#arthur pothier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Plaque en hommage à : Morts de la Seconde Guerre mondiale

Type : Commémoration

Adresse : Préfecture de Police de Paris, 66 boulevard de l'Hôpital, 75013 Paris, France

Date de pose : Inconnue

Texte : A nos camarades des Services techniques de la Préfecture de Police, morts pour la France, 1939-1944. DUBENT Edmond, Cre. de Police, BILLET Pierre, DUGARREAU Jean, DUPONT Henri, HUET Louis, HUTIN Marcel, MOULIN Louis, PONSART Jean, POTHIER Arthur, RODON Raymond, TORRESI Barthélémy, MONNIER André

Quelques précisions : Considérée comme le conflit le plus meurtrier de l'histoire notamment en raison du fait qu'elle a fait des victimes dans l'ensemble des catégories de la population, la Seconde Guerre mondiale a prélevé un lourd tribut aux forces de police françaises qui se sont opposées à l'invasion allemande, en particulier lors des combats pour la Libération en 1944. Les noms mentionnés sur cette plaque commémorative ne représentent qu'une fraction des nombreux gardiens de la paix tombés lors du conflit. Edmond Dubent (1ère photo), membre de la Résistance, fondateur du groupe résistant L'Honneur de la Police et décédé en 1943, est également honoré par une autre plaque commémorative située sur la place du Châtelet à Paris. Pierre Billet et Henri Dupont moururent en déportation après avoir ét�� arrêtés en 1943, tout comme Barthélémy Torresi, interpellé l'année suivante. Jean Dugarreau (2ème photo), Louis Huet (3ème photo), Marcel Hutin, Louis Moulin, Arthur Pothier (4ème photo), Raymond Rodon (5ème photo) et André Monnier (6ème photo) font partie des nombreux policiers morts lors de la libération de Paris. C'est également le cas de Jean Ponsart, qui est honoré par une autre plaque commémorative située sur la place de la République.

#collectif#commemoration#policiers#seconde guerre mondiale#resistance#france#ile de france#paris#non datee#edmond dubent#pierre billet#henri dupont#barthelemy torresi#jean dugarreau#louis huet#marcel hutin#louis moulin#arthur pothier#raymond rodon#andre monnier#jean ponsart

0 notes

Text

Montreal's vanished landscapes are at the heart of two new books | Montreal Gazette

Curving thoroughfares like Côte-des-Neiges Rd. trace the contours of former rivers. Orphaned row houses, peeking out between towering high rises, bear witness to the proud greystone terraces that once covered downtown. Even though streetcars disappeared from Montreal in 1959, the neighbourhoods to which they gave birth, like Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, Snowdon, Villeray and Park Extension, attest to their role in developing the city.

Vanished landscapes figure prominently in two new books on Montreal — one on a major archaeological site preserving the vestiges of the former Parliament of Canada and the other on the role of photography in the fight to save heritage.

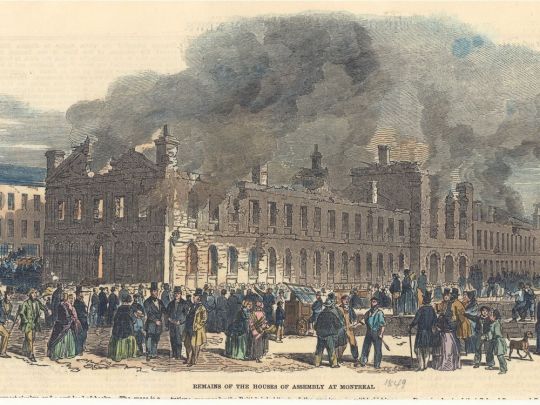

Montréal Capitale , produced by the Pointe-à-Callière archaeology and history museum, vividly re-creates Montreal’s brief reign as the capital of Canada from 1844 to 1849. That status went up in flames when an English-speaking mob, urged on by the Montreal Gazette, torched the Parliament building to protest against a bill reimbursing Quebecers for damages incurred during the 1837-38 Rebellions.

Concluding that ethnic tensions in Montreal were too volatile for it to remain the capital, the government moved out and spent several years alternating between Quebec City and Toronto. Unable to reach a consensus on a permanent capital, Canadian leaders petitioned Queen Victoria, who chose Ottawa on New Year’s Eve, 1857. It became the seat of government in 1866, a year before Confederation.

Article content

Montreal’s brief chapter as capital has been all but forgotten, said Louise Pothier, Pointe-à-Callière’s curator and chief archaeologist and editorial director of the book.

“Historians and archaeologists have almost bypassed an essential episode in the country’s history,” she said.

Yet it was a pivotal moment, marking the attainment of responsible government — in which the executive is responsible to an elected assembly — and of French as an official language of the legislature, along with English, Pothier noted. It also spurred the development of Montreal, inspiring grandiose plans to beautify the urban environment.

Built in 1833-34 as St. Ann’s Market, the more than 100-metre-long stone Parliament building collapsed in on itself during the fire, preserving fragments of hundreds of thousands of artifacts.

From 2010 to 2017, a series of archaeological digs turned up the incredibly well-preserved vestiges beneath Place d’Youville, where the museum hopes to erect a new $120-million wing in the years to come.

Article content

Citizens trying to save the Victorian neighbourhood east of McGill lost the first round in 1972, when developer Concordia Estates razed hundreds of homes to build the La Cité complex at Parc Ave. and Prince-Arthur St.

But they went on to score a significant victory when Phase 2 of the project was cancelled and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp acquired the surviving buildings to convert them into co-operative housing. In 1983, the Milton Park Community was inaugurated. Covering six city blocks, it now houses more than 1,000 residents in 16 co-ops and six non-profit associations.

While the buildings destroyed for Phase 1 are long gone, the black-and-white photographs taken in the heat of the action by Gutsche and her partner, David Miller, live on in museums and archives. “If such a choice were possible, we would have kept the buildings, and not the images of what was gone,” she laments.

In another chapter, Louis Martin, a professor of architectural history at UQÀM, explores the work of artist, architect and university professor Melvin Charney, who died in 2012.

In the 1970s, as protests mounted, Charney became increasingly radicalized. In 1972, he curated a collective exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts titled “Montréal: plus ou moins? Montréal: plus or minus?” Among the works was a photomontage he created of St-Laurent Blvd. between René-Lévesque Blvd. and Ste-Catherine St., a streetscape now mostly demolished.

Charney is probably best remembered for organizing Corridart, an outdoor art exhibition commissioned by the Quebec government for the 1976 Summer Olympics. Four days before the Games opened, then-mayor Jean Drapeau infamously had it torn down overnight.

Article content

It included a series of installations on Sherbrooke St. by architects Jean-Claude Marsan, Lucie Ruelland and Pierre Richard. Directly across the street from the former site of the Van Horne mansion, they erected an enlarged version of Abbott’s photograph of the mansion being demolished, with an orange finger pointing at the nondescript high rise that had replaced it.

“We regret the finger pointing at our building, which many of our tenants and prospective customers take as offensive,” Azrieli complained in a letter to Drapeau.

Other topics include city of Montreal photographer Jean-Paul Gill’s images of the former Red Light District, demolished in the late 1950s; photography in the former crime tabloid Allô Police; the 1968 Sir George Williams computer centre occupation; urban exploration (urbex) photography; and the archives of Ramsey Traquair, director of McGill University’s School of Architecture from 1913 to 1939.

This content was originally published here.

0 notes