#anyways and so it goes voted sound of the summer fifteen million years in a row and counting

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

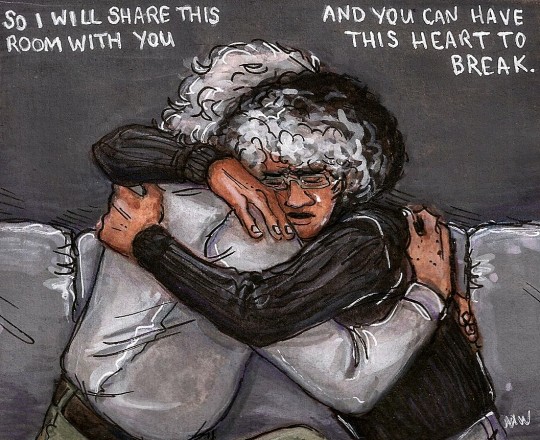

and so it goes, and so it goes and so will you, soon, I suppose

#i haven't posted overt ''ship art'' since may 2022.... goddamn. the power of these video games.#anyways and so it goes voted sound of the summer fifteen million years in a row and counting#metal gear solid#metal gear solid 4#guns of the patriots#mgs#mgs4#solid snake#otacon#hal emmerich#otasune#matt draws

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Children Stand

The hype was real. His father had agreed to letting him go on the college tour with the other seniors. Hamza smiled and stretched his arms out wide. His phone buzzed, Asr, it notified. There’s enough time, Hamza thought to himself.

Musa and Ubaid were betting on who could slide down the banisters with the most flair, while the rest of the tour group was listening to the guide’s speech about the founder of the school. Hamza was only partially listening.

“And this is Westhaven Building, also known as The Haven. It is a common area for all students who are looking for a quiet place to study for a test. It was donated to the school by Samuel Westhaven…” the sophomore explained as Hamza sent a snapchat of the old time, gothic building. It was an ominous castle, even sporting a few gargoyles, and looked anything but like a Haven.

The students looked around, like excitable puppies, the song from Aladdin playing in their hearts. A whole new world, indeed.

“Hamza,” Musa yelled from the steps, stretching out the ending. “They’re going to leave you,” he wailed, ghostlike.

The boy in question tore his eyes from his phone, which flashed a low battery message, to see the tour group disappearing around the corner.

“I promised your mom I’d make sure you go back safe,” Musa continued yelling.

“I’m here, stop being an idiot,” Hamza jogged over.

Musa was not quite done being an idiot. He cupped his hands, even though Hamza was now two feet away and bellowed, “My boy!” He was wheezing like an old man.

“Do you need a change of the nappies?” Musa finished the part, coughing asthmatically.

Hamza smacked him behind his head, “No, but if we’re changing things—your face should be pretty up there on the list,” he grinned, all teeth.

They continued throwing jabs at each other until they caught up with their group. Hamza joked with a few people, talked with others, and was overall feeling very at home, away from home. He had known these people for the past four years, either through school or Facebook. There were also a few lingering parents, who were raptly paying attention to the guide’s every word, some were even taking notes.

While Musa and Hamza exchanged insolent comments regarding their respective dignities, Ubaid was being a bit cleverer. Ubaid’s specialty was knowing how to make people talk, in the gentlest meaning of that phrase. He didn’t even need the bat or cement shoes.

Frivolities aside, Ubaid had learned quite a bit about the school, which he had taken a shine to. He bragged about his immense wealth of knowledge to his friends.

“Just tell us already,” Musa swatted away Ubaid’s guessing game.

“Fine. Okay, so Steven told me that his sister goes to this school and she knows where to get the answer keys to all the tests.”

There was a pause. Hamza gave Ubaid a blank stare. Musa began snickering.

“What?” Ubaid asked, following a tennis match between Musa and Hamza’s face.

Hamza sighed dramatically, and just covered his face with his palm. Musa decided to educate their unworldly friend.

“We thought you had some good stuff, the way you were banging on about it. Like, I know something you don’t know,” Musa explained, pretending to wipe away a tear.

“What, and having answer keys isn’t good stuff?” Ubaid frowned, affronted by their dullness.

The three began a heated debate on what qualified as ‘good stuff’, which ended in a miffed Ubaid, who muttered, “When you morons need help with your finals, don’t come crying to me.”

The sun was shining, the foreign birds sang beautifully and the youth were carefree. School was out, this was their final summer as kids and they all wondered about the nearing initiation to adulthood. But not for too long, because updating social media was a consuming task.

The university offered a complementary lunch, and who was Hamza to refuse? They all ate sandwiches on the grassy field, under umbrella tents.

While the sun’s fierce glare was shaded, the warm nostalgia slunk beneath the umbrellas. The youth seemed to know that this was the start. This is where their bonds frayed, and ran into millions of smaller threads that connected, separated and reconnected. Infinite opportunities, riding on the wings of their individual choices.

After refueling, they began the final leg of the trek around campus, which was to end in front of the dorms. They would spend some time there, before the bus came and picked them up in the late evening.

But burdened with food, laziness swept over the youth, like fairy dust in a Shakespearean play, and there was a group vote to just spend the rest of the time on the grassy lawn. The majority voted to just chill, and so summer time lethargy ensued.

Hamza, Musa and Ubaid were sitting under the shade of a tree, each with their back to one side of the trunk, when they heard the news. Rather, they heard their phones ding and they were fed information straight from the magical highways of the internet.

“Crap, my phone died. Where did they say it was going to be?” Hamza asked, pushing up into a sitting position.

“Uh, let me check with Sarah,” Ubaid typed a question, and sent his thoughts travelling to Sarah.

A second later, they heard an urgent ding, and Musa read over Ubaid’s shoulder. Hamza already knew they were going; he didn’t hesitate.

“She says she heard it’s gonna be in front of the mall we passed by.” Hamza remembered the squat complex and did a mental calculation. It shouldn’t take them more than twenty minutes to get across campus then to the mall. Fifteen, if they ran.

“Avengers Assemble?” Musa asked, reading Hamza’s thoughts.

“Avengers Assemble,” Hamza confirmed.

“Are you guys sure? My mom always warns me about this stuff. You never know what might happen. Once—”

“Avengers,” Hamza said through gritted teeth, and Musa finished for him, “Assemble.”

Ubaid knew a lost battle when he saw one, and reluctantly stood up to join his friends. The three of them went over to discuss with their larger group of classmates. They were young, they were fearless and they knew they could change the world.

Given that Hamza’s generation was known for eating tide pods, the youth were often side eyed by their elders. So, it was an unspoken agreement to leave the adults out of their decision to counterprotest the alt-right protest.

No need to have adults protesting their need to counterprotest a protest.

Anyways, this generation was also known for the March of their Lives and so they gathered their belongings and walked off campus.

Right, they were young. Right, they sometimes made dumb choices. Right, they had a particular aversion to rules. But there was no moral quandary here. They knew racism, sexism and blind hatred were wrong. They were emerging from their techy cocoons, spreading their wings and opening their eyes on a divided world. It was as though the hateful whispers, once entangled in between the lines of society, were suddenly shouting, an orange-hued trumpet amplifying their voices in exchange for power.

If they listened to those elders who would have them quiet, then the shouting would eventually turn to a deafening silence of a society combusting, crushing the hope of a future.

The word on the vine was the alt-righters were annoyed about a recent local election; a Muslim was elected. And she had the nerve to be a Somali immigrant. And now she was trying to run Springfield? According to the alt-righters, she was bringing sharia not only to Springfield but all of America. There was talk of confederate flags and swastikas. Basically, the tiki torches were still burning.

Hamza was not having it.

It was pretty easy to find the protesters. They heard the shouting from a few streets away. Then they saw the cops, in riot gear, standing in wait for some danger.

The alt-right group was ponied up in all sorts of hate symbols. They had swastikas on their clothing and posters. The confederate flag was flapping in the wind, held aloft by several members. They shouted, roared and chanted. Hamza could hear some of them just barking, “Hu hu hu,” a sickening background music that thudded in his ears. More than a few had drinks with them.

The counterprotesters were handing out signs, posters and other symbols. Hamza and his friends grabbed some and went to stand alongside the silent group. He noticed the louder the protesters became, the quieter the activists were. The latter refused to engage in the decisive commentary, and Hamza watched in silent awe. His own face sported a tight frown, waiting for a hairpin trigger. The protesters were shouting incendiary comments and making rude animal noises at him; he stood in the front lines.

“White lives matter!” They punctuated that slogan with “You will not replace us! Terrorists and rapists should die!” And of course, the ever present, ever confounding “Lock her up!” All of their colorful slogans were accompanied by that mad-dog guttural sound.

Springfield was not a large city, and the closeness of the protests made the adrenaline flow. The students around him had faces to match his own and as the protesters began to march down toward Town Hall, the activists began to move. They barred the pathway, creating a human wall, stood, without a word, and stared down the alt-righters.

The protesters were infuriated, and began mocking the individual activists; Hamza, standing front and center, was a good target.

The cops in riot gear began to look jumpy. They saw the alt-righters begin to approach the activists, and Hamza could see a fear in their eyes. They got on the loudspeakers.

“Please clear a path. Stand away from each other,” an authoritative man said clearly.

The alt-righters looked like rottweilers being held on an invisible leash; they were dragging at it. The cops were trying to regain control of the situation, but the activists’ silence was thunderous against the petty anger of the protesters.

Hamza felt the electricity in the crowd; he knew something was about to happen. The cops must have felt the same pulse because they got back on the speakers.

“Those who are not with the Conservative Springfielders, clear the square. Leave the streets. Exit toward the south side,” came the official voice. Hamza felt his face grimace. As if.

The way he saw it, the alt-righters were the ones pushing forward. The activists didn’t make a move; the protesters looked expectantly at the cops.

Then it happened, the trigger. The man right in front of Hamza spat on him, and turned his flag, and pushed it against Hamza and the activists. There was a thrilled roar from their radius of space.

Hamza was caught by surprise, and he felt his blood boil at the oceans of blind hate in the glob of spit. He opened his mouth and almost lifted his fist.

Then, there was an acrid crack, as though the world’s ears were popping. And the smoke began to rise from the midst of their crowd. The activists scrambled as their throats began to fill with the tearing gas. Hamza cursed, coughing and blinking away tears. Being in the wave of human bodies, all struggling in different directions away from the epicenter of the attack was entirely consuming. Hamza went on autopilot as humans diffused like droplets of water on oil.

He just ran. There were no protesters, no activists. Only the struggle for preservation. It seemed as though death was imminent.

More cracks emanated from behind Hamza, but he didn’t turn to look back. How he managed to disentangle himself from the writing mass was inexplicable, especially by him. In any case, not focusing on specifics, he ran. Head down, sweat plastering his back to his shirt, he ran.

At some point, it became clear to him that the rioting noises had become a victim of distance, and only a faint whisper of it remained. And even that may have been his imagination. More so than anything else, Hamza heard his pounding feet and his trembling heart. Nervousness, mixed with being thoroughly winded, made Hamza’s head feel like smoke, spiraling towards the sun.

When he slowed down, one thing soon became extremely apparent. He was lost.

“Low key, but crap,” he came to a stop in front of a restaurant and pretended to observe one of their sample menus. Though he was bereft of energy, he was thankful the run hadn’t stolen his wits.

Unfamiliar town, a large population of racists on the loose, and a lost dark-skinned boy. The math was clear enough.

Not reading over the menu, he scanned the streets and tried to remember which direction he came from. He thought he was doing a pretty bang up job of not looking lost, when a waiter from the restaurant walked out and asked him, “Are you lost?”

He was a few years older than Hamza and startled the latter out of his covert operation.

Hamza being as quick witted as a dancer on tip toes responded, “Nope, just checking something for my mom, thanks.”

Maybe his self-observation was a bit out of focus because the waiter eyed him oddly. Nevertheless, he nodded and walked back inside. A civil war erupted within Hamza.

He felt stupid for not asking directions, but then countered by saying, well that’s exactly how people get kidnapped in the movies.

And at the same time, he knew if he couldn’t find his way back in time, he’d be stuck in this strange city; the bus would leave without him.

To which he responded, How hard can it be? I can figure this out—cities are pretty standard.

Hamza put the menu back and took a few steps. His legs were straws, barely able to support his weight, and his palms were clammy. The sun beat down on the entire world.

Hamza realized something: his youthful bluster was largely maintained by the support of his friends. Now that he was alone, he was second guessing everything. It was a stark contrast to his self image, as the underdog, stiff upper lipped, with his first to the world’s audacities.

The thought struck him like a veil being pulled from his eyes: did his friends make it out? Guilt took him. He was the one friend who, if he didn’t get a response back, he assumed tragedy. It seemed to him, in the vast matrix of possibilities, the probability of death was alarmingly high. He hoped they hadn’t gotten caught up in the mess. He hoped they were okay. He pulled out his phone, reflexively wanting to text Musa and Ubaid. Then he closed his eyes and mouthed a word. He had drained the last bits sending a snap to Aisha.

A gut sickening feeling seeped into him as he watched his wrongdoings become manifest against him. Without realizing it, he made istighfar.

“Okay, just get back and it’ll all be okay,” he whispered reassuringly.

He remembered something. During his Usain Bolt impression, he remembered cursing at a hill. During the upward climb, he was panting and mentally destroying every bit of earth under his feet.

If he could find the hill, then he would have a good vantage point of Springfield. Then all he had to do was find the castle walls of Westhaven and he would be back in time to not face the wrath of his family.

While he did his best to sort out his footsteps, Hamza realized that he would have done it again. He would still have gone to the protest and stood against those who tried to condemn the voices of minorities. Even with only a few suns beneath his belt, he had grasped a universal truth—if the weak allow their voices to be muted, then deafness becomes a justified pride.

Unfortunately for Hamza, the small city was full of buildings and offices that looked exactly the same. He passed by the same office three times, before realizing he was walking in a circle. When the waiter saw him again, Hamza had to pretend he dropped something. Quick witted indeed bro, he thought to himself. After, he avoided that street entirely.

A few attempts and several suspicious Springfielders later, Hamza was at the foot of the hill. Matchbox houses surround him, sprinkled in between the trees, each standing superior to its predecessor. He breathed a breath of thanks and began the climb. This time around, he took a break every so often. Hamza checked his phone several times, and the dead battery forced him to berate himself about his loose snapchat morals.

Finally, he was at the top and before gazing on the city, he said the basmalah. And when he turned his eyes on the city, the first thing they fell on was the angst filled establishment. Westhaven Building. He whooped, joy-rushed at finally succeeding. He breathed another thanks and made a mental map of how to get back.

Then he ran down the hill, hands flailing in the air, leaving behind a stream of laughter. The fifteen-minute trek up the hill was cancelled out by a minute of wind in his hair and wings on his back.

He danced to a stop, still chortling and looked around. He knew he had to make a right at the end of the street and saw that it was the only way he could go. The street was lined with tall, ominous trees and he heard a raven’s caw in the distance. Hamza could have sworn he felt a cold chill.

He took a breath and calmed himself. He wasn’t three years old, and he could make it across without his parents’ help. The sun was preparing to set, and rain clouds filtered the orangey glow into an eerie cast on Hamza’s face.

He began walking and told himself to stop imagining things. He was glad Musa and Ubaid were not here to watch him make a fool of himself. Sweating over the sunset. He shook his head at his childishness.

But there it was again, that noise. He hoped it was just his brain playing tricks on him, but it was getting louder. He looked around for the source but his ears failed him.

“What is that?” He asked himself, already knowing the answer. Then he shook his head. “No. No, hopefully not. Maybe it’s a –” his brain took an impromptu vacation.

He could no longer deny the doppler effect; in the narrow street, lined with dark trees, the source of the noise was beelining towards him.

He glanced down at his hands, covered in liberal wrist bands. And his shirt, dotted with pinback buttons. Not to mention his kufi, which he had decided to wear that day. And aside from all the counterprotest paraphernalia, the worse case against him was his dark skin. There was no denying what Hamza stood for. He wiped his sweaty palms on his jeans.

The large crowd was doing their rumbling chant, interjecting it with the occasional bark. “You will not replace us,” he heard their chant. “Hu hu hu,” was the replying chorus.

The group was at the end of the street, having just turned the corner and began to slither towards him—a depraved snake made of posters, swastikas and confederate flags.

Hamza looked around and saw his one man against their hundred. They blocked out everything else like a wave of hatred over his world. Hamza felt a calm wash over him.

He coolly estimated his options. He could outrun them; there was a direct correlation between their racism and their obesity. But something in his chest stopped him from running back up that hill. Firstly, he was sure they had seen him—he had been walking toward them. And more powerfully, he refused to be a coward.

A thought occurred to him: if this was his day to die, then there was no two ways about it. If God was going to take his soul today, then Hamza was going out standing up for what was right. The cold directness of his decision shook a more emotional part of his heart, but it was drowned out by the chanting. Hamza began walking towards them, not making a sound. He was fully prepared to meet, in the best case, hospitalization. He said the name of God and stepped.

Their footsteps ate away at the distance and before he knew it, Hamza was inches away from the man who had spit in his face. He smelled like alcohol. Their deep warbling was deafening in his ears, pounding at him in waves. Hamza stared forward, not meeting any eyes, and still stepped.

And the crowd parted. Not one at a time, but simultaneously as though the whole thing was rehearsed. Or as though they were being forced to walk around him. They created this narrow path for him, a stone making its merry way along a river.

Hamza hid the astonishment that melted into paranoia. They’re going to close in around me, and swarm, he thought. He formulated the ways they would attack him. With their beer bottles, he supposed. Maybe a hate flag to the head? Hamza’s heart was the eye of the storm, as he stepped through tearing ignorance. He heard their rude comments and their curses, but not once did they acknowledge him.

He felt the impulsive nature of youthhood to grab one of them and ask, “Can you see me?” Biting his tongue, he kept walking, invisible.

The entire lot of them walked around him, regrouping once they had passed him. When Hamza made it out on the other side, he inspected his body looking for the wounds. Nothing. He stopped walking and turned back toward the still chanting crowd.

Not one turned to look back at him. Hamza’s face broke into a stupid grin as he turned the corner, looked up at the sky, and felt a newness in his chest. He ran the rest of the way back to Musa and Ubaid.

#hamza#youth#islam#protest#activism#story time#creatve writing#stand up for what's right#writers#humans against hate#stand up#muslim writer#muslim#fiction#youth in america#america#stories

2 notes

·

View notes