#artist: anthony newley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

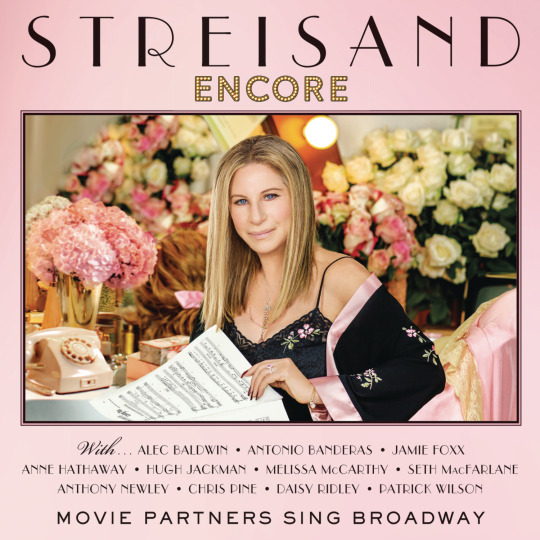

Tracklist:

At The Ballet • Loving You • Who Can I Turn To (When Nobody Needs Me) • Any Moment Now • I Didn't Know What Time It Was • The Best Thing That Ever Has Happened • Not A Day Goes By • Anything You Can Do • Fifty Percent • I'll Be Seeing You / I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face • Losing My Mind • Pure Imagination • Take Me To The World • Climb Ev'ry Mountain

Spotify ♪ YouTube

#hyltta-polls#polls#artist: barbra streisand#language: english#decade: 2010s#Traditional Pop#Vocal Pop#Show Tunes#artist: anne hathaway#artist: daisy ridley#artist: patrick wilson#artist: anthony newley#artist: hugh jackman#artist: alec baldwin#artist: melissa mccarthy#artist: chris pine#artist: seth macfarlane#artist: antonio banderas#artist: jamie foxx

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupin III - Feeling Good from The Roar of the Greasepaint (AI voiced)

(if you have troubles seeing this video you can check the YouTube link: https://youtu.be/6SwnVuBhkYE) Lupin the Third is singing Feeling Good for you. I hope you will enjoy this piece just as I do! For more songs check "L3-800 music" in the searchbar. = Disclaimer = This video contains making a real person appear to say something they didn't say. Please, don't use it for further remixes or claims! = Credits = -I spend quite the time and effort to create these but please be sure to also support the original artists of my reworks! Original song / Anthony Newley, Leslie Bricusse, Nina Simone Original performer / Matthew Ifield AI voice / Kanichi Kurita (Lupin III) AI voice model / made by me and @Nodomatic Art / by me but references were used Font / Kikola Nafi = Use AI art with care and caution! = It's surely an amazing tool which must not be used in the wrong way! I promise my usage of AI voices will be only used for harmless fun and peaceful art like this.

#L3-800 music#lupin the iii#lupin the 3rd#lupin the third#lupin iii#arsene lupin the third#lupin sansei#lupin#feeling good#rupan sansei#lupin 3rd#L3-800

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Doctor Dolittle Songs by The "Bugs" Bower Orchestra & Chorus featuring Ron Marshall, released on the Pickwick/33 label (catalog number SPC-3088). This is a 1968 vinyl LP featuring songs from the 1967 Doctor Dolittle film musical, composed by Leslie Bricusse.

Below is a detailed overview based on the information available:

Album Details

Title: The Great Doctor Dolittle Songs (also listed as Songs from Doctor Dolittle on some platforms)

Artists: The "Bugs" Bower Orchestra & Chorus, featuring Ron Marshall

Label: Pickwick/33 Records

Catalog Number: SPC-3088

Release Year: 1968

Format: 12" Vinyl LP, Stereo

Manufacturer: Pickwick International Inc. (distributed in the UK by Pickwick International Inc. (GB) Ltd., and in Australia by Basic Books Pty.)

ASIN: B00GGNXWGO (Amazon listing)

Content and Nature of the Album

This Pickwick/33 release is a budget album, likely a sound-alike or cover version of songs from the 1967 Doctor Dolittle film, rather than the original soundtrack featuring Rex Harrison, Samantha Eggar, and Anthony Newley. Pickwick Records was known for producing affordable LPs, often with in-house artists covering popular songs to capitalize on a film’s or musical’s success. The “Bugs” Bower Orchestra & Chorus, led by arranger/conductor “Bugs” Bower, and featuring vocalist Ron Marshall, performs these covers. Ron Marshall also appeared on other Pickwick releases, such as a 1967 Oliver! album (SPC-3135), suggesting he was a regular vocalist for their budget recordings.

While the exact tracklist for The Great Doctor Dolittle Songs isn’t fully detailed in the provided sources, it likely includes popular songs from the 1967 film, such as:

“Talk to the Animals” (the Oscar-winning song)

“My Friend the Doctor”

“Fabulous Places”

“Doctor Dolittle”

“Like Animals”

These tracks are inferred from similar Pickwick releases and other budget albums like Hits From Doctor Dolittle and Other Favorite Animal Songs by The Hollywood Sound Stage Orchestra, which included these songs. Pickwick’s albums typically focused on the most recognizable tracks to appeal to casual buyers, so less prominent songs (e.g., “The Voice of Protest” or “Where Are the Words”) may have been omitted.

Key Features

Sound-alike Nature: This album does not feature the original film cast (e.g., Rex Harrison) or the original orchestrations by Alexander Courage and Lionel Newman. Instead, “Bugs” Bower’s arrangements and Ron Marshall’s vocals provide a budget-friendly interpretation of Bricusse’s songs.

Production: The album was produced by Pickwick International, known for cost-cutting measures like simplified arrangements and minimal packaging. The vinyl is noted for being in good condition in some listings, though Pickwick LPs often had basic cardboard jackets prone to wear.

Availability: The album is available on platforms like Amazon and was listed as a vintage sealed vinyl LP (SPC-3088) on sites like Toad Hall Online. It’s also referenced on Discogs, though specific tracklists and credits are limited.

Additional Context

“Bugs” Bower: Maurice “Bugs” Bower was a conductor and arranger for Pickwick, often working on their budget soundtrack and children’s albums. His orchestra and chorus were used to recreate the feel of popular musicals.

Ron Marshall: A vocalist featured on multiple Pickwick releases, including Oliver! (1967), where he performed alongside the Pickwick Children’s Chorus & Orchestra, also arranged by Bower.

Pickwick/33 Practices: Pickwick’s budget releases sometimes misled buyers by mimicking original soundtracks in cover art or titles. This album’s title, The Great Doctor Dolittle Songs, suggests an attempt to evoke the 1967 film’s popularity without explicitly claiming to be the original soundtrack.

Purchase and Condition

Where to Find: The album is listed on Amazon (ASIN: B00GGNXWGO, available since November 5, 2013) and vintage record sites like Discogs, eBay, and Toad Hall Online. Etsy also lists Pickwick/33 records, though specific availability for this title varies, with some items marked unavailable.

Condition: Listings note that the vinyl and label are typically in very good condition, though jackets may show light storage wear, stains, or small paper pulls. Check photos on Discogs or eBay for specific copies.

Price: Prices vary based on condition and whether the LP is sealed. As a budget release, it’s generally affordable, though rare sealed copies may command higher prices on collector sites.

Comparison to Original Soundtrack

For contrast, the original 1967 Doctor Dolittle soundtrack (20th Century Fox Records) and its 2017 50th Anniversary Expanded Edition (La-La Land Records) feature the authentic performances by Rex Harrison and others, with lush orchestrations and additional demos. The Pickwick album, while charming for collectors of vintage vinyl or budget releases, offers a more economical, less polished take on the same material.

Recommendations

If You’re a Collector: This album is a great find for fans of 1960s budget vinyl or Pickwick curiosities. Check Discogs, eBay, or Amazon for available copies, and verify the condition of the jacket and vinyl before purchasing.

If You Want the Original Songs: Consider the 1967 original soundtrack or the 2017 La-La Land Records expanded edition for the authentic Doctor Dolittle experience, including unreleased tracks and demos.

Further Details: If you have the album or a specific copy in mind, I can analyze images or listings (e.g., from Discogs or Etsy) for tracklists or condition details. Alternatively, I can search for additional listings to help you find a copy.

#Vinyl#Doctor Dolittle#Pickwick/33#Bugs Bower#Ron Marshall#1968#Sound-alike#Leslie Bricusse#Talk to the Animals#Budget Vinyl#SPC-3088#Musical Soundtrack#Fabulous Places#My Friend the Doctor#Vintage LP#Stereo#Collectible#1960s#Orchestra#Chorus#Retro#Discogs#eBay#Sealed Vinyl#Rex Harrison#Movie Soundtrack#20th Century Fox#Vinyl Collecting#Jacket Condition#vinylcommunity

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Howard Davies and Robert Newton in Oliver Twist (David Lean, 1948)

Cast: Robert Newton, Alec Guinness, Kay Walsh, John Howard Davies, Francis L. Sullivan, Henry Stephenson, Mary Clare, Anthony Newley. Screenplay: David Lean, Stanley Haynes, based on a novel by Charles Dickens. Cinematography: Guy Greene. Art direction: John Bryan. Film editing: Jack Harris. Music: Arnold Bax.

After George Cukor's 1935 David Copperfield, this is my favorite adaptation of Dickens for film or TV. What Lean does right is to treat the Dickens book as a fable, not a novel. A novel takes its characters seriously as human beings; a fable sees them as embodiments of good and evil. And there's plenty of evil on display in Oliver Twist, from the brute evil of Bill Sikes (Robert Newton) to the venal evil of Fagin (Alec Guinness) to the stupid evil of Mr. Bumble (Francis L. Sullivan) and Mrs. Corney (Mary Clare). Oliver (John Howard Davies) is innocently good, whereas Mr. Brownlow (Henry Stephenson) is a man of good will. Nancy (Kay Walsh) and, to a lesser extent, the Artful Dodger (Anthony Newley) are potentially good people who have been corrupted by evil. The performers are all beautifully cast, especially Davies as Oliver: He's just real-looking enough in the role that he doesn't become saccharine, the way some prettier Olivers do. This is Lean in what I think of as his great period, when he was making beautifully filmed movies with just the right measure of sentiment: Brief Encounter (1945) and Great Expectations (1946) in addition to this one. But he would be bit by the epic bug while working on The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and its success would betray him into bigger but not necessarily better movies: Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), and the rest of his later oeuvre would have the same attention to visual detail that make his early movies so rich, but they seem to me chilly in comparison. Here he benefits not only from a perfect cast, but also from Guy Green's photography of John Bryan's set designs. There are probably few more terrifying scenes in movies than Sikes's murder of Nancy, which sends Sikes's dog (one of the most impressive performances by an animal in movies) into a frenzy. Running it a close second is Sikes's death, seen from a vertiginous rooftop angle. We don't actually see the death, but only the swift tautening of the rope as he plunges, punctuated by a sudden snap. The film is not as well known in America as in Great Britain: Guinness's portrayal of Fagin elicited charges of anti-Semitism, especially since the film appeared so soon after the world learned about the Holocaust. Guinness doesn't play to Jewish stereotypes, but Fagin's absurdly exaggerated nose (which makeup artist Stuart Freeborn copied from George Cruikshank's illustrations for the novel) does evoke some of the caricatures in the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer. The film was edited to remove some of the shots of Fagin in profile, and was held from release in the United States until 1951.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Candy Man" is a masterclass in pop craftsmanship, blending Sammy Davis Jr.’s exceptional vocal talent with a vibrant arrangement, catchy melody, and imaginative lyrics.

youtube

Its polished production and emotional resonance make it a high-quality piece that balances accessibility with artistic depth. The song’s technical excellence and infectious energy solidify its status as a timeless classic.

Sammy Davis Jr.'s vocal delivery in "The Candy Man" is a standout feature, showcasing his versatility and charisma. His smooth, vibrant tone carries the song’s whimsical melody with effortless charm, infusing it with warmth and playfulness. The controlled vibrato and dynamic phrasing, particularly in the soaring choruses, elevate the song’s lighthearted tone while maintaining emotional depth. Davis’s ability to convey joy without over-singing ensures the performance feels authentic and engaging, making it a definitive rendition despite his initial reluctance to record it.

The arrangement, produced by Mike Curb and Don Costa, is meticulously crafted to complement the song’s fantastical theme. The lush orchestration, featuring bright strings, cheerful brass, and a steady rhythm section, creates a buoyant, almost cinematic soundscape. The backing vocals by the Mike Curb Congregation add a layer of harmonic richness, reinforcing the song’s uplifting vibe. The instrumentation strikes a balance between sophistication and accessibility, with subtle flourishes like the sparkling celesta and woodwinds enhancing the fairy-tale quality without overwhelming the melody.

Written by Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse for Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, the lyrics are deliberately whimsical, painting vivid, imaginative imagery (e.g., “sprinkle it with dew,” “wrap it in a sigh”). The playful metaphors and rhythmic flow make the song memorable and singable, though some may find the saccharine tone overly simplistic. The lyrics’ strength lies in their ability to evoke a dreamlike world, aligning perfectly with the song’s purpose as a celebration of sweetness and wonder.

The melody is catchy and instantly recognizable, built on a simple yet effective structure that alternates between gentle verses and a rousing, anthemic chorus. Its sing-song quality ensures broad appeal, while the harmonic progression, rooted in classic pop standards, provides a timeless feel. The use of major keys and uplifting chord changes reinforces the song’s optimistic tone, making it feel like a musical ray of sunshine.

The production is polished yet retains a warm, organic quality typical of early 1970s pop. The mix prioritizes Davis’s vocals, allowing them to shine while the instrumentation provides a supportive backdrop. The clarity of each element—vocals, backing harmonies, and orchestra—demonstrates a high level of technical skill, ensuring the song feels cohesive and vibrant. The subtle dynamics, such as the gradual build in intensity toward the chorus, add depth without sacrificing the song’s lighthearted essence.

The song’s emotional impact lies in its unapologetic joy, delivering a sense of carefree delight that resonates universally. Artistically, it stands as a testament to Davis’s ability to transform a seemingly trivial piece into a cultural touchstone. The combination of his charismatic delivery, the vivid arrangement, and the imaginative lyrics creates a cohesive artistic statement that transcends its origins as a movie tie-in.

The song’s quality is evidenced by its enduring popularity and adaptability across contexts, from its chart-topping success in 1972 to its use in modern media. Its clean production and universal themes allow it to remain fresh, while its versatility enables it to evoke different moods, from whimsical in family-friendly settings to eerie when juxtaposed in darker contexts like horror films. This flexibility underscores the strength of its composition and execution.

Year: 1972

Composition/Lyrics: Leslie Bricusse, Anthony Newley

Producer: Mike Curb, Don Costa

youtube

youtube

#music#music review#review#70s#70s pop#big band#Sammy Davis Jr#Willy Wonka#Leslie Bricusse#Anthony Newley#Mike Curb#Don Costa#Mike Curb Congregation#Easy Listening#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Week ending: 3rd August

Well, another week, another three songs - two from artists I would probably recognise by voice at this point, and one from an artist I'd never heard of - or is it his shameless American knock-off?

If She Should Come to You - Anthiny Newly (peaked at Number 4)

This song tracks with everything I've ever thought about Anthony Newley. It's not bad, but there's a tentativeness, a hesitancy about it, as the song rolls along in a lovely lilting 6/8, Anthony's voice a picture of slightly useless melancholy - he sounds sad, but in a glum, wistful way, not in a downright dramatic, "bawling my eyes out" way.

The concept's simple, but unusual for a song, a warning passed on from Anthony, advising the listener that if she should come to you / Be gentle / For she is very, very shy. Don't ever act unsentimental, he continues, She won't to stay then / She'll run far away then. This mystery woman, only referred to as "she", is apparently wonderful - the sort of girl you'd regret losing. Crucially, Anthony never quite comes out and says that it's a song about his ex - you're left to kind of assume it, but it's never outright stated. If she should come to you / Be tender / You must take care / Or love will die, he sings, though, and you just know he's singing from experience.

Which makes the whole song a funny thing - not a "where did I go wrong" lament, or even a "my life sucks now" bit of wallowing. Anthony's fully accepted that he didn't take good enough care of his lady, he's not trying to get her back, or to wallow in self-pity. Why, exactly, he's giving this advice, that's a bit of a mystery - is it out of some charitable impulse towards the person he's addressing? Or does he just want his love to end up with sombody who'll treat her right? There's something romantic, if so, but also something a little bit sad and spineless about it - you kind of wish that the song would end with Anthony deciding to give it another try himself. But no. I don't know exactly what he did to mess up this relationship, but apparently he's resigned to it being over, for good. Which does add some nuance to the charts that we haven't really had for a while. But still, I can't bring myself to fully sympathise with Anthony, here. You clearly have done some reflecting and realised what went wrong - time to make it right, bro!

(Irrelevant side note, but I thought midway through the first listen that this could also be a song about befriending a flighty stray cat, and that is 100% a charming thought that I'm glad I had).

When Will I Be Loved - The Everly Brothers (4)

This song, at least on the surface, has everything that If She Should Come To You didn't - it's got bite, it's got attitude and it's even got a bit of whininess to it. None of Anthony's politely resigned pining, here, the Everlys have been unlucky in love, and rather than moping about it, they're here to make it everybody else's problem, complaining about how I've been made blue / I've been lied to, and how whenever they meet a nice girl, she always breaks my heart in two, it happens all the time. All this peaks as they ask us, over and over, with a touch of confused to it, when will I be loved?

All this is tied up in a very solid, rollicking rockabilly track, with a lovely bit of chugging guitar in the intro, and a solid bassline that pulls you through the whole song. The guitar work, in general, is great, actually, giving the track a real country twang that was absent from songs like Cathy's Clown. Plus you've also got some absolutely fabulous drumming leading into the choruses, amping it up and giving the chorus a sense of energy and drive. The overall effect's a solid country-flavoured rock vibe, and I like it a lot. It's since been covered by a bunch of artists including Linda Ronstadt, and I can see why. Solid stuff.

The whole thing was apparently inspired by Phil Everly's on and off relationship with one Jackie Ertel-Bleyer, stepdaughter of the founder of their record label's founder, Archie Bleyer of Cadence Records. Interestingly, though, the Everlys had just moved record label away from Cadence, when this came out - we already heard the results of this in Cathy's Clown, which was playing around with a less country, more pop sound. Encouraged by the success of that song, Cadence Records then released several tracks that they had stored away in their vault, including this one. That's why it sounds a bit more rockabilly, and a bit less pop-oriented - it was literally recorded before the move, and only just released now, months later. People clearly liked it, so smart move, I guess, Cadence!

Look for a Star - Garry Mills (7)

Garry Mills is another of those artists I have absolutely zero mental image of. He's got an aggressively normal name, but a pleasant enough voice, and the lyrics to this song are actually quite sweet, a sort of motivational mantra that wouldn't be out of place in a Disney film. When life doesn't seem worth the living, Garry sings, and you don't really care who you are / When you feel there's no one beside you, / Look for a star. Everyone, you see, has a lucky star, according to Garry, and if you wish on yours, you'll find someone to help you out, be it a rich man, a poor man a beggar, / No matter whoever you are / There's a friend who's waiting to guide you / Look for a star. Tell me that's not just bargain basement Pinnochio. Tell me.

It's so Disney-like, in fact, that I was shocked to discover that it's actually from a horror film, called Circus of Horrors, a rather low-budget British flick featuring, and I quote, "a deranged plastic surgeon who changes his identity after botching an operation, and later comes to gain control of a circus that he uses as a front for his surgical exploits". I can find absolutely no record of how Look for a Star fitted into all this, as it doesn't at all seem to fit with the plot of the film - I don't even know who's supposed to be singing it! The film, however, does seem to have been a hit in the UK, despite critics complaining about the rather gratuitous amounts of violence involved. Not sure I'd have gone to see it, but that's a taste thing, more than anything.

Intriguingly, the film was also a surprise hit in the US - this wasn't something that the film company had apparently planned for, and as such, the Garry Mills version of the song was only released in the UK, not the US - or it didn't chart in the US, in any case, and only saw limited airplay. Instead, the hit version in the US was swooped by another artist, Buzz Cason, who hilariously decided to release it under the pseudonym "Garry Miles" in order to capitalise on Mills' success. Which is sneaky enough that I'm honestly shocked it was legal. Truly, the 1960s seem to be the Wild West when it comes to copyright claims and royalties. I think that's what fosters all the covers we've seen, until now - certainly I'm not finding records of many fights over royalties and rights. Whereas I'm pretty sure if you tried to pull a "Garry Miles" today, you'd be sued halfway into the next calendar year before you could even say "lawsuit". Either that, or you'd be forced to sign away pretty much the entirety of the royalties. I do kind of wonder when this kind of wrangling becomes standard practice - look up modern charting hits, and it's a huge deal, but I've no clue what prompted it, or when it became standard practice. Something to keep an eye out for, I guess.

I liked all three songs, but one was a cut above the rest, just in terms of quality, and in terms of the lyrics not annoying me. Anthony and Garry, at the end of the day, were just a bit too passive and resigned to their fates. Give me the Everlys disgruntlement any day.

Favourite song of the bunch: When Will I Be Loved

0 notes

Photo

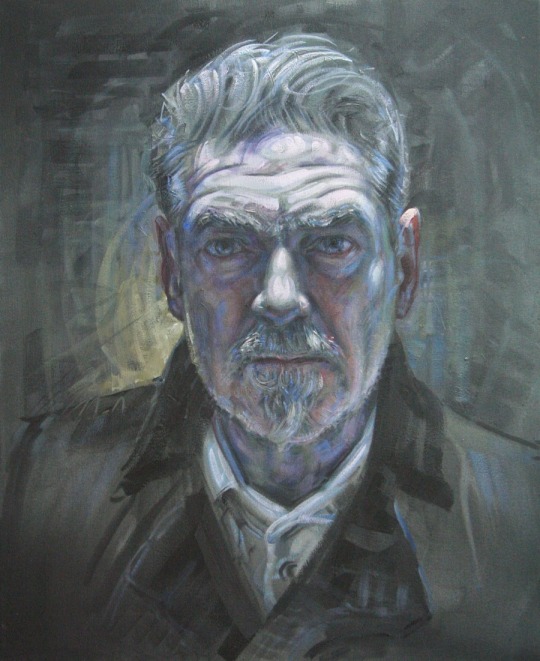

Kenneth Branagh by Alexander Newley

Branagh is pictured as Leontes in The Winter's Tale.

The artist, Sacha Newley, is a well-known and sought-after portraitist, who happens to be the son of Anthony Newley and Dame Joan Collins.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waking up to a new morning...

The Observer, Sunday 15 September 2002

Written by Amy Raphael

After the booze, coke, crack and smack, Suede's Brett Anderson is back in the land of the living with renewed optimism and a new album

Brett Anderson grew up hanging around car parks, drinking lukewarm cans of Special Brew and taking acid. Occasionally, he caught the train from Hayward's Heath to Brighton, less than half an hour away, but still a world away. He would buy punk records and, perhaps, a Nagasaki Nightmare patch to sew on to his red ski jacket.

His mother, who died in 1989, was an aspiring artist; his father was mostly unemployed and obsessed with classical music. He wanted his son to be a classical pianist, but Brett had other ideas. Lost in suburban adolescence, he was drawn to the Smiths, to Morrissey's melancholic lyrics, his eccentric persona. He wanted to be a pop star; he would be a pop star. He had no doubt.

Anderson moved to London in the late 1980s, living in a small flat in Notting Hill. He studied architecture at the London School of Economics, but only while he got a band together. Here he met Justine Frischmann and, with old school friend Mat Osman, formed Suede in the early Nineties as an antidote to grunge and anodyne pop.

Anderson borrowed Bowie's Seventies glamour and a little of his Anthony Newley-style vocals. He looked to the Walker Brothers's extravagant, string-laden productions and appropriated Mick Jagger's sexual flamboyance for his stage show. Yet Suede were totally original, unlike anything else at the time. Dressed in secondhand suits and with casually held cigarettes as a prop, Anderson wanted to write pop songs with an edge; sleazy, druggy, urban vignettes which would sit uncomfortably in the saccharine-tinged charts.

Like his lyrics, Anderson was brash, cocky, confident. He talked of being 'a bisexual man who's never had a homosexual experience', realising it was an interesting quote, even if he knew he would probably always lose his heart to the prettiest of girls.

When I first met him, in the spring of 1993, Suede were enjoying their second year of press hysteria, of being endlessly hailed as the best new band in Britain. Fiddling with his Bryan Ferry fringe, Anderson asserted: 'I am a ridiculous fan of Suede. I do sit at home and listen to us. I do enjoy our music.'

He talked about performing 'Metal Mickey', the band's second single, on Top of the Pops. 'When I was growing up, Top of the Pops was the greatest thing, after tea on a Thursday night... brilliant! You get a ridiculous sense of history doing it. It was a milestone in my life; it somehow validated my life, which is pathetic really.'

By rights, Suede should have been not only the best band in Britain but also the biggest. Yet it did not happen that way. During the recording of the second album, the brilliant Dog Man Star, guitarist Bernard Butler walked out. It was as though Johnny Marr had left the Smiths before completing Meat Is Murder. The band could have given up, but they did not; they went on to make Coming Up, which went straight to the top of the album charts. Then, three years ago, disaster struck during the recording of Suede's fourth album, Head Music. Anderson was in trouble: the pale adolescent who had swigged Special Brew in desolate car parks was now a pop star addicted to crack.

Brett Anderson sits in a battered leather Sixties chair in the living-room of his four- storey west London home sipping a mug of black coffee. He has lived here for three or four years, moving into the street just as Peter Mandelson was moving out. The living-room is immaculate: books, CDs and records are neatly stacked on shelves, probably in alphabetical order.

Anderson's 6ft frame is as angular as ever but more toned than before, the detail of his muscles showing through a tight black T-shirt. Gone is the jumble-sale chic of the early Nineties; he now pops into Harvey Nichols.

He appears to have lost none of his self-assurance but, a decade on from his bold entrance into the world of pop, Anderson has mellowed, grown-up. By his own admission, he is still highly strung and admits he is probably as skinny as a 17-year-old at almost 35 because of nervous energy. But he no longer refuses to listen to new bands in case they are better than Suede; he praises the Streets, the Vines and the Flaming Lips.

This healthy, relaxed person who enjoys the odd mug of strong black coffee is a recent incarnation. At some point in the late Nineties, Anderson lost himself. He became part of one his songs and ended up a drug addict.

He talks about his new regime: swimming, eating well, hardly touching alcohol. No drugs. Did he give everything up at once? 'It was kind of gradual... giving up drugs is a strange thing, because you can't just do it straight away. You stop for a bit then it bleeds into your life again. It takes great willpower to stop suddenly.'

He sighs and looks into the distance. 'I got sick of it really. I felt as though I'd outgrown it. It wasn't something I kept wanting to put myself through and I was turning into an absolute tit. Incapable of having a relationship, incapable of going out and behaving like a normal human being. Constantly paranoid...'

The drug odyssey started with cocaine, but soon it was not enough. 'Cocaine is child's play. After a while, it didn't give me enough of a buzz, so I got into crack. I was a crack addict for ages, I was a smack addict for ages...'

Another deep sigh. 'It's part of my past, really. I'm not far enough away to be talking about it. It's only recently I've been able to say the word "crack".'

When Head Music was being recorded, he says he wasn't really there. He would turn up but his mind was not focused. The album went to number one but it was not up to Suede's standards; as Anderson acknowledges, it was 'flashy, bombastic; an extreme version of the band'.

He laughs, happier to talk about the good times. 'Last year, when I decided not to destroy myself any more, I kind of disappeared off to the countryside with a huge amount of books, a guitar and a typewriter... and wondered what the outcome would be.'

He spent six months alone. It was a revelation to discover that he could spend time by himself. 'I think a lot of people are shit scared of being on their own. Me too. From the age of 14 to 30, I jumped from bed to bed in fear of being alone. Being in the cottage in the middle in Surrey, I learned that if one day everything fucks up, I could actually go and live on my own. It's a total option.'

For a long time, Anderson had avoided reading books, worried that his lyric writing would be affected by other people's use of language. Last year, he decided it was time to fill his head with some new information. Although he had been told for years that his imagery was reminiscent of J.G. Ballard, he read the author for the first time in the cottage - and was flattered. He read Ian McEwan's back catalogue and challenging books such as Michel Houellebecq's Atomised.

Despite his self-imposed exile, it still took Anderson a long time to perfect Suede's fifth album, the self-consciously celebratory A New Morning. The band tried to make an 'electronic folk' album by working with producer Tony Hoffer, who had impressed with his work on Beck's Midnight Vultures. However, unable to make an understated album, they eventually called in their old friend Stephen Street, the Smiths producer.

Yet more trouble was ahead. Anderson says Suede have faced many 'big dramas' over the past decade - Frischmann left the band early on to form Elastica and soon after ended her relationship with Anderson, moving in with Britpop's golden boy, Damon Albarn; Bernard Butler walked out with little warning; the drugs took control - but still the band were not prepared for keyboard player Neil Codling's exit. He was forced to leave in the middle of recording A New Morning suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome.

Anderson says he was furious when Codling left.'He couldn't help it, I know, but I did feel aggrieved. I felt let down. But more at the universe than at Neil. I tend not to show how I feel about these things in public. It's like when Bernard first left, I was devastated. I felt as though that original line-up was really special. And we will never know what might have been.'

At times, Anderson sounds as though he has had an epiphany in the past year. He smiles. 'Well, you only need to listen to A New Morning to realise that. The title is very much a metaphor. It's a very optimistic record; the first single is called "Positivity", for God's sake. It's a talismanic song for the album. It's a good pop single, but we've haven't gone for a Disney kitsch, happy, clappy, neon thing.'

He looks serious for a moment. 'For me, the album is about the sense that you can only experience real happiness if you've experienced real sadness.'

Has he had therapy? His whole body shakes with a strange, high-pitched laughter. 'No! No! But I am happier now. I feel more comfortable with myself. I feel as though I'm due some happiness. I've just started going out with someone I really like. I've made an album which is intimate and warm. I don't any more have the need to be talked about constantly, that adolescent need for constant pampering...'

A swig of the lukewarm coffee and a wry smile. 'And, best of all, I don't feel like a troubled, paranoid tit any more.'

A New Morning is released on 30 September

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Popstand This Weekend!!

With a title of ‘When I’m Sixty Four’, Radio Popstand is on the air this weekend with those multi genre tracks.

But why the title ‘When I’m Sixty Four’, you may be asking? Well, it’s a song written way back in 1967 by Paul McCartney in preparation for Jeffrey’s 64th birthday, which occurs in 2023. Really good of Mr McCartney to write such a song just for me.

My word is Jeffrey really that old? So as a result of this momentous occurrence Radio Popstand will be playing rather a lot of songs from way back in the olden days, the olden days when he was not so old.

But don’t worry there’ll will still be some newer or even brand new tracks, we like to keep up to take here on Popstand, as well as playing the older stuff.

So the oldies come from Lulu and the Luvvers, Neil Diamond, Prefab Sprout, Anthony Newley, The Who, Mike Oldfield, The Rubettes, Cilla Black, Thin Lizzy, LaBelle, The Boomtown Rats, Supertramp, Jimmy Osmond and that’s only a few of those artists from yesteryear.

More up to date artists include Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, KennyHoopla, Dimension, Rita Ora, Disclosure, House of Pain and there are more.

Listen to Radio Popstand today, Saturday, 18:30hrs BST (17:30hrs GMT) and tomorrow, Sunday 08:30hrs BST (07:30hrs GMT) on the Stationhead app, as Jeffrey contemplates the number 64! Don’t forget to link your Spotify or Apple Music premium account to hear the music.

Jeff Wright, 20th May 2023

0 notes

Text

Chocolate factory album cover imagery

CHOCOLATE FACTORY ALBUM COVER IMAGERY MOVIE

the candy man,” also known as “the candy man can,” was written by leslie bricusse and anthony newley for the 1971 film from willy wonka and the chocolate factory. geek music actor singer and composer anthony newley and composer leslie bricusse wrote pure imagination for the 1971 film ~ willy 1971's "willy wonka and the chocolate factory" a funk cover of pure imagination from willy wonka & the chocolate factory, written by leslie bricusse and anthony newley let me know what song i should cover next in the comments.it is a song from the 1971 film willy provided to by symphonic distribution pure imagination (from " willy wonka & the chocolate factory") this beautiful version of the song is from an out of print this video is a rehearsal of an arrangement for trombone and piano of pure imagination. Old Skool Tagalog Reggae Classics Songs 2019 Chocolate Factory ,Tropical Depression, BlakdyakOld Skool Tagalog Reggae Classics Songs 2019 Chocolate Factory ,Tropical Depression, BlakdyakOld. Recording sessions took place mainly at Rockland Studios and Chicago Recording Company in Chicago, Illinois, and the album was primarily written, arranged, and produced by R. music by anthony newley, lyrics by leslie bricusse. Chocolate Factory is the fifth solo album by American recording artist R. An alternative cover edition for this book can be.Charlie and the Chocolate Factory book. vocal gene wilder ~ pure imagination this is one of my favorite songs from willy wonka. Read 79 reviews from the world's largest community for readers. The posts also debuted Fine Line's cover art, which features a fish-eye view of the 25-year-old popstar standing in front of a pink and blue backdrop while striking a major pose in those aforementioned white pants and a fuchsia top cut down to there.įWIW, there's also a gloved hand reaching out to him from the bottom right corner.Leslie Bricusse And Anthony Newley Pure Imagination HdĬomposed by leslie bricusse and anthony newley. Ex-Creedence Clearwater Revival frontman John Fogerty‘s Fogerty’s Factory album, which was issued on CD and digitally in November, gets its vinyl release today.The 12-track collection features mostly of new versions of CCR tunes and Fogerty solo songs that John recorded with his three youngest children sons Shane and Tyler, and daughter Kelsy. The former 1Der revealed on Twitter and Instagram that this new outing will be released on Dec. 4 to announce that his second solo album, called Fine Line, will be coming out before Christmas. He said of the album, I didn’t really feel like recording for eighty per cent of the record.

CHOCOLATE FACTORY ALBUM COVER IMAGERY MOVIE

It was too mechanical and recorded after too many sessions on very little sleep. Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory movie clips: BUY THE MOVIE: Don’t miss the HOTTEST NEW TRAILERS: CLIP DESCRIPTION:Willy Wonka (Gene Wilder) guides the group into a dark tunnel full of strange. To cool the chocolate, the factory had two ice machines that made 4,000 kilos of. Later Prince said that For You didn’t reflect him as a person. Published on the back cover of the magazine D’Ac i d’All, in 1934. OK, so Styles - who dropped his self-titled debut solo album in May 2017 - hit up social media on Nov. Prince’s first album For You was released by Warner in 1978 and got stuck at 163 on Billboard’s Pop Chart. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (film) For. 13 seriously cannot get here fast enough. Chocolate Cosmos The cover of the second tankbon volume of Chocolate Cosmos as published by Shueisha. As in, Daddy, I want Harry's 'Fine Line' album, now! Harry Styles is looking a little like a fierce Oompa Loopa in flowy white pants on the cover and fans are digging it. Harry Styles' 'Fine Line' album cover just dropped and it is giving off some major Charlie & The Chocolate Factory vibes. The video’s description offers that the album’s title and first single are coming soon and that the imagery was designed by Francesco Artusato, who metal fans might know as the guitarist of Light the Torch and ex-All. Stop whatever it is you're doing, because this is big, fam. After months of teasing, Fear Factory have finally released another teaser for their upcoming album, this one a video showing off a section of the cover artwork.

0 notes

Text

How should white jazz navigate Black Lives Matter?

In the US, June 19th is a holiday which has come to be known as ‘Juneteenth’ — it is a commemoration of the end of slavery in 1865. Emancipation did not mean equality and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement last year, and the events that gave rise to it, were a stark reminder of the ongoing inequities and horrific injustice that continues to be experienced by black people in the US and worldwide. Bowden (2002) notes that “Jazz is an American art form – possibly the only one” - and it is an art form where black Americans have led the musical narrative, been the key innovators and inspired generations of jazz musicians worldwide.

9,000 miles away, here in New Zealand, I have spent the past week preparing a set list for a @Jazzicology gig we have been asked to do on July 4th to mark another date in the US calendar - Independence Day - via “A celebration of the great american songbook and the first ladies of jazz”. It has given me cause to reflect on BLM and what its implications are, or should be, for white jazz musicians.

The questions I have been considering seem particularly important for vocalists: our song choices involve both music and words and performance involves taking on the role of the narrator and singing as if from lived experience. Arguably, these same issues do not arise at all, or at least not to the same degree, for instrumentalists, where performing compositions by black artists can only serve as a form of respect and homage. The jazz vocalists who most inspire me – Carmen McCrae, Ella Fitzgerald, Abbey Lincoln, Cassandra Wilson, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone – are all black women. I am drawn to and deeply moved by their singing. Songs of love and loss are common to all cultures and musical genres. But jazz is distinctive in its contribution of songs of discrimination, oppression, slavery – and of the strive for emancipation, quality, power and freedom. Jazz has its roots in the blues and in the tradition of slave songs. Improvisation is central to jazz and Beener (2012) says that jazz ‘models the principles of freedom” and has often documented the ongoing pursuit of emancipation.

Performing songs written for or by black women, as a white privileged woman, feels uncomfortable. Can it be anything other than cultural appropriation? Or can performing these songs serve as a respectful acknowledgement of the experience of black Americans? This is difficult territory. To altogether avoid performing compositions and lyrics highlighting the issues and experiences of black people, in favour of safer territory, is tempting but risks misrepresenting the vocal jazz canon by not performing some of its seminal pieces. But then, can a white woman ever perform such pieces with any degree of authenticity? These issues had already arisen pre-BLM - the 2018 Montreal Jazz Festival in 2018 cancelled ‘SLAV’, a theatre piece that explored slavery and oppression using the medium of black slave songs. Its star was a white singer; four of its six other cast members and the director were also white (Wente 2018).

So how should white jazz vocalists navigate these questions, post-BLM?

There are certain pieces that I have never performed. An example: Strange Fruit – the harrowing song about the lynchings of black people in the South, best known from Billie Holiday’s iconic recording of the piece, but also recorded by others including Nina Simone. I lack the authority of personal or cultural experience to sing it. It just feels wrong to do so - and seemed to me a clear example of appropriating black experience. Yet in exploring further my own reluctance to perform it, I discovered it was composed by Jewish-American teacher teacher and songwriter Abel Meeropol, originally as a poem published in a teacher’s union newsletter in 1937. It was later set it to music by him and his wife who performed it at Madison Square Garden, before Billie Holiday’s well-known recording of it. So maybe it should not be ruled out – although Annie Lennox was criticised for her recording of it, highlighting the pitfalls even for those whose good intentions match those of Meeropol.

But I recognise that I have not consistent in my approach to these issues, because Work Song, the powerful slave song about working on a chain gang, is a number I have performed. It was composed in 1963 by Nat Adderley (Cannonball Adderley’s younger brother) as an instrumental with lyrics added a year later by jazz musician and black activist Oscar Brown Jr, both black jazz musicians. I recall as a child in the 1960s and 70s seeing a riveting performance of it by Nina Simone and it is one of the songs that made me want to be a jazz singer. But I am clearly no better culturally equipped to sing it than I am Strange Fruit. I now question its inclusion in my set lists: to do so because it is musically appealing, and a crowd pleaser, risks trivialising the experiences of black people which it draws on.

But where to draw the line? There are still other numbers that, once you dig into their provenance, also raise questions for me as a white jazz vocalist. An example is Feeling good, another number recorded (in my view unsurpassably) by Nina Simone. Is there a more powerful ode to freedom and emancipation? Yet it was written by English composers Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse for their musical The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd, and performed in UK concert halls in 1964 before making the transition to Broadway. The Wikipedia description of the role of the song in the musical is a bit odd – a character called simply ‘The Negro’ “…is asked to compete against the show's hero ‘Cocky"; but, as "Cocky" and his master "Sir" argue over the rules of the game, "the Negro" reaches the centre of the stage and "wins", singing the song at his moment of triumph”. Still, none of this bothered Michael Bublè or the many others who have recorded this wonderful song.

Maybe there are no rights or wrongs on these question – perhaps it depends on the motivation of the singer, the personal experiences they bring to their own performance, the context which they provide to that performance for the audience, and maybe even on the nature of the audience. I’ll keep reflecting, and questioning my own choices.

Nance Wilson, Queenstown, New Zealand

Nance Wilson is one half of the new jazz duo, Jazzicology, with Mark Rendall Wilson, and has a long-standing collaboration with UK jazz pianist and composer Sid Thomas.

Sources:

Beener (2012) Five Jazz Songs That Speak Of The Freedom Struggle. NPR Jazz.

Bowden M (2002) Quotable jazz. Sound and Vision.

Russonello (2020) Jazz Has Always Been Protest Music. Can It Meet This Moment? New York Times.

Wente (2018) Should white people sing slave songs? Globe and Mail.

0 notes

Text

On the musical dialogue between David R. Jones and Noel S. Engel...

This is David Robert Jones.

You know him better as David Bowie.

And this is Noel Scott Engel.

The chances are slim that you know him, but if you happen to do so, you’ll know him as Scott Walker.

No, not the asshole Wisconsin governor Scott Walker, the singer-songwriter Scott Walker.

And if you’re aware of both of their music, you’ll know that they’ve engaged in one of the greatest musical call and response games in history.

“Start by placing them across the board from each other: two queen’s bishops, rows of squares ahead of them. One is Noel Scott Engel, born in Ohio in 1943, an American who went to Britain for fame and who stayed there; the other is David Robert Jones, born in Brixton on the day before Engel’s fourth birthday, who scrabbled for fame in Britain and, once he finally got it, left for good. Jones became David Bowie, Engel became Scott Walker. Each was precocious, ambitious, beautiful. They first met around 1966 at a London nightclub, The Scotch of St. James, when Walker was a pop star and Bowie nothing but polite aspiration.”

- Chris O’Leary on Nite Flights, from Pushing Ahead of the Dame

So, if you’re a fan of David Bowie and haven’t taken the time to explore the music of Scott Walker, you really should try to do so. Both of their careers have more or less been a musical back-and-forth, each taking inspiration from the other whilst attempting to improve upon the other’s response.

I should say, I feel overwhelmingly unqualified to talk about it, but I’m going to do so anyway.

From his early compositions on his 1966 album through to his rise as the alien rocker Ziggy Stardust, Bowie had been subtly quoting Scott Walker along with all his other influences.

Here’s Bowie doing a cover of Jacques Brel’s “My Death” during his final Ziggy Stardust concert in 1973.

youtube

The reason why Bowie covered that song, and why he even became aware of Jacques Brel in the first place was because of Scott Walker’s 1967 covers of Jacques Brel’s music.

youtube

And before you say, “Wasn’t Bowie made aware from Brel from the Off-Broadway musical Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris?”, the answer is no. Here’s how Bowie discovered Brel...

“In the mid-60s, I was having an on-again, off-again thing with a wonderful singer-songwriter who had previously been the girlfriend of Scott Walker. Much to my chagrin, Walker’s music played in her apartment night and day. I sadly lost contact with her, but unexpectedly kept a fond and hugely admiring love for Walker’s work. One of the writers he covered on an early album was Jacques Brel. That was enough to take me to the theater to catch the above-named production when it came to London in 1968.”

David Bowie’s Favorite Albums by David Bowie, Vanity Fair, 2003

Link to this: here

Hell, Scott had been covering Brel before the musical Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris even premiered. His first solo album, containing three Brel songs, was released in 1967, one whole year before the musical made it’s Off-Broadway premiere.

As if that wasn’t enough proof of Scott’s influence on Bowie, look no further than Diamond Dogs.

The musical triptych “Sweet Thing - Candidate - Sweet Thing (Reprise)” starts off with Bowie hitting the lowest note in his career, as if he was imitating Scott Walker’s deep voice. And if you think that that’s just a coincidence, pay attention to “Future Legend” the spoken word opening of Diamond Dogs.

Family badge of sapphire and cracked emerald

Any day now

The year of the Diamond Dogs

Want to know why “any day now” is the only part of that opening that is sung?

A year before Bowie released Diamond Dogs, Scott Walker released the album Any Day Now and here’s the title track.

youtube

Sounds familiar doesn’t it?

And all that was in the late 60s - early 70s. Bowie rose to fame, taking influences all over from The Stooges and The Velvet Underground to Anthony Newley and Little Richard, as well as Scott Walker.

Bowie’s rise to fame was concurrent to a period of confusion for Scott Walker. His early-70s albums failing to reach the critical acclaim of his early solo work or even his time as part of The Walker Brothers, due to his succumbing to the pressures of his record company.

And as such The Walker Brothers reformed in 1974, all a little older and a little wiser. Their first record since their reformation was something of a flop. Their record company was about to go under and they had enough resources to make one final album.

When you reference someone’s work, you’re not only acknowledging them. You’re also calling out to them, in a way. And that’s what Bowie was doing since his career began, calling out to Scott Walker. But then something unexpected happened.

Scott responded.

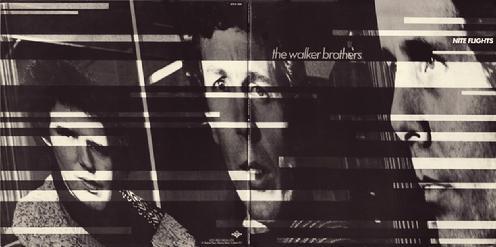

Nite Flights would be The Walker Brothers’ final album. Recorded during early 1978, it was meant to be the group going out with a bang, the trio writing all of their songs and incorporating contemporary music into their compositions.

Walker even bought in albums that he had listened to and wanted to be the jumping off point for Nite Flights. He made everyone in the production listen to them.

What were the albums? Well...

Yeah, he made everyone in the studio listen to Bowie.

Now Scott Walker was taking influence from David Bowie. And with a final cry, The Walker Brothers delivered their last album in July 1978.

Bowie’s influence is heard throughout the whole album. So much so, that the title track, “Nite Flights”, sounds like it predicts Bowie’s 1979 album, Lodger.

Scott’s nods to Bowie are more evident in the musical compositions themselves rather than the lyrics, as evidenced from the title track. But there were still a few overtly lyrical references to Bowie.

For instance, the opening track “Shutout” is a violent clap-back to Bowie’s “Blackout”.

But the most prominent response came in the form of “The Electrician”, penned by Scott Walker himself. Whether it’s an intentional response from Walker or not, the song feels like both an assessment and a one-upping of Bowie’s pseudo-imitation of him on “Sweet Thing”.

youtube

Yeah. It’s one hell of a song, eh?

In fact, Bowie thought so too when he was recording Lodger in 1978 and he listened to it for the first time.

As Chris O’Leary from the Bowiesongs blog writes...

“Bowie was stunned. One can’t blame him. Imagine if a great stone face to whom you’ve been making offerings for years suddenly rumbles up a response, in an approximation of your voice.”

And this is just the start of this musical back and forth. There’s also the thematic influences that Bowie had taken from Scott in the 60s, Bowie’s translation of the Brel songs via Scott, and I won’t even get into their late-90s work. Honestly, just read the Bowiesongs article that I linked at the start of this post. It goes into better and clearer depth, than I could ever hope to achieve.

David Bowie and Scott Walker are artists intertwined, each approaching their craft with the same desires, yet following through with different philosophies. One reaching his own avant-garde popularity, the other enjoying his renowned obscurity. Their inspiration game is one of the most underrated and obscure stories in music history. And I must say, that as a fan of both, it produced some damn fine music.

So, to all Bowie fans reading this, please, please take the time to try and explore the music of Scott Walker. Besides having one of the strangest career trajectories in all of pop music, you can hear Scott Walker’s faint whispers in Bowie’s music. And if you listen closely, you can hear a bit of Bowie in some of Walker’s music.

And if you need any more of a reason to listen to Scott Walker, here’s Bowie finally being able to respond to “Nite Flights” in 1993.

youtube

Here’s to you Engel and Jones!

#David Robert Jones#David Bowie#Noel Scott Engel#Scott Walker#the singer-songwriter not the Wisconsin governor#Nite Flights#only one way to fall#I love these two so much#Their music is sublime#And the influence game that they had throughout their careers is beautiful#and more people should at least try and listen to Scott Walker's music#I know hardly anyone is going to see this post#But it needs to be made#Because there are so many Bowie fans on this site#But so so few Scott Walker fans#And while I'm at it#Wisconsin governor Scott Walker can get screwed

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Join me now on THE PENTHOUSE @ http://www.thepenthouse.fm

for EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN Radio Show. I’m spinning these great artist now PETER ALLEN, GILBERT PRICE, JOHNNNIE RAY, DORIS DAY, JOHN LEGEND, BARBARA COOK, ROSEMARY CLOONEY &

TONY PASTOR, STEVE LAWRENCE & EYDIE GORME, JOHN LENNON & YOKO ONO, MICHAEL FEINSTEIN, ANTHONY NEWLEY, NINA SIMONE, NEW ORLEANS HIGH SOCIETY, JUDY GARLAND, JESSICA MOLASKEY, FRANK SINATRA, MARGARET WHITING, NAT KING COLE, DIANH WASHINGTON, CHET BAKER, MARCUS GOLDHABER, JIMMY McHUGH, JOHN COLTRANE till 11PM. Spread the word!

0 notes

Text

Week ending: 13th April

Back to a more manageable number of songs this week, thank goodness - and it's two returning artists, including one we really haven't heard from for quite some time. Will Elvis have lost his edge? Or will he have come back from the army with a new sound locked and loaded? I guess we'll find out, after this first song...

Do You Mind? - Anthony Newley (peaked at Number 1)

Anthony's a fairly recent chart fixture, but we've had quite a few of his songs, and he's got a definite vibe laready - he does rock and roll, but with a really distinctive, careful-sounding voice, and a kind of reserve. And you've got all that in bucketfuls here, as Anthony asks you oh-so-politely if I say I love you / Do you mind? / Make an idol of you / Do you mind? He really wants to lavish affection on you, but only if you don't mind. If you do mind, just let him know, and he'll stop. It's the sort of thing that could come off as a bit flippant, but there's a feeling of earnest sincerity to Anthony's voice here. You really do get the feel that if you minded, he probably would back off. It's sweet.

There are also all these little vocal touches that I quite like, here, from the slightly unsteady wobbles on longer notes, to the cute little if I say I love yah bit, to the way his voice his voice creaks slightly on the sweet nothings line. They're small things, hard to pin down, but they all give a sort of vulnerability and authenticity to it all. Anthony's no showboating honey-voiced idol, he's got a voice that sounds "real". And all that's complemented by a relatively minimal accompaniment that's mostly just a steady finger-snapping and some little guitar touches, all mixed fairly quietly in the background, the better to let Anthony's voice stand out above it.

The whole thing was written by one Lionel Bart, whose name seemed familiar to me - and indeed, after a bit of research, it turns out that he was the songwriter behind the musical Oliver, and also behind some less glorious songs that we've already, such as Little White Bull (yikes) and Living Doll (also yikes). But yeah, he was mostly a writer for musicals, and yes, if you squint I reckon there is something rather musical theatre-lite about Anthony's style, with its emphasis on character and emotion, and little clever lyrical turns, like "kisses" rhyming with "this is".

Stuck on You - Elvis Presley (3)

And then, the return of the King - after two years of military service, and only one or two new songs, Elvis is back, and he's back with a bang, with a goofy romp that's got everything you'd expect from an Elvis record. You've got a chugging, bluesy piano and guitar beat, you've got Elvis' classic uh-huh-huh ad libs, you've got lyrics about just being head-over heels in love, all of it wrapped up in a metaphor about how I'm gonna stick like glue / Because I'm stuck on you. The rhythm and the little pause Elvis does on the title lyric are more than a little reminiscent of All Shook Up. And of course, you've got lots of little folksy similes illustrating it all, moments where Elvis promises to squeeze you tighter than a grizzly bear, or compares splitting him and his love up to trying to take a tiger from his daddy's side - simply not possible, if the tiger isn't willing. So yes, this is a very typical Elvis record, and it's fine. Good fun, even.

In some ways this is interesting, too, because Elvis has been out of the game for two years - and in the meantime, pop and rock and roll music has changed, with a rise in more consciously "teenage" songs and teen idols, plus an increased amount of softer, gentler pop songs. There are other smaller changes, too, including but not limited to the sort of guitar sounds you're hearing and an increase in Buddy Holly-style pizzicato strings. And yet, in the face of all of this, Elvis turns in a track that's basically "same old same old". And it works - this song goes to Number 3 in the UK and Number 1 in the US, and the excitement around Elvis' return more generally is such that his train from New Jersey, where he left the army, to Tennessee got mobbed by fans, and Elvis had to keep getting out to appear and appease the fans. So yeah, Elvis didn't need to do anything new or groundbreaking to sell records, it seemed - leave the innovation for other artists, Elvis has his niche, and it works, people are clearly going for it.

And yet, for all that it is well-made, I'm not personally so thrilled about this one. Partly that's just because it sounds like literally every other Elvis number. It's got energy, but not too much energy, Elvis is giving it welly, but not too much welly, it's fast, but not too fast, and the whole just things sounds a bit like an off-brand version of All Shook Up. I genuinely had to check this wasn't a repeat, that's how familiar it feels. There's nothing wrong with Stuck On You, but there's not much that makes it stand out from literally everything else Elvis did. Which is a shame, for Elvis' triumphant return from the army, but there you have it.

I didn't mind either of this week's songs, but I think the newcomer has to take it, over the returning veteran - I was charmed by Anthony's performance, and I liked how different he sounds to everyone else out there. Meanwhile, Elvis has come back to a world where everyone's already doing a pretty credible Elvis impression, and has decided to join the ranks with a mid-tempo, meh kind of song. It's not bad, but it's definitely the less interesting listen, this week. So...

Favourite song of the bunch: Do You Mind?

0 notes

Photo

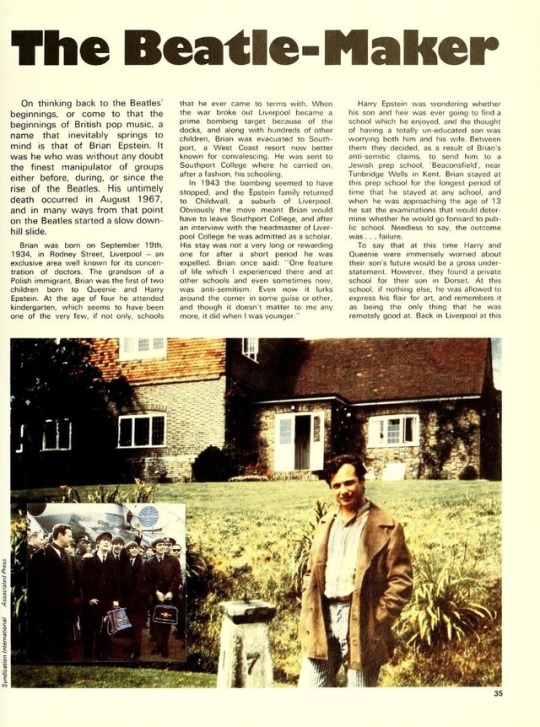

Chapter on Brian Epstein from ‘The Beatles: The Fabulous Story of John, Paul, George and Ringo’ by Robert Burt & Jeremy Pascall [1975]

The Beatle-Maker

On thinking back to the Beatles’ beginnings, or come to that the beginnings of British pop music, a name that inevitably springs to mind is that of Brian Epstein. It was he who was without any doubt the finest manipulator of groups either before, during, or since the rise of the Beatles. His untimely death occurred in August 1967, and in many ways from that point on the Beatles started a slow down-hill slide.

Brian was born on September 19th, 1934, in Rodney Street, Liverpool - an exclusive area well known for its concentration of doctors. The grandson of a Polish immigrant, Brian was the first of two children born to Queenie and Harry Epstein. At the age of four he attended kindergarten, which seems to have been one of the very few, if not only, schools that he ever came to terms with. When the war broke out Liverpool became a prime bombing target because of the docks, and along with hundreds of other children, Brian was evacuated to Southport, a West Coast resort now better known for convalescing. He was sent to Southport College where he carried on, after a fashion, his schooling.

In 1943 the bombing seemed to have stopped, and the Epstein family returned to Childwall, a suburb of Liverpool. Obviously the move meant Brian would have to leave Southport College, and after an interview with the headmaster of Liverpool College he was admitted as a scholar. His stay was not a very long or rewarding one for after a short period he was expelled. Brian once said: “One feature of life which I experienced there and at other schools and even sometimes now, was anti-semitism. Even now it lurks around the corner in some guise or other, and though it doesn’t matter to me any more, it did when I was younger.”

Harry Epstein was wondering whether his son and heir was ever going to find a school which he enjoyed, and the thought of having a totally un-educated son was worrying both him and his wife. Between them they decided, as a result of Brian’s anti-semitic claims, to send him to a Jewish prep school, ‘Beaconsfield’, near Tunbridge Wells in Kent. Brian stayed at this prep school for the longest period of time that he stayed at any school, and when he was approaching the age of 13 he sat the examinations that would determine whether he would go forward to public school. Needless to say, the outcome was... failure.

To say at this time Harry and Queenie were immensely worried about their son’s future would be a gross understatement. However, they found a private school for their son in Dorset. At this school, if nothing else, he was allowed to express his flair for art, and remembers it as being the only thing that he was remotely good at. Back in Liverpool at this time, Harry Epstein was trying hard to find a good school for Brian before it was too late. His hard work bore fruit, for in the autumn of 1948, just as Brian had turned 14, he was notified that his son was to attend Wrekin College, in Shropshire.

At Wrekin, Brian discovered that he had another talent besides art. He took part in school plays and found that his performances were being praised by the teachers. It must have been the only thing young Epstein was praised for, and before he had the opportunity to sit any examinations he decided he wanted to leave school and become a dress designer. Brian might have wanted to become a dress designer but his parents had other ideas, and on September 10th, 1950, aged very nearly 16, he started his first job as a sales assistant at the family’s local furniture store.

He started work at £5 a week, which really wasn’t a bad wage at that time, and slowly but surely built up some kind of interest in his work. His parents were pleased as this was the first time in his life that he had shown concern for anything. Mr. and Mrs. Epstein were satisfied and happy with their eldest son. Things were on the up and up for Brian.

On December 9th, 1952, as though he hadn’t gone through enough discipline of one sort or another, a buff envelope arrived through the door notifying him that he was to attend a National Service medical. (In those days National Service was compulsory). He passed his medical as an A.1., the only A.1. achievement he had ever received. And so he began his two years’ service as a clerk in the Royal Army Service Corps.

Secure Businessman

Within 10 months of joining the army his nerves became seriously upset. He reported to the barrack doctor, and after a thorough examination he was passed on to a psychiatrist. After four psychiatric opinions they came to the conclusion that Private Epstein was just not fit for military service - and discharged him.

He arrived back in Liverpool prepared to work very hard at the furniture trade. This he did, and seemed to settle into some kind of routine way of life. His parents were happy. For no apparent reason at this time Brian’s old love for acting returned, and he regularly attended the Liverpool Playhouse. He began to meet the actors socially, and started toying with the idea of acting as a profession. With the encouragement of the professionals Brian got himself an audition at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, and after reading two pieces, excerpts from ‘Confidential Clerk’ and ‘Macbeth’, he was accepted to begin studies as from the next term. So at 22, although a secure and aspiring businessman, he submitted himself once again to the rigours of community life, and became a student at R.A.D.A. It didn’t take Brian too long to realise that studying just wasn’t his forte, and he went back, once again, to the furniture business - where it now seemed that he was going to spend the rest of his working life.

The Epstein’s store was at this time expanding, and they opened another branch in the city centre. Included in this branch was a record department which Brian took charge of. Anne Shelton opened the store, and from that first day it began to flourish. Although most of the records Brian sold were pop, his real interest lay in classical and his favourite composer was Sibelius.

In 1959 the Epstein’s opened yet another store, this time in the heart of Liverpool’s shopping centre and opened by Anthony Newley. By autumn 1962 Brian’s store, for he was in complete charge of the city centre branch, was running to absolute perfection.

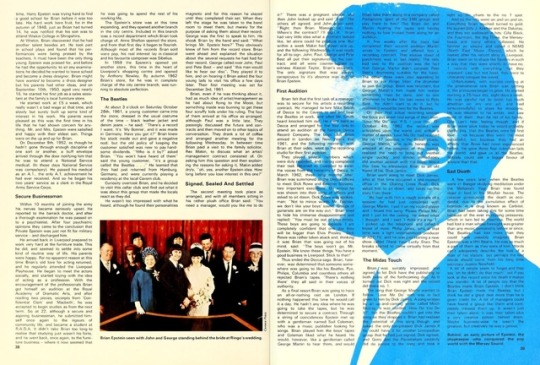

The Beatles

At about 3 o’clock on Saturday October 28th, 1961, a young customer came into the store, dressed in the usual costume of the time - black leather jacket and denim jeans - he said: “There’s a record I want. It’s ‘My Bonnie’, and it was made in Germany. Have you got it?” Brian knew his stock inside out and gave a negative nod: but the old policy of keeping the customer satisfied was now to pay handsome dividends. “Who is it by?” asked Brian. “You won’t have heard of them” said the young customer, “it’s a group called the Beatles...” He learned that they had just returned from Hamburg, Germany, and were currently playing a residency at the local Cavern club.

Curiosity overtook Brian, and he decided to visit this cellar club and find out what it was about this group that made the locals react as they did.

He wasn’t too impressed with what he heard, although he found their personalities magnetic and for this reason he stayed until they completed their set. When they left the stage he was taken to the band room to meet them, but merely for the purpose of asking them about their record. George was the first to speak to him. He shook Brian by the hand and said: “What brings Mr. Epstein here?” They obviously knew of him from the record store. Brian went ahead and explained the situation about the several requests he had had for their record. George called over John, Paul and Pete Best - and said “this man would like to hear our disc”. They played it to him, and on hearing it Brian asked the four young lads to visit his office a few days later. Their first meeting was set for December 3rd, 1961.

Brian, even if he was thinking about it, had as much idea of artist/management as he had about flying to the Moon, but something inside was burning to get these four scruffy kids under his ruling. The four of them arrived at his office as arranged, although Paul was a little late. They passingly discussed the future and contracts and then moved on to other topics of conversation. They drank a lot of coffee and arranged another meeting for the following Wednesday. In between time Brian paid a visit to the family solicitor, Rex Makin, to discuss what an artist/management contract consisted of. On asking him this question and then explaining the reasons for asking it, Makin added dryly, “Oh, yes, another Epstein idea. How long before you lose interest in this one?”

Signed, Sealed And Settled

The second meeting took place as arranged, and with all members sitting in his rather plush office Brian said: “You need a manager, would you like me to do it?” There was a pregnant silence, and then John looked up and said “Yes.” The others all agreed, and John again said: “Right then Brian. Manage us, now. Where’s the contract? I’ll sign it.” Brian had very little idea what a contract looked like, let alone could he produce one. But within a week Makin had drawn one up, and the following Wednesday it was ready for all to sign. John, Paul, George and Pete Best all put their signatures to the contract, and all were counter-signed by witness Alastair Taylor, Brian’s assistant. The only signature that was always conspicuous by it’s absence was that of Brian Epstein.

First Audition

Brian felt that the first task of a manager was to secure for his artists a recording contract. He managed to lure Mike Smith of Decca to the Cavern to see and hear the Beatles at work, and what Mr. Smith heard knocked him out. He went back to Decca and arranged for the four lads to attend an audition at the famous Decca Record Company. The boys plus Brian arrived in London on New Year’s Eve, 1961, and the following morning, with Brian at their sides, went to the recording studio for their first audition.

They played several numbers which were duly recorded, and having completed their task returned to Liverpool to await the voices from the hierarchy of Decca. In March 1962, three long months later, Brian was summoned to the Decca offices to meet Dick Rowe and Beecher Stevens, two important executives. On arrival he was shown into their suite of offices and asked to sit down. Dick Rowe was spokesman: “Not to mince words Mr. Epstein, we don’t like your boys’ sound. Groups of guitarists are on the way out.” Brian tried to hide his immense disappointment and replied: “You must be out of your minds. These boys are going to explode. I am completely confident that one day they will be bigger than Elvis Presley.” Dick Rowe was rather taken aback and, thinking it was Brian that was going out of his mind, said: “The boys won’t go, Mr Epstein. We know these things. You have a good business in Liverpool. Stick to that!”

Thus ended the Decca saga. Brian, however, was determined that someone somewhere was going to like his Beatles. Pye, Philips, Columbia and countless others all rejected Brian’s tapes. ‘There’s nothing there’ they all said in their voices of authority.

As a final resort Brian was going to have an all-or-nothing raid on London. If nothing happened this time he would call it a day. He hadn’t any idea where he was going to take the tapes, but he was determined to secure a contract. Through a string of coincidences Epstein met up with a gentleman named Syd Coleman, who was a music publisher looking for songs. Brian played him the boys’ tapes and Coleman liked what he heard. He would, however, like a gentleman called George Martin to hear them, and would Brian take them along to a company called Parlophone (part of the EMI group) and play them to him? This Brian did, and Martin hearing the tapes and having nothing to lose invited them along for an audition.

A few weeks after the boys had completed their second audition Martin wrote to Epstein and offered him a recording contract. That elusive sheet of parchment was at last reality. The only bad side to the audition was the fact that George Martin didn’t consider Pete Best’s drumming suitable for the band. The other three were also appealing to Brian to ask Ringo Starr, the drummer to join the group. Brian was reluctant, but George Martin’s hint made him realise something must be done, and so one afternoon he broke the bad news to Pete Best. He didn’t want to do it, but he realised it would be best for the Beatles.

On their first actual recording session the boys put down two songs of their own: ‘Love Me Do’ and ‘P.S. I Love You’. On October 4th, 1962 the record was unleashed upon the world, and within a matter of weeks ‘Love Me Do’ had reached the no. 17 position in the British charts. George Martin, who quite honestly was amazed at the progress of this record, realised the need to bring out another single quickly, and almost immediately did another session with the boys. About this time he introduced Brian to an old friend of his, Dick James.

Brian went along to meet Dick James, who at that time occupied a one-roomed office in the Charing Cross Road. Dick asked him to sit down, and takes up the story from there:

“He had with him a rough acetate of a session he had just completed with George Martin. I put it on my record player and I heard this song ‘Please Please Me’, and I just hit the ceiling. He asked what I thought, and I said ‘I think it’s a no. 1.’, I picked up the telephone and called a friend of mine, Philip Jones, who at that time was a light entertainment producer at ABC TV, and he was just starting a new show called Thank Your Lucky Stars. The breaks started to come virtually from that moment.”

The Midas Touch

Brian was suitably impressed, and agreed to let Dick have the publishing to both sides of the forthcoming disc. As it turned out Dick was right and the record did make no. 1.

The song that George Martin wanted to follow ‘Love Me Do’ with was in fact given to him by Dick James. A song written by an up-and-coming writer called Mitch Murray, it was entitled ‘How Do You Do It?’, but the Beatles couldn’t get into the song so they dropped it. Brian had realised the potential of this song though, and asked the only-too-pleased Dick James if he could have it for another Liverpudlian group that he had just signed. Dick agreed, and Gerry and the Pacemakers certainly did do justice to the song and took it right up the charts to the no. 1 spot.

And so the hits went on and on and on. Everything Brian touched turned to gold. He signed Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas, and they too wallowed in hits. Cilla Black, the Fourmost, the Big Three, the Merseybeats and many others followed. He formed an empire and called it NEMS (North East Music Stores), which he named after his record shop in Liverpool. Brian went on to shape the Beatles in such a way that they were shortly to have no. 1 records with everything that they released. Last but not least, they were to ultimately conquer the world.

Unfortunately, with the success coming at the phenomenal rate Brian was getting it, the pressures began to grow. He started working a 25-hour day, eight days a week. He was careful not to lavish too much attention on any one act, and tried (unsuccessfully) to share his devotions. He was devoted to his artists, and saw more of them than he did of his family. One can’t help feeling though, and if Brian were alive today he would probably clarify this, that the Beatles were his first love - not because they were the most successful, but because they had an affinity that Brian had never experienced before. He gave these four suburban lads the world, and gave us all the Beatles, Nobody could ask a bigger favour of anyone than that.

Sad Death

A few years later, when the Beatles were in Bangor studying meditation under the Maharishi Yogi, Brian was found dead in bed in his Mayfair house. The coroner pronounced the death as accidental, due to the cumulative effect of bromide in a drug known as Carbitol. Brian had been taking this for some time because of the ever increasing pressures, which in turn led to insomnia. The world had lost a man whose foresight was greater than any music personality before or since. The Beatles had lost more than they could have possibly imagined. Brian Epstein was a fifth Beatle. He was as much a part of them as they were of him. Words can’t adequately describe the loss of a man of his stature, but perhaps the last words should come from his long time secretary Joanne Newfield:

“A lot of people seem to forget and they say ‘oh he didn’t do that much’, but if you look at the record since his death it makes you wonder. A lot of people say that the Beatles made Brian Epstein; I don’t think Brian Epstein made the Beatles, but I think he did a great deal more than he is given credit for. A lot of managers could have found a group like them and completely messed them up. It wasn’t just their talent alone, it was their talent plus a very creative person behind them. Maybe business-wise he wasn’t the greatest, but creatively he was a genius.”

1K notes

·

View notes