#becoming a monk<333< /div>

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i will just alwaysssss love lfc being a little cunt and martinus doing so much for him and him being ungrateful. and i dont get nearly as much of it in canon as in the beautiful medieval au<333

#ficposting#oh and also martinus being really competent and having a ton of practical skills my beloved<333#and lfc has none despite living so long in the monastery because hes spent like 95% of his life sick in bed. and he was an aristocrat befor#becoming a monk<333

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

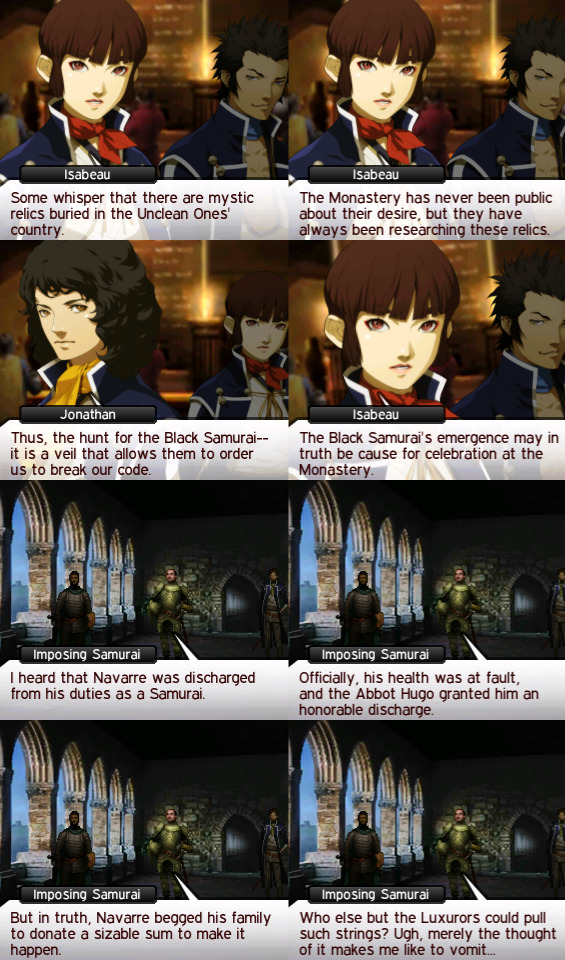

The subtle ways androgyny is used in SMTIV&A and its context in the franchise

What if I tell you... there's more characterization than it appears to be?

The most consistent trait among Megaten protagonists is certainly their androgyny. Fastidious fans would accept nothing less than the most beautiful eyelashes someone could have the privilege of being born with as it became a long defined characteristic in Kaneko's art.

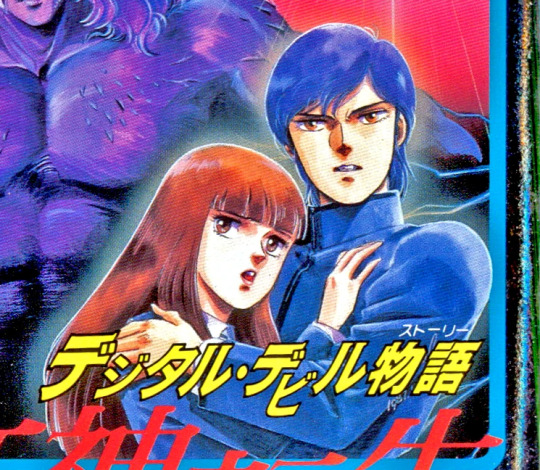

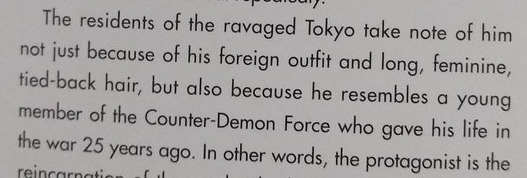

Considering the franchise debuted with a main character described as a guy that would look good in a skirt, it's no wonder Kaneko (and later, Doi) had to follow the feminine-looking boy legacy:

However, this aspect is not actually that commonly depicted as a self-aware trait in the games. Attractive? Sure. Wooing ladies? Almost always. Specifically having a spotlight on the feminine features, though? Hardly any would be at par with our originator Nakajima.

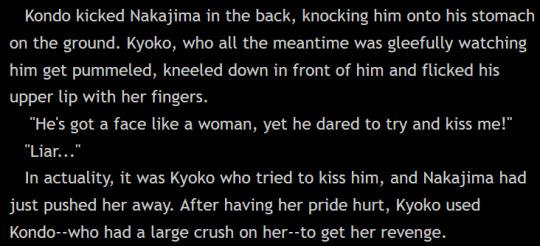

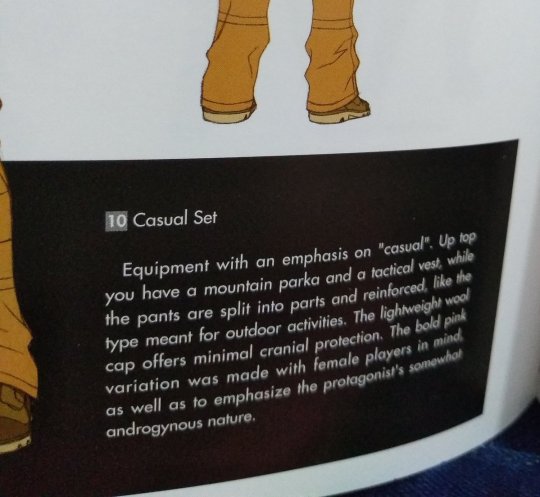

Which includes Flynn. That being said, even if it's not brought up in the story, Flynn's androgyny is still touched upon not only in his profile notes in the SMTIV Artbook...

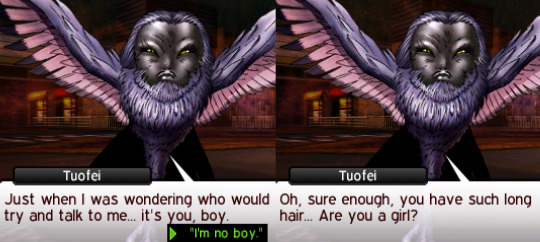

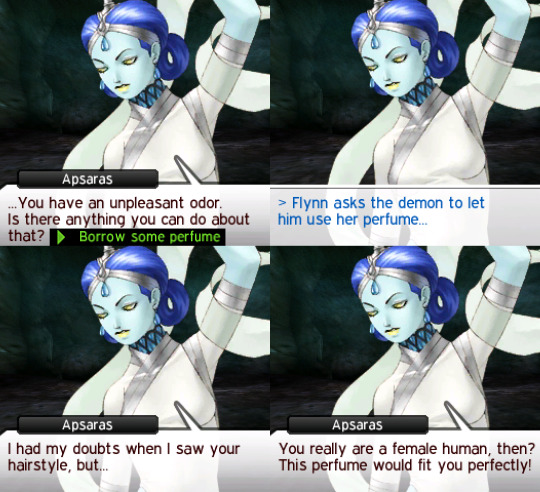

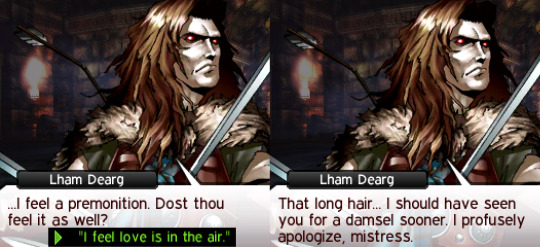

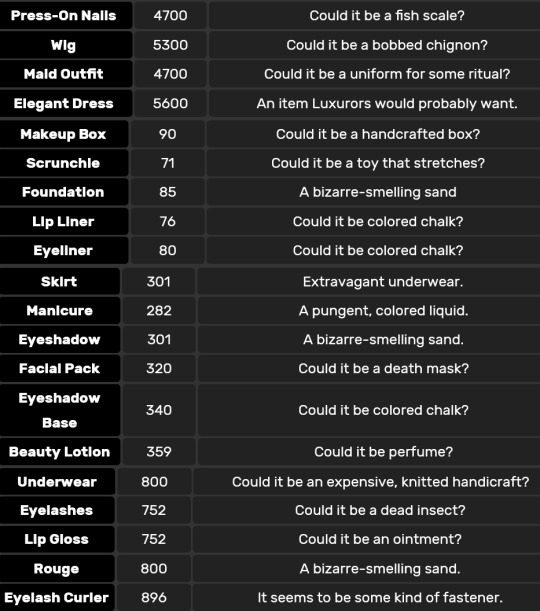

...but also in the way he's perceived in demon negotiations:

Excuse me!

Going from a stinky swordsman to bestie <333 in a flash.

Lham Dearg having this dialogue when the motherfucker shares the same hair lenght as Flynn is some double standards BS.

And then Chagrin-chan gives you a Detox solution.

However, you also have a chance of becoming a target of gender rivalry for this same answer:

No good, Chagrin-chan.

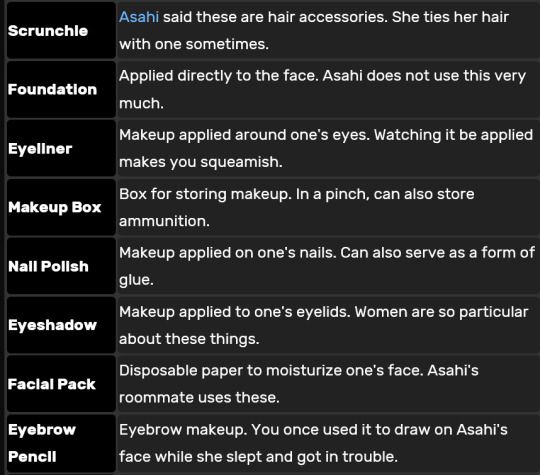

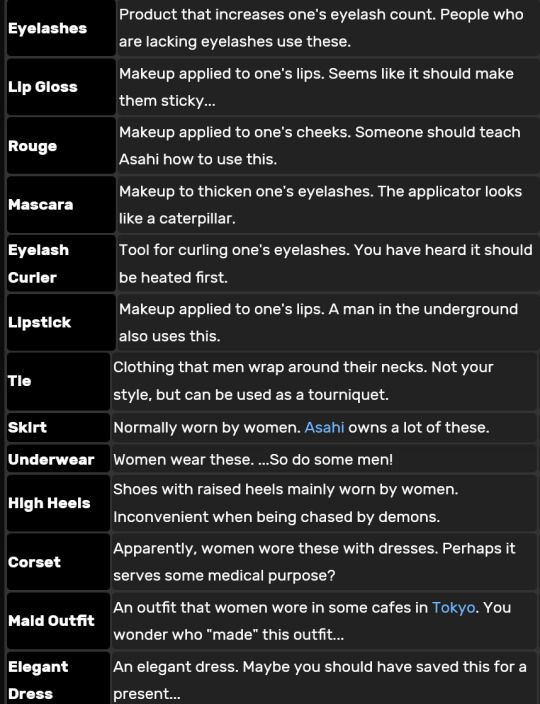

And then you have the rather unusually neutral way Flynn looks at relics:

You could argue that it’s due to Flynn being a country bumpkin born in an artificial world currently in its medieval period hence even basic concepts that he would know of would be interpreted differently when seeing their modern versions.

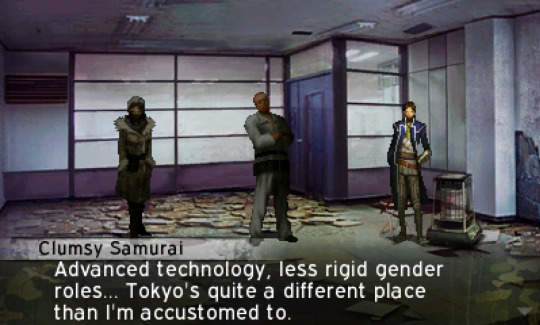

On another note, we also have to recognize that the location with the most conservative worldview is Mikado.

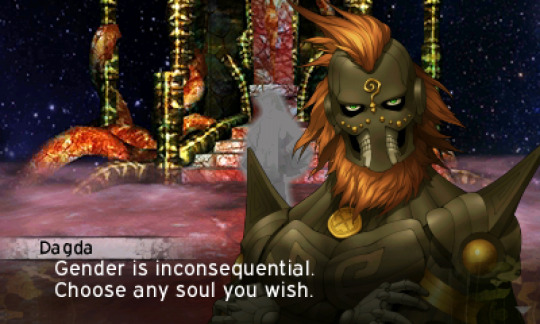

And yet, it's Nanashi the one with very gender-specific commentary:

A feasible counterpoint perhaps would lie on the possibility that Flynn didn’t grow with many women around him, specially ones that would invest in their own appearance which would be difficult considering their peasant background.

And an indoctrinated one on top of that.

Which isn't to say that there isn't makeup culture in Mikado though, as shown by Isabeau and Gabby.

Regarding Isabeau, I commented before that her choice of fashion seems to be more adapted to her own self-expression rather than a default way of presenting for either Luxurors or Samurai women. At any case, it's still part of a larger issue.

In fact, Luxurors and even monks from the Monastery weren't shown to be as anti-Unclean extremists as the Divine representatives themselves.

In the myth, Gabriel is a messenger who was entrusted to deliver several important messages on God’s behalf. Therefore, as Gabby, Gabriel acts as a mediator and makes God's message understandable to people through adapting her appearance to reach the most hearts as possible.

In other words, we have the picture of peasants being fairly ignorant of new technology (with Flynn among them) and only having the bare essentials while the higher caste thrives over luxuries to the point that becomes normalized what would be considered slightly sinful.

So much that even the angels had to tolerate it to a certain level in order to become close to humans and manipulate them.

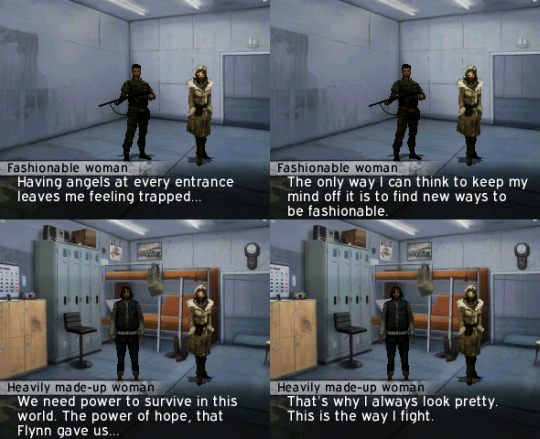

Nanashi, on the other hand, meets so many ladies worried about their appearance all over the underground that he somehow ended up knowing more than Asahi even.

So essentially, Flynn "isn't familiar with female expression" but "effortlessly passes as a woman" regardless of what he's wearing while Nanashi "knows" and "plays around" with it like a costume.

And in both cases, it seemingly comes more "at the player's choice" rather than being done in an unsolicited way.

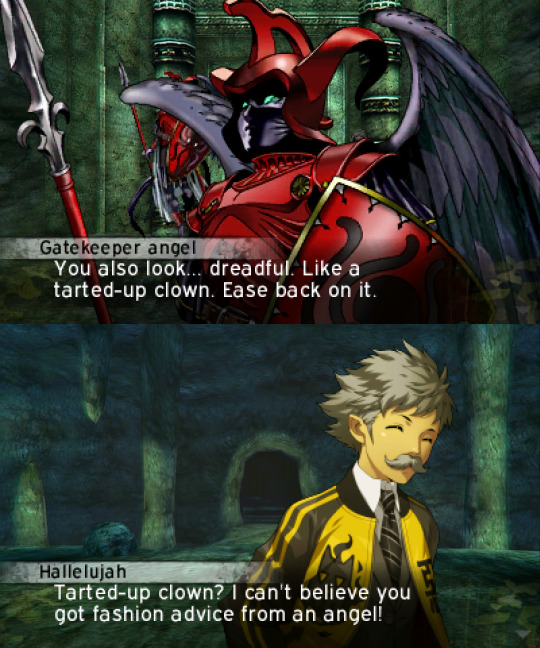

Doi's comments on SMTIVA's wardrobe convey that Nanashi is into wearing flashy clothes. Some fashionable, some dumb, some awfully absurd for anyone to wear in the middle of a war-like environment.

Nanashi basically wants to stand out. He fully knows he looks weird and is having a blast wearing flamboyant shit while fighting demons around Tokyo.

Meanwhile most of Flynn’s wardrobe are basically “gears that Flynn would consider useful for avoiding hazards while being ignorant of what the design means”.

Nanashi does it for fashion while Flynn does it for protection. This is also applied to the situations where the player "can choose" to act feminine: Nanashi crossdresses and wears make up while Flynn lets demons believe he's a woman to get a positive reaction in negotiations.

To summarize, Flynn was intended to be seen as an individual with both male and feminine traits (or the lack of both in some aspects) beyond just the stylistic choice of his androgynous design. While Nanashi is aware of gender roles and his social standing as a guy but also breaks expectations according to his own will.

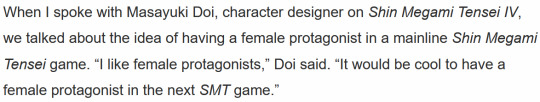

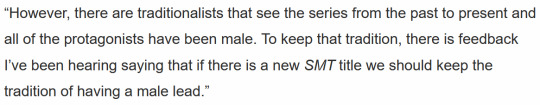

These qualities are coherent to the lore of the story while simultaneously working on a gameplay perspective, as those are ways to bring diverse options for the average player while making female players also feel 'included' even if the protagonist is a boy (as emphasized by Doi himself), which is, to this day, an unbreakable tradition in mainline games:

Somehow, it turns out that Nakajima's legacy comes in handy with a seemingly unisex-presenting main character that is able to fill the gaps of an audience.

On an ending note, while we have yet to see a more complete official breakdown of SMTV's art direction through interviews, one can understandably connect a similar reasoning for the design choices behind Nahobino.

The fanbase of the series combined with Persona has a male-to-female ratio of 40:60, to which confirms the feminine-looking boys indeed reach a bigger female audience than male.

As interesting as it is, one can't help but wonder if we would ever actually reach the other side of the gender spectrum in an actual title. We have horny mods, so there's that at least.

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

ITS MEEEE IM BACK WITH THE MILK!! THIS ADHD GIRL BACK :33

An S/O (Female) of the Monkey King's (Like reader is girlfriend of the different Monkey Kings), who acts and haves the personality of the first chapter of bfb like FOUR from Bfdi, but they have the same behaviour that Four once had when they made their first appearence in the show, yk, Powerful, Literally Destroys and screechs everything that just breathes the air in a slightly wrong way. How each one will react?

I literally love Four and X and i had to make an request about something similar to Four.

God... i imagine how troublemaker and powerful the Reader willbe with the powers of four, yet they dont know it since they are too dumb to realize (like four)

I love bfdi (Battle for dream island) <333

BTWW HII!! ITS BEEN SO LONG SINCE I REQUESTED AND SRRY, I WAS STUCK PLAYING COOKIE RUN AND STUFF...

______ (literally an interaction)

Random ahh person: "Y/N can you quit your shenanigans and help-"

*The reader lit screeches and makes them pass out*

*Wukong looking all the interaction and how their girlfriend just screeches everyone who even exists in a wrong way*

"D:"

I watched some of this and it's Hilarious and I love his character already🤣

(Lmk Wukong) this is totally him when he has to deal with you. You guys meet in the JTTW and immediately something was very unusual about you. When he aggressively Confronted you the first the thing you did was Screech at him and he woke up on the floor. He was then after that very weary of you after that. Strange things happened around Us in the group after that people even made a legend around us. Even to this day he still doesn't quite get you and your aura but he loves you for it although to the outside looking in people can sense that their is something dark about you for example Macaque and Sandy.

(MKR Wukong) Yooooooooo your Marriage is so Chaotic and Unusual that you make him For once want to be a responsible person. Your antics are so unpredictable that even The monk doesn't know your next mood. And you have stun people with your Screeching and it was funny until it happened to him. And more weird things have happened around you such as stretching your limbs, you bing able to manifest out of thin air and warp and mutilate demons from a distance. You love scaring both Pigsy and Sandy but you love Wukong and Fruity. But There is very dark thing about you and it worries the monk even after the journey.

(HIB Wukong) You....You are a terrible influence to both Luier and Silly girl Especially Silly girl. Silly girl screeches alot thanks to you and Luier is asking even more questions then ever with every Chaotic phenomena and he has to find some way to deal with it. But on the bright side You care very much for him and the kids but he always finds some interesting about you and it frightens and enlightens him.

(NR Wukong) Chaos Chaos CHAOS PEOPLE🤯🤯🤯. Wukong is tamed compared to you. From your Random Screeching to you weird quirks and abilities to the crazy sh*t you say and ask and do. He loves it but it slowly starts to disturb him because you seem to be unaware of what you can do and of what happens around you. And he if starts to get Careful and cautious of you well.... that's when Li and Su become alarmed by you as well.

(Netflix Wukong) He can match your energy like a puzzle piece. He quickly learns that you love to play games and are quite the free spirit and the best part is you never judge him on what he says and do. In fact you totally encourage it but Lin quickly points out our rather unusual life. We of course never give her a Straight answer on to what's going on but she's worried and a little suspicious of you. But As for Wukong he loves spending every day with you and loves your quirky self Sure he can do without the screeching , but he doesn't want you to ever change.

#monkey king netflix#monkey king reborn#monkey king x reader#nezha reborn#lmk monkey king#monkey king hero is back#x female y/n#battle for dream island

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a bit about me 🪒👨🦲

Good morning/evening to everyone reading this! I'm new here in this community so I thought it will be a great idea to make this post about who I am and why I am here...

Well, as the profile description says, I'm a gay man who is into bald heads and all type of hair fetishes. I'm 20yo and my taste for bald men came some years ago when I got into puberty. It was during this time when I realised how hot and sexy a shiny bald head fits on a man's head and how I would love to become bald myself in the future. I love ALL types of humiliating and degrading haircuts, actually, the day I will finally archieve my dream of becoming a shiny bald man I'd love to play a bit with my hair and making some of these haircuts like the mbp haircut or the monk one before I finally shave everything off.

I have a special affection about browless people as well, in fact, these last years I've come to the conclusion that the less hair a man has the sexier it gets. Personally I would love to shave all of the hair on my head, including beard, eyebrows and eyelashes. And it has been recently when I've thought about also shaving everything in my body too. For the past couple of years I've been shaving my legs and torso occasionally and I love the sensation it feels when rubbing them. I've already tell about this taste to some people and some of them are quite doubtful about it, like "no hair looks weird" type of stuff. But honestly, I wouldn't mind archieving this dream I've got for some time now. I would like to become a hairless being, no hair anywhere, and I would love it to feel natural (no shadows on the scalp for example). I've been thinking about getting all my hair of my head and body epilated and keeping it regularly, and looks like a great idea from my point of view.

There's a little problem tho, and it's the fact for now I couldn't do this because I'm not living alone by the time I'm writing this. Still, I've the plan of once I become fully independent I will do it, and once I have the money enough of doing it I would also have some laser surgery on my scalp and in the most parts of my body that I can... I want to have fully no hair and I would love in a closer future to become the man I'm dreaming to be. So the reason why I'm here is because I realised there are quite some people with tastes similar to mine plus some of them who have actually done all the hair removing thing and it looks fabulous on them, and, honestly, some of them have been the inspiration of me wanting to do this! So seeing all the people here who also has this same love for bald smooth heads and bodies it's my pleasure to meet all of you. And hopefully some day I will love becoming one of you! 😄

Aside from all the bald and shiny heads fetish stuff, I have other fantasies (even if that's another story to tell lol). For example I love everything related to bondage and leather, rubber, latex... (you will be surprised if I tell you I'm quite into puppy and ponyplay a bit :p) you get the point. Also about becoming a full time slave and satisfy the needs of some master... Imagine being a hairless slave succumbing to the desires of your master (and he's also no hair anywhere hehe)... Luckily I will find a boyfriend who's also into all these stuff, and we will be a couple of hairless people! 🥰

And..... yeah, I think that's all I can say for now. If you got this far I really appreciate your dedication of taking your time in reading this post. And hopefully later on I will meet new people also interested in the same fantasies and stuff as me :D

Thanks from my heart and I hope you all have a nice day! Love you all <333

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay, so a few questions actuay-:

Does Wukong ever find out about Su Daji and her relationship with his brother?

How does Erlang Shen react to SWK becoming a companion to The Great Monk?

Does he ever try to apologize to Wukong for burning down his mountain?

ROLLS ROLLS ROLLS ROLLS YES.

1.) Yes he does; it's a long... complicated thing that will be drafted out and properly written at some point but Su Daji and Erlang's relationship is very Much Wrong For several reasons. So when Wukong finds out he's doing his best not to fucking laugh bro. What fox does to a motherfucker fr

2.) Erlang is aware of it. All of Heaven is aware of it and, iirc, he is tasked with helping SWK at some point in the novel. Which is where they become sworn brothers. for the AU, this is where SWK and Erlang beat the shit out of each other for emotional reasons and then reconcile <333 the Monk watches this in absolute horror

3.) Yes. SWK didn't want to hear it. Cue infighting.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

LTtheMonk tells the story of The Intern on new album Uptown Intern #333

Originally from London, UK, LTtheMonk had an eclectic musical upbringing that set him off on a journey to becoming a musician himself. Dance is also an intrinsic part of LT’s toolkit, with bantamweight Gene Kelly-meets-James Brown footwork and immaculate sport socks both indelible signatures of his persona as an entertainer. Melding all of his influences, LT aims to fuse dance music with hip-hop and pop, to create his own unique sound.

The focus track “Reminder” from new album Uptown Intern #333 is inspired by childhood love, a first crush that no matter where you go in life, you can’t leave behind. Physically, LT describes seeing beautiful Canadian and American women that remind him of his first love back in South London, England, but metaphorically, the concept is all about that first love being the key to one’s childhood, maybe a true self that one left behind when entering adulthood. Remembering that love is meant to be a reminder of one’s true self, of keeping that childhood spirit and purity alive, no matter where you go.Uptown Intern #333 is musically inspired by the Uptown Sound, a sound defined by the New Jack Swing style that blended hip-hop, R&B and pop music, and was invented and popularized by Teddy Riley and Andre Harrell at Uptown Records in the late 80s and early 90s. Lyrically, the album tells the story of “The Intern,” the child with a love of music so pure he’ll do anything to see that love realized. Uptown Intern #333 tells the story of The Intern as he embarks on his journey Uptown, traveling through the sounds and the eras, to find his own New Monk Swing.

0 notes

Note

Heyyyy so first of all: I've been studying the Sengoku Era outside of otome for a while now and I've got to say your blog is SO mf helpful I dont think you understand. You spend your time giving detailed answers and I swear I love it to death. And I've got a little question;

Warning: Spoilers Ahead for Kenshin's Unification Arc > Divine Lover > Epilogue > Act 2 ep 3/4

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Soo basically theres this line where MC and Kenshin decide to move to Rinsenji (a temple) and MC narrates that they've decided to "enter the order there." Thing is wtf does that mean? Like, are they living as monks now? Ah. Though I do believe it was said in the later part of his route that Rinsenji was a temple where women werent allowed. Though they had traveled there together in like the first chapter of this route. If they're living as monks, does that mean they're not allowed to have kids??

Warning: what I consider to be a major spoiler ahead: (just a comment on the last part of the question above)

-

-

-

-

-

-

(Because lemme tell you. Even after "Decades have passed" there's still no mention of kiddos.)

Anyways. I understand if you can't answer this ask or if it takes a while (or if it never gets answered) -- thanks for keeping this blog up <333

Hello my good anon. Thank you for your message. I'm glad you find my posts useful.

Per the Japanese text, to my recollection the text actually says they "reside in the temple". So they just live there as something like a retirement home, and don't become monks and nuns. I am not 100% sure, since it's been 1+ year since I last read the Japanese version. I can rerun the route and check it, and I will come back with a confirmation in... a few weeks or so.

Rinsenji 林泉寺 is Soto Zen Buddhist temple, and they do segregate the monks and nuns. The temple will just have monks, and the nuns have their own nunneries. I do not think the "no women" rule applies to "house guests" who reside in the temple or temple compound without being ordained, but don't quote me on this. I am not able to find specific details on the rules.

Kids not being mentioned is a storytelling decision. This is not something I have authority to say anything about, haha. Maybe they just leave it open for later events? It does not say "they died childless" after all. They'll keep things as open-ended as they can, for as long as the game keeps running. Which we hope will be for a good long while.

Just an additional comment. The Rinsenji is significant because it was the temple Kenshin was sent to be educated in his childhood (then still called Torachiyo). Some older storytelling said that he was there to be removed from succession and become a monk, but some other versions said he was just there to study like a normal samurai child. A lot of samurai families send their sons to be educated in temples as opposed to having home tutors. Monks are highly educated, and perhaps the lords want the sons to learn discipline too.

There was a story that Kenshin almost quit his lordship to become a monk permanently (so maybe that ending is inspired by this), but he didn’t go to Rinsenji for it. He was aiming for priesthood in a Bishamonten devotee sect.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Bestie I don't know if you still want asks but. Tell me about the fantasy novel? I am very intrigued

HELL YEAH HELL YEAH HELL YEAH

*rubs hands together gleefully*

ok so there is literally. so much going on in this. there are multiple different storylines and just. ok. (putting a read more here because this is going to get. long)

So: world stuff. There are four kingdoms. There's one in the center that is kind of the main ruling kingdom, the others surrounding it are all under it (they all have rulers of their own but those rulers answer to the ruler of the central kingdom) (i'll get to him in a second). Each surrounding kingdom is dedicated to either the past, present, or future. So like the kingdom of the past is full of historians and scholars, who believe that the past is what shapes everything, that the only way to move forward is to follow the the examples set by history. The kingdom of the present is full of those who are focused on the now, the mercenaries and merchants and soldiers who believe that the most important thing is living in the moment. And in the kingdom of the future, there are the inventors, the prophets, and the beastmasters.

The beastmasters. Are certainly something. They're a type of inventor, I guess you could say. They build... creatures, out of metal and wood and whatever materials they can find. Creatures that move, that serve, that occasionally even make noise. They say it isn't magic, but no one quite believes them. No one really trusts the beastmasters.

All of these kingdoms are kind of.. well, they're a bit hostile toward each other, due to their differences. They're a ticking time bomb about to go off. Most of the hostility is aimed at the kingdom of the future, however, as most believe that the work they do there goes against the gods and their path.

The gods!! There are three gods, or one god with three faces/aspects. It depends on who you ask. Those aspects are the Judge, Jury, and Executioner. There are seperate churches and priests for each aspect, and each order has a different purpose (priests of the executioner tend to oversee war and, well, executions, they have a reputation for being quite violent).

Oh!! Also!! There are lands bordering the kingdoms. There's the Icelands, which are. Well. Full of ice. Very dangerous. There's the Wastelands, which are basically a desert. And the Woodlands!! A huge forest. It's said that any way you go through any of them, you will come to the mountain, home of three ancient seers.

now!! the characters. there are a lot so bear with me here.

So. there's the royal family, the one that rules from the central kingdom. they are:

King Reyne!! Reyne is. So so dear to me. He's neurodivergent and has an anxiety disorder (projecting time babey) that often affects him worse than he lets on. He's super insecure about his ability to rule, and he's under a lot of stress right now due to the growing hostility between the kingdoms i mentioned earlier. But he's an incredible king and a really good guy, just in general.

Queen Lilah!! Reyne's wife. They were an arranged marriage, and while the two of them are not romantically involved, they love each other very much and Lilah is a strong support for Reyne. She's also a badass. Will beat you up if you insult anyone she cares about. Has a bit of a temper (understatement of the century)

Matti!!! Mathias. Prince Mathias. Reyne and Lilah's son, heir to the throne. He takes after his father a lot. He's very curious and has trouble letting things go. He becomes convinced that someone's trying to betray his parents and the kingdom, and that.. kind of consumes him. I'm so excited to write him he has a brilliant storyline.

Ok and then there's the other people involved with the above family!!

RHYS. RHYSANDER FLORENT BLACKWOOD MY ABSOLUTE BELOVED. The king's advisor (and boyfriend), a total sweetheart with something of an edge to him. He, Reyne, and Lilah have this little chosen family thing going on that's really sweet. They're all each other's support and strength.

Silverfish. Silver is... the queen's spy, gatherer of information, sometimes gives advice too. Lilah wants it to also do assassinations, but it refuses to kill (will give the order to kill, but will not do the killing itself). No one really knows where Silver came from, and most don't trust it, but Lilah does. It never lies.

Alright moving on to other storylines: so y'know how no one likes the kingdom of the future? yeah, that's currently much worse due to some strange and unexplained happenings throughout all four kingdoms. Everyone thinks that it's the kingdom of the future angering the gods. So Reyne sends out a team to investigate these happenings peacefully, made up of a beastmaster from the kingdom of the future (he's cool. has an eyepatch. acts kinda bossy and like xe's in charge. a bit of an asshole, but genuinely cares), a knight from the kingdom of the present (trans woman. can and will kill you if you talk shit about her. has a wife. she's literally the coolest), and a historian from the kingdom of the past (Loren!! Loren is babey. the youngest member of the team, hasn't been in a fight in their life. unlike most of their fellow historians, doesn't hate the kingdom of the future and actually uses some of their technology in their archives (trained clockwork ravens, babey!!)). These guys get into so much shit.

Meanwhile, in the mysterious prison pit of despair run by knife monks: it's a prison. it's a pit. run by spooky dudes in hoods who sometimes take the prisoners and train them in their ways. There's a princess there, imprisoned for the massacre of her family (which she insists she had no part in). She's stuck with an annoying cellmate, a thief who broke into the prison just to see if she could. They're trying to get out.

And finally. there is Faraday. Faraday... is a prophet. He travels around preaching that the gods are dead and that the people must learn to take their fates into their own hands. No one likes that. He's wanted in literally every town everywhere. He's determined to prove that he's right, and believes in himself fully. Everything he says could potentially be true or false. No one knows. Probably not even me. He's. I'm so excited to work with him he's so fun. Has a little genderfluid bard that follows him around, hoping for a good story out of it (Ridley my belidly).

Those are.. the basics. But there is a lot. But I love it so much and I'm so excited about it and aaa thank you EVER so much for letting me ramble about this it means the world to me (and so do you) <333

#asks#beloved frens#long post#my writing#ocs#my ocs#original characters#original writing#novel#fantasy#novel concept#rambles

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strength in Numbers

Warmth filled their bodies as they cuddled close together, sipping hot tea from their mugs as they leaned together. Chuntao snuggled against intertwined feet, curled into a snuggly ball of cinnamon as the two elves simply enjoyed being near each other. Nymaraei’s head leaned on the Sentinel’s shoulder, lifting every so often to take a sip of tea. Happiness filled her veins with a cozy spirit more than the beverage ever could. Outside, the Mother Moon took over the sky, her star followers dotting the sky and coaching the creatures outside to sing in a peaceful harmony. A yawn overtook the young elf who finally set down the empty mug, retrieving Rhenelle’s as well and setting them to the ground. A task for the morning. The monk left soft kisses along the warrior’s cheek and jaw before they snuggled under the covers and drifted to sleep among their own sweet nothings and those of the life outside.

The plate-clad Captain turned to her soldiers, all lined behind her. “Tonight, ladies. Tonight we make the Horde pay for what they’ve done. Hold the line. Stay steadfast.” The soldiers all saluted in unison as the horizon became speckled with the forces of the attacking enemies. Varied heights formed the line: Sin’dorei, Orcs, Forsaken… The line went on and on, matched by the impressive line of command that Captain Rhenelle had herself. Kaldorei and Humans stood side by side with Dwarves and Gnomes that had come to fight. A battle would happen here and it electrified the air around them, the unsavory promise of bloodshed hanging ominously over the armies. The line of Horde stormed closer and closer, their war cries becoming louder and louder as the thunderous line approached. Rhen stood strong, chin tipped up in defiance. She would not waver. She never did. Her fist was balled in the air, holding her line still. Nearer and nearer the intimidating military came before finally the warrior’s hand snapped to her side and those at her back stormed forward.

The two competing forces clashed together in the middle of the field, fighting erupting like lava over the crowd. Metal on metal clanged into the air, war cries and screams filling the air that wasn’t yet occupied by the sounds of pure war. Rhenelle charged into battle, coming to the assistance of her allies who were already engaged in heavy fights. Slowly, as the battle raged on, both friend and foe began to fall, tumbling with defeat to the ground. Rain began to pour from the sky as if in attempt to cleanse the ground of the impurity of war that had raged. As her numbers dwindled and those of the Horde seemed to falter only slightly, an unsettling weight began to sit on the Captain’s stomach. She stood, helpless, as she watched the final numbers of her forces fall, slain. She tried to rush forward but to no avail; She couldn’t move. Panic swirled itself up her legs before seizing her entire body. Behind her, the sound of feet rushing into an onslaught had her whipping about, attempting to warn her allies to turn back. No sound came from her, no movement, nothing. She was held still by invisible binds. Finally, those that had come to her rescue broke her field of vision and the weight that sat upon her increased exponentially.

Everyone she loved or cared about. The ethereal Priestess Ne’suna charged forward atop her saber Breesia, bounding gallantly to war. Beside her, another elf appeared on her own thunderous beast… Nymaraei. And alongside them, more and more of her friends, family, acquaintances even charged forward into a certain defeat. And yet, she could do nothing but watch.

Rhenelle had been tossing and turning in her sleep before jolting upright. Sweat coated her face and matted her hair down as she breathed heavily, nearly gasping for air. She twisted in bed, searching the bed for… Nymaraei. Nyma, feeling the panicked movements of the sleeping and now awakened sentinel, began hushing the Sentinel, immediately sitting up against the wall behind the bed and hugging the frightened warrior to her. Carefully, she’d soothe Rhen, brushing her hair away from her face with soft coos to calm her spirits. The contents of the nightmare that had awoken her were conversation for tomorrow. All Nymaraei wanted was for her to settle. As Rhenelle finally began to calm down, catching her breath, Nym would reach under the edge of the bed, grabbing a familiar box and pulling it into her lap. A gorgeous and expertly crafted kalimba rest in her lap, the tines catching the moonlight and gleaming it across the ceiling.

Nym gestured for Rhen to relax, placing a pillow across her lap and allowing the warrior to rest her head. With a deep breath, the monk began plucking at the metal tines, a peaceful harmony beginning to form. The lullabye drifted around the couple, combining with the soft humming of the monk and the chorus of nocturnal creatures outside. Slowly, Rhen would drift back to sleep, at peace. Midnight blue hair splayed out across the pillow as Nym gazed down at it, continuing to play the melody long after her crush had fallen into the soft embrace of rest. Satisfied that Rhenelle would not awake again, she let herself drift to sleep as well, leaning her head back against the wall. An arm draped over the warrior and a hand rest over the top of the kalimba that lay on the other side of her lap.

mentions: @rhenelle-nightblade obvi. thank you again for letting me channel rhen for this. <333 and the ever lovely @nesuna-nightwinter

#nymaraei mossflower#rp story#headcanon#kalimba#songs for the troubled soul#warcraft rp#warcraft monk#NYMAS GOT A GIRLFRIENDDDDD

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

1, 4, 13, And 29! For avian and cricket, and others if you want to!

I’m gonna do all of them >;3c thank youuuuuuuuuu <333

1. How many dead parents do they have?

THANK YOU THIS IS MY FAVOURITE QUESTION and tbh I haven’t really thought much about parents.

Avian: Neither are confirmed dead but both of them went missing on the same outing to get (read: steal) stock for their traveling shop. Are they really dead? Are they trapped in a dungeon somewhere? Or were they arrested and thrown in jail because they were a couple who had a half-elf child but still remained together in a loving relationship? Who knows??

Cricket: I think they’re both still alive… ?? Maybe I should ask Griffin

Koden: Both are still alive but his father works in the city and doesn’t come home much.

Alicia: Both are dead. Her mother died during childbirth and her father died while she was in high school.

4. Are they formally trained or have they gone through a more organic learning experience for their skillset?

Avian: Ok so Avian multi-classes as a rogue/soul reaper. For her rogue stuff she had absolutely no training. Her dad tried to teach her to fight long ago and she ended up with a big-ass scar on her nose and a “wow you really suck at fighting, you should just work the store.” And wow did she really suck at fighting, she died both times our campaign actually had to fight (even the goblins. And she almost died in the local town because she spooked a guard and he choked her. Fun times). She was awful and doesn’t deserve any levels of her rogue skill AT ALL. She did receive training for her reaper skills though, that was required.

Cricket: No training, Their’s flying by the seat of their pants.

Koden: I guess organic unless you count a goddess occasionally leaning over your shoulder and saying “fuck it up” when you’re trying to do something else that’s important.

Alicia: Again, another multi-classer. She has absolutely no training for her sorcerer levels but she trained with Morgane to get her monk levels very similar to how Magnus trained with Carey to get his Rogue levels.

13. If they can use magic, what’s their favorite spell?

Already done

29. Biggest positive and negative influences on their life and development?

oooohhhhh this is a really good question! I like it a lot!

Avian:

Positive: When she got both of her connections with the Raven Queen. The first was the “never dying” blessing/curse, the second was getting a job as a grim reaper.

Negative: uhhh a ton. But for sure her largest negative was when her adventuring party split up (and this is real shit that happened on the last day of our campaign because it was a school club). They’d been arguing for a while now and had just left the town to do another job. When the party was out of ear-shot of the town Lynch, Avian’s girlfriend, a hot-headed human fighter, just fucking SCREAMED and yelled “Fuck it! Fuck it all! Just fight me right now!! I’ll kill you!!” And the team’s local cleric stepped up to the fight, placed a single thumb on Lynch’s forehead and rolled a 20 on “Inflict Wounds.” Lynch immediately slumped to the ground, dead. The party ran in different directions. Yeah, that fucked Avian right up.

Cricket

Positive: It’s between two and both have to do with bonding with their siblings. The first is spending afternoons going to the field with Carey and practicing their magic and gossiping about things and just genuinely having fun. The other was when Jeremy came back home for a weekend after first leaving the family but coming back as Scales. Cricket went “holy fuck you can do that! :0 I’m not Tilly anymore, I’m Cricket, I’m 19 and I’m gonna become an adventurer tomorrow! And I’m non-binary.”

Negative: This is why I’m scared of Cricket being a mary-sue, I have nothing all that negative for them because I haven’t had the opportunity to play them yet. Maybe their diagnosis of having cerebral palsy?? But that’s just a part of who they are and isn’t really a bad thing so *big old shrug emoji*

Koden:

Positive: Saved his sister

Negative: Sold his soul to an evil goddess to do the positive thing

Alicia:

Positive: Getting accepted into university, finding a consistant adventuring party and getting consistant work with them, joining the BOB (whoops she’s another fan character)

Negative: *bass boosted Wonderland Round 3 by Griffin McElroy*

1 note

·

View note

Photo

4th Century Pilgrim Route – and NO NAZARETH! Itinerarium Burdigalense – the Itinerary of the Anonymous Pilgrim of Bordeaux – is the earliest description left by a pious tourist. It is dated to 333 AD. The itinerary is a Roman-style list of towns and distances with the occasional comment. As the pilgrim passes Jezreel (Stradela) he mentions King Ahab and Goliath. At Aser (Teyasir) he mentions Job. At Neopolis his reference is to Mount Gerizim, Abraham, Joseph, and Jacob's well at Sichar (where JC 'asked water of a Samaritan woman'). He passes the village of Bethel (Beitin) and mentions Jacob's wrestling match with God, and Jeroboam. He moves on to Jerusalem.Our pilgrim – preoccupied with Old rather than New Testament stories – makes no single reference to 'Nazareth.'A generation after the dowager empress had gone touring, another geriatric grandee, the Lady Egeria, spent years. in the 'Land becoming more Holy by the day'. Egeria – a Spaniard, like the then Emperor Theodosius and almost certainly part of the imperial entourage – reached the Nazareth area in 383. This time, canny monks showed her a 'big and very splendid cave' and gave the assurance that this was where Mary had lived. The Custodians of the Cave, not to be outbid by the Keepers of the Well, insisted that the cave, not the well, had been the site of the divine visitation. This so-called 'grotto' became another pilgrimage attraction, over which – by 570 – rose the basilica of another church. Today, above and about the Venerable Grotto, stands the biggest Christian theme park in the Middle East. https://www.jesusneverexisted.com/nazareth.html

0 notes

Text

Dhammapada. Introduction.

From ancient times to the present, the Dhammapada has been regarded as the most succinct expression of the Buddha's teaching found in the Pali canon and the chief spiritual testament of early Buddhism. In the countries following Theravada Buddhism, such as Sri Lanka, Burma and Thailand, the influence of the Dhammapada is ubiquitous. It is an ever-fecund source of themes for sermons and discussions, a guidebook for resolving the countless problems of everyday life, a primer for the instruction of novices in the monasteries. Even the experienced contemplative, withdrawn to forest hermitage or mountainside cave for a life of meditation, can be expected to count a copy of the book among his few material possessions. Yet the admiration the Dhammapada has elicited has not been confined to avowed followers of Buddhism. Wherever it has become known its moral earnestness, realistic understanding of human life, aphoristic wisdom and stirring message of a way to freedom from suffering have won for it the devotion and veneration of those responsive to the good and the true.

The expounder of the verses that comprise the Dhammapada is the Indian sage called the Buddha, an honorific title meaning "the Enlightened One" or "the Awakened One." The story of this venerable personage has often been overlaid with literary embellishment and the admixture of legend, but the historical essentials of his life are simple and clear. He was born in the sixth century B.C., the son of a king ruling over a small state in the Himalayan foothills, in what is now Nepal. His given name was Siddhattha and his family name Gotama (Sanskrit: Siddhartha Gautama) . Raised in luxury, groomed by his father to be the heir to the throne, in his early manhood he went through a deeply disturbing encounter with the sufferings of life, as a result of which he lost all interest in the pleasures and privileges of rulership. One night, in his twenty-ninth year, he fled the royal city and entered the forest to live as an ascetic, resolved to find a way to deliverance from suffering. For six years he experimented with different systems of meditation and subjected himself to severe austerities, but found that these practices did not bring him any closer to his goal. Finally, in his thirty-fifth year, while sitting in deep meditation beneath a tree at Gaya, he attained Supreme Enlightenment and became, in the proper sense of the title, the Buddha, the Enlightened One. Thereafter, for forty-five years, he traveled throughout northern India, proclaiming the truths he had discovered and founding an order of monks and nuns to carry on his message. At the age of eighty, after a long and fruitful life, he passed away peacefully in the small town of Kusinara, surrounded by a large number of disciples.

To his followers, the Buddha is neither a god, a divine incarnation, or a prophet bearing a message of divine revelation, but a human being who by his own striving and intelligence has reached the highest spiritual attainment of which man is capable — perfect wisdom, full enlightenment, complete purification of mind. His function in relation to humanity is that of a teacher — a world teacher who, out of compassion, points out to others the way to Nibbana (Sanskrit: Nirvana), final release from suffering. His teaching, known as the Dhamma, offers a body of instructions explaining the true nature of existence and showing the path that leads to liberation. Free from all dogmas and inscrutable claims to authority, the Dhamma is founded solidly upon the bedrock of the Buddha's own clear comprehension of reality, and it leads the one who practices it to that same understanding — the knowledge which extricates the roots of suffering.

The title "Dhammapada" which the ancient compilers of the Buddhist scriptures attached to our anthology means portions, aspects, or sections of Dhamma. The work has been given this title because, in its twenty-six chapters, it spans the multiple aspects of the Buddha's teaching, offering a variety of standpoints from which to gain a glimpse into its heart. Whereas the longer discourses of the Buddha contained in the prose sections of the Canon usually proceed methodically, unfolding according to the sequential structure of the doctrine, the Dhammapada lacks such a systematic arrangement. The work is simply a collection of inspirational or pedagogical verses on the fundamentals of the Dhamma, to be used as a basis for personal edification and instruction. In any given chapter several successive verses may have been spoken by the Buddha on a single occasion, and thus among themselves will exhibit a meaningful development or a set of variations on a theme. But by and large, the logic behind the grouping together of verses into a chapter is merely the concern with a common topic. The twenty-six chapter headings thus function as a kind of rubric for classifying the diverse poetic utterances of the Master, and the reason behind the inclusion of any given verse in a particular chapter is its mention of the subject indicated in the chapter's heading . In some cases (Chapters 4 and 23) this may be a metaphorical symbol rather than a point of doctrine. There also seems to be no intentional design in the order of the chapters themselves, though at certain points a loose thread of development can be discerned.

The teachings of the Buddha, viewed in their completeness, all link together into a single perfectly coherent system of thought and practice which gains its unity from its final goal, the attainment of deliverance from suffering. But the teachings inevitably emerge from the human condition as their matrix and starting point, and thus must be expressed in such a way as to reach human beings standing at different levels of spiritual development, with their highly diverse problems, ends, and concerns and with their very different capacities for understanding. Thence, just as water, though one in essence, assumes different shapes due to the vessels into which it is poured, so the Dhamma of liberation takes on different forms in response to the needs of the beings to be taught. This diversity, evident enough already in the prose discourses, becomes even more conspicuous in the highly condensed, spontaneous and intuitively charged medium of verse used in the Dhammapada. The intensified power of delivery can result in apparent inconsistencies which may perplex the unwary. For example, in many verses the Buddha commends certain practices on the grounds that they lead to a heavenly birth, but in others he discourages disciples from aspiring for heaven and extols the one who takes no delight in celestial pleasures (187, 417) [Unless chapter numbers are indicated, all figures enclosed in parenthesis refer to verse numbers of the Dhammapada.]

Often he enjoins works of merit, yet elsewhere he praises the one who has gone beyond both merit and demerit (39, 412). Without a grasp of the underlying structure of the Dhamma, such statements viewed side by side will appear incompatible and may even elicit the judgment that the teaching is self-contradictory.

The key to resolving these apparent discrepancies is the recognition that the Dhamma assumes its formulation from the needs of the diverse persons to whom it is addressed, as well as from the diversity of needs that may co-exist even in a single individual. To make sense of the various utterances found in the Dhammapada, we will suggest a schematism of four levels to be used for ascertaining the intention behind any particular verse found in the work, and thus for understanding its proper place in the total systematic vision of the Dhamma. This fourfold schematism develops out of an ancient interpretive maxim which holds that the Buddha's teaching is designed to meet three primary aims: human welfare here and now, a favorable rebirth in the next life, and the attainment of the ultimate good. The four levels are arrived at by distinguishing the last aim into two stages: path and fruit.

(i) The first level is the concern with establishing well-being and happiness in the immediately visible sphere of concrete human relations. The aim at this level is to show man the way to live at peace with himself and his fellow men, to fulfill his family and social responsibilities, and to restrain the bitterness, conflict and violence which infect human relationships and bring such immense suffering to the individual, society, and the world as a whole. The guidelines appropriate to this level are largely identical with the basic ethical injunctions proposed by most of the great world religions, but in the Buddhist teaching they are freed from theistic moorings and grounded upon two directly verifiable foundations: concern for one's own integrity and long-range happiness and concern for the welfare of those whom one's actions may affect (129-132). The most general counsel the Dhammapada gives is to avoid all evil, to cultivate good and to cleanse one's mind (183). But to dispel any doubts the disciple might entertain as to what he should avoid and what he should cultivate, other verses provide more specific directives. One should avoid irritability in deed, word and thought and exercise self-control (231-234). One should adhere to the five precepts, the fundamental moral code of Buddhism, which teach abstinence from destroying life, from stealing, from committing adultery, from speaking lies and from taking intoxicants; one who violates these five training rules "digs up his own root even in this very world" (246-247). The disciple should treat all beings with kindness and compassion, live honestly and righteously, control his sensual desires, speak the truth and live a sober upright life, diligently fulfilling his duties, such as service to parents, to his immediate family and to those recluses and brahmans who depend on the laity for their maintenance (332-333).

A large number of verses pertaining to this first level are concerned with the resolution of conflict and hostility. Quarrels are to be avoided by patience and forgiveness, for responding to hatred by further hatred only maintains the cycle of vengeance and retaliation. The true conquest of hatred is achieved by non-hatred, by forbearance, by love (4-6). One should not respond to bitter speech but maintain silence (134). One should not yield to anger but control it as a driver controls a chariot (222). Instead of keeping watch for the faults of others, the disciple is admonished to examine his own faults, and to make a continual effort to remove his impurities just as a silversmith purifies silver (50, 239). Even if he has committed evil in the past, there is no need for dejection or despair; for a man's ways can be radically changed, and one who abandons the evil for the good illuminates this world like the moon freed from clouds (173).

The sterling qualities distinguishing the man of virtue are generosity, truthfulness, patience, and compassion (223). By developing and mastering these qualities within himself, a man lives at harmony with his own conscience and at peace with his fellow beings. The scent of virtue, the Buddha declares, is sweeter than the scent of all flowers and perfumes (55-56). The good man, like the Himalaya mountains, shines from afar, and wherever he goes he is loved and respected (303-304).

(ii) In its second level of teaching, the Dhammapada shows that morality does not exhaust its significance in its contribution to human felicity here and now, but exercises a far more critical influence in molding personal destiny. This level begins with the recognition that, to reflective thought, the human situation demands a more satisfactory context for ethics than mere appeals to altruism can provide. On the one hand our innate sense of moral justice requires that goodness be recompensed with happiness and evil with suffering; on the other our typical experience shows us virtuous people beset with hardships and afflictions and thoroughly bad people riding the waves of fortune (119-120). Moral intuition tells us that if there is any long-range value to righteousness, the imbalance must somehow be redressed. The visible order does not yield an evident solution, but the Buddha's teaching reveals the factor needed to vindicate our cry for moral justice in an impersonal universal law which reigns over all sentient existence. This is the law of kamma (Sanskrit: karma), of action and its fruit, which ensures that morally determinate action does not disappear into nothingness but eventually meets its due retribution, the good with happiness, the bad with suffering.

In the popular understanding kamma is sometimes identified with fate, but this is a total misconception utterly inapplicable to the Buddhist doctrine. Kamma means volitional action, action springing from intention, which may manifest itself outwardly as bodily deeds or speech, or remain internally as unexpressed thoughts, desires and emotions. The Buddha distinguishes kamma into two primary ethical types: unwholesome kamma, action rooted in mental states of greed, hatred and delusion; and wholesome kamma, action rooted in mental states of generosity or detachment, goodwill and understanding. The willed actions a person performs in the course of his life may fade from memory without a trace, but once performed they leave subtle imprints on the mind, seeds with the potential to come to fruition in the future when they meet conditions conducive to their ripening.

The objective field in which the seeds of kamma ripen is the process of rebirths called samsara. In the Buddha's teaching, life is not viewed as an isolated occurrence beginning spontaneously with birth and ending in utter annihilation at death. Each single life span is seen, rather, as part of an individualized series of lives having no discoverable beginning in time and continuing on as long as the desire for existence stands intact. Rebirth can take place in various realms. There are not only the familiar realms of human beings and animals, but ranged above we meet heavenly worlds of greater happiness, beauty and power, and ranged below infernal worlds of extreme suffering.

The cause for rebirth into these various realms the Buddha locates in kamma, our own willed actions. In its primary role, kamma determines the sphere into which rebirth takes place, wholesome actions bringing rebirth in higher forms, unwholesome actions rebirth in lower forms. After yielding rebirth, kamma continues to operate, governing the endowments and circumstances of the individual within his given form of existence. Thus, within the human world, previous stores of wholesome kamma will issue in long life, health, wealth, beauty and success; stores of unwholesome kamma in short life, illness, poverty, ugliness and failure.

Prescriptively, the second level of teaching found in the Dhammapada is the practical corollary to this recognition of the law of kamma, put forth to show human beings, who naturally desire happiness and freedom from sorrow, the effective means to achieve their objectives. The content of this teaching itself does not differ from that presented at the first level; it is the same set of ethical injunctions for abstaining from evil and for cultivating the good. The difference lies in the perspective from which the injunctions are issued and the aim for the sake of which they are to be taken up. The principles of morality are shown now in their broader cosmic connections, as tied to an invisible but all-embracing law which binds together all life and holds sway over the repeated rotations of the cycle of birth and death. The observance of morality is justified, despite its difficulties and apparent failures, by the fact that it is in harmony with that law, that through the efficacy of kamma, our willed actions become the chief determinant of our destiny both in this life and in future states of becoming. To follow the ethical law leads upwards — to inner development, to higher rebirths and to richer experiences of happiness and joy. To violate the law, to act in the grip of selfishness and hate, leads downwards — to inner deterioration, to suffering and to rebirth in the worlds of misery. This theme is announced already by the pair of verses which opens the Dhammapada, and reappears in diverse formulations throughout the work (see, e.g., 15-18, 117-122, 127, 132-133, Chapter 22).

(iii) The ethical counsel based on the desire for higher rebirths and happiness in future lives is not the final teaching of the Buddha, and thus cannot provide the decisive program of personal training commended by the Dhammapada. In its own sphere of application, it is perfectly valid as a preparatory or provisional teaching for those whose spiritual faculties are not yet ripe but still require further maturation over a succession of lives. A deeper, more searching examination, however, reveals that all states of existence in samsara, even the loftiest celestial abodes, are lacking in genuine worth; for they are all inherently impermanent, without any lasting substance, and thus, for those who cling to them, potential bases for suffering. The disciple of mature faculties, sufficiently prepared by previous experience for the Buddha's distinctive exposition of the Dhamma, does not long even for rebirth among the gods. Having understood the intrinsic inadequacy of all conditioned things, his focal aspiration is only for deliverance from the ever-repeating round of births. This is the ultimate goal to which the Buddha points, as the immediate aim for those of developed faculties and also as the long-term ideal for those in need of further development: Nibbana, the Deathless, the unconditioned state where there is no more birth, aging and death, and no more suffering.

The third level of teaching found in the Dhammapada sets forth the theoretical framework and practical discipline emerging out of the aspiration for final deliverance. The theoretical framework is provided by the teaching of the Four Noble Truths (190-192, 273), which the Buddha had proclaimed already in his first sermon and upon which he placed so much stress in his many discourses that all schools of Buddhism have appropriated them as their common foundation. The four truths all center around the fact of suffering (dukkha), understood not as mere experienced pain and sorrow, but as the pervasive unsatisfactoriness of everything conditioned (202-203). The first truth details the various forms of suffering — birth, old age, sickness and death, the misery of unpleasant encounters and painful separations, the suffering of not obtaining what one wants. It culminates in the declaration that all constituent phenomena of body and mind, "the aggregates of existence" (khandha), being impermanent and substanceless, are intrinsically unsatisfactory. The second truth points out that the cause of suffering is craving (tanha), the desire for pleasure and existence which drives us through the round of rebirths, bringing in its trail sorrow, anxiety, and despair (212-216, Chapter 24). The third truth declares that the destruction of craving issues in release from suffering, and the fourth prescribes the means to gain release, the Noble Eightfold Path: right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration (Chapter 20).

If, at this third level, the doctrinal emphasis shifts from the principles of kamma and rebirth to the Four Noble Truths, a corresponding shift in emphasis takes place in the practical sphere as well. The stress now no longer falls on the observation of basic morality and the cultivation of wholesome attitudes as a means to higher rebirths. Instead it falls on the integral development of the Noble Eightfold Path as the means to uproot the craving that nurtures the process of rebirth itself. For practical purposes the eight factors of the path are arranged into three major groups which reveal more clearly the developmental structure of the training: moral discipline (including right speech, right action and right livelihood), concentration (including right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration), and wisdom (including right understanding and right thought). By the training in morality, the coarsest forms of the mental defilements, those erupting as unwholesome deeds and words, are checked and kept under control. By the training in concentration the mind is made calm, pure and unified, purged of the currents of distractive thoughts. By the training in wisdom the concentrated beam of attention is focused upon the constituent factors of mind and body to investigate and contemplate their salient characteristics. This wisdom, gradually ripened, climaxes in the understanding that brings complete purification and deliverance of mind.

In principle, the practice of the path in all three stages is feasible for people in any walk of life. The Buddha taught it to laypeople as well as to monks, and many of his lay followers reached high stages of attainment. However, application to the development of the path becomes most fruitful for those who have relinquished all other concerns in order to devote themselves wholeheartedly to spiritual training, to living the "holy life" (brahmacariya). For conduct to be completely purified, for sustained contemplation and penetrating wisdom to unfold without impediments, adoption of a different style of life becomes imperative, one which minimizes distractions and stimulants to craving and orders all activities around the aim of liberation. Thus the Buddha established the Sangha, the order of monks and nuns, as the special field for those ready to dedicate their lives to the practice of his path, and in the Dhammapada the call to the monastic life resounds throughout.

The entry-way to the monastic life is an act of radical renunciation. The thoughtful, who have seen the transience and hidden misery of worldly life, break the ties of family and social bonds, abandon their homes and mundane pleasures, and enter upon the state of homelessness (83, 87-89, 91). Withdrawn to silent and secluded places, they seek out the company of wise instructors, and guided by the rules of the monastic training, devote their energies to a life of meditation. Content with the simplest material requisites, moderate in eating, restrained in their senses, they stir up their energy, abide in constant mindfulness and still the restless waves of thoughts (185, 375). With the mind made clear and steady, they learn to contemplate the arising and falling away of all formations, and experience thereby "a delight that transcends all human delights," a joy and happiness that anticipates the bliss of the Deathless (373-374). The life of meditative contemplation reaches its peak in the development of insight (vipassana), and the Dhammapada enunciates the principles to be discerned by insight-wisdom: that all conditioned things are impermanent, that they are all unsatisfactory, that there is no self or truly existent ego entity to be found in anything whatsoever (277-279). When these truths are penetrated by direct experience, the craving, ignorance and related mental fetters maintaining bondage break asunder, and the disciple rises through successive stages of realization to the full attainment of Nibbana.

(iv) The fourth level of teaching in the Dhammapada provides no new disclosure of doctrine or practice, but an acclamation and exaltation of those who have reached the goal. In the Pali canon the stages of definite attainment along the way to Nibbana are enumerated as four. At the first, called "stream-entry" (sotapatti), the disciple gains his first glimpse of "the Deathless" and enters irreversibly upon the path to liberation, bound to reach the goal in seven lives at most. This achievement alone, the Dhammapada declares, is greater than lordship over all the worlds (178). Following stream-entry come two further stages which weaken and eradicate still more defilements and bring the goal increasingly closer to view. One is called the stage of once-returner (sakadagami), when the disciple will return to the human world at most only one more time; the other the stage of non-returner (anagami), when he will never come back to human existence but will take rebirth in a celestial plane, bound to win final deliverance there. The fourth and final stage is that of the arahant, the Perfected One, the fully accomplished sage who has completed the development of the path, eradicated all defilements and freed himself from bondage to the cycle of rebirths. This is the ideal figure of early Buddhism and the supreme hero of the Dhammapada. Extolled in Chapter 7 under his own name and in Chapter 26 (385-388, 396-423) under the name brahmana, "holy man," the arahant serves as a living demonstration of the truth of the Dhamma. Bearing his last body, perfectly at peace, he is the inspiring model who shows in his own person that it is possible to free oneself from the stains of greed, hatred and delusion, to rise above suffering, to win Nibbana in this very life.

The arahant ideal reaches its optimal exemplification in the Buddha, the promulgator and master of the entire teaching. It was the Buddha who, without any aid or guidance, rediscovered the ancient path to deliverance and taught it to countless others. His arising in the world provides the precious opportunity to hear and practice the excellent Dhamma (182, 194). He is the giver and shower of refuge (190-192), the Supreme Teacher who depends on nothing but his own self-evolved wisdom (353). Born a man, the Buddha always remains essentially human, yet his attainment of Perfect Enlightenment elevates him to a level far surpassing that of common humanity. All our familiar concepts and modes of knowing fail to circumscribe his nature: he is trackless, of limitless range, free from all worldliness, the conqueror of all, the knower of all, untainted by the world (179, 180, 353).

Always shining in the splendor of his wisdom, the Buddha by his very being, confirms the Buddhist faith in human perfectibility and consummates the Dhammapada's picture of man perfected, the arahant.

The four levels of teaching just discussed give us the key for sorting out the Dhammapada's diverse utterances on Buddhist doctrine and for discerning the intention behind its words of practical counsel. Interlaced with the verses specific to these four main levels, there runs throughout the work a large number of verses not tied to any single level but applicable to all alike. Taken together, these delineate for us the basic world view of early Buddhism. The most arresting feature of this view is its stress on process rather than persistence as the defining mark of actuality. The universe is in flux, a boundless river of incessant becoming sweeping everything along; dust motes and mountains, gods and men and animals, world system after world system without number — all are engulfed by the irrepressible current. There is no creator of this process, no providential deity behind the scenes steering all things to some great and glorious end. The cosmos is beginningless, and in its movement from phase to phase it is governed only by the impersonal, implacable law of arising, change, and passing away.

However, the focus of the Dhammapada is not on the outer cosmos, but on the human world, upon man with his yearning and his suffering, his immense complexity, his striving and movement towards transcendence. The starting point is the human condition as given, and fundamental to the picture that emerges is the inescapable duality of human life, the dichotomies which taunt and challenge man at every turn. Seeking happiness, afraid of pain, loss and death, man walks the delicate balance between good and evil, purity and defilement, progress and decline. His actions are strung out between these moral antipodes, and because he cannot evade the necessity to choose, he must bear the full responsibility for his decisions. Man's moral freedom is a reason for both dread and jubilation, for by means of his choices he determines his own individual destiny, not only through one life, but through the numerous lives to be turned up by the rolling wheel of samsara. If he chooses wrongly he can sink to the lowest depths of degradation, if he chooses rightly he can make himself worthy even of the homage of the gods. The paths to all destinations branch out from the present, from the ineluctable immediate occasion of conscious choice and action.

The recognition of duality extends beyond the limits of conditioned existence to include the antithetical poles of the conditioned and the unconditioned, samsara and Nibbana, the "near shore" and the "far shore." The Buddha appears in the world as the Great Liberator who shows man the way to break free from the one and arrive at the other, where alone true safety is to be found. But all he can do is indicate the path; the work of treading it lies in the hands of the disciple. The Dhammapada again and again sounds this challenge to human freedom: man is the maker and master of himself, the protector or destroyer of himself, the savior of himself (160, 165, 380). In the end he must choose between the way that leads back into the world, to the round of becoming, and the way that leads out of the world, to Nibbana. And though this last course is extremely difficult and demanding, the voice of the Buddha speaks words of assurance confirming that it can be done, that it lies within man's power to overcome all barriers and to triumph even over death itself.

The pivotal role in achieving progress in all spheres, the Dhammapada declares, is played by the mind. In contrast to the Bible, which opens with an account of God's creation of the world, the Dhammapada begins with an unequivocal assertion that mind is the forerunner of all that we are, the maker of our character, the creator of our destiny. The entire discipline of the Buddha, from basic morality to the highest levels of meditation, hinges upon training the mind. A wrongly directed mind brings greater harm than any enemy, a rightly directed mind brings greater good than any other relative or friend (42, 43). The mind is unruly, fickle, difficult to subdue, but by effort, mindfulness and unflagging self-discipline, one can master its vagrant tendencies, escape the torrents of the passions and find "an island which no flood can overwhelm" (25). The one who conquers himself, the victor over his own mind, achieves a conquest which can never be undone, a victory greater than that of the mightiest warriors (103-105).

What is needed most urgently to train and subdue the mind is a quality called heedfulness (appamada). Heedfulness combines critical self awareness and unremitting energy in a process of keeping the mind under constant observation to detect and expel the defiling impulses whenever they seek an opportunity to surface. In a world where man has no savior but himself, and where the means to his deliverance lies in mental purification, heedfulness becomes the crucial factor for ensuring that the aspirant keeps to the straight path of training without deviating due to the seductive allurements of sense pleasures or the stagnating influences of laziness and complacency. Heedfulness, the Buddha declares, is the path to the Deathless; heedlessness, the path to death. The wise who understand this distinction abide in heedfulness and experience Nibbana, "the incomparable freedom from bondage" (21-23).

As a great religious classic and the chief spiritual testament of early Buddhism, the Dhammapada cannot be gauged in its true value by a single reading, even if that reading is done carefully and reverentially. It yields its riches only through repeated study, sustained reflection, and most importantly, through the application of its principles to daily life. Thence it might be suggested to the reader in search of spiritual guidance that the Dhammapada be used as a manual for contemplation. After his initial reading, he would do well to read several verses or even a whole chapter every day, slowly and carefully, relishing the words. He should reflect on the meaning of each verse deeply and thoroughly, investigate its relevance to his life, and apply it as a guide to conduct. If this is done repeatedly, with patience and perseverance, it is certain that the Dhammapada will confer upon his life a new meaning and sense of purpose. Infusing him with hope and inspiration, gradually it will lead him to discover a freedom and happiness far greater than anything the world can offer.

— Bhikkhu Bodhi

Source:

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/kn/dhp/dhp.intro.budd.html#intro

Notes

1.(v. 7) Mara: the Tempter in Buddhism, represented in the scriptures as an evil-minded deity who tries to lead people from the path to liberation. The commentaries explain Mara as the lord of evil forces, as mental defilements and as death.

2.(v. 8) The impurities (asubha): subjects of meditation which focus on the inherent repulsiveness of the body, recommended especially as powerful antidotes to lust.

3.(v. 21) The Deathless (amata): Nibbana, so called because those who attain it are free from the cycle of repeated birth and death.

4.(v. 22) The Noble Ones (ariya): those who have reached any of the four stages of supramundane attainment leading irreversibly to Nibbana.

5.(v. 30) Indra: the ruler of the gods in ancient Indian mythology.

6.(v. 39) The arahant is said to be beyond both merit and demerit because, as he has abandoned all defilements, he can no longer perform evil actions; and as he has no more attachment, his virtuous actions no longer bear kammic fruit.

7.(v. 45) The Striver-on-the-Path (sekha): one who has achieved any of the first three stages of supramundane attainment: a stream-enterer, once-returner, or non-returner.

8.(v. 49) The "sage in the village" is the Buddhist monk who receives his food by going silently from door to door with his alms bowls, accepting whatever is offered.

9.(v. 54) Tagara: a fragrant powder obtained from a particular kind of shrub.

10.(v. 89) This verse describes the arahant, dealt with more fully in the following chapter. The "cankers" (asava) are the four basic defilements of sensual desire, desire for continued existence, false views and ignorance.

11.(v. 97) In the Pali this verse presents a series of puns, and if the "underside" of each pun were to be translated, the verse would read thus: "The man who is faithless, ungrateful, a burglar, who destroys opportunities and eats vomit — he truly is the most excellent of men."

12.(v. 104) Brahma: a high divinity in ancient Indian religion.

13.(vv. 153-154) According to the commentary, these verses are the Buddha's "Song of Victory," his first utterance after his Enlightenment. The house is individualized existence in samsara, the house-builder craving, the rafters the passions and the ridge-pole ignorance.

14.(v. 164) Certain reeds of the bamboo family perish immediately after producing fruits.

15.(v. 178) Stream-entry (sotapatti): the first stage of supramundane attainment.

16.(vv. 190-191) The Order: both the monastic Order (bhikkhu sangha) and the Order of Noble Ones (ariya sangha) who have reached the four supramundane stages.

17.(v. 202) Aggregates (of existence) (khandha): the five groups of factors into which the Buddha analyzes the living being — material form, feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness.

18.(v. 218) One Bound Upstream: a non-returner (anagami).

19.(vv. 254-255) Recluse (samana): here used in the special sense of those who have reached the four supramundane stages.

20.(v. 283) The meaning of this injunction is: "Cut down the forest of lust, but do not mortify the body."

21.(v. 339) The thirty-six currents of craving: the three cravings — for sensual pleasure, for continued existence, and for annihilation — in relation to each of the twelve bases — the six sense organs, including mind, and their corresponding objects.

22.(v. 344) This verse, in the original, puns with the Pali word vana meaning both "desire" and "forest."

23.(v. 353) This was the Buddha's reply to a wandering ascetic who asked him about his teacher. The Buddha's answer shows that Supreme Enlightenment was his own unique attainment, which he had not learned from anyone else.

24.(v. 370) The five to be cut off are the five "lower fetters": self-illusion, doubt, belief in rites and rituals, lust and ill-will. The five to be abandoned are the five "higher fetters": craving for the divine realms with form, craving for the formless realms, conceit, restlessness, and ignorance. Stream-enterers and once-returners cut off the first three fetters, non-returners the next two and Arahants the last five. The five to be cultivated are the five spiritual faculties: faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. The five bonds are: greed, hatred, delusion, false views, and conceit.

25.(v. 374) See note 17 (to v. 202).

26.(v. 383) "Holy man" is used as a makeshift rendering for brahmana, intended to reproduce the ambiguity of the Indian word. Originally men of spiritual stature, by the time of the Buddha the brahmans had turned into a privileged priesthood which defined itself by means of birth and lineage rather than by genuine inner sanctity. The Buddha attempted to restore to the word brahmana its original connotation by identifying the true "holy man" as the arahant, who merits the title through his own inward purity and holiness regardless of family lineage. The contrast between the two meanings is highlighted in verses 393 and 396. Those who led a contemplative life dedicated to gaining Arahantship could also be called brahmans, as in verses 383, 389, and 390.

27.(v. 385) This shore: the six sense organs; the other shore: their corresponding objects; both: I-ness and my-ness.

28.(v. 394) In the time of the Buddha, such ascetic practices as wearing matted hair and garments of hides were considered marks of holiness.

You may copy, reformat, reprint, republish, and redistribute this work in any medium whatsoever, provided that: (1) you only make such copies, etc. available free of charge and, in the case of reprinting, only in quantities of no more than 50 copies; (2) you clearly indicate that any derivatives of this work (including translations) are derived from this source document; and (3) you include the full text of this license in any copies or derivatives of this work. Otherwise, all rights reserved. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. From The Dhammapada: The Buddha’s Path of Wisdom, translated from the Pali by Acharya Buddharakkhita, with an Introduction by Bhikkhu Bodhi (Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1985). Transcribed from the print edition in 1996 by a volunteer under the auspices of the DharmaNet Transcription Project, with the kind permission of the BPS. Last revised for Access to Insight on 30 November 2013.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nikos Deja Vu - Ο Μέγας Βασίλειος (Basilius Magnus - Saint Basil of Caesarea - Vasileios The Great (The Greek Santa Claus)

Basil of Caesarea (Πατήστε ΕΔΩ για Ελληνικά) Βασίλειος ο Μέγας Αγιος Βασίλειος Vasileios The Great - Saint Basil (The Greek Santa Claus)