#because I assess things for the IUCN

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hello! With the holidays around the corner, I've been trying to think of a gift for my mom who loves colorful tree frogs. As a frog enjoyer, do you have any frog related gifts you'd recommend? Or deets on any gifts linked to habitat conservation funding. Thanks for any advice!

Wellllll… if you can afford it, I happen to sell some froggy things on RedBubble, including some really big transparent treefrog stickers that happen to look very nice on nalgene bottles and cupboards and things…

I am afraid I don't know any links related to conservation funding that are actually genuinely beneficial.

#holidays#redbubble#shameless self promotion#christmas shopping#answers by Mark#significantfoliage#in a way this might be considered to help conservation#because I assess things for the IUCN#and the money I make from RedBubble goes toward keeping me alive and fed and things

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

A couple highlights:

There are now ZERO COAL POWER PLANTS in the UK. Zero! Also zero in Slovakia, which closed its last coal plant a full SIX YEARS ahead of schedule! This is great because coal is like, the dirtiest fuel source ever. It's awful for the planet, it's awful for our lungs, it's just The Worst. Goodbye and good riddance!

Last year, EU CO2 emissions fell by 8%, and the data's not all in for this year yet but they're on track to drop even more. Yeah, you read that right - the EU may have already passed peak carbon emissions. Excuse me while I do a happy dance over here in the corner - this is a BIG FUCKING DEAL!

This may have been a bad year for abortion rights in the US, but we're an outlier - over the past 30 years, we are only one of four countries to tighten abortion restrictions, while 60 countries have made it more available. This year, France became the first country in the whole world to make abortion a constitutional right. Seven US states did so too - Colorado, New York, Maryland, Montana, Nevada, Arizona and Missouri. That's right, Missouri! Shocking, huh?

A drug to prevent HIV infections was 100% effective in trials. That. That's insane. It's not a vaccine, but it is the closest we've ever been to one.

Deaths from tuberculosis, the deadliest infectious disease in the world, hit an all-time global low. Hooray for preventing a truly staggering amount of death!

Egypt and Cabo-Verde both eliminated malaria, and 17 countries started distributing the new malaria vaccine - remember that? Remember how insanely exciting it is that was now have a vaccine for malaria? It is saving lives as we speak.

Deforestation in the Amazon is half what it was two years ago.

The largest dam removal project in history was completed - removing four dams from the Klamath River, thanks to decades of activism by the Karuk and Yurok tribes. A month later, there were salmon spawning in the river basin again - for the first time in a century. Nature's pretty incredible at bouncing back, if we can just give it the chance. I repeat: Largest. Dam removal. In history!

China finished the Great Green Wall

Prewalski's horses returned to their homeland in central Kazakhstan, where they'd been missing for 200 years!

22 endangered species made impressive recoveries - let's hear it for the Saimaa ringed seal, Scimitar oryx, Red cockaded woodpecker, Siamese crocodile, Narwhal, Arapaima, Chipola slabshell and Fat threeridge mussels, Iberian lynx, Asiatic lions, Australian saltwater crocodile, Asian antelope, Ulūlu, Southern bluefin tuna, Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog, Yellow-footed rock wallabies, Yangtze finless porpoise, Pookila mouse, Orange-bellied parrots, Putitor mahseer (this is a fish), Giant pandas, and Florida golden aster!

This year was deeply shitty in a lot of ways - but not all of them.

Edit: a previous version of this post listed 22 endangered species as being no longer endangered, because I misinterpreted the way my source phrased things. I was wrong - unfortunately at least one of these species (the Saimaa seal) is still endangered, however its population reached about 500 individuals, which is a big deal considering there were only about 100 when they were first listed as a protected species, and between 135-190 adults in 2015 when their population was last assessed for the IUCN. That's still pretty impressive! Thanks to @haltijas for the correction!

Would anyone like to join me in my New Year's tradition of reading about good things that happened this year?

#new years#2024#good news#fix the news#let this be a lesson to read your sources carefully lest you have to tell several thousand people on the internet you made a dumb mistake!#please reblog the updated version so I don't have to be responsible for EVEN MORE accidental misinformation

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fact Check #1

I came across this video while scrolling through Instagram not too long ago, and when I was brainstorming on things I could fact check, this came to mind! I found it again through google. If you would like to watch the video for yourself, which comes from Tik Tok, the link is: https://www.tiktok.com/@christalluster/video/7244690898464869675

What is shown in the video, is Christal voicing over a post she came across, basically acknowledging the fact that someone has not seen lightning bugs recently, while agreeing herself. This really sparked my interest since I love lightning bugs. So much that I even have a tattoo of one! Clearly, I had to do some extra research, because I saw this video around a time when I noticed I, too, have not seen lightning bugs in a while. This alone gave me a reason to fact check. I felt like this was definitely something I would like to find out is more serious of a matter. I typed into google, "are lightning bugs going extinct?"

I used the Washington post to fact check, since they are reliable. The article I used was Why fireflies are going extinct and what you can do about it - Washington Post

According to, Grandoni, who wrote this post for the Washington Post, "Nearly 1 in 3 firefly species in the United States and Canada may be threatened with extinction, firefly experts estimate in a recent comprehensive assessment." Lightning bug larvae spends a lot of time underground before coming out in their final form during the summer. "But much of the swampy soil young fireflies need to thrive is increasingly being bulldozed for golf courses, suburban subdivisions and other types of development, making habitat loss a top threat," says Grandoni. Lighting bugs are losing their places to live because of construction, leaving them without homes to live and somewhere to reproduce. Lightning bugs need grass to thrive, as well. I also learned that artificial light, or light pollution is a big contributor to the loss of lightning bugs, too. This can be caused from something as simple as streetlights, so imagine all the damage being caused from bigger things transmitting artificial light. It's also simple to fix this part, though! Just turn off lights when you can! Light tricks lighting bugs into thinking that it is daytime, so they would not come out, since they are a nocturnal insect. The light keeps them from breeding, since it tricks them in a way. "For many fireflies, there is a painful lack of data on even baseline populations. While some species remain abundant, overall, we risk the loss of firefly biodiversity" says Grandoni. Reading that part made me feel a bit better about the issue of not seeing as many, but still skeptical of the fact that we could lose lightning bugs completely as time goes on and deforestation and unnecessary light pollution continues.

I would not say that Christal's post is completely false, since there definitely is a decrease in the overall population of lightning bugs. Some places are not suffering this loss as much as others. The part that is inaccurate is the persons post she voiced over saying that they "disappeared."

So, I wanted to fact check the Washington Post just a bit, for my own comfort and knowledge. I checked out worldanimalfoundation.org. While reading through that, they are not going "extinct", but some can be considered endangered. "They evaluated 128 species and found that 11% of species were threatened with extinction, 2% are near threatened, and 33% were categorized as being “of least concern” for the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List of Threatened Species" according to The World Animal Foundation. They also mentioned a contributor of the overall decrease in lightning bugs, which is pesticides. The Washington Post did not mention this. The World Animal Foundation mentions, "These insecticides can also be harmful when fireflies ingest contaminated prey. Most problematically, aerial sprays of certain insecticides targeting mosquitoes are often conducted at dusk to maximize their efficiency, but this is also when fireflies are most active, placing them at risk." Basically, the pesticides used to rid places of mosquitoes and other harmful pests are of course harming those insects who help. This alone is an issue that could overall contribute to the potential "disappearance" of these insects all together.

I am overall coming to the conclusion that the original Tik Tok post made by Christal is misleading, but not completely false. It did get my mind going with wanting to do my own research to fact check the person's post that she voiced over. I am also glad I did go that extra mile to find out for myself so that I can keep an open mind about things I can do to diminish the risk of losing lightning bugs, and maybe inspire whoever is reading this to do the same.

Works cited:

Grandoni, Dino. “Summer Is Here. Where Are the Fireflies?” The Washington Post, WP Company, 30 June 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/interactive/2023/firefly-summer-extinction/.

“Dimming Lights: Are Fireflies Endangered? What’s Causing Their Decline?” WAF, 7 June 2023, worldanimalfoundation.org/advocate/how-to-help-animals/params/post/1276007/save-the-fireflies.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Feeling very tired this week. I was lucky enough to be able to attend as an observer the resumed 5th Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction at the UN Headquarters in NY this week and last week, minus yesterday because of the snow, with a professor who is a member of the IUCN (NGOs are allowed to attend). The proposed BBNJ Treaty primarily deals with 4 things: marine genetic resources (MGRS), area-based management tools (ABMTs) including marine protected areas (MPAs), environmental impact assessments (EIAs), and capacity building and the transfer of marine technology (CB&TT). These are things that have been largely neglected by UNCLOS, and with climate change, proposed deep seabed mining, and decreasing marine stocks globally it is essential that they be added to it.

Attempts to do so have been ongoing for years. The first working group was established in 2004, and the first ICG meeting was in 2018. The fourth ICG meeting in 2022, which was delayed due to the pandemic, was when delegations submitted textual proposals contributing to the draft text. The fifth meeting was the closest the parties ever came to reaching a consensus, and it resumed this month. I went into it very optimistic, but then basically nothing got done the first week because no one could come to agreement about any of the remaining issues.

But then this week, a lot of people were galvanized by the time running out, and rapid progress was made. However, the member states are still really gridlocking on Marine genetic Resources - particularly, intellectual property rights and tracking collection and utilization. And right now my gut feeling is that if significant leeway on those issues is not reached by tomorrow, there will not be a final draft of the BBNJ for Friday when meeting concludes.

Since I'm just an observer, I’ve only been attending informal informals or “pre-meetings” where the member states make proposals (NGOS can’t make suggestions while there, but they can take notes and draft proposals to submit to the secretariat later). And some of the issues the members will debate for hours are so frustrating. For example, this week hours were spent discussing whether the word “indigenous” should be capitalized in the treaty, with no conclusion. Meanwhile the members of indigenous groups who attended did not care; their main priority was ensuring that they’re in the treaty managing MPAs, having their traditional knowledge included as ABMTS, and not having their access to MGRS cut off. And of course those concerns all got put to the side while capitalization was debated. Which I'm sure was the intent of the member states that kept it going.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Weather Network - Hope for world's bird populations despite recent 'alarming' report

New Post has been published on https://petnews2day.com/pet-news/bird-news/the-weather-network-hope-for-worlds-bird-populations-despite-recent-alarming-report/

The Weather Network - Hope for world's bird populations despite recent 'alarming' report

While it may seem like fate is written for the world’s birds, there are reasons to be optimistic for their populations despite a new report that says one in eight species are threatened with extinction.

The fifth edition of State of the World’s Birds assessment was recently released, addressing the current state of birds across the globe. Other key highlights include data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List that shows nearly half (49 per cent; 5,412) of the world’s bird species are in decline.

SEE ALSO: Scientists figure out how many birds are in the wild. What’s your guess?

The document outlines what the animals tell us about the state of nature and the pressures upon it, as well as the solutions in place and what is needed. It centres on birds because they are an excellent barometer for planetary health, according to BirdLife International, producers of the report.

In a recent interview with The Weather Network, Sam Knight, Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (NCC) national science manager and conservation biologist, said she isn’t surprised by the findings of the report, but she also acknowledged it is “alarming” since the latest document indicates an even further loss of birds since the 2018 edition.

(Nathan Howes)

“There’s [been] a huge jump in the past four years in the number of species that are declining, which tells us that the threats are becoming more and more threatening,” said Knight. “I’m perhaps not surprised at seeing the numbers at face value, but then looking into how much they’ve changed recently really is quite an alarming thing.”

‘We can tackle this problem’

But the BirdLife International report does offer some glimmer of hope, with IUCN data showing 38 per cent of populations (4,234) are stable and six per cent (659) are increasing.

“There are many species that have been brought back from the brink of extinction. People are becoming more and more attuned with nature and willing to do things to support nature,” said Knight.

“I really think that we can tackle this problem.”

(Getty Images)

WATCH: City lights are confusing birds, here’s how to help our feathered friends

There are many things we can do in our own backyard to reduce the threats to our birds. The primary focuses are keeping cats tethered while they’re outdoors or, alternatively, build an enclosure outside so the felines aren’t posing a risk to birds while roaming free. The other idea is to proof the home’s windows, Knight noted.

In Canada alone, the BirdLife report says an estimated 100-350 birds are killed by cats — an invasive species — annually, while approximately 16-42 million of them die in collisions with buildings each year. Birds are disoriented by reflections of open sky or vegetation during the day and artificial light at night.

“Birds are at risk of hitting windows, especially because they don’t understand that the reflection of trees and sky isn’t real,” said Knight. “You can actually put some little patterns or markings all over your windows to be able to reduce that threat on a personal level around your house.”

Another thing people can do is plant native plants and create gardens that have flowers that bloom from early in the spring until late into the fall, in an effort to support our pollinators, she said.

(Videoblocks)

“Native plants are generally more beneficial than a lot of our garden varieties because garden varieties have often been bred to look good, but it often means they lose some of their nutritional value or some of their nectar sources, for example,” said Knight. “And the pollinators [also] appreciate having sources that they know are local.”

As well, supporting organizations such as the NCC, either through volunteer work or a donation, is helpful as it needs assistance to be able to do its work, she added.

WATCH: How birds are adapting and lowering risk of extinction

Numerous reasons attributed to decline

Going back more than 50 years, North America has lost nearly 3 billion birds (29 per cent) since 1970. The report stated these disappearances have been most “severe” in species found in grasslands and those that migrate, with 419 species losing 2.5 billion individuals and 31 species losing 700 million individuals.

Some of the biggest reasons for the dwindling of the populations include degraded or loss of habitats, logging, pollution, climate change and invasive species, among others.

Out of the aforementioned factors, habitat loss and degradation can be blamed for the biggest losses, the NCC national science manager said, so more needs to be done to prevent them.

She acknowledged the Canadian government’s current commitment of protecting 30 per cent of terrestrial lands and waters by 2030 in its 30-by-30 initiative as an example of what the country is doing to help biodiversity.

(Jensen Edwards/Nature Conservancy of Canada)

“So, they have this goal in mind, but they can’t tackle this alone. That’s where we come in…to be able to help them do this and be able to conserve land we work with,” said Knight. “It’s not just the government that has to tackle that problem.”

The report should also be of concern to people outside of the scientific community because birds play important roles in our ecosystems, Knight said. They are predators that kill agricultural pests, they’re pollinators, and they are peaceful and enjoyable to watch for millions of people.

Because of how widely distributed birds are, it is simple to survey them and they are highly responsive to environmental change, she said. “If we know that birds aren’t doing so well, this is probably revealing some wider trends in biodiversity loss,” said Knight.

UN conference is a ‘good opportunity’ to start doing more

In December, the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) will be meeting in Montreal to focus on protecting nature and halting biodiversity loss around the world.

(Getty Images/Brian E. Kushner)

“I’m encouraged by what is going to happen at the United Nations conference in Montreal. I think we have a really good opportunity over the next few months to mobilize and start doing more to support,” said Knight.

The gathering is going to be a critical juncture to set environmental priorities for the near future, so everyone will be looking to Montreal to see what we come up with, the NCC biologist stated.

“Anything that is improved for nature, [such as] reducing habitat loss and reversing it, will help birds at the end of the day,” said Knight. “Also, by doing things like improving habitat in our own backyard, we can at least support the birds that are still around, which is great, even if we’re not really doing quite as much to stop the main threats.”

WATCH: Study finds ‘The Blob’ responsible for the death of millions of birds

Thumbnail courtesy of Jason Bantle/Nature Conservancy of Canada.

Follow Nathan Howes on Twitter.

0 notes

Photo

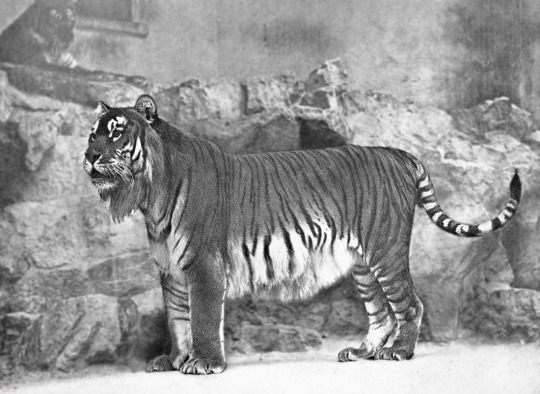

Endangered Felines, part 1

Tiger, Panthera tigris

Without a doubt one of the most iconic and recognizable animals on Earth, the tiger was voted the world’s favorite animal in 2004, with the domestic dog coming in second, and dolphins third.

I was planning on splitting tigers into one post per subspecies, but since there are sadly so many cat species that are endangered, this series will be long enough already, and it gives a better overview to have them all in one post.

And just as I was researching for this post, it turns out that in 2017, the tiger was reduced to a mere two subspecies - the mainland (P. t. tigris), and the Sunda Island (P. t. sondaica) populations - but this is disputed, as there are morphological and genetic differences between these populations. In this post, I will treat them all as their own subspecies.

While at first I was a bit skeptical about the switch to now only having two tiger subspecies when I think about it more, it's actually great for tiger conservation, because that means we don't have to be "subspecies purists" anymore. This means we can repopulate areas with another population easier, without claims of "it's an invasive/foreign animal".

While I will try to keep each topic brief, this will still be a lengthy and exhaustive post, as you can’t simply brush over things in the most beloved and famous endangered animal on Earth.

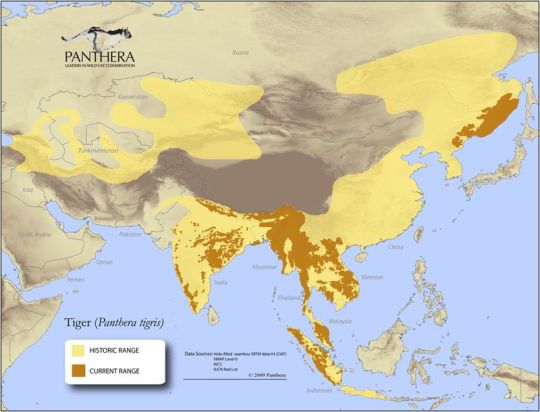

This is the historic range of all tigers. From the far northeast of Russia to the east of the Black Sea, by Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, all the way to the far southern islands of Java and Bali.

Today, they have been extirpated from most of their range, with three of the nine former subspecies extinct. By 2017, there were just under 4000 tigers in the wild combined, and that is after a recent rise in numbers, for the first time in over a century. A couple of hundred years ago, there were at least 40 000 tigers in India alone.

They are estimated globally to have numbered around 100 000 in the year 1900, meaning 97% of tigers were lost in a century.

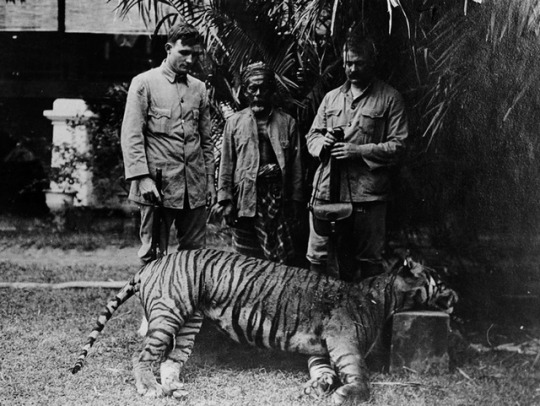

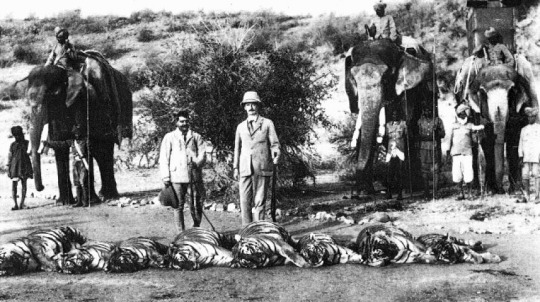

Occasionally hunted throughout history, either because of fear, sport among the wealthy or for their parts, tiger hunts took on a new dimension when Europeans colonized India and other parts of South Asia, with "gentlemen sports hunters" proudly subduing nature. And later in the 20th and 21st centuries, mainly poaching for body parts used in "traditional medicine".

An Indian tiger hunt carried out by Lord Reding, Viceroy of India, likely in the mid-1920s.

Direct hunting is not the only threat against tigers, as the human population in Southeast Asia has exploded over the past century, and today, there is nowhere left for wildlife to go.

The tiger has been listed as endangered under the IUCN, consistently since its first assessment in 1986.

Bengal tiger, Panthera tigris tigris

The Bengal is without a doubt the most well-known of all tiger subspecies, not the least due to our strong association of tigers with Indian culture. They are also the most numerous tiger population today.

They are 90-110 cm tall at the shoulders and weigh up to 325 kg, with males averaging 235 kg, and females ranging from 116-164 kg.

Given a separate assessment by the IUCN in 2008, the Bengal tiger is considered endangered. Today, they number around 2300 animals in the wild, 1700 of which are in India, 440 in Bangladesh, 200 in Nepal, and 75-100 in Bhutan.

The population is severely fragmented, and no subpopulation contains more than 250 animals. Despite cautiously optimistic news a couple of years ago, they are still considered "decreasing".

If 40 000 was the original number of tigers in India, today, there are only 4% left, and it is still the biggest stronghold of wild tigers anywhere.

Amur tiger, P. t. altaica

More famously known as Siberian tiger, this name is inaccurate as they don't live anywhere near Siberia, which is a large chunk of eastern Russia, having no eastern coastline. While the tiger lives in the very far southeast, near Korea. They are also known as the Manchurian, Ussurian and Korean tiger.

As can be seen on the map above however, they did have a far larger range before widespread hunting nearly wiped them out.

The largest cat on Earth today (after the extinction of the Caspian tiger), they are the second most numerous tiger population, at around 500 animals in the wild (in 2005, they were estimated at 360). They were saved on the brink of extinction, as only a couple of dozen animals remained when they were finally protected.

Despite this vast increase however, the effective population size is only equivalent to around 30 animals, which is close to the total world population when they were saved from extinction. This is due to inbreeding from a smaller and smaller population that then had only a handful of already related animals to rebound from.

It was in the early 20th century that the Amur tiger was nearly wiped out, due to the massive societal change that was going on in Russia at the time. Armies on both sides of the civil war based in Vladivostok made it their mission to kill as many tigers as they could.

Tigers were extirpated from the Korean peninsula by the Japanese in the same period, when Japan occupied Korea. Today, South Korea is working on once again creating a home for the Amur tiger in their lands.

The Soviet Union finally banned tiger hunting in 1947, after which anti-poaching control was very strict. Cubs kept being live-caught well into the 1960s however.

In the middle of the 1900s, deer populations fell in the Amur tiger's range, leaving them no choice but to find other prey. Bizarrely, more than 30 cases of tigers attacking bears were recorded, and bear hair was found in tiger droppings.

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent economic and societal collapse, people were free to poach tigers again, with some doing it to sell to the Chinese market. Today however, the population is stable, but vulnerable.

In 1965, it was given the listing of "status inadequately known", and this was not changed until 1996, when they were assessed as "critically endangered". This laster until 2008, when they were moved to endangered.

At present, there are about as many Amur tigers in human care as there are in the wild, totalling about 1000 Amur tigers on the planet. The zoological population has a higher genetic diversity than wild tigers, as the foundation stock was largely caught when tigers were more numerous in the wild.

Sumatran tiger, P. t. sumatrae

The Sumatran is the one tiger that I personally can recognize easily, due to their striking and bold facial pattern. They are among the smallest tigers alive today, with males reaching only 140 kg - this is a size similar to jaguars. They are also the only Indonesian or Sunda island tiger still in existence.

The Sumatran tiger has been consistently listed as critically endangered since their first assessment in 1996.

They number approximately 500-600 animals, not including ones in zoos and other collections.

Their threats are mainly a shrinking habitat due to palm oil and Acacia plantations leading to a depletion of prey, as well as poaching for their body parts.

Malayan tiger, P. t. jacksoni

Although recent research has discovered that there is no real difference between this and the Indochinese tiger, it was considered its own subspecies since a DNA analysis in 2004, until the recent merge where all mainland tigers are considered P. t. tigris.

Subspecies or subpopulation, the Malayan tiger was listed as “endangered” in 2008, and in 2014, it was reassessed under its current listing as critically endangered.

This was because they had declined by 25% in only one generation (7 years).

In the 1950s, there were about 3000 Malayan tigers. In the 1990s, there were 500, and in 2013, they were estimated at 250-340 animals. This gives an estimate of only around 100 breeding adults in the wild.

The total number in human care is difficult to get to, but apparently in 2011, there were 54 Malayan tigers in American zoos alone, spread across 25 facilities.

The Malayan tiger's habitat has shrunk from nearly 100 000 square kilometers before 1970s, to less than 45 000 square kilometers in 2014. Aside from this threat, is of course poaching for body parts for a Chinese market. Between the years 2000-2013, body parts equating to 1425 tigers had been seized, 94 of these being Malayan tigers.

The Global Tiger Recovery Program, made up of 13 countries where tigers live, set a goal in 2010 to double their tiger populations by 2022. Malaysia had made a similar promise before this agreement, in 2009, with their National Tiger Conservation Action Plan setting to doubling Malaysia's tiger population by 2020.

With the new population estimate of 250-340 adult Tigers and diminishing prey base and natural forests, it is biologically impossible to reach the NTCAP target by 2020.

Indochinese tiger, P. t. corbetti

The Indochinese tiger lives in Southeast Asia, and is viewed as the ancestor of all tigers, the other subspecies diverging around 72 000-108 000 years ago.

They are functionally extinct in Vietnam, Cambodia and possibly China, and number around 300-400 animals in total, the largest population being in Thailand.

They have been listed as endangered since 2008.

They are the least represented in zoos out of all tiger subspecies, and no coordinated breeding program exists. Approximately 14 zoo tigers have been discovered to be Indochinese after DNA analysis of 105 animals in 14 countries.

South China tiger, P. t. amoyensis

This is the most threatened tiger subspecies as they are believed to be extinct in the wild, since the last time one was live-caught in the 1970s.

Only 20 years earlier, they numbered more than 4000 animals, but then came Mao Zedong's "Great Leap Forward", when all wildlife stood in the way of "progress" (remember the Baiji).

Large-scale government anti-pest campaigns took off, and tigers were massacred, mercilessly. This was made worse by deforestation, heavy settling of the countryside from the cities (as part of the GLF) and over-hunting of their prey.

By 1973, they were partially protected, and by 1977, hunting was completely prohibited.

By the early 1980s, they were estimated at 150-200 animals, though not one tiger has been seen since the early 70s.

They are considered critically endangered, possibly extinct in the wild, but there is hope there still are a handful of tigers holding on in the wilds of China. For example, in 2007, a bear and a cow were killed by what was most likely a tiger.

In 2005, the entire zoological population numbered 57 animals descended from only six tigers. Despite being inbred and suffering poor breeding success as a result, DNA tests showed many aren’t pure South China tigers anyway. Another estimate (made difficult by crossbreeding) in 2007 put the global zoological population at 72 animals.

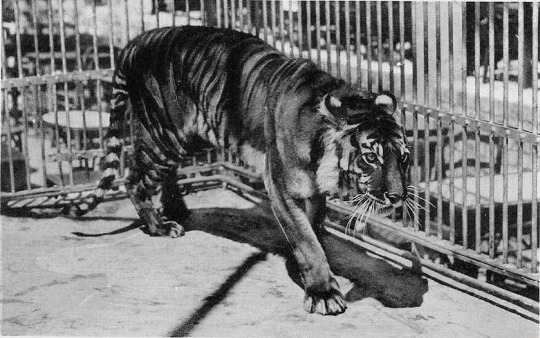

Bali tiger, P. t. balica

The Bali tiger, formerly inhabiting only the island of Bali since 12 000 - 13 000 years back, was the smallest of all tigers, with males only reaching up to 100 kg and females 80 kg, putting this tiger around the same size as a jaguar or cougar.

They were only listed as extinct by the IUCN as late as 2008, but the last one probably died just after the second world war, with the last known tigers recorded in the 1930s.

The Bali tiger was killed off through a lethal cocktail of environmental destruction (palm plantations and rice fields) and sports hunting by the Dutch colonizers. The West Bali National Park was established in 1941, but it came too late to save the tiger.

This animal was never filmed alive nor held in zoos (though it seems the Ringling Bros Circus had one), and it is very difficult to even find photos of live animals.

Javan tiger, P. t. sondaica

The Javan tiger was small, but just larger than the Bali, and similar in size to the still living Sumatran. They were notable in appearance by often having very sparse stripes around the front legs and shoulders.

This population was pronounced extinct by the IUCN in 2003, but the last confirmed sighting was recorded as far back as 1976. Several accounts of alleged sightings exist however, even within the last ten years, including a person supposedly being killed by a tiger in 2008.

In 2017, a blurry image surfaced of what was supposedly a Javan tiger. It was however most likely a Javan leopard, also a critically endangered cat.

We can always hope at least some of these alleged sightings were of tigers, but there is always the possibility that the animals witnessed were actually leopards.

At the turn of the last century, 28 million people lived on Java, while today, it is a jaw-dropping 145 million (resulting in a mind-blowing population density of 1.121 people per square kilometer - in comparison, the state of New York has a population denity of 416 people per square kilometer).

By the middle of the 1800s, people considered tigers a plague, and by the turn of the century, 150% more land had to be cleared for agriculture in only 15 years. By 1975, only 8% of the island's forests remained.

These tigers were poisoned, hunted, their main prey nearly died out, and the forests were cleared for lumber and agriculture.

To make things even worse, World War 2 happened, so the few that were kept in zoos were lost. After the war, it was easier to obtain Sumatran tigers, so none were taken from Java.

A funny thing to note is how the Javan people’s fear of the tiger led them to always referring to it as “Mr. Tiger”. They thought that if they spoke of it in a casual way, the tiger might hear them and take revenge.

Caspian tiger, P. t. virgata

Like the Javan tiger, the Caspian was pronounced extinct by the IUCN in 2003, but the last record was in the early 1970s, and it died out some time during this decade.

It was possibly the largest cat in the world during recorded human history, after the ice age extinction of the cave lion.

It lived across parts of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, eastern Turkey, northern Iran, parts of Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, even well into western China.

The last tiger in Georgia was shot in 1922, they were last recorded in Kazakhstan in 1948, one of the last in Iran was shot in 1953, the last in Turkmenistan was killed in 1954.

Tigers were killed both for sport and as pest control, including by the Soviet army. Up until World War 1, about a hundred tigers were killed in a forest area of the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border - every year. To make matters worse, their natural prey (pigs) declined heavily in the early 1900s due to overhunting and disease, and agriculture destroyed much of the tiger's natural habitat.

While this unique population is gone forever, there are plans to perhaps one day restock the area with Amur tigers, the closest living analogue to the Caspian tiger.

In a day when habitats are shrinking, other habitats may open up, and this could give the Amur tiger a greater hope to continue into the future.

The “there are more tigers in people’s backyards / basements than in the wild”-myth

More of a misrepresentation than a myth, it is true that there are more tigers in human care across the globe than there are in the wild. This is nothing strange for such an endangered animal.

The Scimitar-horned oryx, for example, was up until a couple of years ago extinct in the wild. There are now a few dozen roaming completely wild, while there are up to 11 000 of the antelopes in Texas alone.

The Eastern Bongo numbers around 400 animals in American collections alone, four times the population remaining in the wild!

The Przewalski's horse numbers around 2000 animals, and although many live in free-ranging reserves, only around 400 are considered truly wild and living in their native habitat, after reintroduction programs.

The Père David’s deer was extinct in the wild until some animals escaped and formed a population now some 700 strong, but it's still far outnumbered by the zoological population.

The blue-throated macaw numbers only around 300 animals in the wild, and the World Parrot Trust previously said there were "up to a thousand" in cages.

The Spix’s macaw numbers around 130 birds in human care, and was considered extinct in the wild since the last known bird disappeared in 2000, until one was discovered in 2016. If there are more in the wild, it is only a handful of scattered individuals.

The Hawaiian crow is extinct in the wild since 2002, with just over 100 birds in human care.

The Socorro dove has been extinct in the wild since 1972, with 150 birds alive today, all in cages.

The Guam rail is extinct in the wild since 1987, with some 160 birds alive in zoological facilities.

The orange-bellied parrot numbers around 340 in human care, with less than 20 in the wild.

It is however not true that there are more tigers in America than in the wild, let alone "in people's basements".

That claim is completely absurd, and while sometimes tigers are abused and neglected as with all animal species, that is extremely rare and would be far more common in their native Asia than in America.

According to the Feline Conservation Federation, the United States held just under 2900 tigers in 2011. In contrast, a decade ago in China, there were over 4000 tigers in human care in that country alone. The IUCN states (unknown date) that there are some 6000 tigers in China, mainly farmed for body parts.

We can debate the ethics of these various tiger facilities, but a large number also live in zoos and conservation centers. There is no such thing as several thousand "pet tigers" living in people's living rooms, backyards, or basements.

Privately owned tigers in America, courtesy of the Feline Conservation Federation.

But what the popular media likes to do, other than misrepresent the numbers (and say there are "10 000 pet tigers in American backyards" or some such nonsense), they also like to say that it's this vast number in human care ("captivity") that is the problem!

When people hear for example that there are 3000 tigers in the wild and 5000 or something in America, they seem to think America "stole" those tigers from the wild, and they must be put back! While in reality, tigers in the west have spent decades and generations on the continent, in zoos, circuses, and private collections.

And if you could take America's 2900 tigers and release them all, say hypothetically that it was allowed (many are not "pure") and that they could all survive in the wild. The threats on tigers in the wild, from poaching and habitat destruction, is still nowhere near gone.

So then we could have 5900 tigers for a while, and then a decade or two later, we'd be right back at 3000 again, with NOT ONE tiger alive in American breeding programs. Now who would that help?

That there are more tigers in human care than in the wild is a tragedy of the wild, not of "captivity".

In conclusion

Tigers are the most beloved endangered animal on the planet, and given both their popularity as well as their comparatively vast numbers in human care, the species stands a good chance at surviving indefinitely.

Whether that will only be in zoos, farms and other collections for the foreseeable future, or whether our children and grandchildren will have a chance to see tigers roaming freely in their natural habitats, free from persecution, is another question.

http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/15955/0

https://wildfact.com/forum/topic-on-the-edge-of-extinction-a-the-tiger-panthera-tigris?page=17

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/dec/06/davidward

http://www.prweb.com/releases/2011/9/prweb8805806.htm

http://www.prweb.com/releases/2011/9/prweb8840075.htm

https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2015/02/21/is-extinct-forever-central-asias-caspian-tiger-traverses-the-comeback-trail/

https://www.inverse.com/article/26481-caspian-tigers-extinct-central-asia-amur-kazakstan

https://asiancorrespondent.com/2018/04/south-korea-to-open-asias-largest-tiger-forest/

#Endangered Felines#tiger#Bengal tiger#Amur tiger#Siberian tiger#Sumatran tiger#Malayan tiger#Indochinese tiger#South China tiger#Bali tiger#Javan tiger#Caspian tiger#extinct animals#poaching#deforestation#Big Cat Rescue#BCR#pet tigers#pet tiger#exotic pets#Feline Conservation Federation

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

@aquadraco20 replied:

"Cant you report this somewhere? Doesnt this violate the endangered species act? Or local laws regarding endangered species? Maybe the local park ranger could do something?"

Unfortunately, no, it doesn't. In the U.S., imperiled species are only protected if they are federally listed (or listed within individual states) via the Endangered Species Act (U.S. native species) or listed via CITES (international species).

For international fish imports like these, we need to look at CITES Appendices I, II, and III. Note that the different appendices afford different levels of protection. For example, we still have tank-raised Hypancistrus zebra in the trade because they are only listed in Appendix III, but there are reports that Brazil is proposing elevating it up to Appendix I.

CITES lists very few fishes. They are upping the listed sharks, at least - see most subheadings under "CLASS ELASMOBRANCHII". This does include many freshwater rays. But very few freshwater bony fishes are listed, especially when you consider how massive that group is. I see a total of 12 freshwater bony fishes. (I am including anadromous/catadromous fishes as freshwater fishes here.)

When I say that these fishes are "critically endangered", I'm referring to a status assigned to them by the IUCN Red List.

Red List assessors, species experts that are often scientists, assess species and determine their conservation status, with the intent to try to assess as many species, globally, as possible. To my knowledge, this is the only international effort even considering which species might be under threat.

This list helps inform the other conventions and regulatory bodies, but in the U.S., it holds no power on its own.

These are not the only imperiled fishes in the aquarium trade, these are just some I am very familiar with. My Pseudomystus heokhuii are also listed as Endangered (listed since I got them), but I am still seeing them crop up more and more on online stock lists.

There are a lot of hobbyists that feel that having these fishes in the trade isn't a bad thing, because they are uncommonly imported so the hobby isn't the reason they are declining. They feel that the aquarium trade is just a drop in the bucket. It's true that, for both the Parosphromenus spp. and my Pseudomystus heokhuii, the real threat is habitat destruction for anthropogenic land use.

But I still don't like to see specimens going to brick and mortar stores where the customers who buy them won't know what they're getting and won't try to spawn them. Unfortunately, there's not really anything that can be done about it without federal regulation, which is unlikely to happen.

I visited a nearby city and stopped in a fish store that had four "species" of Parosphromenus (one undescribed, under a trade name).

I couldn't just leave, so I took home the pair they had of the species highest on the ranking list I'd made previously which also happened to be a critically endangered species. (Parosphromenus gunawani, if they were identified correctly. I'll sort it out when I get a chance to get a better look at them.)

I wish I could have taken the others too - some species had larger groups, and I would have bought every individual they had of any species I bought. But I wasn't prepared for that, I'm limited on tank space in my current living situation and only had one cycled filter ready.

All Parosphromenus are imperiled, they are endemic to niche specialized habitats that are under anthropogenic threat. They have no business in the aquarium trade, and certainly not in brick and mortar shops like this. Another customer was trying to get them to sell him moderately sized catfishes for his one gallon "tank". Anyone could walk in and buy these, with no intention of spawning them, no idea what they are.

I mentioned to the shop owner that they were imperiled and he clearly had no qualms about that, but was more so bothered that I brought it up.

The other Parosphromenus they had were:

P. nagyi

P. ornaticauda

P. sp. "Sentang"

#ive read a lot of scientific literature on the aquarium trade too#there are definitely positives#but i dont like#the lack of regulation#if we care about these fishes we need to care about the ones in wild too#not just the ones we keep in our tanks

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Behalf of Environmentalists, I Apologize For the Climate Scare

"Climate change is happening. It’s just not the end of the world. It’s not even our most serious environmental problem"

— Michael Shellenberger | August 1, 2020 | Anti-Empire | Quillette

On behalf of environmentalists everywhere, I would like to formally apologize for the climate scare we created over the last 30 years. Climate change is happening. It’s just not the end of the world. It’s not even our most serious environmental problem. I may seem like a strange person to be saying all of this. I have been a climate activist for 20 years and an environmentalist for 30.

But as an energy expert asked by Congress to provide objective expert testimony, and invited by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to serve as expert reviewer of its next assessment report, I feel an obligation to apologize for how badly we environmentalists have misled the public.

Here are some facts few people know:

Humans are not causing a “sixth mass extinction”

The Amazon is not “the lungs of the world”

Climate change is not making natural disasters worse

Fires have declined 25 percent around the world since 2003

The amount of land we use for meat—humankind’s biggest use of land—has declined by an area nearly as large as Alaska

The build-up of wood fuel and more houses near forests, not climate change, explain why there are more, and more dangerous, fires in Australia and California

Carbon emissions are declining in most rich nations and have been declining in Britain, Germany, and France since the mid-1970s

The Netherlands became rich, not poor while adapting to life below sea level

We produce 25 percent more food than we need and food surpluses will continue to rise as the world gets hotter

Habitat loss and the direct killing of wild animals are bigger threats to species than climate change

Wood fuel is far worse for people and wildlife than fossil fuels

Preventing future pandemics requires more not less “industrial” agriculture

I know that the above facts will sound like “climate denialism” to many people. But that just shows the power of climate alarmism.

In reality, the above facts come from the best-available scientific studies, including those conducted by or accepted by the IPCC, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and other leading scientific bodies.

Some people will, when they read this, imagine that I’m some right-wing anti-environmentalist. I’m not. At 17, I lived in Nicaragua to show solidarity with the Sandinista socialist revolution. At 23 I raised money for Guatemalan women’s cooperatives. In my early 20s I lived in the semi-Amazon doing research with small farmers fighting land invasions. At 26 I helped expose poor conditions at Nike factories in Asia.

I became an environmentalist at 16 when I threw a fundraiser for Rainforest Action Network. At 27 I helped save the last unprotected ancient redwoods in California. In my 30s I advocated renewables and successfully helped persuade the Obama administration to invest $90 billion into them. Over the last few years I helped save enough nuclear plants from being replaced by fossil fuels to prevent a sharp increase in emissions.

But until last year, I mostly avoided speaking out against the climate scare. Partly that’s because I was embarrassed. After all, I am as guilty of alarmism as any other environmentalist. For years, I referred to climate change as an “existential” threat to human civilization, and called it a “crisis.”

But mostly I was scared. I remained quiet about the climate disinformation campaign because I was afraid of losing friends and funding. The few times I summoned the courage to defend climate science from those who misrepresent it I suffered harsh consequences. And so I mostly stood by and did next to nothing as my fellow environmentalists terrified the public.

I even stood by as people in the White House and many in the news media tried to destroy the reputation and career of an outstanding scientist, good man, and friend of mine, Roger Pielke, Jr., a lifelong progressive Democrat and environmentalist who testified in favor of carbon regulations. Why did they do that? Because his research proves natural disasters aren’t getting worse.

But then, last year, things spiraled out of control.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said “The world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change.” Britain’s most high-profile environmental group claimed “Climate Change Kills Children.”

The world’s most influential green journalist, Bill McKibben, called climate change the “greatest challenge humans have ever faced” and said it would “wipe out civilizations.” Mainstream journalists reported, repeatedly, that the Amazon was “the lungs of the world,” and that deforestation was like a nuclear bomb going off.

As a result, half of the people surveyed around the world last year said they thought climate change would make humanity extinct. And in January, one out of five British children told pollsters they were having nightmares about climate change. Whether or not you have children you must see how wrong this is. I admit I may be sensitive because I have a teenage daughter. After we talked about the science she was reassured. But her friends are deeply misinformed and thus, understandably, frightened. I thus decided I had to speak out. I knew that writing a few articles wouldn’t be enough. I needed a book to properly lay out all of the evidence.

And so my formal apology for our fear-mongering comes in the form of my new book, Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All. It is based on two decades of research and three decades of environmental activism. At 400 pages, with 100 of them endnotes, Apocalypse Never covers climate change, deforestation, plastic waste, species extinction, industrialization, meat, nuclear energy, and renewables.

Some highlights from the book:

Factories and modern farming are the keys to human liberation and environmental progress

The most important thing for saving the environment is producing more food, particularly meat, on less land

The most important thing for reducing air pollution and carbon emissions is moving from wood to coal to petroleum to natural gas to uranium

100 percent renewables would require increasing the land used for energy from today’s 0.5 percent to 50 percent

We should want cities, farms, and power plants to have higher, not lower, power densities

Vegetarianism reduces one’s emissions by less than 4 percent

Greenpeace didn’t save the whales, switching from whale oil to petroleum and palm oil did

“Free-range” beef would require 20 times more land and produce 300 percent more emissions

Greenpeace dogmatism worsened forest fragmentation of the Amazon

The colonialist approach to gorilla conservation in the Congo produced a backlash that may have resulted in the killing of 250 elephants

Why were we all so misled?

In the final three chapters of Apocalypse Never I expose the financial, political, and ideological motivations. Environmental groups have accepted hundreds of millions of dollars from fossil fuel interests. Groups motivated by anti-humanist beliefs forced the World Bank to stop trying to end poverty and instead make poverty “sustainable.” And status anxiety, depression, and hostility to modern civilization are behind much of the alarmism.

Once you realize just how badly misinformed we have been, often by people with plainly unsavory or unhealthy motivations, it is hard not to feel duped. Will Apocalypse Never make any difference? There are certainly reasons to doubt it.

The news media have been making apocalyptic pronouncements about climate change since the late 1980s, and do not seem disposed to stop. The ideology behind environmental alarmism—Malthusianism—has been repeatedly debunked for 200 years and yet is more powerful than ever.

But there are also reasons to believe that environmental alarmism will, if not come to an end, have diminishing cultural power. The coronavirus pandemic is an actual crisis that puts the climate “crisis” into perspective. Even if you think we have overreacted, COVID-19 has killed nearly 500,000 people and shattered economies around the globe.

Scientific institutions including the World Health Organisation and IPCC have undermined their credibility through the repeated politicization of science. Their future existence and relevance depends on new leadership and serious reform. Facts still matter, and social media is allowing for a wider range of new and independent voices to outcompete alarmist environmental journalists at legacy publications.

Nations are reverting openly to self-interest and away from Malthusianism and neoliberalism, which is good for nuclear and bad for renewables. The evidence is overwhelming that our high-energy civilization is better for people and nature than the low-energy civilization that climate alarmists would return us to.

The invitations from IPCC and Congress are signs of a growing openness to new thinking about climate change and the environment. Another one has been to the response to my book from climate scientists, conservationists, and environmental scholars. “Apocalypse Never is an extremely important book,” writes Richard Rhodes, the Pulitzer-winning author of The Making of the Atomic Bomb. “This may be the most important book on the environment ever written,” says one of the fathers of modern climate science Tom Wigley.

“We environmentalists condemn those with antithetical views of being ignorant of science and susceptible to confirmation bias,” wrote the former head of The Nature Conservancy, Steve McCormick. “But too often we are guilty of the same. Shellenberger offers ‘tough love:’ a challenge to entrenched orthodoxies and rigid, self-defeating mindsets. Apocalypse Never serves up occasionally stinging, but always well-crafted, evidence-based points of view that will help develop the ‘mental muscle’ we need to envision and design not only a hopeful, but an attainable, future.”

That is all I hoped for in writing it. If you’ve made it this far, I hope you’ll agree that it’s perhaps not as strange as it seems that a lifelong environmentalist, progressive, and climate activist felt the need to speak out against the alarmism.

I further hope that you’ll accept my apology.

— Source: Quillette

1 note

·

View note

Link

For the longest time, I boycotted palm oil. Palm oil is notorious for destroying the habitats of wildlife, especially endangered orangutans. Of course it makes sense not to support a product that is so environmentally destructive. This seems so easy and straightforward! But so much in conservation is not straightforward and I was pretty shocked to find out that what I was doing could actually be worse for wildlife.

Palm oil is a direct threat to all of these species plus more. How could anyone advocate for it? Image from the IUCN.

This blog post outlines my thought process leading to that decision and provides you with resources to make your own. Not all conservationists agree with me, and when I posted about this on Instagram and Twitter, I did get some pushback.

Photo of a palm oil plantation meeting forest. From the IUCN.

Why is Palm Oil Bad for the Environment?

I recently went to Borneo, Malaysia and saw the palm oil plantations for myself. I visited a rainforest reserve called Deramakot, home to orangutans, clouded leopards, and gibbons. On the way to the reserve, we saw miles and miles of palm oil plantations.

Basically, the palm oil industry clear cuts primary forests for palm oil plantations thereby removing habitat for endangered species like orangutans. Where once stood forests, now stands monocultures of palm oil trees.

The palm oil tree is actually native to Africa, but most of the world’s supply (~85%) is grown in Malaysia and Indonesia, which is why orangutans have become an iconic species representing the destruction of this cash crop. Orangutans need forests with old trees. They build their nests and are adapted to living their lives high up in the tress. They are the largest arboreal mammal.

Palm oil is not just bad for wildlife, it’s bad for the whole planet. To clear the land for plantations, the rainforest is burned

Clearing land for palm oil plantations involves burning rainforest, which is obviously bad for wildlife, but ultimately bad for us too. Burning trees and peatland releases carbon in the atmosphere, which contributes to climate change. Not only does the burning release large amounts of carbon, but the loss of forest and peat also prevents carbon in the atmosphere from being absorbed. Both forests and peat are major carbon sinks.

This video shows carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Check out the model at 1:02 to see the affect of trees and other plants on absorbing carbon in the spring and summer.

Why Boycotting Palm Oil Won’t Work

Now that we know how bad palm oil is, our gut reaction is to never buy this awful thing again (that was definitely mine)!

Before my trip to Borneo, I was at the International Conference in Conservation Biology in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and met experts from the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo who were at the conference to talk about palm oil. Before talking to them, I assumed that avoiding palm oil all together, or reducing your consumption, was the best thing that you could do, but they told me that was wrong. Here’s why:

1. Boycotting Palm Oil is Impossible for Most People

I tried to boycott palm oil for the longest time. For me, it was pretty easy because I don’t eat many processed foods. Or so I thought. But palm oil is in everything!

From cosmetics to ice cream to biodiesel and everything in between (I found out my skin care and makeup products contained palm oil). But I still thought I was doing good because these were the only palm oil products I thought I was using, and they are from a company that uses sustainable sourcing of ingredients.

What I didn’t realize is that palm oil could be called by so many other names! You can buy palm oil without even knowing it. Here’s a list of ingredients that come from palm oil:

Checking all of my products for these ingredient names would be extremely difficult and time-consuming for me – and I devote my whole career to nature and conservation. Even if everyday consumers had good intentions and want to avoid palm oil, this giant list makes it quite honestly, prohibitive. Palm oil really is in everything!

My mascara contains palmitic and steric acid, two ingredients that are sourced from palm oil.

2: The Alternative to Palm Oil Could Be Much Worse

Say we do all join together and stop buying palm oil. This crop is no longer profitable, palm oil plantations go out of business, and people stop planting it, which means no more clearcutting of forests. This sounds amazing, except it’s not going to happen.

The reason why people cultivate palm oil in the first place is to make money. People in Indonesia and Malaysia need to make money to support their families and options for doing so are limited. They won’t just suddenly start protecting the forests, they are going to move on to the next crop that is profitable.

Despite palm oil’s bad rap, it has some advantages over other crops. Palm oil produces at least three times as much yield as any other crop while using fewer pesticides and chemical fertilizers than other vegetable oils.

This statistic sums it up pretty well: “Palm oil makes up 35% of all vegetable oils, grown on just 10% of the land allocated to oil crops.”

More oil can be produced on less land. Image from the IUCN.

If palm oil is boycotted, global demand for an oil is not going to go down (remember that palm oil is in everything). Companies will need an alternative oil source, and this will result in MORE forest loss to plant these crops.

What Should You Do?

Buy Sustainable Palm Oil

There is an alternative – CSPO or Certified Sustainable Palm Oil. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil develops environmental and social criteria for companies to comply with to have CSPO. The World Wildlife Fund argues, that “when cultivated properly and planted in the right places, production of palm oil would not negatively impact the environment.”

The logo for certified sustainable palm oil.

CSPO palm oil has the following outcomes/requirements:

Fair working conditions

Protected land and rights for local people

No clearing of primary forest

Wildlife is protected on palm oil plantations

Reduced greenhouse gas emissions

Minimized industrial pollution

As of 2014, roughly 20% of all palm oil growers are certified, however, selling sustainable palm has been more challenging. Because palm oil is such a taboo ingredient due to its environmental destruction, companies are hesitant to draw attention to the fact that they use palm oil at all, even if it is sustainable. If the public is not actively looking for or demanding sustainable palm oil, companies are not going to pay the premium to get it, and this could increase demand for regular palm oil because realistically, most people will not boycott palm oil.

Boycotting palm oil removes incentives for companies to produce sustainable palm oil. Image from the IUCN.

How Do I Buy Sustainable Palm Oil?

Cheyenne Mountain Zoo Sustainable Palm Oil Shopping App

There are some great tools to help you determine if the companies that you shop from use CSPO. I’ve found that rarely is the RSPO logo on products. The first that I love is the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo Palm Oil app. I use this ALL theme. This app is great because when you are in the grocery store you can check products before you put them in your cart.

The Cheyenne Mountain Zoo’s Sustainable Palm Oil app. Just type in a company and it will give you a color:

The app ranks companies according to color with green being the best. If a company/product is not in the app at all, it means it is not CSPO.

WWF’s Palm Oil Buyer’s Scorecard

Another great resource is WWF’s Palm Oil Buyer’s Scorecard. Like Cheyenne Mountain Zoo’s app, you can search for your favorite brands and see how they rank.

I love this feature on WWF’s website. You can search for any company to see how they rank on palm oil sustainability.

And get detailed reports.

There’s even an option to do a social share – so you can easily tweet the report and pressure the company to be more sustainable.

If a company you love does not use RSPO, both the app and the website give you opportunities to pressure them to do so. The Cheyenne Mountain Zoo app has a sample letter that you can copy to send to companies and WWF’s website has a social share option so you can tweet their report and encourage them to switch to RSPO.

Arguments Against RSPO

It Doesn’t Go Far Enough

Some people are still not happy with RSPO and will not support it. They argue that there is no such thing as sustainable palm oil because even though wildlife and habitat is taken into account, forest is still destroyed, and it is still a monoculture plantation. Other concerns include that deforestation is only restricted to “high conservation value areas,” and palm oil that is still RSPO certified can be mixed with uncertified palm oil, yet the company can still get the certification.

Is There Evidence That it is Actually Better Than Uncertified Palm Oil?

Someone on my Twitter account doubted the actual impact of RSPO. He wrote:

is there any actual evidence "sustainable" palm oil does any good for biodiversity conservation? I haven't seen it. – https://t.co/0uFYU9OxhE

— Andy Boyce (@AndyJBoyce) October 5, 2019

And linked to this paper, which found no significant differences between RSPO and regular palm oil in relation to orangutan presence and fire (their measures of environmental sustainability. However, this study found that RSPO certification is associated with a significant decrease in deforestation, and this study found a decrease in fire incidence.

Also, although RSPO was started in 2003-2004, certifications for plantations actually didn’t start until 2009. Including deforestation and fires measures pre-2009 (pre-certification) is not a fair assessment of how well RSPO plantations perform.

Gemma Tillack wrote “Why ‘Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)’ palm oil is neither responsible nor sustainable,” but offers no solutions.

It’s Members Aren’t Sustainable

On my Instagram, someone commented “From what I’ve heard from places like Palm Oil Consumer Action is that the Chairs of the RSPO are companies like Nestle and Unilever, which use some of the most unsustainable palm out there. For me personally, my boycott is more of a stand against those companies that until they stop being so corrupt and become truly sustainable, I can’t buy anything RSPO certified when such high up members are not actually sustainable!

This is true that the companies that are members are not the most sustainable out there, however, I strongly believe in not letting progress be the enemy of perfection. In order to move forward with sustainability efforts, we need to include big companies to be effective. Otherwise, it won’t make that much of an impact for companies to actually want to buy it if it is too unattainable and the market will be so small. It’s already harder to sell sustainable palm oil.

It’s fine that you don’t want to support specific corporations because of your opinions on their company’s sustainability, however, I wouldn’t let that write of CSPO completely. And the only other options are boycotting palm oil, which is impossible for most people, which would then make CSPO less desirable, increasing the demand for regular palm oil, or alternative oils that use more land and do just as much environmental damage.

The RSPO is a non-profit organization that is made up of big companies, but it also includes conservation organizations that are compromising with companies to make them more sustainable. It may be less sustainable or slower progress that we like as conservationists, but it’s better than nothing. For more on the RSPO, check out this video:

I Support CSPO and Won’t Boycott Palm Oil

So, in an ideal world, we would save the forests and we wouldn’t need palm oil. But life doesn’t work that way. In my opinion, sustainable palm oil is the best answer to support people and wildlife.

Michelle Desilets’, Executive Director of the Orangutan Land Trust, sums this up well: …While no monoculture could ever be considered truly sustainable, I think we must consider that there is a spectrum of sustainability, and sustainable palm oil (for example that which is not grown as a result of forest clearance) is an infinitely better option than non-sustainable palm oil.

If you want to continue to improve your diet to make it more sustainable, check out “5 Easy Changes to Your Diet to Help the Planet.”

A big thank you to Chelsea Wellmer and Emmaline Repp-Maxwell of the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo for their help with great resources to write this blog post.

The post Why I No Longer Boycott Palm Oil appeared first on Dr. Stephanie Schuttler.

via Science Blogs

0 notes

Text

Famous Women in Diving: Dr. Andrea Marshall

Dr. Andrea Marshall, also known as Queen of Mantas, is best known for her dedication to protecting manta rays and other marine megafauna. She is the co-founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF), as well as one of the world’s leading authorities on manta rays. Here, we chat about how she became involved in conservation and the future of both MMF and conservation in general.

youtube

Let’s start at the beginning: when and where was your first dive, and how was it?

I was 12 years old when I became PADI certified and, even then, I was annoyed that I wasn’t allowed to qualify any earlier. I learned to dive in Monterey, California. It was a shore-entry dive and the water was freezing, but I still thought it was the most amazing place — diving under the kelp is like being in an underwater forest. I never regretted learning to dive in such an unforgiving place as it made me the strong, resilient diver I am today. Also, after diving in cold water my whole life, everywhere else feels tropical and I typically dive in a 1 mm everywhere I go.

Did you know right away that this was going to become a passion?

Put simply, yes! I’ve always been fascinated by the underwater world, even as a child. My mom tells me I used to talk about wanting to dive and study sharks since I was 5 and I’ve been passionate about marine life ever since.

What was the genesis for your research on and PhD in manta rays?

I was actually planning to study great white sharks for my PhD. But when I was in South Africa, I realized that I wanted to be in the water with my subjects and interact with them, which is impossible with great whites because you study them from the surface or the boat.

Subsequently, I had the opportunity to assess the conservation listing of manta rays for the IUCN Shark Specialist Group. Even though I loved mantas, I knew very little about them. As I tried to put together basic information on them, I realized there wasn’t much available, and the species was largely unstudied. This was so intriguing that I decided I would take on the challenge of researching them myself. Ultimately, I had to list manta rays as Data Deficient on the IUCN Red List, but this really inspired me to learn more about their basic biology and ecology, so we could properly protect them in the future.

Why mantas?

You can’t help but want to help these charismatic creatures. When you’re in the water with them, they’re very curious and will come and interact with you. When people ask me why I love them so much, the best way to answer would be to show you: you’d understand immediately if you saw them yourself in the ocean. They are truly one of our most iconic marine species.

Why did/do you focus on Mozambique?

I was involved in many exploratory diving expeditions in Mozambique when the country first opened up from its civil war. During this time, I realized what a special location it was for diving. There were so many animals, especially large, threatened ones like whale sharks, whales, sea turtles, dugong and manta rays. Mozambique offered the perfect opportunity to study species that no one really knew anything about, at least not in Africa. Knowing that your efforts can help contribute to the conservation and management of important marine species in an unstudied area gives real meaning to your work, so it was a great location to focus on. I have never regretted this decision and I still live and work along this coastline.

You’re the co-founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation. How did it come about?

I co-founded the Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF) with my good friend Dr. Simon J. Pierce. As conservation biologists, we were passionate about megafauna — particularly manta rays and whale sharks — and set up the charity to research these species and other threatened marine giants. It has grown and evolved over time, but it started because we both agreed we wanted to be in the field full-time. We knew that while safeguarding the animals was a priority, so was educating and uplifting local communities who, at the end of the day, need to be the ambassadors for change in their area.

Can you tell us a bit about the foundation’s work today? It looks like you’ve got programs all over the world.

MMF’s vision is a world in which marine life and humans thrive together. Ocean giants play a critical role in the keeping the ocean healthy. So, if we look after megafauna, we’re also protecting the wider ecosystem and other marine life.

Since we founded MMF, our scientists have used pioneering research to educate local and global communities and inspire lasting conservation solutions. Our head office is in Tofo Beach, Mozambique, but we also have projects in many parts of the world. We’ve spearheaded some and others are collaborations with other NGOs. To achieve our vision, we must inspire people far and wide to take action. We are so grateful for our global support and for our many partners. To do this work takes a village and we are always looking for additional support and collaborators.

Divers are often eager to help when it comes to conservation. Can you tell us about the citizen science program that allows them to contribute?

It’s actually really easy for citizen-scientists to make a genuine impact on current scientific research. In our line of work, it’s as simple as uploading photos from your dive. Whale sharks and manta rays both have unique markings, like a fingerprint. On each have a unique spot pattern on their undersides. Anyone who swims with one of these gentle giants can help researchers identify and track individual animals by taking a photo and submitting it to WhaleShark.org and Manta Matcher, the global databases for these animals, along with a few details from their dive.

These websites, and others like it, represent a new trend to collect citizen-fueled data and open-source sightings records for research groups around the world. In our case, we can count how many whale sharks and manta rays are seen in a region, find out where they travel and how long they live. All this information can be critical to protecting them.

Since you began your work, what progress have you seen?

When I started working with manta rays, there was almost no formal research on these animals and very little was understood about their lives. While there’s still a lot we don’t know, we have made tremendous progress. I am proud to have been a part of a lot of groundbreaking research that has allowed us to study mantas more effectively. These include the development of non-invasive technology to collect DNA samples or algorithms that we use in photo-recognition software to track populations. I was so proud that only eight years after I was forced to list manta rays as data deficient on the IUCN Red List, we were able to upgrade their status to vulnerable to extinction after amassing enough information to show they were a vulnerable species globally.

This meant that eventually, manta rays were listed on the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), two of the most important global-conservation treaties. Many countries have also begun to protect their manta populations and develop management plans. Don’t get me wrong, there’s much more to be done to safeguard mantas globally — but we are well on our way.

What are the biggest setbacks you’ve faced with MMF?

The last 15 years have been quite a rollercoaster ride. While helping pioneer manta research was a great opportunity, working with an understudied species comes with many challenges. Our projects are largely in the developing world, which can be frustrating when things don’t move ahead as quickly as we would like. Many large manta-ray populations we’ve found have been in very logistically challenging locations, making it difficult and sometimes dangerous to conduct fieldwork.

Funding can also be a major stumbling block, slowing down or impeding our progress. Even for a good cause, it’s harder than people imagine raising the funds we need to keep our projects running. Satellite tags, for example, can be very pricey, and they only last a few months before they fall off the animal.

Any final thoughts on the future of marine megafauna and ocean conservation in general?

My hope is that we can live in a world one day where both marine life and humans thrive together. I dream of our oceans being respected, restored and used responsibly, and I hope in some small way to help motivate this paradigm shift. I seek to inspire people to protect our ocean’s gentle giants before we lose them forever, as we have so many other species. I strive to protect and preserve keystone marine habitats from negative human impacts and safeguard our ocean heritage before it’s too late. We have the tools; we have the knowledge. If we can find the will, we can tackle this challenge head-on and win.

The post Famous Women in Diving: Dr. Andrea Marshall appeared first on Scuba Diver Life.

from Scuba Diver Life https://ift.tt/2Lbimxv

0 notes

Text

Bhargavi’s Quest for the Lost Bats of India

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

In 2016, Hipposideros hypophyllus slid to the bottom of a list that no species wants to be on – the ‘Critically Endangered’ section of IUCN’s Red List. The assessors stated that only 150 to 200 of these creatures remain, all of them confined to a single cave near the village of Hanumanahalli in Kolar, Karnataka.

Today, the bat commonly known as the Kolar Leaf-nosed bat is doing a lot better thanks to the efforts of the zoologists who made the assessment and convinced IUCN to raise the alarm. Bhargavi Srinivasulu is one of them (the other two are Rohit Chakravarty and Chelmala Srinivasulu).