#antinoopolis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

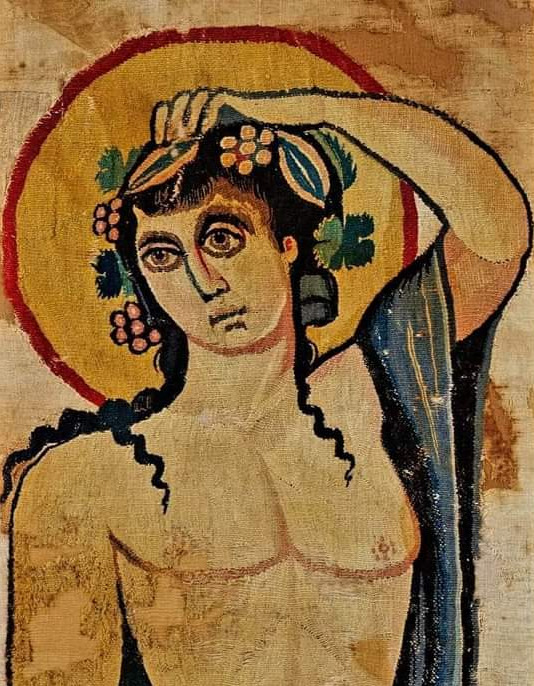

🪷 This linen-backed wool woven Dionysus tapestry from the heyday of Antinoopolis Egypt (known for fabulous fabric art) is extraordinary for its huge size: 210 cm x 700 cm (7 feet x 23 feet). The German language text says it adorned a Roman villa or temple.

Full text: https://abegg-stiftung.ch/collection/der-spaetantike-mittelmeerraum/ 🪷

367 notes

·

View notes

Text

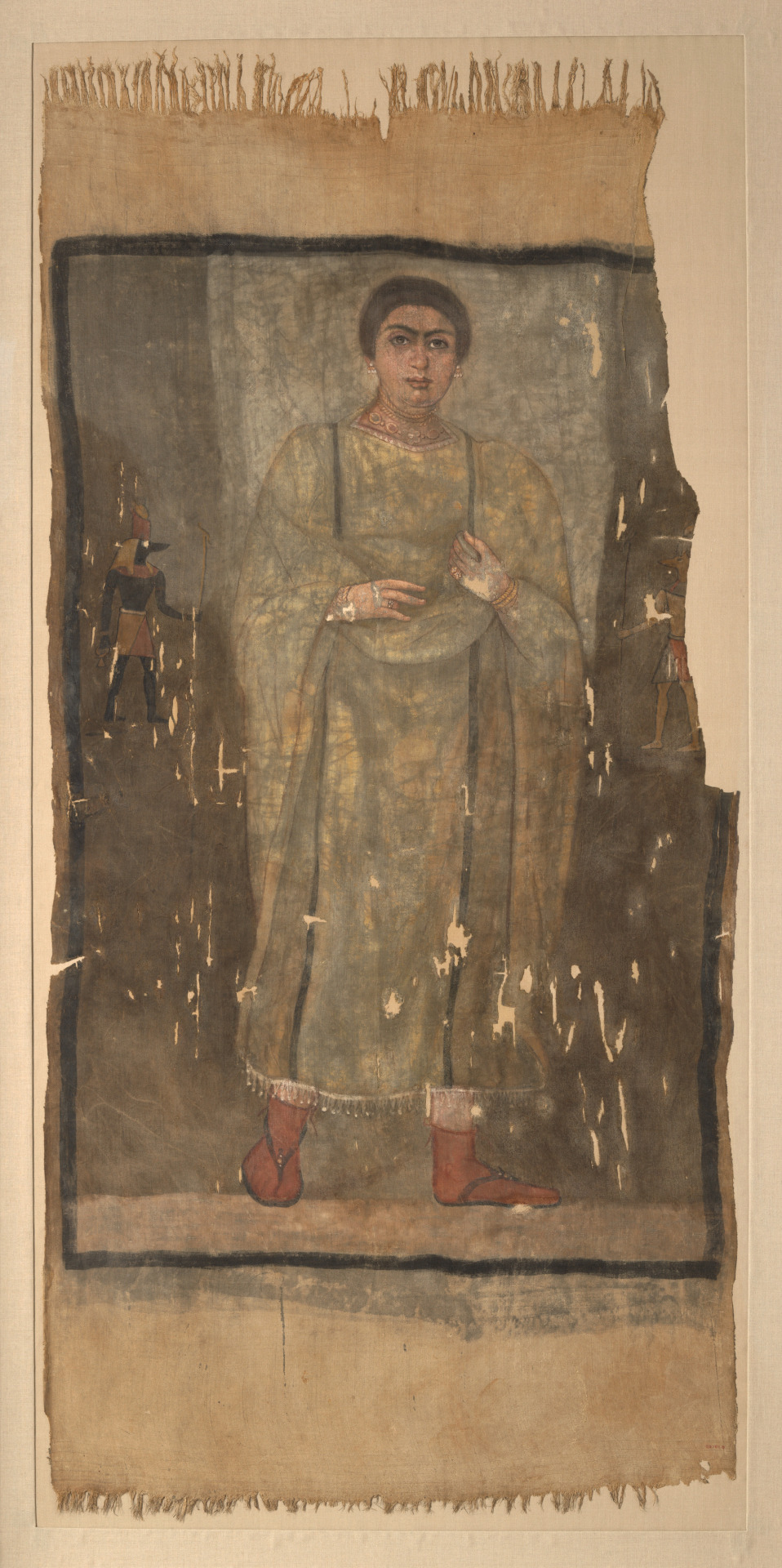

Shroud of a Woman Wearing a Fringed Tunic - Met Museum Collection

Inventory Number: 09.181.8 Roman Period, A.D. 170–200 Location Information: From Egypt; Possibly from Middle Egypt, Sheikh Abada (Antinoopolis); Said to be from Fayum

Description:

This round-faced woman wears a fine tunic with narrow clavi (stripes); a mantle is draped over her arms. The construction of her garments is not easy to understand. The very deep folds below her right arm could be part of the mantle or might constitute tunic sleeves, while a tight sleeve visible around her left wrist could belong to the tunic or an undertunic. The fine fringe around the bottom could also be part of the tunic or of the undergarment whose upper border, decorated with purple triangles, is visible at the neckline.

The woman wears a great deal of jewelry; earrings, three necklaces, six twisted gold bracelets, and three rings can be seen. On her feet are red socks and black sandals. She is flanked on either side by Egyptian deities and seems to step forward from a light gray rectangle. This form could be interpreted as a doorway, a late reminiscence of the so-called False Doors of pharaonic Egypt, elaborate niches through which the dead were believed to communicate with the living.

#Shroud of a Woman Wearing a Fringed Tunic#middle egypt#sheikh abada#antinoopolis#fayum#upper egypt#met museum#09.181.8#roman#womens clothing#RPWC#linens#RPlinens

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the birthday of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, born on 24 January in 76CE. His statue is pictured here (left) beside a statue of his lover, Antinous.

In 130CE, Antinous drowned in the Nile. In his grief, Hadrian named a flower and a star after Antinous, founded the city of Antinoopolis, and made Antinous into a god. So many statues of Antinous were made that he became one of the most commonly depicted people in the Graeco-Roman world.

Check out our podcast to learn more about Hadrian and Antinous

#hadrian#antinous#antinoos#queer history#roman history#queer rome#lbgt#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbt history#queer#roman empire

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

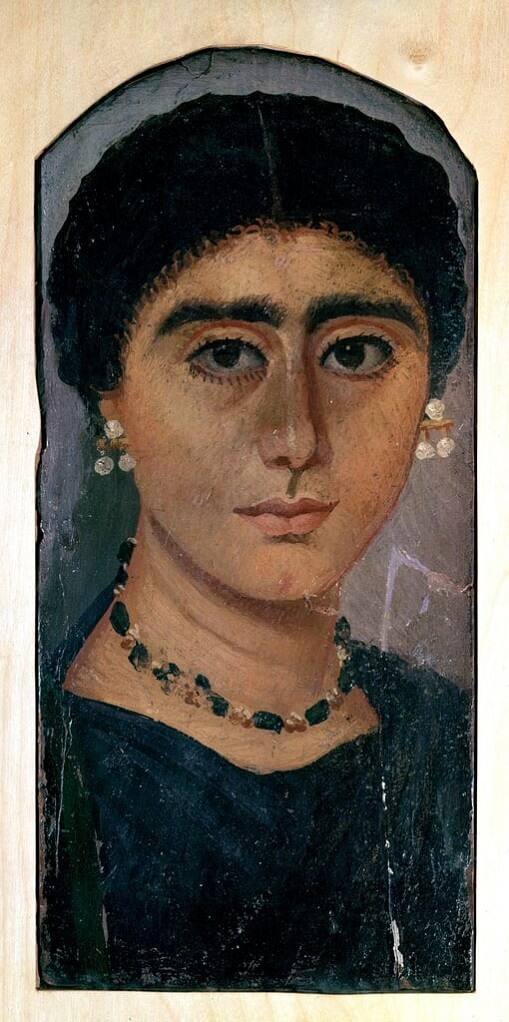

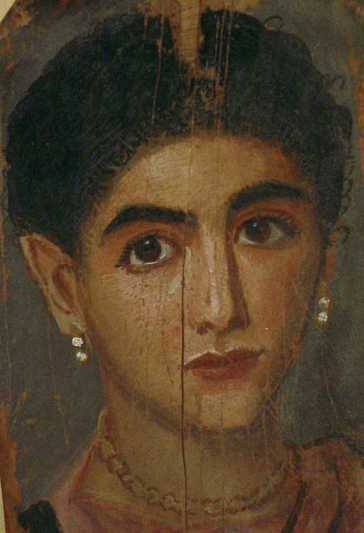

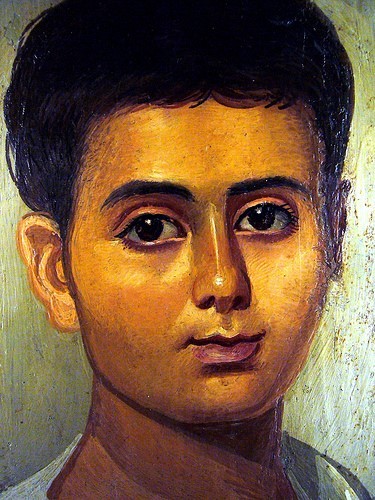

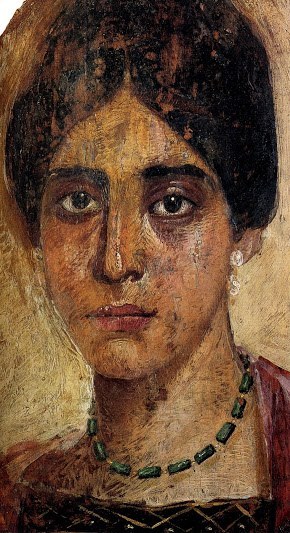

Mummy portrait of a woman, known as "L'Européenne"

* Antinoopolis

* 120-130 CE

* Louvre

More info

Attribution:

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

#Roman Egypt#mummy portrait#2nd century CE#Roman women#ancient#jewelry#art#roman#hairstyle#clothig#eye#portrait#Louvre#Carole Raddato#following Hadrian

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

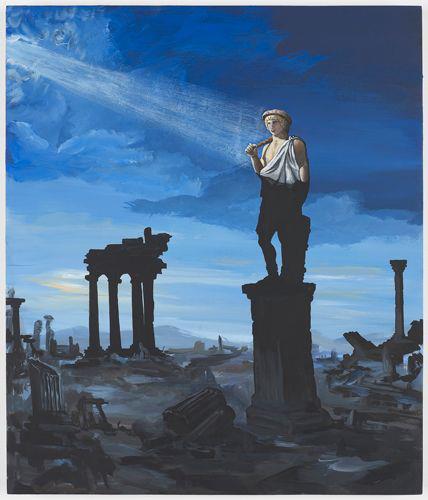

Kings and Their Lovers

Male Kings and Their Homoromantic or Erotic Relationships from Antiquity to Modern Times History offers numerous examples of male rulers who had homoromantic or erotic relationships with other men. These connections were often complex and influenced by cultural, societal, and personal factors. Here are some remarkable examples:

Antiquity

Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) The Macedonian king and famous conqueror had a particularly close relationship with Hephaestion, his childhood friend and confidant. Plutarch described Hephaestion as "Alexander's lover." After Hephaestion's death, Alexander was inconsolable and ordered a nationwide mourning. The Persian eunuch Bagoas is also mentioned in ancient sources as Alexander's lover.

Emperor Hadrian (76–138 AD) The Roman emperor is known for his passionate relationship with the young Greek Antinous. When Antinous drowned in the Nile, Hadrian was devastated. He had his lover deified, founded the city of Antinoopolis, and erected statues of Antinous throughout the empire. These actions testify to Hadrian's deep affection and grief.

Middle Ages

Richard the Lionheart (1157–1199) Richard I of England had a close relationship with Philip II of France. Contemporary chroniclers described how the two kings "ate from the same table and drank from the same cup every night" and "slept in the same bed." Although the exact nature of their relationship remains disputed, such reports suggest a very intimate connection.

Edward II of England (1284–1327) Edward II had an intense relationship with Piers Gaveston, which chroniclers of the time described as excessively intimate. Later, he developed a similarly close relationship with Hugh Despenser the Younger. These connections led to political tensions and ultimately contributed to Edward's deposition.

Modern Times

James I of England (1566–1625) James, also known as James VI of Scotland, had several close relationships with men. Particularly notable was his connection with George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham. In letters, James called Villiers "my sweet child and wife" and "my dear Venus boy." This correspondence indicates a passionate and intimate relationship.

Louis XIV of France (1638–1715) Although the Sun King is primarily known for his female mistresses, there are indications of intimate relationships with men. The Duke of Saint-Simon reported in his memoirs of several homosexual affairs at court, including one between Louis and his brother Philippe, Duke of Orléans.

Frederick the Great of Prussia (1712–1786) Frederick had close relationships with several men, particularly Hans Hermann von Katte in his youth. Although Frederick married, the marriage remained childless and distant. Instead, he surrounded himself with a circle of close male friends and confidants.

Ludwig II of Bavaria (1845–1886) Known as the "Fairy Tale King," Ludwig II had close and presumably romantic relationships with several men. Particularly well-known are his connections to Richard Hornig, his stable master, and Paul von Thurn und Taxis. Ludwig's homosexuality was an open secret during his lifetime and contributed to the accusations that led to his dethronement.

Modern Era

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (1868–1918) Although later married, the last Russian Tsar had a close relationship as a young man with his cousin, Prince Nicholas of Greece. In letters, he described their "special friendship" and the "wonderful nights" they spent together.

These examples show that same-sex relationships among rulers were not uncommon. The nature and perception of such connections varied greatly depending on the cultural and historical context. While some relationships were lived relatively openly, others remained hidden due to societal norms and political implications or were only hinted at in documentation.

It is important to note that modern concepts of sexual orientation and identity cannot be directly applied to historical figures. Many of these rulers would not have identified themselves as homosexual or bisexual, as these terms did not exist in their time. Their relationships must be understood in the context of their respective culture and time.

Nevertheless, these historical examples offer important insights into the diversity of human relationships and show that same-sex love and affection existed even at the highest levels of power.

Text supported by GPT-4o, Claude AI

Image generated with SD1.5. Overworked with inpainting (SD1.5/SDXL) and composing.

#History#LGBTQHistory#AlexanderTheGreat#Hephaestion#Hadrian#Antinous#RichardTheLionheart#EdwardII#JamesI#LouisXIV#FrederickTheGreat#LudwigII#NicholasII#QueerHistory#SameSexRelationships#Monarchs#RoyalLovers#HistoricalFigures#HumanRelationships

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

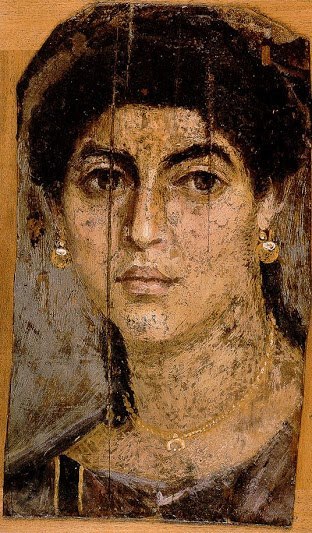

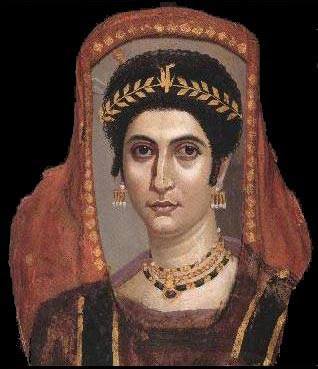

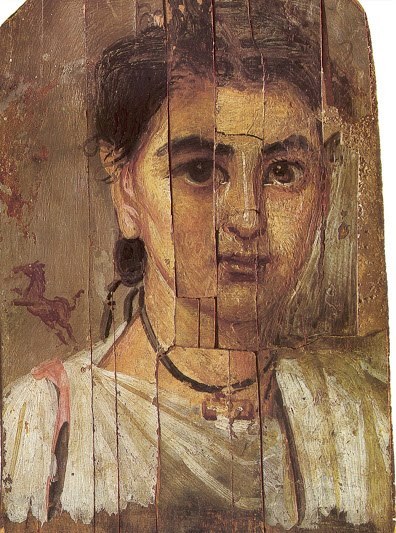

Portrait of a woman, from Faiyum

Roman Period, 2nd century. Sycamore fig wood.

From Antinoopolis, Middle Egypt.

Now in the Louvre. E 12569

The portrait was found by the archaeologist Albert Gayet during the excavation campaign of 1904 or 1905 at the necropolis of Antinoopolis in Middle Egypt. It entered the Louvre's collections in 1905.

A fragment of the right side of the board has been reglued. The paint has worn away on the nose, leaving a dark mark where the brown undercoat shows through.

This is an almost full face portrait of a young woman turned slightly to the right, but looking directly at the viewer. Her well defined mouth is accentuated by a shadow under the lower lip; a touch of pink indicates a dimple on her chin. Her hair is parted in the middle, and arranged in parallel waves painted in thick strokes of black.

Read more

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

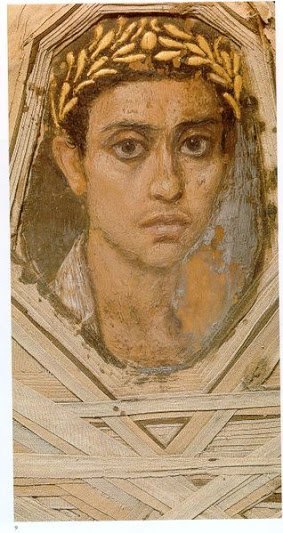

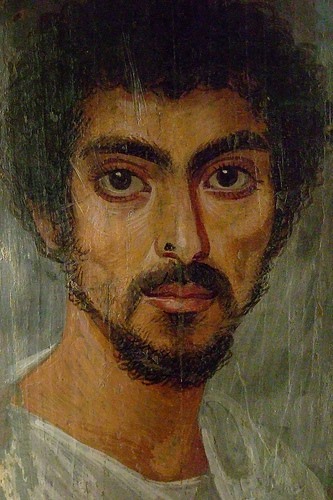

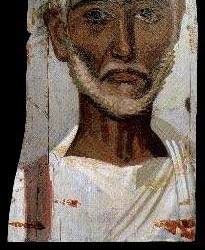

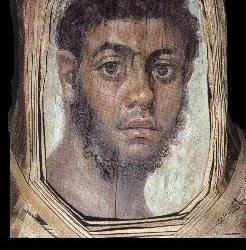

LOS RETRATOS DEL FAYUM

FAYUM MUMMY PORTRAITS

(Español / English)

Los retratos de El Fayum o retratos de momias de El Fayum (la mayoría de los retratos de esta tipología se han encontrado en esa región de Egipto) o simplemente, retratos de momias son términos modernos que se refieren a un tipo de retrato realista, pintado en tablas de madera que cubren el rostro de muchas momias de la provincia romana de Egipto. Pertenecen a la tradición de pintura en tabla, una de las formas de arte más respetadas en el mundo clásico. De hecho, los retratos de El Fayum son el único gran conjunto de arte de esa tradición que ha perdurado y que fue continuada en las tradiciones bizantina y occidental en el mundo posclásico, incluyendo la tradicional local de iconografía copta en Egipto. Los retratos de momia han sido encontrados a lo largo de todo Egipto, pero son más comunes en la región de Fayum, en particular, de Hawara a Antinoópolis, por ello el nombre; aunque, los "retratos de El Fayum" son considerados más como descripción estilística que geográfica.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FAYUM MUMMY PORTRAITS

Mummy portraits or Fayum mummy portraits (also Fayum mummy portraits) is the modern term given to a type of naturalistic painted portraits on wooden boards attached to mummies from the Coptic period. They belong to the tradition of panel painting, one of the most highly regarded forms of art in the Classical world. In fact, the Fayum portraits are the only large body of art from that tradition to have survived.

Mummy portraits have been found across Egypt, but are most common in the Faiyum Basin, particularly from Hawara and Antinoopolis, hence the common name. "Fayum Portraits" is generally thought of as a stylistic, rather than a geographic, description. While painted Cartonnage mummy cases date back to pharaonic times, the Faiyum mummy portraits were an innovation dating to the Coptic period on time of the Roman occupation of Egypt.[1]

They date to the Roman period, from the late 1st century BCE or the early 1st century CE onwards. It is not clear when their production ended, but recent research suggests the middle of the 3rd century. They are among the largest groups among the very few survivors of the highly prestigious panel painting tradition of the classical world, which was continued into Byzantine and Western traditions in the post-classical world, including the local tradition of Coptic iconography in Egypt.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hadrian and Antinous

Antinous was Emperor Hadrian's lover. Since Antinous was a slave boy, this in and of itself was not odd, and would not have been considered queer, except for the deification of Antinous by Hadrian.

Many scholars (though this is just one) believe that the two of them were not just sexually involved, but also romantically involved. This is further backed up by the knowledge that we have no evidence of Hadrian ever being attracted to women, though we do have evidence of his attraction to boys and men. There is also no evidence that Hadrian's relationship to Antinous was political in nature.

Antinous died after falling into the nile, or at least, that is the story put forth by the Historiae Augustae, or the Augustan histories. There are a number of other conspiracy theories about his death, though most of them are unlikely.

When Antinous died, Hadrian "muliebriter flevit," or wept like a woman.(Historiae Augustae) Hadrian demanded that Antinous was made into a god, and that there would be a city built on the site of his death, called Antinoopolis.

Deifying someone that was not a member of the royal family was extremely odd, and he also deified Antinous without approval of the senate. Hadrian also proclaimed that the flowers that grew by the Nile were dedicated to Antinous, inscribed his name on an obelisk, and named a star after him as well.

#queer history#queer#gay#gay history#lgbt#lgbt history#type: person#greco roman collection#Im the kind of gay person that has a picture of antinous on my wall

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

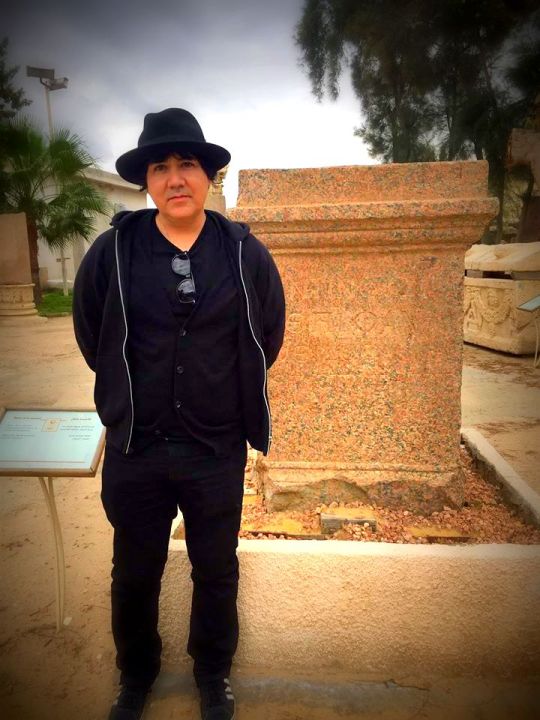

🪷 A colossal statue of Antinous stood on this plinth dedicated to Antinoos Epiphanios. Modern priest AntoniusSubia prayed before it in Alexandria Egypt. It was commissioned by Julius Fidus Aquila, first priest of Antinoo at Antinoopolis. 🪷

More images:

antinousstars.blogspot.com/2021/02/antoni…

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nell'ottobre del 130 d.C. moriva Antinoo, amante dell'imperatore Adriano, annegato nelle acque del fiume Nilo. L'imperatore era infatti in uno dei suoi tanti viaggi in giro per l'impero, proprio in Egitto, quando Antinoo morì.

«Durante una navigazione sul Nilo perse Antinoo, e lo pianse con accenti femminili. Alcuni insinuarono ciò che la bellezza del giovane e la sensualità di Adriano lasciano immaginare» (Historia augusta, Adriano, 14)

Secondo le informazioni ufficiali Antinoo annegò scivolando dal ponte della nave su cui erano in crociera lui e l'imperatore, anche se si sospetta che si possa essere trattato di un suicidio. Un oracolo aveva infatti predetto che Adriano sarebbe morto nel giro di un anno e il suo amante era convinto in questo modo di ritardare il fato degli dei. Oppure Antinoo temeva che l'imperatore non lo avrebbe più amato ora che stava diventando adulto. Tuttavia è anche possibile che sia stato eliminato perché qualcuno sospettava che l'imperatore lo nominasse suo erede.

Adriano, che sarebbe poi morto nel 138, quasi 10 anni dopo, rimase straziato dalla morte di Antinoo, fondando in Egitto una città in suo onore, Antinoopoli.

Poco si sa della vita di Antinoo prima dell’incontro con Adriano, se non che proveniva da una famiglia greca della Bitinia ed era nato probabilmente tra il 110 e il 112 d.C., nel mese di novembre. Il suo nome forse viene dal personaggio dell’Odissea Antinoo, uno dei maggiori pretendenti di Penelope e avversario di Telemaco oppure che fosse l’equivalente maschile di Antinoe figlia di Cefeo che rifondò la città di Mantinea, che aveva ottimi rapporti commerciali proprio con la Bitinia. E’ altresì probabile che non fosse uno schiavo, dato che post-mortem venne divinizzato. Probabilmente Adriano aveva incontrato il giovane per la prima volta a Claudiopoli nel 123.

0 notes

Text

Vue des ruines de la ville, prise du côté du sud-ouest — “View of the city ruins, taken from the south-west”

Antinous, a Greek boy from Bithynia, was Emperor Hadrian’s closest lover. While sailing the Nile, Antinous drowned under strange circumstances at age 18. Following his death, in a controversial move, Hadrian deified Antinous as Osiris and Dionysos. Additionally Hadrian identified the rosy lotus of the Nile as a symbol of the boy.

Antinoöpolis was founded by Hadrian not too far from where Antinous drowned, and the city became the center of worship for Antinous Osiris. Hadrian would then move to Athens, where he established an annual festival to commemorate Antinous each October: Antinoeia.

Edme-François Jomard. 1817.

7 notes

·

View notes

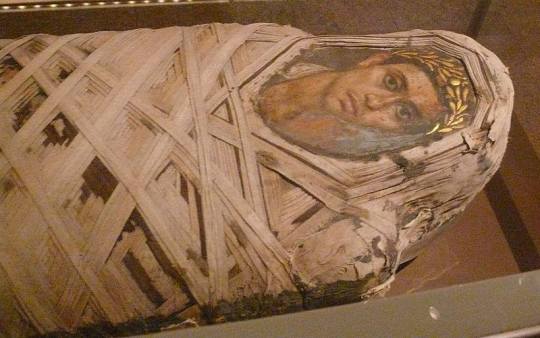

Photo

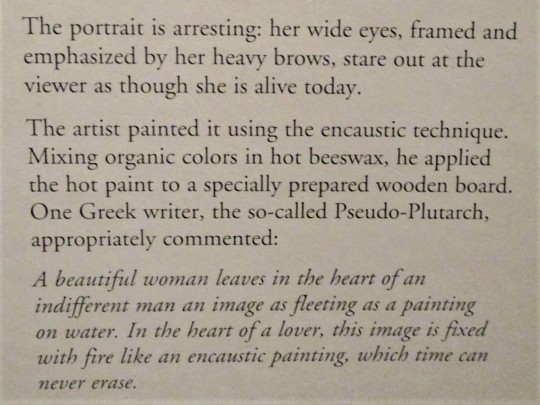

Portrait of a Woman, Encaustic on wood panel with gilt stucco, Egyptian, Roman Period, 130-161 C.E.

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

This painting was meant to be placed over the face of a mummy.

#ancient art#Egyptian art#Antinoopolis#encaustic painting#Pseudo-Plutarch#mummy#burial practices#Roman Empire

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shroud of a Woman Wearing a Fringed Tunic - Met Museum Collection

Inventory Number: 09.181.8 Roman Period, A.D. 170–200 Location Information: From Egypt; Possibly from Middle Egypt, Sheikh Abada (Antinoopolis); Said to be from Fayum

Description:

This round-faced woman wears a fine tunic with narrow clavi (stripes); a mantle is draped over her arms. The construction of her garments is not easy to understand. The very deep folds below her right arm could be part of the mantle or might constitute tunic sleeves, while a tight sleeve visible around her left wrist could belong to the tunic or an undertunic. The fine fringe around the bottom could also be part of the tunic or of the undergarment whose upper border, decorated with purple triangles, is visible at the neckline.

The woman wears a great deal of jewelry; earrings, three necklaces, six twisted gold bracelets, and three rings can be seen. On her feet are red socks and black sandals. She is flanked on either side by Egyptian deities and seems to step forward from a light gray rectangle. This form could be interpreted as a doorway, a late reminiscence of the so-called False Doors of pharaonic Egypt, elaborate niches through which the dead were believed to communicate with the living.

#Shroud of a Woman Wearing a Fringed Tunic#middle egypt#upper egypt#sheikh abada#antinoopolis#fayum#met museum#09.181.8#womens hair and wigs#roman#RPWHW

1 note

·

View note

Text

Antinous

Antinous, reputed-lover of Emperor Hadrian, is thought to have been born #onthisday in AD 111. Born in the Roman province of Bithynia, he was travelling with the imperial entourage in Egypt when he drowned tragically in the Nile in AD 130. After this death, Hadrian founded a town for him at the bend of the river where he died called Antinoopolis, or Antinous City.

With Hadrian's creation of this city and the commissioning of a number of portraits of the young man, Antinous became a god. His image spread across the empire and a cult-like following formed. The image and notoriety of Antinous reach from antiquity into the modern world.

This inscribed bust from Syria found in 1879 is the most important surviving image of Antinous, and can be seen on display in our FREE exhibition Antinous: boy made god until 24 Feb 2019.

#Ashmolean#Ashmolean Museum#Museum#Oxford#Oxford University#Antiquities#History#Roman Empire#Hadrian#Rome#Antinous#Antinoopolis#Bust#cast#Marble#Art History#Material Culture#Antiquity#Object

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shroud of a woman Roman Egypt, c. 170–200 A.D., Middle Egypt, Sheikh Abada (Antinoopolis), or possibly Faiyum Met Museum. 09.181.8

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman black leather shoe

* Made in Egypt

* 3rd or 4th century CE

* findspot: Antinoopolis, Egypt

* British Museum

London, July 2022

64 notes

·

View notes