#because they seem them as singularly responsible for creating Thing They Liked because of the aforementioned spokesmanship

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

low-coherency rambling in the tags

#the thing about IPL is that‚ at least as far as i see it‚ they've essentially been propagating and encouraging an auteur myth regarding him#which is nothing new or unique to them; i think that people (audiences) naturally want to ascribe some Great Man Theory to everything#it's hard to conceptualize the fact that almost anything that comes from a ''studio'' will be the product of collaboration#people naturally want to personify things and attach a human face to what they like#and studios (whether game or whatever else) will indulge this by generally seeming to pick one or maybe two people (often men)#to essentially be the main ''face'' or ''spokesperson'' for the product. it's branding.#and it has an effect even if people obviously are aware that someone isnt the ONLY person who's hands touch a work#i see it in the way people take this very personal parasocial tone in how they talk about the creators they like#which is just a subset of the problem of parasociality in general but in this case i mean how they basically put these people on a pedestal#because they seem them as singularly responsible for creating Thing They Liked because of the aforementioned spokesmanship#i've seen it in how people talk about (and talk to) j sawyer and chris avellone as if they're singularly responsible for fallout#anthony burch and borderlands 2. christian linke and arcane#robert kurvitz and disco elysium (but to be very clear im not saying that makes cutting him out of his own intellectual property acceptable#fucking i don't know.... jeff kaplan and overwatch lmao#and very much with dybowski and pathologic. like the kind of memes i saw people make about him and the personal way they'd refer to him#BUT that pretty much all stopped after 2021 or so at least in the fandom spaces i saw#because i suppose people realized that whether those rumors and allegations were true or not that they did not really know this person#no matter how much they liked ''his'' game. and that he might not be a good person at all.#which is good. i think people should take that kind of ambivalence by default instead of getting parasocially attached to anyone#especially to one lead figure out of an entire studio#and then winding up distraught and disappointed when it turns out their fave did something bad#like be distraught for victims sure. but don't tell yourself you understand this person because their fiction spoke to you#and you won't wind up feeling personally betrayed.#i'm rambling big time but basically i hope people start taking this view more#because among other things. putting these people on pedestals and singling them out as auteurs gives them social power#which allows some of them to engage in the awful behavior that leaves fans feeling betrayed in the first place#and i hope that studios and creators stop leaning into it too#if it really is true that dybowski is barely involved with the IP anymore then IPL should say that.#don't prop him up as the face just because he's the one everyone knows#maybe they think it'll get backlash if anyone but him is said to be writing the game because of how much they leaned into him as the auteur

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

(thoughts under cut)

I think the message is pretty muddled and weak tbh, and it basically has two arguments. It tries to make a meta-point about how something as awful as a killing game can only exist through the consent of its audience, and tries to turn the mirror around on the players like "look what you have done," which falls flat since it's a video game, not real life. There is no moral culpability in the deaths of fictional characters, and it also ignores the capitalistic argument that in both cases, in our real world where Danganronpa is a video game series, and in the world inside v3 where it's a reality show, the property only exists because the creators are driven by profit motives over anything else. There are hundreds if not thousands of media properties that people would pay for a new installment of, but that aren't made because the creators don't feel strongly about them, or want to make something else. It feels weird to introduce a narrative element of "you the audience (real and fictional) are the real villains for enjoying such sick media," while absolving oneself as the creator from any responsibility for creating it.

It's a bad argument and it makes v3's ending fall apart, because it's so based on meta-narratives. It feels like v3 wants to engage with the player personally, for the ending to be an Undertale moment or a Stanley Parable moment or whatever, but it just doesn't really hit beyond an IAm14AndThisIsDeep way. It fails to go hard enough on that goal to really pierce the fourth wall and make a serious impact on the player, but the fact that it's there at all sort of robs the moment of character-based impact, so to me, the ending fails to deliver a satisfying conclusion for the characters, and also fails to really give the player something to chew on with regards to their own engagement with the game.

Where it succeeds, I think, (both intentionally and unintentionally) is showing how Danganronpa has run its course and has no more reason to exist. There are franchises like Pokemon that can be iterated upon forever with new regions and new characters, and there are franchises like Persona that are an anthology - there are recurring characters and themes, but each is a standalone entity that can exist by itself. Danganronpa, between the first two games, the spinoff, the mobile games, all the anime seasons, the OVAs, etc. has been singularly focused on a story about Junko Enoshima, Monokuma, Hope's Peak Academy, The Tragedy, etc, and by the end of SDR2 and DR3 the anime, that story is concluded. Danganronpa isn't just a game about killing games, it's a game about a specific event drawn up by a specific girl and her fursona and all the supplemental media tie into that story.

V3 shows that "where do we go from that" is a question without an answer, because a killing game without HPA, without Ultimates, without Monokuma, without the specter of Junko Enoshima, isn't Danganronpa, it's something else. But, including those things, shoehorning Monokuma in, making characters Ultimates without the connection to HPA, adding Junko content, without any real connection to the story of the other games feels wrong. It feels like cheap fanservice. V3 adheres so rigidly to the Danganronpa "formula," as well, that it draws attention to it, and makes it almost seem like a parody, even where the structural similarities between THH and SDR2 felt like affectionate callbacks or funny coincidences. A softer male protagonist and a less emotional female sidekick. A frustrating male antagonist who nevertheless has good intentions. An early chapter where the kill was accidental, or the victim wasn't the intended victim. A middle chapter with two victims. A late-middle chapter that involves a serious puzzle about the nature of the situation itself. An ending with a big twist and also Junko is there.

Whether intentional or not, it asks "is this what you want? do you want a formula? do you want us to bend over backwards so that the silly blonde girl and her bear show up, do you want the Sad Kill chapter and the Double Kill chapter and the Mindbending Puzzle Kill chapter, do you want us to constantly be in conversation with the structure of a PSP game from 2010? Do you want a copy of a copy of a copy forever?" and I think the answer to that question should be no. I don't want to see Junko in Fortnite or Smash, I don't want Danganronpa 7: We're Out Of Ideas But People Keep Buying Them For Some Reason, I don't want a franchise that I enjoy (despite everything and I do mean EVERYTHING) to become paint-by-numbers and just churned out forever.

I think v3 is the weakest story. It's clear from the writing and the ending that they were struggling with what it was "about," and were brushing up against that same problem of if Danganronpa can be an anthology series or whether it needs to relate to its original story to be Danganronpa. That feels uncontroversial to me, but I still enjoy it and believe it's a great game. I love the characters, and I think the actual gameplay is the best in the series, with good minigames and bonus modes and a much nicer presentation. The ending is just the point at which I realized there probably wasn't going to be another full mainline Danganronpa game for a long time, if ever, and decided that was probably the right call.

As for what is and is not true from the ending, I'm sure if you played the entire game, keeping track of everything, you could find some definitive statements to make about what is and is not true, but I don't think that's the point. Even if it's badly executed, I think the theming of the game means you're supposed to accept what is told to the characters by Tsumugi as at least mostly true. More than that, though, I think it doesn't matter because the game sacrifices the characters in favor of trying to grab the player's attention and interface with the player directly. I have thoughts about how to incorporate v3's ending into RP and storytelling in an interesting (I hope?) way, but that's beside the point and this post is long enough already.

so also. v3 fans! i'm super curious to hear your thoughts on what the main message of the game is, if anything at all?? and thoughts on the ending, what is and isn't a lie in your opinion, etc too would be awesome.

i've been spoiled on everything and watched a fair bit of the ending already, so feel free to go crazy with spoilers! i've been wanting to get into the game and hearing people's takes on it helps generate hype for me + i'm genuinely really curious as well, lol. thank youuuuu ;w;

#sorry for the reblog but I have so many thoughts about this good/trash game#they did not fit in the comment section even splitting them into like three or four#i am the v3 defender but also the v3 criticizer

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

The article goes on to point out a number of bible verses that seem to contradict that notion as well as a couple of the aforementioned arguments but one I'm surprised to never see anyone bring up is: if god already knows whether or not were gonna follow his "rules" and either way were still following his "plan" then why impose rules in the first place?

[cont'd] I still don't find Abrahamic religions to be particularly believable for a number of reasons but I'd say this at least gives them a lot more internal consistency

[That is, regarding the Abrahamic god not having the "omni" attributes.]

The Abrahamic god was created to supplant polytheistic religions and their various gods, all of whom had unique interests or quirks or tendencies. The competing interests of those various gods could explain the unpredictability of the world. You pray to the goddess of the harvest for rain for your crops, but she's at war with the god of the sun, so whether your crops will grow or shrivel in a drought depends on the fates of the gods, none of whom was omni in nature, or singularly held power.

Monotheism consolidated these gods down into a single god, so that there is a single word of god, single doctrine, rather than the mishmash of devotees of the sun god, the war god, the harvest god, etc, etc, all with their own practices. Abrahamism attempts to control everyone consistently, and therefore makes one god responsible for all of it, made "omni" by granting it all the powers and qualities of all the gods combined.

The problem is that the world is not consistent, and the cracks in this mythology show much more readily. Especially around its omni-ness. The polytheistic pantheons had an excuse: all the various gods had domain over only whatever they had domain over. They were one of many. The contentions and relationships and drama between the gods may give you some rain but not enough for your crops to survive.

But a monotheistic god has domain over everything. It is solely responsible. If you don't get enough rain, it's because your omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, omnibenevolent, omnitemporal god somehow doesn't want you to, doesn't know yo need it, or can't give it to you.

Not being omni does make the story more internally consistent. But it also makes randomness more powerful than the deity, and undercuts the entire point of theism in the first place. Because if a god isn't in control of everything, then god doesn't have control of everything. And trying to explain randomness, due to people's discomfort with it, is one the key driving factors for religiosity in the first place. That there is some kind of order to the universe, that something is in control and will prevent it all from spiralling into utter chaos, as well as being able to seek some form of control themselves, that they can petition for help from, or the favor of, god. That there's a reason for the lightning, the drought, the floods, the infant mortality, not just the indifferent arbitrariness of nature. If god doesn't have those omni qualities, then nobody is fully in control, and help from above is bounded by limitations. This god is subject to the restrictions and boundaries of the universe, like anyone.

So, while it’s more consistent narratively, it’s more unpalatable to the believer and what they need from their imaginary friends.

--

The bible is explicit about predestination. It says it again and again that "Lord" doesn't just already know, but decided and made things, chose people to believe and those not to believe, right from the very beginning, before anything even existed.

Romans 8:29-30

For whom he did foreknow, he also did predestinate to be conformed to the image of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brethren. Moreover whom he did predestinate, them he also called: and whom he called, them he also justified: and whom he justified, them he also glorified.

Romans 9:11-22

(For the children being not yet born, neither having done any good or evil, that the purpose of God according to election might stand, not of works, but of him that calleth;) It was said unto her, The elder shall serve the younger. As it is written, Jacob have I loved, but Esau have I hated. What shall we say then? Is there unrighteousness with God? God forbid. For he saith to Moses, I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I will have compassion. So then it is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth, but of God that sheweth mercy. For the scripture saith unto Pharaoh, Even for this same purpose have I raised thee up, that I might shew my power in thee, and that my name might be declared throughout all the earth. Therefore hath he mercy on whom he will have mercy, and whom he will he hardeneth. Thou wilt say then unto me, Why doth he yet find fault? For who hath resisted his will? Nay but, O man, who art thou that repliest against God? Shall the thing formed say to him that formed it, Why hast thou made me thus? Hath not the potter power over the clay, of the same lump to make one vessel unto honour, and another unto dishonour? What if God, willing to shew his wrath, and to make his power known, endured with much longsuffering the vessels of wrath fitted to destruction:

Ephesians 1:4-5

According as he hath chosen us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and without blame before him in love: Having predestinated us unto the adoption of children by Jesus Christ to himself, according to the good pleasure of his will,

2 Timothy 1:9

Who hath saved us, and called us with an holy calling, not according to our works, but according to his own purpose and grace, which was given us in Christ Jesus before the world began,

"Lord" made unbelievers, deliberately makes people to not believe the purported "truth" of Xianity, even "tricks" them into non-belief.

2 Thessalonians 2:11-12

And for this cause God shall send them strong delusion, that they should believe a lie: That they all might be damned who believed not the truth, but had pleasure in unrighteousness.

Mark 4:11-12

And he said unto them, Unto you it is given to know the mystery of the kingdom of God: but unto them that are without, all these things are done in parables: That seeing they may see, and not perceive; and hearing they may hear, and not understand; lest at any time they should be converted, and their sins should be forgiven them.

Matthew 7:13-14

Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat: Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

So it's not even just that this god already knows, and therefore it's all completely unnecessary, the bible is unrelentingly insistent that it's outright what it wants, what it intends, what this creator god, this "potter" who has "power over the clay," created by design.

#ask#christianity#bible#bible study#predestination#free will#creator god#religion#religion is a mental illness

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fugitives from the Fire: Chapter 5, Part 2

“Hey, madam innkeeper: where would you normally have been in the building?”

“……Since when did you get in charge of the investigation?”

As Sherlock took the lead, it seemed Gregson was displeased, but also no longer in the mood to put up a fight.

Hillary sniffed.

“I was always at the reception desk. I’m the only one managing the inn; I don’t have a single employee.”

“In that case, do you remember when these three men came to book their rooms? Or rather, at the time, had there been anyone with burns on their face?”

Sherlock was now diverting the conversation away from the case, instead attempting to verify if there were eyewitness accounts of the other fugitive. However, Gregson responded in a low voice.

“Holmes: it’s not going to work. We also tried asking her when we arrived at the scene back then, but it seems she has a strange policy of protecting her guests’ privacy, so she doesn’t check her guests’ appearances and such too closely.”

It seemed Hillary had heard him whispering, for she spoke up in defiance.

“You know, these parts are full of people with something to hide. I always make sure they pay up, but I don’t do such tactless things as staring people in the face.”

“Tactful, eh……”

Even Sherlock couldn’t stop himself; he cracked a wry grin. He didn’t know if it was an unwritten rule of the slums, but the innkeeper’s response was certainly a little too risky.

Nevertheless, at this point, there was nothing to be gained from laying blame on her. Sherlock continued.

“In that case, when the fire started, were you also at the reception?”

“That’s right. I wanted to stay there until the fire was contained, but a bunch of bobbies dragged me out at the very last moment.”

It seemed the lady possessed a truly dauntless spirit, so much so she had been willing to go down with her inn. That elicited something close to admiration within Sherlock, and he looked over the suspects.

“You mentioned ‘the very last moment’… That means you stayed at the reception until everyone had escaped?”

“Indeed: as the landlady, I have to ensure my guests are safe. Besides these guys, I definitely saw the ones from rooms 102 and 201 escape out the front door.”

“You’re indeed the epitome of a host.”

In his mind, Sherlock added this new piece of information on the guests’ rooms.

Excluding the murder victim, there had been five guests in total.

On the ground floor, rooms 101 (Jerry Dorff) and 102 had been occupied.

On the first floor, rooms 201 and 203 (Mike Myers).

Then on the second floor, room 301 (Bruno Campbell).

As he gathered the respective locations of the guests, the proprietress spoke up.

“Oh yes — earlier, everyone was talking about who had the chance to go up to the second floor, right? You’ll have to rule out Mr Jerry over there: for some reason, he immediately ran outside when the fire began. He seemed the very picture of alarm.”

“Hmm; this man, panicked?”

As far as he was concerned, people were free to run away in any manner they liked. But the gap between that and the taciturn, mysterious man before them made even Sherlock’s expression soften. It seemed Jerry had been strangely embarrassed by that reaction, deliberately clearing his throat.

Then, the detective turned to Gregson.

“Come to think of it, when you were going back upstairs, did you go past anyone? There must’ve been people rushing to escape.”

“I remember that: I passed by Bruno, Mike, and one other guest on the stairs. But is that important somehow?”

“If the killer had been among them, then he must’ve murdered the victim in the short period between the time you went downstairs to check the situation, and the time you returned to the second floor.”

Gregson groaned. “……Of course, that interval feels way too short. It didn’t even take me 30 seconds to go downstairs and back up again. So, that means……”

The locations of the suspects’ rooms. The escape route. The span of time until the victim had been murdered. Putting together all the clues they’d gathered by questioning the people involved, a single answer surfaced of its own accord.

“——It’s impossible for the killer to have gone upstairs and murdered him.”

Sherlock sounded as if he were pronouncing a judgement. Then, Gregson finally got his head around it — just like what a detective’s assistant would’ve done.

——“In that case, how did he murder the man in the room?”

“T-Then, the man in the room — how was he murdered……?”

Once again, the John in his imagination overlapped with Gregson. In theory, this ‘riddle’ had turned into something impossible to solve, and the assistant inspector was wracked with an anguish akin to agony.

However, that was a tale that only applied to ordinary people.

With his singularly transcendent powers of deduction, the consulting detective had already narrowed down two answers to this case.

Truthfully, right now, he could proceed to the solution right away. But for some reason, he didn’t want to do that. Surely, the reason why he was investigating the truth like this, was because he saw the figure of the man before him strenuously racking his brains.

As Gregson continued to despair, Sherlock Holmes placed a hand on his back.

“Gregson, do you have a moment?”

“……What do you want?”

He looked exhausted — but that was a weariness born from his own sense of responsibility, and even Sherlock refused to take a jibe at him now.

Gregson was shouldering a duty as a police inspector, so the detective resolved to use a little discretion.

“I want to talk to you outside for a bit.”

“…………”

Sherlock had said so in a serious tone, and Gregson didn’t put up a fight.

✦ ✦ ✦ ✦

Once they left the inn, an unnerving oppressiveness made their skin prickle: clearly, the locals’ anger had only intensified. Lestrade was trying his best to negotiate with and conciliate them, but it wouldn’t be long before their frustration boiled over.

Yet, even as they were caught in this race against time, Sherlock remained unhurried. On the streets to which filth clung here and there, he began to speak as if they were simply having a chat.

“First off, from the conversation earlier, we’ve eliminated the possibility that the culprit went to room 303 and killed him. As such, we have to consider a different tack.”

“A different tack?”

“What I mean is, the idea that he didn’t attack from the door — rather, the window.”

Sherlock proposed the theory he’d thought up at the start: that the man had been shot from the window. With this idea, they could break free of the ‘riddle’ created by the locked room — the murderer could kill the victim even without going all the way to the second floor.

However, Gregson shrugged in amazement, and explained in an indifferent tone.

“This might dispute the deduction you’re so proud of, but we did look into that as well. Firstly, for this method to work, there must’ve been two men in total: one to start the fire at the inn, and the other to shoot the victim from outside. But hiring another collaborator to silence an accomplice, or settle a falling-out, brings its own share of danger. In addition, in order to shoot his victim, a gunman would minimally have to be at the same height as him. There’s a brothel across the street from the inn, facing its north wall, and with three floors to boot, it fits the bill. But at the time of the murder, there’d been people on its second floor, and no one testified that they heard a gunshot. Hence, that explanation has to be rejected.”

Unusually, the inspector had discussed his view without a hint of his usual thorny attitude.

But Sherlock was adamant. “If that’s the case, then——”

——“If that’s the case, then how about something like this? Sherlock.”

His partner’s voice resounded through his mind. Now, the detective persisted in playing the role of an assistant, raising another idea to the inspector.

“From the street beside the inn, he could’ve aimed at room 303’s window and shot the victim. With that, he wouldn’t have raised suspicions among the people in the brothel.”

“……That’s rather cliché. There were officers outside the inn, so if there’d been someone with a gun outside, they would’ve arrested him long ago. Moreover, the victim collapsed a step away from the room door. If he’d been shot from the window, he would’ve lain there still. Even if he had then used the last of his strength to crawl all the way to the door, with that level of blood loss, it’d be strange that there hadn’t been a trail of blood leading from the window. As I said earlier, as far as I could tell through the keyhole, I didn’t see any marks like that.”

The inspector calmly refuted his theory, and Sherlock made the same troubled face as John always did.

——Then and there, he eliminated one of his two suppositions, and completely saw through the ‘riddle’ of this case.

“Is that so? Then I’m completely at a loss here.”

“Hmm, what’s gotten into you since earlier? ……You kept making deductions that were quite unlike you.”

Gregson had casually said something that, deep down, revealed a glimpse of his recognition of the detective’s ability. Unwittingly, Sherlock broke into a gentle smile.

But just as quickly, he replaced it with the troubled expression required of the fool he was playing. Sherlock put both hands behind his head, and looked up at the sky.

“Hey, Gregson. Somehow, we’ve been talking over and over and getting nowhere; so for a change of pace, how about a quiz?”

“Huh? You purposely brought me all the way outside, for a quiz?!”

Gregson frowned, but Sherlock continued without a care.

“Let’s say there are two children, A and B, and they’re friends. One day, the two of them play catch at a distance of about 20 steps away from one another. But although A can throw the ball to B, B can’t throw it back to A. Why is that so? In case you were wondering, the two of them have the same strength.”

“……Hmm.”

Gregson forgot about his complaints for a moment, and pondered.

“Did B sprain his shoulder?”

“In a quiz like this, that kind of reasoning’s rubbish, isn’t it?”

“There’s a wall between them.”

“Then A couldn’t have thrown the ball over.”

“……Another kid suddenly appeared and stole the ball.”

“You’re being a little careless, aren’t ya?”

It was unclear what the intention behind this quiz was, and to top it off, Sherlock had rejected every one of his answers. At last, Gregson raised his voice.

“Dammit, just tell me the answer already! Also, what’s the point of a quiz like this?!”

“Come on, now,” Sherlock parried. “I’ll give you a hint: for example, try looking at this building here.”

“Hmm……”

The detective pointed to the inn they had just stepped out of. Coincidentally, just like the one that had burnt down, this building also had three floors.

“What about it?”

“Man, you’re still as slow as ever. Look……”

Sherlock pointed to a window on the upper floors, and moved his finger between that and the window below it a few times.

Watching that action, Gregson seemed to have arrived at the answer himself.

“I see. So the children were standing on the upper and lower floors respectively, and leaning out the windows to throw the ball? Although it could be thrown from the floor above to the one below, it would be difficult to throw the ball back up in the other direction. That’s to say, the distance of 20 steps was not lengthwise, but vertical——”

Right then, as if a bolt of electricity had coursed through him, Gregson twitched. His hand shot to his chin; sinking deep into thought, he remained absolutely motionless, with only his lips piecing fragments together into clues.

“There’s only one way…… To be able to kill without going upstairs…… In that case, the position of the body…… And it ending up as a locked room…… But, such an extraordinary method –– is it even possible?”

At his final question, Sherlock grinned.

“I don’t have the foggiest idea what you just thought of…… But when you’ve eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” [1]

“………!”

Gregson looked at the detective, standing boldly where he was.

Whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

That was what he’d always maintained.

A suicide, or an accident. Pretending to be dead. Entering the room and murdering him. A sniper shot from the window. After carefully pursuing all lines of thought, in the end, only this solution remained.

In that case, it had to be the truth.

Could it be, that he’d started this entire conversation in order to guide him here……?

“……Hmph.”

At that thought, Assistant Inspector Gregson reassumed his usual, haughty attitude: the manner of a police inspector who saw the detective as his enemy.

“Let’s go, Holmes. I’ll tell you what I’ve deduced.”

——This is my case.

As Gregson strode away triumphantly, Sherlock chuckled.

T/N: Sherlock has grown so much..! (my /heart/)

Footnotes:

[1] A quote from Chapter 6 of the Sherlock Holmes novel The Sign of the Four, by Arthur Conan Doyle. (Wikipedia)

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nihilism is so easy, which is why we need to kill it

(I initially published this here a couple weeks ago.)

So last night it dawned on me that, after over two years of being relatively symptom-free, my depression snuck back up on me and has taken over. It’s still pretty mild in comparison to other times I’ve been stuck in the hole, but after 24 months (and more) of mostly being good to go, I can tell that it’s here for a hot minute again.

How do I know? Well, it might be the fact that I spent more time sleeping during my recent vacation from work than I did just about anything else, and how it’s suddenly really hard for me to stay awake during work hours. I don’t really have an appetite, and in fact nausea hits me frequently. I don’t really have any emotional reactions to things outside of tears, even when tears aren’t super appropriate to the situation (like watching someone play Outer Wilds for the first time). And I’ve been consuming a lot of apocalyptic media, to which the only response, emotional or otherwise, I can really muster is “dude same.”

For a long time I was huge into absurdist philosophy, because it felt to my depressed brain like just the right balance between straight up denying that things are bad (and thus we should fix them, or at least try to do so) and full-blown nihilism. This gives absurdism a lot of credit; mostly it’s just a loose set of spicy existentialist ideas and shit that sounds good on a sticker, like “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.”

In the last couple years, while outside of my depressive state, I went back to Camus’ work and found a lot of almost full-on abusive shit in it. Not toward anyone specifically, but shit like “nobody and nothing will care if you’re gone, so live out of spite of them all” rubs me the wrong way in retrospect. The philosophy Camus puts out opens the door for living in a very self-destructive fashion; that in fact the good life is living without care for yourself or anyone/anything else. The way Camus describes and derides suicide especially is grim as fuck, and certainly I would never recommend The Myth of Sisyphus to anyone currently struggling with ideation. That “perfect balance” between denial and nihilism is really not that perfect at all, and in fact skews much more heavily towards the latter.

Neon Genesis Evangelion has been a big albatross around my neck in terms of the media products I’ve consumed in my life that I believe have influenced my depression hardcore. It sits in a similar conversational space to Camus’ work, in that it confronts nihilism and at once rejects and facilitates it. A lot of folks remark that Evangelion is pretty unique – or at least uncommon – in its accurate portrayal of depression, especially for mid-90s anime properties. The thing I notice always seems to be missing in these discussions is that along with that accurate portrayal comes a spot-on – to me, at least – depiction of what depression does to resist being treated. This is a disease that uses a person’s rational faculties to suggest that nobody else could possibly understand their pain, and therefore there’s no use in getting better or moving forward. Shinji Ikari is as self-centered as Hideaki Anno is as I am when it comes to confronting the truth: there are paths out of this hole, but nobody else can take that step out but us, and part of our illness is that refusal to do just that. Depression lies, it provides a cold comfort to the sufferer, that there is no existence other than the one where we are in pain and there is no way out, so pull the blanket up over our head and go back to sleep.

Watching Evangelion for the first time corresponded with the onset of one of the worst depressive spirals I’ve ever been in, and so, much like the time I got a stomach virus at the same time that I ate Arby’s curly fries, I kind of can’t associate Evangelion with anything else. No matter what else it might signify, no matter what other meaning there is to derive from it, for me Eva is the Bad Feeling Anime™. Which is why, naturally, I had to binge all four of the Evangelion theatrical releases upon the release of Evangelion 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon A Time last month.

If Neon Genesis Evangelion and End of Evangelion are works produced by someone with untreated depression just fucking rawdogging existence, then the Eva movies are works produced by someone who has gone to therapy even just one fucking time. Whether that therapy is working or not is to be determined, but they have taken that step out of the hole and are able to believe that there is a possibility of living a depression-free life. The first 40 minutes or so of Evangelion 3.0+1.0 are perfect cinema to me. The world is destroyed but there is a way to bring it back. Restoration and existence is possible even when the surface of the planet might as well be the surface of the Moon. The only thing about this is, everyone has to be on board to help. Even though WILLE fired one of its special de-corefication devices into the ground to give the residents of Village 3 a chance at survival, the maintenance of this pocket ecosystem is actively their responsibility. There is no room or time for people who won’t actively contribute, won’t actively participate in making a better world from the ashes of the old.

There are a lot of essentialist claims and assumptions made by the film in this first act about how the body interacts with the social – the concept of disability itself just doesn’t seem to have made it into the ring of safety provided by Misato and the Wunder, which seems frankly wild to me, and women are almost singularly portrayed in traditionalist support roles while men are the doers and the fixers and the makers. I think it’s worth raising a skeptical eyebrow at this trad conservative “back to old ways” expression of the post-apocalypse wherever it comes up, just as it’s important to acknowledge where the movie pushes back on these themes, like when Toji (or possibly Kensuke) is telling Shinji that, despite all the hard work everyone is doing like farming and building, the village is far from self-sufficient and will likely always rely on provisions from the Wunder.

As idyllic as the setting is, it’s not the ideal. As Shinji emerges from his catatonia, Kensuke takes him around the village perimeter. It’s quiet, rural Japan as far as the eye can see, but everywhere there are contingencies; rationing means Kensuke can only catch one fish a week, all the entry points where flowing water comes into the radius of the de-corefication devices have to be checked for blockages because the water supply will run out. There is a looming possibility that the de-corefication machines could break or shut down at some point, and nobody knows what will happen when that happens. On the perimeter, lumbering, pilot-less and headless Eva units shuffle around; it is unknown whether they’re horrors endlessly biding their time or simply ghosts looking to reconnect to the ember of humanity on the other side of the wall. Survival is always an open question, and mutual aid is the expectation. Still: the apocalypse happened, and we’re still here. The question Village 3 answers is “what now?” We move on, we adapt.

Evangelion is still a work that does its level best to defy easy interpretation, but the modern version of the franchise has largely abandoned the nihilism that was at its core in the 90s version. It’s not just that Shinji no longer denies the world until the last possible second – it’s that he frequently actively reaches out and is frustrated by other people’s denials. He wants to connect, he wants to be social, but he’s also burdened with the idea that he’s only good to others if he’s useful, and he’s only useful if he pilots the Eva unit. This last movie separates him and what he is worth to others (and himself) from his agency in being an Eva pilot, finally. In doing so, he’s able to reconcile with nearly everyone in his life who he has harmed or who has hurt him, and create a world in which there is no Evangelion. While this ending is much more wishful thinking than one more grounded in the reality of the franchise – one that, say, focuses on the existence and possible flourishing of Village 3 and other settlements like it while keeping one eye on the precarious balancing act they’re all playing – it feels better than the ending of End of Eva, and even than the last two episodes of the original series.

I’m glad the nihilism in Evangelion is gone, for the most part. I’m glad that I didn’t spend roughly eight hours watching the Evamovies only to be met yet again with a message of “everything is pointless, fuck off and die.” Because I’ve been absorbing that sentiment a lot lately, from a lot of different sources, and it really just fuckin sucks to hear over and over again.

It is a truth we can’t easily ignore that the confluence of pandemic, climate change, authoritarian surge and capitalist decay has made shit miserable recently. But the spike in lamentations over the intractability of this mix of shit – the inevitability of our destruction, to put it in simpler terms – really is pissing me off. No one person is going to fix the world, that much is absolutely true, but if everyone just goes limp and decides to “123 not it” the apocalypse then everyone crying about how the world is fucked on Twitter will simply be adding to the opening bars of a self-fulfilling prophesy.

We can’t get in a mech to save the world but then, neither realistically could Shinji Ikari. What we can do looks a lot more like what’s being done in Village 3: people helping each other with limited resources wherever they can.

Last week, Hurricane Ida slammed into the Gulf Coast and churned there for hours – decimating Bayou communities in Louisiana and disrupting the supply chain extensively – before powering down and moving inland. Last night the powerful remnants of that storm tore through the Northeast, causing intense flooding. Areas not typically affected by hurricanes suddenly found themselves in a similar boat – pun not intended – to folks for whom hurricanes are simply a fact of life. There’s a once-in-a-millennium drought and heatwave ripping through the West Coast and hey – who can forget back in February when Oklahoma and Texas experienced -20 degree temperatures for several days in a row? All of this against the backdrop of a deadly and terrifying pandemic and worsening political climate. It’s genuinely scary! But there are things we can do.

First, if you’re in a weather disaster-prone area, get to know your local mutual aid organizations. Some of these groups might be official non-profits; one such group in the Louisiana area, for example, is Common Ground Relief. Check their social media accounts for updates on what to do and who needs help. If you’re not sure if there’s one in your area, check out groups like Mutual Aid Disaster Relief for that same information. Even if you’re not in a place that expects to see the immediate effects of climate change, you should still consider linking up with organizing groups in your area. Tenant unions, homeless organizations, safe injection sites and needle exchanges, immigrant rights groups, environmental activist orgs, reproductive health groups – all could use some help right now, in whatever capacity you might be able to provide it.

In none of these scenarios are we going to be the heroes of the story, and we shouldn’t view this kind of work in that way. But neither should we give into the nihilistic impulse to insist upon doing nothing, insist that inaction is the best course of action, and get back under the blankets for our final sleep. Kill that impulse in your head, and fuck, if you have to, simply just fucking wish for that better world. Then get out of bed and help make it happen.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

the gamble of the heart | chapter 1 (r.l.)

chapter one: certain uncertainty

series masterlist

pairing: remus lupin x potter!reader

chapter summary: remus reflects on when he lost the person he held closest to his heart.

warnings: swearing

wordcount: 2.2k

a/n: hi! this is a new remus series i’m working on. WARNING it’s going to be slowburn. hope you enjoy <33

REMUS LUPIN was never one to rely on the idea of certainty. In his sixteen years of life, Remus had gathered that the way the world worked didn’t allow for anything to be certain. For example, he could have been certain that the only peculiar thing about him would have been that he was a wizard (and really this was only peculiar to unknowing muggles). However, at the age of four, his life went off track and he was suddenly a werewolf and had no understanding of what that meant. It wasn’t always bad, however. Sometimes life was uncertain in a good way. At one time Remus was certain that a life of isolation was a fate he would have to accept, but within his first day at Hogwarts, he was proven wrong.

And so, Remus decided that it was okay that virtually nothing was certain. He had even begun enjoying the uncertainty of life at times. He enjoyed not knowing what crazy adventure his mates and him would journey through next and he even liked the uncertainty of what subjects he would have to tackle next in his favorite classes. Which is why he couldn’t understand why he was surprised by the events unfolding now. His relationship with Y/N hadn’t even been official, yet he was stuck pondering over her recent actions instead of the notes laid out in front of him. He knew he hadn’t imagined the feelings that had been growing between the two of them and he had the image of intimate touches ingrained in his mind as proof of that. So, why? Why had she stopped looking at Remus like he held the stars in his hands? Why had she trained her sight on that lousy Ravenclaw instead? Why was she holding his hands in the halls, when the two of them had never even been so publicly affectionate? But most importantly, why was he so surprised by the uncertainty of it all?

A part of Remus - the part that resonated with his younger self most - knew he shouldn’t have been surprised. He knew it was unlikely that any girl, especially a girl as captivating as Y/N, would have been interested in him for long. Not only was he singularly boring in his opinion, but he was a monster. The other part of Remus - the part he had spent years working on - couldn’t understand why she was suddenly acting like she forgot he existed. He knew they worked well together. He knew that he understood her in a way no one else had. He knew that he was perfect for her. Or at least he’d say he was.

“What did that poor piece of parchment ever do to you, Moony?” A voice behind him pulled him out of his thoughts and Remus’ eyes flickered down to the notes in front of him. He had been holding his inked up quill to the paper for so long it had created a hole that was getting bigger from the severity of his hold. Dropping the quill, Remus looked up to see Peter stood in the doorway.

“Uh, must’ve zoned out,” Remus muttered, sending Peter a lackadaisical smile. “What are you lot up to?”

“Headed to Hogsmeade. You sure you don’t wanna join, mate? I’m sure you’re not gonna do much good just tearing through your notes. Literally.” Remus ignored Peter’s poor attempt at a pun and considered his options. He really wasn’t doing much good sitting at his desk and he needed to get his mind off certain things. No better way to do that than with the three most troublesome boys.

“Alright, yah,” Remus nodded his head at Peter who was frowning. “You’re right, Pete. No point in tearing through my notes.” Content with Remus’ validation, Peter led the two out of their dorm and down to the common room.

“YES! Prongs, we’ve got Moony on board!”

—

Being at Hogsmeade during the start of the year always felt odd. Remus would argue that it was one of those things that only made sense during the holidays. He had gotten into many heated debates with James about whether Hogsmeade could be considered fun this early in the school year. James would start by explaining September was the holidays and Remus would remind him that Christmas wasn’t for another few months. But he didn’t feel like striking that kind of conversation today. Normally, he’d have Y/N to back him up.

Remus entered The Three Broomsticks with his spirits a lot higher than they had been a half-hour ago. As much as he renounced being too sure about anything, he was certain he could never be bored when he was with his friends. He prayed nothing would put a damper on his mood, but the world didn’t work the way he wanted. He had heard her before he saw her. The familiar laugh had him looking over his shoulder and following Y/N’s figure from the door.

The Y/H/C haired girl was walking hand in hand with Mason Tomlinson as they looked for a seat in the corner of the establishment. As though she felt eyes on her, she turned to the table the boys sat at and waved kindly. Remus wanted to roll his eyes at her gesture but thought better of it.

“I don’t understand when that even happened,” Sirius mumbled, his eyes still trained on Y/N.

“Apparently they were paired up for a project,” James shook his head slightly before turning to look back at his friends. “You’d think she’d tell her bloody cousin she was seeing someone, wouldn’t you?” Y/N hadn’t been seen by the group of boys as often as they usually did in the past few weeks and Remus could tell it was rubbing James the wrong way. Actually, all of them seemed annoyed by her absence.

“Two weeks… I swear that’s how long the two have known each other,” Peter commented. “Remus, did she ever say anything about him - OUCH!”

All three boys were now staring at Remus with guilty expressions on their faces (except Peter, who seemed to also be holding his leg in pain). Remus simply shook his head and gave him a shrug in response.

“I’m sorry, Remus,” Sirius started and this time Remus didn’t stop his eyes from rolling. “I really did think the two of you were going to get together.” Remus froze, halting the way he was nervously pulling at his napkin under the table. He had expected pitying looks or impetus questions, but he hadn’t expected that. Remus hadn’t expected to be confronted with the exact thought that had been haunting him. When would he learn he really couldn’t expect shit?

“No idea what you mean, mate,” Remus spoke, trying to appear much more nonchalant than he felt. “Haven’t even spoken to her in weeks. Why would we be together?” The three pairs of eyes lingered on him for a moment longer, before Sirius began to nod.

“Right… Well, boys, I think it's time for some more butterbeer.” Remus’ friends continued with their night, but all Remus could do was stare at the manifestation of his nightmares. Y/N had her elbow resting on the table in front of her and was running her hand up and down the length of Mason’s arm. From what Remus could see Mason's other arm was placed against her hip and he was leaning closer. Within moments Remus’ stomach was lurching forward as he watched Y/N’s lips meet with Mason’s to kiss him passionately. If it had been any other person he would’ve been gagging at the crude disregard of their surroundings, but at the current moment, it was as though he was stuck. He couldn’t look away and he couldn’t vomit the sight away. He was stuck watching Y/N crush his heart into pieces without even lifting a finger.

“Don’t stare, Remus,” James’ words could’ve been taken as a joke, but Remus knew why he was saying them. He didn’t want Remus hurting.

“Merlin, I don’t understand what has gotten into her,” Sirius, seemingly not learning from his prior mistake, was looking at Y/N again. “That’s not like her, she doesn’t mouth fuck people in public.”

“Sirius!” James and Remus had yelled at the same time.

“That’s so vulgar!”

“That’s my cousin!”

“Oh please, Moony. Like you don’t have the mouth of a sailor. James, I do apologize for talking about your very innocent cousin that way, but there is no other way to explain whatever that is.” James smacked Sirius on the back of his head and the two began to argue amongst themselves, but Remus was too distracted to care about what they were saying.

Sirius was right. It wasn’t like Y/N to get into a relationship so fast and even more unlike her to be so publicly affectionate. But then again, he wondered how much of that was dependent on who was sitting beside her. Maybe she was only affectionate when it wasn’t him crowding the seat next to her. Did they even know Y/N? Did he know her? Remus thought back to the first time he had ever felt a sense of mutual understanding between the two.

The Gryffindor common room was quieter than usual as a group of five 3rd years faced the welcoming fireplace. Remus, James, Sirius, Peter, and Y/N had opted to stay at Hogwarts instead of going to Hogsmeade that weekend and were glad they had. Other than his friend group, Remus noted that the common room was empty which meant they could do anything without prying eyes. They seized the opportunity by playing Wizard Chess and munching on some leftover candy Y/N had from a previous Hogsmeade trip.

“Bloody hell,” Sirius whined, as he pushed the table in front of him. “How? Again?” Remus just shrugged as he motioned for Peter to take Sirius’ spot across from him. They had all agreed they would have a tournament of sorts and whoever won would get to be the one who executed their next prank. This prank was especially exciting because it was going to be affecting anyone who was innocently spending time in the Slytherin common room next Thursday.

“No way,” Peter tutted, crossing his arms across his chest. “I’m not playing just to lose.”

“Peter, the rules were the winner plays the next contestant,” Remus argued. He knew he was undoubtedly the best at Wizarding Chess amongst the five of them and he took pride in any moments he could use that to his advantage.

“Moons, just let me play Peter,” Sirius started. At Remus’ look of dissent, he continued, “Come on, do you even care about actually being the one that says the incantation?” Remus considered this. He didn’t actually care, but he did want to win.

“No,” The voice came from the body next to him and Remus looked up to see Y/N shaking her head. “You can’t make the rules and then change them just because Remus is better than you.”

“Shut up, you Hufflepuff,” James taunted. The Marauders had often told Y/N she would’ve been suitable for Hufflepuff because of how highly she valued fairness. Even if it was something as small as a game, she wanted to see the right thing done. Remus admired that. He figured if more people did that, the world would be a hell of a better place.

“Eh, let ‘em play. They won’t let me hear the end of it once I win,” Remus uprooted from his spot on the floor and took a seat next to Y/N. The pair sat back as they watched their friends banter and laugh amongst themselves. Remus had only known the lot of them for three years, but he knew that moments like these would be life-altering for him. He had come a long way from the glum eleven-year-old who thought he deserved to be alone. He still battled with whether he deserved the love he received, but he was slowly learning he did. And the only reason he was ever able to get this far in that journey was because of the four smiling idiots around him.

When James began to chase Peter around the common room, Remus turned his face to the side just as Y/N did and the two of them just smiled at each other. It was like they were both thinking the same things, but Remus had no way of knowing. Y/N and he had always been friends, but they rarely spent time alone the way he did with Sirius and the way she did with James. It wasn’t weird, it was just the dynamic of their group. But at that moment, as they laughed with each other, he felt like he had known her for years. He felt like she was agreeing with him on how much these people meant to both of them. He was probably projecting, but it made him feel warm with comfort. At the time he didn’t know that she would soon grow to be one of the closest friends he’d ever have, but he found solace in that random second of certain uncertainty.

tiny little taglist: @kitkatkl

#remus lupin#remus lupin x reader#remus lupin series#remus lupin fanfiction#remus lupin imagine#marauders x reader#marauders imagine#marauders fanfiction#potter!reader#remus lupin x potter!reader#remus lupin angst#andrew garfield#andrew garifield x reader

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bakudeku: A Non-Comprehensive Dissection of the Exploitation of Working Bodies, the Murder of Annoying Children, and a Rivals-to-Lovers Complex

I. Bakudeku in Canon, And Why Anti’s Need to Calm the Fuck Down

II. Power is Power: the Brain-Melting Process of Normalization and Toxic Masculinity

III. How to Kill Middle Schoolers, and Why We Should

IV. Parallels in Abuse, EnemiesRivals-to-Lovers, and the Necessity of Redemption ft. ATLA’s Zuko

V. Give it to Me Straight. It’s Homophobic.

VI. Love in Perspective, from the East v. West

VII. Stuck in the Sludge, the Past, and Season One

Disclaimer

It needs to be said that there is definitely a place for disagreement, discourse, debate, and analysis: that is a sign of an active fandom that’s heavily invested, and not inherently a bad thing at all. Considering the amount of source material we do have (from the manga, to the anime, to the movies, to the light novels, to the official art), there are going to be warring interpretations, and that’s inevitable.

I started watching and reading MHA pretty recently, and just got into the fandom. I was weary for a reason, and honestly, based on what I’ve seen, I’m still weary now. I’ve seen a lot of anti posts, and these are basically my thoughts. This entire thing is in no way comprehensive, and it’s my own opinion, so take it with a grain of salt. If I wanted to be thorough about this, I would’ve included manga panels, excerpts from the light novel, shots from the anime, links to other posts/essays/metas that have inspired this, etc. but I’m tired and not about that life right now, so, this is what it is. This is poorly organized, but maybe I’ll return to fix it.

Let’s begin.

Bakudeku in Canon, And Why Anti’s Need to Calm the Fuck Down

There are a lot of different reasons, that can be trivial as you like, to ship or not to ship two (or more) characters. It could be based purely off of character design, proximity, aversion to another ship, or hypotheticals. And I do think that it’s totally valid if someone dislikes the ship or can’t get on board with his character because to them, it does come across as abuse, and the implications make them uncomfortable or, or it just feels unhealthy. If that is your takeaway, and you are going to stick to your guns, the more power to you.

But Bakudeku’s relationship has canonically progressed to the point where it’s not the emotionally (or physically) abusive clusterfuck some people portray it to be, and it’s cheap to assume that it would be, based off of their characterizations as middle schoolers. Izuku intentionally opens the story as a naive little kid who views the lens of the Hero society through rose colored glasses and arguably wants nothing more than assimilation into that society; Bakugou is a privileged little snot who embodies the worst and most hypocritical beliefs of this system. Both of them are intentionally proven wrong. Both are brainwashed, as many little children are, by the propaganda and societal norms that they are exposed to. Both of their arcs include unlearning crucial aspects of the Hero ideology in order to become true heroes.

I will personally never simp for Bakugou because for the longest time, I couldn't help but think of him as a little kid on the playground screaming at the top of his lungs because someone else is on the swingset. He’s red in the face, there are probably veins popping out of his neck, he’s losing it. It’s easy to see why people would prefer Tododeku to Bakudeku.

Even now, seeing him differently, I still personally wouldn’t date Bakugou, especially if I had other options. Why? I probably wouldn’t want to date any of the guys who bullied me, especially because I think that schoolyard bullying, even in middle school, affected me largely in a negative way and created a lot of complexes I’m still trying to work through. I haven’t built a better relationship with them, and I’m not obligated to. Still, I associate them with the kind of soft trauma that they inflicted upon me, and while to them it was probably impersonal, to me, it was an intimate sort of attack that still affects me. That being said, that is me. Those are my personal experiences, and while they could undoubtedly influence how I interpret relationships, I do not want to project and hinder my own interpretation of Deku.

The reality is that Deku himself has an innate understanding of Bakugou that no one else does; I mention later that he seems to understand his language, implicitly, and I do stand by that. He understands what it is he’s actually trying to say, often why he’s saying it, and while others may see him as wimpy or unable to stand up for himself, that’s simply not true. Part of Deku’s characterization is that he is uncommonly observant and empathetic; I’m not denying that Bakugou caused harm or inflicted damage, but infantilizing Deku and preaching about trauma that’s not backed by canon and then assuming random people online excuse abuse is just...the leap of leaps, and an actual toxic thing to do. I’ve read fan works where Bakugou is a bully, and that’s all, and has caused an intimate degree of emotional, mental, and physical insecurity from their middle school years that prevents their relationship from changing, and that’s for the better. I’m not going to argue and say that it’s not an interesting take, or not valid, or has no basis, because it does. Its basis is the character that Bakugou was in middle school, and the person he was when he entered UA.

Not only is Bakugou — the current Bakugou, the one who has accumulated memories and experiences and development — not the same person he was at the beginning of the story, but Deku is not the same person, either. Maybe who they are fundamentally, at their core, stays the same, but at the beginning and end of any story, or even their arcs within the story, the point is that characters will undergo change, and that the reader will gain perspective.

“You wanna be a hero so bad? I’ve got a time-saving idea for you. If you think you’ll have a quirk in your next life...go take a swan dive off the roof!”

Yes. That is a horrible thing to tell someone, even if you are a child, even if you don’t understand the implications, even if you don’t mean what it is you are saying. Had someone told me that in middle school, especially given our history and the context of our interactions, I don’t know if I would ever have forgiven them.

Here’s the thing: I’m not Deku. Neither is anyone reading this. Deku is a fictional character, and everyone we know about him is extrapolated from source material, and his response to this event follows:

“Idiot! If I really jumped, you’d be charged with bullying me into suicide! Think before you speak!”

I think it’s unfair to apply our own projections as a universal rather than an interpersonal interpretation; that’s not to say that the interpretation of Bakudeku being abusive or having unbalanced power dynamics isn’t valid, or unfounded, but rather it’s not a universal interpretation, and it’s not canon. Deku is much more of a verbal thinker; in comparison, Bakugou is a visual one, at least in the format of the manga, and as such, we get various panels demonstrating his guilt, and how deep it runs. His dialogue and rapport with Deku has undeniably shifted, and it’s very clear that the way they treat each other has changed from when they were younger. Part of Bakugou’s growth is him gaining self awareness, and eventually, the strength to wield that. He knows what a fucked up little kid he was, and he carries the weight of that.

“At that moment, there were no thoughts in my head. My body just moved on its own.”

There’s a part of me that really, really disliked Bakugou going into it, partially because of what I’d seen and what I’d heard from a limited, outside perspective. I felt like Bakugou embodied the toxic masculinity (and to an extent, I still believe that) and if he won in some way, that felt like the patriarchy winning, so I couldn't help but want to muzzle and leash him before releasing him into the wild.

The reality, however, of his character in canon is that it isn’t very accurate to assume that he would be an abusive partner in the future, or that Midoryia has not forgiven him to some extent already, that the two do not care about each other or are singularly important, that they respect each other, or that the narrative has forgotten any of this.

Don’t mistake me for a Bakugou simp or apologist. I’m not, but while I definitely could also see Tododeku (and I have a soft spot for them, too, their dynamic is totally different and unique, and Todoroki is arguably treated as the tritagonist) and I’m ambivalent about Izuocha (which is written as cannoncially romantic) I do believe that canonically, Bakugou and Deku are framed as soulmates/character foils, Sasuke + Naruto, Kageyama + Hinata style. Their relationship is arguably the focus of the series. That’s not to undermine the importance or impact of Deku’s relationships with other characters, and theirs with him, but in terms of which one takes priority, and which one this all hinges on?

The manga is about a lot of things, yes, but if it were to be distilled into one relationship, buckle up, because it’s the Bakudeku show.

Power is Power: the Brain-Melting Process of Normalization and Toxic Masculinity

One of the ways in which the biopolitical prioritization of Quirks is exemplified within Hero society is through Quirk marriages. Endeavor partially rationalizes the abuse of his family through the creation of a child with the perfect quirk, a child who can be molded into the perfect Hero. People with powerful, or useful abilities, are ranked high on the hierarchy of power and privilege, and with a powerful ability, the more opportunities and avenues for success are available to them.

For the most part, Bakugou is a super spoiled, privileged little rich kid who is born talented but is enabled for his aggressive behavior and, as a child, cannot move past his many internalized complexes, treats his peers like shit, and gets away with it because the hero society he lives in either has this “boys will be boys” mentality, or it’s an example of the way that power, or Power, is systematically prioritized in this society. The hero system enables and fosters abusers, people who want power and publicity, and people who are genetically predisposed to have advantages over others. There are plenty of good people who believe in and participate in this system, who want to be good, and who do good, but that doesn’t change the way that the hero society is structured, the ethical ambiguity of the Hero Commission, and the way that Heroes are but pawns, idols with machine guns, used to sell merch to the public, to install faith in the government, or the current status quo, and reinforce capitalist propaganda. Even All Might, the epitome of everything a Hero should be, is drained over the years, and exists as a concept or idea, when in reality he is a hollow shell with an entire person inside, struggling to survive. Hero society is functionally dependent on illusion.

In Marxist terms: There is no truth, there is only power.

Although Bakugou does change, and I think that while he regrets his actions, what is long overdue is him verbally expressing his remorse, both to himself and Deku. One might argue that he’s tried to do it in ways that are compatible with his limited emotional range of expression, and Deku seems to understand this language implicitly.

I am of the opinion that the narrative is building up to a verbal acknowledgement, confrontation, and subsequent apology that only speaks what has gone unspoken.

That being said, Bakugou is a great example of the way that figures of authority (parents, teachers, adults) and institutions both in the real world and this fictional universe reward violent behavior while also leaving mental and emotional health — both his own and of the people Bakugou hurts — unchecked, and part of the way he lashes out at others is because he was never taught otherwise.

And by that, I’m referring to the ways that are to me, genuinely disturbing. For example, yelling at his friends is chill. But telling someone to kill themselves, even casually and without intent and then misinterpreting everything they do as a ploy to make you feel weak because you're projecting? And having no teachers stop and intervene, either because they are afraid of you or because they value the weight that your Quirk can benefit society over the safety of children? That, to me, is both real and disturbing.

Not only that, but his parents (at least, Mitsuki), respond to his outbursts with more outbursts, and while this is likely the culture of their home and I hesitate to call it abusive, I do think that it contributed to the way that he approaches things. Bakugou as a character is very complex, but I think that he is primarily an example of the way that the Hero System fails people.

I don’t think we can write off the things he’s done, especially using the line of reasoning that “He didn’t mean it that way”, because in real life, children who hurt others rarely mean it like that either, but that doesn’t change the effect it has on the people who are victimized, but to be absolutely fair, I don’t think that the majority of Bakudeku shippers, at least now, do use that line of reasoning. Most of them seem to have a handle on exactly how fucked up the Hero society is, and exactly why it fucks up the people embedded within that society.

The characters are positioned in this way for a reason, and the discoveries made and the development that these characters undergo are meant to reveal more about the fictional world — and, perhaps, our world — as the narrative progresses.

The world of the Hero society is dependent, to some degree, on biopolitics. I don’t think we have enough evidence to suggest that people with Quirks or Quirkless people place enough identity or placement within society to become equivalent to marginalized groups, exactly, but we can draw parallels to the way that Deku and by extent Quirkless people are viewed as weak, a deviation, or disabled in some way. Deviants, or non-productive bodies, are shunned for their inability to perform ideal labor. While it is suggested to Deku that he could become a police officer or pursue some other occupation to help people, he believes that he can do the most positive good as a Hero. In order to be a Hero, however, in the sense of a career, one needs to have Power.

Deviation from the norm will be punished or policed unless it is exploitable; in order to become integrated into society, a deviant must undergo a process of normalization and become a working, exploitable body. It is only through gaining power from All Might that Deku is allowed to assimilate from the margins and into the upper ranks of society; the manga and the anime give the reader enough perspective, context, and examples to allow us to critique and deconstruct the society that is solely reliant on power.

Through his societal privileges, interpersonal biases, internalized complexes, and his subsequent unlearning of these ideologies, Bakugou provides examples of the way that the system simultaneously fails and indoctrinates those who are targeted, neglected, enabled by, believe in, and participate within the system.

Bakudeku are two sides of the same coin. We are shown visually that the crucial turning point and fracture in their relationship is when Bakugou refuses to take Deku’s outstretched hand; the idea of Deku offering him help messes with his adolescent perspective in that Power creates a hierarchy that must be obeyed, and to be helped is to be weak is to be made a loser.

Largely, their character flaws in terms of understanding the hero society are defined and entangled within the concept of power. Bakugou has power, or privilege, but does not have the moral character to use it as a hero, and believes that Power, or winning, is the only way in which to view life. Izuku has a much better grasp on the way in which heroes wield power (their ideologies can, at first, be differentiated as winning vs. saving), and is a worthy successor because of this understanding, and of circumstance. However, in order to become a Hero, our hero must first gain the Power that he lacks, and learn to wield it.

As the characters change, they bridge the gaps of their character deficiencies, and are brought closer together through character parallelism.

Two sides of the same coin, an outstretched hand.

They are better together.

How to Kill Middle Schoolers, and Why We Should

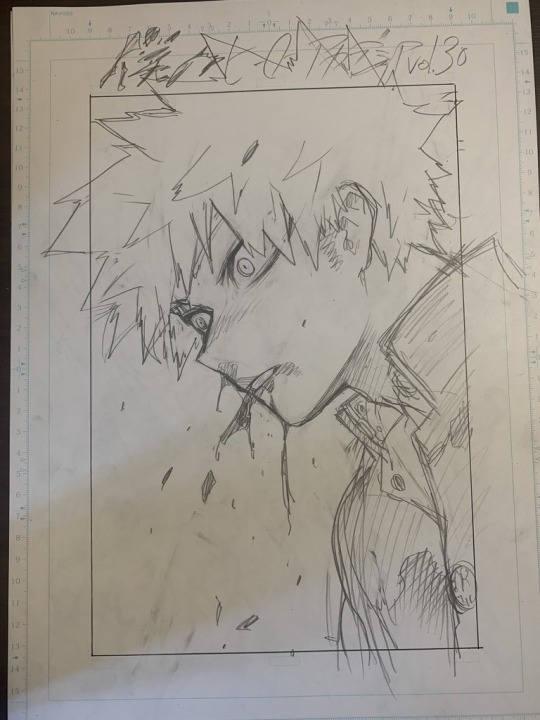

I think it’s fitting that in the manga, a critical part of Bakugou’s arc explicitly alludes to killing the middle school version of himself in order to progress into a young adult. In the alternative covers Horikoshi released, one of them was a close up of Bakugou in his middle school uniform, being stabbed/impaled, with blood rolling out of his mouth. Clearly this references the scene in which he sacrifices himself to save Deku, on a near-instinctual level.

To me, this only cements Horikoshi’s intent that middle school Bakugou must be debunked, killed, discarded, or destroyed in order for Bakugou the hero to emerge, which is why people who do actually excuse his actions or believe that those actions define him into young adulthood don’t really understand the necessity for change, because they seem to imply that he doesn’t need/cannot reach further growth, and there doesn’t need to be a separation between the Bakugou who is, at heart, volatile and repressed the angry, and the Bakugou who sacrifices himself, a hero who saves people.

Plot twist: there does need to be a difference. Further plot twist: there is a difference.

In sacrificing himself for Deku, Bakugou himself doesn't die, but the injury is fatal in the sense that it could've killed him physically and yet symbolizes the selfish, childish part of him that refused to accept Deku, himself, and the inevitability of change. In killing those selfish remnants, he could actually become the kind of hero that we the reader understand to be the true kind.

That’s why I think that a lot of the people who stress his actions as a child without acknowledging the ways he has changed, grown, and tried to fix what he has broken don’t really get it, because it was always part of his character arc to change and purposely become something different and better. If the effects of his worst and his most childish self stick with you more, and linger despite that, that’s okay. But distilling his character down to the wrong elements doesn’t get you the bare essentials; what it gets you is a skewed and shallow version of a person. If you’re okay with that version, that is also fine.

But you can’t condemn others who aren’t fine with that incomplete version, and to become enraged that others do not see him as you do is childish.

Bakugou’s change and the emphasis on that change is canon.

Parallels in Abuse, EnemiesRivals-to-Lovers, and the Necessity of Redemption ft. ATLA’s Zuko

In real life, the idea that “oh, he must bully you because he likes you” is often used as a way to brush aside or to excuse the action of bullying itself, as if a ‘secret crush’ somehow negates the effects of bullying on the victim or the inability of the bully to properly process and manifest their emotions in certain ways. It doesn’t. It often enables young boys to hurt others, and provides figures of authority to overlook the real source of schoolyard bullying or peer review. The “secret crush”, in real life, is used to undermine abuse, justify toxic masculinity, and is essentially used as a non-solution solution.

A common accusation is that Bakudeku shippers jump on the pairing because they romanticize pairing a bully and a victim together, or believe that the only way for Bakugou to atone for his past would be to date Midoryia in the future. This may be true for some people, in which case, that’s their own preference, but based on my experience and what I’ve witnessed, that’s not the case for most.

The difference being is that as these are characters, we as readers or viewers are meant to analyze them. Not to justify them, or to excuse their actions, but we are given the advantage of the outsider perspective to piece their characters together in context, understand why they are how they are, and witness them change; maybe I just haven’t been exposed to enough of the fandom, but no one (I’ve witnessed) treats the idea that “maybe Bakugou has feelings he can’t process or understand and so they manifest in aggressive and unchecked ways'' as a solution to his inability to communicate or process in a healthy way, rather it is just part of the explanation of his character, something is needs to — and is — working through. The solution to his middle school self is not the revelation of a “teehee, secret crush”, but self-reflection, remorse, and actively working to better oneself, which I do believe is canonically reflected, especially as of recently.

In canon, they are written to be partners, better together than apart, and I genuinely believe that one can like the Bakudeku dynamic not by route of romanticization but by observation.

I do think we are meant to see parallels between him and Endeavor; Endeavor is a high profile abuser who embodies the flaws and hypocrisy of the hero system. Bakugou is a schoolyard bully who emulates and internalizes the flaws of this system as a child, likely due to the structure of the society and the way that children will absorb the propaganda they are exposed to; the idea that Quirks, or power, define the inherent value of the individual, their ability to contribute to society, and subsequently their fundamental human worth. The difference between them is the fact that Endeavor is the literal adult who is fully and knowingly active within a toxic, corrupt system who forces his family to undergo a terrifying amount of trauma and abuse while facing little to no consequences because he knows that his status and the values of their society will protect him from those consequences. In other words, Endeavor is the threat of what Bakugou could have, and would have, become without intervention or genuine change.

Comparisons between characters, as parallels or foils, are tricky in that they imply but cannot confirm sameness. Having parallels with someone does not make them the same, by the way, but can serve to illustrate contrasts, or warnings. Harry Potter, for example, is meant to have obvious parallels with Tom Riddle, with similar abilities, and tragic upbringings. That doesn’t mean Harry grows up to become Lord Voldemort, but rather he helps lead a cross-generational movement to overthrow the facist regime. Harry is offered love, compassion, and friends, and does not embrace the darkness within or around him. As far as moldy old snake men are concerned, they do not deserve a redemption arc because they do not wish for one, and the truest of change only occurs when you actively try to change.