#believe it or not afrofuturist artists exist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Things I would like but it's fucking AI art.

Retrofuturism

(adjective retrofuturistic or retrofuture) is a movement in the creative arts showing the influence of depictions of the future produced in an earlier era.

Afrofuturism…

is an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation. “I generally define Afrofuturism as a way of imagining possible futures through a black cultural lens,” says Ingrid LaFleur, an art curator and Afrofuturist.

#I'm getting tired of everyone being too comfortable sharing AI Art in creative spaces#did people not know or just not care??#believe it or not afrofuturist artists exist#that isn't just a bunch of dead eyed women vaugely looking at odd shaped buildings#tomyo says shit

973 notes

·

View notes

Note

Janelle and Solange please!

Solange: When it comes to healing, I believe we’re never done and that it’s a neverending process that demands active listening to one’s self. And right now, honestly, I’m in a slump. I’m dealing with extreme loneliness in my household compounded by a mother that doesn’t see me, and I’m currently in the midst of a heartbreak that is both tied to the intimate and to the larger systems existing in the world. I’m fighting through it, but it’s like swimming in molasses. So right now it’s hard.

Janelle: Honestly, there are a lot of afrofuturist visions that are better and more detailed than mine, from a wide range of very talented and incisive artists. But what I want truly, in an afrofuturist world, is an universe where Black life doesn’t threaten the very meaning of existence. That’s honestly all. I want a world where on a metaphysical level, valuing Black lives, valuing Black people, doesn’t completely unravel the thread that holds the world together. That’s my afrofuturist wish.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

FEEDBACK LOOP #6: Cargo Cults’ “Rammellzee”

Since these symbols and all symbols are drawn, infinity’s separation from all symbols must be shown through drawing. The only proof of such a separation of the infinity would be the understanding by the majority of the planetary peers. There is no other way.

—from IONIC TREATISE GOTHIC FUTURISM ASSASSIN KNOWLEDGES OF THE REMANIPULATED SQUARE POINT’S ONE TO 720° TO 1440° THE RAMM-ΣLL-ZΣΣ (1979, 2003)

The rabbit-hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down a very deep well.

—from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland

Riding among an exhausted busful of Negroes going on to graveyard shifts all over the city, she saw scratched on the back of a seat, shining for her in the brilliant smoky interior, the post horn with the legend DEATH. But unlike WASTE, somebody had troubled to write in, in pencil: DON’T EVER ANTAGONIZE THE HORN.

—from Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49

1. I walk down the street and people look at me and say, “Who the hell are you?”

Cargo Cults (Alaska and Zilla Rocca) begin their track “Rammellzee” with the voice of the some-16 billion-years-old being himself. The song is an ode, an invocation. The organ sample provides a bizarre ride: a carousel of colors. We immediately plummet—into a well, a subway tunnel, a cosmos of linguistics. Not a nonchalant That’s deep, but a depth of knowledge where “cipher” means code, means Supreme Mathematics, means gathering with your rapfolk outside the Nuyorican Poets Cafe or in Washington Square Park: a deep connection. Mimicking Rammellzee, Alaska presents the listener with “swirling pages / forming mazes of [his] formulations” and subsequently “break[s] them down into a form that’s shapeless.”

2. Hip-hop is ageist….In blues, you ain’t official until you fifty. (Ka, Red Bull Music Academy interview with Jeff Mao, 2016)

The phrase …of a certain age has, historically, been used euphemistically to describe someone (typically a woman) who has existed for a “shameful” tally of years. Society is still undoing the stigma, but rappers have made strides.

In Adult Rappers, a 2015 documentary directed by Paul Iannacchino (Hangar 18’s DJ paWL), Alaska is [accidentally?] presented twice in the closing credits—like a double, a separate persona—which calls to mind the multiple personalities of Rammellzee: Crux the Monk, Chaser the Eraser, Gash/Olear, et cetera. Age allows for maturation, for building, for bettering. In Rammellzee’s case—and I’d argue Alaska’s—it allows for complexity to emerge organically through wisdom. It allows for reinvention, for many versions of one’s self. Age and development is how an aerosol can with a fat cap can graduate to customized deodorant roll-ons and shoe polish canisters.

It begins with jerry-rigging a nozzle and ends in diagramming a “harpoonic whip launcher/pulsating extendor” to illustrate the deconstruction of letter-formations in the English alphabet. The spirit of experience pervades the Nihilist Millennial album. As anyone who has ever sat on the couch knows, communication can also improve with age.

3.

Artists and rappers like Rammellzee and Alaska rely on wild-styles, a self-made world that warps quantum physics and disregards notions of dimensionality. It’s dream-vision. It’s liberation. It simultaneously celebrates and critiques communication: like the image of a muted horn.

“Communication is the key,” cried Nefastis. “The Demon passes his data on to the sensitive, and the sensitive must reply in kind. There are untold billions of molecules in that box. The Demon collects data on each and every one. At some deep psychic level he must get through…”

“Help,” said Oedipa, “you’re not reaching me.”

“Entropy is a figure of speech, then,” sighed Nefastis, “a metaphor. It connects the world of thermodynamics to the world of information flow. The Machine uses both. The Demon makes the metaphor not only verbally graceful, but also objectively true.”

[…]

Nefastis smiled; impenetrable, calm, a believer.

The wordplay seems just that: play—that is, until you find the thread. Alaska cobbles together words like rubbish, W.A.S.T.E. Words appear daisy-chained together—flowery, ornate, and strung together by their stems: “fatalism, Fela Kuti, razor thin” / “smash the superstitions with acid tabs and some Sufi visions” / “deep dive Sonny Liston” / “Walt Whitman.”

The track reads like a codex. Something crafted in a scriptorium. His words are warfare—double-tracked/double-barreled—and he slips into braggadocio to prove it. It’s an authoritative posture of experience. Having started atomically small—from Breaking Atoms bedroom listening, to Atoms Family—Alaska’s flow presents nuclear now: maximum damage.

There’s a refinement to what this duo is doing: “Me and Zilla well-established with a lavish vision. / Both hands crusty with Ikonklastic Panzerism.” The boasts rely on royal diction: Camelot, palace doors, Prince Paul. Each man a king, a God, and each one should teach one. Mentor texts for the masses.

4.

Rammellzee is an equation, And simply stated it’s the way of life I’m chasing. That’s why I praise the future-Gothic future-prophet. Gotta rock it, don’t stop it, Gotta rock it, don’t stop.

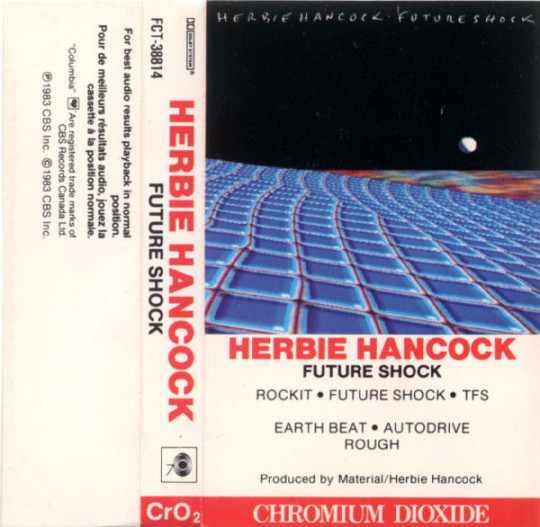

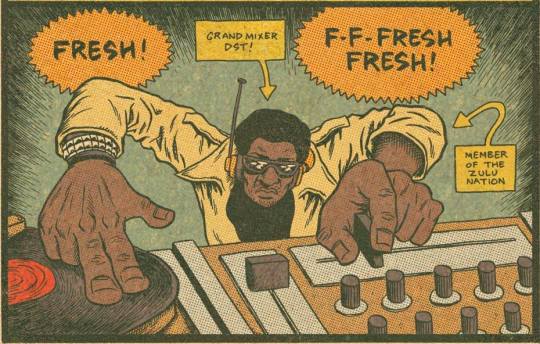

You find diversions on the song, exits into familiar chambers. GZA quotations (“I was the thrilla in the Ali-Frazier Manila”) and allusions to Main Source. Large Professor rapped “Dead is my antonym,” and if that’s to be proven true, money needs to be removed from the equation. The refrain of “Gotta rock it” not only calls to mind “Beat Bop,” Herbie Hancock, and Grand Mixer DS.T (or his later incarnation, DXT), but rockets—Afrofuturist angles, future shocks (Bill Laswell [Material], friend to Rammellzee, had a hand in all this). It’s not so much a “future-prophet” as a “future profit.” “Freedom in the process” means creativity without expectation, without the constraints of market value.

Alaska gives it to us straight: “I don’t care if you don’t like it, and I don’t care if you don’t buy it / ’Cause I find freedom in the process.” Despite becoming increasingly complex in his visual approach—like a heap of garbage that loses the definition of its component parts over the ages—Rammellzee understood time equals clarity of vision. A wasted world becomes a meaningful one. Of course, we got to pay rent, so money connects, but ownership of one’s art is about empowerment. “Selling out” is the opposite—an evisceration of one’s self and spirit. “We lost control from the second we sold the art,” Alaska raps. “We sold our future….We should be seeking enlightenment.”

The moment arrives, epiphanically: “I find freedom in the process so I’m grateful, / And that’s my main source: it’s my friendly game of baseball.” For Alaska and Zilla Rocca, it’s not a job—it’s a passion, a pastime.

5. Nascent imagination deep inside a battle station.

Post-9/11 meant luxury apartments displaced Rammellzee’s Battle Station loft, his living museum. But the art has been excavated and exists posthumously. His Gothic Futurism and Ikonoklast Panzerism seem at home archived on the internet—a network that appears more like a chaos cloud. Rammellzee deconstructed and transcended language—junk monk scripts and calligraphic cut-ups of consumerism. His art is the empowerment a recycling arrow-triangle could only hope to be. Recycle is also rebirth. Rammellzee’s career path is circuitous, deep-tunneled (subway-esque), eternal.

Similarly, Alaska’s multisyllabic patterns are an endless barrage, like weaponized letters tilted sideways, like bottle rockets angled into a bottle’s neck: “Armament / Now my names are built like a BattleBot / Locked inside an ad hoc Camelot, I rather not / Tangle with a rabid lot, hop inside a rabbit hole.”

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice “without pictures or conversations?”

Boredom can make trouble, but boredom can also breed creativity. Alaska rather not spar with trolls under ISP bridges—though he’s equipped to. Instead, he channels his energies into material.

6. Our culture is done. We lived it.

Near the end, Alaska paraphrases Rammellzee: “I’m not the first or the last to don the mask. / I see it as a title, I’m monastic with these raps.”

Living a life of art—making it regardless of accolade or monetary payment—is the highest form of creativity. Live the art and die by it, like Stan Brakhage, poisoning himself at a slow pace as he applied toxic dyes to celluloid film. Like Rammellzee executing graffiti pieces maskless, huffing the carcinogenic fumes.

MF DOOM (née Zev Love X)—a Rammellzee descendant—taught us how to revel in anonymity, the importance of not spotlighting yourself, but instead seeking out the shade, secret passageways, and the trapdoor in the stage floor. Not all of us heed the advice, but some do, and they feel the throb of real success, not the sort that shows up in bank statements and 401(k) plans.

Images:

“Beat Bop” test pressing, Rammellzee and K-Rob, art by Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1983 (detail) | Rammellzee black-and-white portrait photograph (unknown) | Ikonoklast Panzerism diagram from IONIC TREATISE GOTHIC FUTURISM ASSASSIN KNOWLEDGES OF THE REMANIPULATED SQUARE POINT’S ONE TO 720° TO 1440° THE RAMM-ΣLL-ZΣΣ (1979, 2003) | Page 34 (muted post horn) in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, Bantam Books edition (1966) | “A scribe at work,” from an illuminated manuscript from the Estoire del Saint Graal, France (Royal MS 14 E III c. 1315-1325 AD) | Herbie Hancock, Future Shock cassette cover (1983) | Grand Mixer D.ST comic book image (unknown) | Stan Brahage at chalkboard (unknown) | Stan Brakhage, Mothlight celluloid (1963) | “Beat Bop” test pressing, Rammellzee and K-Rob, art by Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1983 (detail)

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

With the record-breaking film "Black Panther" becoming the first superhero movie ever nominated for an Oscar for best picture, Afrofuturism is gaining new momentum — even beyond film. Afrofuturism is a social, cultural and political philosophy dating back to the 1950s. It aims to reclaim black history by imagining an alternate future that incorporates science fiction, technology and African mythology.

"I see these tweets at times where people are like, 'I just want to see black mermaids, and black people in space… I want to see black stories that aren't about black pain.' Because the pain is constant," author Tomi Adeyemi told CBS News' Alex Wagner. At just 25 years old, the Nigerian-American writer is among the artists at the forefront of the resurgence of Afrofuturism.

"It's just kind of like a utopia to imagine, 'what if...'. Like, what if the story wasn't a story of having everything taken away, and having so much, like, oppression and brutality and senseless murder and slavery. Like, what if it could be something completely different," Adeyemi said.

That's the foundation of the bestseller "Children of Blood and Bone," a West African fantasy novel featuring a young, black female protagonist.

"When did it occur to you that women of color, men of color, children of color can be fantasy characters?" Wagner asked. "I didn't realize until my senior year of high school that no characters looked like me. So all of my protagonists were white or they were biracial. … Then I realized it's not just me who needs this, it's, like, it's other people who look like me. But it's also people who don't look like me. Because the reason I didn't think I could be in a story was 'cause I didn't see it," Adeyemi said. Through her writing, she also directly tackles racism and inequality. "I wanted to write a story that commented on the black experience," Adeyemi said. "In some ways, Afrofuturism is inherently kind of a revolutionary act. Do you think of yourself as a revolutionary?" Wagner asked. "At this point, I can think of myself as a part of the revolution," Adeyemi said.

So does Grammy nominee Janelle Monáe. On her new album, "Dirty Computer," Monáe explores Afrofuturism through music.

"Afrofuturism is about African-Americans, Africans, black people, us seeing ourselves in the future… knowing that we exist in the future, knowing that we are not the stereotypes that have been perpetuated on us," Monáe told CBS "Sunday Morning."

Monáe believes this is the time for Afrocentric art. "It's a way for black women like myself to tell our stories through our own lens. Because I think it's important that we're telling our stories. Because if we allow other people who are not us to tell our stories, they may not be told properly," she said.

Enter "Black Panther" with a black superhero and a nearly all-black cast set in an African-inspired utopia sometime in the future. "Black Panther" popularized the idea of Afrofuturism, but its roots run deep.

"All the early abolitionists that we celebrate, the Frederick Douglasses… the Sojourner Truths were all Afrofuturists. Harriet Tubman… Sun Ra and George Clinton," cultural critic Greg Tate said. He is considered one of the leading scholars of this movement. "Anybody who had a vision of the black people's story and presence and imaging could be told and elevated," Tate said. "On one hand we have a movie like 'Black Panther,' which is a lot of people's entry point for Afrofuturism. But you also have the Black Lives Matter movement, right? Do you see a connection between those two things?" Wagner asked.

"Oh, definitely. I mean, I don't think that 'Black Panther' would've happened without the precedent of Black Lives Matter, because I think that any time… there's outrage and protest in the streets, the culture of elites in America tend to open up resources and opportunity and space for, you know, for black creatives," Tate said.

The response suggests audiences will start to see even more Afrofuturist art. "Black Panther" snagged the top prize at the SAG Awards, is nominated for seven Oscars, and a sequel is underway.

Adeyemi's book is being made into a major motion picture and she has two more books in the works. She said the arts and entertainment landscape is definitely changing.

"We're finally getting people who want to share it with people, and people who don't think that, 'Oh, people aren't gonna relate to this, because it's black,' or, 'They're not gonna relate to this, because it's African, it's too different.' They're like, 'No, this is a great story with great characters. So let's make it visible.' And when people find it, they'll fall in love with it," Adeyemi said.

Adeyemi signed a rare seven-figure deal for the movie before her book was released. She's been compared to a young J.K. Rowling, so maybe it's no surprise.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Afrofuturism

Afrofuturism is a community, a response, a battle cry, a home. It is a place where Black writers and readers can explore themselves with no inhibition, and can rejoice with others who feel the same way. It is a response to decades of being pushed out, written out, and disregarded in an entire beloved medium. As if black people cannot exist in the future. It is a battle cry, where black people can imagine what the revolution will feel like, and can write it down into words and share it. It is a safe space to imagine Black life in the past, present and future in the kind of scenarios and settings that are only reserved for white individuals.

My final project considered the works of the artists we have discussed over the course, like Janelle Monae, Beyonce, and Professor Due. There were other artists who impacted me just as deeply that I did not get a chance to shout out: SUN RA, George Clinton, Steven Barnes, etc. Although I took the more analytical approach to my final project, the artistry within this class is what has had me hooked since week 1. An alternate universe where irishmen were the slaves rather than Africans. A film where America must vote on sending every Black person up into space. A film where a black slave from space crash lands on earth and attempts to find safety. These are definitely far out concepts. But they are so valuable to the community. Social commentary is what makes these works of art masterpieces. I believe that unfortunately, to be black is to be political, and in these works it is no different. But the social commentary, the critiques on hierarchy, the contemplation of true freedom is what transforms your average work of fiction into a lesson or even just a memorable reading experience. There is the idea that being too outwardly political can be dangerous for Black individuals, with good reason. Perhaps that is why these incredible works of art are not often brought up in conversations, book recommendations, or good films to check out. Nevertheless, they are still there waiting to be discovered.

Each and every afrofuturist story puts the control in the reader's hand. Themes that connect so intimately to our real lives cannot be ignored so easily. By taking the time to look past the surface level of these artworks, you find a real treat looking back at you. Questions to contemplate, answers to questions, thoughts you did not know you had in you are all there ready for the taking. Taking this class is an asset to your critical thinking skills, and If I could take this course over again, I would.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Afrofuturism Dictates Our Past, Present, and Future

I definitely do think that afrofuturism has the potential to change the way people think about the real world. In fact, I see that happening right now. I’ve noticed that many Black musical artists have adopted elements of afrofuturism in their own stylistic work. I think what is most interesting about it all is how these artists tend to blend afrofuturism with other themes pertaining to social justice and/or the Black experience. We’ve seen this in music, for example. With modern examples such as Lil Nas X and Janelle Monae who combine themes of queerness with fantastical elements of technology or Beyonce who – albeit more subtly – utilizes the expansiveness and almost other-wordly elements of afrofuturism, we can see how these artists are changing the way people think about the real world little by little. The themes that are being communicated to their audience are deeply profound and may perhaps be a bit too much to digest considering how much of the themes have to do with overcoming trauma and adversity. By communicating these themes metaphorically through more imaginative world-building, people are more receptive to these more serious themes because they are allowed to pick and choose what they want to apply to their own lives. I believe that that is the magic of afrofuturism: it allows people to open their minds to possibilities that have never been considered before. In a world as bleak as this, that includes allowing yourself the possibility to hope (which is a constant theme in afrofuturistic works). What is also so amazing about afrofuturism is that no one else is able to recreate it. When white people or non-Black people try to make a story on afrofuturism, it tends to fall short more often than not. Afrofuturism allows Black creatives a space to conjure up their own stories. Caucasian-futurism does not exist because – let’s be real – white people don’t have the capacity to imagine what it means to be oppressed. They may think they’re oppressed – by robots and technology most of the time – but they only believe that because the only thing that is threatening their survival is themselves. In all sci-fi films, (white) humankind tends to be overrun and controlled by a technology that it has invented but has gotten out of hand. Not only are the enemies in such films products of capitalism and corporate greed for reduced labor costs, but the enemies also tend to be white people’s own inventions. In short, white people bring their problems upon themselves. Of course, this is an issue that is reflected in real life as well; there is an abundance of white tears when African Americans simply ask for reparations for slavery or, at minimum, social equity. On the other hand, afrofuturism is so limitless as a genre because Black struggles are extremely multifaceted and can be presented in so many different ways. The intersectionality of themes is another element that is ever-present in afrofuturistic works – something that not many white-dominated sci-fi works can claim. Other than the musical artists that I mentioned above, I want to shine light on, once again, one of my favorite movies of all time: Sorry to Bother You. Through the themes that were observed in the film, we can definitely see how Boots Riley has his roots in activism. By addressing the many challenges of racism, white supremacy, class, unionism, and more, afrofuturism assumes an entirely different role in this movie by amplifying its core themes rather than overtaking them. Sorry to Bother You is deeply profound in the way that it encourages its viewers to think critically about the world with both its direct and indirect metaphors. Of course, this isn’t just exclusive to Sorry to Bother You – films like Get Out (a cultural reset) also encourage their viewers to rethink their positionality in the real world and how the privileges (or lack thereof) that they may have. So, do I think that afrofuturism has the potential to change the way people think about the real world? I believe that the clear answer is that it already is. When we allow Black creatives to work their magic, we receive masterpieces across all forms and mediums. Behind every heated discourse is a Black creative and I find that to be the case because they are quite literally producing life-changing works. Be it the genetic struggle to survive or an enlightened double consciousness, I think it would be extremely difficult for non-Black people to imagine the realities that we see in afrofuturism. I also think that this is why Black people tend to be the trailblazers of most trends and inventions (in music, fashion, and almost everything) and also why their talent and culture is always appropriated. Afrofuturism is radically changing not only the way people think about the real world, but also changing the way they actualize these thoughts into action.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reasons I hate the Hamilton fandom

Disclaimer: I’m a mod of one Hamilton fb group, an admin of another much smaller group, have seen the show twice, and a huge fan of many of the actors and creatives, not just the original cast. I am entrenched in the Hamilton fandom and have been for nearly 2 years so all of this comes from personal experiences with the fandom. I do not hate the actual musical and having talked to many folks and made friends through this fandom, I can confirm that it has had a positive effect on many people, especially aspiring actors of color. I had criticisms of the actual musical (reductive view of American history, perpetrates American exceptionalism, bootstraps narrative, not as feminist as fans insist, etc) but I’m mostly just addressing the issues within the fandom not within the media. The problems with the fandom is nebulous and manifold so I’m gonna try to be as thorough as possible here: - for those that don’t know, Hamilton is a show made by POC creatives for actors of color. The casting is not “color blind” it is racially conscious. All leads always, aside from the silly, villainous King George, are intended to be played by actors of color and the much of the fandom absolutely REFUSES TO ACKNOWLEDGE THIS. It ranges from the benign-seeing assertions that Hamilton is colorblind and therefore race of the actor doesn’t matter as much as talent (false, with the underlying belief that a white actor will somehow be better suited/more talented in a role that is literally not written for them) to petulant assertions that one white fan or another will be the first white actor to play x role, to erasing the racial identities of light-skinned black, latinx, and asian actors to fit the manufactured narrative that white actors can and have played principal roles and the show is therefore colorblind. Fans are quick to point out the ambiguous wording of “America then told by America now,” intended to subtly indicate POC, as meaning white folk, despite the continuous assertions by the creatives that this is simply not the case. - whitewashing in fan art. Hand in hand with the refusal by many white fans to acknowledge the fact that Hamilton the Musical is intended for POC, white fan artist almost universally draw the actors-as-characters with lighter skin, lighter eyes, and more typically European features. Lin, who played Hamilton in the original cast, is a Latino man of mixed race heritage with tan skin, black hair, and dark eyes yet fan art of him as Hamilton is nearly always pale, red haired, and sometimes even blue-eyed. Artists will defend this as interpretation and some will even indicate that Hamilton was white irl so this is more accurate but Hamilton irl and Lin were nothing alike and he presence of a goatee in Hamilton Fan art is an indisputable sign that the artist is drawing Lin, not the real life, baby faced Hamilton. Dark skinned actors like Okieriete Onaodowan (Hercules Mulligan in the original cast) are rarely drawn and when they are they tend to be heavily lightened. - characters deemed queer by the fandom - notably John Laurens who was thought to be gay or bi in real life by many historians - is often heavily feminized in fan art, despite the fact neither the character nor the actual figure are ever noted as being particularly effeminate. This is of course fetishization symptomatic of applying heteronormativity to gay relationships. - fans often reject and demonize female characters. This is not universal but many fans have negative reactions to Hamilton’s wife, Eliza (and ignore and/or demonize her in regards to the gay ship of Hamilton/Laurens, despite Laurens having died shortly after Hamilton married Eliza. Hamilton fans believe almost universally that Hamilton was bi irl, which is supported by historical consensus, but the notion of him actually being with a woman repulses much of the fandom. - basically standard biphobia). Fans are also extremely gross about Maria Reynolds. - a separate part of the fandom refuses to acknowledge both the historical consensus of the Hamilton/Laurens relationship and the fact that that musical contains several intentional references to it. I’ve been told many times to keep that “gay shit” out of the fandom. - shipping wars of course. - blind worship of the characters either without regard to their historical counterparts or including their historical counterparts. - slavery apologism. Comparing slaves to modern consumer items and/or farm animals to demonstrate the ubiquity of slavery and/or people’s mindset regarding it. While it is true that people are the product of their time, “everyone owned slaves” and “you cannot judge them by the Norms of our culture” are common silencing/apologist techniques which both lack nuance and perpetuate racist ideals. It also erases the fact that abolitionism and moral opposition to slavery existed not only in post-revolution society but also within the very people who owned slaves. Thomas Jefferson wrote that slavery was the worst evil while simultaneously owning and raping slaves. - I’ve encountered at least one person with a bona fide slavery fetish. That’s not the fandom as a whole but it is worth noting. - abhorrent beliefs are common re: Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings. - this has basically been covered above but rampant racism is not uncommon in this fandom. You get the distinct feeling that a sizeable portion has never once interacted with a person of color before, based on the ways they claim ownership over the actors, portray the characters, talk about racial issues, etc - speaking of the actors: fans are very gross toward the actors in a variety of different ways. - fans fetishize the fuck out of Daveed Diggs, who played Jefferson in the original cast. Diggs, for reference is a biracial black Jewish man, a rapper, actor, and activist best known outside of Hamilton for his work with clipping., which includes an extremely politically charged afrofuturist space rap opera. Fans tend to do a couple things in regards to Diggs. One, they conflate him with irl Jefferson leading so some really and truly bizarre headcanons and fan interpretations. Diggs himself has no love for irl Jefferson and has - along with the rest of the cast - cautioned fans against romanticizing the real figures, apparently to limited success. More heinously, however, I have seen people claiming ownership of Digg’s body and hair (claiming they would be upset if his cut it, or would stop being his fan even), made comments about keeping him as a sex slave, fetishizing his ethnic features, or even denying his blackness in favor of fetishizing his white, Jewish heritage. I’ve even seen a white woman comment that she wanted to kill diggs’ black girlfriend, skin her, and wear her as a suit to attract Diggs. No fucking joke. Diggs work as a musician is loved by many fans but others reject it as “scary black music.” - this happens with other actors tho not as much as Diggs. Fans have made plenty of comments about Okieriete Onaodowan’s “big black spy on the inside,” for instance, showing further capacity to fetishize black bodies. - for many fans, the original cast can do no wrong. They will go out of their way to justify and forgive anything that can be seen as problematic rather than acknowledging that they can still like a person that has problematic aspects. - or conversely, they gang up on actors on twitter, or tag them in hate/undeservedly negative critique. - replacements and non-OBC casts are largely ignored and several of the actors have been trolled or sent hate simply because they are not the originals. There is also the mindset that no one could ever be better than the original and the show is not worth seeing without the originals which is extremely disrespectful toward the replacement actors. - a large portion of the fandom claims that Hamilton is the only rap they like, or that they don’t like hip hop at all. When the Hamilton mixtape - and album featuring inspired-bys and covers of Hamilton songs by contemporary singers and rappers, was released fans HATED IT, many pointed out that they hated the hip hop sound and the “bastardization” of the music. Many of the songs on the Mixtape were by artists which inspired Hamilton in the first place. - a lot of the fans are just plain cringey. Bad head canons which become more ubiquitous than the actual canon portrayals, extremely forceful when it comes to trying to “convert” people, extremely adverse to any kind of criticism of the musical, history, or the actors, obnoxious at cons, etc. - art theft is rampant - extreme classism re: bootlegs especially - older fans have a tendency to be extremely abusive toward younger fans. Not all young fans are bad but bad memes and stupid references are met with extreme, quick, and unwarranted vitriol.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ellen galagher Dont axe me Article :https://hazlitt.net/feature/search-black-atlantis In September 2015, Kyle Lydell Canty of Rochester, New York, travelled to British Columbia. He hadn’t planned to stay for long, but after two days in Canada, Canty decided to apply for refugee status. He appeared before the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada in October of that year with the argument that Black Americans were “being exterminated at an alarming rate.” As proof, Canty alleged that he had been harassed by the police in six states in which he held offenses, such as jaywalking and disorderly conduct, that he claimed he never committed. Although the Board ultimately rejected his candidacy on the grounds that Canty would not be subjected to “cruel and unusual punishment” upon his return, Ron Yamauchi, an IRB member, did find that the actions of the American police “raise a question about [Canty’s] subjective fear,” a fear that, according to the United Nations, is rooted in historical and racially terroristic acts, such as police killings and “state violence.”

In 1838, after a failed attempt that led to his incarceration, twenty-year-old Frederick Bailey used his nautical knowledge while working at a waterfront to disguise himself as a free Black sailor and boarded a train from Baltimore to New York where he then changed his last name to Douglass to avoid suspicion.

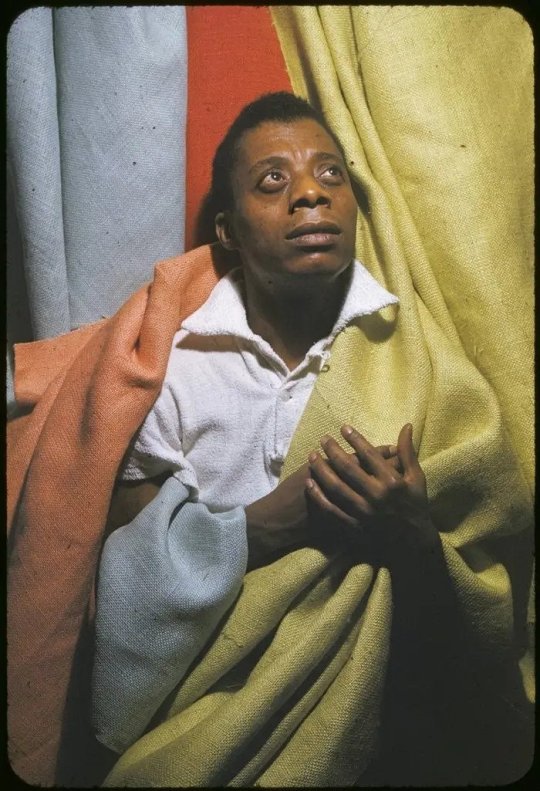

James Baldwin could not reconcile himself with America. He travelled and lived in places such as Istanbul and Paris in the 1960s, where, according to a 2009 essay in The New Yorker by Claudia Roth Pierpont, he would not be shamed for the color of his skin or his sexuality. Nina Simone revealed in her autobiography I’ll Put A Spell On You why she left America for Liberia in the 1970s: “I had arrived in Liberia with no idea of how long I intended to stay; after a few hours I knew it was going to be for a long, long time—forever.” When she returned to the States for financial reasons, “I flinched at every noise, expecting terrible events that always hit me when I arrived in the country that disowned me … I … longed for Liberia …”

The desire to escape endures within many Black Americans. It manifests in literal attempts at relocation, as in Canty’s case, but also through our art. “I think to be born Black in America,” said the video and performance artist Lex Brown, “is to be fully in touch with, one, the universal existential crisis of being human, two, the crisis of carrying on the body of an un-chosen evidence of the fundamental hypocrisy of America (i.e. home of the free, land of the slaves) and three, the impossibility of escaping or delaying crisis number one because of number two.” Our perpetual lack of belonging fuels our desire to flee, but where do you turn when there seems to be nowhere to seek refuge?

*

Sarah Yerima, a Rhodes Scholar studying sociology at the University of Oxford, has been moving between countries for five or six years, from the United States to Brazil to the United Kingdom. “I’ve been trying to find some peace and it’s all terrible. No matter where I am, the anti-Blackness is pervasive. However, the arts give a kind of comfort.” In 1977, The Isley Brothers released “Voyage to Atlantis,” in which lead singer Ron Isley croons to an unnamed woman about sailing to a “paradise out beyond the sea.” That same year, DC Comics released issue #452 of the Adventure Comics series, in which Black Manta, a Baltimore native turned supervillain whose nautical and birth origins are reminiscent of those of Frederick Douglass, seeks to take Atlantis from Aquaman, a blonde-haired, white superhero, by killing his son. In a standoff, Black Manta says to Aquaman, “This city … shall … be a new empire over which I alone shall rule! … I had recruited enough of my own people to serve that purpose …”

“Your people?” Aquaman responds. “You mean … surface dwellers?”

“No,” Black Manta says, “I mean exactly what I said, ‘My people.’ Or have you never wondered why I’m called Black Manta?” Black Manta wanted to create an underwater colony in which African-Americans could rid themselves of a white-dominated surface world.

In the packaging for Outkast’s 1996 sophomore album ATLiens, the artwork features Big Boi and Andre 3000 as freedom fighters against censorship and population control; Atlanta is re-pictured as the lost city of Atlantis. These artistic renderings of a Black utopia present a hopeful future—places where we can live in all of our complexity and without oppression.

“If you think about how American planning has worked, it has always pushed towards a utopia. New York, Chicago—all major American cities—as violent as they were, were utopic visions,” says Jess M., a student and researcher of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning. In designing cities deliberately to oppress people of colour, she says, “planners believed that if Black and brown people didn’t exist, then these utopias would.”

This racism has led many Black artists to reimagine fictitious nations, such as Atlantis, or develop new mythologies altogether through Afrofuturism, a literary and cultural aesthetic that blends historical components, along with science fiction and fantasy, in order to center Black people.

The musician, philosopher, and filmmaker Sun Ra was one of its pioneers, creating what Ytasha Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture calls, “sonar sounds for the space age in the ’50s.” In the 1970s, the Afrofuturistic sound began to expand. Combined with sci-fi elements in works such as “Spaceship Lullaby” and “Africa,” in his 1974 film Space is the Place, Sun Ra, playing the protagonist, seeks to transport African-Americans to occupy a new planet in outer space he discovers with his crew, The Arkestra.

Sun Ra’s influence continues to be felt. George Clinton and the Funkadelics incorporated Afrofuturism into their works through electronic instruments, space costumes, new mythology, and mind-boggling wordplay. Janelle Monae’s android aesthetic is a direct descendent of Sun Ra’s innovation. Contemporary artists Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski and Sheena Rose depict black women as goddesses, mythical creatures, and arbiters of their universe. As Stephanie George, former curatorial fellow of New York’s Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, puts it: “You have to disrupt temporality.” In order to find purpose and affirmation, a Black artist must undermine time and space as we know it to find a place for his or herself.

*

Since the 1800s, refuge and relief from racist violence and oppression has meant any number of things: escaping to the North, fleeing to a different country altogether, or staying put physically while moving forward in one’s imagination to create a world where Black people are uplifted and able to live as multidimensional human beings. Many of the greatest African-American works of art have been the products of times of oppression. Our art is a form of resistance.

So now, days away from the inauguration of a president whose platform was praised by the Ku Klux Klan, what happens to that art? Will there be a new renaissance or simply a continuation of established genres? Geraldine Inoa, a playwright at New York’s Public Theater, says that disturbing events like the Trump inauguration often inspire people to “retreat” to other artistic movements. “But because this art exists in this reality under this president, it will be different. Trump is rather unique in that he has risen during new a technological world that has changed the way art is created and shared. We will see a new renaissance based on the current reality that combines the modern tools artists have their disposal.”

Or, as the queer femme writer and editor Myles Johnson puts it, “there’s going to be a renaissance and we can’t help it. Black people have never not been creative.”

1 note

·

View note

Link

Sarah Yerima, a Rhodes Scholar studying sociology at the University of Oxford, has been moving between countries for five or six years, from the United States to Brazil to the United Kingdom. “I’ve been trying to find some peace and it’s all terrible. No matter where I am, the anti-Blackness is pervasive. However, the arts give a kind of comfort.” In 1977, The Isley Brothers released “Voyage to Atlantis,” in which lead singer Ron Isley croons to an unnamed woman about sailing to a “paradise out beyond the sea.” That same year, DC Comics released issue #452 of the Adventure Comics series, in which Black Manta, a Baltimore native turned supervillain whose nautical and birth origins are reminiscent of those of Frederick Douglass, seeks to take Atlantis from Aquaman, a blonde-haired, white superhero, by killing his son. In a standoff, Black Manta says to Aquaman, “This city … shall … be a new empire over which I alone shall rule! … I had recruited enough of my own people to serve that purpose …”

“Your people?” Aquaman responds. “You mean … surface dwellers?”

“No,” Black Manta says, “I mean exactly what I said, ‘My people.’ Or have you never wondered why I’m called Black Manta?” Black Manta wanted to create an underwater colony in which African-Americans could rid themselves of a white-dominated surface world.

In the packaging for Outkast’s 1996 sophomore album ATLiens, the artwork features Big Boi and Andre 3000 as freedom fighters against censorship and population control; Atlanta is re-pictured as the lost city of Atlantis. These artistic renderings of a Black utopia present a hopeful future—places where we can live in all of our complexity and without oppression.

“If you think about how American planning has worked, it has always pushed towards a utopia. New York, Chicago—all major American cities—as violent as they were, were utopic visions,” says Jess M., a student and researcher of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning. In designing cities deliberately to oppress people of colour, she says, “planners believed that if Black and brown people didn’t exist, then these utopias would.”

This racism has led many Black artists to reimagine fictitious nations, such as Atlantis, or develop new mythologies altogether through Afrofuturism, a literary and cultural aesthetic that blends historical components, along with science fiction and fantasy, in order to center Black people.

The musician, philosopher, and filmmaker Sun Ra was one of its pioneers, creating what Ytasha Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture calls, “sonar sounds for the space age in the ’50s.” In the 1970s, the Afrofuturistic sound began to expand. Combined with sci-fi elements in works such as “Spaceship Lullaby” and “Africa,” in his 1974 film Space is the Place, Sun Ra, playing the protagonist, seeks to transport African-Americans to occupy a new planet in outer space he discovers with his crew, The Arkestra.

Sun Ra’s influence continues to be felt. George Clinton and the Funkadelics incorporated Afrofuturism into their works through electronic instruments, space costumes, new mythology, and mind-boggling wordplay. Janelle Monae’s android aesthetic is a direct descendent of Sun Ra’s innovation. Contemporary artists Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski and Sheena Rose depict black women as goddesses, mythical creatures, and arbiters of their universe. As Stephanie George, former curatorial fellow of New York’s Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, puts it: “You have to disrupt temporality.” In order to find purpose and affirmation, a Black artist must undermine time and space as we know it to find a place for his or herself. [Read More]

#Sun Ra#The Isley Brothers#Parliament#Funkadelic#George Clinton#Outkast#Stephanie George#Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski#Sheena Rose#Ytasha Womack#Big Boi#Andre 3000#Janelle Monae#Sarah Yerima#Frederick Douglass#James Baldwin#Nina Simone#Ronald Isley

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Alright” by Kendrick Lamar Review

Kendrick Lamar is a powerful and prominent voice within the Black community. He has a way of addressing the hardships that the Black community faces with a positive afrofuturistic outlook. The overarching message of this song is “We gon’ be alright.” This message is important because it can sometimes feel impossible to move the right way as a Black person. And by right, I mean in a way that won’t get you killed. It’s not even just the police who are a threat to Black people anymore, it’s white people as a whole. Ahmaud Arbery was chased and gunned down by a random white father and his son while he was jogging in his neighborhood. When events like this happen, it’s hard to believe that the senseless killings will ever stop. It’s hard to truly believe that you won’t be next. However, Kendrick knows this and uses his musical talents to send this message of hope to his people in the name of unity and peace.

There are multiple aspects of this music video that deserve deep analysis. For starters, the entire video is in black and white. This speaks to the irony of how differently Black people and white people view the world. Things are never as black and white as they seem, especially for Black people, but because white people seem to use this lens, Black people are forced to live in a world that operates this way. The next scene depicts Kendrick in a car with his friends having a good time talking about the hardships they’ve faced while the pigs are carrying the car beneath them. This is a loud statement because it has always been and forever will be fuck 12. The music video then goes into multiple scenes of Black children singing, dancing, and playing across the city genuinely enjoying life. There’s a cop at every corner trying to rain of everyone’s parade. In the end, Kendrick is standing on top of a street light. A cop makes his hand into a gun, aims it at the artist, and pulls the trigger. You can then visibly see the bullet go through Kendrick’s heart as he falls from the street light to the ground. On his way down, his outro proceeds. His outro is powerful because he speaks of the temptations that Black men face and that internal struggle to stay true to yourself in a world that only tries to demonize your existence. He then finally hits the floor with a smile on his face

0 notes

Text

James Baldwin's “I Am Not Your Negro” And The Revival Of The Black Arts Movement

by realmarcusscott

Community Contributor

The writing of civil rights icon and literary titan James Baldwin has recently experienced a renaissance, but recent media attention could also be signaling a revival of black thought.

In a televised interview with psychologist Dr. Kenneth Bancroft Clark, writer and social critic James Baldwin appeared in “The Negro and the American Promise,” alongside then-polarizing civil rights activists Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and Minister Malcolm X to discuss race relations in the U.S. The New York Times would later describe the 1963 broadcast (itself the product of Boston public television producer Henry Morgenthau III) and particularly Baldwin’s segment, as “ television experience that seared the conscience.” Given the zeitgeist, whilst viewing Raoul Peck’s climacteric 2016 documentary film “I Am Not Your Negro,” the heart-pounding anxiety in Baldwin’s words in that interview seem to reverberate like an atomic bomb in an echo chamber.

“That’s part of the dilemma of being an American Negro; that one is a little bit colored and a little bit white, and not only in physical terms but in the head and in the heart, and there are days -- this is one of them -- when you wonder what your role is in this country and what your future is in it. How, precisely, are you going to reconcile yourself to your situation here and how you are going to communicate to the vast, heedless, unthinking, cruel, white majority, that you are here? And to be here means that you can’t be anywhere else,” Baldwin said. He continued. “I’m terrified at the moral apathy -- the death of the heart which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long, that they really don't think I’m human. I base this on their conduct, not on what they say, and this means that they have become, in themselves, moral monsters. It's a terrible indictment -- I mean every word I say.”

What makes Raoul Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro” an essential viewing on par with, say, “13th,” Ava Duvernay’s incendiary documentary about race and mass incarceration? Based on 30 completed pages of James Baldwin’s final, unfinished manuscript Remember This House and narrated by actor Samuel L. Jackson, Peck’s award-winning documentary truly shines when there is more emphasis on archival footage than the words of Baldwin’s partial script due to his death from stomach cancer at 63 in 1987. Peck spends considerable time highlighting celebrities and literary luminaries of the time who were active during the African-American Civil Rights Movement (1954–1968). Including found footage of glitterati such as Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Lorraine Hansberry, and diverging political activists like Charlton Heston. In his directing, Peck appears to make a clear and concise distinction between artists of the 1960s and the contemporary artists of the iPhone generation. But that’s about it. The film progresses at a crawl when it delves into poetics, as Samuel L. Jackson tries to capture the color of the fallen literary titan.

That is in no way a kiss-off of one America’s Greatest Writers, nor of Mr. Jackson’s work as actor, but a reflection on Peck, whose work on the film inspires more questions of interest around Baldwin, his politics and his bibliography. Footage where Baldwin takes center stage and articulates American imperialism is more appealing and more profound than Peck’s reimagining of Baldwin’s last words. But perhaps, that’s unfair. After all, Baldwin casts a tall shadow. Marking the 30th Anniversary of his death, Baldwin’s influence continues to towers over the Afropunk collective, the Black Lives Matter international activist movement, and what appears to be a revival of the Black Arts Movement via TV, film, modern art and of course, on the proscenium stage.

In Fall 2016, his influence saturated the DNA of genre-bending musicals like Stew’s The Total Bent (which he co-wrote with Heidi Rodewald and his band, The Negro Problem) and Party People by UNIVERSES, both performed at the Public Theater. Shortly after those shows ended, the year was capped off with Can I Get a Witness? The Gospel of James Baldwin by neo-soul progenitor Meshell Ndegeocello’s Afrofuturistic concert-sermon at Harlem Stages. Each one of these gems tackled contemporary issues (Trump and a divided Capitol Hill, Standing Rock, refugee crisis, domestic terror) while grappling with the state of white America, race relations, anti-blackness and the nature of protest and revolt. In a way, Baldwin’s body of work became what he accused militant Pan-African human rights activist Malcolm X of doing during that interview with Dr. Kenneth Bancroft Clark: “He corroborates their reality; he tells them that they really exist. You know?”

It’s no wonder why black songwriter-storytellers, especially those who have infiltrated the New York City theatre constituency and openly challenge the white hegemony of musical theatre, worship at the altar of Baldwin. The politics of his message—at odds with the militancy of Huey P. Newton and The Black Panthers, the political boondoggle that plagued Julian Bond and John Lewis of SNCC, the black supremacy movement of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam—is an earth-shattering, life-and-death kiss-off to the whole establishment while appraising the perils of every black life in a system engineered and fueled by America’s white supremacist patriarchy.

Baldwin’s worldview was equidistant of two polarizing ideological extremes: A pariah of the integrationist wing of the Civil Rights movement, Baldwin believed in a unified America and agreed in the establishing peace through the nonviolent resistance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his SCLC disciples. But he also believed equally in the deep-seated Pan-African radicalism of Malcolm X. Both incensed black intellectuals, unlike King, Baldwin and Malcolm X were unwilling to were to wait for white society to “solve” The Negro Question, and felt the dominant white culture in America was too toxic for black people and other people of color, considering the effects of systemic and institutional racism. In “The Fire Next Time,” his nonfiction objet d'art, Baldwin wrote: “Things are as bad as the Muslims say they are -- in fact, they are worse... There is no reason that black men should be expected to be more patient, more forbearing, more farseeing than whites; indeed, quite the contrary.”

For newcomers to the work of Baldwin, this may seem disorienting and discombobulating, but that is also what elevates his writing into the upper echelons of American writers. When L.A. musician Mark Stewart, better known as Stew, penned his genre bending semi-autobiographical 2008 rock musical Passing Strange—produced with the support of the Sundance Institute and The Public Theater—the book was purely inspired by Baldwin’s tesseract-warping writing style. Not only did the musical references the New Negro of the Harlem Renaissance, but one its central motifs involved the praise of black artists like Baldwin and Josephine Baker, who expatriated to Paris, France. Shortly after the closing of The Total Bent, in September 2016, Stew reported that he has begun to workshop a song cycle, Notes of a Native Song, inspired by Baldwin’s similarly titled 1955 non-fiction novel.

Other writers have also felt the effects of iconic writer: Pulitzer Prize winner Suzan-Lori Parks studied under Baldwin, who encouraged her to write for the stage and described her as “an utterly astounding and beautiful creature who may become one of the most valuable artists of our time.” Ending her post as a Residency One playwright for Signature Theatre Company this year, the various productions cherry-picked from Parks’ extensive bibliography echo Baldwin’s poetics. There’s also director-playwright Kwame Kwei-Armah. In Dr. Lynette Goddard’s “Contemporary Black British Playwrights: Margins to Mainstream,” Kwei-Armah explained that his plays mirror the ‘diasporic, black politics” influenced by the writings of Amiri Baraka and Baldwin. Journalist-author Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2015 book, Between the World and Me, was inspired directly by Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, and lest we forget, the same book of essays also inspired the Fire This Time Festival, which has become a launch pad for early-career playwrights of African and African American descent. Diverse artists are also taking inspiration from Baldwin, like Pulitzer-winning Puerto Rican playwright Quiara Alegría Hudes, who wrote the book for the musical Miss You Like Hell, with help of her outrage in the post-election period and Baldwin’s poetry.

In a neoreactionary zeitgeist contaminated by Breitbart News-quoting white nationalist right-wing populists, and the ever-present tinges of anti-blackness, xenophobia, fear of immigrants, anti-feminism, proliferating ableism, and rampant homophobia and transphobia, Baldwin’s work may not only be the beacon of a Black Arts Movement revival, but a war cry for all diverse artists. To put it simply, Baldwin was a futurist. His genius—highlighted by unpatrolled mordant wit, piquant rue, spill-the-tea élan and unparalleled black boy voodoo—is a master class of artistry; regardless of context, his writing accentuates and deliberates not only the consistent struggle of black people but all of the colonized English-speaking nations of the world. Woah!

Contemporary artists have big shoes to fill. But given the state of the nation, we’re in good hands. Rest in power, Mr. Baldwin.

0 notes