#bookforum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Agnès Varda

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Out now.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

PICTURE, IF YOU WILL, Joan Didion sitting on the floor of a Los Angeles recording studio in 1968, gazing up at Jim Morrison of the Doors, a band she went on to describe as “apocalyptic missionaries of sex.” If our patron saint of Californian disenchantment ever appeared starstruck, even girlish, it was surely here, in the presence of the Lizard King. (“An attempt to cast a spell,” she once called her use of repetition as a literary device. That the phrase “black vinyl pants” occurs three times in her vignette about the Doors tells us all we need to know.) Also in the studio that day were, Didion writes, “a couple of girls,” and of those “couple of girls,” one was the writer and adventuress Eve Babitz, an ex-lover of Morrison’s who was not quite as enamored of his cod-shamanic shtick. The Doors “had lyrics you could understand about stuff [kids] learned in Psychology 101,” Babitz wrote in 1991 in Esquire, an eye roll detectable in print. Didion claimed to like the Doors because “their music insists that love is sex and sex is death and therein lies salvation.” Babitz did not think that love was sex or sex was death, only that sex was sex, and having peeled off those black vinyl pants for herself, she’d seen too much of the man to buy the myth. Imagine calling your most self-serious ex an “apocalyptic missionary of sex” with a straight face. As Didion herself would say: does not apply.

“It was Eve, by the way, who set up the meeting” between Didion and Morrison, Lili Anolik reveals in Didion and Babitz. Anolik is a podcaster and contributing editor at Vanity Fair who is best known for reintroducing Babitz to the culture in a 2014 essay for that publication, after tracking her down as an elderly recluse and bonding with her in the last years of her life. She describes her relationship with Babitz—which yielded her first book, the freewheeling 2019 biography Hollywood’s Eve—as “unbalanced,” even “fetishistic.” Didion and Babitz is inspired by Anolik’s discovery of an unsent letter to Didion in Babitz’s archive at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in Los Angeles County (the Huntington acquired Babitz’s archive in 2022) . The letter’s tone, alternately pleading and furious, is one that Anolik immediately recognizes as that of “a lovers’ quarrel.” The two women had a history: Didion first got Babitz published by sending a copy of her story “The Sheik” to Rolling Stone in 1972; in exchange, Babitz added Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, to the long list of dedicatees in Eve’s Hollywood in 1974. Now and then, they socialized, and they seemed to be, in modern parlance, casual “frenemies.” This letter, a magnificent document that is among the best things Babitz ever wrote, suggests a more intense connection, and its passion reignites Anolik’s interest in her former friend and subject.

It is easy to see why: Babitz, full of piss and vinegar, berates “sharp, accurate journalist” Didion for her inability to talk about “art. Vulgar, ill-bred, drooling, uninvited Art.” It is a full-throated statement of intent from a big-brained babe who, however louche she seemed when she wrote for her public, saw herself as a committed Woman Artist. “It was back. My love for Eve’s astonishing, reckless, wholly original personality and talent,” Anolik says, overwhelmed and ecstatic. As in Hollywood’s Eve, Anolik’s voice in Didon and Babitz is fizzy, conversational, sometimes faintly loopy, as if you are being given a piece of gossip by a person who is certain it will blow your mind. She is also a self-confessed square, and this squareness gives her interest in her subjects—Babitz in particular—some of its squirrelly charge. Her aim here is to position these women as each other’s inverted mirror images: fastidious, frigorific, bony Joan, and heedless, hot, voluptuous Eve. “Each was the closest the other had,” she proposes, “to a soul mate.”

This three-way psychodrama in the studio is compelling precisely because it is, in effect, a snapshot of three individuals with big, singular personae facing off against each other. The question of what we gain or lose by taking icons at face value is a crucial one throughout Didion and Babitz—not for nothing did Norman Mailer, in 1965, describe Didion as “a perfect advertisement for herself,” and Babitz’s bimbo-genius act may have seemed artless, but as that letter proves, it was just that: an act. In her introduction, Anolik reveals that she is nervous about dissecting Didion, before asking a favor of the reader: “Don’t be a baby.” It’s a bet-hedging move that anticipates a flurry of indignant Goodreads reviews, and given Didion’s popularity with people who wear pictures of authors on their tote bags, Anolik is right to be concerned. On the other hand, I must admit that historically, I’ve been something of a baby myself when it comes to Anolik’s writing about Babitz, whom she tends to portray with a mixture of dizzy adoration and brutal honesty. In Hollywood’s Eve, she calls the older Babitz “a ruin and a gorgon,” and both books apply a flurry of stomach-churning adjectives to Babitz’s trash-filled apartment. Stripping a woman like Babitz of her glamour feels to me like a betrayal, and reading about her smelling of “decay” is like seeing her the wrong kind of naked (as opposed to the right kind—that is, when she’s playing a game of chess against Marcel Duchamp).

I prefer to see Babitz the way Didion saw Jim Morrison, with her persona intact: as an ecstatic “missionar[y] of sex.” Charisma is, however, an enchantment that is best maintained at a distance, and Anolik has been close enough to Babitz to peel off her vinyl pants, if only figuratively speaking. About two-thirds of Didion and Babitz is, well, and Babitz. Less fleshed out by far is the material about Didion, whom the author did not know, and admires somewhat less. In addition to this bias, says Anolik, Didion in general is “opaque enough, elusive enough, withheld enough, far-fetched enough, that she’s almost a ghost.” The image of Didion that emerges here is the one you might expect: that of a woman whose appearance of shyness was half real, half strategic, and whose work—which she composed carefully, rhythmically, like an orchestral arrangement—was the most important thing in her life. When Anolik bemoans the fact that people “get a little soft in the head” and “go teary-eyed at the thought of [Didion’s] wifehood, her motherhood, her widowhood, her bereft-motherhood,” I had to wonder: who, exactly? In my experience, Didion is usually loved for her chill, almost evil-seeming precision—not for her domesticity. (Perhaps it is those tote-bag carriers again.) Truthfully, I could have done without the book’s attempts to out Dunne as gay, but more for reasons of taste than because of my need to believe in the sanctity of the famed Didion-Dunne marriage, which like all marriages presumably had its own private set of rules.

The other big revelation in Didion and Babitz is the identity of Didion’s first love, a writer named Noel Parmentel Jr., who was immortalized as three separate characters in her novels, and who tells Anolik he “invented Joan Didion.” Certainly, there is no doubt that his promotion of Didion’s work in literary circles helped her move out of Vogue and into “serious” publications. Still, as with preferring to remember Babitz in her pomp, I prefer to think of Didion as the inventor of Joan Didion. Either way, there is that idea again—that of an icon being something constructed. “Joan and Eve are the two halves of American womanhood,” Anolik concludes. “The id and the superego, light and dark, sex and death.” No woman, of course, actually embodies only one of these extremes, unless she happens to be doing so deliberately to make herself into a work of art, “ill-bred” or otherwise. By the end of the book, one feels a shift in the author’s image of Babitz, even as Didion remains out of reach. If Hollywood’s Eve saw her as a “lewd angel,” here Anolik is ready to see Eve as a real “Bride of Art,” just as canny and as calculated as her “secret twin.” Being around Babitz in real life seemed to negate some of her magic for Anolik; in Didion and Babitz, the author’s realization that she might have known “the wrong Eve” all along recasts the spell. There is a third way to react to a persona: to appreciate it for the work its maintenance requires. Doing so is a form of respect, perhaps even an expression of love. What is it they say on social media? “A crush is just a lack of information.”

Philippa Snow is a critic and essayist who lives in England. Her last book, Trophy Lives, was published by Mack in 2024.

#bookforum#article#book review#books#new books#biography#joan didion#Eve Babitz#women writers#20th century#books and literature

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is nothing suspicious—or particularly gendered—about a desire to rest. But if we can sympathize in this respect with women who are drawn to the housewife fantasy, then we must also address the housewife’s immature side: her refusal of responsibility in the public sphere. The housewife lifestyle abandons the struggles of feminist advancement, community building, justice, and political engagement. It trades them for insularity, callowness, and superficial self-regard.

And here we return to Davis’s initial characterization of housewifery’s appeal: “I might have liked to hitch my wagon to someone, confident that he loved me enough that I could be comfortable in a state of financial dependency,” she writes. This desire to be taken care of, to be loved in a way that obviates responsibility, is not a fantasy of a marriage. It is a fantasy of a return to childhood. She’s not looking for a husband; she’s looking for a parent.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

lauren oyler takedown that is all the talk of literary twitter

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our tanned balls, our white selves

"...given the general state of culture these days, the mere act of writing a novel—whatever its politics or lack thereof—should be understood as a de facto leftist gesture because the contemporary right are illiterate, hateful ghouls. They don’t read books or book reviews or anything else. They binge Twitch streams, tan their balls, try to get librarians fired, and hang out in the smoldering ruins of Twitter sharing anti-Semitic memes and security-camera footage of people being murdered in the street. If you are reading this, they hate you. If you walk out of your house today and are stabbed to death with this issue of Bookforum tucked under your arm, these people will spend a week retweeting images of your dead body and joking about how that’s one weird trick for canceling student debt. While it is emphatically true that there are complicated, worthwhile intra-leftist fights to be had about what constitutes equitable discourse in our communities and our art—and specifically about how to balance an unwavering conviction in freedom of speech with the recognition that certain speech-acts have the potential to do real harm—it is also emphatically true that none of us should be censoring ourselves or each other on account of the hypothetical risk of some gooning jackboot with a Sailor Moon avatar and a sonnenrad tattoo laughing at our best jokes for the wrong reasons."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since Montaigne, the best essays have been, as the French word suggests, trials, attempts. They entail the writer struggling toward greater knowledge through sustained research, painful introspection, and provocative inquiry. And they allow the reader to walk away with a freeing sense of the possibilities of life, the sensation that one can think more deeply and more bravely—that there is more outside one’s experience than one has thought, and perhaps more within it, too. These essays, by contrast, are incapable of—indeed, hostile to the notion of—ushering readers, or Oyler herself, into new territory, or new thought. The pieces in No Judgment are airless, involuted exercises in typing by a person who’s spent too much time thinking about petty infighting and too little time thinking about anything else.

Ann Manov, Star Struck

0 notes

Text

However, in European history, as the classical languages of Greek and Latin gave way to the vernacular languages of Europe it was the active voice that was given more and more priority in how the world was talked about and thought about. The active voice is the grammatical voice that speaks as if an actor can act without being affected by the action, and can, if they wish, reverse the action. It is the voice that says that the drift is the end product of the driving wind, the cast the end product of the casting, the throw. This is the voice that laid the ground for the seemingly detached observer of modern science, the distanced actor of technology – and its passive twin our sense of the environment as mere resource or instrument (Romanyshyn 1989). Owen Barfield describes this as a process of ‘internalization’,‘the shifting of the centre of gravity of consciousness from the cosmos around him into the personal human being himself’ (Barfield 1954: 166-7).

Bronislaw Szerszynski in (PDF) Postprint version – to appear in Performance Research. Drift as a planetary phenomenon

I keep pointing to a Podcast discussion between author Sarah Jaffe and Kelly Hayes about how grief shapes our struggles because it really touched a nerve. We neglect grief at our peril. In their discussion Jaffe told about interviewing Namwali Serpell about Serpell's novel The Furrows in Bookforum, Mourning Routine. Serpell pointed to this essay by Bronislaw Szerszynski.

When I first opened the essay I didn't quite know what to do with it. I wondered what are Performanc Studies? I could tell there was a bunch of academic stuff that was going to take me some time to sort through, so I put it aside. When I finally got around to reading the essay I found it such an enjoyable and enlightening read. Of course, I did have to go look up stuff. Two links gleened from the effort to enjoy: I was pleased to discover a beautiful new translation of Johan Huizinga’s most well known book Autumntide of the Middle Ages. The edition is illustrated with 300 illustrations of works Huizinga references in the book. If you like books it's worthwile clicking on the link. The Wikipedia article on Owen Barfield was helpful to me as I hardly knew his work at all. The book referenced by Szerszynski was first publised in 1926.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

publishing fiction sounds so scary because literary critics are everywhere and they are ready to be bitchy in whatever Review of Books or Granta or Bookforum or n+1 whatever that will have them. meanwhile there are like 5 theater critics who write for 3 major publications and i do not know if anyone actually cares except other theater people

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

that bookforum review is exploding but as a sometimes-writer who tries really hard to write cultural criticism that is rigorous and well-researched and open to the thing i am considering on its own terms instead of some stupid terms that i or someone else invented and that are derived from and only apply to my own stupid life, it is soooo cathartic to have read three brutally negative reviews of l*uren *yler's book in a row, because she fundamentally sucks at doing the thing she is doing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rickey’s book on Varda reminded me of when I first saw Varda’s films and when I read all the critics in all the papers in Boston. The return of Rickey, who first encountered Varda as I did, in a college class (though hers was taught by Manny Farber), is most welcome. Her book is moving because Varda’s life was moving, and because its existence made me realize I’d been waiting for it. It brings to mind something Varda said about seeing movies and making films: “When I see a bad film, I think, ‘Films are disgusting!’ When I see a beautiful film, I think, ‘That’s what I must do. I must create a beautiful film!’”

#article#bookforum#movies#film#biography#books#book review#Agnès Varda#new book#art#art history#women in art history#photography#director

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

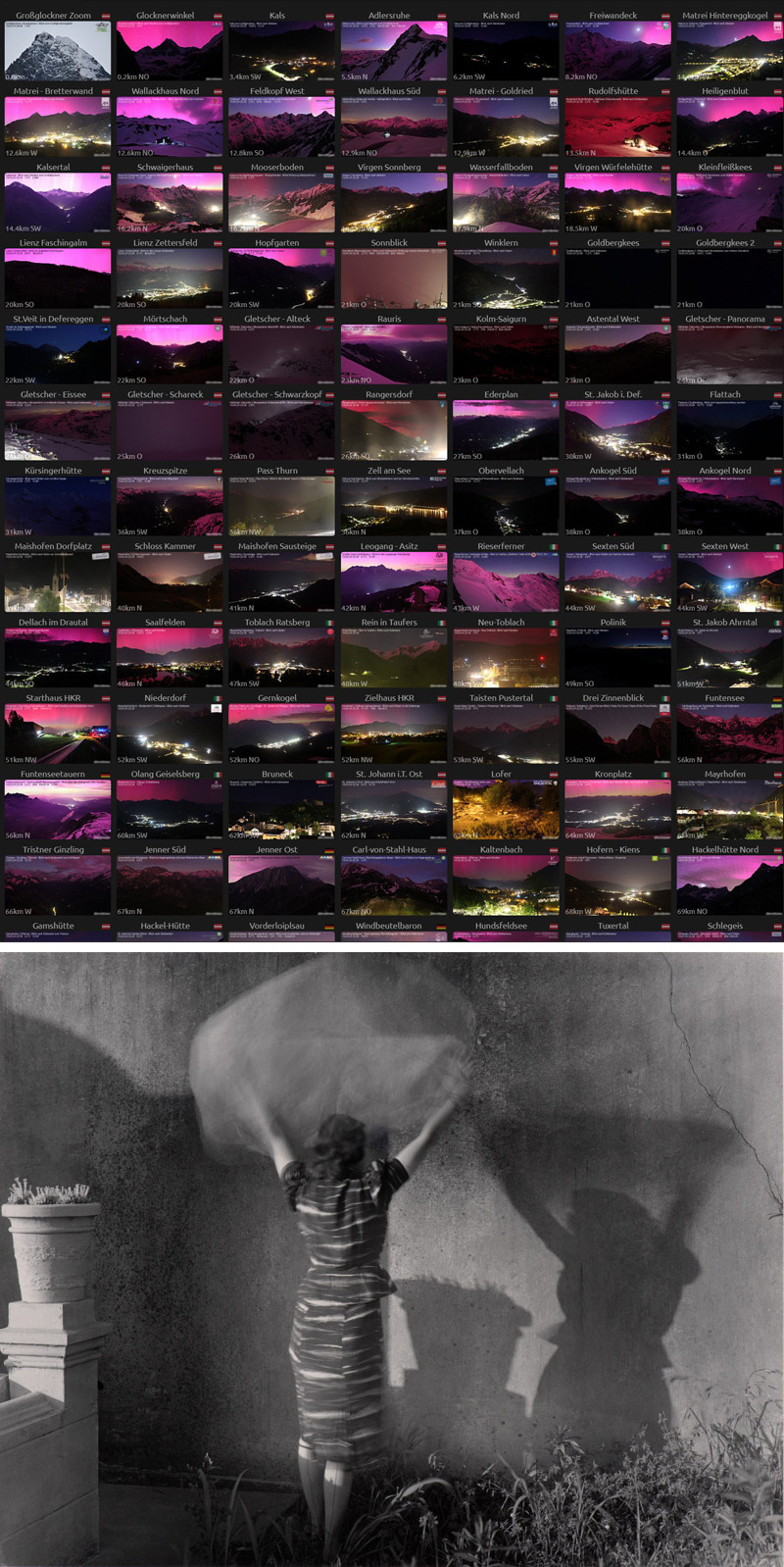

Top, screen captures from various webcams in Austria, Italy and Germany showing Northern Lights, May 10, 2024. Via Nahel Belgherze. Bottom, Clarence John Laughlin, Woman Attacked by a Cloud (Descent of a Cloud), 1941, Silver gelatin print. Via.

--

Throughout The Mystery Guest, Boullier certainly does not sound like a man in top form, and his willingness to make himself appear buffoonish saves the book from being an agonizing exercise in flowery self-pity. In the kind of perfectly ironic detail that could only come directly from real life, he decides to distinguish himself by spending more than a month’s rent on a bottle of 1964 Margaux, only to learn that as part of her artistic practice, Calle keeps all of her birthday gifts in storage in their original wrapping. (If he really had been Jesus Christ, a bottle of Evian would have sufficed.) At the party, Boullier talks shit, and crosses the line between anonymous, iconoclastic interloper and garden-variety wine-drunk jerk. The prose is breathless, sometimes drunk seeming itself, and there is something realistic, even touching, about its perpetual ricocheting between hope and despair, often within the span of a single sentence. It is a tightly written portrait of the artist as a young(ish) mess, and its ingenuity lies in its positioning of the “mystery guest” as an idealized state that exists in diametric opposition to the thoroughly unmysterious position of the ex-lover. Familiarity breeds contempt, and it can also hasten breakups. If Boullier can make himself unknowable enough again, perhaps he can represent not only Calle’s future but also that of the woman who once loved him.

His problem—much to our delight, since this dilemma is what lends the book its jittery edge—is that he cannot be mysterious to save his life. In the final pages of the book, Boullier and Sophie Calle meet again some years later, and despite his misogynistic flinching at her age (“in five years she’d be fifty-five, and then sixty, and that vision was hopeless and implacable”), it becomes clear that they are twin souls, if not necessarily cut out to be lifelong soulmates: obsessed with fate, and to some degree with themselves, they have an eye for the kind of minor details that make for terrific fiction, even when they are supposedly recording facts. For a time after this meeting, they were lovers, until Boullier eventually sent her a meandering, self-important breakup email. Calle—in a move that a man so obsessed with signs surely ought to have foreseen—anonymized him as “X” and turned the email into her 2007 entry for the Venice Biennale, Take Care of Yourself, asking women from 107 different professions, from a cruciverbalist to a Talmudic scholar, to interpret his words. If dumping a writer is a risky move, dumping an artist might be more dangerous still: like an invading force, they tend to recruit collaborators.

Philippa Snow, from We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together - Two French authors’ dueling narratives of heartbreak, for Bookforum, Spring 2024.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

read the lauren oyler bookforum takedown last night and just can’t get over this

like… holy shit lol this is so funny

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

new york's hottest night club is the bookforum lauren oyler take down

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the best publication right now for book reviews, if any?

Unless you live in New York and go to the parties where the names still matter, or unless you're devoted to subscribing to things in print, and I'm negative in both cases, the internet has leveled the field. We think in writers rather than publications now. For one thing, the publications aren't that differentiated any longer. The New Republic, The Nation, the London Review of Books, the New York Review of Books, and Bookforum all had different ideological colorings; now you can read about "late capitalism" or whatever in all of them. The new publications are better and more interesting, especially the farther they are from this ideological consensus, like Compact or the Mars Review, but their draw is that they publish very diversely in arts and culture and therefore don't have as strong an editorial line in the reviews. I'd recommend finding critics who appeal to you and following them anywhere. (Criticism and reviews aren't exactly the same either; good critics are good whether you agree with them or not; you're interested in their own literary performance as well as the one under review; whereas when I want to know in advance if I'll enjoy a book in all the practical senses of "enjoy" I usually just take the collective temperature of Goodreads and the like.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letting go of the past: what is the anti-colonial struggle? Lviv BookForum 2024, Sunday 6 October 2024

"What path should be chosen by one group that has long been subordinated to another, stronger one? Is the cancel culture the only way to break free from the domination of the aggressor?. And what if this aggressor is an empire? A discussion on how we make sense of the post-imperial heritage, and whether it is necessary to renounce it, with the Dutch writer Simone Atangana Bekono, Indian literary critic and feminist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak; Brazilian feminist philosopher and journalist Djamila Ribeiro; Nigerian writer and activist Lola Shoneyin; and Ukrainian philosopher and writer Oksana Zabuzhko. Chaired by philosopher Vakhtanh Kebuladze. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Djamila Ribeiro, Simone Atangana Bekono and Lola Shoneyin will join the event digitally."

#very interesting discussion#gradblr#studyblr#academia#dark academia#chaotic academia#colonialism#anti colonialism#imperialism#decolonization#decolonisation#Simone Atangana Bekono#Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak#Djamila Ribeiro#Lola Shoneyin#Oksana Zabuzhko#Vakhtanh Kebuladze#Philosophy#Online conference#educational video#philosophy#epistemic violence

2 notes

·

View notes