#as if the author had based everyone on the most basic pop culture image of themselves

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How the HELL am I reading a comic where they are putting King Arthur against DRACULA of all people, AND IT IS STILL THE EXACT SAME OLD STORY?!

People should be banned from using the Grail Quest and the Arthur/Lancelot/Guinevere love triangle in their stories until, I don’t know, they have completed a quiz proving that they actually know other parts of the mythos too, or something.

#nothing against retellings#BUT IT'S ALWAYS THE EXACT SAME THING!!#I'm tired!!!#This is the Arthurian legend!!#you could have your pick from SO MANY stories!!#Especially if you bring in a time travelling Dracula for some reason#like this comic should be UNHINGED#IT IS NOT#it just feels boring and shallow#as if the author had based everyone on the most basic pop culture image of themselves#and not even tried to give their characters depth#Arthur is looking for the Grail#because that's what Arthur does#Morgana and Mordred are powerhungry cartoon villains plotting Arthur's death#because that's what Morgan and Mordred do#Dracula is a monster and murders people#Lancelot and Guinevere are about to start having an affair...#you get the picture#It's. It's frikking DRACULA.#IN CAMELOT#AND YOU STILL DIDN'T MANAGE TO MAKE IT ORIGINAL IN SOME WAY?!??!#Arthurian legend#Dracula vs King Arthur#comic books#way to common problem with Arthurian adaptations unfortunately#Writers do some fucking research challenge

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Other Afghan Women

In the countryside, the endless killing of civilians turned women against the occupiers who claimed to be helping them.

— By Anand Gopal | September 6, 2021 | The New Yorker

More than seventy per cent of Afghans do not live in cities. In rural areas, life under the U.S.-led coalition and its Afghan allies became pure hazard; even drinking tea in a sunlit field, or driving to your sister’s wedding, was a potentially deadly gamble.Photograph by Stephen Dupont / Contact Press Images

Late one afternoon this past August, Shakira heard banging on her front gate. In the Sangin Valley, which is in Helmand Province, in southern Afghanistan, women must not be seen by men who aren’t related to them, and so her nineteen-year-old son, Ahmed, went to the gate. Outside were two men in bandoliers and black turbans, carrying rifles. They were members of the Taliban, who were waging an offensive to wrest the countryside back from the Afghan National Army. One of the men warned, “If you don’t leave immediately, everyone is going to die.”

Shakira, who is in her early forties, corralled her family: her husband, an opium merchant, who was fast asleep, having succumbed to the temptations of his product, and her eight children, including her oldest, twenty-year-old Nilofar—as old as the war itself—whom Shakira called her “deputy,” because she helped care for the younger ones. The family crossed an old footbridge spanning a canal, then snaked their way through reeds and irregular plots of beans and onions, past dark and vacant houses. Their neighbors had been warned, too, and, except for wandering chickens and orphaned cattle, the village was empty.

Shakira’s family walked for hours under a blazing sun. She started to feel the rattle of distant thuds, and saw people streaming from riverside villages: men bending low beneath bundles stuffed with all that they could not bear to leave behind, women walking as quickly as their burqas allowed.

The pounding of artillery filled the air, announcing the start of a Taliban assault on an Afghan Army outpost. Shakira balanced her youngest child, a two-year-old daughter, on her hip as the sky flashed and thundered. By nightfall, they had come upon the valley’s central market. The corrugated-iron storefronts had largely been destroyed during the war. Shakira found a one-room shop with an intact roof, and her family settled in for the night. For the children, she produced a set of cloth dolls—one of a number of distractions that she’d cultivated during the years of fleeing battle. As she held the figures in the light of a match, the earth shook.

Around dawn, Shakira stepped outside, and saw that a few dozen families had taken shelter in the abandoned market. It had once been the most thriving bazaar in northern Helmand, with shopkeepers weighing saffron and cumin on scales, carts loaded with women’s gowns, and storefronts dedicated to selling opium. Now stray pillars jutted upward, and the air smelled of decaying animal remains and burning plastic.

In the distance, the earth suddenly exploded in fountains of dirt. Helicopters from the Afghan Army buzzed overhead, and the families hid behind the shops, considering their next move. There was fighting along the stone ramparts to the north and the riverbank to the west. To the east was red-sand desert as far as Shakira could see. The only option was to head south, toward the leafy city of Lashkar Gah, which remained under the control of the Afghan government.

The journey would entail cutting through a barren plain exposed to abandoned U.S. and British bases, where snipers nested, and crossing culverts potentially stuffed with explosives. A few families started off. Even if they reached Lashkar Gah, they could not be sure what they’d find there. Since the start of the Taliban’s blitz, Afghan Army soldiers had surrendered in droves, begging for safe passage home. It was clear that the Taliban would soon reach Kabul, and that the twenty years, and the trillions of dollars, devoted to defeating them had come to nothing. Shakira’s family stood in the desert, discussing the situation. The gunfire sounded closer. Shakira spotted Taliban vehicles racing toward the bazaar—and she decided to stay put. She was weary to the bone, her nerves frayed. She would face whatever came next, accept it like a judgment. “We’ve been running all our lives,” she told me. “I’m not going anywhere.”

The longest war in American history ended on August 15th, when the Taliban captured Kabul without firing a shot. Bearded, scraggly men with black turbans took control of the Presidential palace, and around the capital the austere white flags of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan went up. Panic ensued. Some women burned their school records and went into hiding, fearing a return to the nineteen-nineties, when the Taliban forbade them to venture out alone and banned girls’ education. For Americans, the very real possibility that the gains of the past two decades might be erased appeared to pose a dreadful choice: recommit to seemingly endless war, or abandon Afghan women.

This summer, I travelled to rural Afghanistan to meet women who were already living under the Taliban, to listen to what they thought about this looming dilemma. More than seventy per cent of Afghans do not live in cities, and in the past decade the insurgent group had swallowed large swaths of the countryside. Unlike in relatively liberal Kabul, visiting women in these hinterlands is not easy: even without Taliban rule, women traditionally do not speak to unrelated men. Public and private worlds are sharply divided, and when a woman leaves her home she maintains a cocoon of seclusion through the burqa, which predates the Taliban by centuries. Girls essentially disappear into their homes at puberty, emerging only as grandmothers, if ever. It was through grandmothers—finding each by referral, and speaking to many without seeing their faces—that I was able to meet dozens of women, of all ages. Many were living in desert tents or hollowed-out storefronts, like Shakira; when the Taliban came across her family hiding at the market, the fighters advised them and others not to return home until someone could sweep for mines. I first encountered her in a safe house in Helmand. “I’ve never met a foreigner before,” she said shyly. “Well, a foreigner without a gun.”

Shakira has a knack for finding humor in pathos, and in the sheer absurdity of the men in her life: in the nineties, the Taliban had offered to supply electricity to the village, and the local graybeards had initially refused, fearing black magic. “Of course, we women knew electricity was fine,” she said, chuckling. When she laughs, she pulls her shawl over her face, leaving only her eyes exposed. I told her that she shared a name with a world-renowned pop star, and her eyes widened. “Is it true?” she asked a friend who’d accompanied her to the safe house. “Could it be?”

Shakira, like the other women I met, grew up in the Sangin Valley, a gash of green between sharp mountain outcrops. The valley is watered by the Helmand River and by a canal that Americans built in the nineteen-fifties. You can walk the width of the dale in an hour, passing dozens of tiny hamlets, creaking footbridges, and mud-brick walls. As a girl, Shakira heard stories from her mother of the old days in her village, Pan Killay, which was home to about eighty families: the children swimming in the canal under the warm sun, the women pounding grain in stone mortars. In winter, smoke wafted from clay hearths; in spring, rolling fields were blanketed with poppies.

In 1979, when Shakira was an infant, Communists seized power in Kabul and tried to launch a female-literacy program in Helmand—a province the size of West Virginia, with few girls’ schools. Tribal elders and landlords refused. In the villagers’ retelling, the traditional way of life in Sangin was smashed overnight, because outsiders insisted on bringing women’s rights to the valley. “Our culture could not accept sending their girls outside to school,” Shakira recalled. “It was this way before my father’s time, before my grandfather’s time.” When the authorities began forcing girls to attend classes at gunpoint, a rebellion erupted, led by armed men calling themselves the mujahideen. In their first operation, they kidnapped all the schoolteachers in the valley, many of whom supported girls’ education, and slit their throats. The next day, the government arrested tribal elders and landlords on the suspicion that they were bankrolling the mujahideen. These community leaders were never seen again.

Tanks from the Soviet Union crossed the border to shore up the Communist government—and to liberate women. Soon, Afghanistan was basically split in two. In the countryside, where young men were willing to die fighting the imposition of new ways of life—including girls’ schools and land reform—young women remained unseen. In the cities, the Soviet-backed government banned child marriage and granted women the right to choose their partners. Girls enrolled in schools and universities in record numbers, and by the early eighties women held parliamentary seats and even the office of Vice-President.

The violence in the countryside continued to spread. Early one morning when Shakira was five, her aunt awakened her in a great hurry. The children were led by the adults of the village to a mountain cave, where they huddled for hours. At night, Shakira watched artillery streak the sky. When the family returned to Pan Killay, the wheat fields were charred, and crisscrossed with the tread marks of Soviet tanks. The cows had been mowed down with machine guns. Everywhere she looked, she saw neighbors—men she used to call “uncle”—lying bloodied. Her grandfather hadn’t hidden with her, and she couldn’t find him in the village. When she was older, she learned that he’d gone to a different cave, and had been caught and executed by the Soviets.

Nighttime evacuations became a frequent occurrence and, for Shakira, a source of excitement: the dark corners of the caves, the clamorous groups of children. “We would look for Russian helicopters,” she said. “It was like spotting strange birds.” Sometimes, those birds swooped low, the earth exploded, and the children rushed to the site to forage for iron, which could be sold for a good price. Occasionally she gathered metal shards so that she could build a doll house. Once, she showed her mother a magazine photograph of a plastic doll that exhibited the female form; her mother snatched it away, calling it inappropriate. So Shakira learned to make dolls out of cloth and sticks.

When she was eleven, she stopped going outside. Her world shrank to the three rooms of her house and the courtyard, where she learned to sew, bake bread in a tandoor, and milk cows. One day, passing jets rattled the house, and she took sanctuary in a closet. Underneath a pile of clothes, she discovered a child’s alphabet book that had belonged to her grandfather—the last person in the family to attend school. During the afternoons, while her parents napped, she began matching the Pashto words to pictures. She recalled, “I had a plan to teach myself a little every day.”

In 1989, the Soviets withdrew in defeat, but Shakira continued to hear the pounding of mortars outside the house’s mud walls. Competing mujahideen factions were now trying to carve up the country for themselves. Villages like Pan Killay were lucrative targets: there were farmers to tax, rusted Soviet tanks to salvage, opium to export. Pazaro, a woman from a nearby village, recalled, “We didn’t have a single night of peace. Our terror had a name, and it was Amir Dado.”

The first time Shakira saw Dado, through the judas of her parents’ front gate, he was in a pickup truck, trailed by a dozen armed men, parading through the village “as if he were the President.” Dado, a wealthy fruit vender turned mujahideen commander, with a jet-black beard and a prodigious belly, had begun attacking rival strongmen even before the Soviets’ defeat. He hailed from the upper Sangin Valley, where his tribe, the Alikozais, had held vast feudal plantations for centuries. The lower valley was the home of the Ishaqzais, the poor tribe to which Shakira belonged. Shakira watched as Dado’s men went from door to door, demanding a “tax” and searching homes. A few weeks later, the gunmen returned, ransacking her family’s living room while she cowered in a corner. Never before had strangers violated the sanctity of her home, and she felt as if she’d been stripped naked and thrown into the street.

By the early nineties, the Communist government of Afghanistan, now bereft of Soviet support, was crumbling. In 1992, Lashkar Gah fell to a faction of mujahideen. Shakira had an uncle living there, a Communist with little time for the mosque and a weakness for Pashtun tunes. He’d recently married a young woman, Sana, who’d escaped a forced betrothal to a man four times her age. The pair had started a new life in Little Moscow, a Lashkar Gah neighborhood that Sana called “the land where women have freedom”—but, when the mujahideen took over, they were forced to flee to Pan Killay.

Shakira was tending the cows one evening when Dado’s men surrounded her with guns. “Where’s your uncle?” one of them shouted. The fighters stormed into the house—followed by Sana’s spurned fiancé. “She’s the one!” he said. The gunmen dragged Sana away. When Shakira’s other uncles tried to intervene, they were arrested. The next day, Sana’s husband turned himself in to Dado’s forces, begging to be taken in her place. Both were sent to the strongman’s religious court and sentenced to death.

Not long afterward, the mujahideen toppled the Communists in Kabul, and they brought their countryside mores with them. In the capital, their leaders—who had received generous amounts of U.S. funding—issued a decree declaring that “women are not to leave their homes at all, unless absolutely necessary, in which case they are to cover themselves completely.” Women were likewise banned from “walking gracefully or with pride.” Religious police began roaming the city’s streets, arresting women and burning audio- and videocassettes on pyres.

Yet the new mujahideen government quickly fell apart, and the country descended into civil war. At night in Pan Killay, Shakira heard gunfire and, sometimes, the shouts of men. In the morning, while tending the cows, she’d see neighbors carrying wrapped bodies. Her family gathered in the courtyard and discussed, in low voices, how they might escape. But the roads were studded with checkpoints belonging to different mujahideen groups. South of the village, in the town of Gereshk, a militia called the Ninety-third Division maintained a particularly notorious barricade on a bridge; there were stories of men getting robbed or killed, of women and young boys being raped. Shakira’s father sometimes crossed the bridge to sell produce at the Gereshk market, and her mother started pleading with him to stay home.

The family, penned between Amir Dado to the north and the Ninety-third Division to the south, was growing desperate. Then one afternoon, when Shakira was sixteen, she heard shouts from the street: “The Taliban are here!” She saw a convoy of white Toyota Hiluxes filled with black-turbanned fighters carrying white flags. Shakira hadn’t ever heard of the Taliban, but her father explained that its members were much like the poor religious students she’d seen all her life begging for alms. Many had fought under the mujahideen’s banner but quit after the Soviets’ withdrawal; now, they said, they were remobilizing to put an end to the tumult. In short order, they had stormed the Gereshk bridge, dismantling the Ninety-third Division, and volunteers had flocked to join them as they’d descended on Sangin. Her brother came home reporting that the Taliban had also overrun Dado’s positions. The warlord had abandoned his men and fled to Pakistan. “He’s gone,” Shakira’s brother kept saying. “He really is.” The Taliban soon dissolved Dado’s religious court—freeing Sana and her husband, who were awaiting execution—and eliminated the checkpoints. After fifteen years, the Sangin Valley was finally at peace.

When I asked Shakira and other women from the valley to reflect on Taliban rule, they were unwilling to judge the movement against some universal standard—only against what had come before. “They were softer,” Pazaro, the woman who lived in a neighboring village, said. “They were dealing with us respectfully.” The women described their lives under the Taliban as identical to their lives under Dado and the mujahideen—minus the strangers barging through the doors at night, the deadly checkpoints.

Shakira recounted to me a newfound serenity: quiet mornings with steaming green tea and naan bread, summer evenings on the rooftop. Mothers and aunts and grandmothers began to discreetly inquire about her eligibility; in the village, marriage was a bond uniting two families. She was soon betrothed to a distant relative whose father had vanished, presumably at the hands of the Soviets. The first time she laid eyes on her fiancé was on their wedding day: he was sitting sheepishly, surrounded by women of the village, who were ribbing him about his plans for the wedding night. “Oh, he was a fool!” Shakira recalled, laughing. “He was so embarrassed, he tried to run away. People had to catch him and bring him back.”

Like many enterprising young men in the valley, he was employed in opium trafficking, and Shakira liked the glint of determination in his eyes. Yet she started to worry that grit alone might not be enough. As Taliban rule established itself, a conscription campaign was launched. Young men were taken to northern Afghanistan, to help fight against a gang of mujahideen warlords known as the Northern Alliance. One day, Shakira watched a helicopter alight in a field and unload the bodies of fallen conscripts. Men in the valley began hiding in friends’ houses, moving from village to village, terrified of being called up. Impoverished tenant farmers were the most at risk—the rich could buy their way out of service. “This was the true injustice of the Taliban,” Shakira told me. She grew to loathe the sight of roving Taliban patrols.

In 2000, Helmand Province experienced punishing drought. The watermelon fields lay ruined, and the bloated corpses of draft animals littered the roads. In a flash of cruelty, the Taliban’s supreme leader, Mullah Omar, chose that moment to ban opium cultivation. The valley’s economy collapsed. Pazaro recalled, “We had nothing to eat, the land gave us nothing, and our men couldn’t provide for our children. The children were crying, they were screaming, and we felt like we’d failed.” Shakira, who was pregnant, dipped squares of stale naan into green tea to feed her nieces and nephews. Her husband left for Pakistan, to try his luck in the fields there. Shakira was stricken by the thought that her baby would emerge lifeless, that her husband would never return, that she would be alone. Every morning, she prayed for rain, for deliverance.

One day, an announcer on the radio said that there had been an attack in America. Suddenly, there was talk that soldiers from the richest country on earth were coming to overthrow the Taliban. For the first time in years, Shakira’s heart stirred with hope.

One night in 2003, Shakira was jolted awake by the voices of strange men. She rushed to cover herself. When she ran to the living room, she saw, with panic, the muzzles of rifles being pointed at her. The men were larger than she’d ever seen, and they were in uniform. These are the Americans, she realized, in awe. Some Afghans were with them, scrawny men with Kalashnikovs and checkered scarves. A man with an enormous beard was barking orders: Amir Dado.

The U.S. had swiftly toppled the Taliban following its invasion, installing in Kabul the government of Hamid Karzai. Dado, who had befriended American Special Forces, became the chief of intelligence for Helmand Province. One of his brothers was the governor of the Sangin district, and another brother became Sangin’s chief of police. In Helmand, the first year of the American occupation had been peaceful, and the fields once again burst with poppies. Shakira now had two small children, Nilofar and Ahmed. Her husband had returned from Pakistan and found work ferrying bags of opium resin to the Sangin market. But now, with Dado back in charge—rescued from exile by the Americans—life regressed to the days of civil war.

Nearly every person Shakira knew had a story about Dado. Once, his fighters demanded that two young men either pay a tax or join his private militia, which he maintained despite holding his official post. When they refused, his fighters beat them to death, stringing their bodies up from a tree. A villager recalled, “We went to cut them down, and they had been sliced open, their stomachs coming out.” In another village, Dado’s forces went from house to house, executing people suspected of being Taliban; an elderly scholar who’d never belonged to the movement was shot dead.

Shakira was bewildered by the Americans’ choice of allies. “Was this their plan?” she asked me. “Did they come to bring peace, or did they have other aims?” She insisted that her husband stop taking resin to the Sangin market, so he shifted his trade south, to Gereshk. But he returned one afternoon with the news that this, too, had become impossible. Astonishingly, the United States had resuscitated the Ninety-third Division—and made it its closest partner in the province. The Division’s gunmen again began stopping travellers on the bridge and plundering what they could. Now, however, their most profitable endeavor was collecting bounties offered by the U.S.; according to Mike Martin, a former British officer who wrote a history of Helmand, they earned up to two thousand dollars per Taliban commander captured.

This posed a challenge, though, because there were hardly any active Taliban to catch. “We knew who were the Taliban in our village,” Shakira said, and they weren’t engaged in guerrilla warfare: “They were all sitting at home, doing nothing.” A lieutenant colonel with U.S. Special Forces, Stuart Farris, who was deployed to the area at that time, told a U.S. Army historian, “There was virtually no resistance on this rotation.” So militias like the Ninety-third Division began accusing innocent people. In February, 2003, they branded Hajji Bismillah—the Karzai government’s transportation director for Gereshk, responsible for collecting tolls in the city—a terrorist, prompting the Americans to ship him to Guantánamo. With Bismillah eliminated, the Ninety-third Division monopolized the toll revenue.

Dado went even further. In March, 2003, U.S. soldiers visited Sangin’s governor—Dado’s brother—to discuss refurbishing a school and a health clinic. Upon leaving, their convoy came under fire, and Staff Sergeant Jacob Frazier and Sergeant Orlando Morales became the first American combat fatalities in Helmand. U.S. personnel suspected that the culprit was not the Taliban but Dado—a suspicion confirmed to me by one of the warlord’s former commanders, who said that his boss had engineered the attack to keep the Americans reliant on him. Nonetheless, when Dado’s forces claimed to have nabbed the true assassin—an ex-Taliban conscript named Mullah Jalil—the Americans dispatched Jalil to Guantánamo. Unaccountably, this happened despite the fact that, according to Jalil’s classified Guantánamo file, U.S. officials knew that Jalil had been fingered merely to “cover for” the fact that Dado’s forces had been “involved with the ambush.”

The incident didn’t affect Dado’s relationship with U.S. Special Forces, who deemed him too valuable in serving up “terrorists.” They were now patrolling together, and soon after the attack the joint operation searched Shakira’s village for suspected terrorists. The soldiers did not stay at her home long, but she could not get the sight of the rifle muzzles out of her mind. The next morning, she removed the rugs and scrubbed the boot marks away.

Shakira’s friends and neighbors were too terrified to speak out, but the United Nations began agitating for Dado’s removal. The U.S. repeatedly blocked the effort, and a guide for the U.S. Marine Corps argued that although Dado was “far from being a Jeffersonian Democrat” his form of rough justice was “the time-tested solution for controlling rebellious Pashtuns.”

Shakira’s husband stopped leaving the house as Helmandis continued to be taken away on flimsy pretexts. A farmer in a nearby village, Mohammed Nasim, was arrested by U.S. forces and sent to Guantánamo because, according to a classified assessment, his name was similar to that of a Taliban commander. A Karzai government official named Ehsanullah visited an American base to inform on two Taliban members; no translator was present, and, in the confusion, he was arrested himself and shipped to Guantánamo. Nasrullah, a government tax collector, was sent to Guantánamo after being randomly pulled off a bus following a skirmish between U.S. Special Forces and local tribesmen. “We were so happy with the Americans,” he said later, at a military tribunal. “I didn’t know eventually I would come to Cuba.”

Nasrullah ultimately returned home, but some detainees never made it back. Abdul Wahid, of Gereshk, was arrested by the Ninety-third Division and beaten severely; he was delivered to U.S. custody and left in a cage, where he died. U.S. military personnel noted burns on his chest and stomach, and bruising to his hips and groin. According to a declassified investigation, Special Forces soldiers reported that Wahid’s wounds were consistent with “a normal interview/interrogation method” used by the Ninety-third Division. A sergeant stated that he “could provide photographs of prior detainees with similar injuries.” Nonetheless, the U.S. continued to support the Ninety-third Division—a violation of the Leahy Law, which bars American personnel from knowingly backing units that commit flagrant human-rights abuses.

In 2004, the U.N. launched a program to disarm pro-government militias. A Ninety-third commander learned of the plan and rebranded a segment of the militia as a “private-security company” under contract with the Americans, enabling roughly a third of the Division’s fighters to remain armed. Another third kept their weapons by signing a contract with a Texas-based firm to protect road-paving crews. (When the Karzai government replaced these private guards with police, the Ninety-third’s leader engineered a hit that killed fifteen policemen, and then recovered the contract.) The remaining third of the Division, finding themselves subjected to extortion threats from their former colleagues, absconded with their weapons and joined the Taliban.

Messaging by the U.S.-led coalition tended to portray the growing rebellion as a matter of extremists battling freedom, but nato documents I obtained conceded that Ishaqzais had “no good reason” to trust the coalition forces, having suffered “oppression at the hands of Dad Mohammad Khan,” or Amir Dado. In Pan Killay, elders encouraged their sons to take up arms to protect the village, and some reached out to former Taliban members. Shakira wished that her husband would do something—help guard the village, or move them to Pakistan—but he demurred. In a nearby village, when U.S. forces raided the home of a beloved tribal elder, killing him and leaving his son with paraplegia, women shouted at their menfolk, “You people have big turbans on your heads, but what have you done? You can’t even protect us. You call yourselves men?”

It was now 2005, four years after the American invasion, and Shakira had a third child on the way. Her domestic duties consumed her—“morning to night, I was working and sweating”—but when she paused from stoking the tandoor or pruning the peach trees she realized that she’d lost the sense of promise she’d once felt. Nearly every week, she heard of another young man being spirited away by the Americans or the militias. Her husband was unemployed, and recently he’d begun smoking opium. Their marriage soured. An air of mistrust settled onto the house, matching the village’s grim mood.

So when a Taliban convoy rolled into Pan Killay, with black-turbanned men hoisting tall white flags, she considered the visitors with interest, even forgiveness. This time, she thought, things might be different.

In 2006, the U.K. joined a growing contingent of U.S. Special Operations Forces working to quell the rebellion in Sangin. Soon, Shakira recalled, “hell began.” The Taliban attacked patrols, launched raids on combat outposts, and set up roadblocks. On a hilltop in Pan Killay, the Americans commandeered a drug lord’s house, transforming it into a compound of sandbags and watchtowers and concertina wire. Before most battles, young Talibs visited houses, warning residents to leave immediately. Then the Taliban would launch their assault, the coalition would respond, and the earth would shudder.

Sometimes, even fleeing did not guarantee safety. During one battle, Abdul Salam, an uncle of Shakira’s husband, took refuge in a friend’s home. After the fighting ended, he visited a mosque to offer prayers. A few Taliban were there, too. A coalition air strike killed almost everyone inside. The next day, mourners gathered for funerals; a second strike killed a dozen more people. Among the bodies returned to Pan Killay were those of Abdul Salam, his cousin, and his three nephews, aged six to fifteen.

Not since childhood had Shakira known anyone who’d died by air strike. She was now twenty-seven, and she slept fitfully, as if at any moment she’d need to run for cover. One night, she awoke to a screeching noise so loud that she wondered if the house was being torn apart. Her husband was still snoring away, and she cursed him under her breath. She tiptoed to the front yard. Coalition military vehicles were passing by, trundling over scrap metal strewn out front. She roused the family. It was too late to evacuate, and Shakira prayed that the Taliban would not attack. She thrust the children into recessed windows—a desperate attempt to protect them in case a strike caused the roof to collapse—and covered them with heavy blankets.

Returning to the front yard, Shakira spotted one of the foreigners’ vehicles sitting motionless. A pair of antennas projected skyward. They’re going to kill us, she thought. She climbed onto the roof, and saw that the vehicle was empty: the soldiers had parked it and left on foot. She watched them march over the footbridge and disappear into the reeds.

A few fields away, the Taliban and the foreigners began firing. For hours, the family huddled indoors. The walls shook, and the children cried. Shakira brought out her cloth dolls, rocked Ahmed against her chest, and whispered stories. When the guns fell silent, around dawn, Shakira went out for another look. The vehicle remained there, unattended. She was shaking in anger. All year, roughly once a month, she had been subjected to this terror. The Taliban had launched the attack, but most of her rage was directed at the interlopers. Why did she, and her children, have to suffer?

A wild thought flashed through her head. She rushed into the house and spoke with her mother-in-law. The soldiers were still on the far side of the canal. Shakira found some matches and her mother-in-law grabbed a jerrican of diesel fuel. On the street, a neighbor glanced at the jerrican and understood, hurrying back with a second jug. Shakira’s mother-in-law doused a tire, then popped the hood and soaked the engine. Shakira struck a match, and dropped it onto the tire.

From the house, they watched the sky turn ashen from the blaze. Before long, they heard the whirring of a helicopter, approaching from the south. “It’s coming for us!” her mother-in-law shouted. Shakira’s brother-in-law, who was staying with them, frantically gathered the children, but Shakira knew that it was too late. If we’re going to die, let’s die at home, she thought.

They threw themselves into a shallow trench in the back yard, the adults on top of the children. The earth shook violently, then the helicopter flew off. When they emerged, Shakira saw that the foreigners had targeted the burning vehicle, so that none of its parts would fall into enemy hands.

The women of Pan Killay came to congratulate Shakira; she was, as one woman put it, “a hero.” But she had difficulty mustering any pride, only relief. “I was thinking that they would not come here anymore,” she said. “And we would have peace.”

In 2008, the U.S. Marines deployed to Sangin, reinforcing American Special Forces and U.K. soldiers. Britain’s forces were beleaguered—a third of its casualties in Afghanistan would occur in Sangin, leading some soldiers to dub the mission “Sangingrad.” Nilofar, now eight, could intuit the rhythms of wartime. She would ask Shakira, “When are we going to Auntie Farzana’s house?” Farzana lived in the desert.

But the chaos wasn’t always predictable: one afternoon, the foreigners again appeared before anyone could flee, and the family rushed into the back-yard trench. A few doors down, the wife and children of the late Abdul Salam did the same, but a mortar killed his fifteen-year-old daughter, Bor Jana.

Both sides of the war did make efforts to avoid civilian deaths. In addition to issuing warnings to evacuate, the Taliban kept villagers informed about which areas were seeded with improvised explosive devices, and closed roads to civilian traffic when targeting convoys. The coalition deployed laser-guided bombs, used loudspeakers to warn villagers of fighting, and dispatched helicopters ahead of battle. “They would drop leaflets saying, ‘Stay in your homes! Save yourselves!’ ” Shakira recalled. In a war waged in mud-walled warrens teeming with life, however, nowhere was truly safe, and an extraordinary number of civilians died. Sometimes, such casualties sparked widespread condemnation, as when a nato rocket struck a crowd of villagers in Sangin in 2010, killing fifty-two. But the vast majority of incidents involved one or two deaths—anonymous lives that were never reported on, never recorded by official organizations, and therefore never counted as part of the war’s civilian toll.

In this way, Shakira’s tragedies mounted. There was Muhammad, a fifteen-year-old cousin: he was killed by a buzzbuzzak, a drone, while riding his motorcycle through the village with a friend. “That sound was everywhere,” Shakira recalled. “When we heard it, the children would start to cry, and I could not console them.”

Muhammad Wali, an adult cousin: Villagers were instructed by coalition forces to stay indoors for three days as they conducted an operation, but after the second day drinking water had been depleted and Wali was forced to venture out. He was shot.

Khan Muhammad, a seven-year-old cousin: His family was fleeing a clash by car when it mistakenly neared a coalition position; the car was strafed, killing him.

Bor Agha, a twelve-year-old cousin: He was taking an evening walk when he was killed by fire from an Afghan National Police base. The next morning, his father visited the base, in shock and looking for answers, and was told that the boy had been warned before not to stray near the installation. “Their commander gave the order to target him,” his father recalled.

Amanullah, a sixteen-year-old cousin: He was working the land when he was targeted by an Afghan Army sniper. No one provided an explanation, and the family was too afraid to approach the Army base and ask.

Ahmed, an adult cousin: After a long day in the fields, he was headed home, carrying a hot plate, when he was struck down by coalition forces. The family believes that the foreigners mistook the hot plate for an I.E.D.

Niamatullah, Ahmed’s brother: He was harvesting opium when a firefight broke out nearby; as he tried to flee, he was gunned down by a buzzbuzzak.

Gul Ahmed, an uncle of Shakira’s husband: He wanted to get a head start on his day, so he asked his sons to bring his breakfast to the fields. When they arrived, they found his body. Witnesses said that he’d encountered a coalition patrol. The soldiers “left him here, like an animal,” Shakira said.

Entire branches of Shakira’s family tree, from the uncles who used to tell her stories to the cousins who played with her in the caves, vanished. In all, she lost sixteen family members. I wondered if it was the same for other families in Pan Killay. I sampled a dozen households at random in the village, and made similar inquiries in other villages, to insure that Pan Killay was no outlier. For each family, I documented the names of the dead, cross-checking cases with death certificates and eyewitness testimony. On average, I found, each family lost ten to twelve civilians in what locals call the American War.

This scale of suffering was unknown in a bustling metropolis like Kabul, where citizens enjoyed relative security. But in countryside enclaves like Sangin the ceaseless killings of civilians led many Afghans to gravitate toward the Taliban. By 2010, many households in Ishaqzai villages had sons in the Taliban, most of whom had joined simply to protect themselves or to take revenge; the movement was more thoroughly integrated into Sangin life than it had been in the nineties. Now, when Shakira and her friends discussed the Taliban, they were discussing their own friends, neighbors, and loved ones.

Some British officers on the ground grew concerned that the U.S. was killing too many civilians, and unsuccessfully lobbied to have American Special Forces removed from the area. Instead, troops from around the world poured into Helmand, including Australians, Canadians, and Danes. But villagers couldn’t tell the difference—to them, the occupiers were simply “Americans.” Pazaro, the woman from a nearby village, recalled, “There were two types of people—one with black faces and one with pink faces. When we see them, we get terrified.” The coalition portrayed locals as hungering for liberation from the Taliban, but a classified intelligence report from 2011 described community perceptions of coalition forces as “unfavorable,” with villagers warning that, if the coalition “did not leave the area, the local nationals would be forced to evacuate.”

In response, the coalition shifted to the hearts-and-minds strategy of counter-insurgency. But the foreigners’ efforts to embed among the population could be crude: they often occupied houses, only further exposing villagers to crossfire. “They were coming by force, without getting permission from us,” Pashtana, a woman from another Sangin village, told me. “They sometimes broke into our house, broke all the windows, and stayed the whole night. We would have to flee, in case the Taliban fired on them.” Marzia, a woman from Pan Killay, recalled, “The Taliban would fire a few shots, but the Americans would respond with mortars.” One mortar slammed into her mother-in-law’s house. She survived, Marzia said, but had since “lost control of herself”—always “shouting at things we can’t see, at ghosts.”

With the hearts-and-minds approach floundering, some nato officials tried to persuade Taliban commanders to flip. In 2010, a group of Sangin Taliban commanders, liaising with the British, promised to switch sides in return for assistance to local communities. But, when the Taliban leaders met to hammer out their end of the deal, U.S. Special Operations Forces—acting independently—bombed the gathering, killing the top Taliban figure behind the peace overture.

The Marines finally quit Sangin in 2014; the Afghan Army held its ground for three years, until the Taliban had brought most of the valley under its control. The U.S. airlifted Afghan Army troops out and razed many government compounds—leaving, as a nato statement described approvingly, only “rubble and dirt.” The Sangin market had been obliterated in this way. When Shakira first saw the ruined shops, she told her husband, “They left nothing for us.”

Still, a sense of optimism took hold in Pan Killay. Shakira’s husband slaughtered a sheep to celebrate the end of the war, and the family discussed renovating the garden. Her mother-in-law spoke of the days before the Russians and the Americans, when families picnicked along the canal, men stretched out in the shade of peach trees, and women dozed on rooftops under the stars.

But in 2019, as the U.S. was holding talks with Taliban leaders in Doha, Qatar, the Afghan government and American forces moved jointly on Sangin one last time. That January, they launched perhaps the most devastating assault that the valley witnessed in the entire war. Shakira and other villagers fled for the desert, but not everyone could escape. Ahmed Noor Mohammad, who owned a pay-phone business, decided to wait to evacuate, because his twin sons were ill. His family went to bed to the sound of distant artillery. That night, an American bomb slammed into the room where the twin boys were sleeping, killing them. A second bomb hit an adjacent room, killing Mohammad’s father and many others, eight of them children.

The next day, at the funeral, another air strike killed six mourners. In a nearby village, a gunship struck down three children. The following day, four more children were shot dead. Elsewhere in Sangin, an air strike hit an Islamic school, killing a child. A week later, twelve guests at a wedding were killed in an air raid.

After the bombing, Mohammad’s brother travelled to Kandahar to report the massacres to the United Nations and to the Afghan government. When no justice was forthcoming, he joined the Taliban.

On the strength of a seemingly endless supply of recruits, the Taliban had no difficulty outlasting the coalition. But, though the insurgency has finally brought peace to the Afghan countryside, it is a peace of desolation: many villages are in ruins. Reconstruction will be a challenge, but a bigger trial will be to exorcise memories of the past two decades. “My daughter wakes up screaming that the Americans are coming,” Pazaro said. “We have to keep talking to her softly, and tell her, ‘No, no, they won’t come back.’ ”

The Taliban call their domain the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, and claim that, once the foreigners are gone, they will preside over an era of tranquil stability. As the Afghan government crumbled this summer, I travelled through Helmand Province—the Emirate’s de-facto capital—to see what a post-American Afghanistan might look like.

I departed from Lashkar Gah, which remained under government control. At the outskirts stood a squat cement building with an Afghan-government flag—beyond this checkpoint, Kabul’s authority vanished. A pickup idled nearby; piled into the cargo bed were half a dozen members of the sangorian, a feared militia in the pay of the Afghan intelligence agency, which was backed by the C.I.A. Two of the fighters appeared no older than twelve.

I was with two locals in a beat-up Corolla, and we slipped past the checkpoint without notice. Soon, we were in a treeless horizon of baked earth, with virtually no road beneath us. We passed abandoned outposts of the Afghan Army and Police that had been built by the Americans and the Brits. Beyond them loomed a series of circular mud fortifications, with a lone Taliban sniper splayed on his stomach. White flags fluttered behind him, announcing the gateway to the Islamic Emirate.

The most striking difference between Taliban country and the world we’d left behind was the dearth of gunmen. In Afghanistan, I’d grown accustomed to kohl-eyed policemen in baggy trousers, militiamen in balaclavas, intelligence agents inspecting cars. Yet we rarely crossed a Taliban checkpoint, and when we did the fighters desultorily examined the car. “Everyone is afraid of the Taliban,” my driver said, laughing. “The checkpoints are in our hearts.”

If people feared their new rulers, they also fraternized with them. Here and there, groups of villagers sat under roadside trellises, sipping tea with Talibs. The country opened up as we jounced along a dirt road in rural Sangin. In the canal, boys were having swimming races; village men and Taliban were dipping their feet into the turquoise water. We passed green cropland and canopies of fruit trees. Groups of women walked along a market road, and two girls skipped in rumpled frocks.

We approached Gereshk, then under government authority. Because the town was the most lucrative toll-collection point in the region, it was said that whoever held it controlled all of Helmand. The Taliban had launched an assault, and the thuds of artillery resounded across the plain. A stream of families, their donkeys laboring under the weight of giant bundles, were escaping what they said were air strikes. By the roadside, a woman in a powder-blue burqa stood with a wheelbarrow; inside was a wrapped body. Some Taliban were gathered on a hilltop, lowering a fallen comrade into a grave.

I met Wakil, a bespectacled Taliban commander. Like many fighters I’d encountered, he came from a line of farmers, had studied a few years in seminary, and had lost dozens of relatives to Amir Dado, the Ninety-third Division, and the Americans. He discussed the calamities visited on his family without rancor, as if the American War were the natural order of things. Thirty years old, he’d attained his rank after an older brother, a Taliban commander, died in battle. He’d hardly ever left Helmand, and his face lit up with wonder at the thought of capturing Gereshk, a town that he’d lived within miles of, but had not been able to visit for twenty years. “Forget your writing,” he laughed as I scribbled notes. “Come watch me take the city!” Tracking a helicopter gliding across the horizon, I declined. He raced off. An hour later, an image popped up on my phone of Wakil pulling down a poster of a government figure linked to the Ninety-third Division. Gereshk had fallen.

At the house of the Taliban district governor, a group of Talibs sat eating okra and naan, donated by the village. I asked them about their plans for when the war was over. Most said that they’d return to farming, or pursue religious education. I’d flown to Afghanistan from Iraq, a fact that impressed Hamid, a young commander. He said that he dreamed of seeing the Babylonian ruins, and asked, “Do you think, when this is over, they’ll give me a visa?”

It was clear that the Taliban are divided about what happens next. During my visit, dozens of members from different parts of Afghanistan offered strikingly contrasting visions for their Emirate. Politically minded Talibs who have lived abroad and maintain homes in Doha or Pakistan told me—perhaps with calculation—that they had a more cosmopolitan outlook than before. A scholar who’d spent much of the past two decades shuttling between Helmand and Pakistan said, “There were many mistakes we made in the nineties. Back then, we didn’t know about human rights, education, politics—we just took everything by power. But now we understand.” In the scholar’s rosy scenario, the Taliban will share ministries with former enemies, girls will attend school, and women will work “shoulder to shoulder” with men.

Yet in Helmand it was hard to find this kind of Talib. More typical was Hamdullah, a narrow-faced commander who lost a dozen family members in the American War, and has measured his life by weddings, funerals, and battles. He said that his community had suffered too grievously to ever share power, and that the maelstrom of the previous twenty years offered only one solution: the status quo ante. He told me, with pride, that he planned to join the Taliban’s march to Kabul, a city he’d never seen. He guessed that he’d arrive there in mid-August.

On the most sensitive question in village life—women’s rights—men like him have not budged. In many parts of rural Helmand, women are barred from visiting the market. When a Sangin woman recently bought cookies for her children at the bazaar, the Taliban beat her, her husband, and the shopkeeper. Taliban members told me that they planned to allow girls to attend madrassas, but only until puberty. As before, women would be prohibited from employment, except for midwifery. Pazaro said, ruefully, “They haven’t changed at all.”

Travelling through Helmand, I could hardly see any signs of the Taliban as a state. Unlike other rebel movements, the Taliban had provided practically no reconstruction, no social services beyond its harsh tribunals. It brooks no opposition: in Pan Killay, the Taliban executed a villager named Shaista Gul after learning that he’d offered bread to members of the Afghan Army. Nevertheless, many Helmandis seemed to prefer Taliban rule—including the women I interviewed. It was as if the movement had won only by default, through the abject failures of its opponents. To locals, life under the coalition forces and their Afghan allies was pure hazard; even drinking tea in a sunlit field, or driving to your sister’s wedding, was a potentially deadly gamble. What the Taliban offered over their rivals was a simple bargain: Obey us, and we will not kill you.

This grim calculus hovered over every conversation I had with villagers. In the hamlet of Yakh Chal, I came upon the ruins of an Afghan Army outpost that had recently been overrun by the Taliban. All that remained were mounds of scrap metal, cords, hot plates, gravel. The next morning, villagers descended on the outpost, scavenging for something to sell. Abdul Rahman, a farmer, was rooting through the refuse with his young son when an Afghan Army gunship appeared on the horizon. It was flying so low, he recalled, that “even Kalashnikovs could fire on it.” But there were no Taliban around, only civilians. The gunship fired, and villagers began falling right and left. It then looped back, continuing to attack. “There were many bodies on the ground, bleeding and moaning,” another witness said. “Many small children.” According to villagers, at least fifty civilians were killed.

Later, I spoke on the phone with an Afghan Army helicopter pilot who had just relieved the one who attacked the outpost. He told me, “I asked the crew why they did this, and they said, ‘We knew they were civilians, but Camp Bastion’ ”—a former British base that had been handed over to the Afghans—“ ‘gave orders to kill them all.’ ” As we spoke, Afghan Army helicopters were firing upon the crowded central market in Gereshk, killing scores of civilians. An official with an international organization based in Helmand said, “When the government forces lose an area, they are taking revenge on the civilians.” The helicopter pilot acknowledged this, adding, “We are doing it on the order of Sami Sadat.”

General Sami Sadat headed one of the seven corps of the Afghan Army. Unlike the Amir Dado generation of strongmen, who were provincial and illiterate, Sadat obtained a master’s degree in strategic management and leadership from a school in the U.K. and studied at the nato Military Academy, in Munich. He held his military position while also being the C.E.O. of Blue Sea Logistics, a Kabul-based corporation that supplied anti-Taliban forces with everything from helicopter parts to armored tactical vehicles. During my visit to Helmand, Blackhawks under his command were committing massacres almost daily: twelve Afghans were killed while scavenging scrap metal at a former base outside Sangin; forty were killed in an almost identical incident at the Army’s abandoned Camp Walid; twenty people, most of them women and children, were killed by air strikes on the Gereshk bazaar; Afghan soldiers who were being held prisoner by the Taliban at a power station were targeted and killed by their own comrades in an air strike. (Sadat declined repeated requests for comment.)

The day before the massacre at the Yakh Chal outpost, CNN aired an interview with General Sadat. “Helmand is beautiful—if it’s peaceful, tourism can come,” he said. His soldiers had high morale, he explained, and were confident of defeating the Taliban. The anchor appeared relieved. “You seem very optimistic,” she said. “That’s reassuring to hear.”

I showed the interview to Mohammed Wali, a pushcart vender in a village near Lashkar Gah. A few days after the Yakh Chal massacre, government militias in his area surrendered to the Taliban. General Sadat’s Blackhawks began attacking houses, seemingly at random. They fired on Wali’s house, and his daughter was struck in the head by shrapnel and died. His brother rushed into the yard, holding the girl’s limp body up at the helicopters, shouting, “We’re civilians!” The choppers killed him and Wali’s son. His wife lost her leg, and another daughter is in a coma. As Wali watched the CNN clip, he sobbed. “Why are they doing this?” he asked. “Are they mocking us?”

In the course of a few hours in 2006, the Taliban killed thirty-two friends and relatives of Amir Dado, including his son. Three years later, they killed the warlord himself—who by then had joined parliament—in a roadside blast. The orchestrator of the assassination hailed from Pan Killay. In one light, the attack is the mark of a fundamentalist insurgency battling an internationally recognized government; in another, a campaign of revenge by impoverished villagers against their former tormentor; or a salvo in a long-simmering tribal war; or a hit by a drug cartel against a rival enterprise. All these readings are probably true, simultaneously. What’s clear is that the U.S. did not attempt to settle such divides and build durable, inclusive institutions; instead, it intervened in a civil war, supporting one side against the other. As a result, like the Soviets, the Americans effectively created two Afghanistans: one mired in endless conflict, the other prosperous and hopeful.

It is the hopeful Afghanistan that’s now under threat, after Taliban fighters marched into Kabul in mid-August—just as Hamdullah predicted. Thousands of Afghans have spent the past few weeks desperately trying to reach the Kabul airport, sensing that the Americans’ frenzied evacuation may be their last chance at a better life. “Bro, you’ve got to help me,” the helicopter pilot I’d spoken with earlier pleaded over the phone. At the time, he was fighting crowds to get within sight of the airport gate; when the wheels of the last U.S. aircraft pulled off the runway, he was left behind. His boss, Sami Sadat, reportedly escaped to the U.K.

Until recently, the Kabul that Sadat fled often felt like a different country, even a different century, from Sangin. The capital had become a city of hillside lights, shimmering wedding halls, and neon billboards that was joyously crowded with women: mothers browsed markets, girls walked in pairs from school, police officers patrolled in hijabs, office workers carried designer handbags. The gains these women experienced during the American War—and have now lost—are staggering, and hard to fathom when considered against the austere hamlets of Helmand: the Afghan parliament had a proportion of women similar to that of the U.S. Congress, and about a quarter of university students were female. Thousands of women in Kabul are understandably terrified that the Taliban have not evolved. In late August, I spoke by phone to a dermatologist who was bunkered in her home. She has studied in multiple countries, and runs a large clinic employing a dozen women. “I’ve worked too hard to get here,” she told me. “I studied too long, I made my own business, I created my own clinic. This was my life’s dream.” She had not stepped outdoors in two weeks.

The Taliban takeover has restored order to the conservative countryside while plunging the comparatively liberal streets of Kabul into fear and hopelessness. This reversal of fates brings to light the unspoken premise of the past two decades: if U.S. troops kept battling the Taliban in the countryside, then life in the cities could blossom. This may have been a sustainable project—the Taliban were unable to capture cities in the face of U.S. airpower. But was it just? Can the rights of one community depend, in perpetuity, on the deprivation of rights in another? In Sangin, whenever I brought up the question of gender, village women reacted with derision. “They are giving rights to Kabul women, and they are killing women here,” Pazaro said. “Is this justice?” Marzia, from Pan Killay, told me, “This is not ‘women’s rights’ when you are killing us, killing our brothers, killing our fathers.” Khalida, from a nearby village, said, “The Americans did not bring us any rights. They just came, fought, killed, and left.”

The women in Helmand disagree among themselves about what rights they should have. Some yearn for the old village rules to crumble—they wish to visit the market or to picnic by the canal without sparking innuendo or worse. Others cling to more traditional interpretations. “Women and men aren’t equal,” Shakira told me. “They are each made by God, and they each have their own role, their own strengths that the other doesn’t have.” More than once, as her husband lay in an opium stupor, she fantasized about leaving him. Yet Nilofar is coming of age, and a divorce could cast shame on the family, harming her prospects. Through friends, Shakira hears stories of dissolute cities filled with broken marriages and prostitution. “Too much freedom is dangerous, because people won’t know the limits,” she said.

All the women I met in Sangin, though, seemed to agree that their rights, whatever they might entail, cannot flow from the barrel of a gun—and that Afghan communities themselves must improve the conditions of women. Some villagers believe that they possess a powerful cultural resource to wage that struggle: Islam itself. “The Taliban are saying women cannot go outside, but there is actually no Islamic rule like this,” Pazaro told me. “As long as we are covered, we should be allowed.” I asked a leading Helmandi Taliban scholar where in Islam was it stipulated that women cannot go to the market or attend school. He admitted, somewhat chagrined, that this was not an actual Islamic injunction. “It’s the culture in the village, not Islam,” he said. “The people there have these beliefs about women, and we follow them.” Just as Islam offers fairer templates for marriage, divorce, and inheritance than many tribal and village norms, these women hope to marshal their faith—the shared language across their country’s many divides—to carve out greater freedoms.

Though Shakira hardly talks about it, she harbors such dreams herself. Through the decades of war, she continued to teach herself to read, and she is now working her way through a Pashto translation of the Quran, one sura at a time. “It gives me great comfort,” she said. She is teaching her youngest daughter the alphabet, and has a bold ambition: to gather her friends and demand that the men erect a girls’ school.

Even as Shakira contemplates moving Pan Killay forward, she is determined to remember its past. The village, she told me, has a cemetery that spreads across a few hilltops. There are no plaques, no flags, just piles of stones that glow red and pink in the evening sun. A pair of blank flagstones project from each grave, one marking the head, one the feet.

Shakira’s family visits every week, and she points to the mounds where her grandfather lies, where her cousins lie, because she doesn’t want her children to forget. They tie scarves on tree branches to attract blessings, and pray to those departed. They spend hours amid a sacred geography of stones, shrubs, and streams, and Shakira feels renewed.

Shortly before the Americans left, they dynamited her house, apparently in response to the Taliban’s firing a grenade nearby. With two rooms still standing, the house is half inhabitable, half destroyed, much like Afghanistan itself. She told me that she won’t mind the missing kitchen, or the gaping hole where the pantry once stood. Instead, she chooses to see a village in rebirth. Shakira is sure that a freshly paved road will soon run past the house, the macadam sizzling hot on summer days. The only birds in the sky will be the kind with feathers. Nilofar will be married, and her children will walk along the canal to school. The girls will have plastic dolls, with hair that they can brush. Shakira will own a machine that can wash clothes. Her husband will get clean, he will acknowledge his failings, he will tell his family that he loves them more than anything. They will visit Kabul, and stand in the shadow of giant glass buildings. “I have to believe,” she said. “Otherwise, what was it all for?” ♦

— Published in the print edition of the September 13, 2021, issue.

— Anand Gopal, the author of “No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes,” is writing a book on the Arab revolutions.

0 notes

Text

Top 7 Teen Movies

When you grow up, your heart dies - or so they say. Here's the proof: Heathers Juno, critic of The Guardian and Observer select the 10 best movies for teenagers. Blackboard Jungle

Under the name "Evan Hunter", also known as a crime writer Ed McBain - Blackboard Jungle the early age of the labeled teen offender - it was based on his own experience as a teacher in the Bronx. In London movie Brooks attracted crowds of Stuffed Boys, cut theater seats, danced in the aisles and actually started a riot. The reason for this so shocking behavior was not so much the content of the film, which is now a sober 12 rating, but achieved due to the use of Bill Haley and the early rock'n'roll comets, Rock Around the Clock, who played in polarization . Today is the least shocking aspect of a crime-thrusting film with a knife, drugs and even rape in the state school system, but at the time it was a touchstone for disgruntled young people, regardless of whether Haley was a white musician traveler in Its 30 years and the music has already been a year old. Almost 60 years later, he still has a hit, with Richard Dadier Glenn Ford (first called to enable students to call the Jive to talk to him "Daddy-O") struggle to control his students in the North fiction manual school. Others try and fail, such as the unfortunate Mr. Edwards, whose valuable 78s are crushed by his class consists of an act of symbolic and even disturbing rebellion, but I hope that as African Americans Gregory Miller, what eventually patriotic authority Dadier replied. But for all its war morality, Vic Morrow, the evil Artie West, is the true anti-hero of the film, dressed in leather and meets the logical heir Wild One, Marlon Brando, two years before. Superbad

With certified hits The 40 Year Old Virgin and Knocked Up, the Judd Apatow Express was already rolling at full speed when Superbad, directed a comedy in the younger audience, appeared on the movie screens. Co-written by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg (designated the main characters to be), and produced by Apatow, he liked this movie more with a hoarse Partycrowd. The image is dominated by three young actors who were not then the stars they are now. Evan (Michael Cera), Seth (Jonah Hill) and Fogell (Christopher Mintz-Plasse) are high school graduates getting ready for a final party before college. Evan and Seth no longer see each other when the first outing to the prestigious Dartmouth while the latter attended a public university; Seth Groll scattered around the action, but now he's eyeing sex. If he offers through the object of his alcohol affection to a party held so the numbers he is sleeping with her. This is where the drippy Fogell enters: having a fake identity secured mis-adapted under the pseudonym of McLovin, is the key is to plan Seth. With its notes and 24-hour melancholy, the film takes a similar American Graffiti and Dazed and Confused terrain, but is distinguished by a Post-Porky Sensitivity Hallows celebrates simultaneously pre-PC smuttiness. Much of the humor derives from the assessments of the chauvinistic Sex by inexperienced hero. (Adult, I no longer sophisticated. A Rogen police admits that police work is nothing like the serious coroner CSI procedural having been carried out, can be expected. "When I joined the force," he laments, "I semen believed oftentimes "). Goodwill mocking the experts, the details of the accompaniment and direction of Greg Mottola exuberant makes the image almost irresistible, although the pace of broad-fashion and humor is as sexist as a hope for the production of Apatow Kids

No kids at school wisecracking here. In fact there is no mention of the school. Not that many jokes, either come to think of it. Instead, Larry Clark's raw, Drama bracing reminds us securely and artificially that most movies are teenagers. The boys were dangerous: an open honest representation of what modern teenagers actually do (those who grew up in New York, anyway). It was a heavy blow to the chops of a complacent society, who thought she had made all the rebels in the 1950s, and was convicted by demonstrators and politicians. But as The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause, the film showed a terrible chasm between generations of young and old. The last only demographic number in history. While they work, their children are drunk, they are stoned, fun, fight, steal them and more sex than they did, yet clumsy, insecure and people who do not particularly like. Worse than all this danger sign, but the general lack of concern or compassion for the characters, especially Leo Fitzpatrick's anti-hero is Telly's terrible reckless pursuit of "de-virginise" younger girls and neglected joint has its successes. With the spectrum of AIDS lurking in the shadows, a happy ending is even more in the distance. But there is nothing particularly sensational about the way children have gone through these adolescent lives. The treatment is more like a documentary: on the wall with the camera (which incidentally by the indecent sometimes), the actual sites of the road, unstructured scenes and dialogue really conversation - the latter in Harmony Korine, largely through Of the internal work of a writing, as he was 19 years old. That's the thing, do not get the kids credit for the season: it's done. It is a work of fiction, but the benefits are so little is known, is not included as an "actor", although many of the players followed the decent career, such as Fitzpatrick, Chloe Sevigny, Rosario Dawson and Korine. In short, the will of a job done a little too well. 10 Things I Hate About You

The philosophy behind this lively teen comedy looks like the Shrew the Clueless made Emma do. That is, take the skeleton of a literary classic and dressed in the threads of high school. Although the film Clueless is not, still quite blinding Bobby. Shakespeare's transplant into a youthful atmosphere of the United States in recent times is the least successful part of it: It is not something that a strident touch in the plot, in which a young man told his father that he would not allow graduation date, until the Abrasive ground older sister Kat (Julia Stiles). This sets up a system of younger brother suitors born of a legal soil, Patrick (Heath Ledger), is paid uncontrollably seduce Kat. But that's a small detail. To which we respond in 10 things are visual and verbal, energetic rhythm and charismatic performances: Stiles and the last Ledger may be known for more intense films, but it is doubtful that we do not always get more on the screen than I do here. Writer Karen McCullah Lutz and Kirsten Smith, keeping things bright will not character for a long time without toxic replica or a sharp zinger their lips anymore. If someone has hit a dry spot, there is always a language to see. "I know you can be overwhelmed and dominated" reflects a girl, "but can it alone" overwhelmed "? Everyone here is united and evoked by their idiosyncratic vocabulary, and the viewer is also enriched by phrases such as" (The brain area where the images are saved as desirable partner for stimulants) or a new definition for the word "backup." For the cast includes Joseph Gordon-Levitt and as the father of the Kat, the magnificent Larry Miller (who was an early contender for George Costanza's game at Seinfeld.) If the rhythm flags, still pick-me-ups like the wonderful accounting show karaoke with the zeal of Steve's early start Martin is held. Juno

Written by an ex-stripper and the issue of student pregnancy approaching - the downfall of all middle-class parents - Jason Reitman's film is a hilarious comedy, played well, that a star made night Ellen Page as the title character. Much if talked about its pro-life nuances in its release, but in reality the situation is Juno is something of a MacGuffin, a premise that a smart, wise to the world and its future can look 16 years. Juno begins with his heroine to realize that a baby will have, the result of a loose ball with his best friend Paulie Bleeker (Michael Cera, in his own weediest). Instead of finishing, Juno decides the child for adoption to give attributes to the Loring (Jason Bateman and Jennifer Garner), a couple who seem to be in tune - especially participate their love for indie rock and horror movies (although their tastes are quite Early, even by today's standards). The latter is twee and well marked, but what Juno is refreshing, without dismantling the smart edge. In the end, she is certainly older and wiser, but what Juno learns more, do, prepare for disappointment: the adult world not Disney World of complexity is what he seems to think. The use of indie rock still dark have hampered its potential as a mainstream success, but now that only its charm is given lo-fi and in a sense, it is probably useful because Juno really is not aligned world, only those who think Who knew everything grew and learned the hard way that even if they know everything, nobody likes a smartass. Clueless

"As if!" — "I totally paused!" — "Minor ducats…" — "Let's do a lap before we commit to a location!" — "I was surfing the crimson wave!" — "Did my hair get flat?"If Clueless was published in 1995, it was not just sensational and intelligent fun - carefree, the opposite of its title was. Insinuating indirect, clever and funny: writers director Amy Heckerling and seemed to have invented a new culture of the teen-pop language. It was as vivid and colorful as his remarkable movie heroine-keeper: funnier and more romantic than any romcom. In the nineties, it was the hot topics issue. This film was a disgrace to all who, a funny and gracious tribute to Emma Jane Austen with nod to Shakespeare and Wilde. In Clueless, 19, Alicia Silverstone was the role of her life, unique style and comedy display ability, but never found after the race that everything seemed to promise. She plays Cher, the pampered, but basically good-hearted Princess: rich, popular, obsessed with fashion, but lonely and looking for love. Silverstone finds laughter as a teacher, and his voice in a sort of pitchy yodel pause in perplexing tones or complaint. Cher is best friend Dionne (Stacey Trace), but somewhat aggressive with his ex-strident Josh, whose mother was married to Cher's ferocious defender Mel, played by Dan Hedaya. However, could there be a spark between these two? Josh is a college student in liberal causes and Roar Mode "Rock Complaint". It is played by 26-year-old Paul Rudd, who immediately became a brand in Hollywood and sniper. Rudd's character began to mature and youthful Clueless. Get Cher decides what bad grades you have to do with getting your teachers in love, to sneakily two of them fall to each other, and if the east coast dorky girl named Tai appears, Cher makes a personal change "project ". Tai is very well played by Brittany Murphy, an up-and-comer talent who was bleak due to complications of dying in 2009 after an overdose of prescription drugs. The teen movie references to contemporary youth culture is always complicated with irony and melancholy if you look after almost 20 years. The terrible fate of Brittany Murphy is the saddest part of it. Clueless is strange to think that once the social networks. These people are ready and ready for the Internet and the digital revolution. There is a splendid view of the gag on Cher and Dionne talking uncomfortable on his large mobile phone. The recent film by Sofia Coppola, The Ring Bling is Clueless next generation. The difference is that the lean teenager Coppola really are clueless, white and selfish. There is a nice quality and idealistic Clueless comic that makes it so appealing. Cher and Dionne are the queens at their school, but not unpleasant, and according to their lights, they always want to do the right thing. Clueless is not characterized by a sign of "Bully" noticing a comeuppance ter. Mean Girls, the 2004 satirical film written by Tina Fey and Lindsay Lohan is very different. There's nothing new about bullying, of course, but I think it's interesting that Clueless appeared briefly to introduce snarky sites and reality farce at the center of pop culture. Clueless is a true classic: handsome, innocent fun. I envy people I have not yet seen. Pretty In Pink

The amazing ability to take advantage of John Hughes' teenage thrill, and then inexorably, pack it in a commercial way, has never been better employed here. This is empathy for his films, but also the most outrageous Eighties-tastic. A universal heart-tugger and retro bible style. It's a win-win. There is an old story - the poor Cinderella rich Prince Charming meets, and agonize all the way to the climatic ball, sorry, dance - but the full spectrum of teen angst is here: worry about what your colleagues think; Believing secretly tell your best friend and courage; They worry that you are very poor; Concern for parents; Worry that the sleeve of your vintage tuxedo has not rolled high enough. Hughes takes everything seriously and it takes time to build his characters. Andie knows where Molly Ringwald is coming from. We have to see him at home, and how embarrassing it is, we hung in his room, we saw the status of his single father (playing Harry Dean Stanton). This does not want to take the Ringwald natural wonderful power. Their blend of forward and fragility is the compelling effort. If you apply your lipstick or calls snobbery Andrew McCarthy, we are all the way with it. And Duckie John Cryer is the strangest of the male characters: the friendly and friendly clown who does not stay with the girl, although a better and better dressed society. The latter (especially the requirements of the modified screening tests) feels a bit like a cop-out, but could be read as a commentary on the bittersweet novel against pragmatism. If the story you do not start with Pretty in Pink, style it be. The film is worth looking at the costume changes alone, the respective boss Ringwald, Annie Potts, who travels from the fetish-punk in the 50's hive, Madonna-like material girl Debbie Harry New Wave. Serious art direction now makes the film look like a time capsule intentionally, filled with so many fashions, posters, records and decorative objects as they thought they could escape. And do not forget the soundtrack: Psychedelic Furs, OMD, Echo and the Bunnymen, New Order, The Smiths, uh, a cover by Nik Kershaw. Was each teen movie better?

via Blogger http://ift.tt/2lSTGKE

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

141. Elly Thomas

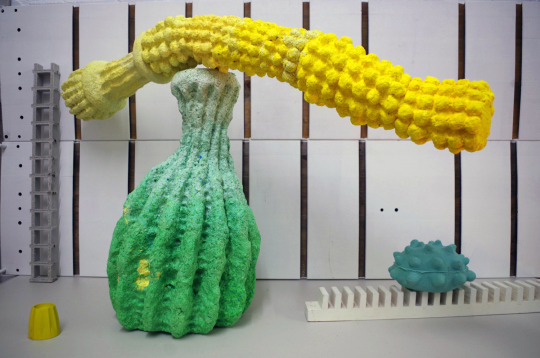

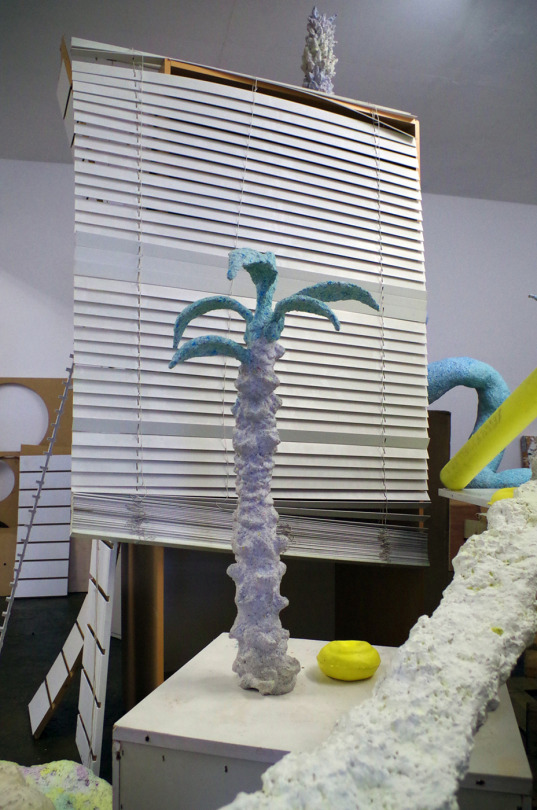

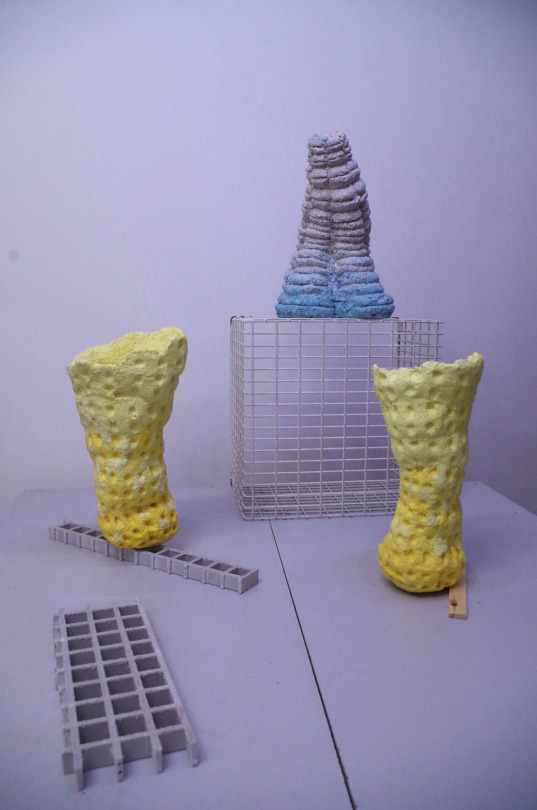

Elly Thomas, ‘Czar’, 2017. Papier-mâché, silicone and found objects. Image courtesy of the artist.

Elly Thomas is an emerging artist who uses sculptural forms to navigate how childhood play can inform adult creative processes. Creating a series of forms, which are then combined into various improvised assemblages, Thomas uses these impermanent structures to explore animism and autonomy of objects. Having completed a PhD in 2013 at Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, where her thesis was titled ‘Play as Evolving Process in the Work of Eduardo Paolozzi, Philip Guston and Tony Oursler’, Elly is now a leading mind on Paolozzi and Guston’s practices and will soon be releasing a book with Routledge discussing their processes and output. Here, Thomas talks with Charlotte Barnard for Traction.

You create sculpture and drawings, which use childhood play as set of paradigms to inform adult creative practice. How did you come to be so interested in this line of enquiry?

It was while I was enjoying working with children on an art project that I began noticing parallels between the way the children spoke about their work and my own ongoing concerns. Namely, at its most basic, we were concerned with transforming matter into something that seemed animate, that seemed to have a life of its own beyond one’s control, much as the way one would think about one’s toys as a child. So not representing something, but inventing - regarding a drawing or sculpture almost as a living thing, as a thing in itself.

I thought perhaps this space for play continued into adult life. I didn’t need to pretend to be a child again. How could I? It would only produce some sort of faux naivety. Instead I wondered whether I could learn from the children in a way that could be applicable to my own ongoing concerns, through a focus on animism and its expression through play methods, processes and objectives (rather than aesthetics).