#big difference between corrupt military and literally every soldier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Me through most of Boom: Wow, this is a really solid dramatic episode.

Me when Moffat needlessly sprinkles in anti-faith sentiments without specifying that it’s blind faith in bad things that the Doctor doesn’t like, which makes it come off like the Doctor is just against religion generally:

#doctor who#dw critical#spoilers#dw spoilers#i get it edgelord you don��t care for religion. you don’t have to alienate religious members of the audience.#i at least appreciated that the doctor agreed with splice that gone and dead are different things and told her to keep the faith#but like. he immediately thereafter still tells mundy that he doesn’t like faith and spent the whole episode disparaging it.#which just feels so wrong for a show that’s supposed to be open minded about the beliefs and cultures all across the universe#i hate when writers gratuitously make the doctor take a hard and broad stance on something that he would NOT#reminds me of s8 when twelve suddenly hated all soldiers#as if some of his closest friends haven’t been soldiers? brigadier? benton and yates? sara?#big difference between corrupt military and literally every soldier#the same way there is a big difference between a corrupt religious organization or individuals who use religion as an excuse for cruelty#and like. ALL faith and the idea of having a faith that you live by whatsoever.#just because his comments were aimed at something corrupt doesn’t mean they weren’t WAY too sweeping as if he meant it on the whole#i definitely enjoyed the bulk of the episode but that just felt like it was done in bad faith and made me uncomfortable#and i just read moffat’s comment on the thoughts and prayers thing and UGH#i get why there are circumstances in which that can feel hollow — usually if it’s coming from a corporation that could actually do somethin#but can we not villainize all the normal people who genuinely mean that with love?#people who often CAN’T do anything but say prayers for you?#that IS a legitimate response and a legitimate action#someone can’t physically aid you but cares to take the time to talk to the God of the universe about you and your need and plead for you#don’t tell me that isn’t love or that it’s not really doing anything#sometimes that’s all you CAN do and it’s more than people give it credit for#blatant disregard and willful misunderstanding of faith like this just rub me wrong#it’s painting with a broad brush and it’s close minded#and yes i’m gonna post this. i’m feeling controversial.#my love/aggravation relationship with moffat continues#in the wise words of kira nerys. if you don’t have faith you can’t understand it and if you do then no explanation is necessary.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final Fantasy Type-0 review: Depression central

If there’s one Final Fantasy subseries whose fate gets me feeling down, it’s the Fabula Nova Crystallis series, a novel and ambitious concept based around various games and stories of different settings and casts of characters, but sharing common themes and mythos, putting them in different contexts in each. While a fascinating idea, it ran into nothing but trouble with each of its entries, with Final Fantasy XIII and its sequels being very divisive, to say the least, Final Fantasy Versus XIII running into an infamously extended development hell, only to finally emerge as Final Fantasy XV, now almost completely separate from its original concept, and the final big entry, Final Fantasy Type-0, vanishing until 5 years after its announcement in 2006, as a PSP exclusive that only came out in Japan, a rarity for the series when it comes to its higher profile spinoffs. Thankfully, in 2015, Type-0 got a remaster on the PS4, Xbox One, and PC, finally allowing other audiences to enjoy it. Was it worth the almost 10 year wait? Well, that’s something we’re about to find out now.

Story:

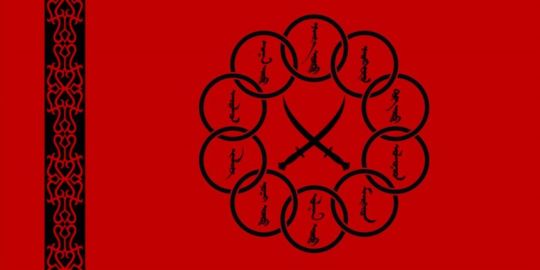

Final Fantasy Type-0 takes place on the world of Orience, divided into 4 great nations blessed with Crystals: the Dominion of Rubrum, a place for the study and teaching of magic granted by the Vermilion Bird crystal, the Kingdom of Concordia, a female led monarchy able to communicate and control monsters and, more importantly, dragons, and home to the Azure Dragon crystal, the Militesi Empire, a technologically advanced state able to produce great machines of war known as Magitek Armors, or MAs, through the power of their White Tiger crystal, and the Lorican Alliance, whose citizens are much larger and powerful than any other in Orience thanks to their more direct connection to their Black Tortoise crystal. Orience is, unfortunately, not a place of peace, with each of the 4 crystal states wishing to unite Orience under them, and making plenty of attempts to in the past. The motive behind this is the legend of the Agito, a messiah said to appear during Tempus Finis, an apocalyptic event prophesied in the somewhat dubious, yet widely believed, Nameless Tome, with every crystal state seeing it as their divine duty to create Agito, to the point of Rubrum training so called Agito cadets from its brightest and most magically adept citizens.

The story opens with yet another war being started in the year 842 by Milites, whose emperor has been deposed by the brilliant and ambitious Imperial Marshall Cid Aulstyne (Final Fantasy games have a tradition of having a character named Cid somewhere, and finally, he made it as main antagonist), who immediately sets out to attack Rubrum. What would otherwise be a “normal” invasion quickly turns disastrous for Rubrum when Milites unleashed a new device called a crystal jammer, which cuts Rubrum’s legionnaires from their connection to the crystal, rendering them helpless before the Militesi invaders. Even worse, Milites also deploys a l’cie, a human chosen by their nation’s crystal to become its direct servant, in exchange for immense power and near immortality, the use of which in warfare was mutually banned by each of the 4 nations. Just when Rubrum seems doomed, the mysterious Class Zero arrives, 12 cadets who are unaffected by the crystal jammer, raised by Rubrum’s even more mysterious archsorceress, Arecia Al-Rashia, who proceed to liberate the capital, Akademia. Now, with the addition of two promising but otherwise normal cadets, Machina Kunagiri and Rem Tokimiya, Class Zero becomes a vital part in Rubrum’s efforts to reclaim their lost land and defeat Milites, once and for all.

To just come out and say it, the story’s biggest weakness is the cast, or, more specifically, its use of the cast. While the playable cast alone is certainly large, at 14 characters, and the supporting cast only grows from there, almost nobody gets proper focus. The main 12 members of Class Zero, named after playing cards, consists of Ace, Deuce, Trey, Cater, Cinque, Sice, Seven, Eight, Nine, Jack, Queen, and King, and despite being the “proper” members of Class Zero, they all only have a few character traits each. Trey is a knowledgeable type that tends to ramble, Sice is an arrogant loner, Nine is a violent muscle head, Cinque is nice, but downright weird, and so on. While after a while they all grew on me, it’s still pretty unsatisfying, especially when Ace, the face of the game, gets neglected just as badly. The supporting cast gets it even worse, as outside of Arecia and Class Zero’s commanding officer, Kurasame, most of everyone else that’s notable either has minimal at best story presence, or doesn’t show up in the story, period, being relegated to sidequests. Ultimately, the most focused on characters are the two “normal” people in Class Zero, Machina and Rem, which kinda makes sense, giving a more grounded air compared to off how putting the others can be to begin with, but even they don’t work out quite well. While Rem is fine, she doesn’t do very much interesting with the time she gets, while Machina, on the other hand, is very, very unlikeable to the point of hurting the story, whether it be his own cold attitude or broodiness to put the usual RPG protagonist stereotype to shame, he ends up way more unsympathetic than near anyone else in the story, even most of the antagonists. While the cast overall is definitely flawed, though, they’re definitely entertaining at a lot of points, whether they come from the main cast, mostly Trey or Cinque, or from some of the side characters, mainly the extremely greedy Carla and, most memorably to me, the paranoid, bombing throwing Mutsuki.

Since the story doesn’t focus on the characters very much, the main focus is instead the war itself. While it definitely has a few twists and turns, especially starting in chapter 4, overall, the battles and events of the war aren’t the most interesting subject by itself. More interesting is the elements around the war. This is by far one of, if not the darkest game in the franchise, and it doesn’t shy away from showing just how messed up Orience is. Rubrum’s main strength comes in the form of its Agito cadets, meaning, teenagers, as young as 14, at that, and the tactics the military uses means they tend to die in droves. Even when it’s technically pragmatic, between magic proficiency peaking at teen years and decreasing with age, plus not having many other means to resistance, it’s still very uncomfortable, and keep in mind, this is what the good guys, or the relative ones, get up to. Milites, meanwhile, is all too happy to deploy superweapons, such as literal nukes, and its soldiers are disturbingly fanatic, being more than happy to massacre towns, and even refer to Class Zero as demons. Class Zero themselves were raised to be soliders, and feel almost nothing in battle, and Rubrum’s leadership are paranoid and petty, to the point of the military commander actively trying to get Class Zero killed out of pure spite. Eidolons, extremely powerful monsters able to be summoned by mages, demand the lives of their summoners, and there are outright suicide squads of cadets who are only meant to summon more powerful Eidolons. Additionally, a very important plot point is that the crystals automatically erase the memories of anyone who dies from everyone’s minds, to the point Rubrum’s citizens need to wear dog tags just so it can be confirmed they even existed after they die. While they try to justify it as a blessing from the crystals that allows people to move on and not be held back by the dead, all it’s done is completely desensitize Orience to death, and having characters casually talk about being informed of their friends or family dying, and not feeling a single thing, is pretty disturbing, especially when it’s named character involved. It does a very good job of showing how constant warring and lack of reverence for the dead has corrupted this world, even when many of the characters affected still remain sympathetic.

Unfortunately, the biggest flaw of the story to me is that there simply isn’t a lot of it to be found, at least in regards to the main story. While the game is comprised of 8 chapters, that’s more than a little inaccurate, as half of those consist of a short introduction and a singular mission, rather than the 2 or 3 missions in the rest of the chapters. The story only really gets moving in chapter 4, and even then, many important points aren’t addressed until chapter 8, which is a downright bizarre and sudden change of subject and tone compared to the rest of the game, to the point a second playthrough is required because of how many holes are left otherwise, and even then, it can be a bit difficult to figure out just what is going on. The biggest achievement of the writing, on the other hand, is the lore of the setting. Orience is a fascinating world, with a detailed history of each nation, plenty of info to find on the various characters, and examinations of the various enemies of the game, all stored in a book in the hub called the Rubicus. It’s also quite interesting seeing the perspective flip compared to Final Fantasy XIII; instead of l’cie “merely” being granted the use of magic, and quickly going through their usefulness, at least by their masters’ consideration, along with the main cast being comprised of them, l’cie in Type-0 are near demigods who often live hundreds of years, and are just as fearsome to the party as to everyone else, for instance. Overall, though, while there are certainly many problems with the writing, I can’t help but say it works quite well regardless. Even with the limited time for both the story itself and the characters, it still builds a cast worth rooting for throughout the horrible situations, and an effective atmosphere that’s quite good at leaving you feeling somber. Moments like the entirety of the opening chapter, showing the utter devastation inflicted on Akademia in a mere three hours, and the various costly, large battles are very effective moments, and the ending is easily one of the saddest endings I’ve seen in a video game, for all the right reasons. Even the final chapter, odd as it is, has a lot of cool revelations and setpieces to me, at least now that I comprehend it.

Gameplay:

Type-0 is an action RPG that has you control the 14 members of Class Zero on various missions, each one possessing a different weapon. Ace uses cards, Deuce uses a flute (I swear they aren’t all this weird), Trey uses a bow, Cater uses a magic infused pistol, Cinque uses a mace, Sice uses a scythe, Seven uses a whipblade, Eight fights with his bare hands, Nine uses a lance, Jack uses a katana, Queen uses a longsword, King uses dual revolvers, Machina uses dual rapiers, and Rem uses dual daggers. Each one possesses a vastly different moveset and playstyle, such as Cinque being slow, but strong and tanky, Sice encouraging an aggressive hit and run style of play, even getting stronger for the more enemies she defeats while taking minimal hits, Trey excelling at range to a much degree than anyone else, while being near helpless up close, and Deuce being more of a supporter, having great support abilities, while her attacks are fairly weird to get used to, though effective on their own once you understand them. Despite the huge amount of characters, they’re actually fairly well balanced, all of them having important strengths and weaknesses, and while some can definitely be better than others, with Trey in particular coming to mind, possessing absurd range and the ability to charge his shots, it’s never quite game breaking. You can have up to three characters in your party, though their AI isn’t exactly great. They can certainly distract enemies well, and will make sure to heal you if your HP gets low, they don’t tend to be aggressive, and are terrible at avoiding the attacks of most enemies more complex than your average imperial trooper, and are near guaranteed to die to bosses. Speaking of which, the main wrinkle is that, while it varies, overall, your characters are not very durable, and in fact take hits about as well as wet toilet paper when faced with most enemies. This is balanced by the sheer amount of people you have. One person dies on a mission, don’t sweat it, you’ve got 13 backups. Of course, this also encourages training them all up and learning to play them as well, which is complicated by only characters in the active party gaining experience. Leveling up, in addition to granting the usual stat boosts, also grants ability points, which you can use to purchase or upgrade command or passive abilities and moves.

While just attacking enemies normally is decently effective, it can put you in unnecessary danger, and while you do have items like potions you can use to restore your health quickly, the most efficient way to fight is to use breaksights and killsights. Every enemy has at least one attack that leaves them vulnerable for a short time either before or after using said attacking. Hitting them during this period will trigger a break, or, if their health is low enough, killsight. Breaksights take a good chunk of their health away and stuns them, giving you a chance to attack them freely, while killsights just kill them outright. This one mechanic adds a lot to the gameplay, encouraging you to learn enemy patterns and attacks to see when they are vulnerable, and getting the timing down can make otherwise fearsome enemies easy to take care of. Of course, some enemies won’t take this very well, and may counterattack or even go into berserk states after recovering from breaksights, so you still have to be careful. Every character has 4 commands: regular attacks with their weapons, 2 slots that can either hold abilities or offensive magic spells, and a defensive command, whether it be the cure spell to restore health, putting up a magic wall to nullify some attacks, or just flat out blocking, which, while still causing you to suffer damage, prevents being knocked down, letting you score breaksights easier than if you were to simply dodge. Magic can be upgraded by harvesting phantoma from dead enemies, coming in various types like red for fire magic, green for defensive magic, and purple for unique spells. While powerful, magic usually takes a large chunk out of your magic points, meaning it’s better to save it for more dire situations, though harvesting phantoma restores small amounts of MP. As for equipment, aside from weapons, you have access to accessories that do things such as increasing HP by a certain percentage, giving immunity to status effects, or raising defense, though everyone can only have 2 accessories at a time. You also have three different squad commands: triad maneuver, which simply causes the party to do 3 powerful, rapid attacks, Eidolon, which summons an Eidolon you can control for a short time, in exchange for KOing the character that summoned it, and Vermilion Bird, a powerful spell that, to actually become powerful, has to be upgraded using crystal shards, which, while fairly easy to get most of the time, aren’t very numerous.

Type-0 uses a mission system, throwing you into various locations to complete objectives, though it usually equates to to reach the end of the area and kill an enemy commander. Most locations are pretty linear, though they all have a few side areas you can go to, usually for more items. You get graded based on how fast you completed the mission, how much phantoma you harvested, and how many party members got KOed during the mission, with getting the best rank on all three categories getting you an S rank, which gives a bonus item. Beating each mission on a difficulty above easy also unlocks other bonuses, whether they be additional items up for purchase or unlocking new spells or Eidolons, or just flat giving you a rare item. Completing missions also gives you money, with more the higher the difficulty and the higher your rank. Speaking of difficulties, there are 4 of them: cadet, which is just easy mode, officer, normal mode, Agito mode, which is a hard mode that makes every enemy 30 levels higher than on cadet and officer, and Finis, which is only available after completing the game once, and is, just plain absurd. All enemies have their levels increased by 50, they’re in permanent rage mode, causing them to move twice as fast and hurt twice as much, and you’re restricted to only being able to use one person per mission. It’s not much worth the effort. Aside from completing missions, your main source of items, magic, and Eidolons is from completing special orders, optional objectives that can pop up in various areas. While there’s various generic, white orders that only give items at the end of the mission for doing stuff like not getting hit for 30 seconds or not using magic for a few minutes, there are also specific, red ones with more specific objectives like taking out certain enemies, that give out better rewards. The main problem with accepting them is that, if you fail to complete them, you risk instant being killed over it, though you can avoid it you’re fast enough, as it’s delivered through portals on the ground.

In between missions, you’re allowed to explore Akademia, chatting with NPCs or party members, or engaging in “free time events” which are either conversations with random people, or cutscenes that tend to have much more interesting information. You only have a limited amount of hours until the next story mission starts, with each event taking two hours away, though time doesn’t pass just running around and talking to people without events. While a neat concept that could easily be like Persona, in practice, it doesn’t add much. While you can get some interesting information at times, and doing events also gives you items, it’s not very in depth otherwise. Even the sidequests with the more prominent side characters just consist doing their events whenever they’re available and doing a sidequest for them, eventually getting admittedly very good bonuses at the end of their little storylines. The other thing you can do with your free time is go out into the world map, where you can visit extremely small towns, get into random encounters, visit dungeons, and... not much else. While the world map isn’t tiny, there’s just not much to find. While there’s many towns, they are, again, tiny, only consisting of a single small area with a shop or two, a sidequest, and a little unofficial side quest to get a l’cie stone, which can be traded into a certain NPC to unlock lore entries in the Rubicus. There’s just not much of interest, and you’re very heavily restricted in where you’re allowed to even go on the world map, only being able to go to areas officially reclaimed by Rubrum, or that are the destination of the current story mission. Only in chapter 7 do you finally get some kind of freedom, to the point of being able to gain an airship to allow easy traversal of the world. Plus, most dungeons aren’t even meant to be explored on a first playthrough, with only about one or two being reasonable at that point, not that there’s even much to find besides l’cie stones and a chance at a rare item, emphasis on chance, since they’re always in a specific chest at the end that can only be opened once without reloading your save, and the chance of getting the most valuable item from them is rather low.

As for other activities, you can train in the arena, for downright piddly gains, or take on sidequests, most of which just contain of going out and defeating a certain amount of specific enemies, giving over items, and so forth. Most rewards aren’t great, but a few, namely from the more notable characters like the leaders of Rubrum, Kurasame, and Arecia, give very notable rewards. Sidequests don’t take time to do, but often require you to leave Akademia, meaning you need to weigh the time lost going out to do the quests against the time you could use doing events, which is difficult when you don’t know just what rewards either give out. When it comes mission time, though, you gotta venture out on the world map to your next destination. Speaking of the world map, along with the regular missions, there are also RTS style missions, where you, controlling a party member on the world map, help the dominion army reclaim forts and towns by taking out enemies and having units generated by controlled areas weaken said areas until you can invade them in a regular mission style. Instead of being graded on phantoma harvested, you’re instead graded on objectives completed, as occasionally you’ll get orders to do stuff like defend a fort for a specific amount of time or taking out a large enemy. While technically optional, you get bonuses for completing them beyond mission grade, such as access to “hero units” and direct control of certain areas. There’s a decent amount of these missions in the game, and they do make for an interest change of pace, but they aren’t much notable. You’re even allowed to skip participating in them, though obviously you miss out on rewards.

The highlights of the game are, rather sensibly, the end of chapter missions. Not only are they much longer than typical missions, they have much more unique settings, and, of course, bosses. This game has some very enjoyable, if difficult, bosses, ranging from the giant mech Brionac that is more than capable of wiping you out in a single attack, to the highly mobile mech of Qator Bashtar, Cid’s second in command, to several fights with the near invincible Gilgamesh (another recurring character in the series). My personal favorite is the boss of chapter 5, the dragon Shinryu, which is also all too happy to instantly kill you with most of its attacks, even more so than Brionac, and spend most of the fight enveloped in the darkness surrounding the arena you’re in, only being visible by the lights of its glowing red eyes. It makes for an amazing setpiece, and losing to it is almost more enjoyable than winning simply due to the failsafe implemented since the devs expected most players to lost, the details of which I simply cannot spoil. Finally, on a second playthrough, two new types of missions are available for you: expert trials, and Code Crimson missions. Expert trials are optional missions you can do during your free time, which you’ll likely have a lot of since events you see on a previous playthrough can be viewed again at no time cost on repeat playthroughs. While technically available in the first playthrough as well, they are way too difficult for the average player, i.e who isn’t insane like me. Code Crimson missions, on the other hand, are replacements for the end of chapter missions, consisting of you going off to do other stuff. While an interesting concept, in practice, they aren’t anything special, especially when they’re replacing the most interesting parts of the game, and they barely give any more story context either. The chapter 7 mission is the one exception, being very short, but an interesting concept and adding a bit more to the story. Plus, completing them all on one playthrough unlocks an interesting alternate ending, so that alone makes them worth a go.

As for the hardest challenges to be found, they’re a bit lacking. Aside from the regular optional dungeons, there’s one notable bonus dungeon and two notable superbosses. The bonus dungeon is the Tower of Agito, which can only be reached by airship, which consists of 5 floors where you need to fight 100 specific enemies, such as tonberries and behemoths, with plenty of chests to open in between, ending off on an extremely disappointing end boss that is just a Malboro that happens to be massive. While it certain sounds difficult, and pretty much everything is capable of one shotting you, once you get into a good pattern, it’s really just boring. Most of the time, they just spawn so slowly, and while after a while more of them come out at a time, it takes about an hour and a half at best to get through even if you’re otherwise efficient. As for the superbosses, there’s Nox Suzaku, only available in a second playthrough and onward, who has a chance of appearing whenever you harvest phantoma, stealing everything you try to harvest until it decides to go away. Aside from making it go away on its own, you can beat it up, which is quite a doozy. Instead of fighting you directly, it summons phantoms of various enemies to fight you, and while you could just defeat them all, this doesn’t do anything to Nox itself. Instead, you have to let the enemies defeat you, causing Nox to appear for a short time, allowing you to attack it until it retreats. Rinse and repeat, it’s not that difficult, and the rewards aren’t that great, so the main reason to beat it up is just to make it go away, because it stealing your phantoma is extremely annoying, especially when it can show up during missions, since you can’t just leave to fight it, and it’s entirely possible for it to flat make it impossible to get an S rank on that mission it decides it doesn’t want to leave. Not exactly a fun mechanic. The other superboss is, per tradition, Gilgamesh, in a stronger form than in the story. He only shows up on a third playthrough, at a few different locations on the world map, in the form of a portal. Entering said portals causes him to randomly select one of your characters to challenge. If you win, you get that character’s ultimate weapon, but if he wins, he steals your character’s current weapon. The ultimate weapons are kinda underwhelming, especially considering you may well have everything else done after a second playthrough, and it’s annoying getting specific people picked, but it’s actually a fun and fair fight, if easy to figure out.

Overall, Type-0 has some of the tightest gameplay among all the Final Fantasy spinoffs, and is the main thing that holds it together. It has a fast, hectic pace to it, interesting enemies to tackle, and a wide variety of people to try out. Really, the main criticism I have is the actual missions you have with which to try them out. The other main story missions aren’t much to look at, and same goes for the expert trials and Code Crimson missions. I’m sure this is at least partially due to originating on the PSP, and having to deal with its limitations, something that’s about become a theme in this review. Overall, though, it’s still more than satisfactory.

Graphics:

The visuals of Type-0 are a very mixed big, unfortunately leaning more towards negative. More than anything else, they make it very apparent that Type-0 was originally a PSP game. While the members of Class Zero themselves have decent looking models, if rather unemotive, everyone else, except a few important characters like Arecia, are much lower quality, especially the faces. Here’s a comparison between Ace and Carla.

The textures don’t fare much better, looking very blatantly stretched and blurry, especially on the world map, where bridges are just one long, hideous texture. Most locations outside of, again, the end of chapter missions don’t look anything special, and so many areas are just reused over and over. You go into a town, it’ll look like every other town, at least of that region. You invade a fort, it’ll look like every other fort. Repeat for almost every mission in the game. Thankfully, the big story missions look quite impressive and creative, my favorites being chapter 5′s, taking place on frozen clouds that end up near breathtaking, and especially the setting of the very final mission, which is, to avoid anything too specific, downright insane, in a good way. Another positive are the enemy designs, more specifically, the actual monsters, with enemies such as bombs and flans resembling their earlier FF designs much more than most modern entries. Unfortunately, there’s just one problem: the actual variety of enemy designs is rather lacking, with the majority of enemies being slight alterations or palette swaps. It’s a more minor point than most, but still something. The original enemy designs are quite inventive though, and overall, this is a game that excels more in general design than actual fidelity, like the spiraling Concordian capital surrounded by a sea of clouds.

Sound:

The music of Type-0 is plain great, as is usual for the series. The boss themes especially are fantastic, along with the main theme, The Beginning of the End. It also sounds quite distinctive compared to most of the rest of the series, having a greater focus on metal, fitting the more modern aesthetic. The English voice acting, on the other hand, isn’t quite great. It’s pretty obvious the dub was a rush job, considering Type-0 lacked the simultaneous localization process of the main series games, resulting in it being very lackluster overall. There are some notable voice acting names in it, like Cristina Vee as Cinque, Bryce Papenbrook as Machina, Danielle Judovits as Carla, Cassandra Lee as Mutsuki, and even Matthew Mercer as Trey, and they all do good jobs, but the rest of the cast varies, especially Class Zero itself. Ironically enough, the side characters tend to have much more solid performances, with special props going to Steve Blum as Cid, giving a very menacing perfomance, as well as other characters like Aria, Class Zero’s orderly, and Kazusa, the resident mad scientist. Corri English as Sice and Heather Hogan Watson as Queen also fair quite well. Beyond that though, the performances can be rather forced, like Nine and Cater, or just weak overall, like Rem and Deuce. This is not helped by the normal, in game cutscenes themselves, with their structure causing many long, awkward pauses nearly every sentence. It does, however, improve as the game goes on, to the point of the final cutscenes not being hurt by it near at all.

Conclusion:

Overall, this is a solid recommended by me. Even with the weakness of elements like the graphics and the short, underdeveloped story, the core gameplay just holds up that well, and there’s quite a bit to enjoy in the weaker elements even beyond that. Overall, this is one of my favorite Final Fantasy spinoffs, and the fact that it will most likely never get a sequel due to the departure of its director, Hajime Tabata, makes me very sad. With that unneeded note, this shall be the last of the Final Fantasy spinoffs I play in some time. The next time the name Final Fantasy pops up as the subject of one of my reviews, it shall be about the main series. Till next time.

-Scout

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

https://ift.tt/3yIWIFS #

Warning: This article contains SPOILERS for Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings.

Marvel’s latest, Shang-Chi & the Legend of the Ten Rings, has dozens of MCU Easter eggs hidden throughout; here they are broken down. Created as the “Master of Kung Fu,” Shang-Chi is a somewhat unusual character in the Marvel Universe in that he traditionally doesn’t possess any superpowers at all. Rather, he’s simply a martial artist so skilled he can go toe-to-toe with gods and monsters. The MCU’s Shang-Chi is very different from the comics, where he’s not connected to the Mandarin at all, but rather to another crime lord, Fu Manchu, who Marvel don’t have the rights to – and probably wouldn’t use if they could, because he’s a problematic racist trope.

Marvel has toyed with introducing Shang-Chi to the big screen for over 20 years. He was one of the 10 properties Marvel originally planned to build the MCU upon, although he was dropped when the studio reacquired the film rights to Iron Man and headed in a very different direction. Still, for all that’s the case, there’s a sense in which Shang-Chi answers mysteries that have been there in the MCU from the beginning; it reveals the truth about the Ten Rings, a terrorist organization from the Iron Man films, and even features the real Mandarin after the fake version in Iron Man 3.

Related: Shang-Chi 2 News & Updates: Everything We Know

Like all MCU films, Shang-Chi is packed with Easter eggs and cameos. Some of them are easy to spot, others are a lot more subtle – here’s every Marvel Easter egg and notable pop culture reference in the movie.

Let’s start with one of the more amusing, tongue-in-cheek nods – in one scene Katy remembers her first meeting with Shang-Chi, when he expressed a vocal objection to being considered a Korean. This is a nod to Kim’s Convenience, where Simu Liu played a Korean character named Jung. Liu has suggested this was something of a challenge; as he observed on Twitter back in 2016, “everyone is Korean except for me, and I’m trying very hard to fit in.“

Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame were the two most spectacular events in the MCU; in the first film, the Mad Titan Thanos snapped his fingers and erased half the lives in the universe, and in the second, the Avengers brought everyone back. The five-year period between these two events has been dubbed “the Blip” in the MCU, and the Marvel Disney+ TV series have been exploring the chaos of the aftermath, with WandaVision focusing on the personal cost and The Falcon & the Winter Soldier on the geopolitical issues arising from the Blip. The Blip is referenced twice in Shang-Chi, once when Katy points out they live in a world where half the people on Earth can disappear. It’s referenced again more subtly on a poster outside her home. “Post-Blip anxiety? You are not alone,” the poster declares, suggesting there’s understandably still a lot of trauma in the world.

The Ten Rings have been an established part of the MCU from the beginning, as the terrorist cell that captured Tony Stark in Iron Man was one of them. They were fleshed out as the trilogy continued, appearing numerous times in tie-ins such as the Iron Man 3 Prelude comic book that revealed War Machine was dealing with a particularly nasty terrorist plot on the other side of the world when the Chitauri invaded New York in The Avengers in 2012, explaining why he didn’t help out. They were subverted in Iron Man 3, but Shang-Chi serves as something of a course-correction on that, playing them straight and liberally using the logo.

Related: Shang-Chi Cast & Character Guide: All New & Returning MCU Actors

The Ten Rings catch up with Shang-Chi on the bus, and their initial confrontation is observed by a familiar face. Played by Zach Cherry in Shang-Chi‘s cameo, the vlogger Klev first appeared in Spider-Man: Homecoming, when he asked Spider-Man to perform stunts as he filmed them, and he returns in Shang-Chi when a fight breaks out on his bus. “Yo, whaddup y’all, it’s your boy Klev, coming at you live on the bus,” he declares, before stating his intention to rate Shang-Chi’s martial arts as he apparently practiced when he was younger. It’s really something of a shame Klev doesn’t appear more, because he gets some great comedic lines in this welcome cameo.

In the comics, Razor Fist is a low-level thug who typically works for more prominent villains – including the likes of the Mandarin and the Hood. He’s gone head-to-head with a wide range of superheroes, such as Shang-Chi, Wolverine, and Deadpool, but – although he was initially treated as a dangerous threat – he’s increasingly been seen as light comic relief compared to more deadly foes. Shang-Chi‘s version is a little different, with only one of his hands replaced by a razor-stump, which is frankly a lot more practical; the comic book character has often been mocked with questions about just how he gets dressed when both his hands are blades. Amusingly, it’s soon clear the character still likes to call himself “Razor Fist,” with that name sprayed on his car.

Shang-Chi is heavily inspired by Jackie Chan and Chinese wuxia films, and it wears its love of these martial movies on its sleeve – literally. The opening bus fight between Shang-Chi and members of the Ten Rings features a tremendous moment in which the hero uses his jacket as a weapon, a move that will be familiar to any Jackie Chan fans. All in all, Shang-Chi boasts some of the best fight choreography in the entire MCU to date, appropriate for the character who – in the comics – is called the Master of Kung Fu.

Shang-Chi’s origin story has completely changed from the comics, but certain elements of it still link to his first appearance in Special Marvel Edition #15. There, he was brought up by the crime lord Fu Manchu as an assassin but believing his father to be a humanitarian who only killed evil people. He did indeed complete his first mission for his father – before being told the truth about Fu Manchu being evil, and going rogue. The similarities end there, though, because Shang-Chi’s first mission in the MCU was a lot more personal.

Related: Shang-Chi Ending Explained: 6 Biggest Questions, Answered

Shang-Chi seeks out his sister Xialing at the Golden Daggers Club in Macau, unaware it is a superhuman fight club or that Xialing owns it. In the comics, the Golden Daggers were a criminal organization led by Shang-Chi’s sister (named Leiko in the comics), who established them as a rival empire to her father’s. Shang-Chi originally thought they were working for Fu Manchu, but gradually learned he was caught between two rival criminal gangs.

Keep a close eye on the Golden Daggers fight club, because it includes a number of cool Easter eggs. One particularly interesting fight is between an Extremis-powered soldier from Iron Man 3 and a Black Widow, giving a sense of the superhuman scraps that take place there. The Black Widow is a character named Helen, played by stunt performer (and World Wushu Champion) Jade Xu, and it seems she has found her way to Macau after being freed from the Red Room’s control in Black Widow. The Extremis soldier is particularly curious, as they were all supposedly killed, so it’s possible someone has begun experimenting with Extremis again.

Of course, the star attraction of the Golden Daggers is the Abomination, a classic Hulk villain who’s changed substantially since The Incredible Hulk. Tim Roth’s Emil Blonsky was exposed to Gamma radiation in The Incredible Hulk, transforming him into a monster who rampaged through Harlem, but according to the Marvel One-Shot The Consultant he was viewed as a hero by the military, with the World Security Council even wanting him to get involved with the Avengers Initiative. SHIELD knew better, and manipulated events so as to ensure the Abomination was dropped from their potential Avengers roster, and (with the exception of one episode of Agents of SHIELD), he hasn’t been seen or referenced since – until now. The Abomination now sports a much more comic-book-accurate appearance, clearly having mutated significantly over the last decade. It’s difficult to say for certain, but when he is teleported away he appears to be going to the Raft, a prison for superhumans introduced in Captain America: Civil War. Blonsky will return in the She-Hulk Disney+ TV series.

The Abomination’s opponent in the Golden Daggers is Wong, one of the more prominent members of the Masters of the Mystic Arts. It’s unclear why Wong is at a fight club, but he appears to be a regular and has a friendly relationship with the Abomination. Wong is playing a major role in Phase 4, likely because he’s operating from Kamar-Taj, meaning he’s responsible for overseeing mystical events across the entire world – while Doctor Strange appears to have become the guardian of the Sanctum Sanctorum in New York, thus being geographically limited. Wong returns in a delightful cameo in Shang-Chi‘s mid-credits scene.

Related: Shang-Chi End-Credits Scenes Set Up 6 MCU Movies & Shows

It’s easy to miss, but the Madripoor flag is painted on the walls in Xialing’s fight club. In the comics, Madripoor is basically the Mos Eisley Cantina of the Marvel Universe, a notoriously corrupt and crime-ridden island nation. It made its MCU debut in The Falcon & the Winter Soldier when the titular heroes traveled to Madripoor and learned Sokovia Accord fugitive Sharon Carter had made her home there. Interestingly, Marvel set up a promotional Welcome to Madripoor website that did initially feature Ten Rings Easter eggs; they were swiftly removed.

In the comics, Li Ching-Lin was an MI6 agent who secretly worked for Shang-Chi’s father, Fu Manchu. A skilled and brutal warrior, he was anointed Death-Dealer by Fu Manchu and became one of his most prominent henchmen, clashing with Shang-Chi on countless occasions. The MCU has completely reinvented Death-Dealer, who is apparently a key member of the Ten Rings, responsible for training them. He was a harsh mentor to Shang-Chi but did not train his sister Xialing, as she was a girl and women were not allowed to be members of the Ten Rings.

A captured Shang-Chi and his friends are taken to Wenwu’s fortress in China’s mountainous Hunan province. This is based on Fu Manchu’s home in Special Marvel Edition #15, which was indeed situated in Hunan, and it has returned in recent Shang-Chi comics. Recent Marvel comics have rewritten Shang-Chi’s history, naming this as the House of the Deadly Hand, but these retcons were carried out while the film was in production so are unlikely to be important at this stage.

Shang-Chi introduces viewers to Wenwu, the true leader of the Ten Rings, whose identity was appropriated by actor Trevor Slattery in Iron Man 3 when he dreamed up the character of the Mandarin. Slattery’s Mandarin was a composite of a hundred legends, but Wenwu is the real deal, a complex figure who has been tortured by grief over the loss of his wife years ago. The film spends a surprising amount of time explaining the Mandarin twist, with Wenwu even discussing it at length, mocking the citizens of the United States for being so terrified of “the Mandarin” – amused so many people were afraid of him.

Related: Shang-Chi Confirms The MCU Timeline Is Completely Broken Post-Endgame

According to Wenwu, he has been known by many names over the millennia; the Warrior King, Master Khan, and the Most Dangerous Man on Earth. The second of these titles is the most important, because in the comics “Master Khan” is indeed an alias of the Mandarin. In the comics, it denoted a connection between the Mandarin and Genghis Khan, but in the MCU the timeline may instead hint Genghis Khan was himself Wenwu.

Down-on-his-luck actor Trevor Slattery returns from Iron Man 3, once again played by Ben Kingsley. As seen in the Marvel One-Shot All Hail the King, Slattery was broken out of prison by the Ten Rings, with Wenwu intending to kill him for the audacity of appropriating his identity in this way. Slattery apparently forestalled the execution by launching into a terrified performance of Macbeth, and was thus spared death, instead becoming Wenwu’s jester. Trevor plays a surprisingly important role in Shang-Chi, helping the heroes get to the mystical realm of Ta Lo before Wenwu, and he even survives the battle with the Dweller-In-Darkness in hilarious fashion.

Ta Lo exists in the comics, where it is a small pocket dimension numbered among the so-called “God Realms.” This is a seriously deep cut into Marvel lore, with Ta Lo only appearing in a single issue – Thor #301 – and actually explored more in Marvel handbooks than in the comics themselves. According to these handbooks, there are five interdimensional nexuses that lead to Ta Lo, each found at the foot of a sacred mountain. It is home to the Xian, a race akin to the Asgardians who have inspired China’s Taoist gods; Shang-Chi wisely ditches this idea, aware it would be culturally insensitive.

As noted by Mateo, Wenwu claims the gate to Ta Lo opens only on Qingming Jie, allowing viewers to precisely date Shang-Chi in the MCU timeline. Because this happens after Avengers: Endgame, Shang-Chi must be in 2024, and this Chinese festival day will happen on April 4 that year. The events probably take place from approx. March 29 through to April 5, which means the timeline for MCU content post-Endgame currently looks something like this:

Loki

Marvel’s What If…?

WandaVision

Shang-Chi & the Legend of the Ten Rings

The Falcon & the Winter Soldier

Spider-Man: Far From Home

Shang-Chi features a wealth of mythical Chinese creatures, including:

The unicorn-like qílín, the horned creature with the body of a deer and the tail of an ox, which lives in places of peace and serenity and only appears in the real world to presage the emergence of a great, benevolent ruler. Ta Lo is presumably supposed to be the origin of the qílín.

There’s also a glimpse of the fènghuáng, an immortal bird sometimes incorrectly called the Chinese Phoenix, another auspicious creature. Interestingly, both the qílín and the fènghuáng are symbols of balance, incorporating both the male and female elements; balance is very much the theme of Shang-Chi, so the presence of these two mythological animals is very appropriate indeed. Both the qílín and the fènghuáng are associated with Ta Lo in the comics.

The beautiful húlijīng, a mythical nine-tailed fox that has absorbed the natural energy of the world over many years.

There are also shíshī, the Chinese guardian lions, sometimes called foo dogs, who assist the residents of Ta Lo in their battle against the Ten Rings.

The longma is a legendary winged horse with dragon scales, another creature whose presence is symbolic of the rise of a sage ruler.

The most prominent creature in Shang-Chi is Trevor Slattery’s Maurice, a dìjiāng – often seen to represent cosmic confusion. It makes sense a dijiang would associate itself with Trevor.

Related: Every Marvel Cinematic Universe Movie, Ranked Worst To Best (Including Shang-Chi)

Dragons do exist in Marvel Comics, the most famous being the alien Makluan dragon creature Fin Fang Foom; however, the Great Protector seen in Shang-Chi is nothing like a Makluan. Rather, the creature is based on Chinese mythology, where dragons – or lóng – serve as protectors rather than destroyers, and the dragon has become a symbol of status and power. Shang-Chi is likely set in the year 2024, which seems amusingly appropriate, given that is the Year of the Dragon in the Chinese Zodiac.

The Dweller-in-Darkness is lifted from the comics, although he’s been adapted quite significantly. In the comics, he is one of the universe’s Fear Lords, beings who gain sustenance from the fear of creatures on other planes, and he considers the more famous comic book Fear Lord, Nightmare, to be his cousin. Dweller-in-Darkness was a terrible threat to the Earth millennia ago, in the days of ancient Atlantis, and derived great pleasure from the conflict between the Eternals and the Deviants that led to the sinking of that continent. He grew too powerful, however, and caught the attention of the Atlantean sorceress Zhered-Na, who cast the Dweller-In-Darkness into an eternal slumber from which he only awoke in the modern era – only to find himself contested now by Doctor Strange. The MCU’s Dweller-in-Darkness has been changed a lot, and is now some sort of demon, blended with the Chinese myths of the Wangliang, a malevolent spirit in Chinese folklore. The Soul Eaters serving the Dweller-in-Darkness in Shang-Chi do exist in the comics, but they too have been heavily modified. In the comics, a Soul-Eater attaches itself to a victim and preys upon them for a lengthy period of time, consuming their soul little by little. The process of soul extraction is vastly accelerated in Shang-Chi.

Shang-Chi‘s post-credits scene reveals the superhero holo-conferences conducted by Black Widow during the Blip (as seen in Avengers: Endgame) are still ongoing. This is the first time there’s been a hint Earth’s protectors are still organized in Phase 4, and it’s likely Wong only called in the people he wanted involved in discussions about Shang-Chi’s Ten Rings; Captain Marvel, with her knowledge of alien worlds and civilizations, and the scientific mind of Bruce Banner. Neither has ever seen anything like this before, with Banner confirming they’re not Vibranium.

Something has clearly happened to Bruce Banner between Avengers: Endgame and the events of Shang-Chi; the last time he was seen, the Banner and Hulk personas had combined into “Professor Hulk,” and he was stuck in that form permanently, but now he’s back as a human being. This will probably either be explained by the upcoming She-Hulk Disney+ TV series, or else it will be setup for it, explaining why Banner’s blood is used in a transfusion for his cousin Jennifer Walters. His right arm is still in a sling, meaning the injury he sustained when he used the Infinity Gauntlet hasn’t been healed. It seems Marvel are honoring the Russo brothers’ wishes for the Hulk to have a permanent injury; “It’s permanent damage,” Joe Russo explained in one interview. “The same way it was permanent damage with Thanos. It’s irreversible damage.“

Related: Every Upcoming Marvel Movie Release Date (2021 To 2023)

Wong references Kamar-Taj during the holo-conference, revealing the Masters of the Mystic Arts were able to detect whatever “signal” was emitted from the Ten Rings at the moment control of them passed over to Shang-Chi. This is pretty impressive, given Ta Lo was described as being in an entirely different universe, meaning the energy surge generated by them must have traveled through the entire Multiverse.

The MCU has always loved to incorporate classic music into its films, and the Eagles’ “Hotel California” crops up throughout Shang-Chi. The theme of the song works perfectly for the movie, as Shang-Chi has attempted to “check out” of the family drama, but he can never leave. The mid-credits scene of Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings puts a more positive spin on this, though, because now Shang-Chi has checked in to the world of superheroes, and his life will never be the same again.

More: Where Was Doctor Strange During Shang-Chi?

#marvel #avengers #marvelcomics #spiderman #mcu #ironman #comics #captainamerica #thor #avengersendgame #marvelstudios #xmen #dc #marveluniverse #art #cosplay #tomholland #hulk #disney #comicbooks #dccomics #peterparker #tonystark #blackwidow #marvellegends #endgame #deadpool #marvelcinematicuniverse #loki #bhfyp

The post Every MCU Easter Egg In Shang-Chi And The Legend Of The Ten Rings appeared first on undertheinfluencerd.net.

#entertainment, screenrant #tumblr #aesthetic #like #love #tumblrgirl #follow #instagram #photography #instagood #likeforlikes #s #likes #art #cute #o #girl #followforfollowback #a #tumblrboy #grunge #fashion #photooftheday #tiktok #l #photo #sad #k #frases #f #bhfyp

0 notes

Video

youtube

Trump BOMBSHELL Hitting Headlines Is Legit

COMMENTARY:

You guys continue to beat this dead horse that Hillary was a terrible candidate. To the degree that's axiomatic to your analysis, to that degree you continue to mainline the Conservative/Trump Kool Aide. She was the target of 26 years of disinformation from the moment she and Bill showed up at the White House.

You were 10 years old when they came to Washington and you have no historical context as to what confronted them, which was the full-throated roll out of the Republican Noise Machine unprecedented in my experience.

I was friends with Ray Price, Nixon's speech writer, from 1973, literally the day Butterfield revealed the existence of the taping system, until Reagan's White House put me on a black list in 1981. Watergate didn't begin to reach the sustained level of hostility in DC except in the experience of political activists like Pat Buchanan, as the Poster Boy for the Plumbers/political activists, in the White House. The Clinton's ran into a buzzsaw that was several magnitudes greater than that period, which was far more characterized by the trailing edge of the emotional wave from the anti-war movement, nationally. Once the draft ended, not even Kent State could create the social agitation we are experiencing, currently, and the animus against the Clintons in 1993, when you were 10 years old, was a distinct and separate gestalt arising from the zeitgeist and focused entirely on the Clintons which found its climax phase in the run-up to 1916.

And you have totally bought in to it, even now. So, the Republican Noise Machine is a permanent resident in your unconsciousness, a phenomena apparent in Cenk and Anna and all you political gad flies with no real agenda. It reflects what I call the Oliver Stone version of Vietnam that corrupts your political calculus in ways that made the election of Trump possible and his re-election a dangerous probability. In effect, all you Bernie Brothers are useful idiots for the Trump agenda and have been since Reagan was inaugurated since 1981. When critics say there isn't a dime's worth of difference between Conservatives and the DLC, there is a great deal of truth to it and the Oliver Stone version of Vietnam is a big part of the reason why.

When I got back from Vietnam in 1971, the Republican generations of draft dodgers were the gate keepers for Fortune 500 organizations and H. Ross Perot was one of the few CEO's actively seeking out combat veterans (mostly Navy vets) for EDS, He was part of the National Alliance of Business Men's hire veteran agenda that encouraged executives to devote a year to the problem. Most of these people were Democrats at the executive level, such as John DeLorean, while the pro-war Republican executives tended to avoid any association with Viet vet "losers". I was put on a Reagan White House black list for being a Vietnam "loser"" and for doing business with the Soviet Union which had been a Nixon diplomatic priority: Charles Z. Wick told me explicitly and personally that Reagan would never be associated with Vietnam "losers".

The active military was content to let the draftees get the blame for how Vietnam got fucked up while they engineered the All Volunteer Military as basically a CYA for their moral collapse after Tet '68. Since you weren't even born yet, it is useful to understand that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial didn't get traction until Carter became President and the Iran crises reminded everybody concerned that, if they wanted cannon fodder for the next war, they needed to quite fucking the veterans who fought the last war. And this delay was just one manifestation of the Oliver Stone version of Vietnam that continues to run up and down the chain of command in the military and the Republican Conservatives.

And Trump's alleged attitude that the soldiers buried in Arlington and elsewhere are "losers" and "suckers" is perfectly consistent with the pro-war right wing draft dodgers of the 60s on campus in my experience. This attitude in business majors of the times is likewise consistent with the Henry Cabot Lodge isolationist movement that stalled the League of Nations and is represented by John Bolton's commitment to blowing up the Atlantic Charter within the parameters of Bill Kristol's and Robert Kagan's Project for the New American Century which was the neo-imperialistic pre-emptive war justification for the invasion of Iraq.

And the suicide rate among combat veterans trying to re-enter the civilian economy is driven by Trump's attitude towards the military he acquired along with his bone spurs. Most businessmen ("men" being the operative root) who have had other priorities than military service consider a military career as a form of summer camp in contrast to the "real job" of a corporate career. Their attitude in 1971 was that, if you were too stupid to submit to military service, you were too stupid to put on their payroll. And that sttitude persists.

And your discussion regarding the significance of the Atlantic disclosures reflects exactly the Oliver Stone version of Vietnam, The fact is, your calculus is pretty accurate: as you say, the fact that Trump disrespect of McCain's epic heroism as a POW didn't end his run for the White House tells the tale of the popular distortion of what real politic diplomacy actually means as the critical path of our national security and destiny.

I've been trying to get the military to pay attention to the danger of the Conservative agenda associated with Jeffrey Goldberg's bombshell report about Trump since 1981, but, as I say, they are as wedded to the Oliver Stone version of Vietnam as you are. You and Cenk and all the other "both sider" gad flies need to drop your conceit that you represent objective journalism and go in with both feet to humiliate Trump and Moscow Mitch at the polls in November. The fact that you continue to believe that Hillary Clinton was a terrible candidate is a measure of the degree to which you have been an unwitting agent of the Free Market Fascist agenda Trump has inherited from the political activism of the Lincoln Project before 2016.

And I'll give you something to work with: I know for a fact that the reason why President Xi won't do a deal with Trump is because Peter Navarro's 7 Verticle Reforms is based on doubling down on the Military Industrial Complex of 1947 when an American businessman ("man" being the operative root) could get a blow job in Berlin for a loaf of bread. The entire Pacific Rim is content to wait for President Sleepy Joe Biden to present a trade deal based on the Green New Deal with based on the infrastructure necessary to sustain a permanent moon colony over a 100 year trajectory.

If either Carter of GHW Bush had been re-elected, we would have had a NASA-Soyez base on the moon by 2001, just like the movie because the Nixon-Moynihan-Carter Affirmative Action was the precursor to the Green New Deal. AOC, as a community organizer, economics major and beneficiary of tipping as the most effective expression of Trickle Down Economcs, intuited what she has come to call the Green New Deal and the only thing standing in the way of this up-grade to the Free Enterprise economic ecology of the America British constitutional capitalism is Reaganomic and virtually every elected federal officer but Mitt Romney with an (R) behind their name.

And that is the essential imperative you need to focus on as justification for removing Donald John Trump* and his White House clown show from office.

0 notes

Text

EXCLUSIVE: How Reporting From Israel Changed My Worldview Forever

I’ve wanted to be a journalist for as long as I can remember. Journalism always seemed like such important work, challenging peoples’ biases, bringing hard truths to the public in order to keep them honest and informed. Ever since I spent two weeks in Egypt as a teenager – this was in January 2001, less than a year before 9/11 – I’ve dreamt of being a freelance reporter in the Middle East. I was fascinated by terrorism, by the idea that someone believed in something so much they’d give their life for it. Every journalist wants to cover the big stories, and I thought the Middle East was the biggest story on Earth. So I decided to go. In 2015, at age 32, my wife and I looked at a map of the Middle East and chose Jerusalem as our new home. Not only was the city Westernized and relatively safe, it was a stone’s throw from the most publicized conflict in the world. That summer we quit our jobs in New York City and moved to Israel. The public appetite for news from Israel-Palestine is almost bottomless, and it wasn’t hard for me to find work after moving to Jerusalem. I quickly started selling stories to news outlets in the U.S., the U.K. and Australia, as well as for Al Jazeera English, which is based in Qatar. It was immediately obvious to me that most of these organizations wanted news that would highlight the suffering of Palestinians and lay the blame on Israel for that suffering. As Matti Friedman, a former editor at the Associated Press’s Jerusalem bureau, wrote in The Atlantic in 2014, the news media views “the Israel story” as a story of Jewish moral failure. Events that don’t support that narrative are often ignored. I was content to tell this story for my first few months in Israel, because I, too, believed it. As I wrote recently in The Jerusalem Report magazine, I had a deeply negative view of the Jewish state until I moved there. I grew up in a WASPy New England town where everyone is a liberal Democrat. For some reason, hostility towards Israel is a knee-jerk liberal opinion in the U.S. (and in much of Europe). As a product of my environment, I believed that Israel was a bully and the primary obstacle to peace in the Middle East. But foreign affairs always look different when they become local, and nowhere is that more true than in Israel. I began to see that one sunny afternoon not long after I moved to Jerusalem. On that day, I went to cover a Palestinian protest at an Israeli-run prison near Ramallah. A reporter for The Independent and I drove out there and fell in with a group of about 100 Palestinian demonstrators as they marched towards the prison. When they arrived, about a half dozen Israeli soldiers came out to meet them. The Palestinians quickly set up a roadblock of burning tires to prevent the Israelis from escaping. More and more protesters arrived – I don’t know from where – but I soon saw them swarming over the hills above the prison, clad in face masks and keffiyehs. It was like a scene from Game of Thrones. Some had knives in their belts. Others had brought ingredients for Molotov cocktails. They took up positions on the hills above the prison and began using powerful slingshots to hurl rocks and chunks of concrete at the six or so Israeli soldiers down below. The Israelis were so outnumbered that I couldn’t help but question the narrative that Israel was Goliath and the Palestinians were David, because here in front of me it looked like the exact opposite. When I visited the Gaza Strip a few months later, I again saw the difference between how journalists portray a place and reality. Reading about Gaza in the news, you’d think the whole place was rubble, that it looks more or less like Homs or Aleppo. In fact Gaza is no different in appearance from anywhere else in the Arab World. During eight days in the Strip, I didn’t see a single war-damaged building until I specifically asked my fixer to show me one. In response, she drove me to Shujaya, a neighborhood of Gaza City that’s a known Hamas stronghold and is still visibly damaged from the 2014 war. Was the destruction in Shujaya shocking? Yes. But it was very localized, and not at all indicative of the rest of Gaza. The rest of Gaza is not so different from many developing countries: people are poor but they manage to provide for themselves, and even to dress well and be happy most of the time. Actually, there are parts of the Strip that are quite nice. I went out to eat at restaurants where the tables are made from marble and the waiters wear vests and ties. I saw huge villas on the beach that wouldn’t be out of place in Malibu, and – right across the street from those villas – I visited a new, $4 million mosque. Do Gazans endure some incredible hardships? You bet. Are most of them living in destroyed buildings, open to the elements, as news outlets often portray them? Absolutely not. I don’t begrudge them their marble tables or their beachside villas. Like anyone else, they want to be comfortable, to enjoy life. But I find it odd that once in awhile, foreign news organizations wouldn’t see fit to run an article about Gaza’s wealthy neighborhoods or million-dollar mosques. But no, they prefer to focus on the tiny minority of the Strip that is still damaged from the war with Israel in 2014 (a war that, by the way, Hamas started) because that is what confirms the narrative that Israel is a superpower brutalizing Arabs for its own selfish purposes and that is the narrative that too many people want to hear. Nevermind the fact that freedom of the press in Gaza and elsewhere in the Arab World is virtually nonexistent. In many ways, trying to report from Gaza was an absurd and dangerous endeavor. During a single week in Gaza, I got in trouble on two separate occasions with Hamas for breaking their strict rules for the press. On the first occasion, my fixer and I were at the beach boardwalk in Gaza City, interviewing people about an upcoming Gaza election (which was later canceled, not surprisingly, since most Arab leaders hate democracy). After about 15 minutes, a young fellow in a T-shirt and cargo pants approached us and had an unpleasant-sounding conversation in Arabic with my fixer, after which my fixer told me we had to leave immediately because the man was a Hamas intelligence officer and was displeased with us asking people political questions. On the second occasion, my fixer and I were photographing destroyed buildings in Shujaya when two Hamas soldiers, neither of whom could have been a day older than 25, literally ran over to our car, took our IDs, confiscated my camera and escorted us to a military barracks where a group of Hamas officials questioned us extensively about who we were and what we were doing taking pictures there. They looked through every photo on my camera before they allowed us to leave. My fixer was visibly shaken. I couldn’t blame her: Hamas often arrests, beats and sometimes even tortures journalists who say things that make them look bad. * * * While living in Israel, I noticed that a lot of journalists seemed to think of themselves as advocates. They spoke of journalism as a way to give voice to the underdog, and for too many of them, Palestinians were the underdog. Good journalism, of course, does not advocate. It tells the truth, regardless of who looks good and who looks bad. Because the truth does not have feelings. Considering this, it’s perhaps not surprising that reporters in Israel and the Palestinian Territories tend to be close with the staffers of human rights agencies. They run in the same social circles, go out to eat and drink together. Perhaps that’s why nearly every article on the internet about Israel contains a quote from the United Nations, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch or other such NGOs. As a reporter, it’s easy to quote these groups because they provide all the information you need, in an accessible, easily comprehensible way. I admire a lot of the work these NGOs do. The problem is that they often act in a way that’s biased against Israel. Too often, they place the blame for Palestinian suffering on Israel, rather than, say, the callousness and corruption of Palestinian leaders, who clearly bear a large part of the blame for their people’s pain. These groups each have their own agenda, but since their public-facing persona is appealing, since they cast themselves as the spokesmen for the oppressed, most liberals living in the U.S. and Europe take them at their word. * * * Working as a reporter in Israel for a year-and-a-half didn’t shatter my faith in journalism. But it increased my skepticism that it can do good in the world. Eight years of working for the news media has made me more and more alarmed by how partisan it’s becoming. News publishers these days target millennials on social media who’d rather see their own opinions validated than see an article that’s balanced and objective. These audiences don’t want to have their biases challenged. If the media exists only to reaffirm what we already believe, we’ll only become more divided, and there will only be more and more conflict in the world. Hunter Stuart is a journalist and writer with more than 8 years of professional experience, currently working as a Senior Editor at Dose Media in Chicago. He was a staff reporter and editor at The Huffington Post in New York from 2010-2015. Most recently, he spent 1.5 years working as a freelance reporter in the Middle East, where he wrote for Vice, The Jerusalem Post, Al Jazeera English, the International Business Times and others. His reporting has also appeared on CNN, Pacific Standard, the Daily Mail, Yahoo News, Slate, Talking Points Memo and The Atlantic Wire. http://honestreporting.com/exclusive-how-reporting-from-israel-changed-my-worldview-forever/

0 notes