds each January.

Howard Nursery - Inexpensive trees and shrubs that can be ordered each January through early March from Howard Nursery. Presently have been getting grey dogwood and smooth alder seedlings from them. Recommended to order in January as soon as the website opens as they run out.

Musser Forests - Mussers Tree Nursery. Being only about a 75-minute drive from Pittsburgh.

Cold Stream - Cold Stream Farm wholesale nursery. Relatively inexpensive source for northern bayberry, dogwood shrubs, buttonbush seedlings and more.

Audubon Native Plants - Audubon native plants database. For each plant, there is a listing of which native birds are attracted.

Wildflower - Wildflower database

This blog series depicts Pittsburghers and their commitment to improving the local environment to celebrate our new exhibition, We are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene. Each blog features a new individual and explains the ways in which they are helping in areas of sustainability, conservation, restoration, and climate change. This blog was written in the author’s own words. Any opinions in this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent that of the museum.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Over Labor Day weekend 2017 (the 1st weekend in September) we visited Saguaro National Park and stayed in Tucson, AZ. We’d waited until September to take this trip in hopes of avoiding the worst of the summer heat, but Mother Nature had other ideas, so we were out with the cacti and lizards in the 100˚+ heat after all. Luckily, we are desert dwellers, so we knew how to prepare, and you can usually get a pretty good view of the National Parks without going far from your car.

We drove from Albuquerque to Tucson, since we’d never been that far south in New Mexico. Interstate Highway 25, which runs north/south between and Las Cruces, NM, about 40 miles from the Mexican border, also roughly follows El Camino Real from Santa Fe NM south to El Paso, TX. El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail was created by the Spanish conquistadors and colonists when Juan de Oñate led an expedition north from Mexico City to what is now Santa Fe, NM. The route formalized older footpaths and trade routes of the native peoples.

For the next 300 years, El Camino Real was the only wagon road into New Mexico and the Southwest, bringing thousands of colonists, missionaries and supply caravans from Southern New Spain into newly established Spanish towns that dotted the Rio Grande. The trail facilitated the introduction of horses, cattle, European agriculture and irrigation systems, exotic flora, and many cultural practices that still flourish in the region today. (From El Camino Real at nps.gov )

Someday, we’ll do the El Camino Real route justice and visit historic and interpretive sites in order, but for now, we stop here and there whenever we drive on part of it, and imagine what it was like.

From I-25, we turned west onto I-10, which took us all the way to Tucson. We encountered a border patrol stop not far west of Las Cruces. All cars were required to slow down so that they could see the passengers in the car. They only stopped cars when they didn’t like the look of the people inside. In a state that’s 48% Hispanic, at a spot that’s about 25 miles from the Mexican border. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions about who gets pulled over. 😡

Finally we reached our hotel, after an 8 hour drive (with stops). We stayed at the Lodge on the Desert, a gorgeous old 1930s hacienda that’s been updated into a 100 room boutique hotel. The grounds are landscaped with native desert plants and beautiful flowers, fountains, and a pool. The rooms have features such as Mexican tile, kiva fireplaces, and Spanish-Colonial style furniture. The complementary hot breakfast buffet can be enjoyed inside or outdoors in a courtyard with a fountain and fireplace. My only complaint is that the fixtures in the bathrooms were all built for giants, from the height of the sinks to the shower head. Everything else was lovely, especially the hardworking staff.

Saguaro National Park is made up of two separate districts, about 30 miles apart, on either side of Tucson. The Rincon Mountain District is on the eastern side, and the Tucson Mountain District is on the western side. Both parts of the park have scenic driving loops and visitor centers.

We started on the first day with the Rincon Mountain District. The visitor’s center is small, but it does have a few nice displays, and an orientation video. The park service staff is friendly and helpful. That’s been my experience at every national park, monument, wildlife refuge, etc., so it’s not unusual, but still nice. The driving loop has a large number of interpretive signs that explain what you’re seeing and the ecology and history of the area.

The saguaro are plentiful in this half of the park, but younger than in the western half. There were some major freezes in the 20th century that killed many of the saguaro in this section. I loved it though. It’s fascinating to see and read about the life stages of the saguaro. They tend to sprout under the shade of nurse plants, such as palo verde, making a pretty picture as the saguaro grows as large as its nurse plant. Sometimes a palo verde will be nursing several saguaro.

The east side was full of butterflies, especially huge butterflies. It was also grassy and flowery. We didn’t see much wildlife, other than the butterflies, probably because of the heat, but it was a beautiful and informative drive. Overall, I liked this half better on this trip, partly because this side of the park was much less crowded than the west side.

The west side is where the full grown saguaros live. The visitor’s center is bigger and fancier. There’s a very short interpretive trail just outside with the most common native plants labelled. That was the only trail we walked, because of the heat. There are also water bottle refill stations at both visitor centers.

The driving loop was unpaved (as of the weekend we were there- that could always change). It looked like it might have been bulldozed out recently, so maybe they’re planning to pave it. They weren’t any interpretive signs along the drive. We did see more birds, pollinators, lizards, and small mammals on this loop, despite the road being busier.

Metamaiden was especially taken with the full grown saguaros reaching for the sky. She liked the western district better.

After we left the western half of the national park, we stopped at the nearby Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. This wonderful place is a combination zoo, aquarium, botanical garden, natural history museum and art museum. The museum is dedicated to encouraging “people to live in harmony with the natural world by fostering love, appreciation, and understanding of the Sonoran Desert.”

85% of the museum is outdoors, so be prepared for the weather, but shade is readily available. The museum covers 21 acres with 2 miles of paths through various desert habitats, animal exhibits, art installations, and educational exhibits. It’s eclectic, fascinating, and fun. There were gorgeous flowers and giant butterflies everywhere. Hummingbirds get an aviary all to themselves.

Other highlights include the small aquarium, with its display of cute little garden eels; the otters, which can be viewed from above and underground; and the walk-in aviary with native birds such as a mother quail leading her babies across the paths. We only had time to see about a quarter of the museum. You could probably spend most of a day taking in the exhibits and attending the special live programs.

There are also restaurants and gift shops scattered throughout the grounds, and a bookstore near the entrance. The gift shops feature unique items, including regional arts, crafts and foods, many by Native American artists. The bookstore carries all of the books from the museum’s own ASDM Press, and many others on the human and natural history of the region, including books for children.

I was able to replace a book that I’d loaned out many years ago, Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey, which is just what it sounds like- stories of female pioneers from 1840-1870 taken from primary sources, which I highly recommend. I also bought a second book, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman, the true story of a 13 year old Mormon pioneer girl who was captured by Native Americans in 1851, assimilated into a tribe, traded back into European society at age 19, and ended up the wife of a wealthy Texas banker. Her chin was prominently tattooed while she was still a teenager with the tribes.

There were many other interesting sights to see in and around Tuscon that we couldn’t get to in just a weekend, so I have no doubt we’ll return someday. The largest rose bush in the world in the world, in Tombstone, AZ, won’t elude me forever.

El Camino Real: A Little History and a Few Photos

These were taken at and near a rest stop near Socorro, NM. Notice there are almost no trees for shade, but the ground is covered with spiky, spiny desert scrub that’s 2-4 feet high (about .5-1 meter). Imagine walking through that day after day in the blinding 100 degree heat, sometimes in winds of 20-30 miles and hour, no shade or rain in sight. The Rio Grande River is nearby, at least, but there were also hostile Native American tribes for parts of the journey. I am always in awe of what immigrants of all eras go through on their journeys.

This was the year 1598, years before the British established settlements in any part of North America.

Saguaro National Park- Rincon Mountain District: Cactus Forest Drive

This is the portion of the park that’s on the east side of Tuscon and was much less crowded when we were there. The saguaros are younger in this section than in the western part of the park. I included photos of the sign that explains the history behind the difference. We enjoyed seeing the mighty Saguaros during all of their life stages. It’s a bit like watching Groot grow up.

Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens)

Tucson in the Distance

Engelman’s Prickly Pear Cactus

Looking Back Toward the Visitors Center

Ocotillo and an Important Warning

Tortoise Xing

Chainfruit Cholla Cactus

Fishhook Barrel Cactus

Palo Verde Nursing a Young Saguaro

Where Have All the Sagauros Gone?

Saguaro National Park- Tucson Mountain District

These first three are views from the drive to the park. ☟

Zebra-tailed Lizard (Callisaurus draconoides)

Saguaro skeleton.

This one has leftover flower remnants/seed pods on top of its arms.

Potential nest holes.

Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

Click on any photo to enlarge.

Garden Eels. They are about as thick as a finger and up to 16 inches long.

Red Bird of Paradise, with and without butterflies.

Hummingbirds in the Hummingbird Aviary.

Passionflower and nest on cactus arms.

Dinosaur to Bird Evolution metal sculpture at the entrance to the Walk-In Aviary.

Birds in the aviary: (Clockwise from top left) Gambel’s Quail, Northern Bobwhite (2), Great-tailed Grackle, Steller’s Jay (2)

Otter and beaver, from above and below.

Sleeping Beaver. It was a long, busy day.

Sunset over El Camino Real on the drive back to Albuquerque.

Tucson, AZ and Saguaro National Park Weekend Trip Over Labor Day weekend 2017 (the 1st weekend in September) we visited Saguaro National Park and stayed in Tucson, AZ.

#Arizona#Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum#El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail#Lodge on the Desert#metacrone#Saguaro National Park#Tucson

1 note

·

View note

Text

Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge Offers Respite for Wildlife, People

By Amy Veneziano

Amy, a Pathways Student Trainee with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Pacific Regional Office in Portland, details her recent experience at Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

Not far from Portland, as the roads climb up and away from the Columbia River Gorge, lies another version of the Pacific Northwest. In this Northwest, volcanoes rise from high prairie, cattle graze open range, and hawks survey miles of forest and field for their next snack.

It’s on a fine fall day that Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge in south-central Washington becomes a destination for this explorer.

Take a hard turn north at White Salmon and follow two-lane highways for about 45 minutes to find the refuge, which lies on about 7,000 acres in the Glenwood Valley, hemmed in by eastern Cascade Range slopes and Mount Adams. The refuge was established in 1972 to preserve and restore habitats for a variety of birds, including ducks, geese and swans.

Elk forage in the marsh for most of the year while breeding greater sandhill cranes are spring and summer residents. Oregon spotted frogs are largely inactive during the coldest part of winter, but begin breeding in the chilly wetland waters soon after the ice begins to thaw.

Visitors can check out the Whitcomb-Cole Hewn Log House, one of a handful of pioneer log homes still standing in Klickitat County. The first European homesteaders arrived in the area in the 1870s and built the Whitcomb-Cole cabin in 1891. It bears the marks of generations of human hands, including faded Roosevelt-era newspaper insulation plastered to the walls. The cabin feels at least 15 degrees cooler than the sun-drenched countryside, which must have been a boon in the hot summers. Now located just past the refuge headquarters and on the National Register of Historic Places, it’s easy to imagine a time when the little building was shelter against the harsh Cascade elements.

Pioneers were not the first to discover the potential of this place. The Klickitat people, members of the present-day Yakama Nation, called the prairie “tahk” and they collected camas bulb, hunted, fished, and harvested berries and other plants in the plentiful valley. Archeological evidence shows human activity on the lakeshore from 11,000 years ago.

Outside the cabin, antique farm equipment tells the story of hard work and challenging circumstances in this corner of the world. The valley’s wetlands were partially drained by early settlers, who saw potential for hay and pasture. Those enterprising efforts drove out native species, including the sandhill cranes. One pair of cranes came home in 1979, and today there are about 30 nesting pairs on the refuge. In spite of human habitat modification, the refuge remains home to the healthiest of Washington’s three populations of the federally threatened Oregon spotted frog. After several hours in the refuge, we only get close enough to one person to say hello, when a departing hunter points out a golden eagle sunning itself above the camas prairie.

Much of the refuge is reserved for the creatures native to the foothills, with some of it open to hikers, wildlife watchers, hunters and anglers. The Willard Springs Trail is a gentle loop with a wildlife viewing platform and view of Mount Adams, the aforementioned springs trickling into the prairie at the far end of the loop. Sandhill crane colts are visible from the platform in spring, but in fall the field is empty to the untrained eye. The aspen abutting the prairie and Cold Springs Ditch on the east side of the loop give way to coniferous pine and fir on the west side, with Douglas’s squirrels chattering their indignation at the human interruption. Though an easy walk, the path is not stroller- or wheelchair-friendly.

Conboy Lake doesn’t just conserve the land for flora and its inhabiting fauna — including seven amphibian, 10 reptile, 40 mammal, and 165 bird species; it’s also a connection to the rural character of this part of Washington. Lolling cows in open range are common in the area, family apple orchards pocket the valleys, and neighbors hunt the refuge for waterfowl to land on their dinner table. The small towns of Trout Lake and Glenwood are nearby, but beyond those the nearest population of any size is Hood River, Oregon – 33 miles by car and home to almost 8,000 people. Portland and Vancouver are about 90 miles west, and Yakima lies 100 miles northeast.

Public lands, open sky, and a resonant quiet make Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge an ideal escape, whether for a sandhill crane or a city-weary weekend warrior. Find out more, including the hours and driving directions, at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Conboy_Lake/.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

New Post has been published on https://toldnews.com/world/united-states-of-america/can-humans-help-trees-outrun-climate-change/

Can Humans Help Trees Outrun Climate Change?

By Moises Velasquez-Manoff

Illustrations by Andrew Khosravani

April 25, 2019

SCITUATE, R. I. — Foresters began noticing the patches of dying pines and denuded oaks, and grew concerned. Warmer winters and drier summers had sent invasive insects and diseases marching northward, killing the trees.

If the dieback continued, some woodlands could become shrub land.

Most trees can migrate only as fast as their seeds disperse — and if current warming trends hold, the climate this century will change 10 times faster than many tree species can move, according to one estimate. Rhode Island is already seeing more heat and drought, shifting precipitation and the intensification of plagues such as the red pine scale, a nearly invisible insect carried by wind that can kill a tree in just a few years.

The dark synergy of extreme weather and emboldened pests could imperil vast stretches of woodland.

So foresters in Rhode Island and elsewhere have launched ambitious experiments to test how people can help forests adapt, something that might take decades to occur naturally. One controversial idea, known as assisted migration, involves deliberately moving trees northward. But trees can live centuries, and environments are changing so fast in some places that species planted today may be ill-suited to conditions in 50 years, let alone 100. No one knows the best way to make forests more resilient to climatic upheaval.

These great uncertainties can prompt “analysis paralysis,” said Maria Janowiak, deputy director of the Forest Service’s Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science, or N.I.A.C.S. But, she added, “We can’t keep waiting until we know everything.”

In Rhode Island, the state’s largest water utility is experimenting with importing trees from hundreds of miles to the south to maintain forests that help purify water for 600,000 people. In Minnesota, a lumber businessman is trying to diversify the forest on his land with a “300-year plan” he hopes will benefit his grandchildren. And in five places around the country, the United States Forest Service is running a major experiment to answer a basic question: What’s the best way to actually help forests at risk?

Some worry about the unintended consequences of shuffling plants and animals around and that the approach will become widely adopted. “Moving species is the equivalent of ecological gambling,” said Anthony Ricciardi, a professor of invasion ecology and environmental science at McGill University in Montreal. “You’re spinning the roulette wheel.”

Want climate news in your inbox? Sign up for Climate Fwd:, our email newsletter.

It is also complicated. On Lake Michigan, one adaptation planner trying to help the Karner blue butterfly survive is considering creating an oak savanna well to the north, and moving the butterflies there. But the ideal place for the relocation already hosts another type of unique forest — one that he is trying to save to help a tiny yellow-bellied songbird that is also threatened by warming.

In other words, he may find himself both fighting climate change and embracing it, on the same piece of land.

Rhode Island: Swapping In Persimmon

One humid day last fall, Christopher Riely hiked to an 8-foot-tall wire fence in the forest. “It’s amazing how high deer can jump,” he said, unlocking the towering gate.

Mr. Riely helps manage 20 square miles of woodland for Rhode Island’s largest water utility, Providence Water. Inside the five-acre enclosure, among the native oaks and pines, he had planted southern trees including persimmon and shortleaf pine — species better adapted to hotter, drier conditions. And they were thriving.

Mr. Riely is particularly delighted by the Virginia pine, brought in from a nursery nearly 400 miles away in Maryland. “For New England, this is quite incredible growth,” he said, pointing to a young tree now taller than he is. It suggests that climate has already changed enough in Southern New England for some mid-Atlantic species to survive.

Bringing in southern trees may be one solution. But it won’t help, he has discovered, without first dealing with the deer. They ate many of the young trees he planted outside the fence, and are a major reason the hardwood forest has difficulty regenerating.

As a cautionary tale, Mr. Riely looks to the forest collapse that struck near Denver some years back. Conditions in the Rockies differ substantially from those in Rhode Island; still, he calls it “a water supplier’s nightmare.”

In the 1990s, dry spells, insects and disease began killing trees there. In 1996 and 2002, ferocious fires tore through. Then the rains came. Flash floods carried dark, ash-filled silt and debris into Denver’s reservoirs, clogging them.

So in 2010, Denver Water began replanting the mountainsides, making the forest more drought-resistant by spacing trees farther apart and reducing competition for water. Opening the forest canopy allowed other kinds of plants, which also prevent erosion, to grow as well.

Failing to plan for the changing environment was a costly lesson, said Christina Burri, Denver Water’s watershed scientist. A big part of what she does today, she added, is “convincing people about the benefits of being proactive.” Planning ahead, she said, is much cheaper than reacting to catastrophes.

Minnesota: The ‘300-Year Plan’

For someone who makes his living selling wood, John Rajala leaves a lot of trees on the land. It’s part of what he calls his “300-year plan” to deal with climate change.

His family business in northern Minnesota, called Rajala Companies, owns 22,000 acres of northern pine and hardwood forest. He harvests the wood and mills it into flooring, siding and roof beams.

One cool day last fall, he proudly showed me around his land near the headwaters of the Mississippi River, a gently rolling forest of straight eastern white pines, quaking aspen and the occasional flaming red maple. The old “legacy trees,” as he calls them, will reseed the forests with good genetic stock.

“That’s a thousand-dollar tree, and we’ll never cut it down,” he said, pointing to a majestic, century-old white pine.

Mr. Rajala’s planning for climate change is unusual in his profession. “The more careful thought about climate change just isn’t being done” by many industrial-scale companies that manage forestland, said Chris Swanston, who heads the Forest Service’s N.I.A.C.S.

One reason, he and others say, is that so much timberland is owned by real-estate investment trusts and other financial vehicles, which are geared toward short term profits.

Industrial foresters might plant one or just a few tree types, to make harvesting and management easier. Mr. Rajala has embraced a different approach. “I want to accelerate as fast as I can the diversification of species,” he said. Even if some species do badly in a warmer tomorrow, he thinks, others will flourish.

Unlike Mr. Riely in Rhode Island, Mr. Rajala is not willing to introduce nonnative species — yet. But he’s sculpting the forest to make it more resilient.

Birch, a cool-weather tree valued by cabinet makers, isn’t doing as well as it used to. So Mr. Rajala keeps the tree only on north-facing slopes, where it’s naturally cooler.

On south-facing slopes, he is selecting for red oak and maple, two native species projected to do better in a warmer future.

His strategy has required shrewd marketing. Because he leaves many of his best trees standing to reseed the next generation, the wood going to his mills is often imperfect, particularly if it’s aspen or birch, which have started showing signs of climate stress.

Mr. Rajala’s new sales pitch? Imperfection adds character.

Chippewa National Forest: Grand Experiment

One of the most ambitious studies of how to help forests is happening near Mr. Rajala’s land. Launched four years ago by the Forest Service, the project set out to scientifically test the best approach to helping woodlands adapt. With five sites around the country, the study is perhaps the largest of its kind in the world.

In Minnesota, the Forest Service planted 274,000 seedlings over an area roughly 60 percent the size of Central Park. It is testing four approaches: passively letting nature take its course; thinning and managing mostly native trees along traditional lines; growing a mix of native species but with some coming from 80 to 100 miles to the south; and the most radical one, bringing in nonnative trees from warmer, drier areas in nearby states.

The nonnative trees include ponderosa pine from South Dakota and Nebraska, and bitternut hickory from southern Minnesota and Illinois. So far, the pine is doing well.

Conditions may not be optimal for the trees now, but “the idea is to get them established now for 30 years in the future,” said Brian Palik, a forest ecologist with the Forest Service’s Northern Research Station, who oversees the Minnesota site.

Lake Michigan: Where to Put an Oak Savanna?

On Lake Michigan, climate change threatens both the Kirtland’s warbler and the Karner blue butterfly. And saving one may complicate preservation of the other.

As recently as 2009, the Indiana Dunes National Park hosted one of the country’s healthiest populations of the endangered Karner blue. By 2015, they had mostly disappeared.

“I’m pretty sure they’re not in Indiana anymore,” said Christopher Hoving, an adaptation specialist with Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources.

Karner blues inhabit only pine barrens and oak savannas, rare habitats of wildflowers and grasses interspersed with trees, that occur in poor, sandy soil deposited by ice age glaciers. Mr. Hoving and his colleagues think the only way to save the southern populations of Karner blues may be to create a new oak savanna at the northern edge of Michigan’s lower peninsula, where similar soil occurs.

But there, Mr. Hoving’s project to save the Karner blue may collide with his efforts to save the Kirtland’s warbler. In the same place he’s thinking of creating an oak savanna, he is also trying to prevent a dense jack pine forest (which the warbler needs) from retreating north.

The region probably has enough room to host both ecosystem types, he said, at least for a while. But “it’s a high-risk proposition,” he said.

His two projects embody the odd mixture of sunny pragmatism and clammy anxiety inherent in the very idea of humans moving life-forms around to save them from problems caused by humans.

In academia there is no consensus on assisted migration. Dr. Ricciardi, the McGill University professor of invasion ecology, calls it a “techno-fix” that fails to address the “root cause of endangerment or ecosystem erosion” — in this case, climate change.

Not everyone agrees with Dr. Ricciardi. Jason McLachlan, an ecologist at the University of Notre Dame, once spurned the idea of assisted migration, but his views have evolved as the current predicament has sunk in. He concedes Dr. Ricciardi’s point about the unknowable risks of moving things around, but counters that doing nothing is also “extremely risky.”

His broader critique is that classic conservation science risks failure today because it assumes the world is static — and if the world ever was static, it clearly isn’t anymore. Consider the Endangered Species Act, he said, a bedrock of modern conservation. It aims to return species to their original habitat.

But what if they’re now ill-suited to those areas?

To deal with the coming upheavals, our very concept of nature and the meaning of conservation needs to become more fluid, Mr. McLachlan said. “We don’t have a philosophy of conservation that’s consistent with the changes that are afoot.”

For more news on climate and the environment, follow @NYTClimate on Twitter.

#FridayMorning#hausa news live#the usa news#us news math rankings#us news ranking cars#usa news in chinese#usa news paper#usa news stream#usa news video live#wusa news

0 notes

Text

Tourist Office Toronto

WHAT TO DO

Sundown over Toronto, CanadaWith a populace of 2,930,000, Toronto is the largest city in Canada. It is additionally known as the "Queen City". Dynamic, cosmopolitan, exciting as well as international, Toronto is made up of 6 formerly separate municipalities, each with its own distinctive background and identity.

It is advertised as one of the most multicultural cities worldwide, with over 200 distinctive ethnic beginnings represented amongst its populace.

Although the city is difficult to go to in a motorhome, you can most definitely remain a few days prior to pick up a Motor Home service in Toronto. Ideal of both globes!

THE SHORES OF LAKE ONTARIO

CN TOWER

Toronto CN TowerThis 553-metre-high concrete communications tower, developed by Canadian National train company in 1976, defines the Toronto sky line. The top levels are reached by among 6 high-speed glass-fronted lifts. Delight in a breath-taking view as you race upwards at 22 kilometres per hour to a height of 345 metres, virtually the elevation of the Realm State Structure!

The LookOut deck supplies breathtaking views of the city as well as the bordering area. On the level listed below, experience the clear Glass Floor, with a sight 342 metres right down! Created for you to have a good time on it, you can stroll or creep across it, rest on it and even jump on it. Will you attempt? Or appreciate the view from the globe's highest possible revolving restaurant, 360 Restaurant. Bookings are required.

Open up daily from 9 a.m. to 10:30 p.m.

RIPLEY'S FISH TANK OF CANADA

Located at the foot of the CN Tower, this massive 135,000 square foot fish tank takes you on a true undersea journey, via different habitats from worldwide, where fascinating sea creatures reside in greater than 5 million litres of water! You will have the opportunity to check out various galleries consisting of Canadian Waters, with a section on the fascinating biodiversity of the Great Lakes, the Rainbow Coral Reef of the Indo-Pacific Sea, Dangerous Shallows, the Exploration Centre as well as its interactive exhibitions, Ray Bay, Planet Jellies, as well as the "Curious Creatures" display, which will certainly present you to the life of reporter, adventurer, explorer, draftsman as well as fantastic enthusiast Robert Ripley (1890-1949) in addition to lots of curious creatures from the four corners of the world.

Open up daily from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m., yet closes previously once in a while for personal occasions.

HARBOURFRONT FACILITY

Toronto Island MarinaToronto's highest possible concentration of cultural and leisure offerings is located at the Harbourfront Centre. This 4-hectare waterside park supplies a variety of occasions and also tasks year-round on its quays and also in its converted terminal structures.

The Harbourfront Centre homes marinas, cafés, dining establishments, craft and also antique stores, workshops, sophisticated property facilities, gardens as well as eco-friendly rooms.

THE TORONTO ISLANDS

Downtown Toronto from the islandsThe Toronto Islands, with their majestic old trees, smooth yards, marinas as well as sandy shores, supply remarkable views of midtown Toronto along some 6 kilometres of shoreline.

Centre Island has a theme park, a beach, as well as many cafés and also dining establishments. Discover the more rustic beauties of close-by Algonquin Island and also Ward Islands along kilometres of walking and also biking routes.

ONTARIO LOCATION

Bird's-eye view of Ontario PlaceThis ultimate household destination includes a waterpark, pedal boats, bumper boats, flume trips, mini-golf, helicopter trips, a kids's village and numerous restaurants. The website extends across three man-made islands, full with shallows as well as marinas, along the Lake Ontario beachfront.

The Cinesphere, a 600-seat IMAX movie theatre, has a bent display that is six stories-high. The cinema reveals 3D films throughout the year.

DOWNTOWN

TORONTO RULE FACILITY

The dark glass towers of the Toronto Dominance Center were the first major structures to be integrated in Toronto's monetary area, among the largest business areas in North America. Some 21,000 people operate in the complicated, which likewise acts as headquarters as well as company offices for a variety of significant Canadian services.

HOCKEY HALL OF POPULARITY

The Hockey Hall of Fame, TorontoThe Hockey Hall of Popularity is the largest hockey gallery worldwide. Along with learning all about hockey as well as discovering the world's biggest collection of hockey memorabilia, you will certainly have the chance to participate in a variety of on-site tasks. The original Stanley Mug, dating from 1886, gets on display in the Great Hall, housed within the historical previous head workplace of the Bank of Montreal.

Open up in high period Monday-Saturday from 9:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. as well as Sundays from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. In low period, Monday-Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturdays from 9:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., as well as Sundays from 10:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT

Toronto City HallToronto Town Hall was the sign of Toronto up until the construction of the renowned CN Tower, as well as stays one of Toronto's best understood sites. Constructed in 1965, its curved twin towers surrounding a white disk-like council chamber are a suitable icon of a contemporary and vibrant city.

100 Queen Street West, Toronto

EATON CENTER

Toronto Eaton CentreThe Toronto Eaton Centre is Canada's supreme shopping location, with over 230 stores, restaurants as well as services. It is the largest shopping centre in Toronto.

Numerous travelers from all over the world see the Centre each year to admire its style and also its urbane environment.

Open up Monday-Saturday from 9:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. and Sundays from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m.

ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO

Invite to one of the largest art galleries in North America! Its 45,000 square metres of area house a sublime collection of almost 95,000 works, consisting of Native and also Canadian art, European, modern-day, contemporary and also African art, digital photography, prints and also drawings, a 380,000-volume collection & archives collection, as well as the Thomson Collection, a present of 2,000 European as well as Canadian jobs from Ken Thomson's personal collection.

Open Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10:30 to 5 p.m., Wednesdays as well as Fridays from 10:30 a.m. to 9 p.m., and Saturday-Sunday from 10:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

BATA FOOTWEAR MUSEUM

If you enjoy footwear, this fascinating gallery is a must! The displays mirror over 4,500 years of history via greater than 1,000 footwear and also shoe-related items chosen from a collection of over 13,000 artefacts. Emphasizes include a pair of 16th century Italian platform shoes, a collection of footwear from a few of the earliest worlds in the world, an extensive collection of Indigenous North American as well as circumpolar shoes, an array of star shoes from the similarity Elton John, Elvis Presley, John Lennon, and far more.

Open Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays as well as Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Thursdays from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m., and also Sundays from twelve noon to 5 p.m.

ROYAL ONTARIO GALLERY

This remarkable museum, generally called the ROM (Royal Ontario Gallery), is the biggest gallery in Canada. It is home to a first-rate collection of 13 million artworks, cultural objects and also natural history specimens displayed in 40 gallery and event spaces. There's also a location reserved for kids. It's best to grab a map when you arrive to intend your go to, as the H-shaped gallery has no less than 5 floors!

Open daily from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. between July 1 and the initial Monday in September. Closed on Mondays in reduced period.

CASA LOMA

Constructed in 1914, Casa Loma was the delicious residence of financier as well as former soldier Sir Henry Pellatt. Every year, over 350,000 site visitors trip Casa Loma and the spectacular estate gardens. The stunning 98-room "castle" features a terrific hall, a sunroom, a library, secret passages and much more. A tunnel attaching the manor to the stables houses a picture display on the "Dark Side of Toronto", while the stables display a collection of classic cars from the very early 1900s. The on-site BlueBlood Steakhouse serves dry-aged steak as well as delicious fish and shellfish.

Open daily from 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

NEARBY

ONTARIO SCIENCE CENTRE

Because 1969, this temple of science has actually been inviting site visitors of every ages to explore the greater than 500 interactive activities in its 8 exhibition halls. It provides a wide array of science workshops, presentations and shows, in addition to an IMAX cinema, a dining establishment and cafés.

Open up Monday-Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m., and also Sundays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

TORONTO ZOO

The Toronto Zoo's mission is "attaching people, animals and also conservation scientific research to fight termination": with more than 5,000 animals belonging to 450 species from worldwide, you might claim they're doing their component. The zoo is separated right into seven different geographic regions, each showcasing pets and plants from that area of the world: Africa, the Americas, Australasia, the Canadian Domain Name, Eurasia Wilds, Indo-Malaya, as well as Tundra Trek. There are likewise opportunities to fulfill a few of the animals as well as their caretakers, a Children Zoo and also Sprinkle Island theme park, a zipline ... Something to please every person!

Open daily from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. (until 7 p.m. in summer season).

OPTIONAL ACTIVITIES

Excursion of the CN Tower

Eat in the sky in Toronto

Led tour of Toronto

WHERE TO EAT

SEVEN LIVES ($).

This small restaurant in Kensington Market is tremendously prominent for its renowned and also scrumptious tacos. The taco menu features a variety of options such as meat, fish, shrimp, octopus, as well as for vegetarians, mushrooms as well as cactus, all accompanied by homemade salsas. Their trademark recipe is their Gobernador taco with house-smoked tuna, barbequed shrimp and also cheese. They likewise offer a tasty seafood ceviche served with tostadas as well as a dish of the day. As there is often a schedule and also there is no real seating location, you can enjoy your meal while strolling with the marketplace.

Open up Wednesday-Sunday from noon to 8 p.m.

AMSTERDAM BREWHOUSE ($$).

The Amsterdam Brewing Co. has been making its own beers considering that 1986 and also you can taste them at their dining establishment, the Amsterdam Brewhouse. The cook interacts with their makers to produce recipes that are prepared not only utilizing their beers, but additionally with components that are utilized in the developing process. The unpretentious pub-style menu attributes wood fired pizzas, burgers and also sandwiches in addition to meat, pasta, fish and tofu recipes. In the summertime, you can sit on their massive balcony overlooking the huge Lake Ontario and also appreciate your beer.

Open up daily from 11:30 a.m.

MOMOFUKU NOODLE BAR ($$-$$$).

When New york city celebrity chef David Chang determined to transplant his well-known noodle bar to Toronto, it was an instant success. Momofuko Toronto is a 6,600 square foot 3-storey restaurant complex including 3 restaurants (Momofuku on the very beginning, Daisho and also Shoto on the third flooring) and a cocktail bar. Momofuku is a cafeteria-style restaurant with lengthy communal tables. Must-try food selection things include the hen buns, ginger scallion noodles, Hong Kong egg, rice cakes, mackerel, chicken wings as well as rice dessert.

Open daily for lunch from 11:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. Open evenings Tuesday-Saturday from 5 p.m. to 11 p.m. and also Sunday-Monday from 5 p.m. to 10:30 p.m

. THE GABARDINE ($$-$$$).

The cook and his team cook up a storm of timeless dishes motivated by great old made home cooking. The menu uses a series of appetizers such as cozy olives, chicken liver paté, beer and cheese rarebit and also devilled eggs, salads, 5 types of sandwiches and a choice of main dishes consisting of the well-known macaroni and cheese, risotto, fish of the day, chicken casserole, and soft corn tortillas with Atlantic cod. The Cape is committed to using local, lasting, natural components whenever feasible.

Open up Monday-Friday from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Offering breakfast from 8-10 a.m., lunch from 11:30 -3 p.m. and supper from 5-10 p.m. Open up some Saturdays.

RICHMOND TERMINAL ($$-$$$).

This dynamic midtown restaurant is constantly dedicated to providing scrumptious food with a concentrate on great ingredients as well as cozy hospitality. Cook Carl Heinrich devises meals such as smoked cheese perogies with cauliflower cream, Brussels sprouts and rösti; Terminal hamburger with homemade rolls, garnish as well as rosemary french fries; two-way duck with wonderful as well as sour rutabaga as well as roasted cabbage; braised bunny fettuccine with oyster mushrooms and butternut squash; and also crispy tofu stir-fry with spicy soy vinaigrette, seasoned mushrooms as well as hazelnuts. Mouth-watering!

Open daily from 11 a.m. to 10:30 p.m.

360 THE DINING ESTABLISHMENT AT THE CN TOWER ($$$-$$$$).

360 deals delicious market-fresh Canadian cuisine at an elevation of 350 metres! Appreciate a glass of Canadian white wine as you admire a special 360-degree panoramic view of the city. Open up for lunch as well as supper; reservation is advised. Access to the Search and GlassFloor is free with the acquisition of a prix fixe!

Open daily for lunch from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. as well as for supper from 4:30 p.m. to 10 p.m.

CANOE ($$$$).

Found on the 54th flooring of the TD Financial Institution Tower in Toronto's economic district, Canoe provides stunning sights of the city as well as creative local Canadian food created by the cook. The food selection, from delicious foie gras to grilled-to-perfection meats to magnificent fish and shellfish, is merely prepared as well as place on. The preferences are nuanced, shocking as well as textured. And, thanks to a presentation that is gallery-worthy, constantly charming to admire. The solution is unpretentious as well as expert.

Open Monday-Friday for lunch from 11:45 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. and also for supper from 5 p.m. to 10:30 p.m.

WHERE TO SLEEP?

Germain Maple Leaf Square.

Hilton Toronto.

Bond Place Resort.

Strathcona Resort Downtown Toronto.

Chelsea Hotel Toronto.

CELEBRATIONS SCHEDULE.

TORONTO JAZZ CELEBRATION.

Days: June 18 to 27, 2021.

Created in 1987, the Toronto Jazz Celebration offers an impressive schedule of over 1,500 musicians, including some of the greatest jazz celebs in the world. Today more than 500,000 jazz fans come together every year over the 10 days of festivities to go to one or more of the 350 performances held all throughout the city.

SATISFACTION TORONTO.

Days: end of June 2021.

Toronto's Satisfaction Week is one of the premier arts and also cultural celebrations in Canada. It is not unusual that the event is an unqualified success, every year: presence of over a million individuals, street celebration, live home entertainment, street fair, outfits, Pride Ceremony, and also a lot more ...

TORONTO CARIBBEAN CARNIVAL.

Days: late July/ early August 2021.

Canada's biggest city is house to this abundant celebration of Caribbean songs as well as culture, including steel bands, a King and also Queen competition, shows as well as music boat cruise ships. The festivities culminate with the magnificent carnival ceremony. The biggest Caribbean event in North America.

The post “ Tourist Office Toronto ‘ was first seen on Authentik

Naturopath Toronto - Dr. Amauri Caversan, ND

0 notes

Text

Project Proposal

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1iniOtp3VJwLOMsKZylzvlw92aZN2YOudq_SHTLImW2g/edit?usp=sharing

Our team is proposing a research trip to Jocotoco reserves in Ecuador to record bird species unique to the area. Birds such as the Andean hummingbirds and the neotropical birds endemic to the cloud forest. We will be recording and archiving bird sounds in order to effectively understand and appreciate the soundscape these endangered species inhabit.

Background of site and ecoacoustic significance

The Jocotoco reserves are run by an Ecuadorian NGO established to conserve the environment of the region as well as endangered birds unique to the region. This land is purchased by the NGO and then managed as ecological reserves which are also a refuge for ecoacustic researchers to explore and archive the soundscape. The Foundation has so far established 11 reserves, spanning more than 40,000 acres of land. The reserves protect the wildlife, facilitating the safety of the environment which wasn’t also once a promise. With nearly 800 species of birds, the Jocotoco reserves are among some of the most biodiverse regions in the world. Unfortunately, 50 of these species are considered to be globally threatened as their population has suffered in part to historical disputes between neighboring countries. More and 100 of these species are specific to the region, emphasizing the importance of their preservation. While the main focus of the Foundation is preserving the endangered birds, all habitats of the region are protected under these reserves. Including fauna and flora unique to the amazon region.

The amazon rainforest of Ecuador is one of the largest tropical forests on earth. Its proximity to the Andes mountains results in many different altitudinal tiers which has facilitated the development of many different bird species as well as other diverse plants and wildlife. Also home to indenginous tribes have maintained their way of life for centuries. The reservations and national parks play a big role in protecting this landscape as it is also home to large deposits of much sought after oil reserves. Their presence restricts the oils accessibility and ensures the preservation of the landscape (www.laselvajunglelodge.com).

Material and methods for sampling and data archiving

We plan to use Zoom VR recorders to capture the sound of the landscape. The three of us will each carry two of these, one as a backup. And will all be recording in each site we visit. The Zoom VR is a 4 channel recorder. To play back the audio, we will use the Sennheiser HD 280 Pro headphones. Each of us will carry two, one as a backup. We will be recording on 64 gigabyte Sony TOUGH-G series SDXC UHS-II cards capable of withstanding 72 hours of full water submersion at a depth of 15 feet. As well as being robust enough to take up to 180 newtons of direct force and fully dust resistant. Our audio files will be stored on portable SSD drives, however and to ensure the security of the files. We will be using a Samsung 500GB 860 EVO SATA 2.5" SSD for this. Each of us will have two 64 UHS-II cards with us and two SSD drives. To transfer the audio files from the UHS-II cards to the SSDs we will use the 14” Dell Latitude 5420 Rugged. Coming with an 8th Generation Intel Core i5-8350U Processor 500GB of SATA hard drive space and 8GB of RAM. Also featuring swappable dual batteries as to extend its work capabilities. Designed to be used in hazardous environments, the computer is drop tested as high as 3 feet. We will also use the computer as a portable workstation to process and edit the audio file on the move. This will save us time after the field recordings when we would typically do this work. The Zoom VR recorders come with software to utilize its multi-channel functionality and 3D sound experience. We will also be using Adobe Audition to edit the audio files. This will be downloaded onto the computer for practical use.

Other than recorders, we will be bringing a Sony Alpha A7 III camera to also document our experience in ways beyond audio files. This will aid in communicating the results of our trip as another describable media to be presented. This is a remote region of much biodiversity. Having a visual reference for the area as well as the wildlife to be encountered adds another dimension of reference which would have otherwise been overlooked. Our source for the camera includes a camera bag, spare batteries, a battery charger, a memory card, and a lens cleaning kit. The lens we will be using is a Sony FE 24-70mm. Favored for its versatility, the lens has a f/2.8 maximum aperture to capture wide shots as well as zooms for more distant encounters. The enclosure of the lens is dust and moisture resistant to ensure its survival in the cloud forests where it is known to be rainy and unpredictable. Also coming with an easily detachable visor guard to ensure the clarity of shots even in sunny conditions.

Given the high precipitation of the region, our team will be using a set of GORE-TEX branded shells and pants to stay dry. Both patagonia branded, the set will enable us to continue working regardless of the weather given their ability to repel water and debris. To protect our gear, we will be using REI 32 liter waterproof backpacks, capable of keeping our essentials dry in any condition other than full submersion. We plan to purchase our boots at the markets in Quito. This is where many ecoacustic researchers get their boots from and will reduce the load of luggage for our international flights. The criteria for these boots are to be water resistant and go beyond our ankle.

Region of field work

The Jocotoco reserve is in the Amazon region of Ecuador. To the East, the Amazon continues into Peru, and to the East is the Andes mountain range. Thanks to the network created by other ecoacustic researchers, tour groups, reservations, and wildlife research facilities, the reserves often have lodging and food for visitors and researchers to use. There is a network of roads connecting the reserves that we will travel on. Our tour guide will drive us to our destinations. Some areas are not accessible due to the possibility of land mines. These areas will be avoided with the help of our guide and the reserves.

Health & safety concerns

Concerns for the trip mainly derive from the tropical nature of the region. With many hills, some mountains from the Andes, and the persistent precipitation which is a consequence of the air moisture colliding with the Andes mountain range which causes a collision and downfall of the water. As to not face the brunt of the environment, we plan to travel in the Winter months which experience less precipitation than the Summer and Spring months. To protect our equipment, we have carefully selected gear capable of withstanding moisture and even some instances of full submersion. This is insurance that our audio files and equipment will be protected. However, we still plan to carry backups of our more critical gear. This is why we are taking 6 total Zoom VR recorders as well as 6 pairs of headphones for playback listening. Archiving our data is another way to protect the files as recorders can be broken or even robbed from us. Having two SSD hard drives as well as a rugged computer with 500GB of SSD hard storage will give us multiple outlets to save our files on. The audio recorded in the excursion is critical to the trip, keeping them on multiple devices dramatically decreases the likelihood of it being compromised. All of our equipment will also be stored in ALPS Mountaineering Torrent dry bags. These are made of waterproofing material and will add extra protection to gear that is not moisture resistant such as the camera, SSD drives, headphones, and Zoom recorders. Spare batteries for the recorders, camera, and laptop will also be brought to ensure the functionality of the equipment even in such a remote region.

To protect ourselves from the weather, we will use patagonia GORE-TEX shell jackets and pants. This is critical given the strenuous nature of the trip. Keeping our bodies protected will ensure our resilience to continue recording and traveling throughout the trip. As mentioned, we will purchase water resistant boots from the markets in Quito, providing our own hiking soles to save our feet from the unpredictable landscape.

We also plan to consult a health care professional about the suggested vaccines for the region. Mosquito borne diseases such as typhoid, hepatitis A + B, yellow fever are much more likely to be contracted. The vaccinations will be had before our departure to Ecuador.

The Joco Tours group will be guiding our excursion. They have extensive knowledge of the region, its history, and the travel destinations for recording and lodging. They are also official partners of the Jocotoco group - a foundation devoted to the preservation of the landscape and Jocotoco reserve. Given their knowledge, the chances of getting lost on the back country roads are less likely than if we were to travel alone. Spanish is the primary language of Ecuador. While no one on our team speaks spanish, we will still be able to communicate with locals via the translator accompanying us on the tour. All travel, except international, will be coordinated by the tour group. Their connection network spans this area, leaving them to be the most qualified people to lead the travel aspect of the trip. This ensures our safety as the Ecuadorian Puruvian border has a dark history of conflict. Today, there are over 100,000 landmines in some fields of the region. With their expertise, avoiding these areas will be much more likely given their native experience and historical understanding of the region.

Timeline of the project

We plan to go in early December of 2020 to avoid the rainy season. Giving us another 9 months from the submission of this proposal from when we would leave. With this time, we will continue to do preliminary research of the region and specific reserves that we will be visiting. Also during this time, all of our travel plans will be double checked with one of the Jocotoco Tours representatives to ensure we have properly communicated the purpose of the trip as well as itinerary specifics. After this, we will continue to develop our methods of recording and gather all of the supplies needed for the trip. All devices, gear, and clothing will be checked for quality assurance. This gives us time to rectify a faulty item before we leave. Emphasizing the state of the recording and data archiving equipment as these are the most important items to bring for the excursion. All SSD and UHS-II cards will be tested. The tour will span 11 days and span 5 national reserves and wildlife parks.

To archive our data files, we will transfer the audio from the UHS-II cards to the hard drive of the computer at each site once we have finished recording. The files will then be copied and saved to the two portable SSD drives to ensure the safety of the files. Photos from the camera will also be saved with this method. To process the files, we plan to use the Adobe Audition software. This is a very versatile program that will enable us to edit, compress, and combine the audio files. This program will be downloaded on our site laptop to enable us to work on the files remotely. Having this ability will dramatically decrease the time spent after the excursion on processing the data. Other applications we will have at our disposal are Audacity and the Zoom VR software. Following the end of the trip, data will continue to be processed as we do not plan to be able to go through all of it remotely, only a portion of it.

Forecasted budget