#animal research

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Parrots learn to make video calls to chat with other parrots, then develop friendships with each other

Researchers from Northeastern University, in conjunction with scientists from MIT and the University of Glasgow, conducted a study exploring the impact of teaching a group of domesticated birds to communicate using tablets and smartphones. The findings indicate that utilizing video calls may assist parrots in mimicking the communication patterns observed in wild birds, potentially enhancing their behavior and overall well-being in the homes of their owners.

via smithsonianmag.com

#parrot#mit#northeastern university#university of glasgow#study#animals#technology#video call#wild birds#TechForPets#Animal research#animal behavior

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

(these are going to be used for [redacted] and are not proportional, but cumulative. please vote accordingly. thank you)

#snakes#tumblr polls#animal research#snakeblr#snakes of tumblr#please make me a very dangerous snake that i can use to defeat my nemesis that i may also have a gay crush on thanks

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

So the thing I didn't mention in that poll I published yesterday is that the motor initiation piece that is, at the time of this writing, absolutely sweeping the poll as the Worst Thing people struggle with?

It's the specific thing I'm trying to pull together a grant for, perhaps unsurprisingly. But it's also the only one that actually isn't classically conceptualized as executive function. (I know, I know, that feels stupid to me, too.)

See, formally speaking, we describe executive function in terms of higher-order cognitive processes that allow us to complete complex tasks. There is a lot of work on, for example, "set shifting" (which is a particular paradigm for studying the ability to transition between different frames of mind, essentially; it's measuring cognitive flexibility) and on action inhibition / impulse control. (One of my colleagues works on set shifting, in fact, and I might actually take a look at that later.) We also have a lot of work on how individuals make decisions and prioritize conflicting needs.

But the transition between motivation and motion is a lot harder to study, and it doesn't fit so neatly into this top down paradigm, either. Most of the people who study this kind of movement initiation are people who aren't really focused on executive function per se at all. They're mostly people who work on Parkinson's, in fact.

The problem is that the best way to untangle how these systems work is to break specific things and see what impact that has on the overall function, and that means working with animal models. You know what we can't study as easily with animal models? Wanting to move and not being able to initiate self-paced motion—that is, we can't get inside an animal's head to understand what it wants to do in the absence of a moving body to indicate that thing. This is part of why many of our best studied kinds of executive dysfunction involve not doing a thing, rather than doing it: that way you can look at error rates and study a measurable change in behavior.

There are things we can do, though. For example, you can disentangle motivation versus pleasure in a rat that enjoys things but has no motivation to make them happen by asking questions like: I know that rats like water with sugar in it. If I set up a device that squirts a trickle of sugar water into the mouth of the rat, does it close its mouth? What facial expressions does it make? If I put bitrex in the water instead of sugar, does the reaction change? (Yes, emphatically.)

The thing is, motivation is regulated by dopamine... and so is movement. There's good reason to think that neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD and autism are mediated by weird dopamine signaling patterns, and we certainly know that there is a direct relationship between abnormally high dopamine signaling and schizophrenia symptoms... and that abnormally low dopamine will give you Parkinsonian tremors.

Most stimulant meds for ADHD work by upregulating dopamine signaling, too. All of them are associated with increased locomotor activity, among other things. We know that dopaminergic signaling precedes actions in the body, too: you get firing before the actual motion happens.

Somewhere there is a threshold of motion initiation that is getting fuckily disconnected. I have some thoughts about where it is, but I definitely need to run some experiments to check my hypotheses against evidence.

#Executive function#Neurodivergence#autism#I have got to make myself some canonical tasks here#Tags not tasks#Animal research#Day job#Neuroscience

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started reading the book 'Pests' by Bethany Brookshire. I thought it would be a book filled with information on how to protect your garden without causing any harm to animals. I could not have been more wrong, but soon it didn't matter, because I was drawn in immediately. This book is written by a brilliant scientist, who presents to you, the history, the data, the results and the cultural context of pests all around the world. It starts with squirrels, but then goes on to talk about pythons, pigeons, cats, rats, mice, frogs, coyotes, wolves, elephants, dogs, raccoons, deer, bears – and how they've been seen as a pest, most often for no fault of their own.

I learned about the numerous ways people in the past have created a 'pest' problem for themselves, and how they went on resolving it, and honestly I was shocked at the most of it. I did not know that human scientists developed specific plagues for animals in order to get rid of them. I also had no idea how quickly humans turned the perception of a certain animal from 'useful' to 'pest', without even realizing they're responsible for the behaviour of the animal in the first place. Also the number of times humans have attempted to introduce a predator in order to get rid of an invasive species – only to immediately cause a new invasive species, absolutely incredible.

I was surprised to find out that some specific animals could be pests at all, for example, elephants. Absorbing the information presented to me thus far, I thought elephants were nothing short of wonderful and welcome in anyone's life – but, the story describes them eating the entire fields worth of grain, in only one night. And due to their size, they're unstoppable. They've destroyed houses, and even killed people, as a result of trying to get to the food. The elephants are a protected species, so the locals have been forced to develop different way of co-existing, namely, to stop growing grain and try to find different ways of survival and sustenance. There have been numerous other attempts to protect the fields from them, but how would you protect anything from an elephant? The only thing they're scared of, are bees. And if there's food to be gained, they'll overcome the fear of the bees too.

Did you know that if mice multiply too much, they'll have a mice plague that will wipe them out, without human interference? Mice and rats are described as the animals closest to us – because they live where we live, eat what we eat, and learn whatever it takes to find their way in the land of humans. And it seems, we have the same problems as well.

One of my favourite little piece of knowledge in this book: the scientists studying the snakes in a lab name the snakes after Slytherins – so they have Snape, Draco, Crabbe, Goyle, and Bellatrix. It was amazing to listen about Snape the snake.

The author of this book is incredibly unbiased, and shows her love for every animal mentioned, but also understanding and compassion for people who have felt wronged, violated, helpless and cornered by the animal, and how awful it feels to not be able to protect their homes and livelihoods from an animal invading their territory. In author's mind, the animals are not at fault, because all they've been trying to do is survive, get to the source of food, for them this is foraging. For us, it's nature taking from us what we intended for ourselves.

The problem of seeing animals as pests, comes often from the perception of us being the dominating species, and having the right to remove or introduce or change animals, by how convenient and pleasing we find them. She sourced the problems from negative experiences, loss, violation and danger, but also from culture, colonialism, religion, behaviours of the people around us. Most children have no concept of danger or pests – babies in a study would reach out curiously seeing a picture of snake. Perception of which animal is good and which one is bad, comes with culture, experience and the behaviour of everyone else around it. And our collective perception comes from whether the animal is rare, whether it lives close to us, if we have to adjust our lives because of it or not, if we have had negative experiences or not, whether it can hurt us, whether we have something the animal wants (food) and tries to get from us.

I recommend this book to anyone who'd like to know more about the history of humans trying to live alongside – or refusing to live alongside certain animals. And anyone dealing with any kind of pest, or just not understanding why animals act the way they do around humans.

I come out from reading this, feeling no more wise on how to keep the pests out – except for, don't leave the food outside the house where animals can get to it, that's the #1 reason for most scenarios – but feeling way more understanding and at ease about animals that are perceived as pests. I know solutions that have been tried to deal with them, I know what didn't work, and I know how badly some collective solutions can become. I understand we need to find a way to live with them as our neighbours, not enemies, not violators of our property. And most often, just being responsible about where you leave your food, how much animals you tempt to come close to you, how you reward them for interacting with you, is more than a half of the solution.

#pests#bethany brookshire#sustainable culture#living alongside animals#coexisting with animals#environmentalism#animal science#animal research#ways scientists and people have dealt with animals in the past#educational#resources#pssst if you want to listen to the audiobook i can send it to you#i love the audio version

245 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is your opinion on capturing animals for educational purposes and then setting them free? (Like using a moth trap to study them and set them free afterwards)

I’m not sure if you mean educational purposes or research purposes so I’ll cover both. I think the intention is just to educate someone then that can be done with footage and text, you don’t need to capture a live animal for that.

As for actual research, I think it depends on what is being studied and why. If the research is to benefit the animal and the risk of harm/stress is reduced as much as possible, then I’d argue it’s justified on that basis. We do need to know about animals to be able to help them, but disruption should be kept to an absolute minimum wherever possible.

However, I do think that often researchers don’t even seem to ask themselves these sorts of questions when it comes to invertebrates in particular, and are far too willing to interfere with the lives of wild animals for very little reason. There is a culture of believing that the ends justify the means, even in cases where very little is achieved and the animal endures real harm.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voyageurs Wolf Project Donation Drive

Hi, all! I'm not sure if this is kosher, but I really want to help spread the word.

One of my favorite foundations for wolf research, Voyageurs Wolf Project, is asking for donations to help fund their continued research on wolves. They're an amazing organization that teaches us new things about wolves every year - not to mention giving us great photos, video, and news on wolf packs.

They've almost hit their goal!

Please consider donating to their drive here and helping them continue to research wolves!

(note: this does not benefit me in any way; I am unfortunately not involved in Voyageurs Wolf Project, lol. I just really love their work and I love wolves and want to see them continue doing great things for our wolfie friends and helping us better understand them and how to live alongside them.)

#wolf#wolves#wolf research#voyageurs wolf project#real wolves not folklore wolves#animal research#donations#donate if you can

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research using animals is cruel and must end - no matter what people say, if you are not willing to volunteer for it, then you are a hypocrite when you defend it. STOP TORTURING ANIMALS IN LABS.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is it that every time I see a new “ground breaking discovery” in animal research it’s always like “guy you’ll never believe it but we actually found out that animals experience a range of emotions and being mean to them effects them badly” like yeah girl I knew that already when are you going to find a way to read a ferrets brain waves and tell me their favorite color

#I swear it’s like these people have never seen an animal before#I KNOW they have emotions guys this is like the most basic thing to know about animals#please research something actually new and cool and silly next time#animals#science#research#animal research#lab rats

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am working on a short story I'd like to take place in an institutional (like, government or educational facility linked) lab working with at least a few different kinds of invasive species. Are there labs like this? What would I look for to find out more? Do you know where can I find more information about working with animals in labs in a contemporary institutional setting? I'd like it to be as accurate as possible.

assuming you don't mean invertebrates, most labs aren't working with animal species that are native to where the lab is, or at least not working with a completely unaltered wild type, but they don't usually work with a bunch of different species (maybe like, Mice AND one or two others MAYBE, and it would be different people in the lab not one person that different species for the same research), and they usually don't house the animals in the actual lab space. An institute, esp a government one, would likely have a husbandry team and a dedicated vivarium where the animals would be kept and cared for by competent technicians. Labs that work with native species would be like... conservation agencies, fisheries and wildlife, DNR maybe, idk. But it's far more likely to involve field work if the species are native, rather than lab work.

If you have specific questions, you can feel free to come ask. Otherwise you can try contacting, for instance, a dean of research at whatever university is nearest to you, and asking if there's a way you can speak to someone involved in animal husbandry/animal research, and explain why. They might even be able to set up to let you see parts of the vivarium and/or a lab space in person, though you might be hard-pressed to convince them you're not a rights activist seeking to do harm. Universities that take federal funding have a lot of public records that anyone can request to see at any time. I've never had to do it so I don't know how to go about requesting it, but I'm sure you could figure it out with some calling around, if it's important.

The NIH also makes the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals available free online. I don't know how useful that will be, but it has all the care and housing standards for species used in research, including building specs and vet care and all. It can tell you how things are SUPPOSED to be.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interesting case of barbering was found in one of our mice. One of her cage mates decided to give her the full friar tuck hair cut

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Quick question re animal research, I hope that’s okay. I remember reading about how there’s only one law that protects lab animals in the US (animal welfare act iirc), and that it doesn’t apply to something like 90% of them since it excludes rodents, mice, and birds. But I think I read that a long time ago, and on your post people were talking about all the laws that protect lab animals so I was just wondering, are there more laws now? Or are they talking about on an institutional level? How could the govt be investigating if that’s the case? Thanks for answering if you do, and I definitely understand if you don’t because that post blew up, lol.

No worries, thanks for reaching out: the AWA does have regulations that cover every type of animal, as there is a section specifically for animals not already mentioned.

[Images show links to regulations for dogs and cats, guinea pigs and hamsters, rabbits, nonhuman primates, marine mammals, birds, plus a section for anything warm blooded that is not covered in those previous categories.]

A lot of the additional regulations I'm aware of are at the institutional and funding level. Like if you want to get a grant from the NIH for animal research, you have to complete a metric ton of additional paperwork, and you need to have absolutely pristine records of everything that happens to those animals in your lab.

As far as I'm aware, Neuralink sidestepped the latter type of oversight likely because they were able to secure funding from private sources/Elon Musk's own bank account (I have HUGE issues with private philanthropy funding the sciences, I've ranted about this in the past). So the only people who are able to come after him are the feds for violations of the AWA.

If anyone has more in-depth knowledge about either situation though, feel free to pitch in.

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

More and more scientists are realizing that animals, like people, are individuals: They have distinct tendencies, habits, and life experiences that may affect how they perform in an experiment. That means, some researchers argue, that much published research on animal behavior may be biased. Studies claiming to show something about a species as a whole—the distance that green sea turtles migrate, for example, or how chaffinches respond to the song of a rival—may say more about individual animals that were captured or housed in a certain way, or that share certain genetic features. That’s a problem for researchers who seek to understand how animals sense their environments, gain new knowledge, and live their lives. In 2020, Rutz and his colleague Michael Webster, also at the University of St. Andrews, proposed a way to address this problem. They called it STRANGE. They proposed that their fellow behavior researchers consider several factors about their study animals: social background, trappability and self-selection, rearing history, acclimation and habituation, natural changes in responsiveness, genetic makeup, and experience.

“A Cognitive Revolution in Animal Research” from The Atlantic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'd be an animal rescuer.

if we lived in a world where u had to do the career u were first interested in as a child what would u be doing, id be a firefighter

120K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Naked Mole Rats: Nature's Odd Resilience

Discover the secrets of the naked mole rat! These fascinating creatures can survive without oxygen for long periods. Uncover more about their unique abilities!

Check out my other videos here: Animal Kingdom Animal Facts Animal Education

#Helpful Tips#Wild Wow Facts#Naked mole rats#nature's odd resilience#animal adaptation#strange animals#underground creatures#resilient animals#unique mammals#rodent species#mole rat facts#animal biology#African mole rats#animal survival#unusual rodents#evolutionary biology#naked mole rat behavior#animal science#animal research#extreme longevity#aging in animals#mole rat colonies#eusocial mammals#animal resilience#underground ecosystems#mole rat habitat#extraordinary animals#youtube#animal behavior#fun animal facts

0 notes

Text

average United States contains 1000s of pet tigers in backyards" factoid actualy [sic] just statistical error. average person has 0 tigers on property. Activist Georg, who lives the U.S. Capitol & makes up over 10,000 each day, has purposefully been spreading disinformation adn [sic] should not have been counted

I have a big mad today, folks. It's a really frustrating one, because years worth of work has been validated... but the reason for that fucking sucks.

For almost a decade, I've been trying to fact-check the claim that there "are 10,000 to 20,000 pet tigers/big cats in backyards in the United States." I talked to zoo, sanctuary, and private cat people; I looked at legislation, regulation, attack/death/escape incident rates; I read everything I could get my hands on. None of it made sense. None of it lined up. I couldn't find data supporting anything like the population of pet cats being alleged to exist. Some of you might remember the series I published on those findings from 2018 or so under the hashtag #CrouchingTigerHiddenData. I've continued to work on it in the six years since, including publishing a peer reviewed study that counted all the non-pet big cats in the US (because even though they're regulated, apparently nobody bothered to keep track of those either).

I spent years of my life obsessing over that statistic because it was being used to push for new federal legislation that, while well intentioned, contained language that would, and has, created real problems for ethical facilities that have big cats. I wrote a comprehensive - 35 page! - analysis of the issues with the then-current version of the Big Cat Public Safety Act in 2020. When the bill was first introduced to Congress in 2013, a lot of groups promoted it by fear mongering: there's so many pet tigers! they could be hidden around every corner! they could escape and attack you! they could come out of nowhere and eat your children!! Tiger King exposed the masses to the idea of "thousands of abused backyard big cats": as a result the messaging around the bill shifted to being welfare-focused, and the law passed in 2022.

The Big Cat Public Safety Act created a registry, and anyone who owned a private cat and wanted to keep it had to join. If they did, they could keep the animal until it passed, as long as they followed certain strictures (no getting more, no public contact, etc). Don’t register and get caught? Cat is seized and major punishment for you. Registering is therefore highly incentivized. That registry closed in June of 2023, and you can now get that registration data via a Freedom of Information Act request.

Guess how many pet big cats were registered in the whole country?

97.

Not tens of thousands. Not thousands. Not even triple digits. 97.

And that isn't even the right number! Ten USDA licensed facilities registered erroneously. That accounts for 55 of 97 animals. Which leaves us with 42 pet big cats, of all species, in the entire country.

Now, I know that not everyone may have registered. There's probably someone living deep in the woods somewhere with their illegal pet cougar, and there's been at least one random person in Texas arrested for trying to sell a cub since the law passed. But - and here's the big thing - even if there are ten times as many hidden cats than people who registered them - that's nowhere near ten thousand animals. Obviously, I had some questions.

Guess what? Turns out, this is because it was never real. That huge number never had data behind it, wasn't likely to be accurate, and the advocacy groups using that statistic to fearmonger and drive their agenda knew it... and didn't see a problem with that.

Allow me to introduce you to an article published last week.

This article is good. (Full disclose, I'm quoted in it). It's comprehensive and fairly written, and they did their due diligence reporting and fact-checking the piece. They talked to a lot of people on all sides of the story.

But thing that really gets me?

Multiple representatives from major advocacy organizations who worked on the Big Cat Publix Safety Act told the reporter that they knew the statistics they were quoting weren't real. And that they don't care. The end justifies the means, the good guys won over the bad guys, that's just how lobbying works after all. They're so blase about it, it makes my stomach hurt. Let me pull some excerpts from the quotes.

"Whatever the true number, nearly everyone in the debate acknowledges a disparity between the actual census and the figures cited by lawmakers. “The 20,000 number is not real,” said Bill Nimmo, founder of Tigers in America. (...) For his part, Nimmo at Tigers in America sees the exaggerated figure as part of the political process. Prior to the passage of the bill, he said, businesses that exhibited and bred big cats juiced the numbers, too. (...) “I’m not justifying the hyperbolic 20,000,” Nimmo said. “In the world of comparing hyperbole, the good guys won this one.”

"Michelle Sinnott, director and counsel for captive animal law enforcement at the PETA Foundation, emphasized that the law accomplished what it was set out to do. (...) Specific numbers are not what really matter, she said: “Whether there’s one big cat in a private home or whether there’s 10,000 big cats in a private home, the underlying problem of industry is still there.”"

I have no problem with a law ending the private ownership of big cats, and with ending cub petting practices. What I do have a problem with is that these organizations purposefully spread disinformation for years in order to push for it. By their own admission, they repeatedly and intentionally promoted false statistics within Congress. For a decade.

No wonder it never made sense. No wonder no matter where I looked, I couldn't figure out how any of these groups got those numbers, why there was never any data to back any of the claims up, why everything I learned seemed to actively contradict it. It was never real. These people decided the truth didn't matter. They knew they had no proof, couldn't verify their shocking numbers... and they decided that was fine, if it achieved the end they wanted.

So members of the public - probably like you, reading this - and legislators who care about big cats and want to see legislation exist to protect them? They got played, got fed false information through a TV show designed to tug at heartstrings, and it got a law through Congress that's causing real problems for ethical captive big cat management. The 20,000 pet cat number was too sexy - too much of a crisis - for anyone to want to look past it and check that the language of the law wouldn't mess things up up for good zoos and sanctuaries. Whoops! At least the "bad guys" lost, right? (The problems are covered somewhat in the article linked, and I'll go into more details in a future post. You can also read my analysis from 2020, linked up top.)

Now, I know. Something something something facts don't matter this much in our post-truth era, stop caring so much, that's just how politics work, etc. I’m sorry, but no. Absolutely not.

Laws that will impact the welfare of living animals must be crafted carefully, thoughtfully, and precisely in order to ensure they achieve their goals without accidental negative impacts. We have a duty of care to ensure that. And in this case, the law also impacts reservoir populations for critically endangered species! We can't get those back if we mess them up. So maybe, just maybe, if legislators hadn't been so focused on all those alleged pet cats, the bill could have been written narrowly and precisely.

But the minutiae of regulatory impacts aren't sexy, and tiger abuse and TV shows about terrible people are. We all got misled, and now we're here, and the animals in good facilities are already paying for it.

I don't have a conclusion. I'm just mad. The public deserves to know the truth about animal legislation they're voting for, and I hope we all call on our legislators in the future to be far more critical of the data they get fed.

#big cats#tiger king#my research#news#big cat public safety act#animal welfare#big cat welfare#legislation and regulation#vent post#long post#crouchingtigerhiddendata#more on the problems with the bill in the future

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

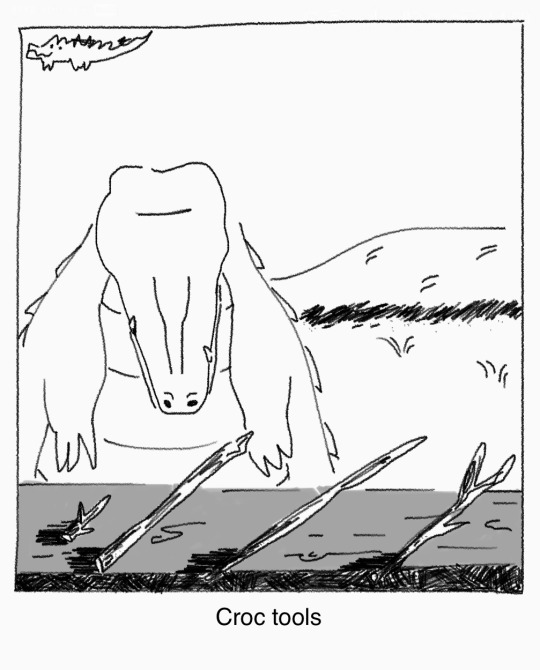

no fucking way

#sketches#comics#the far side#crocodiles#my art#i don’t know how to tag this.#also i should probably say. i tried to look into it further and i haven't seen hard hard evidence that they do this on purpose#personifying animals is tempting but ultimately i think it's just hot speculation atm. crocodilians are famously tough to research too#like the advantages may be a coincidence or just pure curiosity/play. which is also really cute...love those guys#sorry for the misinformation! light theory only afaik#comic

66K notes

·

View notes