#as an experiment in furthering women's creative life after academia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

He had been speaking for a few minutes when a dark-haired, harried woman burst into the room. She was a bit older than most of the other students; she wore a low-cut blouse and visible makeup. Pretty, certainly, but a bit undone in some imperceptible way. The latecomer sashayed to the back of the classroom, her bangles clanging as she walked. A male student got up to offer her his seat, because the chairs were all taken. Once she settled into it, she removed a high-heeled shoe and a pack of cigarettes and proceeded to smoke, using the heel of the shoe as an ashtray. This woman was Anne Sexton.

Maggie Doherty, The Equivalents: A Story of Art, Female Friendship, and Liberation in the 1960s

#Maggie Doherty#The Equivalents#Anne Sexton#1960s#The he referred to was poet John Holmes#and the book is about the#Institute for Independent Study#created at#Radcliffe#as an experiment in furthering women's creative life after academia#Books 2024#My Post

0 notes

Text

What Needs to Have Mentally Strong and Its Concept of Life.

Meeting a powerful women that can make others people feels so strong, she transfers an energy to have better life in filling day to day. Just wondered how she can be a good leader and makes everyone absolutely love her as much as they love their self and coming back again with the question ” what makes her to be loved so deeply, and What makes the difference?”

maybe most of us will answer these questions by talking about the talent of top performers. He must be the smartest. She’s faster than everyone else on the team. He is a brilliant business strategist. but the answers are not closely on that above answers.

In fact, when you start looking into it, your talent and your intelligence don’t play nearly as big of a role as you might think. The research studies that I have found say that intelligence only accounts for 30% of your achievement — and that’s at the extreme upper end. What makes a bigger impact than talent or intelligence? Mental toughness.

Research is starting to reveal that your mental toughness — or “grit” as they call it — plays a more important role than anything else for achieving your goals in health, business, and life. That’s good news because you can’t do much about the genes you were born with, but you can do a lot to develop mental toughness.

Why is mental toughness so important? And how can you develop more of it?

Let’s talk about that now.

Mental Toughness and The United States Military

Each year, approximately 1,300 cadets join the entering class at the United States Military Academy, West Point. During their first summer on campus, cadets are required to complete a series of brutal tests. This summer initiation program is known internally as “Beast Barracks.”

In the words of researchers who have studied West Point cadets, “Beast Barracks is deliberately engineered to test the very limits of cadets’ physical, emotional, and mental capacities.”

You might imagine that the cadets who successfully complete Beast Barracks are bigger, stronger, or more intelligent than their peers. But Angela Duckworth, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, found something different when she began tracking the cadets.

Duckworth studies achievement, and more specifically, how your mental toughness, perseverance, and passion impact your ability to achieve goals. At West Point, she tracked a total of 2,441 cadets spread across two entering classes. She recorded their high school rank, SAT scores, Leadership Potential Score (which reflects participation in extracurricular activities), Physical Aptitude Exam (a standardized physical exercise evaluation), and Grit Scale (which measures perseverance and passion for long–term goals).

Here’s what she found out…

It wasn’t strength or smarts or leadership potential that accurately predicted whether or not a cadet would finish Beast Barracks. Instead, it was grit — the perseverance and passion to achieve long–term goals — that made the difference.

In fact, cadets who were one standard deviation higher on the Grit Scale were 60% more likely to finish Beast Barracks than their peers. It was mental toughness that predicted whether or not a cadet would be successful, not their talent, intelligence, or genetics.

When Is Mental Toughness Useful?

Duckworth’s research has revealed the importance of mental toughness in a variety of fields.

In addition to the West Point study, she discovered that…

Ivy League undergraduate students who had more grit also had higher GPAs than their peers — even though they had lower SAT scores and weren’t as “smart.”

When comparing two people who are the same age but have different levels of education, grit (and not intelligence) more accurately predicts which one will be better educated.

Competitors in the National Spelling Bee outperform their peers not because of IQ, but because of their grit and commitment to more consistent practice.

And it’s not just education where mental toughness and grit are useful. Duckworth and her colleagues heard similar stories when they started interviewing top performers in all fields…

Our hypothesis that grit is essential to high achievement evolved during interviews with professionals in investment banking, painting, journalism, academia, medicine, and law. Asked what quality distinguishes star performers in their respective fields, these individuals cited grit or a close synonym as often as talent. In fact, many were awed by the achievements of peers who did not at first seem as gifted as others but whose sustained commitment to their ambitions was exceptional. Likewise, many noted with surprise that prodigiously gifted peers did not end up in the upper echelons of their field.

—Angela Duckworth

You have probably seen evidence of this in your own experiences. Remember your friend who squandered their talent? How about that person on your team who squeezed the most out of their potential? Have you known someone who was set on accomplishing a goal, no matter how long it took?

You can read the whole research study here, but this is the bottom line:

In every area of life — from your education to your work to your health — it is your amount of grit, mental toughness, and perseverance that predicts your level of success more than any other factor we can find.

In other words, talent is overrated.

What Makes Someone Mentally Tough?

It’s great to talk about mental toughness, grit, and perseverance … but what do those things actually look like in the real world?

In a word, toughness and grit equal consistency.

Mentally tough athletes are more consistent than others. They don’t miss workouts. They don’t miss assignments. They always have their teammates back.

Mentally tough leaders are more consistent than their peers. They have a clear goal that they work towards each day. They don’t let short–term profits, negative feedback, or hectic schedules prevent them from continuing the march towards their vision. They make a habit of building up the people around them — not just once, but over and over and over again.

Mentally tough artists, writers, and employees deliver on a more consistent basis than most. They work on a schedule, not just when they feel motivated. They approach their work like a pro, not an amateur. They do the most important thing first and don’t shirk responsibilities.

The good news is that grit and perseverance can become your defining traits, regardless of the talent you were born with. You can become more consistent. You can develop superhuman levels of mental toughness.

How?

In my experience, these 3 strategies work well in the real world…

1. Define what mental toughness means for you.

For the West Point army cadets being mentally tough meant finishing an entire summer of Beast Barracks.

For you, it might be…

going one month without missing a workout

going one week without eating processed or packaged food

delivering your work ahead of schedule for two days in a row

meditating every morning this week

grinding out one extra rep on each set at the gym today

calling one friend to catch up every Saturday this month

spending one hour doing something creative every evening this week

Whatever it is, be clear about what you’re going after. Mental toughness is an abstract quality, but in the real world it’s tied to concrete actions. You can’t magically think your way to becoming mentally tough, you prove it to yourself by doing something in real life.

Which brings me to my second point…

2. Mental toughness is built through small physical wins.

You can’t become committed or consistent with a weak mind. How many workouts have you missed because your mind, not your body, told you you were tired? How many reps have you missed out on because your mind said, “Nine reps is enough. Don’t worry about the tenth.” Probably thousands for most people, including myself. And 99% are due to weakness of the mind, not the body.

—Drew Shamrock

So often we think that mental toughness is about how we respond to extreme situations. How did you perform in the championship game? Can you keep your life together while grieving the death of a family member? Did you bounce back after your business went bankrupt?

There’s no doubt that extreme situations test our courage, perseverance, and mental toughness … but what about everyday circumstances?

Mental toughness is like a muscle. It needs to be worked to grow and develop. If you haven’t pushed yourself in thousands of small ways, of course you’ll wilt when things get really difficult.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Choose to do the tenth rep when it would be easier to just do nine. Choose to create when it would be easier to consume. Choose to ask the extra question when it would be easier to accept. Prove to yourself — in a thousand tiny ways — that you have enough guts to get in the ring and do battle with life.

Mental toughness is built through small wins. It’s the individual choices that we make on a daily basis that build our “mental toughness muscle.” We all want mental strength, but you can’t think your way to it. It’s your physical actions that prove your mental fortitude.

3. Mental toughness is about your habits, not your motivation.

Motivation is fickle. Willpower comes and goes.

Mental toughness isn’t about getting an incredible dose of inspiration or courage. It’s about building the daily habits that allow you to stick to a schedule and overcome challenges and distractions over and over and over again.

Mentally tough people don’t have to be more courageous, more talented, or more intelligent — just more consistent. Mentally tough people develop systems that help them focus on the important stuff regardless of how many obstacles life puts in front of them. It’s their habits that form the foundation of their mental beliefs and ultimately set them apart.

I’ve written about this many times before. Here are the basic steps for building a new habit and links to further information on doing each step.

Start by building your identity.

Focus on small behaviors, not life–changing transformations.

Develop a routine that gets you going regardless of how motivated you feel.

Stick to the schedule and forget about the results.

When you slip up, get back on track as quickly as possible.

Mental toughness comes down to your habits. It’s about doing the things you know you’re supposed to do on a more consistent basis. It’s about your dedication to daily practice and your ability to stick to a schedule.

How Have You Developed Mental Toughness?

Our mission as a community is clear: we are looking to live healthy lives and make a difference in the world.

To that end, I see it as my responsibility to equip you with the best information, ideas, and strategies for living healthier, becoming happier, and making a bigger impact with your life and work.

But no matter what strategies we discuss, no matter what goals we set our sights on, no matter what vision we have for ourselves and the people around us … none of it can become a reality without mental toughness, perseverance, and grit.

When things get tough for most people, they find something easier to work on. When things get difficult for mentally tough people, they find a way to stay on schedule.

There will always be extreme moments that require incredible bouts of courage, resiliency, and grit … but for 95% of the circumstances in life, toughness simply comes down to being more consistent than most people

1 note

·

View note

Text

Writing Sample: MDIA417

MDIA417: Creative Industries and Cultural Labour. Final Research Project.

Precarity and Sexual Harassment in the Creative Workplace

Precarity drives sexism and sexual assault towards women in the workforce, particularly women starting out in their fields. This occurs in most industries, but is particularly acute in creative industries. This research essay seeks to prove this thesis, through a critical analysis of both scholarly literature and popular media coverage incorporating conceptions of how and why precarity occurs and its impact and feminist theory of gendered power structures, with a special focus on how precarity particularly affects women. It will also make use of a case study of the #MeToo/Times Up movement, to display how precarity in the workforce and in individual’s private lives drives womens experiences of gendered relations of power and sexual harassment in the workplace, and explore how it may be negated in the future.

Workplace sexual harassment: an overview

The reported incidences of workplace sexual harassment by gender vary from study to study, but most conclude that women experience it in greater numbers. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) contends that between 25% and 85% of American women will experience workplace sexual harassment (Feldblum & Lipnic). It is difficult to more precisely gauge how many women experience sexual harassment in the workplace as many victims do not report instances of harassment, and my paper seeks to expand on the driving forces behind this. Women in precarious employment are more likely to be subject to a specific form of exploitation: sexual harassment by their colleagues, employers or more senior figures in their industry. This is neither wholly due to the gender or economic hierarchies present in the workplace, but a complex interplay between the two (Crain). As we have seen from the explosion of the #MeToo movement, many women in the creative industries who have been subject to sexual harassment earlier in their careers do not feel comfortable speaking out about it until they were firmly established in their fields. The Times Up legal fund for victims of sexual harassment in the workplace has indicated that the greatest represented industry in applications to the fund is the arts industry, from which 9% of the total applications are sourced (Corkery).

Literature Review

Precarity in the workforce

The creative industries are situated within the service and knowledge industry, and can most broadly be defined as including the arts and culture, entertainment and copyright, and information services industries (Flew). Workers in the creative industries exemplify precarity in the modern work force. Creative work is highly insecure, often low paid, and very competitive, with workers engaging in multiple consecutive and concurrent contract and temporary gigs, rather than permanent employment (Gill & Pratt). Working multiple jobs may mean longer working hours, but actual paid labour is not the only drain on creative workers time. Depending on which part of the creative industries one works in, staying up to date with industry advances and networking is crucial and often takes place out of hours, leading to more of the creative workers time being eaten up without financial recompense. Such insecure working conditions drive exploitation of workers who are then less likely to speak out against their exploitation for myriad reasons. Autonomous workers in temporary or contract work are used to constantly managing themselves and the jobs they may work in the future on top of their current jobs. This self management may lead workers to feel it is not worth risking their long term work prospects for only a short period of potentially better working conditions, fearing ruining their chances of having their contracts renewed in a competitive industry. Workers who have yet to establish themselves in the industry and ‘precogs’ -cognitive workers engaged in precarious labour conditions- (de Peuter) are willing to put up with highly exploitative working conditions, even working for free, rationalising their undervalued labour through the belief that it is a prerequisite to better working opportunities in the future.

Precarity at home

The precariat does not only experience precarity in their job (or jobs) but in their home life too. The chronic income instability that leads on from employment insecurity has several ill effects on an individual’s personal life, such as unstable living situations, food insecurity, and the associated health issues brought on by these conditions (Cochrane et al.) Insecure employment may affect the precariat’s ability to pay for housing, which is compounded in the creative industry whose workers are often concentrated in cities such as Los Angeles, San Fransisco, New York, and London (or Wellington!), cities that trend towards higher than average house prices and rental costs. This concentration is largely driven by local policy and the rise of the ‘creative city’ as regions look towards the creative industries as the logical next step after industrial and managerial capitalism to drive economic growth and competitiveness. (Florida, in Flew, Oakley). Much of the work in the creative industries can be highly transitory in nature (Screen Women’s Action Group, Anonymous in Curtin & Sanson), which leads workers to ‘follow the money’ rather than establishing a complete life in any one place. Following productions in this way may also erode worker’s work-life balance further, as not having a defined ‘home base’ of sorts means there is less of a distinction between work and home.

Precarity crossover and the social factory

Other autonomist Marxist scholars contest that precarity is not defined by its structuring of the worker’s work life or personal life, but as a mechanism of control that causes the two to bleed together, “requiring workers not to work all the time but to be constantly available for work” (Hardt & Negri, p. 146). Labour is no longer organised around a central factory, but dispersed out into society (Hardt & Negri, in Gill & Pratt). In the creative industries, informal networking outside of ‘standard’ working hours (if such a thing can exist in the social factory) may be perceived as necessary by precarious workers to survive in their chosen career path (Gill & Pratt). In relation to sexual harassment, the perceived compulsivity of informal networking meetings that often take place in settings traditionally not associated as work settings, such as restaurants and bars, by precarious female workers may make them feel obligated to put themselves in unsafe situations for the hopeful benefit of their careers. From the testimonies of Harvey Weinstein’s victims, this seemed to be his modus operandi (Farrow). New Zealand’s Screen Women’s Action Group identified “[t]he fluidity and merging of social events with work” (Screen Women’s Action Group, p. 2) as contributing factors to the prevalence of sexual harassment unique to the screen industry, listing events such as wrap parties, publicity tours, film festivals, and development work happening in private homes as examples.

Precarity and reporting of sexual harassment

The #MeToo movement has somewhat been characterised in popular media by well known and established actresses speaking out about sexual harassment and even assault they had experienced several years or decades ago, largely because the individuals whose stories are most heard are those with the platforms and agency to ensure they are heard. The challenge for #MeToo as it continues to grow is how the movement will enable the voices of those without access to the media, and protect those in precarious situations for whom speaking out bears greater consequences and potential sanctions (Zarkov & Davis). Because of this, I hypothesise that the actresses concerned’s precarious working situations were a driving force behind their choice to stay silent at the time. The period of time between alleged harassments and those who experienced them’s speaking out has led many outside of academia to question why these celebrities waited so long to talk about their harassment, especially in the case of Harvey Weinstein, whose behaviour has been outed as being an open secret in Hollywood for two decades. Indeed, a good deal of popular media coverage has focused on trying to answer that question (Towle, Williams, Farrow), most of which can be reduced down to one concept: power, and powerlessness. Feminist theory posits that workplace sexual harassment is driven more by an underlying desire to reinforce traditional gendered power structures than sexual gratification, which explains why women are dogged by workplace harassment even as they move up the ladder in their organisations (McLaughlin, Uggen & Blackstone). Thus, even women in management positions still experience precarity at work.

#MeToo as a case study emphasises workplace sexual harassment’s grounding in power dynamics, as those who feel they have little power (the precariat) remain silent until those they perceive to have power speak out and provide them with a platform to stand on. For example, the Screen Women’s Action Group reports that while hosting forums for women in the industry, a question they heard constantly was “how can we do anything when they are so all-powerful?” (Screen Women’s Action Group, p. 2). Reporting harassment also takes time and labour many in precarious living and working situations simply do not have, whether they are working multiple jobs or undertaking all the excess labour that comes with income insecurity, such as applying for assistance programs, or looking for/applying for new work (Cochrane et al).

Glamorisation of Creative Labour

Something that sets the creative industries apart from other industries is the glamorisation of its work. Creative industry work is reified as “‘cool’ jobs in ‘hot’ industries” (Neff, Wissinger, & Zukin). Because the work is perceived as providing more than just a wage to the worker, such as social currency and other ‘soft benefits’, like promises of future work, flexibility of labor, or self-actualisation and fulfilment, it can be construed as ‘lifestyle labour’, wherein the social and lifestyle benefits afforded by ‘cool’ work are accepted as supplements to reduced monetary compensation (Zendel). In addition, workers are made to feel as though they should be grateful for the opportunity to work in such ‘cool’ industries, and therefore can and should put up with bad working conditions, whether they be crushingly long hours, undervalued/under-compensated labour, or coworkers/bosses sexually harassing them. Workers in many industries are also increasingly being required by their employers to engage in more labour outside of normal working hours training themselves in new skills to keep up in their fields (Kotamraju, in Neff, Wissinger, & Zukin), which falls within the new category of labour posited by Neff, Wissinger, and Zukin: entrepreneurial labour. So not only is the work itself glorified, but also how it is conducted. The glorification of creative work is encouraged by local government institutions who seek to attract creative workers and grow their economies alongside their creative industries, supporting the image makeover of the starving artist “whose long-abiding vulnerability to occupational neglect is now magically transformed, under the new order of creativity, into a model of enterprising, risk-tolerant pluck” (Ross, p. 15). Meanwhile, the hordes of exploited digital labourers whose work is ‘freely given’ (Terranova) serve as a reminder to creative workers not to charge too much or ask too much of their employers (such as a fair wage or reasonable hours), as there are always more ‘passionate’ workers ready to take their place once their contract expires or their current gig is complete.

Another form of glorification of specifically creative work is the ‘do what you love’ (DWYL) ethos. DWYL suggests that only doing work that a worker loves and is passionate about doing can provide them with self-actualisation, which creates a necessary division between loveable and non-loveable work. The ethos is simply not applicable to workers in fields such as cleaning, whose labour is devalued in the process (Tokumitsu). Not only this, but for the myth of doing-what-you-love to remain plausible to the masses of creative workers who may be swayed by it, labour patterns that do not fit in with the reified image of flexible, enjoyable, and fulfilling creative work must be varnished over and neutralised, which is only too convenient for the elites seeking to minimise such labour anyway. As said by Tokumitsu, “the rise of DWYL demands active refusal to acknowledge work that doesn’t legitimize the ways in which the world’s political, business, and social leaders justify their own power” (Tokumitsu, p. 29). So, non-creative labour is devalued, and simultaneously the inglorious aspects of creative work are minimised; is it any wonder that precarious workers in the creative industries feel they have more to lose when they engage in actions that may threaten their jobs, and are willing to put up with worse working conditions?

Precarity and Women’s Labour

Women have been under-compensated for their labour since time immemorial, being traditionally expected to take on the role of nurturer of children and the family for little recompense. This has unfortunately, yet unsurprisingly, followed women into the workplace. One quantitative measure for this is the gender pay gap, which is particularly acute in the creative industries. In Australia (as of 2015), the gender pay gap across the board was 17.3% (Workplace Gender Equality Agency), compared with 32% for professional artists (Throsby & Petetskaya). In the US, the overall gender pay gap was 22% in 2017 (PayScale), compared with 32% in creative industries. Though that figure varies greatly amongst professions, from 54% for DJs/Musicians to 12% for cinematographers, across almost all factors and industries, male creatives are compensated better than their female counterparts (HoneyBook). Even higher education is insufficient for women in the creative industries to guarantee a fair income, as 24% of woman creatives earn under $5USD per hour (in other words, less than minimum wage) despite 73% holding bachelor degrees (ibid). In the United Kingdom, women employed in the cultural and creative industries earned on average £5800GBP less per year as of 2014 than otherwise-similar men net all controls (O'Brien, et al.). Other descriptors for the ‘ideal’ worker in the creative industries —flexible, grateful, obedient— are terms that coincide with a traditional conception of womanhood. Historically, two thirds of the casual, contingent, and part time labour force was filled by women, and presently women are almost twice as likely to work part time as men. Women also fill three quarters of unpaid internship positions, and industries that rely heavily on internships, such as fashion, media, and arts, tend to be highly feminised (Schwartz). Unpaid internships also tend to drive worker precarity as they replace paid positions and allow companies to skirt minimum wage and labour laws, a situation that is particularly acute in the creative industries (Shade & Jacobson).

As of yet, there is no study focusing particularly on how precarity in its various forms drives sexual harassment of women in the creative industries, and my paper seeks to fill this gap, making use of the large increase in creative women coming forward to tell their stories in the last year as a result of the #MeToo movement.

Methodology

My paper uses a comparative analysis of relevant scholarly texts, explicating on their core concepts and contrasting them with each other, and an analysis of popular/news media articles either written by or featuring interviews with women who have experienced sexual harassment while working in the creative industries, applying the theoretical concepts I have identified in the literature. I use the #MeToo/Times Up movements as a case study to prove the real world consequences of precarity on women’s lived experiences, focusing particularly on the statements made by women in the creative industries as part of the movement. This is because many of their statements speak to precarity as the driving force behind either their experiences of workplace harassment or their initial decision to stay silent about it. As literature on the #MeToo movement is currently scarce and currently predominantly focused on the American creative industries, I will predominantly be focussing on sexual harassment in an American context, while my discussion on precarity will be informed by more global literature.

Coverage in Popular Media

In the wake of #MeToo, numerous media outlets have released articles whose content predominantly consists of interviews with employees in the creative industries (Domanick, Farrow, King). Popular media coverage does not often identify the scholarly concepts present in academic literature, but it does provide a wealth of ‘real life’ examples through which such concepts can be further explicate and problematise them. The interviewee’s stories speak to industries driven by intense competition and financial pressures, staffed by freelance and casual workers operating in the gaps of labour protection laws, and compulsory attendance at alcohol heavy events and the subsequent consequences of alcohol driven lapses in inhibitions (Domanick). Even in the midst of #MeToo, when publicly coming forward about one’s harassment (particularly at the hands of a large industry figure) is arguably less risky than ever before, many who agreed to be interviewed about their experiences in the creative industries still did not want to be identified and spoke only on the condition of anonymity, fearing backlash could harm or even end their careers. One such woman is ‘Eve’, who works in the recording industry (at the time as an A&R scout), and dealt with sexual harassment from an executive of a large organisation in her industry —an organisation that she did not even work at at the time, but hoped to in her future.

“There was an innate feeling that if I were to tell him that I was offended, or set a boundary, that he would never call me again and just disappear back into the ether of the inner circle, and I would never see it again…He had big power in that job to change my life. I don't even know if I'd be where I am right now if I didn't have what he showed me.”

(‘Eve’, in Domanick)

Others stay silent because their harassers control resources they perceive as vital they have access to for the continued viability of their work providing means enough to survive, such as ‘Alice’ (pseudonym), at the time a freelance worker for an ‘up and coming’ podcast network:

"I was absolutely afraid that if I tried to do something in response to [the harassment] that my show would be dropped from the network, effectively killing off most of our listenership…I was also afraid of being alienated by the owner.”

(‘Alice’, in King)

‘Kate’ (pseudonym) a former freelance music writer blamed the precariousness of freelance writing as the main reason she did not inform her editor after being sexually assaulted before an interview with a well known artist, and said the job was “the reason I was able to meet people and get assignments” (in Domanick).

Actresses and victims of sexual harassment at the hands of Harvey Weinstein, Emily Nestor and Gabrielle Moss, spoke to the precarity of their positions and place within the film industry when explaining why they did not come forward about their experiences earlier.

“I was mostly just scared that no one would believe me, or that I would end up out of a job if I tried to prove it” —Gabrielle Moss

“I was very afraid of him. And I knew how well connected he was. And how if I pissed him off then I could never have a career in that industry.” —Emily Nestor

(Both in Farrow)

Many others said that their experiences of harassment made them reconsider their career path in the creative industries, such as freelance writer Natalie, who said her experience of sexual harassment at the hands of a senior writer at her first writing gig left her feeling “minimised”:

"I looked at this gig as affirmation that I was on the right track and could make it as a writer, and as soon as that first DM came in, I immediately felt objectified and disrespected.”

(Natalie, in King)

One difficulty in attempting to report sexual harassment is the lack of codes and regulations surrounding sexual harassment that actually cover many creative workers in their daily work life. Freelance and contract workers are often not covered by anti-harassment laws, and many do not have a sexual harassment clause in their contracts (Honeybook). The other major barrier to reporting sexual harassment is identifying what behaviour actually constitutes sexual harassment, which can be particularly difficult in the creative industry, where networking events are perceived as compulsory to sustaining and growing ones career, and often take place in informal settings where the appropriateness of behaviour can be hard to judge:

“When your business is relationships, there are so many grey areas…We know what the obvious things are, but what are the not obvious things? When does flirtation become harassment? There is no road map.”

(Anonymous former label publicist, in Domanick)

Findings and Analysis

The occurrence of sexual harassment in the creative industries is driven by multiple factors. While many women’s experiences of sexual harassment in the workplace are influenced by the precariousness of their employment, not all women who experience harassment are in precarious working situations. Thus it is important to also analyse the multi-faceted concept of power, who has and does not have it, and to incorporate feminist theory such as notions of gendered power structures in the workplace when investigating women’s experiences of workplace sexual harassment. Both scholarly and popular media literature on sexual harassment tend to fixate on power, but each has a slightly different conception of what power constitutes and how it is driven. The conceptions of power imbalances certainly seem to play a role in how workplace sexual harassment is enabled to both occur and perpetuate, as victims perceive their harassers as being too powerful for their actions to have any effect, as is the case for numerous victims of Harvey Weinstein and the women employed in the screen industry surveyed by the Screen Women’s Action Group. The women whose interviews I read felt the precarity of their situations acutely in the separation they felt from their harassers, describing them as belonging to an ‘inner circle’ or being untouchable, in direct contrast to their own situation within their industry, which they felt was easily erodible.

Work in the creative industries is heavily glorified, so workers are willing to put up with working conditions and labour compensation they would not accept in other, less ‘cool’ industries. This can mean that fringe benefits such as social currency are accepted in place of financial recompense, which feeds into the precarity experienced by low-waged workers in their home lives, such as unstable living situations and food instability. This glorification is closely tied to the ‘do what you love’ phenomenon, whose precursor was a conception of work as something that entirely subordinated pleasure (Sandoval). Of course by comparison work that can be marketed as ‘doing what you love’ appears to be a better choice of labour to engage in, as through the self-fulfilment ones labour produces they may state that their labour is also working for them. I would argue that the glorification of creative work is one of the main reasons why sexual harassment is such a major issue in the creative industries compared to other industries. Creative workers feel that they have more to lose risking their creative job or future in their industry than they would in other, less glamorous jobs, and industry elites are aware of this and able use it to their advantage, knowing that the combination of that and the precarious situations of their victims will protect them by minimising the chances that their victims will report them.

Creative work also often entails a good deal of self marketing. Because of this creatives are highly conscious of their image and seek to preserve it, making them less likely to engage in activities that may tarnish their reputation, such as coming forward about their sexual harassment and being branded ‘difficult’. Their image of their labour may also become highly personal, causing the lines between their labour and their personal identity to blur a great deal. The eradication of the divisions between work life and home life of the past has led workers —particularly workers ‘doing what they love’— to feel that their work is their life. This ideology can be seen in a quote from an anonymous victim of sexual harassment at the hands of Harvey Weinstein, on why they had not come forward about their experience: “If Harvey were to discover my identity, I’m worried that he could ruin my life” (Anonymous, in Farrow). The use of ‘life’ rather than ‘career’ was likely not intentional, but it exemplifies how great an impact they perceive their job having on their life.

One survey focused on women in the creative industries’s experiences of workplace sexual harassment found that 54% of self-employed and freelance women (a common employment situation in the creative industries) reported being sexually harassed at least once in their careers, and 83% did not report their harassment to anyone. Perhaps more troublingly, of those that did choose to make a formal complaint, 51% reported having their complaints ignored (Honeybook). This echoes the sentiments of the women whose statements I found, as one of the reasons many who remained silent about the harassment they experienced gave for not speaking out was a feeling of hopelessness, as they did not believe that their harassers would face any consequences due to their coming forward. Even if they did want to come forward, for workers in many creative industries (such as the music industry) there is no formal governing body to set or uphold industry standards (Domanick). Numerous other creatives are not protected by workplace sexual harassment laws as their working arrangements do not demarcate them to be in a formal employer-employee relationship. This category includes a diverse grouping across the creative industries, including many freelance and contract workers like publicists, makeup artists, or digital artists, and interns. Some creative industries have unions with sexual harassment codes of conduct, but these can either be difficult to join, like the Make-Up Artists and Hair Stylists Guild of the IATSE, which has three methods for entry, each of which has conditions that are nigh impossible to satisfy (Anonymous in Curtin & Sanson); not very powerful, as is the case in New Zealand following the introduction of the Employment Relations (Film Production Work) Amendment Bill in 2010 (Cowlishaw), or hesitant to discipline their own members, particularly in cases of co-worker sexual harassment (Crain).

Earlier on in this essay I identified networking as being one of the clearest examples of labour disseminating out from traditional ‘work’ spaces to society at large (as discussed by Gill & Pratt). The precise nature of networking in informal spaces that lends it to being easily manipulated to perpetuate sexual harassment is that appropriate behaviour in such situations sits in a grey area, meaning that inappropriate behaviour that would be more clearly defined as harassment in an office setting with behavioural codes of conduct is more difficult to assert as being inappropriate. This makes it difficult for creative workers to assess whether their experiences actually constitute sexual harassment. The introduction of alcohol into the equation makes it even more difficult for creative workers to identify their experience as deliberate sexual harassment, or feel confident that they will be taken seriously or believed by their peers should they come forward. Unfortunately this is common as many networking events either take place in bars and restaurants where drinking is expected, and even industry events that do not take place in such venues generally still feature alcohol.

Conclusion

My research confirmed my hypothesis that precarity is a major factor in women’s experiences of workplace harassment. This is particularly acute in the creative industries, due to the extreme imbalances of power present, and because of the glamorisation of creative work, which is driven by concepts such as the ‘do what you love’ ethos, and the informal situations many aspects of creative work are conducted in, such as networking. Some of the limitations of the study included the quotes analysed being pulled from various existing interviews with workers in the creative industries rather than one homogenous study, so the responses I gathered were not in response to the same questions or from interviews conducted in a consistent manner, and may have some discrepancies because of this. However, I believe that this study provides a case for the hypothesis being accurate, so further, more in depth research over a greater period of time into women workers experiences of precarity in the creative industries is justified, in order to identify new ways of combating workplace sexual harassment in the creative industries in the hopes of reducing the high levels at which it is currently occurring.Works Cited

Anonymous. Anonymous, Makeup Artist. In Curtin, M. and Sanson, K. (Eds.) Voices of labor: creativity, craft, and conflict in global Hollywood. University of California Press: Oakland, 2017.

Cochrane, W. et al. A statistical portrait of the NZ precariat. Precarity : Uncertain, insecure and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Eds. S. Groot, C. van Ommen, B. Masters-Awatere & N. Tassell-Matamua. 2017. 27-36.

Corkery, M. “Low-Paid Women Get Hollywood Money to File Harassment Suits.” The New York Times [New York]. 22 May 2018: Web.

Cowlishaw, S. “‘The Hobbit law’ - there and back again.” Newsroom. 30 Jan. 2018: Web.

Crain, M. Sex Discrimination as Collective Harm. The Sex of Class: Women Transforming American Labor. Ed. Dorothy Sue Cobble. New York: Cornell University Press, 2007. 99-116.

Creating Culture Change Around Sexual Harassment in the Screen Industry. Screen Women’s Action Group, 2018.

De Peuter, G. (2011). Creative Economy and Labor Precarity: A Contested Convergence. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 35(4), 417–425.

Domanick, A. “The Dollars and Desperation Silencing #MeToo in Music.” Noisey, 22 Mar. 2018.

Feldblum, C. & Lipnic, V. Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2016.

Farrow, R. "From Aggressive Overtures to Sexual Assault: Harvey Weinstein’s Accusers Tell Their Stories.” The New Yorker [New York]. 23 Oct. 2017: Web.

Flew, T. International models of creative industries policy. Creative Industries. London: Sage, 2012. 33-52.

Gill, R., & Pratt, A. In the Social Factory? Theory, Culture & Society, 25.7-8 (2008): 1-30.

Hardt, M., & Negri, A. Commonwealth. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

HoneyBook. 2017 Gender Pay Gap: Creative Economy Report. HoneyBook & Rising Tide, 2017.

HoneyBook. Sexual Harassment Report. HoneyBook & Rising Tide, 2018.

King, E. “How Freelancers Are Forced to Fend for Themselves Against Sexual Harassment” Broadly. 3 Nov. 2016: Web.

McLaughlin, H., Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. Sexual Harassment, Workplace Authority, and the Paradox of Power. American Sociological Review, 77.4 (2012): 625–647.

Neff, G., Wissinger, E., & Zukin, S. Entrepreneurial Labor among Cultural Producers: “Cool” Jobs in “Hot” Industries, Social Semiotics, 15:3 (2005): 307-334.

Oakley, K. Include Us Out: Economic Development and Social Policy in the Creative Industries. Cultural Trends, 15.4, (2006): 255-273.

O’Brien, D., et al. “Are the Creative Industries Meritocratic? An Analysis of the 2014 British Labour Force Survey.” Cultural Trends, 25.2, (2016): 1–16.

PayScale. THE STATE OF THE Gender Pay Gap in 2018. Payscale.com, 2018.

Ross, A. Nice work if you can get it: the mercurial career of creative industries policy. Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation, 1.1, (Winter 2006-7): 13-30.

Sandoval, M. From passionate labour to compassionate work: Cultural co-ops, do what you love and social change. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 21.2, (2017): 113 - 129

Schwartz, M. “Opportunity Costs: The True Price of Internships.” Dissent, 60.1, (Winter 2013): 41-45.

Shade, L., and Jacobson, J. Hungry for the job: gender, unpaid internships, and the creative industries. The Sociological Review, 63:S1, (2015): 188–205.

Throsby, D., and Petetskaya, K. Making Art Work: An economic study of professional artists in Australia. Australia Council for the Arts, 2017.

Tokumitsu, M. “In the Name of Love.” Slate. 16 Jan. 2014: Web.

Tokumitsu, M. Do What You Love: And Other Lies About Success and Happiness. New York: Reagan Arts, 2015.

Towle, M. “Why did no one speak out about Harvey Weinstein?” The Wireless [Wellington]. 11 Oct. 2017: Web.

Williams, Z. “Why did no one speak out about Harvey Weinstein?” The Guardian [Manchester]. 10 Oct. 2017: Web.

Workplace Gender Equality Agency. Gender pay gap statistics. Australian Government, 2016.

Zarkov, D., and Davis, K. Ambiguities and dilemmas around #MeToo: #ForHow Long and #WhereTo? European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25.1 (2018): 3-9.

Zendel, A. LIVING THE DREAM: PRECARIOUS LABOUR IN THE LIVE MUSIC INDUSTRY. MA thesis, University of Toronto, 2014.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Slingshot Group announced the 6 critical skills leaders

Slingshot Group Co., Ltd. a leading consulting firm offering total solutions for high-quality leadership and organizational development services, has announced the 6 critical skills that leaders in the new era need to succeed in the future world of work. To provide an appropriate and efficient response to the job market and professionals’ needs, Slingshot Group has partnered with Globish Academia (Thailand) Co., Ltd., a rising EdTech startup that has seen success in the development of an online English learning platform in Thailand with over 15,000 users, to introduce Thailand’s first “OMG Coaching-on-Demand Platform. Slingshot Group will enable leaders to keep up with the rapid pace of digital disruptions with a learning experience delivered through the new coaching program “Coaching in Transition”. This Coaching-on-Demand Platform enables executives and professionals to learn from highly experienced coaches anywhere and at any time. It aims to be a practical coaching platform accessible to all at an affordable price. Notably, it helps address pain points when individual leaders ask for recommendations and assists them make decisions and develop themselves in a limited timeframe. The OMG Coaching-on-Demand Platform will match schedules between coaches and coachees allowing them to save travel time. In addition to hands-on experience and practical knowledge, this coaching platform is equipped with the powerful tools to meet learning trends in the digital age. Dr. Sutisophan Chuaywongyart, Chief Executive Officer of Slingshot Group Co., Ltd., says its recent study clearly indicated the 6 skills new generation leaders will need to thrive in the future. The survey confirmed that technological advancements cause widespread disruption to work in tomorrow’s world as well as to daily life. Leaders and employees must thus adapt to be in line with changing job characteristics and ways of working. The essential skills for the future comprise: Creative Conception - skills to think outside the box to create diverse and innovative strategies Logical investigation - ability to use logical thinking or reasoning skills for analysis and assessment Wicked-Problem Self-Efficiency - skills to inspect and choose information from various sources to tackle complex problems Connectedness - ability to relate and respond to others in a proper manner to build positive interactions and coexistence as needed Virtual Collaboration - ability to coordinate and work effectively through various channels without barriers of area and time Life-long Learning Experimentation - ability to develop ongoing self-learning voluntarily. “As a professional in the leadership and organizational development, Slingshot Group came up with the idea of developing an effective tool to help leaders and employees easily enhance their working skills without limitations. To achieve this, Slingshot Group has entered into partnership with Globish Academia (Thailand) Co., Ltd., the EdTech startup that has successfully developed an online English learning platform in Thailand with over 15,000 users, to launch Thailand’s first OMG Coaching-on-Demand Platform. This will become an important tool for leaders in the new era and help their organizations deal with digital disruption,” Dr. Sutisophan explains. In addition to jointly developing the tool that helps people improve the skills they will need in the future working-world, the platform also addresses the pain points of Thai leaders who have limited time for critical thinking and decisions in an age of digital disruption where speed is of the essence in developing a competitive advantage. The OMG Coaching-on-Demand Platform is an effective tool as it enables coaches to choose a schedule to receive coaching from coaches certified by Slingshot anywhere and at any time. Dr. Sutisophan adds that the target groups of OMG Coaching-on-Demand Platform are working people, businessmen and women and entrepreneurs who need coaching as well as middle to high-ranking executives. The first program on the Slingshot platform is “Coaching in Transition” and the company plans to develop further coaching programs for business and personal development through life. The business coaching services include executive coaching, career coaching, life coaching and areas such as parent coaching and athlete coaching. After the launch, the company expects to have at least 300 clients and that the new coaching platform will help increase the company’s revenue by 45 percent. Mr. Takarn Ananthothai, Chief Executive Officer, Globish Academia (Thailand) Co., Ltd., the EdTech startup that developed an online English learning platform through live one-on-one classes with international coaches, explains the importance of blending technology with organizational learning, noting that learners need information quickly and which can be edited in line with individual needs. It is therefore essential for organizations to adapt by developing tools that help human resources learn anywhere and at any time. He says that the OMG Coaching-on-Demand Platform was created by leveraging user experiences on the Globish online English learning platform and blending this with the experience of Slingshot coaches to develop suitable features. The platform includes one-on-one coaching through video calls enabling coaches and coaches to see each other, send files to each other or write together on an online whiteboard. Monitoring and coaching evaluations collect all relevant information, allowing coaches, learners as well organizations to monitor information from the coaching session and use it for analysis and to draw conclusions on the coaching outcomes. The partnership between Slingshot Group and Globish Academia (Thailand) is an exchange model based on the knowledge, experiences and expertise of the two companies. Globish has used its success in developing an online English learning platform through private conversation classes to develop the OMG Coaching-on-Demand Platform while Slingshot Group, which has experience in leadership and organizational development, will help Globish develop and enhance its potential for growth in parallel with the overall business expansion of startups. Related Link Slingshot Group Co., Ltd. Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

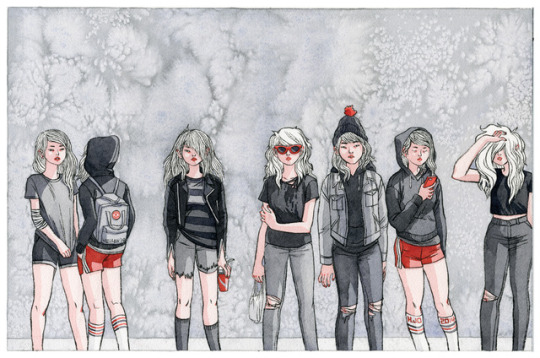

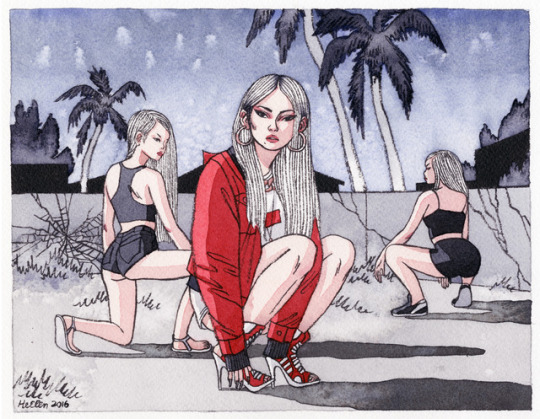

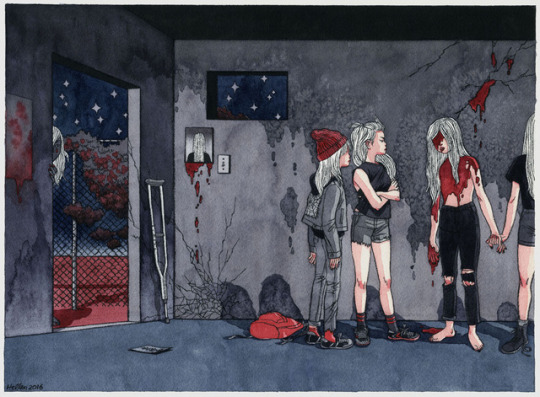

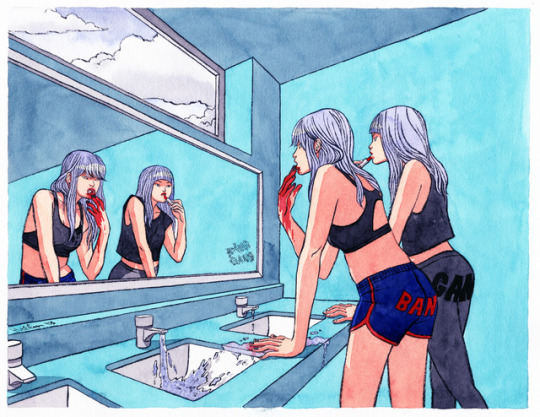

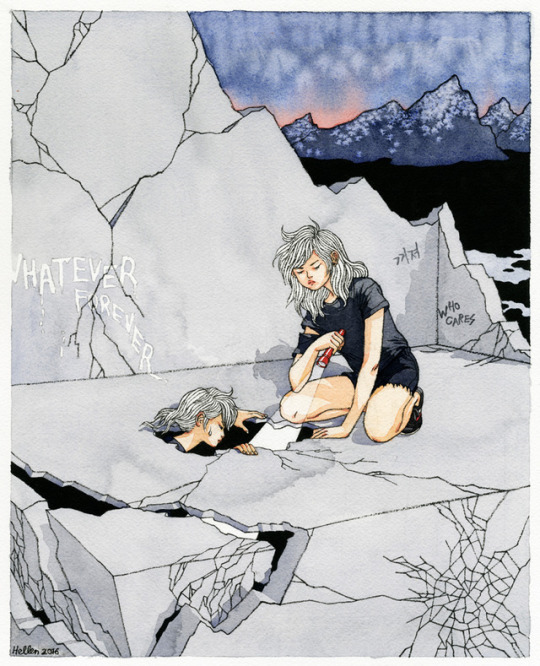

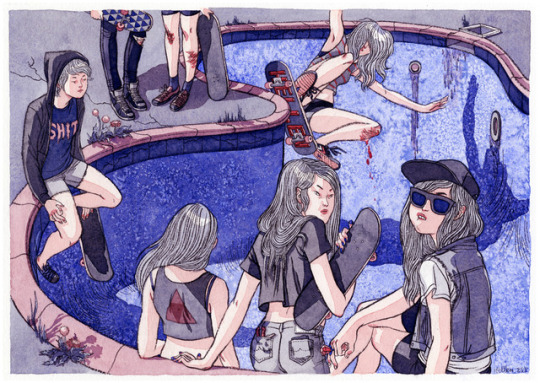

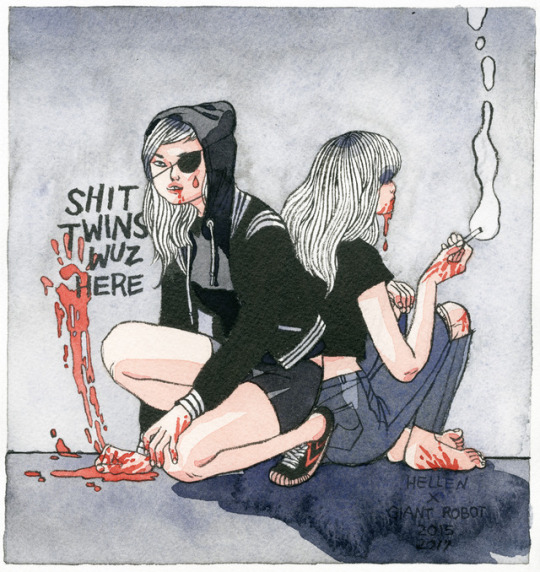

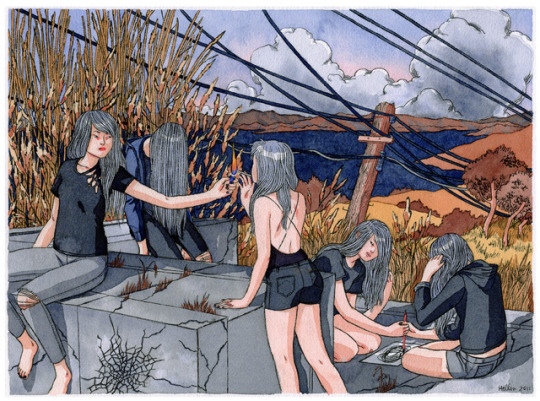

Sketchy Behavior | Hellen Jo

Never afraid to speak and/or draw her mind, Los Angeles based artist and illustrator, Hellen Jo and her characters can be described as rough, vulgar, tough, jaded, powerful, bratty and bad-ass - AKA her own brand of femininity. Known for her comic Jin & Jam, and her work as an illustrator and storyboard artist for shows such as Steven Universe and Regular Show, Hellen’s rebellious, and sometimes grotesque artwork and illustrations are redefining Asian American women and women of color in comics. In fact, that’s why Hellen Jo was a must-interviewee for our latest Sketchy Behavior where we talk to her about her love of comics and zines, her antiheroines, and redefining what Asian American women identity is or can be; and what her ultimate dream project realized would be.

Tell folks a little about yourself. So is it Helllen with three “l”’s? Mainly because your IG handle and website has a whole lot of extra “l”’s?

Haha my actual name is Hellen with two L’s. All my emails and urls contain a different number of L’s to confuse everyone. My grandfather took my American name from the Catholic saint, but he spelled it wrong, and now I share the same name as the mythological progenitor of the Greek people. But I like it better than my Korean name, which literally means, “graceful water lily” HAHAHA. I am an illustrator-slash-painter-slash-I-don’t-know-what living and working in Los Angeles.

Let’s talk about your early childhood / background. I read you’re from San Jose, CA and both your folks were professors, which is really cool!! How did you end up making art instead of teaching a room full of students about Hotel Management or Medieval History? Just curious where you got your “creative bug” and what early comics, arts, and/or influences led you down the road to becoming an artist?

I grew up in South San Jose, and yes, both of my parents are professors, of finance and of applied linguistics. A lot of my extended family are professors too, so I grew up parroting their desire for academia, but really, I started drawing when I was a wee babe, and I’ve always wanted to be a cartoonist. When I was really young, my parents drew for fun, really rarely; my dad could draw the shit out of fish and dogs, and my mom painted these really beautiful watercolor still lifes. I was fascinated, and I’d spend all my time drawing on stacks and stacks of dot matrix paper by myself. My parents also had a few art books around the house, and I remember staring so hard at a book of Modigliani nudes that my eyes burned holes through the pages.

What was the first comics you came across?

The first comics I ever got were translated mangas that were given to me by relatives when we’d visit Korea. I remember getting Candy Candy, a flowery glittery shojo manga for girls, and I was mesmerized by all the sparkly romance and starry huge eyes. I was also enthralled by Ranma ½, a gender bending teen manga that was equal parts cute art, cuss words, and shit too sexy for a kid my age. However, I was mostly thrilled that I could understand the stories with really minimal Korean reading skills, thus cementing a forever love of comics. In junior high and high school, I read a mix of newspaper strips and some limited manga, and I was enthralled with MTV cartoons “Daria” and “Aeon Flux”, but I wasn’t exposed to zines or graphic novels until I moved to Berkeley for college.

Did you have a first comic shop you haunted? What did you fill your comic art hunger with?

Being a super sheltered teen with not-great social skills, I was lonely my first semester, so I would lurk at Cody’s Books and Comic Relief every single day after classes. I read the entirety of Xaime Hernandez’s Love & Rockets volume, The Death of Speedy one afternoon at Cody’s, and it literally made me high; I was so hooked. I amassed some massive credit card debt buying and reading as many amazing comics as I could those first (and only) couple years of school: all of Los Bros Hernandez’s Love & Rockets, Dan Clowes’ Eightball, Julie Doucet’s Dirty Plotte comics, Peter Bagge’s Hate series, Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, Charles Burns’ Black Hole, Taiyo Matsumoto’s Black and White, Junji Ito’s Tomie and Uzumaki volumes… I could not believe the scope and breadth of the alternative comics genre, and the stories were so insanely good; they literally mesmerized me. I was so obsessed; I even skulked around the tiny comics section at UC Berkeley’s Moffitt Library in search of books I hadn’t read, and amid the fifty volumes of Doonesbury strips, some sick university librarian had included an early English translation of the Suehiro Maruo collection, Ultra Gash Inferno. That book blew my tiny mind about a hundred times; it’s totally fucked up erotic-grotesque horror porn, but the art is unbelievably beautiful. I read that entire thing sitting on the floor in the aisle, feverishly praying to God to forgive my sins after I finished the book, because I was way too ashamed to check it out of the library.

How about zines? I imagine a comic devouring ….

I devoured zines at a nearly equally fervent pace, including those by Aaron Cometbus, Al Burian (Burn Collector), Doris, John Pham, Jason Shiga, Lark Pien, Mimi Thi Nguyen, etc. I had never seen a zine before in my life, and suddenly, I was living in a town full of zinesters. I was drowning in inspiration. I tried to copy the art and writing of everything I read, and I spent a lot of my time making band flyers, trying to pass off zines as suitable replacements for term papers (this worked just once), and making monthly auto-bio comics for a few student publications. Eventually, I dropped out of school, then dropped out of school again, and I made my first published comic, Jin & Jam; then it all became real.

What was your early works like? and how did these become fodder for your self-published stuff later? What about your own experiences did you feel needed to be expressed in your own comics and artwork?

As a kid I was mostly copying sparkly girl manga and Sailor Moon stickers, and I don’t think I’ve really strayed all that far from that. My first few zines were cutesy autobiographical comics about crushes and falling asleep at the library; incredibly dull stuff. I made a super fun split comic/ep with this band I loved, The Clarendon Hills, but after that point, I was tired of drawing cute, goofy shit.

I had also really been obsessed with Korean ghost horror movies in high school, and I wanted to make comics that reflected more of that kind of coming-of-age violence and rage, so I made a couple standalone horror comics, Paralysis and Blister. These were longer than anything I’d ever done (forty to fifty pages each), and I felt like I was finally figuring out how to write interesting stories. I eventually dropped out of school and made Jin & Jam, based a bit on growing up in San Jose and on other kids I had grown up with.

At the time, there were still relatively few Asian American women in comics, and I was tired of whatever hyper-cute, yellow-fever, Japanified shit we were being pigeon-holed into, so I reacted by writing and drawing vulgar girls who started fights and didn’t give a fuck. I went to art school for a few semesters, got better at drawing people, and went on to draw nothing but mean bad girl ne'erdowells. I’d never been a very strong or defiant personality outwardly, but I’ve always been a pretty big fuckin bitch on the inside, and I just wanted to draw how I feel, in the most sincere way possible. And naturally, over the years, as I continued to develop this attitude in my art, I was able to express it better in person as well. Self-actualization through making comics!

For folks who don’t read comics, can you explain why they are SO AMAZING and moving to you! What about the format, art and overall genre makes them so great and not just your typical “funnies.”

I truly believe that comics are the greatest narrative format and art medium of all time! They are completely full of potential; you can draw and write whatever the hell you can think of, there are no real rules, and you as author and artist can create a deep and intimate experience for your reader. You can bare your vulnerabilities or yell at the world or create a visual masterpiece or inform people, visually and narratively. I don’t even believe that good art makes good comics; writing is king, and the art should really serve to further the story. Some of the worst comics I’ve ever seen had the most amazing art, and some of the greatest comics I’ve loved have the plainest, most naive, even ugly visuals, but those authors were able to finesse a symbiotic relationship between the text and the images to tell a compelling story. People are already so drawn to images, so it makes sense to me that they can enhance a reader’s literary experience so much.

I read that Taiyo Matsumoto is one of your all time inspirations. Most folks probably don’t know much about this master of comics, heck my knowledge is limited, so what makes his work speak to you so much? Perhaps it’ll encourage folks to venture into a new world of art exploration through visual comics.

Taiyo Matsumoto is the all time master of coming-of-age comics. I worship at his altar, for real. He is a Japanese artist, so technically his work is manga, but his masterful storytelling and singular visuals are so different from most manga, beyond categorization. He writes quiet, powerful stories about boys, girls, and teens who live in uncaring worlds surrounded by unfeeling adults, but they rise to these challenges and thrive in spite of themselves. The characters feel deeply, and the reader can’t help but ache and rage and celebrate just as fully. The drawings are beautiful and sensitive, with rough, loose artwork consisting of scratchy lines and cinematically composed shots.

What were some of your first memories with his work?

I remember buying the first two Pulp volumes of Black and White (also published as Tekkonkinkreet) at Comic Relief, reading them both at home that day, and then, covered in tears, literally *running* back that evening to buy the last volume before the store closed. I probably cried a dozen times while reading it; it’s a story about two orphan boys who protect each other in a neo-Vegas-like city of vice, but the characters were so brutal and brilliant and poignant. I had never read anything like that before, and it literally made me sick that, at the time, none of his other works were available in English. Eventually, I figured out that he was more widely published in Korea, so on every family trip, I’d run away from my folks for a day and buy as many of his books as I could carry back to the US. I made my way, slowly, through the Korean translations of Hana-otoko, Ping Pong (another incredible favorite!), and Zero. A beautiful collection of short stories, Blue Spring, was published in English, and then VIZ began translating the series No. 5, but they abruptly stopped mid-series due to low book sales. I was so starved for his work that at that point, I’d ebay his art books and comics only available in Japanese and just stare at them. Eventually, Black and White was made into the anime film, Tekkonkinkreet, and Ping Pong was made into an anime mini-series, and his rise in popularity ensured a wider English availability of his work. His current series, Sunny, is being translated and published here, and every volume breaks my heart a million times.

I’m sorry, this just turned into a gushy, gross fan fest, but Matsumoto’s books really changed my entire perspective on how comics can be written and paced, how characters can be developed fully, and how important comics really are to me. I love them so much!!!!!

You’ve worked in so many cool fields such as a storyboard artist and designer, and on various cartoons, such as Steven Universe. For folks who are interested in those fields, what can you tell folks about that? I’m sure like most artists, you’d rather be spending those long hours working on your own personal art, so how do you balance them? How did you move from a comic artist to working as a storyboarding artist?

I stopped working in animation about a year and a half ago, but the transition from indie comics to storyboarding was rough one, for me. I got into storyboarding at a time when a lot of kids’ animation networks were starting to hire outside the pool of animation school graduates and reach into the scummy ponds of comics. In my case, the creator of Regular Show, JG Quintel, had bought some of my comics at San Diego Comic-Con from my publisher, and he offered me a storyboard revisionist test.

Some cartoonists, like my partner Calvin Wong, were able to transition wonderfully; cartoonists and board artists are both visual storytellers, and once they’d learn the ropes, many of them thrived and succeeded. I can’t say the same for myself; I have major time management issues, I draw and write incredibly slowly, and going from working completely alone to pitching and revising stories with directors and showrunners was just a real shock to my system. For most of my time at Cartoon Network and FOX ADHD, I wasn’t able to do much personal work, but I crammed it in where I could.

Storyboarding also requires a lot of late nights and crazy work hours, to meet pitch deadlines and to rewrite and redraw large portions of your board. I just couldn’t deal. I lost a lot of weight, more of my hair fell out, and the extreme stress of the job put my undiagnosed diabetes into overdrive (stress makes your liver pump out sugar like crazy, look it up, people!) I realized that this industry was not meant for lard lads like me, and when the opportunity came to stop, I did. I could never figure out the balance between my job and my personal work, and I finally chose the latter. Now I’m trying to figure out the balance between making personal work and surviving, but I’ve yet to crack that nut either!

From your art I get a sense of rebellion and angst, how did this morph into an outlet through comics, cartoons, and illustration? Some aspects of your work that are so cool is the fact that your characters are female and women of color and in a completely new way. Asian characters definitely get stereotype in art and comics, so when did you consciously start to create these awesome antiheroines and redefine what Asian/Asian American women/girl identity is or can be?

A lot of the seething rage bubbling behind my eyes has been simmering there since childhood, and a very large portion of that anger comes directly from all the racism and sexism I’ve experienced as a child and adult. I’ve been treated patronizingly by boys and men who expect an Asian girl to be frail, demure, receptive, and soft-spoken. I’ve experienced yellow fever from dudes who are clearly more interested in my slanted eyes and sideways cunt than in whatever it is I have to say. Even in comics and illustration, people constantly tell me I must be influenced by Japanese woodblock print (pray tell, where in the holy fuck does that come from???), or they’ll look at a painting I’ve done of a girl bleeding from her mouth and dismiss my work as “cute”. I despise this complete lack of respect, for me and for Asian American women in general, and I’ve made it my life mission to depict my girls as I would prefer to be seen: fucking angry, violent, mean, dirty and gross, unapproachable, tough, jaded, ugly, powerful, and completely apathetic to you and your shit. Any rebellion and angst in my work comes directly from my own anger, and in my opinion, it makes that shit way better. Girls and women of color get so little respect in real life, so why not “be the change I want to see” in my drawings?

I think I was always aware of this lack of respect, and the “othering” of Asian American women, but once I got to college and learned to put a name to the racism and xenophobia and sexism and fetishism that we experience, my heart burst into angry flames, and it exploded into all of my art. I’ve never been able to hold that back, and I’m not interested in doing so, ever.

Talk about your process and mediums and process. Are you a night owl or an early bird artist? Do you have stacks of in-progress works or are you a one and down drawing person? Do you jot down notes or are you a sketch book person.

I am a paper and pencil artist all the way; I do work digitally sometimes, to make gifs or to storyboard, but I hate drawing and coloring on the computer. I’m terrible at it! I draw everything in pencil first, erasing a hundred thousand times along the way toward a good drawing. For my paintings, I’ll then ink with brush pen and paint with watercolor, all on coldpress Arches. For comics, I ink with whatever, brush pen or fountain pen, or leave the pencil, usually on bristol board. I’ve also been keeping sketchbooks more recently (never really maintained the habit before), where I like to doodle fountain pen and color with Copic markers. In sketchbooks, I’ll slap post-its on mistakes, a trick I learned from paper storyboarding on Regular Show.

I am a total night owl and a hermit; I have to be really isolated to get anything done, but at the same time, being so alone makes me crave social interaction in quick, fiery bursts. I’ll go on social rampages for a week at a time, and then jump back into my hidey hole and stay hidden for months, avoiding everyone. It’s not a very productive or healthy way to be, but it’s how I’ve always been.

I have great difficulty trying to juggle multiple tasks; I tend to devote all my mental energy and focus into whatever I’m working on at the time, so I need to complete each piece before I can do anything else. It’s an incredibly inefficient, time-wasting way of making art, but it’s also the only way I can produce drawings that I am satisfied with.

If we were to bust into your workspace or studio, what would we find? and what would you not want us to find?

You’d find an unshowered me, drawing in my underwear, which coincidentally is also what I do not want you to find!

You’d also find a room half made into workspace (more below), and half taken over by boxes of t-shirts and sweatshirts (I do all my own mailorder fulfillment, like an idiot!) I also like to surround myself with junk I find inspiring, so the walls are covered in prints and originals by some of my favorite artists, a bookshelf along the back wall is filled with about a third of my favorite comics and books and zines, and every available non-work surface (including desk, wall shelves, and bulletin boards) are covered in vintage toys, dice, tchotchkes, bottles, lighters and folding knives, weird dolls and figurines, a variety of fake cigarettes (I have a collection…)

Work-space wise, I have two long desks placed along a wall; the left desk has my computer and Cintiq, as well as my ancient laptop. Underneath and to the side of this desk are my large-format Epson scanner, fancy-ass Epson giclee printer, and a Brother double-sided laser printer. The right desk has a cutting mat, an adjustable drawing surface, and a hundred million pens and half my supplies/crafts hoard. I have a giant guillotine paper cutter for zines underneath this desk. I’ve got two closets filled with button making supplies, additional supplies/crafts hoard, and all kinds of watercolor paper, bristol paper, and mailing envelopes are crammed into every shelf, alcove, gap. This room has five lamps because I need my eyes to burn when I’m working. Also, everything is covered in stickers because I am obsessed with stickers.

What is something you’d like to see happen more often if at all in the contemporary art world? How’s the LA art scene holding up? Whaddya think?

As an artist who adores comics, I have a deep affection for low-brow mediums getting high-art and high-literary respect. Not that a comic needs to be shown in a gallery to be a valid art form, but I am so excited that comics that used to be considered fringe or underground are gaining traction as important works of art and literature. I wish this upward trajectory would continue forever, until everyone understands the love I feel for comics, but who knows what the future holds: the New York Times just recently stopped publishing their Graphic Novel Best Seller lists, and I think it’s a damn shame.

The LA art scene is really interesting to me, because it embraces both hi and lo brow work so readily; fancy pants galleries that make catalogues and sell to art dealers have openings right alongside pop-art stores that sell zines and comics, and I enjoy having access to both. I will say that I think LA galleries are a bit oversaturated with art shows devoted to television and pop culture fan art; yeah, I get that you loooooooove that crazy 70s cult classic sci-fi series and you want to draw Mulder and Scully and Boba Fett in sexual repose for the rest of your life, but I’m more excited about seeing new and original work from everyone. I know you have something to say, and I want to see it.

Mostly, I’d obviously love to see more women of color making art and making comics; we’ve come a long way since I started making zines in 2002, and there are some incredible WOC cartoonists making amazing work right now, but we need more more MORE!

What would be your ultimate dream project? What is something you haven’t tried and would love to give it a go at? Dream collaborations?

My ultimate dream project is the Great American Graphic Novel, but I am so shit at finishing anything that I have not been able to even approach this terrifying prospect. But I figure I have until the day of my death to make something, so … one step at a time?

As far as something I’ve never tried, I’ve been recently interested in site-specific installation; I’ve always been a drawer for print, confined to the desk, and I’m in awe of cartoonists and illustrators who have transitioned to other forms of visual media, whether it be video, sculpture, performance, whatever. I know my personality tends toward repeating the same motions forever and ever, and I hope I can break out of that and make something really different and challenging for myself. I also secretly want to make music but I am the shittiest guitarist ever so maybe it’s better for the world that I don’t!

The dreamiest collaboration I can think of is to illustrate a skate deck for any sick-ass teen girl or woman skater. Seriously, if any board companies wanna make this happen, EMAIL ME

Give us your top 5 of your current favorite comic artists as well as your top 5 artists in general.

Top 5 Current Favorite Comic Artists:

1. Jonny Negron 2. Jillian Tamaki 3. Michael DeForge 4. Ines Estrada 5. Anna Haifisch

Top 5 Artists of All Time

1. Taiyo Matsumoto 2. Xaime Hernandez 3. David Shrigley 4. Julie Doucet 5. Daniel Clowes

What are your favorite style of VANS? And how would you describe your own personal style?

My favorite VANS are the all-black Authentic Lo Pros, although I have a soft spot for my first pair of Cara Beth Burnsides in high school (they were so ugly and I never skated, but I loved them).

My personal style can be described as aging colorblind tomboy who dresses herself in the dark; my favorite outfit is a black hoodie with black denim shorts and black socks and black sneakers.

What do you have planned for this 2017? New shows? New published works?

I’ve got two group shows with some of my favorite artists in the works; I’m so excited but I can’t share any details yet. I’ve also been writing a new comic, but don’t believe it til ya see it!

Best bit of advice and worse advice in regards to art?

Best Advice: Never be satisfied; always challenge yourself to make your art better than everything you’ve done previously.

Worst Advice: Make comics as a stepping stone towards getting a job in animation. When people do this, you can smell the stink of insincerity a mile away. Fuck you, comics are a beautiful medium, and every shitty asshole who does this, I hate your guts!

Follow Hellen Jo

Website: http://helllllen.org Shop: http://helllllen.bigcartel.com Instagram: @helllllenjjjjjo

Images courtesy of the artist

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Updated: Storytelling is a Form of Education

Storytelling goes beyond what the realm of academia strives for, putting what you learn, to use in the real world. Through storytelling, seems odd right? But it’s something we are all accustomed to. We remember stories we heard from when we were kids and often can recount them with the same vigor it was told to us. How is it that things like storytelling and creative writing often stay with us more? It is the emotion attached to these stories that make them appealing to so many individuals in comparison to conventional learning styles. There is respect in knowing that academia is straightforward and factual, but it’s those qualities of analyzing and finding what a story means to you within creative writing that brings feminist narratives to life by its far-reaching effects that appeal to emotions and incite change.