#astarabad

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Baloch women spraying antiauthoritarian protest slogans in the city Gorgan/Astarabad, capital city of the minorities majority Golestan province, current northeast Iran.

Balochistan's southwestern part is currently held as Iran's southeast, where the protests sparked by the murder of Kurdish woman Jîna/Mahsa Amini by the regime's immoral "morality police" in Tehran still continue in mostly huge Friday protests consecutively every week for now soon a year, in spite of repression including huge actual massacre."

#baloch#balochistan#161#1312#gorgan#astarabad#iranian#ancient iran#iran#iran iraq war#kurdish#mahsa amini#anarchofeminism#jîna#class war#classwar#tehran#antifascist#antifaschistische aktion#antifascismo#antifaschismus#antiauthoritarian#antinazi#antinationalist#humanrights#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

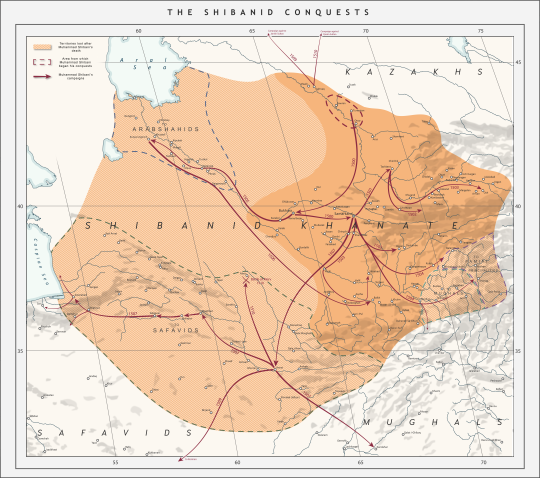

The Shibanid (Shaybanid) Conquests, 1500-1510.

by u/Swordrist

This is my attempt at covering an underapreciated area of history which gets next-to no coverage on the internet. Here's some historical context for those uneducated about the region's history:

Grandson of the former Uzbek Khan, Abulkhayr, Muhammad Shibani (or Shaybani) was a member of the clan labeled in modern historiography as the Abulkhayrids, who were one of the numerous tribes which were descended from Chingis Khan through Jochi's son, Shiban, hence the label 'Shibanid' which is used not only in relation to the Abulkhayrids who ruled over Bukhara but also for the Arabshahids, bitter rivals of the Abulkhayrids who would rule Khwaresm after Muhammad Shibani's death and for the ruling Shibanid dynasty of the Sibir Khanate.

After his grandfather's death in 1468, Shibani's father, Shah Budaq failed to maintain Abulkhayr's vast polity in the Dasht i-Qipchak, as the tribes elected instead the Arabshahid Yadigar Khan. Shah Budaq was killed by the Khan of Sibir and Shibani was forced to flee south to the Syr Darya region when the Kazakhs returned and proclaimed their leader, Janibek, Khan. Shibani became a mercenary, serving both the Timurid and their Moghul enemies in their wars over the eastern peripheries of Transoxiana. After the crushing defeat of the Timurid Sultan Ahmed Mirza, Shibani succeeded in attracting a significant following of Uzbeks which formed the powerbase from he launched his conquests.

Emerging from Sighnaq in 1499, Muhammad Shibani captured Bukhara and Samarkand in 1500. In the same year he defeated an attempt by Babur (founder of the Mughal Empire) to take Samarkand. Over the course of the next six years, Shibani and the Uzbek Sultans conquered Tashkent, Ferghana, Khwarezm and the mountainous Pamir and Badakhshan areas. In 1506, he crossed the Amu-Darya and captured Balkh. The Timurid Sultan of Herat, Husayn Bayqara moved against him however died en-route and his two squabbling sons were defeated and killed. The following year he crossed the Amu-Darya again, this time vanquishing the Timurids of Herat and Jam and subjugating the entirety of Khorasan east of Astarabad. In 1508, he raided as far south as Kerman and Kandahar, however he moved back North and launched two campaigns against the Kazakhs, but the third one launched in 1510 ended in his defeat and retreat to Samarkand at the hands of Qasim Sultan.

The Abulkhayrid conquests heralded a mass migration of over 300 000 Uzbeks to the settled regions of Central Asia from the Dasht i-Qipchak. They heralded the return of Chingissid political tradition and structures and the end of the Persianate Timurid polities which had dominated the region for the last century. It forever after changed the demographic of the region. His reign was also the last time Transoxiana was closely linked with Khorasan, as following the shiite Safavid conquests the divide between the two regions would grow into a permanent one.

In 1510, Shibani faced his end when he moved to face Ismail Safavid, who was making moves on Khorasan. Lacking the support of the Abulkhayrid Sultans, who blamed him for their defeat against the Kazakhs earlier that year, he faced Ismail anyway, where he was defeated, killed and turned into a drinking cup.

Shibani's death caused a complete reversal of the Abulkhayrid fortunes. Khorasan and the rest of his empire fell under Safavid dominion. However in Khwaresm, Sultan Budaq's old rivals the Arabshahids expelled the qizilbash and founded their own Khanate, based first in Urgench and then Khiva. In Transoxiana, Babur lost the support of the populace when he announced his conversion to Shiism and his loyalty to Shah Ismail, which allowed the Abulkhayrids to rally behind Shibani's nephew, Ubaydullah Khan and expel the Qizilbash. Nonetheless, the Abulkhayrids would never again hold as much power as they briefly did when led by Muhammad Shibani Khan.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Persian culture, its legacy, and its continued production, played a vital part in the overarching Iranian sense of self, to the point where Safavid Iran may be called an incarnation of the age-old Iranian “empire of the mind,” in Michael Axworthy’s apt phrase. As noted, Iran was multilingual; as they do today, the country’s inhabitants spoke a number of different languages, from Persian and Kurdish to Turkish and Arabic. While Safavid shahs usually conversed in Azeri Turkish, Persian was the mother tongue of the country’s urban elite and the core political and administrative language of the entire realm. Persian was also the language of high culture, above all of poetry, the supreme expression of the Persian language, which linked the past, including the pre-Islamic past, to the present and served as a shared cultural repertoire, not just for the elite but for the common people, at least in urban areas.

The other (inherited) term employed in Safavid chronicles, mamalik-i mahrusah, the “protected realm,” adds a religious dimension to the notion of territory. In what was to be their greatest political accomplishment, the Safavids connected faith with land by imposing Twelver Shi`ism on their realm. Under their auspices, territory and religion came to overlap in ways that have characterized the country ever since. A minority faith within Islam, Shi`ism imbued the Iranian state with a sense of unity by way of particularism. Even if this unity remained far from complete, the Safavids used Shi`ism as an effective propaganda tool to set themselves apart from their Sunni neighbors, the Ottoman, the Mughal, and the Uzbek states. They cultivated Twelver Shi`ism as a mark of distinction in a variety of ways, ranging from the ritual cursing of the first three caliphs to the propagation of festivals commemorating the faith’s foundational events.

They patronized Iran’s Shi`i shrines, including the mausoleum of the dynasty’s founder, Shaykh Safi, in Ardabil, and at times when they controlled Iraq, took special care of the `atabat, the tombs of the imams. After Iraq was lost to the Ottomans in 1638, the Safavids spent large amounts of money on the restoration and embellishment of Iran’s own shrine cities, Mashhad and Qum, which evolved into devotional centers of pilgrimage in competition with the Iraqi `atabat. A shift in the language used for religious writing reflects a growing congruence between territory and religion as well. In contemporary Protestant Europe, vernacular languages began to supplant Church Latin. Late Safavid religious scholars similarly began to make their writings more accessible to ordinary literate people by composing their treatises in Persian rather than in Arabic. In the process, the status of Persian as a unifying idiom increased, further enhancing the role of the ulama as spokesmen for a nascent national-religious identity.

Twelver Shi`ism was well suited to weld the nation and the dynasty together. Its symbols and doctrines—and especially its focus on authority as a hierarchical series of emanations—were easily adapted to the traditional notion of the Iranian ruler as the divinely appointed protector of people, territory, and faith. God was the lord of the universe and the Imam his vicegerent; in the latter’s absence, the shah was God’s “shadow on earth,” charged with the task of upholding the cosmic order until his return. The Safavids’ claim of descent from `Ali, the first Imam, and their deference to the Hidden Imam—whose servant the shah called himself—combined with the ancient Iranian divine right of kingship to produce a strong basis for dynastic legitimacy.

All this made the shah a crucial unifying force. He was the sole link between the divine and the terrestrial spheres, the only force to cut across societal ranks and divisions, and thus the foremost centripetal element in the realm. Initially, the Safavid ruler was revered as the murshid-i kamil, the divinely guided perfect Sufi shaykh. The terrible defeat the Safavids suffered against the Ottomans at Chaldiran in 1514 damaged their divine charisma and cost them in tribal allegiance. Yet Isma`il’s successor, Shah Tahmasb (r. 1524–76) continued to be venerated as a god-like figure to the point where people would reverentially kiss the doors of his palace and consider any water the shah had touched a cure against fever. Shah `Abbas I similarly was credited with supernatural powers. One chronicler recounts how in 1598–9 the construction of a fortress near Astarabad (modern Gurgan) was held up by persistent rains until the shah successfully begged the heavens for a dry spell.

For the remainder of the dynasty’s lifespan the shah retained supreme power and legitimacy as an Iranian king, demanding his subjects’ continuing loyalty. Safavid chroniclers proclaimed unqualified obedience to him a self-evident obligation. What Iran’s rulers meanwhile lost in messianic luster they regained in part through the shah-seven, “love for the shah” phenomenon—whereby his subjects declared their loyalty to him and contributed funds or labor to public works undertaken by the crown. Shah `Abbas, in particular, would cultivate the shah-seven bond as an alternative to tribal loyalty. .... Iran’s rulers, in sum, enjoyed tremendous legitimacy—exceeding even that of their Ottoman and Mughal counterparts—which perhaps explains why no Safavid ruler was ever deposed and why only one, Shah Isma`il II, r. 1576–7, may have been assassinated. Over time, cracks appeared in this edifice: At least one treatise from the early eighteenth century raises doubts about the divine nature of the shah, suggesting a crisis in royal legitimacy that was likely related to a faltering martial performance and the insularity of the shah since the days of Sulayman. Meanwhile, de facto power shifted from the monarch to the grand vizier, to the point where, after Shah `Abbas I, this official often acted as the ruler’s stand-in. Yet, unlike the Ottoman vizier, the Safavid chief minister remained beholden to the shah as the ultimate source of power and thus never operated as a quasi monarch.

The shah enjoyed unfettered arbitrary power. Yet he was also supposed to protect his subjects and he had a mandate to treat them equitably. Royal justice, pivotal to the age-old theory of Iranian statecraft, figured prominently in Safavid ideology. Justice was enshrined in a cultural heritage that invoked ancient rulers, real and mythical ones, as exemplars. It was also an integral part of manuals of good governance and reiterated in every single royal decree (farman). Conceived as a cycle, justice mandated royal kindness and benevolence with the aim of fostering the welfare of the people and thus securing the dynasty’s longevity. Royal justice found concrete expression in tax rebates following the enthronement of a new shah or at times of economic hardship, as well as in the habit of distributing money to the poor as part of coronation celebrations, during the New Year’s ceremony, and whenever the shah fell ill.

Royal justice mandated accessibility as well, giving those who had suffered injustice a chance to seek recourse with the ruler himself. Its purpose was twofold: It showed royal concern for commoners and it allowed rulers to gather first-hand, unmediated intelligence. Several shahs are known to have mingled with the people in an informal public setting. Known for his “melancholy disposition,” Shah Tahmasb in the last years of this reign lived within the confines of his palace, out of reach for the people, leaving his subjects without a symbol of justice and at the mercy of greedy subordinate officers, including the judiciary powers. Shah Isma`il II, otherwise known for the bloody havoc he wreaked on the elite, would go around Qazvin to apprize himself of the state of his realm. Shah `Abbas’s famously casual governing style included his habit of strolling through the streets of Isfahan during festivals, accompanied by his female retinue, joking with people of various walks of life, and visiting their homes.

It was also customary for petitioners to try to attract the shah’s attention when he went out riding by grabbing the bridle of his horse and handing him petitions. Popular discontent often manifested itself in bread riots, but more formal outlets existed as well. In the period of Shah `Abbas I, the vizier of Isfahan would collect petitions from people. Under the same ruler a grievance council existed. `Abbas II instituted a semi-weekly tribunal (majlis) for the same purpose. Rendering justice also was among the explicit responsibilities of various offices. A good example is the city prefect (kalantar). The shah appointed him but in accordance with the wishes of the populace—and for good reason, for he acted as a middleman. It was his task to defend people against the vexations of other local officials as well as to protect them from unscrupulous vendors.

Naturally, none of this was quick or easy; serious obstacles, from poor communications to obstructionist bureaucrats, made it difficult for ordinary people, especially in the outlying areas, to stand up to fiscal oppression by local officials, let alone make their case in Isfahan. Yet a community with enough resolve was not without legal recourse. Numerous examples underscore the power of the “popular vote” and show even the late Safavid monarch in his role as a brake on extortion and abuse by intermediate forces. In 1662 the viziers of Gaskar, Kashan, Daylaman, and Shirvan all lost their jobs following complaints by the local population, ra`iyat; in 1680, popular protest about the tyrannical rule of Khusraw Khan, the governor of Kurdistan, caused this official to be recalled to Isfahan and executed; and in 1695 the kalantar of Rasht in Gilan was dismissed after his subjects voiced their displeasure with his conduct. Several farmans from the 1650s and 1660s document successful village resistance in Armenia against the usurpation of their land by provincial officials.”

- Rudi Matthee, Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. London: I. B. Tauris, 2012. pp. 14-18.

#دودمان صفوی#safavid iran#safavid#history of iran#iranian history#mamalik-i mahrusah#twelver shi`ism#shah#shah-seven#farman#ardabil#`atabat#qum#mashhad#persian#farsi#shadow of god on earth#divine right of kings#astarabad#majlis#royal justice#early modern state#early modern society#ideologies of empire#methods of rule#rudi matthee#safavid persia#academic quote

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On May 16th 1805 Sir Alexander Burnes, Scottish explorer and public official, was born in Montrose.

A noted explorer of Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan, and southern Russia, he was author of Map of Central Asia and Travels into Bokhara, Burnes was a descendant of our bard Rabbie Burns.

As an army officer in India, he studied Asian languages, and in 1832 he left Lahore in Afghan dress and travelled by way of Peshawar and Kabul across the Hindu Kush to Balkh; and from there, by Bukhara, Astarabad, and Tehran, to Bushire.

In 1839 he was appointed political resident at Kabul, Burnes, he was involved in a lot of shenanigans, and has been described as a Victorian James Bond, as we all know from modern day events, Afghanistan is a dangerous place, it was no different back then, on 2nd November 1841, a mob attacked Burnes’s house and, as he attempted to flee, he was cut to pieces, the second pic is an illustration of this.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The best camp place on Iran

The best camp place on Iran

Introduction If you are looking for a camping place in Iran, there are many places for you. But, we will recommend to choose the best camp place in Iran. The best camp place in Iran is the southern port of Iran. There are many beautiful places like Astarabad and Astara which is located near the Caspian Sea, you can enjoy your staying there and feel safe because it’s very quiet and calm area with…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Great Mongol Empire Timurid Shahrukh AR Silver Tanka 831AH Astarabad Mint. 5.05g https://ebay.us/v5rHey https://www.instagram.com/p/ByDgKfJpzvW/?igshid=1hb4uqg4bkp1h

0 notes

Photo

The 1000 years old, 236 ft Tower of Gonbad-e-Qabus in Golestan, Iran.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

“To achieve a modicum of control around the country, the Safavid state resorted to various strategies beyond punitive expeditions to regions in revolt. One way of reducing subaltern power was to try and restrict the spread of firearms, a relatively new form of weaponry that was initially limited to the state. Like many contemporary states, the Safavids sought to halt their spread among the wider population. The people of Lar—a major manufacturing center of firearms—were prohibited from carrying guns at the time of Shah `Abbas I. In the late seventeenth century such orders were still in place in remote areas. Bénigne Vachet, traveling in western Iran in 1690, claimed that in all of Iran mountaineers were forbidden from carrying any other arms than batons. Such bans naturally had little effect. Ambrosio Bembo, traveling in the Kurdish Ottoman–Safavid borderlands in the 1670s, observed how not even peasants in those regions were without “an arquebus or sword or bows and arrows.”

Much more effective was the forcible resettlement of populations, a long-standing practice pioneered by the ancient Assyrians. Resettling a recalcitrant border tribe into the interior was typically designed to break up vested tribal power. Shah `Abbas thus deported the Qazaqlu from Qarabagh to Fars. Deportation was often a precautionary measure. We hear of tribes being moved away from the front lines in the face of imminent war, for fear that they might side with the enemy.

Depopulation was also a byproduct of the scorched-earth policy that the Safavids often engaged in. An example is Shah `Abbas’s removal of the entire Armenian population from the Aras River region in the face of Ottoman aggression in 1603–4. Most often the aim was the protection of borderlands. The northern frontiers, perennially exposed to raids by Uzbek, Turkmen, and Lezghi tribesmen, were a favored destination for deportations of this kind. Dividing the Qajar tribe into three groups, Shah `Abbas resettled many of its members to the north, making them guard Ganja in the Caucasus and Astarabad and Marv on the Central Asian frontier.

The same ruler sought to strengthen central control by relocating a large number of Qizilbash tribal folk to Georgia. `Abbas encouraged the Turkmen Göklen to settle around Astarabad so as to protect the Khurasan border against raids by the Yomut, a rival Turkmen tribe.

Frequent raids by Lezghi marauders as well as Russian pressure on Daghistan made Shah `Abbas II move large numbers of Turks to Georgia, prompting an uprising against Safavid rule in 1659.

Kurds, renowned for their martial qualities, were often deployed for defensive purposes. Many thus ended up in Khurasan. A number of Kurds were also sent to Kitch and Makran in Baluchistan to help defend those remote marches. Chardin gave the following numbers for troops defending the borders in the mid-seventeenth century: 6,000 for Kirmanshah; 50,000 each in Armenia and Georgia; and 8,000 each in Khurasan and Qandahar.

State authority was not founded on military means alone. In fact, force was not the principal form of control, even if the threat of armed intervention was always the ultimate deterrent. Isfahan used “soft” power much more widely and, arguably, more effectively to keep the provinces in check. This came in different forms, ranging from the appointment of shadow officials to alliance building by way of marriage and various tributary arrangements. In all of this, the ultimate purpose was to secure loyalty, a commodity that was structurally in short supply. As Patricia Crone puts it, the premodern state did not inspire any loyalty. Yet managing a state was predicated on at least some form of (temporary) loyalty. To achieve this was to engage in perpetual negotiation and bargaining.

Negotiation typically involved some form of mediation by brokers or middlemen, vakils. The vakil, a person who could deal with both parties and a central figure in Iranian politics, operated on different levels. Provincial governors were well advised not to take up their position in provincial outposts without good representation in Isfahan, since leaving the court would unleash a wave of intrigue against them. They would often stay in the capital themselves, dispatching a relative in their stead; and if they took up their post, they would leave a vakil to represent their interest. Until they were recalled to Isfahan to account for their behavior, these officials usually remained at a safe distance from the capital, where agents and family members interceded on their behalf. Some hardly ever showed up in the region to which they had been appointed, although few would go to such extremes as the muhrdar, keeper of the royal seals, who waited twenty years before visiting Qum, the province assigned to him by Shah Tahmasb.

One time-honored way of keeping individual power in check was to appoint mutually controlling officers. This began at the central court, where the nazir (steward of the royal household) checked on the grand vizier and in turn was controlled by a number of other officials. The vizier of a khassah province typically had a nazir and a vaqa’i`-nivis (registrar) as assistants, who acted as shadow officials charged with the task of monitoring him. According to Chardin, in Mazandaran the vizier and his assistant were expected to report on each other. The fiscally important Caspian provinces, moreover, were headed by a vazir-i kull, whose task it was to control the vizier in financial and juridical matters. In Bandar `Abbas, the shahbandar, harbor master, and the local khan operated in similar fashion. Chardin attributed the relative lack of rebellion in Safavid Iran to the ubiquity of such institutionalized mutual control.

Alliance building was the most commonly used control strategy. It came in various forms. One was to keep the sons of local rulers as hostages in the capital, conditioning them as loyal Safavid subjects. This age-old practice was especially common with regard to outlying regions such as Georgia, Daghistan, and `Arabistan. Shah `Abbas kept Constantin Mirza, son of the Georgian King Alexander, in Isfahan. Alqas Mirza, a Lezghi prince, was sent at a young age as a hostage to Isfahan, renamed Safi Quli Khan, reared in the harem, and in 1666 appointed governor of Yerevan.

A more benevolent form of cementing loyalty through alliances involved marriage arrangements between the Safavids and ruling families, officials in high military, administrative, and religious positions. This type of arrangement was particularly common in the case of Georgia. Shah `Abbas solidified the nexus with its royal house by giving Constantin Mirza’s sister in marriage to Prince Hamzah Mirza. A century later, Gurgin Khan, the Georgian commander-inchief of the Safavid army, married a daughter of Ja`far Quli Khan. of Sistan in a union designed to strengthen ties between Isfahan and that remote area. Sexual politics might even extend to the “barbarian” periphery. Shah Tahmasb gave a daughter in marriage to `Adil Giray, a Tartar chief whom he kept as a hostage, in hopes of preventing the Tatars from siding with the Ottomans.

In the borderlands, where power was by definition a matter of negotiation, operating with tact and sensitivity was especially important. Borders looked linear to foreigners entering and leaving Iran at clearly defined transit stations, yet they were above all permeable frontier zones, unpacified mountains and deserts inhabited by tribal peoples whose loyalty might be temporarily bought but could never be taken for granted. The Arabs and Kurds along the Ottoman borders, the Lezghis in the Caucasus, the Turkmen in Khurasan, and the Baluchis and Afghans on the eastern marches were notorious for their unwillingness to submit to outside authority.

In an approach that goes back to antiquity, the Safavids sought to bring security to such areas by making alliances with tribal chiefs, enlisting them through arrangements in which the latter pledged to defend the frontier in exchange for maintaining their local autonomy. This might take the form of a tribe submitting to the shah as “lovers of the shah,” shah-seven, as Kurds from the Hakkari region did when they disavowed loyalty to the Ottomans and offered their service to the Safavids, thus facilitating the taking of Van by the latter.

The tribal support the state needed, for intelligence and actual assistance in case of war, gave great leverage to the chieftains. The shah picked the Lezghi ruler, the shamkhal, but always from one of the local princes and with the consent of local forces, thus ensuring the stability that was the ultimate rationale of any such arrangement. In 1595 Shah `Abbas I agreed to a temporary subordination of the shamkhal to Russia, stressing that he was an Iranian vassal even if he was an underling of the czar.

In the Safavid–Ottoman borderlands, especially, too much pressure from Isfahan or Istanbul might drive a tribe into the arms of the other regime. Iskandar Beg Munshi called the Kurds fickle, deploring their tendency to switch sides in the conflict with the Ottomans. A policy of leniency and accommodation was vital in such conditions. This is probably why Khalil Khan, the governor of Bakhtiyari territory, was just deposed—as opposed to executed—after his people had risen in revolt against his violent oppression, and why he managed to regain his post twelve years later. Similarly, Shah `Abbas II received Mansur Khan, the ruler of Huwayza, with great pomp and circumstance in Isfahan in 1645, after he had led a rebellion against the Safavids. Sulayman Khan, the Kurdish beglerbeg of Ardalan, in 1657 took the side of Istanbul and tried to escape to Ottoman territory. Caught, he was only exiled to Mashhad for this act of treason. Not only that, but Shah `Abbas II, who had little interest in conflict with either the Kurds or the Ottomans, allowed him to be succeeded by his oldest son, Kalb `Ali Khan.

Loyalty was often literally bought, either with cash or by way of lucrative concessions. When Imam Quli Khan, the governor of Fars, marched against Basra in 1628, he got the Arab tribes en route to render him a variety of services by handing out “cash grants, robes of honor, and other gifts in profusion.” The Afghan warlord Mir Ways in the early eighteenth century served as qafilah-salar, supervisor of the caravan trade between Iran and India. The Safavids also made more institutionalized arrangements with various tribal peoples.

Shah `Abbas II coopted the Lezghis through a mutually beneficial tributary arrangement: They sent gifts to Isfahan as a token of fealty, and in turn received 1,700 tumans per annum from the shah to ensure stability and the protection of the border against other marauders. This arrangement included the resettling of large numbers of tribesmen from the mountains of Darband and Qubbah.The same ruler paid the Kharazmian ruler Abu’l Ghazi Khan an annual allowance of 1,500 tumans during a decade of gilded captivity in Isfahan, and kept disbursing this sum even after Abu’l Ghazi had escaped and regained power in Central Asia, simply to keep him from turning against Iran. After the shah had conducted several campaigns against the Uzbeks, he struck a deal whereby they received an annual stipend in exchange for a promise to desist from raiding—a promise they promptly broke following the shah’s death in 1666.”

- Rudi Matthee, Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. London: I. B. Tauris, 2012. pp. 144-148.

#دودمان صفوی#safavid iran#history of iran#iranian history#safavids#methods of rule#ruling class#hostage taking#population transfer#kinship politics#shah-seven#ideology of empire#marriage alliance#royal court#early modern state#limits of the absolutist state#beglerbeg#state office#military office#vakil#sardar#rudi matthee#safavid persia#academic quote#musketeers#possession of a firearm

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The north: Shirvan

“The north was important to the financial health of the Safavid realm; the Caspian provinces, especially, generated large amounts of money for the royal treasury. Taxes on the silk production in Gilan and Shirvan amounted to 100,000 tumans per year, contributing greatly to overall state revenue. But Iran’s northwestern provinces also bore the brunt of the Ottoman–Safavid wars, and Shamakhi, Shirvan’s capital, suffered tremendously when in 1667 it was struck by a devastating earthquake. In the same period Gilan and Talish were dealt a heavy blow with the irruptions of Cossack marauders led by Sten’ka Razin. The Cossacks took Astrakhan, temporarily disrupting the trade link between Iran and Russia, and almost seized Darband. They devastated large tracts of Gilan and Mazandaran, including the royal winter resort of Farahabad and the town of Astarabad, and did great damage to the silk cultivation in those regions.

We get a fairly detailed overview of the misery in the northern countryside, as well as an idea about its causes, from a lengthy report written by the Jesuit Father Jean-Baptiste de la Maze (1624–1709), who for many years served as his order’s representative in Shamakhi, and who thus was as familiar with the state of the country as any foreigner could be expected to be.93 Traveling through Shirvan and Azerbaijan in 1684, he called the thirty-four villages in the Baku region all poor, adding that the city itself was no exception, having been terribly neglected for generations. Most of the houses were ruined or abandoned, and in the entire city one saw no more than ten or twelve shops that were open.

He listed two reasons for these sorry conditions—one structural, the other contingent and man-made. The first was the poor quality of the soil, which was either rocky or sandy and, lacking water, best suited as grazing ground for nomads. Of the crops he saw he singled out cotton, which grew in great abundance, enabling large-scale local textile manufacturing, and saffron. De la Maze speculated that the production of saffron between Baku and Nizovoi could be for the region what silk was for Shirvan, but that the second reason of the depressed state of the land, the abuse and violence by local officials, prevented this from coming about.

The tax farmers in particular were keen immediately to recoup the money they had invested to obtain a three-year lease on the land, including all the presents and bribes they had been forced to disburse in the process. The present tax farmer, De la Maze noted, was supposed to send an annual sum of 7,000 tumans to Isfahan. The region’s petroleum—used as a medicine and as a lighting fuel, among other things—only yielded 600 tumans, so that the remainder had to come from salt and additional exactions, which were so onerous, De la Maze insisted, that they drove the region’s inhabitants to ruin.

By way of example he offered the case of one peasant he had spoken to, who owned no more than a small garden and yet had to pay 100 livres, or more than one tuman, per annum—a very large sum indeed given a 3-tuman average salary for a government servant at the time. At the end of a tax farmer’s term, a new one, even hungrier for revenue, would arrive, making the hapless peasants abandon their land out of sheer desperation. Everyone, the French Jesuit maintained, was anxiously anticipating the arrival of Mirza Tahir, who had been sent by Isfahan to take stock of the province and bring relief to the suffering inhabitants. In the meantime only four villages retained a semblance of prosperity, their inhabitants eking out a living on the basis of rotating weekly markets. Two of these were exceptions to the general misery. Shah `Abbas I had given both as a hereditary fief (suyurghal) to a shaykh, and the latter and his descendants had governed their property with justice, only forcing the peasants to engage in light corvée labor, which meant that they worked for the owner no more than six days per year.

Not everything spoke of deprivation, to be sure. The region might be suffering economically, De la Maze observed, but it was also safe—so safe, in fact, that even a small child could carry a bag full of money from village to village without being bothered. The only threat to regional security was posed by the Cossacks, who from time to time engaged in piracy, landing on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea to raid the coastal towns and villages. Hence the defensive towers that had been built in almost all of them and that now were falling to ruin because of neglect. Yet by the late seventeenth century cracks were appearing in Iran’s much-vaunted road safety, and the north had its fair share of the growing turmoil. In the winter of 1680 a caravan coming from Izmir was robbed of 20,000 tumans near Yerevan. Aside from costing the lives of thirty men, this robbery ruined a number of merchants, Muslim as well as Armenian. The governor of Yerevan was suspected of having had a hand in the affair, one of several caravan robberies that remained unresolved.”

- Rudi Matthee, Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. London: I. B. Tauris, 2012. pp. 154-155

#دودمان صفوی#safavids#safavid iran#shirvan#gilan#baku#shamakhi#khassah#methods of rule#what the ruling class does when it rules#tax farming#tax farmers#state revenues#extractive state#early modern state#safavid persia#rudi matthee#iranian history#history of iran#sources of revenue#academic quote#azerbaijan#cossacks

0 notes

Text

Arrangements between the center and the provinces

“Various landed and administrative arrangements tied the periphery to the capital, the royal court, and its administrative apparatus. These were mamalik or divani, state lands, khassah, royal domain lands, and vilayats, autonomously administered regions.

A variant of the Buyid iqta`, the mamalik arrangement—a form of prebendalism in which landed property was alienated as fiefs—reflected the government’s dependence on tribal military troops for the defense of the realm. The granting of mamalik land was a way of rewarding the regime’s supporters, the Qizilbash chieftains, for military vigilance and the payment of a limited fixed annual sum to the royal treasury. In early Safavid times all of Iran was mamalik land. Over time, as the regime consolidated its authority and security increased, some centrally located regions were converted to crown land, khassah. The frontier provinces, where the need for military vigilance remained urgent, continued to be mamalik territory, which explains why outlying regions such as Khurasan, Azerbaijan, and Qarabagh remained tribally controlled state domain throughout the Safavid period.

Such control was not fixed, though. Tribes tended to have a long-standing connection with a region; yet the influence and power of individual tribes fluctuated over time. In the early sixteenth century, for instance, the Takallu wielded disproportional power in Iran. They lost their dominance under Shah Tahmasb, to be overtaken by the Ustajlu, whose rise was so spectacular that in the 1570s they held two-thirds of all governorships. The Shamlu, who had been associated with Khurasan from the time Shah Isma`il conquered the region in the early 1500s, fell into disgrace during Shah Tahmasb’s reign, but rose again under Shah `Abbas I, gaining a monopoly on Khurasan’s governorship following the death of Farhad Khan Qaramanlu, after which they controlled the region until the end of Safavid rule. The Qajar and the Afshar were two other tribes with great power in later times. The former, who hailed from the north, ruled the area of Astarabad—a frontier region perennially exposed to Uzbek incursions—throughout the seventeenth century. They also came to control Yerevan and Tiflis in the northwest after Shah `Abbas I seized those cities from the Ottomans.

The Ziyad Ughlu, one of their subgroups, commanded the borderlands of Qarabagh, Ganja, and Chughur-i Sa`d in the southern Caucasus from the days of Shah Tahmasb onward. The Afshar were not just concentrated in Khurasan, but held sway over parts of Khuzistan and Kuh-i Giluyah. In early Safavid times they also came to rule Kirman province. Kirman remained under their control until the early reign of Shah `Abbas I, who appointed the Kurd Ganj `Ali Khan, one of his most loyal servants, as its governor. The Afshar were subsequently forced to cede power to the Kurds in the Kirman area, although in the late Safavid period intensifying Baluchi attacks prompted the central state to allow them to return to help defend the province.

Mamalik land was also routinely linked to specific administrative offices, by way of governance or income. From the time of Shah Isma`il I onward, the governor of Azerbaijan, a rich province and a recruiting ground for some of Iran’s best soldiers, regularly held the post of amir al-umara (an old term for commander-in-chief) and sipahsalar, commander of the armed forces. The district of Abarquh was assigned to the tufangchi-aqasi, head of the musketeers, and as of 1645 the post of qullar-aqasi, head of the slave soldiers, was tied to the governorship of Kuh-i Giluyah. The amir-shikar-bashi (master of the hunt) derived (part of) his income from the revenue of Abhar, between Qazvin and Sultaniyah. The position of ishik-aqasi-bashi (royal chamberlain) was vested in the Shamlu tribe. Members of the Afshar had a lock on the position of ishik-aqasi-yi khassah. And from the reign of Shah Safi I, the governorate of Kirman came with the post of qurchibashi.

Mamalik land secured border regions with tribal military power but gave the central government little direct control and scant revenue. To increase both, the state over time transferred a great deal of land to crown domain. The long-term conversion to khassah land reflects a shift from a decentralized polity beholden to tribal military power to an agrarian-based system in which tribal chieftains came to be subordinated to the new, centrally appointed ghulam class of soldiers and bureaucrats.

As stated, the centrally located, most secure parts of the country were the first to be turned into crown domain. Shah `Abbas declared Kashan crown land in 1590 and, upon seizing Isfahan in the same year, gave that city and its surroundings similar status. The conversion of Gilan and Mazandaran to crown land in 1599 spelled the end of local dynastic rule in the Caspian region. Contrary to conventional wisdom, crown land and ghulam rule were not inherently connected. Ghulams came to dominate Fars with the appointment of Allah Virdi Khan in 1595, but the province only became crown domain in 1633, after his son, Imam Quli Khan, was killed on Shah Safi’s orders. Conversely, when Kirman was turned into khassah land in 1658–9, it was not brought under ghulam control but rather saw a growing influx of Kurds.

Vilayats were located in border regions beyond the mountain ranges that framed the central plateau. These were mostly mountainous areas, located on the edge of Safavid jurisdiction and inhabited by fiercely independent tribal people. The five vilayats in late Safavid times were `Arabistan (modern Khuzistan), Luristan, Georgia, Kurdistan, and Bakhtiyari territory, in that order of ranking. Valis were all but independent governors. Hailing from leading local families, they usually ruled in hereditary fashion even if they were officially appointed by the shah, who in a concession to regional autonomy almost always chose a candidate from the region. Appointing someone from outside the resident tribe might create more problems than it solved, as is shown by the example of Kurdistan, where in the 1680s a non-Kurdish governor dispatched by Shah Sulayman was run out of town by the local population.

Good behavior by chieftains was enforced by means of keeping a family member, typically a son, in Isfahan as a hostage. Valis formally expressed allegiance to Isfahan and had coins struck in the shah’s name. Unlike regular governors, however, valis oversaw their regions’ administrative apparatus, controlled their own budgets, maintained their own militia, and managed their own vassal relations, in all of which the shah rarely intervened.

The tributary strategy the Safavids employed vis-à-vis vilayats varied with circumstances. Ordinarily, the exactions were light. Thus Luristan in late Safavid times annually supplied only twenty Arabian horses in addition to 200 mules and a quantity of valuables. In time of war, however, the Lurs were held to provide up to 12,000 cavalrymen and the same number of foot soldiers. - Rudi Matthee, Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. London: I. B. Tauris, 2012. pp. 141-144.

#دودمان صفوی#safavid iran#land tenure#mamalik#khassah#fiefdoms#qizilbash#tribal society#tribal organization#state revenues#limits of the absolutist state#early modern society#early modern state#history of iran#iranian history#rudi matthee#sources of revenue#crown lands#ghulams#bureaucratic reform#safavids#academic quote#iranian hisory

1 note

·

View note