#but also all three of the villains have potential endings where their reality and justifications for continuing the cycle of abuse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

thinking Really hard about the themes of abuse and trauma and breaking cycles, and this quote from ketheric's fight at the end of act 2

#bg3 spoilers#im so serious its endgame spoilers in the tags#just poetically its nice bc of the double meaning you can take from the gods beat me first#but also all three of the villains have potential endings where their reality and justifications for continuing the cycle of abuse#just come crashing down around them before their deaths. and honestly its heartbreaking and so satisfying#the stuff u can tell orin about her mother. straight up telling ketheric to kill himself bc this is not what his family wouldve wanted#and gortash if u take him to the brain. made to feel powerless in his last moment. after his control is rejected

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your other ask and I do wonder if an actual 13 yr old Five will pop up after they stop the apocalypse. It’s so interesting to have both Fives in the same place! And to see the stark contrast between what he was without the apocalypse. How does his older self feel (and does he still look 13 too?!). And how do his siblings react realizing how much the apocalypse and the Commission took from their brother! I love this idea and your blog!!

okay a solid half of me is like “wow there’s so much potential for angst and having Five confront the fact that he lowkey hates himself and what he’s become alone with feeling redundant alongside a younger version of himself that does match up to what his siblings remember instead of being the broken old assassin he actually is”

and the other half is like “but also consider the CHAOTIC GOOD TIMES” and at heart I’m a not so secret softie so that is the louder side at the moment

SO they stop the apocalypse. They’re all trying to figure out what happens now. Five is home alone (Allison flew home for a week to see Claire/figure out her situation, Vanya is at her apartment packing some things up to move back into the mansion for a while, Diego took Grace out shopping, Luther and Klaus went to grab groceries and are probably going to come back with so much sugar because Luther is still being a pushover trying to make up for his whole ‘locked Vanya away’ debacle)

Five is sitting on the front steps of the house (it’s too empty and too quiet inside and he may or may not be coming down from a panic attack) and that’s when there’s a blue flash down the street and Five freezes. Because down the street there’s a boy turning with a puzzled look and they both catch one another’s eye and it’s like looking in a mirror because they’re the same person

So of course they go inside to figure out what the fuck and Five has no patience left for baby Five and pretty much gives it to him straight: he time traveled to April 3rd, 2019, where there was supposed to be an apocalypse. They may or may not fight when baby Five doesn’t believe him and he is convinced when Five beats him easy - thank you assassin training. There’s an hour more of incredulity and explanations as they both loudly theorize about the potential world breaking-ness of them both existing in a paradox

but hey it doesn’t seem like the world is ending and they already touched each other during the fight and nothing weird happened so,, they just both exist?

They’re sitting there quietly contemplating what next and waiting for the others to come back when baby Five, with his wonderful childish sense of mischief, looks at Five and asks a simple question: “Hey, how long do you think it would take for the others to realize there’s two of us?”

(they already had the breakdown where baby Five tried to go back in time and failed and Five smacked him because he worked really damn hard for this version of reality to exist thank you and basically informs baby Five that if he goes back the world could literally end and that’s kind of that. baby five is stuck.)

and look,,, Five is a grumpy old man assassin but he never did lose his sense of mischief - though it’s been somewhat buried over the years and especially so the last week or so. So he may or may not perk up at the suggestion with intrigue, and baby Five knows himself and knows that means he’s in so -

(Baby Five kind of feels guilty for being a little relieved he doesn’t have to go back in time actually. He wants his siblings desperately, but Reginald is dead here. No more training. No more private lessons. Freedom. And - and technically his siblings are right here, right? They’re free as well? If he jumped back in time wouldn’t that be putting them all back under Reginald’s thumb? He isn’t sure if he could do that to them... but is that just a justification to himself?)

and cue the absolute shenanigans that exist as Five and baby Five pretend that there is only one (1) of them in this timeline.

also cue some very confused siblings because there are some serious differences between the two Five’s.

Vanya is confused when she offers ‘Five’ some coffee and he wrinkles his nose and declines like he thinks coffee is gross. Which can’t be right, right? She literally saw Five chugging coffee straight from the pot yesterday?

Luther wonders if there’s something off with Five when he doesn’t seem to remember the conversation they had earlier about going to the local history museum with the rest of the family. He seemed excited earlier but now just looks put out?

(”We can’t both go to the history museum!” Five hisses at baby Five, who is rolling his eyes.

“Dude, you’re practically a dinosaur why would you even want to go to a history museum?” Baby Five points out, “Didn’t you see enough history with your little assassin job?”

Five scowls, “Maybe I just think it’s interesting considering my ‘little assassin job’ you sanctimonious child. Maybe I like museums.”

“You’re so transparent! You just want to spend time with our family.” Baby Five teases, fully aware that he’s probably going to have to dodge a knife in a second but continuing to push buttons anyway. It’s what he does. “Or - if it’s really just about all the wonderful history then we can always go again without the rest of the family.”

Five scowls as baby Five bats his eyelashes but doesn’t say anything, which means baby Five totally won the conversation, ha!)

the brilliant thing is that thanks to Five’s powers, no one thinks anything of it when they see Five downstairs and then head upstairs and see him doing something up there so even though a lot of the siblings get suspicious they probably attribute anything really off to Five’s glaring PTSD and trauma

the first one to catch on is Klaus. Well. Not really. Actually Ben is the first one to realize that he’s seeing double and tells Klaus

(”Well well well.” Klaus interrupts, making both boys on the bed jump where they had their heads bent over some mathematical textbook. Klaus is going full drama, draping himself in the open doorway like he’s a bad movie villain. “It looks like someone has been keeping secrets from your darling family.”

“Don’t tell the others!” One of them blurts, while at the same time the other growls out, “Tell the others and I kill you.”

Klaus claps his hands together, absolutely delighted. “So you aren’t the same person! Well, go on, introduce me. Is this your slightly less evil twin?”

They both exchange glances. There’s an short nonverbal conversation consisting of vague gestures and shrugs before one Five rolls his eyes and turns away, clearly done with this whole situation. The remaining Five smiles brightly and waves, “Hey Klaus! Long time no see, almost seventeen years now right?”

There’s a second of processing before Klaus gets it - or maybe Ben gets it and relays the information it’s unclear - and his hands fly to his face as he gasps loudly. “You’re a baby! A child! Under our rooftop!”

“I’m thirteen.” Baby Five protests while Five snickers under his breath. Age is a point of contention between the duo.

“What which one of you did I offer alcohol to the other day?” Klaus demands.

Baby Five raises his hand.

“I knew there was something off about you saying no to booze!” Klaus declared, pointing dramatically. Then he blinked. “Wait I offered alcohol to a minor!”

“You’re such a hypocrite.” Baby Five rolls his eyes again, “Like a week before I came here I had to half carry you to your room you were so wasted and you were thirteen.”

“He has a point.” Klaus muses to the air, probably commenting to Ben. “But I’m still not seeing a way that you two aren’t gonna get your butts totally whupped by the others when they find out about this little charade.” He says charade with a fancy french accent that hopelessly mangles the word.

The two share a look again, and again it’s baby Five who takes the lead. It may or may not be that he’s the better of the two with people considering he didn’t spend forty some years in isolation.

He grins at Klaus with bright eyes, “Aw, c’mon Klaus. It’s just a game! Besides, isn’t it more fun to be in on it?”

“Hmm.” Klaus hums, making a show of thinking it over. All three of them know exactly what the outcome is going to be, though.

“Please Klaus!” Baby Five demands, still grinning, and he suddenly looks so young and unburdened that there isn’t even a question about whether Klaus is going to be in on it or not.)

It’s not that the two don’t fight. They do. Because Five doesn’t understand how he could ever be so naive and reckless and impulsive (even though he really should expect it considering he jumped through time in the first place) and Five doesn’t understand how he got so grouchy and old and weird about so many things

but they usually solve it by shoving it down and getting along through bribery basically

(”...want to learn how to use a sniper rifle?” Five offers into the tense silence.

There’s a solid pause where baby Five is clearly mulling that over before he finally turns in the chair to face his twin. “...Griddy’s on the way home?”

“Deal.”)

It takes an alarmingly long time for the ruse to fall apart, and it 100% happens because both Five’s show up at the same time due to a miscommunication where they immediately devolve into a yelling match about how it was totally their turn downstairs and the other is an idiot and they’re literally spatial jumping after one another around the room before Diego throws two knives and manages to pin both of the arms of their uniforms to the wall and make both stop

“What the fuck is this?” Diego demands, gesturing between the two Five’s wildly.

“It’s his fault!” Both Five’s point at the other

but the ruse is up and the duo are able to hop down whenever they like and torment the family.

This au is full of healing and baby Five teaching old Five how to be a kid again and more of less rubbing off on Five and dragging him into games and appealing to his sense of mischief and drama and also making the rest of the family go to like,, the zoo or laser tag or a water park

baby Five is still holding out for disney world, personally

and they are a ferocious team up,, like literal terror twins they are fully capable of terrifying the pants off of the rest of the family and then turning around and laughing and looking innocent enough that it was difficult to say no because they’re kids and are fully capable of bringing out the rest of the family’s protective instincts

even if they know intellectually that one of that duo is an assassin who could kill them in the same breath it took to tell them what idiots they were being because he could protect himself

I dunno I just want actual kid!Five dragging grumpy old man!Five into shenanigans that Five complains about but secretly likes going along with them because lets be real who doesn’t like doing impulsive childish shit from time to time and he has an excuse because he has to stop baby Five from getting himself killed, right?

after all, as Five will defend himself, he isn’t sure if his younger self’s untimely death will also kill him, right? As a future version? Kind of like the whole “you can’t kill your grandmother” argument or whatever, right? Time is weird shush

(even though they’re both pretty sure that old Five is actually from an alternate dimension vs. time travel and that this is actually baby Five’s universe, but their worlds didn’t diverge until old Five popped in eight days before the apocalypse so technically baby Five’s death probably wouldn’t have any effect on old man Five but

hey, better safe than sorry, right?)

Baby Five feels kind of indebted to old Five for,, you know,,, saving his siblings by preventing the apocalypse and preventing him from a fate worse than death with not having to deal with isolation and the apocalypse?? so he’s more patient than old Five probably deserves

and old Five feels kind of responsible for baby Five because they both know baby Five can’t go back in time and unravel everything with how delicate it is and so baby Five still lost the equivalent of his entire family since he doesn’t exactly know these older version anymore and

hey, who knows the other better than themselves, right? Baby Five understands old Five’s motivations and shares history, knows exactly how far he would go for his family when pushed

so yes now they’re essentially twins and 100% pretend to be one another constantly and get on the others nerves and help each other heal and that’s the tea on that

#ask me#anonymous#twins au#sort of#that's what i'm calling it#tua#tua au#the umbrella academy#luther hargreeves#diego hargreeves#allison hargreeves#klaus hargreeves#five hargreeves#number five#ben hargreeves#vanya hargreeves#i would try differentiate them beyond baby five and five but#i don't think either would be willing to have another name tbh#the name five is too tied into their identities#plus they know who the other is#it's only other people who would get confused#and they live to inconvenience other people#can you imagine the handler or a commission agent showing up#WAIT#I SHOULD CALL THIS THE DOUBLE TROUBLE AU#double trouble au#n i c e

560 notes

·

View notes

Text

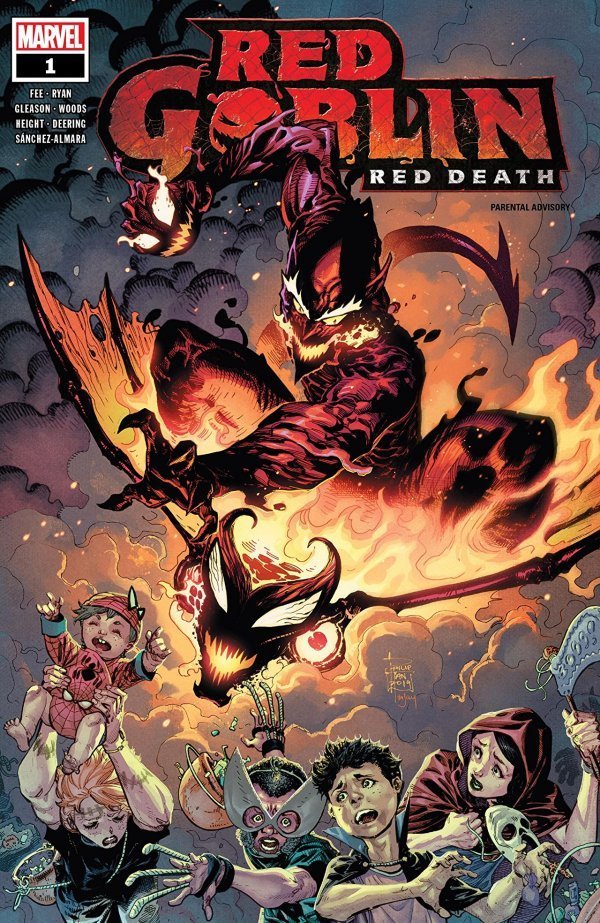

Red Goblin: Red Death #1 Thoughts

To my surprise this was an anthology comic book so I’ll be covering all three stories separately.

I really should’ve covered this back around Halloween as it was clearly written and released to capitalize upon that occasion.

But since life got in the way and I’m a British person who dismisses Halloween as Americanized horseshite you are getting this now.

So an important thing to note about this issue is that it was clearly written to capitalize upon Absolute Carnage. In fact I and other people were downright certain that this would be set during or after AC, and would be the inevitable result of Norman Osborn’s subplot throughout the story. Particularly the original motion comics hosted on Marvel’s official Youtube page.

My thinking was the end result of those and everything else that’d happen to Norman in AC was going to lead to him regaining his mind and thus become Red Goblin again, as the latter is a form created from Norman+the symbiote, whilst throughout AC Norman with Cletus’ mind has simply looked like classic Carnage.

That isn’t what this comic book is.

In fact beyond a cash in, I have no idea why Marvel thought these stories were worth publishing.

Maybe they believed they could trick people as they tricked me. Hopefully they wanted to milk the Red Goblin brand one last time before getting rid of it, much as they tried to milk the Scarlet Spider brand one last time before Ben Reilly became Spider-Man.

Or maybe they just knew that Halloween would coincide with Absolute Carnage so using a famously Halloween themed villain who is also kinda sorta Carnage made sense.

Because you see folks every one of these stories takes place BEFORE Absolute Carnage. In fact with one possible exception they all take place before ASM #800!

This really should’ve been published during or after that comic book as like ASM #800.1. In fact for those who (somehow) ENJOYED the Red Goblin story arc I’d honestly recommend reading it after ASM #800 or reading the three stories at roughly the points at which they happen in-universe during that arc.

Or don’t because frankly these are all shite. Nevertheless I’ll tell you as best I can when roughly they should occur chronologically. That ‘as best I can’ qualifier is there because I only skimmed Red Goblin (because fuck that shit is why) and because some of these are confusing to place.

The first story is called ‘Great Responsibility’, and it takes place roughly after ASM #796.

It raises an amusing thematic idea, that from Norman’s twisted point of view it is his responsibility to satisfy the Carnage symbiote’s bloodlust in order to have access to it’s great power.

But the story baffling plays Norman as essentially opposed to senseless violence.

Um...that’s kinda accurate I suppose.

It depends very much on how much you are willing to give the author the benefit of the doubt. Me personally, that’s not much if any.

Because you could MAYBE argue that from Norman’s point of view everything he says regarding killing is true, that he only killed out of necessity and he’s not always got the best perception of reality and ethics so he might be conveniently forgetting the times he definitely didn’t kill out of necessity (like I dunno, Gwen Stacy or Flash Thompson!).

But what’s much more likely to my eyes is that the writer was either desperately trying to find a way to distinguish one psychopathic killer from another to create conflict or more likely...he just didn’t know/get Norman’s character in the first place.

The sad thing is Norman is definitely NOT like Carnage in his attitude to killing.

Oh, he’s a sadist and a mass murderer, but there are subtle differences. Carnage kills for the sheer thrill of it and he doesn’t tend to savour the experience. He’ll kill randomly anyone in randomly anyway. Norman though, Norman kills people who get in his way, or out of spite, or with a specific intent to hurt someone else.

Case in point he abducted and killed Gwen Stacy partially due to holding a grudge against her personally but more significantly due to holding a grudge against Spider-Man. In particular he knocked her off the bridge out of pure spite so he couldn’t rescue her.

In theory though had Gwen never been part of Norman or Peter’s social circle, she’d have never found herself harmed by Norman. In contrast had she lived she, like everyone else, was a potential victim of Carnage waiting to happen because he’ll kill anyone, anywhere, anytime for any reason.

To Norman he’d never be reluctant to engage in senseless murder in this context as it’s simply collateral damage of what amounts to a business relationship with the symbiote. And Norman if anything, is a businessman. In a sense that’s what the whole first page (which is actually pretty well paced and panelled) is about, it’s just that Norman’s reluctance doesn’t ring true and he’s way less cold and calculating than he normally would be.

As for the Carnage symbiote, maybe I’m forgetting something or not read enough Carnage stories (I did read and skim A LOT though to prep for Absolute Carnage) but I felt it was a little bit too articulate and human considering it’s typical characterization. I’m willing to concede to being wrong on that though is symbiote experts can cite sources to the contrary.

I also don’t quite understand why they’re communicating verbally, let alone in public, considering that the symbiotes systemically can talk to you in their heads. Then again I admit that’s not been a consistent rule, even back in the earlierst Venom stories.

What is definitely IS a consistent rule though is that the symbiotes CAN kill without hosts which is the crux of this whole story.

Norman himself must actively participate in senseless murder to satiate the symbiote, it can’t just do it on it’s own.

This is another example of the direction of the story being okay but the justifications for that direction being dumb. Why not simply have the symbiote threaten to leave Norman or suggest killing on it’s own before returning to him, but Norman not trusting it to come back?

What’s especially dumb is that a symbiote literally kills in one of the motion comics in Absolute Carnage and Venom killed Angelo Fortunato by abandoning him mid-leap. Hell it forced Brock to jump off of buildings in Paul Jenkins’ run.

Now when it comes to the scenes of Red Goblin selecting targets there is some nice characterization to be had for Norman. His intelligence is on display as he wants to select people who wouldn’t arouse suspicion (although I don’t know why, surely people would just presume it’s Carnage not him thus still giving him the element of surprise when he finally fights Spidey). To this end he refuses to kill a man with a wedding ring. Instead, in a very Norman move, he suggests a disabled person.

His selection of a drug dealer who lives out of the city is a logical one. But his rationale that the world would be better without him is illogical as Norman doesn’t not give a fuck about the world’s well being at large. That same moment has an example of the Carnage mischaracterization I spoke of. The symbiote talks the way Cletus would with pop culture references and all, but that’s not how the symbiote itself would talk.

The symbiote is in character though when it goes off book and naturally escalates the violence to a much larger degree than Norman wanted.

That’s all fine but Norman’s characterization as kinda...beta and horrified by this violence is really, really not. Similarly if Norman wanted to keep a low profile whilst murdering it makes no sense for his face to be exposed literally outside the burning building he just slaughtered people in.

There is one great part about that though, which is when Norman and Carnage’s dialogue merges into one. That’s a great feat on the lettering department’s hands.

There is however a weird tease in that same scene where there is a survivor spying on Red Goblin. I don’t get it? He doesn’t show back up in this story or the Red Goblin arc, so where is this going? Nowhere would be my bet.

A final thing to note is that the art by Pete Woods looks really, really great!

Over all this was an unnecessary, filleriffic and generally lame story that didn’t need to be told.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stargate SG1 s10e12 ‘Line in the Sand’

Does it pass the Bechdel Test?

Yes, twice.

How many female characters (with names and lines) are there?

Three (33.33% of cast).

How many male characters (with names and lines) are there?

Six.

Positive Content Rating:

Three.

General Episode Quality:

The goods.

MORE INFO (and potential spoilers) UNDER THE CUT:

Passing the Bechdel:

Carter and Vala talk about using Merlin’s device. Carter explains the device’s functions to Thilana.

Female characters:

Samantha Carter.

Vala Mal Doran.

Thilana.

Male characters:

Hank Landry.

Cameron Mitchell.

Teal’c.

Reynolds.

Matar.

Tomin.

OTHER NOTES:

Aisha Hinds is such a great-looking person.

Tomin smacks Vala in the face for talking back to him because he’s...a great guy. He apologises to her later, and Vala doesn’t exactly accept the apology, but she also doesn’t not accept; she makes an equivocating statement about how hitting her is nothing compared to the genocide Tomin has been engaging in on the Ori’s crusade, and I’m not sure what point that’s trying to make, actually. I mean, yeah, on the no-no scale of actions, knocking someone down is quite a few notches below mass murder, but the inherent wrongness of one action doesn’t cancel out the wrongness of another, and altogether I’m not sure what narrative function Tomin hitting Vala is supposed to perform, I’m not sure what the equivocation is supposed to convey. Did we need Tomin to violently lose his temper and then be contrite in order to demonstrate that he doesn’t like what he’s become? Because - as Vala points out to him and us - it’s the genociding that Tomin should really be worried about, compared to which a smack in the head is inconsequential. So, why is it there? Why did the writers decide that this cute little piece of violence was plot-necessary, when they were just gonna turn around and label it meaningless in-story and then have Tomin start ‘redeeming’ himself by episode’s end? I tend to think they had him hit Vala for the sheer drama of it, just to spice things up, and that’s not a good reason to beat a woman. I know. Shocking take.

Carter has a letter for Cassandra in her personal messages, for dissemination in the event of her death. This is the good shit.

Tomin protests the Prior’s interpretation of the positive messages in the book of Origin, and how they are being “twisted into a hammer, and used to beat people down”. It’s a great delivery, and I really dig the exploration of how fundamentalists can re-define the same text that comforts and inspires others to peace, making it into a justification for their atrocities instead. THIS, this is the top-shelf stuff.

Frankly, I think they’ve kinda bungled their handling of Tomin. Not just because of the above-noted hitting incident; Tim Guinee is great, he’s doing strong work in giving Tomin as much nuance and believability as possible, and Tomin is an essential character to have around in terms of giving the injustice of the Ori’s manipulation a sympathetic human face (such as it is). The problem is, this is only Tomin’s third episode.

His introductory episode was ‘Crusade’, the penultimate episode last season, and I noted in that review the importance of the function the episode was performing: that it reminded the audience of what was truly sinister about the Ori, what our characters were really fighting against: subjugation and indoctrination. Tomin is the character who embodies those evils, as Vala watches him in that episode changing from the kind man who took her in, to a soldier ready to kill without mercy in the name of his misguided beliefs. Unfortunately, the second episode Tomin appeared in (this season’s premiere) didn’t use him to very particular effect, nor did it really reinforce his role in the story, focusing more on the introduction of Adria as the new Big Bad and the face of the Ori threat. Thus, we come to this episode, Tomin’s third, and it’s easy to have forgotten that he existed while he was gone. The episode does do a solid job of getting back to what Tomin’s function in the narrative is, and his argument with the Prior about the abuse of his faith is an excellent portrayal of that function. But it’s also kinda too little, too late: we’ve had too much other plot happening in the meantime, and putting a sympathetic human face back on the Ori’s subjugated-and-indoctrinated followers doesn’t really fly after having the battle represented by the not-at-all-sympathetic Adria all season and especially recently (she was in three of the last five episodes). And when you’re bringing Tomin back in so we can talk about all the killing he’s done and also have him knock his wife around a bit before he up and declares he’s had enough of being a bad guy, it’s really hard to still be conveying that original sweet-but-misguided concept.

Tomin is, essentially, the Teal’c of this plot - raised in an oppressive regime and made into a warrior by his poser-God(s), and representing a race of people forced into the same who just need to be shown the light and given a way out of their toxic situation - but where Teal’c became a member of the main cast of the show and therefore had his process of personal redemption and of rescuing his people from the clutches of their false Gods happening right there in front of the audience episode by episode, Tomin has...appeared three times, and only twice in a meaningful way. And there are no other sympathetic Ori followers for him to bounce off or work with or try to save, it’s just him, and a bunch of faceless randos that no one has really expressed any concern for. By under-using Tomin, the show has never really anchored itself around the idea of rescuing the Ori’s followers the way that Teal’c hoped to liberate the Jaffa, it’s just a concept that is occasionally referenced and has no real representation to make it feel important. Additionally, the multiple tiers of villainy in the Ori plot are working against presenting a cohesive vision of the problem they present: the Ori themselves are a threat to the Ancients (WHO CARES??), and they’re the ‘real’ bad guys, but they also have zero (0) plot presence, we never actually face them at all, they’re just the idea of a villain. Adria, thus, is performing the function of villainous figurehead, even though she’s not the actual problem and it’s not clear what difference it would make if she wasn’t around, since she’s basically just a Prior who is complicit in the Ori’s evil. The Priors, previously, were the ones who represented the evil of the Ori despite being apparently unaware they were being misled, which actually puts them in the ‘innocent’ column in the same sense as the Jaffa, AND YET they are also treated as being worse than the Ori foot-soldiers, the poor regular schmoes who apparently just need to have their not-Gods killed so that they can...magically not be religious anymore? Like I said back in ‘Crusade’, this is the show’s problem with the Ori plot: they can’t keep track of their own motives.

The Goa’uld were not complicated, they were bad guys in a really clean and clear way, and the fact that the Ori situation is more complicated does not make it better. The reality is, being ‘false Gods’ is a false problem - the Asgard were false Gods too, but they were benevolent so no one cared - the problem is (say it with me now) SUBJUGATION AND INDOCTRINATION. It’s what made the Jaffa, it’s what made the Ori’s followers, and it’s what makes any religious fundamentalist sect that exists right here in the real world. The evil is in taking over control of people’s free will, limiting their worldview and their ability to even understand that they have other options in life than what is prescribed for them, and it’s about abuse of power: demanding that people do as you say because you have the power to punish them if they don’t. The Ori aren’t evil because they pretend to be Gods, or because they interfere with the ‘lower planes’, or because they oppose the ideals of those useless Ancient pricks. They’re evil because they usurp the free will of others, and respond with violence if their supremacy is challenged. That’s simple, and it’s what Tomin is meant to embody. The show just keeps on forgetting that, because having Adria and the Priors around to do mind tricks is more fun, and having faceless Ori armies and their ships slaughter everything in their path is more daunting, and addressing the idea of de-programming people who have been SUBJUGATED AND INDOCTRINATED is way trickier, especially if you’re not gonna keep a character around long-term in order to do the work. As usual, I am left pining for the slightly-more-serious and slightly-more-serialised version of this show, the one that doesn’t exist. Yet.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Year in Review - Books I Read In 2017

Last year I only read about a hundred of other people's works, so I was able to note everything. This year....was not like that. By more committed Gutenberg-grinding, I increased that number by a factor of three. These are the highlights, excerpted notes on stuff that I found particularly good, or relevant, or interesting.

Robert Wallace - The Tycoon of Crime Another Phantom adventure, though this one holds back the appearance of the great detective a little and actually sets up a few tricks that aren't immediately obvious. Most are, though, and this is not a great mystery, but it's a competent enough pulp, well-flavored with brutality and gore that's almost heartrending in the modern day -- because it's a callback to the trenches of the Western Front, where bad-luck wounds, dismemberment, and poison gas were just everyday facts of life. That look in passing into the world of the men who wrote this stuff and were looking for it in their reading is the main attraction of this nowadays, but if you're looking to read a Phantom story, this is probably the pick of the litter.

Edgar Rice Burroughs - Apache Devil There are a few pulled punches in this, but not a lot, and in addition to a gripping narrative this story also packs a lot of good craft and a more united plot than it seems at first glance. It's interesting from the modern perspective to see Burroughs so sympathetic to the Apache in the context of his vigorous racism against "savages" from other places; some of this may be closer exposure to Native American culture and thus the greater willingness to credit them as human beings, and some of it may be him pitching to his audience, where American natives were crushed, nearly extinct, and eulogizable, while black people were making the Great Migration out of the south and creating economic anxiety. Either way, this is a pretty good book and not as garbage in its politics as Burroughs frequently is.

Abraham Merritt - Seven Steps To Satan Merritt's Eastern lore is well-worked into this tale, and more importantly he does a good job of keeping the reader on their toes, guessing what of this Satan's tricks are magic and what are just that, tricks. The intersection of magic, illusion, manipulation, and hypnotism is a neat contrast to the usual suspicions of occultism, and the effect is really neat in keeping this Indiana Jones adventure full of darkness and mystery. Harry is a little too obvious a plot jackknife, but you have to get to a resolution somehow, and he doesn't stick out too much in this world of super-minds and super-drugs. Merritt has better stuff, but this is pretty good even so.

Stella Benson - This Is The End I had a limited selection of Benson's stuff, but this is definitely the choice of the batch. As smart and observant as ever, and with nearly as flawless and perfect a flow of language and an eye for metaphor as in Living Alone, she also turns all of this around into a punishing, apocalyptic hammer of emotional weight and import at the turn and through on to the devastating finish. I'd been reading up on the Somme and Verdun campaigns, which would have been the backdrop offstage for this, so this may have hit me harder than others, but it's hard to see how that ending, and Benson's poetry woven in around her prose, could fail to have the same effect regardless of circumstances.

Walter S. Cramp - Psyche For real, I nearly miscopied this author's name as "Crap" when writing this out. This one is BAD, folks. You can introduce your characters with a physical description if you like, though it does get kind of fan-ficcy, but do not attach a goddamn alignment readout to it. The descriptions suck, the deliberate archaisms in dialogue suck -- do not write 'thou' unless you are going to use 'you' elsewhere to show correct tu/vous formulations in older English -- the staging and plotting sucks, and Cra(m)p can't be bothered to keep a consistent tense. This is an awful book and should have been pulped a hundred years ago rather than continuing to waste people's time and electrons down to the present.

J. A. Buck - Sargasso of Lost Safaris Everything you need to know about this insistently self-footbulleting series can be found from the episode here, where in the middle of a taut thriller about bad whites and educated natives double-crossing each other, the protagonists fight the world's worst-described dinosaur for pagecount. No explanation, they just needed another 500 words between two chapters and so they roll on the random monster table and get a fucking Baryonix or whatever. The 'girl Tarzan' trope is at the outer edges of reality, and Tarzan did a lot of Lost World garbage too, but too much of this is too true to life to fuck itself over by throwing in dinosaurs like it aint a thing. Fuck this stupid shit.

Wilhelm Walloth - Empress Octavia "Death was to stalk over it like a Phoenician dyer, when he crushes purple snails upon a white woollen cloak till the dark juices trickle down investing the snowy vesture with a crimson splendor." When you write this sentence, stop. Just stop. I have bad habits like this too, but nothing, even a translation from German, is a justification for throwing out a sentence like that, especially in a second paragraph. Stop. No. Beyond this, this is yet another Ben-Hur wannabe that is in love with its research and can't decide what fucking tense it's in. If you are interested in Rome, read Gibbon or Tacitus, or Suetonius or Caesar himself; if you want literature, stay the FUCK away from the Bibliotheca Romana. The plot takes directions that only a German can and would go in, in its period, but this boldness alone is not enough to excuse the poor composition and overall aimlessness.

Stephen Crane - Maggie: A Girl of the Streets I'm sure this was revolutionary when it came out, but at this distance, it feels like parody or melodrama - a lot of which is coming from the dialect, which is even more intolerable in the present than it was when this was written. This isn't even hard dialect, and there's no need for it to be consistently phonetic rather than, like, just describing people's accents. You look at "The Playboy of the Western World" and what that doesn't do with forcing pronunciations, and then you look back at this, and you see rapidly which one does a better job of conveying the lifestyles of the deprived and limited. I know this is supposed to be heartbreaking, but it's completely outclassed and replaced, for modern audiences, by The Jungle, which more people need to re-read and actually understand as a labor story rather than a USDA tract. Anything, literally anything, else you can get out of Stephen Crane is going to be better than this.

John Peter Drummond - Tigress of Twanbi Seriously, this story would be greatly improved by getting the Tarzan shit out of it. If it was Hurree Das, picaresque Indian doctor versus Julebba the Arab Amazon with their countervailing motivations and the local allies who ended up in the crossfire of her domination war in the African bush and his attempts to stop it or at least get out with a whole skin, this tale would be significantly improved in addition to completely unidentifiable for the white audience it had to be sold to at the time of publication. So it goes. Drummond's side characters are significantly better than his leads or his plots, and should have held out for a trade to Stan Weinbaum or P.P. Sheehan for a case of beer plus a player to be named later rather than having to submit to this dreck.

Robert Eustace - The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings Playing like a series of Eustace's Madame Sara stories -- there's definitely something to peel the onion on there, where every villain is a mysterious older Latin woman -- the plot here moves by the usual bumps of caper and medical/forensic detection, with seldom an attachment from one episode to the next. The individual stories are entertaining, but this is a collection, not a novel, and going from front to back is like binging a TV series in novella form. The individual tricks range from lame and overdone to Holmesian superclass, but this would be so much better if there was an actual whole narrative rather than this point to point.

Augusta Groner - The Pocket Diary Found In The Snow If I had gotten to this before Three Pretenders, I definitely would have thrown in a shoutout callback to Joe Mueller somewhere; Groner's Austrian detective is a more modern Holmes in a Vienna at the end of its rope, and in addition to the neat characters and relatable scene dressing, the mystery here is pretty good and the inevitable howdoneit epilogue is actually interesting rather than tiresome, which is always a potential stumbling block in this sort of caper. Most of Groner's work that I have is pretty short, but at least I'll have the possibility of re-reading her in the original German later.

Anonymous for The Wizard - Six-Gun Gorilla It's easy to see why nobody, so far, has come forward to claim this clunky Western with a hilarious concept played absolutely straight. This is a Madonna's-doctor's-dog exercise in crank-turnery written in Scotland by Brits who have never been to the high desert, for an audience that needs to be told that bandits aren't particularly interested in mining. As a craft exercise, there's some merit to it: anyone can write a gorilla-revenge story in Africa, or a Western manhunt, but when an editor comes to you and says "so there's this gorilla and he's a badass gunfighter, write a story to fit these illustrations and make it not suck", that's when you really have to stretch your creative muscles. There are signs that this was a house name product or a collab rather than one author, and more insistent signs that it was a joke played on the readership to see how long they'd put up with it. It's almost magic realist in its combination of brutality and absurdity -- who the hell knows what British schoolboys thought of it in 1939.

Robert W. Chambers - The Slayer of Souls Probably not the inspiration for that song that was on like every compilation in Rock Hard and Metal Hammer in summer 2005, this Chambers joint is either pitched perfectly for the Trumpist present -- did you know that Muslims, socialists, Chinese people, unionists, and anarchists are all actually the same, and all actually parts of a gigantic Satanist conspiracy? oh wow such deep state many alex jones -- or an incoherent stew of staunch J. Edgar Hoover fanboyism that can't keep its own geography straight, which is actually kind of the same thing so never mind. This is exactly the sort of story that George Orwell was so hot about in "Boys' Weeklies": good, craft-wise, and definitely gripping, but utterly complicit in a way and to a degree that almost becomes self-parody. If you can stop laughing at it, it's got the good action and aggressively-expansive world-setting of good rano-esque anime; if you can't, Chambers has better short stories and have you heard of this guy called Abraham Merrit?

Stendahl - The Red and the Black It is maybe over-egging it a little to call this a 'perfect' novel, but it is closer to that perfection than it is to any other reasonable descriptor. The society of the Bourbon restoration may be lost to us, but the characters stand the test of time, and Stendahl moves them in time with the plot -- the way that their actions are only tenuously liked to their outcomes is a triumph of realism -- with the hand of a master. I like Stendahl's Italian stuff too, but France in his own time is his best course, and this is his best work.

Sylvanus Cobb - Ben Hamed What's really striking about this sword and sandal mellerdrammer is how relatively non-racist it is, and how easily it accepts Muslims as real people and mostly normal. There's a bunch of orientalism, sure, but while the Giant Negro sidekick occasionally comes off servile, he's also smart, experienced, and independent, and takes, for his characterization, an appropriately central role in shepherding the star-crossed lovers to the end of their tale. This could easily get a banging Arab-directed film adaptation today with very few changes -- and that's not just about how good it is as entertainment, but also about how far Cobb was ahead of the curve in 1863.

Talbot Mundy - C. I. D. Another inter-war Indian thriller, this excellent spy novel pits a wide range of the native-state establishment -- corrupt priests, a venal rajah, the incompetent British Resident, a motley gang of profiteers -- against the genius and initiative of Mundy's great hope for India, the always effective, never moral Chullunder Gose. As expected, the top agent of the Confidential Investigations Division masterfully controls the whole chessboard, pitting the various enemy forces against each other and subverting each in turn before throwing in his reserves -- Hawkes, back in a smaller role as British India yields to British-Indian cooperation, and the obligatory American, a pre-MSF doctor who starts the book looking for a Chekhov's tiger hunt. Thing is, this is fiction, and so it's Mundy who's really keeping all these balls in the air and weaving the skein of the story into an incredibly awesome whole. If you have problems with Kipling and Haggard, start getting into Mundy from here. A neat thing that will not go unnoticed by other pulp deep-divers is the shots-fired bit introducing the Resident's library, which is noted to feature the works of Edgar Wallace. Whether to make a point in the story -- "every colonial section chief, no matter how actually bad, secretly thinks of himself as Sanders", which I've used in my own stuff -- or to start beef -- "people read Wallace and think he knows about the colonies, but he has actually just been to the track and his apartment and needs to stfu before idiots making policy off his 'exceptionally stupid member of the Navy League circa 1910' worldview hurt somebody" -- this is definitely a callout, and definitely intentional.

Gordon MacReagh - The Witch-Casting I'm reading these Kingi Bwana stories in order, and it is getting suspiciously clear that as long as he put in a bit of African-kicking at the start, he was free to get as smart and real as he liked later in the story -- and the amount of kicking was something that there were subtle efforts to reduce. This one starts off with Kaffa getting the brunt of it, but almost immediately turns around on that point as King and a larger collection of nonwhite friends-as-much-as-trusties do a witch-hunt unlike any witch-hunt you'd expect from '30s pulp, with a similarly sharp turn on African traditional religion that's nearly as out of place. MacReagh cannot completely escape his own prejudices or the expectations of his time, but this one gets as close to the event horizon as any of his stuff.

Titus Petronius Arbiter - The Satyricon The modern age has ground a lot of the obscenity off this one, which for many years was mostly famous, infamous and/or banned for its central plots of man-on-man sex; in 2017, it takes more than boyfucking to shock people. This is probably for the better; with the false atmosphere of licentiousness cut out of it, this is as it was at the beginning, a spicy story of Roman idiots having hilarious misadventures that, by subtle exaggeration, hold the follies and fads of their time up to ridicule. It is longer than it needs to be, and some of the jokes are poorly preserved, and this translation is contaminated by unnecessary footnotes and inclusion bodies of later forgers' porn that's been stapled in over the centuries, but it's still a good, true look at Rome as it actually was at the height of the empire, without the hagiography of a historian or the religio-political axe-grinding of the Christians. Probably worth the struggle.

Willa Cather - April Twilights I was collecting Cather from her papers at the University of Nebraska, and had to read this in the process of reformatting it; poetry does not well survive HTML->ASCII transitions. The deep and dark and bleak is strong here; through the classical allusions, the callbacks to Provencal troubadours, across the American landscape, the same refrain runs: "I am old and decrepit and not emotionally capable of loving other people". So, relatable. The widespread criticism of Cather, that she can't get herself out of traditional modes even when this is to her disadvantage, is held up by her poetry as well; there's more than a few places here where you've got to frown at a bodgingly conventional rhyme or metaphor that someone more open to modernity would almost have had to have done better. But there are, even still parts where that traditionalism works well, and is effective; it's worth reading out for those, even at all that.

H.P. Lovecraft and others - Twenty-Nine Collaborative Stories Most of what we now recognize as the Cthulhu Mythos -- and definitely any kind of idea of Lovecraft's stuff as a coherent whole or linked world-system -- comes out of these stories as much as his own. On his own, Lovecraft moved to the beat of his own drum and followed his ideas where they went; here, he helps friends and fans plug their fanfic into what becomes a shared universe. The stories are not all great; Hazel Heal put up some classics here but also some stinkers, and most of Robert Barlow's contributions, especially as they range into sci-fi, are kind of eh. Zealia Bishop, though, does yeoman service as Lovecraft's official trans-Mississippian correspondent, and Adolphe de Castro's top-class works settle Lovecraftian mysticism in real foreign lands. It's worth getting through these: there's good stuff in here, and you also get the sense and feel of how Lovecraft actively built his 'school' -- and ensured that he was the one to influence the direction of weird fiction for years to come.

William Hope Hodgson - The House on the Borderland A true classic, this is potentially the very most black metal horror novel ever written. The brutality of the swine creatures, the remote devastation of the time-blasted cosmos, the liminality of dreams and reality; Teitanblood and Xasthur and Inquisition hope and fail to convey this sense of unholy immensity, of uncaring timeless evil. Hodgson hits some heights in his shorter stories, but here, he hits it absolutely out of the park. Completely essential.

Suetonius - The Life of Claudius Claudius comes off in this one like I've observed German colonial rule as remembered in most places other than Africa: "not worse than necessary". Suetonius doesn't miss the caprices of a guy who almost certainly was on the spectrum, and had other distinguishing impairments, but also faithfully records a lot of good works and good ideas, with less wastage and idiocy than the likes of his surrounding emperors. The translator's appendix, as expected, freaks out about the results of Claudius' expedition to Britain, and continues to vainly expect the Roman people to want to get rid of effective and oppressive imperial rule to get back to the ineffective oppression of the senatorial republic. How someone who translates Latin can be ignorant of "senatores boni viri, senatus mala bestia" and what that actually means in the context of government is beyond me.

Julius Caesar - De Bello Civili This is in three parts, double-text, and when I can understand what places are being talked about (still not 100%, even after all of this, on where the heck in Italy Brundusium is), it flows well and is as clear in its language as anything else of Caesar's. Even the structure is well-laid: in book 1, Caesar starts the war, and wins a big victory in Spain; in book 2, one of his generals gets disastered in Africa; and in book 3, the epic conclusion and final battles. Though this is still ultimately a public relations exercise, Caesar doesn't step back from his own disasters, and gives full credit to his foes: this does tend to make him look better when he beats them up, and it is curious how nothing is ever directly his fault, and how most reverses go to troops losing their head and acting without orders, which would be out of character for his faithful super-army if it didn't keep happening. As always, Caesar leans on logistics; his focus on the relative supply situations in Spain and in Thessaly is the key to success, and a dead giveaway that this was written or at least dictated by the commander himself, and not by some biographer who wouldn't've had that experience in keeping an army fed and watered in the field.

Katherine Mansfield - Something Childish and Other Stories What's really cool in this collection of earlier Mansfield is that you get to see her evolve through the War: she's already mature, and really good, in the New Zealand and Continental tales that precede it, but after the title story (dated to 1914, with a collapse-out at the end that is a KILLER allegory for that August, even if unintended), you really start to see how the nervous stress of total war wears on a population engaged, how the greater position of women in society transforms her and her work, and leads her on towards self-discovery. The later and more experimental stories are, in general, slightly better, but this is all good material -- and there's a hell of a sting in the tail at the end.

Henry W. Herbert - The Roman Traitor In his introduction Herbert mentions a friend who encouraged him to finish this book, without which it would never have been released. This friend should be dug up and beaten soundly with rocks, because this rehash of the Catilline conspiracy is utterly unnecessary as a novel or as antiquarianism, and Herbert is an awful, awful writer whose torture of language and narrative structure would shame a Nero. The day you write the phrase "bad conclave" is the day your editor should throw you through a door. This isn't the worst book in the Bib. Romanica, but it may be the very most badly written. Just read the actual history from Sallust and forget this stupid garbage.

Gustave Flaubert - Salammbo This takes a while to really get its feet under it and show where it's going, but once it does, look out. Flaubert masterfully captures the brutality of warfare and the color of the ancient world, and his language is superbly translated; you put this next to the staid English garbage in the rest of the Bib. Romanica and you wonder why most of them even bothered. The turn at the end hits like a ton of bricks, especially if you like me don't know anything about Carthaginian history and don't know what's coming -- but it's also the only possible ending for this captivating chronicle of horror, misery and nightmare. Just excellent.

Willa Cather - My Antonia A deeply drawn narrative of love, growth, and the midwestern plains, this book is more enhanced than anything else by Cather's commitment to its place and time: childhood is always a lost world forever, but the place that Jim and Antonia grow up through is thoroughly lost a hundred years and more on, but it survives in these pages down to the dirt on the floors and the chaff under the characters' collars. After the narrator goes to Omaha, the tale weakens a little, and the end, for modern audiences, is probably a little under-tuned, but this is Cather's flagship novel for a reason, and definitely rewards the time spent reading it.

Margaret Atwood - Negotiating With the Dead This is another lecture series like the Forster above, but coming from different source, moving in different ways, and much more about Atwood herself and the roots of her writing in the Canadian landscape and literary scene that shaped her. There is a lot about writing as a living thing in this book, and very little about it as a process: it's kind of a synthesis-antithesis-conclusion out of Forster and Bickham, more perceptive than either and leaving Welty, poor soul so far from the modern perspective, in the absolute dust. It may be a question of eras, or just one of sympathies -- an adequately intelligent writer of speculative fiction is going to necessarily fall in with Atwood's ideas about doing something meaningful that also keeps the lights on -- but this book, out of all of the four in this mini-course, hit the most home and told me the most about what I do that I didn't already know. It doesn't have the coherent, lecturized feel of the Forster, but at times there are just the most amazing insights, and the craziest images out of that crazy time that was the middle 20th century, and with how good it was I'm fairly ashamed to not have read any other Atwood before it, which makes me just an awful person. At least I'm in a damn library and probably can fix that now.

Willa Cather - The Bohemian Girl A novella that should probably better and more widely reputed than it is, this one is mostly a meditation on love, maturity, and switching horses in midstream, but Cather, like no one else, manages to defend both the dour, hard prairie homestead and the need to escape from it. This is her "zwey seele wohnen, ach, in meinen Brust", and it's kind of a thing all through her fiction, but in here it's especially well developed, with a coda that unlike a lot of her other ones actually works.

Talbot Mundy - The Marriage of Meldrum Strange Sales figures or editorial comment must have highlighted the "big team" problems in the last book, because this one cuts it down to the essentials: Ommony and Gose and Ramsden for muscle and some minor characters. The plot is a good and twisty romance, keeping everything real, and it is just magic to watch Ommony work calm while Gose spits science like a Bollywood comedian, yin and yang combining to catch everyone in every trap. A rare gem after several misfires.

Talbot Mundy - Old Ugly-Face One of Mundy's real best, this is an epic navigation of the human heart, against the majestic Himalayas....played by psychics battling to ensure the succession of the Dalai Lama. Mundy gon Mundy, but the love triangle here is perfect and the environments are astounding -- a must read.

D. W. O'Brien - Blitzkrieg in the Past There's a chapter in this one called "Tank Versus Dinosaur", and that's about the shape of it. You could also say "Sergeant Rock goes to Pellucidar" and not miss by much; a M3 Grant and crew ends up in a fantasy cavemen-and-dinosaurs past and has some adventures while talking '40s smack, and then romps their way home. What's cool about it for authors is how O'Brien writes around his dinosaur: there is no description at all of the beast or its species or attributes. It is big, and makes angry noises, because the author could not be assed to take the time out to do research while writing this story. And yet it works, unless you're reading really close; let this be a lesson for anyone who can't finish their research up exactly correct on deadline.

Talbot Mundy - The Ivory Trail A lot of this raw, brutal epic of survival in the east-African backcountry is probably from life; Mundy tried this life and failed at it before he became a writer, and the asides and incidental scenes can only be from bitter experience. Others might expect a purer adventure -- you'd get one from MacReagh on these materials -- but Mundy has the essential truth of colonialism: there are no secrets, mere survival is hideously tough, and everyone else in the game is more brutal and better equipped. Conrad might have had the literary chops and adventurousness to end this differently, but even he who fared into the Heart of Darkness didn't have the stomach to write a middle passage like Mundy does here with his heroes in German prison.

Talbot Mundy - Guns of the Gods This Yasmini adventure makes itself a prequel, of her youth and how she got into the position of wealth and information mastery that sets up her later career. The plot is tight if less convoluted than some that I've been reading lately, and the incidents woven through the intrigue and the treasure hunt are fantastic. On a deeper level, the real judgment and sensitivity in the negotiation of east and west by Tess and Yasmini makes up for the stray Americans happening into the heart of the tale, and in a real way this is Mundy's most openly and solidly anti-Raj, pro-Home Rule adventure yet. For both an excellent story and what's probably a local maximum in wokeness, this comes highly recommended.

Thorne Smith - Rain In The Doorway A kind of Alice in Jazz Age NYC, this is a ridiculous madcap adventure that loses little in the passage of time and not much at all in the way it winds back down to reality. Smart and stupid and sexy in all the best ways, this kind of hilarity is pretty much Smith's best stock in trade, and this particular book is one of the better examples.

Thorne Smith - Turnabout The least hair of maturity creeps into Smith's writing here, as one of his interminable boozing Lost Generation miscouples actually gets in a family way as well as into an inexplicable supernatural adventure. The very very familiar central trick is well executed, and Tim's advancing pregnancy provides a nice frame to hang the rest of the events off of. The end is a little pat with the reinsertion of the Dutch uncle, but you live and deal. This is one of Smith's better, and a good occasion to round out the end of the string.

Wilkie Collins - Armadale Collins makes up for his bad start with this absolute beast of a romance, bound up with mysticism rather than being an encyclopedia, but still turned out with real and vital if slightly implausible people. The consistent mystery of the vision unites the book, but the way that the various Armadales react to that vision, its interpretations, and each other, is solid and real. It is an immense read that demanded like six hours of flight time, but it is definitely rewarding, and worth the bother of pounding through the huge narrative.

Wilkie Collins - No Name There is a tangled tale and a half in this one, a desperate adventure of roguery in the name of revenge that keeps getting tangled up with coincidence as much as fate or intent. The links may be a little creaky, but this is a huge, smart, intensely twisting drama with a lead for the ages in Magdalen, and an adversary worthy of her steel in Lecomt. The end is a little formula and takes a little long to wind down, but this is an artifact of the time and the expected conventions, and it inhibits the power of this novel but little. Good good stuff.

Talbot Mundy - The Thrilling Adventures of Dick Anthony of Arran "For a few days Cairo swallowed Dick." NO. Shut it. Shut up. Be mature. Tuned to a compositional level somewhere between Sexton Blake and Lovecraft's middle-school works, this is not good or well-written Mundy, and there are research holes in it that might have been stabbed through with a claymore. In places, his later quality pokes through, but in the main this is a stolid imitation of part Kipling, part John Buchan by a writer who does not have enough name weight to force publishers to his way of thinking rather than the reverse. This leftover should have stayed left over and buried.

These were excerpted from the full writeups of the complete chronological list below, which accounts for frequent hanging references. The pure volume of this list indicates why I didn't copy the whole of the writeup blocks into this entry.

Robert Barr - The Sword Maker E. Rice Burroughs - Land of Terror E. Rice Burroughs - Tarzan and the Leopard Men L. Winifred Faraday (tr) - Tain bo Cuailnge Robert Barr - The Triumphs of Eugene Valmont Richard Rhodes - The Making of the Atomic Bomb Robert Wallace - Death Flight Richard Rhodes - Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb Richard Rhodes - Twilight of the Bombs Robert Wallace - Empire of Terror Robert Wallace - Fangs of Murder Robert Wallace - The Sinister Dr. Wong Mary Cagle - Let's Speak English! Robert Wallace - The Tycoon of Crime Stella Benson - Kwan-yin William H. Ainsworth - The Spectre Bride Robert Eustace - The Face of the Abbot Robert Eustace - The Blood-Red Cross Robert Eustace - Madam Sara Robert Eustace - Followed Robert Eustace - The Secret of Emu Plain Arthur Conan Doyle - The Uncharted Coast Edgar Rice Burroughs - Apache Devil Edgar Rice Burroughs - Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins Edgar Rice Burroughs - Tarzan the Invincible William W. Astor - The Last of the Tenth Legion Edgar Rice Burroughs - Tarzan the Magnificent Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Bandit of Hell's Bend Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Cave Girl Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Deputy Sheriff of Comanche County Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Efficiency Expert Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Girl From Farris' Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Girl From Hollywood Stella Benson - Living Alone Stella Benson - The Desert Islander Victor Appleton - Tom Swift and his Giant Telescope Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Lad and the Lion Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Man-Eater Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Moon Men Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Outlaw of Torn Edgar Rice Burroughs - The Rider Edgar Rice Burroughs - The War Chief Abraham Merritt - Burn, Witch, Burn! Abraham Merritt - Creep, Shadow! Abraham Merritt - Seven Steps To Satan Abraham Merritt - The Dwellers in the Mirage Abraham Merritt - The Face in the Abyss Abraham Merritt - The Last Poet and the Robots Edward Spencer Beesly - Catiline, Clodius, and Tiberius Malcolm Jameson - Collected Stories Fantasy Magazine - The Challenge From Beyond The Strand - As Far As They Had Got J. M. Synge - The Playboy of the Western World Abdullah/Brand/Means/Sheehan - The Ten-Foot Chain Stella Benson - This Is The End Stella Benson - Twenty Emily Beesly - Stories From the History of Rome Hugh Allingham - Captain Cuellar's Adventures in Connaught and Ulster, A.D. 1588 James DeMille - The Martyr of the Catacombs Sallust - Bellum Catalinae Edmond Rostand - Cyrano de Bergerac "Captain Adam Seaborn" - Symzonia, A Voyage of Discovery R.E.H. Dyer - Raiders of the Sarhad Walter S. Cramp - Psyche H.P. Lovecraft - From Beyond Robert F. Pennell - Ancient Rome Garrett Putnam Serviss - Edison's Conquest of Mars Irving Batcheller - Charge It Irving Batcheller - Vergillius Duffield Osborne - The Lion's Brood Dale Carnegie - How to Win Friends and Influence People J. A. Buck - The Slave Brand of Sleman bin Ali J. A. Buck - Killers' Kraal J. A. Buck - Sargasso of Lost Safaris J. A. Buck - Sword of Gimshai Wilhelm Walloth - Empress Octavia Stephen Crane - The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky Stephen Crane - The Blue Hotel Stephen Crane - The Open Boat Stephen Crane - Maggie: A Girl of the Streets Stephen Crane - The Monster and More Stendahl - Armance Victor Appleton II - Tom Swift and the Electronic Hydrolung Victor Appleton II - Tom Swift and the Visitor From Planet X Robert Curtis - Edgar Wallace Each Way John Peter Drummond - Bride of the Serpent God John Peter Drummond - The Nirvana of the Seven Voodoos John Peter Drummond - Tigress of Twanbi Robert Eustace - The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings Augusta Groner - The Pocket Diary Found In The Snow Augusta Groner - The Case of the Registered Letter Augusta Groner - The Case of the Lamp That Went Out Augusta Groner - The Case of the Golden Bullet Augusta Groner - The Pool of Blood in the Pastor's Study Anonymous for The Wizard - Six-Gun Gorilla Walter Horatio Pater - Marius the Epicurean John Russel Russell - Adventures in the Moon and Other Worlds Answers Magazine - Sexton Blake J. U. Giesy with Junius B. Smith - The Occult Detector J. U. Giesy with Junius B. Smith - The Significance of the High "D" J. U. Giesy with Junius B. Smith - The House of Invisible Bondage Stendahl - The Abbess of Castro and Others John Aylscough - Faustula John Aylscough - Mariquita Robert W. Chambers - The Maker of Moons and Other Stories Robert W. Chambers - The Slayer of Souls Edith Nesbit - My School Days Edith Nesbit - Re-collected (self re-collection) Edith Nesbit - The Magic World Edith Nesbit - Wet Magic Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Planet of Doubt Stanley G. Weinbaum - Smothered Seas Stanley G. Weinbaum - Graph Stanley G. Weinbaum - Flight on Titan Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Red Peri Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Black Flame Stanley G. Weinbaum - The Dark Other Stanley G. Weinbaum - The New Adam Gordon MacReagh - re-collected shorter stories (self re-collection) Stendahl - The Charterhouse of Parma Stendahl - The Red and the Black Sylvanus Cobb - Atholbane Sylvanus Cobb - Ben Hamed Sylvanus Cobb - Ivan the Serf Sylvanus Cobb - Bianca Sylvanus Cobb - Orion the Gold-Beater Sylvanus Cobb - The Gunmaker of Moscow Sylvanus Cobb - The Knight of Leon Sylvanus Cobb - The Smuggler's Ward Talbot Mundy - Black Light Talbot Mundy - Burberton and Ali Beg Talbot Mundy - C. I. D. Talbot Mundy - Caesar Dies Talbot Mundy - For the Salt Which He Had Eaten Talbot Mundy - From Hell, Hull, and Halifax Talbot Mundy - Full Moon J. U. Giesy - Palos of the Dog Star Pack J. U. Giesy with Junius B. Smith - The Wistaria Scarf J. U. Giesy with Junius B. Smith - The Purple Light Gordon MacReagh - The Slave Runner Gordon MacReagh - The Ebony Juju Gordon MacReagh - The Lost End of Nowhere Gordon MacReagh - Quill Gold Gordon MacReagh - Unprofitable Ivory Gordon MacReagh - The Witch-Casting Gordon MacReagh - Strangers of the Amulet Gordon MacReagh - The Ivory Killers Gordon MacReagh - Black Drums Talking Walter Moers - The 13 1/2 Lives of Captain Bluebear Gordon MacReagh - Wardens of the Big Game Gordon MacReagh - Raiders of Abyssinia Gordon MacReagh - A Man to Kill Gordon MacReagh - Slaves For Ethiopia Gordon MacReagh - Strong As Gorillas Gordon MacReagh - Blood and Steel Gordon MacReagh - White Waters and Black Cardinal Newman - Callista J. U. Giesy with Junius B. Smith - The Master Mind Titus Petronius Arbiter - The Satyricon Talbot Mundy - Her Reputation Giancarlo Livraghi - The Power of Stupidity Willa Cather - April Twilights H.P. Lovecraft and others - Twenty-Nine Collaborative Stories J. U. Giesy with Junius B. Smith - Rubies of Doom Abraham Merritt - The Moon Pool Abraham Merritt - The Metal Monster Abraham Merritt - The Ship of Ishtar John G. Lockhart - Valerius William Hope Hodgson - Carnacki, Supernatural Detective and Others William Hope Hodgson - Carnacki the Ghost Finder William Hope Hodgson - The House on the Borderland Suetonius - The Life of Julius Caesar Suetonius - The Life of Augustus Caesar Suetonius - The Life of Tiberius Caesar Suetonius - The Life of Caligula Suetonius - The Life of Claudius Suetonius - The Life of Nero Suetonius - The Life of Galba Suetonius - The Life of Otho Suetonius - The Life of Vitellus Suetonius - The Life of Vespasian Suetonius - The Life of Titus Suetonius - The Life of Domitian The Lock and Key Library - Classic Mystery and Detective Stories - Old Time English Hume Nisbet - The Demon Spell b/w The Vampire Maid Hume Nisbet - The Land of the Hibiscus Blossom Hume Nisbet - The Swampers E. Hoffman Price - The Girl From Samarcand Flavius Philostratus - The Life of Apollonius H. P. Lovecraft - At the Mountains of Madness H. P. Lovecraft - Selected Essays including Supernatural Horror in Literature H. P. Lovecraft - The Case of Charles Dexter Ward H. P. Lovecraft - The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath and Others H. P. Lovecraft - The Dream Cycle H. P. Lovecraft - The Dunwich Horror H. P. Lovecraft - The Shadow Out of Time H. P. Lovecraft - The Shadow Over Innsmouth H. P. Lovecraft - The Whisperer in Darkness H. P. Lovecraft - His Earliest Writings H. P. Lovecraft - Poems and Fragments (self re-collection) H. P. Lovecraft - The Cthulhu Mythos (self re-collection) H. P. Lovecraft - Tales of Monstrosity (self re-collection) H. P. Lovecraft - Tales of the Crypt (self re-collection) H. P. Lovecraft - Tales of Paganism (self re-collection) Edward Bulwer-Lytton - The Last Days of Pompeii Gavin Menzies - 1421: The Year China Discovered America Ernst Eckstein - Quintus Claudius Julius Caesar - The African Wars Julius Caesar - The Alexandrine War Julius Caesar - De Bello Civili Julius Caesar - The Hispanic War Talbot Mundy - Cock o' the North Julius Caesar - The Gallic Wars Katherine Mansfield - Bliss and Other Stories Katherine Mansfield - In A German Pension Katherine Mansfield - Something Childish and Other Stories Katherine Mansfield - The Garden Party and Other Stories John W. Graham - Nearea Andy Adams - A Texas Matchmaker Andy Adams - Cattle Brands Andy Adams - Reed Anthony, Cowman Andy Adams - The Log of a Cowboy Andy Adams - Wells Brothers Charles Kingsley - Hypatia Francis Stevens - Claimed! Francis Stevens - Nightmare! Francis Stevens - Serapion Francis Stevens - The Heads of Cerberus Francis Stevens - The Rest of the Stories (self re-collection) Talbot Mundy - Hira Singh Henry W. Herbert - The Roman Traitor Robert Howard - Tales of Breckenridge Elkins Robert Howard - Tales of El Borak Robert Howard - Tales of the West Robert Howard - Swords of the Red Brotherhood Robert Howard - The Black Stranger Robert Howard - The Pike Bearfield Stories Robert Howard - The Exploits of Buckner Jeopardy Grimes Robert Howard - Weird Poetry (self re-collection) Robert Howard - Collected Juvenilia Robert Howard - The Spicy Adventures of Wild Bill Clanton (self re-collection) Robert Howard - Tales of the Weird West (self re-collection) Robert Howard - The Treasure of Shaibar Khan Robert Howard - Red Blades of Black Cathay Robert Howard - The Isle of Pirates' Doom Robert Howard - Dig Me No Grave Robert Howard - The Garden of Fear Robert Howard - The God in the Bowl Virgil - The Aneid Gustave Flaubert - Herodias Gustave Flaubert - Madame Bovary Talbot Mundy - Hookum Hai Gustave Flaubert - Salammbo Willa Cather - Alexander's Bridge Willa Cather - My Antonia Eudora Welty - On Writing E.M. Forster - Aspects of the Novel Jack M. Bickham - The 38 Most Common Fiction Writing Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them) Margaret Atwood - Negotiating With the Dead Arthur Conan Doyle - Fairies Photographed Arthur Conan Doyle - Great Britain and the Next War Willa Cather - My Autobiography, by S. S. McClure Willa Cather - O Pioneers! Willa Cather - One of Ours Willa Cather - The Song of the Lark Heinrich Brode - Tippu Tib Willa Cather - The Troll Garden Willa Cather - Youth and the Bright Medusa Willa Cather - The Bohemian Girl Willa Cather - The Affair at Grover Station Willa Cather - The Count of Crow's Nest Willa Cather - The Shortest Stories (self re-collection) Willa Cather - Tales ABC (self re-collection) Willa Cather - Tales DEF (self re-collection) Willa Cather - Tales G-K-O (self re-collection) Willa Cather - Tales PRST (self re-collection) Willa Cather - Stories W (self re-collection) Henryk Sienkiewicz - Quo Vadis Charles Darwin - The Voyage of the Beagle Sinclair Lewis - Babbitt Talbot Mundy - Jimgrim and Allah's Peace Talbot Mundy - East and West Talbot Mundy - The Iblis at Ludd Talbot Mundy - The Seventeen Thieves of El-Khalil Talbot Mundy - The Lion of Petra Talbot Mundy - The Woman Ayisha Talbot Mundy - The Last Trooper Talbot Mundy - The King in Check Talbot Mundy - A Secret Society Talbot Mundy - Moses and Mrs. Aintree Talbot Mundy - The Mystery of Khufu's Tomb Talbot Mundy - Jungle Jest Talbot Mundy - The Nine Unknown Talbot Mundy - The Marriage of Meldrum Strange Talbot Mundy - The Hundred Days Talbot Mundy - OM: The Secret of Ahbor Valley Talbot Mundy - The Devil's Guard Talbot Mundy - Jimgrim, King of the World Talbot Mundy - Machassan Ah Talbot Mundy - Oakes Respects An Adversary Talbot Mundy - Old Ugly-Face Talbot Mundy - Payable to Bearer Talbot Mundy - Poems and Dicta Talbot Mundy - Rung Ho! Talbot Mundy - Selected Stories Gordon MacReagh - Projection From Epsilon Leroy Yerxa - Back from the Crypt (self re-collection) Garrett P. Serviss - A Columbus of Space Garrett P. Serviss - The Moon Metal Garrett P. Serviss - The Second Deluge Garrett P. Serviss - The Sky Pirate Sinclair Lewis - Arrowsmith Robert Buchanan - Camlan and the Shadow of the Sword Robert Buchanan - God and the Man Henry R. Schoolcraft - To the Sources of the Mississippi River D. W. O'Brien - Squadron of the Damned D. W. O'Brien - Blitzkrieg in the Past D. W. O'Brien - The Floating Robot D. W. O'Brien - Gone In 20 Kilobytes (self re-collection) D. W. O'Brien - Lost in Space (self re-collection) D. W. O'Brien - Ghosts of War (self re-collection) William Ware - Aurelian William Ware - Zenobia J. S. Fletcher - The Stories (self re-collection) J. S. Fletcher - Perris of the Cherry-Trees J. S. Fletcher - The Middle Temple Murder J. S. Fletcher - The Paradise Mystery J. S. Fletcher - The Safety Pin Francis H. Atkins - The Short Stories (self re-collection) M. P. Shiel - In Short (self re-collection) Francis H. Atkins - A Studio Mystery Francis H. Atkins - The Black Opal Talbot Mundy - The Eye of Zeitoon Talbot Mundy - The Ivory Trail Talbot Mundy - The Man From Poonch Talbot Mundy - The Middle Way Talbot Mundy - The Red Flame of Erinpura Talbot Mundy - The Thunder Dragon Gate Talbot Mundy - Tros of Samothrace Talbot Mundy - Queen Cleopatra Talbot Mundy - Purple Pirate Talbot Mundy - A Soldier and a Gentleman Talbot Mundy - Winds of the World Talbot Mundy - King of the Khyber Rifles Talbot Mundy - Guns of the Gods Talbot Mundy - Caves of Terror Thorne Smith - Biltmore Oswald: The Diary of a Hapless Recruit Thorne Smith - Biltmore Oswald: Very Much At Sea Thorne Smith - Birthday Present Thorne Smith - Did She Fall? Thorne Smith - Dream's End Thorne Smith - Haunts and By-Paths Thorne Smith - Rain In The Doorway Thorne Smith - Skin and Bones Thorne Smith - The Bishop's Jaegers Thorne Smith - The Glorious Pool Thorne Smith - The Night Life of the Gods Thorne Smith - The Stray Lamb Thorne Smith - The Jovial Ghosts: The Misadventures of Topper Thorne Smith - Topper Takes A Trip Thorne Smith - Turnabout Thorne Smith - Yonder's Henry Wilkie Collins - Antonina Wilkie Collins - Armadale Wilkie Collins - I Say No Wilkie Collins - Miss or Mrs Wilkie Collins - My Lady's Money Wilkie Collins - No Name Wilkie Collins - The Haunted Hotel Wilkie Collins - The Law and the Lady Leroy Yerxa - Death Rides At Night D. W. O'Brien - Flight From Farisha Gordon MacReagh - Out of Africa (self re-collection) Peter Cheyney - Quick Draws (self re-collection) Talbot Mundy - The Thrilling Adventures of Dick Anthony of Arran D. W. O'Brien - The Last Analysis M. P. Shiel - Children of the Wind Edgar Wallace - 1925: The Story of a Fatal Peace M. P. Shiel - Prince Zaleski Edgar Wallace - A Case For Angel, Esquire M. P. Shiel - Shapes in the Fire Edgar Wallace - A Deed of Gift M. P. Shiel - The Evil That Men Do Edgar Wallace - A Debt Discharged M. P. Shiel - The Last Miracle Edgar Wallace - A Dream M. P. Shiel - The Lord of the Sea Edgar Wallace - A Raid on a Gambling Hell

0 notes