#ayearinthecairngorms

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rinasluick

by Douglas Johnston

There are no ghosts at Rinasluick only deer grazing by the rubble from the granite walls.

Piping voices, echo in shrill delight filtered through archival detritus.

A small croft house, one story in height, slated and in good repair. Property of Colonel Farquharson of Invercauld.

Attested by the Revd's Middleton, Campbell & Smith. Of higher authority it seems than those who bide.

There were no deer at the rigs of Rinasluick when bairns ran the boundaries there.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seasons on the Mountain

by Kerry Dexter

In shadow up the mountain snow lies late in spring

In summer’s turn of season heather colours rise; daylight lingers then

With autumn’s breath a skein of geese unravels against greying sky

Silver brush of snowfall paints winter up the mountain Seasons turn again

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

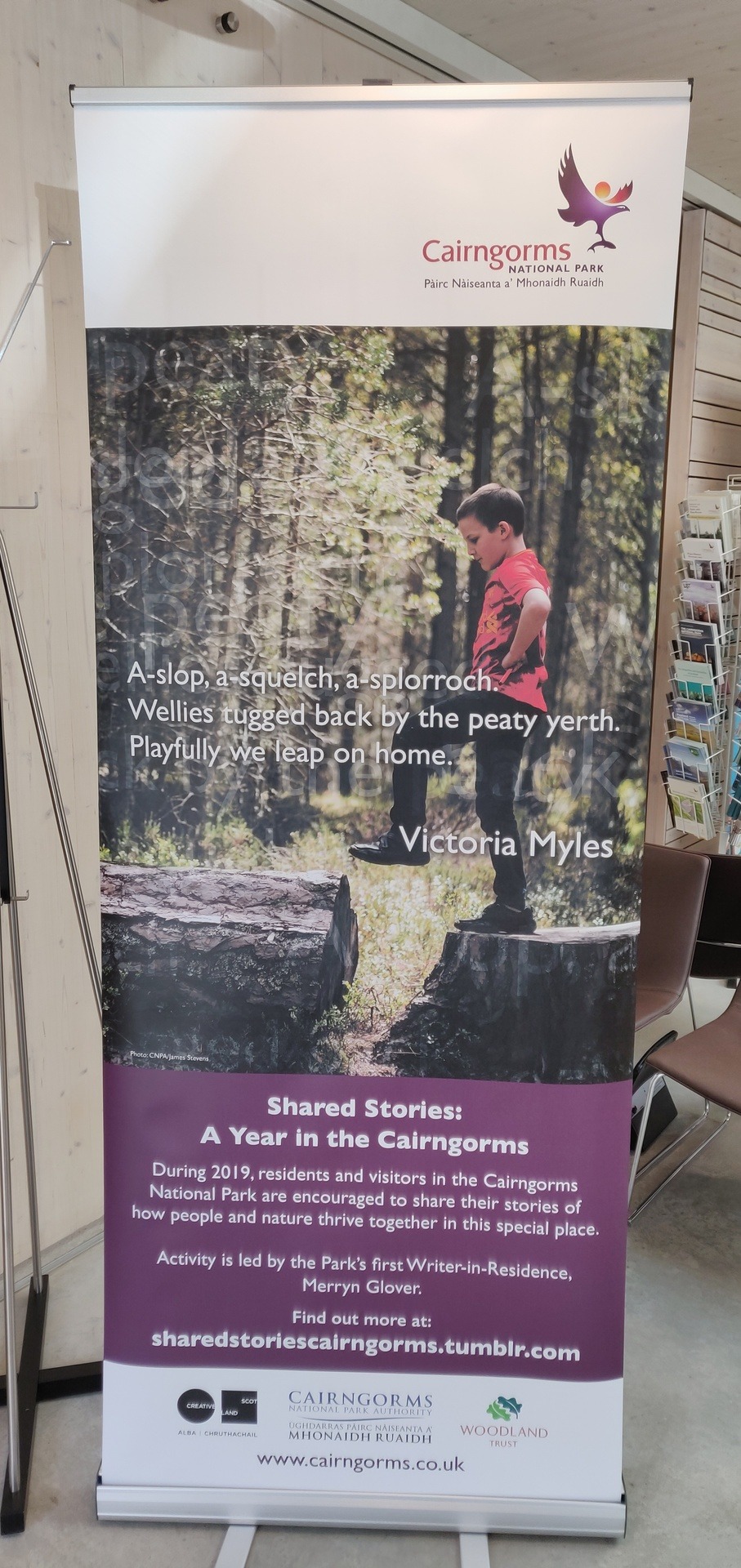

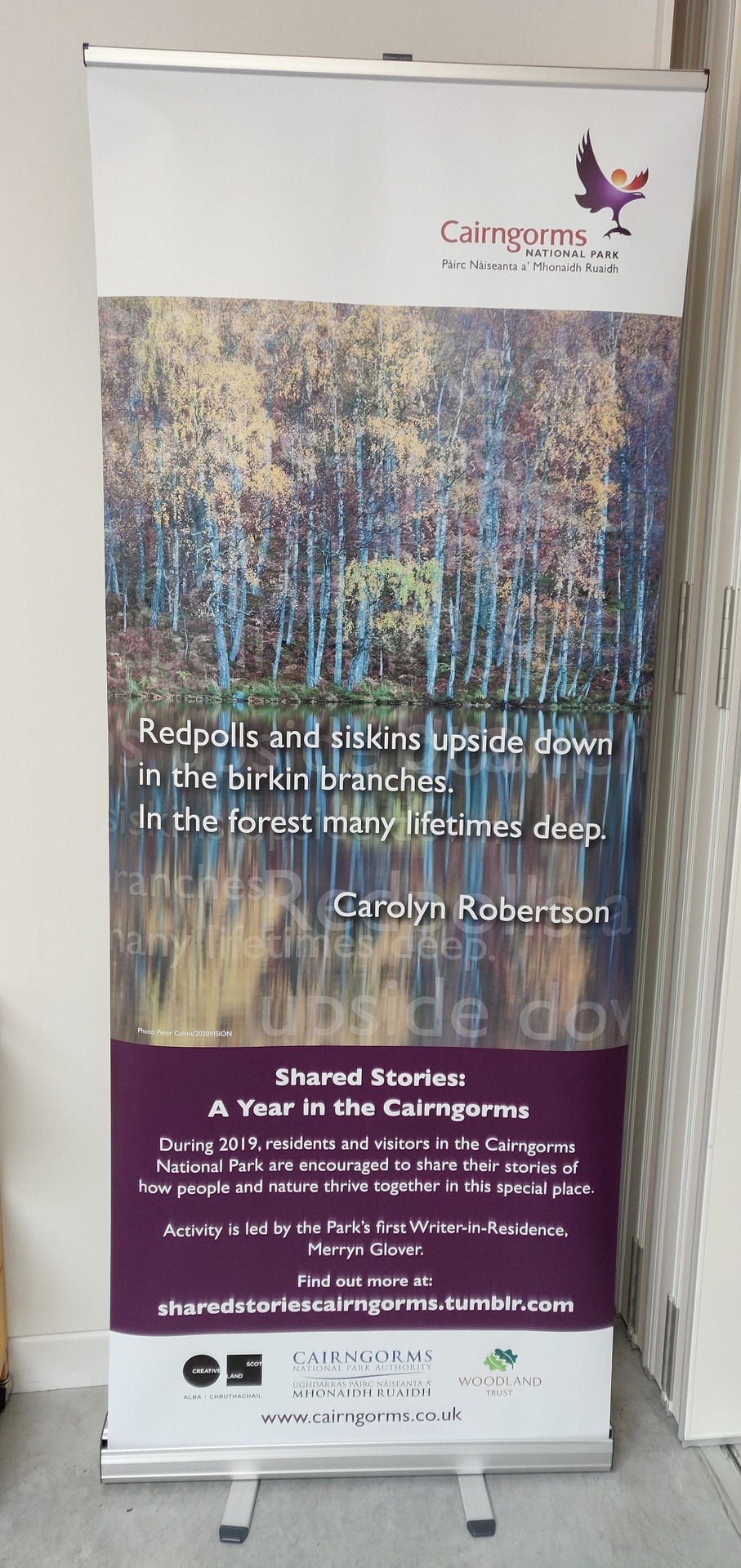

So delighted to see Cairngorms Lyrics appearing on banners across the Park. Two are by Victoria and Catriona, participants at our Aviemore workshops. One is at the Cairngorms National Park Authority’s office in Grantown, and the other at the Coffee Bothy in Laggan. The final one is by Carolyn Robertson, winner of the Park Staff Away Day Cairngorms Lyric competition!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

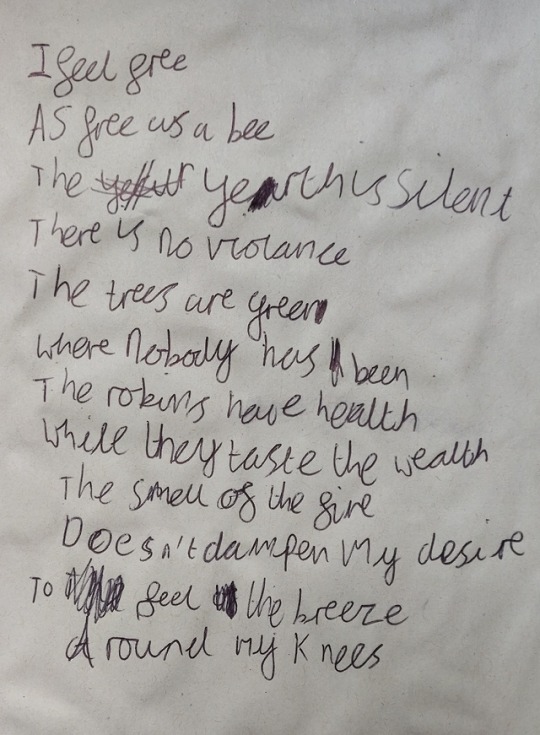

I feel free As free as a bee The yerth is silent There is no violence The trees are green Where nobody has been The robins have health While they taste the wealth The smell of the fire Doesn’t dampen my desire To feel the breeze Around my knees

Unknown young poet at Forest Fest, Highland Folk Museum

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

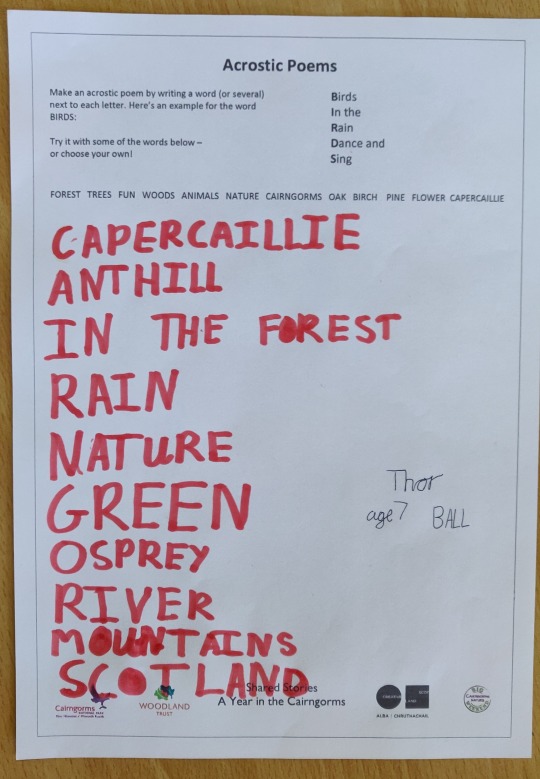

Capercaillie Acrostic

A poem from Thor Ball, age 7, who joined in the Caper and writing activities at the Cairngorms Nature Big Weekend in Carrbridge in May.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Into the Mountain - Garbh Choire Mor

by Neil Reid

A dished out hollow of snow, sharp, granite scree rising steeply before me, disappearing into a cold grey void.

A crack, a clack, a rattle. Impossible to identify a direction, but it's not the first stone that has fallen while I've stood here, nor will be the last. I am alone. I feel alone. Uneasily so.

When Nan Shepherd talks of walking out of the body and into the mountain it's a metaphor for heightened focus and perception; here, in the furthest reaches of the Garbh Coire Mor I feel I have walked out of the world and into the mountain - literally.

The Cairngorms have many faces and I have loved - and do love - them all: the lush river banks, the birdsong-filled quiet of the pinewoods, the austere beauty of the wind-scoured desert plateau. I enjoy auld mannie naps on the hillsides in summer sun, have stood for an hour in contented contemplation in a winter white-out. The Cairngorms have been mine since I was a child, and I theirs.

But here is different. There is no welcome here, no comfort. To journey into the Garbh Coire Mor is, as truly as is possible, to journey into the mountain; a pilgrimage not into its heart, but into an open sore, unhealed, raw edges actively plucking at the smooth waves of plateau which are thus revealed to be surface rather than substance. Here is the interior exposed and it cradles not the crystal water of other corries, but cold, hard ice.

For the 'eternal snows' of the Garbh Coire Mor are no snows at all; they are pressed by weight of winter after winter, when snow may lie to a depth of a hundred feet, hardened by a thousand failed thaws. As insubstantial as snow feels when it drifts out of the skies, one year when the longest-lived snowpatch melted we put a time capsule in a plastic box in the bottom of the hollow it has created for itself high up at the foot of the cliffs. The following year, when the unthinkable happened again, the time capsule was recovered - crushed flat by the weight of just one winter's snows.

The pilgrimage here to see those snows of high summer, to stand truly inside the mountain, is a challenge in excess of reaching the tops of most mountains - the bowl of the inner corrie is over 1000 metres above sea level. Leaving the steep-sided confines of Glen Dee, the mountains press in closer and steeper as you climb, channelled towards your goal, the now pathless way becoming ever rougher. Temptation beckons in the spacious Garbh Choire Dhaidh, where the Dee Waterfall feeds a vein of life nourishing pools and lush grasses. But you resist, and persevere up bedrock and boulder into the bare bowl of Garbh Choire Mor. On and on yet, for the boulders climb to an inner recess, a corrie within a corrie, ringed by fractured cliffs of grey and raw pink.

Labour up this slope and you're aware of another interior - beneath your feet. The voids between the massive grey boulders fall to unknown depths. It's common on such slopes to hear water running beneath, but here to the familiar rush is added echo, the sound of vast, subterranean cisterns. Can such things be? Climbing alone, upwards into this innermost maw of unfinished geology, you lose any assurance that it can't be and balance up, boulder to boulder, as though caverns lie below.

And you breast the lip of this innermost corrie into a dip. If the winter snows have gone from this cauldron then the rocks are covered in black moss. It has the feeling of a trap waiting to be sprung by an unwary footstep, so you do not linger but head on up the slopes of boulder, scree and grit, slipping as the ground steepens and moves beneath your feet. These are not rocks rounded by the millennia: they are sharp, freshly broken from the mountain, raw pink still, and gritty, loosely bound in a matrix of mossy sand and gravel. Feet slide, the slope feels dangerous, unstable.

When you reach your goal, that last fragment of snow, you realise it to be a chimera. That the snow has lasted through another summer is, obscurely, important to you, but the substance of it holds no magic; it's just dirty ice, dripping into ground that looks freshly bulldozed, stones on the surface a reminder that where you are, under the cliffs, is not safe. Up this close, foreshortening appears to rob the cliffs of their height and makes of them great, jagged teeth, but you are yet more than 500 feet below the surface of the plateau.

I have crawled between these teeth to escape upward, up through grit and scree, thick, dark moss that hides holds for hands and feet. I have carried on up the granulating scar of Pinnacles Gully, fingers pushing, twisting, prising through moss and wet, red granite grit, seeking solidity in the shifting, unstable gully bed, to thrutch and scrape upward between granite jaws, watching and listening as another boulder slurps out of its mossy socket and cracks and bangs its way downward, bouncing from wall to wall, a smell of brimstone tracking its passage.

Release comes suddenly. A last chockstone, a widening of rubble and tenuous vegetation, then out from damp shadow to a sun-baked plateau stretching out in long, lazy waves of landscape. It's a liberation that lifts the heart, to be back on the surface after a journey inside the mountain.

Can I say I love even this most remote corner of the Cairngorms? It tests my devotion, this seeping wound gnawing at the edges of the plateau, in its near lifelessness, its damp chill, its raw unfinishedness. But it draws me. If I cannot yet love it I am fascinated by it and, even as my stride stretches out across the open plateau, I am plotting a return.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blue Bird Day Climb

By Mike Wilkes

A burn meanders across the valley, swinging to and fro within the cradle of the glens parabolic walls. Buttery, yellow sunshine warms the bog and heather, raising drifts of Large Heath butterflies from the banks. The track steepens, the effort bringing on an eye-stinging, itchy-wool hotness. Exertion narrows focus to only the next foot fall. Boggy ground, the occasional purple butterwort, then coarse, dry heather, then Wooly Fringe Moss, now Creeping Azalea and rock. Now only shards of sandpaper-rough quarzite as the gradient eases slightly. The air at this height is rinsed by a chill breeze, as if from space, and it is menthol to the lungs. Then crack, the crest. Like plunging into a blue-black ocean that hangs above a sandy, mauve seabed. The ground falls away to the view of Munros - Cairn Toul, Braeriach, Ben Macdui and sky.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Birch

by Katy Turton

The nude, winter birch branches drip Like the freshly washed hair Of a young woman.

As the sun warms The land, green unfurls A veil to cover the naked brown.

Dressed and adorned With leaves of chrysoberyl, peridot and tourmaline, The tree shivers with pleasure in the summer Heat.

But autumn’s chimes Turn gems to yellow scraps Of paper drifting Silent, on the wind.

1 note

·

View note

Text

What do you hear?

by Amy-Louise Hutchinson

Tweeting birds high up in the Scots pines, Tapping quickly, Shooting past to catch that beastie. Wood Ants upon the floor scuttling along for their food to give their Queen, Crackling fire, Boiling water, Time for a nice hot cuppa, Sitting here listening to what I can hear every other Friday under the watchful eye of the awesome rangers, Looking back at the footage from the camera traps, Young deer, A fox cub and a badger appear on the screen. Stop and listen what can you hear.

0 notes

Photo

An acrostic poem about capercaillie by a young writer at the Cairngorms Nature Big Weekend.

0 notes

Text

Common Ground

- David M. Watson

Place is timeless—everything else comes and goes. I first found myself in this place, the Scottish highlands, ten years ago. Invited to share my research at a conference in Aberdeen, I made the most of the opportunity and travelled there with my family, staying for a few weeks at a farmhouse on the edge of the Cairngorms National Park. Although we’d never been to Scotland before, so many things were strangely familiar. The honeyed aroma of a peat fire, the scent of heather as we walked up the hill flushing birds new to our eyes but recognized like old friends. The roll of the hills, the lean of the houses, the faces of people we encountered. They looked right; just so. As a Watson, my family roots run deep here. Seven generations of my clan in Australia follow hundreds of generations in this land. The memories are not mine but they resonate as clearly as a curlew at dusk. This was home.

Walking through the heather one morning, I found myself on a sheep trail, my feet gravitating towards the same path as countless before. The path meandered past a dense copse of pines, then turned sharply towards a rivulet, tea-coloured waters sliding across the land. As I turned, my eye was drawn to movement. Looking closely, I saw wire, a cage. Approaching to look more closely, it took me a moment to understand what I was looking at. A raven was caught, flapping wildly at the corners of its jail. It was a crude trap, an opening at the top leading in via a narrowing cone, a dead hare hung as a lure. Integrating this incongruous scene with my experience working on farms and studying birds, I began to understand. Where I live in Australia, many farmers despise crows. Checking on their stock after a cold night to find lambs being picked over by these glossy undertakers, blame comes easy.

Ravens and I have history. Years earlier, I encountered them—this same species, largest of all the songbirds—in the cloud forests of southern Mexico. For my doctoral research, I studied the distribution of birds in these ancient sky islands, trying to fathom how wildlife persists in disrupted landscapes. I presented my interim findings at a conference, right before heading south to visit more forests to add more dots to my graphs, to weave more characters into my story. I met somebody there—we connected straight away. The common ground between us made communicating easy. Days after we met, I was back in the forest. A raven called, off in the distance, its rattling voice filtering though the pines as I was writing a letter to my love. Was this her? Was this my raven?

And here, now, this caged bird. Fiddling with the door, it sprang open. As the bird regarded me, I noted the pink corners to its mouth, the sparse feathers on its throat. This was a young animal, fooled more easily. Seeing the unfettered sky behind me, it flew off, wingbeats pushing away the bracken fronds concealing the wire cage. I watched it shrink into the grey sky and pondered the significance of what had just happened. The intelligence of these birds is legendary. They remember faces, they learn from direct experience and they share knowledge with their kin. I saved a life that day but also informed an extended clan. About small-minded people looking to blame others, about individual actions railing against humanity’s failings. About connections between people and other animals, connections stretching back to a time where the common ground between us made communicating easy.

0 notes

Text

Loch Laggan

by Catherine Faulkner

At beckoning dusk I went Through the bog-swell of rich mud That pulled me to the land. And there, beyond, were Waters smooth as legend Shivered silver by winter, A ghost-plated daguerreotype Etched onto a vanishing place. And somewhere we existed, there, On the horizon line, In the fugitive light, In that symmetry of loss Between two worlds. But our mirror-spell was broken By the arrival of geese on stark wings And mercury-quick you slipped from me And I sank away from the silvered world. Later another traveller might remark upon The plated precision of beauty, Such quiet water, Such stillness.

0 notes

Text

97 mph on the tops

Lying in my tent Listening hard Booming in the background Across the Lairig A symphony of noise Crashing in to the cliffs Waiting for the next crackle of tent fabric Moving and swirling The sound comes down Smashing my tent My toes and feet bearing the brunt The tent and poles squashed flat against the ground and me The noise simmers down The tent springs back The gust has gone Momentarily calm returns Noise building on the other side of the hill Heralding the impending return It’s going to be a long night.

I wrote this after a particularly windy night spent in my tent in the Lairig Ghru. The recorded wind speed on the tops was 97mph. I was delighted to be out of my normal routine and having a mini adventure, but also delighted to be hiding in the shelter of the Lairig Ghru rather than on my planned camp spot further up the hills.

A poem by Nancy Chambers

https://www.nancychambersauthor.co.uk/

0 notes

Text

The Spey

Uisge Spè, a river of Hawthorn

Majestic and powerful

From mountain to sea

The Spey.

by designjaybee

0 notes

Text

Identification

by Julia Duncan, Ranger

“A red-throated diver!” he exclaims. I mumble and peer through my binoculars. I see a dark, vaguely bird-shaped blob.

This is trickier than I thought.

“Oh and listen – a sedge warbler. Delightful”.

Is that what that is? In my head, I skip through tracks on my Bird Identification CD. It’s not that they all sound the same, exactly – just, you know… Similar.

“Could you go and pop this way marker in by the Bird’s Nest Orchid?”

Oh. Um. Yes. Orchid. That’s the flowery-shaped one.

No?

Ok.

“And for the records – make a note of all the conifer species in the area?”

Conifers. I leaf hurriedly through my tree book. Excuse the pun. All of them? Right. Yes.

“While you’re there it wouldn’t hurt to note a few sedges too – you’ll manage that”.

Sedges. Sedges. We did mention them on that uni field trip, but I’d had a couple of pints the night before and maybe shut my eyes for a second out in the field.

“Wait!” he shouts, putting his binoculars up to his face. “What is this…”

I might as well not bother, but lift my bins too.

“I’m struggling,” he says.

It can’t be…. I know this. I actually know this. “It’s a robin!” Ha! A robin. Good old Robin Red-breast.

It wasn’t a robin.

0 notes

Text

In High Trees

by Jen Cooper

Every time, you say, these high trees exceed your expectations. Your eye drawn up, and up again, to crescent goldcrest nests. We wait in the quiet moments, feel the air get light before their intermittent bursting out from cover to dart between trees in threes and fours – their sheer lightness – landing on pines whose bark shards dwarf kinglet bird, so plain except that yellow orange crest.

2 notes

·

View notes