#bodenheim

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Chamomile (Tripleurospermum perforatum)Bodenheim, Germany

By Vera Buhl

0 notes

Text

The euphoric high of reading someone who has intelligent thoughts about North and South.

#It's so sad that I keep finding different versions of#Margaret Hale changes John Thornton into a Carlylean Captain of Industry#read the novel I beg you#But Bodenheimer understands the subtlety of the moral transformations in the novel#the particular way in which its highlight of interdependence as essential to human relationships#seeks to transcend the utilitarian/intuitionist liberal/paternalist divide in ethics and politics#ahhhhh like eatiing a delicious piece of dessert#FINALLY

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In my experience, the more a warrior talks, the less stomach he has for fighting.

(X-O Manowar #11)

#x-o manowar#Aric#shanhara#warrior#uh oh#space opera#matt kindt#Ryan bodenheim#valiant comics#comics#2010s comics

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

(JTA) — A public university in Switzerland is looking for its next Jewish studies professor, and one requirement on the job posting has drawn scrutiny from local Jews: all applicants to the position must be Catholic.

The opening, for a professor of Judaic studies and theology, is currently listed at the Faculty of Theology at the University of Lucerne, an hour south of Zurich.

Even though the university is public, that academic department is officially affiliated with the Catholic Church — which prohibits non-Catholic professors from teaching “doctrinal” courses such as philosophy, liturgy, scripture, Catholic theology and fundamental theology. That includes teaching about non-Christian religions such as Judaism. Non-Catholic professors may be invited as guest lecturers or visiting professors.

The Jewish studies and theology professor would be responsible for teaching and research related to Judaic studies, as well as leading the Institute for Jewish-Christian Research, according to the job posting.

Alfred Bodenheimer, who worked at the University of Lucerne from 1997 to 2003 in a Jewish teaching and research position, said the prohibition of non-Catholics hampered his career there.

“It seems to be the case that it simply doesn’t fit into our times anymore — that you say someone who teaches Jewish studies cannot be anyone else but a Catholic,” Bodenheimer, who now teaches at the University of Basel, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“I really saw that as a Jewish person at this university, I would always be something like a subaltern, with no chance to have more possibilities, influence and so on,” he added. “I became aware of the fact that this whole situation was very asymmetric, that I as a Jew would always be not on the same stage as my Catholic boss.”

Like Lucerne, the University of Basel is a public university. But its theology department is Protestant, rather than affiliated with the Catholic Church. In total, Switzerland has 12 public universities, at least two of which have Catholic Church-affiliated theology departments.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Bodenheim Castle in Euskirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

German vintage postcard, mailed in 1915 to Marseille, France

#historic#euskirchen#1915#photo#briefkaart#marseille#vintage#bodenheim castle#sepia#photography#medieval#carte postale#castle#postcard#mailed#postkarte#france#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#old#bodenheim#ephemera#postkaart#german#germany

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Schimbarea numelui i s-a părut o lipsă de loialitate. Ba chiar o renunțare la rădăcini, la începuturi, la părinți și la cei cinci frați.

#Bucuresti#Edward G Robinson#Edward G Robinson Jr#Edward Gould Robinson#FILM#Gladys Lloyd#Hollywood#Jane Bodenheimer Adler#Nașul#New York#Oscar#star de cinema#cinema#cinematography#movie#pelicula

0 notes

Text

Ryan Bondenheim - X-O Manowar

1 note

·

View note

Text

La poesia è l’impertinente tentativo

di dipingere il colore del vento

Maxwell Bodenheim

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

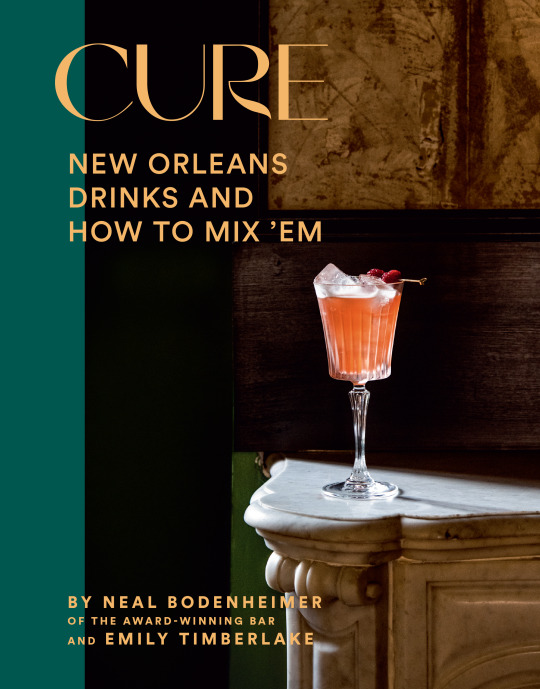

RECIPE: Irish Goodbye (from Cure: New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix 'Em by Neal Bodenheimer and Emily Timberlake)

Matt Lofink describes this as a dry, not-too-sweet, “very crushable” whiskey sour. Fennel and peach is an unexpected but delicious flavor pairing that works amazingly well with the spice notes of the whiskey.

¾ ounce (22.5 ml) fresh lemon juice

1 medium egg white

1. ounces (45 ml) Tullamore D.E.W. Irish whiskey

¼ ounce (7.5 ml) Giffard crème de pêche liqueur

¼ ounce (7.5 ml) Fennel Syrup (recipe follows)

4 mint leaves

10 drops Peychaud’s bitters, for garnish

Mint sprig, for garnish

Combine the lemon juice and egg white in a shaker tin without ice and dry-shake for 30 seconds. Add the whiskey, pêche liqueur, fennel syrup, and mint leaves to the shaker tin, fill the shaker with ice, and shake until chilled. Double-strain into a double old-fashioned glass filled with ice. Dot the bitters on the surface of the drink, then use a toothpick or cocktail straw to swirl the bitters in an attractive pattern. Garnish with the mint sprig and serve.

RECIPE: Fennel Syrup

Makes about 2 cups (480 ml)

2 tablespoons fennel seeds

2 cups (480 ml) hot (190 to 200°F/88 to 93°C) water

2 cups (400 g) white sugar

In a small skillet over medium heat, toast the fennel seeds until fragrant, 1 to 2 minutes. Transfer to a bowl, add the water, and infuse until the water is cool. Add the sugar, stir until dissolved, then fine-strain and store in the refrigerator for up to 4 weeks.

From the foremost figure on the New Orleans' drinking scene and the owner of renowned bar Cure, a cocktail book that celebrates the vibrant city

New Orleans is known for its spirit(s)-driven festivities. Neal Bodenheimer and coauthor Emily Timberlake tell the city’s story through 100 cocktails, each chosen to represent New Orleans’ past, present, and future. A love letter to New Orleans and the cast of characters that have had a hand in making the city so singular, Cure: New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix 'Em features interviews with local figures such as Ian Neville, musician and New Orleans funk royalty, plus a few tips on how to survive your first Mardi Gras. Along the way, the reader is taken on a journey that highlights the rich history and complexity of the city and the drinks it inspired, as well as the techniques and practices that Cure has perfected in their mission to build forward rather than just looking back. Of course, this includes the classics every self-respecting drinker should know, especially if you’re a New Orleanian: the Sazerac, Julep, Vieux Carré, Ramos Gin Fizz, Cocktail à la Louisiane, and French 75. Famous local chefs have contributed easy recipes for snacks with local flavor, perfect for pairing with these libations. Cure: New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix 'Em is a beautiful keepsake for anyone who has fallen under New Orleans’s spell and a must-have souvenir for the millions of people who visit the city each year.

For more information, click here.

#abramsbooks#abrams books#cure#cure cocktail book#cure nola#cure new orleans#st. patrick's day#irish goodbye#cocktail recipe#cocktails

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

What a treasure! - with a special dedication to @dinahvaginaart

Women Painters of the World, from the time of Caterina Vigri, 1413–1463, to Rosa Bonheur and the present day, assembled and edited by #WalterShawSparrow, lists an overview of prominent #womenpainters up to 1905, the year of publication.

How is this NOT ?! a compulsory book at the each and every #artcourse?! #artherstory

Here's the list of the painters (this will keep me busy for some time :)

Louise Abbéma

Madame Abran (Marthe Abran, 1866-1908)

Georges Achille-Fould

Helen Allingham

Anna Alma-Tadema

Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema

Sophie Gengembre Anderson

Helen Cordelia Angell

Sofonisba Anguissola

Christine Angus

Berthe Art

Gerardina Jacoba van de Sande Bakhuyzen

Antonia de Bañuelos

Rose Maynard Barton

Marie Bashkirtseff

Jeanna Bauck

Amalie Bauerlë

Mary Beale

Lady Diana Beauclerk

Cecilia Beaux

Ana Bešlić

Marie-Guillemine Benoist

Marie Bilders-van Bosse

Lily Blatherwick

Tina Blau

Nelly Bodenheim

Kossa Bokchan

Rosa Bonheur

Mlle. Bouillier

Madame Bovi[2]

Olga Boznanska

Louise Breslau

Elena Brockmann

Jennie Augusta Brownscombe

Anne Frances Byrne

Katharine Cameron

Margaret Cameron (Mary Margaret Cameron)

Marie Gabrielle Capet

Margaret Sarah Carpenter

Madeleine Carpentier

Rosalba Carriera

Mary Cassatt

Marie Cazin

Francine Charderon

Marian Emma Chase

Zoé-Laure de Chatillon

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

Lilian Cheviot

Mlle. Claudie

Christabel Cockerell

Marie Amélie Cogniet

Uranie Alphonsine Colin-Libour

Jacqueline Comerre-Paton

Cornelia Conant

Delphine Arnould de Cool-Fortin

Diana Coomans

Maria Cosway

Amelia Curran

Louise Danse

Héléna Arsène Darmesteter

Maria Davids

Césarine Davin-Mirvault

Evelyn De Morgan

Jane Mary Dealy

Virginie Demont-Breton

Marie Destrée-Danse

Margaret Isabel Dicksee

Agnese Dolci

Angèle Dubos

Victoria Dubourg

Clémentine-Hélène Dufau

Mary Elizabeth Duffield-Rosenberg

Maud Earl

Marie Ellenrieder

Alix-Louise Enault

Alice Maud Fanner

Catherine Maria Fanshawe

Jeanne Fichel

Author

Walter Shaw Sparrow

Country

United Kingdom

Language

English language

Genre

Art history

Publisher

Hodder & Stoughton, Frederick A. Stokes

Publication date

1905

Pages

331

The purpose of the book was to prove wrong the statement that "the achievements of women painters have been second-rate."[1] The book includes well over 300 images of paintings by over 200 painters, most of whom were born in the 19th century and won medals at various international exhibitions. The book is a useful reference work for anyone studying women's art of the late 19th century

Louise Abbéma

Madame Abran (Marthe Abran, 1866-1908)

Georges Achille-Fould

Helen Allingham

Anna Alma-Tadema

Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema

Sophie Gengembre Anderson

Helen Cordelia Angell

Sofonisba Anguissola

Christine Angus

Berthe Art

Gerardina Jacoba van de Sande Bakhuyzen

Antonia de Bañuelos

Rose Maynard Barton

Marie Bashkirtseff

Jeanna Bauck

Amalie Bauerlë

Mary Beale

Lady Diana Beauclerk

Cecilia Beaux

Ana Bešlić

Marie-Guillemine Benoist

Marie Bilders-van Bosse

Lily Blatherwick

Tina Blau

Nelly Bodenheim

Kossa Bokchan

Rosa Bonheur

Mlle. Bouillier

Madame Bovi[2]

Olga Boznanska

Louise Breslau

Elena Brockmann

Jennie Augusta Brownscombe

Anne Frances Byrne

Katharine Cameron

Margaret Cameron (Mary Margaret Cameron)

Marie Gabrielle Capet

Margaret Sarah Carpenter

Madeleine Carpentier

Rosalba Carriera

Mary Cassatt

Marie Cazin

Francine Charderon

Marian Emma Chase

Zoé-Laure de Chatillon

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

Lilian Cheviot

Mlle. Claudie

Christabel Cockerell

Marie Amélie Cogniet

Uranie Alphonsine Colin-Libour

Jacqueline Comerre-Paton

Cornelia Conant

Delphine Arnould de Cool-Fortin

Diana Coomans

Maria Cosway

Amelia Curran

Louise Danse

Héléna Arsène Darmesteter

Maria Davids

Césarine Davin-Mirvault

Evelyn De Morgan

Jane Mary Dealy

Virginie Demont-Breton

Marie Destrée-Danse

Margaret Isabel Dicksee

Agnese Dolci

Angèle Dubos

Victoria Dubourg

Clémentine-Hélène Dufau

Mary Elizabeth Duffield-Rosenberg

Maud Earl

Marie Ellenrieder

Alix-Louise Enault

Alice Maud Fanner

Catherine Maria Fanshawe

Jeanne Fichel

Rosalie Filleul

Fanny Fleury

Julia Bracewell Folkard

Lavinia Fontana

Elizabeth Adela Forbes

Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale

Consuélo Fould

Empress Frederick of Germany

Elizabeth Jane Gardner

Artemisia Gentileschi[3]

Diana Ghisi

Ketty Gilsoul-Hoppe

Marie-Éléonore Godefroid

Eva Gonzalès

Maude Goodman

Mary L. Gow

Kate Greenaway

Rosina Mantovani Gutti

Gertrude Demain Hammond

Emily Hart

Hortense Haudebourt-Lescot

Alice Havers

Ivy Heitland

Catharina van Hemessen

Matilda Heming

Mrs. John Herford

Emma Herland

E. Baily Hilda

Dora Hitz

A. M. Hobson

Adrienne van Hogendorp-s' Jacob

Lady Holroyd

Amelia Hotham

M. J. A. Houdon

Joséphine Houssaye

Barbara Elisabeth van Houten

Sina Mesdag van Houten

Julia Beatrice How

Mary Young Hunter

Helen Hyde

Katarina Ivanović

Infanta María de la Paz of Spain

Olga Jančić

Blanche Jenkins

Marie Jensen

Olga Jevrić

Louisa Jopling

Ljubinka Jovanović

Mina Karadžić

Angelica Kauffman

Irena Kazazić

Lucy E. Kemp-Welch

Jessie M. King

Elisa Koch

Käthe Kollwitz

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

Ethel Larcombe

Hermine Laucota

Madame Le Roy

Louise-Émilie Leleux-Giraud

Judith Leyster

Barbara Longhi

Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll

Marie Seymour Lucas

Marie Lucas Robiquet

Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy

Ann Macbeth

Biddie Macdonald

Jessie Macgregor

Violet Manners, Duchess of Rutland

E. Marcotte

Ana Marinković

Madeline Marrable

Edith Martineau

Caroline de Maupeou

Constance Mayer

Anne Mee

Margaret Meen

Maria S. Merian

Anna Lea Merritt

Georgette Meunier

Eulalie Morin

Berthe Morisot

Mary Moser

Marie Nicolas

Beatrice Offor

Adeline Oppenheim Guimard

Blanche Paymal-Amouroux

Marie Petiet

Nadežda Petrović

Zora Petrović

Constance Phillott

Maria Katharina Prestel

Henrietta Rae

Suor Barbara Ragnoni

Catharine Read

Marie Magdeleine Real del Sarte

Flora Macdonald Reid

Maria G. Silva Reis

Mrs. J. Robertson

Suze Robertson

Ottilie Roederstein

Juana Romani

Adèle Romany

Jeanne Rongier

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip

Baroness Lambert de Rothschild

Sophie Rude

Rachel Ruysch

Eugénie Salanson

Adelaïde Salles-Wagner

Amy Sawyer

Helene Schjerfbeck

Félicie Schneider

Anna Maria Schurman

Thérèse Schwartze

Doña Stuart Sindici

Elisabetta Sirani

Sienese Nun Sister A

Sienese Nun Sister B

Minnie Smythe

Élisabeth Sonrel

Lavinia, Countess Spencer

M. E. Edwards Staples

Louisa Starr

Marianne Stokes

Elizabeth Strong

Mary Ann Rankin (Mrs. J. M. Swan)

Annie Louise Swynnerton

E. De Tavernier

Elizabeth Upton, Baroness Templetown

Ellen Thesleff

Elizabeth Thompson

Maria Tibaldi m. Subleyras

Frédérique Vallet-Bisson

Caroline de Valory

Mlle. de Vanteuil[4]

Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun

Caterina Vigri

Vukosava Velimirović

Ana Vidjen

Draginja Vlasic

Beta Vukanović

Louisa Lady Waterford

Hermine Waternau

Caroline Watson

Cecilia Wentworth

E. Wesmael

Florence White

Maria Wiik

Julie Wolfthorn

Juliette Wytsman

Annie Marie Youngman

Jenny Zillhardt.

#womensart #artbywomen #palianshow #womeninarts #greatfemaleartist

#greatfemalepainters #herstory #forgottenartists #mustread

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#pelletofen #ecoforest #monaco mit verspiegelter #scheibe https://www.ofenhaus-mainspitze.de #mainz #wiesbaden #frankfurt #darmstadt #berlin #badkreuznach #ingelheim #oppenheim #bodenheim #alzey #rüsselsheim #grossgerau #wallau #nordenstadt #hofheim #laubenheim #stromberg #eltville #dexheim #ofenhausmainspitze https://www.ofenhaus-mainspitze.de (hier: Ginsheim-Gustavsburg) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cp8LWtUMjXr/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#pelletofen#ecoforest#monaco#scheibe#mainz#wiesbaden#frankfurt#darmstadt#berlin#badkreuznach#ingelheim#oppenheim#bodenheim#alzey#rüsselsheim#grossgerau#wallau#nordenstadt#hofheim#laubenheim#stromberg#eltville#dexheim#ofenhausmainspitze

0 notes

Text

Stop!

(X-O Manowar #12)

#x-o manowar#Aric#stop#space opera#cosmic#matt kindt#Ryan bodenheim#valiant comics#comics#2010s comics

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vers l'anniversaire du 7 octobre : le Ministère de la Santé dans un appel insolite aux médias

Vers l’anniversaire du 7 octobre : Le Dr Gilad Bodenheimer, directeur de la division de santé mentale au ministère de la Santé, et Shira Shapira, directrice des infrastructures patrimoniales au ministère du Patrimoine, ont publié une lettre aujourd’hui (lundi) avant le triste anniversaire de la catastrophe du 7 octobre au cours duquel ils font un appel au public et aux médias. “De nombreuses…

0 notes

Text

Rottach-Egern - Bodenheim - Doha (Qatar)

Maandag 12 augustus - woensdag 14 augustus

Yeeuuhhh ik ben jarig vandaag! 🥳 Het vierde opeenvolgende jaar dat ik het ergens in het buitenland vier. Puur toeval overigens, niet expres gepland. Tja, dat heb je als je in de zomer jarig bent 😁.

Ik begin de dag lekker relaxed. Heel leuk om alle lieve verjaardagsfelicitaties te lezen onder het genot van een lekker bakkie. Dank jullie wel!

De camperplaats was ook echt top! Voelt ook relaxed en de mensen waren ook erg aardig.

Vandaag wordt een 'rij-dagje' richting Bodenheim, waar ik ook op de eerste avond stond. Het is een fijne plek en vlakbij het vliegveld van Frankfurt waarvandaan ik morgen vertrek richting Kazachstan. De rit duurt ongeveer 5 uur. Maar ik heb bewust gekozen om te vliegen vanaf Frankfurt in plaats van München. Het voordeel is dat ik straks wanneer ik terugkom nog maar slechts 5 à 6 uur terug naar huis hoef te rijden. Dat is ook wel lekker!

Het is rond de 35 graden, erg warm wanneer ik vertrek. Ik heb gelukkig airco in de auto dus dan hou ik het prima vol. Met een koffiestop halverwege en nog een korte stop in Würzburg vermaak ik mij vandaag prima.

Würzburg ligt op de route en leek mij nog wel leuk. Helaas valt me dat erg tegen.

Paar oude gebouwen en een mooie brug dat is het dan ook wel.

Na een uur heb ik het dan ook wel gezien en rij ik weer verder. Uiteindelijk ben ik rond half zeven weer in Bodenheim.

Ik zet mijn campertje op een schaduwplek, draai mijn luifel uit, pak mijn stoel, eet een prima salade en geniet van de rust.

Ik lees weer eens een magazine en begin in mijn boek wat al 2 weken klaarligt om gelezen te worden. Heerlijk!

De volgende dag kan ik in de ochtend nog de laatste dingen gereed maken voor mijn reis naar Kazachstan. De rugzakken zijn gepakt en ik vertrek rond 13 uur richting het vliegveld.

Ik heb het parkeren afgekocht. Mijn campertje wordt bij de terminal opgehaald en geparkeerd en straks bij aankomst weer teruggebracht. Fijn!

Om 17.15 moet mijn vlucht vertrekken, maar doordat het vliegtuig al met vertraging arriveert vertrekken we volgens de mededelingen een half uur later. Hmmm...als dat maar goed komt want ik heb maar een uur en kwartier overstaptijd.

Helaas voordat we echt vertrekken zijn we twee uur verder. Pas 19.15 uut vliegen we weg. Dit komt onder meer doordat er nog een passagier uit het vliegtuig wilt omdat die zich niet goed voelt...🙈.

Uiteindelijk kom ik pas om 2 uur aan in Doha, Qatar. Mijn andere vlucht is natuurlijk al lang vertrokken.

Het duurt uren voordat geregeld is dat ik, inmiddels is het woensdag de 14e, weet dat ik vanavond weer mee kan op een vlucht, dat er een hotel is geregeld en dat er een taxi klaarstaat. Eenmaal buiten het vliegveld overvalt de hitte mij behoorlijk. In no time ben ik zeiknat door een soort natte deken die hier over de stad hangt. Heel anders dan bij ons!

Inmiddels heb ik ook begrepen dat een aantal dames, die ook meegaan op deze reis naar Kazachstan en vanaf Amsterdam zijn gevlogen, ook zijn gestrand in Doha. Helaas zitten zij 7 kilometer verderop in een hotel, dus maak ik pas morgenavond met hun kennis.

Ik lig om half zes lokale tijd (een uur later) in mijn bed. Tot 11 uur kan ik redelijk slapen, maar de airco, die ik absoluut nodig heb, maakt wel enorm veel lawaai.

Mijn kamer is luxe, lijkt wel een suite! Na een heerlijke douche ga ik naar de ontbijtzaal, of inmiddels het lunchbuffet 😂.

Ook dat ziet er top uit. Alles is wel netjes geregeld en iedereen is super vriendelijk en behulpzaam.

Als ik vraag of ik nog in de paar uurtjes die ik heb voor ik weer vertrek naar het vliegveld iets kan gaan doen in Doha, krijg ik het advies om naar een shoppingmall te gaan ivm de airco. Hmmm...daar heb ik niet veel zin in, dus ik blijf maar in het hotel.

Ik denk er nog even aan om heel stoer naar het tegenover het hotel gelegen park te wandelen, maar dat wordt niks. Te heet! 🥵 in de weersapp staat 41 graden, maar gevoelstemperatuur 53 graden!! Bizar.

Rond 16 uur vertrek ik weer richting het vliegveld, ruim op tijd. Dat is trouwens allemaal keurig geregeld 😃.

Het vliegveld an sich is al een hele ervaring van bonte kleuren, neon licht, luxe goederen en veel mensen. Ik vermaak mij hier nog wel even.

Iets later, bij de gate, kom ik de anderen tegen die ook naar Kazachstan gaan. We maken even kennis met elkaar.

Ik ben erg benieuwd hoe Kazachstan zal zijn en heb er zin in om dit land de komende weken te gaan ontdekken! Ik heb niet vaak internet dus mijn berichten zullen met enige vertraging verschijnen.

0 notes

Text

ok first

"Netanyahu is a shit head who love to dance with Hamas about the cease fire deal" he isn't danicng with hamas, he is killing children while refusing all deals to secure the release of hostages, as established by Israel's own press

and if he doesn't represent mainstream Israel.. WHY IS HE IN OFFICE? cause israel sure a shit can riot when it comes to protecting rapists.

"your “ withheld” movement leadership."

that's not me? I'm not part of that movement? are you responding to a different post?

"Palestinian leadership historical ties to Nazism?"

do you have a source? the nazis teamed up with brown people?

next you'll tell me the nazi's teamed up with Israel.. oh wait

The influence and strength of German Zionists obtained over time and until the Nazi regime was established, was concentrated in part to having the offices of the World Zionist Organization located in the German cities of Cologne and Berlin; more, its leaders were forceful and unique personalities. Researchers point out that after World War I, when the WZO transferred its headquarters to London its influence increased even more (Reinharz, 1996).

Early in the Zionist movement, the idea of a transfer of European Jews to British Mandate Palestine had wide currency. Specifically, Max Bodenheimer (1865 – 1940), a leading figure of German Zionism, and president of the Zionist Federation in Germany, declared in 1891 the need of the settlement of Eastern European Jews in Palestine for their protection and for their social rehabilitation (Reinharz, ibid). The very same idea also existed in the thought of Theodor Herzl (1860 – 1904), of the World Zionist Organization.

He was influential within the Zionist movement (Reinharz, ibid), and he is the person considered the founder of modern Zionism (Shoenman). Herzl shaped the idea that the Jews consisted primarily of a national community and not a religious one. Such a thought shaping the Jewish national identity, later contributed to the perception,and confrontation, of the Jewish question as a political matter, to be resolved strictly by political means: “The Jewish question, he maintained, is not social or religious. It is a national question. To solve it we must, above all, make it an international political issue …” (Shoenman, ibid). When Theodor Herzl made his political plans publicly known, regarding the attainment of Palestine as a Jewish Homeland, most German Zionists accepted the notion. The difference between the two men was that Bodenheimer didn’t intent to agitate the civil and political status of the German Jews (Reinharz, ibid).

Zionism like Nazism is the fruit of the tree of Volkism

both ideologies sought to remove jewish people's from Europe, and they chose ot make it Palestinian's problems

and TO THIS DAY Zionist's align with Hitler's ideologies

In another clip from the Bnei David Yeshiva published by Channel 13, Rabbi Giora Redler can be heard praising Hilter’s ideology during a lesson about the Holocaust.

“Let’s just start with whether Hitler was right or not,” he told students. “He was the most correct person there ever was, and was correct in every word he said… he was just on the wrong side.”

this isn't fringe shit, or cops pretending, or a nazis INFILTRATING, this is mainstream thought held by people in authority

you are embarrassingly ignorant

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Schwerer Unfall auf der B9 bei Bodenheim

Bodenheim, 06.01.2024 – Ein schwerer Verkehrsunfall ereignete sich am Dienstagnachmittag auf der B9 nahe der Anschlussstelle Bodenheim, bei dem drei Personen verletzt wurden. Der Unfall, der sich gegen 17:35 Uhr ereignete, führte zu erheblichen Verkehrsbehinderungen und einer Vollsperrung der Autobahn für insgesamt zwei Stunden. Nach Polizeiangaben fuhr eine Gruppe von Autofahrern, bestehend aus…

View On WordPress

0 notes