#antidisciplinary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

literally everything goes back to me being antidisciplinary god damn it

#Theres no easter bunny theres no tooth fairy and there are no disciplinary distinctions#indexed post

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

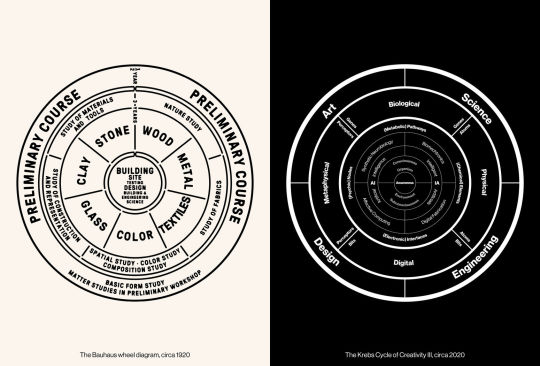

Oxman Neri, The Krebs Cycle of Creativity III in Art and Practice with Neri Oxman (seminar), MoMA, Floor 2, Creativity Lab, 2020.

Art and Practice is a series of seminars and workshops that bring together emerging and experienced artists. Together they explore the challenges and possibilities of sustaining a creative life.

Neri Oxman will discuss her team’s creative process and invite others to share their experiences with the tensions between modes of thinking and making in the bio-digital age. Oxman will present her Krebs Cycle of Creativity, a framework that considers the domains of art, science, engineering, and design as synergetic forms of thinking; the input from one domain becomes the output of another. Each discipline explains, predicts, utilizes, and informs the world around us, and ultimately the designs we create. Inspired by the Bauhaus curriculum diagram, created in 1922 by Walter Gropius, the Cycle embodies the holistic nature of the Bauhaus education, in which individual creators representing diverse disciplinary backgrounds came together in pursuit of a shared mission to reform art, design, and society.

#radicantattitude#design#designofchance#antidisciplinary#antifragile#poetry#tellingtheevolution#krebscycleofcreativity#diagrams#nerioxman#2020s

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

To younger generations of designers and architects, I profess that design is neither a profession nor a discipline; it is an acquired taste in synthesis. A good designer can, by virtue of design—the noun and the verb—not only solve problems but also seek them out, long before they emerge. Design, like language itself, conveys meaning through the creation of wholes that are bigger than the sum of their parts. And when a tight connection exists between method and form, technique and expression, process and product, one can enter the realm of the generative, where design transcends problem solving and becomes a system of thinking about making to attack any world problem.

Neri Oxman

0 notes

Link

Interesting essay. I’m not quite sure I follow the argument to the essay’s double conclusion 1) a celebration of antidisciplinary works with global scope AND 2) a criticism of academia for training grad students to “sharpen their critical teeth by tearing apart the very texts that led them to devote their lives to their fields. Has the time come to rethink a definition of scholarship that excludes the very texts that once mesmerized and inspired us?”

Isn’t part of the sharpening of critical teeth to be able to both appreciate the strengths and limitations of arguments?

...

Though still widely read decades after their publication, today Undead Texts usually appear on graduate syllabi only to serve as the whipping boys of advanced training, examples not only of superseded answers but also of the wrong kinds of questions to ask. At least one prominent professor of sociology who claims to have loved Goffman’s The Presentation of Self when he first read it, in college, told us that he would never assign it to graduate students. When we asked recent Ph.D.s on social media whether they had read, cited, or taught The Second Sex, they replied that they saw its key purpose as illustrating the limitations of white bourgeois feminism. Undead Texts remain crucial to the history of their fields, but their arguments and methods are no longer seen as viable.

....

Authors of Undead Texts reframe what both academics and laypeople thought they knew: about nationalism, about religion, about scientific progress, about femininity. After reading these books, readers often see the world with new eyes. This reorganization of one’s mental furniture can last a lifetime, not least because Undead authors combine scholarly erudition with the popularizer’s talent for coining (or citing) memorable phrases: Kuhn’s paradigm shift; de Beauvoir’s "One is not born, one becomes a woman"; Mary Douglas’s repurposing, in Purity and Danger, of William James’s notion of dirt as matter out of place.

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

At the Media Lab, we celebrate the “antidisciplinary” — those spaces in academia and intellectual discourse that lie between disciplines. I don’t think it’s a big leap to draw a parallel here, and say point-blank that our fellow humans don’t need to be forced into categories, either.

Joi Ito in MIT Media Lab at Medium. Responding to the conservative tyranny of the gender-typicals

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

One of my most important mantras came from a talk Joi Ito gave at the PopTech! conference. He said education has to fundamentally be antidisciplinary- a vein of thought inspired by Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s idea of the Antifragile. By antidisciplinary, Ito refers to the tearing down of academic ivory towers to inspire innovation among the brightest and the best in academia.

Donald E. Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., is the Founding Director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, a Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

This talk delivered at PopTech! 2010 is an overview of the origins, epistemology and research being pioneered by the Wyss Institute.

And right off the bat, I could notice strong ties of his vision of academic impact to ideas of Consilience and Open Collaboration. That’s why there are no laboratories at the Wyss Institute- there are Collaboratories. And that to me is brilliant! It also reminds me of the design of the Pixar Campus and Offices- what I had read about in Isaacson's book about Steve Jobs. It was designed to inspire interaction and accelerate the flow of good ideas.

And this model to me looks more and more the future of effective academia. Apprenticeships need to be revived and the old notion of a student needs to be discarded. We can only get good at what we do only if we know who we are in the massive scheme of intellectual things.

Dr. Ingber talks about a sculpture class he took as an undergraduate at Yale and how the confluence of tensegrity structures and cell cultures inspired a lifelong obsession- how inspiration comes from the most arcane of connections. Here’s a quote:

"And the reason that I'm here today (in terms of serendipity) is that I saw [tensegrity structures] for the first time when I was an undergraduate at Yale in a sculpture class that I just happened to take the same week that I learned to culture cells. And that, as they say, is the beginning of the rest of my life."

This talk reflects the scale of ambition and effectiveness of the Wyss Institute. Its inspirational and the experimenters of academic/education policymakers should pay heed to such ideas.

#donald ingber#wyss institute#science#institute#academia#conscilience#nassim nicholas taleb#taleb#joi ito#antifragile#policy#pixar#campus#collaboration#laboratories#nanotech#biodesign#nature#cells

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would we miss the Media Lab if it were gone?

A friend and MIT grad wrote to me yesterday, “I don’t know if the Media Lab is redeemable at all.” This in the wake of the bombshell Ronan Farrow piece in the New Yorker, reporting that the Media Lab under its director Joi Ito had covered up a much closer relationship with Jeffrey Epstein than previously revealed. Ito promptly resigned.

The Media Lab has always occupied a curious place in the tech world. According to itself, it “transcends known boundaries and disciplines by actively promoting a unique, antidisciplinary culture that emboldens unconventional mixing and matching of seemingly disparate research areas … In its earliest years, some saw the Media Lab as a house of misfits. Here, the emphasis was on building; the Lab’s motto was “demo or die.””

It ceased being viewed as a house of misfits a long time ago. Instead it has become perceived as a hyper-prestigious, creme-de-la-creme entity, a weird mixture of counterculture and patrician, seen as home to the best (and coolest) of the best, whose annual budget has tripled from $25 million in 2009 to $75 million in 2019. It seems fair to estimate that roughly a billion inflation-adjusted dollars have been spent on it since its birth in 1986.

While it’s an academic institution it has always been exceptionally business-oriented. “At first glance, much of the Media Lab’s research may seem tangential to current business realities, but for more than 30 years, the Lab has demonstrated that seemingly “far out” research can find its way into the most conventional—and useful—applications … The Media Lab has spawned dozens of new products by our members, and over 150 start-up companies,” to quote, again, them.

And yet. One can’t help but notice. Consider its basic ingredients:

founded in 1986, as Moore’s Law began to hit us all, and tech began the exponential growth that has made it the world’s dominant force

at the most prestigious technical university on the entire planet

in a position to pick and choose from the brightest minds of its generation

allotted $1 billion to spend over those thirty years of hockey-stick growth

Given all that, wouldn’t you have expected … well … a whole lot more than what it has actually accomplished?

Because that list of accomplishments is surprisingly scrawny. Take its spin-off companies. Here’s its list. Trivia question: how many Media Lab spinoffs have gone public, without merging or being acquired, in its 33 years of existence? As far as I can tell, the answer is one, and even that comes with a sizable asterisk: the Art Technology Group, which didn’t start building products until six years after it spun out (it was a consultancy), IPOd during the first dot-boom, and was eventually acquired by Oracle.

There are companies you’ll recognize on that list. Well, there’s one: BuzzFeed. Yes, really. There are a few others of note. Harmonix, makers of Rock Band. Makani Power, acquired by Alphabet six years ago. Elance, which became Upwork and then had its platform phased out. Jana. Formlabs, Otherlab, The Echo Nest, all of which I think are great, but none of which I would have heard of if not for some personal connections. One Laptop Per Child, a bad idea a decade ago and a forgotten one now. And, notably, E Ink, the Media Lab’s one definite, unambiguous big win … back in 1996.

It’s not nothing, but it’s so much less than you’d expect, given its ingredients. It’s certainly no Bell Labs, or Xerox PARC, or even Y Combinator, and I say that as someone who is less of a YC enthusiast than most of the Valley.

OK, I hear you arguing, but they’re a basic research facility! Spinoff companies are not their true measure of success! Sure. Fine. So let’s take a hard look at their own list of their top 30 tech products or platforms (PDF). Aside from E Ink — which, again, was 23 years ago — doesn’t that look a lot like a list of occasionally interesting, but fundamentally limited and/or niche, technologies? Doesn’t it seem rather utterly devoid of any significant impact on the world?

Wouldn’t you have expected so, so much more?

Criticisms that the Lab is more about style and sizzle than serious substance are not exactly new. Nor are they old: here’s a piece condemning its recent “personal food computer” as smoke and mirrors that doesn’t actually work. This “Hunter S. Negroponte” piece dates back to the 1990s. It’s satire, but if you read it, you’ll likely find you can’t help but raise your eyebrows and wonder just how far back the Media Lab’s systemic problems go.

Maybe if it hadn’t been a “plutocratic friendocracy,” to quote former Media Lab faculty, and it had actually systemically favored the best and brightest and most innovative, regardless of background or personal connection — maybe then things would have been very different. Maybe it would actually have been what it pretended to be for all this time.

0 notes

Quote

Sovereignty and discipline, legislation, the right of sovereignty and disciplinary mechanisms are in fact the two things that constitute - in an absolute sense - the general mechanisms of power in our society. Truth to tell, if we are to struggle against disciplines, or rather against disciplinary power, in our search for nondisciplinary power, we should not be turning to the old right of sovereignty; we should be looking for a new right that is both antidisciplinary and emancipatory from the principle of sovereignty.

Michel Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended”, Lecture of 14th January 1976, p.39-40

Thought of this quote after hearing a snippet of Steve Bannon speaking at CPAC; “sovereignty”, of course, has also been a mainstay of Brexit rhetoric. Any study of politics, law, or history of course shows it to be quite a slippery term - and by ‘regaining’ it one can only put it meaningfully to work by negotiating agreements with other sovereign countries, in a way that’s hard to distinguish from the derided state of ‘globalist’ affairs.

Foucault uses the term in a specifically domestic, inwardly political sense - a form of (at least in theory) untrammelled power that contrasts with the scientific regulation of society by discipline. Originally I took his argument as a basis for a critique of “rights discourse” - the attempt to circumvent political disputation by appealing to the sovereignty of human rights - including its weakness against the technocratic rule of neoliberal reason (which Foucault would go on to describe in the two subsequent years of lectures, titled Security, Territory, Population and The Birth of Biopolitics). This was his diagnosis, immediately prior to the quote above:

“… we now find ourselves in a situation where the only existing and apparently solid recourse we have against the usurpations of disciplinary mechanics and against the rise of a power that is bound up with scientific knowledge is precisely a recourse or return to a right that is organized around sovereignty, or that is articulated on that old principle. Which means in concrete terms that when we want to make some objections against disciplines and all the knowledge-effects and power-effects that are bound up with them, what do we do in concrete terms? What do we do in real life? What do the Syndicat de la magistrature and other institutions like it do? What do we do? We obviously invoke right, the famous old formal, bourgeois right. And it is in reality the right of sovereignty. And I think that at this point we are in a sort of bottleneck, that we cannot go on working like this forever; having recourse to sovereignty against discipline will not enable us to limit the effects of disciplinary power.”

If Bannon (like the Brexiteers) on the one hand wants to restore the quasi-mythical ‘sovereignty’ of the nation-state, and on the other aims for the “deconstruction [sic] of the administrative state”, it seems in an odd way a repetition of “having recourse to sovereignty against discipline”. Admittedly it’s hard to see conservatives opposing discipline in the fields of immigration, labour rights, healthcare - basically anywhere where the regulatory subject is living people and not corporations - with the exception of where true regulation interferes with sovereign will: that is, the ‘rule of law’. (Mike Konczal has a good piece on the evolution of America’s administrative state, how bureaucracy was used “to solve problems and to advance liberty”) But the contradiction between sovereignty and discipline goes to the heart of that between the neoliberal project and its opponents in populism.

The rhetorical attacks on the judiciary (from Trump in the US and from the Daily Mail in the UK) betray an inability to see governance as the outcome of a rule-based process. The sovereign power derived from the popular will (helpfully mediated by the US electoral college; a bare majority in the UK) is in one sense meant to be a response to the bureaucratic discipline imposed by neoliberalism, which is a form of ‘re-regulation’ as much as ‘deregulation’. What is something like TPP except a very complex (and unfair) set of rules? Trump’s travel ban, a sweeping and ill-drafted order,

“is a naked demonstration of the current regime’s willingness and intent to suspend the rights and protections afforded by the Constitution on the basis of religion, nationality, or ultimately any other arbitrary marker of identity, even at the cost of vast economic inefficiencies or the disempowering of the judicial branch.”

Note the “even at the cost” part - against economic rationality, and its flip side, the ‘rule of law’ protecting the modern bureaucratic and capitalist state. Both of these are key to liberalism in its various forms: limiting state interference in the market, and ostensibly in the lives of individual citizens; while at the same time submitting workers to economic discipline, and everyone to the biopolitical discipline of the expanded state (whether the citizen is ‘sovereign’ or a disciplined subject generally depends on access to financial and cultural capital, and legal representation).

And yet, as Foucault tells it, neoliberalism emerged in response to fascism and Nazism - the failure of the earlier liberalism to guarantee the independence of the market from the state and the pressures of democratic politics (what we now call ‘populism’). Key to the German ordoliberals was the establishment of an ‘economic constitution’ on the one hand, and the ‘deproletarianisation’ of the workers on the other, by integrating them into a competitive society (but supported, in the European way, by social insurance). In America, the cultural call of capitalism is stronger, so Chicago School neoliberalism focused more on removing regulation and embracing risk, but the overall structure is the same: only now the deproletarianised workers (the American Dream-ing ‘middle class’) are also deindustrialised, and are revolting against the liberal, bureaucratic small-c constitution that they blame for taking away their jobs and living standards.

Enter Trump, who rhetorically beats down on the regulation that keeps business under bureaucratic discipline, and waves about the power of sovereignty (’we will build the wall!’). It’s not clear so far how much in practice he will be able, or wish to do in replacing the economic order that is at the heart of neoliberalism (including free trade). Ultimately this may show how the weakness of invoking ‘sovereignty’ affects both left and right; or it may lead to an authoritarian populism, against which a neo-neo-liberalism emerges to restore the guarantees of market and bureaucratic-state discipline. A problem with Foucault’s remarks is that he never really goes on to define what an “antidisciplinary and emancipatory” right would be, so it feels somewhat empty. However, I would argue that the answer is at least implicit in his later discussions on parrhesia, truth and democracy - the ethics of critique as a political process that must be undertaken without predefined ends, or even strategies.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The MIT Media Lab has launched a new journal of design and science. In the introduction to the new publication, Joichi Ito, the Media Lab's director, writes:

I believe that by making a “lens” and a fusion of design and science, we can fundamentally advance both. This connection includes both the science of design and the design of science, as well as the dynamic relationship between these two activities. As I have written previously, one of the first words that I learned when I joined the Media Lab in 2011 was “antidisciplinary.” It was listed as a requirement in an ad seeking applicants for a new faculty position. Interdisciplinary work is when people from different disciplines work together. But antidisciplinary is something very different; it’s about working in spaces that simply do not fit into any existing academic discipline–a specific field of study with its own particular words, frameworks, and methods.

The first selection of essays look great and I'm curious to see how it evolves. Wired has a look at how the journal seeks to break from traditional academic journals:

JoDS is run very differently from a traditional academic publication. There’s no anonymized peer-review process, and there’s no fee to access its contents. “We wondered what does an academic paper look like when it’s more about the conversation, and less about tombstones,” Ito says, referring to a quote from Stewart Brand that likens formal academic publishing to burying ideas like the dead. The journal is published on PubPub, a platform developed at MIT that is inclusive in ways that academia and academic publishing frequently aren’t; PubPub is an experiment in radical transparency, where almost every part of the journal is open and editable. Readers can annotate each paper, adding comments and context to what the author wrote. The editing history is visible to everyone, so authorship is no longer an opaque attribution. Hillis’ paper has executable code that can be lifted directly from the journal.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I dont know if its just the autism-research-concreteness complex in my brain but I really like having words for things and its like satisfying but also a little annoying to see a lot of philosophical or political discussions that arent framed as such that seem like theyd benefit from language that lets you search and connect w historical manifestations of the concept.

i also like how ideas manifest in different frameworks and i wish antidisciplinary thinking were more of a thing so you could point to parallels without sounding wacky

like i guess ideologically i feel like “people would have an easier time organizing and surfacing consciousness of various issues if they knew there was a word for it and not just a vague feeling”

like now i’m doing research into trauma support and cptsd and inner child work and such and so repeatedly the concept comes up that theres a fundamental and immutable goodness-potential in a person, and that people generally grow when they can recognize that while also being held accountable for their problematic behavior (guilt for having behaved badly, vs shame for “being bad”)

which seems like a really important framework for the general cluster of discussions online about… everything… but talk about trauma often is just about triggers and honestly reinforcing avoidance patterns (to be clear i am 100% for trigger warnings i just think the dominance of it in trauma discussions as opposed to a variety of approaches belies the idea that trauma cannot heal, which Is avoidance)

and then i was doing a little research into certain kabbalah ideas , this one i’m hesitant to assert too strongly because kabbalah is a kind of secret knowledge so theres a lot of misinfo, but it seems fairly true that in the philosophy of kabbalah all people and things have essences/sparks of the eternal and good light of god/eternity, and that the world is then bound up in layers of material, mechanical, and behavioral constrictions that filter that light. so you would want to move toward the revelation of the goodness (ie behaving good, making the world good) but really it is already good, just hidden. and its like. wow! its all right there

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Denes Agnes, Manifesto, created for students of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2019.

[...] Change is the only thing you can count on. You learn how to walk without crutches, and with very little to depend on. Even the truth, that great challenger, because it is beyond the long end of your telescope even in the land of ultimates, changes meaning, leaving many truths, and nothing to depend on. Wanting to change the world morphed into a unique artistic output of a lifetime of creation, and the visualization of invisible processes, such as math, logic, thinking processes, and so on. This process of re-evaluation and visualization became a process of offering humanity benign solutions to some of its problems and involved a multitude of disciplines. So now ask yourselves, where are you at your age of wanting to change things?

#radicantattitude#design#art#designofchance#antidisciplinary#poetry#tellingtheevolution#ecologiesofimagination#manifesto#agnesdenes#2019s

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Researchers Resign in Protest Over MIT Media Lab’s Ties to Jeffrey Epstein

Two researchers have cut ties with MIT Media Lab over its connections to Jeffrey Epstein, the multimillionaire sex offender who died of an apparent suicide earlier this month while awaiting federal charges for the sex trafficking of minors. Ethan Zuckerman, the head of the Media Lab’s Center for Civic Media, published a Medium post detailing why he is leaving the research institute by May 2020, the end of this academic year. J. Nathan Matias, a visiting professor, also announced his intention to leave the research institute. MIT Media Lab is an “antidisciplinary” research institute that tries to blend technology and media together into innovative products or services, relying heavily on close collaboration with corporate and military partners.

On August 9, the night before Epstein’s death, an unsealed deposition revealed a list of men Epstein allegedly forced a young woman to have sex with. The list included the late Marvin Minsky, an MIT scientist and early AI pioneer who was a founding faculty member of the Media Lab. Zuckerman had a conversation with Joi Ito, the Media Lab’s current director, about the institute’s relationship to Epstein. Zuckerman wrote that “Joi told me that evening that the Media Lab’s ties to Epstein went much deeper.” The next day, on August 10, Zuckerman informed Ito that he would leave the Media Lab.

A week after his conversation with Zuckerman, Ito wrote “an apology regarding Epstein.” In it, he revealed that he had a business relationship with Epstein, allowed the financier to invest in startups that Ito’s venture capitalist fund had a stake in, and allowed Epstein to provide gifts to the Media Lab. He had also allowed Epstein to visit the Media Lab and had visited several of Epstein’s residences himself.

This comes as a reversal from five years ago when MIT Media Lab rebuked accusations that Epstein had provided funding to help the Media Lab teach toddlers computer programming. Ties between the Media Lab and Epstein may go even further than that: Ito’s tenure at Media Lab began in 2005, but technology writer Evgeny Morozov unearthed a 2005 dissertation with Marvin Minsky as a thesis advisor that listed Epstein as one of the Media Lab’s sponsors.

Wednesday, Matias wrote that he too would be leaving the research institute by May 2020. For the past two years, he has worked with CivilServant, a behavioral science nonprofit that has done research that includes work on “protecting women and other vulnerable people online from abuse and harassment.” After learning of Epstein’s ties to Media Lab, he wrote: “I cannot with integrity do [my work with CivilServant] from a place with the kind of relationship that the Media has had with Epstein. It’s that simple.”

In his personal apology, Ito pledged to return the money and raise an equal amount to be given to non-profits focused on supporting survivors of trafficking. MIT, however, has not issued an apology nor has it promised to return any of the money received from Epstein.

“I’m aware of the privilege that it’s been to work at a place filled with as much creativity and brilliance as the Media Lab,” Zuckerman wrote in his Medium post. “But I’m also aware that privilege can be blinding, and can cause people to ignore situations that should be simple matters of right and wrong.”

In an email to Motherboard, Zuckerman declined to comment further: “My focus right now is on helping my staff and students work through their academic and professional next steps,” he said. MIT Media Lab and Matias did not immediately return a request for comment.

Two Researchers Resign in Protest Over MIT Media Lab’s Ties to Jeffrey Epstein syndicated from https://triviaqaweb.wordpress.com/feed/

0 notes

Text

Why Is There So Much Saudi Money in American Universities?

Saudi Arabia directed about $650 million to American universities from 2012 to 2018 and ranks third on the list of foreign sources of money. M.I.T. received $7.2 million in the last fiscal year. An M.I.T. report noted that M.I.T. is been aware of Saudi Arabia’s “internal repression and external aggression” but that until recently some still believed it was on a path to becoming a more progressive society. “The Khashoggi murder has deflated many of those hopes. There were also the particular facts of this case, notably the combination of brazenness, brutality and contempt for international opinion that made it stand out even within the crowded global gallery of official malevolence.” If you were an M.I.T. administrator, what would you do: (1) continue to accept money from Saudi Arabia, or (2) reject all future money? Why? What are the ethics underlying your decision?

One spring afternoon last year, protesters gathered on a sidewalk alongside a busy street in Cambridge, Mass. City buses rolled past. Car horns sounded. A few pedestrians paused briefly before continuing on their way. The location was 77 Massachusetts Avenue, in front of a limestone-and-concrete edifice that serves as the gateway into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The building’s lobby leads to a long hallway known as the Infinite Corridor and into the heart of one of America’s most vaunted academic institutions.

Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, would be visiting the next day. The protesters, a mix of students and local peace activists, wanted his invitation revoked. They were opposed to the prince being welcomed as an honored dignitary and were calling attention to the Saudi state’s financial ties to M.I.T. — and to at least 62 other American universities — at a time when the regime’s bombing of civilians in a war in neighboring Yemen and its crackdown on domestic dissidents were being condemned by human rights activists.

Prince Mohammed, who is 33, became Saudi Arabia’s de facto leader in 2017, when he was named crown prince by his ailing father, King Salman. He was in the midst of an American tour and had already been to the White House to meet President Trump, who said, as they sat together in the Oval Office, that they had become “very good friends over a fairly short period of time.” The president thanked the prince for what he said was the kingdom’s order of billions of dollars of American-made military hardware. “That’s peanuts to you,” he quipped.

From Cambridge, Prince Mohammed’s travels would take him to California, where he rented the entire 285-room Four Seasons hotel in Beverly Hills and was the guest of honor at a dinner hosted by Rupert Murdoch and attended by numerous entertainment-industry grandees. In Silicon Valley, he met with Tim Cook, the chief executive of Apple, and other tech executives; in Seattle, he met with Jeff Bezos, the Amazon chief executive. Saudi Arabia was already an investor in Uber through its sovereign wealth fund, which is controlled by the crown prince, and Prince Mohammed was negotiating to buy a stake in Endeavor, the Hollywood conglomerate that includes the WME talent agency and the Ultimate Fighting Championship business.

At these stops on the West Coast, he dressed in either a suit or jeans, sport jacket and open-collared shirt, instead of the traditional black robe and red-and-white-checkered kaffiyeh he wore to the White House. “Here was this young guy who was sort of hip and fit in with the Silicon Valley and Hollywood crowd, and they were easily manipulated,” says Robert Jordan, an ambassador to Saudi Arabia under President George W. Bush. “It was money speaking, and the temptation to hook up with a massively funded kingdom.”

On the sidewalk that day in Cambridge, one of the featured speakers was Shireen al-Adeimi, who is 35. She was born in Yemen and spent part of her childhood there. Her relatives in Yemen were now living through a civil war, one that had caused tens of thousands of civilian casualties and was threatening millions with famine — and yet had barely registered in the American news cycle at that point. The American universities doing business with the Saudis — largely in the form of sponsored research, paid for with money from Saudi Aramco, the giant oil company, and other state-owned industries — saw no reason to stop, and the lonely voices who argued against those ties were easily ignored.

Al-Adeimi lived nearby with her husband, a Ph.D. student, in an apartment owned by M.I.T. She was finishing her own doctoral studies at Harvard and would soon begin a job as an assistant professor of education at Michigan State. She had never been politically active before — “If I ever had something to say in public, I thought it would be about education,” she says — but had started speaking out against Saudi conduct in Yemen by posting on social media and by writing to American politicians. At the demonstration, she wore a gray blazer and a peach head scarf and spoke in a soft but steady voice into a hand-held microphone. “The man M.I.T. is hosting is starving millions of people to death by blockading access to food and medicine,” she said. “The man M.I.T. is hosting has created the worst humanitarian crisis on earth. Simply put, the man M.I.T. is hosting is a war criminal, and he should be punished for his crimes and not welcomed here.”

Al-Adeimi and five others entered the M.I.T. building and walked down the Infinite Corridor to deliver a petition to the university’s president, Rafael Reif. There were some 4,000 names on the petition asking him to cancel Prince Mohammed’s visit. Reif was not in his office, and they never got a response.

The next morning, Prince Mohammed spent several hours at M.I.T.’s Media Lab, a high-profile domain with a carefully cultivated progressive image and a language all its own. (It describes its curriculum not as interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary but as antidisciplinary.) A majority of the Media Lab’s $75 million annual budget comes from corporate patrons, which are referred to as members and pay a minimum of $250,000 each year. Prince Mohammed’s personal foundation was among the roughly 90 members. The Saudis signed three contracts that day, for a total of $23 million, two of them to extend existing research projects with M.I.T. The other one was for a new initiative between the university and Sabic, a Saudi state-owned petrochemical company, for research into more efficient refining of natural gas.

At the time of Prince Mohammed’s visit, Saudi Arabia seemed to be liberalizing, at least a little. Women had been granted permission to drive, finally, a reform that gained a great deal of media attention. When a movie theater opened in Riyadh that spring, it ended a 35-year ban on cinemas. (“Black Panther” was the first showing; a late scene, a kiss between two of the stars, was cut by censors.) Six months after the prince’s triumphal American trip, on Oct. 2, the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi citizen who lived in Virginia and was a columnist for The Washington Post, was murdered inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. American intelligence agencies held the Saudi state responsible and concluded that the crown prince himself most likely authorized the action. (A United Nations report released in June reached a similar conclusion.)

Later in October, M.I.T. announced that it was reassessing its extensive links to the kingdom. Richard Lester, an associate provost who oversees the school’s partnerships with foreign entities, was put in charge of that review. A nuclear engineer by training, Lester is an M.I.T. lifer, having joined the faculty in 1979 when he was in his mid-20s; he is now 65. His mission was to explore whether a source of money could be so unsavory as to warrant rejecting or returning the funds — hardly an easy task. Once an institution goes down that road, what other donors might some on campus find objectionable? What other streams of funding could be endangered? What names might have to come off buildings?

In December, Lester outlined his preliminary findings in a letter to Reif, which was also shared with faculty members and students. Lester had to acknowledge an uncomfortable fact: “One of those individuals now known to have played a leading role in Mr. Khashoggi’s murder in Istanbul had been part of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s entourage during the latter’s visit to the M.I.T. campus,” he wrote, referring to Maher Abdulaziz Mutreb, a Saudi intelligence officer. “This individual had engaged with members of the M.I.T. community at that time — an unwelcome and unsettling intrusion into our space, even though evident only in retrospect.”

Endeavor returned a $400 million investment from Saudi Arabia this year, but many other American corporations stayed in business with the kingdom. In April, the regime executed 37 people in one day, most by beheading; one of the condemned was said to have been “crucified,” with his headless body displayed in public. Investors eagerly bought Aramco bonds, which were offered for the first time in April, and AMC still plans to build dozens of new theaters in the kingdom.

Activists on campus, however, wanted more from their universities. “They all have those Latin sayings, stating some higher purpose,” says Grif Peterson, a former fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard. “Look at it, it’s right there on the wall.”

M.I.T. does not need Saudi Arabia’s money. Chartered on the eve of the Civil War (two days before the first shots were fired), it is one of those ultrawealthy universities whose finances are sometimes compared to the economies of small or midsize nations. M.I.T. spent about $3.6 billion on its operations last year, and its endowment, $16.5 billion, is the sixth-largest among American universities (and greater than the gross domestic product of nearly 70 countries, including Mongolia, Nicaragua and the Republic of Congo). The money it receives from Saudi sources is relatively modest, less than $10 million in many years, though the school has received individual gifts from Saudi billionaires of as much as $43 million.

VERY LONG ARTICLE CONTINUES ...

0 notes

Text

Reading Response #3: Representation

In this weeks conversation on representation, the listening/interview with Damali Ayo really resonated with me. There is something intimate, and uncomfortable about matching a skin tone, whether that be with paint or makeup (aka paint) and I found this exploration super interesting. The way one of the paint mixers flirted with her made me uncomfortable, and made me think of the way I am sexualized as a woman of color, the way our bodies can not simply exist without being connected to the sexual. However, also thinking about this in relation to Ayo’s response - about how she was “saving the interaction for later fantasies,” and how I struggle with the anger I feel about oversexualization of brown women vs. the empowerment from sexual liberation of these women. When comparing her interaction with the male paint mixers vs the female the interactions are very different. Was the female simply being professional in her lack of small talk, & was the small talk of the men flirting, or otherwise sexually charged in a way?

In her work, Ayo hid the recorder from site, a choice that allowed for authentic experience to be captured. I thought about this in relation to Kisliuk reading, and her experiences with field work. This piece made me uncomfortable because I imagine a white woman in Africa, asking for a sneak peak into the lives of people she otherwise would have no contact with. It made me wonder about the ethics of this type of ethnography, regarding who is conducting a study, the identities they hold, and the privileges they hold. It made me wonder if an ethnographer can capture an authentic experience as an outsider? Especially in comparison to Ayo, who captures an experience that she is also fully a part of.

Finally, in discussing representation I think it’s especially important to mention my favorite reading from this week, Low Theory from the Queer Art of Failure. This piece brings up the types of knowledge that are considered “high” or “low,” and the importance of the accessibility of knowledge. A question posed by the author that I feel relates to my prior discussion is: “How do we engage in and teach antidisciplinary knowledge?” As a scientist, I think about this A LOT. I am constantly struggling between believing in the scientific method, while trying to dismantle this belief that science is “all knowing” or always right. In context of this class, I think the question is something we should be asking ourselves as we go out and record experiences, people, performance, etc to think critically about the what, why, and how we are recording.

0 notes

Photo

Over stretched The points highlighted in this book are all good points, but they are rather easy-to-understand ideas that can be adequately articulated in a blog article. If you are familiar with this type of concepts, there is not a lot of depth here. The key points are: embrace uncertainty, collaborative over individual efforts, adaptability over rigidity, etc. Go to Amazon

Joi Ito of the MIT Media Lab Offers Nine Principles For Facing The Future This book is a MUST READ for anyone who needs to think about innovation and the rapid pace of change leading to an uncertain future. Authors Joi Ito, Director of MIT's iconic Media Lab ,and Jeff Howe, a visiting scholar at the Media Lab, have opened a window into the principles that drive innovation and research at the Lab. The structure of the book introduces each of the 9 principles and how they impact the setting of research priorities. The principles are illustrated and elucidated through vignettes that tell how researchers at MIT and beyond have employed the antidisciplinary ethos of the Lab to forge teams of women and men from a wide and disparate set of fields of study and expertise. Go to Amazon

Distilled guidance for an uncertain tech future. All of Joi's intelligence and guidance about our "learn, unlearn and relearn" future wrapped up in one book. Guidance from Joi Ito for tech startups and companies employing tech (all of them now) has proven invaluable for the last two decades. This book distills the many lectures, Facebook live chats, blog entries and other wisdom from this man who Business Week once said was one of the 25 most influential people on the Web. Highly recommended. Go to Amazon

I found it this book interesting but I think it ... I found it this book interesting but I think it is written in a confused way, or maybe it was just too difficult for a deep understanding in my case. I will probably go back to it as soon as I will have enough time to dedicate it. Go to Amazon

Insightful and Provocative This is an insightful and provocative book. It reminds me of "Future Shock" from a previous generation. The live examples not only demonstrate the rapid rate of change, but clearly show the need for a paradigm shift in our thinking. Go to Amazon

Not very organized While some ideas and anecdotes are interesting, the book seems a bit rambling and poorly edited. It is also not clear the extent of Joi's contribution other than his PS entries. Go to Amazon

Underwhelmed I had an excited expectation for reading this book. Was rather let down. Go to Amazon

The future? How do you know you're even in the present? Similar to Kevin Kelly's Inevitable, Whiplash helps us understand that our future is being woven today, and this fabric is complex and in motion. They start with William Gibson's notion that the future is here by not evenly distributed to remind us that we are not all socketted into the center of where the action will be tomorrow. And then they go on to describe how and where these new developments are occurring and what their portent might be. Also a history of some aspects of the MIT Media Lab, and a great launching pad for any number of new ideas. Well worth the time to read! Go to Amazon

MIT Media Lab leader gets it right Five Stars It's good, but not great Five Stars Food for thought Very poor writing, a regrettable work. Five Stars Sound advice for an uncertain future Four Stars Five Stars

0 notes